Abstract

Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) activates two major G-protein arms, Gsα and Gq leading to initiation of down-stream signaling cascades for survival, proliferation and production of thyroid hormones. Antibodies to the TSH receptor (TSHR-Abs), found in patients with Graves’ disease, may have stimulating, blocking, or neutral actions on the thyroid cell. We have shown previously that such TSHR-Abs are distinct signaling imprints after binding to the TSHR and that such events can have variable functional consequences for the cell. In particular, there is a great contrast between stimulating (S) TSHR-Abs, which induce thyroid hormone synthesis and secretion as well as thyroid cell proliferation, compared to so called “neutral” (N) TSHR-Abs which may induce thyroid cell apoptosis via reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation.

In the present study, using a rat thyrocyte (FRTL-5) ex vivo model system, our hypothesis was that while N-TSHR-Abs can induce apoptosis via activation of mitochondrial ROS (mROS), the S-TSHR-Abs are able to stimulate cell survival and avoid apoptosis by actively suppressing mROS. Using fluorescent microscopy, fluorometry, live cell imaging, immunohistochemistry and immunoblot assays, we have observed that S-TSHR-Abs do indeed suppress mROS and cellular stress and this suppression is exerted via activation of the PKA/CREB and AKT/mTOR/S6K signaling cascades. Activation of these signaling cascades, with the suppression of mROS, initiated cell proliferation. In sharp contrast, a failure to activate these signaling cascades with increased activation of mROS induced by N-TSHR-Abs resulted in thyroid cell apoptosis.

Our current findings indicated that signaling diversity induced by different TSHR-Abs regulated thyroid cell fate. While S-TSHR-Abs may rescue cells from apoptosis and induce thyrocyte proliferation, N-TSHR-Abs aggravate the local inflammatory infiltrate within the thyroid gland, or in the retro-orbit, by inducing cellular apoptosis; a phenomenon known to activate innate and by-stander immune-reactivity via DNA release from the apoptotic cells.

Keywords: Thyrocyte, TSH receptor, Antibodies, ROS-signaling, Apoptosis, Proliferation

1. Introduction

The TSH receptor (TSHR) is a major antigen in human autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD). Activation of the TSHR recruits G proteins of all four subfamilies (Gs, Gi/o, Gq/11 and G12/13) and we now recognize TSH receptor antibodies (TSHR-Abs) in patients with AITD that may be “stimulating”, “blocking”, or “neutral” in their influence on the TSHR, especially in patients with Graves’ disease. Stimulating TSHR-Abs (S-TSHR-Abs) induce thyroid epithelial cell proliferation via both Gs and Gq/11 coupled signaling pathways while “blocking” antibodies (B-TSHR-Abs) inhibit the action of TSH but may also act as weak agonists. In contrast, the antibody species poorly named “neutral” TSHR-Abs (N-TSHR-Abs) are unable to activate cAMP via Gsα but are capable of initiating a cascade of signaling imprints for programmed cell death [1].

The conformational binding site for S-TSHR-Abs and some B-TSHR-Abs mainly involves the leucine rich repeat region (LRRR) of the TSHR ectodomain [2]. In contrast, the linear epitopes recognized by N-TSHR-Abs are often confined to the cleaved region of the ectodomain (residues 316–366) [1]. The frequency of N-TSHR-Abs in GD has been reported as ranging from 30 to 90%, based on linear epitope binding or known amino acid residues [1,3–9]. Although the presence of these neutral antibodies in Graves’ disease is well known, their pathophysiological significance remains poorly characterized and their presence is not routinely measured in the clinical situation. However, we have previously shown that N-TSHR-Abs may induce apoptosis in association with the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and stress signaling [1]. ROS are highly reactive molecules induced by partially reduced forms of oxygen resulting from cellular metabolism. They include hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radicals (OH0), superoxide anions () and lipid peroxides [10]. Antioxidant systems defend cells from ROS-induced cellular damage and, under physiological conditions, a balance between oxidant and antioxidant exists. But such a balance is not always achieved and oxidative damage is believed to contribute to a variety of diseases including cardiovascular, neurodegenerative and neoplastic diseases and has also been implicated in thyrotoxic myopathy, thyroid cardiomyopathy and Graves’ orbitopathy [11–14]. In line with the evidence for ROS activation in extrathyroidal Graves’ disease, evaluation of human cellular defense systems (oxidant vs. antioxidant) in thyroid tissue from Graves’ disease patients undergoing thyroidectomy has also revealed increased levels of free radicals and their scavengers compared to normal thyroid [15].

Although human monoclonal N-TSHR-Abs are unavailable to probe their actions we have been able to utilize hamster and mouse N-TSHR-Abs to dissect their potential roles in thyrocyte signaling events resulting in apoptosis via activation of mitochondrial ROS (mROS). These studies have revealed that in contrast to neutral antibodies the S-TSHR-mAbs are able to prevent and rescue cells from apoptosis by suppressing ROS and that these different species of TSHR-Ab utilize distinct signaling cascades. While S-TSHR-Abs activate the cAMP/PKA/CREB/AKT signaling cascade which is instrumental in the cell survival decision, the N-TSHR-Abs initiate the ROS/stress/apoptotic signaling cascade which can orchestrate overt intrathyroidal inflammatory reactions.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Study subjects

GD was defined as increased thyroid hormone levels and suppressed serum TSH in patients with diffuse glands and the presence of TSHR Abs. Purified IgGs from selected serum samples from 5 untreated adult patients with GD and 3 healthy individuals were used for ROS and apoptosis assays. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and controls who participated in the present study.

2.2. Cell culture and treatments

Synchronized FRTL-5 rat thyroid cells were used as the model system [2] [16,17]. Cells were grown and maintained as we described recently [2]. Before any stimulation experiments, synchronized cells were made quiescent by starvation in bovine calf serum-free basal medium (modified Ham’s F12) containing 0.3% BSA for 2 d [2]. Before treatments, medium was discarded from the 60-mm culture dishes, and the cells were washed three times with a fresh medium containing Hanks’ balanced salt solution (Life Technologies, Inc. Laboratories, Grand Island, NY).

2.3. Small molecules inhibitors/activators and TSHR antibodies

MnTBAP, DPI, YCG were purchased from Calbiochem (EMD, Millipore, MD) and SOD, Rotenone and Antimycin-A were from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Two stimulating mAbs, one from human (M22) and one from hamster (MS1) were used to treat FRTL-5 cells. Three neutral mAbs, one from mouse (RSR4) and 2 from hamster (IC8 and Tab-16), were used for the treatments. Both M22 and RSR4 mAbs were kindly supplied by Dr. B. Rees Smith (RSR Ltd., Cardiff, Wales, UK).

2.4. Immunostaining of different signaling molecules in thyrocytes

Immunohisto-chemistry (IHC) was performed according to described protocols by Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Briefly, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 90% methanol and blocked for 1 h in blocking buffer. Cells were then incubated with specific antibodies diluted in blocking buffer left overnight in cold room with gentle shaking. After washing, incubated with fluorescent conjugated secondary antibodies for 1–2 h with appropriate dilution, washed thrice in PBS and mounted with Vectashield mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) and visualized immediately under digital and/or confocal microscopy or both.

2.5. Confirmation of signaling molecules by immunoblots

Immunoblots were performed as described [1,2]. Following pathway phospho-specific Abs were used: Akt (Ser473), mTOR (Ser2448), S6K (Thr389), PKA-C (Thr197), CREB (Ser133), PKCζ/l (Thr410/403), c-Raf (Ser338), MEK1/2 (Ser217/221), ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), p90 ribosomal kinase (p90 RSK, Ser380), ELK (Ser383), p38 (Thr202/Tyr204), ATF-2 (Thr 71), and NF-κB (p65, Ser276) (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). Mouse mAb to β-actin and unrelated control mAbs (IgG2, κ-chain) were from Sigma and BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ), respectively. Monoclonal Abs to HSP60 and HSP70 were from StressMarq, Biosciences Inc. (Victoria, Canada). Monoclonal Ab that recognizes MnSOD was from Epitomics (Burlingame, CA).

2.6. Apoptotic assays

Synchronized FRTL-5 cells were grown as described and cultured with increasing concentrations of N-mAbs. Annexin V with propium iodide (PI) assay kit from BD Biosciences was used to determine apoptotic cells. In the apoptosis assays, we extended the induction time by changing to new medium containing Ab on day 3 and observed them microscopically every day. Apoptosis became apparent on day 5. These cells were trypsinized and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated annexin V with PI according to the manufacturer’s protocols. To confirm apoptosis being induced either on adherent or on trypsinized live FRTL-5 cells, both microscopy and FACS assays were used for these treated cells [18]. To determine caspase activity, FAM caspase assay kit was used to detect active caspases. The methodology was based on a Fluorometric Inhibitor of Caspases (FLICA) and was performed according to the instructions provided with the kit (Imgenex, Corp., San Diego, CA).

2.7. Fluorometric detection of ROS by different fluorescent dyes

These assays, H2DCFDA (Life technologies, Invitrogen), dihydrorhodamine (H2R123, AnaSpec Inc., Fremont, CA), and MitoSOX Red (mitochondrial superoxide indicator, Invitrogen) oxidize a nonfluorescent probe to a fluorescent one that is detected by spectrofluorometry [18]. Briefly, synchronized adherent cells were loaded with 50 μm fluorescent dyes by incubating them at 37 °C for 15 min. Cells were then washed twice with HBSS and stimulated with Abs or H2O2 for the indicated time in the incubator. Cells were washed again with PBS and harvested with trypsin. After washing twice, cells were lysed by ultrasonication, centrifuged, and the supernatants analyzed by a spectrofluorometer (Coulter, Miami, FL).

2.8. Detection of mitochondrial ROS (mROS) by MitoSOX red dye

Both live fluorometric and live imaging analyses were performed [18]. In brief, after incubating cells with mROS fluorescent dye (Invitrogen) in warm HBSS at 37 °C for 15 min, loaded cells were washed twice with HBSS and treated them with different chemicals and antibodies or TSH in the presence of basal medium for indicated times. Fluorometric reading at different time points were taken in the buffer HBSS after washing cells twice with the same buffer. Live images were also taken under microscope with low power resolution (20× lens, Nikon). Delta-T dishes were used for live-imaging at a higher resolution (60×). Cells were grown, synchronized and starved. After treatments, cells were washed twice with warm HBSS buffer, and visualized in a fresh basal medium under microscope (60× lens, Nikon) with oil immersion.

2.9. Reproducibility of results

All assays were independently performed at least three times unless otherwise indicated. In cases of immunostaining, live-imaging and immunoblots, one representative experiment was shown.

2.10. Statistical analysis

The paired t test was used to evaluate the significance of differences in means for continuous variables using StatView software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). A p value of ≤0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. Data are presented as the Mean ± SD.

3. Results

3.1. Defining ROS signaling induced by N-TSHR-Abs

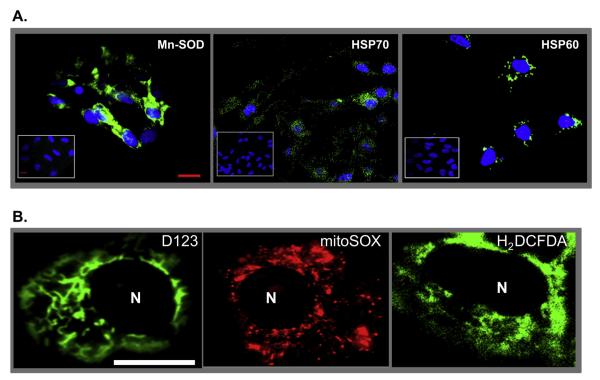

Our earlier observations indicated that cell stress induced by N-TSHR-Abs is a key regulatory component involved in thyrocyte apoptosis via production of ROS. When thyroid cells were exposed to monoclonal N-TSHR-Ab for 3 days (1 μg/ml), there was enhanced immunostaining of both mitochondrial (Mn-SOD and HSP60) and endoplasmic reticulum stress markers (HSP70) (Fig. 1A) compared to control antibody treated cells (Fig. 1A, inset) confirming our previous data obtained by proteomic array [1]. Microscopic analysis of green fluorescent staining of treated live cells demonstrated cytoplasmic patterns with perinuclear condensations of both H2DCFDA and H2R123 dyes emphasizing mitochondrial ROS (mROS) induction with further confirmation using MitoSOX red which is a mitochondrial superoxide indicator. Furthermore, H2R123/H2DCFDA (green) and mROS (red) were co-localized (Fig. 1B) clearly indicating that each of these dyes stained mitochondrial ROS.

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemistry and live imaging of stress markers in thyrocytes. Panel A: Immunohistochemical detection of stress-induced proteins and ROS. Rabbit polyclonal primary antibody was used to detect Mn-SOD in N-TSHR-mAb (IC8 1ug/ml) treated (24 h) FRTL-5 thyrocytes. The N-TSHR-mAb also induced heat shock proteins (HSP) 70 and 60 as detected by mAbs against each protein. HSP70 and 60 are normally localized within the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria, respectively. Such proteins were not induced by an isotype control mAb (see insets). Scale bar on images corresponds to 20micron. Panel B: Live imaging of ROS in thyrocytes using three independent dyes. Cells were treated for 24 h with N-TSHR-mAb (IC8 1ug/ml). Representative images of both D123 and H2DCFDA showed diffuse staining throughout the cell cytoplasm. Some perinuclear condensations were also documented. The distribution of staining patterns paralleled mitochondrial ROS (mROS). Nucleoli are indicated as N.

Further confirmation of mROS generation came from the use of specific mitochondrial inhibitors and activators in these cells in relation to N-TSHR-Ab induction of mROS (Supplementary Fig. 1C). Rotenone and antimycin A, inhibitors of mitochondrial membrane complexes II and III, induced mROS serving as positive controls along with H2O2 (panels G-I) while Mn-TBAP and superoxide dismutase (SOD), known inhibitors of mROS, inhibited the effect of the N-TSHR-Ab (panel D). DPI, an inhibitor of the NADPH oxidase system, also showed a significant reduction in mROS (panel F) and this indicated that mitochondrial NADPH oxidase was involved in the ROS induction.

3.2. Diversification of TSHR-Ab effects on thyroid cell apoptosis

To identify key effectors responsible for apoptosis induced by N-TSHR-Abs we examined total caspase activation and annexin V expression. Both caspase and annexin V were highly induced by N-TSHR-Ab as assessed by quantitative fluorometric assay in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A) confirming apoptosis as the mechanism for thyroid cell death and as seen by live cell-imaging (Fig. 2B). Although apoptosis involves either extrinsic or intrinsic signaling pathways this analysis did not indicate which was active.

Fig. 2.

Apoptosis induced by N-mAb but not by St-mAb or TSH. Panels A & B: Both total caspases and Annexin V assays indicated that N-mAb (IC8) was capable of inducing apoptosis via ROS induction. Dose-dependent induction of total caspases was confirmed by FLICA assay (Panel A). Staurosporine (STP) was used as a positive control for apoptosis. Neutral antibody induced total caspase activity was significantly enhanced compared to control antibody treated cells. Live-imaging analyses (Panel B) indicated activation of both mROS (red) and Annexin V (green). Representative images indicated co-localization of mROS (red) and Annexin V (green) by yellow color (connected arrow). Nuclear fragmentation was also observed in some apoptotic cells (arrow). Panels C & D: Suppression of mROS induced by S-TSHR-mAb (M22 1ug/ml) or TSH (1mU/ml) overtime. The peak level of suppression was noted on day 3 while N-TSHR-mAb (IC8) continued to activate mROS (Panel C). S-TSHR-mAb did not induce any apoptosis as there was no binding of Annexin V by live-imaging (Panel D) (lack of green) but cell proliferation was induced on day 3 as indicated in our previous study [2]. A few cells showed a minor induction of mROS (red; arrows). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Since the cAMP/PKA cascade is well known to induce a wide variety of effects on cellular organelles we hypothesized this would include important regulatory effects on thyroid cell apoptosis via mROS. Since TSH and S-TSHR-Abs activate cAMP/PKA, we hypothesized that they were capable of suppressing the mROS response to N-TSHR-Ab. We found that indeed both TSH and S-TSHR-Ab suppressed mROS induction as assessed by fluorometric assay (Fig. 2D) and live cell imaging (Fig. 3A). As expected, this suppression of mROS by S-TSHR-Ab prevented apoptosis induced by N-TSHR-Ab (Fig. 2E). These findings clearly suggested that cAMP/PKA generated by S-TSHR-Ab or TSH was capable of preventing apoptosis via suppression of mROS.

Fig. 3.

S-TSHR-mAb suppressed mROS production while N-TSHR-mAb induced mROS. Panel A: Live fluorometric analyses indicated that S-TSHR-mAb (M22) suppressed mROS (red) in a dose-dependent manner while N-TSHR-mAb (IC8) had the opposite effect (insets). Nucleoli were stained with live nuclear dye (Hoechst 33342). Panel B: Cyclic AMP (32 pmol/ml), IBMX (1 mM), Forskolin (10 μM), and TSH (1 mU/ml) suppressed significantly mROS induction by N-TSHR-mAb. Panel C: In contrast, PKA inhibitor (H89) induced mROS expression in a time dependent manner followed by apoptosis (not shown). Panel D: The S-TSHR-mAb (1ug/ml) suppressed mROS induction at different concentrations of PKA inhibitor. Panel E: The S-TSHR-mAb was also capable of rescuing cells from PKA inhibitor-induced thyrocyte apoptosis. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.3. Down-stream signaling is a negative regulator of mROS

In order to confirm the role of cAMP/PKA in the prevention of apoptosis via suppression of mROS we used specific PKA activators including IBMX, forskolin and TSH in addition to S-TSHR-Ab. Each of these suppressed the induction of mROS by N-TSHR-AB (Fig. 3B). Since we determined that cAMP/PKA is a major regulator of mROS expression we further examined the effect of specific PKA inhibition using H89 [2] which we found to activate constitutive mROS expression (Fig. 3C). With the inhibitor inducing mROS we found that S-TSHR-Ab was able to suppress both mROS (Fig. 3D) and apoptosis (Fig. 3E). These data again indicated that a balance between negative and positive regulators of mROS was a key to maintaining thyrocytes homeostasis.

3.4. S-TSHR-Abs sustain survival of thyroid cells via the PKA/CREB and AKT/mTOR/S6K signaling cascades

To define the important signaling molecules involved in the thyroid cell fate decision process we examined the major TSHR signaling pathways in TSH and antibody treated cells. Consistent with our earlier data using thyroid cells after 1 h of exposure [1,2] we detected increased PKA/CREB and AKT/mTOR/S6K activities with S-TSHR-Ab and TSH (Fig. 4A). By contrast only N-TSHR-Ab activated cRaf/MEK/ERK1/2 and p38 (Fig. 4A). At 24 h, most strikingly, N-TSHR-Ab failed to sustain the activity of many of its signaling molecules while the S-TSHR-Ab sustained much of its activity (Fig. 4B). In agreement with these observations, N-TSHR-Ab had no influence on CREB which was detected in the cell cytoplasm (Fig. 4C). In contrast, the S-TSHR-Ab induced a dynamic change in cytoplasmic vs. nuclear accumulation of phosphorylated CREB causing phosphorylated CREB to be accumulated mostly in the nucleus (Fig. 4C). These findings indicate that multiple signaling cascades sustained by S-TSHR-Abs are important in cell survival and proliferation.

Fig. 4.

Multiple phosphoproteins were detected by Immunoblot and immunohistochemistry. Panel A – Representative immunoblot showing activation of multiple signaling proteins. Activation of different signaling molecules was consistent with our earlier immunoblot studies (1,2). Panel B: Activated signals were inconsistent with time. The N-TSHR-mAb failed to maintain sustained activation of some important key signaling molecules while the S-TSHR-mAb and TSH demonstrated sustained activation of their signaling cascades. Importantly, the S-TSHR-mAb induced a sustained activation of AKT/mTOR/S6/ERK1/2 and PKA/CREB signaling molecules at 24 h. By contrast, the N-TSHR-mAb continued to activate a stress related signaling molecule p38 and failed to show sustained activities of AKT/mTOR/S6/ERK1/2 and PKA/CREB. C = Control mAb, S = S-TSHR-mAb (M22), TSH = thyroid stimulating hormone, N = N-TSHR-mAb (IC8). Panel C: Immunohistochemistry of phospho-CREB protein (Green) using an anti-phosphorylated CREB antibody revealed nuclear accumulation induced by S-TSHR-mAb not seen in N-mAb treated cells. Nucleus was stained with blue dye. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.5. Patients with Graves’ disease have antibodies capable of inducing thyroid cell death

To begin to explore whether Graves’ disease patients IgGs have the potential to induce cell death, we treated rat thyrocytes with IgG preparations from 5 patients and 3 healthy control individuals. The patient IgGs were all reactive with the TSHR and contained both N-TSHR-Abs and S-TSHR-Abs as described earlier [1]. mROS was measured with a live cell nuclear dye (Hoechst stains 33342). After 5 days, thyroid cells exposed to 2 of 5 Graves’ IgGs showed features of cell death with nuclear shrinkage and fragmentation (Fig. 5, GD-2 & -4) while none of the 3 healthy IgGs had a similar effects. The patient IgG treated cells subsequently demonstrated cell detachment confirming cellular death.

Fig. 5.

Representative views of ROS and apoptosis induced by human immunoglobulins (IgGs) from patients with Grave’ disease. Rat thyroid cells were treated twice with purified human IgG (10 μg/ml) on day 3 and day 5 of culture. They were examined daily and imaged on day 7 when loss of cells with apoptotic features appeared to begin. Induction of ROS was prominent in three patients (GD-1, -3 & -4) compared to two other patients (GD-2 &-5). Two patients (GD-2 & GD-4) showed loss of cells with apoptotic features of nuclear fragmentation while showing lower ROS staining (GD-2) while the other (GD-4) had loss of nuclear dye (Hoecst 33342) with a higher content of diffuse cytoplasmic ROS staining. IgG from patient GD-5 did not produce such effects and showed less ROS compared to even control IgG treated cells. Control = normal human IgG, GD1-5 are IgG preparations from 5 patients with Graves’ disease and positive TSR-Ab assay.

4. Discussion

The overall aim of the study was to define the signaling mechanisms illustrating how one TSHR antibody was able to induce thyrocyte apoptosis while another TSHR antibody was able to avert apoptosis and even prevent it. Such mechanisms must operate in autoimmune thyroid disease since patients with Graves’ disease not infrequently have a variety of TSHR-Abs including both N-TSHR-Abs and S-TSHR-Abs [1]. Our results first confirmed that the activation of ROS induced by N-TSHR-Abs was a key player orchestrating apoptosis. ROS has multiple influences including the induction of stress proteins including high expression of multiple mitochondrial stress proteins (Mn-SOD and HSP60) as well as endoplasmic reticulum specific HSP70 protein all of which were detected in thyrocytes when exposed to N-TSHR-Abs in culture.

To clarify ROS regulation in the thyrocyte and the role that TSHR-Abs play in immunopathology, it was essential to define the source and the type of ROS induced by N-TSHR-Abs. Using both specific and selective activators and inhibitors, we found that mitochondria (m) were the primary source of ROS production in the thyrocyte. To implicate mROS in thyroid pathology, it was also important to understand the effector mechanisms involved. mROS is biologically important in cellular stress responses, in adaptation to hypoxia, and in regulation of autophagy, immunity, differentiation and longevity [19]. During ATP generation by mitochondrial aerobic respiration in all cell types, ROS is generated as a byproduct of oxidative phosphorylation [10]. H2O2 in thyrocytes is required for thyroid hormone synthesis. It oxidizes iodide into iodine in a reaction catalyzed by thyroid peroxidase (TPO). TPO then incorporates iodine into tyrosine residues of thyroglobulin to produce thyroid hormones. To avoid deleterious effects, several protective systems against excessive ROS are activated in thyrocytes. For example, selenium has been shown to be an essential component for glutathione peroxidase activity to scavenge ROS. Since ROS are second messengers for activation of multiple signaling molecules, increased ROS can cause cell damage induced senescence or death [19]. Our results of mROS activation in thyrocytes by N-TSHR-Abs suggest that such antibodies may influence thyroid function and that over production of mROS may induce down-stream cellular damage responses.

Apoptosis was the resulting down-stream mROS effect in thyroid cells when exposed to N-TSHR-Abs. Both high annexin V expression and total caspase assays indicated that apoptosis was the main mechanism in the cell death process. However, our earlier proteomic array study suggested that mROS induced both ER stress proteins and the apoptosis-inducing BAX protein [1] thus suggesting non-mutually exclusive mechanisms for apoptosis. In the presence of either TSH or S-TSHR-Abs, the mROS induction by N-TSHR-Abs was suppressed and so was annexin V expression further illustrating that mROS suppression was capable of preventing apoptosis. These findings demonstrated that a balance of certain signaling cascades decide a cell’s fate (Fig. 6). Our earlier studies indicated that both Gα (cAMP/PKA/CREB) and Gq or Gβγ (PI3K/AKT/PKC) were significant pathways for thyroid cell survival and proliferation [2]. We envisioned that both were important for the cell survival process while lack of Gsα activation by N-TSHR-Ab may be the essential element for the apoptosis via mROS induction. In fact, cAMP directly, and PKA activating agents (IBMX, Forskolin, TSH and S-TSHR-Ab), all suppressed N-TSHR-mAb-induced mROS generation and recent findings on the regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis by PKA are in agreement with our observations [20,21]. Since cAMP can suppress mROS within 15 min (data not shown), we propose that this signaling event has a direct effect on mitochondrial function. Recent studies have documented that PKA signaling is compartmentalized and this may provide insight into the differing effects of PKA such as in the mitochondria [22]. Others have documented the existence of PD2A in the mitochondria [23] and that PKA is involved in mitochondrial biogenesis [24]. However, it remains to be demonstrated exactly how cAMP/PKA suppresses mROS activation.

Fig. 6.

A cycle of Graves’ autoimmunity generated by two mutually non-exclusive mechanisms exacerbated by multiple TSHR-Abs. S-TSHR-Abs induce a living (proliferation) cycle while N-TSHR-Abs involve a death (apoptosis) cycle. The living cycle includes activation of PKA/CREB/AKT leading to cell proliferation and excessive T3/T4 production while suppressing mitoROS and NADPH oxidase. In contrast, the death cycle has the opposite effects. Neutral antibodies suppress PKA/CREB/AKT leading to activation of mitoROS and induction of apoptosis and cell death.

To confirm that cAMP/PKA is indeed involved in mROS suppression as a negative regulator, we treated thyrocytes with a known PKA selective inhibitor (H89) either in the presence of S-TSHR-Ab or alone. Strikingly the PKA inhibitor induced mROS in both a time- and dose-dependent manner and the attenuation of PKA-induced mROS production by S-TSHR-Ab was also evident. Furthermore, S-TSHR-Ab prevented apoptosis induced by the PKA inhibitor suggesting that PKA was a negative regulator of mROS linked to the mitochondrial biogenesis mechanism proposed earlier. Since PKA and mROS are both in the same compartment, which is at the cross-roads of many signal transduction networks [25], it is possible that a cross-talk between them exists. Recently, mROS activation via cyclophilin D has been demonstrated in Alzheimer’s disease which suppressed PKA activity leading to synaptic degeneration [25]. Further studies should aim to uncover such events in thyrocytes and to determine whether mROS is able to dampen PKA function and vice versa.

To determine more key signaling molecules in thyrocytes after exposing them to different TSHR antibodies and TSH ligand, we compared results of immunoblots from two time period experiments (1-h vs. 24-h). They were not identical suggesting that certain signaling cascades were more important than others for the cell fate decision. Particularly, PKA/CREB (Gα) and AKT/mTOR/S6K (Gq) signaling cascades were the most important because S-TSHRAb sustained their activities over 24 h. Activation of these signaling cascades favored our earlier observations that paralleled the proliferation index of thyrocytes induced by S-TSHR-Abs [1,2]. On the contrary, N-TSHR-Ab sustained stress associated protein p38 and ATF-2 but failed to sustain ERK1/2 activities. These findings were opposite to the proliferation index and favored the cell death process [26]. Although there were some discrepancies between up-stream and down-stream molecules of ERK1/2 activity, our findings did indicate that mROS could have induced multiple untoward influences on them. To confirm a clear association between these two Gα and Gq signaling cascades in the event of the cell proliferation and mROS suppression induced by S-TSHR-Abs, it is essential to study them in a day-dependent fashion to see the complete response profile.

Signaling molecules transfer information to others in close proximity in order to carry on their end function. Our result with CREB, one of the down-stream effectors of PKA, was intriguing. Nuclear accumulation of phosphorylated CREB was detected after 24 h of stimulation by S-TSHR-Ab but not by the N-TSHR-Abs. CREB is an essential signaling molecule that transcribes multiple key proteins for cell survival and organelle biogenesis [27,28]. Our findings are in accordance with previous observations which clearly demonstrated that such a dynamic spatio-temporal association also exists in thyrocyte activation [27]. Further study of multiple down-stream and spatio-temporal transcriptome analyses will help us to understand thyrocyte signaling mechanisms and their final effects.

To evaluate whether human TSHR-Abs are able to induce similar effects to those induced by the hamster and mouse mAbs we exposed thyrocytes to human purified IgGs from patients with Graves’ disease. Two patients showed clear evidence of apoptotic features and the two induced higher mROS compared to the controls. Serum IgG contains a repertoire of multiple TSHR-Abs so it is likely that different antibodies with different affinities may bind to different TSHRs on the same cell and this is particularly important since the TSHR is multimeric. In this receptor antibody binding scenario, only those antibodies that induce cAMP/PKA would be able to rescue cells from apoptosis. Clearly both the concentrations and the affinities of the antibodies will determine cellular fate. These findings do indicate that TSHR-Abs from GD are capable of inducing apoptosis and mROS generation ex vivo further suggesting that pathological TSHR-Abs can induce thyrocyte apoptosis via mROS activation in the thyroid gland. Since both mROS and apoptosis are implicated in the pathogenesis of thyroid autoimmunity [29–32] and in Graves’ orbitopathy [33], an mROS scavenging agent, as seen in the earlier selenium trial [34], may be a beneficial mechanism for Graves’ orbitopathy.

In conclusion, the present studies indicate that signaling diversity induced by multiple TSHR-Abs regulate the cell fate decision. While S-TSHR-Abs may prevent and rescue cells from apoptosis by suppressing mROS via activation of PKA/CREB and AKT/mTOR/S6K, the N-TSHR-Abs may aggravate the local inflammatory infiltrate within the thyroid or in the retro-orbit by inducing cellular apoptosis through activation of mROS generation without sustaining both Gs and Gq signaling cascades. Our observations suggest that keeping mROS at a low level is important for cell survival and thus high activity mROS inhibitors may be helpful for the treatment of severe Graves’ disease and Graves’ orbitopathy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by NIH grants DK069713, DK052464 and the VA Merit Award Program.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement S.A.M. has nothing to declare. TFD is a Member of the Board of Kronus Inc, Starr, Idaho, which markets diagnostic kits including those for thyroid autoantibodies.

Appendix A. Supplementary data Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2013.07.009.

References

- [1].Morshed SA, Ando T, Latif R, Davies TF. Neutral antibodies to the TSH receptor are present in Graves’ disease and regulate selective signaling cascades. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5537–49. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Morshed SA, Latif R, Davies TF. Characterization of thyrotropin receptor antibody-induced signaling cascades. Endocrinology. 2009;150:519–29. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Morshed SA, Latif R, Davies TF. Delineating the autoimmune mechanisms in Graves’ disease. Immunol Res. 2012;54:191–203. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Vlase H, Graves PN, Magnusson RP, Davies TF. Human autoantibodies to the thyrotropin receptor: recognition of linear, folded, and glycosylated recombinant extracellular domain. JClin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:46–53. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.1.7829638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mori T, Sugawa H, Piraphatdist T, Inoue D, Enomoto T, Imura H. A synthetic oligopeptide derived from human thyrotropin receptor sequence binds to Graves’ immunoglobulin and inhibits thyroid stimulating antibody activity but lacks interactions with TSH. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;178:165–72. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91794-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Endo T, Ohmori M, Ikeda M, Anzai E, Onaya T. Heterogeneous responses of recombinant human thyrotropin receptor to immunoglobulins from patients with Graves’ disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;186:1391–6. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81560-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nagy EV, Burch HB, Mahoney K, Lukes YG, Morris JC, III, Burman KD. Graves’ IgG recognizes linear epitopes in the human thyrotropin receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;188:28–33. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)92345-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fan JL, Desai RK, Seetharamaiah GS, Dallas JS, Wagle NM, Prabhakar BS. Heterogeneity in cellular and antibody responses against thyrotropin receptor in patients with Graves’ disease detected using synthetic peptides. J Autoimmun. 1993;6:799–808. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1993.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Takai O, Desai RK, Seetharamaiah GS, Jones CA, Allaway GP, Akamizu T, et al. Prokaryotic expression of the thyrotropin receptor and identification of an immunogenic region of the protein using synthetic peptides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;179:319–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91372-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Marchi S, Giorgi C, Suski JM, Agnoletto C, Bononi A, Bonora M, et al. Mitochondria-ros crosstalk in the control of cell death and aging. J Signal Transduct. 2012;2012:329635. doi: 10.1155/2012/329635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and cancer: have we moved forward? Biochem J. 2007;401:1–11. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Venditti P, Di Meo S. Thyroid hormone-induced oxidative stress. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:414–34. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5457-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Milenkovic M, De Deken X, Jin L, De Felice M, Di Lauro R, Dumont JE, et al. Duox expression and related H2O2 measurement in mouse thyroid: onset in embryonic development and regulation by TSH in adult. J Endocrinol. 2007;192:615–26. doi: 10.1677/JOE-06-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zarkovic M. The role of oxidative stress on the pathogenesis of graves’ disease. J Thyroid Res. 2012;2012:302537. doi: 10.1155/2012/302537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mano T, Shinohara R, Iwase K, Kotake M, Hamada M, Uchimuro K, et al. Changes in free radical scavengers and lipid peroxide in thyroid glands of various thyroid disorders. Horm Metab Res. 1997;29:351–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Iacovelli L, Capobianco L, Salvatore L, Sallese M, D’Ancona GM, De BA. Thyrotropin activates mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in FRTL-5 by a cAMP-dependent protein kinase A-independent mechanism. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:924–33. doi: 10.1124/mol.60.5.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].mbesi-Impiombato FS, Parks LA, Coon HG. Culture of hormone-dependent functional epithelial cells from rat thyroids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:3455–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mukhopadhyay P, Rajesh M, Hasko G, Hawkins BJ, Madesh M, Pacher P. Simultaneous detection of apoptosis and mitochondrial superoxide production in live cells by flow cytometry and confocal microscopy. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2295–301. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sena LA, Chandel NS. Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell. 2012;48:158–67. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Leadsham JE, Gourlay CW. cAMP/PKA signaling balances respiratory activity with mitochondria dependent apoptosis via transcriptional regulation. BMC Cell Biol. 2010;11:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-11-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Feliciello A, Gottesman ME, Avvedimento EV. cAMP-PKA signaling to the mitochondria: protein scaffolds, mRNA and phosphatases. Cell Signal. 2005;17:279–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Acin-Perez R, Salazar E, Kamenetsky M, Buck J, Levin LR, Manfredi G. Cyclic AMP produced inside mitochondria regulates oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Metab. 2009;9:265–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Acin-Perez R, Russwurm M, Gunnewig K, Gertz M, Zoidl G, Ramos L, et al. A phosphodiesterase 2A isoform localized to mitochondria regulates respiration. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:30423–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.266379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Poeggeler B, Knuever J, Gaspar E, Biro T, Klinger M, Bodo E, et al. Thyrotropin powers human mitochondria. FASEB J. 2010;24:1525–31. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-147728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Du H, Guo L, Wu X, Sosunov AA, McKhann GM, Chen JX, et al. Cyclophilin D deficiency rescues Aβ-impaired PKA/CREB signaling and alleviates synaptic degeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013 Mar 16; doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.03.004. PII: S0925-4439(13)00078-1, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [26].Lee J, Kim CH, Simon DK, Aminova LR, Andreyev AY, Kushnareva YE, et al. Mitochondrial cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (CREB) mediates mitochondrial gene expression and neuronal survival. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40398–401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500140200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Nguyen LQ, Kopp P, Martinson F, Stanfield K, Roth SI, Jameson JL. A dominant negative CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein) isoform inhibits thyrocyte growth, thyroid-specific gene expression, differentiation, and function. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1448–61. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.9.0516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bleckmann SC, Blendy JA, Rudolph D, Monaghan AP, Schmid W, Schutz G. Activating transcription factor 1 and CREB are important for cell survival during early mouse development. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1919–25. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.6.1919-1925.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bossowski A, Czarnocka B, Bardadin K, Stasiak-Barmuta A, Urban M, Dadan J, et al. Identification of apoptotic proteins in thyroid gland from patients with Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Autoimmunity. 2008;41:163–73. doi: 10.1080/08916930701727749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Pritchard J, Horst N, Cruikshank W, Smith TJ. Igs from patients with Graves’ disease induce the expression of T cell chemoattractants in their fibroblasts. J Immunol. 2002;168:942–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Stassi G, De Maria R. Autoimmune thyroid disease: new models of cell death in autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:195–204. doi: 10.1038/nri750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pedersen IB, Knudsen N, Carle A, Schomburg L, Kohrle J, Jorgensen T, et al. Serum selenium is low in newly diagnosed Graves’ disease: a population-based study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013 doi: 10.1111/cen.12185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Konuk O, Hondur A, Akyurek N, Unal M. Apoptosis in orbital fibroadipose tissue and its association with clinical features in Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2007;15:105–11. doi: 10.1080/09273940601186735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Marcocci C, Kahaly GJ, Krassas GE, Bartalena L, Prummel M, Stahl M, et al. Selenium and the course of mild Graves’ orbitopathy. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1920–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.