Abstract

Background

Despite implementation of universal infant hepatitis B (HB) vaccination, mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of hepatitis B virus (HBV) still occurs. Limited data are available on the residual MTCT of HBV in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-HBV co-infected women.

Objectives

We assessed the prevalence of HBV infection among HIV-infected pregnant women and the rate of residual MTCT of HBV from HIV-HBV co-infected women and analyzed the viral determinants in mothers and their HBV-infected children.

Study design

HIV-1 infected pregnant women enrolled in two nationwide perinatal HIV prevention trials in Thailand were screened for HB surface antigen (HBsAg) and tested for HBeAg and HBV DNA load. Infants born to HBsAg-positive women had HBsAg and HBV DNA tested at 4–6 months. HBV diversity within each HBV-infected mother-infant pair was analyzed by direct sequencing of amplified HBsAg-encoding gene and cloning of amplified products.

Results

Among 3,312 HIV-1 infected pregnant women, 245 (7.4%) were HBsAg-positive, of whom 125 were HBeAg-positive. Of 230 evaluable infants born to HBsAg-positive women, 11 (4.8%) were found HBsAg and HBV DNA positive at 4–6 months; 8 were born to HBeAg-positive mothers. HBV genetic analysis was performed in 9 mother-infant pairs and showed that 5 infants were infected with maternal HBV variants harboring mutations within the HBsAg “a” determinant, and four were infected with wild-type HBV present in highly viremic mothers.

Conclusions

HBV-MTCT still occurs when women have high HBV DNA load and/or are infected with HBV variants. Additional interventions targeting highly viremic women are thus needed to reduce further HBV-MTCT.

Keywords: HBs antigen variants, Hepatitis B vaccine failure, HIV pregnant women, mother-to-child transmission, Thailand

1. Background

One-third of the world population has been infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and about 350 million people have developed chronic infection.1 In highly endemic regions such as East-Asia and Pacific, prevalence of HBsAg is ≥8%2 and mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HBV remains a major source of chronic infection.3 About 90% of infants infected during the first year of life and 30% to 50% of children infected between 1–5 years of age develop a chronic infection with its attendant risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma during adulthood.4

In countries where infant hepatitis B (HB) vaccine has been integrated into national expanded program on immunization (EPI), a very significant decrease of HBV infection in children has been observed.5, 6 However, full eradication of HBV has not yet been achieved and HBV infection still occurs in children despite EPI. Many HBV endemic countries in Africa and Asia have a significant HIV-infected population but limited data are available on the prevalence of HBV-MTCT among HIV-HBV co-infected women in the context of EPI.

HBV exhibits a mutation rate of about 1 nucleotide per 10,000 bases per infection year, 10-fold higher than most other DNA viruses.7 It has been suggested that viral variants harboring mutations in critical amino acids within the “a” region (amino acid position 121 to 149) of the surface protein may escape vaccine-elicited anti-HBs antibodies or hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIg) and may be transmitted from mother-to-infant.8 MTCT of HBV may involve variants that are present at low concentration in maternal blood and selected during the transmission process.9 Those minor HBV variants can be identified by sequencing multiple virus clones.

Thailand is endemic for HBV infection with 7–8% prevalence of HBsAg carriers. Universal HB vaccination of newborns was introduced in 1992 into the national EPI and has reduced the pediatric HBsAg positivity rate from 3.4% to 0.7% in 2006, irrespective of maternal HBsAg status.6 Few data are available on the residual MTCT of HBV in HIV-HBV co-infected women.

2. Objectives

We aimed to assess the prevalence of chronic HBV infection among a large number of HIV-infected pregnant women in Thailand and to determine the prevalence of HBV-MTCT in infants in the era of EPI. We performed a clonal analysis of HBV quasispecies present in HBV-infected mothers and their HBV-infected infants to identify viral determinants potentially associated with HB vaccine failure,

3.Study design

3.1. Patients

This study included HIV-infected pregnant women and their infants who participated in two Perinatal HIV Prevention Trials in Thailand (PHPT-1/NCT0038623010 and PHPT-2/NCT0039868411), assessing, respectively, the efficacy of different durations of zidovudine (ZDV) or single-dose nevirapine plus zidovudine regimens, to prevent perinatal transmission of HIV. Breast-feeding was not recommended in these two trials. Blood samples were collected from women during pregnancy and from children at birth, 6 weeks, 4, 6 and 12 months of age.

3.2. HBV Markers and HBV DNA quantification

Mothers were screened for HBsAg and, if positive, tested for HBeAg. Infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers were tested for HBsAg and/or HBV DNA. Infants were infected by HBV if HBsAg was found positive or HBV DNA detected at 6 weeks to 6 months of age. HBsAg and HBeAg were tested using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ETI-MAK and ETI-EBK, DiaSorin) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. HBV DNA quantification was performed in HBsAg positive-women and HBV-infected infants using the Cobas Amplicor HBV Monitor test (Roche Diagnostics, lower limit of detection: 1.78 log10 IU/mL) or Abbott real-time HBV DNA™ assay (Abbott laboratories, lower limit of detection: 1.18 log10 IU/mL).

3.3. HBV DNA amplification and direct sequencing

HBV DNA was extracted from 200 µl of plasma using QIAamp DNA mini kit (QIAgen). Ten µL of extract were amplified as described by Villeneuve et al. with slight modifications.12 The amplicons were sequenced using the pol3M and pol4M primers, and the BigDye Terminator Mix V. 1.1 (Applied Biosystems). Sequences were aligned using the Bioedit software. Surface (S) and polymerase (Pol) genes were then analyzed for polymorphisms and mutations known to be associated with vaccine escape through comparison with wild-type reference sequences of similar genotype retrieved from GenBank (see appendix).

3.4. HBV cloning and sequencing

The second round PCR products were cloned with TA Cloning Kit (Promega) using standard cloning technique. At least 24 white colonies were picked and grown in LB medium with ampicillin. The presence of the insert was confirmed using EcoRI enzyme digestion. The recombinant plasmid DNA was isolated with the NucleoSpin Plasmid kit. Sequencing reactions were performed and analyzed as mentioned above.

3.5. HBV genotyping and serotyping

HBV genotype was identified by phylogenetic analysis of S and Pol gene sequences using clustalW software. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using neighbor-joining method and genetic distances calculated using the Kimura two-parameter method and 1000 simulations bootstrap with the MEGA software.13 HBV serotype was inferred from amino acids residues at codons 122, 126, 127, 160, 168, 177 and 178 of the S gene.14, 15

3.6. Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of study population, including maternal age at enrollment, mother’s body weight, region of origin, alanine transaminase (ALT) level, CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells count, HIV RNA load, and positive hepatitis C virus serology are described using number and percentage for categorical data and median with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous data. All data analyses were performed using STATA™ version 10.1 software (Statacorp, College Station, TX).

4. Results

4.1. Patient characteristics

A total of 3,345 HIV-infected pregnant women had at least one blood sample. Their demographic and laboratory data are presented in Table 1. Their median age was 25.5 (IQR: 22.4–29.1) years. Median CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell count were 368 (IQR: 241–520) and 904 (IQR: 680–1,186) cells/µL, respectively, median ALT was 15 (IQR: 10–22) and median HIV RNA was 3.99 (IQR: 3.36–4.58) log10 copies/mL. Four percent of women had antibodies against hepatitis C virus.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study population

| Characteristics | N | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Median age at enrollment; years old (IQR) | 3,345 | 25.5 (22.4–29.1) |

| Median CD4 T-cell count; cells/µL (IQR) | 3,265 | 368 (241–520) |

| Median CD8 T-cell count; cells/µL (IQR) | 2,926 | 904 (680–1186) |

| Median ALT; IU/L (IQR) | 3,277 | 15 (10–22) |

| Median HIV viral load; log10 copies/mL (IQR) | 3,319 | 3.99 (3.36–4.58) |

| anti-HCV positive | 3,319 | 122 (3.7) |

4.2. Prevalence of HBsAg carriage in HIV-1 infected pregnant women and rate of mother-to-child transmission of HBV

Of 3,312 women with clearly identified HBV status, 245 (7.4%; 95% confidence interval (CI), 6.5–8.3) were HBsAg positive and had a median HBV DNA load of 4.37 (IQR: 1.83–7.63) log10 IU/mL. One hundred and twenty five (51%) of them were HBeAg positive. Of 125 HBeAg positive mothers, 121 had HBV DNA load available; median was 7.57 log10 IU/mL (IQR: 6.98–7.92). For 120 HBeAg negative mothers, 116 had HBV DNA load available with the median of 1.88 log10 IU/mL (IQR: undetectable–2.63), Figure 1. Assessment of HBV-MTCT was possible in 230 infants born to HBsAg-positive women. Eleven infants (4.8%; 95%CI, 2.4–8.4) were found infected with HBV; 8 (of 119) infants were born to HBeAg-positive mothers with HBV DNA >6 log10 IU/mL (6.7%; 95%CI, 2.9–12.8) and 3 (of 111) infants were born to HBeAg-negative mothers (2.7%; 95%CI, 0.6–7.7) (Figure 2). A birth sample was available for 9 of the 11 infected infants. Four tested positive for HBV DNA and all 4 were born to HBeAg-positive mothers (Table 2). These 11 HBV-infected infants were HIV-negative.

Figure 1.

Association between the level of plasma HBV DNA and HBeAg status in HBV-HIV co-infected mothers.

Figure 2.

Overall study diagram

Table 2.

HBV DNA load and infant HBV prophylaxis among 11 HBV transmitting mother-child pairs.

| Maternal HBV load (log10 IU/mL) |

Infant prophylaxis | Infant HBV load (log10 IU/mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pair | Maternal HBeAg |

Before delivery | Vaccination (months) |

HBIg | Birth – 10 days | 4 months | 6 months |

| 0387 | + | 7.84 | 0, 1, 5, 6 | Yes | 4.37 | 8.18 | 8.93 |

| 0625 | + | 7.92 | 0, 2, 6 | Yes | 2.60 | 5.51 | 7.90 |

| 1550 | + | 8.04 | 0, 1, 6 | No | 1.58 | NA | NA |

| 0022 | + | 7.83 | 2, 4 | No | 2.48 | NA | NA |

| 0657 | + | 7.85 | 0, 2, 6 | No | Und | 7.61 | 8.76 |

| 1395 | + | 8.24 | 0, 1, 6, 12 | No | Und | NA | NA |

| 9149 | + | 3.61 | 0, 1, 6, 8 | No | Und | 2.91 | Und |

| 0394 | − | 6.51 | 0, 1, 6 | No | Und | 3.08 | 1.48 |

| 0135 | − | 2.28 | Unknown* | Unknown | Und | 5.63 | NA |

| 0349 | + | 6.18 | 0, 1, 6 | No | 2.52 (at 6 wk) | NA | NA |

| 0175 | − | <1.58 | Unknown | Unknown | 2.95 (at 6 wk) | NA | NA |

Und: below detectable level; NA: not available due to insufficiency of plasma samples

No record of vaccination, however this child was born in a provincial hospital of the northeastern region of Thailand where the standard of care was to provide at least HB vaccine to all infants born to positive HBsAg mothers.

4.3. Genetic analysis of HBV by direct sequencing

Amplification and sequencing of HBV S gene were successful for only 9 of 11 mother-infant pairs. Failure of amplification for 2 mother-infant pairs was due to low viral load and limited volume of sample. Results of direct sequencing are summarized in table 3. Few mutations other than the known vaccine escape mutations were detected.

Table 3.

Pattern of HBV transmission, genotype, and mutations observed by direct sequencing of S gene among 9 HBV transmitting mother-child pairs.

| Pairs | Pattern | Maternal HBeAg |

HBV load (log10 IU/mL) |

HBV genotype |

mutations in maternal virus |

mutations in infant virus | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth – 10 days |

4 months | 6 months | ||||||

| 0387 | 1 | + | 7.84 | C | None | None | None | None |

| 0625 | 1 | + | 7.92 | C | None | None | sI126I/T | sI126T |

| 0657 | 1 | + | 7.85 | C | None | NA | None | None |

| 0394 | 1 | − | 6.51 | B | None | NA | None | NA |

| 0022 | 2 | + | 7.83 | C | None | NA | sK122R | sK122R |

| 1395 | 2 | + | 8.24 | C | None | NA | sK122R | sK122R |

| 1550 | 3 | + | 8.04 | C | sI126T | NA | sI126T | sI126T |

| 0135 | 3 | − | 2.28 | C | sI126I/M, sP127A/S | NA | sI126M, sP127S | NA |

| 9149 | 3 | + | 3.61 | B | sT131N, sM133M/T, sT140I, sS204S/R | NA | sT131N, sM133T, sT140I, sS204R | NA |

NA: not available due to undetectable HBV DNA level or unsuccessful amplification of region of interest

Three patterns of transmitted virus could be distinguished. In the first pattern, 4 infants were infected with maternal wild-type HBV (0387, 0394, 0625 and 0657). All were born to mothers with high level of HBV DNA (>6 log10 IU/mL) and HBV DNA was positive at or around birth. In one infant (0625), wild-type HBV was replaced at 4 months of age by a variant harboring a threonine mutation at amino acid position 126 (sI126T). In the second pattern, 2 infants (0022 and 1395) were infected with a HBV sK122R variant (lysine substitution by arginine in position 122) that was not detected in their mothers. In the third pattern, 3 infants (1550, 0135, 9149) were infected with variants already present in their mothers; sI126T, sI126M/P127S, and sT131N/M133T/T140I/S204R (Table 3). Phylogenetic analysis showed that 7 pairs were infected with HBV genotype C and 2 pairs were infected with genotype B (data not shown).

4.4. Analysis of maternal and infant HBV quasispecies

HBV quasispecies present in mothers and infants are presented in figure 3. For 3 of 4 infants who were HBV DNA positive at birth, analysis of quasispecies was not possible in the birth sample. Clonal sequence analysis generally confirmed the three patterns of virus transmission but, because of its greater sensitivity to minor species, it demonstrated some differences. In the first pattern, wild type HBV was predominant in 4 mothers and their infants (Figure 3A, 3B, 3C, 3D). Interestingly, in one infant (0387, Figure 3A), the known vaccine-escape mutant sG145R was present in 2 of 15 maternal clones but in none of the infant clones. For the pair 0625, the sI126T variant was identified in 2 of 20 maternal clones and became predominant in infant’s samples at 4 and 6 months, accounting for 41% and 76% of quasispecies, respectively (Figure 3B).

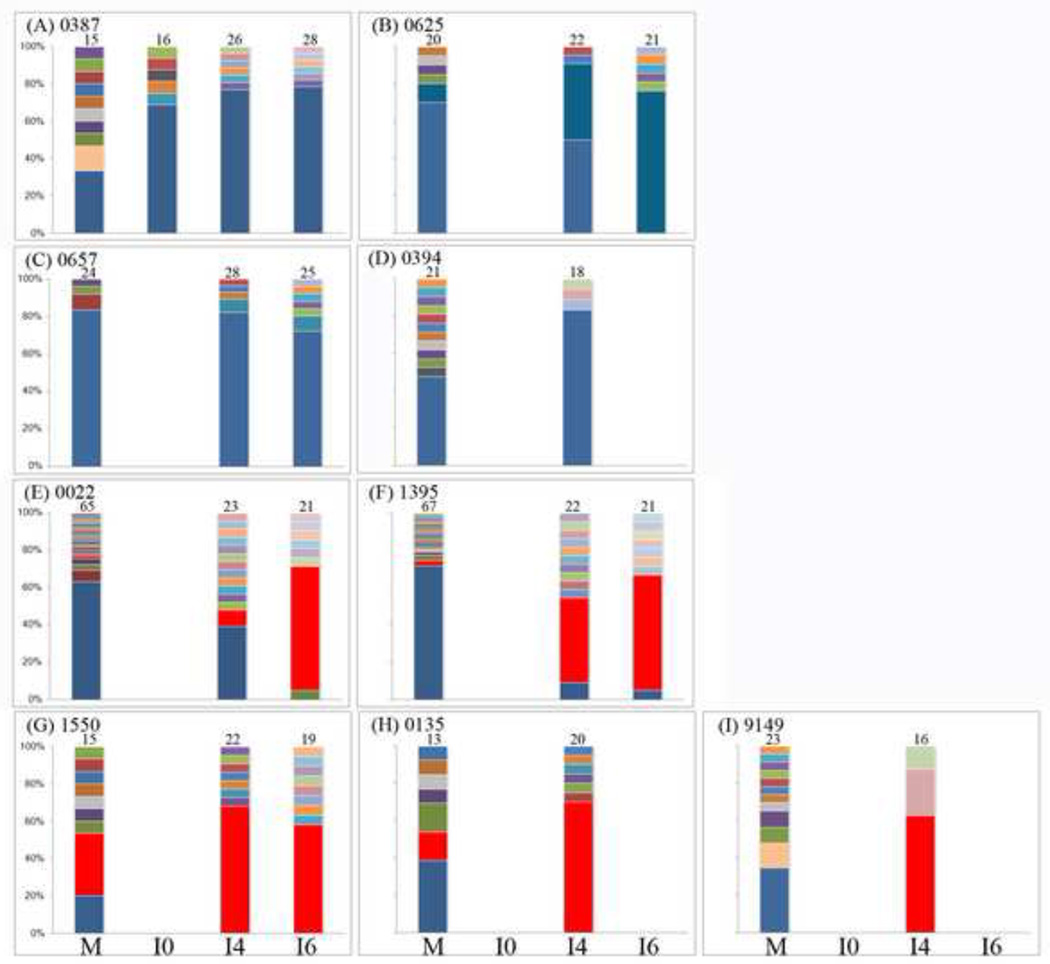

Figure 3.

Evolution of HBV quasispecies in 9 transmitting mother-child pairs. M indicates the maternal sample. I0, I4 and I6 indicate infant samples at birth, 4 and 6 months, respectively. Figures directly above each bar indicate the number of clones analyzed. The patient identifier is given beside the panel label. Wild type is indicated in blue, variants are indicated by other colors. Three possible patterns of HBV mother-to-child transmission were observed:1) Transmission of wild-type variants from mothers with high level of HBV DNA (A, B, C, D), 2) Transmission of maternal minor variants to their infants (E, F), and 3) Transmission of HBV variants already existing in mothers (G, H, I).

In the second pattern, a maternal minor variant (i.e. representing <20% of viral population) was transmitted and became predominant over time in infants e.g. the sK122R variant present in 1 of 65 and 2 of 67 maternal clones of 0022 and 1395, respectively (Figure 3E, 2F). Prediction of HBV serotype based on amino acids residues present at specific codons of the S gene showed that the substitution of lysine by arginine at position 122 led to the change of serotype adrq+ in the mothers to ayr in their infants.

In the third pattern, maternal HBV variants accounting for 20% or more of all maternal quasispecies were detected in 2 infants. For the pair 1550 (Figure 3G), HBV sI126T variant was always predominant in both mother and infant. For the pair 0135 (Figure 3H), the variant sI126M/P127S was detected in 23% (3 of 13) of maternal clones and in 40% (8 of 20) of clones in the 4-month infant sample. In the pair 9149, the predominant quasispecies found in the mother was the multiple variant sK122R/T131N/M133T/T140I/S204R while it was sT131N/M133T/T140I/S204R in the infant (10 of 16 clones) (Figure 3I).

5. Discussion

We observed a perinatal HBV transmission rate of 4.8%. This rate increased to 6.7% among HBeAg-positive mothers. Both rates were not different from that among infants aged 6–11 months, born to HIV negative HBsAg-positive mothers and enrolled in the Taiwanese universal immunization program.5

Seven infants were born to mothers with very high HBV DNA level of whom four were found infected at birth; two of these new born infants had received early injection of HBIg and vaccine. Usually, in utero HBV infection is considered as a very rare event as compared to infection during the perinatal period16 but can occur despite passive and/or active immunization of newborns at birth17 when mothers have high HBV DNA level.18–20 Four infants received birth-dose HB vaccine but not HBIg and may have been infected through exposure to blood or contaminated fluids with high viral load at or around birth.21 In the absence of HBIg, infection at birth may have developed before vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies are fully produced. Two infants were born to mothers with low HBV DNA load and had undetectable HBV DNA at birth. They were found HBV DNA positive at month 4 showing that transmission could occur beyond the neonatal period via close contact between mother and child.

An extensive analysis of quasispecies in mothers and infants identified new HBV variants harboring mutation within the HBsAg “a” determinant, a main target of neutralizing antibodies. Some of these HBsAg mutations may have resulted in structural change and escape from neutralizing antibodies. The sK122R variant was predominant in 2 infants while it represented a minor quasispecies in their mothers. This amino acid substitution corresponded to a change from serotype adrq+ to ayr suggesting that it was selected under the immune pressure generated by the post-exposure prophylaxis with HB vaccine and/or HBIg. Such change had not been observed in a previous study conducted in Thailand using direct sequencing.22 Its impact on HBV antigenicity and vaccine escape is unknown. However, the change of predicted serotype may have favored the virus to escape from vaccine-induced neutralizing antibodies. It should be noted that amino acid residues at position 120 to 123 play a major role in HBsAg antigenicity, an example of this being the mutation K122I that abolishes the reactivity of HBsAg to most of immunoassays.23 Five other mutations that locate in the “a” determinant of HBsAg were identified in other infants; i.e. sI126T/M, sP127S, sT131N, sM133T, and sT140I. The emergence of sI126T variant was observed in vaccinated infants born to chronically HBV infected mothers in India24, Korea25 and Taiwan26. Prediction of HBsAg 3D structure indicates that amino acid substitution at position 126 would result in the largest structural changes in the HBsAg27, potentially permitting immune escape. The sP127S mutation was detected in one infant born to an Italian mother infected by a wild-type HBsAg despite immune-prophylaxis with HB vaccine and HBIg given at birth.28 The sM133T mutation was also reported in a vaccinated child in Thailand.29 Although one woman had minor HBV quasispecies harboring the well-known sG145R vaccine escape mutation, she only transmitted wild type virus. One possible explanation is that the HB vaccines administered were able to prevent infection by sG145R mutant as shown in a chimpanzee model.30

Our study showed that HB vaccine failure occurred in infants born to HIV-HBV co-infected mothers at a rate similar to those in HIV-uninfected mothers suggesting that maternal HIV infection did not hamper hepatitis B immunization of newborns within an EPI program.31 HBsAg mutants emerging during vaccine failures and spreading to the general population has been a constant concern since the implementation of nationwide HB vaccination programs. A long term survey of the universal infant immunization program in Taiwan has shown that mutants within the “a” determinant were associated with few failures.32 However, the long-term impact of such variants on universal immunization program may require continuous survey of HBV infection in children. Full eradication of HBV transmission in highly viremic women may be achieved using additional interventions such as providing anti-HBV active drug(s) during the third trimester of pregnancy to decrease HBV DNA load of either wild-type or variants virus.33–35

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to all women and children who participated in this study and the medical teams involved for their active and reliable commitment. We thank Kenneth McIntosh (Harvard School of Public Health, MA) and Celine Gallot (Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France) for their review and useful comments, Francis Barin (Université François-Rabelais de Tours, France) for his kind suggestion, Duangthida Saeng-ai, Paporn Mongkolwat, and Ampika Kaewbundit (IRD-UMI174/PHPT) for technical assistance with laboratory assays, and the IRD-UMI174/PHPT team for the help provided during this work.

Funding

This study was supported by Agence Nationale de Recherchessur le Sida et les Hépatites Virales (grant number: ANRS 12179), National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Research Collaboration Award (NIH FIRCA R03 TW01346), National Institutes of Health (grant numbers: 5 R01 HD 33326 and 5 R01 HD 39615), the Franco-Thai cooperation program in Higher Education and Research, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Thailand International Development Cooperation Agency (TICA), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Thailand, the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), France. W.K. received scholarships from IRD, the Franco-Thai cooperation program in Higher Education and Research, the Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University and the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Abbreviations

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- EPI

Expanded Program on Immunization

- HB

hepatitis B

- HBeAg

the “e” antigen of the hepatitis B virus

- HBIg

Hepatitis B Immune globulin

- HBsAg

the surface antigen of the hepatitis B virus

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- IQR

interquartile range

- MTCT

mother-to-child transmission

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- 95%CI

95% confidence interval

Appendix

Reference sequences used in this study were obtained from GenBank database: X70185, V00866, S50225, X51970, M57663 (genotype A); D00331, M54923, D00329, D00330 (genotype B); M38636, X14193, M12906, D12980, D00630, L08805, X52939, X01587, M38454, V00867, X75665, X75656 (genotype C); M32138, X59795, X02496, X72702, X65257, X65258, X65259, X68292 (genotype D); X75664, X75657 (genotype E); X75663, X75658 (genotype F); AF160501, AB064310, AF405706, AB056513 (genotype G).

The Program for HIV Prevention and Treatment (PHPT)-1 and PHPT-2 study groups

The following sites and principal investigators participated in the Perinatal HIV Prevention Trials, Thailand (the number of women enrolled in the 2 clinical trials at each hospital is given in parentheses):

Rayong Hospital (338): W. Suwankornsakul, S. Weerawatgoompa-Lorenz, S. Ariyadej, W. Karnchanamayul; Chiangrai Prachanukroh Hospital (210): P. Wattanaporn, J. Achalapong, R. Hansudewechakul; Prapokklao Hospital (189): C. Veerakul, P. Yuthavisuthi, C. Ngampiyaskul; Banglamung Hospital (155): J. Ithisuknanth, S. Sirithadthamrong; Hat Yai Hospital (148): J. Lawantrakul, P. Wannaro, S. Lamlertkittikul, S. Deawpanich-Sanguanchua, B. Warachit; Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital (145): V. Suraseranivong, S. Prommas, P. Layangool, K. Kengsakul; Chonburi Hospital (142): N. Chotivanich, S. Hongsiriwon; Phayao Provincial Hospital (127): J. Hemvuttiphan, S. Bhakeecheep, U. Sriminipun, S. Techakulviroj; Mae Sai Hospital (111): S. Nanta, T. Meephian; SomdejPrapinklao Hospital (111): S. Suphanich, N. Tawornpanit, N. Kamonpakorn; Pranangklao Hospital (100): S. Pipatnakulchai, S. Wanwaisart, S. Watanayothin; Klaeng Hospital (97): S. Techapalokul, S. Hotrawarikarn; Chiang Kham Hospital (96): C. Putiyanun, P. Jittamala; Bhuddasothorn Hospital (96): A. Kanjanasing, R. Kaewsonthi, R. Kwanchaipanich; Samutprakarn Hospital (94): P. Sabsanong, C. Sriwacharakarn; Nakhonpathom Hospital (93): V. Chalermpolprapa, S. Bunjongpak; Samutsakhon Hospital (90): T. Sukhumanant, P. Thanasiri; Mae Chan Hospital (88): S. Buranabanjasatean; Queen Sirikit Hospital (88): T. Hinjiranandana, C. Niyomrat, P. Waithayakul; Buddhachinaraj Hospital (81): W. Wannapira, W. Ardong; Health Promotion Hospital Regional Center I (72): W. Laphikanont, S. Sirinontakan; Phan Hospital (69): S. Jungpichanvanich; Lamphun Hospital (68): W. Matanasarawut, K. Pagdi, P. Wannarit, R. Somsamai, S. Khunpradit; Nakornping Hospital (65): P. Leelanitkul, V. Gomuthbutra, S. Kanjanavanit, P. Krittigamas; Health Promotion Center Region 10 (64): S. Sangsawang, W. Pattanaporn, W. Jitphiankha, V. Sittipiyasakul; NopparatRajathanee Hospital (59): T. Chanpoo, S. Surawongsin, S. Ruangsirinusorn, P. Suntarattiwong; Kalasin Hospital (42): B. Suwannachat, S. Srirojana; Bamrasnaradura Hospital (41): P. Tunthanathip, S. Sirikwin; Ratchaburi Hospital (41): T. Chonladarat, O. Bamroongshawkaseme, P. Malitong; Regional Health Promotion Centre 6 (39): N. Winiyakul, S. Hanpinitsak, N. Pramukkul; KhonKaen Hospital (38): J. Ratanakosol, W. Chandrakachorn; NongKhai Hospital (34): N. Puarattanaaroonkorn, S. Potchalongsin; Phaholpolpayuhasaena Hospital (34): Y. Srivarasat, P. Attavinijtrakarn; Banchang Hospital (33): S. Tragarngool, N. Sangwannakul; Mahasarakam Hospital (32): S. Nakhapongse, W. Worachet, P. Sitsirat, S. Tonmat, K. Kovitanggoon; Roi-et Hospital (32): W. Atthakorn; Srinagarind Hospital (30): C. Sakondhavat, R. Sripanidkulchai; Prajaksilapakom Army Hospital (19): W. Srichandraphan; Kranuan Crown Prince Hospital (18): R. Thongdej, S. Benchakhanta; Chiang Khong Royal Crown Prince Hospital (15): C. Taiyaitiang, A. Niramitsantiphong; Phayamengrai Hospital (12): P. Tantiwattanakul; McCormick Hospital (11): C. Tangchaitrong, A. Junjam.

Footnotes

Competing interests

None of the authors report any potential conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethical committee of Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Thailand. The relevant Judgement’s reference number is 041E/52.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) Hepatitis B: Fact sheet No.204. [Revised July 2012];

- 2.Heathcote EJ. Demography and presentation of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Am J Med. 2008;121:S3–S11. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liaw YF, Leung N, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, Gane E, Han KH, et al. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2008 update. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:263–283. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9080-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kew MC. Epidemiology of chronic hepatitis B virus infection, hepatocellular carcinoma, and hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2010;58:273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen HL, Lin LH, Hu FC, Lee JT, Lin WT, Yang YJ, et al. Effects of maternal screening and universal immunization to prevent mother-to-infant transmission of HBV. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:773–781. e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poovorawan Y, Theamboonlers A, Vimol ket T, Sinlaparatsamee S, Chaiear K, Siraprapasiri T, et al. Impact of hepatitis B immunisation as part of the EPI. Vaccine. 2000;19:943–949. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunt CM, McGill JM, Allen MI, Condreay LD. Clinical relevance of hepatitis B viral mutations. Hepatology. 2000;31:1037–1044. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.6709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oon CJ, Lim GK, Ye Z, Goh KT, Tan KL, Yo SL, et al. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B virus vaccine variants in Singapore. Vaccine. 1995;13:699–702. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)00080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komatsu H, Inui A, Sogo T, Konishi Y, Tateno A, Fujisawa T. Hepatitis B surface gene 145 mutant as a minor population in hepatitis B virus carriers. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:22. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lallemant M, Jourdain G, Le Coeur S, Kim S, Koetsawang S, Comeau AM, et al. A trial of shortened zidovudine regimens to prevent mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Perinatal HIV Prevention Trial (Thailand) Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:982–991. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010053431401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lallemant M, Jourdain G, Le Coeur S, Mary JY, Ngo-Giang-Huong N, Koetsawang S, et al. Single-dose perinatal nevirapine plus standard zidovudine to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Thailand. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:217–228. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villeneuve JP, Durantel D, Durantel S, Westland C, Xiong S, Brosgart CL, et al. Selection of a hepatitis B virus strain resistant to adefovir in a liver transplantation patient. J Hepatol. 2003;39:1085–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kay A, Zoulim F. Hepatitis B virus genetic variability and evolution. Virus Res. 2007;127:164–176. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Purdy MA, Talekar G, Swenson P, Araujo A, Fields H. A new algorithm for deduction of hepatitis B surface antigen subtype determinants from the amino acid sequence. Intervirology. 2007;50:45–51. doi: 10.1159/000096312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goudeau A, Yvonnet B, Lesage G, Barin F, Denis F, Coursaget P, et al. Lack of anti-HBc IgM in neonates with HBsAg carrier mothers argues against transplacental transmission of hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 1983;2:1103–1104. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90625-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shao ZJ, Zhang L, Xu JQ, Xu DZ, Men K, Zhang JX, et al. Mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus: a Chinese experience. J Med Virol. 2011;83:791–795. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song YM, Sung J, Yang S, Choe YH, Chang YS, Park WS. Factors associated with immunoprophylaxis failure against vertical transmission of hepatitis B virus. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:813–818. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zou H, Chen Y, Duan Z, Zhang H. Protective effect of hepatitis B vaccine combined with two-dose hepatitis B immunoglobulin on infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan CQ, Duan ZP, Bhamidimarri KR, Zou HB, Liang XF, Li J, et al. An algorithm for risk assessment and intervention of mother to child transmission of hepatitis B virus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:452–459. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee C, Gong Y, Brok J, Boxall EH, Gluud C. Effect of hepatitis B immunisation in newborn infants of mothers positive for hepatitis B surface antigen: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2006;332:328–336. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38719.435833.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sa-Nguanmoo P, Tangkijvanich P, Tharmaphornpilas P, Rasdjarmrearnsook AO, Plianpanich S, Thawornsuk N, et al. Molecular analysis of hepatitis B virus associated with vaccine failure in infants and mothers: a case-control study in Thailand. J Med Virol. 2012;84:1177–1185. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian Y, Xu Y, Zhang Z, Meng Z, Qin L, Lu M, et al. The amino Acid residues at positions 120 to 123 are crucial for the antigenicity of hepatitis B surface antigen. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:2971–2978. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00508-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Velu V, Saravanan S, Nandakumar S, Dhevahi E, Shankar EM, Murugavel KG, et al. Transmission of "a" determinant variants of hepatitis B virus in immunized babies born to HBsAg carrier mothers. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2008;61:73–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee KM, Kim YS, Ko YY, Yoo BM, Lee KJ, Kim JH, et al. Emergence of vaccine-induced escape mutant of hepatitis B virus with multiple surface gene mutations in a Korean child. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16:359–362. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.3.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng H, Su H, Wang S, Shao Z, Men K, Li M, et al. Association between genomic heterogeneity of hepatitis B virus and intrauterine infection. Virology. 2009;387:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren F, Tsubota A, Hirokawa T, Kumada H, Yang Z, Tanaka H. A unique amino acid substitution, T126I, in human genotype C of hepatitis B virus S gene and its possible influence on antigenic structural change. Gene. 2006;383:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mele A, Tancredi F, Romano L, Giuseppone A, Colucci M, Sangiuolo A, et al. Effectiveness of hepatitis B vaccination in babies born to hepatitis B surface antigen-positive mothers in Italy. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:905–908. doi: 10.1086/323396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Theamboonlers A, Chongsrisawat V, Jantaradsamee P, Poovorawan Y. Variants within the "a" determinant of HBs gene in children and adolescents with and without hepatitis B vaccination as part of Thailand's Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) Tohoku J Exp Med. 2001;193:197–205. doi: 10.1620/tjem.193.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ogata N, Cote PJ, Zanetti AR, Miller RH, Shapiro M, Gerin J, et al. Licensed recombinant hepatitis B vaccines protect chimpanzees against infection with the prototype surface gene mutant of hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 1999;30:779–786. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones CE, Naidoo S, De Beer C, Esser M, Kampmann B, Hesseling AC. Maternal HIV infection and antibody responses against vaccine-preventable diseases in uninfected infants. Jama. 2011;305:576–584. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsu HY, Chang MH, Ni YH, Chiang CL, Chen HL, Wu JF, et al. No increase in prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen mutant in a population of children and adolescents who were fully covered by universal infant immunization. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1192–1200. doi: 10.1086/651378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ilboudo D, Simpore J, Ouermi D, Bisseye C, Sagna T, Odolini S, et al. Towards the complete eradication of mother-to-child HIV/HBV coinfection at Saint Camille Medical Centre in Burkina Faso, Africa. Braz J Infect Dis. 2010;14:219–224. doi: 10.1016/s1413-8670(10)70047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu WM, Cui YT, Wang L, Yang H, Liang ZQ, Li XM, et al. Lamivudine in late pregnancy to prevent perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus infection: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:94–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maternal Antiviral Prophylaxis to Prevent Perinatal Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus in Thailand (iTAP) Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); 2000. [cited 2013 Apr 14]. Institut de Recherche pour le Développement; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Gilead Sciences. ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01745822?term=NCT01745822&rank=1. NLM Identifier: NCT01745822. [Google Scholar]