Abstract

Aims. The objectives of this study were (a) to report our experience regarding the association between neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs); (b) to provide a systematic review of the literature in this field; and (c) to compare the features of NF1-associated GISTs with those reported in sporadic GISTs. Methods. We reported two cases of NF1-associated GISTs. Moreover we reviewed 23 case reports/series including 252 GISTs detected in 126 NF1 patients; the data obtained from different studies were analyzed and compared to those of the sporadic GISTs undergone surgical treatment at our centre. Results. NF1 patients presenting with GISTs had a homogeneous M/F ratio with a mean age of 52.8 years. NF1-associated GISTs were often reported as multiple tumors, mainly incidental, localized at the jejunum, with a mean diameter of 3.8 cm, a mean mitotic count of 3.0/50 HPF, and KIT/PDGFRα wild type. We reported a statistical difference comparing the age and the symptoms at presentation, the tumors' diameters and localizations, and the risk criteria of the NF1-associated GISTs comparing to those documented in sporadic GISTs. Conclusions. NF1-associated GISTs seem to have a distinct phenotype, specifically younger age, distal localization, small diameter, and absence of KIT/PDGRFα mutations.

1. Introduction

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1, von Recklinghausen's disease) is an autosomal-dominant disorder occurring in 1 out of 3,000 births that is caused by the inactivation of the NF1 gene. NF1 is a tumor suppressor that encodes for the neurofibromin protein, a member of the Ras family. The inactivation might be a familial condition with an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern; otherwise it might be sporadic [1, 2].

The disease is characterized by cutaneous neurofibromas, café au lait macules, axillary and inguinal freckling, and Lisch nodules.

NF1 is also associated with several tumors, including tumors of the nervous system (central and peripheral) and of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, with the gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) indicated as the most common GI NF1-associated tumors [3].

GISTs are mesenchymal and usually kit positive tumors, originating from the interstitial cell of Cajal or their related stem cells [4, 5]. The incidence of the GISTs has been reported in 10–20 new cases per million/year [6]. GISTs represent 80% of mesenchymal GI tumors and 0.1–3% of all GI malignancies [7–10]. GIST's pathogenesis is related to kit and platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRa) mutation. Kit and PDGFRa encode for similar type III receptor tyrosine kinase proteins: these mutations are somatic and occur only in the neoplastic tissue of sporadic GISTs, whereas constitutional mutations in familial GISTs occur in every cell of the body and are inheritable [11–14].

Over the last few years several case reports documented the association between GISTs and NF1 syndrome; however to date there is a lack of reviews in this field with the objective of describing the clinical and pathological features of GISTs presenting in NF1 patients.

Aims of this study were (a) to report our experience regarding this association; (b) to provide a systematic review of the literature in this field including 252 GISTs described in 126 NF1 patients with the objective of analyzing the clinical, pathological, and molecular features of these tumors in patients affected by this condition; and (c) to compare the clinical/pathological features of GISTs presenting associated with NF1 with those reported in sporadic GISTs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Review: Data Source and Search Strategies

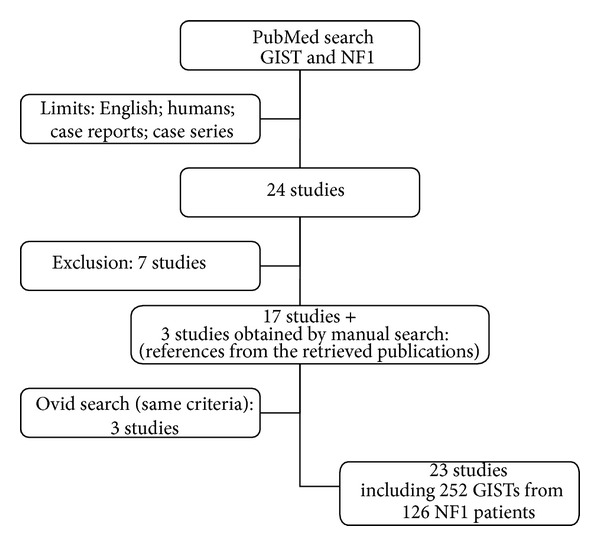

This investigation has been conducted adhering at the PRISMA statements for review and meta-analysis (Figure 1). We conducted a systematic review of the literature by searching PubMed database for all published series and case reports investigating the association of NF1 and GIST (Keywords: “GIST and NF1”, language: English; filter “human” studies); the Medline search was conducted at the beginning of September 2013 and retrieved 24 papers. We also included references from the retrieved publications (n 3 manuscripts).

Figure 1.

Systematic review: study design according to the PRISMA statement.

Published series with the aim to investigate exclusively the molecular profile (n 1 study), the NF1 radiological features (n 1 study), or its association with other gastrointestinal tumors, for example, gastrointestinal schwannomas (n 1 article), were excluded.

Moreover we also excluded those reviews in this field that did not include patients' presentation (n 2 studies), one paper that reported GISTs without signs of NF1 syndrome and another study investigating the intestinal neurofibromatosis.

The same search strategies have been applied to the Ovid database and provided the addition of 3 more papers (after the manual removal of duplicate references).

Overall the systematic review has been conducted on 23 articles published from 2004 to date [15–37], plus the two patients we herein presented.

Authors conducting this review of the literature were blinded to authors' and journals' names and did not consider any journal's score (e.g., journal's Impact Factors) of the published case/series as an exclusion criteria for this study.

We collected data regarding study populations, number of investigated patients and GISTs, familiar or sporadic history of NF1, age at presentation of the GISTs, symptoms, sex of the patients, tumors' location, tumors' diameter, and number of mitoses. The morphologic appearance and cellular descriptions (generally referred to as epithelioid, spindle, and mixed cells) were also recorded along with the immunohistochemistry for CD117 (c-kit), S-100 protein, CD-34, and SMA-alpha. Whenever available, we included data regarding GIST risk classification and the studies investigating c-kit and PDGFRa mutations.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

With respect to the systematic review, we pooled together the data obtained from different studies in order to analyze a large series of patients and of clinical and pathological variables. Patients' clinical features and tumors' pathological records were thus analysed using means and standard deviations for quantitative variables and using frequencies and percents for categorical variables.

Moreover, the clinical and pathological features of the GISTs presenting associated with the NF1 syndrome (including age at presentation, M/F ratio, symptoms, tumors' diameter and localization, and risk criteria) retrieved from the international literature have been compared for statistical purpose to those obtained in a personal case series of sporadic GISTs undergone surgical resection at our department. Variables were compared using the t-test for continuous variable and the Chi-square test for categorical variables; all test were two-tailed and a P < 0.05 was considered of statistical significance value. All statistical evaluations were conducted with the statistical software MedCalc version 11.4.4.0.

3. Results

3.1. Personal Cases Series Presentation

Case 1 —

A 71-year-old male patient with a history of NF1 presented with an abdominal mass incidentally detected in the work-up of an abdominal aortic aneurism.

The patient's past medical history was consistent with hypertension and cholecystectomy for lithiasis. The abdominal CT scan documented a gastric mass of 3.6 cm (Figure 2); the patient underwent a gastroscopy that documented an atrophic gastritis. The patient was scheduled for a surgical procedure and a laparoscopic wedge resection of the posterior gastric wall was performed. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged on 6th postoperative day.

The pathological examination documented a gastric GIST (c-KIT+, DOG1+) with spindle cell morphology, with a mitotic count of 2/50 HPF thus classified as a “low grade risk,” according to Miettinen's classification. The patient is currently disease-free, 8 months after the surgical resection.

Figure 2.

Abdominal CT scan documenting a 3.6 cm GIST of the stomach.

Case 2 —

A 56-year-old man was admitted to our department with a familial history of NF1 (Figure 3) and a past medical history consistent with a pheochromocytoma in 1994. The patient underwent a surgical resection elsewhere for a duodenal GIST (third portion) and presented to our attention with a relapse of the disease 7 months after the primary surgical resection. The patient was scheduled for a surgical procedure of duodenotomy and excision of the recurrence. The pathological description was consistent with a 4 cm c-KIT and CD34 positive GIST with 9 mitosis/50 HPF thus classified as at “intermediate risk” according to Miettinen's classification. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged in 9th postoperative day. The patient is disease-free, 8 years after the surgical treatment.

Figure 3.

Cutaneous neurofibromas in patient affected by NF1 and duodenal GIST of the hand (a) and back (b).

3.2. Systematic Review

Table 1 summarizes the studies included in the present review of the literature. For the purpose of this investigation we pooled patients from different studies (23 articles, plus the present single centre experience), obtaining the clinical and pathological records of 252 GISTs detected in 126 NF1 patients [15–37].

Table 1.

Systematic review of the literature from 2004 to date.

| Reference | Author | Journal | Year | No. of patients | No. of GISTs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [15] | Cheng et al. | Digestive Diseases and Sciences | 2004 | 3 | 5 |

| [16] | Kinoshita et al. | The Journal of pathology | 2004 | 7 | 29 |

| [17] | Takazawa et al. | The American Journal of Surgical pathology | 2005 | 9 | 36 |

| [18] | Andersson et al. | The American Journal of Surgical pathology | 2005 | 15 | 27 |

| [19] | Miettinen et al. | The American Journal of Surgical pathology | 2006 | 45 | 45 |

| [20] | Maertens et al. | Human Molecular Genetics | 2006 | 3 | 7 |

| [21] | Nemoto et al. | Journal of Gastroenterology | 2006 | 1 | 1 |

| [22] | Bümming et al. | Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology | 2006 | 1 | 4 |

| [23] | Teramoto et al. | lnternational Journal of Urology | 2007 | 2 | 2 |

| [24] | Stewart et al. | Journal of Medical Genetics | 2007 | 2 | 3 |

| [25] | Kramer et al. | World Journal of Gastroenterology | 2007 | 1 | 1 |

| [26] | Invernizzi et al. | Tumori | 2008 | 1 | 1 |

| [27] | Liegl et al. | The American Journal of Surgical pathology | 2009 | 16 | 16 |

| [28] | Yamamoto et al. | Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology | 2009 | 5 | 31 |

| [29] | Dell'Avanzato et al. | Surgery Today | 2009 | 1 | 2 |

| [30] | Hirashima et al. | Surgery Today | 2009 | 1 | 17 |

| [31] | Cavallaro et al. | The American Journal of Surgery | 2010 | 2 | 2 |

| [32] | Relles et al. | Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery | 2010 | 2 | 5 |

| [33] | Izquierdo and Bonastre | Anticancer Drugs | 2012 | 1 | 4 |

| [34] | Agaimy et al. | lnternational Journal of Clinical and Experimental pathology | 2012 | 2 | 3 |

| [35] | Ozcinar et al. | International Journal of Surgery Case Reports | 2013 | 1 | 4 |

| [36] | Vlenterie et al. | American Journal of medicine | 2013 | 2 | 4 |

| [37] | Sawalhi et al. | World Journal of Clinical Oncology | 2013 | 1 | 1 |

| Present experience | 2013 | 2 | 2 | ||

|

| |||||

| Total | 126 | 252 | |||

As documented in Table 1, the vast majority of the studies reported single cases or small case series, excluding the article by Miettinen reporting 45 patients followed by the experience of Liegl and Andersson (resp., 16 and 15 NF1 patients) [18, 19, 27].

Table 2 shows the results of the data analysis. Patients were documented homogeneous regarding the M/F ratio (M/F 1), with a mean age at presentation of 52.8 years. Data regarding the NF1 syndrome (as a sporadic or familial disorder) has been detected exclusively in 17 out of the 126 NF1 included patients (13.5% of the series) and notably it has been documented as familial syndrome in the vast majority of the cases (70.6%). GISTs were reported as multiple tumors in the 35.3% of the patients and the prevalent localization was documented at the jejunum site 39.2%, followed by ileus in 30.6% of the cases. GISTs appeared to be incidental in the majority of the cases (52.5%) and were reported with a mean diameter of 3.8 cm. The mean mitotic count was documented to be 3.0/50 HPF and the pathological morphology was consistent with spindle-shaped cell tumors in almost the totality of the GISTs (93.0%). Indeed 97.4% were c-kit positive and 81.6% CD34 positive; moreover, even though data regarding the DOG-1 expression were available exclusively in 17 patients, 88.2% were reported as DOG-1 positive. Opposite anti-SMA antibodies were positive in 24.1% of the cases and S-100 protein was expressed in 30.3% of the tumors. Notably desmin expression has been documented negative in all the 109 tumors analyzed. Wild-type c-kit and PDGRF alpha genes were reported in 95.2% of the tumors analyzed for any mutations.

Table 2.

Clinical and pathological features from 252 GISTs in 126 NF1 patients.

| Sex | n | % |

| M | 59.0 | 50.0 |

| F | 59.0 | 50.0 |

| Total available | 118.0 | 100.0 |

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean; SD | 52.8; 13 | |

| Range | 19.0–82.0 | |

| Familial history | n | % |

| Sporadic | 5.0 | 29.4 |

| Familial | 12.0 | 70.6 |

| Total available | 17.0 | 100.0 |

| Number of GISTs | n | % |

| 1 | 77.0 | 64.7 |

| >1 | 42.0 | 35.3 |

| Total available | 119.0 | 100.0 |

| Localization | n | % |

| Stomach | 12.0 | 5.4 |

| Duodenum | 44.0 | 19.8 |

| Jejunum | 87.0 | 39.2 |

| Ileus | 68.0 | 30.6 |

| Colon | 4.0 | 1.8 |

| Other | 6.0 | 2.7 |

| Not specified | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| Total available | 222.0 | 100.0 |

| Symptoms | n | % |

| Incidental | 21.0 | 52.5 |

| Bleeding | 11.1 | 27.5 |

| Pain | 4.0 | 10.0 |

| Palpable mass | 4.0 | 10.0 |

| Total available | 40.0 | 100.0 |

| GIST's diameter (cm) | ||

| Mean | 3.8; 4.3 | |

| Range | 0.1–29.0 | |

| Mitotic index (n/50 HPF) | ||

| Mean | 3.0; 8.2 | |

| Range | 0.0–57.0 | |

| Morphology | n | % |

| Spindle-shaped | 159.0 | 93.0 |

| Epithelioid | 9.0 | 5.3 |

| Mix | 3.0 | 1.7 |

| Total available | 171.0 | 100.0 |

| c-kit | n | % |

| Positive | 151.0 | 97.4 |

| Negative | 4.0 | 2.6 |

| Total available | 155.0 | 100.0 |

| CD34 | n | % |

| Positive | 84.0 | 81.6 |

| Negative | 19.0 | 18.4 |

| Total available | 103.0 | 100.0 |

| Anti-SMA | n | % |

| Positive | 19.0 | 24.1 |

| Negative | 60.0 | 75.9 |

| Total available | 79.0 | 100.0 |

| S-100 | n | % |

| Positive | 33.0 | 30.3 |

| Negative | 76.0 | 69.7 |

| Total available | 109.0 | 100.0 |

| Desmin | n | % |

| Positive | 0.0 | 0,0 |

| Negative | 109.0 | 100.0 |

| Total available | 109.0 | 100.0 |

| DOG-1 | n | % |

| Positive | 15.0 | 88.2 |

| Negative | 2.0 | 11.8 |

| Total available | 17.0 | 100.0 |

| c-kit/PDGRFa Mutations | n | % |

| Presence | 8.0 | 4.8 |

| Absence—wild type | 157.0 | 95.2 |

| Total available | 165.0 | 100.0 |

| Risk classification | n | % |

| Low risk | 37.0 | 64.9 |

| Intermediate risk | 10.0 | 17.5 |

| High risk | 10.0 | 17.5 |

| Total available | 57.0 | 100.0 |

Of note, the 64.9% of the GISTs were reported as low risk tumors, otherwise the 17.5% were considered at intermediate risk and the 17.5% as high risk GISTs.

3.3. Comparison with Sporadic GISTs

Clinical and pathological features of GISTs associated with NF1 syndrome (including mean age at presentation, M/F ratio, tumors' localizations, symptoms at presentation, mean diameters, and risk classification) were compared for statistical purpose with those documented in sporadic GISTs in a subset of patients undergone surgical resection at our centre from 1999 to 2009 (n 47 patients) [38]. Table 3 summarizes results of the statistical analysis. We documented a difference of statistical value analyzing the mean age at presentation: indeed according to our results patients affected by NF1 were younger compared to sporadic GISTs patients (t-test P 0.0001). Moreover, in this subset of patients, tumors were significantly smaller (t-test P 0.0003). Tumors were located mainly in the jejunum/ileus in the NF1 subgroup whereas the main localization in the sporadic group was the stomach (Chi-square test P < 0.0001); moreover in the former group the vast majority of the GISTs were incidentally detected (Chi-square test P 0.002). Moreover, even though we did not document a significant difference analyzing the M/F ratios (Chi-square test P ns), we reported a prevalence of low-risk criteria in the NF1 subgroup compared with the sporadic GISTs (Chi-square test P 0.03).

Table 3.

Comparison between GISTs presenting in NF1 patients and sporadic GISTs.

| GISTs in NF1 patients | GIST personal case series | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (years) | 52.8 | 61.4 | 0.0001* |

| Sex | |||

| M/F ratio | 1 | 1.61 | 0.2§ |

| Localization (%) | |||

| Stomach | 5.4 | 56.9 | <0.0001§ |

| Jejunum/ileus | 69.8 | 23.4 | |

| Other | 24.8 | 19.7 | |

| Symptoms (%) | |||

| Incidental | 52.5 | 19.1 | 0.002§ |

| Other | 47.5 | 80.9 | |

| Diameter | |||

| Mean (cm) | 3.8 | 7.4 | 0.0003* |

| Risk classification (%) | |||

| Low risk | 64.9 | 41.3 | 0.03§ |

| Intermediate risk | 17.5 | 21.7 | |

| High risk | 17.5 | 37.0 |

*t-test; §Chi-square test.

4. Discussion

In this review we highlighted the clinical, pathological, and molecular features of GISTs detected in NF1 patients and, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first and most numerically relevant systematic analysis of the literature in this field. Moreover we reported our single centre experience regarding 2 GISTs detected in NF1 patients. Of note, from 1999 to date we treated 91 GISTs; thus the cases herein reported represent 2.2% of our series.

GISTs are commonly associated with NF1 syndrome, since a past study conducted on an autopsy series documented a GIST in one third of the NF1 patients [39].

GISTs associated with NF1 syndrome seem to have however a distinct phenotype: Miettinen reported that they occur in younger patients compared with sporadic GISTs that are often multiple and occur in the duodenum or small intestine [40].

Consistently with these findings, in our systematic review we highlighted that the mean age at presentation was 52.8 years and they are detected as multiple lesions in 35.3% of the cases, occurring in distal sites as the jejunum and small intestine.

Indeed in our previous research conducted on 47 primary GISTs patients, we reported a mean age at presentation of 61.4 years (median 62 years), none of the patients presented multiple lesions, and the most reported localization was the stomach, representing 59.6% of the tumors' sites [38].

Moreover, GISTs associated with NF1 patients have been described as clinically indolent and often asymptomatic, with low mitotic rates [40]. Indeed, we reported that 52.5% of the cases were described as incidental findings, whereas in our previous case series on GISTs, the patients were reported asymptomatic in 19.2% of the cases. Mean mitotic rate has been herein documented as 3/50 HPF; however also in our previous research 74.5% of the tumors had a mitotic count <5/50 HPF [38].

Notably a mutation in kit or PDGFR alpha genes has been reported exclusively in 4.8% of the cases.

Recently those GISTs associated with Carney Triad, Carney-Stratakis syndrome, along with young and pediatric GISTs have been documented to have a loss of succinate dehydrogenase subunit B (SDHB) expression, a mitochondrial protein [41–43]. On the basis of the SDHB expression, it has been recently proposed that GISTs could be differentiated into 2 characteristic subgroups: type 1 SDHB-positive and type 2 SDHB-negative [41]. Type 1 GISTs usually occur in adults with no predilection of tumor's locations, show homogeneous M/F, present KIT or PDGFRA mutations, and, generally, may benefit from the imatinib treatment. Type 2 GISTs occur usually in paediatric/young female patients almost exclusively in the stomach and present an epithelioid morphology. These tumors are usually c-kit and PDGFRa wild type and do not respond to the molecular treatment with imatinib [44].

Even though NF1 associated GISTs have been documented to be type 1 SDHB-positive tumors [43], they could be differentiated by several features including the predilection of localization to jejunum/small intestines, common tumor multiplicity, and the lack of GIST-specific mutations (kit and PDGFRa); moreover and alike the SDHB type 2 tumors, they do not respond well to imatinib treatment [43, 45, 46].

In conclusion, a wide review of the literature in this field documented that GISTs detected in NF1 patients seem to have a peculiar and distinct phenotype, different than the one commonly reported GISTs including younger age at presentation, distal localization, small diameter, low mitotic rate, and absence of kit and/or PDGRFa mutations. Moreover the vast majority of these tumors were documented to be kit positive consistent with spindle-shaped cells and were considered as low-risk neoplasms.

Authors' Contribution

Pier Federico Salvi and Laura Lorenzon contributed equally to the study.

References

- 1.Neurofibromatosis Conference statement. National institutes of health consensus development conference. Archives of Neurology. 1988;45:575–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takazawa Y, Sakurai S, Sakuma Y, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of neurofibromatosis type I (von Recklinghausen’s disease) American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2005;29(6):755–763. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000163359.32734.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuller CE, Williams GT. Gastrointestinal manifestations of type 1 neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen’s disease) Histopathology. 1991;19(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1991.tb00888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 2006;130(10):1466–1478. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-1466-GSTROM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors—definition, clinical, histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic features and differential diagnosis. Virchows Archiv. 2001;438(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s004280000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nilsson B, Bümming P, Meis-Kindblom JM, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: the incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era—a population-based study in western Sweden. Cancer. 2005;103(4):821–829. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burkill GJC, Badran M, Al-Muderis O, et al. Malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor: distribution, imaging features, and pattern of metastatic spread. Radiology. 2003;226(2):527–532. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2262011880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffaud F, Blay J-Y. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: biology and treatment. Oncology. 2003;65(3):187–197. doi: 10.1159/000074470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeMatteo RP, Lewis JJ, Leung D, Mudan SS, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Two hundred gastrointestinal stromal tumors: recurrence patterns and prognostic factors for survival. Annals of Surgery. 2000;231(1):51–58. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200001000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis JJ, Brennan MF. Soft tissue sarcomas. Current Problems in Surgery. 1996;33:817–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279(5350):577–580. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitamura Y, Hirota S. Kit as a human oncogenic tyrosine kinase. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2004;61(23):2924–2931. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4273-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pawson T. Regulation and targets of receptor tyrosine kinases. European Journal of Cancer. 2002;38(supplement 5):S3–S10. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)80597-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubin BP, Singer S, Tsao C, et al. KIT activation is a ubiquitous feature of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Research. 2001;61(22):8118–8121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng S-P, Huang M-J, Yang T-L, et al. Neurofibromatosis with gastrointestinal stromal tumors: insights into the association. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2004;49(7-8):1165–1169. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000037806.14471.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinoshita K, Hirota S, Isozaki K, et al. Absence of c-kit gene mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumours from neurofibromatosis type I patients. Journal of Pathology. 2004;202(1):80–85. doi: 10.1002/path.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takazawa Y, Sakurai S, Sakuma Y, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of neurofibromatosis type I (von Recklinghausen’s disease) American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2005;29(6):755–763. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000163359.32734.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersson J, Sihto H, Meis-Kindblom JM, Joensuu H, Nupponen N, Kindblom L-G. NF1-associated gastrointestinal stromal tumors have unique clinical, phenotypic, and genotypic characteristics. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2005;29(9):1170–1176. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000159775.77912.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miettinen M, Fetsch JF, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis 1: a clinicopathologic and molecular genetic study of 45 cases. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2006;30(1):90–96. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000176433.81079.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maertens O, Prenen H, Debiec-Rychter M, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors in NF1 patients. Human Molecular Genetics. 2006;15(6):1015–1023. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nemoto H, Tate G, Schirinzi A, et al. Novel NF1 gene mutation in a Japanese patient with neurofibromatosis type 1 and a gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;41(4):378–382. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1772-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bümming P, Nilsson B, Sörensen J, Nilsson O, Ahlman H. Use of 2-tracer PET to diagnose gastrointestinal stromal tumour and pheochromocytoma in patients with Carney triad and neurofibromatosis type 1. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;41(5):626–630. doi: 10.1080/00365520500434838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teramoto S, Ota T, Maniwa A, et al. Two von Recklinghausen’s disease cases with pheochromocytomas and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) in combination. International Journal of Urology. 2007;14(1):73–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stewart DR, Corless CL, Rubin BP, et al. Mitotic recombination as evidence of alternative pathogenesis of gastrointestinal stromal tumours in neurofibromatosis type 1. Journal of medical genetics. 2007;44(1, article e61) doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.043075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kramer K, Hasel C, Aschoff AJ, Henne-Bruns D, Wuerl P. Multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors and bilateral pheochromocytoma in neurofibromatosis. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2007;13(24):3384–3387. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i24.3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Invernizzi R, Martinelli B, Pinotti G. Association of GIST, breast cancer and schwannoma in a 60-year-old woman affected by type-1 von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis. Tumori. 2008;94(1):126–128. doi: 10.1177/030089160809400123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liegl B, Hornick JL, Corless CL, Fletcher CDM. Monoclonal antibody DOG1.1 Shows higher sensitivity than KIT in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors, including unusual subtypes. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2009;33(3):437–446. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318186b158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamamoto H, Tobo T, Nakamori M, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1-related gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a special reference to loss of heterozygosity at 14q and 22q. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 2009;135(6):791–798. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0514-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dell’Avanzato R, Carboni F, Palmieri MB, et al. Laparoscopic resection of sporadic synchronous gastric and jejunal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: report of a case. Surgery Today. 2009;39(4):335–339. doi: 10.1007/s00595-008-3863-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirashima K, Takamori H, Hirota M, et al. Multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors in neurofibromatosis type 1: report of a case. Surgery Today. 2009;39(11):979–983. doi: 10.1007/s00595-009-3963-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cavallaro G, Basile U, Polistena A, et al. Surgical management of abdominal manifestations of type 1 neurofibromatosis: experience of a single center. American Surgeon. 2010;76(4):389–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Relles D, Baek J, Witkiewicz A, Yeo CJ. Periampullary and duodenal neoplasms in neurofibromatosis type 1: two cases and an updated 20-year review of the literature yielding 76 cases. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2010;14(6):1052–1061. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Izquierdo ME, Bonastre MT. Patient with high-risk GIST not associated with c-KIT mutations: same benefit from adjuvant therapy? Anticancer Drugs. 2012;23(supplement):S7–S9. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3283559fbc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agaimy A, Vassos N, Croner RS. Gastrointestinal manifestations of neurofibromatosis type 1 (Recklinghausen’s disease): clinicopathological spectrum with pathogenetic considerations. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology. 2012;5(9):852–862. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ozcinar B, Aksakal N, Agcaoglu O, et al. Multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors and pheochromocytoma in a patient with von Recklinghausen’s disease. International Journal of Surgery Case Reports. 2013;4(2):216–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vlenterie M, Flucke U, Hofbauer LC, et al. Pheochromocytoma and gastrointestinal stromal tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis type I. American Journal of Medicine. 2013;126(2):174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sawalhi S, Al-Harbi K, Raghib Z, Abdelrahman AI, Al-Hujaily A. Behavior of advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor in a patient with von-Recklinghausen disease: case report. World Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;4:70–74. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v4.i3.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caterino S, Lorenzon L, Petrucciani N, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: correlation between symptoms at presentation, tumor location and prognostic factors in 47 consecutive patients. World Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2011;9, article 13 doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zoller ME, Rembeck B, Oden A, Samuelsson M, Angervall L. Malignant and benign tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 in a defined Swedish population. Cancer. 1997;79:2125–2131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miettinen M, Lasota J. Histopathology of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2011;104(8):865–873. doi: 10.1002/jso.21945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gill AJ, Chou A, Vilain R, et al. Immunohistochemistry for SDHB divides gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) into 2 distinct types. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2010;34(5):636–644. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d6150d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaal J, Stratakis CA, Carney JA, et al. SDHB immunohistochemistry: a useful tool in the diagnosis of Carney-Stratakis and Carney triad gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Modern Pathology. 2011;24(1):147–151. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang JH, Lasota J, Miettinen M. Succinate dehydrogenase subunit B (SDHB) is expressed in neurofibro-matosis 1-associated gastrointestinal stromal tumors (Gists): implications for the SDHB expression based classification of gists. Journal of Cancer. 2011;2:90–93. doi: 10.7150/jca.2.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pasini B, McWhinney SR, Bei T, et al. Clinical and molecular genetics of patients with the Carney-Stratakis syndrome and germline mutations of the genes coding for the succinate dehydrogenase subunits SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2008;16(1):79–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mussi C, Schildhaus H-U, Gronchi A, Wardelmann E, Hohenberger P. Therapeutic consequences from molecular biology for gastrointestinal stromal tumor patients affected by neurofibromatosis type 1. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14(14):4550–4555. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee J-L, Kim JY, Ryu M-H, et al. Response to imatinib in KIT- and PDGFRA-wild type gastrointestinal stromal associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2006;51(6):1043–1046. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-8003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]