Abstract

Genetic elements in HIV-1 subtype B tat and env are associated with neurotoxicity yet less is known about other subtypes. HIV-1 sub-type C tat and env sequences were analyzed to determine viral genetic elements associated with neurocognitive impairment in a large Indian cohort. Population-based sequences of HIV-1 tat (exon 1) and env (C2-V3 coding region) were generated from blood plasma of HIV-infected patients in Pune, India. Participants were classified as cognitively normal or impaired based on neuropsychological assessment. Tests for signature residues, positive and negative selection, entropy, and ambiguous bases were performed using tools available through Los Alamos National Laboratory (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov) and Datamonkey (http://www.datamonkey.org). HIV-1 subtype C tat and env sequences were analyzed for 155 and 160 participants, of which 34–36% were impaired. Two signature residues were unique to impaired participants in exon 1 of tat at codons 29 (arginine) and 68 (proline). Positive selection was noted at codon 29 among normal participants and at codon 68 in both groups. The signature at codon 29 was also a signature for low CD4+ (<200 cells/mm3) counts but remained associated with impairment after exclusion of those with low CD4+ counts. No unique genetic signatures were noted in env. In conclusion, two signature residues were identified in exon 1 of HIV-1 subtype C tat that were associated with neurocognitive impairment in India and not completely accounted for by HIV disease progression. These signatures support a linkage between diversifying selection in HIV-1 subtype C tat and neurocognitive impairment.

Keywords: neuropsychological testing, impairment, sequence, signature, residue, clade C

INTRODUCTION

HIV (Order, Virales; family, Retroviridae; subfamily, Orthoretrovirinae; genus, Lentivirus; species, Human immunodeficiency virus) crosses the blood–brain barrier during primary infection, eventually resulting in neurological complications in up to 50% of individuals with clade B HIV-1 [Heaton et al., 2010a]. Although infection of neurons occurs rarely if at all, viral proteins such as HIV-1 Tat and Env have neurotoxic properties [Albini et al., 1998; Kruman et al., 1998; Kaul et al., 2001; Aksenov et al., 2009; Li et al., 2009]. Studies of blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-derived viral sequences for clade B HIV-1 have identified signature polymorphisms at positions 9, 13, and 19 of the V3 loop of HIV-1 env and at position HXB2 5905 within the cysteine-rich domain of HIV-1 tat that distinguish CSF-derived virus from blood plasma-derived virus [Pillai et al., 2006; Choi et al., 2012]. Further, a residue at position 5 of the V3 loop is associated with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) [Pillai et al., 2006; Antinori et al., 2007]. Constrained viral diversity and fewer glycosylated and positively selected sites in the C2-V3 env subregion are associated with CSF compartmentalization [Pillai et al., 2006], while in tat, increased diversity in CSF, reflected by a higher number of mixed bases, was associated with neurocognitive impairment [Choi et al., 2012].

Less is known about the genetic attributes and neuropathogenesis of HIV-1 subtype C, which is the most common circulating subtype in the world [Hemelaar et al., 2006]. A naturally occurring genetic difference between HIV-1 B and C tat has been described at residue 31 in the cysteine-rich domain, where subtype C has a serine and subtype B has a cysteine [Ranga et al., 2004]. This change in vitro resulted in attenuated neurotoxic properties of Tat [Ranga et al., 2004; Mishra et al., 2008]. Despite earlier reports of lower rates of HIV-associated dementia in India, where over 95% of HIV-1 infections are due to subtype C, compared to North America and Europe [Satishchandra et al., 2000; Wadia et al., 2001; Shankar et al., 2005], rates of mild to moderate neurocognitive impairment appear to be common [Yepthomi et al., 2006; Gupta et al., 2007]. The lack of clear clinical consequences of this provocative laboratory finding in tat raises the possibility that other genetic changes counteract this in vitro effect. In this study, we investigated multiple viral characteristics of HIV-1 subtype C tat and env derived from the blood of patients with and without HAND in Pune, India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Participants and Specimens

This study was conducted within the framework of a research collaboration between the HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center (HNRC) at UCSD and the National AIDS Research Institute (NARI) in Pune, India, and necessary institutional board review and ethical committee approvals were obtained at both locations. Blood-derived HIV-1 tat and env sequences were available for 246 and 228 of the study participants enrolled in the primary cohort in Pune, India. These participants consisted of: (1) HIV-infected patients with CD4+ <200 cells/mm3 who were to start antiretroviral therapy (ART) according to the Indian national ART guidelines [National AIDS Control Organisation MoHFW, 2007] and (2) HIV-infected members of serodiscordant couples participating in HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 052 with CD4+ ≥350 cells/mm3 who were randomized either to receive immediate ART or to be initiated on treatment after a decline in CD4+ count or development of AIDS-related symptoms [Cohen et al., 2011].

All but 11 of these participants were ART-naïve at the time of evaluation (see below) and none had either evidence of active, major opportunistic infection that might impact performance on neuropsychological testing (e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Cryptococcus neoformans, syphilis) or had been initiated on treatment for an active infection in the 3 months prior to enrollment. In considering confounding and contributing co-morbidities, guidelines described [Antinori et al., 2007] and applied [Heaton et al., 2010a] elsewhere were followed. Since exclusion criteria covered conditions that might confound significantly the determination of HIV-related cognitive impairments, none of the participants of the current study would have been considered “confounded.” Conditions that might be considered “contributing,” such as a major depressive episode affecting testing effort, ongoing significant substance use, mild traumatic brain injury, etc., were also very rare in this cohort (e.g., <5%), and there was no relationship between these conditions and impairment rates, suggesting a no-to-minimal effect on cognitive performance in this cohort. Therefore, subjects with potentially “contributing” factors were still included in the analyses. Blood was collected in EDTA-containing vacutainers, and blood plasma was aliquoted, frozen, and stored at −80°C until processing.

Neurobehavioral Assessment

Study participants completed a detailed neuropsychological assessment that has been used in other international studies [Heaton et al., 2010b], is similar to the battery used in large multisite studies in the United States [Heaton et al., 2010a], and was validated in a Marathi-speaking sample in Pune using population-specific norms corrected for the effects of age, education, and sex [Kamat et al., 2012]. Due to the lack of established norms for persons with three years or less of formal education, these participants were excluded from the analyses. Global deficit scores (GDS) were calculated as described previously as a measurement of neuropsychological test performance [Carey et al., 2004; Heaton et al., 2004]. Participants with GDS <0.5 were classified as “normal,” while those with GDS≥0.5 were classified as “impaired.”

Nucleotide Sequencing

HIV-1 RNA was extracted from 140 μl of blood plasma using the QIAmp® Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and reverse transcription of extracted HIV-1 RNA was performed using the RobusT™ I RT-PCR Kit (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Reverse transcription was performed using a single step continuous reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR, one-step PCR) method followed by nested PCR amplification of HIV-1 tat exon 1 and the C2V3 region of HIV-1 env that has been described elsewhere [Mullick et al., 2006]. The final PCR products were purified using the QIAquick® PCR Purification kit (Qiagen). Population based sequencing of the purified products was done using BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on an ABI 3730xl DNA Analyzer.

Sequence Analysis

Sequences were edited and aligned initially by Clustal W [Thompson et al., 1994]. The alignments were edited manually in Bioedit, version 7.05 to preserve frame insertions and deletions if present [Hall, 1999]. Sequences were examined for inter-subtype recombination using the Recombinant Identification Program (RIP) 3.0 on the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) HIV Sequence Database website (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/HIV/HIVTools.html), and were screened for contamination using the DNA Distance Matrix function in Bioedit. Sequences with an evolutionary distance of 0 to 2 or more other sequences were considered as possibly contaminated.

After exclusion of non-C HIV-1 subtypes, subjects on ART at the time of sequencing, and contaminated sequences, HIV-1 tat and env sequences were grouped according to the presence or absence of neurocognitive impairment based on GDS. Sequences were evaluated for signature residues using the Viral Epidemiology Signature Pattern Analysis program (VESPA) available through LANL [Korber and Myers, 1992]. Positive and negative selection was assessed using single-likelihood ancestor counting (SLAC) [Pond, 2005], which was implemented on the web-based Datamonkey (http://www.datamonkey.org) [Pond and Frost, 2005; Pond et al., 2005; Delport et al., 2010], with a level of significance set at 0.05. Shannon entropy was calculated to identify differences in site-specific variability in HIV-1 tat or env according to neurocognitive status, using the Entropy sequence analysis tool available through LANL. A batch file implemented in HyPhy was used to provide a measure of viral population diversity by counting total mixed bases, synonymous mixed bases, and non-synonymous mixed bases [Pond et al., 2005]. All of these analyses were performed separately for tat and for env sequences. After generation of consensus tat sequences for both groups and conversion of DNA to RNA in Bioedit, secondary RNA structures with lowest free energy were predicted for the first exon of HIV-1 subtype C tat with one, two, or no signature non-synonymous mutations using the algorithm implemented in RNAstructure v5.3 [Reuter and Mathews, 2010] for the purpose of hypothesis generation. To compare the frequency of genetic elements identified in tat in the study cohort to that in other HIV-1 subtype C-infected populations, all available subtype C HIV-1 tat sequences from all regions were retrieved using the “Search” interface in the LANL HIV Sequence Database (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/components/sequence/HIV/search/search.html).

Statistical Analysis

Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square analysis was used in the comparison of categorical or binary measurements, and either independent t-tests or Mann–Whitney U-tests were used in the comparison of continuous variables. An independent t-test was used to compare the frequency of synonymous, non-synonymous, and total mixed bases between the two groups. Chi-square analyses were used to compare amino acid frequencies between the groups in the study cohort and from other regions. All P-values were two-tailed, and a P-value of <0.05 was designated as representing statistical significance unless otherwise indicated.

RESULTS

Study Cohort and Rate of HAND

Paired HIV-1 subtype C tat sequences and results of neuropsychological testing were available for 163 study participants in the Pune cohort. Since ART can impact neurocognitive function, eight patients who were already on ART at the time of sequencing were excluded from the analyses. The final dataset included 155 participants of whom 36% were impaired based on GDS. The majority of participants included in the tat analyses were men (65%) with a mean age of 34.5 years. The mean CD4+ T cell count at the time of neuropsychological testing was 270 cells/mm3 and the mean plasma HIV-1 RNA level was 4.7 log10 copies/ml. There were no significant differences in age, sex, level of education, AIDS diagnoses, and HIV-1 RNA levels between those with and without neurocognitive impairment. Participants with neurocognitive impairment had a lower mean CD4+ T cell count at the time of neuropsychological testing compared to those without impairment (224 cells/mm3 vs. 296 cells/mm3, P=0.02), although the difference in nadir CD4+ T cell counts between the two groups was of borderline significance (216 cells/mm3 vs. 274 cells/mm3, P=0.05, see Table Ia). After exclusion of 11 participants already on ART, paired HIV-1 subtype C env sequences and results of neuropsychological testing were available for 160 study participants, 34% of whom were impaired. Clinical and demographic characteristics were similar for participants with available env sequences (see Table Ib). The cohort self-reported the following primary risk factors for contracting HIV: heterosexual contact (64%), homosexual contact (1%), transfusion (2%), work-related injury (2%), “other” (13%), and unknown (19%).

TABLE I.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Subjects Included in the (a) tat and (b) env Analyses

| (a) Characteristics | Overall (n=155) | Impaired (n=56) | Normal (n=99) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean±SD | 34.5±7.2 | 35.4±7.0 | 34.1±7.3 | 0.29 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 100 (65%) | 38 (68%) | 62 (63%) | 0.63 |

| Education (years), mean±SD | 9.0±2.7 | 8.6±2.4 | 9.2±2.9 | 0.15 |

| AIDS diagnosis, no. (%) of subjects | 91 (59%) | 38 (68%) | 53 (54%) | 0.13 |

| Current CD4 count (cells/mm3), mean±SDa | 270±191 | 224±184 | 296±191 | 0.02* |

| Nadir CD4 count (cells/mm3), mean±SD | 253±177 | 216±173 | 274±176 | 0.05 |

| Plasma HIV RNA (log10 copies/ml), mean±SDa | 4.7±0.9 | 4.8±0.8 | 4.6±0.9 | 0.13 |

|

| ||||

| (b) Characteristics | Overall (n=160) | Impaired (n=54) | Normal (n=106) | P-value |

|

| ||||

| Age (years), mean±SD | 34.9±7.5 | 35.6±7.1 | 34.5±7.6 | 0.39 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 103 (64%) | 36 (67%) | 67 (63%) | 0.79 |

| Education (years), mean±SD | 9.1±2.7 | 8.8±2.3 | 9.3±2.8 | 0.28 |

| AIDS diagnosis, no. of subjects (%) | 90 (56%) | 35 (65%) | 55 (52%) | 0.18 |

| Current CD4 count (cells/mm3), mean±SDb | 276±188 | 232±181 | 299±189 | 0.03* |

| Nadir CD4 count (cells/mm3), mean±SD | 262±179 | 228±179 | 279±177 | 0.09 |

| Plasma HIV RNA (log10 copies/ml), mean±SDb | 4.6±0.9 | 4.8±0.8 | 4.6±0.9 | 0.18 |

SD, standard deviation.

Current CD4 counts and viral load calculations are based on data from 154 subjects (data were not available for one subject in the normal group).

Current CD4 and viral load calculations are based on data from 159 subjects (data were not available for one subject in the normal group).

P<0.05.

Characteristics of Blood-Derived HIV-1 tat in Subjects With and Without Impairment

Two residues at codon positions 29 and 68 within exon 1 of HIV-1 tat were associated with neurocognitive impairment. The arginine at position 29 in the cysteine-rich domain of tat was a signature residue for impairment (39.3% of impaired vs. 29.3% of normal participants). Positive selection was inferred at this position among normal participants (P=0.02), with 45% of observed non-synonymous substitutions resulting in a transition between arginine and other amino acids. Most of these substitutions were presumed to result in transition from arginine to another amino acid, although reversed directionality is possible since an unrooted phylogenetic tree was used in the analysis. A proline at codon position 68 in the auxiliary domain of exon 1 of HIV-1 tat was a signature residue among impaired participants (51.8% of impaired vs. 35.4% of normal participants). Positive selection was inferred at position 68 for both normal and impaired participants (P<0.01 in both groups), with selection both for and against proline occurring in each group. The frequency of the natural amino acid variation associated with HIV-1 subtype C virus, namely serine (S) rather than cysteine (C) at codon position 31, was also determined, given its association in vitro with attenuated neurotoxicity [Ranga et al., 2004; Mishra et al., 2008]. The overall frequency of the S in the cohort was 95%, and this did not differ between the normal and impaired groups (P=0.76).

There was no significant difference in site-specific variability between normal and impaired participants as measured by Shannon entropy at any position within the analyzed region of HIV-1 tat exon 1 (all P ≥ 0.05). As a measure of viral population diversity [Poon et al., 2010; Hightower et al., 2012] in each group, the number of synonymous, non-synonymous, and total mixed bases in each population-based sequence was determined, and these measures were not different between normal and impaired participants (P=0.89, 0.96, and 0.98, respectively).

To determine the impact of HIV disease progression on the presence of the identified signature residues in tat, sequences were divided into low (<200 cells/mm3) and high (≥ 200 cells/mm3) CD4+ groups based on current CD4+ T-cell counts at the time of testing. The arginine at position 29 was identified as a signature residue for the low CD4+ group although the difference in prevalence between the two groups was <5% (34.6% of the 81 participants with low CD4+ T-cell counts vs. 31.1% of the 74 participants with high CD4+ T-cell counts). Similar to the primary analysis, positive selection was inferred at position 29 among participants with high CD4+ T-cell counts, with 45% of observed non-synonymous substitutions resulting in transition between arginine and other amino acids, although this did not achieve statistical significance (P=0.07). The sequences in each CD4+ group then were divided further according to results of neuropsychological testing, and the analyses were repeated to compare normal and impaired participants in each group. Among participants with CD4+ ≥200, the arginine at position 29 was a signature residue for impairment (40.0% of the 20 impaired participants vs. 27.8% of the 54 normal participants), although there was no evidence of differential selection at this position between the two groups. Among participants with CD4+ <200, there was no signature at position 29 that differentiated the two groups, although the proline at position 68 was identified as a signature of impairment (58.3% of the 36 impaired participants vs. 35.6% of the 45 normal participants). Positive selection was inferred at this position in both groups (P=0.02 for normal participants and P < 0.01 for impaired participants), with the majority of non-synonymous substitutions resulting in transition between proline and other amino acids (mainly leucine). Unlike the primary analysis, the directionality of these transitions differed between the two groups. An additional signature at position 60 (glutamine) also was associated with impairment in the low CD4+ group (47.2% of the 36 impaired participants vs. 42.2% of the 45 normal participants).

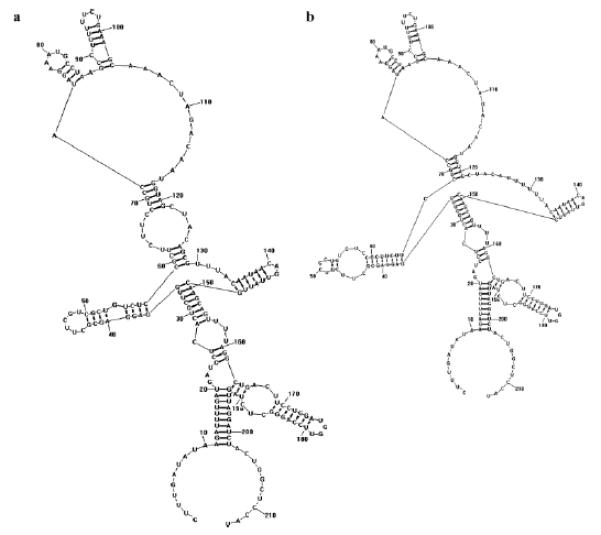

To investigate further the effect of the identified signature residues on tat structure and function and for the purposes of hypothesis generation for functional studies, secondary RNA structures were predicted for consensus sequences derived for both normal and impaired participants containing each, both, or neither of the signature residues associated with neurocognitive impairment. The presence of proline versus leucine at codon 68 did not significantly affect the structure of the dicysteine motif, while the presence of arginine versus lysine at codon 29 did. This difference in secondary RNA structure of the dicysteine motif in the presence or absence of the signature mutation at position 29 is demonstrated in Figure 1. The lowest free energy of all structures was similar, ranging from −60.2 kcal/mol when both signatures were present (i.e., arginine at codon 29 and proline at codon 68) to −52.6 kcal/mol when neither signature was present (i.e., lysine at codon 29 and leucine at codon 68, which were the most common residues among normal participants at these positions). In other words, the signature mutation at position 29 altered the secondary RNA structure within the dicysteine motif but without a significant thermodynamic cost.

Fig. 1.

Secondary RNA structures with lowest free energy generated from consensus sequences for subjects with normal performance on neuropsychological testing with either (a) arginine or (b) lysine at codon 29. Nucleotides 121–126 code for the dicysteine motif. Similar changes were demonstrated for the impaired group at this position, although amino acid differences at codon 68 did not result in significant changes in secondary RNA structure of this region. In these examples, the amino acid at codon 68 is leucine, which was the signature for normal subjects.

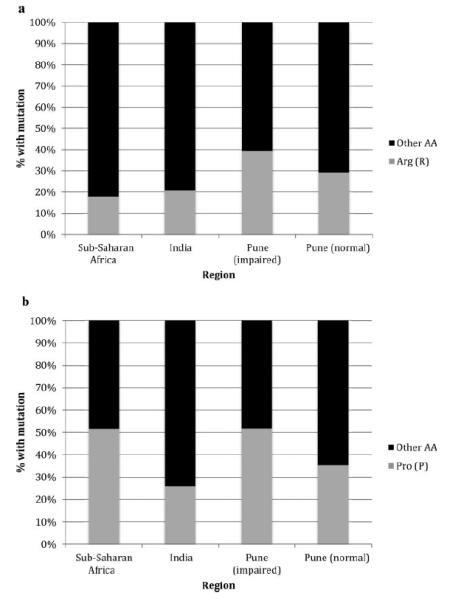

To determine the relative frequencies of signature amino acid residues at codons 29 and 68 in the Pune cohort compared to other subtype C-infected populations, all HIV-1 subtype C tat sequences available in the LANL HIV Sequence Database were retrieved. Since the vast majority of available subtype C tat sequences were from either sub-Saharan Africa (n=1,165) or India (n=212), only sequences from these regions were compared to the normal (n=99) and impaired (n=56) groups in the Pune cohort. Since these included all sequences entered into the LANL database and no clinical data, including results of neuropsychological testing, were available, sequences from sub-Saharan Africa and India were analyzed by region and not divided according to the presence or absence of impairment. The relative frequencies of arginine and other amino acids at position 29 are shown in Figure 2a. The frequencies of arginine in sub-Saharan Africa and in India as a whole were similar (18% and 21%, P=0.37) but lower than in the Pune cohort, particularly when compared to the impaired group. Arginine was almost twice as frequent in impaired participants in Pune when compared to all Indian HIV-1 subtype C tat sequences (39% vs. 21%, P < 0.01). No significant difference in residue frequency was observed between the normal participants in the Pune cohort and those derived from India as a whole (29% vs. 21%, P=0.10, see Fig. 2a). The relative frequencies of proline and other amino acids at position 68 are shown in Figure 2b. These frequencies were similar for sub-Saharan African HIV-1 subtype C sequences and those derived from impaired participants in Pune, with around 52% of sequences in each group containing proline at position 68 (P=0.92) but much lower (26%) for India as a whole (P < 0.01). Normal participants in the cohort had a profile (35%) that was more similar to that of India as a whole (P=0.12) than to the other groups (see Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

a: Relative amino acid frequencies at codon 29: The percentages of subtype C HIV-1 tat sequences with arginine and other amino acids at residue 29 are shown for viral sequences obtained from sub-Saharan Africa, India, and the Pune study cohort. b: Relative amino acid frequencies at codon 68: the percentages of subtype C HIV-1 tat sequences with proline and other amino acids at residue 68 are shown for viral sequences obtained from sub-Saharan Africa, India, and the Pune study cohort.

Characteristics of Blood-Derived HIV-1 Subtype C env in Patients With and Without Impairment

Unlike studies of HIV-1 subtype B [Pillai et al., 2006; Antinori et al., 2007], no signature residue was identified that distinguished those with neurocognitive impairment from those without impairment. At codons 21 and 38, higher entropy was noted among impaired participants than among normal participants (P=0.01 and 0.04, respectively), while higher entropy was noted among normal participants at position 37 (P=0.05). When viral diversity was evaluated as the number of total, synonymous or non-synonymous mixed bases, no significant difference was observed between the two groups.

DISCUSSION

HIV-1 Tat causes neurotoxicity via monocyte chemotaxis [Albini et al., 1998] and induction of intrinsic neuronal apoptotic pathways involving oxidative stress, calcium overload, mitochondrial membrane disturbances, cytochrome c release, and activation of caspase [Kruman et al., 1998]. In vitro experiments have demonstrated that these properties may be affected by amino acid variations in the first exon of HIV-1 tat. A naturally occurring amino acid variation in the majority of HIV-1 subtype C tat, namely the presence of serine rather than cysteine at position 31 in the dicysteine motif, was shown to result in attenuation of these properties and decreased neurotoxicity [Ranga et al., 2004; Mishra et al., 2008] compared to subtype B tat with cysteine at this position. Other alterations in HIV-1 tat, including the signature residues identified in the present study, could result in increased neurotoxicity either by facilitating monocyte chemotaxis and induction of apoptosis, counteracting residues associated with attenuation of neurotoxicity such as that at position 31, or a combination of these mechanisms, and warrant further investigation through functional studies.

In the present study, two amino acid residues in exon 1 of HIV-1 subtype C tat were associated with neurocognitive impairment. Arginine at codon 29 was identified as a signature residue among study participants with impairment, while lysine was more common among normal participants. Positive selection was inferred at this position among normal participants on a separate analysis, with almost half of substitutions resulting in transition between arginine and other amino acids. Although the reason for this is not clear, this pattern indicates a selective advantage of having (or not) an arginine at position 29 among participants without impairment. Proline rather than leucine at position 68 was also identified as a signature residue among participants with impairment, and positive selection was inferred in both groups at this position, with selection both for and against proline occurring in each group. Although the residue at position 29 was also a signature of participants with low (<200) CD4+ counts, the actual difference between the groups was not significant (<5%), and it remained a signature of impairment among participants with high (≥200) CD4+ counts. This indicates that it is not simply a marker of more advanced HIV infection but is associated with neurocognitive impairment even in participants without advanced immunosuppression. The residue at position 68 did not differ between those with low and high CD4+ counts and therefore is also likely associated with neurovirulence, particularly in participants with advanced immunosuppression.

In order to determine the effect of these residues on secondary RNA structure for hypothesis generating purposes, particularly on the dicysteine motif that has been implicated in viral neuropathogenesis [Ranga et al., 2004; Mishra et al., 2008], secondary RNA structures with lowest free energy were generated, which suggest the thermodynamically preferred shape. The presence of arginine or lysine at amino acid position 29 resulted in a structural change in the dicysteine motif, whereas the signature residue at position 68 did not result in any appreciable change. The frequency of this residue at position 29 occurred at a much higher frequency among impaired participants than would have been expected based on analyses of HIV-1 subtype C sequences from India as a whole and other regions. The frequency of this residue in the impaired group of our cohort was over twice that of all HIV-1 subtype C tat exon 1 sequences from India, although the latter group could not be separated by neurocognitive status, and it is likely that this group, as well as the sample from sub-Saharan Africa, includes a substantial proportion of cognitively impaired individuals. The significance of this signature residue and the associated structural change in the dicysteine motif is not clear and should be evaluated in further in vitro functional studies. Possible mechanisms of this mutation include enhanced interaction of tat with monocytes and chemotaxis, increased activation of intrinsic neuronal apoptotic pathways, or counteraction of the attenuating effect of having a serine at position 31 in exon 1 of HIV-1 subtype C tat.

In regard to the env analyses, no signature residue was identified that distinguished those with and without impairment. This is in contrast to previous work in HIV-1 subtype B [Strain et al., 2005; Pillai et al., 2006]. Since most of these previous studies were associated with CSF compartmentalization and neurocognitive impairment was not evaluated as a binary outcome, it is not surprising that the present analyses of blood plasma-derived env sequences failed to yield similar results. Given the role of env mostly in CSF compartmentalization and evasion of neutralizing antibody responses, it is likely that signature sequences and other genetic elements associated with neurocognitive impairment would be localized in the CSF compartment and therefore not found in significant quantities in blood plasma. Differences in site-specific variation as measured by Shannon entropy were noted between normal and impaired study participants at three positions in env (21, 37, and 38); however, the significance of these findings is not clear. Paired analyses of blood plasma and CSF-derived env sequences would be helpful to determine if there is also an association between genetic elements of HIV-1 subtype C env and either neurotoxicity or CSF compartmentalization.

The lack of CSF-derived sequences also limited analyses of tat in this cohort. Previous analysis of HIV-1 subtype B tat sequences demonstrated significantly higher numbers of mixed bases in those participants with HAND than in those without HAND in the CSF but not in the blood [Choi et al., 2012]. The present study of HIV-1 subtype C tat sequences did not demonstrate a significant difference in the number of mixed bases between the normal and impaired groups in blood, but it was not possible to determine if a significant difference was present in CSF. Further, since participants with less than or equal to 3 years of formal education could not be categorized due to lack of established norms, these results may not be generalizable to this group. Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this is the first study combining HIV-1 tat and env sequences and results of neuropsychological testing from ART-naïve subjects in a non-subtype B infected population and the largest study of HIV-1 subtype C tat sequences to date.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, two signature residues were identified in exon 1 of HIV-1 tat that were associated with neurocognitive impairment in an Indian cohort infected with HIV-1 subtype C, even after taking into account HIV disease progression. One of these, namely an arginine at codon 29 rather than lysine, resulted in a structural change in the dicysteine motif that has been cited as a cause of attenuated neurotoxicity of HIV-1 subtype C tat. The significance of this signature residue with respect to neurotoxicity and its effect on the structure and function of the dicysteine motif in HIV-1 subtype C tat remain to be seen. In vitro functional studies and analyses comparing neuropsychological function and viral genetics in other clade C cohorts are important future steps to confirm these findings. Although entropy at three positions in HIV-1 subtype C env differed significantly between normal and impaired participants, the significance of these findings is unclear. Given the role of HIV-1 subtype B env in neurotropism and CSF compartmentalization, future studies utilizing paired blood and CSF-derived env sequences would be helpful to determine what role, if any, env plays in the neuropathogenesis of HIV-1 subtype C.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Ramesh Paranjape, Director, NARI for his support and the Centre for Genomic Application (TCGA) in New Delhi, India for the use of their sequencing facility. The funding sources had no role in the study design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Grant sponsor: National Institute of Mental Health NIMH NeuroAIDS in India (to T.D.M.)

Grant numbers: R01; MH78748

Grant sponsor: Department of Veterans Affairs

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health

Grant numbers: AI100665; MH097520; DA034978; MH83552; AI36214; MH62512; AI47745;

Grant sponsor: James B. Pendleton Charitable Trust

Footnotes

The present address of Jayanta Bhattacharya is Translational Health Science and Technology Institute, Plot No. 496, Phase-III, Udyog Vihar, Gurgaon, Haryana 122016, India

The present address of Sanjay Mehendale is National Institute of Epidemiology (ICMR), Second Main Road, Tamil Nadu Housing Board, Ayapakkam, Near Ambattur, Chennai, Tamil Nadu 600077, India

REFERENCES

- Aksenov MY, Aksenova MV, Mactutus CF, Booze RM. Attenuated neurotoxicity of the transactivation-defective HIV-1 Tat protein in hippocampal cell cultures. Exp Neurol. 2009;219:586–590. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albini A, Ferrini S, Benelli R, Sforzini S, Giunciuglio D, Aluigi MG, Proudfoot AE, Alouani S, Wells TN, Mariani G, Rabin RL, Farber JM, Noonan DM. HIV-1 Tat protein mimicry of chemokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13153–13158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Clifford DB, Cinque P, Epstein LG, Goodkin K, Gisslen M, Grant I, Heaton RK, Joseph J, Marder K, Marra CM, McArthur JC, Nunn M, Price RW, Pulliam L, Robertson KR, Sacktor N, Valcour V, Wojna VE. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey CL, Woods SP, Gonzalez R, Conover E, Marcotte TD, Grant I, Heaton RK. Predictive validity of global deficit scores in detecting neuropsychological impairment in HIV infection. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004;26:307–319. doi: 10.1080/13803390490510031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JY, Hightower GK, Wong JK, Heaton R, Woods S, Grant I, Marcotte TD, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, Collier AC, Marra CM, Clifford DB, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Morgello S, Simpson DM, McCutchan JA, Richman DD, Smith DM. Genetic features of cerebrospinal fluid-derived subtype B HIV-1 tat. J Neurovirol. 2012;18:81–90. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0059-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Hakim JG, Kumwenda J, Grinsztejn B, Pilotto JH, Godbole SV, Mehendale S, Chariyalertsak S, Santos BR, Mayer KH, Hoffman IF, Eshleman SH, Piwowar-Manning E, Wang L, Makhema J, Mills LA, de Bruyn G, Sanne I, Eron J, Gallant J, Havlir D, Swindells S, Ribaudo H, Elharrar V, Burns D, Taha TE, Nielsen-Saines K, Celentano D, Essex M, Fleming TR. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delport W, Poon AF, Frost SD, osakovsky Pond SL. Datamonkey 2010: A suite of phylogenetic analysis tools for evolutionary biology. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2455–2457. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta JD, Satishchandra P, Gopukumar K, Wilkie F, Waldrop-Valverde D, Ellis R, Ownby R, Subbakrishna DK, Desai A, Kamat A, Ravi V, Rao BS, Satish KS, Kumar M. Neuropsychological deficits in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clade C-seropositive adults from South India. J Neurovirol. 2007;13:195–202. doi: 10.1080/13550280701258407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall T. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acid Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton R, Miller SW, Taylor MJ, Grant I. Revised comprehensive norms for an Expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographically adjusted for neuropsychological norms for African American and Caucasian adults. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, Marcotte TD, Atkinson JH, Rivera-Mindt M, Vigil OR, Taylor MJ, Collier AC, Marra CM, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Morgello S, Simpson DM, McCutchan JA, Abramson I, Gamst A, Fennema-Notestine C, Jernigan TL, Wong J, Grant I. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER study. Neurology. 2010a;75:2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Cysique LA, Jin H, Shi C, Yu X, Letendre S, Franklin DR, Jr, Ake C, Vigil O, Atkinson JH, Marcotte TD, Grant I, Wu Z. Neurobehavioral effects of human immunodeficiency virus infection among former plasma donors in rural China. J Neurovirol. 2010b;16:185–188. doi: 10.3109/13550284.2010.481820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemelaar J, Gouws E, Ghys PD, Osmanov S. Global and regional distribution of HIV-1 genetic subtypes and recombinants in 2004. AIDS 20:W13-W23. 2006 doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247564.73009.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightower GK, Wong JK, Letendre SL, Umlauf AA, Ellis RJ, Ignacio CC, Heaton RK, Collier AC, Marra CM, Clifford DB, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Morgello S, Simpson DM, McCutchan JA, Grant I, Little SJ, Richman DD, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Smith DM. Higher HIV-1 genetic diversity is associated with AIDS and neuropsychological impairment. Virology. 2012;433:498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamat R, Ghate M, Gollan TH, Meyer R, Vaida F, Heaton RK, Letendre S, Franklin D, Alexander T, Grant I, Mehendale S, Marcotte TD. Effects of Marathi-Hindi bilingualism on neuropsychological performance. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2012;18:305–313. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711001731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul M, Garden GA, Lipton SA. Pathways to neuronal injury and apoptosis in HIV-associated dementia. Nature. 2001;410:988–994. doi: 10.1038/35073667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korber B, Myers G. Signature pattern analysis: A method for assessing viral sequence relatedness. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1992;8:1549–1560. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruman II, Nath A, Mattson MP. HIV-1 protein Tat induces apoptosis of hippocampal neurons by a mechanism involving caspase activation, calcium overload, and oxidative stress. Exp Neurol. 1998;154:276–288. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Li G, Steiner J, Nath A. Role of Tat protein in HIV neuropathogenesis. Neurotox Res. 2009;16:205–220. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra M, Vetrivel S, Siddappa NB, Ranga U, Seth P. Clade-specific differences in neurotoxicity of human immunodeficiency virus-1 B and C Tat of human neurons: Significance of dicysteine C30C31 motif. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:366–376. doi: 10.1002/ana.21292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullick R, Sengupta S, Sarkar K, Saha MK, Chakrabarti S. Phylogenetic analysis of env, gag, and tat genes of HIV type 1 detected among the injecting drug users in West Bengal, India. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006;22:1293–1299. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS Control Organisation MoHFW, Government of India . Antiretroviral therapy guidelines for HIV-infected adults and adolescents including post-exposure prophylaxis. National AIDS Control Organisation MoHFW, Government of India; New Delhi: 2007. pp. 1–125. [Google Scholar]

- Pillai SK, Pond SL, Liu Y, Good BM, Strain MC, Ellis RJ, Letendre S, Smith DM, Gunthard HF, Grant I, Marcotte TD, McCutchan JA, Richman DD, Wong JK. Genetic attributes of cerebrospinal fluid-derived HIV-1 env. Brain. 2006;129:1872–1883. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pond SL. Not so different after all: A comparison of methods for detecting amino acid sites under selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1208–1222. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pond SL, Frost SD. Datamonkey: Rapid detection of selective pressure on individual sites of codon alignments. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2531–2533. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pond SL, Frost SD, Muse SV. HyPhy: Hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:676–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon AF, Swenson LC, Dong WW, Deng W, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Brumme ZL, Mullins JI, Richman DD, Harrigan PR, Frost SD. Phylogenetic analysis of population-based and deep sequencing data to identify coevolving sites in the nef gene of HIV-1. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:819–832. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranga U, Shankarappa R, Siddappa NB, Ramakrishna L, Nagendran R, Mahalingam M, Mahadevan A, Jayasuryan N, Satishchandra P, Shankar SK, Prasad VR. Tat protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C strains is a defective chemokine. J Virol. 2004;78:2586–2590. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2586-2590.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter JS, Mathews DH. RNAstructure: Software for RNA secondary structure prediction and analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satishchandra P, Nalini A, Gourie-Devi M, Khanna N, Santosh V, Ravi V, Desai A, Chandramuki A, Jayakumar PN, Shankar SK. Profile of neurologic disorders associated with HIV/AIDS from Bangalore, South India (1989-96) Indian J Med Res. 2000;111:14–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar SK, Mahadevan A, Satishchandra P, Kumar RU, Yasha TC, Santosh V, Chandramuki A, Ravi V, Nath A. Neuropathology of HIV/AIDS with an overview of the Indian scene. Indian J Med Res. 2005;121:468–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strain MC, Letendre S, Pillai SK, Russell T, Ignacio CC, Gunthard HF, Good B, Smith DM, Wolinsky SM, Furtado M, Marquie-Beck J, Durelle J, Grant I, Richman DD, Marcotte T, McCutchan JA, Ellis RJ, Wong JK. Genetic composition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in cerebrospinal fluid and blood without treatment and during failing antiretroviral therapy. J Virol. 2005;79:1772–1788. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1772-1788.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadia RS, Pujari SN, Kothari S, Udhar M, Kulkarni S, Bhagat S, Nanivadekar A. Neurological manifestations of HIV disease. J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:343–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yepthomi T, Paul R, Vallabhaneni S, Kumarasamy N, Tate DF, Solomon S, Flanigan T. Neurocognitive consequences of HIV in southern India: A preliminary study of clade C virus. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2006;12:424–430. doi: 10.1017/s1355617706060516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]