Abstract

Background

Data from prospective cohort studies regarding the association between subclinical hyperthyroidism and cardiovascular outcomes are conflicting. We aimed to assess the risks of total and coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality, CHD events, and atrial fibrillation (AF) associated with endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism among all available large prospective cohorts.

Methods

Individual data on 52 674 participants were pooled from 10 cohorts. Coronary heart disease events were analyzed in 22 437 participants from 6 cohorts with available data, and incident AF was analyzed in 8711 participants from 5 cohorts. Euthyroidism was defined as thyrotropin level between 0.45 and 4.49 mIU/L and endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism as thyrotropin level lower than 0.45 mIU/L with normal free thyroxine levels, after excluding those receiving thyroid-altering medications.

Results

Of 52 674 participants, 2188 (4.2%) had subclinical hyperthyroidism. During follow-up, 8527 participants died (including 1896 from CHD), 3653 of 22 437 had CHD events, and 785 of 8711 developed AF. In age-and sex-adjusted analyses, subclinical hyperthyroidism was associated with increased total mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 1.24, 95% CI, 1.06–1.46), CHD mortality (HR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.02–1.62), CHD events (HR, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.99–1.46), and AF (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.16–2.43). Risks did not differ significantly by age, sex, or preexisting cardiovascular disease and were similar after further adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors, with attributable risk of 14.5% for total mortality to 41.5% for AF in those with subclinical hyperthyroidism. Risks for CHD mortality and AF (but not other outcomes) were higher for thyrotropin level lower than 0.10 mIU/L compared with thyrotropin level between 0.10 and 0.44 mIU/L (for both, P value for trend, ≤.03).

Conclusion

Endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism is associated with increased risks of total, CHD mortality, and incident AF, with highest risks of CHD mortality and AF when thyrotropin level is lower than 0.10 mIU/L.

Subclinical hyperthyroidism, defined by low thyrotropin level with normal concentrations of free thyroxine (FT4) and triiodothyronine (T3),1–4 has been associated with several biological effects on cardiovascular system, such as increased heart rate, left ventricular mass, carotid intimamedia thickness, and plasma fibrinogen levels.3,5 Observational studies have reported an association between subclinical hyperthyroidism and coronary heart disease (CHD),6–8 incident atrial fibrillation (AF),9–12 and cardiac dysfunction.13,14 Results from prospective cohort studies are conflicting,6,10 and study-level meta-analyses have reached contradictory conclusions, for example, regarding the association between subclinical hyperthyroidism and cardiovascular mortality.15–17 In fact, interpretation of these studies is hampered by several methodological factors: population heterogeneity, different thyrotropin cutoff levels for subclinical hyperthyroidism definition, different use of covariates, and different CHD definitions.16 Although no large randomized controlled trials have examined the effects of treating subclinical hyperthyroidism on clinically relevant outcomes, a consensus statement2 and recent guidelines4 advocate treatment of subclinical hyperthyroidism, particularly when thyrotropin level is lower than 0.10 mIU/L, to avoid long-term complications.

Individual participant data analysis from large cohort studies may help reconcile these conflicting results; allow exploration of the influence of age, sex, thyrotropin levels, and preexisting cardiovascular disease (CVD); and allows the use of a uniform thyrotropin cutoff level and outcome definitions for all participants. This approach is considered optimal for synthesizing evidence across cohorts because it is not subject to potential bias from study-level meta-analyses (ecological fallacy)18 and allows performance of time-to-event analyses.19

On the basis of data from the Thyroid Studies Collaboration,20 we aimed to assess the risks of total mortality, CHD mortality, CHD events, and AF associated with endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism.

METHODS

Similar to our previous study,20 we conducted a systematic literature search in MEDLINE and EMBASE databases from 1950 to June 30, 2011, without language restriction (eAppendix; http://www.archinternmed.com), and screened bibliographies from retrieved articles. We used a priori criteria for greater comparability and quality of the studies. We included only full-text published longitudinal cohorts reporting baseline thyroid function test results (both thyrotropin and FT4), with a control euthyroid group and prospective follow-up of mortality and CHD outcomes. We excluded studies that included only participants taking thyroid-altering medications (antithyroid drugs, thyroxine, or amiodarone) or participants with overt hyperthyroidism (low thyrotropin and high FT4 levels). We performed an additional systematic literature review for articles reporting incident AF events and updated our previous search20 to June 2011. Reviews were performed independently by 2 authors (P.B. and B.G.), and discrepancies were resolved by discussion with a third author (N.R.). Agreement between reviewers was 99.9% for first screen (titles and abstracts, κ=0.66; 95% CI, 0.62–0.72) and 100% for full-text screen (κ= 1.00).

Data were collected from original studies that joined the Thyroid Studies Collaboration20 and included individual demographic characteristics; thyrotropin, FT4, and total T3 or free T3 levels; baseline cardiovascular risk factors (eg, blood pressure, cigarette smoking, total cholesterol level, diabetes mellitus); preexisting CVD; and cardiovascular and thyroid-altering medication use at baseline and during follow-up. Data on mortality, CHD events, AF, stroke, and cancer outcomes were requested.

Similar to our previous analysis,20 we used a uniform thyrotropin cutoff level for subclinical hyperthyroidism definition, based on an expert consensus meeting of our collaboration20 (International Thyroid Conference, Paris, France, 2010), expert reviews,1,21 and previous large cohorts.10,22,23 Subclinical hyperthyroidism was defined as a thyrotropin level lower than 0.45 mIU/L with normal FT4 levels, and euthyroidism as a thyrotropin level between 0.45 and 4.49 mIU/L. Subclinical hyperthyroidism was further categorized as suppressed thyrotropin level (<0.10 mIU/L) and low but not suppressed thyrotropin level (0.10–0.44 mIU/L) according to current guidelines.1,4 Data from cohorts using first-generation thyrotropin assays (functional sensitivity, 1–2 mIU/L) were excluded9,24,25 because subclinical hyperthyroidism cannot be diagnosed using these methods.26 For FT4 and total and free T3, we used study-specific cutoff values because these measurements show greater intermethod variation than thyrotropin assays. For participants with missing values of FT4 and total or free T3 (measured in 5 of 10 cohorts [eTable]), we performed sensitivity analyses excluding (1) participants with missing FT4 values and (2) those with abnormal total or free T3 levels.1–4,21

Outcomes were total mortality, CHD mortality, CHD events, and incident AF. Stroke and cancer mortality were available for all cohorts except one.27 As in our previous analysis,20 we used homogenous definitions to reduce the heterogeneity in outcomes.15,16 Similar to the Framingham risk score,28 we limited cardiovascular mortality to CHD mortality or sudden death (eTable). We defined CHD events as nonfatal myocardial infarction or CHD death (equivalent to hard events28) or hospitalization for angina or coronary revascularization.10 We performed a sensitivity analysis with hard CHD events only (ie, CHD death, nonfatal myocardial infarction). For AF analyses, participants with baseline AF were excluded (eTable).

To assess the risks of endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism, we excluded participants using thyroxine or antithyroid drugs at baseline. To explore the possible heterogeneity between exogenous (using thyroid-altering medications) and endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism, we performed sensitivity analyses by adding participants using thyroxine or antithyroid drugs at baseline.

We conducted a study quality evaluation using previous criteria16 after collecting the following additional information from study authors: methods of outcome adjudication and ascertainment, accounting for confounders, and completeness of follow-up.

The association between subclinical hyperthyroidism and each outcome was analyzed using separate Cox proportional hazard models for each cohort (SAS 9.2 [SAS Institute Inc]; Stata 11.2 [StataCorp]). Pooled estimates for each outcome were calculated using random-effects models based on inverse variance model29 as recommended.19,30,31 Results were summarized using forest plots (Review Manager 5.1.2, Nordic Cochrane Centre). To assess heterogeneity across studies, we used the I2 statistic, which measures the inconsistency across studies attributable to heterogeneity instead of chance alone.32

Primary analyses were adjusted for age and sex (some traditional cardiovascular risk factors being potential mediators3), then further adjusted for traditional cardiovascular risk factors (systolic blood pressure, current or former smoking, total cholesterol, and diabetes). As missing data rates were lower than 3% and unlikely to substantially bias the multivariate model estimates,33 complete case analysis was used.

To explore potential sources of heterogeneity, we performed predefined subgroup and sensitivity analyses, as in our previous analysis.20 We conducted stratified analyses by age, sex, race, thyrotropin categories, and preexisting CVD. For strata with participants but no event in some subgroup analyses, we used penalized likelihood methods34 to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals. To calculate age- and sex-adjusted event rates/1000 person-years, we used Poisson models.35 We checked the proportional hazard assumption using graphical methods and the Schoenfeld test.36 For publication bias, we used age- and sex-adjusted funnel plots and the Egger test.37

RESULTS

Among identified reports, 13 prospective cohorts met all inclusion criteria (eFigure). We excluded 3 cohorts9,24,25 using first-generation thyrotropin assays,26 which were insufficiently sensitive for the diagnosis of subclinical hyperthyroidism. After the exclusion of users of thyroxine and antithyroid drugs, the final sample comprised 10 prospective cohorts with a total of 52 674 participants (median age, 59 years, 58.5% women), with median follow-up 8.8 years and total follow-up 501 922 persons-years. Of the participants, 50 486 were euthyroid and 2188 (4.2%) had endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism (Table 1), including 1884 participants (3.6%) with low but not suppressed thyrotropin (0.10–0.44 mIU/L) and 304 (0.6%) with suppressed thyrotropin (<0.10 mIU/L). The loss to follow-up rate was lower than 5% in all included studies. Total and CHD mortality were reported in all cohorts. Coronary heart disease event data were available for 22 437 participants from 6 cohorts (3.2% with subclinical hyperthyroidism), and were formally adjudicated for 4 of these 6 studies.7,8,10,38 After excluding those with AF at baseline, data for incident AF events were available in 8711 participants from 5 cohorts (9.3% with subclinical hyperthyroidism).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Individuals in Included Studies

| Source | Description of Study Sample | No. of Participants | Age, Median (Range), ya | No. (%)

|

Follow-upd

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Endogenous Subclinical Hyperthyroidismb | Thyroid Medication During Follow-upc | Start | Duration, Median (IQR) | Person-years | ||||

| United States | |||||||||

| Cardiovascular Health Study10 | Community-dwelling adults with Medicare eligibility in 4 US communities | 2569 | 71 (64–100) | 1516 (59.0) | 43 (1.7) | 57 (2.2) | 1989–1990 | 14.0 (8.6–16.4) | 31 599 |

| Health, ABC Study38 | Community-dwelling adults with Medicare eligibility in 2 US communities | 2212 | 74 (70–79) | 1062 (48.0) | 43 (1.9) | 43 (1.9) | 1997 | 8.1 (7.2–8.3) | 15 772 |

| Europe | |||||||||

| Birmingham Study6 | Community-dwelling adults aged ≥60 y from primary care practice in Birmingham, England | 1075 | 69 (60–94) | 586 (54.5) | 60 (5.6) | 5 (0.5) | 1988 | 10.2 (5.5–10.6) | 8688 |

| EPIC-Norfolk Study23 | Adults living in Norfolk, England | 12 341 | 58 (40–78) | 6596 (53.4) | 360 (2.9) | NA | 1995–1998 | 13.4 (12.6–14.3) | 158 227 |

| HUNT Study27 | Adults living in Nord-Trøndelag County, Norway | 24 291 | 55 (41–98) | 16 506 (68.0) | 381 (1.6) | NA | 1995–1997 | 8.3 (7.9–8.9) | 197 935 |

| Leiden 85-Plus Study7 | All adults aged 85 y living in Leiden, the Netherlands | 470 | 85 | 301 (64.0) | 20 (4.3) | 12 (2.6) | 1997–1999 | 5.2 (2.6–8.5) | 2650 |

| Pisa cohort8 | Patients admitted to the cardiology department in Pisa, Italy e | 2903 | 63 (19–92) | 927 (31.9) | 208 (7.2) | 0 | 2000–2005 | 2.6 (1.6–3.8) | 7966 |

| SHIP39 | Adults living in Western Pomerania, Germany | 3883 | 49 (20–81) | 1891 (48.7) | 934 (24.1) | 140 (3.6) | 1997–2001 | 10.1 (9.3–10.7) | 37 532 |

| Australia | |||||||||

| Busselton Health Study22 | Adults living in Busselton, Western Australia | 1950 | 51 (18–90) | 933 (47.8) | 49 (2.5) | 12 (0.6) | 1981 | 20.0 (20.0–20.0) | 34 676 |

| South America | |||||||||

| Brazilian Thyroid Study40 | Adults of Japanese descent living in São Paulo, Brazil | 980 | 57 (30–92) | 510 (52.0) | 90 (9.2) | NA | 1999–2000 | 7.3 (7.0–7.5) | 6877 |

| Overall | 52 674 | 59 (18–100) | 30 828 (58.5) | 2188 (4.2) | 269 (0.5) | 1981–2005 | 8.8 (7.9–12.4) | 501 922 | |

Abbreviations: EPIC, European Prospective Investigation of Cancer; Health ABC Study, Health Aging and Body Composition Study; HUNT, Nord-Trøndelag Health Study; IQR, interquartile range (25th–75th percentiles); NA, data not available; SHIP, Study of Health in Pomerania.

Participants younger than 18 years were excluded.

We used a common definition of subclinical hyperthyroidism, thyrotropin level lower than 0.45 mIU/L, and normal free thyroxine level, whereas thyrotropin cutoff values varied among the previous reports from each cohort, resulting in different numbers from previous reports. For endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism, 216 participants of Health ABC Study, 9 of Leiden 85-Plus Study, 258 of SHIP, and 14 of Busselton Health Study were excluded because of thyroid medication use at baseline.

Data on thyroid medication use (thyroxine, antithyroid drugs) were not available for 8 participants of the Health ABC Study at baseline, for 1006 participants of Birmingham Study during follow-up, and for all participants during follow-up in EPIC-Norfolk Study, HUNT Study, and Brazilian Thyroid Study.

For all cohorts, we used the maximal follow-up data that were available, which might differ from previous reports for some cohorts.

Patients with acute coronary syndrome or severe illness were excluded from the Pisa cohort.

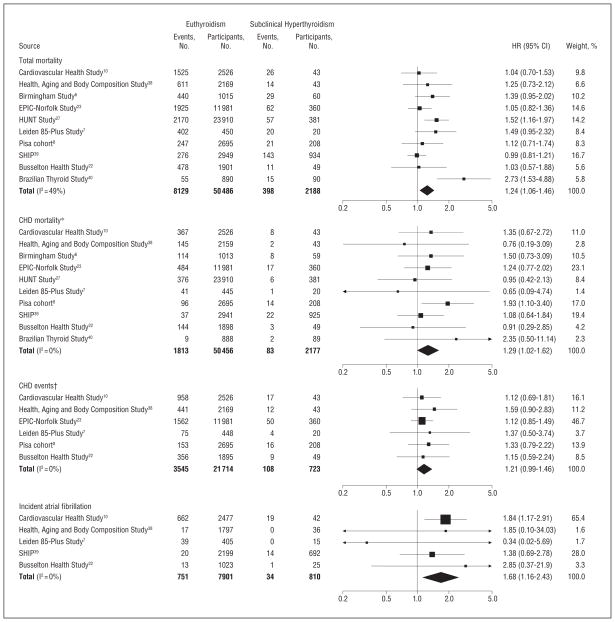

During follow-up, 8527 participants died (including 1896 from CHD), 3653 had CHD events, and 785 had incident AF. In age- and sex-adjusted analyses, the overall HR for participants with subclinical hyperthyroidism compared with euthyroidism was 1.24 (95% CI, 1.06–1.46; 23.5 vs 19.9/1000 person-years for euthyroidism) for total mortality, 1.29 (95% CI, 1.02–1.62; 5.1 vs 4.5/ 1000 person-years) for CHD mortality, 1.21 (95% CI, 0.99–1.46; 24.1 vs 20.9/1000 person-years) for CHD events, and 1.68 (95% CI, 1.16–2.43; 17.1 vs 12.5/1000 person-years) for incident AF (Figure). Stroke and cancer mortality were not higher with subclinical hyperthyroidism. Heterogeneity was present across studies for total mortality (I2 = 49%), but not for CHD mortality, CHD events or incident AF (all I2 = 0%). Among subclinical hyperthyroid and euthyroid groups, there was a trend for more late events than early events for total mortality, CHD mortality, CHD events, and AF events (for all, P value for trend, ≤.02). We subsequently examined whether heterogeneity was related to differences in risks by degree of subclinical hyperthyroidism and age.

Figure.

Total mortality, coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality, CHD events, and atrial fibrillation in endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism vs euthyroidism. Age and sex-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are represented by squares or diamonds, those to the right of the solid line indicate increased risk. The sizes of data markers are proportional to the inverse of the variance of the HRs. *Forty-one participants were excluded from the analyses of CHD mortality because of missing cause of death. †The Birmingham Study,6 HUNT (Nord-Trøndelag Health Study),27 SHIP (Study of Health in Pomerania),39 and Brazilian Thyroid Study40 were not included because follow-up data were only available for death. EPIC indicates European Prospective Investigation of Cancer.

Table 2 presents stratified analyses for total mortality, CHD mortality, CHD events, and incident AF. In age-and sex-adjusted analyses, CHD mortality and incident AF (but not other outcomes) were significantly greater in participants with lower thyrotropin levels: HRs, 1.24 (95% CI, 0.96–1.61) and 1.63 (95% CI, 1.10–2.41) for thyrotropin levels 0.10–0.44 mIU/L, respectively, vs HRs, 1.84 (95% CI, 1.12–3.00) and 2.54 (95% CI, 1.08–5.99) for thyrotropin levels lower than 0.10 mIU/L, respectively (for both, P value for trend, ≤.03 for each outcome). Men had a slightly greater risk for total mortality, CHD mortality and incident AF, without statistical significance for interaction (all P ≥ .30). Risks for Asian participants were greater for total mortality (HR, 2.73; 95% CI, 1.53–4.88) and CHD mortality (HR, 2.35; 95% CI, 0.50–11.14), with nonsignificant interaction test results (all P ≥ .40), but data on Asian participants were available from only 1 cohort.40 Risks did not differ significantly by age or preexisting CVD. All risks were similar after further adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors, with an attributable risk of 14.5% for total mortality to 41.5% for AF in those with subclinical hyperthyroidism and a population attributable risk of 0.7% for total mortality to 6.2% for AF, given the relatively low prevalence of subclinical hyperthyroidism.

Table 2.

Stratified Analyses for the Association Between Endogenous Subclinical Hyperthyroidism and the Risk of Total Mortality, CHD Mortality, CHD Events, and Atrial Fibrillation

| Variable | Total Mortality

|

CHD Mortality

b |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events/Participants, No.

|

HR (95% CI)

|

Events/Participants, No.

|

HR (95% CI)

|

|||||

| Euthyroidism | Subclinical Hyperthyroidism | Age/Sex-Adjusted | Multivariate Modela | Euthyroidism | Subclinical Hyperthyroidism | Age/Sex-Adjusted | Multivariate Modela | |

| Total population | 8129/50 486 | 398/2188 | 1.24 (1.06–1.46) | 1.17 (0.99–1.38) | 1813/50 456 | 83/2177 | 1.29 (1.02–1.62) | 1.25 (0.97–1.62) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Men | 4156/20 887 | 216/959 | 1.28 (1.10–1.49) | 1.23 (1.05–1.44) | 1069/20 869 | 50/952 | 1.52 (1.12–2.08) | 1.49 (1.07–2.08) |

| Women | 3973/29 599 | 182/1229 | 1.12 (0.91–1.40) | 1.05 (0.81–1.35) | 744/29 587 | 33/1225 | 1.22 (0.86–1.72) | 1.14 (0.78–1.68) |

| P value for interaction | .31 | .31 | .35 | .30 | ||||

| Age, y c | ||||||||

| 18–49 | 254/13 819 | 15/587 | 1.55 (0.90–2.67) | 1.70 (0.98–2.96) | 31/13 817 | 3/587 | 5.01 (1.55–16.19) | 4.24 (1.09–16.42) |

| 50–64 | 1210/17 890 d | 64/729 d | 1.29 (0.87–1.91) | 1.24 (0.85–1.80) | 236/17 885d | 7/728 d | 1.08 (0.52–2.23) | 1.02 (0.47–2.18) |

| 65–79 | 5101/16 505 | 262/797 | 1.25 (1.04–1.50) | 1.12 (0.96–1.32) | 1254/16 487 | 65/787 | 1.45 (1.11–1.89) | 1.40 (1.05–1.88) |

| ≥80 | 1561/2268 | 57/75 | 1.23 (0.94–1.61) | 1.14 (0.85–1.52) | 292/2236d | 8/73 d | 1.16 (0.58–2.30) | 0.79 (0.34–1.84) |

| P value for trend | .45 | .18 | .05 | .06 | ||||

| Race e | ||||||||

| White | 7221/47 492 | 344/2015 | 1.15 (1.00–1.31) | 1.10 (0.98–1.24) | 1593/47 471 | 72/2006 | 1.26 (0.98–1.62) | 1.26 (0.97–1.63) |

| Black | 413/1089 | 10/23 | 1.65 (0.72–3.80) | 1.30 (0.69–2.45) | 97/1084 | 1/23 | 0.96 (0.18–5.11) | 0.68 (0.12–3.79) |

| Asian | 55/890 | 15/90 | 2.73 (1.53–4.88) | 2.57 (1.43–4.62) | 9/888 | 2/89 | 2.35 (0.50–11.14) | 2.08 (0.43–10.09) |

| P for interaction | .40 | .61 | .75 | .49 | ||||

| Thyrotropin | ||||||||

| 0.45–4.49 mIU/L | 8129/50 486 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1813/50 456 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| 0.10–0.44 mIU/L | 335/1884 | 1.23 (1.04–1.45) | 1.19 (1.00–1.41) | 68/1875 | 1.24 (0.96–1.61) | 1.27 (0.97–1.67) | ||

| <0.10 mIU/L | 63/304 | 1.24 (0.90–1.71) | 1.06 (0.72–1.56) | 15/302 | 1.84 (1.12–3.00) | 1.53 (0.85–2.77) | ||

| P value for trend | .19 | .77 | .02 | .16 | ||||

| Preexisting CVD f | ||||||||

| None | 6361/45 505 | 296/1880 | 1.26 (1.01–1.58) | 1.19 (0.97–1.45) | 1229/45 481 | 52/1872 | 1.25 (0.93–1.69) | 1.27 (0.94–1.72) |

| Yes | 1315/3933 | 72/247 | 1.28 (0.96–1.70) | 1.14 (0.82–1.59) | 466/3929 | 23/245 | 1.54 (1.00–2.39) | 1.49 (0.91–2.44) |

| P value for interaction | .93 | .83 | .44 | .59 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| CHD Eventsg | Incident AFh | |||||||

| Total population | 3545/21 714 | 108/723 | 1.21 (0.99–1.46) | 1.22 (1.00–1.48) | 751/7901 | 34/810 | 1.68 (1.16–2.43) | 1.71 (1.18–2.48) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Men | 2181/10 792 | 49/313 | 1.10 (0.83–1.47) | 1.08 (0.80–1.45) | 376/3689 | 19/404 | 1.79 (1.10–2.91) | 1.96 (1.19–3.21) |

| Women | 1364/10 922 | 59/410 | 1.38 (1.06–1.79) | 1.42 (1.09–1.85) | 375/4212 | 15/406 | 1.71 (0.98–2.96) | 1.61 (0.92–2.81) |

| P value for interaction | .25 | .18 | .90 | .61 | ||||

| Age, y c | ||||||||

| 18–49 | 114/4112 | 6/122 | 2.49 (0.46–13.44) | 2.41 (0.43–13.46) | 2/1261d | 1/269 d | 1.48 (0.13–16.90) | 1.19 (0.06–23.40) |

| 50–64 | 816/7344 d | 18/261 d | 0.78 (0.49–1.26) | 0.81 (0.50–1.29) | 15/966d | 5/249 d | 2.12 (0.44–10.26) | 2.25 (0.49–10.35) |

| 65–79 | 2362/9286 | 77/305 | 1.41 (1.12–1.77) | 1.38 (1.09–1.74) | 595/4284 | 23/249 | 1.80 (1.15–2.83) | 1.79 (1.13–2.84) |

| ≥80 | 253/968 | 7/35 | 1.00 (0.49–2.03) | 1.06 (0.52–2.19) | 138/713d | 5/24 d | 1.35 (0.42–4.35) | 1.11 (0.45–2.70) |

| P value for trend | .45 | .50 | .92 | .93 | ||||

| Race e | ||||||||

| White | 3305/20 625 | 102/700 | 1.19 (0.98–1.46) | 1.21 (0.99–1.49) | 727/7013 | 34/790 | 1.69 (1.17–2.45) | 1.74 (1.20–2.52) |

| Black | 240/1089 | 6/23 | 1.52 (0.69–3.32) | 1.43 (0.65–3.16) | 24/888 | 0/20 | NA | NA |

| Asian | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| P value for interaction | .56 | .69 | NA | NA | ||||

| Thyrotropin | ||||||||

| 0.45–4.49 mIU/L | 3545/21 714 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 751/7901 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| 0.10–0.44 mIU/L | 89/572 | 1.27 (1.03–1.58) | 1.29 (1.04–1.62) | 30/735 | 1.63 (1.10–2.41) | 1.70 (1.15–2.53) | ||

| <0.10 mIU/L | 19/151 | 1.08 (0.69–1.69) | 1.13 (0.71–1.79) | 4/75 | 2.54 (1.08–5.99) | 2.34 (0.98–5.58) | ||

| P value for trend | .74 | .61 | .03 | .06 | ||||

| Preexisting CVD g | ||||||||

| None | 2492/18 022 | 79/554 | 1.32 (1.05–1.65) | 1.32 (1.05–1.66) | 545/6633 | 27/746 | 1.78 (1.16–2.74) | 1.78 (1.16–2.75) |

| Yes | 1044/3661 | 29/168 | 1.06 (0.73–1.54) | 1.15 (0.78–1.68) | 201/1205d | 7/64 d | 1.44 (0.46–4.58) d | 2.05 (0.98–4.32) d |

| P value for interaction | .33 | .55 | .73 | .75 | ||||

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HR, hazard ratio; NA, data not applicable.

Adjusted for age, sex, systolic blood pressure, current and former smoking, total cholesterol, and diabetes at baseline. The Birmingham Study was not included in this analysis because of lack of data on cardiovascular risk factors.

Forty-one participants were excluded from the analyses of CHD mortality because of missing cause of death.

These HRs were adjusted for sex and age as a continuous variable to avoid residual confounding within age strata.

Some strata from specific studies were excluded when there was no event in a subgroup.

Data on race were not available for the Birmingham study (n = 1075). The Asian group was only from the Brazilian (of Japanese descent) Thyroid Study.

Data on previous CVD were not available for the Birmingham study (n = 1075) and for 34 participants of EPIC (European Prospective Investigation of Cancer)–Norfolk Study, Leiden 85-Plus Study, and Busselton Health Study. For analysis of CHD events, 32 participants of EPIC-Norfolk Study and Busselton Health Study were excluded for the same reason.

The Birmingham Study, HUNT Study (Nord-Trøndelag Health Study), SHIP (Study of Health in Pomerania), and Brazilian Thyroid Study were not included because follow-up data were only available for death.

Participants with preexisting AF at baseline or missing data on AF during follow-up were excluded: CHS (Cardiovascular Health Study), 50 and 0, respectively; Health ABC (Aging and Body Composition) Study, 38 and 341, respectively; Leiden-85-Plus Study, 48 and 2 respectively; SHIP, 44 and 948, respectively; and Busselton Health Study, 11 and 891, respectively.

Sensitivity analyses yielded similar results (Table 3). Excluding users of thyroxine and antithyroid drugs during follow-up or adding participants taking these medications at baseline to the overall sample yielded similar HRs. The risk of CHD mortality was higher (HR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.00–2.27) after limiting the analyses to 4 studies with formal adjudication procedures.7,8,13,38 Risks of total mortality, CHD mortality and incident AF increased slightly after excluding a study with previous iodine supplementation.39 Risks were similar after further adjustment of multivariate models with lipid-lowering and antihypertensive medication use or body mass index.

Table 3.

Sensitivity Analyses of the Association Between Subclinical Hyperthyroidism and the Risk of Total Mortality, CHD Mortality, CHD Events, and Atrial Fibrillation

| Variable | Total Mortality

|

CHD Mortality

|

CHD Events

|

Incident AF

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events/Participants, No.

|

HR (95% CI) | Events/Participants, No.

|

HR (95% CI) | Events/Participants, No.

|

HR (95% CI) | Events/Participants, No.

|

HR (95% CI) | |||||

| Euthyroidism | Subclinical Hyperthyroidism | Euthyroidism | Subclinical Hyperthyroidism | Euthyroidism | Subclinical Hyperthyroidism | Euthyroidism | Subclinical Hyperthyroidism | |||||

| All eligible studies | ||||||||||||

| Random-effects model | 8129/50 486 | 398/2188 | 1.24 (1.06–1.46) | 1813/50 456 | 83/2177 | 1.29 (1.02–1.62) | 3545/21 714 | 108/723 | 1.21 (0.99–1.46) | 751/7901 | 34/810 | 1.68 (1.16–2.43) |

| Fixed-effects model | 8129/50 486 | 398/2188 | 1.19 (1.07–1.33) | 1813/50 456 | 83/2177 | 1.29 (1.02–1.62) | 3545/21 714 | 108/723 | 1.21 (0.99–1.46) | 751/7901 | 34/810 | 1.68 (1.16–2.43) |

| Definition of subclinical hyperthyroidism | ||||||||||||

| Excluding those with missing FT4 a | 8129/50 486 | 331/1838 | 1.29 (1.07–1.56) | 1813/50 456 | 72/1827 | 1.36 (1.06–1.75) | 3545/21 714 | 85/660 | 1.16 (0.93–1.44) | 751/7901 | 19/750 | 1.73 (1.19–2.50) |

| Excluding those with abnormal free or total T3 b | 8129/50 486 | 353/2045 | 1.20 (1.01–1.43) | 1813/50 456 | 75/2036 | 1.25 (0.98–1.60) | 3545/21 714 | 99/652 | 1.19 (0.98–1.46) | 751/7901 | 34/763 | 1.64 (1.14–2.35) |

| Thyroid medication usec | ||||||||||||

| Including all regardless of thyroid medication used | 8198/50 835 | 424/2336 | 1.22 (1.05–1.42) | 1830/50 803 | 86/2322 | 1.26 (1.00–1.58) | 3585/21 907 | 111/769 | 1.12 (0.93–1.36) | 758/8175 | 35/930 | 1.54 (1.07–2.22) |

| Excluding thyroid medication users at baseline or during follow-up | 8079/50 281 | 385/2124 | 1.25 (1.07–1.47) | 1799/50 252 | 81/2114 | 1.32 (1.04–1.67) | 3515/21 608 | 103/705 | 1.20 (0.98–1.46) | 735/7707 | 30/755 | 1.62 (1.09–2.39) |

| Excluding users of thyroid medication and other medications that could alter thyrotropin and/or FT4 levels e | 8045/50 161 | 376/2096 | 1.25 (1.07–1.47) | 1792/50 132 | 79/2086 | 1.31 (1.03–1.66) | 3504/21 548 | 103/704 | 1.20 (0.99–1.47) | 733/7609 | 29/734 | 1.62 (1.09–2.41) |

| Outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Excluding soft CHD outcomes f | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2934/21 714 | 99/723 | 1.28 (1.04–1.56) | NA | NA | NA |

| Only studies with formal adjudication proceduresg | NA | NA | NA | 649/7825 | 25/314 | 1.50 (1.00–2.27) | 1627/7838 | 49/314 | 1.31 (0.98–1.74) | NA | NA | NA |

| HR calculated until 5 y of follow-uph | 2972/50 486 | 184/2188 | 1.40 (1.13–1.73) | 698/50 456 | 43/2177 | 1.61 (1.16–2.22) | 1585/21 714 | 57/723 | 1.26 (0.96–1.64) | 257/6878 | 13/785 | 1.60 (0.87–2.95) |

| Excluding studies | ||||||||||||

| Excluding study of cardiac patients8 | 7882/47 791 | 377/1980 | 1.26 (1.06–1.51) | 1717/47 761 | 69/1969 | 1.18 (0.91–1.53) | 3392/19 019 | 92/515 | 1.19 (0.97–1.46) | NA | NA | NA |

| Excluding study with recent iodine supplementation39 | 7853/47 537 | 255/1254 | 1.30 (1.10–1.54) | 1776/47 515 | 61/1252 | 1.34 (1.03–1.74) | NA | NA | NA | 731/5702 | 20/118 | 1.81 (1.17–2.79) |

| Excluding study inconsistent with proportional hazard assumption6 | 7689/49 471 | 369/2128 | 1.23 (1.03–1.47) | 1699/49 443 | 75/2118 | 1.26 (0.99–1.61) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Excluding small study because of potential publication bias40 | 8074/49 596 | 383/2098 | 1.17 (1.03–1.32) | 1804/49 568 | 81/2088 | 1.27 (1.00–1.60) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Further adjustments of multivariate models | ||||||||||||

| Plus lipid-lowering and antihypertensive medications i | 5696/37 149 | 302/1738 | 1.20 (1.00–1.45) | 1200/37 122 | 56/1728 | 1.26 (0.94–1.69) | 1962/9493 | 56/337 | 1.28 (0.98–1.68) | 747/7850 | 34/805 | 1.71 (1.18–2.48) |

| Plus BMI j | 7406/48 500 | 354/2069 | 1.17 (0.99–1.38) | 1635/48 473 | 70/2059 | 1.25 (0.96–1.61) | 3440/20 941 | 102/671 | 1.23 (1.01–1.50) | 745/7843 | 34/803 | 1.68 (1.16–2.43) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; FT4, free thyroxine; HR, hazard ratio (all age and sex adjusted, except the last two rows); NA, data not applicable; T3, triiodothyronine.

A total of 350 participants were excluded in this analysis: CHS (Cardiovascular Health Study), 33; Health ABC (Aging and Body Composition), 29; HUNT Study (Nord-Trøndelag Health Study), 285; SHIP (Study of Health in Pomerania), 2; and Busselton Health Study, 1.

A total of 116 participants with subclinical hyperthyroidism and abnormal free T3 were excluded in this analysis: Birmingham Study, 4; Leiden 85-Plus Study, 18; Pisa cohort, 53; and SHIP, 41. Twenty-seven participants from the HUNT Study with subclinical hyperthyroidism and abnormal total T3 level (not measured in other studies) were also excluded.

The numbers of thyroid medication users (ie, thyroxine, antithyroid drugs) during follow-up are given in Table 1.

A total of 497 thyroid medication users (ie, thyroxine, antithyroid drugs) at baseline were added to the overall sample in this sensitivity analysis.

In addition to the 269 thyroid medication users during follow-up, 148 users of other medications that could alter thyrotropin and/or FT4 levels (ie, corticoids, amiodarone, iodine1,3,10) were excluded when data were available (CHS, 0; Health ABC Study, 61; SHIP, 87; and Busselton Health Study, 0).

Soft CHD outcomes were defined as hospitalization for angina or revascularization (coronary angioplasty or surgery), and participants with these outcomes were excluded from this analysis, which were available separately in 3 studies.7,10,38 In contrast, hard outcomes were defined as nonfatal myocardial infarction or CHD death, as defined in the current Framingham risk score.28

Formal adjudication procedures were defined as having clear criteria for the outcomes that were reviewed by experts for each potential case, which was possible in 4 studies.7,8,10,38 For this analysis, CHD adjudication based only on death certificates was not considered as a formal adjudication procedure.

Hazard ratios calculated until 5 years of follow-up were not statistically significantly different from those calculated over complete follow-up data (all P > .25). For AF events, the HR until 5 years of follow-up was reduced, likely because of lower power (13 events in subclinical hyperthyroidism instead of 34 over complete follow-up). The HR for AF events became statistically significant with inclusion of later events, and we found a time interaction for AF events (P value for interaction, .003): rates of AF became higher after 3 years and further increased with additional follow-up data.

All participants of the Birmingham Study and EPIC (European Prospective Investigation of Cancer)–Norfolk Study were excluded from these analyses because of lack of data on lipid-lowering and antihypertensive medications, as well as some participants from other cohorts.

All participants of the Birmingham Study were excluded from these analyses because of lack of data on BMI, as well as some participants from other cohorts.

The proportional hazard assumption was consistent across studies, except for the Birmingham Study6 (P = .009), which was excluded in a sensitivity analysis giving similar results. We found limited evidence of publication bias with visual assessment of age- and sex-adjusted funnel plots and the Egger test for total mortality (P = .17), but not the other outcomes (all P ≥ .20). For total mortality, the Brazilian Thyroid Study40 might be an outlier with no corresponding study of similar size with reduced risk associated with subclinical hyperthyroidism: a sensitivity analysis excluding this study yielded similar results.

COMMENT

In this analysis of all available prospective cohorts, endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism was associated with an increased risk of total mortality, CHD mortality, and incident AF. Coronary heart disease mortality and incident AF (but not other outcomes) were significantly greater in participants with thyrotropin levels lower than 0.10 mIU/L than those with thyrotropin levels between 0.10 and 0.44 mIU/L (for both, P value for trend, ≤.03). Risks did not differ significantly by age, sex, or preexisting CVD and were similar after further adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors.

Previous study-level meta-analyses produced conflicting results regarding the association between subclinical hyperthyroidism and cardiovascular mortality.15–17 Our results, based on individual participant data, demonstrate that there is indeed an increased risk of total and CHD mortality associated with subclinical hyperthyroidism,15,16 and add new information on subgroups at increased risk and the risk of incident AF. Previous meta-analyses could not accurately assess the differences in risk according to thyrotropin level, because of potential ecological fallacy without individual participant data analysis18 and they pooled individual studies using varying thyrotropin cutoff levels, outcome definitions, and confounding factors for adjustment.15,16 Only a few individual studies reported stratified risks according to thyrotropin levels. Our results are consistent with those recently reported by Vadiveloo et al,41 who found an increased risk of nonfatal CVD, increasing with lower thyrotropin levels (HR, 1.67 [95% CI, 1.45–1.92] for thyrotropin level 0.10–0.40 mIU/L, vs HR, 1.74 [95% CI, 1.36–2.21] for thyrotropin level <0.10 mIU/L); this study was not included in our analysis because of its retrospective case-control design.

To our knowledge, no meta-analysis has been conducted on the association of AF with subclinical hyperthyroidism. Similar to our data, some individual studies showed increased risk of AF associated with subclinical hyperthyroidism.9,10 Sawin et al9 reported an increased risk of incident AF in persons older than 60 years with thyrotropin levels lower than 0.1 mIU/L (HR, 3.8; 95% CI, 1.7–8.3) and among those with thyrotropin levels between 0.1 and 0.4 mIU/L (HR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.0–2.5); this study was excluded from our analysis because of its first-generation thyrotropin assay.26 Cappola et al10 showed a relationship between low thyrotropin levels and AF incidence in individuals 65 years or older with endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism, which was also significant in those with thyrotropin levels between 0.10 and 0.44 mIU/L (HR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.14–3.00). In a population with a mean age of 65.5 years, Vadiveloo et al41 found an increased risk of cardiac arrhythmia for participants with endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism, especially in those with thyrotropin levels lower than 0.10 mIU/L. Taken together, these previous studies and our data suggest that the risk of AF in individuals with endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism is higher with lower thyrotropin levels and is mostly pronounced in those with thyrotropin levels lower than 0.10 mIU/L.

The increased risks of AF events and total and CHD mortality associated with subclinical hyperthyroidism have been postulated to be caused by systemic effects of thyroid hormones, such as a change in cardiac function1,3 or cardiac arrhythmia.3,42 These hypotheses are favored by the fact that adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors did not alter risks of subclinical hyperthyroidism. An alternative explanation for the results could be publication bias, selection bias or quality issues in the included cohorts, or unmeasured confounders.43 Sensitivity analyses (1) excluding a small study40 with no corresponding study of similar size with reduced risk associated with subclinical hyperthyroidism and (2) pooling only higher-quality cohorts yielded similar results.

Among the strengths of our study, an individual participant data analysis is considered the best way for synthesizing evidence across several studies because it is not subject to potential bias from study-level meta-analyses (ecological fallacy)18 and allows performance of time-to-event analyses and use of standardized definitions of predictors, outcomes, and adjustment for confounding factors.19 We included all available international published data after conducting a systematic review.

Among the limitations of our study, our analysis included predominantly white populations, except for one cohort including Brazilians of Japanese descent.40 Although we included all available data, our results may not be generalized to all other populations. Second, thyroid function tests were performed only at baseline, and we have no data to assess how many participants with subclinical hyperthyroidism progressed to overt hyperthyroidism or normalized to euthyroidism over time, which is a limitation of most published large cohorts.10,23,27,38 Third, subclinical hyperthyroidism was defined as a thyrotropin level lower than 0.45 mIU/L and normal FT4 levels, since T3 was not measured in all included cohorts; sensitivity analyses excluding participants with abnormal total or free T3 levels yielded similar results. Fourth, the high prevalence of subclinical hyperthyroidism in the Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP, Northern Germany, 24.1%) may be explained by the iodine supplementation that was introduced in the area 4 years before the start of SHIP in the late 1990s.44 Excluding SHIP yielded similar risk estimates. Fifth, we did not have information on the etiology of subclinical hyperthyroidism, while cardiovascular complications may be related to the etiology of the condition.45 Sixth, up to 2.6% of participants started thyroxine or antithyroid drugs during follow-up; sensitivity analyses excluding users of these medications during follow-up yielded similar results. However, we did not have complete data from all cohorts on use of other medications that could alter thyrotropin and/or FT4 levels, such as steroids or amiodarone; sensitivity analyses excluding other medications users (0%–2.8% when available) yielded similar results. Seventh, only mortality and cardiovascular outcomes were assessed. Other conditions such as osteoporosis and cognition were not analyzed and could partly account for increased total mortality, particularly among elderly persons, although data on the associations between subclinical hyperthyroidism and osteoporosis and cognition are conflicting.1 Eighth, 4 of 6 studies7,8,10,38 formally adjudicated CHD outcomes. Sensitivity analyses limited to these 4 studies yielded similar risk estimates. As most included cohorts used self-reported preexisting CVD, stratified analyses according to preexisting CVD should be interpreted with caution.

Recent guidelines4 recommend that “treatment of SH [subclinical hyperthyroidism] should be strongly considered in all individuals ≥65 years of age” with thyrotropin level lower than 0.10 mIU/L (recommendation 65) and “treatment of SH should be considered in individuals ≥65 years of age” with low thyrotropin levels but 0.1 mIU/L or higher (recommendation 66). Based on all available prospective cohort studies, our findings of increased risks of total mortality, CHD mortality, and incident AF associated with subclinical hyperthyroidism, with greater risks of CHD mortality and AF among those with thyrotropin levels lower than 0.10 mIU/L, are consistent with these recent guidelines.4 However, findings based on observational data should be interpreted with great caution for clinical practice, since they are subject to several aforementioned limitations. No clinical trials have assessed whether treating subclinical hyperthyroidism results in improved cardiovascular outcomes. Because our data included only a limited sample of young men and premenopausal women, generalization of our findings to younger adults is limited.

In conclusion, pooling individual data from all available prospective cohorts suggests that endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism is associated with an increased risk of total mortality, CHD mortality, and incident AF, with higher risks of CHD mortality and AF with thyrotropin levels below 0.10 mIU/L. Our study is observational, and as such cannot address whether the risks associated with subclinical hyperthyroidism are lowered by treatment. A large randomized controlled trial with relevant clinical outcomes will be required to demonstrate whether these risks are altered by therapy; such a trial will be challenging to conduct given the large sample size required and the lower prevalence of adults with subclinical hyperthyroidism compared with subclinical hypothyroidism. If conducted, such a trial should examine prevention of AF and surrogate outcome measures, such as carotid intimamedia thickness.46

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by a grant SNSF 320030-138267 from the Swiss National Science Foundation (principal investigator, Dr Rodondi). The Cardiovascular Health Study and the research reported in this article were supported by contracts N01-HC-80007, N01-HC-85079 through N01-HC-85086, N01-HC-35129, N01 HC-15103, N01 HC-55222, N01-HC-75150, N01-HC-45133, and grant U01 HL080295 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Additional support was provided through grants R01 AG-15928, R01 AG-20098, AG-027058, and AG-032317 from the National Institute on Aging; grant R01 HL-075366 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the University of Pittsburgh Claude. D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center grant P30-AG-024827. The thyroid measurements in the Cardiovascular Health Study were supported by an American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid (to Linda Fried, MD). A full list of principal Cardiovascular Health Study investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.chs-nhlbi.org/pi.htm. The Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study was supported by National Institute on Aging (NIA) contracts N01-AG-6-2101, N01-AG-6-2103, N01-AG-6-2106; NIA grant R01-AG028050; and National Institute of Nursing Research grant R01-NR012459. The NIA funded the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study, reviewed the manuscript, and approved its publication. The EPIC-Norfolk study was supported by research grants from the Medical Research Council UK and Cancer Research UK. The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT Study) is a collaborative effort of HUNT Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology; Nord-Trøndelag County Council; Central Norway Health Authority; and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. The thyroid function testing in the HUNT Study was financially supported by Wallac Oy (Turku, Finland). The Leiden 85-Plus Study was partly funded by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sports. The Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP) is part of the Community Medicine Research net of the University of Greifswald, Germany, which is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, the Ministry of Cultural Affairs, as well as the Social Ministry of the Federal State of Mecklenburg–West Pomerania. Analyses were further supported by a grant of the German Research Foundation (DFG Vo 955/5-2). The Brazilian Thyroid Study was supported by an unrestricted grant from the Sao Paulo State Research Foundation (Fundacão de Amparo a’ Pesquisa do Estado de Sao Paulo, FAPESP, grant 6/59737-9 to Dr Maciel). Dr Newman is supported by grant AG-023629 from the NIA. Dr Westendorp is supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NGI/NWO 911-03-016).

Role of the Sponsor: None of the sponsors had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; except for the NIA, which funded the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study, reviewed the manuscript, and approved its publication.

Footnotes

Participating Studies of the Thyroid Studies Collaboration: United States: Cardiovascular Health Study; Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study; United Kingdom: Birmingham Study and EPIC-Norfolk Study; Norway: Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT Study); the Netherlands: Leiden 85-Plus Study; Italy: Pisa Cohort; Germany: Study of Health in Pomerania; Australia: Busselton Health Study; and Brazil: Brazilian Thyroid Study.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Online-Only Material: The eAppendix, eTable, and eFigure are available at http://www.archinternmed.com.

Author Contributions: Drs Collet and Rodondi had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Gussekloo, Newman, Westendorp, Franklyn, and Rodondi. Acquisition of data: Gussekloo, den Elzen, Iervasi, Åsvold, Sgarbi, Völzke, Gencer, Maciel, Molinaro, Luben, Newman, Khaw, Westendorp, Franklyn, Walsh, and Rodondi. Analysis and interpretation of data: Collet, Gussekloo, Bauer, den Elzen, Cappola, Balmer, Iervasi, Åsvold, Sgarbi, Völzke, Gencer, Maciel, Bremner, Maisonneuve, Cornuz, Westendorp, Franklyn, Vittinghoff, and Rodondi. Drafting of the manuscript: Collet, Balmer, Maciel, Westendorp, and Franklyn. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Collet, Gussekloo, Bauer, Cappola, Balmer, Iervasi, Åsvold, Sgarbi, Völzke, Gencer, Molinaro, Bremner, Luben, Maisonneuve, Cornuz, Newman, Khaw, Westendorp, Franklyn, Vittinghoff, Walsh, and Rodondi. Statistical analysis: Collet, Gussekloo, Balmer, Gencer, Franklyn, Vittinghoff, and Rodondi. Obtained funding: Sgarbi, Völzke, Maciel, Newman, Khaw, Westendorp, Walsh, and Rodondi. Administrative, technical, and material support: Collet, den Elzen, Gencer, Maciel, Luben, Newman, Khaw, Franklyn, and Rodondi. Study supervision: Gussekloo, Iervasi, Molinaro, Westendorp, and Rodondi. Dr Vittinghoff reviewed the statistical analyses of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Surks MI, Ortiz E, Daniels GH, et al. Subclinical thyroid disease: scientific review and guidelines for diagnosis and management. JAMA. 2004;291(2):228–238. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gharib H, Tuttle RM, Baskin HJ, Fish LH, Singer PA, McDermott MT. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction: a joint statement on management from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the American Thyroid Association, and the Endocrine Society. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(1):581–587. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biondi B, Cooper DS. The clinical significance of subclinical thyroid dysfunction. Endocr Rev. 2008;29(1):76–131. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahn RS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, et al. American Thyroid Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Thyroid. 2011;21(6):593–646. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biondi B. Endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism: who, when and why to treat. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2011;6(6):785–792. doi: 10.1586/eem.11.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parle JV, Maisonneuve P, Sheppard MC, Boyle P, Franklyn JA. Prediction of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in elderly people from one low serum thyrotropin result: a 10-year cohort study. Lancet. 2001;358(9285):861–865. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gussekloo J, van Exel E, de Craen AJ, Meinders AE, Frölich M, Westendorp RG. Thyroid status, disability and cognitive function, and survival in old age. JAMA. 2004;292(21):2591–2599. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.21.2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iervasi G, Molinaro S, Landi P, et al. Association between increased mortality and mild thyroid dysfunction in cardiac patients. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167 (14):1526–1532. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.14.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawin CT, Geller A, Wolf PA, et al. Low serum thyrotropin concentrations as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation in older persons. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(19):1249–1252. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411103311901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cappola AR, Fried LP, Arnold AM, et al. Thyroid status, cardiovascular risk, and mortality in older adults. JAMA. 2006;295(9):1033–1041. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Auer J, Scheibner P, Mische T, Langsteger W, Eber O, Eber B. Subclinical hyperthyroidism as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2001;142(5):838–842. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.119370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gammage MD, Parle JV, Holder RL, et al. Association between serum free thyroxine concentration and atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(9):928–934. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.9.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodondi N, Bauer DC, Cappola AR, et al. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction, cardiac function, and the risk of heart failure: the Cardiovascular Health study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(14):1152–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biondi B, Palmieri EA, Fazio S, et al. Endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism affects quality of life and cardiac morphology and function in young and middle-aged patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(12):4701–4705. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.12.7085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Völzke H, Schwahn C, Wallaschofski H, Dörr M. Review: the association of thyroid dysfunction with all-cause and circulatory mortality: is there a causal relationship? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(7):2421–2429. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ochs N, Auer R, Bauer DC, et al. Meta-analysis: subclinical thyroid dysfunction and the risk for coronary heart disease and mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(11):832–845. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-11-200806030-00225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haentjens P, Van Meerhaeghe A, Poppe K, Velkeniers B. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction and mortality: an estimate of relative and absolute excess all-cause mortality based on time-to-event data from cohort studies. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;159(3):329–341. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman D. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in Context. 2. London, England: BMJ Publishing Group; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simmonds MC, Higgins JP, Stewart LA, Tierney JF, Clarke MJ, Thompson SG. Meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomized trials: a review of methods used in practice. Clin Trials. 2005;2(3):209–217. doi: 10.1191/1740774505cn087oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodondi N, den Elzen WP, Bauer DC, et al. Thyroid Studies Collaboration. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of coronary heart disease and mortality. JAMA. 2010;304(12):1365–1374. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helfand M US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for subclinical thyroid dysfunction in nonpregnant adults: a summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(2):128–141. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-2-200401200-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walsh JP, Bremner AP, Bulsara MK, et al. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(21):2467–2472. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.21.2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boekholdt SM, Titan SM, Wiersinga WM, et al. Initial thyroid status and cardiovascular risk factors: the EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;72(3):404–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imaizumi M, Akahoshi M, Ichimaru S, et al. Risk for ischemic heart disease and all-cause mortality in subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(7):3365–3370. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanderpump MP, Tunbridge WM, French JM, et al. The development of ischemic heart disease in relation to autoimmune thyroid disease in a 20-year follow-up study of an English community. Thyroid. 1996;6(3):155–160. doi: 10.1089/thy.1996.6.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goichot B, Sapin R, Schlienger JL. Subclinical hyperthyroidism: considerations in defining the lower limit of the thyrotropin reference interval. Clin Chem. 2009;55(3):420–424. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.110627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Åsvold BO, Bjøro T, Nilsen TI, Gunnell D, Vatten LJ. Thyrotropin levels and risk of fatal coronary heart disease: the HUNT study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168 (8):855–860. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.8.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grundy SM Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riley RD, Lambert PC, Abo-Zaid G. Meta-analysis of individual participant data: rationale, conduct, and reporting. BMJ. 2010;340:c221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schafer JL. Multiple imputation: a primer. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8(1):3–15. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heinze G, Schemper M. A solution to the problem of monotone likelihood in Cox regression. Biometrics. 2001;57(1):114–119. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vittinghoff E, Glidden DV, Shiboski S, McCulloch CE. Regression Methods in Biostatistics: Linear, Logistic, Survival, and Repeated Measures Models. New York, NY: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schoenfeld D. Chi-squared goodness-of-fit tests for the proportional hazards regression model. Biometrika. 1980;67(1):145–153. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodondi N, Newman AB, Vittinghoff E, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of heart failure, other cardiovascular events, and death. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(21):2460–2466. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.21.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ittermann T, Haring R, Sauer S, et al. Decreased serum TSH levels are not associated with mortality in the adult northeast German population. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162(3):579–585. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sgarbi JA, Matsumura LK, Kasamatsu TS, Ferreira SR, Maciel RM. Subclinical thyroid dysfunctions are independent risk factors for mortality in a 7.5-year follow-up: the Japanese Brazilian Thyroid Study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162(3):569–577. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vadiveloo T, Donnan PT, Cochrane L, Leese GP. The Thyroid Epidemiology, Audit, and Research Study (TEARS): morbidity in patients with endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(5):1344–1351. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biondi B, Palmieri EA, Lombardi G, Fazio S. Effects of subclinical thyroid dysfunction on the heart. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):904–914. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-11-200212030-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. W64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Völzke H, Lüdemann J, Robinson DM, et al. The prevalence of undiagnosed thyroid disorders in a previously iodine-deficient area. Thyroid. 2003;13(8):803–810. doi: 10.1089/105072503768499680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biondi B, Kahaly GJ. Cardiovascular involvement in patients with different causes of hyperthyroidism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010;6(8):431–443. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor AJ, Villines TC, Stanek EJ, et al. Extended-release niacin or ezetimibe and carotid intimamedia thickness. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(22):2113–2122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]