Abstract

The retinoblastoma proteinC-terminal domain (RbC) is necessary for the tumor suppressor protein's activities in growth suppression and E2F transcription factor inhibition. Cyclin-dependent kinase phosphorylation of RbC contributes to Rb inactivation and weakens the Rb-E2F inhibitory complex. Here we demonstratetwo mechanisms for how RbC phosphorylation inhibits E2F binding. We find that phosphorylation of S788 and S795 weakens the direct association between the N-terminal portion of RbC (RbCN) and the marked-box domains of E2F and its heterodimerization partner DP. Phosphorylation of these sites and S807/S811 also induces an intramolecular association between RbC and the pocket domain,which overlaps with the site of E2F transactivation domain binding. Areduction in E2F binding affinity occurs with S788/S795 phosphorylation that is additive with the effects of phosphorylation at other sites, and we propose a structural mechanism that explains this additivity. We find that different Rb phosphorylation events have distinct effects on activating E2F family members, which suggests a novel mechanism for how Rb may differentially regulate E2F activities.

Keywords: Cell cycle regulation, multisite phosphorylation, cyclin-dependent kinases, Rb protein, protein-protein interactions

Introduction

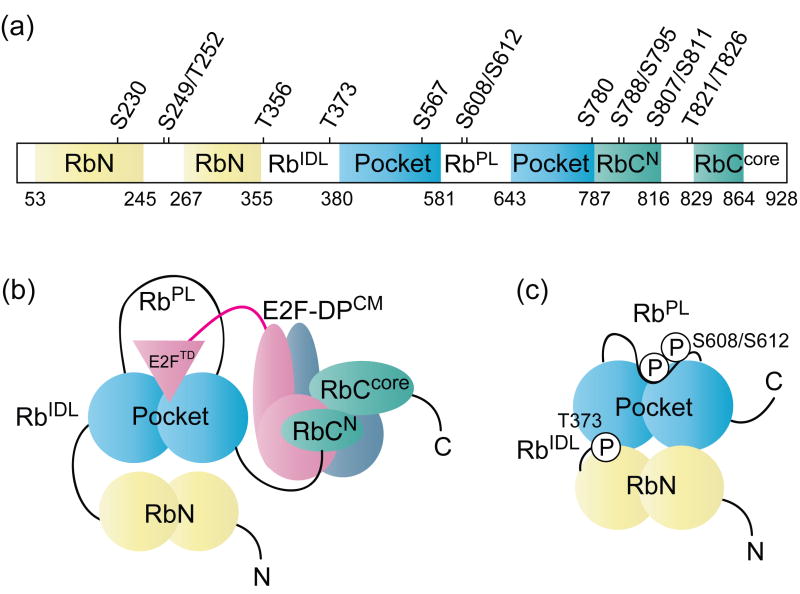

The retinoblastoma protein (Rb) is a broad-functioning tumor suppressor that is frequently deregulated in human cancers.1;2 The loss of functional Rb is associated with several hallmarks of cancer including chromosomal instability and aberrant cell proliferation. Rb acts as a negative regulator of cell division at the G1-S transition of the cell cycle.3;4;5;6 In G0 and early G1, Rb forms a growth-repressive complex with E2F transcription factors.7;8 The Rb-E2F complex is stabilized through two cohesive interactions (Fig. 1a and 1b): the pocket domain of Rb binds and represses the E2F transactivation domain (E2FTD),9;10;11 and the C-terminal domain of Rb (RbC) associates with the E2F1-DP1 marked-box and coiled-coil domains (E2F1-DP1CM).12;13;14 These structured interactions are consistent with the finding that both the pocket domain and RbC are required for full growth suppression and E2F binding.15;16;17

Fig. 1.

Schematic of Rb protein structure.(a)Domain organization and Cdk-consensus phosphorylation sites. Structured domains are colored, unstructured domains are uncolored, and domain boundaries used in this study are indicated. (b) Summary of interactions that contribute to the overall Rb-E2F complex. The Rb pocket domain bindsthe E2F transactivation domain (E2FTD), while the Rb C-terminal domain (RbC) binds the E2F-DP coiled-coil and marked box (E2F-DPCM) domains.(c) Summary of phosphorylation events and their structural effects that disrupt the Rb-E2FTD complex. Phosphorylation of S608/S612 in the pocket loop (RbPL) induces binding of RbPL to the pocket at the E2FTD site. Phosphorylation of T373 in the interdomain linker (RbIDL) induces N-terminal domain (RbN) docking tothe pocket,which allosterically disrupts the E2FTD-binding cleft.

Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) phosphorylate Rb at specific CDK-consensus sites in late G1(Fig. 1).3;4;5;6;18;19;20;21 Hyperphosphorylated Rb dissociates from E2F, allowing for up-regulation of E2F-mediated transcription and entry into S-phase.15;22;23 Protein crystal structures have revealed how several key phosphorylation events induce conformational changes to Rb that disrupt the Rb-E2F interfaces(Fig. 1c).24 Phosphorylation of S608/S612 in the pocket loop (RbPL) promotes a binding interaction between RbPL and the pocket domain that is structurally analogous to the Rb-E2FTD binding interaction.25;26 Phosphorylation of T373 in the interdomain linker (RbIDL) stabilizes binding between the pocket domain and the N-terminal domain (RbN), inducing an allosteric change to the E2FTD binding site in the pocket.26;27 Phosphorylation of T821 and T826 in RbC also induces an intramolecular association between RbC and the pocket at the ‘LxCxE’ binding site;14;28;29 data suggest that this interaction dissociates proteins involved in chromatin remodeling and gene silencing.28 Quantitative binding studies have revealed that phosphorylation of sites in RbC also reduces binding between RbC and E2F1-DP1CM, although this inhibitory mechanism has not been clarified.14

RbC phosphorylation is a critical component of E2F activation and is necessary for full transactivation activity at E2F-bound promoters.30;31 We therefore sought here to determine whether RbC phosphorylation destabilizes binding between Rb and the E2F transactivation domain. In this study, we use isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to observe phosphorylation-dependent changes in binding between Rb and E2F. We find that phosphorylation of S788 and S795 in the N-terminal region of RbC (RbCN) inhibits the Rb-E2FTDassociationbyinducing binding of RbCNto the pocket domain. In addition, phosphorylation of RbCN abrogates the association between RbCN and the E2F1-DP1CM complex. We find that phosphorylation of RbCN at S788/S795 is additive to the effects of RbIDL and RbPL phosphorylation in inhibiting Rb-E2FTD binding, indicating structural compatibilities exist between these distinct mechanisms. Finally, we identify differences in how these phosphorylation-induced inhibitory mechanisms affect the binding of paralogous ‘activating’ E2FTDs (E2F1-3) to Rb. Together, these binding studies contribute to a complete understanding of how specific post-translational phosphorylation events regulate the distinct functional interfaces of this critical cell cycle regulatory protein.

Results

RbCN (S788/S795) Phosphorylation Inhibits E2F1TD Binding to Rb Pocket by ITC

We used ITC to measure binding affinities of E2F1TD(residues 372-437) for a series of Rb constructs, each engineered to contain specific RbCN phosphorylation sites(Table1 and Supplementary Fig. S1). The proteins were phosphorylated quantitatively with recombinant Cdk as needed (Supplementary Fig. S2). We first tested binding ofE2F1TDto an Rb construct(Rb380-816∆PL/S780A) that contains the pocket domain and 4 phosphoacceptor sites (S788/S795/S807/S811)but lacks the RbPL sites (S608/S612) and S780. S780 phosphorylation does not influence E2FTD binding,25 and the S780A mutation facilitates homogeneous phosphorylation in the preparative in vitro kinase reaction. We found that E2F1TD binds to phosphorylatedRb380-816∆P/S780A (Kd = 0.47 ± 0.04 μM)with an affinity that is 7-fold weaker than its affinity for unphosphorylated protein(Kd = 0.07 ± 0.03μM). When both S807 and S811 are substituted for alanine in this construct, E2F1TD retains the reduced binding affinity for phosphorylated Rb (Kd= 0.51 ± 0.07 μM). This result indicates that S807 and S811 do not contribute to the inhibition of the Rb-E2F1TD interaction.

When S788 and S795 are both substituted to alanine, we find that phosphorylated Rb (Kd=0.13 ± 0.06 μM)binds E2F1TD similar to unphosphorylated Rb(Kd=0.09 ± 0.03 μM), demonstrating that phosphorylation of S788 and S795 negatively affects Rb-E2F1TD binding. Consistent with this result, we observe reduced E2F1TD binding to a phosphorylated construct that is truncated to exclude both S807 and S811 and contains the S780 to alanine mutation. This construct (Rb380-800∆PL/S780A) has only two phosphoacceptor sites intact (S788, S795) and binds E2F1TD 10-fold more weakly when it is phosphorylated (Kd=0.51 ± 0.10 μM) compared to unphosphorylated(Kd=0.05 ± 0.01 μM). A similar construct, truncated to include only phosphorylation at S788 (Rb380-794∆PL/S780A),has a relatively minor effect (Kd=0.27 ± 0.02 μM (phosphorylated), Kd=0.12 ± 0.01 μM (unphosphorylated)). In summary, these results reveal that phosphorylation of RbCN at S788/S795 negatively regulates binding between E2F1TD and the Rb pocket domain.

Phosphorylation of RbCN Induces Binding to Rb Pocket

RbPLphosphorylation on S608/S612 induces an intramolecular association with the pocket domain that overlaps with the E2FTD-binding cleft.25;26 We hypothesized that phosphorylation of RbCN similarly promotes intramolecular binding to the pocket domain. To test this idea, we generated 15N-labeled RbCN peptide (RbC787-816) to detect the associationin trans by NMR. This fragment is phosphorylated on S788, S795, S807, and S811. The 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of the phosphorylated, 15N-labeled RbC787-816 alone shows minimal peak dispersion in the proton dimension, typical of intrinsically disordered polypeptides. Titration of unlabeled Rb pocket into the sample reveals small chemical shift changes and considerable broadening for several peaks (Fig. 2a and 2b). The broadening isprotein concentration dependent (Fig. 2b) and anticipated for binding between the relatively small labeled peptide and the larger unlabeled pocket domain (molecular weight ~43kDa). Binding between phosphorylated RbC787-816 and the pocket domain is too weak to be detectedin trans by ITC (data not shown); this weak binding(Kd> ~100 μM) is consistent with the high protein concentrations needed to observe the broadening effect in the NMR experiment. Peak broadening is not observed for the 15N-labeled unphosphorylated peptide in the presence of excess Rb pocket, demonstrating that the RbCN-Rb pocket interaction is dependent on phosphorylation of the RbCN peptide (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

Phosphorylation of RbC787-816 promotes intramolecular binding to the Rb pocket domain. (a)1H-15N HSQC spectra of 50 μM 15N-labeled phosphorylated RbC787-816 alone (black) and in the presence of 900 μM unlabeled Rb pocket380-787∆PL (cyan). Broadening of select resonance peaks indicates an in trans association between the phosphorylated RbCN peptide and the pocket domain. (b)The ratio of peak intensity in the presence (I) and absence (I(0)) of pocket domain is plotted for each residue in phosRbC787-816. Ratios are plotted for addition of 300μM (dark blue) and 900 μM (cyan) unlabeled Rb pocket380-787∆PLand for addition of 900 μM pocket in the presence of 900 μM unlabeled E2F2TD(red). Intensity ratios were not quantified for overlapping peaks and prolines, marked with *.(c) HSQC spectra of 60 μM 15N-labeled unphosphorylated RbC787-816 alone (black) and in the presence of 900μM unlabeled Rb pocket380-787∆PL (cyan). The absence of peak broadening indicates a lack of binding between unphosphorylated RbC787-816 and Rb pocket, which demonstrates that binding between RbC787-816 and the pocket is dependent upon phosphorylation. The ratio of peak intensities in the presence and absence of pocket domain are plotted in Supplementary Fig. S3.(d) 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 50 μM15N-labeled phosphorylated RbC787-816 alone (black) and in the presence of 900 μM unlabeled Rb pocket380-787∆PL and 900 μM unlabeled E2F2TD(pink). The signal broadening, plotted in (b),is less extensive than in the absence of E2F2TD, suggesting that binding between E2F2TD and Rb pocket excludes phosphorylated RbC787-816.

NMR peaks in the phosphorylated RbC787-816 spectrum were assigned using standard methods. The peaksthat undergo the most pronounced broadeningcorrespond to clusters of residues surrounding phosphorylatedS788, S795 and S807 (Fig. 2b). The most straightforward interpretation of this result is that residues in these sequences directly contact the pocket domain. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that a subset of these spectral perturbations result from structural changes in RbCNthat occur upon association. Peaks corresponding to residues surrounding S807 are influenced in the pocket titration, even though these residues do not contribute to inhibition of E2F1TD in the ITC assay. The chemical environments of these residues are perhaps influenced by pocket binding in a manner that is independent of the effect of phosphorylated RbC on E2F inhibition. We next tested for whether binding of phosphorylated RbCN and E2FTDto the pocket is mutually exclusive. We titrated a labeled, phosphorylated RbCN sample with unlabeled Rb pocket that is first saturated with one molar equivalent of E2F2TD. In this case, we observe reduced peak broadening effects, demonstrating that E2FTDwhen present in excess prevents phosphorylated RbCNfrom bindingthe pocket (Fig. 2b and 2d).

We examined the structure of the pocket-E2F2TD complex to identify potential binding sites between the pocket and phosphorylated RbCN (Fig. 3a). We found two clusters of conserved sidechains that are capable of coordinating a phosphate. These sidechains make interactions with E2FTD that would likely be disrupted by RbCN binding and are in close proximity to the structured C-terminus of the pocket (I785 in the E2F2TD-pocket structure).10 One site is near K652 and R656. K652 forms a salt bridge with E417 in E2F2. A second potential site is formed by K548, H555, R661, and H733. K548 and H555 hydrogen bond with D410 and D411 in E2F2TD respectively. We used the NMR assay to examine whether mutation of these sites influences the binding of phosRbCN to the pocket domain (Fig. 3b). We added unlabeled wild-type, K652A/R656A, and H555A/H733A pocket to 15N-labelled phosRbC787-816 and compared the line-broadening in the spectra. The K652A/R656A pocket mutant shows reduced broadening consistent with loss of affinity, while the H555A/H733A mutant shows similar behavior as wild-type. These dataindicate that phosRbCN binding requires an interaction with the conserved K652A/R656A pocket.

Fig. 3.

Phosphorylated RbCN binds the pocket domain at a site that overlaps the E2FTD binding site. (a) Putative interactions sites in the pocket domain for phosphorylated RbCN sidechains. The structure of the E2F2TD-pocket complex is shown (PDB code: 1N4M) along with two clusters of residues that could be reached by S795 (K548, H555, R661, and H733) and S788 or S795 (K652 or R656). Binding of RbCN in this region of the pocket would disrupt interactions with the N-terminal portion of E2FTD.(b) Mutation of K652/R656 but not H555/H733 inhibits binding of phosRbCN to the pocket domain. The ratio of peak intensity in the presence (I) and absence (I(0)) of 300 μM wild-type (dark blue), K652A/R656A (green), and H555A/H733A (yellow) pocket domain is plotted for each residue in phosRbC787-816. The K652A/R656A mutant induces relatively less line broadening, suggesting that the association depends on those residues.

Phosphorylation of RbCN Dissociates RbCN from E2F1-DP1CM

It has been observed that that phosphorylation of S788/S795 in the context of the entire RbC (residues 771-928) weakens the RbC affinity for E2F1-DP1CM.14 However, because RbCN was not included in the ternary complex that crystallized, the mechanismhas not been characterized. We examined here whether RbCNbinds directly with E2F1-DP1CM and whether this association is modulated by S788/S795 phosphorylation. We collected 1H-15N HSQC spectra of unphosphorylated 15N-labeled RbC787-816both alone and in the presence of unlabeledE2F1-DP1CM (Fig. 4a). By comparing the spectra, we observe extensive signal broadening indicative of complex formation between unphosphorylated RbCN and E2F1-DP1CM. When we conduct this experiment using phosphorylated15N-labeled RbCN, we see less signal-broadening (Fig. 4b), suggesting that phosphorylation of RbCN destabilizes the direct binding interaction with E2F-DP1CM. Taken together with the NMR data demonstrating an RbCN-pocket interaction (Fig. 2), these results suggest that RbCN phosphorylation has two distinct roles in disrupting the overall Rb-E2F complex (Fig. 4c). First, phosphorylation of RbCN destabilizes the direct association between RbCN and E2F1-DP1CM. Second, phosRbCNbinds the pocket domain to destabilize the E2F1TD interaction.

Fig. 4.

Phosphorylation of RbC787-816 abrogates binding between RbCN and E2F1-DP1CM.(a) 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 60 μM15N-labeled unphosphorylated RbC787-816 alone (black), and in the presence of 300 μM unlabeled E2F1-DP1CM(red). The peak broadening observed in this spectrum indicates binding. (b) HSQC spectra of 100 μM 15N-labeled phosphorylated RbC787-816 alone (black) and in the presence of 300 μM unlabeled E2F1-DP1CM (red). Less peak broadening is observed here than in (a), indicating that phosphorylation of RbC787-816 inhibits the RbC-E2F1-DP1CMcomplex. (c) Summary of interactions identified by NMR: phosphorylated RbC787-816 dissociates from E2F1-DP1CMand associates with Rb pocket in a manner that is inconsistent with E2FTDbinding.

Phosphorylation of RbCNis Additivewith the Effects of RbPL and RbIDL Phosphorylation in Inhibiting E2F1TD-Rb Pocket Binding

With these observed effects ofRbCN phosphorylation, we have now identified three distinct structural mechanisms by which Rb phosphorylation inhibits E2F1TD binding to the pocket domain. Phosphorylation of RbIDL (T356/T373) induces RbN-pocket docking and inhibits Rb-E2F1TD binding approximately 45-fold.25;26 Most of this effect is attributable to T373 phosphorylation alone, which mediates the conformational change,although T356 phosphorylation does enhance the inhibition of Rb-E2F1TD binding.26 Phosphorylation of RbPL at S608 induces association of RbPL and the pocket,which inhibits Rb-E2F1TD binding approximately 10-fold. S612 phosphorylation alone in RbPL reduces E2F1TD binding 3-fold, but has no additive effect when S608 is also phosphorylated.25;26 Finally, we report here that phosphorylation of S788 and S795 in RbCNinduces an association with the pocket domain, which inhibits Rb-E2F1TD binding approximately 7-fold.

We previously found that RbPL and RbIDL phosphorylation together have an additive effect in inhibiting Rb-E2F1TD.25 We next investigated whether RbCN phosphorylation contributes additively to the inhibitory effects of RbPL and RbIDL phosphorylation. We first generated an Rb construct (Rb380-816)that contains both the RbCN(S788/S795) and RbPL(S608/S612) phosphorylation sites but lacks RbN and the RbIDL(T356/T373) phosphorylation sites. E2F1TD binds unphosphorylated Rb380-816/780Awith a Kd of 0.07 ± 0.03 μM, and phosphorylated Rb380-816/780A with a Kd of 3.1 ± 0.5 μM (Fig. 5a and 5b). This 45-fold reduction in E2F1TD binding is nearly the product of the 10-fold and 7-fold effects observed independently,indicating that the RbPL and RbCN mechanisms work together to inhibit the Rb-E2F1TD complex.

Fig. 5.

ITC data demonstrate that Rb-E2F binding inhibition occurs through the additive effects of multiple mechanisms. Dissociation constants were determined from binding isotherms of E2F1TD with (a)unphosphorylated Rb380-816/780A,(b) phosphorylated Rb380-816/780A, (c) unphosphorylated Rb53-800∆NL/∆PL/S780A, and (d) phosphorylated Rb53-800∆NL/∆PL/S780A. As shown in the schematic diagrams, these constructs each contain elements needed for two inhibitory mechanisms. Their phosphorylation results in reduced affinity that is greater than constructs containing single inhibitory mechanisms.

To test whether RbCN and RbIDL phosphorylation similarly add in inhibiting E2FTD binding, we used a construct of Rb thatcontains RbN,RbIDL, the pocket, and RbCN, but lacks the large loops in the pocket and RbN (Rb55-800∆NL/∆ PL/S780A). Weobserve that E2F1TD binds 230-fold more weakly when this Rbconstruct is phosphorylated (Kd = 30 ± 10 μM)compared to when it is unphosphorylated(Kd = 0.13 ± 0.05 μM) (Fig. 5c and 5d). RbCN and RbIDL phosphorylation mechanisms are therefore also additive, as phosphorylation at these sites has a 7-fold and 45fold effect alone respectively. These dataindicate that RbCN phosphorylation functions in a manner that is functionally compatible with the mechanisms induced by phosphorylation of RbIDL and RbPL, lending insight into the way that these three separate structural mechanisms contribute to the inhibition of Rb-E2FTD binding.

Phosphorylation Mechanisms Regulate E2Fs Differently

The E2F family of transcription factors consists of members that both activate transcription (E2Fs 1-3) and repress transcription (E2Fs 4-8). During G0 and early G1, Rb negatively regulates transcription by binding and repressing activating E2Fs 1-3, whereas the Rb paralogs p107 and p130 associate with repressive E2F4 and E2F5.32 E2F1-5 display a large degree of sequence and structural similarity, and crystal structures of E2F1TD and E2F2TD bound to Rb pocket reveal mostly similar binding modes. There are some notable, albeit subtle, differences in binding. For example, E2F2TD makes additional salt bridge and hydrogen bond contacts through D410 and D411, which are not observed in the structure of Rb-E2F1TD.10;11 These differences in binding contacts suggest that E2Fs may be differentially affected by the distinct phosphorylation-induced mechanisms for E2F release.

We compared binding of E2F1TD, E2F2TD and E2F3TD to Rb constructs designed to promote the specific phosphorylation-induced structural mechanisms we have identified for inhibiting E2FTD binding. These ITC data are summarized in Table 2and shown in Supplementary Fig. S4. Previously we found that phosphorylation of RbIDL (T356/T373) inhibits E2F1TD binding to Rb pocket 45-fold.25 When we perform this experiment using the other activating E2Fs, we find that E2F3TD binding is inhibited 25-fold, while E2F2TD binding is inhibited only 2-fold. Phosphorylation of RbPL (S608/S612) and RbCN (S788/S795) raise the Kd for Rb-E2F3TD binding 9-fold and 10-fold respectively. These effects are similar to what is observed for E2F1TD;25 however, we also observe that either of these mechanisms alone produces only a relatively smaller3 to 4fold inhibition of E2F2TD binding. When we test the effect of phosphorylating RbIDL and RbCN together, we observe a larger22-fold reduction in the binding affinity of E2F2TD, suggesting that these mechanisms have a cooperative effect in dissociating E2F2TD from Rb.

These results support several conclusions regarding how phosphorylation modulates differently the interaction between Rb and the activating E2Fs. First, the Rb-E2F2TD interaction is distinct from E2F1TD and E2F3TD in that individual phosphorylation events produce little effect. Second, E2F1TD and E2F2TD have considerably higher affinity for unphosphorylated Rb than E2F3TD. Therefore, like for E2F2TD, multiple phosphorylation events on Rb are required for changing the E2F1TD affinity to the micromolar range. With its weaker initial affinity, E2F3TD only requires any one phosphorylation event for micromolar affinity. Finally, we note that in the context of full-length phosphorylated Rb, it was observed that deletion of RbC has no effect on the inhibition of E2F1TD binding.25 We suggest that the inhibitory effect of RbCN phosphorylation observed here may not be additive with both RbIDL and RbPLphosphorylation together. Another possible explanation is that the association between RbC and the pocket induced by T821/T826 phosphorylation negatively influences the ability of phosphorylated RbCN to bind the pocket and inhibit E2FTD. Further exploration of the interdependence of phosphorylation events and their corresponding structural changes is needed to address these possibilities.

Discussion

Rb inactivation by multisite phosphorylation is required for cell cycle advancement into S phase and is commonly found in tumors. The studies presented here reveal a novel phosphorylation-induced mechanism that utilizes RbC and contributes to inhibition of the Rb-E2F growth-repressive complex. Our datademonstrate that S788/S795 phosphorylation plays a dual role in disrupting both the RbC-E2F1-DP1CM and Rb pocket-E2FTD interfaces. Our NMR data support a model in which phosphorylation of these sites stabilizes binding of RbCN to the pocket domain. The interdomain association is likely mediated by other amino acids surrounding the phosphate moieties and takes place at a site that overlaps with the E2FTD binding site.

Our analysis indicates that RbCN phosphorylation enhances repression of E2FTD binding induced by either RbPLorRbIDL phosphorylation, indicating that these pairwise mechanisms are functionally compatible. The additive inhibitionof these phosphorylation events isconsistent with theirknown and proposed structural effects. The binding site for phosphorylated RbCNin the pocket domain near K652/R656suggest that phosphorylated RbCN, like RbIDL phosphorylation,disrupts interactions between the pocket and the N-terminal section of E2FTD(Fig. 3).26 Alternatively, RbPLphosphorylation targets a separate Rb-E2FTD interface near the C-terminus of E2FTD.26 We propose that the additive effect of RbCN and RbPL phosphorylation in inhibiting Rb-E2FTD binding occurs because these two mechanisms each targets a distinct, stabilizing subsection of the overall Rb-E2FTD interface. We find that S807/S811 phosphorylation does not contribute to inhibition of the Rb-E2FTD interaction either alone or in the presence of S788/S795. Although it remains a formal possibility that these residues contribute in some unique way to the regulation of Rb-E2F, other roles for these phosphoacceptor sites have been suggested,including modulating interactions with other proteins and serving as priming sites for subsequent phosphorylation events.24;29;33

The quantitative binding studies presented here are consistent with cell-based studies, which indicate S788/S795 phosphorylation plays a role in the dissociation of Rb-E2F complexes and E2F transactivation that is additive with other sites. Transcriptional assays using alanine substitutions at S788 and S795 show that these mutations alone are not sufficient to suppress E2F activation in the presence of kinase.30 However, these mutations do greatly enhance the effects of additional phosphoacceptor mutations in suppressing E2F activity in the presence of kinase. A similar study confirms that S795 phosphorylation alone is insufficient to induce E2F activity.34 In cells, S795 phosphorylation is most likely the target of CDK4, and not CDK2.21;35;36 More recent studies have shown that S795 phosphorylation and E2F activation also occur in response to p38 activation.37;38

We tested for the first time here the specific effects of each phosphorylation mechanism on different activating E2F transactivation domains. We found that while discrete phosphorylation at T356/T373, S608/S612, or S788/S795 reduces the affinity of Rb for E2F1TD or E2F3TD nearly 10-fold in each case, the effect of phosphorylating one pair of sites on E2F2TD binding is modest. Phosphorylation of both the RbIDL and RbCN sites together dramatically reduces E2F2TD. While we do not understand the details explaining this synergy and its specificity for E2F2TD, we note that E2F2TD makes specific additional contacts relative to E2F1TD in the region of the pocket domain most affected by the structural changes induced by RbCN and RbIDL phosphorylation.

The observation that E2F1TDandE2F2TD is less responsive to activation by specific phosphorylation events than E2F3TD is noteworthyconsidering activating E2Fs have distinct cellular functions,regulate only partially overlapping sets of genes, and show differences in how they regulate expression in conjunction with other transcription factors and post-translational modifications.32;39;40 We suggest that such differential effects of phosphorylation provide a possible mechanism for tuning different E2F family member activities separately. Further identification of specific Rb phosphorylation events in different cellular contexts remains an important goal for understanding when and how these mechanisms contributeto Rb regulation of E2F activity.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression, Purification and Phosphorylation

Rb and E2F protein constructs were expressed in E. coli as fusion proteins with glutathione-S-transferase (GST). Cells were induced overnight at room temperature with the exception of RbC787-816, which was induced for 2.5 hr at 37°C. Cells were re-suspended in a lysate buffer containing 100mM NaCl, 25mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1mM PMSF and 1mM dithiotheritol, passed twice through a cell homogenizer, and centrifuged at 27,000 × g for 30 minutes. The supernatant fraction of the lysate was loaded to GS4B affinity resin and eluted with 10mM glutathione. Elute was further purified using anion exchange chromatography. The GST tag was cleaved overnight at 4°C with 1% (percentage mass of substrate in the reaction) GST-tagged tobacco etch virus (TEV), and the cleaved protein was passed back over GS4B resin to remove GST. E2F1-DP1CMwas prepared and purified as described previously.14

Purified Rb protein was phosphorylated by concentrating to 4 mg/mL and incubating in a reaction containing 5% CDK2-CyclinA, 10mM ATP, 10mM MgCl2, 100mM NaCl, 25mM TrisHCl pH 8.0, 1mM dithiotheritol at 4°C overnight. Quantitative phosphorylation of RbC787-816 could be achieved but required using5% CDK2-CyclinA and 2% CDK6-CyclinK. Proteins were analyzed for phosphate incorporation using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry as previously described.25A sample mass spectrometry experiment demonstrating quantitative phosphorylation is shown in SupplementaryFig.S2.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

All samples were prepared in a buffer containing 50mM NaPO4, 5mM dithiotheritol and 10% D2O (pH 6.1). 1H-15N HSQC Spectra were recorded at 25°C on a Varian INOVA 600-MHz spectrometer equipped with a HCN 5-mm cryoprobe. HSQC assignments for 15N-labeled phosphorylated RbC787-816 were obtained using 1H-15N sidechain correlations observed in a three-dimensional 1N-15N TOCSY spectrum (120ms mixing time) and a three-dimensional 1N-15N NOESY spectrum (360ms mixing time).41;42 All NMR spectra were processed with NMRpipe and analyzed with NMRViewJ.43;44

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

ITC experiments were conducted with a MicroCal VP-ITC calorimeter. Proteins were dialyzed overnight in a buffer containing 100mM NaCl, 25mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and 1mM dithiotheritol. The data were fit to one-site binding using the Origin software package. Reported errors values reflect the standard deviation of 2-4 separate binding experiments. In all cases the stoichiometry parameter was determined to be around n ~ 1.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig.S1 ITC data corresponding to the measurements summarized in Table 1.

Supplementary Fig.S2 Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry data demonstrating the preparative in vitro kinase reaction yields quantitative phosphorylation on available Cdk phosphoacceptor sites. Rb380-816∆ PL/S780A, which contains four acceptor sites (S788/S795/S807/S811), was phosphorylated as described in Materials and Methods. The spectra for the unphosphorylated (above, blue) and phosphorylated (below, red) proteins are shown. The difference in molecular weight (+320) corresponds to the addition of four phosphates.

Supplementary Fig.S3 Titration of Rb pocket domain into unphosphorylated 15N-labelled RbC787-816 shows little perturbation to the HSQC spectrum, which is consistent with a lack of an association. The ratio of RbC peak intensities in the presence (I) and absence (I(0)) of pocket are plotted for the 19 unassigned, non-overlapping peaks in the spectrum.

Supplementary Fig.S4 ITC data corresponding to the measurements summarized in Table 2.

Highlights.

Phosphorylation of the Rb C-terminal domain (RbC) inhibits binding of the E2F transcription factor transactivation domain.

Phosphorylation in RbC induces a conformational change that blocks access to an E2F binding site.

The RbC mechanism is additive with other phosphorylation induced inhibitory mechanisms.

Rb complexes with different E2F family members are inhibited differently by each mechanism.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Burkhart DL, Sage J. Cellular mechanisms of tumour suppression by the retinoblastoma gene. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:671–82. doi: 10.1038/nrc2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dick FA, Rubin SM. Molecular mechanisms underlying RB protein function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:297–306. doi: 10.1038/nrm3567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchkovich K, Duffy LA, Harlow E. The retinoblastoma protein is phosphorylated during specific phases of the cell cycle. Cell. 1989;58:1097–105. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90508-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen PL, Scully P, Shew JY, Wang JY, Lee WH. Phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma gene product is modulated during the cell cycle and cellular differentiation. Cell. 1989;58:1193–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90517-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeCaprio JA, Ludlow JW, Lynch D, Furukawa Y, Griffin J, Piwnica-Worms H, Huang CM, Livingston DM. The product of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene has properties of a cell cycle regulatory element. Cell. 1989;58:1085–95. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mihara K, Cao XR, Yen A, Chandler S, Driscoll B, Murphree AL, T'Ang A, Fung YK. Cell cycle-dependent regulation of phosphorylation of the human retinoblastoma gene product. Science. 1989;246:1300–3. doi: 10.1126/science.2588006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bagchi S, Weinmann R, Raychaudhuri P. The retinoblastoma protein copurifies with E2F-I, an E1A-regulated inhibitor of the transcription factor E2F. Cell. 1991;65:1063–72. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90558-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bandara LR, La Thangue NB. Adenovirus E1a prevents the retinoblastoma gene product from complexing with a cellular transcription factor. Nature. 1991;351:494–7. doi: 10.1038/351494a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagemeier C, Cook A, Kouzarides T. The retinoblastoma protein binds E2F residues required for activation in vivo and TBP binding in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:4998–5004. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.22.4998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee C, Chang JH, Lee HS, Cho Y. Structural basis for the recognition of the E2F transactivation domain by the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3199–212. doi: 10.1101/gad.1046102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao B, Spencer J, Clements A, Ali-Khan N, Mittnacht S, Broceno C, Burghammer M, Perrakis A, Marmorstein R, Gamblin SJ. Crystal structure of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein bound to E2F and the molecular basis of its regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2363–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0436813100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cecchini MJ, Dick FA. The biochemical basis of CDK phosphorylation-independent regulation of E2F1 by the retinoblastoma protein. Biochem J. 2011;434:297–308. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dick FA, Dyson N. pRB contains an E2F1-specific binding domain that allows E2F1-induced apoptosis to be regulated separately from other E2F activities. Mol Cell. 2003;12:639–49. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00344-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubin SM, Gall AL, Zheng N, Pavletich NP. Structure of the Rb C-terminal domain bound to E2F1-DP1: a mechanism for phosphorylation-induced E2F release. Cell. 2005;123:1093–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helin K, Lees JA, Vidal M, Dyson N, Harlow E, Fattaey A. A cDNA encoding a pRB-binding protein with properties of the transcription factor E2F. Cell. 1992;70:337–50. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90107-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaelin WG, Jr, Krek W, Sellers WR, DeCaprio JA, Ajchenbaum F, Fuchs CS, Chittenden T, Li Y, Farnham PJ, Blanar MA, et al. Expression cloning of a cDNA encoding a retinoblastoma-binding protein with E2F-like properties. Cell. 1992;70:351–64. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90108-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qin XQ, Chittenden T, Livingston DM, Kaelin WG., Jr Identification of a growth suppression domain within the retinoblastoma gene product. Genes Dev. 1992;6:953–64. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lees JA, Buchkovich KJ, Marshak DR, Anderson CW, Harlow E. The retinoblastoma protein is phosphorylated on multiple sites by human cdc2. Embo J. 1991;10:4279–90. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb05006.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin BT, Gruenwald S, Morla AO, Lee WH, Wang JY. Retinoblastoma cancer suppressor gene product is a substrate of the cell cycle regulator cdc2 kinase. EMBO J. 1991;10:857–64. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mittnacht S, Lees JA, Desai D, Harlow E, Morgan DO, Weinberg RA. Distinct sub-populations of the retinoblastoma protein show a distinct pattern of phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1994;13:118–27. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06241.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zarkowska T, Mittnacht S. Differential phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein by G1/S cyclin-dependent kinases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12738–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chellappan SP, Hiebert S, Mudryj M, Horowitz JM, Nevins JR. The E2F transcription factor is a cellular target for the RB protein. Cell. 1991;65:1053–61. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90557-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamel PA, Gill RM, Phillips RA, Gallie BL. Regions controlling hyperphosphorylation and conformation of the retinoblastoma gene product are independent of domains required for transcriptional repression. Oncogene. 1992;7:693–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubin SM. Deciphering the retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation code. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38:12–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burke JR, Deshong AJ, Pelton JG, Rubin SM. Phosphorylation-induced conformational changes in the retinoblastoma protein inhibit E2F transactivation domain binding. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16286–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.108167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burke JR, Hura GL, Rubin SM. Structures of inactive retinoblastoma protein reveal multiple mechanisms for cell cycle control. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1156–66. doi: 10.1101/gad.189837.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamber EP, Beuron F, Morris EP, Svergun DI, Mittnacht S. Structural insights into the mechanism of phosphoregulation of the retinoblastoma protein. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harbour JW, Luo RX, Dei Santi A, Postigo AA, Dean DC. Cdk phosphorylation triggers sequential intramolecular interactions that progressively block Rb functions as cells move through G1. Cell. 1999;98:859–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knudsen ES, Wang JY. Differential regulation of retinoblastoma protein function by specific Cdk phosphorylation sites. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8313–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown VD, Phillips RA, Gallie BL. Cumulative effect of phosphorylation of pRB on regulation of E2F activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3246–56. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knudsen ES, Wang JY. Dual mechanisms for the inhibition of E2F binding to RB by cyclin-dependent kinase-mediated RB phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5771–83. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.5771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trimarchi JM, Lees JA. Sibling rivalry in the E2F family. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:11–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ren S, Rollins BJ. Cyclin C/cdk3 promotes Rb-dependent G0 exit. Cell. 2004;117:239–51. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00300-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorges LL, Lents NH, Baldassare JJ. The extreme COOH terminus of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein pRb is required for phosphorylation on Thr-373 and activation of E2F. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C1151–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00300.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Connell-Crowley L, Harper JW, Goodrich DW. Cyclin D1/Cdk4 regulates retinoblastoma protein-mediated cell cycle arrest by site-specific phosphorylation. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:287–301. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grafstrom RH, Pan W, Hoess RH. Defining the substrate specificity of cdk4 kinase-cyclin D1 complex. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:193–8. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garnovskaya MN, Mukhin YV, Vlasova TM, Grewal JS, Ullian ME, Tholanikunnel BG, Raymond JR. Mitogen-induced rapid phosphorylation of serine 795 of the retinoblastoma gene product in vascular smooth muscle cells involves ERK activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24899–905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang S, Nath N, Minden A, Chellappan S. Regulation of Rb and E2F by signal transduction cascades: divergent effects of JNK1 and p38 kinases. EMBO J. 1999;18:1559–70. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giangrande PH, Hallstrom TC, Tunyaplin C, Calame K, Nevins JR. Identification of E-box factor TFE3 as a functional partner for the E2F3 transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3707–20. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.11.3707-3720.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlisio S, Halperin T, Vidal M, Nevins JR. Interaction of YY1 with E2Fs, mediated by RYBP, provides a mechanism for specificity of E2F function. EMBO J. 2002;21:5775–86. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mori S, Abeygunawardana C, Johnson MO, van Zijl PC. Improved sensitivity of HSQC spectra of exchanging protons at short interscan delays using a new fast HSQC (FHSQC) detection scheme that avoids water saturation. J Magn Reson B. 1995;108:94–8. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1995.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norwood TJ, Boyd J, Heritage JE, Soffe N, Campbell ID. Comparison of Techniques for H-1-Detected Heteronuclear H-1-N-15 Spectroscopy. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1990;87:488–501. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson BA, Blevins RA. NMR View: A computer program for the visualization and analysis of NMR data. J Biomol NMR. 1994;4:603–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00404272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig.S1 ITC data corresponding to the measurements summarized in Table 1.

Supplementary Fig.S2 Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry data demonstrating the preparative in vitro kinase reaction yields quantitative phosphorylation on available Cdk phosphoacceptor sites. Rb380-816∆ PL/S780A, which contains four acceptor sites (S788/S795/S807/S811), was phosphorylated as described in Materials and Methods. The spectra for the unphosphorylated (above, blue) and phosphorylated (below, red) proteins are shown. The difference in molecular weight (+320) corresponds to the addition of four phosphates.

Supplementary Fig.S3 Titration of Rb pocket domain into unphosphorylated 15N-labelled RbC787-816 shows little perturbation to the HSQC spectrum, which is consistent with a lack of an association. The ratio of RbC peak intensities in the presence (I) and absence (I(0)) of pocket are plotted for the 19 unassigned, non-overlapping peaks in the spectrum.

Supplementary Fig.S4 ITC data corresponding to the measurements summarized in Table 2.