SUMMARY

1. Chronic electrical stimulation of the carotid sinuses has provided unique insight into the mechanisms that cause sustained reductions in blood pressure during chronic suppression of central sympathetic outflow.

2. Because renal denervation does not abolish the sustained fall in arterial pressure in response to baroreflex activation, this observation has seemingly challenged the concept that the kidneys play a critical role in long term control of arterial pressure during chronic changes in sympathetic activity. The objective of this study was to use computer simulations to provide a more comprehensive understanding of physiological mechanisms that mediate sustained reductions in arterial pressure during prolonged baroreflex-mediated suppression of central sympathetic outflow.

3. Physiological responses to baroreflex activation under different conditions were simulated by an established mathematical model of human physiology (QHP2008, http://groups.google.com/group/modelingworkshop, or online only supplementary data). The model closely reproduced empirical data, providing important validation of its accuracy.

4. The simulations indicated that baroreflex-mediated suppression of renal sympathetic nerve activity does chronically increase renal excretory function but that, in addition, hormonal and hemodynamic mechanisms also contribute to this natriuretic response. The contribution of these redundant natriuretic mechanisms to the chronic lowering of blood pressure is of increased importance when suppression of renal adrenergic activity is prevented, such as after renal denervation. Activation of these redundant natriuretic mechanisms occurs at the expense of excessive fluid retention.

5. More broadly, this study illustrates the value of numerical simulations in elucidating physiological mechanisms that are not obvious intuitively and, in some cases, not readily testable in experimental studies.

Keywords: baroreflex, blood pressure, computer simulations, kidney

INTRODUCTION

The recent development of technology for chronic electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus has provided greater insight into the mechanisms that mediate the chronic effects of baroreflex activation on arterial pressure.1-5 Prolonged activation of the baroreflex by this methodology produces sustained and controllable reductions in arterial pressure. Since this pressure response is associated with sustained suppression of the sympathetic nervous system, chronic electrical stimulation of the afferent limb of the carotid baroreflex provides a unique approach for elucidating the effector mechanisms that are causal in mediating long-term reductions in arterial pressure during suppression of central sympathetic outflow. While some experimental findings during baroreflex activation have confirmed preconceived notions, others have been equivocal and controversial. This paper provides a theoretical basis to account for one of the more controversial findings: that bilateral renal denervation fails to abolish the long-term blood pressure lowering effects of carotid baroreflex activation.3 As the renal nerves are a critical link between alterations in central sympathetic outflow and renal excretory function, the above finding appears to fly in the face of the concept that the kidneys play a critical role in long-term control of arterial pressure during chronic changes in sympathetic activity.

Baroreflex-mediated alterations in sympathetic activity to the heart and the peripheral vasculature are important in the acute control of arterial pressure, but whether these responses are long term determinants of blood pressure is unclear.6;7 Decreased sympathetic activity, as achieved by activation of the baroreflex, decreases arteriolar resistance and increases venous capacitance. These effects alone, if sustained, would be expected to lead to a persistent reduction in blood pressure if blood volume were to remain constant. However, in response to a fall in arterial pressure, the kidneys retain salt and water and continue to do so until blood volume increases sufficiently to restore arterial pressure to normal levels.6;7 Thus, it is the progressive rise in arterial pressure that prevents protracted fluid retention by a process referred to as pressure natriuresis. On the other hand, if inhibition of sympathetic activity were to also include actions on the kidneys to increase renal excretory function and shift the pressure natriuresis relationship to a lower arterial pressure, then the fluid retention and the attendant increase in arterial pressure associated with baroreflex-mediated sympathoinhibition would be attenuated. Thus, an increase in renal excretory function would appear to be a prerequisite for a sustained decrease in arterial pressure during baroreflex activation.

Because sodium balance is achieved at a reduced arterial pressure during chronic electrical stimulation of the carotid baroreflex, we suggested that prolonged activation of the baroreflex has sustained effects to enhance the pressure natriuresis relationship. 1;7 Recent findings also indicate that the baroreflex is chronically activated in hypertension and has sustained effects to inhibit renal sympathetic nerve activity and promote sodium excretion.7;8 Thus, one way in which prolonged baroreflex activation could enhance pressure natriuresis and produce long-term reductions in arterial pressure is by inhibiting renal sympathetic nerve activity. This hypothesis was tested in chronically instrumented dogs before and after bilateral renal denervation. 3 When the renal nerves were intact, sodium balance was achieved at a reduced arterial pressure during prolonged activation of the baroreflex. However, after renal denervation, responses to activation of the baroreflex were not significantly different from those observed before renal denervation, although there tended to be greater sodium retention and a smaller fall in blood pressure during baroreflex activation. Astonishingly, the presence of renal nerves was not an obligate requirement for achieving long-term reductions in arterial pressure during prolonged activation of the baroreflex. Because of the importance of the pressure natriuresis relationship and, therefore, the kidneys in long-term control of arterial pressure, one of the authors (TEL) has been asked on many occasions to explain these unexpected findings. The short answer has been the following: during prolonged baroreflex activation there is a tendency for more fluid retention after renal denervation than when the renal nerves are intact. Accordingly, the additional fluid retention may stimulate or produce greater activation of redundant natriuretic mechanisms, such as by increasing the secretion of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP). In turn, greater activation of redundant natriuretic mechanisms may play an increasing important role in modifying the pressure natriuresis relationship and permitting the maintenance of sodium balance at a reduced blood pressure.

Mathematical models and simulation are important tools for discovering key causal relationships in normal and pathophysiological processes. An especially important aspect of mathematical models is that they are able to demonstrate complex chronic relationships that are not obvious intuitively and, in some cases, not readily testable in experimental studies. Mathematical models also lead to testable hypotheses. While there are many models of individual organs and systems in the literature, there are no extensive mathematical models demonstrating integration across systems other than the models developed at the University of Mississippi Medical Center by Guyton, Coleman, and colleagues. The roots of the current integrative model of human physiology go back to the original Guyton-Coleman model of circulatory control, which introduced the importance of pressure natriuresis in long term control of arterial pressure.9 Pressure natriuresis has remained as a core concept in subsequent versions of the original Guyton-Coleman model including “Human”, “Quantitative Circulatory Physiology” (QCP), and now “Quantitative Human Physiology” (QHP2008). While the original Guyton-Coleman model that led to the concept of the renal body fluid mechanism for long-term control of arterial pressure was composed of ~ 400 variables and focused on cardiovascular physiology, the current QHP model is composed of~ 4,500 variables and associated equations modeling human physiology and includes the cardiovascular, neural, renal, endocrine, metabolic, and respiratory systems.

In the QHP2008 model, variables are described by differential and / or algebraic equations and numerical solutions are computed simultaneously for increments of the independent variable, time. Relationships between variables, in terms of the magnitude and directionality of the effect of one variable on another, are described by continuous functions interpolated from discrete data points obtained from experimental data. All variables and equations are organized in XML files, which can be opened by any text editor. The model structure is parsed, equations are solved and results are displayed graphically by a compiled executable file. In addition, by way of XML files, users can add or modify existing content (variables and relationships), making QHP a user-friendly, interactive modeling platform. The QHP2008 model in its entirety is readily accessible as online only supplementary data, or at http://groups.google.com/group/modelingworkshop.

We used QHP2008 to simulate physiological responses to chronic electrical stimulation of the carotid baroreflex in order to gain a better understanding of the mechanisms that account for the sustained lowering of blood pressure during prolonged activation of the baroreflex. First, we determined whether this model accurately mimics the empirical responses observed during prolonged stimulation of the carotid baroreflex (Figure 1). Second, we tested the hypothesis that chronic activation of the baroreflex has sustained effects to inhibit renal sympathetic nerve activity but that this response is not an obligate requirement for achieving sustained reductions in arterial pressure. Finally, we tested the hypothesis that redundant natriuretic mechanisms become more prominent in promoting sodium excretion when reductions in sympathetic outflow occur throughout the body but are devoid of functional effects on the kidneys, as would be expected after renal denervation.

FIGURE 1.

Hemodynamic and hormonal responses to 1 week of carotid baroreflex activation: comparison between experimental data (bars, redrawn from 1) and QHP2008 simulation (line). a. MAP; b. heart rate (HR); c. urinary sodium excretion (UNaV); d. plasma norepinephrine concentration (NE); e. plasma renin activity (PRA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Model performance: response to 1 week of baroreflex activation – comparison with experimental data

Typical experimental responses to prolonged electrical stimulation of the carotid sinuses in chronically instrumented dogs are illustrated by the bars in Figure 1 representing the findings from an earlier communication.1 After control measurements, the carotid baroreflex was activated for 7 days. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) decreased immediately following activation of the baroreflex and on day 1 there was modest sodium retention in association with a reduction in mean arterial pressure of ~ 20 mmHg. Presumably retention of sodium on day 1 was due to the abrupt and pronounced fall in MAP associated with sympathoinhibition and the concomitant reduction in peripheral resistance and increase in vascular capacitance. After day 1, daily sodium balance was achieved, while reductions in arterial pressure were sustained throughout the 7 days of baroreflex activation. Heart rate decreased in parallel with MAP. Activation of the baroreflex was associated with a sustained decrease (~ 35%) in plasma norepinephrine (NE) concentration indicating persistent suppression of central sympathetic outflow. Despite the pronounced fall in MAP, plasma renin activity (PRA) did not increase during prolonged baroreflex activation. All values returned to control levels during a 7-day recovery period.

Although QHP2008 accurately predicts many physiological and pathophysiological processes, it was important to first determine whether this model could reproduce the empirical findings previously reported in the above study. Figure 1 shows model predictions (solid line) superimposed on the experimental responses redrawn from our previous communication. To mimic experimental conditions, the sodium intake of the human model was fixed at 180 mMol/ day, which is equivalent on a weight basis to the fixed intake of the dogs (60 mMol/day). Access to water was ad libitum but food intake was fixed to correspond to the experimental conditions in the canine study. The simulation was first allowed to run for 3 months with the above parameters to allow model variables to reach a steady-state. Subsequently, after 3 days of baseline, arterial baroreceptor input into the CNS was increased by 70% and fixed at this value for the next week to mimic the constant electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus. Increasing baroreceptor activity up to 200% of control produces progressive reductions in MAP [MAP = −33.1 * (baroreceptor activity) + 129; R2 = 0.99]. The level of activation selected (70%) was designed to produce the same day 1 decrease in arterial pressure as observed experimentally.1 Because the time course and extent of resetting of the atrial reflex has not been established, afferent activity from atrial receptors was maintained at control levels. It is important to note that the time intervals used to compute model solutions are determined by preset integration error limits and in our simulation ranged from ~ 1 min to ~ 30 min. Therefore, while experimental values are integrated over 24 h, the simulations also display the dynamic changes of the variables.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the hemodynamic, neurohormonal, and electrolyte excretion responses in the simulation matched rather closely the actual experimental observations made during baroreflex activation. Most notably:

Day 1 reductions in MAP of ~ 23 mmHg were sustained for the entire period of baroreflex activation, and MAP returned rapidly to control levels during the recovery period.

Heart rate decreased along with MAP throughout baroreflex activation, a response dominated by activation of the parasympathetic nervous system.

Sodium excretion decreased in parallel with the fall in MAP on days 1-2 before returning to control levels during the final days of baroreflex activation. On day 1 of the recovery period, the retained sodium was excreted before sodium balance was subsequently achieved.

There was a sustained reduction in plasma NE concentration of ~ 35% under both conditions, indicating sustained suppression of central sympathetic outflow.

Remarkably, despite the pronounced reduction in MAP, there was no sustained increase in PRA during baroreflex activation. In the model, the key determinants of renin secretion are sodium delivery at the macula densa and beta adrenergic stimulation of juxtaglomerular cells. The model indicates that throughout baroreflex activation delivery of sodium to the macula densa is reduced, but that this stimulatory effect on renin secretion is offset by diminished activation of beta adrenergic receptors concomitant with decreased renal nerve activity (see below). The simulation also indicates a transient increase in renin secretion on day 1 of baroreflex activation (peak at 4 hours) corresponding to the nadir in sodium delivery to the macula densa. This increase in PRA was not measured experimentally as initial blood sampling was not made until 24 hours after initiating baroreflex activation.

Thus, the above QHP2008 simulations indicate that the model closely mimics the actual experimental observations during chronic electrical stimulation of the carotid sinuses. The congruency in responses between the actual experiment and the simulation provides confidence that the model can be used to accurately predict the mechanisms that enhance pressure natriuresis and permit the maintenance of sodium balance at reduced arterial pressure. As indicated above, by increasing renal excretory function, suppression of renal sympathetic nerve activity is one likely mechanism that contributes to the lowering of MAP during prolonged activation of the baroreflex. However, surprisingly, our empirical findings indicated that renal denervation had little impact on the magnitude of fall in MAP during prolonged baroreflex activation.3

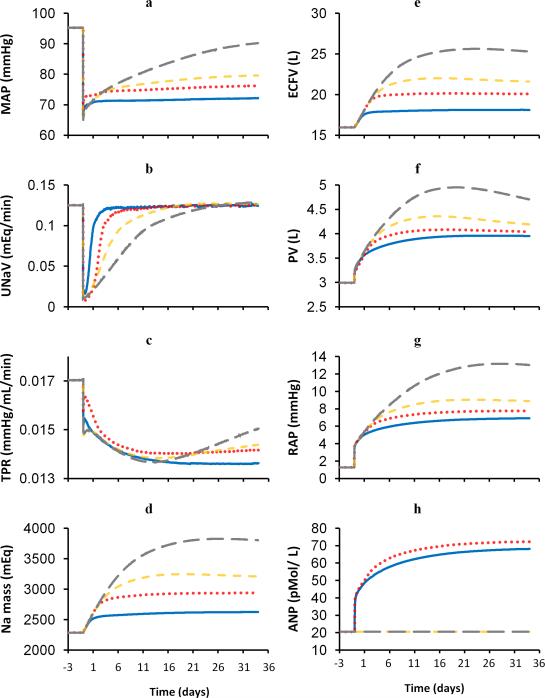

Simulations for 5 weeks of carotid baroreflex activation

In light of the unexpected findings in the renal denervation study, the major objective of the four simulations below was to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms that enhance renal excretory function and contribute to the sustained lowering of blood pressure during prolonged activation of the baroreflex. All simulations were run for 5 weeks, which was the minimum amount of time necessary for sodium balance to be achieved and for all other variables to reach a steady-state under the different conditions.

1. Baroreflex activation under control conditions

To establish control responses, the simulation depicting the normal responses to carotid baroreflex activation in Figure 1 was extended from 1 to 5 weeks (blue solid lines in Figure 2). In essence, all measured variables illustrated in Figure 1 were stable after 1 week of baroreflex activation. More specifically, Figures 2a and 2b clearly demonstrate that MAP remained at the low level achieved at the end of week one and that sodium balance was maintained thereafter. Figure 2n shows that after day 1, plasma levels of angiotensin II remained at levels slightly lower than control despite the marked reduction in MAP. Additionally, there were no further changes in the reduced values for heart rate or plasma NE concentration indicated in Figure 1 from weeks 1-5 of baroreflex activation. Model predictions for variables not measured in experimental studies follow:

After activation of the baroreflex, there was an abrupt decrease in global sympathetic outflow and renal sympathetic nerve activity that was sustained throughout the 5 weeks of baroreflex activation. Both decreased ~ 46%.

Total peripheral resistance (Figure 2c), the difference between MAP and right atrial pressure divided by cardiac output, was reduced substantially (24%) after 5 weeks of baroreflex activation. Reflecting the fall in global sympathetic activity, most of the fall in total peripheral resistance occurred during the initial days of baroreflex activation.

Most of the increase in total sodium mass (Figure 2d) occurred during days 1-2 of baroreflex activation, corresponding to the period of greatest sodium retention (Figure 2b). Under steady-state conditions, total sodium mass increased ~ 15%.

As expected, extracellular fluid volume (Figure 2e) and plasma volume (Figure 2f) increased along with total sodium mass. However, there was a disproportionate increase in plasma volume (to 132% of control) relative to extracellular fluid volume (to 114 % of control) as a result of the increase in vascular compliance associated with sympathoinhibition.

Both right (Figure 2g) and left atrial pressures increased modestly, reflecting the increase in plasma volume.

As atrial pressure is a primary stimulus for ANP secretion, plasma ANP concentration (Figure 2h) increased ~ 3-fold during baroreflex activation.

Renal venous pressure (Figure 2i) increased modestly (from 8 to 12 mmHg), owing to an increase in systemic venous pressure. In the model, there is an inverse relationship between sympathetic activity and total capacity of the venous circulation. Therefore, the decrease in global sympathetic outflow in this simulation led to an increase in venous capacity. The small increase in renal venous pressure was a result of the fractional increase in plasma volume exceeding the fractional increase in total venous capacity.

There was an initial decrease in renal interstitial fluid pressure (Figure 2j) that gradually returned to levels slightly above control over the 5 weeks of activation. In the model, renal interstitial fluid pressure is determined by the sum of the effects of renal perfusion pressure and renal venous pressure. Renal venous pressure affects renal interstitial fluid pressure only when renal venous pressure rises above control levels, such as in the present simulation. Despite the increase in renal venous pressure, there was only a small increase in renal interstitial fluid pressure because of the substantial fall in MAP.

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) decreased by ~40% (Figure 2k). The net filtration pressure equals glomerular capillary hydrostatic pressure (PGC) minus glomerular capillary colloid osmotic pressure minus proximal tubular pressure. PGC is computed as the difference between arcuate artery pressure and the pressure drop across the afferent arteriole, which in turn is calculated as the ratio of renal blood flow and afferent arteriole conductance. The simulation indicates that the major contributor to the decrease in GFR during baroreflex activation is the reduction in renal perfusion pressure.

Fractional reabsorption of sodium in the proximal tubule (PTfact) decreased progressively to 62% of control by week 5 of baroreflex activation (Figure 2l). In the model, PTFract increases in response to angiotensin II and to neurally-induced activation of alpha adrenergic receptors. PTFract is inhibited by increases in renal interstitial fluid pressure and circulating levels of ANP. This simulation indicates that diminished renal nerve activity has a powerful natriuretic effect that partially offsets the reduced sodium delivery to the proximal tubule due to the fall in GFR. The increase in plasma ANP concentration also contributes modestly to this natriuretic effect. Additionally, ANP inhibits sodium reabsorption in the collecting duct.

On day 1 of baroreflex activation, sodium flow at the macula densa (Figure 2m) decreased sharply concomitant with the abrupt fall in GFR. Subsequently, despite the sustained reduction in GFR, sodium flow at the macula densa returned toward control levels in association with the fall in PTFract. Nonetheless, a small decrease (~17%) in sodium flow at the macula densa persisted after 5 weeks of baroreflex activation.

Renin secretion and, therefore, plasma angiotensin II concentration (Figure 2n) increased during day 1 of baroreflex activation in parallel with the greatest decrease in sodium flow to the macula densa. However, despite the sustained, modest reduction in sodium delivery at the macula densa, there was no persistent increase in renin secretion because this stimulus for renin secretion was counteracted by diminished activation of beta adrenergic receptors on the juxtaglomerular cells attendant with suppression of renal sympathetic nerve activity.

FIGURE 2.

Simulations for 5 weeks of carotid baroreflex activation. Blue solid line, control conditions; Red dotted line, without suppression of renal adrenergic activity; Orange dashed line, without neurohormonal influences on renal excretory function; Grey long dashed line, without neurohormonal and renal venous pressure influences on renal excretory function. a. MAP; b. urinary sodium excretion (UNaV); c. total peripheral resistance (TPR); d. total sodium mass (Na mass); e. extracellular fluid volume (ECFV); f. plasma volume (PV); g. right atrial pressure (RAP); h. plasma ANP concentration; i. renal venous pressure (RVP); j. renal interstitial fluid pressure (RIFP); k. glomerular filtration rate (GFR); l. fractional reabsorption of sodium in proximal tubule (PTFract); m. sodium flow at the macula densa (MD Na Flow); n. plasma angiotensin II concentration.

In summary, this simulation indicates that a major mechanism that normally permits sodium balance at a low MAP during baroreflex activation is suppression of renal sympathetic nerve activity. Suppression of renal sympathetic nerve activity increases renal excretory function in two ways: First, reduced activation of alpha adrenoceptors at the proximal tubule inhibits proximal tubular reabsorption of sodium despite low GFR. Second, diminished activation of beta adrenergic receptors inhibits renin secretion and offsets the influence of reduced sodium delivery at the macula densa to increase circulating levels of the powerful antinatriuretic hormone angiotensin II. Other natriuretic factors have been identified, such as ANP. The influence of hormonal mechanisms will be demonstrated in the penultimate simulation below.

2. Baroreflex activation without suppression of renal adrenergic activity

Contrary to our expectations, experimental studies clearly indicated that the renal nerves are not essential for permitting a sustained fall in blood pressure during prolonged baroreflex activation.3 Therefore, to determine the mechanisms independent of suppression of renal sympathetic nerve activity that may contribute to increased renal excretory function during baroreflex activation we clamped the activity of renal alpha and beta adrenergic receptors at control levels, and repeated the 5 week control simulation. Because we clamped renal adrenergic activity at control levels rather than at zero, this simulation does not exactly mimic the more drastic changes in renal function associated with complete elimination of the renal nerves following renal denervation. Following renal denervation, there are long-term compensations in the renal handling of sodium that are not completely understood and, therefore, responses that cannot be modeled.10 For example, in QHP2008, completely eliminating any influence of the renal nerves on renal alpha and beta receptors leads to a reduction in MAP of 12 mmHg. In contrast, there is no significant chronic reduction in MAP following bilateral renal denervation in dogs.3

The simulation illustrating responses to baroreflex activation while clamping renal alpha and beta adrenergic receptors at control levels is illustrated by the red dotted lines in Figure 2. In the absence of a decrease in renal adrenergic stimulation, there was greater sodium retention (Figure 2b) and a somewhat smaller sustained reduction in MAP (Figure 2a) during prolonged baroreflex activation, compared to control conditions (blue solid lines). These findings are consistent with our previous experimental findings during baroreflex activation in dogs with and without renal denervation. Although not illustrated in Figure 2, heart rate and plasma NE concentration decreased to the same levels indicated in the control simulation. Additional responses to prolonged baroreflex activation are the following.

There were similar decreases in global sympathetic activity in the two initial simulations, although renal adrenergic activity could not decrease when renal adrenergic receptors were clamped at control levels.

Reflecting the small difference in MAP (~ 4 mmHg) between the two simulations, the decrease in total peripheral resistance (Figure 2c) was somewhat less pronounced during renal adrenergic blockade.

In the absence of suppression of renal adrenergic activity, the increase in total sodium mass (Figure 2d) was twice as great as that achieved in the control simulation.

As expected from the increase in total sodium mass, there were greater increases in extracellular fluid volume (Figure 2e) and plasma volume (Figure 2f) than under control conditions. However, in contrast to the control simulation, the additional increase in extracellular fluid volume exceeded that of plasma volume, indicating a disproportional increase in interstitial fluid volume relative to plasma volume.

Right (Figure 2g) and left atrial pressures increased more than in the control simulation.

Reflecting the higher atrial pressures, plasma ANP concentration (Figure 2h) increased more in this than in the control simulation.

Along with the somewhat larger increase in plasma volume, there was a small additional increase in renal venous pressure (Figure 2i) when renal adrenergic activity was clamped at control levels compared to when renal adrenergic receptors were able to respond to reduced renal nerve activity.

After an initial decrease associated with the fall in renal perfusion pressure, renal interstitial fluid pressure (Figure 2j) increased to levels above control. The increase in renal interstitial fluid pressure paralleled the increase in renal venous pressure and was somewhat greater than the increase observed in the control simulation. As a result, the natriuresis attributed to the rise in renal interstitial fluid pressure was greater during adrenergic blockade than in the control simulation.

Once again GFR (Figure 2k) decreased substantially (~30%), but the fall was less pronounced than in the control simulation (~ 40%). This reflected the difference in glomerular capillary hydrostatic pressure between the two conditions due to the relatively greater increase in renal perfusion pressure during constant adrenergic activity.

In the absence of the natriuretic effect of renal sympathoinhibition, PTFract (Figure 2l) increased during the initial days of baroreflex activation before falling to below control levels. The final steady-state reduction in PTFract (~29%) was substantially smaller than in the control simulation (~38%). when there was reduced neural activation of adrenergic receptors With stimulation of renal adrenoceptors clamped at control levels, increases in both plasma ANP concentration and renal interstitial fluid pressure largely accounted for the decrease in PTFract.

The initial decrease in sodium flow at the macula densa (Figure 2m) in response to baroreflex activation was more pronounced and sustained during adrenergic blockade than in the control simulation when suppression of renal sympathetic nerve activity reduced PTFract. Despite this early difference, sodium flow at the macula densa eventually returned toward control levels as the natriuretic effects of ANP and renal interstitial fluid pressure intensified. Under steady-state conditions, reductions in sodium flow at the macula densa were modest and similar in the two simulations irrespective of the level of renal adrenergic stimulation.

Because stimulation of renal beta adrenergic receptors was clamped at control levels the juxtaglomerular cells could not respond appropriately to the fall in renal sympathetic nerve activity. Consequently, renin secretion was elevated throughout the 5 weeks of baroreflex activation, especially during initial days when sodium flow to the macula densa was substantially reduced. At the end of the 5-week period of baroreflex activation, there was a 28% increase in renin secretion when activation of renal adrenergic receptors was fixed, compared to a 2% decrease in the control simulation when diminished activation of beta adrenergic receptors offset the macula densa stimulus for renin release in the control simulation. However, this difference in renin secretion between the two simulations was not reflected in the plasma levels of angiotensin II (Figure 2n) because of the greater volume of distribution of renin when renal adrenergic receptors were fixed at control levels. Consequently, under steady-state conditions, plasma levels of angiotensin II were similar in the two simulations.

In summary, the initial two simulations indicate that when stimulation of renal adrenergic receptors fails to decrease during prolonged activation of the baroreflex, such as after renal denervation, there is an inordinate degree of fluid retention. In turn, this leads to greater increases in plasma ANP concentration and renal interstitial fluid pressure. The contribution of these natriuretic mechanisms to increased renal excretory function intensifies, allowing the maintenance of sodium balance at a substantially reduced arterial pressure. However, the compensation is incomplete as the degree of pressure reduction is somewhat attenuated and occurs at the expense of excess fluid retention.

3. Baroreflex activation without neurohormonal influences on renal excretory function

Because the initial two simulations suggested that ANP may play a significant role in promoting natriuresis during baroreflex activation, the next simulation was originally designed to determine the importance of this hormonal mechanism in increasing renal excretory function and lowering blood pressure. However, in preliminary simulations (not shown), we found that when the renal adrenergic activity and plasma ANP concentration were clamped at control levels during baroreflex activation, plasma levels of angiotensin II and aldosterone decreased to below control levels, confounding interpretation of a simulation focused on ANP. Therefore, in the next simulation (orange dashed lines), the plasma levels of ANP, angiotensin II, and aldosterone, along with renal adrenergic receptors, were clamped at normal levels during prolonged baroreflex activation. Thus, the intent of the third simulation was to determine whether prolonged baroreflex activation could chronically reduce arterial pressure in the absence of an increase in renal excretory function induced by the renal nerves and hormones know to play an important role in long-term control of arterial pressure.

Surprisingly, even under these conditions there was a sustained reduction in MAP (Figure 2a) during baroreflex activation, although the fall in MAP was noticeably less (~15 mmHg) than in the control simulation (~23 mmHg). Another prominent difference during neurohormonal blockade was that sodium retention (Figure 2b) was more protracted and pronounced than in the previous simulations. Reductions in heart rate and plasma NE concentration were identical to those in the first two simulations. Additional responses to prolonged baroreflex activation are the following.

Global sympathetic activity decreased to the same extent as in the two previous simulations.

Reductions in total peripheral resistance (Figure 2c) were similar to those in the initial simulations.

There was an appreciably greater increase in total sodium mass (Figure 2c) than in the previous two simulations.

Consistent with the increase in total sodium mass, increases in extracellular fluid volume (Figure 2e) and plasma volume (Figure 2f) exceeded those achieved with renal adrenergic blockade alone. Furthermore, the disproportionate increase in extracellular fluid volume relative to plasma volume intensified.

Right (Figure 2g) and left atrial pressures increased more than in the two previous simulations.

Because plasma concentrations of hormones were clamped at control levels, there were no changes in plasma ANP concentration (Figure 2h) during baroreflex activation.

Renal venous pressure (Figure 2i) increased more than in the previous simulations as the increase in plasma volume continued to overfill the capacity of the circulatory system.

There was a substantial increase (~25%) in renal interstitial fluid pressure (Figure 2j) because of the relatively large increase in renal venous pressure.

GFR (Figure 2k) decreased (~ 26%) but to a lesser extent than in the previous simulations. The smaller fall in GFR was due to the additional increase in renal perfusion pressure and the attendant increase in glomerular capillary pressure.

Changes in PTFract (Figure 2l) were similar to those illustrated in the second simulation representing renal adrenergic blockade alone. However, because neurohormonal mechanisms were clamped at control levels, the chronic decrease in PTFract was due exclusively to the rise in renal interstitial fluid pressure.

In contrast to the two previous simulations, the smaller fall in the filtered load of sodium was completely counterbalanced by the fall in PTFract, resulting in complete restoration of sodium delivery at the macula densa (Figure 2m) to control levels.

Because plasma concentrations of hormones were clamped at control levels, there were no changes in plasma angiotensin II concentration (Figure 2n) during baroreflex activation.

In summary, the design of this simulation rendered the major neurohormonal mechanisms incapable of exerting effects on renal excretory function. Still, sodium balance was still achieved at a reduced arterial pressure, although in association with marked fluid retention. This simulation exposes yet another perhaps unappreciated natriuretic force - increased renal interstitial fluid pressure. By impairing sodium reabsorption, increased renal interstitial fluid pressure may be especially important in attenuating sodium reabsorption in edematous pathophysiological states associated with increased venous pressure.

4. Baroreflex activation without neurohormonal and renal venous pressure influences on renal excretory function

The last simulation (grey long dashed lines) focuses on the importance of still another natriuretic mechanism in permitting sustained reductions in arterial pressure during prolonged activation of the baroreflex. This simulation depicts the quantitative importance of increased renal venous pressure, along with neurohormonal mechanisms, in increasing renal excretory function during prolonged baroreflex activation. This simulation was achieved by clamping neurohormonal mechanisms at control levels and preventing renal venous pressure from increasing renal interstitial fluid pressure.

Most significantly, this simulation indicates that there is an inordinate amount of sodium retention (Figure 2b) during sustained activation of the baroreflex when all of the above natriuretic mechanisms are incapable of increasing renal excretory function. In fact, sodium balance occurred only after 4 weeks of baroreflex activation. Moreover, sodium balance was achieved only in association with a substantial increase in MAP (Figure 2a) to values only modestly lower than control levels (5 mmHg). Reductions in heart rate and plasma NE concentration were identical to those in the first three simulations. Additional responses to prolonged baroreflex activation are the following.

Global sympathetic outflow decreased to the same extent as in the three previous simulations.

As in the other simulations, there was a sustained decrease in total peripheral resistance (Figure 2c) throughout the 5 weeks of baroreflex activation.

There was an enormous increase in total sodium mass (Figure 2d), which greatly exceeded the sodium retention exhibited in the other simulations. This culminated in an increase in total sodium mass to 167 % of control.

There were further increases in extracellular fluid (Figure 2e) and plasma volume (Figure 2f). After 5 weeks of baroreflex activation, the corresponding values were 159% and 157% of control values.

Right and left atrial pressures increased substantially to values appreciably greater than in the previous simulations.

Because plasma concentrations of hormones were clamped at control levels, there were no changes in plasma ANP concentration (Figure 2h) during baroreflex activation.

Renal venous pressure (Figure 2i) increased considerably but, by the design of this simulation, was unable to increase renal interstitial fluid pressure.

Controlled only by renal perfusion pressure, renal interstitial fluid pressure (Figure 2j) decreased initially and then slowly returned to control levels in parallel with the progressive rise in MAP.

After an initial abrupt fall, GFR (Figure 2k) gradually increased to control levels due to the gradual increase in renal perfusion pressure and the attendant rise in glomerular capillary pressure.

In marked contrast to the previous simulations, PTFract (Figure 2l) actually increased above control levels throughout much of 5 weeks of baroreflex activation due in large part to the fall in renal interstitial fluid pressure.

After a substantial initial fall, sodium flow at the macula densa (Figure 2m) returned to control levels in parallel with the progressive increase in GFR.

Because plasma concentrations of hormones were clamped at control levels, there were no changes in plasma angiotensin II concentration (Figure 2n) during baroreflex activation.

In summary, this simulation emphasizes the importance of natriuretic mechanisms in permitting sustained reductions in arterial pressure during prolonged activation of the baroreflex. When neurohormonal and hemodynamic influences are prevented from increasing renal excretory function, sustained baroreflex-mediated reductions in arterial pressure are trivial despite persistent reductions in total peripheral resistance.

CONCLUSIONS

An important objective of this study was to use computer simulations to better understand the integrative physiological relationships associated with prolonged baroreflex activation and attendant suppression of central sympathetic outflow. In some cases, causal relationships were not obvious intuitively and, in others, they were not readily testable in experimental studies. More specifically, because of the controversial nature of the findings observed in response to baroreflex activation following renal denervation, simulations were conducted using an established mathematical model of human physiology to elucidate the integrative mechanisms that are truly critical in mediating chronic reductions in blood pressure in response to sustained activation of the carotid baroreflex. The simulations closely matched empirical data, providing important validation of the mathematical model. The simulations predicted that baroreflex-mediated suppression of renal sympathetic nerve activity chronically increases renal excretory function and, therefore, plays an important role in permitting sodium balance at sustained reductions in blood pressure. This sustained natriuretic effect is achieved by direct actions on proximal tubular sodium reabsorption and by indirect effects on sodium reabsorption as result of suppression of renin secretion. Additionally, hormonal and hemodynamic mechanisms also participate in this natriuretic response, and their contribution to chronic lowering of arterial pressure intensifies at the expense of excessive fluid retention when there is impaired suppression of renal adrenergic activity, such as after renal denervation. Most notable of the non-neural contributions to sodium excretion are those made by increased plasma levels of ANP and increased renal interstitial fluid pressure. Because of the redundant nature of these natriuretic mechanisms, their ability to chronically increase renal excretory function is manifested most distinctly only after their combined contributions are eliminated. If this is achieved, the ability of the baroreflex to chronically lower arterial pressure is greatly diminished despite its sustained actions to decrease total peripheral resistance.

Predictions from mathematical models are only as accurate as the empirical data upon which they are based. As physiological models become more complex, there is the necessity to integrate variables and relationships that often times escape empirical measurement. Thus, models are limited in their ability to provide exhaustive quantitative description of all physiological mechanisms. Nonetheless, numerical simulations and models lead to integrative insight and testable hypotheses. Consequently, the validity of model predictions is dependent on innumerable cycles of experimentation and model refinement, such as have occurred during the 40 year evolution of QHP2008. For example, the current simulations are based on the hypothesis that prolonged baroreflex activation leads to chronic suppression of renal sympathetic nerve activity. However, at present, this critical measurement has not been made in experimental studies. Additionally, our current experimental studies indicate that GFR does decrease significantly during prolonged baroreflex activation; however, the predicted reductions in GFR illustrated in the simulations are considerably greater than those observed experimentally during comparable or smaller reductions in renal perfusion pressure 11;12. Thus, while many of the hemodynamic, neurohormonal and urinary electrolyte excretion responses predicted by the model are very similar to observed experimentally, there is some quantitative disparity between the theoretical and empirical findings relating to the specific renal mechanisms that control sodium excretion during activation of the baroreflex. Additional cycles of experimentation and model refinement will be required to more precisely define the specific renal mechanisms that contribute to sodium homeostasis and long-term control of arterial pressure during sustained alterations in sympathetic activity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Drs. Robert Hester and Thomas Coleman for their critical reading of this manuscript.

Sources of funding: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Grant HL-67501 and American Heart Association Grant 0830416N

ABBREVIATIONS

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- ANP

atrial natriuretic peptide

- PTFract

fractional reabsorption of sodium in proximal tubule

- NE

norepinephrine

- PRA

plasma renin activity

REFERENCES

- 1.Lohmeier TE, Irwin ED, Rossing MA, Serdar DJ, Kieval RS. Prolonged activation of the baroreflex produces sustained hypotension. Hypertension. 2004;43:306–311. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000111837.73693.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lohmeier TE, Dwyer TM, Hildebrandt DA, Irwin ED, Rossing MA, Serdar DJ, Kieval RS. Influence of prolonged baroreflex activation on arterial pressure in angiotensin hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;46:1194–1200. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000187011.44201.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lohmeier TE, Hildebrandt DA, Dwyer TM, Barrett AM, Irwin ED, Rossing MA, Kieval RS. Renal denervation does not abolish sustained baroreflex-mediated reductions in arterial pressure. Hypertension. 2007;49:373–379. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000253507.56499.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lohmeier TE, Dwyer TM, Irwin ED, Rossing MA, Kieval RS. Prolonged activation of the baroreflex abolishes obesity-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:1307–1314. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.087874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lohmeier TE, Hildebrandt DA, Dwyer TM, Iliescu R, Irwin ED, Cates AW, Rossing MA. Prolonged Activation of the Baroreflex Decreases Arterial Pressure Even During Chronic Adrenergic Blockade. Hypertension. 2009;53:833–838. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.128884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guyton AC. Arterial Pressure and Hypertension. Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lohmeier TE, Drummond HA. The baroreflex in the pathogenesis of hypertension. In: Lip GYH, Hall JE, editors. Comprehensive Hypertension. Elsevier; Phyladelphia, Pa: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrett CJ, Guild SJ, Ramchandra R, Malpas SC. Baroreceptor denervation prevents sympathoinhibition during angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;46:168–172. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000168047.09637.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guyton AC, Coleman TG, Granger HJ. Circulation: overall regulation. Annu Rev Physiol. 1972;34:13–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.34.030172.000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lohmeier TE, Hildebrandt DA, Warren S, May PJ, Cunningham JT. Recent insights into the interactions between the baroreflex and the kidneys in hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R828–R836. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00591.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mizelle HL, Montani JP, Hester RL, Didlake RH, Hall JE. Role of pressure natriuresis in long-term control of renal electrolyte excretion. Hypertension. 1993;22:102–110. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.22.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reinhardt HW, Corea M, Boemke W, Pettker R, Rothermund L, Scholz A, Schwietzer G, Persson PB. Resetting of 24-h sodium and water balance during 4 days of servo-controlled reduction of renal perfusion pressure. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H650–H657. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.2.H650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.