Abstract

Familismo in the Latino culture is a value hallmarked by close relations with nuclear and extended family members throughout the life span, with pronounced levels of loyalty, reciprocity, and solidarity. Familismo is posited as health protective against alcohol misuse among Latinos in the United States. This study examines the relative influence of pre- and postimmigration familismo on alcohol use behaviors among recent Latino immigrants while accounting for myriad sociocultural factors (gender, age, documentation status, education, income, marital status, presence of family members in the United States, primary language used in the community, English language proficiency, and time in the United States). Participants included 405 young adults, aged 18 to 34 years, who were primarily of Cuban (50%), Columbian (19%), and Central American (15%) descent. Retrospective assessment of preimmigration familismo occurred during participants’ first 12 months in the United States. Follow-up assessment of alcohol use behaviors occurred during participants’ second year in the United States. Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes (MIMIC) path modeling was used to test study hypotheses. Inverse associations were determined between preimmigration familismo and alcohol use quantity and harmful/hazardous alcohol use. Men and participants who reported more proficiency in English, and those living in neighborhoods where English is predominantly spoken, indicated more alcohol use quantity and harmful/hazardous alcohol use. By considering both pre- and postimmigration determinants of alcohol use, findings offer a fuller contextual understanding of the lives of Latino young adult immigrants. Results support the importance of lifelong familismo as a buffer against alcohol misuse in young adulthood.

Keywords: Latino, young adults, immigration, alcohol, familismo

The Latino population, already the largest ethnic minority group in the United States, will triple in size by 2050 and will account for more than half of the nation's population growth between 2010 and 2050 (Ennis, Ríos-Vargas, & Albert, 2011). A major source of projected growth is immigration. Although demographers document the rapid growth of the U.S. Latino population, addiction researchers observe considerable health disparities affecting the U.S. Latino immigrant population (e.g., Grant et al., 2004). Compared with other U.S. ethnic groups, Latinos experience disparate negative consequences of drug and alcohol use, such as intimate partner violence, incarceration for alcohol-related offenses (e.g., driving under the influence), homelessness, HIV/AIDS, and cirrhosis mortality (Amaro, Arévalo, Gonzalez, Szapocznik, & Iguchi, 2006; Caetano, 2003). Hence, alcohol misuse among Latino young adults is an emergent public health concern (Chartier & Caetano, 2010; Lara, Gamboa, Kahramanian, Morales, & Bautista, 2005; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2009).

Familismo is a Latino cultural value that represents a sense of duty and responsibility toward one's family (Marsiglia, Parsai, Kulis, & The Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center, 2009; Updegraff, McHale, Whiteman, Thayer, & Delgado, 2005). The purpose of this study is to investigate a hypothesized link between the health protective cultural value of familismo and alcohol use behaviors among young adult Latino immigrants during their initial 2 years in the United States. The present study aims to improve our understanding of both pre- and postimmigration familismo. At present, the majority of studies on familismo focus on the postimmigration context (e.g., Hovey, 2000). Little is known about preimmigration levels of familismo that may help buffer problematic substance use after arrival to the United States. Information on preimmigration familismo can offer a fuller contextual understanding of the adaptation patterns and lives of Latino immigrants (Miranda, Estrada, & Firpo-Jimenez, 2000; Nee & Alba, 2004; Organista, Organista, & Kuraski, 2003). Such information can be utilized by alcohol use researchers and clinicians to better meet the needs of the growing Latino immigrant population in the United States (Drachman & Paulino, 2004).

Familismo

Family is fundamental to Latino culture (Cortés, 1995; Sabogal, Marín, Otero-Sabogal, VanOss Marín, & Perez-Stable, 1987). Familismo is characterized by (a) strong identification and attachment with nuclear and extended families, (b) strong family unity, interdependence among family members, and (c) high levels of social support (Gaines et al., 1997). Familismo is recognized as one of the most enduring and distinctive cultural characteristics for Latinos (Marín & Marín, 1991). Although the importance of family is found in many cultures (Schwartz, 2007), familismo in the Latino culture is particularly hallmarked by close relations with nuclear and extended family members throughout the life span, which feature pronounced levels of loyalty, reciprocity, and solidarity (Cauce et al., 2002; Marín & Gamba, 2003; Ramirez et al., 2004). For Latinos, la familia (the family) is recognized as a member's primary, if not sole, source of assistance, inspiration, and strength (Finch & Vega, 2003). The family protects its own against threats that can jeopardize the health, status, and honor of the family (Umberson, 1987). The family unit and its interests are valued above those of any individual member, a notion that encourages the concept of the family as an extension of the self (Cortés, 1995).

Familismo has been identified as a distinctive cultural protective factor against illicit drug use, alcohol misuse, and psychological distress among Latinos living in the United States (Gallo, Penedo, Espinosa de los Monteros, & Arguelles, 2009; Gil, Wagner, & Vega, 2000; Mulvaney-Day, Alegría, & Sribney, 2007; Ramirez et al., 2004; Rivera et al., 2008; Warner et al., 2006). Much of the literature on familismo among U.S. Latinos has examined it within the concept of acculturation—broadly defined (in terms of immigration) as a process of change following immigration, as immigrants adjust to their new environment and reconcile their heritage/cultural practices, values, and identifications with those of the receiving society (Berry, 1997). The acculturation process and accompanying stress is posited to erode components of familismo, thereby limiting the protective nature of familismo and the resiliency it provides against health risk behaviors (Marsiglia et al., 2009; Miranda et al., 2000; Myers & Rodriguez, 2003). Although research on the effects of the acculturation process on Latino families in the United States has yielded critical information, researchers have called for more studies to determine how culture-specific beliefs and practices (e.g., familismo) may impact health risk behaviors (Gallo et al., 2009). Unlike previous studies, this study focuses on the influence of both pre- and postimmigration familismo and other sociocultural determinants on drinking behaviors of Latino young adult immigrants who resided in the United States for less than 2 years.

The Present Study

Our research questions were guided by Bogenschneider's (1996) ecological risk/protective model and Bronfenbrenner's (1986) ecological theory of human development. Similar to the concept of the Latino cultural value of familismo, the ecological perspective suggests that the family represents the primary context for human development over the life span (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999). Relations with parents and other family members play major roles in shaping patterns of life span development. Family dynamics extend well beyond childhood and adolescence, such that family influences continue to be important in adulthood (Overbeek, Stattin, Vermulst, Ha, & Engels, 2007). This may be especially true for Latinos, for whom familial bonds remain extremely important throughout the life span, and for whom these bonds are generally influential against drug and alcohol misuse. In addition, the ecological perspective is inclusive of sociocultural factors posited to affect familismo and alcohol use behaviors (e.g., neighborhood factors, immigration status, socioeconomic influences; Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010).

The present study aims to determine whether (and how) participants’ pre- and postimmigration levels of familismo are associated with alcohol use frequency, quantity, and harmful/hazardous use during participants’ second year in the United States. Relations between familismo and alcohol use behaviors are examined while accounting for salient sociocultural determinants established in previously cited literature (gender, age, documentation status, education, income, marital status, presence of family members in the United States, primary language in the community, English language proficiency, and time in the United States). Based on documented associations between postimmigration familismo and substance use behaviors in previously cited research, higher levels of pre- and postimmigration familismo are hypothesized to be health protective against alcohol misuse.

Method

Procedure

The present study was conducted using baseline and first follow-up assessment data from a longitudinal investigation of sociocultural determinants of health among young adult Latino immigrants living in Miami-Dade County, Florida. The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of a large university in Miami. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health to insure maximum protection for the participants of the study. Inclusion criteria for participation in the study included (a) self-identifying as a Latino/a, (b) being 18 to 34 years old, (c) having recently immigrated (i.e., within 1 year prior to the baseline assessment) to the United States from a Latin American country, and (c) intending to stay in the United States for least 3 years.

Consenting procedures and baseline assessment interviews were conducted in Spanish during participants’ first year in the United States (M = 6.74 months in United States, SD = 3.11). Follow-up assessment interviews were conducted approximately 12 months after the initial baseline interview during participants’ second year in the United States (M = 19.95 months in United States, SD = 3.19). Participant interviews were conducted in Spanish by eight bilingual Latino interviewers who were of South American or Caribbean origin and held college degrees (four undergraduate and four graduate degrees). Interviewers ranged from 23 to 48 years of age (M = 33.38, SD = 7.23).

Participants were recruited through respondent-driven sampling (RDS). RDS has been shown to be an effective strategy for recruiting participants from hidden or difficult-to-reach populations such as recent immigrants (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004). Undocumented Latino immigrants are a hidden population due to the sensitivity of their legal status in the United States. Thus, RDS was considered an optimal sampling approach to ensure feasibility of the study. The RDS approach involved asking each recruited participant (the seed) to refer three other individuals in his or her social network who met the eligibility criteria for the study and consented to be interviewed. Those participants were then asked to refer three other individuals. The procedure was followed for seven legs for each initial participant (seed), at which point a new seed would begin, to limit the number of participants that were socially interconnected (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004).

Seed participants were recruited through announcements posted at community-based agencies providing services to refugees, asylum seekers, and other documented and undocumented Latino immigrants in Miami. Information also was disseminated at Latino community health centers and neighborhood boards such as craigslist.org activity locales (e.g., domino parks in the Little Havana section of Miami). Additionally, announcements were posted around Latino communities and on an electronic bulletin and an employment Web site that Latinos access to search for work in Miami-Dade County.

Participants

Five hundred and twenty-seven Latino adults enrolled in the study at baseline assessment (occurring during their first 12 months in the United States). Four hundred and five participants were retained for follow-up assessment (77% retention rate), which occurred approximately 12 months after participants’ baseline assessment. Data from retained participants (n = 405) were analyzed to test study hypotheses.

The sample of 405 participants was 51% female and 49% male. The average age was 28.53 years (SD = 4.91, range of 19 to 36 years). Participants included Latino immigrants from Cuba (50%), Colombia (19%), Honduras (8%), and Nicaragua (7%). Venezuelans comprised the next largest subgroup at 3% of the sample. Participants from other Caribbean and South and Central American countries comprised 2% or less of the sample. Approximately 77% of participants had legally immigrated, whereas the remaining 23% arrived to the United States without documentation. Twenty-one percent of participants had college degrees, 38% had attended some college, 27% had a high school or equivalent degree, and 14% had not completed high school. The sample also consisted of low-income participants. The median total annual household income was $21,604 (unadjusted for dependents) for the 12 months prior to follow-up assessment.

To assess for sampling bias introduced by attrition, we tested whether retained participants differed from nonretained participants on key preimmigration demographic variables (immigration status at arrival to United States, gender, annual income, education level) and preimmigration familismo. A larger number of nonretained participants were undocumented upon arrival to United States (42.5% nonretained, undocumented participants vs. 14.3% nonretained, documented participants), χ2(1, N = 527) = 49.86, p < .001, η2 = .10. Nonretained participants also tended to be men, χ2(1, N = 527) = 25.47, p < .001, η2 = .05, and reported lower educational attainment, F(1, 526) = 27.25, p < .001, η2 = .05. Finally, nonretained participants also reported lower preimmigration familismo scores, F(1, 527) = 12.98, p < .001, η2 = .02.

Measures

Study measures were either validated in Spanish in past research, or were translated into Spanish for the present study. English versions of each measure went through a process of (a) translation/back translation, (b) modified direct translation, (c) and checks for semantic and conceptual equivalence to ensure accurate conversion from English to Spanish (Behling & Law, 2000). For the modified direct translation, a review panel, consisting of individuals from various Latino subgroups that are representative of the Miami-Dade County population, was employed to account for potential within-Latino-group variability.

Sociocultural Variables

A demographics form was administered to participants at baseline and follow-up assessments. The form assessed participants’ gender (dummy coded 0 = women, 1 = male); age (in years); marital status (0 = nonmarried/partnered, 1 = married/partnered); country of origin; length of time in the United States (in months); education level (1 = less than high school, 2 = high school, 3 = some training/college after high school, 4 = bachelor's degree, 5 = graduate/professional studies), and average annual household income. Annual household income was adjusted by dividing the number of dependent persons in a participant's household to arrive at a more accurate assessment of income.

Primary language used in neighborhood

At follow-up assessment, the primary language used by neighbors in participants’ postimmigration residential community was documented by a single item rated on a 5-point Likert scale response format (1 = only English to 5 = only Spanish).

English language proficiency

Participants’ English language proficiency was assessed by an item asking, “How well do you speak English?” at follow-up assessment, which participants rated on a 5-point Likert scale response format (1 = don't speak/understand to 5 = speak it very well).

Family present in the United States

At follow-up assessment, participants were asked (a) whether family members had immigrated with them to the United States, (b) whether they had any family members in the United States prior to immigrating, and (c) whether any family members joined them in the United States after they immigrated here. To create a single item documenting family member presence, responses across these items were coded “0” if family member(s) were not present in the United States and “1” if family member(s) had immigrated or resided in the United States before or after participants’ immigration.

Immigration status in the United States

Participants reported their immigration status in the United States at baseline assessment via a total of 14 categories, including temporary or permanent resident; tourist, student, and temporary work visa; undocumented; and expired visa, asylum, and temporary protected immigrant. To facilitate analyses, categories were recoded into a dichotomous variable indicating documented (1) or undocumented (0) immigration status.

Familismo

The Family Cohesion and Disengagement subscales from the Family Functioning Scale (FFS; Bloom, 1985) were selected to retrospectively assess pre- and postimmigration familismo. These two subscales facilitated the assessment of contrasting dimensions of family cohesion to approximate familismo. When responding to items at baseline assessment, participants were instructed to consider their relationship with their family throughout their lifetime before coming to the United States. At follow-up assessment, participants were asked to only rate their relationship with their family during the 12-month time period before their assessment (i.e., during their second year in the United States).

The Family Cohesion and Disengagement subscales have evidenced acceptable psychometric properties (Bloom, 1985; Grotevant & Carlson, 1989). In the present study, adequate internal consistency was evidenced by Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.79 (baseline) and 0.82 (follow-up) for the Family Cohesion subscale, and 0.66 (baseline) and 0.65 (follow-up) for the Family Disengagement subscale. Each subscale contains five items, and uses a 4-point Likert scale response format (1 = very untrue to 4 = very true). Sample items include We really get along well with each other (Cohesion) and Family members do not check with each other when making decisions (Disengagement). Subscale scores were computed by calculating the average of subscale items. Overall pre- and postimmigration familismo scores were calculated by subtracting Family Disengagement from Cohesion scores for each time point.

Alcohol Use Frequency and Quantity

The Timeline Followback Interview (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992) was administered to participants to document frequency and quantity of alcohol use during the 90 days prior to their follow-up assessment. TLFB data are collected using a calendar format to provide temporal cues (e.g., holidays, special occasions) to assist in recall of days when alcohol was used. A Spanish version of the TLFB was used, which has been suggested as a reliable and valid measure with Latino populations (Dillon, Turner, Robbins, & Szapocznik, 2005; Gil, Wagner, & Tubman, 2004). Frequency of alcohol use was indicated by the total number of days that alcohol was used during pre- and postimmigration, 90-day assessment periods. Quantity of alcohol use was measured by computing the average number of drinks consumed on drinking days within the 90-day assessment periods.

Harmful/Hazardous Alcohol Use

A psychometrically supported, Spanish version of The Alcohol Use Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor, Biddle-Higgins, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001) was administered to participants to screen for problems related to alcohol consumption, abuse, and dependence during the 12 months prior to their follow-up assessment. AUDIT total scores were calculated by summing all 10 items, with higher total scores indicating more harmful/hazardous alcohol use. The AUDIT indicated acceptable evidence of internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.77.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses proceeded in two steps. First, frequency distributions were calculated for all continuous variables to determine if they violated the assumption of univariate normality (i.e., skewness indices ≥3, kurtosis indices ≥10; Chou & Bentler, 1995; Kline, 2005). We also calculated descriptive statistics for, and bivariate correlations among, all constructs (i.e., Pearson for continuous and Spearman for ordinal and dummy-coded nominal variables). We examined correlation coefficients between all predictor variables included in the final analysis for evidence of discriminant validity between constructs (i.e., correlation coefficient values <0.70; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007).

Second, we tested whether pre- and postimmigration levels of familismo are inversely associated with postimmigration alcohol use behaviors. We used Mplus statistical software (Muthén and Muthén, 2010) to regress frequency of alcohol use, quantity of alcohol use, and harmful/hazardous alcohol use on pre- and postimmigration familismo in a single path model. We used Multiple Indicators, Multiple Causes (MIMIC; Bollen, 1989) modeling to include salient social and cultural variables as covariates in the structural model (i.e., gender, age, documentation status, education, income, marital status, presence of family members in the United States, primary language in community, English language proficiency, and time in the United States). Specifically, the MIMIC model involved regressing frequency of alcohol use, quantity of alcohol use, harmful/hazardous alcohol use, as well as pre- and postimmigration familismo on each covariate. Correlations between all covariates also were included in the MIMIC model.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 lists descriptive statistics for, and bivariate correlations among, all variables in the study. Correlation coefficient values for relations between all predictors and covariates of alcohol use behaviors in the path model were less than 0.70. Frequency of alcohol use and quantity of alcohol use variables were positively skewed. Both variables were transformed using a square root data transformation to arrive at an approximately normal distribution for analyses.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among Observed Variables

| Variable | M or % | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. AUDIT | 4.23 | 4.72 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Frequency of alcohol use | 8.14 | 12.93 | 0.71** | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Quantity of alcohol use | 3.21 | 4.74 | 0.74** | 0.71** | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Preimmigration Familismo | 1.58 | 0.99 | –0.15** | –0.01 | –0.09 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 5. Postimmigration Familismo | 1.41 | 0.92 | –0.13** | 0.02 | –0.04 | 0.41** | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 6. Gendera | 49% men 51% women | n/a | 0.29** | 0.25** | 0.31** | 0.05 | –0.02 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 7. Age | 28.53 | 4.91 | –0.03 | –0.02 | –0.04 | –0.06 | –0.11* | 0.01 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 8. Immigration status | 78% documented; 22% undocumented | n/a | 0.02 | 0.11* | 0.03 | 0.17** | 0.31** | –0.10* | –0.20** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 9. Education statusc | 2.63 | 0.97 | –0.01 | 0.12* | 0.05 | 0.11* | 0.22** | –0.03 | 0.10* | 0.29** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 10. Annual household income/# dependents | $8836 | $8884 | 0.04 | –0.01 | –0.01 | 0.04 | –0.02 | 0.02 | –0.13** | 0.01 | –0.09 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 11. Marital statusd | 43% married; 57% not married | n/a | –0.07 | –0.07 | –0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 | –0.07 | 0.25** | 0.02 | 0.02 | –0.06 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 12. Family members in United States before immigration?e | 13% no; 87% yes | n/a | –0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.12* | 0.02 | 0.02 | –0.17** | 0.19** | –0.03 | 0.10* | –0.09 | 1.00 | |||||

| 13. Immigration with family members?e | 61% no; 39% yes | n/a | –0.10* | –0.05 | –0.08 | 0.14** | 0.13* | –0.28** | –0.07 | 0.23** | 0.06 | –0.05 | 0.08 | 0.10* | 1.00 | ||||

| 14. Family members arrived to United States after Immigration?e | 86% no; 14% yes | n/a | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.04 | –0.04 | –0.02 | –0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.11* | –0.05 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 1.00 | |||

| 15. Presence of family in United States?e | 12% no; 88% yes | n/a | –0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.14** | 0.13* | –0.01 | –0.17** | 0.22** | 0.01 | 0.14** | –0.08 | 0.94** | 0.09 | 0.15** | 1.00 | ||

| 16. Primary language used in neighborhoodf | 4.26 | 0.89 | –0.15** | –0.13* | –0.08 | 0.07 | –0.05 | –0.01 | 0.12* | –0.11* | –0.26** | 0.08 | 0.05 | –0.04 | –0.03 | –0.03 | –0.05 | 1.00 | |

| 17. English language proficiencyg | 1.97 | 0.81 | 0.09 | 0.18** | 0.11* | 0.08 | 0.18** | –0.05 | –0.17** | 0.29** | 0.34** | 0.01 | –0.11* | 0.10* | 0.16** | 0.04 | 0.09 | –0.38** | 1.00 |

| 18. Time in United States (months) | 19.95 | 3.19 | 0.03 | –0.01 | –0.02 | 0.01 | –0.03 | 0.01 | –0.02 | –0.06 | –0.01 | –0.02 | 0.04 | –0.02 | –0.15** | 0.03 | –0.02 | –0.05 | –0.01 |

0 = female; 1 = male.

0 = undocumented, 1 = documented.

l = less than high school; 2 = high school; 3 = some training/college after high school; 4 = bachelor's degree; 5 = graduate/professional studies.

0 = not married/not partnered; 1 = married/partnered.

0 = no; 1 = yes.

1 = only English to 5 = only Spanish.

1 = don't speak/understand to 5 = speak it very well.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Path Model

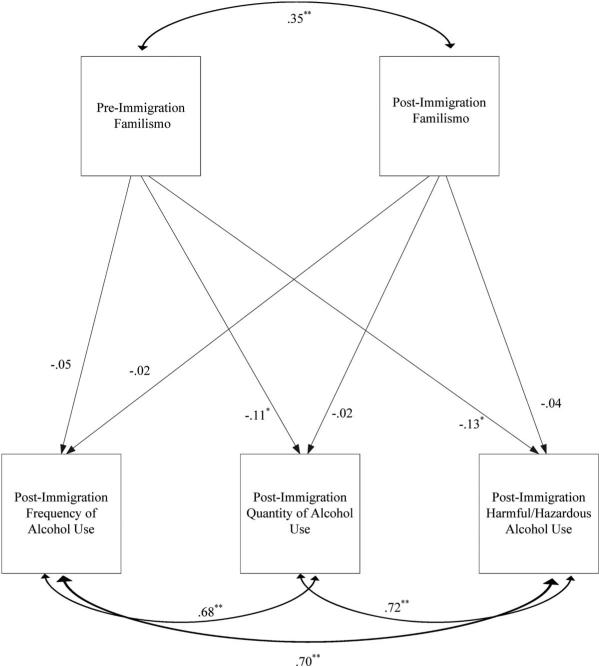

Next, we estimated the path model to evaluate hypothesized relations. Directional paths were drawn from the pre- and postimmigration familismo to the frequency, quantity, and harmful/hazardous alcohol use constructs (see Figure 1). Paths also were included between covariates and hypothesized predictor and dependent variables. To facilitate presentation of main effects, these paths are not pictured in Figure 1 but results are summarized below. Because all parameters in the MIMIC model are estimated, the path model fit was just-identified (a model with zero degrees of freedom) and therefore has noninterpretable model fit indices. Main and covariate effects are summarized next.

Figure 1.

Path model of pre- and postimmigration familismo and alcohol use behaviors. To facilitate presentation of main effects, covariate paths are not pictured in the model but results are summarized in text. Note. * p < .05. ** p < .01.

Main and Covariate Effects on Alcohol Use

Frequency of alcohol use

Neither pre- nor postimmigration familismo was related to frequency of alcohol use at follow-up assessment. Men (β = .25, p < .001) and participants who indicated more English language proficiency (β = .14, p = .01) reported more days of alcohol use. Eleven percent of variability in frequency of use was explained by the path model.

Quantity of alcohol use

Higher levels of preimmigration familismo were negatively related to quantity of alcohol use at follow-up assessment (β = –.11, p < .05). Postimmigration familismo was not related with quantity of alcohol use. Men (β = .31, p < .001) reported more quantity of alcohol use then women. Twelve percent of variability in quantity of use was explained by the path model.

Harmful/Hazardous alcohol use

Higher levels of preimmigration familismo were negatively related to harmful/hazardous alcohol use at follow-up assessment (β = –.13, p < .05). Postimmigration familismo was not related with harmful/hazardous alcohol use. Males (β = .21, p < .001) and participants who lived in neighborhoods in which English is predominantly spoken (β = –.13, p = 02) reported more harmful/hazardous use. Eleven percent of variability in harmful/hazardous use was explained by the path model.

Covariate Effects on Pre- and Postimmigration Familismo

Undocumented participants reported less pre- (β = .13, p = .01) and postimmigration familismo (β = .16, p < .01). Participants who had family in the United States indicated higher levels of pre- (β = .12, p = .02) and postimmigration familismo (β = .13, p = .02). Finally, participants with higher educational attainment reported more pre- (β = .16, p < .01) and postimmigration familismo (β = .17, p < .01).

Correlations Between Covariates

As indicated in Table 1, significant bivariate relations were found between several covariates. These associations were reflected in the MIMIC path model. Men tended to report undocumented legal status more often than women (r = –.10, p < .05), and men immigrated with family less often than women (r = –.28, p < .001). Undocumented participants tended to be less educated (r = .28, p < .001), older (r = –.20, p < .001), reported less proficiency in English (r = .28, p < .001), and immigrated less often with family than documented participants (r = .23, p < .001). Lower educational attainment was related to less English language proficiency (r = .34, p < .001) and a greater tendency to live in predominantly Spanish-speaking neighborhoods (r = –.26, p < .001). Younger participants reported higher incomes (r = –.13, p < .01) and more English language proficiency (r = –.17, p < .001); older participants were married/partnered (r = .26, p < .001) and lived in predominantly Spanish-speaking neighborhoods (r = .12, p < .05). Married/partnered participants also were less proficient in Spanish (r = –.11, p < .05). As expected, participants with less English language proficiency resided in predominantly Spanish-speaking neighborhoods (r = –.38, p < .001) and immigrated less often with family (r = .16, p < .01) than more proficient participants.

Discussion

Latinos in the United States experience disparate negative consequences resulting from alcohol use disorders (Alegría, Canino, & Stinson, 2006). Latinos also are the largest minority group in the United States, accounting for approximately 16% of the population (Passel & Cohn, 2011). Approximately 37% of the U.S. Latino population is foreign-born. Improved understanding of alcohol use and its correlates among newly arrived Latino immigrants inform alcohol treatment services in regard to this rapidly growing population experiencing alcohol-related health disparities in the United States. The present study sampled recent Latino young adult immigrants and explored whether their levels of pre- and postimmigration familismo were linked with alcohol use behaviors during their second year in the United States. Higher levels of the protective health value of familismo were hypothesized to be associated with less alcohol misuse while accounting for salient sociocultural influences.

Our findings indicate that higher levels of preimmigration familismo are linked with lower levels of hazardous alcohol use soon after immigration. These findings are consistent with the Bogenschneider (1996) ecological risk/protective theoretical framework and Bronfenbrenner's (1986) ecological theory of human development. In these ecological models, the family represents the primary context for human development over the life span (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999). Consistent with these theories, familismo over the life span appears foremost in protecting Latino young adults from alcohol misuse during the initial years after immigration.

Contrary to expectations, postimmigration familismo did not relate to alcohol use behaviors. The likely change in level of contact with family from country of origin after immigration may have diminished the proximate protective effects of familismo. In our sample, 61% of participants left their family in their country of origin, although approximately 14% reported a family member later joined participants in United States soon after immigration. Participants without any family with them in the United States, most of whom were undocumented and had less educational attainment, reported markedly lower levels of postimmigration familismo. However, family member presence in United States did not directly relate with alcohol use behaviors. Thus, future research with recent Latino immigrants should attempt to determine the potential indirect risk of separation from family on substance misuse over time (Mitrani, Santisteban, & Muir, 2004).

The differential influence of preimmigration familismo (over the lifetime) versus postimmigration familismo (over 1-year postimmigration) on alcohol use behaviors could be explained by the theorized difference between attitudinal familismo (feelings of loyalty, reciprocity, and solidarity) and behavioral familismo (behaviors associated with feelings of familismo such as living with or in close proximity, tangibly helping family members, celebrating life events with family, and regular meals/get-togethers with family; Comeau, 2012; Marín, 1993; Sabogal et al., 1987). Opportunities for expressions of behavioral familismo may have been more limited, due to separation from family after immigration, in comparison with the more stable construct of attitudinal familismo (Villarreal, Blozis, & Widaman, 2005). Protective components of behavioral familismo may have been greatly limited or absent in participants’ postimmigration lives in comparison with their preimmigration contexts. Hence, only preimmigration familismo yielded a significant link with alcohol use. Future studies on alcohol use behavior of recent Latino immigrants should account for multiple dimensions of familismo to yield a more comprehensive understanding of the protective properties of familismo before and after immigration (Comeau, 2012).

In addition to familismo, several noteworthy sociocultural factors were found to relate postimmigration alcohol use behaviors. Men in the sample consistently drank more than women. Women generally report lower rates of alcohol use in the United States, and this trend is especially apparent in the Latino/a community (Alvarez, Jason, Olson, Ferrari, & Davis, 2007; Canino & Alegría, 2008). Consistent with the acculturation literature, (a) participants who lived in neighborhoods in which English is predominantly spoken by neighbors, and (b) participants who are more proficient in English reported more harmful/hazardous alcohol use and more frequent use, respectively. Participants who were more proficient in the English language and used it more often in their neighborhood may have been more acculturated to the U.S. culture. Higher levels of acculturation, even among recent Latino immigrants, may have made them more likely to engage in harmful/hazardous alcohol use in comparison with their less acculturated counterparts (Canino & Alegría, 2008; Epstein, Botvin, & Diaz, 2001; Finch, Boardman, Kolody, & Vega, 2000; Marsiglia & Waller, 2002). Future research should consider potential factors associated with discrepant acculturation rates among Latino immigrants arriving in the United States at comparable times, such as the cultural heterogeneity of one's receiving community (Schwartz et al., 2010).

Limitations

The present findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. The first limitation is the use of respondent driven sampling. Although respondent driven sampling has been successful in recruiting hidden populations such as undocumented immigrants, who constitute approximately 22% of the U.S. Latino population (Passel & Cohn, 2011), it does not ensure representative sampling. Second, although efforts were undertaken to include participants from major Latino subgroups, some groups (e.g., Mexican American) were not well represented due to their under-representation in the Miami-Dade County area in general. Latino subgroups in Miami-Dade County constituted 65% of the total county population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Percentages of the Latino subgroups and regions of origin in Miami-Dade County are estimated as Cuban (34.3%), South American (11%), Central American (8.5%), Puerto Rican (3.7%), Dominican (2.3%), and Mexican (2.1%). Thus, the current sample was representative of Latinos living in Miami-Dade County but not the larger United States. Future studies are needed with nationally representative samples of Latino immigrants to enhance the generalizability of present results. Additionally, differential attrition rates based on documentation status, gender, educational attainment levels, and preimmigration familismo may limit the external validity of findings. Furthermore, the participant retention rate of the study was 77%. Although this retention rate is above the rate (70%) generally accepted as adequate by social and behavioral scientists (McLellan, Grissom, Zanis, & Randall, 1997), the loss of 23% of the sample to attrition may have impacted the results because nonretained participants tended to be undocumented men with lower educational attainment and lower preimmigration familismo.

Clinical Implications

Findings concerning links between preimmigration familismo and alcohol misuse have important implications for clinicians who work with recent Latino immigrants, as well as for clinical researchers interested in promoting health protective Latino cultural values to eliminate alcohol-related health disparities. As the number of Latino immigrants residing in the United States grows, the need to assist immigrants in making healthy transitions into U.S. society soon after their arrival is increasingly imperative (Hernandez, Denton, & Macartney, 2008). Clinicians are encouraged to monitor and discuss pre- and postimmigration levels of familismo to better assess and understand its protective influence on alcohol misuse among recent Latino immigrant adults. Our findings also provide clinicians with sociocultural markers (e.g., gender, English language proficiency and use in community) to continue to attend to when working with recent Latino young adult immigrants.

Clinicians also should consider working beyond the patient–provider relationship to assess and address potential determinants of alcohol misuse in clients’ lives. Community-based interventions should be considered to address and promote the importance of familismo and other potential sociocultural buffers against alcohol misuse. Such interventions may be more culturally adaptive and may exert a greater therapeutic or preventive influence than traditional prevention and treatment approaches (Gragg & Wilson, 2011; Paynter & Estrada, 2009). For instance, to promote awareness of familismo and its impact on alcohol misuse, clinicians can serve as a trainer or consultant to provide technical assistance to local organizations and agencies (e.g., community health centers, state and county departments of health). These efforts may include collaborating on outreach events, giving talks about research that have application at the community level, and conducting literature reviews to communicate the importance of familismo and other potentially protective cultural values (Buki, Jamison, Anderson, & Cuadra, 2007; Tucker & Herman, 2007). Finally, like the present study, future clinical research and interventions should consider pre- and postimmigration sociocultural determinants that are likely to impact immigrants’ differential responses to the immigration process and its inherent challenges and impacts on substance misuse.

Overall, this study contributes to the limited knowledge on pre- and postimmigration familismo and other sociocultural determinants of alcohol misuse just after arrival to the United States. Future clinical research concerning other Latino cultural values may provide valuable information to clinicians concerning competent care of recent Latino immigrants. Such research is of critical importance, as it will inform efforts to address alcohol misuse and related negative health outcomes among various subgroups of the largest and fastest growing ethnic minority group in the United States.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by award number P20MD002288 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

CITATION

Dillon, F. R., De La Rosa, M., Sastre, F., & Ibañez, G. (2012, December 31). Alcohol Misuse Among Recent Latino Immigrants: The Protective Role of Preimmigration Familismo. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a0031091

Contributor Information

Frank R. Dillon, School of Social Work, Center for Substance Use and HIV/AIDS Research on Latinos in the United States (C-SALUD), Florida International University, Coral Gables, Florida.

Mario De La Rosa, School of Social Work, Center for Substance Use and HIV/AIDS Research on Latinos in the United States (C-SALUD), Florida International University, Coral Gables, Florida..

Francisco Sastre, School of Social Work, Center for Substance Use and HIV/AIDS Research on Latinos in the United States (C-SALUD), Florida International University, Coral Gables, Florida..

Gladys Ibañez, Behavioral Science Research Institute, Coral Gables, Florida..

References

- Alegría M, Canino G, Stinson FS. Nativity and DSM–IV psychiatric disorders among Puerto Ricans, Cuban Americans, and Non-Latino whites in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67:56–65. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0109. doi:10.4088/JCP.v67n0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez J, Jason LA, Olson BD, Ferrari JR, Davis MI. Substance abuse prevalence and treatment among Latinos and Latinas. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2007;6:115–141. doi: 10.1300/J233v06n02_08. doi:10.1300/J233v06n02_08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H, Arévalo S, Gonzalez G, Szapocznik J, Iguchi MY. Needs and scientific opportunities for research on substance abuse treatment among Hispanic adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;84:S64–S75. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.008. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Biddle-Higgins JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary health care. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Behling O, Law KS. Translating questionnaires and other research instruments: Problems and solutions. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 1997;46:5–34. doi:10.1080/026999497378467. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom BL. A factor analysis of self-report measures of family functioning. Family Process. 1985;24:225–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1985.00225.x. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.1985.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogenschneider K. An ecological risk/protective theory for building prevention programs, policies, and community capacity to support youth. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 1996;45:127–138. doi:10.2307/585283. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. John Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:723–742. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723. [Google Scholar]

- Buki LP, Jamison J, Anderson CJ, Cuadra AM. Differences in predictors of cervical and breast cancer screening by screening need in uninsured Latino women. Cancer. 2007;110:1578–1585. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22929. doi:10.1002/cncr.22929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R. Alcohol-related health disparities and treatment-related epidemiological findings among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics in the United States. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1337–1339. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080342.05229.86. doi:10.1097/01.ALC.0000080342.05229.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, Alegría M. Psychiatric diagnosis – is it universal or relative to culture? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:237–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01854.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01854.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodríguez M, Paradise M, Cochran BN, Shea JM, Srebnik D, Baydar N. Cultural and contextual influences in mental health help seeking: A focus on ethnic minority youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:44–55. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.44. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.70.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier K, Caetano R. Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Research & Health. 2010;33:152–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou CP, Bentler PM. Estimates and tests in structural equation modeling. In: Chou CP, Bentler PM, Hoyle RH, editors. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Comeau JA. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. Advance online publication; 2012. Race/ethnicity and family contact: Toward a behavioral measure of familialism. doi:10.1177/0739986311435899. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés DE. Variations in familism in two generations of Puerto Ricans. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17:249–255. doi:10.1177/07399863950172008. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon FR, Turner CW, Robbins MS, Szapocznik J. Concordance among biological, interview, and self-report measures of drug use among African American and Hispanic adolescents referred for drug abuse treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:404–413. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.404. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drachman D, Paulino A. Thinking beyond the United States borders. Journal of Immigration and Refugee Services. 2004;29:1–9. doi:10.1300/J191v02n01_01. [Google Scholar]

- Ennis SR, Ríos-Vargas M, Albert NG. The Hispanic population. U. S. Department of Commerce, Economics, and Statistics Administration, U. S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2011. p. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JA, Botvin GJ, Diaz T. Linguistic acculturation associated with higher marijuana and polydrug use among Hispanic adolescents. Substance Use & Misuse. 2001;36:477–499. doi: 10.1081/ja-100102638. doi:10.1081/JA-100102638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Boardman JD, Kolody B, Vega WA. Contextual effects of acculturation on perinatal substance exposure among immigrant and native-born Latinas. Social Science Quarterly. 2000;81:421–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Vega WA. Acculturation stress, social support and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2003;5:109–117. doi: 10.1023/a:1023987717921. doi:10.1023/A:1023987717921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaines SO, Jr., Marelich WD, Bledsoe KL, Steers WN, Henderson MC, Granrose CS, Page MS. Links between race/ethnicity and cultural values as mediated by racial/ethnic identity and moderated by gender. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:1460–1476. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.6.1460. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.6.1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Penedo FJ, Espinos de los Monteros K, Arguelles W. Resiliency in the face of disadvantage: Do Hispanic cultural characteristics protect health outcomes? Journal of Personality. 2009;77:1707–1746. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00598.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, Tubman J. Culturally sensitive substance abuse intervention for Hispanic and African American adolescents: Empirical examples from the Alcohol Treatment Targeting Adolescents in Need (ATTAIN) Project. Addiction. 2004;99:140–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00861.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, Vega WA. Acculturation, familism, and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: Longitudinal relations. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:443–458. doi:10.1002/1520-6629(200007)28:4<443::AID-JCOP6>3.0.CO;2-A. [Google Scholar]

- Gragg BJ, Wilson CM. Mexican American family's perceptions of the multirelational influences on their adolescent's engagement in substance use treatment. The Family Journal. 2011;19:299–306. doi:10.1177/1066480711405822. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, Dawson DA, Chou P, Anderson K. Immigration and lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans and Non-Hispanic Whites in the United States. Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:1226–1233. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.12.1226. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.61.12.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD, Carlson CI. Family assessment: A Guide to methods and measures. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez DJ, Denton NA, Macartney S. Children in immigrant families: Looking to America's future. Social Policy Report. 2008;22:3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hovey JD. Psychosocial predictors of acculturative stress in Mexican immigrants. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied. 2000;134:490–502. doi: 10.1080/00223980009598231. doi:10.1080/00223980009598231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Bautista DEH. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: A Review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín G. Influence of acculturation on familialism and self-identification among Hispanics. In: Bernal ME, Knight GP, editors. Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities. SUNY; Albany, NY: 1993. pp. 181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Marín G, Gamba RJ. Acculturation and changes in cultural values. In: Chun KM, Organista PB, Marín G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2003. pp. 83–93. doi:10.1037/10472-007. [Google Scholar]

- Marín G, Marín BV. Research with Hispanic populations. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Parsai M, Kulis S, Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center Effects of familism and family cohesion on problem behaviors among adolescents in Mexican immigrant families in the southwest United States. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work: Innovation in Theory, Research & Practice. 2009;18:203–220. doi: 10.1080/15313200903070965. doi:10.1080/15313200903070965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Waller M. Language preference and drug use among Southwestern Mexican American middle school students. Children & Schools. 2002;24:145–158. doi:10.1093/cs/24.3.145. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Grissom GR, Zanis D, Randall M. Problem-service “matching in addiction treatment: A prospective study in 4 programs. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:730–735. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830200062008. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830200062008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda AO, Estrada D, Firpo-Jimenez M. Differences in family cohesion, adaptability, and environment among Latino families in dissimilar stages of acculturation. The Family Journal. 2000;8:341–350. doi:10.1177/1066480700084003. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrani VB, Santisteban DA, Muir JA. Addressing immigration-related separations in Hispanic families with a behavior-problem adolescent. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74:219–229. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.3.219. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.74.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney-Day NE, Alegría M, Sribney W. Social cohesion, social support, and health among Latinos in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:477–495. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.030. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. Author; Los Angeles: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Myers HF, Rodriguez N. Acculturation and physical health in racial and ethnic minorities. In: Myers HF, Rodriguez N, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2003. pp. 163–185. doi:10.1037/10472-011. [Google Scholar]

- Nee V, Alba R. Toward a definition. In: Jacoby T, editor. Reinventing the melting pot: The new immigrants and what it means to be American. Basic Books; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Organista PB, Organista KC, Kuraski K. The relationship between acculturation and ethnic minority health. In: Chun KM, Organista PB, Marín G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2003. pp. 139–161. doi:10.1037/10472-010. [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek G, Stattin H, Vermulst A, Ha T, Engels RCME. Parent-child relationships, partner relationships, and emotional adjustment: A birth-to-maturity prospective study. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:429–437. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.429. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS, Cohn D. Unauthorized immigrant population: National and state trends, 2010. 2011 Retrieved from http://njdac.org/blog/wp-content/plugins/downloads-manager/upload/2010%20undocumented%20trends%20by%20state.pdf.

- Paynter CK, Estrada D. Multicultural training applied in clinical practice: Reflections from a Euro-American female counselor-in-training working with Mexican immigrants. The Family Journal. 2009;17:213–219. doi:10.1177/1066480709338280. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JR, Crano WD, Quist R, Burgoon M, Alvaro EM, Grandpre J. Acculturation, familism, parental monitoring, and knowledge as predictors of marijuana and inhalant use in adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:3–11. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.3. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera FI, Guarnaccia PJ, Mulvaney-Day N, Lin JY, Torres M, Alegría M. Family cohesion and its relationship to psychological distress among Latino groups. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2008;30:357–378. doi: 10.1177/0739986308318713. doi:10.1177/0739986308318713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marín G, Otero-Sabogal R, VanOss Marín B, Perez-Stable EJ. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn't? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. doi:10.1177/07399863870094003. [Google Scholar]

- Salganik MJ, Heckathorn DD. Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent-driven sampling. Sociological Methodology. 2004;34:193–240. doi:10.1111/j.0081-1750.2004.00152.x. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ. The applicability of familism to diverse ethnic groups: A preliminary study. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2007;147:101–118. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.147.2.101-118. doi:10.3200/SOCP.147.2.101-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65:237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. doi:10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Sobell LC, Sobell MB, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 1992. pp. 41–72. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0357-5_3. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies . The NSDUH report: Substance use treatment need and receipt among Hispanics. Rockville, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Coatsworth JD. An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: A developmental model of risk and protection. In: Glantz M, Hartel CR, editors. Drug Abuse: Origins and Interventions. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1999. pp. 331–366. doi:10.1037/10341-014. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5th ed. Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education; Boston, MA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker CM, Herman KC. Resolving the paradoxes of and barriers to patient-centered culturally sensitive health care: Lessons from the history of counseling and community psychology. The Counseling Psychologist. 2007;35:735–743. doi:10.1177/0011000007304297. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. Family status and health behaviors: Social control as a dimension of social integration. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1987;28:306–319. doi:10.2307/2136848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Whiteman SD, Thayer SM, Delgado MY. Adolescent sibling relationships in Mexican American families: Exploring the role of familism. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:512–522. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.512. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau QT-P10 - Hispanic or Latino by Type: 2010 Census summary File 1. 2010 Retrieved from http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_SF1_QTP10&prodType=table.

- Villarreal R, Blozis SA, Widaman KF. Factorial invariance of a pan-Hispanic familism scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2005;27:409–425. doi:10.1177/0739986305281125. [Google Scholar]

- Warner LA, Valdez A, Vega WA, De La Rosa M, Turner RJ, Canino G. Hispanic drug abuse in an evolving cultural context: An agenda for research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;84:S8–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.003. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]