Abstract

Objectives

To examine the association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) deficiency and anemia in a cohort of otherwise healthy children, and to determine whether race modifies the association between 25(OH)D status and hemoglobin (Hgb).

Study design

Cross-sectional study of 10,410 children and adolescents aged 1-21 years from the 2001-2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Anemia was defined as hemoglobin less than the 5th percentile for age and sex based on NHANES III data.

Results

Lower 25(OH)D levels were associated with increased risk for anemia; < 30 ng/mL, adjusted odds ratio (OR) 1.93, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.21, 3.08, p=0.006, and < 20 ng/mL, OR 1.47, 95%CI 1.14-1.89, p=0.004. In linear regression, small but significant increases in Hgb were noted in the upper quartiles of 25(OH)D compared with the lowest quartile (< 20 ng/mL) in the full cohort. Results of race-stratified linear regression by 25(OH)D quartile in white children were similar to those observed in the full cohort, but in black children, increase in Hgb in the upper 25(OH)D quartiles was only apparent compared with the lowest black race specific quartile (<12 ng/mL).

Conclusions

25(OH)D deficiency is associated with increased risk of anemia in a healthy U.S. children, but the 25(OH)D threshold levels for lower Hgb are lower in black children in comparison with white children.

Deficiency of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) is highly prevalent in U.S. children and adolescents, seen in 70% of those ≤ 21 years.1,2 Non-Hispanic black children and adults have a higher prevalence of 25(OH)D deficiency than non-Hispanic whites.1,3,4 25(OH)D is known for its crucial role in bone and mineral metabolism, and is increasingly recognized to have extra-skeletal effects on immune function, cell proliferation and differentiation, and cardiovascular function.5,6 A growing body of evidence suggests that 25(OH)D deficiency is also associated with increased risk for anemia, a common condition experienced by up to 20% of children.7 Lower 25(OH)D levels have been independently associated with lower hemoglobin (Hgb) levels and anemia in adults with heart failure, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) (including dialysis-dependent CKD).8-12 This association has also been observed in otherwise healthy adults 13, and in adults aged 60 years and older in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).14 However, this association has not been explored in healthy children.

The objective for this study was to examine the association of 25(OH)D levels with Hgb levels and anemia status in a nationally representative sample of U.S children. In addition, given differences in 25(OH)D deficiency by race, we sought to examine whether race modifies the association between 25(OH)D status and Hgb.

Methods

NHANES 2001-2006 is a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of the civilian, non-institutionalized US population aged 2 months and older performed by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). NHANES 2001-2006 consisted of an in-home interview followed by a medical evaluation and blood sample collection at a mobile examination center. Within NHANES, Hgb was measured in all children > 1 year of age in each study year and 25(OH)D levels were measured in those aged ≥ 6 years from 2001-2002 and in those aged ≥ 1 year from 2003-2006. Of 14,815 children 1 to < 21 years included in NHANES 2001-2006, children and adolescents missing data on 25(OH)D levels (n=1172), Hgb (n=2612), C-reactive protein (CRP) (n=163), serum folate (n=33), vitamin B12 (n=119), or body mass index (BMI) (n=134) were excluded from this analysis. NHANES 2001-2006 was approved by the NCHS Institutional Review Board, and all participants ≥ 18 years of age provided written informed consent. Consent was obtained from guardians of children < 18 years of age, with assent obtained from those 12-17 years.

Demographic variables in the current analysis include age, sex, and race/ethnicity, categorized as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican-American, Hispanic non-Mexican, and other. Race/ethnicity data was collected by self-report or, for those < 12 years of age, by parent/guardian report. Each participant’s height and weight was measured during the examination, and BMI was calculated. BMI percentiles were determined based on the CDC’s BMI-for-age sex-specific growth charts.15 Obesity was defined as BMI > 95th percentile for age and sex, or BMI > 30 in those aged ≥ 18 years.

Hgb was determined with a Coulter Counter Model S-Plus JR (Coulter Electronics). Anemia was defined as Hgb value less than the age- and sex-specific 5th percentile values established in NHANES III (http://www.kidney.org/professionals/KDOQI/guidelines_anemia/images/tables/table39.jpg).16 In the 25(OH)D quartile analysis, we elected to focus on the association of 25(OH)D levels with Hgb specifically, rather than the risk for anemia, as the definition of “anemia” in individuals of black vs. white race is the subject of some debate.17-24 25(OH)D was measured at the National Center for Environmental Health, CDC, Atlanta, GA using the DiaSorin radioimmunoassay (RIA) kit (DiaSorin, Stillwater, MN). To account for observed drifts in the 25(OH)D assay performance (secondary to reagent and calibration lot changes) observed over the period of 2003-2006 compared with 2001-2002, the 2003-2006 data were adjusted by NHANES.25 As a result, 2003-2004 25(OH)D data were adjusted to lower values and 2005-2006 data to higher values than initially observed.25 25(OH)D values of < 20 and < 30 ng/mL defined the thresholds of deficiency and insufficiency, respectively.2 High-sensitivity CRP was measured by latex-enhanced nephelometry, with normal values defined as ≤ 0.5 mg/dL.26 Serum folate (normal values ≥ 3 ng/dL) and vitamin B12 (normal values ≥ 200 pg/mL) were measured with the Quantaphase Folate radioassay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories).26 Serum B12 in the 2001-2002 cohort was available only for children aged > 3 years, but for all ages in 2003-2006.

Variables utilized in secondary analyses included serum ferritin, measured with the Quantimmune Ferritin IRMA kid (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and serum iron and total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), measured colorimetrically (Alpkem RFA Analyzer). Transferrin saturation (TSAT) was calculated as the serum iron divided by the TIBC. Serum ferritin, iron and TIBC were measured in all subjects in NHANES 2001-2002, and limited to those aged 3-5 years and female subjects ≥ 12 years in 2003-2006. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was estimated using the bedside equation from the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children (CKiD) Study for those <18 years of age, and the CKD-EPI equation for those greater than or equal to 18 years of age.27,28 Serum creatinine is not measured in NHANES participants < 12 years of age. Family poverty income ratio is calculated by NHANES as a ratio of reported family income to poverty threshold according to family size, state of residence and year as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau, and was included as a socioeconomic indicator.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata statistical software, version 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Survey commands were used to account for the NHANES complex sampling design. The statistical significance level was set at α = 0.05. All statistical analyses were 2-sided. Descriptive statistics are reported as mean and standard error, median and interquartile range (IQR), or proportions as noted. Mean 25(OH)D concentrations according to subgroups were compared by independent sample t tests. Logistic regression was used to examine the association of 25(OH)D deficiency or insufficiency with anemia with adjustment for age, sex, race, obesity, CRP, and serum B12 and folate. Linear regression was used to examine the association of 25(OH)D quartiles (whole population and race-specific) with Hgb. In secondary analyses, we performed logistic regressions as described above in only those subjects with available markers of iron stores, and in those with available creatinine data to calculate eGFR.

Results

There were 10,410 children included in the analysis. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort overall and by race are presented in Table I. Mean (SE) weighted age of participants was 11.8 (0.13) years, 51.7% were male, 60.8% white, and 14.8% black. Seventeen percent were obese, with a significantly higher proportion of black children meeting criteria for obesity compared with whites (21.5% vs. 15.5%, p<0.001). The median (IQR) 25(OH)D level in the overall cohort was 25 (20, 30). Median (IQR) 25(OH)D was 27 (23, 33) in white subjects vs. 17 (12,22) in black subjects. The overall prevalence of anemia was 4.2%, but this also differed by race with 2.1% of white children meeting criteria for anemia vs. 14.3% of black children (p<0.001). There was no difference in mean CRP by racial group, although a slightly higher proportion of black children demonstrated CRP > 0.5mg/dL (p=0.04).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) levels and anemia status in U.S. children 1- <21 years of age, NHANES1 2001-2006

| Total (n=10,410) |

Black (n=3364) |

White (n=2894) |

p-value (B vs.W) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean, se) | 11.8 (0.13) | 11.8 (0.19) | 12.0 (0.19) | 0.40 |

| Male,% | 51.7 (0.67) | 50.9 (1.18) | 52.1 (1.04) | 0.47 |

| Race/Ethnicity, % | ||||

| Mexican | 12.9 (1.26) | |||

| Hisp, Non-Mexican | 5.4 (0.76) | |||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 60.8 (2.17) | |||

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 14.8 (1.40) | |||

| Other race | 6.0 (0.73) | |||

| Obese, % | 17.0 (0.76) | 21.5 (0.98) | 15.5 (1.04) | <0.001 |

| 25(OH)D, ng/mL (mean, se) | 25.4 (0.33) | 17.6 (0.39) | 28.2 (0.36) | <0.001 |

| 25(OH)D, ng/mL (median, IQR3) | 25 (20, 30) | 17 (12, 22) | 27 (23,33) | |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL (mean, se) | 13.9 (0.04) | 13.2 (0.03) | 14.0 (0.05) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL (median, IQR) | 13.7 (12.9, 14.7) | 13.0 (12.3, 13.9) | 13.9 (13.1, 14.9) | |

| % Anemic4 | 4.2 (0.39) | 14.3 (0.77) | 2.1 (0.36) | <0.001 |

| CRP5, mg/dL (mean, se) | 0.17 (0.01) | 0.18 (0.01) | 0.16 (0.01) | 0.25 |

| % CRP > 0.5 mg/dL | 7.4 (0.38) | 8.3 (0.49) | 6.8 (0.51) | 0.04 |

| Vitamin B12, pg/mL (mean, se) | 662.8 (6.23) | 750.3 (8.29) | 632.1 (7.63) | <0.001 |

| % Vitamin B12 < 200 pg/mL | 0.36 (0.066) | 0.30 (0.075) | 0.38 (0.091) | 0.41 |

| Folate, ng/mL (mean, se) | 14.91 (0.18) | 13.45 (0.21) | 15.56 (0.25) | <0.001 |

| % Folate < 3 ng/mL | 0.063 (0.029) | 0.022 (0.022) | 0.056 (0.041) | 0.46 |

| IRON MARKERS6 | (n=911) | (n=736) | ||

| Ferritin, ng/mL (mean, se) | 37.05 (0.96) | 39.98 (2.47) | 36.45 (1.16) | 0.20 |

| % low ferritin | 15.62 (0.0086) | 16.35 (0.011) | 15.23 (0.013) | 0.52 |

| Iron, mcg/dL (mean, se) | 79.88 (1.17) | 72.14 (1.01) | 82.54 (1.72) | 0.0001 |

| % low iron | 22.24 (0.012) | 25.67 (0.016) | 21.04 (0.017) | 0.070 |

| TSAT7, % (mean, se) | 22.27 (0.30) | 20.37 (0.33) | 23.04 (0.43) | 0.0002 |

| % low TSAT | 22.65 (0.010) | 26.07 (0.016) | 21.17 (0.015) | 0.045 |

NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

BMI, body mass index

IQR, interquartile range

Anemia defined as hemoglobin less than 5th percentile for age and sex

CRP, C-reactive protein

Subcohort, n=2763 (911 black, 736 white)

Transferrin saturation

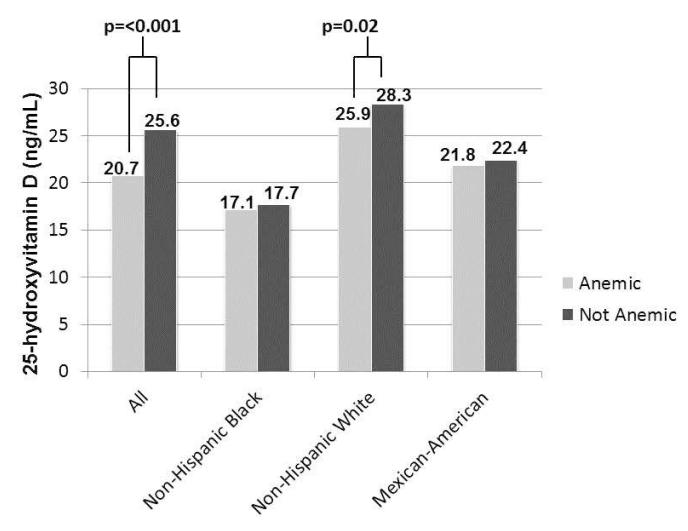

Figure 1 demonstrates mean 25(OH)D levels by race/ethnicity and anemia status in the cohort. There was a trend for mean 25(OH)D levels to be consistently lower in the anemic children compared with the non-anemic children across racial/ethnic groups. The difference in mean 25(OH)D levels by anemia status reached statistical significance in the overall cohort (p<0.001) and in the non-Hispanic white subjects (p=0.02).

Figure 1.

Mean 25(OH)D levels otherwise healthy children aged 1-<21 years by anemia status and race/ethnicity (n=10,410)

The associations between 25(OH)D level, modeled categorically and linearly, and anemia are summarized in Table II. The odds ratio for anemia for those with 25(OH)D levels < 30 ng/mL, compared with ≥ 30, was 1.93 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.21, 3.08, p=0.006) in fully adjusted analyses. For those with 25(OH)D levels < 20 ng/mL, compared with ≥ 20, the adjusted odds ratio for anemia was 1.47 (95% CI 1.14, 1.89, p=0.004). The odds ratio for anemia for each 1 ng/mL increase in 25(OH)D was 0.97 (95% CI 0.95, 0.99, p=0.009).

Table 2.

Logistic regression models demonstrating association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) and anemia1 in U.S. children 1- <21 years (n=10410)

| Risk for anemia in children with 25(OH)D < 30 ng/ml (vs. ≥ 30) | ||

|

| ||

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|

| ||

| Unadjusted | 3.33 (2.12, 5.22) | <0.001 |

| Adjusted* | 1.97 (1.23, 3.16) | 0.006 |

| Fully adjusted** | 1.93 (1.21, 3.08) | 0.006 |

|

| ||

| Risk for anemia in children with 25(OH)D < 20 ng/ml (vs. ≥ 20) | ||

|

| ||

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|

| ||

| Unadjusted | 3.25 (2.53, 4.17) | <0.001 |

| Adjusted* | 1.53 (1.20, 1.96) | 0.001 |

| Fully adjusted** | 1.47 (1.14, 1.89) | 0.004 |

|

| ||

| Risk for anemia by increasing 25(OH)D level ** | ||

|

| ||

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|

| ||

| Per 1 ng/mL increase in 25(OH)D | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99) | 0.009 |

| Per doubling of 25(OH)D (ng/mL) | 0.74 (0.58, 0.93) | 0.013 |

Anemia defined as hemoglobin less than 5th percentile for age and sex

Model adjusted for age, sex, race, and obesity

Model adjusted for age, sex, race, obesity, CRP, B12, and folate

In a secondary logistic regression analysis including subjects with available ferritin, iron and TSAT levels (n=2763), those with 25(OH)D < 30 ng/mL compared with ≥ 30 continued to have an increased risk for anemia (OR 3.51, 95% CI 1.28, 9.62, p=0.016). The trend was similar for those with 25(OH)D levels < 20 ng/mL, although statistical significance was not reached (OR 1.47, 95% CI 0.87, 2.48, p=0.14). Among those subjects with eGFR available (n=6154), very few demonstrated values consistent with CKD; only 0.004% had eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73m2, a GFR cut-off most often used to define CKD in adults and below which anemia related to CKD becomes prevalent.29 In this subgroup, logistic regression modeling continued to demonstrate increased risk for anemia in those with 25(OH)D < 30 ng/mL compared with ≥ 30 (OR 2.68, 95% CI 1.31, 5.50, p=0.008) and with 25(OH)D levels < 20 ng/mL vs. ≥ 20 (OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.10, 2.20, p=0.014). Further adjustment for family poverty income ratio as an indicator of socioeconomic status (n=9926) did not change the results significantly; increased risk for anemia was still demonstrated in those with 25(OH)D < 30 ng/mL compared with ≥ 30 (OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.16, 2.99, p=0.011) and with 25(OH)D levels < 20 ng/mL vs. ≥ 20 (OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.14, 1.90, p=0.004).

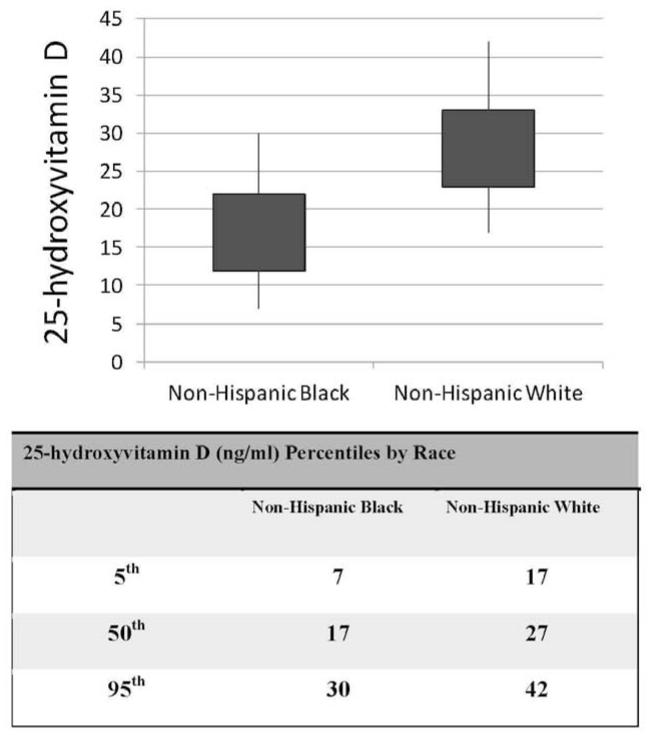

A strikingly lower distribution of 25(OH)D values was noted among black (50th%ile 17 ng/mL, 95th%ile 30 ng/mL) compared with white (50th%ile 27 ng/mL, 95th%ile 42 ng/mL) children in the cohort (Figure 2; available at www.jpeds.com). To examine the extent to which race modifies the observed association between 25(OH)D level and Hgb, we performed a linear regression by 25(OH)D quartile stratified by race (Table III). Using whole population quartile values in the full cohort, significant increases in Hgb were noted in each of the upper 25(OH)D quartiles compared with the 1st quartile of 25(OH)D < 20 ng/mL. In a race-stratified analysis, the magnitude and significance of the increase in Hgb seen in the upper 25(OH)D quartiles in the white children was consistent with increases observed in the whole population. However, in the black children no significant change in Hgb was observed in the higher quartiles compared with lowest 25(OH)D quartile. We then conducted a regression analysis in the black children using the non-Hispanic-black race-specific 25(OH)D quartiles (Table IV; available at www.jpeds.com). This demonstrated increases in Hgb in higher 25(OH)D quartiles compared with the lowest quartile, which were of similar magnitude to the increases observed in the quartile analysis for white children: 2nd vs. 1st (< 12 ng/ml) quartile, Hgb increased by 0.240 (95% CI 0.096, 0.384) g/dL, p=0.002; 3rd vs. 1st quartile, Hgb increased by 0.116 (95%CI −0.019, 0.251) g/dL, p=0.091; and 4th vs. 1st quartile, Hgb increased by 0.146 (95%CI 0.025, 0.267) g/dL, p=0.019.

Figure 2.

Frequency and percentile distributions of 25(OH)D (ng/mL) levels in black and white U.S. children 1- <21 years of age, NHANES 2001-2006 (n=6258)

Table 3.

Change in hemoglobin associated with 25(OH)D WHOLE POPULATION quartiles (ng/mL) in all children, and in children of white and black race (1st quartile < 20 referent)*

|

25(OH)D Quartile (ng/mL)

(1st quartile referent) ALL CHILDREN (n=10,410) |

Hemoglobin, g/dL (95% CI) | p-value |

| 2nd (20-25 ng/mL) | 0.196 (0.114, 0.278) | <0.001 |

| 3rd (25-30 ng/mL) | 0.168 (0.076, 0.260) | 0.001 |

| 4th (> 30 ng/mL) | 0.179 (0.071, 0.286) | 0.002 |

|

25(OH)D Quartile (ng/mL)

(1st quartile referent) WHITE CHILDREN (n=2894) |

Hemoglobin, g/dL (95% CI) | p-value |

| 2nd (20-25 ng/mL) | 0.194 (0.051, 0.338) | 0.009 |

| 3rd (25-30 ng/mL) | 0.179 (0.032, 0.326) | 0.018 |

| 4th (> 30 ng/mL) | 0.160 (0.011, 0.309) | 0.036 |

|

25(OH)D Quartile (ng/mL)

(1st quartile referent) BLACK CHILDREN (n=3364) |

Hemoglobin, g/dL (95% CI) | p-value |

| 2nd (20-25 ng/mL) | −0.013 (−0.109, 0.083) | 0.788 |

| 3rd (25-30 ng/mL) | −0.013 (−0.120, 0.095) | 0.815 |

| 4th (> 30 ng/mL) | 0.032 (−0.170, 0.234) | 0.751 |

Models adjusted for age, sex, obesity, CRP, B12, and folate

Table 4.

Change in hemoglobin associated with 25(OH)D BLACK POPULATION-SPECIFIC quartiles (ng/mL) in black children (1st quartile < 12 referent)*

|

25(OH)D Quartile (ng/mL)

(1st quartile referent) BLACK CHILDREN (n=3364) |

Hemoglobin, g/dL (95% CI) | p-value |

| 2nd (12-17 ng/mL) | 0.240 (0.096, 0.384) | 0.002 |

| 3rd (17-22 ng/mL) | 0.116 (−0.019, 0.251) | 0.091 |

| 4th (> 22 ng/mL) | 0.146 (0.025, 0.267) | 0.019 |

Model adjusted for age, sex, obesity, CRP, B12, and folate

Discussion

This study demonstrates that in a large, population-based cohort of healthy U.S. children, lower 25(OH)D levels were associated with increased risk for anemia. The observed association between vitamin D status and anemia was independent of other factors which may contribute to anemia risk including obesity, inflammation, socioeconomic status, and nutritional status including B12, folate, and iron deficiency. Furthermore, an association between 25(OH)D level and Hgb was observed in children of both black and white race, but the 25(OH)D levels at which this association becomes apparent differ by race, and were lower in black children. Among white subjects, 25(OH)D levels in the upper quartiles (≥ 20 ng/mL) were associated with a nearly 0.2 g/dL higher Hgb compared with those < 20 ng/mL, and in black children, Hgb was higher among those with 25(OH)D levels above 11ng/mL.

Vitamin D has long been recognized for its role in regulating calcium, phosphorus, and bone metabolism, but in recent years has received attention as a regulator of a variety of biological functions including immune function, cellular proliferation, and cardiovascular function.5,30,31 An accumulating body of evidence suggests that 25(OH)D deficiency may also play a role in the pathogenesis of anemia. Lower 25(OH)D levels have been associated with anemia/lower Hgb values in population-based samples of U.S. adults 13,14, and in adults with non-dialysis CKD and end-stage kidney disease 9,10,32-34, end-stage heart failure12, and Type 2 diabetes11. Furthermore, retrospective cohort studies in adults with CKD have demonstrated that vitamin D supplementation may improve anemia management and decrease dose requirements for erythropoiesis stimulating agents (ESA), suggesting that vitamin D plays a role in erythropoiesis.32,33 Among anemic patients with non-dialysis CKD treated with ESAs, ergocalciferol supplementation to normalize 25(OH)D values to ≥ 30 ng/mL was associated with a 24% decrease in the ESA dose required to maintain Hgb in the range of 11-12 g/dL.32 In a study of greater than 100 adults on chronic hemodialysis, ergocalciferol supplementation to normalize 25(OH)D was associated with a decrease in the ESA dose required to maintain Hgb targets in the majority of subjects.33

There are several possible mechanisms to explain the association of vitamin D deficiency with anemia. Vitamin D deficiency in children has been shown to be associated with lifestyle and nutritional factors such as obesity and decreased milk intake.1 However, in the present study, the association between 25(OH)D status and anemia remained after adjustment for obesity and additional markers of nutritional status including B12 and folate levels and, in a sub-cohort of children, iron markers, suggesting that there are other explanatory mechanisms. Vitamin D and its metabolites are present in many tissues, as are the receptors for the active form of vitamin D, calcitriol. Although calcitriol production for the regulation of bone mineral metabolism takes place via the action of the 1-α-hydroxylase enzyme in renal tissue, there are multiple extra-renal sites where locally-produced calcitriol regulates host-cell DNA, and from which the extra-skeletal actions of vitamin D are controlled.5,35 There are data to suggest that inadequate levels of 25(OH)D leading to decreased local calcitriol production in the bone marrow may limit erythropoiesis; calcitriol has a direct proliferative effect on erythroid burst forming units which is synergistic with endogenously produced erythropoietin, and it also upregulates expression of the erythropoietin receptor on erythroid progenitor cells.33,36,37.

Calcitriol also plays a key role in the regulation of immune function by inhibiting the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines by a variety of immune cells, thus providing negative feedback to prevent excessive inflammation.5 The immunomodulatory effects of vitamin D may be central to its role in preventing anemia via modulation of systemic cytokine production, which may in turn suppress specific inflammatory pathways which contribute to the development of anemia. In a study of adults aged ≥ 60 years in NHANES, Perlstein et al demonstrated an association between vitamin D deficiency and anemia which became statistically significant at a 25(OH)D level of 24 ng/mL. Additionally, they found a strong association between vitamin D deficiency and anemia of inflammation compared with both non-anemic subjects and subjects with other anemia subtypes.14 Interestingly, they also found that among subjects with anemia of inflammation, non-Hispanic blacks were overrepresented, comprising nearly 44% of the group.14 Although we controlled for CRP in our multivariate models, it may not be the most sensitive marker of inflammation in children who could have a variety of infectious stimuli causing transient decreases in Hgb including viral infections. It is possible that there are other inflammatory mediators, unmeasured in the pediatric NHANES cohort, which are associated with lower levels of 25(OH)D. The role of inflammation in the etiology of anemia has been further clarified through study of the iron-regulatory protein hepcidin, an inflammation-induced negative regulator of erythropoiesis.38,39. Low levels of calcitriol have been found to be associated with increased hepcidin levels in adults with CKD.40

Our finding that the 25(OH)D threshold above which Hgb increases differs by race suggests a possible differential sensitivity to the effects of vitamin D by race. This finding is not unique to hemoglobin, as recently published NHANES studies have also demonstrated racial variation in 25(OH)D threshold for other adverse health effects. In a study of adults in NHANES 2003-2006, bone mineral density was significantly decreased in those with lower levels of 25(OH)D among non-Hispanic whites, but not in non-Hispanic blacks41, and another community-based study found that black women have an increase in serum parathyroid hormone levels at lower 25(OH)D levels than white women.42 In adults in NHANES III, 25(OH)D deficiency (defined as level < 15 ng/mL was associated with an increased risk of fatal stroke in non-Hispanic whites, but not in blacks.43 Total 25(OH)D levels have not been consistently correlated with bone mineral density in the literature, and bioavailable vitamin D, which is the fraction of circulating 25(OH)D that is unbound to either vitamin D binding protein or albumin and is thus available to effect biologic actions, is strongly correlated with bone mineral density.44 A recent study performed in a small cohort of healthy young adults revealed that mean levels of the vitamin D binding protein were significantly lower in non-white subjects compared with white subjects, with a trend towards increased bioavailable vitamin D among the non-white subjects.44 Thus the variation by race in total 25(OH)D levels at which certain adverse health effects are observed may be explained by racial differences in bioavailability of vitamin D..

Our study has several strengths, including a nationally representative, population based sample of children and adolescents, and standardized data collection and quality control procedures. This is a cross-sectional study, and thus the association between vitamin D deficiency and lower Hgb cannot be assumed to be causal. We did not have access to data on iron deficiency, one of the most common causes of anemia in children, in the majority of subjects, but sensitivity analyses conducted among subjects with iron data showed similar direction and magnitude of associations between 25(OH)D deficiency and anemia. Hereditary hemoglobinopathies may be associated with lower Hgb levels, particularly in black children, but we did not have access to data to estimate the prevalence of these traits. NHANES does not analyze vitamin D binding protein, preventing the determination of bioavailable 25(OH)D.

Acknowledgments

M.K. was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Diseases (K23-DK-084116). M.M. was supported by NIDDK (K23-DK-078774), NIH (R01 DK087783), and the American Society of Nephrology (Carl W. Gottschalk Research Scholar Grant). The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Abbreviations

- 25(OH)D

25-hydroxyvitamin D

- BMI

body mass index

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- ESA

erythropoiesis stimulating agent

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- Hgb

hemoglobin

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- TSAT

transferrin saturation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Portions of this study were presented as a poster at the Pediatric Academic Societies’ Meeting, Denver, CO, May 2011.

References

- 1.Kumar J, Muntner P, Kaskel FJ, Hailpern SM, Melamed ML. Prevalence and associations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency in US children: NHANES 2001-2004. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e362–70. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melamed ML, Astor B, Michos ED, Hostetter TH, Powe NR, Muntner P. 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, race, and the progression of kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2631–2639. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009030283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reis JP, von Muhlen D, Miller ER, 3rd, Michos ED, Appel LJ. Vitamin D status and cardiometabolic risk factors in the united states adolescent population. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e371–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bikle D. Nonclassic actions of vitamin D. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:26–34. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shroff R, Knott C, Rees L. The virtues of vitamin D--but how much is too much? Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:1607–1620. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1499-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polhamus B, Dalenius K, Thompson D, Scanlon K, Borland E, Smith B, et al. Pediatric nutrition surveillance. Nutr Clin Care. 2003;6:132–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kendrick J, Targher G, Smits G, Chonchol M. 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency and inflammation and their association with hemoglobin levels in chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2009;30:64–72. doi: 10.1159/000202632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiss Z, Ambrus C, Almasi C, Berta K, Deak G, Horonyi P, et al. Serum 25(OH)-cholecalciferol concentration is associated with hemoglobin level and erythropoietin resistance in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Nephron Clin Prac. 2011;117:c373–8. doi: 10.1159/000321521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel NM, Gutierrez OM, Andress DL, Coyne DW, Levin A, Wolf M. Vitamin D deficiency and anemia in early chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2010;77:715–720. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meguro S, Tomita M, Katsuki T, Kato K, Oh H, Ainai A, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin d is independently associated with hemoglobin concentration in male subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Endocrinol. 2011;2011:362981. doi: 10.1155/2011/362981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zittermann A, Jungvogel A, Prokop S, Kuhn J, Dreier, Fuchs U, et al. Vitamin D deficiency is an independent predictor of anemia in end-stage heart failure. Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100:781–788. doi: 10.1007/s00392-011-0312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sim JJ, Lac PT, Liu IL, Meguerditchian SO, Kumar VA, Kujubu DA, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and anemia: A cross-sectional study. Ann Hematol. 2010;89:447–452. doi: 10.1007/s00277-009-0850-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perlstein TS, Pande R, Berliner N, Vanasse GJ. Prevalence of 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency in subgroups of elderly persons with anemia: Association with anemia of inflammation. Blood. 2011;117:2800–2806. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-309708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Accessed October 19, 2012];<br />Body mass index (BMI)-for-age charts for boys and girls aged 2 to 20 years. http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/html_charts/bmiagerev.htm. Updated 2001.

- 16.KDOQI clinical practice guidelines and clinical practice recommendations for anemia in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47:S1–S146. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel KV, Longo DL, Ershler WB, Yu B, Semba RD, Ferrucci L, et al. Haemoglobin concentration and the risk of death in older adults: Differences by race/ethnicity in the NHANES III follow-up. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:514–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07659.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robins EB, Blum S. Hematologic reference values for african american children and adolescents. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:611–614. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkinson MA, Pierce CB, Zack RM, Barletta GM, Yadin O, Mentser M, et al. Hemoglobin differences by race in children with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:1009–1017. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perry GS, Byers T, Yip R, Margen S. Iron nutrition does not account for the hemoglobin differences between blacks and whites. J Nutr. 1992;122:1417–1424. doi: 10.1093/jn/122.7.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reed WW, Diehl LF. Leukopenia, neutropenia, and reduced hemoglobin levels in healthy american blacks. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:501–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan WH, Habicht JP. The non-iron-deficiency-related difference in hemoglobin concentration distribution between blacks and whites and between men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:1410–1416. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beutler E, West C. Hematologic differences between african-americans and whites: The roles of iron deficiency and alpha-thalassemia on hemoglobin levels and mean corpuscular volume. Blood. 2005;106:740–745. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beutler E, Waalen J. The definition of anemia: What is the lower limit of normal of the blood hemoglobin concentration? Blood. 2006;107:1747–1750. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics [Accessed November/29, 2012];Revised analytical note for NHANES 200-2006 and NHANES III (1988-1994) 25-hydroxyvitamin D analysis (revised november 2010) http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes3/VitaminD_analyticnote.pdf. Updated 2010.

- 26.Custer JW, Custer J.w., Rau RE. The harriet lane handbook. 18th ed Mosby Inc.; Philadelphia, PA: 2009. Blood chemistries and body fluids; p. 682. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz GJ, Munoz A, Schneider MF, Mak RH, Kaskel F, Warady BA, et al. New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:629–37. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fadrowski JJ, Pierce CB, Cole SR, Moxey-Mims M, Warady BA, Furth SL. Hemoglobin decline in children with chronic kidney disease: Baseline results from the chronic kidney disease in children prospective cohort study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:457–62. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03020707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baeke F, Gysemans C, Korf H, Mathieu C. Vitamin D insufficiency: Implications for the immune system. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:1597–1606. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1452-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams JS, Hewison M. Unexpected actions of vitamin D: New perspectives on the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008;4:80–90. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lac PT, Choi K, Liu IA, Meguerditchian S, Rasgon SA, Sim JJ. The effects of changing vitamin D levels on anemia in chronic kidney disease patients: A retrospective cohort review. Clin Nephrol. 2010;74:25–32. doi: 10.5414/cnp74025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saab G, Young DO, Gincherman Y, Giles K, Norwood K, Coyne DW. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and the safety and effectiveness of monthly ergocalciferol in hemodialysis patients. Nephron Clin Pract. 2007;105:c132–8. doi: 10.1159/000098645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar VA, Kujubu DA, Sim JJ, Rasgon SA, Yang PS. Vitamin D supplementation and recombinant human erythropoietin utilization in vitamin D-deficient hemodialysis patients. J Nephrol. 2011;24:98–105. doi: 10.5301/jn.2010.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Armas LA, Heaney RP. Vitamin D: The iceberg nutrient. J Ren Nutr. 2011;21:134–139. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alon DB, Chaimovitz C, Dvilansky A, Lugassy G, Douvdevani A, Shany S, et al. Novel role of 1,25(OH)(2)D(3) in induction of erythroid progenitor cell proliferation. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:403–409. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00789-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aucella F, Scalzulli RP, Gatta G, Vigilante M, Carella AM, Stallone C. Calcitriol increases burst-forming unit-erythroid proliferation in chronic renal failure. A synergistic effect with r-HuEpo. Nephron Clin Pract. 2003;95:c121–7. doi: 10.1159/000074837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nemeth E. Targeting the hepcidin-ferroportin axis in the diagnosis and treatment of anemias. Adv Hematol. 2010;2010:750643. doi: 10.1155/2010/750643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy CN, Andrews NC. Anemia of inflammation: The hepcidin link. Curr Opin Hematol. 2005;12:107–11. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200503000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carvalho C, Isakova T, Collerone G, Olbina G, Wolf M, Westerman M, et al. Hepcidin and disordered mineral metabolism in chronic kidney disease. Clin Nephrol. 2011;76:90–98. doi: 10.5414/cn107018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gutierrez OM, Farwell WR, Kermah D, Taylor EN. Racial differences in the relationship between vitamin D, bone mineral density, and parathyroid hormone in the national health and nutrition examination survey. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:1745–1753. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1383-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aloia JF, Chen DG, Chen H. The 25(OH)D/PTH threshold in black women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:5069–5073. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michos ED, Reis JP, Post WS, Lutsey PL, Gottesman RF, Mosley TH, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency is associated with fatal stroke among whites but not blacks: The NHANES-III linked mortality files. Nutrition. 2012;28:367–371. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Powe CE, Ricciardi C, Berg AH, Erdenesanaa D, Collerone G, Ankers E, et al. Vitamin D-binding protein modifies the vitamin D-bone mineral density relationship. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1609–1616. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]