Abstract

The current clinical approach for treating autoimmune diseases is to broadly blunt immune responses as a means of preventing autoimmune pathology. Among the major side effects of this strategy are depressed beneficial immunity and increased rates of infections and tumors. Using the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis model for human multiple sclerosis, we report a novel alternative approach for purging autoreactive T cells that spares beneficial immunity. The moderate and temporally limited use of etoposide, a topoisomerase inhibitor, to eliminate encephalitogenic T cells significantly reduces the onset and severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, dampens cytokine production and overall pathology, while dramatically limiting the off-target effects on naive and memory adaptive immunity. Etoposide-treated mice show no or significantly ameliorated pathology with reduced antigenic spread, yet have normal T cell and T-dependent B cell responses to de novo antigenic challenges as well as unimpaired memory T cell responses to viral rechallenge. Thus, etoposide therapy can selectively ablate effector T cells and limit pathology in an animal model of autoimmunity while sparing protective immune responses. This strategy could lead to novel approaches for the treatment of autoimmune diseases with both enhanced efficacy and decreased treatment-associated morbidities.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a neuroinflammatory autoimmune disease in which T cell driven inflammation leads to demyelination and damage of axons in the CNS. MS manifests itself through a diverse array of clinical pathologies ranging from cognitive and ocular impairments to full paralysis (1, 2). Magnetic resonance imaging and patient necropsy studies reveal that actively demyelinating lesions are typified by infiltration of CD4+ T cells and macrophages in the white matter of the CNS (3, 4). To date, there is no known cure for MS, although there are treatments available that can ameliorate symptoms of the disease. However, they have limited efficacy, significant adverse effects, or are broadly immunosuppressive. The standard first-line treatment strategy for MS is the use of immunomodulating drugs: IFN-β, glatiramer acetate, and/or steroids (5). Although the exact mechanism of action for these drugs is poorly understood, it is known that they all suppress or redirect immune activation. The next class of MS therapeutics is lymphocyte trafficking inhibitors, including natalizumab (6) and fingolimod (sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor analog) (7, 8). These treatments inhibit lymphocyte migration, not only to the CNS, but also to sites of infection (9). As a final measure, the chemotherapeutic drug mitoxantrone can be given in particularly severe and progressive cases, although its use is limited by cardiac toxicity (10, 11). Thus, none of the current therapeutic strategies designed to prevent destruction of the CNS specifically target the encephalitogenic response. Reliance on agents that have a nonspecific suppressive effect on the immune response leads to increases in secondary infections (12) and an increase in the outgrowth of tumors (13, 14). Moreover, the current therapeutic approaches do not stem the eventual progress of MS.

It is well established that damage to the CNS is mediated by a relatively small number of self-reactive T cells (15). We reasoned that instead of suppressing the immune system as a whole, a more logical and appropriate strategy to treat MS would focus on the selective targeting of these rogue encephalitogenic T cells. Therefore, we and others (16, 17) propose that selectively eliminating activated encephalitogenic T cells will effectively ameliorate the progression of MS while markedly reducing the off-target effects of therapy. To test the viability of this approach, we used a mouse model of MS, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). As reviewed by Gold et al. (18), EAE is induced by immunizing mice with neural Ags leading to CNS inflammation and damage, similar to what is seen in MS patients. EAE affords us a model that generates a tractable population of pathogenic T cells with defined epitopes and immunologic functions (19). In addition, using variations of EAE, we can test our hypothesis under varying pathologic conditions including the generation of new encephalitogenic T cells to spread epitopes in the relapsing-remitting model of EAE.

As a means to selectively eliminate encephalitogenic T cells, we used the cytotoxic drug etoposide. Etoposide is a topoisomerase inhibitor (20, 21) that is used clinically to treat a variety of cancers and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) (22), a primary immune deficiency where aberrant T cell responses lead to immune-mediated pathology. In parallel studies by our group (see companion article, Ref. 23), we demonstrate that etoposide treatment in a mouse model of HLH decreases immune-mediated pathology by selectively deleting pathogenic activated antiviral T cells, demonstrating that etoposide is a useful tool to delete activated T cells that induce immune mediated damage. In addition, this study provides a detailed mechanistic understanding of etoposide’s action on activated T cells in vivo.

In this study, we report that using etoposide as an agent to clear encephalitogenic T cells is effective in the treatment of the autoimmune disease EAE. Etoposide treatment reduced clinical symptoms as well as the number and function of encephalitogenic T cells. Notably, etoposide treatment acts primarily against autoimmune effector T cells and not naive or memory T cells, thereby controlling EAE while maintaining beneficial immune responses to new and prior antigenic challenges.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6J and SJL/J mice were purchased from Jackson laboratories and Xiap−/− were bread in house (24). All mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in an American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care–approved barrier facility at Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation. All experiments were performed with prior Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval, and every attempt was made to reduce the numbers of animals used. Animals were under constant monitoring and care of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center veterinary staff.

EAE induction and treatment

Ten-week-old female C57BL/6 (B6) or SJL mice were immunized s.c. with 100 μg myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)35–55 or proteolipid protein (PLP)139–152 emulsified in 5 mg/ml CFA (Hooke Laboratories. Lawrence, MA). On days 0 and 2, animals received i.p. injections of 250 ng pertussis toxin (Hooke Laboratories, Lawrence, MA). Disease severity was assessed every day beginning on day 10 and assigned a value using the following scale: 1, tail flaccidity; 2, hind-limb weakness; 3, hind-limb paralysis; 4, hind- and fore-limb paralysis; and 5, moribund. Immunization and pertussis toxin injections were formulated to maximize the disease severity to be less than or equal to three per the manufacturer’s specifications (Hooke Laboratories) and recommendations of our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Etoposide was administered i.p. at 50 mg/kg twice, 4 d apart (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (25).

Histology

Mice were perfused with PBS, followed by 10% formalin through the left ventricle. Fixed spinal cords were embedded in paraffin and sectioned into 6-μm slices. Sections were either stained with Luxol fast blue (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) and counterstained with H&E or labeled with FluoroMyelin green and DAPI (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). All sections were viewed on a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope at a ×10 objective, and images were processed in ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Isolation of CNS mononuclear cells

Mice were perfused with PBS through the left ventricle prior to removing the brain and spinal cord tissue was dissociated in a Dounce homogenizer. Cells were suspended in a 30% Percoll gradient (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, U.K.) that was overlaid on a 70% Percoll gradient and spun at 500 × g for 30 min at 18°C. Lymphocytes were removed from the interface between Percoll gradients and stained by flow cytometry.

MHC tetramer staining and flow cytometry

Spleens from individual mice were harvested and crushed through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) to generate a single-cell suspension. A total of 2 × 106 cells were stained with different combinations of the following cell surface Abs anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD44, anti–L-selectin, anti-CD16/32, anti-CD25, anti-CD11c, anti-CD11b, anti-NK1.1, anti-CD19, anti-F4/80, anti-Foxp3, anti-Bim, anti-XIAP, and anti–Bcl-2 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA; eBioscience, San Diego, CA; Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA; or Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA). Ex vivo cytokine production was assessed by restimulation with 5 μg peptide, MOG35–55, PLP178–191, PLP139–152, myelin basic protein84–104, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) glycoprotein (GP)33–41 or LCMV GP61–80 (Synthetic Biomolecules, San Diego, CA) in the presence of GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences). Cells were permeabilized with a Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences) and stained with anti–IFN-γ, anti–IL-17a, or anti–TNF-α (BioLegend). The MOG35–55 I-Ab and LCMV GP61–80 I-Ab tetramers were provided by the National Institutes of Health tetramer core. The LCMV GP33–41 Kb tetramer was made in house as described previously (25). Where noted, CD4+ T cells were isolated from the spleen and inguinal lymph nodes and purified by negative selection using CD4+ T cells isolation kit II (Miltenyi Biotec) prior to staining. Flow cytometry data were acquired on an LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) and were analyzed using FlowJo software version 7.6.5 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Proliferation assay

A total of 1 × 105 total splenocytes were cultured in complete DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS, 1 μM HEPES, 1000 U/ml penicillin, and 1000 μg/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies, San Diego, CA) at 37°C with indicated Ag, peptides at 5 μg/ml, and Con A at 2 μg/ml. After 48 h in culture, 1 μCi [3H]thymidine was added to each culture and harvested 18 h later. Assays were read on one of two Top count NTX beta counter (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

LCMV infections

The Armstrong-3 strain of LCMV, a gift from R. Ahmed (Emory University, Atlanta, GA), was grown in BHK-21 cells; the number of PFUs was assayed on Vero cells as described previously (27). Mice were infected i.p. with 2 × 105 PFU LCMV (LCMV Armstrong) for primary infection and postetoposide treatment. Mice were rechallenged i.v. with 2 × 106 PFU clone 13 LCMV to assess memory responses.

TNP-OVA Ab response

Protocol is derived from and detailed by Strait et al. (28). In short, mice were i.p. immunized with 200 μl conjugated trinitrophenyl-OVA (1.25 and 10 mg/ml). Serum was collected for Ab titers and determined by ELISA. Serial dilutions of serum were detected by anti-mouse IgG and IgM (BD Biosciences) bound to plate-bound TNP-OVA. TNP and OVA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Etoposide-mediated apoptosis

Spleens and inguinal lymph nodes were harvested from mice 45 d post-LCMV infection and 12 d post-EAE induction. CD4+ T cells were purified by negative selection using CD4+ T cells isolation kit II (Miltenyi Biotec) and cultured in complete DMEM supplemented with IL-7 (5 ng/ml) and IL-2 (50 ng/ml) (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ). Cells were cultured for 16 h with etoposide, Q-VD-OPH at 20 mg/ml (MP Biomedical, Solon, OH), and necrostatin at 30 μM (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY) prior to staining with tetramers (MOG35–55 I-Ab and LCMV GP61–80 I-Ab) Abs (anti-CD4, anti-CD16/32, and anti-CD44) and viability dye efluor 506 (eBioscience).

Statistics

Where appropriate, results are given as the mean ± SE with statistical significance determined by two-tail t test, using either paired or unpaired (assuming equal variance) according to the data characteristics. Survival curves were assessed by Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon test for differences among groups. Significance was defined as p < 0.5. Statistical analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism 5.04 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA)

Study approval

All animal studies were approved by the Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation institutional animal care and use committee.

Results

Our basic premise is that activated autoreactive T cells are more susceptible to directed ablation than naive or memory T cells in vivo. Thus, to test our ability to target autoreactive T cells, we needed a well-established disease model with a distinct pathology and a defined autoantigen eliciting a tractable population of encephalitogenic T cells; therefore, we chose the MOG model in B6 mice (29). The MOG model gave us a population of tractable encephalitogenic T cells that 1) can be enumerated by tetramer staining, 2) have well-defined functional cytokine profiles, and 3) have a defined spread epitope. As a means to induce clearance of autoreactive cells, we chose etoposide because it targets rapidly dividing cells (21), such as activated effector T cells.

Given the known clinical kinetics of etoposide in the treatment of HLH and its mouse model, along with our knowledge of the kinetics of EAE pathology, we found that two treatments (at 50 mg/kg) 4 d apart yielded optimal effects. Treatments starting on day 5 postinduction of EAE followed 4 d later on day 9 yielded the greatest amelioration of symptoms; however, etoposide is effective at other time points, both earlier and later (Supplemental Fig. 1).

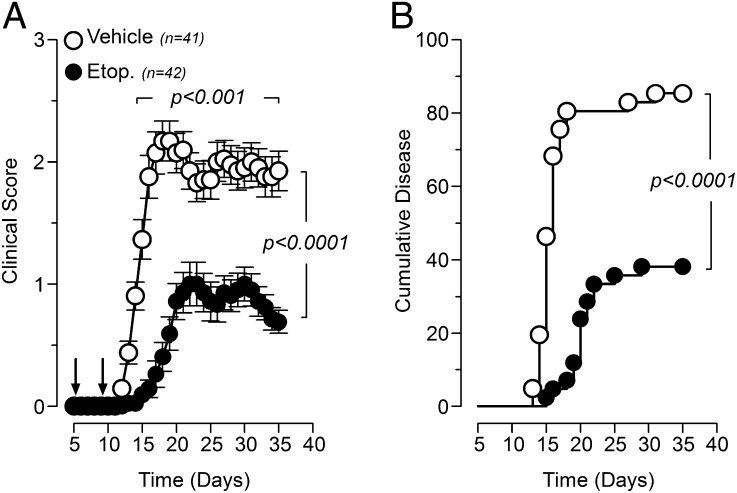

Etoposide treatment significantly reduces the onset of EAE pathology

Mice treated with etoposide, on day 5 and 9 postdisease induction, showed a significantly delayed onset of disease with decreased mean clinical disease scores when compared with vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 1A). Importantly, treatment with etoposide was able to completely prevent EAE in >60% of treated mice and prolong the mean time to disease in the rest, 20.4 d for treated mice versus 16.1 d for vehicle (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Prophylactic etoposide treatment of EAE reduces the severity and incidence of disease. MOG35–55-induced EAE mice were treated with either etoposide (50 mg/kg) or vehicle control 5 and 9 d after induction of EAE. (A) Clinical scores for etoposide and vehicle control mice. (B) Cumulative incidence for disease presentation in etoposide and vehicle-treated mice. Results are shown as cumulative data from five independent experiments.

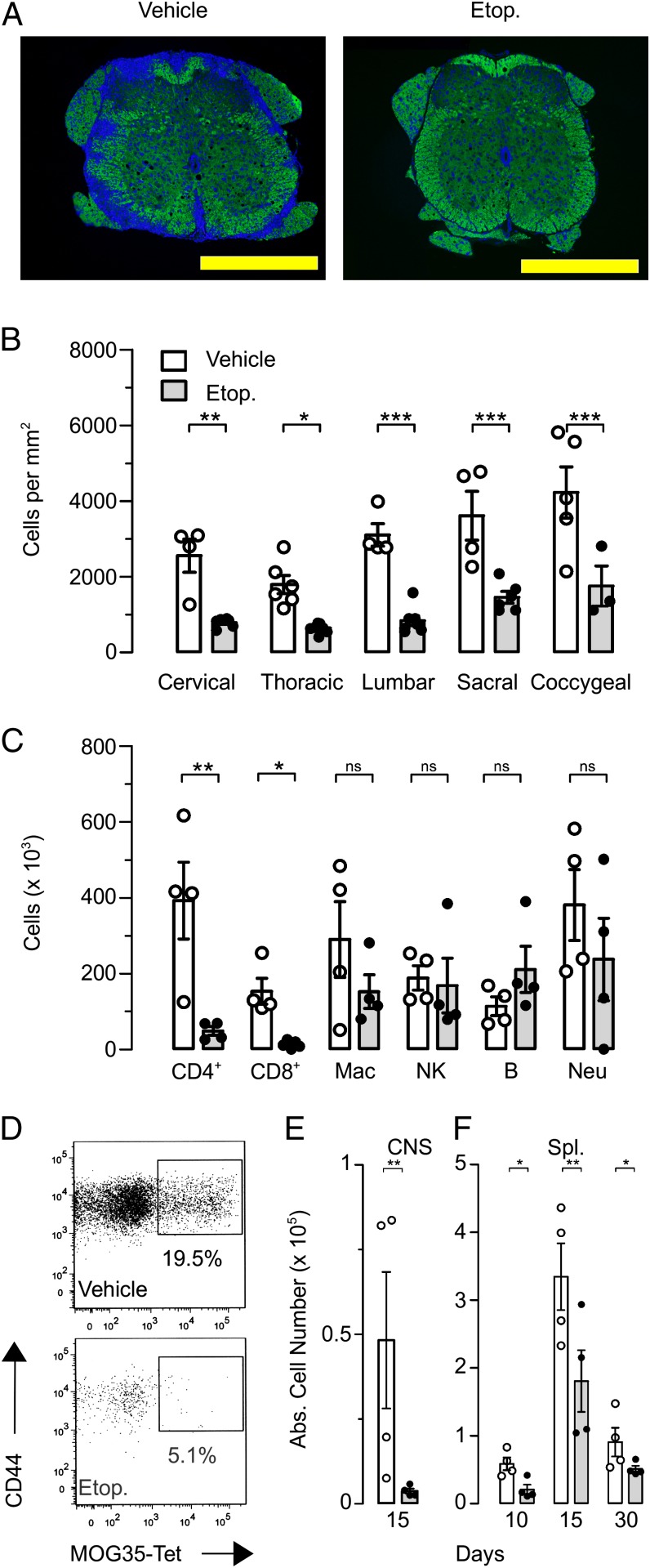

The immune-mediated destruction of oligodendrocytes in the CNS is a hallmark of MS/EAE (30). We investigated the ability of etoposide treatment to limit the immune-mediated damage by assessing the demyelination of the white matter in the CNS. Using quantitative histological analysis for myelin (Luxol fast blue and FluoroMyelin green), we found that control vehicle–treated mice showed severe demyelination in all anatomical regions, cervical to coccygeal. Strikingly, etoposide-treated mice showed little to no demyelination, having well-defined borders between white matter and gray matter as seen in healthy mice (Fig. 2A). Cellular infiltration into the spinal cord was determined by enumerating DAPI staining for nucleated cells in the white matter of the spinal cord. Here again, the numbers of infiltrating cells residing in the white matter of etoposide-treated mice was up to 5-fold less than in the CNS infiltrates in vehicle-treated mice in all anatomical regions studied (Fig. 2B). This is consistent with the lack of demyelination that we observed in etoposide-treated mice where fewer infiltrating cells can cause less damage. To gain a further understanding of cellular infiltrates into the CNS, we homogenized brains and spinal cords from mice 15 d after disease induction to analyze infiltrating leukocyte populations by flow cytometry (Fig. 2C). The greatest differences in cellular populations after etoposide treatment were seen in T cells with a full log decrease in infiltrating CD4+ T cells after treatment. Although etoposide treatment significantly decreased the total number of T cells in the CNS, we wanted to assess the number of MOG-specific CD4+ T cells. To test this, we used a MOG35–55 I-Ab MHC class II tetramer, which allowed us to track Ag-specific CD4+ T cells regardless of their functional state. Etoposide treatment significantly decreased both the percentage (Fig. 2D) and the total number (Fig. 2E) of MOG-specific CD4+ T cells in the CNS as well as in the spleen (Fig. 2F). These data demonstrate that etoposide treatment is able to prevent CNS damage by systemically limiting the number of encephalitogenic T cells in EAE.

FIGURE 2.

Etoposide treatment decreases damage to neurologic tissue. Thirty days after induction of EAE, mice were sacrificed, and neural tissue was assessed for damage. (A) Paraffin-embedded spinal cord sections were stained with FluoroMyelin green and DAPI to assess demyelination and cellular infiltration into the spinal cord. (B) Enumeration of DAPI-positive events for cell infiltration into specific regions of the spinal cord. Images viewed at ×10 objective; yellow bar, 500 μm. (C) Fifteen days after induction of EAE, brain and spinal cord homogenates were assessed for differential leukocyte populations by flow cytometry. (D) Representative flow plot of CNS cells stained with the MOG35–55 I-Ab MHC class 2 tetramer, gated on CD4+CD16/32− population of CNS-infiltrating leukocytes. (E) With cumulative data at day 15. (F) Splenocytes stained with the MOG35–55 I-Ab MHC class 2 tetramer at days 10, 15, and 30 postdisease induction. Data are cumulative of three independent experiments; n = 8 in each group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttests.

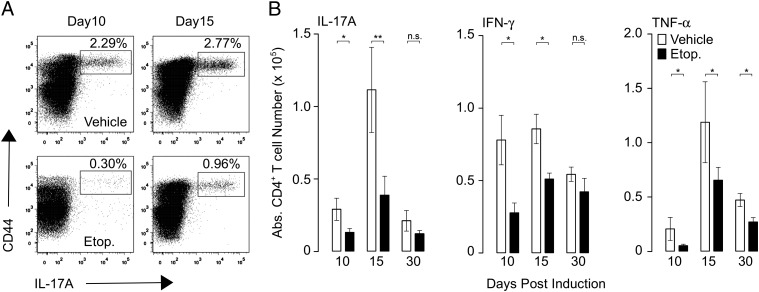

Etoposide treatment eliminates encephalitogenic T cells

Treatment with etoposide significantly mitigated symptoms of EAE. We postulated that etoposide worked by killing encephalitogenic effector T cells that would normally mediate damage. To test this, we evaluated the effects of etoposide treatment on numbers and function of MOG35–55-specific CD4+ T cells. First, we enumerated the total number of MOG35–55-specific CD4+ T cells by tetramer staining, and second, we analyzed the ex vivo cytokine production of MOG35–55-specific CD4+ T cells throughout the course of EAE (31, 32). Etoposide treatment resulted in a significant decrease in the number of cytokine-producing MOG35–55-specific CD4+ splenic T cells throughout the course of the experiment (Fig. 2E, 2F). Similar to the results we observed with tetramer staining, etoposide decreased the frequency of IL-17A, IFN-γ, and TNF-producing MOG35–55-specific CD4+ T cells throughout the course of disease, immediately following treatment (day 10) and at the peak of disease (day 15). As disease plateaued at day 30 and inflammation subsided, a difference was noticeable only in TNF levels (Fig. 3B–D). Taken together, these results demonstrate that etoposide treatment is able to alleviate the symptoms of EAE by eliminating encephalitogenic CD4+ T cells that would otherwise induce pathology.

FIGURE 3.

Etoposide treatment decreases the number of MOG35–55-reactive CD4+ T cells. EAE was induced in B6 mice and treated with etoposide or vehicle 5 and 9 d later. On days 10, 15, and 30, total splenocytes were assayed for MOG35–55 reactivity by ex vivo peptide restimulation. (A) Representative flow plot of IL-17a production by CD4+ T cells restimulated ex vivo with MOG35–55 peptide. (B) Cumulative data for IL-17a production, IFN-γ production, and TNF-α production from three to five independent experiments; n = 10/group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; two-tailed t test.

Etoposide treatment does not cause nonspecific lymphopenia

Etoposide is regularly used as part of a high-dose multidrug mixture used to treat leukemia. A common side effect of this clinical mixture is marrow suppression (33). However, when etoposide is used alone to treat EAE, we found no cytopenias following treatment. The total number of splenocytes was not significantly reduced after treatment (Supplemental Fig. 2). Moreover, when leukocyte subsets were delineated, no difference was seen in the absolute number of splenic T cells (either CD4+or CD8+), regulatory T cells, B cells, or NK cells after etoposide treatment. However, a transient decrease in the total number of APCs, both dendritic cells and macrophages, was observed. These differences recovered within 5 d, indicating that there is no long-term change in the output of hematopoietic cells or Ag presentation (data not shown).

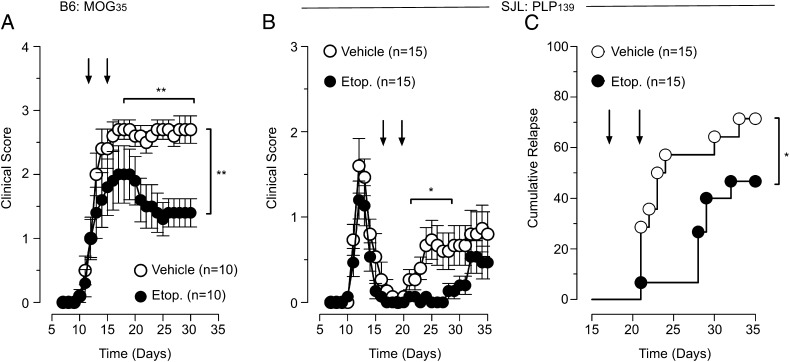

Etoposide treatment decreases pathology in established disease

Having demonstrated the efficacy of prophylactic treatment, we next investigated the effectiveness of etoposide therapy on established disease. Here again, B6 mice were immunized with MOG35–55 peptide to induce disease, and once symptoms were evident, with a mean clinical score of 1, we began etoposide therapy. When etoposide was administered at days 12 and 16 during an established course of disease, etoposide significantly decreased disease severity compared with vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 4A). This demonstrates that etoposide treatment can effectively diminish the severity of an established course of EAE.

FIGURE 4.

Etoposide treatment of EAE reduces disease severity and incidence of relapse. (A) EAE induced in B6 mice was treated with etoposide or vehicle after the presentation of clinical symptoms at days 12 and 16. Clinical scores are depicted for etoposide and vehicle mice. Cumulative data of two independent experiments; n = 10 in each group; two-way ANOVA. EAE was induced in SJL mice. After remittance of the primary course of disease, mice were randomized and treated with etoposide or vehicle at days 17 and 21. (B) Clinical scores are depicted for etoposide and vehicle-treated mice along with (C) the cumulative rate of relapse, n = 15/group, depicted for etoposide and vehicle-treated mice, Kaplan–Meier with Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon test. Fifteen mice per group, 4 (26.7%) mice from vehicle did not relapse and 8 (53.3%) mice from etoposide-treated mice did not relapse.

Etoposide treatment decreases the rate of disease relapse

The most common presentation of MS is the relapsing-remitting form (7), which is well modeled using SJL mice immunized with the PLP139–151 peptide (34). Thus, to access the impact of our treatment design on disease relapse, we induced EAE and allowed the mice to develop a full primary course of disease prior to treatment. Once all mice were in remission and had a disease score of 0, we randomized them into two groups, etoposide or vehicle, and began treatment, days 17 and 21, after initial induction. Mice were then monitored for disease relapse. Etoposide treatment decreased the percentage of mice that relapsed, 46 versus 73% of vehicle mice (Fig. 4C). In addition, in the mice that did relapse, etoposide treatment delayed the mean time to relapse, 27 versus 21 d for vehicle controls. Moreover, the mice that did relapse showed less severe disease compared with vehicle-treated mice. These data demonstrate that etoposide treatment can effectively reduce the rate and severity of relapse.

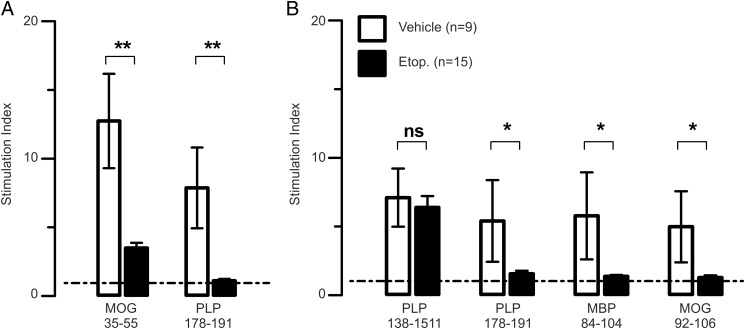

Etoposide treatment decreases the breadth of epitope spread

In both the acute-progressive and the relapsing-remitting forms of MS/EAE, a hallmark of disease progression is epitope spread (35, 36). To determine whether etoposide treatment was preventing disease relapse by effecting epitope spread, we assessed the effect of etoposide treatment on the development of epitope spread in both the B6 and SJL models. As seen in Fig. 5A, etoposide treatment decreased the recall response to the PLP178–191 spread epitope as well as the recall response to the immunizing epitope MOG35–55 in the B6 mouse. In contrast to the B6 mouse, SJL mice have more defined EAE spread epitopes, including both intra- and intermolecular spread epitopes. Etoposide treatment during disease remission had no effect on the immunizing PLP139–151 epitope, likely because an initial course of disease already has taken place prior to treatment. However, etoposide treatment during remission prevented the activation of novel neural Ag-specific T cells, including the PLP178–191 intramolecular spread epitope and both the MOG92–106 and myelin basic protein84–104 intermolecular spread epitopes. The decreased relapse seen in Fig. 4B correlated with markedly reduced spread to both intra- and intermolecular epitopes (Fig. 5B). Taken together, these data suggest that etoposide therapy act to reduce epitope spread, providing a molecular basis for the observed decreases in clinical pathology.

FIGURE 5.

Etoposide treatment prevents epitope spread. (A) Mice were pretreated with etoposide or vehicle at days 5 and 9 after the induction of EAE in B6 mice. Splenocytes were harvested at day 30. Ag-specific proliferation was determined by in vitro incorporation of [3H]thymidine. (B) EAE was induced in SJL mice. After remittance of the primary disease course, mice were treated with etoposide or vehicle at days 17 and 21. Splenocytes were harvested on day 35. Ag-specific proliferation was determined by in vitro incorporation of [3H]thymidine. Cumulative of three independent experiments, n = 15/group (MOG) and n = 9 or 15/group (PLP). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; two-way t test. Dashed line denotes minimum level of significance for stimulation index (≥95% confidence interval) mean background 3H incorporation level of 1011 cpm, with a mean Con A–stimulated foreground of 7995 cpm.

Etoposide does not inhibit naive T cell responses to viral infections

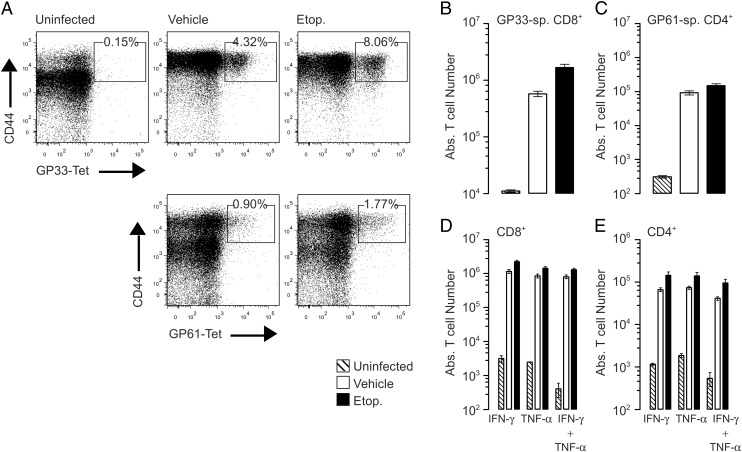

Having demonstrated that etoposide had no major effects on splenic cellularity (Supplemental Fig. 2), we wanted to further test the specificity of etoposide treatment by investigating the effects of etoposide treatment of naive T cell function. To investigate this, B6 mice were pretreated with etoposide 10 and 6 d prior to infection with LCMV, and their primary responses were compared with vehicle-treated controls. On day 10 postinfection, the T cell response to LCMV was analyzed by enumerating the LCMV-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses using LCMV GP33–41 Kb MHC class I tetramer and LCMV GP61-80 I-Ab MHC class II tetramer, respectively (Fig. 6A–C). Mice pretreated with etoposide generated an equally robust antiviral CD4+ and CD8+ T cell response, with no significant difference compared with vehicle-treated mice. To confirm that etoposide pretreatment did not inhibit functional antiviral responses of naive T cells, we assessed their cytokine production by ex vivo peptide restimulation (Fig. 6D, 6E). Both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells from etoposide-pretreated mice produced a robust response, including the antiviral cytokines IFN-γ and TNF. Etoposide treatment did not reduce the total number of cytokine-producing T cells when compared with vehicle mice. Importantly, the LCMV-specific T cells maintained their polyfunctionality, which has been shown to be vital in maintaining viral immunity (37, 38). As a final test of functionality, LCMV viral load was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR for LCMV nucleoprotein. No differences were observed in viral RNA levels between etoposide and vehicle-treated mice (data not shown). Clearance of LCMV confirms that naive T cells remain functional after treatment with etoposide.

FIGURE 6.

Generation of a naive immune response after treatment with etoposide. B6 mice were pretreated with etoposide (50 mg/kg) 14 and 10 d prior to infection with LCMV Armstrong. Ten days post infection spleens were harvested to assess T cell responses. Total number of LCMV-specific T cells was assessed by tetramer staining, GP33–41-specific CD8+ T cells, gated on a CD8+CD16/32− population (A), and GP61–80-specific CD4+ T cells, gated on a CD4+CD16/32− population (B). Total splenocytes were restimulated ex vivo with viral peptide GP33–41 (C) or GP61–80 (D, E) to assess cytokine production, three independent experiments, n = 8/group. No statistical difference between vehicle and etoposide-treated groups was observed, two-tailed t test, and both groups were highly significant compared with uninfected controls, two-way ANOVA, p < 0.001.

Pretreatment with etoposide does not inhibit T cell–dependent B cell responses

In addition to anti-viral responses, CD4+ T cells are vital for driving B cell activation and Ig class switching. To further investigate the effects of etoposide on naive immune responses we immunized mice with the hapten-carrier TNP-OVA to investigate both helper CD4+ T cell and B cell responses. Mice were pretreated with etoposide, as above, and then immunized with TNP-OVA in alum, followed by a TNP-OVA boost on day twelve. Serum was serially collected to assess Ab production against the immunizing Ags. Etoposide pretreatment did not inhibit the generation of either anti-TNP IgG or IgM (Supplemental Fig. 3). At each time point, both etoposide- and vehicle-pretreated mice generated comparable amounts of anti-TNP Abs. These data confirm that etoposide treatment does not impair the activation of naive CD4+ T cells or B cell responses to neoantigens.

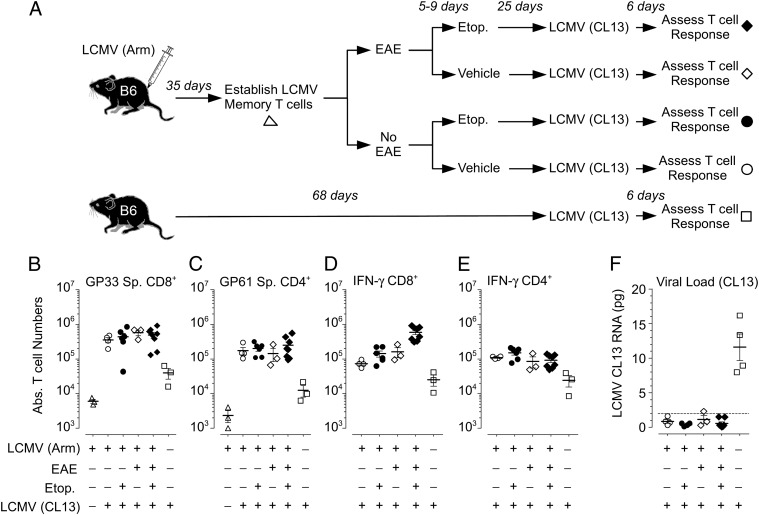

Etoposide does not alter protective T cell memory

The moderate use of etoposide, to eliminate encephalitogenic T cells, results in a significant reduction of EAE severity and overall pathology, without impairing naive T and B cell responses. Thus, it became critical to assess whether etoposide treatment affected protective T cell memory. To this end, we set up the model depicted in Fig. 7A. B6 mice were infected with the Armstrong strain of LCMV and allowed to recover and develop long-term antiviral memory T cells, both CD8+ and CD4+ T cell populations that can be tracked by tetramer staining (26). Next, we randomized the mice and induced EAE in half of them, whereas the remainder were left uninduced, and then, both cohorts were randomized into etoposide or vehicle treatment groups; this approach allowed us to track and target encephalitogenic effector cells in mice with pre-existing antiviral memory. To assess the persistence of functional anti-LCMV memory T cells, the mice, including an age-matched naive cohort, were then challenged with the clone 13 strain of LCMV. This will allow us to confirm functional memory because only mice with an established memory population to LCMV can rapidly clear a clone 13 infection, in the absence of memory; clone 13 induces long-term persistent infection and clonal exhaustion of LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells (37, 39).

FIGURE 7.

Treatment of EAE with etoposide does not inhibit memory responses to viral rechallenge. (A) Six-week-old B6 mice were infected with LCMV Armstrong. At day 35, EAE was induced and treated with etoposide or vehicle control 5 and 9 d later. Mice were sacrificed 5 d after rechallenged with LCMV clone 13 at day 56. Splenocytes were analyzed for total number of LCMV specific T cells using tetramers. GP33–41-specific CD8+ T cells (B) and GP61–80-specific CD4+ T cells (C). Total splenocytes were restimulated ex vivo with LCMV peptide GP33–41 (D) or GP61–80 (E) to assess IFN-γ secretion. (F) Total RNA was extracted and reversed transcribed from liver biopsies. Quantitative PCR for LCMV viral load was assessed from copy numbers of LCMV nuclear protein normalized to S14 (n = 6–10/group). Dashed line indicates minimum level of detection. No statistical difference between vehicle and etoposide-treated groups was observed, two-tailed t test, and all four groups were highly significant compared with age-matched, naive controls infected with clone 13, two-way ANOVA, p < 0.001.

Using this system, we found that the memory T cell responses to viral rechallenge were unaffected by either etoposide treatment and/or a course of EAE (Fig. 7B–E) and that etoposide treatment of EAE is unaffected by prior LCMV infection (Supplemental Fig. 4). Etoposide treatment did not alter the pronounced expansion of LCMV GP33–41-specific CD8+ T cells and LCMV GP61–80-specific CD4+ T cells, when compared with vehicle control mice, regardless of EAE. All groups showed similar multiple-fold expansion of memory cells, as assessed by Ag-specific tetramer staining and compared with resting B6 mice with established anti-LCMV memory or naive B6 mice responding to a de novo clone 13 infection (Fig. 7B, 7C). These results clearly show that mice treated for EAE and purged of MOG-specific T cells by etoposide still possess memory T cells that can undergo comparable secondary Ag-driven expansion to viral rechallenge. Furthermore, the expanded memory T cells from all of the treatment groups demonstrated equivalent IFN-γ production following ex vivo peptide restimulation (Fig. 7D, 7E). In fact, the LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells from mice that had EAE and were treated with etoposide showed enhanced IFN-γ production (Fig. 7D). As expected, the age-matched, untreated, naive B6 mice infected with clone 13 showed reduced IFN-γ production from both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells.

Importantly, the expanded LCMV-specific memory T cells from all of the treatment groups showed equal functionality in the clearance of an LCMV clone 13 infection (Fig. 7F), thus demonstrating that even upon targeted ablation of encephalitogenic T cells from mice with EAE, a robust functional memory subset persists that is capable of clearing the normally persistent clone 13. As expected, naive mice were unable to clear a primary clone 13 infection. Taken together, these data clearly demonstrate that pre-existing functional memory T cells capable of inducing sterilizing immunity to viral rechallenge do survive in mice ablated of autoreactive T cells by etoposide.

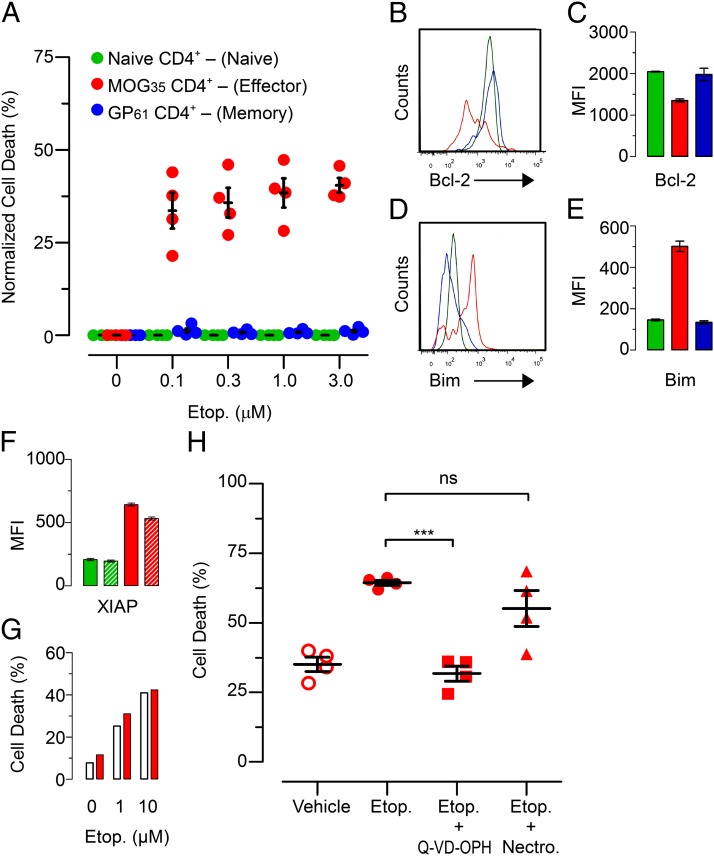

Etoposide selectively induces apoptosis of activated encephalitogenic T cells

We have demonstrated that etoposide treatment decreases the total number of encephalitogenic T cells in mice with EAE while not affecting the numbers of memory or naive T cells. We next wanted to confirm that the decreases we observed in EAE pathology were from etoposide-mediated cell death of encephalitogenic T cells. In vitro treatment with etoposide previously has been shown to induce death in encephalitogenic T cells (40); however, the specificity of etoposide-mediated death was not investigated. To test this, we cultured purified CD4+ T cells from mice that were 12 d post-EAE induction and 45 d post-LCMV Armstrong infecting, allowing us to have MOG-specific encephalitogenic CD4+ T cells, memory LCMV GP61+-specific CD4+ T cells, and naive CD4+ T cells all in the same mouse. CD4+ T cells were cultured in vitro with increasing concentrations of etoposide to determine the survival of each T cell population. When normalized to the spontaneous death in culture for untreated cells, the encephalitogenic CD4+ T cells showed substantial apoptosis induction with etoposide treatment that increased with dosage, 37–41% death (Fig. 8A). In contrast, both memory and naive T cells showed minimal death in culture regardless of the concentration of etoposide in which they were cultured. These data confirm that etoposide selectively induces apoptosis in activated encephalitogenic T cells while sparing both memory and naive T cells at the same time. One likely explanation of the enhanced sensitivity of encephalitogenic T cells to apoptosis is dysregulation of Bcl-2 family members.

FIGURE 8.

Etoposide selectively mediates apoptosis of encephalitogenic T cells. CD4+ T cells were purified by negative selection from the spleen and inguinal lymph nodes of mice 12 d post-EAE induction. MOG–effector CD4+ T cells are defined as CD44+MOG35–55 tetramer+, GP61-memory CD4+ T cells are defined as CD44+GP61–80 tetramer+, and naive CD4+ T cells are defined as CD44−CD62L+; all three populations are defined in a CD4+CD16/32− gate. (A) CD4+ T cells were cultured for 16 h with varying concentrations of etoposide. Cells were costained to differentiate cellular populations and death was assessed by positivity for flow cytometry viability dye. Cell death was normalized to vehicle control. (B) Representative histogram of Bcl-2 staining for MOG–effector, GP61–memory, and naive CD4+ T cells (C) with cumulative data. (D) Representative histogram of Bim staining for MOG–effector, GP61–memory and naive CD4+ T cells (E) with cumulative data. (F) CD4+ T cells were purified from day 12 mice with EAE, cultured in vitro with etoposide (10 μM) and stained for XIAP expression. XIAP MFI is depicted between naive and encephalitogenic CD4+ T cells with and without etoposide treatment. (G) Purified CD4+ T cells from wild-type and Xiap−/− B6 mice were activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 in vitro. Following activation, CD4+ T cells were treated with etoposide and assessed for cell death by a flow cytometry viability dye. (H) CD4+ T cells were purified from day 12 mice with EAE and cultured in vitro with etoposide (10 μM), Q-VD-OPH (20 mg/ml), or necrostatin (30 μM) for 16 h. Cells were costained to differentiate cellular populations, and death was assessed by positivity for flow cytometry viability dye. Cumulative of two independent experiments; n = 6/group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; two-way t test.

Activated encephalitogenic T cells are primed for apoptosis

Previous work from our group has demonstrated that activated T cells express disequilibrated members of the Bcl-2 protein family as a means of undergoing cellular contraction at the conclusion of a T cell response; specifically that effector T cells express higher levels of the proapoptotic BH3 protein Bim (41, 42). To investigate the apoptotic potential of encephalitogenic T cells, we induced EAE in mice 45 d after the clearance of an LCMV infection allowing for the presence of both memory LCMV specific T cells and MOG-specific encephalitogenic T cells in the same mouse. We stained purified CD4+ T cells for Bcl-2 and Bim directly ex vivo. Encephalitogenic CD4+ T cells had diminished expression of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 compared with memory and naive CD4+ T cell populations in the same mouse (Fig. 8C). This is consistent with previously published reports on Bcl-2 expression in EAE (43). In addition, encephalitogenic CD4+ T cells expressed higher levels of Bim (Fig. 8E). This disequilibrium of survival factors in encephalitogenic T cells increases their potential for apoptosis as compared with either memory or naive T cells. Furthermore, Moore et al. (44) reported that bulk T cells from B6 mice at 21 d post-EAE induction expressed elevated levels of the inhibitor of apoptosis XIAP. Although we observed elevated XIAP expression in MOG-specific CD4+ T cells at day 12 (Fig. 8F), we found that XIAP expression does not protect activated CD4+ T cells from etoposide-mediated cell death. Purified and in vitro–activated CD4+ T cells from wild-type and Xiap−/− mice are equally susceptible to cell death mediated by etoposide (Fig. 8G). This demonstrates that XIAP expression does not confer protection against etoposide-mediated cell death. In fact, even when XIAP is overexpressed under a ubiquitin promoter in an EAE model, it only provides marginal, a fraction of a fold, protection against etoposide-mediated cell death (40).

The DNA damage response stemming from the effects of etoposide have been well described (45–48). This includes the activation of p53, and the production of the proapoptotic BH3 proteins PUMA and NOXA. When the effects of etoposide are paired with Bcl-2 family disequilibrium, it suggests a specific mechanism for the selective clearance of encephalitogenic T cells that we observe in vivo. To test whether apoptosis or necroptosis is the primary mechanism of etoposide-mediated cell death in encephalitogenic T cell, we used the pan-caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPH to prevent apoptosis (49, 50) and the RIP-1 kinase inhibitor necrostatin to prevent necroptosis (51). We found that when encephalitogenic CD4+ T cells were treated with etoposide in the presence of Q-VD-OPH cell death decreased from the level of etoposide only to the level of vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 8H). Conversely, when cells were treated with etoposide in the presence of necrostatin, no effect on cell death was observed, as compared with etoposide alone. This supports that apoptosis is the primary mechanism for etoposide- mediated cell death of encephalitogenic CD4+ T cells in EAE.

Discussion

In this study, we have tested our concept of using targeted chemotherapeutics to ablate autoreactive T cells while sparing naive and memory T cell populations. We demonstrated that the cytotoxic drug etoposide can effectively treat EAE by preferentially targeting encephalitogenic T cells to the exclusion of other protective lymphocytes. Etoposide treatment of EAE significantly decreased the total number of encephalitogenic T cells in treated mice, as determined by both MOG-specific tetramer staining and effector cytokine production. This ablation of encephalitogenic T cells led to a substantial decrease in clinical and tissue-associated pathology. Our analysis of spinal cord cross-sections reveals that etoposide treatment decreases cellular infiltration resulting in decreased demyelination and neuronal damage. In addition, we demonstrated that etoposide treatment of mice with ongoing EAE decreased the overall magnitude and numbers intra- and intermolecular spread epitopes. This suggests that the diminished severity of EAE, in both the B6 and SJL models, is due in part to limiting the breadth of additional effector T cells that become activated. In the end, etoposide-based therapy resulted in markedly reduced severity of or complete absence of EAE pathogenesis.

The true benefit of our approach is its selectivity. Importantly, the specificity resides not so much in etoposide itself, but in the approach of targeting the activation state of autoreactive effector cells. In other words, etoposide targets for removal only those T cells that are currently undergoing active Ag-driven expansion and that are primed for apoptosis by their Bcl-2 family member expression profile. Etoposide purges encephalitogenic T cells in the context of EAE. Likewise, if etoposide is given during the acute phase of a viral infection, the antiviral effector T cells would be purged. Thus, if treatment is limited to periods during or immediately following overt autoimmune pathology, etoposide shows highly specific ablation of encephalitogenic T cells while sparing the more quiescent naive and memory T cell compartments. Moreover, this approach is likely to result in a long-term “hole” in the T cells repertoire to the activating autoantigen. As we demonstrated in (23), etoposide can equally ablate highly activated T cell during a LCMV infection. Since etoposide-mediated apoptosis of effector T cells is not specified for, nor limited to, encephalitogenic or autoimmune T cells, it suggests that this approach may have more applicability in other T cell–specific autoimmune diseases.

This represents a significant and novel approach in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Moreover, this approach alleviates many of the complications associated with broad-spectrum immunosuppressant drugs currently in use. In addition, by focusing therapy on the rogue autoreactive subset of T cells at the time they are most highly active, etoposide-based therapy significantly limits off-target effects. For example, etoposide treatment may reduce reactivation of JC virus, which can lead to the fatal progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in MS patients (12), by sparing protective memory T cell populations as well as decreasing the need for global immunosuppression. Having the ability to treat MS without the risks associated with traditional immune suppression may represent a real and meaningful advance in patient care.

There is a consensus that the current protocols for the treatment of MS are insufficient. As the debate over new therapeutics is waged, the continual issue with the use of cytotoxic agents has been their lack of specificity. In this study, we have demonstrated that cytotoxic drugs, such as etoposide, can be used with increased specificity toward activated encephalitogenic T cells. Others have proposed the use of mAb treatment; although these treatments show promise in the treatment of MS, they target immune cells for elimination based on surface Ag expression and not by function. Drugs newly approved or under investigation for MS include alemtuzumab (anti-CD52, which is expressed on most lymphocytes as well as dendritic cells and monocytes) and rituximab (anti-CD20, expressed on B cells); these drugs have no specificity for the encephalitogenic T lymphocytes that drive the neural pathology. In contrast to our use of etoposide, alemtuzumab is the antithesis of functional specificity because it depletes all lymphocytes. Further studies have been done using Abs against CD25, the α-chain of the IL-2R, which is designed to target expression on activated T cells (52). However, this molecule is expressed in high concentrations on regulatory T cells, and as a result, these Abs may deplete not only activated T cells but also the regulatory compartment. Our data show that etoposide primarily clears activated effector T cells while sparing regulatory T cells (Supplemental Fig. 2), allowing for a better semblance of immune homeostasis.

The use of cytotoxic agents do carry toxicity risks, and etoposide is no different (53), yet toxicity tends to be dosage dependent. By decreasing the number of times that etoposide is administered, because it will not be needed long term to ablate encephalitogenic cells, we can decrease the risks associated with cytotoxic drugs. Decreasing treatment can be accomplished by proper timing that can mitigate epitope spread. Increasing the breadth of immunological activation to new epitopes and new proteins has been shown to propagate disease progression and be responsible for disease relapse. Etoposide treatment, even under limiting dosage, is able to prevent the activation of T cells to new neural epitopes, thus preventing disease progression and future relapse. It is not yet known whether etoposide is unique among cytotoxic agents for its immune selectivity. The cytotoxic drugs mitoxantrone and, rarely, cyclophosphamide are currently used to treat MS. Their mechanisms of action remain poorly defined, but they are likely to have some similarities to etoposide. Ongoing studies in our group are investigating this possibility. Notably, mitoxantrone is used in continuous dosing cycles in some cases until the lifetime maximum dosage has been reached. We have demonstrated that treatment with etoposide is most effective, when autoreactive T cells are in an activated effector state and that treatment while they are in a more quiescent naive or memory state is ineffective. As a result, treatment at the start of a disease flare will yield the greatest effect of ablating encephalitogenic T cells. This study reveals new insights into the mechanism of action of etoposide, and potentially other cytotoxic drugs including mitoxantrone and cyclophosphamide, in the treatment of MS.

A future alternative to cytotoxic drugs for the deletion of self-reactive T cells could be small molecule inhibitors of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members. Studies have shown that small molecule inhibitors that bind to Bcl-2, as well as its homologs Bcl-w and Bcl-xL (54), may have efficacy in animal models of autoimmunity (47, 55, 56).

Further studies will need to be conducted to determine whether other pharmaceutical compounds, including other cytotoxic drugs (e.g., mitoxantrone or cyclophosphamide) or Bcl-2 family inhibitors, can be used in a similar manner to selectively eliminate encephalitogenic T cells. In addition, studies will need to be conducted in other models of autoimmune disease, particularly where pathology may be reversed through the removal of self-reactive T cells. This study reveals new insight and potential for ablative T cell therapy of autoimmunity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Cincinnati Rheumatic Diseases Center Animal Models of Inflammatory Disease Core at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center for help with setting up our EAE model. We also thank Dr. Richard Strait (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center) for help with the analysis of TNP-OVA humoral responses, Robert Opoka for assistance in animal husbandry, Colin Duckett for the Xiap−/− mice, and the National Institutes of Health tetramer core for the I-Ab MOG35–55 tetramers. We also thank Dr. Kim Seroogy (Professor, Neurology, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH) for help with analysis of the immune infiltrates in the brain and CNS.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants R01 DK081175 (to J.D.K. and D.A.H.) and R01 DK078179 (to J.D.K.).

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

- B6

- C57BL/6

- GP

- glycoprotein

- HLH

- hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

- LCMV

- lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus

- MOG

- myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- MS

- multiple sclerosis

- PLP

- proteolipid protein.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Prakash R. S., Snook E. M., Lewis J. M., Motl R. W., Kramer A. F. 2008. Cognitive impairments in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Mult. Scler. 14: 1250–1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lublin F. D., Reingold S. C., National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA) Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials of New Agents in Multiple Sclerosis 1996. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: results of an international survey. Neurology 46: 907–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frohman E. M., Racke M. K., Raine C. S. 2006. Multiple sclerosis—the plaque and its pathogenesis. N. Engl. J. Med. 354: 942–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson A. P., Barnett M. H., Parratt J. D., Prineas J. W. 2009. Multiple sclerosis: distribution of inflammatory cells in newly forming lesions. Ann. Neurol. 66: 739–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paty D. W., Li D. K., UBC MS/MRI Study Group , and IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group 1993. Interferon β-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. II. MRI analysis results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology 43: 662–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polman C. H., O’Connor P. W., Havrdova E., Hutchinson M., Kappos L., Miller D. H., Phillips J. T., Lublin F. D., Giovannoni G., Wajgt A., et al. 2006. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 354: 899–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller A. E., Rhoades R. W. 2012. Treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: current approaches and unmet needs. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 25(Suppl.): S4–S10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Billich A., Bornancin F., Dévay P., Mechtcheriakova D., Urtz N., Baumruker T. 2003. Phosphorylation of the immunomodulatory drug FTY720 by sphingosine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 47408–47415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horga A., Montalban X. 2008. FTY720 (fingolimod) for relapsing multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev. Neurother. 8: 699–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartung H., Gonsette R., König N., Kwiecinski H., Guseo A., Morrissey S. P., Krapf H. 2002. Mitoxantrone in progressive multiple sclerosis : a placebo- controlled, double-blind, randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet 360: 2018–2025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinelli Boneschi F., Vacchi L., Rovaris M., Capra R., Comi G. 2013. Mitoxantrone for multiple sclerosis. CochraneDatabase Syst. Rev. 5: CD002127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Assche G., Van Ranst M., Sciot R., Dubois B., Vermeire S., Noman M., Verbeeck J., Geboes K., Robberecht W., Rutgeerts P. 2005. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after natalizumab therapy for Crohn’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 353: 362–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen J. A., Barkhof F., Comi G., Hartung H. P., Khatri B. O., Montalban X., Pelletier J., Capra R., Gallo P., Izquierdo G., et al. 2010. Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 362: 402–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mullen J. T., Vartanian T. K., Atkins M. B. 2008. Melanoma complicating treatment with natalizumab for multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 358: 647–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furtado G. C., Marcondes M. C. G., Tsai J., Wensky A., Lafaille J. J., Furtado C., Latkowski J. 2008. Swift entry of myelin-specific T lymphocytes into the central nervous system in spontaneous autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 181: 4648–4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penaranda C., Tang Q., Bluestone J. A. 2011. Anti-CD3 therapy promotes tolerance by selectively depleting pathogenic cells while preserving regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 187: 2015–2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zocher M., Baeuerle P. A., Dreier T., Iglesias A. 2003. Specific depletion of autoreactive B lymphocytes by a recombinant fusion protein in vitro and in vivo. Int. Immunol. 15: 789–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gold R., Linington C., Lassmann H. 2006. Understanding pathogenesis and therapy of multiple sclerosis via animal models: 70 years of merits and culprits in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis research. Brain 129: 1953–1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ben-Nun A., Otmy H., Cohen I. R. 1981. Genetic control of autoimmune encephalomyelitis and recognition of the critical nonapeptide moiety of myelin basic protein in guinea pigs are exerted through interaction of lymphocytes and macrophages. Eur. J. Immunol. 11: 311–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards C. M., Glisson B. S., King C. K., Smallwood-Kentro S., Ross W. E. 1987. Etoposide-induced DNA cleavage in human leukemia cells. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 20: 162–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Maanen J. M., Retèl J., de Vries J., Pinedo H. M. 1988. Mechanism of action of antitumor drug etoposide: a review. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 80: 1526–1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jordan M. B., Allen C. E., Weitzman S., Filipovich A. H., McClain K. L. 2011. How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood 118: 4041–4052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson T. S., Terrell C. E., Millen S.H., Katz J. D., Hildeman D. A., Jordan M. B. 2013. Etoposide selectively ablates activated T cells to control the immunoregulatory disorder hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J. Immunol. 192: 84–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harlin H., Reffey S. B., Duckett C. S., Lindsten T., Thompson C. B. 2001. Characterization of XIAP-deficient mice. Mol. Cell Biol. 21: 3604–3608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood L. J., Nail L. M., Perrin N. A., Elsea C. R., Fischer A., Druker B. J. 2006. The cancer chemotherapy drug etoposide (VP-16) induces proinflammatory cytokine production and sickness behavior-like symptoms in a mouse model of cancer chemotherapy-related symptoms. Biol. Res. Nurs. 8: 157–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wojciechowski S., Jordan M. B., Zhu Y., White J., Zajac A. J., Hildeman D. A. 2006. Bim mediates apoptosis of CD127lo effector T cells and limits T cell memory. Eur. J. Immunol. 36: 1694–1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hildeman D., Yanez D., Pederson K., Havighurst T., Muller D. 1997. Vaccination against persistent viral infection immunopathological disease. J. Virol. 71: 9672‑9678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strait R. T., Morris S. C., Finkelman F. D. 2006. IgG-blocking antibodies inhibit IgE-mediated anaphylaxis in vivo through both antigen interception and FcγRIIb cross-linking. J. Clin. Invest. 116: 833–841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerlero de Rosbo N., Mendel I., Ben-Nun A. 1995. Chronic relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with a delayed onset and an atypical clinical course, induced in PL/J mice by myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)-derived peptide: preliminary analysis of MOG T cell epitopes. Eur. J. Immunol. 25: 985–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sospedra M., Martin R. 2005. Immunology of multiple sclerosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23: 683–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park H., Li Z., Yang X. O., Chang S. H., Nurieva R., Wang Y. H., Wang Y., Hood L., Zhu Z., Tian Q., Dong C. 2005. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat. Immunol. 6: 1133–1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrington L. E., Hatton R. D., Mangan P. R., Turner H., Murphy T. L., Murphy K. M., Weaver C. T. 2005. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat. Immunol. 6: 1123–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hande K. R. 1998. Etoposide: four decades of development of a topoisomerase II inhibitor. Eur. J. Cancer 34: 1514–1521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown A. M., McFarlin D. E. 1981. Relapsing experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in the SJL/J mouse. Lab. Invest. 45: 278–284 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tuohy V. K., Kinkel R. P. 2000. Epitope spreading: a mechanism for progression of autoimmune disease. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 48: 347–351 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McMahon E. J., Bailey S. L., Castenada C. V., Waldner H., Miller S. D. 2005. Epitope spreading initiates in the CNS in two mouse models of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Med. 11: 335–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wherry E. J., Ha S.-J., Kaech S. M., Haining W. N., Sarkar S., Kalia V., Subramaniam S., Blattman J. N., Barber D. L., Ahmed R. 2007. Molecular signature of CD8+ T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity 27: 670–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kotturi M. F., Botten J., Maybeno M., Sidney J., Glenn J., Bui H.-H., Oseroff C., Crotty S., Peters B., Grey H., et al. 2010. Polyfunctional CD4+ T cell responses to a set of pathogenic arenaviruses provide broad population coverage. Immunome Res. 6: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moskophidis D., Lechner F., Pircher H., Zinkernagel R. M. 1993. Virus persistence in acutely infected immunocompetent mice by exhaustion of antiviral cytotoxic effector T cells. Nature 362: 758–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore C. S., Hebb A. L. O., Blanchard M. M., Crocker C. E., Liston P., Korneluk R. G., Robertson G. S. 2008. Increased X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) expression exacerbates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). J. Neuroimmunol. 203: 79–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wojciechowski S., Tripathi P., Bourdeau T., Acero L., Grimes H. L., Katz J. D., Finkelman F. D., Hildeman D. A. 2007. Bim/Bcl-2 balance is critical for maintaining naive and memory T cell homeostasis. J. Exp. Med. 204: 1665–1675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grayson J. M., Weant A. E., Holbrook B. C., Hildeman D. 2006. Role of Bim in regulating CD8+ T-cell responses during chronic viral infection. J. Virol. 80: 8627–8638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elyaman W., Kivisäkk P., Reddy J., Chitnis T., Raddassi K., Imitola J., Bradshaw E., Kuchroo V. K., Yagita H., Sayegh M. H., Khoury S. J. 2008. Distinct functions of autoreactive memory and effector CD4+ T cells in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Am. J. Pathol. 173: 411–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moore C. S., Hebb A. L. O., Robertson G. S. 2008. Inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) profiling in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) implicates increased XIAP in T lymphocytes. J. Neuroimmunol. 193: 94–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arva N. C., Gopen T. R., Talbott K. E., Campbell L. E., Chicas A., White D. E., Bond G. L., Levine A. J., Bargonetti J. 2005. A chromatin-associated and transcriptionally inactive p53-Mdm2 complex occurs in mdm2 SNP309 homozygous cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 26776–26787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smeenk L., van Heeringen S. J., Koeppel M., Gilbert B., Janssen-Megens E., Stunnenberg H. G., Lohrum M. 2011. Role of p53 serine 46 in p53 target gene regulation. PLoS One 6: e17574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zall H., Weber A., Besch R., Zantl N., Häcker G. 2010. Chemotherapeutic drugs sensitize human renal cell carcinoma cells to ABT-737 by a mechanism involving the Noxa-dependent inactivation of Mcl-1 or A1. Mol. Cancer 9: 164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grandela C., Pera M. F., Grimmond S. M., Kolle G., Wolvetang E. J. 2007. p53 is required for etoposide-induced apoptosis of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Res. 1: 116–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Terrell C. E., Jordan M. B. 2013. Perforin deficiency impairs a critical immunoregulatory loop involving murine CD8+ T cells and dendritic cells. Blood 121: 5184–5191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuželová K., Grebeňová D., Brodská B. 2011. Dose-dependent effects of the caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPh on different apoptosis-related processes. J. Cell. Biochem. 112: 3334–3342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Degterev A., Hitomi J., Germscheid M., Ch’en I. L., Korkina O., Teng X., Abbott D., Cuny G. D., Yuan C., Wagner G., et al. 2008. Identification of RIP1 kinase as a specific cellular target of necrostatins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4: 313–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oh U., Blevins G., Griffith C., Richert N., Maric D., Lee C. R., McFarland H., Jacobson S. 2009. Regulatory T cells are reduced during anti-CD25 antibody treatment of multiple sclerosis. Arch. Neurol. 66: 471–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Imashuku S. 2007. Etoposide-related secondary acute myeloid leukemia (t-AML) in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 48: 121–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oltersdorf T., Elmore S. W., Shoemaker A. R., Armstrong R. C., Augeri D. J., Belli B. A., Bruncko M., Deckwerth T. L., Dinges J., Hajduk P. J., et al. 2005. An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature 435: 677–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Azmi A. S., Mohammad R. M. 2009. Non-peptidic small molecule inhibitors against Bcl-2 for cancer therapy. J. Cell. Physiol. 218: 13–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bardwell P. D., Gu J., McCarthy D., Wallace C., Bryant S., Goess C., Mathieu S., Grinnell C., Erickson J., Rosenberg S. H., et al. 2009. The Bcl-2 family antagonist ABT-737 significantly inhibits multiple animal models of autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 182: 7482–7489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.