Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive respiratory disease with an increasing prevalence worldwide. Its potential consequences, including reduced function and reduced social participation, are likely to be associated with decreased health-related quality of life (HRQoL). However, illness perceptions and self-efficacy beliefs may also play a part in determining HRQoL in persons with COPD. The aim of this study was to explore the relationships between illness perceptions, self-efficacy, and HRQoL in a sample of persons with COPD in a longitudinal perspective. The context of the study was a patient education course from which the participants were recruited. Data concerning sociodemographic variables, social support, physical activity, illness perceptions, general self-efficacy, and HRQoL were collected before the course started and 1 year after completion. Linear regression was used in the analyses. The results showed that less consequences and less symptoms (identity) were associated with higher physical HRQoL (PCS) at baseline and at 1-year follow-up. Less emotional response was similarly associated with higher mental HRQoL (MCS) at both time points. Lower self-efficacy showed a borderline significant association with higher PCS at baseline, but was unrelated to MCS at both time points. Self-efficacy showed no influence on the associations between illness perceptions and HRQoL. In conclusion, the study showed that specific illness perceptions had a stable ability to predict HRQoL in persons with COPD, whereas self-efficacy did not. The associations between illness perceptions and HRQoL were not mediated by self-efficacy.

Keywords: illness perceptions, self-efficacy, longitudinal study, patient education

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an umbrella term for varying combinations of chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and chronic asthma. The disease is characterized by airflow limitation leading to symptoms such as breathlessness, decreased exercise tolerance, and sometimes chronic cough. The chronic nature of the disease calls for a treatment approach where educating patients about their disease and improving their self-management is central.

Psychological symptoms such as anxiety and depression are common amongst persons with COPD.1,2 Such symptoms are likely to be related to consequences of the disease in terms of decreased function and social isolation. This combination of disease-related problems, involving physical, psychological, and social factors, increases the risk for reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in persons with COPD.3,4 Disease severity per se, as classified by lung function, is suggested to be a poor predictor of HRQoL in persons with COPD,5,6 as this perspective does not consider the person’s illness experience. According to the Common Sense Model (CSM), illness perceptions are cognitive and emotional responses to a perceived health threat.7–9 The person’s subsequent coping with illness will be based on his or her lay perception of the illness. Illness perceptions concern the perceptions of cause, timeline, consequences, control, and identity, as suggested by theory and research.9,10

Research has demonstrated patients’ perceptions of illness to be associated with desirable outcomes in a variety of chronic somatic illnesses. Outcomes have included: quality of life and wellbeing;11–14 social functioning, emotional adjustment, and perceived health;15–17 self-management and health promoting behaviors;18–21 and treatment attendance and adherence.22–25 Attendance to pulmonary rehabilitation programs is important for COPD patients because it predicts their subsequent self-management, functioning, and overall outcome.25

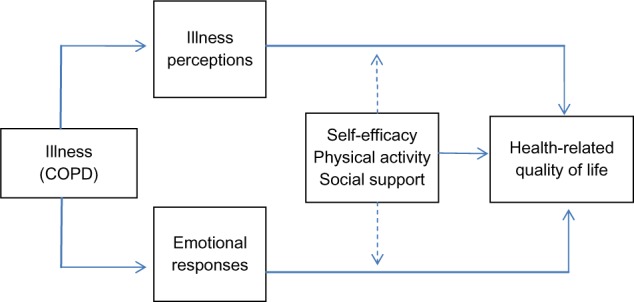

Successful self-management of COPD partly relies on the person’s “self-efficacy,” defined by Bandura as the perceived ability to perform the actions necessary to achieve a valued outcome.26 Research has demonstrated illness perceptions to be associated with self-efficacy beliefs in various clinical groups, including COPD,27,28 but also that these relationships may change over time.29 CSM suggests that coping behaviors originate from the person’s perception of the illness, while Bandura’s self-efficacy theory posits that specific coping behaviors are likely to occur only if the person believes that he or she can perform the actions involved in the coping behavior. Physical activity is one such coping strategy for persons with COPD,30 and increased physical activity and improved exercise endurance have been associated with improvements in quality of life.3,31,32 Similarly, social support has been associated with improved self-management19 and general self-efficacy in persons with COPD.27 In turn, these factors have been shown to impact on improved functioning.33 Taking this evidence into account, it could be suggested that self-efficacy, social support, and physical activity may affect the associations between illness perceptions and HRQoL. Figure 1 illustrates the associations explored in this study.

Figure 1.

The explored associations between the study variables.

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The objectives of this study are: 1) to explore the associations between illness perceptions and HRQoL in persons with COPD in a longitudinal perspective, and 2) to integrate CSM and self-efficacy theory by exploring whether associations between illness perceptions and HRQoL are mediated by factors such as self-efficacy, physical activity, and social support. Thus, this study addresses the following research questions:

How are illness perceptions, physical activity, social support, and self-efficacy associated with HRQoL in persons with COPD?

How are these associations maintained 1 year after a patient education course?

Do physical activity, social support, and self-efficacy mediate associations between illness perceptions and HRQoL?

Methods

The study has a prospective longitudinal design. Data were collected by means of 12 validated questionnaires from participants with COPD who attended a patient education course. In this sub-study, a combination of self-administered measures, including illness perceptions, physical activity, social support, self-efficacy, and HRQoL, were used.

Procedure

Participants with COPD were recruited on the first day of a patient education course. All had a severity of illness representing GOLD (Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) stage 2 and 3 (moderate to severe illness), according to international guidelines.34 The courses were held between April 2009 and November 2010 at six different sites in Norway (18 courses in total). Data were collected at baseline and at 12 months after course completion. The participants completed the baseline questionnaires on the first day of the course in a secluded room onsite. The questionnaires were returned in a sealed envelope collected by the project representative. At follow-up, posted questionnaires and stamped return self-addressed envelopes were sent to all participants. One reminder was sent to non-responders. All persons attending the course (n=127) were given verbal and written information about the study and invited to participate, and 100 consented (79%). Among the participants, 60 (60%) had valid responses on all the employed variables at baseline and at 12 months follow-up, and these persons constituted the sample of the present study. Missing scores in the indexes were tolerated up to 20% and were replaced by the individual’s mean score on the index.

Patient education courses

The patient education courses were designed to help the participants achieve a healthier lifestyle, and thereby improve their HRQoL. The courses had a duration that varied between 3 and 5 weeks, and the total number of hours the participants spent in educational sessions varied between 20 and 48 hours. The course content varied between sites, but generally included education about symptoms, risk factors for exacerbation, the role of smoking and nutrition, treatments, and self-management strategies which may be used. Some light physical exercise and breathing exercises were included.

Measurements

Health-related quality of life

HRQoL was measured with the Short Form 12, version 2 (SF-12v2), a widely used abbreviated form of the SF-36.35 Physical component summary scores (PCS) and mental component summary scores (MCS) were computed from the 12 items, and these summary scores were used as outcome variables in this study.36,37 Higher scores on PCS and MCS correspond with higher HRQoL in the physical and mental domains, respectively.

Illness perception

Illness perception was assessed with the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ), which assesses cognitive and emotional representations of illness in eight one-item domains.10 The BIPQ is a shortened version of the Illness Perception Questionnaire.38 The domains relate to: the extent of illness affecting the person’s life (consequences); the prospects of illness duration (timeline); the person’s feelings of control over the illness (personal control), the person’s faith in treatment (treatment control); the extent of symptoms experienced (identity); how much the person worries about the illness (concern); the person’s perception of being able to understand the illness (understanding); and how much the person is emotionally affected by the illness (emotional response). The items are assigned a score between 0 and 10, where higher score indicates more of the measured construct. The instrument has been shown to possess good psychometric properties, in terms of test–retest reliability and concurrent, predictive, and discriminant validity,10 adequately representing the dimensions constructed in a revised version of the original instrument.39

Physical activity

In this study, the participants’ level of physical activity was measured by two items from the large Norwegian “HUNT-2” survey.40 The measure was similarly used in a study of factors associated with HRQoL amongst morbidly obese persons.41 Items were scored by the current published definition,42 as explained in Table 1.

Table 1.

The scoring of items measuring self-reported level of activity

| Response category | Hours per week

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | <1 | 1–2 | ≥3 | |

| Low-level activity (not sweaty/breathless) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| High-level activity (sweaty/breathless) | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Notes: The question read as follows: “How much physical activity do you have in leisure time? Travel to work is regarded as leisure. State approximately how many hours per week you are physically active. Choose a number of hours that may apply to a typical week last year.”

Social support

In this study, social support was measured with participants’ response to one question: “I think I have enough support from people with whom I have a close relationship.” Response categories were on a five point Likert type scale, ranging from totally agree (1) to totally disagree (5).41 The scores were reversed so that higher scores indicated more support.

Self-efficacy

The General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE)43 measures optimistic self-beliefs in coping with the demands of life. It consists of ten statements that respondents rate on a scale from 1 “completely disagree” to 4 “completely agree.” The score is calculated by summing each individual’s scores for the items. The score range is 10–40, with higher scores indicating higher self-efficacy. High correlations with self-appraisal, self-acceptance, and optimism indicate theoretical accuracy of the self-efficacy concept.44 Further, factor analyses of the GSE have consistently produced the one-factor solution as used in this study. Item-total correlations have been found to range between 0.25 and 0.63, with factor loadings ranging between 0.32 and 0.74, and internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) =0.82.45 Internal consistency of the GSE scale in the present sample was α=0.89, which is considered excellent.46

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic data such as age (years), gender, marital status (married/cohabitating versus not), employment status (paid work versus not), and education level (≤12 years versus 13 years or more) were assessed.

Statistical analysis

Ordinal and categorical data were analyzed using chi-square (χ2) and Fisher’s exact test. Student’s independent sample t-tests were used to analyze continuous variables. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used for correlation analysis. Cronbach’s α was performed on baseline data to assess the internal consistency of the self-efficacy scale. To determine the predictive values of the independent variables for HRQoL, separate linear regression analyses were performed, with PCS and MCS scores at baseline and 12-month follow-up as the dependent variables in the analyses. Variables with a bivariate relationship r≥0.20 were used as independent variables in a backward stepwise regression analysis to obtain the most parsimonious predictive models for PCS and MCS, respectively.47

Secondly, the illness perception variables that in the stepwise regression were found to significantly predict outcome were included in the first block of a hierarchical regression model. Based on previous research and a solid theoretical rationale, self-efficacy was in all models included as an independent variable in the second block in order to explore potential mediation. Physical activity and social support were only included as independent variables in the second block if they were extracted from the stepwise procedure.

Due to the small sample size, the hierarchical linear regression results were controlled by re-running the analysis using the bootstrapping procedure. This procedure provides a more robust estimate of the confidence intervals of the regression coefficients. As all bivariate correlations between variables used in the analysis showed r<0.70, we assumed no multi-collinearity in the regression analyses. The level of significance was set at P<0.05, and all tests were two-tailed. Effect sizes were calculated by Cohen’s coefficient d.48 Cohen’s coefficient d is a standardized measure of effect size, representing the difference between the means divided by the pooled standard deviation (SD). Data were analyzed using SPSS (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for Windows version 19.0.49

Ethics

The Regional Medical Research Ethics Committee of Norway (REK S-08662c 2008/17575) and the Ombudsman of Oslo University Hospital approved the study. Informed written consent was received from all participants.

Results

Sample characteristics and change in HRQoL

The mean age among those who consented to participate (64.5 years, SD=9.4) was not significantly different from those who did not (n=27, mean (M) =67.6 years, SD=8.0, P=0.12). The proportion of women among the participants (47.0%) was not significantly different from the rest of the course population (53.0%, χ2=0.20, P=0.65).

The sociodemographic variables for the sample and their scores on physical activity, illness perceptions, self-efficacy, and HRQoL are shown in Table 2. Women reported significantly higher scores on personal control and understanding than men. Otherwise, the analyses did not reveal gender differences for the study variables. The participants showed no overall change in PCS between baseline (M=33.3, SD=11.2) and 12-month follow-up (M=34.5, SD=11.2, d=−0.11, P=0.23). Similarly, no change was shown in MCS between baseline (M=50.9, SD=10.7) and 12-month follow-up (M=50.2, SD=11.9, d=0.06, P=0.67).

Table 2.

Characteristics of men and women in the sample at baseline (N=60)

| Characteristic | All (N=60) | Men (n=36) | Women (n=24) | ES | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |||||

| Age – years (M/SD) | 65.4 (8.7) | 65.8 (8.7) | 64.9 (8.8) | 0.10 | 0.69 |

| Education >12 years | 17 (28.3) | 10 (27.8) | 7 (29.2) | 0.91 | |

| Living in relationship (n/%) | 41 (68.3) | 27 (75.0) | 14 (58.3) | 0.17 | |

| Working (n/%) | 14 (23.3) | 10 (27.8) | 4 (16.7) | 0.37 | |

| Social support (M/SD) | 4.3 (0.7) | 4.4 (0.6) | 4.2 (0.9) | 0.26 | 0.26 |

| Health behavior | (M/SD) | (M/SD) | (M/SD) | ||

| Physical activity (0–4) | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.4 (1.0) | 1.3 (0.7) | 0.12 | 0.40 |

| Illness perceptions | |||||

| Consequences (0–10) | 5.9 (2.3) | 5.5 (2.3) | 6.5 (2.2) | −0.44 | 0.09 |

| Timeline (0–10) | 9.6 (1.2) | 9.8 (0.6) | 9.3 (1.7) | 0.39 | 0.18 |

| Personal control (0–10) | 5.1 (2.1) | 4.6 (2.1) | 5.8 (2.3) | −0.54 | 0.04 |

| Treatment control (0–10) | 6.6 (2.5) | 6.4 (2.4) | 6.9 (2.7) | −0.20 | 0.48 |

| Identity (0–10) | 6.3 (1.9) | 6.1 (1.9) | 6.6 (2.0) | −0.26 | 0.31 |

| Concern (0–10) | 5.4 (2.5) | 5.2 (2.7) | 5.7 (2.2) | −0.20 | 0.47 |

| Understanding (0–10) | 7.0 (2.2) | 6.4 (2.2) | 7.9 (1.8) | −0.75 | <0.01 |

| Emotional response (0–10) | 4.5 (2.6) | 4.5 (2.6) | 4.5 (2.7) | 0.00 | 0.97 |

| Self-perceptions | |||||

| Self-efficacy (10–40) | 28.5 (5.4) | 28.1 (5.2) | 29.0 (5.9) | −0.16 | 0.50 |

| Quality of life | |||||

| PCS (0–100) | 33.3 (11.2) | 33.8 (10.7) | 32.7 (12.2) | 0.10 | 0.71 |

| MCS (0–100) | 50.9 (10.7) | 52.8 (9.6) | 48.1 (11.7) | 0.44 | 0.10 |

Notes: Differences between men and women in the sample were examined by t-tests, chi-square tests, and Fisher’s exact test. ESs are Cohen’s d. Higher scores on PCS and MCS reflect higher HRQoL.

Abbreviations: ES, effect size; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; M, mean; MCS, quality of life mental component score; PCS, quality of life physical component score; SD, standard deviation.

Associations between illness perception, self-efficacy, and HRQoL

The bivariate relationships between PCS, MCS, and the other study variables at baseline are shown in Table 3. Participating in paid work was significantly related to higher PCS at baseline. Perceiving fewer consequences, less symptoms, and less concern were illness perceptions related to higher PCS at baseline. Higher social support was related to higher MCS at baseline. Less treatment control, less concern, and less emotional response were illness perceptions related to higher MCS at baseline. Higher self-efficacy was also related to higher MCS at baseline.

Table 3.

Bivariate associations between the study variables in the sample at baseline (N=60)

| Variable | PCS

|

MCS

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | r | P | |

| Age | −0.10 | 0.43 | 0.17 | 0.20 |

| Sex | −0.05 | 0.71 | −0.22 | 0.10 |

| Education | 0.01 | 0.94 | 0.00 | 0.99 |

| Relationship status | −0.17 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.31 |

| Work status | −0.31 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.89 |

| Social support | −0.02 | 0.90 | 0.30 | 0.02 |

| Physical activity | 0.05 | 0.72 | −0.04 | 0.75 |

| Consequences | −0.57 | <0.001 | −0.14 | 0.29 |

| Timeline | −0.25 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.06 |

| Personal control | 0.07 | 0.58 | −0.05 | 0.71 |

| Treatment control | 0.04 | 0.76 | −0.28 | 0.03 |

| Identity | −0.66 | <0.001 | 0.04 | 0.77 |

| Concern | −0.33 | 0.01 | −0.27 | 0.04 |

| Understanding | −0.17 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| Emotional response | −0.24 | 0.07 | −0.44 | <0.001 |

| Self-efficacy | 0.12 | 0.35 | 0.26 | 0.04 |

| PCS | −0.13 | 0.33 | ||

Notes: Table content is Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) and corresponding P-values. Coding: male =1, female =2; education of 12 years or less =1, more than 12 years of education =2; living in paired relationship =1, not living in paired relationship =0; in paid work =0, not in paid work =1. Higher scores on PCS and MCS reflect higher HRQoL. All other measures are continuous measures, for which higher scores indicate higher levels.

Abbreviations: PCS, quality of life physical component score; MCS, quality of life mental component score.

Consequences and identity were included in the hierarchical regression analysis of variables related to PCS. Lower levels of consequences and identity were significantly related to higher PCS at baseline, accounting for 49.1% of the PCS variance. Including self-efficacy in the model in the second block added 2.7% to the explained variance. This factor was not directly related to PCS when the other factors were controlled for. At follow-up, lower levels of consequences and identity remained significantly related to higher PCS and accounted for 38.1% of the PCS variance. Adding self-efficacy to the model in the second block added 0.7% to the explained variance. Self-efficacy was not directly related to PCS at 12-month follow-up when the other factors were controlled for.

Social support, timeline, treatment control, and emotional response were included in the analysis of variables related to MCS. Among the illness perception variables included in the first block, less emotional response was significantly related to higher MCS at baseline. The model accounted for 28.9% of the MCS variance. Including self-efficacy and social support in the model in the second block added 9.2% to the explained variance. Self-efficacy was not directly related to MCS, whereas higher social support was directly related to higher MCS when the other factors were controlled for. At follow-up, only less emotional response retained a direct relationship with higher MCS. The model accounted for 11.8% of the variance in MCS. Adding self-efficacy and social support to the model in the second block added 3.1% to the explained variance. Neither self-efficacy nor social support were directly related to MCS at follow-up when the other factors were controlled for. The results from the hierarchical regression analyses are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Predictors of health-related quality of life at baseline and at one-year follow-up by hierarchical regression analysis (N=60)

| Variable | Baseline PCS

|

One-year PCS

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | B1 | B2 | r | B1 | B2 | |

| Consequences | −0.57a | −0.30a | −0.35a | −0.56a | −0.38a | −0.41a |

| Identity | −0.66a | −0.49a | −0.47a | −0.53a | −0.32b | −0.31b |

| Explained varianced | 49.1% | 38.1% | ||||

| Self-efficacy | 0.12 | −0.17 | 0.04 | −0.09 | ||

| R2 changec | 2.7% | 0.7% | ||||

| Explained varianced | 51.8% | 38.7% | ||||

| Variable |

Baseline MCS

|

One-year MCS

|

||||

| r | B1 | B2 | r | B1 | B2 | |

|

| ||||||

| Timeline | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| Treatment control | −0.28b | −0.19 | −0.17 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.16 |

| Emotional response | −0.44a | −0.42a | −0.35a | −0.31b | −0.33b | −0.30b |

| Explained varianced | 28.9% | 11.8% | ||||

| Self-efficacy | 0.26b | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.07 | ||

| Social support | 0.30b | 0.25b | 0.19 | 0.17 | ||

| R2 changec | 9.2% | 3.1% | ||||

| Explained varianced | 38.1% | 14.9% | ||||

Notes: Higher scores on PCS and MCS reflect higher HRQoL. At both time points, illness perception variables were entered as independent variables in the first block (B1), whereas self-efficacy (for PCS) and self-efficacy and social support (for MCS) were entered as additional independent variables in the second block (B2). Table content is bivariate correlation coefficients (Pearson’s r) and standardized beta coefficients (β).

P<0.01

P<0.05

R2 change is the amount of variance in the dependent variable accounted for by the second block of independent variables

explained variance is the total amount of variance explained by the models.

Abbreviations: HRQoL, health-related quality of life; MCS, quality of life mental component score; PCS, quality of life physical component score.

The procedure used for supporting the hierarchical regression analysis (bootstrapping) did not change the main results presented in Table 4 (data not shown). However, lower self-efficacy showed a borderline significant relationship with higher PCS at baseline following this procedure (P=0.06), and a longer perceived timeline was found to be significantly related to higher baseline MCS (P=0.02).

Attrition

The mean age of the participants with complete data at 12 month follow-up (65.4 years, SD=8.7) did not significantly differ from the age of the participants from the baseline sample with missing scores (n=40, M=63.1 years, SD=10.1, d=0.24, P=0.22). The proportion of women in the study sample (n=24, 40.0%) was not significantly different from the proportion of women with missing scores at 12-month follow-up (n=23, 57.5%, χ2=2.95, P=0.09).

When we compared these groups with regards to their respective scores at baseline for the other variables, we found that the participants had higher scores for physical activity (M=1.4, SD=0.9) than the dropouts (M=0.9, SD=0.9, d=0.55, P=0.01). They reported to be less concerned about their illness (M=5.4, SD=2.5) compared with those with missing scores (M=7.2, SD=2.7, d=−0.69, P<0.01), and reported less emotional response (M=4.5, SD=2.6) than their counterparts (M=6.3, SD=3.0, d=−0.64, P<0.01). In addition, the participants had higher scores for self-efficacy (participants M=28.5, SD=5.4 versus dropouts M=23.6, SD=7.3, d=0.76, P<0.01) and on the MCS (participants M=50.9, SD=10.7 versus dropouts M=42.5, SD=13.5, d=0.69, P<0.01) than the dropouts. The analyses did not reveal other statistically significant differences between the groups with regards to the variables used in this study (data not shown).

Discussion

This study explored the associations between illness perceptions, physical activity, social support, self-efficacy, and HRQoL in persons with COPD before starting a patient education course and at 12-month follow-up. In addition, the study explored whether self-efficacy, physical activity, and social support mediated the associations between illness perceptions and HRQoL. Less consequences of illness and less symptoms (identity) explained a relatively high proportion of people’s PCS and were directly associated with higher PCS at baseline and at 12-month follow-up. Less emotional response and higher social support were directly associated with higher MCS at baseline. At 1-year follow-up, less emotional response was the only variable significantly related to higher MCS. Lower self-efficacy showed a borderline significant association with higher PCS at baseline, but was unrelated to MCS at both time points. Neither self-efficacy, nor physical activity, nor social support mediated the associations between illness perceptions and HRQoL.

Factors associated with HRQoL

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) model describes a person’s degree of function or disability as being related to the interaction of the disease with the context it appears in.50 Similarly, it makes sense to consider a person’s HRQoL as influenced by a range of interacting factors, suggesting that HRQoL may arise from the interaction between environmental factors and person-related factors, as well as by the disease itself. However, the meaning and significance of a disease is not given by the disease itself, but is partly constructed by the person’s experience.8,9

Illness perceptions at baseline concerning consequences and identity were shown to relate to PCS – the participants with lower scores on these variables had higher scores on PCS. Further, the baseline levels of consequences and identity continued to predict PCS at 12-month follow-up, and a large proportion of PCS variance was explained by these two variables. Experiencing burdensome symptoms of the illness (identity), as well as illness-related limitations (consequences) in daily life, can understandably relate to lower HRQoL in the physical domain. Similarly, a recent study found COPD patients with lower wellbeing to have higher scores in the identity and consequences domains compared with their counterparts with higher wellbeing.11 The fact that these variables continued to predict PCS 1 year after the patient education course is noteworthy. It indicates that persons who have high initial levels in these illness perception domains may also be at risk of experiencing poorer HRQoL at a later point during the course of the illness.

Self-efficacy was not related to PCS, nor did it mediate the relationships shown between consequences and identity and PCS. However, by running the analysis using the bootstrapping procedure, we found a borderline significant relationship between higher self-efficacy and lower PCS. Arnold and colleagues found that higher HRQoL was related to improved self-efficacy, concluding that personal control related to functioning was important in the adjustment to COPD.51 Research has also suggested that low self-efficacy may interfere with coping strategies and self-management,52 which in turn can have a negative effect on HRQoL. The trend found in our sample appears counterintuitive and opposes previous research results. Thus, we would suggest that further studies examine the potentially complex role of self-efficacy in more depth before drawing any conclusions.

The only illness perception dimension directly associated with MCS at baseline, less emotional response, remained so at follow-up. The link between less emotional response and higher HRQoL is supported in previous research on patients with COPD.14 The result indicates that persons who have high initial emotional response levels may be at risk of experiencing poorer MCS later during the course of illness. Theory suggests that a higher level of emotional response generally is a result of the person’s view of the health threat imposed by the illness.9 Alternatively, emotional response to illness may be viewed as an aspect of emotional responsiveness as a personality characteristic. This potential link between illness perceptions and underlying personality traits has received some research attention in the later years, reporting higher emotional response to be associated with less emotional stability in patients with diabetes,53 as well as to general negative affectivity and social inhibition (referred to as Type D personality) in patients with myocardial infarction.54 It may be that persons with a tendency to respond to life events with strong emotions are more vulnerable to experiencing a lower MCS. Having a chronic and progressive disease such as COPD may frequently bring about negative life events. Persons who typically respond to such events with negative emotion may be at risk of experiencing lower HRQoL.

Higher social support was significantly associated to higher MCS at baseline, but did not mediate the association between illness perceptions and MCS, with these associations remaining largely unchanged. This result suggests that emotional response and social support are both important factors related to MCS, and both in their own right. Social support can be provided in many forms; however, to what extent the participants have thought of an emotional type support when responding, or rather an instrumental type, is unclear. In any case, an experience of receiving sufficient support from close persons can be logically related to a higher HRQoL in the mental health domain. Empirically, this has been supported by a previous study on morbidly obese persons, demonstrating a positive association between higher perceived social support at baseline and higher HRQoL 1 year later.55 However, in the COPD sample in the present study, the relationship had disappeared 1 year after the patient education course. This may be due to social support being a dynamic feature; it may change in response to a person’s changing needs, but it may also change in response to the person’s quality of relationships with others. Thus, the vanished association 1 year later may be due to changes in the social support provided. Alternatively, it may be due to the participants’ changed perception of the support that was provided.

Self-efficacy was not found to be related to MCS, nor did it mediate the relationships shown between social support and emotional response and MCS. However, a longer timeline (expected illness duration) was significantly associated with higher MCS at baseline. It seems puzzling that perceiving the illness as more severe in the timeline domain would be related to higher MCS. Generally, perceiving the illness as more severe, resulting in less hope for controlling its course, is considered a risk factor for experiencing demotivation and disengagement from self-management.19 More specifically, Scharloo and colleagues found less belief in a long-term and non-improving course of illness to be related to better functioning in patients with COPD.14 However, it may be that perceiving a chronic timeline – which is an accurate perception for persons with COPD – can express a state of reconciliation with COPD as a chronic disease. It is a disease that the person must try to manage to the best of his or her abilities, but in spite of good intentions and best behaviors, it cannot be ultimately defeated. If a longer timeline expresses such a stance, its relationship with a higher HRQoL in the mental health domain may be more understandable.

Another recent study concluded that participants enrolled in a 4-week self-management program did show significant improvements on the emotional dimension of HRQoL at 12-month follow-up compared with the control group, whereas the functional dimension showed no significant differences.56 Our study, partly in contrast, demonstrated no significant change in either of the HRQoL dimensions between baseline and follow-up. The duration and content of the self-management program used in the cited study appears comparable to the patient education courses our sample received. One should, however, keep in mind that the more negative results of the present study might be related to a wide range of uncontrolled factors.

Study limitations

Patient attrition during pulmonary rehabilitation programs is a well known phenomenon.25 In this study, the original sample was relatively small with limited statistical power to control for more independent variables in the multivariate analysis. Only 60 (60%) of the original baseline sample provided valid responses on the questionnaires at follow-up. This is a somewhat lower level of retention compared with previous research on COPD patients (60% versus 69%).1 However, compared with the results presented by Garrod and colleagues,1 the considerably longer follow-up in our study – 1 year versus 7 weeks – may account for our lower level of retention. In our study, large differences (d>0.40) between the sample and the dropouts at baseline were related to physical activity, illness perceptions, self-efficacy, and MCS. Hence, the results may not be a true representation of the general population with COPD. In addition, the design of the study does not allow for drawing inferences concerning the effects from the patient education course, from subsequent treatment or self-help group participation, or from other events or processes that may have occurred for the participants during the 12-month follow-up period.

The study did not evaluate the results based on illness severity. Patients with COPD are typically allocated into one of four severity categories based on lung capacity,34 and all participants were categorized within GOLD stage 2 or 3. As the sample included patients with a range of illness severity and symptoms, this may have been reflected by their illness perceptions and self-efficacy beliefs. The study is therefore limited by our lack of objective data concerning illness severity in the sample, and it is recommended that objective measures should be used more extensively.57

Conclusion and clinical implications

This study investigated factors related to HRQoL in a sample of persons with COPD at the beginning of a patient education course and at 12-month follow-up. Consequences and identity were associated with PCS at both time points. Similarly, emotional response was associated with MCS at both time points. Lower self-efficacy showed a borderline significant association with higher PCS at baseline, but was unrelated to MCS at both time points. Considered together, the results showed that specific illness perceptions had a stable ability to predict HRQoL assessed in persons with COPD, whereas self-efficacy did not. Moreover, the associations between illness perceptions and HRQoL were largely unaffected by self-efficacy, social support, and physical activity.

The results indicate that specific illness perceptions are valuable prognostic indicators of subsequent HRQoL. Thus, in clinical settings, specific attention should be paid to how COPD patients perceive their illness. Those who attribute many and/or severe symptoms to their illness, who perceive COPD to have marked consequences for their daily life, and who are emotionally affected by the illness appear to be particularly at risk for experiencing poorer HRQoL. Interventions targeted at the COPD patients’ perceptions of their illness, and not only at their symptoms and signs per se, may be a useful complementary approach to this group.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the Norwegian Centre for Patient Education, Research and Service Development, Oslo, Norway. The funding source had no further involvement in any part of the research process. The contributions from the following Norwegian institutions are acknowledged: The Patient Education Centers at Oslo University Hospital – Aker, Oslo; Deacon’s Hospital, Oslo; Lovisenberg Diakonale Hospital, Oslo; Asker and Bærum Hospital, Sandvika; Østfold Hospital, Sarpsborg; and Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger. In addition, we acknowledge the contributions of the Pulmonary Rehabilitation Clinics at Oslo University Hospital – Ullevål, Oslo; Krokeide Center, Nærland; and Glittreklinikken, Nittedal.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have no declarations of interest related to this article.

References

- 1.Garrod R, Marshall J, Barley E, Jones PW. Predictors of success and failure in pulmonary rehabilitation. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(4):788–794. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00130605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yohannes AM, Willgoss TG, Baldwin RC, Connolly MJ. Depression and anxiety in chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, relevance, clinical implications and management principles. Int J of Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(12):1209–1221. doi: 10.1002/gps.2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almagro P, Castro A. Helping COPD patients change health behavior in order to improve their quality of life. Int J COPD. 2013;8:335–345. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S34211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shavro SA, Ezhilarasu P, Augustine J, Bechtel JJ, Christopher DJ. Correlation of health-related quality of life with other disease severity indices in Indian chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Int J COPD. 2012;7:291–296. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S26405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amoros MM, Mas-Tous C, Renom-Sotorra F, Rubi-Ponseti M, Centeno-Flores MJ, Gorriz-Dolz MT. Health-related quality of life is associated with COPD severity: a comparison between the GOLD staging and the BODE index. Chron Respir Dis. 2009;6(2):75–80. doi: 10.1177/1479972308101551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huijsmans R, de Haan A, ten Hacken NH, Straver RVM, van’t Hul AJ. The clinical utility of the GOLD classification of COPD disease severity in pulmonary rehabilitation. Respir Med. 2008;102(1):162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leventhal H, Benyamini Y, Brownlee S, et al. Illness representations: theoretical foundations. In: Petrie KJ, Weinman JA, editors. Perceptions of Health and Illness. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1997. pp. 19–45. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D. The common sense representation of illness danger. In: Rachman S, editor. Contributions to Medical Psychology. New York: Pergamon Press; 1980. pp. 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cameron LD, Leventhal H, editors. The Self-regulation of Health and Illness Behaviour. London: Routledge; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, Weinman J. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60:631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braido F, Baiardini I, Menoni S, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patient well-being and its relationship with clinical and patient-reported outcomes: a real-life observational study. Respiration. 2011;82(4):335–340. doi: 10.1159/000326923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glattacker M, Heyduck K, Meffert C. Illness beliefs and treatment beliefs as predictors of short and middle term outcome in depression. J Health Psychol. 2013;18(1):139–152. doi: 10.1177/1359105311433907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rochelle TL, Fidler H. The importance of illness perceptions, quality of life and psychological status in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. J Health Psychol. 2012:1–12. doi: 10.1177/1359105312459094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scharloo M, Kaptein AA, Schlosser M, et al. Illness perceptions and quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Asthma. 2007;44(7):575–581. doi: 10.1080/02770900701537438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chilcot J, Wellsted D, Davenport A, Farrington K. Illness representations and concurrent depression symptoms in haemodialysis patients. J Health Psychol. 2011;16(7):1127–1137. doi: 10.1177/1359105311401672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jopson NM, Moss-Morris R. The role of illness severity and illness representations in adjusting to multiple sclerosis. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54(6):503–511. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00455-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scharloo M, Kaptein AA, Weinman JA, Willems LN, Rooijmans HG. Physical and psychological correlates of functioning in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Asthma. 2000;37(1):17–29. doi: 10.3109/02770900009055425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conner M, Norman P, editors. Predicting Health Behaviour. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Disler RT, Gallagher RD, Davidson PM. Factors influencing self-management in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(2):230–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaptein AA, Scharloo M, Fischer MJ, et al. Illness perceptions and COPD: an emerging field for COPD patient management. J Asthma. 2008;45(8):625–629. doi: 10.1080/02770900802127048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nouwen A, Law GU, Hussain S, McGovern S, Napier H. Comparison of the role of self-efficacy and illness representations in relation to dietary self-care and diabetes distress in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Psychol Health. 2009;24(9):1071–1084. doi: 10.1080/08870440802254597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horne R. Representations of medication and treatment: advances in theory and measurement. In: Petrie KJ, Weinman JA, editors. Perceptions of Health and Illness. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1997. pp. 155–188. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsiao C-Y, Chang C, Chen C-D. An investigation on illness perception and adherence among hypertensive patients. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2012;28(442):447. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Senior V, Marteau TM, Weinman J. Self-reported adherence to cholesterol-lowering medication in patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia: the role of illness perceptions. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;18:475–481. doi: 10.1007/s10557-004-6225-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischer MJ, Scharloo M, Abbink JJ, et al. Drop-out and attendance in pulmonary rehabilitation: the role of clinical and psychosocial variables. Respir Med. 2009;103(10):1564–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: the Exercise of Control. New York: WH Freeman and Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonsaksen T, Lerdal A, Fagermoen MS. Factors associated with self-efficacy in persons with chronic illness. Scand J Psychol. 2012;53(4):333–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2012.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lau-Walker M. Relationship between illness representation and self-efficacy. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48(3):216–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lau-Walker M. Predicting self-efficacy using illness perception components: a patient survey. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11(4):643–661. doi: 10.1348/135910705X72802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bourbeau J. Making pulmonary rehabilitation a success in COPD. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;140(w13067):1–7. doi: 10.4414/smw.2010.13067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaplan RM, Ries AL. Quality of life: concept ad definition. COPD. 2007;4:263–271. doi: 10.1080/15412550701480356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katajisto M, Kupiainen H, Rantanen P, et al. Physical inactivity in COPD and increased patient perception of dyspnea. Int J COPD. 2012;7:743–755. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S35497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marino P, Sirey JA, Raue PJ, Alexopoulos GS. Impact of social support and self-efficacy on functioning in depressed older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J COPD. 2008;3(4):713–718. doi: 10.2147/copd.s2840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gold PM. The 2007 GOLD Guidelines: a comprehensive care framework. Respir Care. 2009;54:1040–1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loge JH, Kaasa S, Hjermstad MJ, Kvien TK. Translation and performance of the Norwegian SF-36 Health Survey in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. I. Data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability, and construct validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1069–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ware JE, Kosinski MA, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B. How to score: version 2 of the SF-12v2 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Moss-Morris R, Horne R. The Illnes Perception Questionnaire: a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of illness. Psychol Health. 1996;11:431–445. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moss-Morris R, Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Horne R, Cameron LD, Buick D. The revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R) Psychol Health. 2002;17(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holmen J, Midthjell K, Krüger O, et al. The Nord-Trondelag Health Study 1995–1997 (HUNT-2): objectives, contents, methods, and participation. Norsk Epidemiol. 2003;13:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lerdal A, Andenaes R, Bjornsborg E, et al. Personal factors associated with health-related quality of life in persons with morbid obesity on treatment waiting lists in Norway. Qual Life Res. 2011;20(8):1187–1196. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9865-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thorsen L, Nystad W, Stigum H, et al. The association between self-reported physical activity and prevalence of depression and anxiety disorder in long-term survivors of testicular cancer and men in a general population sample. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13(8):637–646. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0769-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. Generalized self-efficacy scale. In: Weinman J, Wright S, Johnston M, editors. Measures in Health Psychology: a User’s Portfolio. UK: Nfer-Nelson, Winsor; 1995. pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Posadzki P, Stockl A, Musonda P, Tsouroufli M. A mixed method approach to sense of coherence, health behaviors, self-efficacy and optimism: towards the operationalization of positive health attitudes. Scand J Psychol. 2010;51:246–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leganger A, Kraft P, Roysamb E. General and task specific self-efficacy in health behaviour research: Conceptualization, measurement and correlates. Psychol Health. 2000;15(1):51–69. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fayers PM, Machin D. Quality of Life: the Assessment, Analysis, and Interpretation of Patient-Reported Outcomes. 2nd ed. West Sussex: Wiley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Field A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cohen J. A Power Primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.SPSS for Windows [computer program]. Version 19. Chicago, IL: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 50.World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Geneva: WHO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arnold R, Ranchor AV, Koeter GH, et al. Changes in personal control as a predictor of quality of life after pulmonary rehabilitation. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61(1):99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marks R, Allegrante JP, Lorig K. A review and synthesis of research evidence for self-efficacy-enhancing interventions for reducing chronic disability: implications for health education practice (part II) Health Promot Pract. 2005;6(2):148–156. doi: 10.1177/1524839904266792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lawson VL, Bundy C, Harvey JN. The influence of health threat communication and personality traits on personal models of diabetes in newly diagnosed diabetic patients. Diabet Med. 2007;24(8):883–891. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams L, O’Connor RC, Grubb NR, O’Carroll RE. Type D personality and illness perceptions in myocardial infarction patients. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70(2):141–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andenæs R, Fagermoen MS, Eide H, Lerdal A. Changes in health-related quality of life in people with morbid obesity attending a mearning and mastery course. A longitudinal study with 12-months follow-up. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10(95):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moullec G, Favreau H, Lavoie KL, Labrecque M. Does a self-management education program have the same impact on emotional and functional dimensions of HRQoL? COPD. 2012;9:36–45. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2011.635729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu WC, Fu SN, Tai EL, et al. Spirometry is underused in the diagnosis and monitoring of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Int J COPD. 2013;8:389–395. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S48659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]