Abstract

Background

Mutations in the Alpl gene in hypophosphatasia (HPP) reduce the function of tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP), resulting in increased pyrophosphate (PPi) and a severe deficiency in acellular cementum. We hypothesized that exogenous phosphate (Pi) would rescue the in vitro mineralization capacity of periodontal ligament (PDL) cells harvested from HPP-diagnosed subjects, by correcting Pi/PPi ratio and modulating expression of genes involved with Pi/PPi metabolism.

Methods

Ex vivo and in vitro analyses were employed to identify mechanisms involved in HPP-associated PDL/tooth root deficiencies. Constitutive expression of PPi-associated genes was contrasted in PDL versus pulp tissues obtained from healthy subjects. Primary PDL cell cultures from HPP subjects (monozygotic twin males) were established to assay alkaline phosphatase activity (ALP), in vitro mineralization, and gene expression. Exogenous Pi was provided to correct Pi/PPi ratio.

Results

PDL tissues obtained from healthy individuals featured higher basal expression of key PPi regulators, genes Alpl, progressive ankylosis protein (Ankh) and ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1 (Enpp1), versus paired pulp tissues. A novel Alpl mutation was identified in the twin HPP subjects enrolled in this study. Compared to controls, HPP-PDL cells exhibited significantly reduced ALP and mineralizing capacity, which were rescued by addition of 1mM Pi. Dysregulated expression of PPi regulatory genes Alpl, Ankh, and Enpp1 was also corrected by adding Pi, though other matrix markers evaluated in our study remained down-regulated.

Conclusions

These findings underscore the importance of controlling Pi/PPi ratio toward development of a functional periodontal apparatus, and support Pi/PPi imbalance as the etiology of HPP-associated cementum defects.

Keywords: hypophosphatasia, cementum, periodontal ligament, phosphate, pyrophosphate

Introduction

Biomineralization of bones and teeth requires a tight regulation of the ratio between concentrations of extracellular phosphate (Pi), an ion incorporated in hydroxyapatite mineral, and pyrophosphate (PPi), a potent inhibitor of mineral precipitation.1–3 Disorders arising from imbalance in the Pi/PPi ratio have been reported to produce dissimilar effects on developing dental hard tissues, prompting the hypothesis that dental tissues are differentially sensitive to Pi/PPi metabolism.4, 5 In hypophosphatasia (HPP), deficiency of serum alkaline phosphatase activity (ALP) results from mutations in the liver/bone/kidney alkaline phosphatase gene (Alpl; OMIM 171760), encoding tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP). One consequence is defective formation of acellular cementum, resulting in poor attachment of the periodontal ligament (PDL) to the root surface, and consequently, premature tooth exfoliation.6 In the Akp2 null murine model for HPP, cementum is similarly defective.7, 8 Yet in both humans and mice with reduced ALP, dentin has been reported to be unaffected or less affected than cementum.4, 8–10 Accumulation of mineralization inhibitor PPi was identified as the proximal cause for defective mineralization in skeletal and dental hard tissues. In contrast, in murine models where local PPi is deficient, namely loss of progressive ankylosis protein (ANK) or ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1 (NPP1) function, acellular cementum is markedly increased, while dentin is unaffected.5, 11

Although differences in expression of Pi/PPi regulators have been suggested between tissues of the periodontal versus pulp regions, the mechanism by which HPP affects the periodontium has not been defined at the cell/molecular level. Based on evidence from human patients and transgenic mouse models, we hypothesized that PPi-regulating factors would be expressed at higher levels in periodontal versus pulp tissues under normal conditions, and further, that establishing an appropriate Pi/PPi balance is of critical importance for directing mineralization of the root surface, i.e. cementum formation. Here, we aimed to determine levels of PPi-regulating genes in PDL vs. pulp tissues, changes in PDL cell phenotype (i.e. gene expression and mineralizing capacity) resulting from HPP, and potential for normalization of Pi/PPi ratio to correct mineralization defects in cells harvested from HPP diagnosed subjects (monozygotic twins).

Materials and methods

Human subjects

A total of 16 human subjects (6 males, 10 females) 17–22 years old were enrolled in this study, with IRB approval (University of Campinas, School of Dentistry, #065/2005). The study group consisted of 2 male monozygotic twins, and 14 normal controls. Inclusion criteria included no history of smoking, diabetes, bone metabolic disorders or other systemic disease, except for hypophosphatasia in the HPP group. For the control group, subjects were periodontally healthy with erupted teeth scheduled for extraction for orthodontic reasons, and with serum alkaline phosphatase activity (ALP) within the normal adult range (25–100 U/L). HPP subjects were monitored and treated as needed, and tooth extractions were performed as a consequence of HPP-related pathology. The 14 control subjects were split into two groups, with paired PDL and pulp tissues harvested (as described below) from n=9 control subjects, and primary PDL cell cultures established (as described below) from n=5 control subjects and n=2 HPP-diagnosed subjects. HPP patients were seen in the clinic from 1991 to the present day, while cells were harvested from HPP and normal subjects from 2004–2005.

Genetic analysis of HPP patients

H DNA from blood samples was purified from leukocytes.12 Twelve exons of Alpl (liver/bone/kidney alkaline phosphatase) were PCR-amplified.13 Sequencing analyses were performed using a sequencing reaction kit employing dye-labeled terminators,§ followed by detection on an automated sequencing system.|| The identified mutation was additionally confirmed using standard restriction enzyme digestion and electrophoresis.

Tissue harvest

In order to determine the basal levels of genes associated with Pi/PPi metabolism between PDL versus pulp tissues, comparisons were made from paired tissues taken from the same tooth. Teeth were extracted from control subjects, rinsed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and PDL tissues removed by scraping the root surface. Next, the teeth were cracked open and pulps were removed with sterile forceps. Tissues were immersed in an RNA stabilization solution¶ and stored at −80°C. Total RNA was isolated by the guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction method# in conjunction with automated ceramic bead homogenization.** Non-pooled PDL and pulp tissue RNA samples were analyzed for basal gene expression using quantitative PCR.

Cell isolation and culture

Extracted teeth were placed in biopsy media, and PDL cells were obtained by enzymatic digestion (3mg/ml collagenase type I and 4 mg/ml dispase††) for 1h at 37°C. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin,†† incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. Equivalent passages 2–4 for control and HPP-PDL primary cells were used for all experiments.

Cell proliferation

Cells were seeded at 1.5×104 cells/cm2 in 96-well plates in DMEM with 2% FBS from 24h to 6 days. Cells were counted by hemacytometer and analyzed by a colorimetric formazan-based cell proliferation assay.‡‡

Alkaline phosphatase activity

Cells were seeded at 2.0×104 cells/cm2 in 60 mm plates in DMEM with 2% FBS and 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid (AA) up to 21 days. Relative ALP activity was measured using a commercial kit§§ as previously reported.14 Brifely, media were removed, cells were rinsed with PBS, and release of thymolphthalein from thymolphthalein monophosphate substrate was measured by absorbance readings at 590 nm after 30 min incubation at 37°C. Results were expressed as ALP activity normalized to total protein content per well.

Mineralization assay

Cells were seeded at 2.0×104 cells/cm2 in 24-well plates under non-mineralizing (2% FBS and AA) or mineralizing conditions up to 28 days. Mineralizing conditions included 2% FBS and AA plus a phosphate source, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate (βGP)|||| or 1 mM inorganic phosphate (Pi) (a solution of monobasic and dibasic sodium phosphates, pH 7.4).|||| The dose 1 mM Pi was chosen based on previous work with Pi and cementoblasts,15, 16 as well as preliminary experiments with PDL cells to determine a non-toxic dose of Pi that was sufficient to allow mineral nodule formation (data not shown). Mineral nodules were detected by von Kossa (VK) assay and alizarin red-S staining (AR, 40mM, pH4.2).|||| AR stain was quantified by measuring absorbance of bound dye (570 nm) solubilized in 10% cetylpyridinium chloride,¶¶ as previously described.17

Gene expression assay

Cells were seeded at 2.0×104 cells/cm2 in 60 mm plates in non-mineralizing and mineralizing media (with added Pi), as outlined above, for up to 20 days. Total RNA was extracted as described for tissues above,# DNase treated,## and used for cDNA synthesis with a recombinant reverse transcriptase kit.*** Quantitative real-time PCR reactions were performed using a SYBR green based hot start PCR kit.††† Relative quantification was performed using amplification efficiency correction with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) as the reference gene. Assessed genes and primers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

PCR primer sequences and associated Genbank references.

| Gene | Name | Primer Sequence (5′ → 3′) | Genbank number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpl | Tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase | CGGGCACCATGAAGGAAAG GCCAGACCAAAGATAGAGTT |

NM_000478 |

| Ankh | Progressive ankylosis protein | GAGGTGACAGACATCGTGG CCTTTAAATCAAGGCCTCTTTCATTAC |

NM_054027.4 |

| Enpp1 | Ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase phosphodiesterase 1 | AAATATGCAAGCCCTCTTTGT TTTAGAAGGTGGTTAAGACTTCCATGA |

NM_0062208.2 |

| Bsp | Bone sialoprotein | GAGGGCAGAGGAAATACTCAAT ATTCAAAGCCAAGTTCAGAGATGTAAA |

NM_004967.3 |

| Col1 | Collagen type 1 alpha 1 | CCCTGGTGCTACTGGTT ACCACGCTGTCCAGCAATA |

NM_000088.3 |

| Dmp1 | Dentin matrix protein 1 | AGCCATTCTGAGGAAGACGA TGTTGTGATAGGCATCAACTGTTA |

NM_004407 |

| Ocn | Osteocalcin | AGCTCAATCCGGACTGT GGAAGAGGAAAGAAGGGTGC |

NM_199173.4 |

| Opn | Osteopontin | AAAGCCAATGATGAGAGCAA ATTTCAGGTGTTTATCTTCTTCCTTAC |

NC_000004 |

| Gapdh | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC |

NM_002046 |

Statistical analysis

All cell and tissue experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least twice. Values are given as means and standard deviation (SD). Intragroup and intergroup comparisons were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls method (α=0.05) for proliferation and mineralization assays, and gene expression. A Student t-test was used for intergroup comparisons for ALP activity. Statistical power was at least 0.08 with α=0.05 for any statistical test.

Results

Diagnosis of hypophosphatasia

Male identical twins of Caucasian descent were brought for dental evaluation by their parents to the University of Campinas, Dental School at Piracicaba, Brazil. HPP individuals were evaluated for possible mineralized tissue disorders at the age of 2 years old because of reported premature exfoliation of anterior primary teeth. Physical examination and radiography (long bones, joints, and skull) did not indicate additional aberrant findings. Biochemical analysis revealed low serum ALP activity (patient A: 62 U/L, patient B: 63 U/L; normal range for children 151–471 U/L). Serum Pi and calcium serum levels were normal. Based on the above, a diagnosis of HPP subtype odontohypophosphatasia was given.

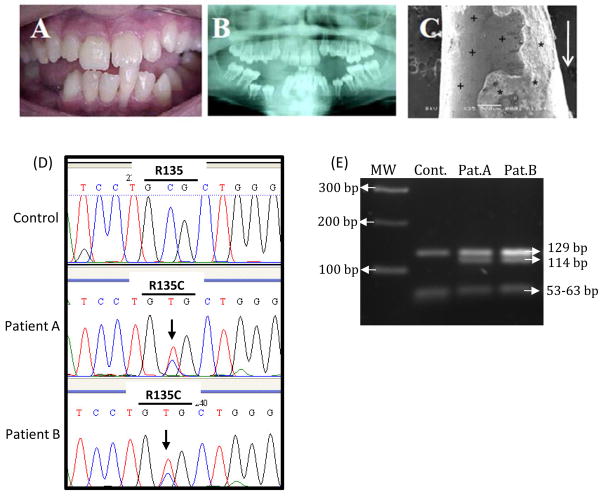

Over subsequent years, patients suffered premature exfoliation of primary and permanent teeth. Permanent dentition featured short roots, wide pulp chambers, and reduced alveolar bone height (Figure 1A–C). At age 22, when cells were harvested for this study, ALP activity remained low, 8U/L and 6U/L, for patient A and B, respectively (normal adult range is25–100 U/L).

Figure 1. Hypophosphatasia (HPP) patients.

(A) At 14 years old, patient A experienced spontaneous exfoliation of a permanent mandibular central incisor (tooth 31 by FDI notation) during brushing. (B) Corresponding panoramic radiograph, showing effects of odonto-HPP on the permanent dentition, including delayed eruption of several permanent teeth (e.g. mandibular premolars 34, 35, 44, and 45), enlarged pulp chambers, and thin dentin. (C) SEM imaging of the apical root region of tooth 31 demonstrates lack of cementum and exposed dentin surface with absence of attached collagenous PDL fibers (+), as well as evidence of root dentin resorption (*). Arrow indicates the occlusal direction. (D) Representative DNA sequencing electropherogram showing sequencing analysis of exon 5 of the Alpl gene in control versus patients A and B. The control subject is homozygous for C in the second position of codon 135 (454 nt), while the HPP patients are heterozygous, presenting both a normal (C) and altered allele (T) in the 454-nt position (R135C). Arrow indicates the position of nucleotide substitution in codon 135 GCG (Arginine) > GTG (Cysteine). (E) Confirmation of Alpl missense mutation was performed by enzymatic digestion, demonstrating the Hha I restriction site was abolished. MW: molecular weight marker.

Sequencing the Alpl gene revealed a heterozygous transition 454C>T in exon 5 of both patients, leading to substitution of cysteine for arginine at position 135 (R135C) (Figure 1D). The missense mutation was confirmed by HhaI digest, demonstrating the expected restriction site 5′-GCGC-3′ was abolished (Figure 1E). fragments of 129, 63, 61 and 53 bp (from three restriction sites), in the HPP patients, loss of one of While digest of the control 306 bp Alpl exon 5 produced these restriction sites by Alpl mutation resulted in fragments of 129, 114, and 63 bp.

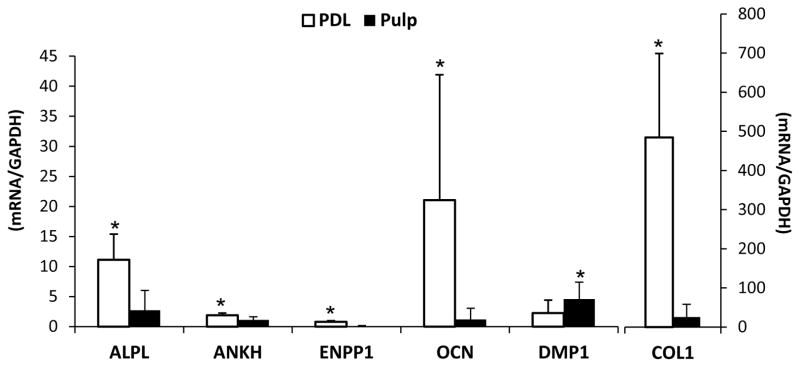

Pyrophosphate regulators are differentially expressed in PDL versus pulp tissues

Dissimilar effects of mineralization disorders on individual dental hard tissues during formation have prompted the hypothesis that cementogenesis and dentinogenesis are regulated by disparate mechanisms.4, 5 Constitutive gene expression was compared in PDL versus pulp tissues harvested from healthy subjects. PDL tissues featured significantly higher (p<0.05) mRNA levels for Alpl, Ankh, and Enpp1, all key regulators of local PPi levels (Figure 2). Gene expression of other mineralized tissue markers (not associated with PPi metabolism) was determined in order to consider the specificity of differences between PDL and pulp in PPi associated genes. PDL featured 10-fold higher expression of osteocalcin (Ocn), and an almost 20-fold greater expression of type I collagen (Col1) versus pulp, while dentin matrix protein 1 (Dmp1)was expressed at twice the levels in pulp versus PDL.

Figure 2. Expression of pyrophosphate and mineralization related genes in PDL and pulp tissues.

Gene expression was assayed in non-pooled PDL and pulp tissues from 9 normal subjects (17–22 years old, 2 males and 7 females). Mean and SD for mRNA levels of Alpl, Ankh, Enpp1, Ocn, Dmp1 and Col1. PDL expressed significantly higher mRNA levels for PPi regulators Alpl, Ankh, and Enpp1, and for mineralization associated genes Ocn and Col1. In contrast, Dmp1 was expressed at higher levels in pulp. Both left and right axes represent relative gene expression, with the left axis representing genes Alpl to Dmp1, and the right axis representing more highly expressed Col1. (*): statistically different by the Student t-test (α=0.05).

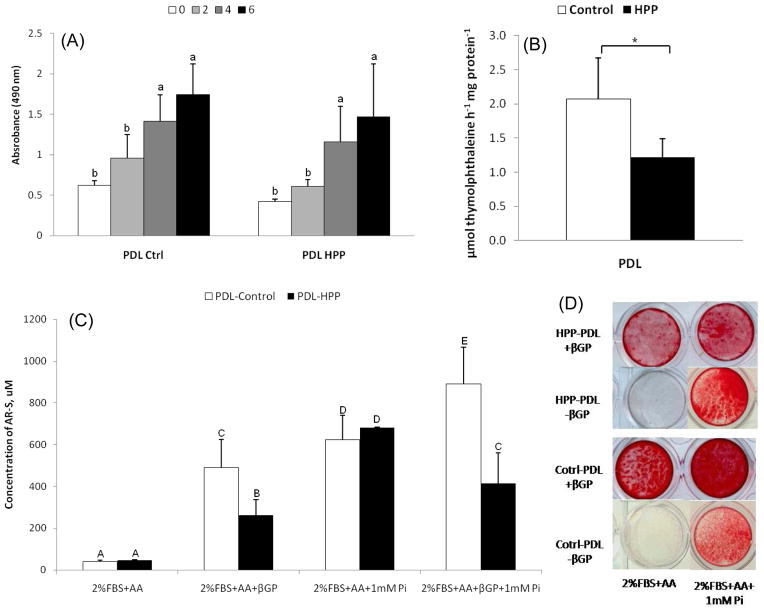

The mineralization deficiency in HPP cells can be rescued by addition of inorganic phosphate

In light of basal differences in expression of PPi regulators observed in PDL versus pulp tissues, primary PDL cell cultures were established from HPP patients and normal (control) subjects to define the mechanism by which mineralization deficiency occurs on the root surface in HPP. PDL cells from controls and HPP patients showed a typical spindle-shaped fibroblastic morphology and monolayer attachment (data not shown). Cell counting and MTS assay indicated proliferation and cell viability were comparable in control versus HPP cells (Figure 3A). However, in agreement with serum biochemical results on HPP patients A and B, ALP activity in HPP-PDL cells was significantly decreased (p<0.05) to approximately 40% of control (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Rescue of HPP mineralization deficiency by addition of inorganic phosphate.

(A) Control and HPP-PDL cells grown in 2% FBS were counted by MTS method. Values corresponding to relative cell numbers are shown as mean ± SD (absorbance at 490nm). Proliferation and cell viability were equivalent between HPP and control cells, except at day 2. (*): Intragroup significant differences versus day 0 by Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls method (α=0.05), and (&) intergroup significant differences within the same period of time by the Student t-test. (B) Relative alkaline phosphatase activity (ALP) was significantly lower in HPP-PDL cells versus controls. (*): statistically different by the Student t-test (α=0.05). (C and D) Alizarin red assay for in vitro mineralization. Control and HPP-PDL cells grown in 2% FBS, and compared to controls, HPP-PDL cells displayed a severely limited mineralization capacity with βGP as a phosphate source. The HPP mineralization deficiency was rescued when 1mM Pi was used as the phosphate source. Different capital letters indicate intergroup statistical differences (control versus HPP) for α = 0.05, using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Student-Newman-Keuls method.

Heterogeneous primary PDL populations have been shown to harbor progenitor cells capable of promoting mineral nodule formation in cementoblast-like fashion when incubated under pro-mineralizing conditions, which includes AA and a phosphate source.18–20 An in vitro mineralization assay was performed to determine the effect of reduced ALP on HPP-PDL cell mineral nodule formation versus control cultures. Mineralizing conditions were created using either of two phosphate sources, β-glycerophosphate (βGP) or inorganic phosphate (Pi). While Pi can be directly incorporated into hydroxyapatite crystals, release of Pi ions from the organic phosphate source βGP requires phosphatase activity, such as that mediated by ALP.

In the absence of Pi or βGP, mineral nodules were not produced by either control or HPP-PDL cultures (Figure 3C–D). Addition of βGP resulted in mineral nodule formation by 28 days in both control and HPP-PDL cells, but HPP-PDL cells displayed a severely limited mineralization capacity. Quantification of AR staining revealed 6-fold greater mineral formation in control versus HPP-PDL cells (p<0.05), confirming that HPP cells could not adequately release Pi ions from βGP due to severely reduced ALP activity (Figure 3B–C). However, when 1mM Pi was used as the phosphate source, the HPP mineralizing deficiency was rescued and control and HPP cells exhibited equivalent mineral nodule formation. These results suggest that aside from reduced TNAP function, HPP-PDL cells retain a similar capacity to create a mineralized matrix.

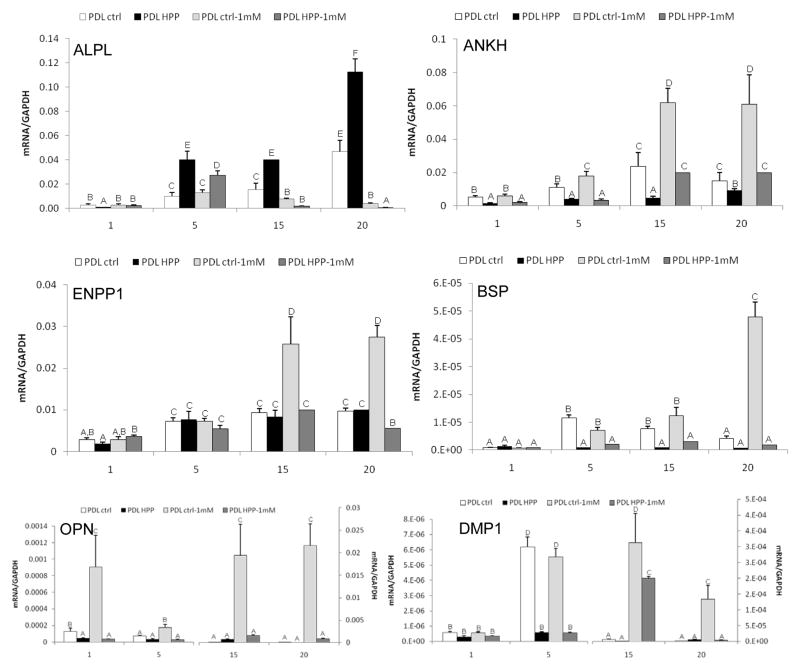

Addition of inorganic phosphate to HPP PDL cells partially rescues altered gene expression

To provide insight into the mineralization deficiency of HPP-PDL cells, expression levels for PPi-associated genes were determined over time (Figure 4). Additionally, in order to determine the extent that local Pi insufficiency or reduced Pi/PPi ratio may affect cell phenotype, 1mM exogenous Pi was added to cultures of HPP-PDL cells versus controls. Interestingly, HPP-PDL cells featured significantly increased levels of mRNA for Alpl at days 5–20, suggesting a feedback mechanism in attempt to compensate for ALP functional deficiency. Expression of PPi regulatory gene Ankh was reduced in HPP-PDL cells versus control over all time points. Addition of exogenous Pi enhanced expression of Ankh in treated versus untreated HPP-PDL cells, restoring Ankh mRNA levels equivalent to controls by 15 days. In control cells, addition of Pi increased Ankh expression. While Pi-treated HPP-PDL cells increased Ankh by a greater fold-change than controls, the absolute levels of Ankh in these cells only matched untreated control PDL cell levels. Unlike Ankh, Enpp1 expression was unperturbed in HPP-PDL cells, and furthermore, Enpp1 expression was not altered in response to Pi. In contrast, control PDL cells increased Enpp1 expression in response to Pi addition.

Figure 4. Addition of phosphate corrects pyrophosphate regulatory genes in HPP-PDL cells.

Gene expression for PPi regulating factors (Alpl, Ankh, Enpp1) and genes associated with regulation of mineralization (Bsp, Opn, Dmp1) in control versus HPP-PDL cells, with or without 1mM Pi treatment. While addition of Pi rescued expression of PPi associated genes in HPP cells, other mineral markers were not corrected. Different capital letters indicate intergroup statistical differences (control vs. HPP, +/− Pi treatment)within the same time point (day 1, 5, 15, or 20)for α = 0.05, using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Student-Newman-Keuls method.

Expression of cementoblast/osteoblast marker genes bone sialoprotein (Bsp) and osteopontin (Opn) were also determined, as well as the cementocyte/osteocyte marker dentin matrix protein 1 (Dmp1), a gene whose protein is associated with systemic Pi regulation, and which is responsive to mineralizing conditions in cementoblasts and PDL cells grown in vitro.15, 21–25 In control PDL cells under mineralizing conditions (addition of Pi), expression of Bsp, Opn, and Dmp1 along with mineral nodule formation indicated a cementoblast-like phenotype. Bsp was significantly down regulated in HPP-PDL cells at days 5–20, and could not be rescued by Pi addition. Opn expression was similar in both cell types, however addition of Pi enhanced Opn expression only in control cells. HPP-PDL cells expressed lower levels of Dmp1 mRNA than controls, although exposure of HPP-PDL cells to Pi enhanced Dmp1 transcripts in similar fashion as in control cells. Thus, with addition of Pi to correct Pi/PPi ratio, HPP-PDL cells were partially rescued to a control PDL cell profile, including both mineralization and gene expression.

Discussion

Dissimilar effects of mineralization disorders on formation of cementum versus dentin suggest these tissues and their respective cells are subject to different developmental influences. It has been hypothesized that periodontal tissues (PDL/cementum) fall more under the influence of PPi metabolism than pulp/dentin.4, 5 Here we confirm that periodontal tissues feature higher basal levels of PPi-regulating genes than pulp. Regulation of genes associated with PPi metabolism was further probed in PDL cell populations by employing primary cell cultures from HPP patients and control subjects. HPP-PDL cells exhibited low ALP activity and reduced ability to promote mineralization, a deficiency that was rescued by addition of inorganic Pi. HPP-PDL cells expressed altered levels of PPi associated genes compared to controls, but like mineralization, these genes were largely rescued by Pi to levels equivalent to controls. In contrast, mineralization marker genes Bsp and Opn remained altered in HPP cells, suggesting that rescue by Pi may not completely restore the ability of PDL cells to express a cementoblast-like phenotype when appropriately prompted, even though mineral nodule formation was restored.

The periodontium is a phosphate/pyrophosphate sensitive tissue

Pi homeostasis is essential for normal development and maintenance of skeletal tissues, including the dentition.1 Conversely, PPi is a potent inhibitor of hydroxyapatite mineral growth.26 Local regulation of Pi and PPi levels thus dictate mineralization, and hydrolysis of PPi liberates Pi and relieves inhibition of mineralization. The enzyme TNAP hydrolyzes PPi to Pi, and is expressed by cells with the capacity to promote mineralization, including osteoblasts, cementoblasts, odontoblasts, PDL cells, and dental pulp cells. In HPP, mutations in Alpl cause reduced TNAP function, resulting in skeletal mineralization defects including rickets and osteomalacia.27, 28 Dental case reports indicate compromised periodontal attachment and exfoliation of teeth due to aplasia or severe hypoplasia of the acellular cementum.4, 6, 29, 30 Dentin has been described as normal, or variably affected in HPP, with reports of thin dentin, wide pulp cavities, or “shell teeth.”9, 10, 31, 32 In studies of Akp2 null mice, a model for human HPP, acellular cementum was inhibited while dentin was reported to be unaffected.8 The actions of additional extracellular PPi regulators balance and temper TNAP activity. The progressive ankylosis protein (ANK) and ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase phosphodiesterase 1 (NPP1) both increase extracellular PPi via different mechanisms, effectively regulating physiologic mineralization and pathologic calcification.3, 17, 33–35 Intriguingly, both Ank and Enpp1 mutant/null mice feature significantly increased acellular cementum, while dentin was unaltered.5, 11, 36

Studies to identify the mechanism for disparity in mineral metabolism of cementum versus dentin have yielded some clues. Van den Bos et al. reported higher Enpp1 gene expression, NPP-like activity, ALP activity, and PPi concentrations in tissues from the PDL versus pulp region.4 Following on this work, we have identified relatively greater gene expression of primary PPi regulatory factors Alpl, Ankh, and Enpp1 in tissues obtained from the PDL versus pulp regions in a sample population of healthy patients. These results suggest that PPi metabolism in the PDL is a more dynamically regulated process, predisposing the periodontia to be sensitive to changes in PPi regulators. This may in part be tied to the high rate of turnover of PDL, reflected here by about 20-fold greater expression of Col1 in tissue from PDL versus pulp regions. However, there is also compelling evidence that acellular cementum formation is more dependent than dentin and bone on creation of a physical-chemical mineralization environment. Evidence for this comes from studies on normal development of acellular cementum,37 as well as reports of disturbances from naturally occurring mineral inhibitors38 or from pharmacological agents like bisphosphonates, which are PPi analogs.39, 40 In our studies of cementogenesis, we have found that both positive and negative regulation of mineral inhibitor PPi near the developing root surface has profound consequences on cementum formation,5, 11 and these results from a normal human subject population are in line with our and others data.

HPP affects periodontal cell function

Sequencing the Alpl gene in the two HPP-diagnosed siblings revealed a heterozygous transition 454C>T in exon 5 of both patients, leading to substitution of cysteine for arginine at position 135 (R135C). The particular R135C alteration described here has not been previously reported for odonto-HPP, though codon 135 was linked to a case of adult-onset HPP (R135C/R167W; SESEP - University of Versailles-Saint Quentin), as well as to a lethal HPP case (R135H)41, suggesting genotype-phenotype correlation. HPP has been linked with a large spectrum of mutations, with no clear pattern linking location of mutations with clinical form of HPP, onset or severity of disease.13

Changes in cell profile associated with dysregulated PPi metabolism were further probed by employing primary cell cultures obtained from control and HPP patients. One limitation of this approach was our reliance on only two HPP-diagnosed siblings for cell isolation. As HPP is a rare disease, we were not able to identify additional individuals for inclusion in the study. The patients described here were diagnosed with an odonto-specific subtype of HPP where serum biochemistry is abnormal and dental defects are the primary phenotypic traits.27, 28 To our knowledge, this is the first report examining the mineralization capacity and gene expression profile of dental cells isolated from HPP patients.

No differences were noted in morphology, proliferation, or viability between HPP and control cells, in agreement with studies of HPP dermal fibroblasts.42–44 ALP activity and mineralization capacity for HPP-PDL cells were present but significantly impaired, as reported for osteoblasts from Akp2 null mice,45 and in agreement with studies of genotype-phenotype correlation indicating that human HPP patients with milder forms of HPP (e.g. odonto-HPP) exhibit residual ALP activity.28, 30 When 1mM exogenous Pi was added as a phosphate source for mineralization and to correct the Pi/PPi ratio, the HPP-PDL cell mineralization deficiency was corrected to normal levels. This result suggests that PDL cells lacking TNAP function are otherwise competent to promote mineralization.

In order to further define the behavior of periodontal cells derived from HPP subjects, we elected to assay genes involved in PPi regulation (Alpl, Ankh, Enpp1) and in cementoblast/osteoblast mineralization (Bsp, Opn, and Dmp1). Intriguingly, expression of Alpl and Ankh mRNAs were dysregulated in HPP-PDL cells compared to controls. Increased Alpl may be indicative of a response to high PPi levels due to reduced ALP, a corrective feedback response. Reduced Ankh may reflect the lack of mineralizing phenotype in HPP cells, as we have identified the homologous gene Ank as a mineralization-coupled gene in mouse cementoblasts.11 These trends were corrected by Pi addition, which also returned the capacity for PDL cells to promote mineralization nodule formation, when triggered appropriately.

Control PDL cell populations exhibited the ability to take on a cementoblast-like phenotype under mineralizing conditions (addition of Pi), including mineral nodule formation and expression of cementoblast-associated marker/extracellular matrix (ECM) genes Bsp, Opn, and Dmp1. HPP-PDL cells featured altered expression of Bsp, Opn, and Dmp1. Expression of both Bsp and Dmp1 were reduced in HPP-PDL cells versus control cells. Addition of Pi partially corrected Dmp1 expression, while Bsp expression was not restored. Basal levels of Opn were similar in HPP and control cells; however, unlike controls, which exhibited a marked increase in Opn transcripts with addition of Pi, no increase in Opn mRNA was noted in HPP cells under similar conditions. this gene did not respond to added Pi, whereas control Opn was markedly increased. Bsp and Opn proteins are considered key markers for cementum,21, 22, 46 therefore alterations in basal and/or Pi-stimulated levels of these genes suggest that Pi addition did not in total restore PDL cell behavior. OPN is an inhibitor of mineralization, and studies in Akp2 null mice found that increased Opn mRNA in osteoblasts, and greater circulating OPN, were partially responsible for bone hypomineralization.3, 33 The response of human HPP-PDL cells to PPi dysregulation thus contrasts what has been reported in osteoblasts, highlighting potential differences between the skeleton and dental tissues. It should be noted that this portion of the study relied on analysis of mRNA levels. In murine cementoblasts, we reported that both Opn and Dmp1 genes are coupled with mineralization,11 thus it becomes difficult to determine whether or not differences in ECM genes contribute to the mineralization phenotype, or occur as a result of the mineralization phenotype. This is an area of ongoing investigation.

Examination of the expression patterns of selected genes provides two intriguing insights: 1) correction of mineralization coincides with correction of genes associated with regulation of PPi in HPP-PDL cells; and 2) correction of mineralization and PPi regulators does not require correction of mineralization-linked markers (e.g. Bsp, Opn). In light of previous data outlined above, we interpret these results from human PDL cells in vivo and in vitro to support the hypothesis that PPi regulation may be more active in the periodontium compared to other dental tissues like pulp/dentin, and more critical to cementogenesis, i.e. a primary requirement for this tissue is a local Pi/PPi environment that can promote mineralization.

Insight into the role of Pi/PPi ratio on dental development and function not only identifies developmental regulation and pathological mechanisms, but may inform regenerative therapies, and thus we have extended this hypothesis to cementum regeneration studies in mice.47 The results from these regeneration studies support our findings here. Specifically, we demonstrated that cementum regeneration in Ank KO mice (which feature PPi deficiency) was more rapid and more extensive when compared to comparably treated control mice. Local modulation of Pi/PPi may prove to be a promising novel approach for promoting regeneration of cementum.

Conclusions

Ex vivo and in vitro findings in the present study underscore the importance of controlling Pi/PPi ratio toward development of a functional periodontal apparatus, and support Pi/PPi imbalance as the etiology of HPP-associated cementum defects. Periodontal tissues featured higher constitutive expression of central regulators of PPi compared to pulp tissues. PDL cells isolated from HPP subjects diagnosed with a novel Alpl mutation exhibited reduced ALP activity and capacity for mineralization, and dysregulated PPi regulatory genes, all of which were corrected by normalizing Pi/PPi ratio in vitro. The important influence of PPi metabolism on cementum development suggests that targeted modulation of Pi/PPi may provide a novel approach for achieving cementum regeneration.

Summary.

Primary periodontal ligament (PDL) cells obtained from hypophosphatasia (HPP) patients exhibit decreased mineralization and altered expression of PPi associated genes. Correction of Pi/PPi ratio normalizes PPi regulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs. Ana Paula Giorgetti (State University of Campinas, School of Dentistry, Piracicaba, SP, Brazil) for clinical support and Dr. Marisi Aidar (State University of Campinas, School of Dentistry, Piracicaba, SP, Brazil) for genetic analyses. Studies were supported by São Paulo State Research Foundation (FAPESP, Brazil, grant #07/08192-5 and 08/00534-7 (FHNJ), National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) grant DE15109 (MJS), and NIH Fogarty International Research Collaboration Award (FIRCA) grant 5R03TW007590-03 (MJS/FHNJ).

Footnotes

ABI DYEnamic ET Terminator cycle sequencing kit, GE Healthcare UK Limited, Buckinghamshire, UK

ABI PRISM™ 3100 sequencer, Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA

RNAlater®, Ambion Inc., Austin, TX

TRIZOL® reagent, Gibco BRL, Carlsbad, CA

MagNA Lyser, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN

Gibco BRL

Promega, Madison, WI

Labtest Diagnostica, Lagoa Santa, MG, Brazil

Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO

MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH

Turbo DNA-free®, Ambion, Austin, TX

Transcriptor reverse transcription kit, Roche Diagnostic, Indianapolis, IN

FastStart DNA Masterplus, Roche Applied Science

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in these studies.

References

- 1.Foster BL, Tompkins KA, Rutherford RB, et al. Phosphate: known and potential roles during development and regeneration of teeth and supporting structures. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2008;84:281–314. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murshed M, Harmey D, Millán J, McKee M, Karsenty G. Unique coexpression in osteoblasts of broadly expressed genes accounts for the spatial restriction of ECM mineralization to bone. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1093–1104. doi: 10.1101/gad.1276205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harmey D, Hessle L, Narisawa S, Johnson KA, Terkeltaub R, Millan JL. Concerted regulation of inorganic pyrophosphate and osteopontin by akp2, enpp1, and ank: an integrated model of the pathogenesis of mineralization disorders. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1199–1209. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63208-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Bos T, Handoko G, Niehof A, et al. Cementum and dentin in hypophosphatasia. J Dent Res. 2005;84:1021–1025. doi: 10.1177/154405910508401110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nociti FH, Jr, Berry JE, Foster BL, et al. Cementum: a phosphate-sensitive tissue. J Dent Res. 2002;81:817–821. doi: 10.1177/154405910208101204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapple IL. Hypophosphatasia: dental aspects and mode of inheritance. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20:615–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1993.tb00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKee MD, Nakano Y, Masica DL, et al. Enzyme Replacement Therapy Prevents Dental Defects in a Model of Hypophosphatasia. J Dent Res. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0022034510393517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beertsen W, VandenBos T, Everts V. Root development in mice lacking functional tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase gene: inhibition of acellular cementum formation. J Dent Res. 1999;78:1221–1229. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780060501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsson A, Matsson L, Blomquist HK, Larsson A, Sjodin B. Hypophosphatasia affecting the permanent dentition. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25:343–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu H, Li J, Lei H, Zhu T, Gan Y, Ge L. Genetic etiology and dental pulp cell deficiency of hypophosphatasia. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1373–1377. doi: 10.1177/0022034510379017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster BL, Nagatomo KJ, Bamashmous SO, et al. The Progressive Ankylosis Protein Regulates Cementum Apposition and Extracellular Matrix Composition. Cells Tissues Organs. 2011 doi: 10.1159/000323457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aidar M, Line SR. A simple and cost-effective protocol for DNA isolation from buccal epithelial cells. Brazilian dental journal. 2007;18:148–152. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402007000200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mornet E, Taillandier A, Peyramaure S, et al. Identification of fifteen novel mutations in the tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNSALP) gene in European patients with severe hypophosphatasia. Eur J Hum Genet. 1998;6:308–314. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodrigues TL, Marchesan JT, Coletta RD, et al. Effects of enamel matrix derivative and transforming growth factor-beta1 on human periodontal ligament fibroblasts. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:514–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster BL, Nociti FH, Jr, Swanson EC, et al. Regulation of cementoblast gene expression by inorganic phosphate in vitro. Calcified tissue international. 2006;78:103–112. doi: 10.1007/s00223-005-0184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rutherford R, Foster B, Bammler T, Beyer R, Sato S, Somerman M. Extracellular phosphate alters cementoblast gene expression. J Dent Res. 2006;85:505–509. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hessle L, Johnson KA, Anderson HC, et al. Tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase and plasma cell membrane glycoprotein-1 are central antagonistic regulators of bone mineralization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9445–9449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142063399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arceo N, Sauk J, Moehring J, Foster R, Somerman M. Human periodontal cells initiate mineral-like nodules in vitro. J Periodontol. 1991;62:499–503. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.8.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nohutcu R, McCauley L, Koh A, Somerman M. Expression of extracellular matrix proteins in human periodontal ligament cells during mineralization in vitro. J Periodontol. 1997;68:320–327. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.4.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaneda T, Miyauchi M, Takekoshi T, et al. Characteristics of periodontal ligament subpopulations obtained by sequential enzymatic digestion of rat molar periodontal ligament. Bone. 2006;38:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacNeil R, Berry J, D’Errico J, Strayhorn C, Piotrowski B, Somerman M. Role of two mineral-associated adhesion molecules, osteopontin and bone sialoprotein, during cementogenesis. Connect Tissue Res. 1995;33:1–7. doi: 10.3109/03008209509016974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKee M, Zalzal S, Nanci A. Extracellular matrix in tooth cementum and mantle dentin: localization of osteopontin and other noncollagenous proteins, plasma proteins, and glycoconjugates by electron microscopy. Anat Rec. 1996;245:293–312. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199606)245:2<293::AID-AR13>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D’Errico J, MacNeil R, Takata T, Berry J, Strayhorn C, Somerman M. Expression of bone associated markers by tooth root lining cells, in situ and in vitro. Bone. 1997;20:117–126. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(96)00348-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ye L, Zhang S, Ke H, Bonewald LF, Feng JQ. Periodontal breakdown in the Dmp1 null mouse model of hypophosphatemic rickets. J Dent Res. 2008;87:624–629. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berendsen A, Smit T, Schoenmaker T, et al. Inorganic phosphate stimulates DMP1 expression in human periodontal ligament fibroblasts embedded in three-dimensional collagen gels. Cells Tissues Organs. 2010;192:116–124. doi: 10.1159/000289585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleisch H, Bisaz S. Mechanism of calcification: inhibitory role of pyrophosphate. Nature. 1962;195:911. doi: 10.1038/195911a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whyte M. Hypophosphatasia and the role of alkaline phosphatase in skeletal mineralization. Endocr Rev. 1994;15:439–461. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-4-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mornet E. Hypophosphatasia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:40. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruckner RJ, Rickles NH, Porter DR. Hypophosphatasia with premature shedding of teeth and aplasia of cementum. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1962;15:1351–1369. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(62)90356-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu JC, Plaetke R, Mornet E, et al. Characterization of a family with dominant hypophosphatasia. European journal of oral sciences. 2000;108:189–194. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2000.108003189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beumer J, 3rd, Trowbridge HO, Silverman S, Jr, Eisenberg E. Childhood hypophosphatasia and the premature loss of teeth. A clinical and laboratory study of seven cases. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1973;35:631–640. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(73)90028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei KW, Xuan K, Liu YL, et al. Clinical, pathological and genetic evaluations of Chinese patients with autosomal-dominant hypophosphatasia. Arch Oral Biol. 2010;55:1017–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harmey D, Johnson K, Zelken J, et al. Elevated skeletal osteopontin levels contribute to the hypophosphatasia phenotype in Akp2(−/−) mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1377–1386. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gurley K, Chen H, Guenther C, et al. Mineral formation in joints caused by complete or joint-specific loss of ANK function. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1238–1247. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho AM, Johnson MD, Kingsley DM. Role of the mouse ank gene in control of tissue calcification and arthritis. Science. 2000;289:265–270. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fong H, Foster BL, Sarikaya M, Somerman MJ. Structure and mechanical properties of Ank/Ank mutant mouse dental tissues--an animal model for studying periodontal regeneration. Arch Oral Biol. 2009;54:570–576. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bosshardt D, Schroeder H. Cementogenesis reviewed: a comparison between human premolars and rodent molars. Anat Rec. 1996;245:267–292. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199606)245:2<267::AID-AR12>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaipatur N, Murshed M, McKee M. Matrix Gla protein inhibition of tooth mineralization. J Dent Res. 2008;87:839–844. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beertsen W, Niehof A, Everts V. Effects of 1-hydroxyethylidene-1, 1-bisphosphonate (HEBP) on the formation of dentin and the periodontal attachment apparatus in the mouse. Am J Anat. 1985;174:83–103. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001740107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jayawardena C, Takahashi N, Watanabae E, Takano Y. On the origin of intrinsic matrix of acellular extrinsic fiber cementum: studies on growing cementum pearls of normal and bisphosphonate-affected guinea pig molars. Eur J Oral Sci. 2002;110:261–269. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.21239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taillandier A, Lia-Baldini A, Mouchard M, et al. Twelve novel mutations in the tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase gene (ALPL) in patients with various forms of hypophosphatasia. Hum Mutat. 2001;18:83–84. doi: 10.1002/humu.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whyte MP, Vrabel LA, Schwartz TD. Alkaline phosphatase deficiency in cultured skin fibroblasts from patients with hypophosphatasia: comparison of the infantile, childhood, and adult forms. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1983;57:831–837. doi: 10.1210/jcem-57-4-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whyte MP, Vrabel LA. Infantile hypophosphatasia fibroblasts proliferate normally in culture: evidence against a role for alkaline phosphatase (tissue nonspecific isoenzyme) in the regulation of cell growth and differentiation. Calcified tissue international. 1987;40:1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02555720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fedde KN, Whyte MP. Alkaline phosphatase (tissue-nonspecific isoenzyme) is a phosphoethanolamine and pyridoxal-5′-phosphate ectophosphatase: normal and hypophosphatasia fibroblast study. American journal of human genetics. 1990;47:767–775. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wennberg C, Hessle L, Lundberg P, et al. Functional characterization of osteoblasts and osteoclasts from alkaline phosphatase knockout mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:1879–1888. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.10.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Macneil R, Sheng N, Strayhorn C, Fisher L, Somerman M. Bone sialoprotein is localized to the root surface during cementogenesis. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9:1597–1606. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650091013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodrigues TL, Nagatomo KJ, Foster BL, Nociti FH, Somerman MJ. Modulation of phosphate/pyrophosphate metabolism to regenerate the periodontium. A novel in vivo approach. J Periodontol. 2011 doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.110103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]