Antimicrobial peptides as a means to combat antibiotic resistance

The rise of antibiotic resistance has emphasized the shortcomings in antibiotic drug development (Boucher et al., 2013). The move from biological based discovery methods to chemical approaches to identify candidates has left the antibiotic pipeline painfully dry (Lewis, 2013). The paucity of compounds that are effective against antibiotic resistant pathogens has led to great interest in antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) as potential solutions to the rise of resistant organisms (Hancock and Sahl, 2006; Fox, 2013). AMPs are short (5–50 amino acid) peptides that are produced by virtually all organisms as part of an innate immune system. There are 2,398 AMPs that have been reported (Antimicrobial Peptide Database—September 2013) and over 80% are cationic AMPs (CAMPs). Most positively charged AMPs interact with anionic bacterial membranes (Schmidtchen and Malmsten, 2013) which leads to a rapid breakdown in membrane function and subsequent cell death (Wimley, 2010). It is this mechanism of action that is of interest as it should be difficult for bacteria to develop resistance against lethal concentrations of CAMPs.

However, many AMPs have poor drug-like properties and questions remain about that their ultimate utility as antibiotics (Brogden and Brogden, 2011). Great strides have been made in improving the protease stability; pharmacokinetics and therapeutic profile of peptide drugs and these methods have been used to improve the drug-like properties of AMPs. Despite the significant developments that have been made to advance AMPs through the clinical pipeline there has yet to be an approved AMP therapeutic (Vila-Farres et al., 2012). Clearly there is an ongoing need for additional AMP candidates as a tool in the fight against antibiotic resistant bacteria.

Discovery of synthetic AMPs

Many groups are turning to non-natural sources to discover the next generation of AMPs. These efforts are focused on computational design of AMPs or by screening large libraries of peptides for new candidates. There have been significant advances in computational design of AMPs and progress continues in this field, illustrated by the recent work of Deslouches et al. (2013). However, these studies are guided by rules learned from natural AMPs and could be limiting in terms of designing peptides that function like natural AMPs with all of their inherent strengths and weaknesses. Other groups have used peptide discovery systems to screen large libraries of peptides with the aim of identifying synthetic AMPs and potentially novel classes of AMPs. Display technologies, such as phage display, are capable of producing large libraries of peptides (~107 peptides) that can be used to discover AMPs (Huang et al., 2012). However, display techniques can be difficult to adapt to whole bacteria screening and require multiple rounds of selection to identify peptides with activities similar to natural AMPs.

A promising approach to discover antibacterial candidates is to screen a target bacterium against a peptide library arrayed on a solid surface. This approach uses two different types of peptide libraries: in situ synthesized peptide arrays and libraries of peptides prepared as spotted peptide microarrays. Seminal work in the use of in situ peptide microarrays for AMP development was demonstrated for small libraries of variants of natural AMPs (Hilpert et al., 2005, 2007, 2009; Hilpert and Hancock, 2007). In this method, hundreds to thousands of peptides are synthesized on a nitrocellulose membrane, then chemically cleaved into micro well-plates where there are then tested for activity. In contrast to this approach, spotted peptide microarrays are prepared by the synthesis of thousands to tens of thousands of peptides, which are printed on glass slides using standard microarray printing technology. Peptide microarrays have been used for ligand discovery by many groups and assays have been developed to screen whole cells against immobilized ligands (Papp et al., 2012).

Discovery of antibacterial peptides directly on peptide microarrays

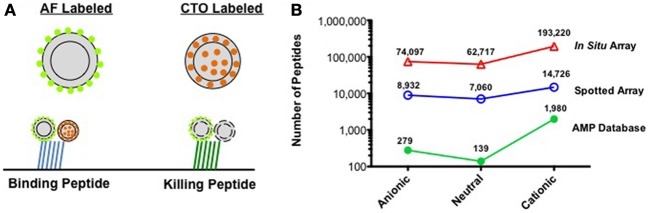

We have recently introduced an activity based assay that enables the selection of peptides with antibacterial activity directly on peptide microarrays (Domenyuk et al., 2013). In this assay, the target bacteria is labeled with an internal dye that fluoresces while the cell is metabolically active (e.g., Cell-Tracker Orange) and the exterior of the bacteria (outer membrane for Gram-negative or peptidoglycan layer for Gram-positive bacteria) is labeled with an amine-reactive dye, such as AlexaFluor-555 (Figure 1A). Fluorescently labeled bacteria are then screened against a spotted peptide microarray of 10,000, 20 amino acid long peptides to identify peptides that bind the bacteria and those that kill the bacteria. Peptides that bind but do not kill the bacteria produce two fluorescent colors, while those that bind the bacteria and disrupt the membrane produce one signal. Using this system, we were able to identify peptides that inhibited growth of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC's) in the 20 μM range.

Figure 1.

(A) Activity based bacterial screening to identify peptides that bind and those that kill a specific pathogen. AF, AlexaFluor-555; CTO, Cell-Tracker Orange. (B) Number of peptides based on net charge for AMPs described in the AMP Database, the 30,000 peptides used in spotted peptide arrays, and the 330,000 peptides used in the first generation in situ peptide array produced in our laboratory.

This approach has several important advantages as a source of antibacterial peptides. First, the system can be used to screen a wide variety of bacteria. Laboratory strains or clinical isolates can be easily labeled and do not require genetic modification to express a fluorescent or colorimetric indicator. The labeling procedures are robust and effective for Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Second, the method is rapid; bacteria can be labeled, screened, and analyzed in the same day. Additionally, the convenience of solid phase synthesis enables the incorporation of non-natural amino acids, such as D-amino acids or β-amino acids, into peptide libraries, enabling the direct screening of protease stabilized peptides. The in vitro assay format is very flexible in terms of the screening conditions, buffers, sera or media that can be used. Finally, peptide libraries can be designed without the inherent biases present in natural AMPs, potentially enabling the discovery of active peptides that function with novel mechanisms of action.

Future directions for peptide array based discovery—selection of peptides that specifically target AMP resistant bacteria

In our opinion, the future of array based AMP discovery lays in the selective targeting of antibiotic and AMP resistant bacteria over normal flora. This could be possible due to the convergence of several parallel avenues of technical and scientific development. Recently, robust methods for the in situ synthesis of peptide microarrays with medium densities, >103–104 peptides (Loeffler et al., 2012; Price et al., 2012), and those with much higher densities, 105–106 peptides per array (Legutki, submitted) have been reported. This significantly expands the peptide sequence space that can be explored in a single experiment. This could be an especially important development in the search for peptides that are active against either intrinsically AMP resistant bacteria, such as Burkholderia cepacia complex (Loutet and Valvano, 2011), or those that acquire AMP resistance after treatment with CAMPs (Anaya-López et al., 2013; Fernández et al., 2013; Napier et al., 2013; Pelletier et al., 2013; Shireen et al., 2013). Acquired AMP resistance generally involves membrane modifications that increase the charge of the surface of the bacteria that prevents binding of CAMPs to the cell surface. This potentially is a troubling development as the vast majority of AMPs (>80%) discovered to date are cationic and there is some evidence that acquired resistance for one CAMP can extend to host AMPs (Napier et al., 2013). The latter report argues for the selection of AMPs that are not related to natural ones. For these pathogens, it is possible that neutrally charged or anionic AMPs will be effective against AMP resistant bacteria that have membranes modified with cationic groups.

It is here that the recent advances in in situ peptide array synthesis could become important. As peptide libraries can be designed with a more even distribution of charged peptides, large numbers of neutral and anionic peptides can be screened against a resistant pathogen. This is illustrated in Figure 1B, where the number of anionic, neutral, and cationic peptides is plotted for: the peptides in the AMP database, the 30,000 peptides we have used in our spotted peptide libraries, and the 330,000 peptides of our recent high-density in situ peptide arrays. As can be seen, peptide arrays offer the opportunity to screen thousands to over 130,000 neutral and anionic peptides in a single experiment. It is possible that by screening both the AMP resistant and sensitive phenotype of a pathogen against this array, one could identify reduced charge peptides that inhibit the resistant phenotype with little effect on the sensitive phenotype. It is also possible that a peptide that selectively targets the AMP resistant bacteria would have a much narrower spectrum of activity toward normal flora. The selective targeting of the pathogen should help limit the spread of resistance to other species in the microbiome and maintain normal flora. It is likely that as the understanding of the host microbiome increases, the importance of targeted therapeutics will be even more evident. The use of molecular methods to quickly identify bacteria from clinical specimens is rapidly being adopted and should enable physicians to match a targeted antibiotic with the correct pathogen. Advances in peptide array discovery assays could provide a system to develop pathogen-specific antibiotics (Casadevall, 2009; Lemon et al., 2012) and lead to the discovery of the first generation of targeted antibiotics.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for the contributions of Stephen Albert Johnston, V. Domenyuk, A. Loskotov, J. Lainson, and P. Stafford to this work. This work was supported by a grant from DARPA to Stephen Albert Johnston under the 7-Day Biodefense Program and unrestricted funds to Chris W. Diehnelt and Stephen Albert Johnston.

References

- Anaya-López J. L., López-Meza J. E., Ochoa-Zarzosa A. (2013). Bacterial resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 39, 180–195 10.3109/1040841X.2012.699025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher H. W., Talbot G. H., Benjamin D. K., Bradley J., Guidos R. J., Jones R. N., et al. (2013). 10 × '20 Progress—development of new drugs active against gram-negative bacilli: an update from the infectious diseases society of america. Clin. Infect. Dis. 56, 1685–1694 10.1093/cid/cit152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogden N. K., Brogden K. A. (2011). Will new generations of modified antimicrobial peptides improve their potential as pharmaceuticals? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 38, 217–225 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadevall A. (2009). The case for pathogen-specific therapy. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 10, 1699–1703 10.1517/14656560903066837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deslouches B., Steckbeck J. D., Craigo J. K., Doi Y., Mietzner T. A., Montelaro R. C. (2013). Rational design of engineered cationic antimicrobial peptides consisting exclusively of arginine and tryptophan, and their activity against multidrug-resistant pathogens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 2511–2521 10.1128/AAC.02218-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domenyuk V., Loskutov A., Johnston S. A., Diehnelt C. W. (2013). A technology for developing synbodies with antibacterial activity. PLoS ONE 8:e54162 10.1371/journal.pone.0054162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández L., Álvarez-Ortega C., Wiegand I., Olivares J., Kocíncová D., Lam J. S., et al. (2013). Characterization of the polymyxin B resistome of pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 110–119 10.1128/AAC.01583-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J. L. (2013). Antimicrobial peptides stage a comeback. Nat. Biotech. 31, 379–382 10.1038/nbt.2572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock R. E. W., Sahl H.-G. (2006). Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat. Biotech. 24, 1551–1557 10.1038/nbt1267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilpert K., Elliott M., Jenssen H., Kindrachuk J., Fjell C. D., Körner J., et al. (2009). Screening and characterization of surface-tethered cationic peptides for antimicrobial activity. Chem. Biol. 16, 58–69 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilpert K., Hancock R. E. W. (2007). Use of luminescent bacteria for rapid screening and characterization of short cationic antimicrobial peptides synthesized on cellulose using peptide array technology. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1652–1660 10.1038/nprot.2007.203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilpert K., Volkmer-Engert R., Walter T., Hancock R. E. W. (2005). High-throughput generation of small antibacterial peptides with improved activity. Nat. Biotech. 23, 1008–1012 10.1038/nbt1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilpert K., Winkler D. F. H., Hancock R. E. W. (2007). Peptide arrays on cellulose support: SPOT synthesis, a time and cost efficient method for synthesis of large numbers of peptides in a parallel and addressable fashion. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1333–1349 10.1038/nprot.2007.160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. X., Bishop-Hurley S. L., Cooper M. A. (2012). Development of anti-infectives using phage display: biological agents against bacteria, viruses, and parasites. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 4569–4582 10.1128/AAC.00567-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon K. P., Armitage G. C., Relman D. A., Fischbach M. A. (2012). Microbiota-targeted therapies: an ecological perspective. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 137rv135 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K. (2013). Platforms for antibiotic discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 371–387 10.1038/nrd3975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeffler F., Schirwitz C., Wagner J., Koenig K., Maerkle F., Torralba G., et al. (2012). Biomolecule arrays using functional combinatorial particle patterning on microchips. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 2503–2508 10.1002/adfm.201103103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loutet S. A., Valvano M. A. (2011). Extreme antimicrobial peptide and polymyxin B resistance in the genus Burkholderia. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 1:6 10.3389/fcimb.2011.00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napier B. A., Burd E. M., Satola S. W., Cagle S. M., Ray S. M., McGann P., et al. (2013). Clinical use of colistin induces cross-resistance to host antimicrobials in acinetobacter baumannii. MBio 4:e00021-13 10.1128/mBio.00021-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp K., Szittner Z., Prechl J. (2012). Life on a microarray: assessing live cell functions in a microarray format. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69, 2717–2725 10.1007/s00018-012-0947-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier M. R., Casella L. G., Jones J. W., Adams M. D., Zurawski D. V., Hazlett K. R. O., et al. (2013). Unique structural modifications are present in the lipopolysaccharide from colistin-resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 4831–4840 10.1128/AAC.00865-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price J. V., Tangsombatvisit S., Xu G., Yu J., Levy D., Baechler E. C., et al. (2012). On silico peptide microarrays for high-resolution mapping of antibody epitopes and diverse protein-protein interactions. Nat. Med. 18, 1434–1440 10.1038/nm.2913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidtchen A., Malmsten M. (2013). Peptide interactions with bacterial lipopolysaccharides. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 18, 381–392 10.1016/j.cocis.2013.06.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shireen T., Singh M., Das T., Mukhopadhyay K. (2013). Differential adaptive responses of staphylococcus aureus to in vitro selection with different antimicrobial peptides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 5134–5137 10.1128/AAC.00780-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila-Farres X., Giralt E., Vila J. (2012). Update of peptides with antibacterial activity. Curr. Med. Chem. 19, 6188–6198 10.2174/092986712804485818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimley W. C. (2010). Describing the mechanism of antimicrobial peptide action with the interfacial activity model. ACS Chem. Biol. 5, 905–917 10.1021/cb1001558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]