Abstract

Osteoporosis has been described in animal models of mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS). Whether clinically significant osteoporosis is common among children with MPS is unknown. Therefore, cross-sectional data from whole body (WB; excluding head) and lumbar spine (LS) bone mineral density (BMD) compared with sex-, chronologic age–, and ethnicity-matched healthy individuals (Zage), height-for-age (HAZ) Z-score (ZHAZ) and bone mineral content (BMC) measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) in 40 children with MPS were analyzed. A subset of these children (n = 24) was matched 1:3 by age and sex to a group of healthy children (n = 72) for comparison of BMC adjusted for Tanner stage, race, lean body mass, height, and bone area. Low BMD Z-score was defined as Z-score of −2 or less. In children with MPS, 15% had low WB Zage and 48% had low LS Zage; 0% and 6% had low WB ZHAZ and low LS ZHAZ, respectively. Adjusted WB BMC was lower in MPS participants (p = 0.009). In conclusion, children with MPS had deficits in WB BMC after adjustments for stature and bone area. HAZ adjustment underestimated bone deficits (i.e., overestimated WB BMD Z-scores) in children with MPS likely owing to their abnormal bone shape. The influence of severe short stature and bone geometry on DXA measurements must be considered in children with MPS to avoid unnecessary exposure to antiresorptive treatments.

Keywords: Bone mineral content, bone mineral density, mucopolysaccharidoses, osteoporosis, skeletal dysplasia

Introduction

Mucopolysaccharidoses (MPS) are lysosomal storage diseases owing to enzymatic deficiencies in the degradation of specific complex carbohydrates. The enzymatic deficiencies result in the lysosomal accumulation of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in various tissues including bone and joint tissue. Clinically, MPS types I, II, and VI have similar skeletal disease that is characterized by varying degrees of short stature, coarse facial features, dysostosis multiplex (including kyphosis, scoliosis, hip dysplasia, and genu valgum), as well as corneal clouding, cardiac and pulmonary manifestations, and hepatosplenomegaly (1–4). Characteristics of the skeletal disease in MPS include vertebrae described as “beaked” with the beak projecting from the anteroinferior aspect of the vertebrae, “oar-shaped” ribs, short broad long bones, and bullet-shaped phalanges (5,6). MPS I can be divided into 2 categories clinically; the most severe form is MPS IH (Hurler syndrome), and the attenuated forms (MPS IHS/IS) are identified as Hurler-Scheie and Scheie syndromes. MPS IH is commonly treated with hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). MPS IHS/IS, MPS II (Hunter syndrome), and MPS VI (Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome) are currently treated with enzyme replacement therapy (ERT). Treatment with HCT and/or ERT has significantly improved the duration and quality of life for these children. The long-term benefit vs risk of these treatments, however, is still being determined.

It is clear from animal studies of MPS that bone development and ossification are abnormal in MPS. GAG accumulation has been documented in all cells involved in bone formation and remodeling (osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and chondrocytes) in animal models of MPS (7–9) and in chondrocytes in a 30-mo-old child with MPS IH (10). Chondrocyte abnormalities in MPS interfere with normal formation of mineralized cartilage septae (8,10,11) that are required for osteoblasts and osteoclasts to form new bone. In addition, pockets of cartilage are retained within ossified bone in MPS I mice (9). Combined, these abnormalities in bone development and mineralization may alter bone density and strength.

It is unknown whether abnormalities seen in animal models of MPS can be extrapolated to osteoporosis or increased risk of fracture in children and adults affected with MPS disease. Determining the risk for osteoporosis in MPS I, II, and VI has become particularly important as these children are now healthier and more mobile; new and improved treatments carry a greater opportunity for fracture. However, accurate evaluation of bone mineral density (BMD) by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) in children with severe short stature is difficult. DXA provides a 2-dimensional image from which 3-dimensional bone density is estimated, which falsely decreased BMD in children with short stature simply because of small bone size (12). In contrast, bone mineral content (BMC) is a 2-dimensional measurement, and when adjusted for height and bone area (or width), it is less artificially affected by short stature when measured by DXA (13). Fung et al (14) found normal BMD by DXA in 4 boys with MPS II, and normal BMD after correcting for short stature in 3 of 4 children with MPS VI. Children with MPS IH are distinct from children and adults with other MPS disorders in that they are routinely treated with HCT, which may increase the risk of low BMD (15–17). Importantly, no studies have evaluated BMD in children with MPS I.

Until quite recently, patients with MPS did not have any therapy available to them and frequently died in childhood or young adulthood; however, with the successful development of ERT and application of HCT for the treatment of children with MPS I, II and VI, pediatricians are now seeing more and more of these children in their general clinical practice. It is critical that physicians understand how to interpret DXA in these children with severe short stature to avoid unnecessary exposures to antiresorptive medications. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to establish whether children with MPS I, II, or VI have a high prevalence of low BMD and determine the most accurate interpretation of BMD by DXA in the presence of severe short stature. To address these objectives, we first determined the prevalence of low BMD (Z-score < −2) by DXA and adjusted these Z-scores for bone age and then height-for-age (HAZ) Z-score (ZHAZ) using the method as described by Zemel et al (12). Next, we compared BMC in a subset of children with MPS to age- and sex-matched healthy children to most effectively remove the influence of bone size on DXA outcomes and determine the validity of using HAZ adjustment in children with severe short stature.

Materials and Methods

Data presented in this manuscript are from the baseline visits for 40 individuals with MPS IH, MPS IHS/IS, II, or VI recruited into a 5-yr, natural history study of bone and endocrine disease in children with MPS before November 2011. Children aged 5–16 yr at the time of study entry were eligible to participate. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, radiation exposure above 500 mrem in the previous 12 mo, non-English speaking, or inability to comply with study procedures. Informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of all participants, and assent was obtained from all participants aged 7 yr and older whenever cognitively possible. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Minnesota and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

All participants, patients with MPS and controls, were fasting for 8 h or more on the day of study. Anthropometric measurements included height measured by wall-mounted stadiometer (without shoes) to the nearest 0.1 cm and weight by electronic scale to the nearest 0.1 kg. Body mass index was calculated as weight (kilograms) divided by height (meter square). Pubertal Tanner stage (18) was assessed by physical examination by a trained study physician and bone age by the method of Greulich and Pyle (19). Relative bone age (bone age divided by chronologic age) was calculated to evaluate for precocious or delayed puberty.

DXA whole body (WB) and lumbar spine (LS) scans were performed using a Lunar Prodigy scanner (pediatric software version 9.3; General Electric Medical Systems, Madison, WI). The BMD (gram/centimeter square) and BMC (gram/centimeter) were measured for the WB, excluding head and the LS. The LS region of interest (ROI) was L1–L4; vertebrae were excluded if BMD Z-score for an individual vertebra was 1 standard deviation (SD) greater than any other vertebrae, and 2 or more vertebrae were required for inclusion in analyses. DXA data on healthy children were obtained from siblings of cancer survivors participating in a prior study of metabolic disease in childhood cancer survivors from the local community (20,21). The healthy children were scanned on a different Lunar Prodigy scanner, and therefore all DXA measurements were standardized between machines. Data from the 2 DXA scanners were cross-calibrated using a custom-built phantom (comprising an acrylic block, a polycarbonate sheet, and an aluminum sheet) that calibrated bone, fat, and lean tissue mass. Ten scans were performed on each scanner. Slight differences were found between machines for bone and fat; therefore, correction factors were made to adjust data from MPS participant scans to standardize with data from the healthy children scans. The WB and LS BMD Z-scores (compared with sex-, age-, and ethnicity-matched healthy individuals) were calculated from the GE Lunar Prodigy database by chronological age (Zage) and bone age (Zbone) as recommended by the International Society for Clinical Densitometry (22) and by HAZ as described by Zemel et al (12). Low BMD was defined as a Z-score less than or equal to −2. Fat mass (kilograms) and lean body mass (LBM; kilograms) were determined from WB scans.

The youngest participant among the healthy children was 9 yr old. Therefore, only a subset of children with MPS (n = 24; 6 MPS IH, 5 MPS IHS/IS, 9 MPS II, and 4 MPS VI) were compared with the healthy children (n = 72) matched (3 healthy children for every 1 MPS child) on age (±1 yr) and sex. Unlike BMD measurements by DXA, BMC measurements by DXA, when adjusted for height, weight, and bone area, are less falsely influenced by body size (13,23); therefore, WB excluding head and LS BMCs were compared between MPS and healthy children. For comparison of BMC between MPS and healthy children, matched LS ROIs were used (i.e., if only vertebrae L3–L4 were interpretable in the MPS participant, then only vertebrae L3–L4 were included in analysis for the healthy children matched to that participant). The LS scans from 9 of the 40 children with MPS were excluded because of hardware (n = 5) or inability to define individual vertebrae (n = 4). Vertebrae were excluded from LS ROI in 3 of the 40 children with MPS because of abnormally increased density of a single vertebrae (BMD Zage > 1 SD above all other vertebrae), which could indicate a compression fracture, although we did not obtain lateral scans or magnetic resonance imagings on any of the subjects to confirm a compression fracture diagnosis.

Descriptive statistics are presented as means ± SD for continuous variables and as numbers and percents for nominal variables. Student's t-test, analysis of variance, and χ2 or Fisher tests were used to analyze differences in BMD parameters between MPS types and between MPS vs healthy children. LBM and total body fat were adjusted for Tanner stage and height compared between patients with MPS and healthy children by logistic regression. Multivariable linear regression modeling was used to compare BMC in patients with MPS to that in healthy children and sequentially adjusted for differences in pubertal maturation, race, height, LBM, and bone area. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

MPS Participants

A total of 40 children with MPS (median age: 11.4, range 5.3–16.9 yr) were evaluated: 20 MPS IH, 6 MPS IHS/IS, 10 MPS II, and 4 MPS VI (Table 1). All children with MPS IH were treated with HCT at less than 3 yr of age (mean: 1.3, range: 0.2–2.9 yr). All children with MPS IHS/IS or II were currently being treated with ERT. Two participants with MPS VI were treated with HCT at ages 1.8 and 3.9 yr; the other 2 participants with MPS VI were currently being treated with ERT. Twelve (30%) participants with MPS were receiving treatment with human growth hormone (GH; 5 with GH deficiency) for an average of 3.2 ± 2.5 yr (range: 0.3–8.5 yr) and 8 (20%) with levothyroxine for hypothyroidism (all with normal free thyroxine and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels at the time of the study). Four females and 1 male had untreated gonadal failure. Short stature (defined as height standard deviation score [SDS] < –2.25) was common (55%); average height SDS was −2.5 ± 1.7 (range: −6.0–0.5 SDS). Three (9%) of the participants with MPS had vitamin D deficiency defined as a 25-hydroxyvitamin D level lower than 20 ng/mL. Two children with MPS had a history of fracture: 1 child had a femur fracture at the age of 9 yr (8 yr before the study visit), and another child had a finger fracture at the age of 5 yr (6 yr before the study visit), both occurring after falling down while running.

Table 1. Characteristics of MPS Participants.

| Characteristics | MPS IH (n=20) | MPS IHS/IS (n = 6) | MPS II (n = 10) | MPS VI (n=4) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 9.5 ± 3.4 | 14.6 ± 2.5 | 10.5 ± 2.5 | 15.2 ± 2.1 | < 0.001 |

| Sex, female | 11 (55) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 0.017 |

| Race | |||||

| American Indian | 0 (0) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.044 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | |

| Black | 0 (0) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Other/mixed | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (20) | 0 (0) | |

| White | 20 (100) | 4 (67) | 7 (70) | 4 (100) | |

| Tanner stage | |||||

| 1 | 12 (60) | 0 (0) | 8 (80) | 0 (0) | 0.044 |

| 2–4 | 6 (30) | 3 (50) | 2 (20) | 2 (50) | |

| 5 | 2 (10) | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | 2 (50) | |

| Refused/unknown | 0 (0) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Bone age, yr | 9.4 ± 4.4 | 14.6 ± 3.9 | 8.5 ± 3.1 | 15.0 ± 3.4 | 0.004 |

| Relative bone agea | 1.0 ±0.2 | 1.0 ±0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.038 |

| Height, SDSb | −3.0± 1.5 | − 1.3 ± 1.3 | −1.5 ± 1.4 | −4.3 ± 0.6 | 0.002 |

| Weight, SDSb | −1.4 ± 1.6 | 0.4 ± 1.3 | −0.1 ± 1.2 | −3.6 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 |

| BMI, %b | 70 ±25 | 79 ± 19 | 77 ± 16 | 37 ± 28 | 0.025 |

| LBM, kg | 19 ±5 | 39 ±9 | 27 ±5 | 28 ±10 | < 0.001 |

| LBM, kgc | 23 ±5 | 31 ±9 | 28 ±5 | 24 ±10 | 0.011 |

| Body fat, kg | 7 ±7 | 18 ±15 | 6 ± 6 | 4±3 | 0.019 |

| Body fat, kgc | 12±7 | 15 ±15 | 9 ± 6 | 1±3 | 0.040 |

Note: Mean ± SD or n (%) are reported.

Abbr: BMI, body mass index; IH, Hurler syndrome; IHS/IS, Hurler-Scheie and Scheie syndromes; LBM, lean body mass; MPS, mucopolysaccharidosis; SD, standard deviation; SDS, standard deviation score.

Relative bone age = the ratio of bone age to chronologic age and is a measure of pubertal timing.

Adjusted for age and sex.

Adjusted for Tanner stage and height.

DXA Measurements

Bone Mineral Density

Children with MPS had a high prevalence of low BMD by chronological age (Zage): 15% for the WB and 48% for the LS. After adjustment for bone age (Zbone), the prevalence of low BMD was approximately the same: 15% for the WB and 36% for the LS. In contrast, no children with MPS had low WB BMD, and only 6% had low LS BMD after adjustment for their short stature using the HAZ adjustment (ZHAZ). None of the children with vitamin D deficiency, as defined by a 25-hydroxyvitamin D level lower than 20 ng/mL, had low BMD: in these 3 children, WB BMD Zage ranged from 0.2 to 0.4 and LS BMD Zage ranged from −0.6 to −0.4. However, these vitamin D laboratory values are drawn from one point in time and may not be reflective of longitudinal vitamin D status.

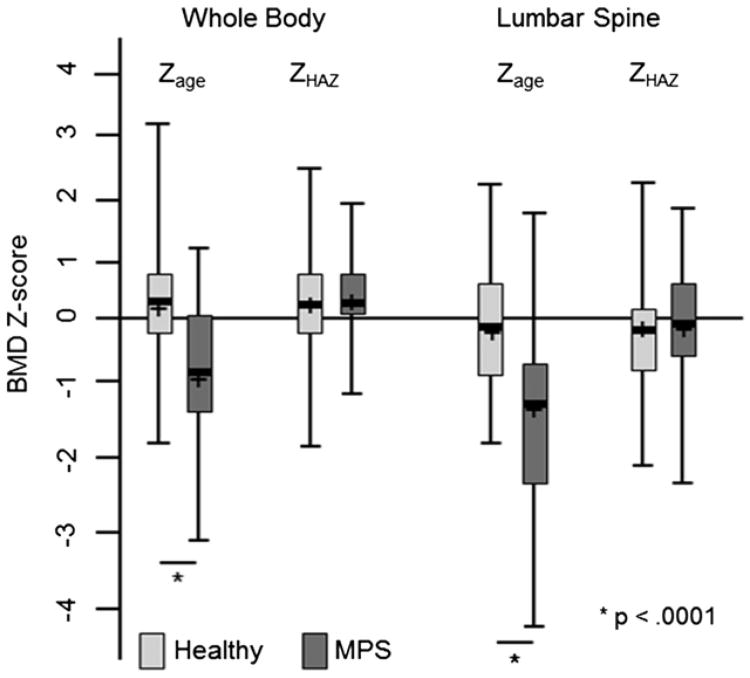

Comparisons of BMD Z-scores between children with MPS and healthy children are shown in Fig. 1. For all participants with MPS, mean WB and LS ZHAZ were no different than controls (0.4 ± 0.7 vs 0.3 ± 0.9, p = 0.75 and −0.2 ± 1.0 vs −0.3 ± 0.8, p = 0.57, respectively). Of the children with MPS (types IH, IHS/IS, II, and VI), those with MPS VI had the lowest WB and LS Zage (and also the most severe short stature; Table 2). There were no significant differences in WB or LS ZHAZ among MPS types (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

BMD Z-score comparisons between MPS and healthy children. Background shaded area indicates normal BMD Z-score range. The length of each box represents the interquartile range, and the horizontal line in each box represents the mean and the median. Vertical lines extend to the minimum and maximum values. BMD, bone mineral density; MPS, mucopolysaccharidosis; Zage, chronological age Z-score; ZHAZ, height-for-age Z-score.

Table 2. Bone Mineral Density Z-Scores by Chronological Age, Bone Age, and HAZ Adjustment for Short Stature.

| Parameters | MPS IH (n = 20) | MPS IHS/IS (n = 6) | MPS II (n = 10) | MPS VI (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole body excluding head | ||||

| Chronological age Z-score | −0.9 ± 1.0a | −0.5 ± 0.8ab | −0.1 ± 0.7b | −2.2 ± 0.9c |

| Bone age Z-score | −0.9 ± 1.3ac | −0.3 ± 0.9a | 1.2 ± 1.2b | −2.1 ± 0.9c |

| HAZ Z-score | 0.5 ± 0.7a | 0.2 ± 0.9a | 0.5 ± 0.3a | −0.1 ± 0.7a |

| Lumbar spine | ||||

| Chronological age Z-score | −2.0 ± 0.7a | −0.9 ± 1.2b | −0.5 ± 1.0b | −2.8 ± 1.6a |

| Bone age Z-score | −2.1 ± 0.6a | −0.4 ± 1.8b | 0.3 ± 1.4b | −2.8 ± 1.2a |

| HAZ Z-score | −0.5 ± 1.0a | 0.0 ± 0.9a | 0.3 ± 0.7a | −0.1 ± 1.7a |

Notes: Mean ± SD are presented. Different letters indicate significant difference between groups (p < 0.05). Low BMD is defined as BMD Z-score ≤ −2.

Abbr: BMD, bone mineral density; IH, Hurler syndrome; IHS/IS, Hurler-Scheie and Scheie syndromes; HAZ, height-for-age; MPS, mucopolysaccharidosis; SD, standard deviation.

Bone Mineral Content

Given that the prevalence of low BMD was highly dependent on the method (e.g., Zage, Zbone, and ZHAZ) used to interpret BMD, BMC in a subset of children with MPS was compared with BMC in age- and sex-matched healthy children. Characteristics of children with MPS and those of matched healthy controls are displayed in Table 3. Of note, children with MPS had lower height SDS, higher LBM (after adjustment for Tanner stage and height), and slightly delayed bone age (lower relative bone age) compared with healthy children.

Table 3. Characteristics of MPS Compared With Healthy Children.

| Characteristics | MPSa (n = 24) | Healthy children (n = 72) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 12.8 ± 2.7 | 13.0 ± 2.6 | 0.763 |

| Sex, female | 6 (25) | 19 (26) | 0.893 |

| Race | |||

| American Indian | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.052 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 (14) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Black | 1 (14) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Other/mixed | 1 (14) | 1 (1.3) | |

| White | 21 (88) | 69 (96) | |

| Tanner stage | |||

| 1 | 9 (38) | 20 (28) | 0.238 |

| 2–4 | 10 (42) | 39 (54) | |

| 5 | 4 (17) | 12 (17) | |

| Refused/unknown | 1 (3) | 1 (1) | |

| Bone age, yr | 11.9 ± 4.0 | 13.1 ± 2.8 | 0.113 |

| Relative bone ageb | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | < 0.001 |

| Height, SDSc | −2.5 ± 1.8 | 0.3 ± 1.0 | < 0.001 |

| Weight, SDSc | −1.2 ± 1.9 | 0.4 ± 1.1 | < 0.001 |

| BMI, %c | 66 ± 25 | 59 ± 29 | 0.308 |

| LBM, kg | 28 ± 8 | 38 ± 12 | < 0.001 |

| LBM, kgd | 38 ± 8 | 34 ± 12 | 0.047 |

| Body fat, kg | 9 ± 7 | 12 ± 9 | 0.059 |

| Body fat, kgd | 12 ± 7 | 11 ± 9 | 0.889 |

| Whole body BMC, g | 1037 ± 409 | 1601 ± 677 | < 0.001 |

| Lumbar spine BMC, g | 25 ± 12 | 42 ± 20 | < 0.001 |

Notes: Mean ± SD or n (%) are reported. MPS and healthy children were matched 1:3 on age and gender.

Abbr: BMC, bone mineral content; BMI, body mass index; IH, Hurler syndrome; LBM, lean body mass; MPS, mucopolysaccharidosis; SD, standard deviation; SDS, standard deviation score.

MPS IH, n = 6; MPS IA, n = 5; MPS II, n = 9; and MPS VI, n = 4.

Relative bone age = the ratio of bone age to chronologic age and is a measure of pubertal timing.

Adjusted for age and gender.

Adjusted for Tanner stage and height.

After adjustment for pubertal stage, race, and LBM, BMC of the LS was lower in MPS vs healthy children; however, these differences in BMC were no longer significant after further adjustment for height and bone area (Table 4). BMC of the WB excluding head was lower in MPS vs healthy children after adjustment for pubertal stage, race, and LBM (p = 0.04). There was no difference in WB BMC between groups with the addition of height or bone area individually to the model (p > 0.80); however, when both height and bone area were included, WB BMC was lower in MPS compared with healthy children (p = 0.009; Table 4). After adjustment for Tanner stage, race, and height, WB bone area was significantly higher in MPS compared with healthy children (1721 ± 361 vs 1596 ± 442, p = 0.027), but there was no difference in LS area (p = 0.33) between the 2 groups.

Table 4.

Nested Linear Regression Models of the Effect of MPS on Lumbar Spine and Whole Body Excluding Head Bone Mineral Content (BMC) in MPS vs Healthy Children

| Models | Covariates | Estimated BMC difference MPS – healthy children (SE) | p Value | R2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumbar spine | ||||

| 1 | MPS, Tanner stage, race, LBM | −6 (2) | 0.011 | 82 |

| 2 | Model 1 + height | −4 (3) | 0.202 | 83 |

| 3 | Model 1 + BA | 1 (2) | 0.458 | 93 |

| 4 | Model 1 + height, BA | 1 (2) | 0.555 | 93 |

| 5 | Model 1 + height, BA, height × BA | 1 (2) | 0.740 | 93 |

| Whole body | ||||

| 1 | MPS, Tanner stage, race, LBM | − 141 (68) | 0.042 | 87 |

| 2 | Model 1 + height | − 10 (82) | 0.904 | 88 |

| 3 | Model 1 + BA | − 10 (40) | 0.810 | 96 |

| 4 | Model 1 + height, BA | − 112 (45) | 0.015 | 97 |

| 5 | Model 1 + height, BA, height × BA | − 103 (39) | 0.009 | 97 |

Note: MPS and healthy children were matched 1:3 by age and gender.

Abbr: BA, bone area; LBM, lean body mass; MPS, mucopolysaccharidosis; SE, standard error.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that the high prevalence of low BMD Z-scores reported by DXA in children with MPS and short stature is inaccurate. However, our finding of lower total body BMC in children with MPS compared with healthy children after accounting for differences in body size and bone area indicates that the HAZ adjustment overestimates WB BMD Z-scores in children with MPS, likely because of abnormal bone geometry. The HAZ adjustment did appropriately correct LS BMD Z-scores in children with MPS and severe short stature.

The different findings for WB vs LS in MPS children are likely related to characteristic bone abnormalities of this skeletal dysplasia. The term “dysostosis multiplex” is used to describe the constellation of skeletal abnormalities characteristic of MPS diseases and includes large skulls, paddle-like ribs, anteroinferior beaking of thoracic vertebrae, hypoplastic lumbar vertebral bodies, hip dyplasia, flat femurs with short metaphyses, genu valgum, flaring of the iliac wings, “bullet-shaped” phalanges, and diaphyseal expansion of the long bones (5,6). Therefore, it is incorrect to assume that bone size is equivalent between children with MPS and healthy children, even if age, gender, height, and Tanner stage are the same. The addition of bone area to our modeling partially takes into account differences in bone size and shape. The lack of difference in LS between MPS and healthy children may be owing to our selection of relatively healthy- (i.e., normal) appearing vertebrae for comparison.

It is well documented that DXA underestimates BMD in children with mild short stature because of the limited 2-dimensional estimation of BMD by DXA (12,13,23); however, the shortest height in the study establishing the HAZ adjustment was −2.6 SDS. Therefore, it was not known if HAZ adjustment could be applied to children with more severe short stature. Children with skeletal dysplasias (i.e., MPS, chondroplasias, and osteogenesis imperfecta) and metabolic bone diseases (i.e., osteopetrosis or hypoparathyroidism) frequently have severe short stature, making interpretation of DXA difficult. Our results show that in children with height SDS as low as −6.0, the HAZ method of BMD Z-score adjustment provided a more similar answer to directly comparing BMC between MPS and healthy children. However, it overestimated WB BMD Z-score by on average approximately 0.25 SD when bone area was considered as well.

Low LS and WB BMD Zage have been previously reported in 4 children with MPS VI; and similar to our results, BMD Zhaz was normal in most (3/4) of those children (14). The lowest height SDS in the study by Fung et al (14) was −9.9 SDS. No bone deficits were reported in the 4 boys with MPS II previously described. Our study confirms the lack of low BMD Z-scores in a larger group of children with MPS II and MPS VI. We expected to find bone deficits in children with MPS IH because they all had a history of treatment with HCT and are therefore at higher risk for low BMD because of chemotherapeutic and radiation exposures during HCT (15–17). However, we found similar BMD ZHAZ and BMC in MPS IH compared with healthy children.

This study has several limitations. Data on the healthy children were taken as a “convenience sample” from another study, although only those matched by age (±1 yr) and sex to an MPS participant were included in the analysis. The difference of ± 1 yr used for our matching could result in a significant variation in BMC especially during the period of puberty; for this reason, we adjusted all of our comparisons between MPS and matched healthy children for pubertal development (Tanner stage). Unfortunately, we needed to limit our BMC comparison to the MPS participants aged 9 yr and older because the youngest child in the healthy control group was 9 yr old. Therefore, we are unable to make conclusions about BMC in the MPS children younger than 9 yr. However, it is likely that our results are applicable to younger children with MPS, as the process affecting their skeletal development is lifelong.

Another limitation is that DXA measurements do not account for differences in bone geometry that exist between MPS and healthy children. For example, it is possible that the addition of bone area to our modeling did not adequately account for the fact that children with MPS have wider and abnormally shaped bones. Other imaging studies such as peripheral quantitative computer tomography are needed to evaluate bone geometry and strength in children with MPS. In addition, 30% of the children with MPS were being treated with GH (only 5 of the 12 were GH deficient). Although GH treatment may improve BMD (24), after adjustment for body size it does not appear to have a significant impact on BMD in children with GH deficiency or idiopathic short stature (25). Finally, the HAZ adjustment of BMD Z-scores was developed on a Hologic DXA machine; all our data presented are from GE Lunar DXA machines for which this adjustment has not been validated. Despite these limitations, this study has a number of strengths including its sample size within a single institution, inclusion of children with MPS I, measurement of bone density in the spine and WB, and evaluation of the validity of use of HAZ adjustment for BMD Z-scores in children with severe short stature and a skeletal dysplasia.

In conclusion, we found that children with MPS have low WB and LS BMD for chronological age and sex, but normal WB and LS BMD after HAZ adjustment of BMD Z-scores. The adjustment for short stature by HAZ underestimates WB bone deficits in MPS likely because of their abnormal bone shape. The influence of severe short stature and bone geometry on DXA measurements must be considered when assessing BMD in children with MPS to avoid unnecessary exposure to antiresorptive treatments.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the study participants and parents as well as Jane Kennedy, RN, who made this project possible.

This project was supported by grant number K23AR057789 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, U54NS065768 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, 1UL1RR033183 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), and by 8UL1TR000114 and UL1RR024131 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to the University of Minnesota and to the Children's Hospital and Research Center, Oakland, respectively, Clinical and Translational Science Institutes (CTSI). Comparison data on healthy children were provided by JS from a project supported by grant number RO1CA113930-01A1 from the National Cancer Institute, M01-RR00400 from the NCCR, and the Children's Cancer Research Fund (JS). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CTSI or the NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosure summary: EF, JS, and KEE have nothing to declare. LEP and PO received grant support from Genzyme. DV receives grant support from Shire. DAS received honorariums from Guidepoint Global. CBW received grant support from Genzyme, BioMarin, and Shire.

References

- 1.Pastores GM, Arn P, Beck M, et al. The MPS I registry: design, methodology, and early findings of a global disease registry for monitoring patients with mucopolysaccharidosis type I. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;91(1):37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Link B, de Camargo Pinto LL, Giugliani R, et al. Orthopedic manifestations in patients with mucopolysaccharidosis type II (Hunter syndrome) enrolled in the Hunter Outcome Survey. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2010;2(2):e16. doi: 10.4081/or.2010.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wraith JE, Scarpa M, Beck M, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis type II (Hunter syndrome): a clinical review and recommendations for treatment in the era of enzyme replacement therapy. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167(3):267–277. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0635-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giugliani R, Harmatz P, Wraith JE. Management guidelines for mucopolysaccharidosis VI. Pediatrics. 2007;120(2):405–418. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt H, Ullrich K, von Lengerke HJ, et al. Radiological findings in patients with mucopolysaccharidosis I H/S (Hurler-Scheie syndrome) Pediatr Radiol. 1987;17(5):409–414. doi: 10.1007/BF02396619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aldenhoven M, Sakkers RJ, Boelens J, et al. Musculoskeletal manifestations of lysosomal storage disorders. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(11):1659–1665. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.095315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monroy MA, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL, Sands MS. Abnormal osteoclast morphology and bone remodeling in a murine model of a lysosomal storage disease. Bone. 2002;30(2):352–359. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00679-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nuttall JD, Brumfield LK, Fazzalari NL, et al. Histomorphometric analysis of the tibial growth plate in a feline model of mucopolysaccharidosis type VI. Calcif Tissue Int. 1999;65(1):47–52. doi: 10.1007/s002239900656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell C, Hendson G, Jevon G, et al. Murine MPS I: insights into the pathogenesis of Hurler syndrome. Clin Genet. 1998;53(5):349–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1998.tb02745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silveri CP, Kaplan FS, Fallon MD, et al. Hurler syndrome with special reference to histologic abnormalities of the growth plate. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;269:305–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simonaro CM, D'Angelo M, Haskins ME, Schuchman EH. Joint and bone disease in mucopolysaccharidoses VI and VII: identification of new therapeutic targets and biomarkers using animal models. Pediatr Res. 2005;57(5 Pt 1):701–707. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000156510.96253.5A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zemel BS, Leonard MB, Kelly A, et al. Height adjustment in assessing dual energy x-ray absorptiometry measurements of bone mass and density in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(3):1265–1273. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prentice A, Parsons TJ, Cole TJ. Uncritical use of bone mineral density in absorptiometry may lead to size-related artifacts in the identification of bone mineral determinants. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60(6):837–842. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/60.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fung EB, Johnson JA, Madden J, et al. Bone density assessment in patients with mucopolysaccharidosis: a preliminary report from patients with MPS II and VI. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2010;3(1):13–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatia S, Ramsay NK, Weisdorf D, et al. Bone mineral density in patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation for myeloid malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;22(1):87–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daniels MW, Wilson DM, Paguntalan HG, et al. Bone mineral density in pediatric transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2003;76(4):673–678. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000076627.70050.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaste SC, Shidler TJ, Tong X, et al. Bone mineral density and osteonecrosis in survivors of childhood allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33(4):435–441. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanner JM, editor. Assessment of skeletal maturity and prediction of adult height (TW2 method) New York: Academic Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greulich WW, Pyle SI. Radiographic atlas of skeletal development of the hand and wrist. 2nd. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinberger J, Sinaiko AR, Kelly AS, et al. Cardiovascular risk and insulin resistance in childhood cancer survivors. J Pediatr. 2012;160(3):494–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polgreen LE, Petryk A, Dietz AC, et al. Modifiable risk factors associated with bone deficits in childhood cancer survivors. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baim S, Leonard MB, Bianchi ML, et al. Official Positions of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry and executive summary of the 2007 ISCD Pediatric Position Development Conference. J Clin Densitom. 2008;11(1):6–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wren TA, Liu X, Pitukcheewanont P, Gilsanz V. Bone acquisition in healthy children and adolescents: comparisons of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry and computed tomography measures. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(4):1925–1928. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lanes R, Gunczler P, Esaa S, Weisinger JR. The effect of short- and long-term growth hormone treatment on bone mineral density and bone metabolism of prepubertal children with idiopathic short stature: a 3-year study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2002;57(6):725–730. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hogler W, Briody J, Moore B, et al. Effect of growth hormone therapy and puberty on bone and body composition in children with idiopathic short stature and growth hormone deficiency. Bone. 2005;37(5):642–650. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]