Editor’s Highlight: The Tanguay group uses the embryonic zebrafish model to demonstrate the utility of high throughput screening for toxicology studies. The group evaluated the 1060 US EPA ToxCast Phase 1 and 2 compounds on 18 distinct outcomes. With four doses for each compound the group generated a dizzying number of data points highlighting the importance of bioinformatics analysis in these types of studies. The study shows how it is now possible to screen many of the tens of thousands of untested chemicals using a whole animal model in which one can literally see developmental malformations. —Gary W. Miller

Key Words: developmental, high-throughput screening, Tox21, ToxCast.

Abstract

There are tens of thousands of man-made chemicals in the environment; the inherent safety of most of these chemicals is not known. Relevant biological platforms and new computational tools are needed to prioritize testing of chemicals with limited human health hazard information. We describe an experimental design for high-throughput characterization of multidimensional in vivo effects with the power to evaluate trends relating to commonly cited chemical predictors. We evaluated all 1060 unique U.S. EPA ToxCast phase 1 and 2 compounds using the embryonic zebrafish and found that 487 induced significant adverse biological responses. The utilization of 18 simultaneously measured endpoints means that the entire system serves as a robust biological sensor for chemical hazard. The experimental design enabled us to describe global patterns of variation across tested compounds, evaluate the concordance of the available in vitro and in vivo phase 1 data with this study, highlight specific mechanisms/value-added/novel biology related to notochord development, and demonstrate that the developmental zebrafish detects adverse responses that would be missed by less comprehensive testing strategies.

The U.S. National Research Council issued Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A Vision and a Strategy in 2007 to challenge traditional approaches for toxicity testing. The report described the need to refocus toxicity testing on relevant human doses and on identifying the early molecular response pathways that are perturbed to produce toxicity. Application of this approach would replace reliance on primarily high-dose, gross phenotypic responses in high-cost, low-throughput mammalian models. The goal in focusing on molecular and cellular pathways that are targets for chemicals is to gain insights into toxic mechanisms underlying apical endpoints. To directly address this need and to help prioritize chemicals for testing, in 2008, the U.S. EPA National Center for Computational Toxicology (NCCT), National Toxicology Program, and National Human Genome Research Institute’s NIH Chemical Genomics Center developed a partnership, “Tox21” (http://epa.gov/ncct/Tox21/), to test a larger set of compounds (10 000) that were broadly characterized and may have toxicological concerns. In 2010, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration joined the partnership to bring together expertise in experimental toxicology, computational toxicology, high-throughput technologies, and animal models of human diseases.

As an additional effort, the EPA-NCCT developed the ToxCast program in 2007 to assess a large number of chemicals in a diverse set of in vitro assays. The long-term goal was to predict the potential toxicity of chemicals and to develop cost-effective approaches to prioritize the thousands of chemicals that have little to no hazard safety information. As a “Proof of Concept,” phase 1 of the ToxCast program was completed in 2009 and consisted of approximately 300 well-studied chemicals with existing toxicity information run across approximately 600 high-throughput in vitro assays (Judson et al., 2010). Phase 1 consisted primarily of pesticides, many having over 30 years of data from traditional toxicology methods and definitive toxicity endpoint(s) (ie, target organ, reproductive, or developmental). The ToxCast program established multidimensional, multiassay signatures to predict animal toxicity using the traditional toxicity data to gauge accuracy. Phase 2 is currently ongoing and consists of approximately 700 chemicals from a broad range of sources such as industrial and consumer products, food additives, “green” products, cosmetic-related chemicals, and failed pharmaceutical drugs. The traditional toxicity data are lacking in phase 2, but human clinical data and other toxicology studies are available to assess and test the performance of predictive models developed in phase 1.

Although there is a growing effort to utilize molecular and pathway-focused assays in toxicology, it has proven difficult to translate in vitro data to predict whole animal toxicity. The high-throughput screening (HTS) assays used in the ToxCast program included both biochemical and cell-based systems that investigated protein function or binding, transcriptional activity, fundamental cellular processes, and systemic readouts. Cultured cells lack biological complexity; they express limited gene products and intrinsically represent an artificial biological environment for testing. These inherent limitations have tempered some of the enthusiasm for the Tox21 initiatives.

The zebrafish is a small complex organism that is amenable to large-scale in vivo genetic and chemical studies (Pardo-Martin et al., 2010). Zebrafish have a short generation time and rapid development and short life cycle (Kimmel et al., 1995). The embryos develop externally and are transparent for the first few days of life, and due to their small size, only a small quantity of chemical is needed for a full evaluation of biological response. There is significant physiological and genetic homology between humans and zebrafish (70% gene homology), and approximately 84% of human genes known to be associated with human diseases are also present in zebrafish (Howe et al., 2013). The versatility of zebrafish makes it an ideal model to address Toxicity Testing for the 21st century, providing an essential bridge between in vitro and mammalian data. By combining the utility of the embryonic zebrafish as the first tier to identify potential toxicity and the application of HTS in vitro assays to gain insight into toxicity mechanisms, we can begin to address the paradigm shift in toxicity testing.

Here, we describe a rapid in vivo approach to discover chemical hazard potential using embryonic zebrafish. We examined all 1078 ToxCast phase 1 and 2 chemicals (1060 unique chemicals) for developmental and neurotoxicity in the embryonic zebrafish. Each chemical was tested in a broad concentration range spanning 4 orders of magnitude (6.4nM to 64μM) with multiple replicates at each concentration (n = 32). Simultaneous evaluation of 22 endpoints identified distinct patterns of chemical response that can help identify mechanistic pathways. By utilizing the zebrafish as a biological sensor, and these data as a reference set, we are better positioned to build predictive toxicity frameworks and accelerate chemical testing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

The chemical library consisted of 1078 EPA ToxCast phase 1 and 2 chemicals. There were 1060 unique chemicals from various sources, with 9 sets of embedded, blinded triplicate identifiers. The chemical library chemicals, quality control (QC) analysis, and structure data format files are available at http://www.epa.gov/NCCT/toxcast/chemicals.html. Stock solutions of all chemicals were provided in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 20mM in 96-well plates.

Chemical preparation.

For every 8 chemicals, 2 dilution plates were made. Dilution plate 1 consisted of the 8 chemicals diluted to 10mM with 100% DMSO and placed into columns 1 and 7 of a 96-well plate. A total of 5 chemical dilutions were made in the same plate (10-fold serial dilution) in columns 2–5 and 8–11. Dilution plate 2 was a 1:15 dilution of plate 1, with a concentration range of 0.064–640μM in 6.4% DMSO. This dilution plate was made using standard embryo medium (EM) (Westerfield, 2000). All dilution plates were stored at −20°C until 30min prior to exposure.

Zebrafish husbandry.

Tropical 5D wild-type adult zebrafish were housed in at an approximate density of 1000 per 100 gallon tank at the Sinnhuber Aquatic Research Laboratory, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. Each tank was kept at standard laboratory conditions of 28°C on a 14-h light/10-h dark photoperiod in fish water consisting of reverse osmosis water supplemented with a commercially available salt (Instant Ocean). Spawning funnels were placed into the tanks the night prior, and embryos were collected and staged (Kimmel et al., 1995). To increase bioavailability, the chorion was enzymatically removed using pronase (63.6mg/ml, ≥ 3.5U/mg, Sigma-Aldrich: P5147) at 4 hours post fertilization (hpf) using a custom automated dechorionator (Mandrell et al., 2012).

Chemical exposures.

Six hpf dechorionated embryos were placed 1 embryo per well in a 96-well plate prefilled with 90 μl of EM using automated embryo placement systems (AEPS) (Mandrell et al., 2012). Ten microliters of each row of dilution plate 2 was added to 2 exposure plates. The final DMSO concentration used was 0.64% (vol/vol). Thirty-two embryos were also exposed to 5μM trimethyltin chloride (positive control). Plates were sealed to prevent evaporation and foil covered to reduce light exposure and kept in a 28°C incubator. Embryos were statically exposed until 120 hpf.

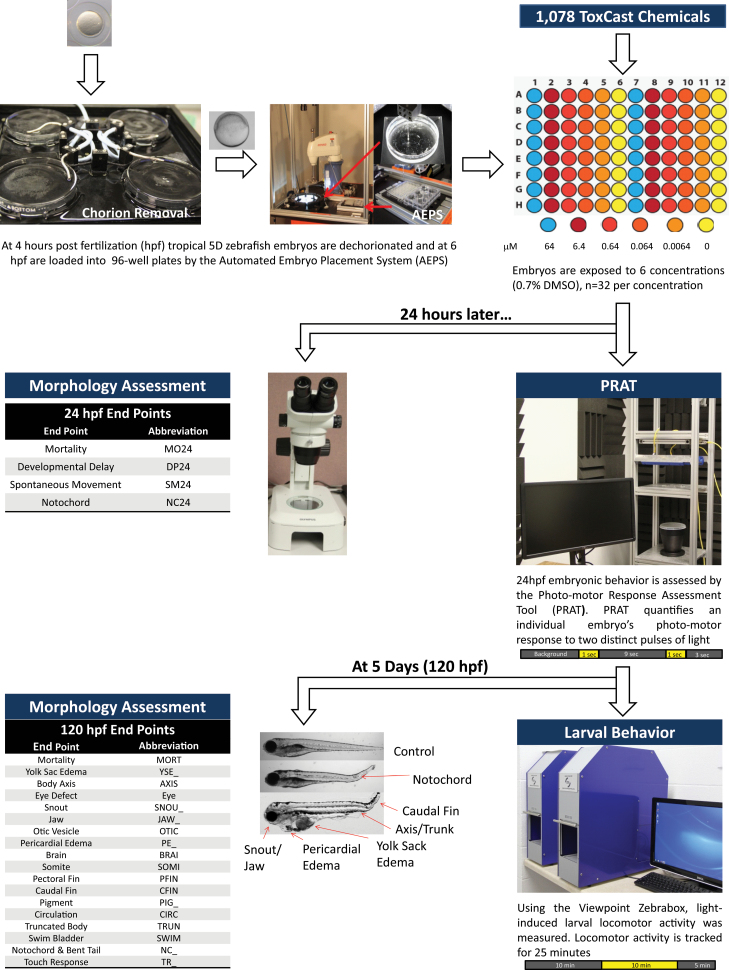

At 24 hpf, embryos were assessed for photomotor response using a custom photomotor response analysis tool (PRAT) and for 4 developmental toxicity endpoints (MO24: mortality at 24 hpf, DP: developmental progression, SM: spontaneous movement, and NC: notochord distortion) (Truong et al., 2011). At 120 hpf, locomotor activity was measured using Viewpoint Zebralab (Saili et al., 2012; Truong et al., 2012) and assessed for 18 endpoints (Truong et al., 2011). Zebrafish acquisition and analysis program (ZAAP), a custom program designed to inventory, acquire, and manage zebrafish data, was used to collect developmental endpoints as either present or absent (ie, binary responses were recorded). If mortality occurred for an embryo (at either 24 or 120 hpf), the nonmortality endpoints were not measured. The experimental approach is summarized in Figure 1.

FIG. 1.

Experimental approach for screening developmental and neurotoxicity for 1078 ToxCast chemicals. Embryos were dechorionated at 4 hours post fertilization (hpf), and plated at 6 using automated embryo placement systems. After which, 1 chemical was added to 2 plates, at 6 concentrations (0.0064–64μM, 10-fold serial dilution), n = 16 per plate × 2 plates. The embryos were statically exposed to chemical until 120 hpf. At 24 hpf, photomotor response data were collected, and 4 developmental endpoints were assessed. At 120 hpf, larval behavior and 18 morphological and behavioral endpoints were assessed. Abbreviation: DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

Analysis.

All statistical analysis was performed using code developed in R (R Development Core Team 2013). The data used were binary incidences recorded for each endpoint from ZAAP (as described above), plus associated plate and well-location information. This information was used to test for confounding plate, well, and chemical effects across all controls and to identify outliers. Considering controls (concentration = 0), there were no statistically significant effects by plate or well location. There were slight differences in control incidence by endpoint and chemical, which were accounted for in our analysis method (described below). Outliers were defined as chemicals having an incidence rate greater than 3 SDs from the mean rate in controls across multiple endpoints. A total of 20 chemicals (out of 1078 unique substance identifiers) were identified as outliers and rerun. No significant batch effects were found when these rerun data were merged with the rest of data.

To characterize responses for each chemical endpoint, we computed a lowest effect level (LEL) in micromolars as the concentration at which the incidence exceeded a significance threshold over the background (control) incidence rate. Because the endpoints are binary and replicates are measured in separate wells, the 0/1 responses for each chemical-endpoint-concentration-replicate combination translate to a series (n = 32) of Bernoulli trials, or “coin-flips.” Therefore, the LEL significance threshold was estimated using a binomial test, which provided a straightforward method to adjust for plate and/or chemical effects and the pooling/separation of controls. Given the experimental design, the binomial maximized power versus a typical logistic/curve-fit approach by accounting for the falsely “nonmonotonic” responses occurring when the MORT endpoint led to missing specific endpoint measurements at higher concentrations. Because background incidence rate varied slightly across chemicals and endpoints, the significance threshold (x) was determined independently from the binomial distribution function for each chemical-endpoint pair as:

where n c,e = number of controls (trials) for this chemical, for this endpoint; p c,e = observed incidence (positive responses) in controls for this chemical, for this endpoint.

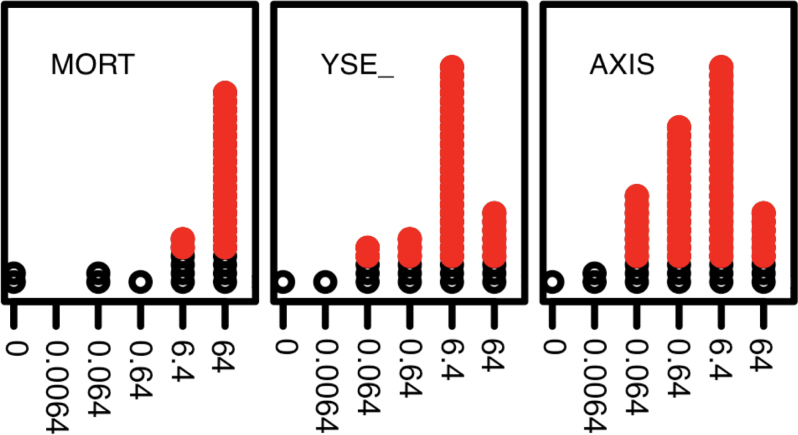

As illustrated in Figure 2, the recorded LEL was the lowest concentration at which the observed incidence exceeded the significance threshold (p ≤ .05) defined above. Figure 2 also illustrates the situation in which high MORT incidence reduced the number of specific endpoint measurements at coincident concentrations.

FIG. 2.

Estimation of LEL from concentration-response data. The concentration-response plots for 3 endpoints {MORT, YSE, AXIS} are shown for the chemical ziram. The horizontal axis shows the 6 concentrations tested (0 = control). For each concentration, the incidence (number of responses = 1) across all 32 replicates is plotted as stacked points. The points exceeding the binomial significance threshold for each endpoint are colored red. Abbreviation: LEL, lowest effect level.

The chemical-physical properties, the log of the octanol/water partition coefficient (Log K ow) and bioconcentration factor (BCF), were estimated using EPISuite v4.11 (http://www.epa.gov/opptintr/exposure/pubs/episuite.htm). The SMILES notation was inputted into EPISuite, which returned estimates for 919 chemicals. Standard regression and t tests were performed to assess the association between these properties and assay activity across the entire chemical set.

The publicly available in vitro and in vivo ToxCast phase 1 data (http://www.epa.gov/ncct/toxcast/data.html) were used to evaluate concordance with zebrafish results. Both absolute counts of agreement and Cohen’s kappa statistic (Cohen, 1960) were used to quantify the concordance between each zebrafish endpoint and ToxCast in vitro assays or ToxRefDB (http://www.epa.gov/ncct/toxrefdb/) in vivo results. (The set of 293 chemicals in the comparison set varied because not all chemicals were tested for each endpoint.) In addition to the individual zebrafish endpoints, all concordance analyses include results for the aggregate ANY_ZF_ENDPOINT and ANY_ZF_ENDPOINT_EXCEPT_MORT vectors.

RESULTS

Using Embryonic Zebrafish in a High-Throughput Manner

To evaluate the entire ToxCast phase 1 and 2 chemical set in a high-throughput manner with multiple replicates (n = 32) and 6 concentrations (6.4nM to 64μM, 10-fold serial dilution), the embryonic zebrafish testing paradigm was streamlined and automated. Adult zebrafish (approximately 2000) were housed in large 100 gallon tanks allowing for easy spawning and embryo collection (approximately 30 000/day). Embryos were enzymatically dechorionated using pronase on an automated dechorionator at 4 hpf and placed into individual wells of a 96-well plates using AEPS (15min/plate) as described in Mandrell et al. (2012). Chemicals were added using an automated liquid handler to ensure efficiency, accuracy, and precision. Exposed chemical plates were barcoded, sealed, and covered with aluminum foil to reduce evaporation and light exposure and kept at 28°C, the optimal temperature for zebrafish development, for the duration of the experiment.

Embryonic zebrafish were continuously exposed to each of the 1078 ToxCast chemicals from 6 to 120 hpf. At 24 hpf, embryos were assessed for viability, developmental delay, axial bends, and for the asynchronous tail movement response to a pulse of bright, visible light (Kokel et al., 2010) using PRAT and again at 120 hpf, for locomotor activity, using Viewpoint Zebrabox, and 18 developmental effects (MORT: mortality at 120 hpf, YSE: yolk sac edema, AXIS: bent body axis, EYE: eye, SNOU: snout, JAW: jaw, OTIC: otic, PE: pericardial edema, BRAI: brain, SOMI: somite, PFIN: pectoral fin, CFIN: caudal fin, CIRC: circulation, PIG: pigmentation, TRUN: trunk length, SWIM: swim bladder, NC: notochord distortion, and TR: alterations in touch response) (Fig. 1). To conduct QC and efficiently manage the data, a customized program, ZAAP, was created, which allowed for real time record keeping of each exposure plate (barcode), databasing of all acquired data using MySQL, and the ability to QC the data immediately after evaluation. Implementation of ZAAP considerably reduced data recording time, streamlined data entry, and reduced the chance of human error. Barcodes for exposed plates were developed to match the identity of the master chemical plate as another means of nonbias testing and inventoried in ZAAP to provide the ability to match barcodes to chemical IDs after all data were collected.

Global Response Patterns

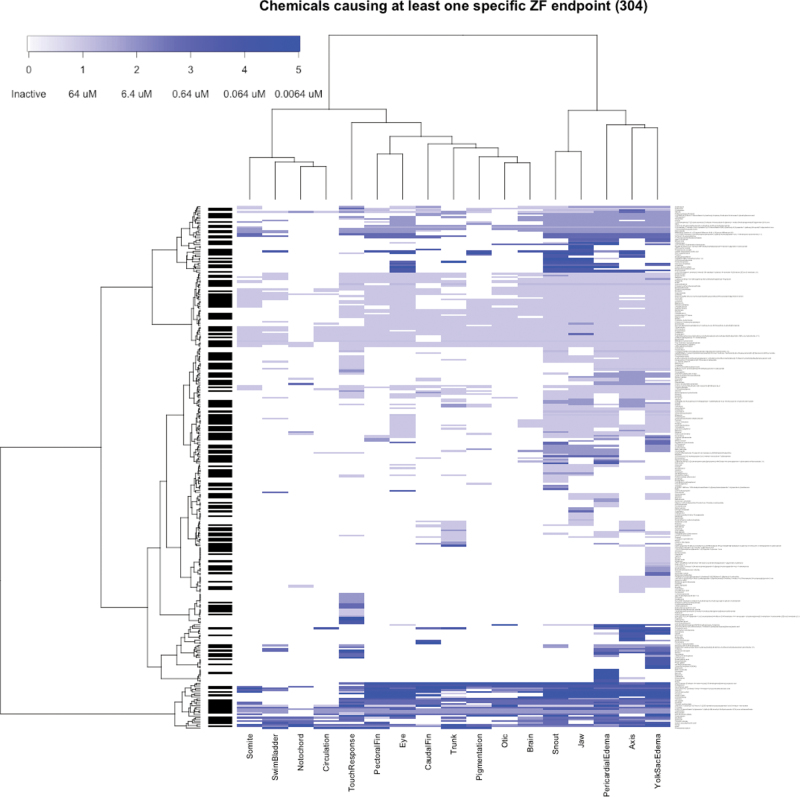

To summarize the concentration response data for each endpoint, the LELs for all chemical-endpoint combinations are presented in graphical form in Supplementary Figure 1 and recorded in tabular form in Supplementary Table 1. An LEL is only recorded for those chemical endpoints considered a “hit” (see Materials and Methods section for details of identifying active compounds). Ziram is a graphical example of a chemical that was a hit for 3 endpoints (Fig. 2). Across all chemicals, 304 caused significant responses in at least 1 specific zebrafish endpoint (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Bicluster heat map of chemicals with at least 1 hit in a specific developmental endpoint. The responses were clustered using Ward’s method by Euclidean distance between LELs. The heatmap is colored so that increasingly potent LEL responses are darker shades of blue, with inactive responses having no color. Many of the 304 chemicals hitting at least 1 specific endpoint also caused embryonic lethality, indicated by the black sidebar. Abbreviation: LEL, lowest effect level.

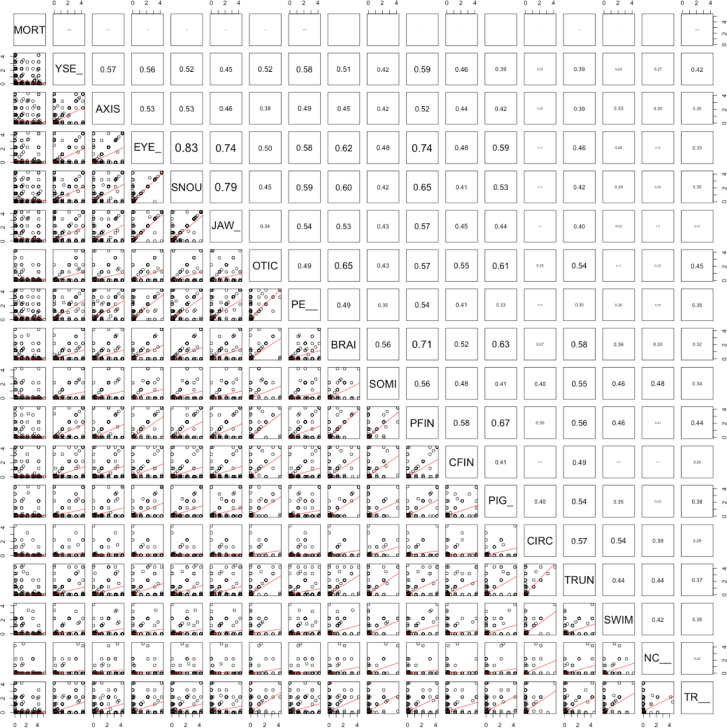

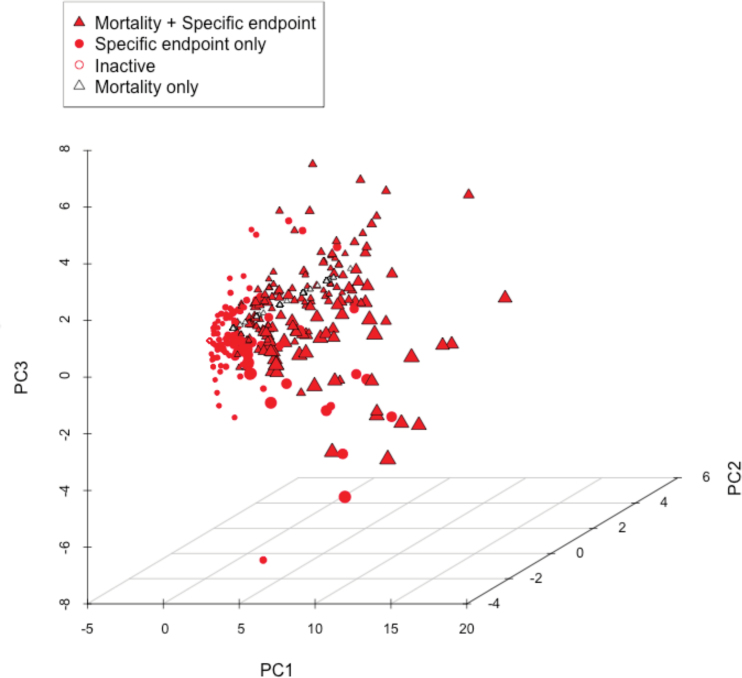

The endpoint-endpoint correlation across all chemicals is illustrated in Figure 4. Among endpoints with high numbers of observed hits, mortality response was the only one not highly correlated to any other endpoint. The endpoint-wise co-occurrences are given in Supplementary Table 2 with the observed number of positive responses for each endpoint along the diagonal. Principal components analysis showed that much of the salient variance was the separation between chemicals that either induced no response, caused only mortality, or were associated with multiple endpoints (Fig. 5). This result was due, in part, to the predilection for some endpoints to positively influence the observation of others. Interendpoint correlation underscored the utility of the assay system as a comprehensive sensor, where such correlations benefit assay sensitivity. Beyond these first 3 axes of variation, clusters of specific endpoint responses emerged such as notochord distortion and lower axial bend.

FIG. 4.

Correlation between endpoints. The 2 halves of the endpoint-endpoint correlation plot show the linear correlation between -log(LEL) results. The upper panel shows the correlation, r, with increasingly large font as the value increases. The lower panel plots the results summarized in the upper panel. Abbreviation: LEL, lowest effect level.

FIG. 5.

Sources of variation visualized by PCA. PCA was performed on the LEL matrix of all 1060 chemicals. Plotting symbols annotate chemicals into activity categories: mortality only (empty triangle), mortality plus specific endpoint(s) (black triangle with red filling), specific endpoint(s) only (red solid circle), or inactive (hollow red circle). The points are scaled according to how many specific endpoint LELs are associated with each chemical. Abbreviations: LEL, lowest effect level; PCA, principal components analysis.

Developmental Zebrafish Assay System as a Comprehensive Bioactivity Sensor

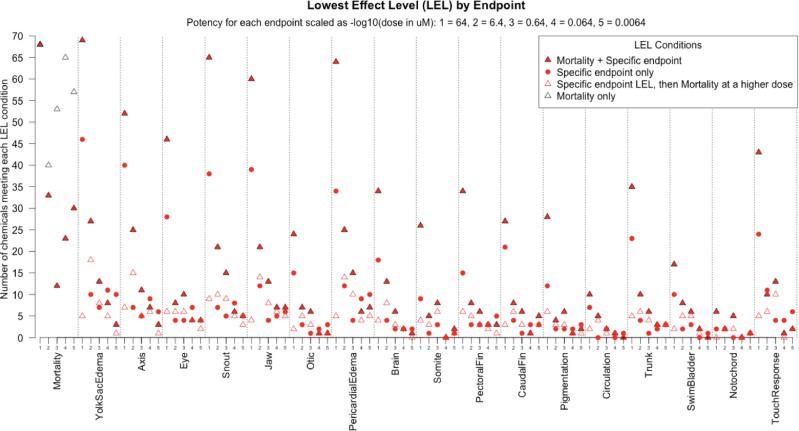

In this analysis, the LEL for a particular chemical may occur as mortality in the absence of specific endpoints, mortality plus specific endpoints, specific endpoints followed by mortality at higher doses, or specific endpoints only (Fig. 6). This conditional display of LELs showed that assessing multiple endpoints in conjunction with mortality was necessary to identify the most potent adverse effect(s) for a given chemical. Mortality alone was insufficient; there were chemicals where the LEL occurred at a sublethal dose or exhibited no observed lethality. Specific endpoints alone were also insufficient, as several LELs were established based upon mortality. Moreover, LELs are observed for all specific endpoints, rather than being unique to a particular developmental endpoint. These specific LELs may be early sensors (red outlined triangles at low doses in Fig. 6) for serious developmental effects.

FIG. 6.

Analysis of lowest effect level (LEL) by endpoint. The minimum LEL for each condition was computed for each concentration (plotted in order of increasing 10-fold potency, from 64 to 0.0064μM, notated 1–5) and endpoint (18 total). The vertical axis counts the number of chemicals meeting each concentration-condition-endpoint. Four LEL conditions were evaluated: mortality only (empty triangle), a specific endpoint LEL then mortality at a higher dose (red empty triangle), a specific endpoint only (red circle), or mortality and a specific endpoint occurring (black triangle with red filling).

Zebrafish Assay Performance Against In Vivo Animal Toxicity

Concordance analysis with in vivo animal toxicity data captured in ToxRefDB and our data identified mortality as having the greatest concordance with developmental rat or rabbit maternal-related effects (> 85 chemicals, DEV_rat/rabbit_Maternal_GeneralMaternal/General_Maternal_Systemic). When the analysis was completed for “any” zebrafish endpoint, there were 190 chemicals that were highly concordant (Table 1A). Of these 8 highly concordant ToxRefDB endpoints, developmental maternal rabbit studies (both general and systemic) had a high percentage of concordance (approximately 60%). The pregnancy-related rabbit studies had the lowest concordance of the 8 endpoints with 46% concordance. Zebrafish “any” developmental endpoint (including mortality) was concordant with liver endpoints for chronic mouse and rat (CHR_Mouse/Rat) reproductive and multigenerational rat reproductive studies (MGR_rat). There was a high concordance (25–68 chemical incidences, > 60% concordance) for liver hypertrophy, necrosis, tumors, and preneoplastic lesions and kidney pathology, and “any lesions” (Table 1B).

TABLE 1.

Concordance with Toxrefdb. A) Chemicals Highly Correlated with any Zebrafish Endpoint and ToxRefDB Maternal or Pregnancy Studies with Chemical LEL per each Toxrefdb Endpoint. B) Concordance of any Zf Endpoint with Liver and Kidney Effects Found in ToxRefDB. Cells with – Denotes Negative Correlation.

| A | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TestSubstance_CASRN | EPA_SAMPLE_ID | TestSubstance_ChemicalName | DEV_Rabbit | DEV_Rat | |||||||

| Developmental_Pregnancy Related | Developmental_Pregnancy Related_Embryo FetalLoss | Maternal | Maternal_General Maternal | Maternal_General Maternal_Systemic | Maternal_Pregnancy Related | Maternal_Pregnancy Related_Maternal PregLoss | Prenatal_Loss | Prenatal_Loss | |||

| 21564-17-0 | TX006533 | 2-(Thiocyanomethylthio) benzothiazole | -- | -- | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 4 | 4 |

| 94-74-6 | TX001537 | 2-Methyl-4- chlorophenoxyacetic acid | -- | -- | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 4 | -- |

| 90-43-7 | TX002844 | 2-Phenylphenol | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | 100 | 250 | 250 | 4 | -- |

| 94-75-7 | TX003702 | 24-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid | -- | -- | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 4 | -- |

| 55406-53-6 | TX000878 | 3-Iodo-2-propynyl-N- butylcarbamate | 40 | 40 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 4 | -- |

| 94-82-6 | TX011588 | 4-(24-Dichlorophenoxy)butyric acid | -- | -- | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 4 | 4 |

| 30560-19-1 | TX000715 | Acephate | -- | -- | 10 | -- | -- | 10 | 10 | 5 | -- |

| 135410-20-7 | TX000801 | Acetamiprid | -- | -- | 30 | 30 | 30 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 34256-82-1 | TX000687 | Acetochlor | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 3 |

| 15972-60-8 | TX000922 | Alachlor | -- | -- | 150 | 150 | 150 | -- | -- | -- | 3 |

| 834-12-8 | TX000947 | Ametryn | -- | -- | 60 | 60 | 60 | -- | -- | -- | 4 |

| 3337-71-1 | TX000986 | Asulam | -- | -- | 750 | 750 | 750 | -- | -- | -- | 3 |

| 1912-24-9 | TX001546 | Atrazine | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 4 | 5 |

| 35575-96-3 | TX000750 | Azamethiphos | -- | -- | 12 | 12 | 12 | 18 | 18 | 5 | -- |

| 22781-23-3 | TX001604 | Bendiocarb | -- | -- | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 1861-40-1 | TX000910 | Benfluralin | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | 100 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 17804-35-2 | TX001588 | Benomyl | -- | -- | 180 | 180 | 180 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 741-58-2 | TX000710 | Bensulide | -- | -- | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 4 | -- |

| 82657-04-3 | TX000966 | Bifenthrin | -- | -- | 4 | 4 | 4 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 10043-35-3 | TX003540 | Boric acid | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 4 | 4 |

| 188425-85-6 | TX009148 | Boscalid | -- | -- | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 3 | -- |

| 314-40-9 | TX000840 | Bromacil | -- | -- | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 4 | -- |

| 69327-76-0 | TX000773 | Buprofezin | -- | -- | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 4 | 3 |

| 23184-66-9 | TX000759 | Butachlor | 250 | 250 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 4 | -- |

| 134605-64-4 | TX001419 | Butafenacil | -- | -- | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 3 | -- |

| 33629-47-9 | TX003363 | Butralin | -- | -- | 135 | 135 | 135 | -- | -- | -- | 3 |

| 2008-41-5 | TX002809 | Butylate | -- | -- | 500 | 500 | 500 | -- | -- | -- | 3 |

| 2425-06-1 | TX001555 | Captafol | -- | -- | 16 | 16 | 16 | 50 | 50 | 4 | -- |

| 63-25-2 | TX000856 | Carbaryl | -- | -- | 50 | 50 | 50 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 5234-68-4 | TX000965 | Carboxin | -- | -- | 375 | -- | -- | 375 | 375 | 3 | -- |

| 128639-02-1 | TX001409 | Carfentrazone-ethyl | -- | -- | 300 | 300 | 300 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 54593-83-8 | TX001582 | Chlorethoxyfos | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 |

| 1698-60-8 | TX000898 | Chloridazon | -- | -- | 165 | 165 | 165 | 495 | 495 | 3 | -- |

| 2675-77-6 | TX001571 | Chloroneb | -- | -- | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 1897-45-6 | TX003698 | Chlorothalonil | -- | -- | 20 | 20 | 20 | -- | -- | -- | 3 |

| 101-21-3 | TX001551 | Chlorpropham | -- | -- | 250 | 250 | 250 | 500 | 500 | 3 | -- |

| 105512-06-9 | TX000951 | Clodinafop-propargyl | -- | -- | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 4 | -- |

| 81777-89-1 | TX000757 | Clomazone | -- | -- | 700 | 700 | 700 | 700 | 700 | 3 | -- |

| 101-10-0 | TX000880 | Cloprop | -- | -- | 200 | 200 | 200 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 1702-17-6 | TX000945 | Clopyralid | -- | -- | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 4 | 4 |

| 120-32-1 | TX209149 | Clorophene | -- | -- | 100 | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | 4 | -- |

| 210880-92-5 | TX000809 | Clothianidin | -- | -- | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 4 | -- |

| 113136-77-9 | TX001406 | Cyclanilide | -- | -- | 30 | 30 | 30 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 1134-23-2 | TX000702 | Cycloate | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | 100 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 68359-37-5 | TX000689 | Cyfluthrin | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 4 | 4 |

| 122008-85-9 | TX001431 | Cyhalofop-butyl | -- | -- | 200 | 1000 | 1000 | 200 | 200 | 4 | -- |

| 57966-95-7 | TX001425 | Cymoxanil | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 4 |

| 52315-07-8 | TX000754 | Cypermethrin | -- | -- | 450 | 450 | 450 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 94361-06-5 | TX011580 | Cyproconazole | -- | -- | 50 | 50 | 50 | -- | -- | -- | 5 |

| 121552-61-2 | TX000779 | Cyprodinil | -- | -- | 400 | 400 | 400 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 66215-27-8 | TX000862 | Cyromazine | -- | -- | 30 | 30 | 30 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 533-74-4 | TX000828 | Dazomet | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 4 | -- |

| 333-41-5 | TX000695 | Diazinon | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 4 | 4 |

| 1918-00-9 | TX000852 | Dicamba | -- | -- | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 4 | 3 |

| 62-73-7 | TX001608 | Dichlorvos | -- | -- | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 | -- |

| 145701-21-9 | TX001540 | Diclosulam | -- | -- | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 4 | -- |

| 115-32-2 | TX001420 | Dicofol | -- | -- | 4 | 4 | 4 | 40 | 40 | 4 | -- |

| 141-66-2 | TX001418 | Dicrotophos | -- | -- | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | -- |

| 119446-68-3 | TX000785 | Difenoconazole | -- | -- | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 4 | 4 |

| 75-60-5 | TX001570 | Dimethylarsinic acid | -- | -- | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 4 | -- |

| 83657-24-3 | TX001542 | Diniconazole | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 4 |

| 136-45-8 | TX000876 | Dipropyl pyridine-25-dicarboxylate | -- | -- | 350 | 350 | 350 | 350 | 350 | 3 | -- |

| 6385-62-2 | TX001448 | Diquat dibromide monohydrate | -- | -- | 3 | 3 | 3 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 298-04-4 | TX001611 | Disulfoton | -- | -- | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 | -- |

| 97886-45-8 | TX001408 | Dithiopyr | -- | -- | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 155569-91-8 | TX001598 | Emamectin benzoate | -- | -- | 6 | 6 | 6 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 115-29-7 | TX000953 | Endosulfan | -- | -- | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 5 |

| 66230-04-4 | TX000700 | Esfenvalerate | -- | -- | 3 | 3 | 3 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 16672-87-0 | TX001533 | Ethephon | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 4 | -- |

| 26225-79-6 | TX000838 | Ethofumesate | -- | -- | 300 | 3000 | 3000 | 300 | 300 | 4 | -- |

| 153233-91-1 | TX009157 | Etoxazole | -- | -- | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 2593-15-9 | TX000845 | Etridiazole | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 4 | 4 |

| 131807-57-3 | TX001402 | Famoxadone | -- | -- | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 3 | -- |

| 161326-34-7 | TX000803 | Fenamidone | -- | -- | 30 | 30 | 30 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 22224-92-6 | TX011589 | Fenamiphos | -- | -- | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 6 |

| 114369-43-6 | TX000969 | Fenbuconazole | -- | -- | 30 | 30 | 30 | 60 | 60 | 4 | 4 |

| 126833-17-8 | TX000761 | Fenhexamid | -- | -- | 300 | 300 | 300 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 122-14-5 | TX000916 | Fenitrothion | -- | -- | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 5 | -- |

| 66441-23-4 | TX000781 | Fenoxaprop-ethyl | -- | -- | 50 | -- | -- | 50 | 50 | 4 | 4 |

| 72490-01-8 | TX000959 | Fenoxycarb | -- | -- | 200 | 200 | 200 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 39515-41-8 | TX000696 | Fenpropathrin | -- | -- | 12 | 12 | 12 | -- | -- | -- | 5 |

| 55-38-9 | TX000944 | Fenthion | -- | -- | 3 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 5 |

| 79241-46-6 | TX001441 | Fluazifop-P-butyl | -- | -- | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 4 | 0 |

| 79622-59-6 | TX000777 | Fluazinam | -- | -- | 4 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 131341-86-1 | TX001417 | Fludioxonil | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | 100 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 142459-58-3 | TX000767 | Flufenacet | -- | -- | 125 | 125 | 125 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 188489-07-8 | TX011611 | Flufenpyr-ethyl | -- | -- | 200 | 1000 | 1000 | 200 | 200 | 4 | -- |

| 98967-40-9 | TX001577 | Flumetsulam | -- | -- | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 3 | -- |

| 87546-18-7 | TX001554 | Flumiclorac-pentyl | -- | -- | 800 | -- | -- | 800 | 800 | 3 | -- |

| 103361-09-7 | TX001405 | Flumioxazin | -- | -- | 3000 | 3000 | 3000 | -- | -- | -- | 5 |

| 2164-17-2 | TX000997 | Fluometuron | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 4 | 3 |

| 361377-29-9 | TX000677 | Fluoxastrobin | -- | -- | 400 | 400 | 400 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 69377-81-7 | TX000742 | Fluroxypyr | -- | -- | 1000 | -- | -- | 1000 | 1000 | 3 | 3 |

| 85509-19-9 | TX000669 | Flusilazole | -- | -- | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 4 | 4 |

| 66332-96-5 | TX011593 | Flutolanil | -- | -- | 200 | -- | -- | 200 | 200 | 4 | -- |

| 23422-53-9 | TX001589 | Formetanate hydrochloride | -- | -- | 15 | 15 | 15 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 98886-44-3 | TX006534 | Fosthiazate | -- | -- | 2 | 2 | 2 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 79983-71-4 | TX000667 | Hexaconazole | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | 100 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 51235-04-2 | TX000957 | Hexazinone | -- | -- | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 4 | 3 |

| 114311-32-9 | TX000811 | Imazamox | -- | -- | 600 | 600 | 600 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 104098-48-8 | TX002846 | Imazapic | -- | -- | 500 | 500 | 500 | 700 | 700 | 3 | -- |

| 81335-77-5 | TX000822 | Imazethapyr | -- | -- | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 3 | -- |

| 138261-41-3 | TX000738 | Imidacloprid | 72 | 72 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 72 | 72 | 4 | -- |

| 173584-44-6 | TX001442 | Indoxacarb | -- | -- | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | -- | -- | 0 | -- |

| 36734-19-7 | TX000864 | Iprodione | -- | -- | 60 | 60 | 60 | 200 | 200 | 4 | -- |

| 82558-50-7 | TX000661 | Isoxaben | -- | -- | 1000 | -- | -- | 1000 | 1000 | 3 | 3 |

| 141112-29-0 | TX000679 | Isoxaflutole | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 4 | -- |

| 77501-63-4 | TX000902 | Lactofen | -- | -- | 20 | 20 | 20 | -- | -- | -- | 4 |

| 58-89-9 | TX001547 | Lindane | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 5 |

| 330-55-2 | TX000967 | Linuron | 100 | 100 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 100 | 100 | 4 | 4 |

| 121-75-5 | TX009153 | Malathion | -- | -- | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 4 | -- |

| 8018-01-7 | TX209150 | Mancozeb | -- | -- | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 4 | 3 |

| 24307-26-4 | TX000971 | Mepiquat chloride | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | 100 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 57837-19-1 | TX001424 | Metalaxyl | -- | -- | 300 | 300 | 300 | -- | -- | -- | 3 |

| 10265-92-6 | TX000900 | Methamidophos | -- | -- | 1 | 1 | 1 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 950-37-8 | TX009154 | Methidathion | -- | -- | 12 | 12 | 12 | -- | -- | -- | 6 |

| 16752-77-5 | TX000890 | Methomyl | -- | -- | 16 | 16 | 16 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 6317-18-6 | TX001619 | Methylene bis(thiocyanate) | -- | -- | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | -- |

| 51218-45-2 | TX000793 | Metolachlor | -- | -- | 360 | 360 | 360 | -- | -- | -- | 3 |

| 21087-64-9 | TX003710 | Metribuzin | -- | -- | 30 | 30 | 30 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 7786-34-7 | TX001580 | Mevinphos | -- | -- | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 |

| 113-48-4 | TX002804 | MGK-264 | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | 100 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 2212-67-1 | TX002810 | Molinate | -- | -- | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 4 | 4 |

| 88671-89-0 | TX000771 | Myclobutanil | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 4 | -- |

| 300-76-5 | TX000721 | Naled | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 4 |

| 1929-82-4 | TX000872 | Nitrapyrin | -- | -- | 30 | 30 | 30 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 134-62-3 | TX000868 | NN-Diethyl-3-methylbenzamide | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 3 |

| 27314-13-2 | TX000708 | Norflurazon | -- | -- | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 4 | -- |

| 19044-88-3 | TX211586 | Oryzalin | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 4 | 4 |

| 19666-30-9 | TX000934 | Oxadiazon | -- | -- | 60 | 60 | 60 | 180 | 180 | 4 | 4 |

| 23135-22-0 | TX000763 | Oxamyl | -- | -- | 2 | 2 | 2 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 42874-03-3 | TX000752 | Oxyfluorfen | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 4.04 | -- |

| 76738-62-0 | TX000723 | Paclobutrazol | -- | -- | 125 | 125 | 125 | -- | -- | 0 | -- |

| 219714-96-2 | TX006525 | Penoxsulam | -- | -- | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 4.12 | -- |

| 82-68-8 | TX001544 | Pentachloronitrobenzene | -- | -- | 125 | 125 | 125 | 250 | 250 | 3.60 | -- |

| 52645-53-1 | TX000949 | Permethrin | -- | -- | 600 | 600 | 600 | 1200 | 1200 | 2.92 | -- |

| 2310-17-0 | TX000955 | Phosalone | -- | -- | 10 | 20 | 20 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 4.78 |

| 51-03-6 | TX011594 | Piperonyl butoxide | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | 100 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 23103-98-2 | TX000736 | Pirimicarb | -- | -- | 60 | 60 | 60 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 23031-36-9 | TX001426 | Prallethrin | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | 100 | -- | -- | -- | 3.52 |

| 29091-21-2 | TX001421 | Prodiamine | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | 100 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 41198-08-7 | TX001594 | Profenofos | -- | -- | 60 | 60 | 60 | -- | -- | -- | 3.92 |

| 25606-41-1 | TX001435 | Propamocarb hydrochloride | -- | -- | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 3.52 | 3.13 |

| 709-98-8 | TX001536 | Propanil | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 4 | -- |

| 2312-35-8 | TX001557 | Propargite | -- | -- | 8 | 8 | 8 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 139-40-2 | TX001549 | Propazine | -- | -- | 10 | 10 | 10 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 31218-83-4 | TX001003 | Propetamphos | -- | -- | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 5.09 | -- |

| 60207-90-1 | TX000926 | Propiconazole | -- | -- | 250 | 250 | 250 | 400 | 400 | 3.39 | 3.52 |

| 114-26-1 | TX001548 | Propoxur | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 4.52 | 4.57 |

| 181274-15-7 | TX000769 | Propoxycarbazone-sodium | 1000 | 1000 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 3 | -- |

| 123312-89-0 | TX000894 | Pymetrozine | 125 | 125 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 125 | 125 | 3.90 | -- |

| 175013-18-0 | TX000834 | Pyraclostrobin | 20 | 20 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 20 | 20 | 4.69 | -- |

| 129630-19-9 | TX000977 | Pyraflufen-ethyl | -- | -- | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 4.22 | -- |

| 96489-71-3 | TX001583 | Pyridaben | -- | -- | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 15 | 15 | 4.82 | -- |

| 53112-28-0 | TX000725 | Pyrimethanil | -- | -- | 45 | 45 | 45 | 300 | 300 | 3.52 | -- |

| 95737-68-1 | TX000973 | Pyriproxyfen | -- | -- | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 3.52 | 3 |

| 123343-16-8 | TX001433 | Pyrithiobac-sodium | -- | -- | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 3 | 2.74 |

| 84087-01-4 | TX000712 | Quinclorac | 600 | 600 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 600 | 600 | 3.22 | 3.36 |

| 124495-18-7 | TX000657 | Quinoxyfen | -- | -- | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 3.69 | -- |

| 10453-86-8 | TX005545 | Resmethrin | -- | -- | 100 | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | 4 | -- |

| 28434-00-6 | TX001603 | S-Bioallethrin | -- | -- | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 3.52 | 3.71 |

| 759-94-4 | TX003535 | S-Ethyl dipropylthiocarbamate | -- | -- | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 3.52 | 3.52 |

| 74051-80-2 | TX001414 | Sethoxydim | -- | -- | 400 | 400 | 400 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 122-34-9 | TX001534 | Simazine | -- | -- | 5 | 5 | 5 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 148477-71-8 | TX000789 | Spirodiclofen | -- | -- | 300 | 300 | 300 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 118134-30-8 | TX000732 | Spiroxamine | -- | -- | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 4.09 | -- |

| 122836-35-5 | TX001447 | Sulfentrazone | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 3.60 | 4.30 |

| 119168-77-3 | TX001429 | Tebufenpyrad | -- | -- | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 4.39 | -- |

| 96182-53-5 | TX001623 | Tebupirimfos | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 6.52 | 6.12 |

| 79538-32-2 | TX000659 | Tefluthrin | -- | -- | 3 | 3 | 3 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 149979-41-9 | TX000740 | Tepraloxydim | -- | -- | 180 | 180 | 180 | -- | -- | -- | 3.44 |

| 112281-77-3 | TX001430 | Tetraconazole | -- | -- | 30 | 30 | 30 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 148-79-8 | TX003697 | Thiabendazole | -- | -- | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 3.22 | -- |

| 111988-49-9 | TX000673 | Thiacloprid | -- | -- | 10 | 10 | 10 | 45 | 45 | 4.34 | 4.30 |

| 153719-23-4 | TX000730 | Thiamethoxam | -- | -- | 50 | 50 | 50 | 150 | 150 | 3.821 | -- |

| 117718-60-2 | TX001432 | Thiazopyr | -- | -- | 175 | 175 | 175 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 51707-55-2 | TX000704 | Thidiazuron | -- | -- | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 3.90 | -- |

| 28249-77-6 | TX000783 | Thiobencarb | -- | -- | 200 | 200 | 200 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 59669-26-0 | TX001543 | Thiodicarb | -- | -- | 40 | 40 | 40 | -- | -- | -- | 4 |

| 87820-88-0 | TX000933 | Tralkoxydim | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 4 | 3.52 |

| 43121-43-3 | TX000908 | Triadimefon | -- | -- | 120 | 120 | 120 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 55219-65-3 | TX211585 | Triadimenol | -- | -- | 125 | 125 | 125 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 78-48-8 | TX001538 | Tribufos | -- | -- | 9 | 9 | 9 | -- | -- | -- | 4.55 |

| 3380-34-5 | TX211587 | Triclosan | -- | -- | 150 | 150 | 150 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 141517-21-7 | TX000765 | Trifloxystrobin | -- | -- | 50 | 50 | 50 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 199119-58-9 | TX011610 | Trifloxysulfuron-sodium | -- | -- | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 3.60 | -- |

| 68694-11-1 | TX001446 | Triflumizole | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | 100 | -- | -- | -- | 4.45 |

| 1582-09-8 | TX000912 | Trifluralin | 500 | 500 | 225 | 225 | 225 | 225 | 225 | 3.30 | 3.30 |

| 131983-72-7 | TX009151 | Triticonazole | -- | -- | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 4.30 | -- |

| B | |||||||||||

| ToxRefDB Endpoints | Any_ZF_Endpoint | Incidence Count | % Concordance | ||||||||

| DEV_rabbit_Developmental_PregnancyRelated | 12 | 26 | 46.15 | ||||||||

| DEV_rabbit_Developmental_PregnancyRelated_EmbryoFetalLoss | 12 | 26 | 46.15 | ||||||||

| DEV_rabbit_Maternal | 121 | 203 | 59.61 | ||||||||

| DEV_rabbit_Maternal_GeneralMaternal | 115 | 194 | 59.28 | ||||||||

| DEV_rabbit_Maternal_GeneralMaternal_Systemic | 115 | 194 | 59.28 | ||||||||

| DEV_rabbit_Maternal_PregnancyRelated | 72 | 126 | 57.14 | ||||||||

| DEV_rabbit_Maternal_PregnancyRelated_MaternalPregLoss | 72 | 126 | 57.14 | ||||||||

| DEV_rabbit_Prenatal_Loss | 72 | 126 | 57.14 | ||||||||

| DEV_rat_Prenatal_Loss | 48 | 82 | 58.54 | ||||||||

| CHR_Mouse_KidneyPathology | 27 | 44 | 61.36 | ||||||||

| CHR_Mouse_Kidney_1_AnyLesion | 27 | 44 | 61.36 | ||||||||

| CHR_Mouse_Kidney_2_PreneoplasticLesion | 6 | 10 | 60.00 | ||||||||

| CHR_Mouse_Kidney_3_NeoplasticLesion | 3 | 4 | 75.00 | ||||||||

| CHR_Mouse_LiverHypertrophy | 40 | 59 | 67.80 | ||||||||

| CHR_Mouse_LiverNecrosis | 27 | 38 | 71.05 | ||||||||

| CHR_Mouse_LiverProliferativeLesions | 51 | 86 | 59.30 | ||||||||

| CHR_Mouse_LiverTumors | 40 | 68 | 58.82 | ||||||||

| CHR_Mouse_Liver_1_AnyLesion | 78 | 121 | 64.46 | ||||||||

| CHR_Mouse_Liver_2_PreneoplasticLesion | 53 | 88 | 60.23 | ||||||||

| CHR_Mouse_Liver_3_NeoplasticLesion | 40 | 68 | 58.82 | ||||||||

| CHR_Rat_KidneyNephropathy | 19 | 35 | 54.29 | ||||||||

| CHR_Rat_KidneyProliferativeLesions | 16 | 29 | 55.17 | ||||||||

| CHR_Rat_Kidney_1_AnyLesion | 53 | 84 | 63.10 | ||||||||

| CHR_Rat_Kidney_2_PreneoplasticLesion | 15 | 28 | 53.57 | ||||||||

| CHR_Rat_Kidney_3_NeoplasticLesion | 3 | 6 | 50.00 | ||||||||

| CHR_Rat_LiverHypertrophy | 38 | 62 | 61.29 | ||||||||

| CHR_Rat_LiverNecrosis | 15 | 21 | 71.43 | ||||||||

| CHR_Rat_LiverProliferativeLesions | 40 | 59 | 67.80 | ||||||||

| CHR_Rat_LiverTumors | 15 | 21 | 71.43 | ||||||||

| CHR_Rat_Liver_1_AnyLesion | 77 | 124 | 62.10 | ||||||||

| CHR_Rat_Liver_2_PreneoplasticLesion | 38 | 56 | 67.86 | ||||||||

| CHR_Rat_Liver_3_NeoplasticLesion | 15 | 21 | 71.43 | ||||||||

| MGR_Rat_Kidney | 37 | 69 | 53.62 | ||||||||

| MGR_Rat_Liver | 62 | 102 | 60.78 | ||||||||

Concordance With Published Phase 1 Zebrafish Results

Analysis of our results for concordance with the zebrafish assay carried out at EPA on the phase 1 data (Padilla et al., 2012) identified endpoints with the highest concordance counts as mortality, yolk sac edema, and axis and jaw malformations (95, 59, 54, and 50, respectively, Supplementary Table 3B). Our zebrafish “any” developmental endpoint (including mortality) had the highest concordance count with the EPA screen, with 131 chemicals called positives in both screens. The present assay calls a similar number of chemicals positive for the phase 1 data set (60% in this study vs 62% in the EPA zebrafish data), with 75% positive concordance.

Concordance With In Vitro ToxCast Phase I Results

We compared our results with the existing EPA in vitro Phase I data. Across all chemicals, the in vitro data assays showing the highest level of concordance were ATG_PXRE_CIS, CLZD_CYP2B6_48, CLM_CellLoss_72hr, CLZD_CYP2B6_24, CLZD_CYP2B6_6, ATG_NRF2_ARE_CIS, CLZD_CYP3A4_48, BSK_Sag_Proliferation_down, BSK_hDFCGF_Proliferation_down, and ATG_PPARg_TRANS compared with “any” zebrafish endpoint hit. Toxcast assays with the highest percentage of concordance (> 90%) were NVS_TR_hDAT, NVS_TR_rVMAT2, CLM_Hepat_Apoptosis_48hrm, NVS_GPCR_h5HT6, NCGC_HEK293_Viability, and NVS_GPCR_hAdra2C. ATG_PXRE_CIS had the highest concordance count (14/18) with specific zebrafish endpoints (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Most Concordant ToxCast Assays for Each ZF Endpoint

| Zebrafish Endpoint | Concordance Count | ToxCast assay | Description | Assay Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MORT | 94 | ATG_PXRE_CIS | PXR response element transcription | Xenobiotic response genes |

| YSE_ | 53 | |||

| AXIS | 47 | |||

| EYE_ | 31 | |||

| SNOU | 43 | |||

| JAW_ | 42 | |||

| OTIC | 17 | |||

| PE__ | 46 | |||

| SOMI | 14 | |||

| PFIN | 22 | |||

| SWIM | 15 | |||

| TR__ | 30 | |||

| ANY_ZF_ENDPOINT | 130 | |||

| ANY_ZF_ENDPOINT_EXCEPT MORTALITY | 76 | |||

| BRAI | 21 | ATG_PXRE_CIS | PXR response element transcription | Xenobiotic response genes |

| CLM_CellLoss_72hr | Cell loss | Cell loss | ||

| CFIN | 20 | CLZD_CYP2B6_6 | Expression of Cyp2B6 | Drug metabolism |

| PIG_ | 13 | ATG_PXRE_CIS | PXR response element transcription | Xenobiotic response genes |

| CLM_CellLoss_72hr | Cell loss | Cell loss | ||

| CLZD_CYP2B6 | Expression of Cyp2B6 | Drug metabolism | ||

| CIRC | 8 | NVS_ADME_hCYP2C19 | Inhibition of Cyp2C19 | Drug metabolism |

| TRUN | 22 | CLZD_CYP2B6_24 | Expression of Cyp2B6 | Drug metabolism |

| NC__ | 5 | BSK_BE3C_uPAR_up | ↑ in uPAR expression | Collagen/plasmin formation and immune and inflammatory responses |

| BSK_hDFCGF_CollagenIII_down | ↓ in CollagenIII expression | |||

| BSK_hDFCGF_PAI1_down | ↓ in PAI1 expression | |||

| BSK_SAg_CD40_down | ↓ in CD40 expression | |||

| BSK_SM3C_Proliferation_down | ↓ in proliferation |

Notes. Eighteen specific endpoints and 2 aggregate (ANY_ZF_ENDPOINT and ANY_ZF_ENDPOINT_EXCEPT_MORALITY) were statistically evaluated for concordance using Cohen’s kappa test for all in vivo ToxCast assays. The highest concordance count for each endpoint-ToxCast in vitro assay is illustrated along with the assay target.

Cohen’s kappa concordance results indicate a statistically significant relationship (p values < .05) between intermediate (developmental endpoints) or terminal (mortality) in vivo endpoints and specific in vitro targets (Supplementary Table 3A). We found that 10 active ingredients of pesticides 3-iodo-2-propynyl-N-butylcarbamate, chlorothalonil, dicofol, emamectin benzoate, fluazinam, milbemectin, oryzalin, thiodicarb, triclosan, and triphenyltin hydroxide that caused an increase of cell loss at 1, 24, and 72h in the ToxCast assays (CLM_CellLoss_1hr/24hr/72hr) were significantly concordant with mortality in the developing zebrafish.

Analysis of the ToxCast NVS_ADME assays probing human or rat cytochrome P450 (CYP) inhibition revealed that 15 CYPs (human: 1A2, 2B6, 2C18, 2C19, 2C9, 3A5; rat: 2A1, 2A2, 2B1, 2C11, 2C13, 2C6, 2D2, 3A1, 3A2) had significant concordance with several zebrafish endpoints. Interestingly, for all except 2C19, there was no significant concordance with mortality. This suggested that the zebrafish system may be an effective sensor for bioactive chemicals causing sublethal developmental toxicity.

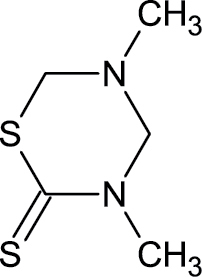

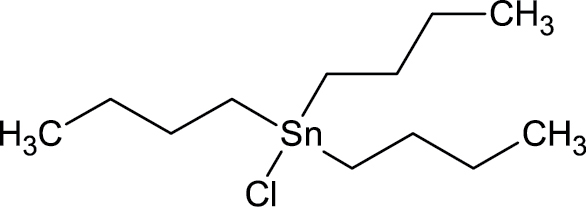

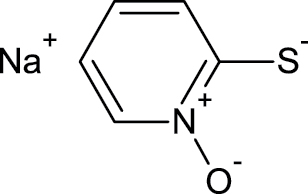

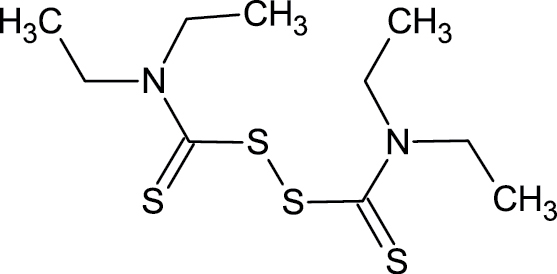

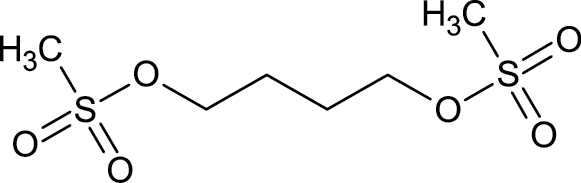

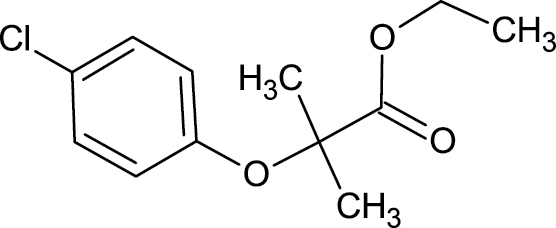

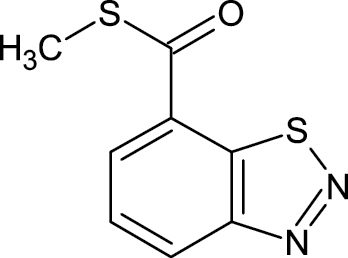

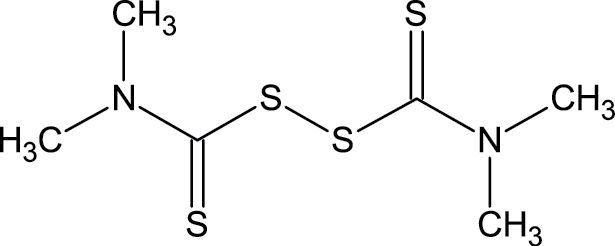

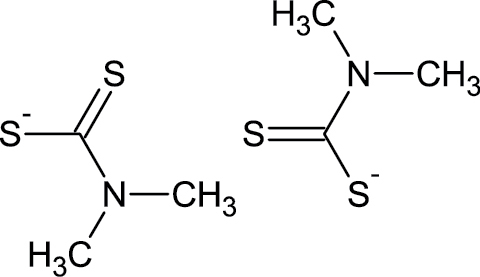

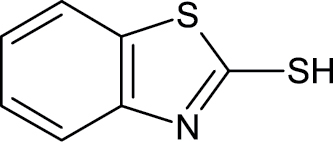

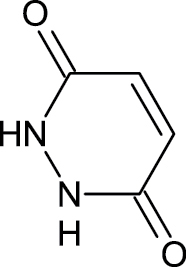

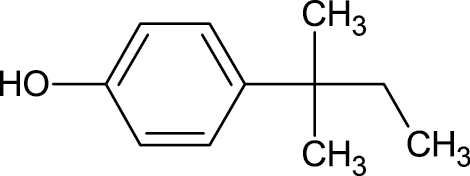

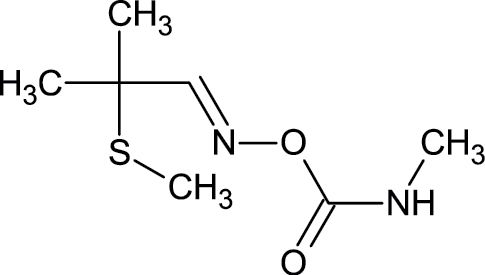

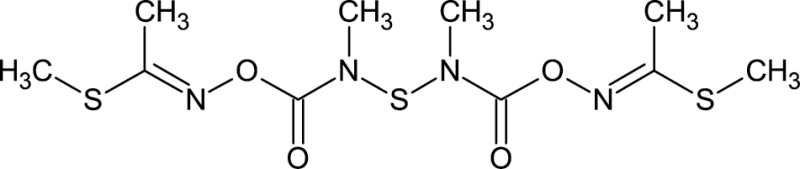

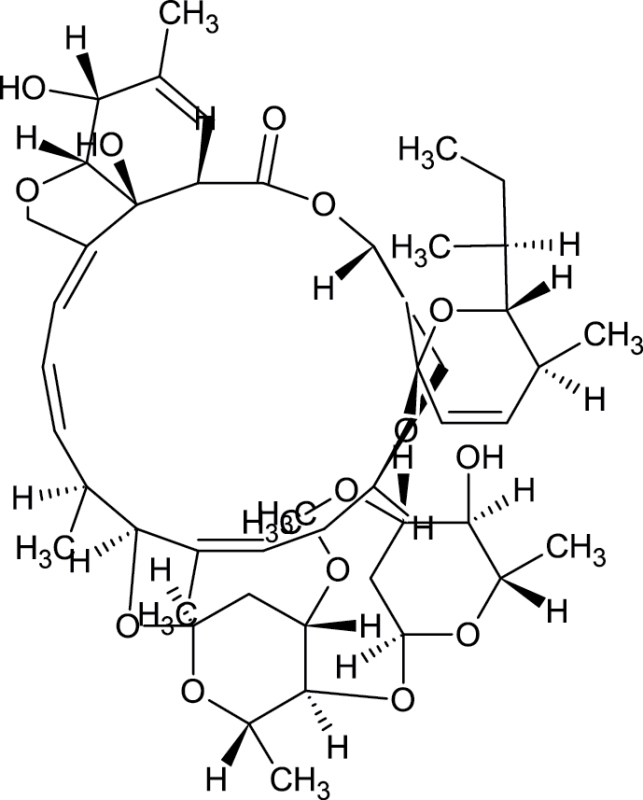

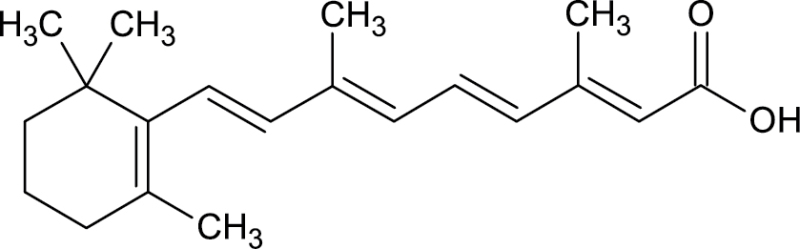

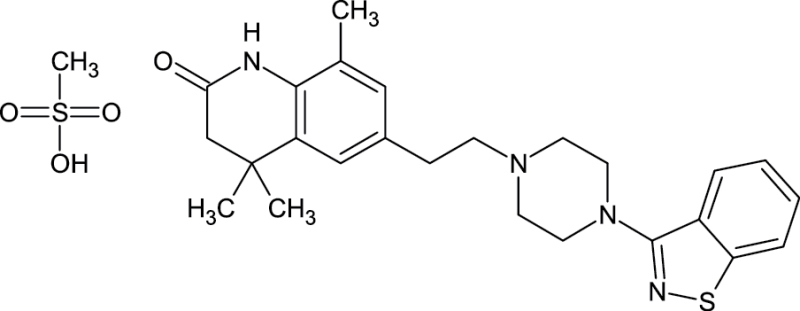

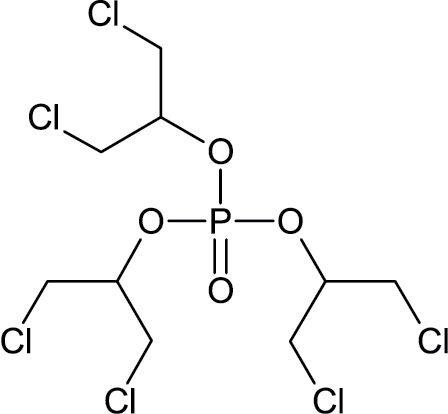

Specific Developmental Malformation Endpoint: Notochord Distortion and Lower Axial Bend

Defects in the notochord and lower axial bend are 2 malformations that occur only during development. Nineteen chemicals in the ToxCast chemical library induced these specific malformations (Table 3) and fell into 2 use categories: drugs (disulfiram, busulfan, clofibrate, 4-(2-methylbutan-2-yl) phenol, trans-retinoic acid, 6-{2-[4-(12-benzothiazol-3-yl) piperazin-1-yl]ethyl}-448-trimethyl-34-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-one methanesulfonate, Tris(13-dichloro-2-propyl)phosphate) or pesticides (dazomet, tributyltin chloride, sodium(2-pyridlthio)-N-oxide, acibenzolar-S-methyl, thiram, ziram, 2-mercaptobenzothiazole, maleic hydrazide, sodium dimethyldithiocarbamate, aldicarb, thiodicarb, abamectin).

TABLE 3.

Chemicals Affecting Notochords or Lower Axial Bend.

| Chemical Structure | Testsubstance_CASRN | Testsubstance_Chemicalname | Category Use |

|---|---|---|---|

|

533-74-4 | Dazomet | Algaecide, a bacteriostat, and a microbicide |

|

1461-22-9 | Tributyltin chloride | Biocide |

|

3811-73-2 | Sodium (2-pyridylthio)-N-oxide | Biocide |

|

97-77-8 | Disulfiram | Drug: alcoholism |

|

55-98-1 | Busulfan | Drug: cancer |

|

637-07-0 | Clofibrate | Drug: lipid-lowering agent |

|

135158-54-2 | Acibenzolar-S-methyl | Fungicide |

|

137-26-8 | Thiram | Fungicide |

|

137-30-4 | Ziram | Fungicide |

|

149-30-4 | 2-Mercaptobenzothiazole | Fungicides |

|

123-33-1 | Maleic hydrazide | Herbicide |

|

128-04-1 | Sodium dimethyldithiocarbamate | Herbicide |

|

80-46-6 | 4-(2-Methylbutan-2-yl)phenol | High production volume phenol |

|

116-06-3 | Aldicarb | Insecticide |

|

59669-26-0 | Thiodicarb | Insecticide |

|

71751-41-2 | Abamectin | insecticide |

|

302-79-4 | trans-Retinoic acid | Metabolite of vitamin A |

|

676116-04-4 | 6-{2-[4-(12-benzothiazol-3-yl)piperazin-1-yl]ethyl}-448-trimethyl- 34- dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-one methanesulfonate | N/A |

|

13674-87-8 | Tris(13-dichloro-2-propyl)phosphate | Triester organophosphate flame retardants |

Notes. Chemical structure, CAS, chemical name, and category use are illustrated for chemicals affecting notochord/lower axial bend.

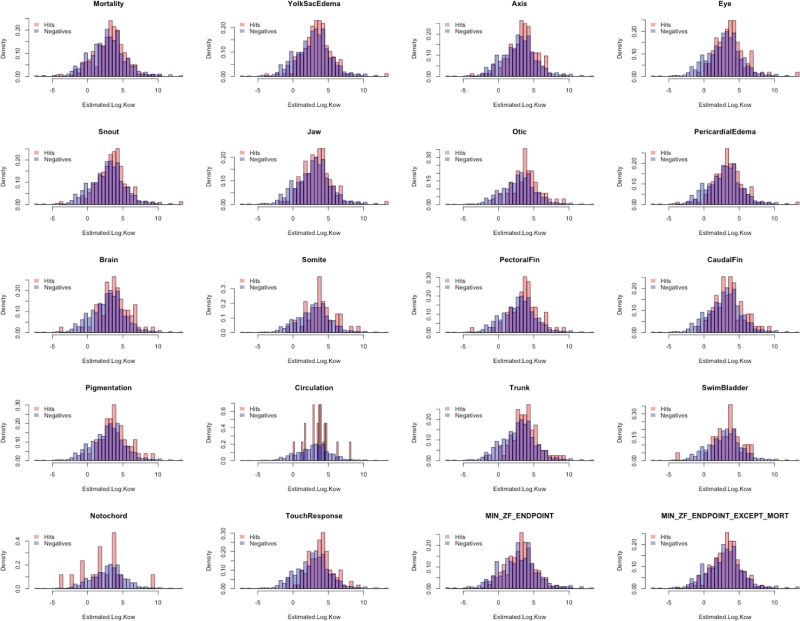

Association Between Zebrafish Endpoints and Common Bioavailability Predictors

We evaluated the association between zebrafish results and 2 widely accepted predictors of aquatic bioavailability: the Log K ow and the BCF, which is a critical factor for fish immersed in chemical solution (Gobas and Morrison, 2000; Landis et al., 2011). We found that neither Log K ow nor BCF was entirely predictive of response or the potency (LEL). However, for some zebrafish endpoints, the mean Log K ow and BCF of active chemicals were slightly higher (Student’s t test, p < .05) than inactives (Fig. 7), although the mean differences were minimal. The generally weak associations between these bioavailability predictors and our results may reflect the dechorionation step (removal of acellular barrier) or nonapplicability of these predictors for the broad chemical set tested.

FIG. 7.

Histogram of Log K ow by biological activity and Log K ow. Separate histograms are plotted for chemicals classified as “Hits” (pink) or “Negatives” (blue), with Log K ow along the horizontal axis. The purple shading represents overlap between the 2 distributions.

Ability of Zebrafish Developmental Endpoints to Detect Neurotoxicants

To determine the sensitivity of the embryonic zebrafish assay to detect known zebrafish neurotoxicants in the ToxCast data set, a list of 18 chemicals identified in the literature as zebrafish neurotoxicants covering several modes of action was compiled (Table 4). This developmental assay system was capable of detecting 78% (14/18) of neurotoxicants identified in the literature. The 4 chemicals that were not detected in this system were chlorpyrifos (nonoxon), atrazine, valproic acid, and acrylamide.

TABLE 4.

Zebrafish Neurotoxicants Identified by Literature

| Testsubstance_CASRN | Testsubstance_Chemicalname | Developmental Toxicity Detection Status | Reference on Zebrafish Neurotoxicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 79-06-1 | Acrylamide | − | Parng et al. (2007) |

| 1912-24-9 | Atrazine | − | Ton et al. (2006) |

| 82657-04-3 | Bifenthrin | + | DeMicco et al. (2010) |

| 80-05-7 | Bisphenol A | + | Saili et al. (2012) |

| 58-08-2 | Caffeine | + | Guo (2009) |

| 2921-88-2 | Chlorpyrifos | − | Selderslaghs et al. (2010) |

| 5598-15-2 | Chlorpyrifos oxon | + | Selderslaghs et al. (2010) |

| 2392-39-4 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate | + | Rihel et al. (2010) |

| 60-57-1 | Dieldrin | + | Ton et al. (2006) |

| 115-29-7 | Endosulfan | + | Stanley et al. (2009) |

| 120068-37-3 | Fipronil | + | Stehr et al. (2006) |

| 52-86-8 | Haloperidol | + | Rihel et al. (2010) |

| 72-43-5 | Methoxychlor | + | D’Amico et al. (2008) |

| 54-11-5 | Nicotine | + | Rihel et al. (2010) |

| 1763-23-1 | Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid | + | Huang et al. (2010) |

| 709-98-8 | Propanil | + | D’Amico et al. (2008) |

| 83-79-4 | Rotenone | + | Bretaud et al. (2004) |

| 99-66-1 | Valproic acid | − | Cowden et al. (2012) |

Notes. Chemical CAS, name, and literature citation.

DISCUSSION

We have presented a high-throughput design for screening a comprehensive battery of zebrafish developmental morphology and neurotoxicity endpoints in vivo. We demonstrated that the embryonic zebrafish is an outstanding biological sensor to identify bioactive chemicals. It is an efficient and flexible experimental platform that can be used to assign meaningful hazard ranks to the vast diversity of potential and current consumer and pharmaceutical chemicals. Most importantly, as more chemicals are screened, the expanding reference database can be ever more deeply mined for cellular targets and for comparing other in vivo, in vitro, and in silico data. We demonstrated that reliance on mortality as the key determinant of chemical hazard resulted in a high rate of false negatives, and only by screening a wider variety of endpoints can this be rectified.

Although the developmental zebrafish is perhaps the best vertebrate model for such screens, it is only as good as the experimental design. The global toxic response patterns to the chemicals pointed to high correlation among endpoints. However, there were several chemicals that caused very specific developmental responses. For instance, exposure to certain pesticides (thiram, ziram, and sodium dimethyldithiocarbamate) known to disrupt normal notochord development (Teraoka et al., 2006; Tilton et al., 2006; Tilton and Tanguay, 2008) is not a commonly reported toxicity endpoint. In our screen, a large portion of the embryos exposed to the 19 chemicals that affected notochord development or somitogenesis did not exhibit other effects.

Comparison with previously published EPA zebrafish screening results (Padilla et al., 2012) showed that for Phase I chemicals, 75% of the chemicals called hits in the present assay were hits in both zebrafish assays. Discord in the results between this multidimensional screen and previously published EPA zebrafish screening results is likely due to differences in study design and goals. Several major attributes of our experimental approach include (1) removal of the embryo chorion prior to exposure, (2) use of static chemical exposures requiring far less embryo manipulation, (3) rearing embryos at the ideal 28°C, (4) expanded evaluation to 22 endpoints versus 6 in the EPA study, (5) dose-concentration range tested, and (6) number of replicates. We enzymatically removed the chorion from all embryos to remove a potential barrier to test chemicals. The use of a static exposure schedule, where the embryos remain essentially undisturbed following the chemical dosing until the 120 hpf evaluation, simulates an acute developmental exposure and ensuing metabolic removal and chemical lability. There are valid rationales for using either static or chronic renewal exposures; however, to maximize throughput and minimize handling damage, we chose static bath exposure. Developing zebrafish embryos are sensitive to temperature (Kimmel et al., 1995) with a well-documented developmental optimum at 28°C (Kimmel et al., 1995). We screened and entered binary scores for 22 endpoints into the ZAAP. Our goal was to maximize throughput while collecting as much information as practical in a single pass. The EPA zebrafish screen scored some malformations in binary fashion, whereas others were scored by relative degree (0 = present, 4 = severe), then an aggregated malformation index was computed (Padilla et al., 2012). Additionally, we exposed the developing embryos to concentrations ranging from 6.4nM to 64μM (10-fold serial dilution), whereas the EPA study used 1nM to 80μM with 5-fold serial dilution. A key difference between the experimental designs is the number of replicate animals. In order to reduce false positives and sensitivity, we utilized 32 embryos per concentration, whereas the EPA study used far fewer replicates. In Padilla et al. (2012), toxicity incidence and potency were found to be correlated with hydrophobicity (logP) across the phase 1 chemicals. Based on our zebrafish assay run across all 1060 unique phase 1 and phase 2 chemicals, we did not find this same correlation for the developmental zebrafish endpoints. This could be due to the differences in the experimental approach or the characteristics of the expanded, more diverse chemical set tested here. The combination of the number of dechorionated embryos exposed statically to chemicals and the scoring methodology undoubtedly affected the results and the concordance between the 2 zebrafish studies.

Our Phase I concordance analysis sought to qualify the complementarity of the developmental zebrafish outcomes reported here with in vitro outcomes in xenobiotic metabolism and CYP inhibition assays, and developmental rat or rabbit maternal and pregnancy studies. The strong correlation between the embryonic zebrafish and developmental rat/rabbit studies could be readily anticipated as zebrafish is widely documented to rival or exceed the utility of rodents for the modeling of a growing list of human diseases (Lieschke and Currie, 2007; Santoriello and Zon, 2012; Scholz, 2013). The concordance of xenobiotic-related in vitro assays and morphologically abnormal embryonic zebrafish was also somewhat anticipated as zebrafish have a total of 94 CYP genes found in mammals, 32 of which are direct orthologs of human CYPs (Goldstone et al., 2010). There may be a causal relationship between the CYP inhibition (as inferred from chemicals perturbing in vitro CYP assays) and developmental endpoints in zebrafish. This high concordance between the developmental zebrafish endpoints and in vitro cellular metabolism suggested that the embryonic zebrafish was an effective biosensor for developmental toxicants impacting xenobiotic metabolism.

The chemicals and endpoints lacking concordance with ToxCast Phase I results may indicate toxicity pathways or chemical classes requiring more attention in future phases. Instances where discordance is observed between the developmental zebrafish and mammalian responses to the same compound class can only serve to refine our estimates of ultimate hazard prediction with zebrafish. By assessing a comprehensive developmental endpoint set in the embryonic zebrafish, other classes of hazard may be detected. For example, we demonstrated solid power (78%) to flag neurotoxicants across these endpoints. Notably, only the oxon form of chlorpyrifos was positive (across several endpoints) in this assay, highlighting the importance of considering metabolic capacity. Although subsets of the developmental endpoints measured here are correlated, these collective data are highly valuable when the primary goal is to detect hazardous chemicals. The relationships between endpoints can be used to infer mechanisms and underlying toxicological pathways.

When utilizing multiple measures, the entire system serves as a robust biological sensor providing foresight into chemicals that have the potential to cause adverse effects. The power and value of ToxCast can be enhanced by integrating the developing zebrafish into the existing in vitro high-throughput assays to identify potentially hazardous chemicals. To accomplish this, the zebrafish would serve as the “tier 1” of the hazard identification schema where all chemicals are assessed and all those with potential to cause adverse effects will be further screened in the battery of in vitro tests and evaluated in the predictive models already developed. Having a whole-organism system as the first tier provides the ability to detect endpoints that may be missed in a screen using in vitro assays, such as metabolism and pathway sensors. The sensitivity to detect hazardous chemicals will greatly improve with integration of this powerful model and the current mechanistic-focused in vitro assays. This data set is a powerful resource that can be used in conjunction with data sets from other biological platforms. Together, we will be positioned to accelerate chemical testing into the 21st century and identify potential hazardous chemicals prior to their release in the environment.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at http://toxsci.oxfordjournals.org/.

FUNDING

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) (RC4 ES019764 P30, P30 ES000210); Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) STAR Grant (R835168 to R.L.T.).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would also like to acknowledge the EPA for providing the ToxCast test chemicals for these studies. The authors would also like to thank members of the Tanguay laboratory and the Sinnhuber Aquatic Research Laboratory for assistance with fish husbandry and chemical screening.

REFERENCES

- Bretaud S., Lee S., Guo S. (2004). Sensitivity of zebrafish to environmental toxins implicated in Parkinson’s disease. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 26, 857–864.10.1016/j.ntt.2004.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 20, 37–46.10.1177/001316446002000104 [Google Scholar]

- Cowden J., Padnos B., Hunter D., MacPhail R., Jensen K., Padilla S. (2012). Developmental exposure to valproate and ethanol alters locomotor activity and retino-tectal projection area in zebrafish embryos. Reprod. Toxicol. 33, 165–173.10.1016/j.reprotox.2011.11.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico L. J., Li C. Q., Seng W. L., McGrath P. (2008). Developmental neurotoxicity assessment in zebrafish: A survey of 200 environmental toxicants. In Society of Toxicology; March 2008; Seattle, WA. [Google Scholar]

- DeMicco A., Cooper K. R., Richardson J. R., White L. A. (2010). Developmental neurotoxicity of pyrethroid insecticides in zebrafish embryos. Toxicol. Sci. 113, 177–186.10.1093/toxsci/kfp258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobas F. A. P. C., Morrison H. A. (2000). Bioconcentration and biomagnification in the aquatic environment. In: Boethling R.S., Mackay D., eds, Handbook of Property Estimation Methods for Chemicals: Environmental and Health Sciences, 1st ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 189–231 [Google Scholar]

- Goldstone J. V., McArthur A. G., Kubota A., Zanette J., Parente T., Jönsson M. E., Nelson D. R., Stegeman J. J. (2010). Identification and developmental expression of the full complement of Cytochrome P450 genes in Zebrafish. BMC Genomics 11, 643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S. (2009). Using zebrafish to assess the impact of drugs on neural development and function. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 4, 715–726.10.1517/17460440902988464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe K., Clark M. D., Torroja C. F., Torrance J., Berthelot C., Muffato M., Collins J. E., Humphray S., McLaren K., Matthews L., et al. (2013). The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature 496, 498–503.10.1038/nature12111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H., Huang C., Wang L., Ye X., Bai C., Simonich M. T., Tanguay R. L., Dong Q. (2010). Toxicity, uptake kinetics and behavior assessment in zebrafish embryos following exposure to perfluorooctanesulphonicacid (PFOS). Aquat. Toxicol. 98, 139–147.10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judson R. S., Houck K. A., Kavlock R. J., Knudsen T. B., Martin M. T., Mortensen H. M., Reif D. M., Rotroff D. M., Shah I., Richard A. M., et al. (2010). In vitro screening of environmental chemicals for targeted testing prioritization: The ToxCast project. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 485–492.10.1289/ehp.0901392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel C. B., Ballard W. W., Kimmel S. R., Ullmann B., Schilling T. F. (1995). Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 203, 253–310.10.1002/aja.1002030302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokel D., Bryan J., Laggner C., White R., Cheung C. Y., Mateus R., Healey D., Kim S., Werdich A. A., Haggarty S. J., et al. (2010). Rapid behavior-based identification of neuroactive small molecules in the zebrafish. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 231–237.10.1038/nchembio.307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis W. G., Sofield R. M., Yu M. H. (2011). Introduction to Environmental Toxicology: Molecular Structures to Ecological Landscapes, 4th ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- Lieschke G. J., Currie P. D. (2007). Animal models of human disease: Zebrafish swim into view. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 353–367.10.1038/nrg2091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandrell D., Truong L., Jephson C., Sarker M. R., Moore A., Lang C., Simonich M. T., Tanguay R. L. (2012). Automated zebrafish chorion removal and single embryo placement: Optimizing throughput of zebrafish developmental toxicity screens. J. Lab. Autom. 17, 66–74.10.1177/2211068211432197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla S., Corum D., Padnos B., Hunter D. L., Beam A., Houck K. A., Sipes N., Kleinstreuer N., Knudsen T., Dix D. J., et al. (2012). Zebrafish developmental screening of the ToxCast™ Phase I chemical library. Reprod. Toxicol. 33, 174–187.10.1016/j.reprotox.2011.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Martin C., Chang T. Y., Koo B. K., Gilleland C. L., Wasserman S. C., Yanik M. F. (2010). High-throughput in vivo vertebrate screening. Nat. Methods 7, 634–636.10.1038/nmeth.1481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parng C., Roy N. M., Ton C., Lin Y., McGrath P. (2007). Neurotoxicity assessment using zebrafish. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 55, 103–112.10.1016/j.vascn.2006.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rihel J., Prober D. A., Arvanites A., Lam K., Zimmerman S., Jang S., Haggarty S. J., Kokel D., Rubin L. L., Peterson R. T., et al. (2010). Zebrafish behavioral profiling links drugs to biological targets and rest/wake regulation. Science 327, 348–351.10.1126/science.1183090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saili K. S., Corvi M. M., Weber D. N., Patel A. U., Das S. R., Przybyla J., Anderson K. A., Tanguay R. L. (2012). Neurodevelopmental low-dose bisphenol A exposure leads to early life-stage hyperactivity and learning deficits in adult zebrafish. Toxicology 291, 83–92.10.1016/j.tox.2011.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoriello C., Zon L. I. (2012). Hooked! Modeling human disease in zebrafish. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 2337–2343.10.1172/JCI60434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz S. (2013). Zebrafish embryos as an alternative model for screening of drug-induced organ toxicity. Arch. Toxicol. 87, 767–769.10.1007/s00204-013-1044-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selderslaghs I. W., Hooyberghs J., De Coen W., Witters H. E. (2010). Locomotor activity in zebrafish embryos: A new method to assess developmental neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 32, 460–471.10.1016/j.ntt.2010.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley K. A., Curtis L. R., Simonich S. L., Tanguay R. L. (2009). Endosulfan I and endosulfan sulfate disrupts zebrafish embryonic development. Aquat. Toxicol. 95, 355–361.10.1016/j.aquatox.2009.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehr C. M., Linbo T. L., Incardona J. P., Scholz N. L. (2006). The developmental neurotoxicity of fipronil: Notochord degeneration and locomotor defects in zebrafish embryos and larvae. Toxicol. Sci. 92, 270–278.10.1093/toxsci/kfj185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teraoka H., Urakawa S., Nanba S., Nagai Y., Dong W., Imagawa T., Tanguay R. L., Svoboda K., Handley-Goldstone H. M., Stegeman J. J., et al. (2006). Muscular contractions in the zebrafish embryo are necessary to reveal thiuram-induced notochord distortions. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 212, 24–34.10.1016/j.taap.2005.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilton F., La Du J. K., Vue M., Alzarban N., Tanguay R. L. (2006). Dithiocarbamates have a common toxic effect on zebrafish body axis formation. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 216, 55–68.10.1016/j.taap.2006.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilton F., Tanguay R. L. (2008). Exposure to sodium metam during zebrafish somitogenesis results in early transcriptional indicators of the ensuing neuronal and muscular dysfunction. Toxicol. Sci. 106, 103–112.10.1093/toxsci/kfn145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ton C., Lin Y., Willett C. (2006). Zebrafish as a model for developmental neurotoxicity testing. Birth Defects Res. A. Clin. Mol. Teratol. 76, 553–567.10.1002/bdra.20281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong L., Harper S. L., Tanguay R. L. (2011). Evaluation of embryotoxicity using the zebrafish model. Methods Mol. Biol. 691, 271–279.10.1007/978-1-60761-849-2_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong L., Saili K. S., Miller J. M., Hutchison J. E., Tanguay R. L. (2012). Persistent adult zebrafish behavioral deficits results from acute embryonic exposure to gold nanoparticles. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 155, 269–274.10.1016/j.cbpc.2011.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. (2000). The Zebrafish Book. A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio rerio), 4th ed University of Oregon, Eugene, OR [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.