Abstract

Peripheral T-cell (PTCL) and NK cell lymphomas have poor survival with conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy. Because angiogenesis plays an important role in the biology of PTCL, a fully humanized anti-VEGF antibody, bevacizumab (A), was studied in combination with standard CHOP chemotherapy (ACHOP) to evaluate its potential to improve outcome in these patients.

Patients were treated with 6–8 cycles of ACHOP followed by 8 doses of maintenance A (15 mg/kg every 21 days). 46 patients were enrolled on this phase 2 study from July 2006 through March 2009. 44 patients were evaluable for toxicity and 39 were evaluable for response, progression and survival.

A total of 324 cycles (range: 2–16, median 7) were administered to 39 evaluable patients and only 9 completed all planned treatment. The overall response rate was 90% with 19 (49%) CR/CRu, 16 (41%) PR. The 1-year progression free survival (PFS) rate was 44% at a median follow-up of 3 years. The median PFS and overall survival (OS) rates were 7.7 and 22 months, respectively. Twenty-three patients died (21 from lymphoma, 2 while in remission). Grade 3 or 4 toxicities included febrile neutropenia (n=8), anemia (n=3), thrombocytopenia (n=5), congestive heart failure (n= 4), venous thrombosis (n=3), gastrointestinal hemorrhage /perforation (n=2), infection (n=8), and fatigue (n=6). Despite a high overall response rate, the ACHOP regimen failed to result in durable remissions and was associated with significant toxicities. Studies of novel therapeutics are needed for this patient population, whose clinical outcome remains poor.

Keywords: Lymphoma and Hodgkin disease, Chemotherapeutic approaches, Immunotherapeutic approaches

Introduction

Peripheral T- cell (PTCL) and natural killer (NK) cell lymphomas are rare diseases with a poor outcome (1). In the 2008 WHO classification (2), the most common nodal PTCL subtypes are angioimmunoblastic T cell (AITL), anaplastic large cell lymphoma and PTCL-NOS (not otherwise specified). Traditionally, PTCL have been treated with regimens used for DLBCL (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma) with anthracycline containing regimens. However outcomes are poor with a 3-year survival of approximately 30% (3).

Angiogenesis is an integral part in the development, progression and distant spread of cancer. VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) and its receptors are frequently expressed in NHL (4) and plasma levels of angiogenesis factors, such as VEGF and VCAM, have been reported to be associated with inferior outcome (5). It is postulated that VEGF is released from the lymphoma cells and binds to the VEGFR1 on the lymphoma cell surface (autocrine pathway) (6). In addition, it is believed that VEGF is also released from the tumor microenvironment resulting in local neovascular transformation (angiogenesis) and recruitment of circulating progenitors derived from the bone marrow (vasculogenesis) (7). High levels of VEGF expression are also associated with resistance to chemotherapy in NHL and xenograft models (8–10). Within NHL subtypes, VEGF overexpression has been reported more with PTCL and is associated with a poor outcome (11,12). Since angiogenesis plays an important role in the biology of PTCL, a rational therapeutic strategy is to study the inhibition of angiogenesis by blocking VEGF.

Bevacizumab (Avastin (A), Genentech, So San Francisco, CA, USA) is a humanized monoclonal antibody against VEGF, which is currently approved for the treatment of several solid tumors, including colon, lung, renal cell and brain. Bevacizumab administered with chemotherapy improves the response rate and outcome compared with chemotherapy alone in patients with a variety of solid tumors (13,14). We hypothesized that the addition of bevacizumab to standard CHOP chemotherapy (cyclosphosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) would prolong the progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with previously untreated PTCL.

Patients and methods

Patients older than 18 years with untreated PTCL and NK-T cell but excluding anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) ALK-positive and primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, were eligible for this study. All patients had adequate performance status (ECOG PS 0–2), hepatic, renal, and hematologic function at study entry. Patients with a history of seizure disorder, stroke, bleeding diathesis, uncontrolled hypertension, and proteinuria were excluded. Diagnostic pathology slides were centrally reviewed. Patients had at least one measureable objective disease site on computed tomography (CT) or 18FDG-PET/CT (Positron emission tomography). Due to reports of cardiotoxicity in breast cancer patients previously exposed to anthracyclines associated with bevacizumab, all patients had measurement of the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) by echocardiogram or multi-gated acquisition scan (MUGA) at baseline and after cycle 6 of ACHOP. The study was approved by the participating centers’ institution review board and all patients signed an informed consent. After completion of therapy, patients were followed with history, physical exam and scans every 3 months the first two years from study entry, then every 6 months for 3 to 5 years.

Treatment and measurement of effect

Patients were to receive 6–8 cycles of ACHOP followed by 8 cycles of maintenance bevacizumab (MA), as outlined below. Bevacizumab 15 mg/kg was administered on day 1 over 90 min (1st cycle), 60 min (2nd cycle) and 30 min for the subsequent cycles. CHOP (cyclophosphamide750 mg/m2; doxorubicin 50 mg/m2; vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 (max 2 mg); prednisone 100 mg daily on d 1–5) was administered on day 1 of a 21 day cycle. Radiographic response was assessed after cycles 3, 6, and 8 of ACHOP and after cycle 8 of MA. Patients received 6 cycles of ACHOP if they achieved a CR after 3 cycles, 8 cycles if they achieved a PR after 3 cycles. Non responders were removed from the study. ACHOP responders received maintenance bevacizumab 15 mg/kg every 21 days for 8 cycles. Response criteria were based on the International Workshop to Standardize Criteria for Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (15). All patients, regardless of eligibility status, were followed for development of secondary cancers.

Statistical considerations

The primary endpoint of this study was the 1 year PFS rate, which was defined as the proportion of patients who were progression free and alive at 1 year from registration. A 1-year PFS rate of 30% was considered non-promising and 50% was considered promising. A one-stage design was used because of the limited treatment options available for these patients. The study was to accrue 43 patients in order to have 39 eligible. According to the above assumptions, ACHOP would be considered promising for further study if 16 of 39 patients were progression free at 1-yr. The probability of concluding that the regimen is effective is 0.90 assuming a true underlying 1 year PFS rate of 50% and is 0.09 if the true underlying 1 year PFS rate is 30%.

Baseline patient characteristics were listed with descriptive statistics (mean, median, percentage). PFS was defined as the time from registration to the progression, relapse or death. Overall survival (OS) was measured from registration to death of any cause. The response rate was reported for overall response and CR/CRu with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the survival distribution. Comparisons between histology groups were conducted among eligible patients with a log-rank test. Toxicity and secondary primary cancers were evaluated for all patients regardless of eligibility. Due to poor accrual the study was amended in 2008 to allow patients who had received one prior cycle of CHOP to enroll.

Results

A total of 46 patients were enrolled between July 2006 and March 2009 at participating ECOG centers. The last two patients on study did not start protocol therapy, one each due to ineligibility and patient refusal. Central pathology review was performed on 43 patients, of which four were determined not to have PTCL or NK cell lymphoma. Therefore, 39 patients were eligible for efficacy analysis and their characteristics are listed in Table 1. Eighteen of 39 (46%) patients had stage 4 disease, and 8 of 39 (20%) had lymph node masses > 5 cm. B symptoms were present in half of the patients and 10 of 39 (26%) had >1 extranodal sites of involvement. The most common subtypes were PTCL-NOS and AITL. All 7 anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) tumors were ALK-negative. Six of 7 pts with ALCL had an IPI<2, compared to 8 of 15 with PTCL-NOS, and 10 of 17 with AITL.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (n=39)

| Gender | |

| Female | 11 (28%) |

| Male | 28(72%) |

| Age | |

| Median | 60(21–81) |

| ECOG | |

| 0–1 | 34(87%) |

| 2 | 5(13%) |

| Number of extranodal sites | |

| 0–1 | 29(74%) |

| 2–4 | 10(26%) |

| Stage | |

| II | 7(18%) |

| III | 14(36%) |

| IV | 18(46%) |

| Elevated LDH | 18(46%) |

| IPI | |

| 0–1 | 11(28%) |

| 2 | 13(33%) |

| 3–5 | 14(36%) |

| Subtype | |

| PTCL-NOS | 15(38%) |

| AITL | 17(44%) |

| ALCL-Primary Systemic, (ALK negative) | 7(18%) |

ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; LDH: Lactate Dehydrogenase; IPI: International Prognostic Index; PTCL-NOS: peripheral T cell lymphoma-not otherwise specified; AITL: angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma; ALCL: anaplastic large cell lymphoma

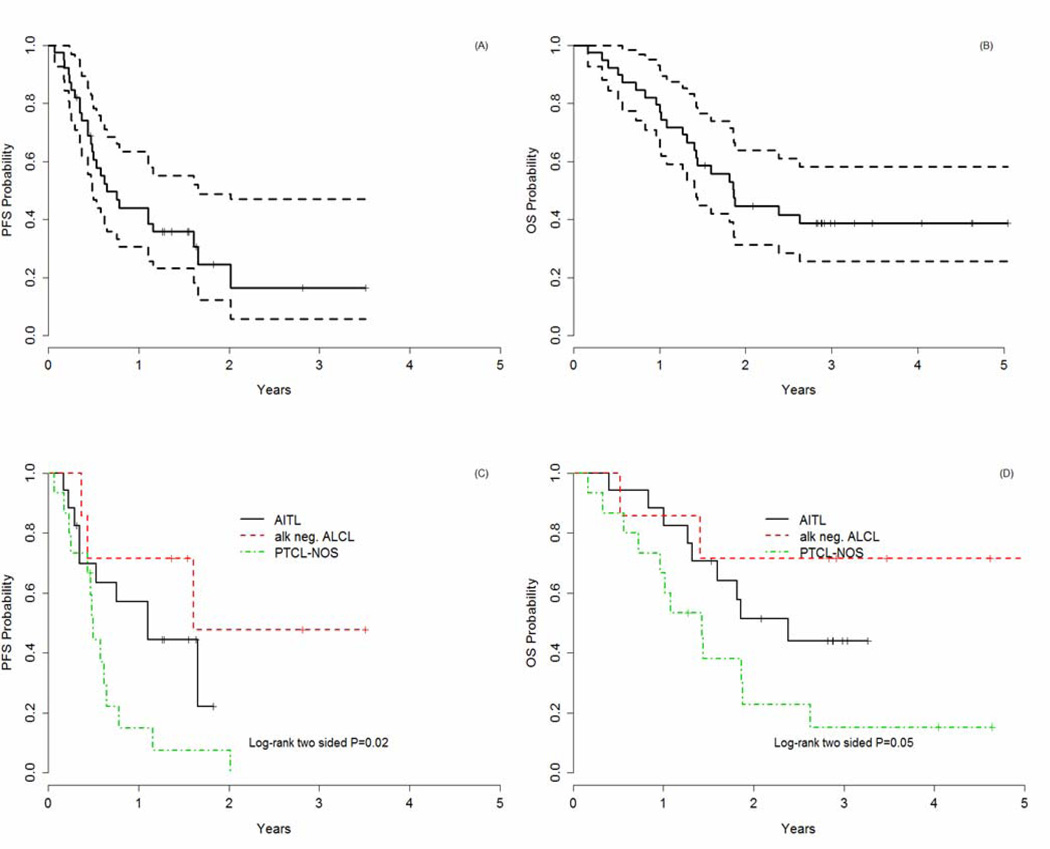

Of the 39 pts, 11 patients received fewer than 6 cycles (range 2–5) of ACHOP, 28 had 6–8 cycles, and 15 commenced MA. Only 9 of 39 patients completed all planned therapy per study design. Eight of 17 (47%) patients with AITL received MA, compared to 4 of 15 (27%) of patients with PTCL-NOS. The inability to complete all cycles was largely due to toxicity rather than disease progression. Thirty-five patients (90%) (95% CI: 76–93%) responded to ACHOP, with 49% achieving a CR/CRu (95% CI: 58–87%) (Table 3). 3 of 39 (8%) had PD while on treatment. All 7 of the ALCL patients responded with an 86% (6 of 7) CR rate, compared to 33% (5 of 15) and 53% (9 of 17) CR rates in PTCL-NOS and AITL, respectively. With a median follow-up of 3 years, the 1-year PFS rate was 44%. The median PFS and OS rates were 7.7 and 22 months, respectively (Figures 1 and 2). The 1- yr PFS rate varied markedly by histologic subtype: 15% in PTCL-NOS, versus 57% in AITL and 71% in ALK-negative ALCL (p=0.02) (Figure C). The 1-yr OS rate was also significantly different in the various histologic types including: 67% in PTCL-NOS, 88% in AITL, and 86% in ALK-negative ALCL (p=0.05). Since patients were not followed after they developed PD, details on second- line therapy at relapse are not available.

Table 3.

Best Response (n=39)

| n(%) | |

|---|---|

| ORR | 35(90%) |

| CR/CRu | 19(49%) |

| PR | 16(41%) |

| SD | 1(2%) |

| PD | 3(8%) |

CR: Complete Response; CRu: Complete Response Unconfirmed; PR: Partial Response; SD: Stable Disease; PD: Progressive Disease; ORR: Overall Response Rate

Figure 1.

A: Progression-Free Survival (PFS)

B: Overall Survival (OS)

C: Progression-Free Survival (PFS) based on histology

D: Overall Survival (OS) based on histology

Grade 3 and 4 toxicities are listed in Table 2. The most common hematologic toxicity was grade 3 or 4 neutropenia with 8 patients experiencing grade 3 febrile neutropenic events. As previously reported, eight grade 2–4 cardiac events were reported in 6 of 30 (20%) patients who had received at least 6 cycles of ACHOP (16). A decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was observed in 5 patients (Grade 2, n=1; Grade 3, n=3; Grade 4, n=1). The LVEF improved to baseline in 4 of 5 patients after discontinuing therapy. One patient developed grade 3 gastrointestinal hemorrhage and another patient developed grade 3 gastrointestinal perforation which were not related to tumor lysis. At the time of this report, 23 of 39 patients have died, 21 due to disease progression. A single patient died on study of presumed sudden cardiac death, 17 days after receiving her 6th cycle of ACHOP. An autopsy was not granted. Fourteen patients are alive and 2 are lost to follow-up. Four secondary cancers have been reported in four of 44 (0.9%) patients and include breast, gastrointestinal, basal cell, and renal cell carcinoma.

Table 2.

Grade 3 or 4 Toxicity (n=44)

| G3(n) | G4(n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Hematologic | ||

| Neutropenia | 4 | 19 |

| Febrile Neutropenia | 8 | 0 |

| Anemia | 2 | 1 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 | 3 |

| Cardiac | ||

| Decrease LVEF | 4 | 0 |

| Ventricular Arrhythmia | 0 | 1 |

| Hypertension | 4 | 0 |

| Restrictive Cardiomyopathy | 0 | 1 |

| Venous Thrombosis | 1 | 2 |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 1 | 0 |

| Colon Perforation | 1 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 5 | 1 |

| Infection | 8 | 0 |

LVEF: Left ventricular Ejection Fraction

Discussion

Currently, there is no standard therapy for PTCL and in general, regimens used for B- cell NHL have been the mainstay of therapy and are associated with disappointing long- term outcomes. Gene expression profiling studies have shown that VEGF is significantly overexpressed in PTCL in comparison to B- cell lymphoma (17) and elevated serum VEGF levels are associated with poor outcome (5). It is therefore plausible that, angiogenesis may be associated with the fundamental biological difference between B and T-cell lymphomas and may be an important, contributing factor to the poor prognosis of PTCL.

The role of angiogenesis in PTCL provided the rationale for evaluating bevacizumab in combination with CHOP chemotherapy. While the response rate was 90% (CR 49%), the 3-year PFS and OS were 16% and 37%, respectively. In addition, the ACHOP combination was associated with excess cardiac toxicity as previously reported (16). Smaller experiences with ACHOP in combination with rituximab in DLBCL suggested that the combination was well tolerated and were not associated with changes in the pharmacokinetics of rituximab and bevacizumab (18) However, two recent larger studies also reported significantly increased cardiac toxicity leading to premature closure of the MAIN trial (19,20). Our results are not better than those achieved with CHOP alone as suggested in a meta-analysis of 31 studies of patients with PTCL treated with CHOP (n=2912) excluding ALCL, which reported an estimated 5-yr OS of 38.5% (95%CI 35.5–41.6) (21). Our results are also inferior to contemporary anthracycline-based therapies which have incorporated etoposide. The German Study Lymphoma Group reported the outcome of 265 patients with PTCL, excluding ALK-positive ALCL, with a 3-yr OS for patients treated with CHOEP (CHOP with etoposide) of 53.9–67.5%, depending on the T-cell lymphoma subtypes (22). A trend to improved EFS was seen in the ALK negative subgroup mainlyinin patients who were < 60 years old and had a normal LDH. In another study reported by Niitsu and colleagues, 84 PTCL patients were treated with the CyclOBEAP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, prednisolone) regimen with a 5-year OS of 72% and a PFS of 61% (23). The 5-yr OS was 93% for patients with ALK positive ALCL compared to 74% and 63% for AITL and PTCL-NOS, respectively.

When evaluating responses according to histology, patients with ALK-negative ALCL had the best outcome, which is consistent with all other reports (22,23). PTCL-NOS patients had a worse prognosis than patients with AITL. Eight of 17 (47%) patients with AITL continued on to MA, as compared to only 27% of patients with PTCL-NOS. Interestingly, the majority of AITL have strong VEGF expression, both in the lymphoma cells and the benign macrophage population (24). In addition, the AITL express strong hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF1-α), which could generate hypoxic conditions and further stimulate tumor vasculogenesis through an upregulation of VEGF (24). Therefore, one can speculate that there might be a role for bevacizumab in AITL incorporating non-anthracycline based chemotherapy.

Intensifying initial therapy with autologous stem cell transplant (HDT/ASCT) in prospective studies of T-cell NHL suggests a moderately better PFS and OS than retrospective series with CHOP (25,26). However, approximately 60% of enrolled patients actually receive the planned HDT/ASCT due to progressive disease during primary chemotherapy (25). To increase the likelihood of HDT/ASCT, more effective primary therapy is needed.

SWOG 0350 reported results of the PEGS regimen (platinum, etoposide, gemcitabine, methylprednisolone) (27) with disappointing results. Recently, pralatrexate and romidepsin have been approved for relapsed PTCL, and brentuximab vedotin (BV) for relapsed ALCL (28–31). A phase I study combined BV with CHP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, prednisone) and it reported the combination to be safe and effective in ALCL (32). All three agents are being evaluated in the front line setting in combination with chemotherapy. (33–35). Early results of the romidepsin and CHOP combination reported no unexpected toxicities (36). In addition, trials are underway to evaluate the efficacy of these agents in maintenance therapy (37)

In conclusion, while the rationale for using anti-angiogenesis drugs in combination with standard therapy was strong, this approach did not improve results compared to CHOP alone and was associated with significant toxicities. The outlook for patients with PTCL remains relatively poor. Currently there is no universally accepted front-line regimen. Significant effort is required to address this ongoing unmet need.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: DISCLAIMER: The ideas and opinions expressed in the journal’s Just Accepted articles do not necessarily reflect those of Informa Healthcare (the Publisher), the Editors or the journal. The Publisher does not assume any responsibility for any injury and/or damage to persons or property arising from or related to any use of the material contained in these articles. The reader is advised to check the appropriate medical literature and the product information currently provided by the manufacturer of each drug to be administered to verify the dosages, the method and duration of administration, and contraindications. It is the responsibility of the treating physician or other health care professional, relying on his or her independent experience and knowledge of the patient, to determine drug dosages and the best treatment for the patient. Just Accepted articles have undergone full scientific review but none of the additional editorial preparation, such as copyediting, typesetting, and proofreading, as have articles published in the traditional manner. There may, therefore, be errors in Just Accepted articles that will be corrected in the final print and final online version of the article. Any use of the Just Accepted articles is subject to the express understanding that the papers have not yet gone through the full quality control process prior to publication.

References

- 1.Savage KJ, Chhanbhai M, Gascoyne RD, Connors JM. Characterization of peripheral T cell lymphomas in a single North American institution by the WHO classification. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(10):1467–1475. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swerdlow SH. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armitage JO. The aggressive peripheral T-cell lymphomas: 2012 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2012;87(5):511–519. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertolini F, Paolucci M, Peccatori F, Cinieri S, Agazzi A, Ferrucci PF, Cocorocchio E, Goldhirsch A, Martinelli G. Angiogenic growth factors and endostatin in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 1999;106(2):504–509. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salven P, Orpana A, Teerenhovi L, et al. Simultaneous elevation in the serum concentration of the angiogenic growth factors and bFGF is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a single institution study of 200 patients. Blood. 2000;96:3712–3718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gratzinger D, Zhao S, Tibshirani RJ, Hsi ED, Hans CP, Pohlman B, Bast M, Avigdor A, Schiby G, Nagler A, Byrne GE, Jr, Lossos IS, Natkunam Y. Prognostic significance of VEGF, VEGF receptors, and microvessel density in diffuse large B cell lymphoma treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Lab Invest. 2008;88:38–47. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rafii S, Lyden D, Benezra R, Hattori K, Heissig B. Vascular and haematopoietic stem cells: novel targets for anti-angiogenesis therapy? NATURE REVIEWS CANCER. 2002;2(11):826–835. doi: 10.1038/nrc925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shipp MA, Ross KN, Tamayo P, Weng AP, Kutok JL, Aguiar RC, Gaasenbeek M, Angelo M, Reich M, Pinkus GS, Ray TS, Koval MA, Last KW, Norton A, Lister TA, Mesirov J, Neuberg DS, Lander ES, Aster JC, Golub TR. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma outcome prediction by gene-expression profiling and supervised machine learning. Nat Med. 2002 Jan;8(1):68–74. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuramoto K, Sakai A, Shigemasa K, Takimoto Y, Asaoku H, Tsujimoto T, Oda K, Kimura A, Uesaka T, Watanabe H, Katoh O. High expression of MCL1 gene related to vascular endothelial growth factor is associated with poor outcome in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2002;116(1):158–161. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lenz G, Wright G, Dave SS, Xiao W, Powell J, Zhao H, Xu W, Tan B, Goldschmidt N, Iqbal J, Vose J, Bast M, Fu K, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, Armitage JO, Kyle A, May L, Gascoyne RD, Connors JM, Troen G, Holte H, Kvaloy S, Dierickx D, Verhoef G, Delabie J, Smeland EB, Jares P, Martinez A, Lopez-Guillermo A, Montserrat E, Campo E, Braziel RM, Miller TP, Rimsza LM, Cook JR, Pohlman B, Sweetenham J, Tubbs RR, Fisher RI, Hartmann E, Rosenwald A, Ott G, Muller-Hermelink HK, Wrench D, Lister TA, Jaffe ES, Wilson WH, Chan WC, Staudt LM Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project. Stromal gene signatures in B cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(22):2313–2323. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao WL, Mourah S, Mounier N, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor –A is expressed both on lymphoma cells and endothelial cell in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and related to lymphoma progression. Lab Invest. 2004;84:1512–1519. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W, Wang L, Zhou D, et al. Expression of tumor-associated macrophages and vascular endothelial growth factor correlates with poor prognosis of peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52(1):46–52. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2010.529204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, et al. Bevacizmab plus irinotecan, fluoracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(23):2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Palitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(24):2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chesen, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Onc. 1999;17(4):1244–1253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Advani RH, Hong F, Horning SJ, et al. Cardiac Toxicity Associated with Bevacizumab (Avastin) in Combination with CHOP Chemotherapy for Peripheral T Cell Lymphoma in ECOG 2404 Trial. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53(4):718–720. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.623256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Leval L, Rickman DS, Thielen C, Reynies Ad, Huang YL, Delsol G, Lamant L, Leroy K, Brière J, Molina T, Berger F, Gisselbrecht C, Xerri L, Gaulard P. The gene expression profile of nodal peripheral T-cell lymphoma demonstrates a molecular link between angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) and follicular helper T (TFH) cells. Blood. 2007;109(11):4952–4963. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-055145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganjoo KN, An CS, Robertson MJ, et al. Rituximab, bevacizumab and CHOP (RE-CHOP) in untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Safety, biomarker and pharmacokinetic analysis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47(6):998–1005. doi: 10.1080/10428190600563821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stopeck AT, Unger JM, Rimsza LM, Leblanc M, Farnsworth B, Iannone M, Glenn MJ, Fisher RI, Miller TP. A phase II trial of standard dose cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (CHOP) and rituximab plus bevacizumab for patients with newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: SWOG 0515. Blood. 2012 Jun 25; doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-423079. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seymour JF, Pfreundshuh M, Coiffier B, Trneny M, Sehn LH, Csinady E. The Addition of Bevacizumab to Standard Therapy with R-CHOP in Patients with Previously Untreated Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Is Associated with an Increased Rate of Cardiac Adverse Events: Final Analysis of Safety and Efficacy Outcomes From the Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 MAIN Study. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2012 Nov;120:58. [Google Scholar]

- 21.AbouYabis AN, Shenoy PJ, Sinha R, Flowers CR, Lechowicz MJ. A Systematic Review and meta-analysis of front-line anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimens for Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma. ISRN Hematol. 2011;2011:623924. doi: 10.5402/2011/623924. Published online 2011 June 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmitz N, Trumper L, Ziepert M, et al. Treatment and prognosis of mature T-cell and NK-cell lymphoma: an analysis of patients with T-cell lymphoma treated in studies of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2010;116:3418–3425. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niitsu N, Hayama M, Yoshino T, Nakamura S, Tamaru JI, Nakamine H, Okamoto M. Multicentre phase II study of the CyclOBEAP regimen for patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma with analysis of biomarkers. Br J Haemotology. 2010;153:582–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stewart M, Talks K, Leek R, et al. Expression of angiogenic factors and hypoxia inducible factors HIF 1, HIF 2 and CA IX in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Histopathology. 2002;40:253–260. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reimer P, Rudiger T, Geissinger E, Weissinger F, Nerl C, Schmitz N, Engert A, Einsele H, Muller-Hermelink HK, Wilhelm M. Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation as first-line therapy in peripheral T-cell lymphomas: Results of a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:106–113. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.4870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.d'Amore F, Relander T, Lauritzsen GF, Jantunen E, Hagberg H, Anderson H, Holte H, Österborg A, Merup M, Brown P, Kuittinen O, Erlanson M, Østenstad B, Fagerli UM, Gadeberg VO, Sundström C, Delabie J, Ralfkiaer E, Vornanen M, Toldbod HE. Up-Front Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation in Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma: NLG-T-01. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(25):3093–3099. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahadevan D, Unger JM, Spier CM, Persky DO, Young F, LeBlanc M, Fisher RI, Miller TP. Phase 2 trial of combined cisplatin, etoposide, gemcitabine, and methylprednisolone (PEGS) in peripheral T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1002/cncr.27733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Connor OA, Pro B, Pinter-Brown L, Bartlett N, Popplewell L, Coiffier B, Lechowicz MJ, Savage KJ, Shustov AR, Gisselbrecht C, Jacobsen E, Zinzani PL, Furman R, Goy A, Haioun C, Crump M, Zain JM, His E, Boyd A, Horwitz S. Pralatrexate in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma: Results From the Pivotal PROPEL Study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(9):1182–1189. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.9024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coiffier C, Pro B, Prince HM, Foss FM, Sokol L, Greenwood M, Caballero D, Borchmann P, Morschhauser F, Wilhelm M, Pinter-Brown L, Padmanabhan S, Shustov A, Nichols J, Carroll S, Balser J, Horwitz SM. Final Results From a Pivotal, Multicenter, International, Open-Label, Phase 2 Study of Romidepsin In Progressive or Relapsed Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma (PTCL) Following Prior Systemic Therapy. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2010 Nov;116:114. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piekarz R, Wright J, Frye R, Allen SL, Joske D, Kirschbaum M, Lewis ID, Prince M, Smith S, Jaffe ES, Bates S. Final Results of a Phase 2 NCI Multicenter Study of Romidepsin in Patients with Relapsed Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma (PTCL) Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2009 Nov;114:1657. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pro B, Advani R, Brice P, Bartlett NL, Rosenblatt JD, Illidge T, Matous J, Ramchandren R, Fanale M, Connors JM, Yang Y, Sievers EL, Kennedy DA, Shustov A. Brentuximab Vedotin (SGN-35) in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Systemic Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma: Results of a Phase II Study. JCO. 2012;30(18):2190–2196. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fanale MA, Shustov AR, Forero-Torres A, Bartlett NL, Advani RH, Pro B, Chen RW, Davies A, Illidge T, Kennedy DA, Horwitz SM. Brentuximab Vedotin Administered Concurrently with Multi-Agent Chemotherapy As Frontline Treatment of ALCL and Other CD30-Positive Mature T-Cell and NK-Cell Lymphomas. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2012 Nov;120:60. [Google Scholar]

- 34.A Phase II Study of Cyclophosphamide, Etoposide, Vincristine and Prednisone (CEOP) Alternating With Pralatrexate (P) as Front Line Therapy for Patients With Stage II, III and IV Peripheral T-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma ( NCT01336933) [Google Scholar]

- 35.A Study of Escalating Doses of Romidepsin in Association With CHOP in the Treatment of Peripheral T-Cell Lymphomas ( NCT01280526) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brentuximab Vedotin and Bendamustine for the Treatment of Hodgkin Lymphoma and Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL) ( NCT01657331) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dupuis J, Casasnovas RO, Morschhauser F, Ghesquieres H, Thieblemont C, Ribrag V, Tilly H, Coiffier B. Early Results of a Phase Ib/II Dose-Escalation Trial of Romidepsin in Association with CHOP in Patients with Peripheral T-Cell Lymphomas (PTCL) Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2011 Nov;118:2673. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Study of Pralatrexate Versus Observation Following CHOP-based Chemotherapy in Previously Undiagnosed Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Patients ( NCT01420679) [Google Scholar]