Abstract

Dihydroartemisinin (DHA), an antimalarial drug, has previously unrecognized anticancer activity, and is in clinical trials as a new anticancer agent for skin, lung, colon and breast cancer treatment. However, the anticancer mechanism is not well understood. Here, we show that DHA inhibited proliferation and induced apoptosis in rhabdomyosarcoma (Rh30 and RD) cells, and concurrently inhibited the signaling pathways mediated by the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a central controller for cell proliferation and survival, at concentrations (<3 μM) that are pharmacologically achievable. Of interest, in contrast to the effects of conventional mTOR inhibitors (rapalogs), DHA potently inhibited mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation of p70 S6 kinase 1 and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 but did not obviously affect mTORC2-mediated phosphorylation of Akt. The results suggest that DHA may represent a novel class of mTORC1 inhibitor and may execute its anticancer activity primarily by blocking mTORC1-mediated signaling pathways in the tumor cells.

Introduction

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a soft tissue (usually muscle) sarcoma, which occurs often in the head, neck, bladder, vagina, arms, legs and trunk of children (1,2). About 80% of patients are <15 years old (3). Around 70% of lesions happen in the head and neck, extremities and genitourinary tract (1). Histologically, RMS manifests in two major types, embryonal RMS and alveolar (aRMS) (1). Morphologically, embryonic type resembles to the embryonic muscle cell precursor, whereas alveolar type has clusters of round cells similar to lung alveoli (1). Treatments of RMS are routinely made of multimodality approach of surgery, radiation and chemotherapy (1–3). Fortunately, due to the improvement in treatment strategies during the last 30 years, overall survival rate of RMS has increased to ~80% (1). Current standard chemotherapy for RMS is the combination of vincristine, actinomycin D and cyclophosphamide (1). However, in general, aRMS has worse prognosis with <50% of 5-year survival rate, and when metastasized, <10% of patients survive (1). This figure has not been improved for decades (1). A unique characteristic of aRMS is the presence of chromosomal translocation like leukemic cells, resulting fusion gene of the paired box and fork head transcription factors, PAX3-FKHR, in 70% of aRMS cases (4,5). Therefore, it is imperative to develop new tools to combat RMS.

Dihydroartemisinin (DHA), a semisynthetic antimalarial compound, is a derivative of artemisinin originally isolated from the plant, Artemisia annua (annual wormwood) by Chinese scientists in 1972 (6). DHA is also the active metabolite of all artemisinin compounds (artemisinin, artesunate, artemether, etc.) and ~5 times more potent than artemisinin against malaria, Plasmodium falciparum (6–8). Despite wide use of artemisinin in treatment of malaria, the mechanism of its action in parasites is not clear (6).

Increasing evidence reveals that DHA has previously unrecognized anticancer activity (6). Sun et al. (9) first reported the cytotoxicity of artemisinin in murine leukemia cell line P388, human hepatoma cell line SMMC-7721 and human gastric cancer cell line SGC-7901. Very quickly, Moore et al. (10) found that oral administration of DHA and ferrous sulfate inhibited the growth of implanted fibrosarcoma in rats. A water-soluble artemisinin derivative, artesunate, has been completed in early clinical trials for melanoma and lung cancer (11,12). One patient with stage IV uveal melanoma (a median survival ranges 2–5 months) remained alive after 47 months of diagnosis with a stabilization of the disease and regressions of splenic and lung metastases, in combination with dacarbazine (11). Also, artesunate combined with vinorelbine and cisplatin slowed down the disease progression and increased the short-term survival rate in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer but did not show extra side effects (12). In addition, two phase I clinical trials of artesunate for colorectal (http://www.controlled-trials.com/ISRCTN05203252) and metastatic breast cancer (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00764036) are undertaking in the UK and Germany, respectively. However, to our knowledge, the anticancer activity of DHA in RMS is largely unknown.

To facilitate repurposing DHA for cancer therapy, intensive studies have recently been carried out to understand its anticancer mechanisms. Current data have implicated that the molecular mechanisms by which DHA functions as an anticancer agent are varied, depending on the cancer cell type. For example, DHA inhibits growth and induces apoptosis in rat glioma (C6) cells by reducing hypoxia-induced expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α) and its target gene protein, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (13). DHA induces apoptosis in human promyelocytic leukemia (HL-60) and colorectal carcinoma (HCT116) cells by downregulating expression of c-myc (14), and in human leukemia cells by downregulating Mcl-1 expression and inhibiting extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1/2 (Erk1/2) activity (15). DHA reduces cell viability in pancreatic cancer cells by inhibiting nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) activity, resulting in downregulation of NF-κB-targeted gene products, such as VEGF, c-myc and cyclin D1 (16,17). DHA inhibits growth in lung cancer cells by suppressing expression of VEGF receptor KDR/flk-1 (18). DHA induces G2/M arrest by upregulating p21 and downregulating cyclin B and CDC25C expression and induces apoptosis by activation of caspases 3/9 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells (19). DHA inhibits ovarian cancer cell proliferation, adhesion, migration and invasion, which is consistent with decreased expression of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) phosphorylation and matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) expression (20). Although it is plausible that DHA may target each of these individual molecules in a cell-type- and cell-environment-dependent manner, it is more logical to postulate that DHA directly affects a few major targets, which indirectly impact all of the other factors.

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a serine/threonine kinase, lies downstream of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-1R)-phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase (PI3K) (21). Cumulative evidence has demonstrated that mTOR is a master kinase, regulating cell proliferation and survival (21). Dysregulation of mTOR pathway has been frequently observed in a variety of human tumors, and these tumor cells have shown higher susceptibility to inhibitors of mTOR than normal cells (21,22). Thus, mTOR has emerged as an important target for the development of anticancer agents. mTOR functions at least as two complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2 (21). These two complexes consist of unique mTOR-interacting proteins that determine their substrate specificity. mTORC1 is composed of mTOR, mLST8 (also termed G-protein β-subunit-like protein, GβL, a yeast homolog of LST8), raptor (regulatory-associated protein of mTOR), PRAS40 (proline-rich Akt substrate 40kDa) and DEPTOR (23–29), whereas mTORC2 consists of mTOR, mLST8, rictor (rapamycin insensitive companion of mTOR), mSin1 (mammalian stress-activated protein kinase-interacting protein 1), protor (protein observed with rictor, also named PRR5, proline-rich protein 5) and DEPTOR (26,29–38). mTORC1 regulates phosphorylation of p70 S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) (23–29), whereas mTORC2 phosphorylates Akt (S473), serum and glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1 (SGK1, S422), protein kinase C α (PKCα, S657), focal adhesion proteins (FAK and paxillin), and signals to small guanosine triphosphatases (RhoA, Rac1 and Cdc42) (30–40). Many functions of mTORC1 are sensitive to rapamycin, a conventional allosteric mTOR inhibitor (21). However, the action of rapamycin on mTORC2-mediated Akt depends on the concentration and duration of rapamycin treatment (41). Acute rapamycin treatment decreases phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1, which results in insulin receptor substrate-1 accumulation, thereby activating PI3K/Akt (42–44). However, higher concentrations and/or longer exposure of rapamycin can inhibit Akt by disrupting mTORC2 complex formation (41). Although the cellular functions of the mTOR complexes remain to be determined, current data indicate that mTOR is at least involved in the regulation of synthesis and/or activities of cyclins D1/A (45–47), cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) (48), CDK inhibitors (p21Cip1 and p27Kip1) (49–51), c-myc (52), HIF-1α (53), VEGF (54), Erk1/2 (55), FAK (39), MMP-2 (56) and NF-κB (57). Therefore, mTOR has been implicated as a central regulator of cell growth, proliferation, survival, motility and angiogenesis. Of particular interest is that among the proteins regulated by mTOR, a number of them, such as HIF-1α, VEGF, cyclin D1, c-myc, NF-κB, Erk1/2, FAK and MMP-2, are also targeted by DHA (13–20). This prompted us to study whether DHA inhibits mTOR signaling.

Here, for the first time, we show that DHA inhibited proliferation and induced apoptosis in cells derived from RMS (Rh30 and RD). Concurrently, DHA, at pharmacological concentrations (<3 μM), potently suppressed mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1 in the tumor cells. Unlike rapamycin, DHA did not obviously affect mTORC2-mediated phosphorylation of Akt. Our results suggest that DHA may represent a new class of mTORC1 inhibitor and execute its anticancer activity by primarily targeting mTORC1 signaling.

Materials and methods

Materials

Artemisinins, including artemisinin, DHA, artesunate and artemether (all purity >98% by high-performance liquid chromatography) were purchased from TCI America (Portland, OR), dissolved in 100% ethanol to prepare a stock solution (10mM), aliquoted and stored at −20°C. IGF-1 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) was rehydrated in 0.1M acetic acid to prepare a stock solution (10 μg/ml), aliquoted and stored at −80°C. RPMI 1640 and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium were obtained from Mediatech (Herndon, VA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was from Atlanta Biologicals (Lawrenceville, GA), whereas 0.05% trypsin–ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid was from Mediatech. Enhanced chemiluminescence solution was from Perkin-Elmer Life Science (Boston, MA). CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay kit was from Promega (Madison, WI). Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit I was purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). The following antibodies were used: c-myc, cyclin A, cyclin B1, cyclin D1, cyclin E, p21Cip1, p27Kip1, Cdc25A, Cdc25B, Cdc25C, CDK1 (Cdc2), CDK2, CDK4, retinoblastoma (Rb), p-Rb (S807/811), poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), BAD, BAX, BAK, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, survivin, PARP, FRAP (mTOR), Akt, S6K1, S6 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), phospho-mTOR (S2448), phospho-S6K1 (T389), phospho-S6 (S235/236), 4E-BP1, phospho-4E-BP1 (T70), phospho-Akt (S473) (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA), β-tubulin (Sigma, St Louis, MO), goat anti-mouse IgG–horseradish peroxidase and goat anti-rabbit IgG–horseradish peroxidase (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Cell lines and culture

Human RMS (Rh30, p53 mutant, Arg273→Cys; RD, p53 mutant, Arg248→Trp) and Ewing sarcoma (Rh1, p53 mutant, Tyr220→Cys) cells (58,59) were generously provided by Dr Peter J.Houghton (Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH) and were grown in antibiotic-free RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C and 5% CO2. Mouse myoblasts (C2C12), human leukemia (K562), lymphoma (U937), prostate carcinoma (PC-3) and cervical carcinoma (HeLa) cells were from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). C2C12 and HeLa were grown in antibiotic-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% FBS, whereas K562, U937 and PC-3 were grown in antibiotic-free RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, at 37°C and 5% CO2. For experiments where cells were deprived of serum, cell monolayers were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated in the serum-free RPMI 1640.

Cell morphological analysis and cell proliferation assay

Rh30 and RD cells were seeded in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS in 6-well plates at a density of 2×104 cells/well and grown overnight at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Next day, artemisinin, DHA, artesunate or artemether (0–30 μM) was added. After incubation for 6 days, images were taken with an Olympus inverted phase-contrast microscope equipped with the Quick Imaging system. Cells were then trypsinized and enumerated using a Z1 Coulter Counter (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA).

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was evaluated using CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay kit (Promega) containing MTS [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt] and phenazine methosulfate. Briefly, cells suspended in the growth medium were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 1×104 cells/well (in triplicates) and grown overnight at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Next day, artemisinin, DHA, artesunate or artemether (0–30 μM) was added. After incubation for 48h, each well was added 20 μl of one solution reagent and incubated for 1h. Cell viability was determined by measuring the OD at 490nm using a Wallac 1420 Multilabel Counter (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Wellesley, MA).

Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle analysis was performed, as described previously (60). Briefly, Rh30 or RD cells were seeded in 60mm dishes at a density of 2×105 cells/dish in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and grown overnight at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Cells were then treated with DHA at 0–30 μM for 36 h or at 10 μM for 0–72h. Subsequently, the cells were briefly washed with PBS and trypsinized. Cell suspensions were centrifuged at 1000 r.p.m. for 5min, and pellets were fixed and stained with the Cellular DNA Flow Cytometric Analysis Kit (Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, IN). Percentages of cells within each of the cell cycle compartments (G0/G1, S, or G2/M) were determined using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and ModFit LT analyzing software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME). Cells treated with vehicle alone (100% ethanol) were used as a control.

Apoptosis assay

Rh30 or RD cells were seeded in 60 mm dishes at a density of 2×105 cells/dish in the growth medium and grown overnight at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Cells were treated with DHA (0–30 μM) for 72h, followed by apoptosis assay using the Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), as described previously (60). Flow cytometry was performed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Cells treated with vehicle alone (100% ethanol) were used as a control.

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed as described previously (61). Briefly, following treatment, cells were washed with cold PBS. On ice, cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, containing 50mM Tris, pH 7.2; 150mM NaCl; 1% sodium deoxycholate; 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate; 1% Triton-X 100; 10mM NaF; 1mM Na3VO4; protease inhibitor cocktail (1:1000, Sigma). Lysates were sonicated for 10 s and centrifuged at 14 000 r.p.m. for 10min at 4°C. Protein concentration was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay with bovine serum albumin as standard (Pierce). Equivalent amounts of protein were separated on 6–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were incubated with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 5% non-fat dry milk to block non-specific binding and were incubated with primary antibodies, then with appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by using Renaissance chemiluminescence reagent (Perkin-Elmer Life Science).

Analysis of 4E-BP1-eIF4E binding

A functional assay of 4E-BP1 was performed, as described previously (62). Briefly, Rh30 cells (3×106 cells/100 mm dish) were seeded and cultured overnight. Cells were then treated with DHA (0–10 μM) for 24h or with rapamycin (100ng/ml) for 2h. The cells were scraped into 1ml of ice-cold lysis buffer [50mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150mM KCl, 1mM dithiothreitol, 1mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1mM ethyleneglycol-bis (aminoethylether)-tetraacetic acid, 50mM β-glycerophosphate, 10mM sodium pyrophosphate, 50mM NaF, 1mM Na3VO4, 50 μM okadaic acid, 1mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and protease cocktail inhibitor (1:1000, Sigma)]. Lysis was accomplished by three freeze-thaw cycles and sonication. To pull down eIF4E, 30 μl of 7-methyl-GTP Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) was added to the lysates and incubated overnight on a rotator at 4°C. The beads were pelleted by centrifugation and washed once with the lysis buffer and three times with PBS, followed by western blotting for 4E-BP1 and eIF4E, as described above.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean values ± standard error. The data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by post hoc Dunnett’s t-test for multiple comparisons. A level of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

DHA inhibits proliferation in RMS cells

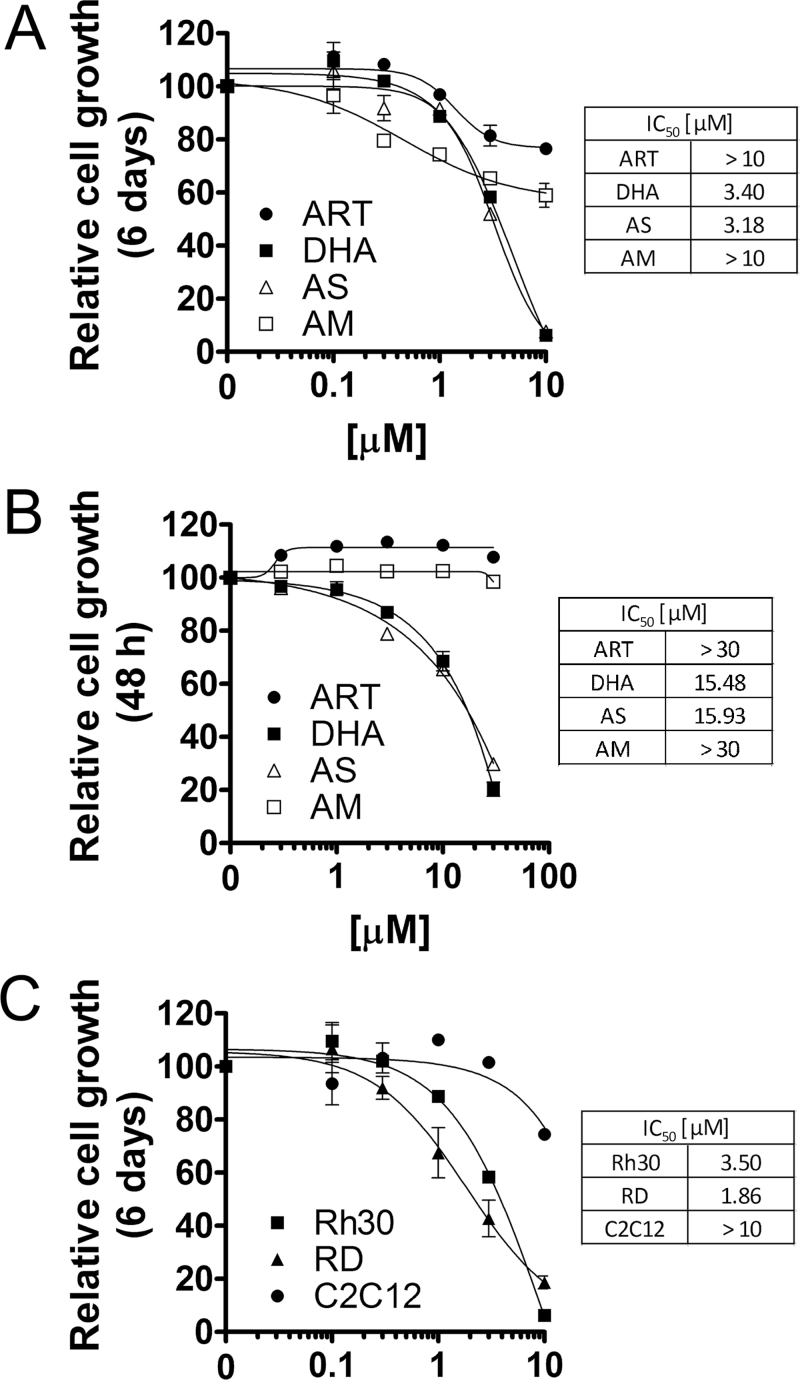

Artemisinins, including artemisinin, DHA, artesunate and artemether, as antimalarial agents, have been extensively studied (6,7). Pharmacokinetic studies have demonstrated that the maximum plasma concentrations of artemisinin, DHA, artesunate and artemether range from 2 to 30 μM, when given to Sprague–Dawley rats at 10mg/kg body weight, by intravenous or intramuscular injection, or by oral gavage (8). To determine which artemisinin compound is most potent as an anticancer agent, at the very beginning, RMS (Rh30) cells were treated with artemisinin, DHA, artesunate and artemether for 6 days at concentrations of 0–10 μM that are pharmacologically relevant (8). We found that all compounds inhibited cell proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1A). Both DHA and artesunate had similar antiproliferative activity (IC50 = 3–4 μM) and were more potent than artemisinin and artemether (IC50 >10 μM) (Figure 1A). Furthermore, DHA and artesunate not only exhibited a stronger cytostatic effect at low micromolar concentrations, but also exerted a stronger cytotoxic effect at the higher micromolar concentrations than artemisinin and artemether, as the original 20 000 seeded cells almost died out at 10 μM concentrations of DHA or artesunate after exposure for 6 days, as detected by morphological analysis (Supplementary Figure 1, available at Carcinogenesis Online). This is further supported by cell viability (MTS) assay. When the cells were exposed to the compounds for 48h, DHA and artesunate also displayed higher cytotoxicity than artemisinin and artemether (Figure 1B). To determine whether this is cell type dependent, more tumor cell lines were employed, including Rh1 (Ewing sarcoma), K562 (leukemia), U937 (lymphoma), PC-3 (prostate cancer) and HeLa (cervical cancer) cells. We found that again, both DHA and artesunate had similar inhibitory effects on the cell growth and were more potent than artemisinin and artemether in all cell lines tested (data not shown), suggesting that the anticancer effects of artemisinins are not cancer cell type dependent. As artesunate is metabolized to DHA in the body very rapidly (within minutes) (6,8), DHA was chosen for our further studies.

Fig. 1.

DHA inhibits proliferation and reduces viability in RMS cells. (A and B) Rh30 cells, cultured in growth medium, were exposed to artemisinin (ART), DHA, artesunate (AS) and artemether (AM) at indicated concentrations for 6 days or 48h, followed by cell counting using a Beckmann Coulter counter (A), or cell viability assay using one-solution reagent (MTS) (Promega) (B). (C) Rh30, RD and C2C12 cells, cultured in the growth medium, were treated with DHA at indicated concentrations for 6 days, followed by cell counting using a Beckmann Coulter counter. The results indicate that DHA selectively inhibited proliferation in tumor (Rh30 and RD) cells, but not in normal (C2C12) cells.

To test whether DHA is a selective anticancer agent for RMS, we further investigated its anticancer activity in two representative RMS cell lines, Rh30 (alveolar type) and RD (embryonic type) and a normal skeletal muscle cell line, mouse myoblasts (C2C12). Interestingly, treatment with DHA (0–10 μM) for 6 days dramatically inhibited proliferation of Rh30 and RD cells, but not C2C12 cells, in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1C). This was consistent with our morphological analysis, as Rh30 cells were very sensitive to the treatment with DHA (10 μM, 6 days), but C2C12 cells were considerably resistant to the same treatment (Supplementary Figure 1, available at Carcinogenesis Online). The results reveal that DHA is a promising anticancer agent for RMS selective treatment.

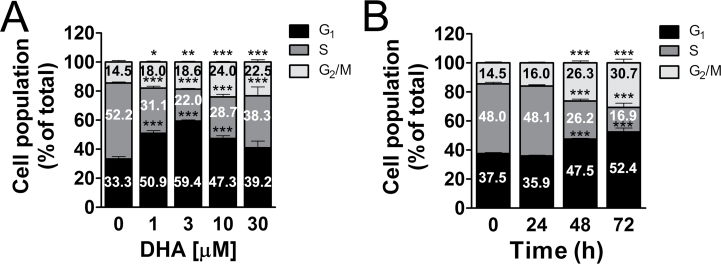

DHA arrests the cell cycle at G0/G1 and G2/M phases in RMS cells

To understand how DHA inhibits cell proliferation in Rh30 cells, cell cycle analysis was performed. As the doubling time of Rh30 cells is 36h (our unpublished observation), the cells were treated with DHA (0–30 μM) for 36h, followed by propidium iodide (PI) staining and flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 2A, treatment with DHA for 36h induced cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 and G2/M phases in Rh30 cells in a concentration-dependent manner. DHA at 3 μM significantly increased the proportion of cells in the G0/G1 phase from 34% (control) to 58%, and at 10 μM significantly increased the fraction of cells in the G2/M phase from 15% (control) to 24%. Noticeably, DHA remarkably increased sub-G1 population at 10–30 μM (Supplementary Figure 2 A, available at Carcinogenesis Online), implying cell death induced at these concentrations. In addition, treatment with DHA (10 μM) for up to 72h also induced a time-dependent cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 and G2/M phases in Rh30 cells (Figure 2B), as well as increased sub-G1 (Supplementary Figure 2 B, available at Carcinogenesis Online), consistent with the reduced cell viability (Figure 1C). Similar results were also observed in RD cells. Since both Rh30 and RD cells express mutant p53 alleles (Rh30 Arg273→Cys; RD Arg248→Trp), losing the function of p53, our findings imply that DHA is able to arrest cells in the G0/G1 and G2/M phases and inhibits cell proliferation in a p53-independent manner.

Fig. 2.

DHA induces cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 and G2/M phases in RMS cells. Rh30 cells, cultured in the growth medium, were treated with DHA for 36h at indicated concentration (A), or at 10 μM for 0–72h (B), followed by staining with PI and flow cytometry. Results are means ± standard error (n = 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

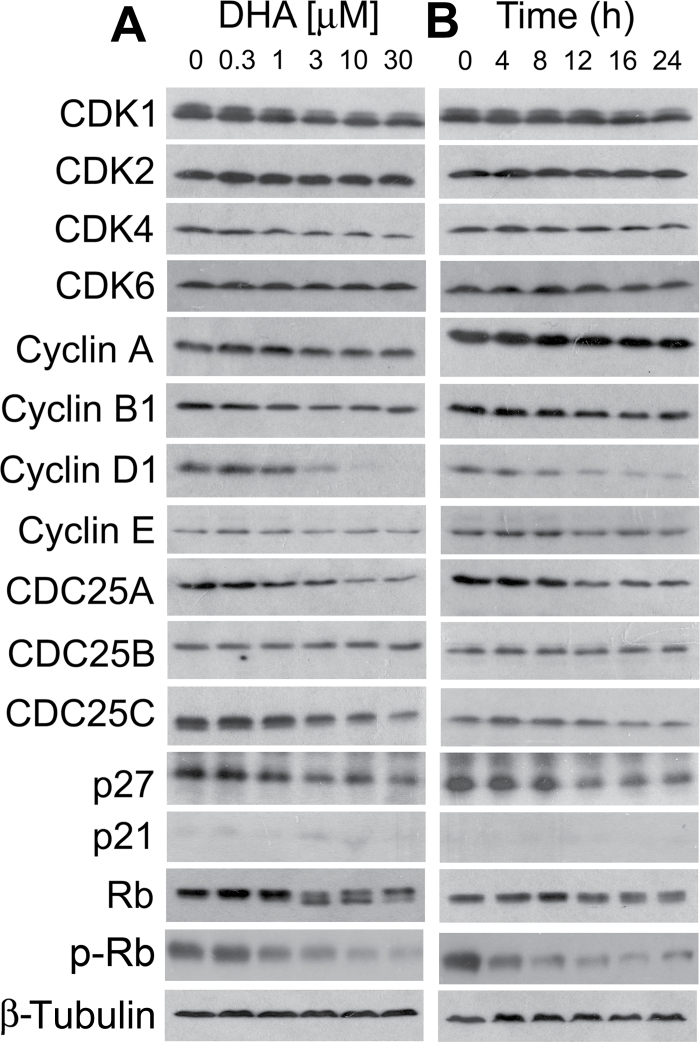

CDKs play an essential role in the regulation of cell cycle progression (63). A CDK (catalytic subunit) has to bind to a regulatory subunit, cyclin, to become active (63). Also, the activity of a CDK is regulated by CDC25 positively and by CDK inhibitor(s) negatively (63). Cyclin D-CDK4/6 and cyclin E-CDK2 complexes control G1 cell cycle progression, whereas cyclin A-CDK2 and cyclin B-CDK1 regulate S and G2/M cell cycle progression, respectively (63). Therefore, perturbing expression of CDKs and/or the regulatory proteins, such as cyclins, CDC25 and CDK inhibitors, may contribute to the altered cell cycle distribution. Since DHA induced cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 and G2/M phases (Figure 2), we next examined protein expression of CDK1/2/4/6, cyclins A/B1/D1/E, CDC25A/B/C and CDK inhibitors (p21Cip1 and p27Kip1). As shown in Figure 3A, treatment of Rh30 with DHA for 24h remarkably inhibited cellular protein expression of cyclin D1, CDC25A and CDC25C in a concentration-dependent manner. Expression of cyclin B1, CDK1 and CDK4 was slightly downregulated. Of notice, starting at 3 μM, DHA reduced expression of cyclin D1 very sharply. Protein levels of other molecules including CDK2, CDK6, cyclin A, cyclin E, CDC25B and p21Cip1 were not obviously altered (Figure 3A). Unexpectedly, expression of a CDK inhibitor, p27Kip1, was downregulated (Figure 3A). In time course studies, we also observed that DHA remarkably inhibited expression of cyclin D1, CDC25A and CDC25C in a time-dependent manner (Figure 3B). Treatment with DHA at 3 μM for 12h was able to inhibit expression of cyclin D1 profoundly. Our results suggest that DHA may inhibit expression of cyclin D1, CDK4 and CDC25A, resulting in cell cycle arrest at G1/G0 phase and inhibit expression of CDK1, cyclin B1 and CDC25C, leading to cell cycle arrest at G2/M phase.

Fig. 3.

DHA downregulates protein expression of cyclins, Cdc25 and CDKs, as well as phosphorylation of Rb in RMS cells. Rh30 cells were treated with DHA for 24h at indicated concentrations (A), or treated with DHA at 3 μM for indicated time (B), followed by western blotting with indicated antibodies. β-Tubulin was used for loading control.

As Rb, one of the most important G1 phase cyclin/CDK substrates, functions as a tumor suppressor and a regulator of cell cycle progression in the late G1 phase (63), we further investigated the effect of DHA on Rb phosphorylation. By western blot analysis, Rb was detected as a 110 kDa band in vehicle-treated control Rh30 cells (Figure 3A). After DHA (3–30 μM) treatment for 24h, a lower band, which migrates rapidly and represents the dephosphorylated protein, was observed (Figure 3A), indicating that DHA inhibited phosphorylation of Rb. This was further verified by using the antibodies against specific phospho-Rb (S807/811) (Figure 3A). Similarly, DHA (3 μM) also inhibits phosphorylation of Rb in a time-dependent manner (Figure 3B). The data indicate that DHA arrested cells in G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle due to inhibition of Rb, a consequence of inhibition of G1 CDKs.

DHA induces p53-independent apoptosis in tumor cells

To further define whether DHA-induced cell death is due to apoptosis, we carried out Annexin V-PI staining, a conventional approach to detect apoptosis. As shown in Figure 4, treatment with DHA for 72h induced apoptosis of Rh30 in a concentration-dependent manner. A representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting assay result is shown in the Supplementary Figure 3, available at Carcinogenesis Online. Exposure to DHA (10 μM, 72h) induced significant increase of the proportion of cells positive for Annexin-V/PI (~52%) as compared with non-treated cells (~5%). Treatment with the compound (10 μM) increased the number of Rh30 cells undergoing apoptosis by ~10-fold. Similar results were also seen in another RMS cell line (RD) and Ewing sarcoma cell line (Rh1) (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

DHA induces apoptosis of RMS cells in a p53-independent manner. Rh30 (p53, Arg273→Cys273) cells, cultured in the growth medium, were treated with DHA for 72h at indicated concentration, followed by Annexin V-PI staining and flow cytometry. Results are means ± standard error (n = 6). ***P < 0.001.

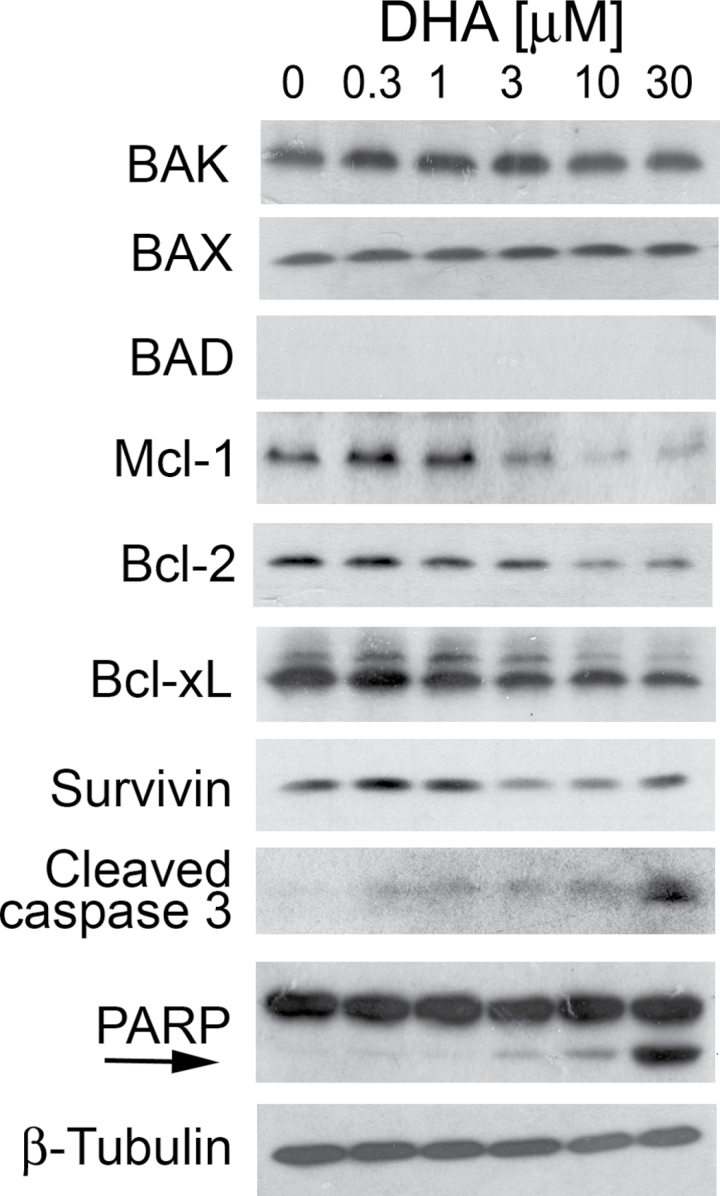

In addition, we also observed that DHA induced PARP cleavage, a hallmark of caspase-dependent apoptosis in Rh30 cells, in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 5). This is consistent with our finding that DHA increased cleavage of caspase 3 (Figure 5), indicating activation of caspase 3. It appears that treatment with DHA for 24h did not affect expression of proapoptotic proteins, such as BAD, BAK and BAX, but obviously reduced expression of antiapoptotic proteins, including Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1 and survivin, in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 5). Besides, in the time course study, we observed that treatment with DHA at 3 μM increased the expression of cleaved caspase 3 and cleaved PARP in a time-dependent manner (Supplementary Figure 4, available at Carcinogenesis Online). This was correlated to increased expression of BAD, and decreased expression of Mcl-1 (Supplementary Figure 4, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Similar results were also observed RD and Rh1 cells. As p53 is mutated in Rh30, RD and Rh1 cells, our results indicate that DHA can induce p53-independent apoptosis in the tumor cells.

Fig. 5.

DHA downregulates expression of antiapoptotic proteins and increases cleavage of PARP in RMS cells. Rh30 cells were treated with DHA for 24h at indicated concentration, followed by western blotting with indicated antibodies. Cleaved PARP is also indicated by an arrow.

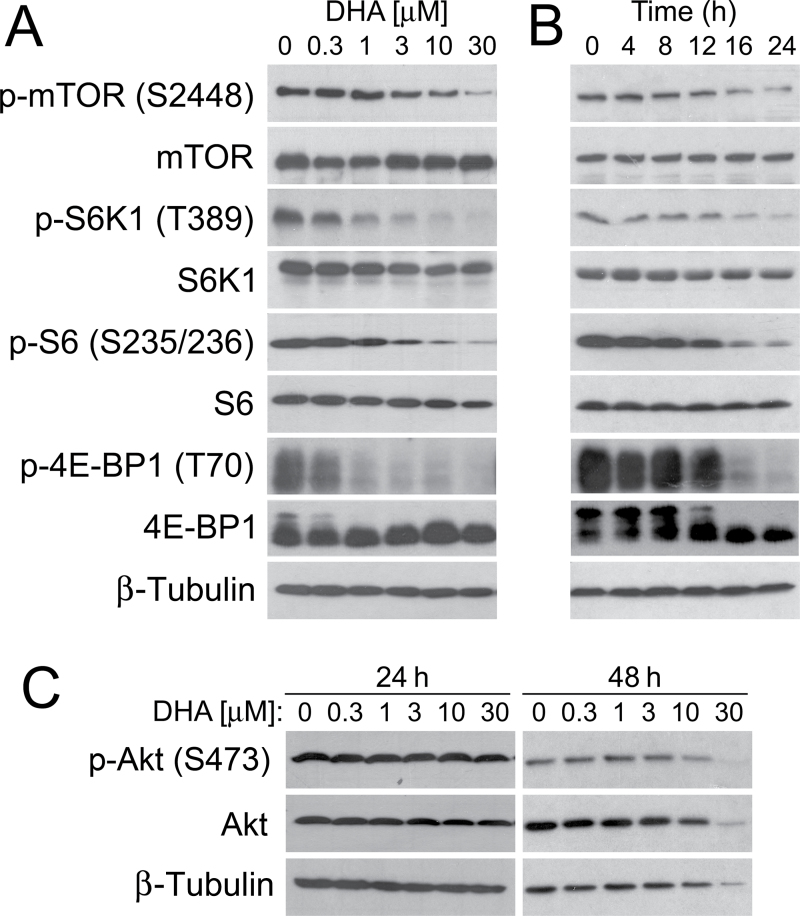

DHA inhibits mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1 but does not affect mTORC2-mediated phosphorylation of Akt

Increasing evidence has implicated that mTOR is a central controller of proliferation and survival (21). The present study and others (13–20) have demonstrated that DHA potently inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in RMS and many other cell lines. In particular, among the proteins regulated by mTOR, a number of them, such as HIF-1α, VEGF, cyclin D1, c-myc, NF-κB, Erk1/2, FAK and MMP-2, are also targeted by DHA (13–20). We therefore hypothesized that DHA might be disrupting these cellular processes by primarily inhibiting the mTOR signaling pathway. To test this, we set out to examine the effect of DHA on the mTOR signaling pathway in tumor cells. By western blot analysis, we found that DHA inhibited phosphorylation of mTOR (S2448) in a concentration- (Figure 6A) and time-dependent manner (Figure 6B). Consistently, DHA also inhibited phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1, two best-known downstream effector molecules of mTORC1. Dose–response experiments indicated that treatment with 1 μM DHA (for 24h) obviously inhibited phosphorylation of S6K1 (T389) (Figure 6A). Similarly, phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 (T70) was also inhibited (Figure 6A). As 4E-BP1 functions as a suppressor of eIF4E, and hypophosphorylated 4E-BP1 binds to and inhibits eIF4E, instead of probing more phosphorylation sites (e.g. T37/46, S65, etc.) of 4E-BP1 (21), we directly studied whether DHA affects the interaction of 4E-BP1 with eIF4E. Our 7-methyl-GTP Sepharose pull-down assay demonstrated that DHA increased the binding of 4E-BP1 to eIF4E in a concentration-dependent manner in Rh30 cells (Supplementary Figure 5, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Of note, 3–10 μM of DHA was able to induce similar amount of 4E-BP1 bound to eIF4E, as 100ng/ml of rapamycin did (Supplementary Figure 5, available at Carcinogenesis Online). The data strongly suggest that DHA suppresses mTORC1-mediated eIF4E pathway, by inhibiting phosphorylation of 4E-BP1. In addition, our time course studies showed that treatment with DHA (at 3 μM) for 16h remarkably inhibited phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1 (Figure 6B). DHA also potently inhibited phosphorylation of S6, a substrate of S6K1 (Figure 6A and B). However, treatment with DHA for 24–48h did not exhibit an obvious inhibitory or stimulatory effect on phosphorylation of Akt (S473), a best characterized substrate of mTORC2, in Rh30 cells (Figure 6C). Of note, treatment with DHA for 24h did not apparently affect the total cellular protein levels of these proteins (Figure 6A–C).

Fig. 6.

DHA inhibits mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1 but does not affect mTORC2-mediated phosphorylation of Akt. (A and B) Rh30 cells, cultured in the growth medium, were treated with DHA for 24h at indicated concentration (A), at 3 μM for indicated time (B), followed by western blotting with indicated antibodies. (C) Rh30 cells, cultured in the growth medium, were treated with DHA for indicated time at indicated concentration, followed by western blotting with indicated antibodies. S6 is a substrate of S6K1, and p-S6 (S235/236) is an indicator of S6K1 activity. β-Tubulin was used for loading control.

To exclude the possibility that DHA inhibition of mTOR signaling is cell type dependent, we extended our studies using Ewing sarcoma (Rh1). When serum-starved Rh1 cells were treated with DHA (0–10 μM) for 24 h and then stimulated with IGF-1 (10ng/ml) for 1h, western blot analysis revealed that IGF-1 stimulated phosphorylation of S6K1, 4E-BP1 and Akt (Supplementary Figure 6, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Consistent with the findings in Rh30 cells (Figure 6A), DHA exhibited an inhibitory effect only on phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1, but not on phosphorylation of Akt, in the cells (Supplementary Figure 6, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Taken together, our results indicate that DHA, at pharmacological concentrations (1–10 μM), inhibited mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1, but did not affect mTORC2-mediated phosphorylation of Akt, which was independent of the nature of cancer cell lines.

Since DHA, at concentrations of <3 μM, did not obviously inhibit cell proliferation in normal cells (C2C12) (Figure 1C), we further investigated whether this was related to poor inhibition of mTORC1 signaling in the cells. Interestingly, as expected, treatment with DHA (3 μM) for up to 24h did not obviously inhibit mTORC1 signaling, as phosphorylation of mTOR (S2448), S6K1 (T389), p-S6 (S235/236) and p-4E-BP1 (T70) was not apparently suppressed in C2C12 cells (Supplementary Figure 7, available at Carcinogenesis Online). The results indicate that DHA, at pharmacological concentrations, fails to inhibit mTORC1 signaling in normal myoblasts, and this may be the reason why DHA did not obviously inhibit proliferation in C2C12 cells (Figure 1C).

Discussion

Here, we have shown that DHA, an antimalarial drug, at pharmacological concentrations (<10 μM) (8), inhibited proliferation and induced apoptosis in cells derived from various cancer types including RMS (Rh30 and RD), but not in normal cells such as mouse myoblasts (C2C12). This suggests that DHA is possibly a selective anticancer agent and has a great potential to be repurposed for RMS cancer therapy.

Approximately 50% of human cancers, including RMS, contain a mutated form of p53, one of the most important tumor suppressor proteins in cells (64). Wild-type p53 responds to DNA damage in cells and can arrest growth of the cells to allow time for DNA repair to occur or can induce apoptosis of the cells with irreparable DNA damage (64). Cancer cells, especially those with p53 mutations, are able to escape cell cycle arrest and apoptosis despite their large number of genetic mutations/malfunctions (64). Here, we have also observed that DHA effectively inhibited cell proliferation by arresting the cells in the G0/G1 and G2/M phases of the cell cycle and induced cell death in RMS (Rh30 and RD) and Ewing sarcoma (Rh1). As these cells are p53 mutant, losing p53 function (Rh30, p53 mutant, Arg273→Cys; RD, p53 mutant, Arg248→Trp and Rh1, p53 mutant, Tyr220→Cys) (58,59), our results indicate that DHA can inhibit cell proliferation and induce cell death through a p53-independent mechanism. This observation implies that DHA may have potential applications as a chemotherapeutic agent against those p53 mutant tumor cells, which are resistant to radiotherapy or other chemotherapies. In this study, we found that treatment with DHA downregulated expression of some proteins related to cell cycle progression or cell survival, such as cyclin D1, Cdc25A, Cdc25C, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1 and survivin. However, it is not clear whether DHA inhibits expression of those proteins at transcriptional, translational and/or posttranslational level. Further research is needed to address this issue.

Although DHA has been in clinical trials as a new anticancer agent for treatment of types of cancer (6,11,12), the anticancer mechanism remains elusive. Studies have revealed that DHA targets a number of cellular proteins, which are critical for cell proliferation, survival, motility and invasion, as well as angiogenesis (13–20). Of particular interest is that among the proteins regulated by mTOR, most of them, such as HIF-1α, VEGF, cyclin D1, c-myc, NF-κB, Erk1/2, FAK and MMP-2, are also targeted by DHA (13–20). This led us to investigate whether DHA primarily inhibits mTOR signaling, thereby inhibiting expression or activities of those proteins. Here, for the first time, we demonstrate that DHA inhibited cell proliferation and induced apoptosis in RMS cells, and concurrently inhibited the signaling pathways (S6K1 and 4E-BP1) mediated by mTOR, a central controller of cell proliferation and survival (21,22). DHA inhibition of mTOR signaling was also observed in Ewing sarcoma cells (Rh1) (Supplementary Figure 6, available at Carcinogenesis Online). During the preparation of our manuscript, Zhao et al. (65) reported that DHA also inhibits mTOR-mediated phosphorylation of S6K1 induced by interleukin-2 in CD4+ T cells. These findings indicate that DHA inhibition of mTOR signaling is not cell dependent. Collectively, our results support the hypothesis that DHA may execute its anticancer activity by primarily targeting mTORC1-mediated signaling pathways.

Pharmacokinetic studies have demonstrated that when Sprague-Dawley rats were given DHA at 10mg/kg body weight, by intravenous or intramuscular injection, or by oral gavage, maximal plasma concentrations of DHA at 23.5±13.0, 5.5±1.6 and 2.7±0.8 μM are reachable, respectively (8). In this study, we found that treatment with DHA for 24h at 1 μM potently inhibited mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1 (Figure 6A). The results imply that DHA should be able to inhibit mTORC1 signaling well within the range of pharmacologically achievable concentrations in vivo. Of interest, we observed that DHA inhibition of mTORC1 did not obviously activate or inhibit the phosphorylation of Akt, a best characterized substrate of mTORC2 in RMS (Rh30) (Figure 6C) and Ewing sarcoma (Rh1) cells (Supplementary Figure 6, available at Carcinogenesis Online). This is in contrast to the effects of the conventional allosteric mTORC1 inhibitors (rapamycin and its analogs, such as CCI-779, RAD001, AP23573, etc.) or the new generation of adenosine triphosphate-competitive mTOR inhibitors (e.g. Torin1, PP242, WAY-600, Ku-0063794, OSI-027, NVP-BEZ235, PI-103, etc.). It has been observed that treatment with rapamycin for short time (e.g. 2h) or at low concentrations (e.g. 10–100nM) is able to inhibit mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1, but activate mTORC2-mediated phosphorylation of Akt (S473) (21,42–44). However, higher concentrations (e.g. >1 μM) and/or longer exposure (e.g. >24h) of rapamycin can inhibit Akt by disrupting mTORC2 complex formation (41). Adenosine triphosphate-competitive mTOR inhibitors can inhibit both mTORC1 and mTORC2 (21,22,66). Therefore, our findings highlight that DHA may represent a new class of mTORC1 inhibitor and is promising for targeted cancer therapy.

A new question that arises from the current work is how DHA inhibits mTORC1 signaling. mTORC1 is positively regulated by IGF-1R/PI3K and negatively regulated by phosphatase and tensin homolog and adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (21,22). Further research is required to determine whether DHA inhibits mTORC1 by inhibiting IGF-1R or PI3K and/or by activating phosphatase and tensin homolog or adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase.

mTORC1 mainly consists of mTOR, mLST8 and raptor (23–29). The function of mTORC1 is greatly affected by the complex integrity, especially its association with raptor (23,24). The classic mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin, disrupts the interaction of raptor with mTOR (23,24). In particular, at high concentrations (~20 μM), rapamycin induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7) by dissociating raptor from mTOR, leading to 4E-BP1 dephosphorylation (67). 4E-BPs are the major regulators of cell cycle progression and proliferation (66,68). In this study, we found that DHA potently inhibited proliferation and induced apoptosis in RMS cells. Also, DHA inhibited phosphorylation of not only S6K1 but also 4E-BP1 (Figure 6). Particularly, DHA increased 4E-BP1 binding to eIF4E (Supplementary Figure 5, available at Carcinogenesis Online), suggesting suppression of eIF4E pathway. Possibly, DHA may inhibit mTORC1 by disrupting mTORC1 formation/stability.

In addition, it has been described that PRAS40 binds the mTOR kinase domain and negatively regulates Rheb-guanosine triphosphate-induced mTORC1 activity (27,28). DEPTOR binds to and negatively regulates mTORC1 as well (29). If DHA enhances association of PRAS40 or DEPTOR to mTOR, this may also result in inhibition of mTORC1 phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1. More studies are on the way to address whether DHA inhibits phosphorylation of S6K1/4E-BP1 by disrupting mTORC1 formation and/or by enhancing the association of PRAS40 or DEPTOR with mTOR.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Figures 1–7 can be found at http://carcin.oxfordjournals.org/

Funding

National Institutes of Health (CA115414 to S.H.); American Cancer Society (RSG-08-135-01-CNE to S.H.); Carroll-Feist Predoctoral Fellowship Award (Y.O.); National Natural Science Foundation of China (81102473 to Y.L.).

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- aRMS

alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma

- CDK

cyclin-dependent kinase

- DHA

dihydroartemisinin

- eIF4E

eukaryotic initiation factor 4E

- Erk1/2

extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1/2

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HIF-1α

hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha

- IGF-1R

type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor

- MMP-2

matrix metalloproteinase-2

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-kappaB

- PARP

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PI

propidium iodide

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase

- PRAS40

proline-rich Akt substrate 40 kDa

- Rb

retinoblastoma

- RMS

rhabdomyosarcoma

- S6K1

p70 S6 kinase 1

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- 4E-BP1

4E binding protein 1.

References

- 1. Malempati S., et al. (2012). Rhabdomyosarcoma: review of the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Soft-Tissue Sarcoma Committee experience and rationale for current COG studies. Pediatr. Blood Cancer, 59, 5–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ognjanovic S., et al. (2009). Trends in childhood rhabdomyosarcoma incidence and survival in the United States, 1975-2005. Cancer, 115, 4218–4226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Punyko J.A., et al. (2005) Long-term survival probabilities for childhood rhabdomyosarcoma. A population-based evaluation. Cancer, 103, 1475–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sorensen P.H., et al. (2002). PAX3-FKHR and PAX7-FKHR gene fusions are prognostic indicators in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the children’s oncology group. J. Clin. Oncol., 20, 2672–2679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barr F.G. (2001). Gene fusions involving PAX and FOX family members in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Oncogene, 20, 5736–5746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li Y. (2012) Qinghaosu (artemisinin): chemistry and pharmacology. Acta Pharmacol. Sin., 33, 1141–1146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fairhurst R.M., et al. (2012). Artemisinin-resistant malaria: research challenges, opportunities, and public health implications. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 87, 231–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li Q.G., et al. (1998). The pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of dihydroartemisinin, arteether, artemether, artesunic acid and artelinic acid in rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol., 50, 173–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sun W.C., et al. (1992). [Antitumor activities of 4 derivatives of artemisic acid and artemisinin B in vitro]. Zhongguo Yao Li Xue Bao, 13, 541–543 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moore J.C., et al. (1995). Oral administration of dihydroartemisinin and ferrous sulfate retarded implanted fibrosarcoma growth in the rat. Cancer Lett., 98, 83–87 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Berger T.G., et al. (2005). Artesunate in the treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma–first experiences. Oncol. Rep., 14, 1599–1603 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang Z.Y., et al. (2008). [Artesunate combined with vinorelbine plus cisplatin in treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized controlled trial]. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao, 6, 134–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang X.J., et al. (2007). Dihydroartemisinin exerts cytotoxic effects and inhibits hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha activation in C6 glioma cells. J. Pharm. Pharmacol., 59, 849–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lu J.J., et al. (2010) Dihydroartemisinin accelerates c-MYC oncoprotein degradation and induces apoptosis in c-MYC-overexpressing tumor cells. Biochem. Pharmacol., 80, 22–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gao N., et al. (2011). Interruption of the MEK/ERK signaling cascade promotes dihydroartemisinin-induced apoptosis in vitro and in vivo . Apoptosis, 16, 511–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang S.J., et al. (2010). Dihydroartemisinin inactivates NF-kappaB and potentiates the anti-tumor effect of gemcitabine on pancreatic cancer both in vitro and in vivo . Cancer Lett., 293, 99–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang S.J., et al. (2011). Dihydroartemisinin inhibits angiogenesis in pancreatic cancer by targeting the NF-κB pathway. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol., 68, 1421–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhou H.J., et al. (2010). Dihydroartemisinin improves the efficiency of chemotherapeutics in lung carcinomas in vivo and inhibits murine Lewis lung carcinoma cell line growth in vitro . Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol., 66, 21–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang C.Z., et al. (2012). Dihydroartemisinin exhibits antitumor activity toward hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo . Biochem. Pharmacol., 83, 1278–1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu B., et al. (2012). Dihydroartiminisin inhibits the growth and metastasis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncol. Rep., 27, 101–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Laplante M., et al. (2012). mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell, 149, 274–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dancey J. (2010). mTOR signaling and drug development in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol., 7, 209–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hara K., et al. (2002). Raptor, a binding partner of target of rapamycin (TOR), mediates TOR action. Cell, 110, 177–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim D.H., et al. (2002). mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell, 110, 163–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim D.H., et al. (2003). GbetaL, a positive regulator of the rapamycin-sensitive pathway required for the nutrient-sensitive interaction between raptor and mTOR. Mol. Cell, 11, 895–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Loewith R., et al. (2002). Two TOR complexes, only one of which is rapamycin sensitive, have distinct roles in cell growth control. Mol. Cell, 10, 457–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sancak Y., et al. (2007). PRAS40 is an insulin-regulated inhibitor of the mTORC1 protein kinase. Mol. Cell, 25, 903–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vander Haar E., et al. (2007). Insulin signalling to mTOR mediated by the Akt/PKB substrate PRAS40. Nat. Cell Biol., 9, 316–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Peterson T.R., et al. (2009). DEPTOR is an mTOR inhibitor frequently overexpressed in multiple myeloma cells and required for their survival. Cell, 137, 873–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sarbassov D.D., et al. (2004). Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr. Biol., 14, 1296–1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jacinto E., et al. (2004). Mammalian TOR complex 2 controls the actin cytoskeleton and is rapamycin insensitive. Nat. Cell Biol., 6, 1122–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sarbassov D.D., et al. (2005). Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science, 307, 1098–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Frias M.A., et al. (2006). mSin1 is necessary for Akt/PKB phosphorylation, and its isoforms define three distinct mTORC2s. Curr. Biol., 16, 1865–1870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jacinto E., et al. (2006). SIN1/MIP1 maintains rictor-mTOR complex integrity and regulates Akt phosphorylation and substrate specificity. Cell, 127, 125–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yang Q., et al. (2006). Identification of Sin1 as an essential TORC2 component required for complex formation and kinase activity. Genes Dev., 20, 2820–2832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pearce L.R., et al. (2007). Identification of Protor as a novel Rictor-binding component of mTOR complex-2. Biochem. J., 405, 513–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Woo S.Y., et al. (2007). PRR5, a novel component of mTOR complex 2, regulates platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta expression and signaling. J. Biol. Chem., 282, 25604–25612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. García-Martínez J.M., et al. (2008). mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) controls hydrophobic motif phosphorylation and activation of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase 1 (SGK1). Biochem. J., 416, 375–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu L., et al. (2008). Rapamycin inhibits F-actin reorganization and phosphorylation of focal adhesion proteins. Oncogene, 27, 4998–5010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu L., et al. (2010). Rapamycin inhibits cytoskeleton reorganization and cell motility by suppressing RhoA expression and activity. J. Biol. Chem., 285, 38362–38373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sarbassov D.D., et al. (2006). Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol. Cell, 22, 159–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Haruta T., et al. (2000). A rapamycin-sensitive pathway down-regulates insulin signaling via phosphorylation and proteasomal degradation of insulin receptor substrate-1. Mol. Endocrinol., 14, 783–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shah O.J., et al. (2004). Inappropriate activation of the TSC/Rheb/mTOR/S6K cassette induces IRS1/2 depletion, insulin resistance, and cell survival deficiencies. Curr. Biol., 14, 1650–1656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. O’Reilly K.E., et al. (2006). mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates Akt. Cancer Res., 66, 1500–1508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hashemolhosseini S., et al. (1998). Rapamycin inhibition of the G1 to S transition is mediated by effects on cyclin D1 mRNA and protein stability. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 14424–14429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gera J.F., et al. (2004). AKT activity determines sensitivity to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors by regulating cyclin D1 and c-myc expression. J. Biol. Chem., 279, 2737–2746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Albers M.W., et al. (1993). FKBP-rapamycin inhibits a cyclin-dependent kinase activity and a cyclin D1-Cdk association in early G1 of an osteosarcoma cell line. J. Biol. Chem., 268, 22825–22829 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Morice W.G., et al. (1993). Rapamycin inhibition of interleukin-2-dependent p33cdk2 and p34cdc2 kinase activation in T lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem., 268, 22737–22745 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Beuvink I., et al. (2005). The mTOR inhibitor RAD001 sensitizes tumor cells to DNA-damaged induced apoptosis through inhibition of p21 translation. Cell, 120, 747–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nourse J., et al. (1994). Interleukin-2-mediated elimination of the p27Kip1 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor prevented by rapamycin. Nature, 372, 570–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Marx S.O., et al. (1995). Rapamycin-FKBP inhibits cell cycle regulators of proliferation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res., 76, 412–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yu K., et al. (2001). mTOR, a novel target in breast cancer: the effect of CCI-779, an mTOR inhibitor, in preclinical models of breast cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer, 8, 249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hudson C.C., et al. (2002). Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha expression and function by the mammalian target of rapamycin. Mol. Cell. Biol., 22, 7004–7014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Guba M., et al. (2002). Rapamycin inhibits primary and metastatic tumor growth by antiangiogenesis: involvement of vascular endothelial growth factor. Nat. Med., 8, 128–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Liu L., et al. (2010). Rapamycin inhibits IGF-1 stimulated cell motility through PP2A pathway. PLoS One, 5, e10578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mabuchi S., et al. (2007). RAD001 (Everolimus) delays tumor onset and progression in a transgenic mouse model of ovarian cancer. Cancer Res., 67, 2408–2413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jundt F., et al. (2005). A rapamycin derivative (everolimus) controls proliferation through down-regulation of truncated CCAAT enhancer binding protein {beta} and NF-{kappa}B activity in Hodgkin and anaplastic large cell lymphomas. Blood, 106, 1801–1807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Felix C.A., et al. (1992). Frequency and diversity of p53 mutations in childhood rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Res., 52, 2243–2247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Huang S., et al. (2001). p53/p21(CIP1) cooperate in enforcing rapamycin-induced G(1) arrest and determine the cellular response to rapamycin. Cancer Res., 61, 3373–3381 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhou H., et al. (2010). The antitumor activity of the fungicide ciclopirox. Int. J. Cancer, 127, 2467–2477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Han X., et al. (2012). Curcumin inhibits protein phosphatases 2A and 5, leading to activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and death in tumor cells. Carcinogenesis, 33, 868–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Liu L., et al. (2006). Rapamycin inhibits cell motility by suppression of mTOR-mediated S6K1 and 4E-BP1 pathways. Oncogene, 25, 7029–7040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Malumbres M., et al. (2009). Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm. Nat. Rev. Cancer, 9, 153–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Riley T., et al. (2008). Transcriptional control of human p53-regulated genes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 9, 402–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhao Y.G., et al. (2012). Dihydroartemisinin ameliorates inflammatory disease by its reciprocal effects on Th and regulatory T cell function via modulating the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. J. Immunol., 189, 4417–4425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Thoreen C.C., et al. (2009). An ATP-competitive mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor reveals rapamycin-resistant functions of mTORC1. J. Biol. Chem., 284, 8023–8032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yellen P., et al. (2011). High-dose rapamycin induces apoptosis in human cancer cells by dissociating mTOR complex 1 and suppressing phosphorylation of 4E-BP1. Cell Cycle, 10, 3948–3956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Dowling R.J., et al. (2010). mTORC1-mediated cell proliferation, but not cell growth, controlled by the 4E-BPs. Science, 328, 1172–1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.