Abstract

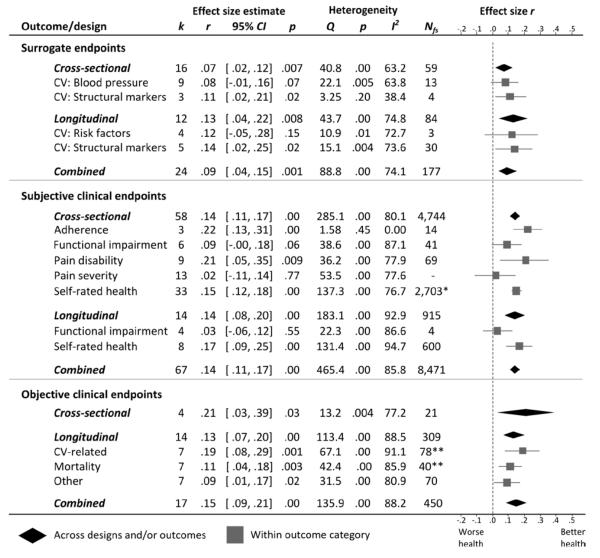

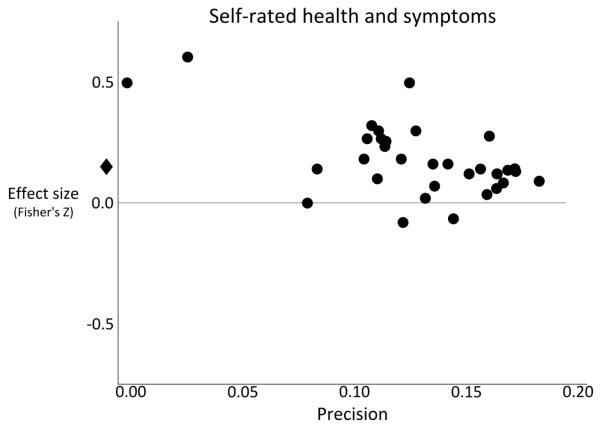

This meta-analysis reviewed 126 published empirical articles over the past 50 years describing associations between marital relationship quality and physical health in over 72,000 individuals. Health outcomes included clinical endpoints (objective assessments of function, disease severity, and mortality; subjective health assessments) and surrogate endpoints (biological markers that substitute for clinical endpoints, such as blood pressure). Biological mediators included cardiovascular reactivity and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity. Greater marital quality was related to better health, with mean effect sizes from r = .07 to .21, including lower risk of mortality, r = .11, and lower cardiovascular reactivity during marital conflict, r = −.13, but not daily cortisol slopes or cortisol reactivity during conflict. The small effect sizes were similar in magnitude to previously found associations between health behaviors (e.g., diet) and health outcomes. Effect sizes for a small subset of clinical outcomes were susceptible to publication bias. In some studies, effect sizes remained significant after accounting for confounds such as age and socioeconomic status. Studies with a higher proportion of women in the sample demonstrated larger effect sizes, but we found little evidence for gender differences in studies that explicitly tested gender moderation, with the exception of surrogate endpoint studies. Our conclusions are limited by small numbers of studies for specific health outcomes, unexplained heterogeneity, and designs that limit causal inferences. These findings highlight the need to explicitly test affective, health behavior, and biological mechanisms in future research, and focus on moderating factors that may alter the relationship between marital quality and health.

Keywords: marriage, marital quality, health, morbidity, mortality, meta-analysis

The link between “better” or “worse” marriages and “sickness and health” has been a subject of much empirical interest over the last half-century. During this period, marriage went through considerable sociodemographic transformations, including a declining marriage rate, increasing age of first marriage, increasing divorce rates during the 1960s and 1970s, and increasing cohabitation and same-sex marriage (Cherlin, 2010; Lee & Payne, 2010). The cultural meaning of marriage also went through “deinstitutionalization,” where marriage based on companionship through mutual social obligations and roles transitioned to a greater emphasis on personal choice and self-fulfillment (Cherlin, 2004).

In spite of the changes in the demographics and meanings of marriage, the impact of having a better or worse marriage – marital quality – on physical well-being has remained a topic of consistent interest among scholars, practitioners, and the public. Marital quality is defined as a global evaluation of the marriage along several dimensions (Fincham & Bradbury, 1987), including positive and negative aspects of marriage (e.g., support and strain; Burman & Margolin, 1992; Fincham, Beach, & Kemp-Fincham, 1997; Slatcher, 2010), attitudes, and reports of behaviors and interaction patterns (Bradbury, Fincham, & Beach, 2000). Thus, high marital quality is typically operationally defined by high self-reported satisfaction with the relationship, predominantly positive attitudes towards one’s partner, and low levels of hostile and negative behavior. Low marital quality is characterized by low satisfaction, predominantly negative attitudes towards one’s partner, and high levels of hostile and negative behavior. A narrative synthesis of research up to the early 1990s concluded that “marital variables affect health problems” (Burman & Margolin, 1992, p. 56). An updated review echoed the same conclusion and described research during the 1990s on biological mechanisms that could explain the “ample evidence that intimate relationships can impact illness processes or outcomes…” (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001, p. 487).

Since the publication of those reviews, technological advances in measuring objective biological markers led to empirical advances in understanding marital functioning and health outcomes during the 2000s, including studies of ambulatory blood pressure, cardiovascular disease progression, and wound healing. Such methods were simply unavailable in previous decades. Beyond providing an updated picture of the past decade of research of marital quality and health research given these technological improvements, our overall goal is to conduct the first meta-analysis of the association between marital quality and health outcomes spanning the entire published literature of the past 50 years. In doing so, we aim to quantify the magnitude of the association between marital quality and health, which allows for comparing marital functioning to other established health-related risk factors, particularly health behaviors, and address substantive theoretical concerns and methodological issues in the existing literature. We begin by describing the state of theory on marital quality and health.

Explanatory theories

The connection between marital quality and health is part of a larger body of research that has consistently demonstrated robust links between social relationships and physical health (for reviews, see Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000; House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988; Uchino, 2009). A recent meta-analysis across 148 studies indicated a 50% greater likelihood of survival for participants with stronger social relationships (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010). Indeed, social support has been called “one of the most well-documented psychological factors influencing physical health outcomes” (Uchino, 2009, p. 236).

Two main types of models have been proposed to explain how social support influences physical health. In main-effect models, high levels of social integration are health promoting, regardless of whether or not one is under stress (Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000; S. Cohen, 2004; S. Cohen & Wills, 1985). Greater integration into one’s social network gives an individual identity, purpose, and control, a perceived sense of security and embeddedness, and a source of reinforcement for health-promoting behaviors or punishment for health-compromising behaviors, all of which can promote health (Thoits, 2011). In the stress-buffering model (Cohen & Wills, 1985), the negative effects of stress occurring outside of one’s social relationships (e.g., at work) are diminished by the presence of strong social support, which can mitigate stressful events directly (e.g., intervening on a friend’s behalf) or through reducing stress appraisals (Uchino, 2004). In both models, close personal relationships such as marriage should be a key roles source of social support.

Surprisingly, although many studies have investigated the links between measures of social support and health, and other studies have examined marital processes and health, virtually no studies have compared whether marriage confers special benefits above and beyond other long-term, committed, non-cohabitating social relationships in one’s social network. That said, marital relationship quality may have greater bearing on health relative to support and strain from other social network members for several reasons. Relative to non-cohabiting social network members (friends, co-workers) individuals in long-term romantic relationships such as marriage share the same space and time on a daily basis, co-participating in a wide variety of activities that include meals, leisure activities, domestic chores, child care, and sleep. Married spouses also share financial and other tangible resources (Carr & Springer, 2010) to a degree that is often larger relative to other cohabiting family members or friends. Likewise, married individuals are on average more committed and make more joint investments (specialization of labor, shared finances, children, home ownership) relative to cohabiting romantic partners or dating partners (Brines & Joyner, 1999). Thus, sharing of space, time, resources, and investments creates unique arenas for both support and conflict.

Changes in marriage: Implications for theory

The increased prevalence of nonmarital cohabitation in industrialized countries (Heuveline & Timberlake, 2004) may complicate existing theories explaining the benefits of marriage for health. However, research on cohabitation and its implications for health and well-being is in its infancy. The prevailing view is that cohabitation is associated with greater advantages for well-being relative to being nonpartnered, but fewer economic, psychological, and health benefits relative to being married (Carr & Springer, 2010; Liu & Reczek, 2012). At the same time, “cohabiting” is a heterogeneous category in terms of reasons for living together (e.g., as a prelude to eventual marriage or not), and because sociodemographic factors and selection effects that are associated with cohabitation (described later when we discuss marital status) also modify the association between cohabitation and health. Indeed, the effects of cohabitation relative to being married on mortality vary by ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES), age, gender, and their interactions (Liu & Reczek, 2012). Moreover, data on the link between relationship quality and health outcomes, which is the pertinent question for this review, and whether it differs between married and cohabitating individuals is lacking. That said, we expect that in committed relationships (married or not), the quality of the relationship should be related to physical well-being.

Despite sociodemographic shifts away from marriage in industrialized countries (Fincham & Beach, 2010; Pew Research Center, 2010; United States Census Bureau, 2010), marriage continues to play an integral role in our social networks, even in comparison to other social relationships. In most countries, the proportion of individuals reporting that they were “ever married” is over 90% during the adult years (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2009). Thus, marriage has understandably received much attention from researchers interested in close relationships and health.

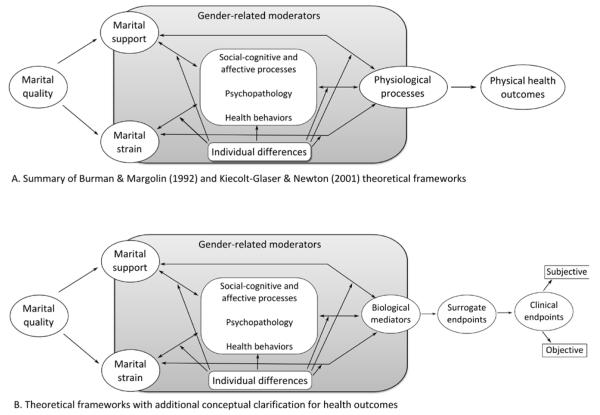

The existing theories explaining the relationship between marital quality and health are summarized in Figure 1A (Burman & Margolin, 1992; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001; Slatcher, 2010). Below, we briefly review our conceptual understanding of health, explanatory mediators, and moderators in existing theories.

Figure 1.

Summary of conceptual models explaining links between marital quality and health

Defining “health”

A key issue for theory is how to effectively differentiate physiological pathways from indicators of physical health outcomes (termed “health status” by Burman & Margolin, 1992; and “functional status and pathophysiology” by Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001). The issue is especially important due to increased use of objective indicators of normal or pathological biological processes, referred to as biomarkers (Biomarker Definitions Working Group, 2001), in biobehavioral research over the past decade. For example, structural markers of cardiovascular function that actually quantify atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries that causes later cardiovascular disease) came into regular use in biobehavioral research beginning in the late 1990s and early 2000s (Barnett, Spence, Manuck, & Jennings, 1997; Trieber et al., 2003). To what degree do those biomarkers actually reflect what health care providers and policymakers consider indicators of “health”? The answer to this question provides a guiding framework for this review.

The National Institutes of Health established an expert working group to propose terms and definitions to help guide research, clinical applications, and regulatory policy (Biomarker Definitions Working Group, 2001). Besides defining the term “biomarker” (described in the previous paragraph), the working group created a key definition that we consider the starting point for measuring “health”: Clinical endpoints. Defined as a “…characteristic or variable that reflects how a patient feels, functions, or survives” (Biomarker Definitions Working Group, 2001, p. 91), clinical endpoints are considered “the most credible characteristics used in the assessment of the benefits and risks of a therapeutic intervention in randomized clinical trials” (Biomarker Definitions Working Group, 2001, p. 91). For example, clinical endpoints may include occurrence of a heart attack, hospitalization due to a medical condition, or changes in quality-of-life or activities of daily living. Such observable endpoints would typically be recognized as important outcomes by patients and health care providers.

Clinical endpoints were distinguished from surrogate endpoints, defined as “A biomarker that is intended to substitute for a clinical endpoint…[that] is expected to predict clinical benefit (or harm…) based on epidemiologic, therapeutic, pathophysiologic, or other scientific evidence” (Biomarker Definitions Working Group, 2001, p. 91). Examples include low-density cholesterol levels or blood pressure (Psaty et al., 1999), which predict later cardiovascular disease endpoints (e.g., coronary artery disease, stroke), but may not have value for assessing how a patient currently feels, functions, or survives because they reflect early events in the causal chain (Temple, 1999). Surrogate endpoints covered in this review are described in Table 1. The distinction between clinical and surrogate endpoints is both conceptually and practically useful. For example, the United States Food and Drug Administration regulations of therapeutic agents allow for approval based on evidence of efficacy using surrogate endpoints.

Table 1.

Definitions of Surrogate Endpoints used in Cited Studies

| Endpoint category/endpoint | Definition |

|---|---|

| Functional cardiovascular markers | Abnormalities in the performance of the cardiovascular system (Cohn, Quyyumi, Hollenberg, & Jamerson, 2004). |

| Resting blood pressure | Product of the volume of blood expelled by the heart (cardiac output) during contraction (systole) or rest (diastole), and the amount of resistance against blood flow in the arteries that must be overcome to circulate blood (Gerin, Goyal, Mostofsky, & Shimbo, 2008). High blood pressure is strongly related to future cardiovascular risk. Typically measured in the office or laboratory setting using auscultatory (listening for sounds within the artery, in combination with a mercury sphygmomanometer) or oscillometric methods. |

| Ambulatory blood pressure | Automated blood pressure monitoring coupled with a portable device that allows monitoring in naturalistic environments (Janicki-Deverts & Kamarck, 2008). |

| Structural cardiovascular markers | Abnormalities in the framework of cells and tissues (evidence summarized in G. B. J. Mancini, Dahlof, & Diez, 2004). Several markers are strong predictors of future cardiovascular disease- related events (e.g., heart attack, stroke, death) |

| Carotid artery intima media thickness |

The thickness of the innermost layers of the prominent arteries in the neck (carotid), measured using ultrasound. Greater thickness indicates greater degree of atherosclerosis. |

| Coronary artery calcification | Degree of calcium deposition within the lining of the coronary artery (which supplies the heart) as part of a plaque accumulation of cells, debris, cholesterol, and lipids – the core pathology in cardiovascular disease). Imaged using electron-beam computed tomography. |

| Carotid plaque | Discrete enlarged areas within the carotid artery (as opposed to overall thickness of the artery wall) identified using ultrasound. Greater plaque score indicates greater degree of atherosclerosis. |

| Coronary artery luminal diameter | Diameter of the space inside the coronary artery, obtained through angiography. Smaller diameter indicates greater degree of atherosclerosis. |

| Left ventricular mass index | Thickening of heart muscle surrounding the left ventricle of the heart. Commonly observed in hypertension and a sign of early cardiovascular disease. Measured by electrocardiogram or echocardiogram (cardiac ultrasound). A related measure is relative wall thickness. |

| Other endpoints | |

| Body mass index | Proxy for body fat calculated by dividing an individual’s weight (kg) by height (m2) (Melmed, Polonsky, Larsen, & Kronenberg, 2011). |

| Glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) |

Measured in blood. High values indicate a poor ability to control glucose levels over a three-month period (Melmed, Polonsky, Larsen, & Kronenberg, 2011). |

| Antibody titers to influenza virus vaccine |

Protein produced by B-cells that binds to and neutralizes components of the influenza virus vaccine (Prather & Marsland, 2008). “Titer” refers to how antibodies are quantified. Higher titers related to better protection conferred by the vaccine. |

| Metabolic syndrome indices | Cluster of factors that increase risk for cardiovascular disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes, including three or more of the following: High blood pressure, high fasting blood glucose, elevated waist circumference, low high density lipoprotein cholesterol, high triglyceride levels (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0004546/) |

| Observed signs of orofacial hypokinesia in Parkinson’s patients |

Indicators of motor slowing in the face and mouth, including reduced rates of speech, eye blinks, and longer duration of eye blinks. Slowed speech included in common rating scale assessments of Parkinson’s disease symptoms (Ramaker, Marinus, Stiggelbout, & van Hilten, 2002). |

Biomarkers that are not considered surrogate endpoints can be described as measures of biological mediators (Miller, Chen, & Cole, 2009), which include allostatic biological processes that change in response to short-term environmental demands like marital conflict discussions (McEwen, 1998; Robles & Carroll, 2011; Robles & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2003) and restorative biological processes that respond after short-term environmental demands have ceased (such as tissue growth and energy storage; Robles & Carroll, 2011). Most studies of marital quality and biological mediators have focused on allostatic processes: Acute changes in stress-related hormones and immune measures. While related in theory to clinical endpoints, such biological mediators do not have a sufficient evidence base to be elevated to surrogate endpoint status (Kiecolt-Glaser, Cacioppo, Malarkey, & Glaser, 1992), which requires rigorous evaluation and validation studies (described in Manolio, 2003). Figure 1B represents the incorporation of those key distinctions into the overall model, where biological mediators, surrogate endpoints, and clinical endpoints replace the concepts of physiological processes and health outcomes.

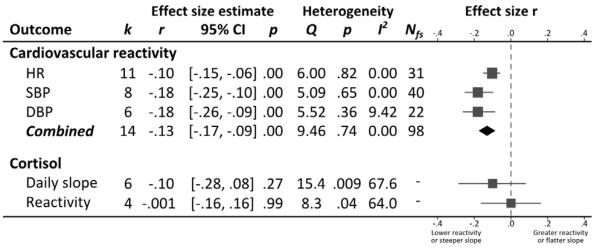

In this review, we examine the relationship between marital quality and the two endpoint categories (clinical and surrogate endpoints). We further subdivide clinical endpoints into subjective clinical endpoints that are reported by participants and patients, including self-rated health (physical health-related quality-of-life), physical symptoms, pain severity, and functional impairment; and objective clinical endpoints that are objectively measured and reflect patient functioning, including mortality. In a separate meta-analysis, we examine the relationship between marital quality and several frequently studied biological mediators1: Cardiovascular reactivity during laboratory-based conflict discussions, daily cortisol slopes in naturalistic studies, and cortisol responses to laboratory-based conflict discussions.

What explains the relationship between marital quality and health?

One of the major challenges to understanding the relationship between marital functioning and health is the direction of causality. Unhappy relationships may contribute to poorer health; on the other hand, chronic medical conditions, or factors that predispose an individual to poorer health, may act as enduring vulnerabilities that contribute to declines in marital satisfaction (Karney & Bradbury, 1995). A key way to address direction of causality is through prospective, longitudinal research designs (Kraemer et al., 1997; Robles & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2003). Moreover, as described by Burman and Margolin (1992) and summarized by Kiecolt-Glaser and Newton (2001): “…the most convincing way to document a causal relationship between marital functioning and health status would be first to confirm that marital interaction had direct effects on physiological processes and then to show that individuals who exhibited physiological changes were more likely to develop health problems…” (p. 491). Prevailing theories proposed several explanatory mediators, shown in Figure 1 and described below. While our descriptions primarily focus on how marital conflict is related to poor health, the same basic mechanisms likely explain how marital support is related to better health.

Social-cognitive and affective processes

How people in happy compared to unhappy marriages think about relationships may play an important mediating role in the links between marital quality and physical health. For example, people in unhappy marriages often attribute responsibility for negative behaviors to their partner (e.g., “Don came home late because he doesn’t care about his family”), while not attributing responsibility for positive behaviors to the partner (e.g., “Don came home early because his boss told him to do so”) (Bradbury, Beach, Fincham, & Nelson, 1996; Durtschi, Fincham, Cui, Lorenz, & Conger, 2011). Similarly, a “criticality bias” to misattribute a partner’s verbal and nonverbal communication as criticism (Smith & Peterson, 2008) is also associated with expressing criticism towards partners, using a negative tone in conversations, and greater “demanding” behaviors (Peterson, Smith, & Windle, 2009). While the specific role of social-cognitive processes in physical health remains understudied, attributing responsibility to the partner for negative behaviors predicted slower cortisol recovery following a conflict discussion in dating couples (Laurent & Powers, 2006).

Emotion regulation in couple interactions is also viewed as a key factor in links between marital quality and health (Burman & Margolin, 1992; Snyder, Simpson, & Hughes, 2006). Distressed couples show greater negative affect, particularly hostility, and escalation of negative affect during conversations with partners (Heyman, 2001). Greater displays of negative affect are related to biological mediators discussed below, including cardiovascular and neuroendocrine reactivity (Robles & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2003). On the other hand, emotional disclosure, which often occurs in the context of marital relationships (Laurenceau, Barrett, & Rovine, 2005), confers an array of physical health benefits, such as decreased work absenteeism and physician visits, which are attributed to changes in psychological well-being and biological mediators, particularly immune function (Frattaroli, 2006; Smyth, 1998). Coupled with findings suggesting that couples with a higher marital distress are less skillful in emotional disclosure (Cordova, Gee, & Warren, 2005; Mirgain & Cordova, 2007), limited emotional expression might mediate links between marital satisfaction and physical health.

Bidirectional associations with psychopathology

Marital distress has both concurrent and longitudinal associations with psychological distress (Proulx, Helms, & Buehler, 2007). In addition, marital problems predict the onset of psychopathology, including mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders (see Whisman & Baucom, 2012, for a review). Of those conditions, depression has received the most empirical attention; three decades of research clearly show a reliable, bidirectional association between depression and marital discord (Beach, Fincham, & Katz, 1998; Fincham & Beach, 1999) with moderate effect sizes (Whisman, 2001). In one direction, marital distress in combination with established diatheses (Hammen, 2005) increases risk for depression. In the other direction, depression is associated with affective dysregulation and cognitive biases (Gotlib & Joormann, 2010), all of which may filter into marital interactions. For example, conversations where one or both partners suffer from depression are characterized by high amounts of negative behaviors and affect alongside a low frequency of positive behaviors and affect (Rehman, Gollan, & Mortimer, 2008). Moreover, depressive behaviors such as excessive reassurance-seeking may be viewed as burdensome to the partner (Benazon & Coyne, 2000), who can react with criticism and rejection (Coyne, 1976).

Regardless of directionality between marital quality and depression, the link between depression and physical health is well-established (Kiecolt-Glaser, McGuire, Robles, & Glaser, 2002). Symptoms like lack of motivation and fatigue may promote maladaptive health behaviors (i.e., sedentary behavior, poor diet and sleep, increased substance use). Depression is also associated with immune dysregulation (described below). Taken together, poor marital quality predicts subsequent depressive symptoms or diagnoses, which themselves are associated with emotion dysregulation and cognitive biases that may enhance marital dissatisfaction and promote further depression and concomitant poor physical health. Thus, our focus on depression as a psychopathology-related mediator of the relationship between marital quality and physical health is based in part on the significant amount of prior empirical work. In addition, depression was examined most frequently in the studies included in our meta-analysis.

Importantly, while there is a clear bidirectional relationship between stressful life events and episodes of major depression (Hammen, 2005) emerging research has indicated that stress generation (the propensity for depression to “create” subsequent interpersonal stressors) can occur in other psychological disorders beyond depression (Daley, Hammen, Davila, & Burge, 1998; Hammen & Shih, 2008). Indeed, other psychological conditions (i.e. anxiety, personality, substance use disorders) may be additional or comorbid explanatory mediators (Whisman & Baucom, 2012). Finally, interpersonal dysfunction in intimate relationships clearly occurs even among individuals without current depressive symptoms (Hammen & Brennan, 2002), and with sufficient duration can be a chronic stressor with the potential for long-term effects on physical health through the pathways described below (Robles & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2003), even in the absence of psychopathology.

Health behaviors

Marriage is a key context for efforts to change health-compromising behaviors (e.g., substance use, nonadherence) and initiate and maintain health-enhancing behaviors (e.g., physical activity, diet, adherence). Being married contributes to concordance in health behaviors over time between spouses (Homish & Leonard, 2008; Meyler, Stimpson, & Peek, 2007). One explanation is modeling, and another is the ways in which spouses exert social influence or control over health behaviors (Lewis & Butterfield, 2007; Lewis & Rook, 1999), which may be a key mechanism explaining how marital quality influences health behaviors more generally. For instance, positive control behaviors such as modeling a behavior were related to greater intentions to change health behaviors (in a health-promoting direction), whereas negative control behaviors, such as inducing fear, had no effect on intentions (Lewis & Butterfield, 2007). Importantly, social control attempts may be more successful against a backdrop of a satisfying compared to a distressed relationship (Tucker, 2002). Moreover, marital support may also buffer against the impact of non-marital stressors on health behaviors and increase personal resources (i.e., self-efficacy, self-regulatory capacity) needed for initiating and maintaining health behavior change (DiMatteo, 2004). Marital strain may add or interact with non-marital stressors leading to increased use of health-compromising behaviors to cope with such stressors, and decreasing personal resources that could be used during change attempts. For example, couples reporting higher marital conflict and/or lower marital satisfaction are at greater risk for future alcohol problems (Whisman, Uebelacker, & Bruce, 2006). In addition, couples seeking treatment for substance dependence have better outcomes when they are in high quality relationships (Heinz, Wu, Witkiewitz, Epstein, & Preston, 2009).

Biological mediators

Among the many plausible biological mediators of the link between marital quality and health, allostatic processes that respond during physical or psychological challenges (Robles & Carroll, 2011) have received the most attention in the marital literature (Robles & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2003). Key allostatic processes involve the cardiovascular, neuroendocrine, and immune systems, and dysregulation in those systems is implicated in the deleterious health effects of chronic stress (McEwen, 1998).

Cardiovascular reactivity

Individuals with greater cardiovascular reactivity to stress are at greater risk for future cardiovascular disease and faster disease progression (Linden, Gerin, & Davidson, 2003; Trieber et al., 2003). Some of the earliest studies demonstrating that interpersonal conflict and attempts to influence another person could evoke cardiovascular responses involved married couples (Smith & Brown, 1991; Ewart et al., 1991). Couples who show greater hostile behavior during marital discussions have elevated blood pressure and heart rate compared to less hostile couples (reviewed in Robles & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2003). Thus, cardiovascular reactivity to marital interactions is a likely mediator of the relationship between marital quality and cardiovascular health.

Neuroendocrine pathways

The primary neuroendocrine pathways of interest include the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary axis (SAM) and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA; Robles & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2003). The hormones produced by both axes have wide-ranging effects across the body, and are considered key mediators of the association between psychological factors and physical health (McEwen, 1998). The SAM axis can be indexed indirectly by measuring cardiovascular reactivity and directly through circulating catecholamines (norepinephrine, epinephrine). Greater negative behavior during marital interactions has been related to elevated catecholamine levels during and after conflict discussions in both newlywed (Malarkey et al., 1994) and older adult couples (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1997)2.

In contrast to the SAM axis, the HPA axis has received significant empirical attention in the past decade, and sufficient numbers of studies were available to review. Our meta-analysis focused on the diurnal slope of cortisol and cortisol responses to marital conflict discussions. Diurnal cortisol slopes are of particular interest because of research linking daily cortisol measurements to surrogate markers (Matthews, Schwartz, Cohen, & Seeman, 2006), and clinical endpoints related to cardiovascular disease (Kumari, Shipley, Staffod, & Kivimaki, 2011).

Immune pathways

Due to its role in responding to infection and injury, the immune system received attention in early studies of marital functioning and biological processes (Kiecolt-Glaser, Fisher, Ogrocki et al., 1987; Kiecolt-Glaser, Kennedy, Malkoff et al., 1988). Comprehensive narrative reviews are available elsewhere (Robles & Kane, 2012; Robles & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2003), so we briefly summarize the findings here. Couples who showed greater hostile behavior during marital conflict, and higher levels of hostility in men, showed greater acute increases in the activity of natural killer cells (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1993; G. E. Miller, Dopp, Myers, Stevens, & Fahey, 1999), which play key roles in immediate responses to viral infection by killing virally-infected cells in the body. In addition, social rejection (potentially from one’s partner) contributes to inflammation (Slavich, O’Donovan, Epel, & Kemeny, 2010) which is the body’s immediate response to injury and infection. Chronic and persistent inflammation contributes to accumulating damage in tissues that surround sites of chronic infection, and has been implicated as a central mechanism explaining how psychosocial factors can contribute to chronic disease, including atherosclerosis and cancer (Miller, Chen, & Cole, 2009; Robles, Glaser, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005). In the context of marriage, higher levels of hostile behaviors during conflict were related to larger increases in circulating markers of inflammation (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2005). Moreover, recent work in a large national sample similarly found that low marital satisfaction was related to elevated inflammation (Whisman & Sbarra, 2012). Moving beyond immediate responses to infection, marital functioning is related to slower-acting yet highly specific immune responses (known as adaptive immunity). For example, low marital satisfaction and greater hostility during marital conflict were related to poorer ability to control Epstein-Barr Virus, a latent herpesvirus that infects most adults (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1997; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1988; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1993). In sum, poorer marital functioning, assessed through self-reports and behavioral data, shows associations with immunity that are similar to the effects of chronic stressful life events, consistent with previous conceptualizations of marital strain as a chronic stressor (Robles & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2003).

The state of mediating mechanisms

Despite suggestive evidence for each set of mediating pathways, no studies have firmly established that the association between marital quality and health outcomes is attenuated when including mediating variables that precede the health outcome in time. That said, many studies examine associations between marital quality and health outcomes before and after adjusting for other intervening variables. A quantitative estimate of associations between marital quality and health before and after adjusting for such covariates may provide an initial window into determining whether the candidate mediators of interest in Figure 1 truly serve as mediating variables.

For whom might marital quality and health matter?

The model in Figure 1 also suggests that links between marital quality and health may vary by different groups of individuals or couples, and existing theory highlights two primary moderators of interest: Gender, and personality characteristics related to negative affect including neuroticism and hostility (Suls & Bunde, 2005). Unfortunately, few studies included negative affectivity as predictors alongside marital quality, and none examined such personality characteristics as moderators. Thus, this review focuses on gender and gender-related moderators.

The effects of marital functioning on physiology may be stronger for women compared to men (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001; Wanic & Kulik, 2011a). One explanation is that several gender-related factors contribute to women being more aware of and responsive to the affective quality of relational interactions, and spending more time thinking about relationships (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001). Gender-related factors include: Self-representations that guide cognitions and behavior; traits that focus on the degree to which individuals focus and attend to others (communion) with the potential exclusion of the self (e.g., unmitigated communion, sociotropy); and roles in domestic labor and childcare. As a consequence, women’s goals and the ways they control their thoughts, feelings, and behavior may be influenced by their close relationships more so than men (Cross & Madson, 1997). Given that the personal relevance of stressful events plays an important role in modulating affective and biological responses to stressors (Lazarus, 1993), this interpersonal-orientation hypothesis (Wanic & Kulik, 2011a) predicts that since close relationships are more personally relevant to women compared to men, women should show greater physiological responses to stressors within the intimate relationship.

Wanic and Kulik (2011a) recently suggested a subordinate-reactivity hypothesis: That the gender difference in associations between marital functioning and physiology may be due to women’s relative subordinate position in marriage. Specifically, the relative social status of women as a whole in society, the interpersonal-orientation characteristics described in the previous paragraph, and economic and domestic labor-related power differentials within the marriage itself all contribute to wives having less power (on average) in the relationship. Coupled with data suggesting that lower status humans and primates have greater stress reactivity, the authors proposed that the subordinate-reactivity hypothesis may be a more comprehensive account of existing data (Wanic & Kulik, 2011b).

Both hypotheses emphasize the importance of factors that are strongly, but not exclusively related to biological sex, due to the combination of biological characteristics (i.e., women’s exclusive childbearing and nursing abilities) and social, economic, and ecological contexts (Wood & Eagly, 2002). Unfortunately, virtually all empirical research on marital functioning and health thus far has focused on sex differences, rather than the gender-related characteristics in both the interpersonal-orientation and subordinate-reactivity hypotheses. Thus, our meta-analysis is limited in the degree to which we can address either hypothesis; however, as discussed in the Method section, we make several attempts to consider the impact of gender and gender inequality as moderators.

What is not the focus of the meta-analysis?

This paper does not examine the association between marital status and health. The mechanisms by which marital status may influence health are distinct from those by which marital quality may influence health. The primary explanations for marital status effects include selection (individuals with better health and protective factors associated with better health may be more likely to get married/stay married), resources afforded by marriage (marriage affords access to joint economic, psychosocial, and societal benefits that are not available to unmarried individuals), and stress associated with marital disruption (divorce, separation, or widowhood are stressful events, and as a result may lead to poorer health outcomes; Sbarra, Law, & Portley, 2011; Stroebe, Schut, & Stroebe, 2007; see Liu & Umberson, 2008 for further elaboration on these explanations). While some explanations overlap, such as resources and stress associated with marital disruption, they are still distinct (e.g., lower social support resources due to a low quality marriage may have a different impact than lower social support due to the absence of a partner). Moreover, the explanations for why being married has benefits for health may have less to do with the effects of being married, and more to do with the effects of not being married (such as selection effects, loss of resources, and increased stress related to divorce, separation, or widowhood). Overall, the association between marital status and health is beyond the scope of the current review, but a quantitative review is certainly warranted.

Primary research aims

Our overall goals are to quantify, through meta-analysis, 1) the relationship between marital quality and health outcomes (surrogate endpoints, subjective clinical endpoints, and objective clinical endpoints), and 2) the relationship between marital quality and two commonly studied biological mediators: Cardiovascular reactivity and HPA axis function. We also examined several theory-based and methodology-related moderators of the expected heterogeneity in effect sizes between studies. To provide a preliminary assessment of the degree to which mediating pathways accounted for links between marital quality and health, we examined the changes in effect sizes for unadjusted and adjusted analyses.

Method

Search strategy

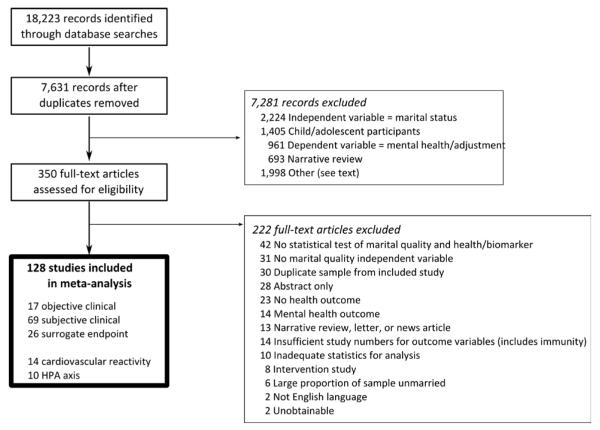

Electronic searches were performed in PsycINFO (1806 – 2011), PubMed (1946 – 2011), and Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded, 1899 – 2011; Social Sciences Citation Index, 1900 – 2011; Arts & Humanities Citation Index, 1975 – 2011) with final searches completed by December 26, 2011. The main search strategy used combinations of keywords for marital quality (marriage OR marital quality OR marital satisfaction OR marital adjustment OR marital conflict OR marital support) and health (disease OR risk OR diagnosis OR health OR surrogate marker OR clinical endpoint OR quality-of-life OR self-rated health OR morbidity OR cancer OR cardiovascular disease OR symptoms OR illness OR cardiovascular reactivity OR neuroendocrine OR HPA OR cortisol OR blood pressure OR heart rate OR pain OR mortality). In addition, we cross-referenced our search with articles cited in several seminal reviews of marriage and health research (Burman & Margolin, 1992; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001; Leonard, Cano, & Johansen, 2006)3 and manually searched the reference lists of publications that we reviewed. Searches were conducted by manuscript authors and undergraduate research assistants in our laboratory, and search results were collated, checked for duplicates, and sorted by the first author. Full-text articles were reviewed by the authors, who selected articles for inclusion based on the criteria described below. Figure 2 shows the flow diagram.

Figure 2.

Flowchart describing identification and screening of studies.

Study selection

Independent variable: Marital quality

We defined marital quality broadly as global self- or other-reported evaluation of the marriage and/or behaviors within the marriage, in terms of positive dimensions (happiness, support, satisfaction) and negative dimensions (conflict, tension, strain; Bradbury et al., 2000; Fincham & Bradbury, 1987). Most theoretical frameworks of marital quality assume that patterns of behavior exchange between spouses are important antecedents, correlates, and consequences of marital quality (Karney & Bradbury, 1995). Thus, we included behavioral coding of spousal interactions because such measures often reflect aspects of marital quality that are difficult to measure through self-report, are correlated with self-report measures of marital quality, and have yielded significant insights into understanding marital communication (Heyman, 2001).

Self-report measures varied from well-established and widely-used measures such as the Marital Adjustment Test (MAT; Locke & Wallace, 1959) and Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; Spanier, 1976), to validated but less widely-used measures such as the Stockholm Marital Stress Scale (Orth-Gomér et al., 2000), and single-use measures that had acceptable construct validity but were often idiosyncratic to particular studies. Behavioral measures included well-established behavioral coding systems such as the Marital Interaction Coding System (MICS; Heyman, Weiss, & Eddy, 1995), Specific Affect coding system (SPAFF; Gottman & Krokoff, 1989), and the Kategoriensystem für Partnerschaftliche Interaktion Interactional Coding System (KPI; Hahlweg, 1984).

Dependent variables: Health outcomes

Using the Biomarkers Definitions Working Group (2001) definitions, objective clinical endpoints included: Mortality, physician ratings of function or disease severity, diagnosis or incidence of a disease condition or disease-related event, hospitalizations or length of hospitalization, and objectively-assessed physical functioning. When incidence was self-reported by participants and verified clinically, it was considered an objective endpoint. When incidence was not was verified clinically, those outcomes were classified as subjective clinical endpoints, which included self-rated health (single-item measures of perceived health, Short-Form-36 Health Survey [SF-36; Ware, Kosinski, & Dewey, 2000], other physical health-related quality-of-life measures), symptoms (general or disease/condition-specific), pain severity, pain-related disability, adherence to medical recommendations, and functional impairment (e.g., activities of daily living [ADL], such as personal hygiene and self-feeding; or instrumental ADL ratings, such as shopping and housework). Two adherence measures were actually objective, including attendance at dialysis appointments (Kimmel et al., 2000) and electronic reports of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) downloaded from the CPAP device in sleep apnea patients (Baron, Smith, Czajkowski, Gunn, & Jones, 2009), which we categorized with subjective adherence measures in subanalyses of adherence outcomes to provide a sufficient number of studies. Surrogate endpoints were defined in Table 1, and the cardiovascular and metabolic markers in particular are considered surrogate endpoints by their respective fields (see references in Table 1, also Sacks et al., 2011).

Dependent variables: Biological mediators

Cardiovascular reactivity and HPA axis function studies had sufficient numbers of studies to include in a meta-analysis. Within HPA axis function, some studies obtained multiple samples during the day across multiple days to measure daily cortisol in naturalistic settings, while others obtained multiple samples before, during, and after a marital conflict discussion task in the laboratory.

Additional inclusion criteria

In addition to the criteria described above, inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) Publication in a peer-reviewed, English language journal; and 2) adequate statistics for computing an effect size r for the relationship between marital quality and health outcome(s). We excluded studies that: 1) only reported relationships between marital status and health, for reasons described in the Introduction; 2) only reported relationships between marital quality and sexual functioning (which have strong bidirectional associations with each other, Schwartz & Young, 2009) or mental health (including mental health-related quality-of-life and various indices of mental well-being and adjustment), which was covered in a previous meta-analytic reviews (Proulx, Helms, & Buehler, 2007); 3) examined marital quality as a dependent variable (e.g., the impact of disease diagnosis on marital quality) or reported results from a non-couples related intervention (e.g., medical treatment) on marital functioning, each of which would reflect the influence of changes in health on marital functioning rather than the reverse; 4) only reported relationships between marital quality and child or adolescent health, rather than adults; and 5) primarily focused on intimate partner violence as an independent variable, where violence and abuse directly contribute to health problems (Campbell, 2002). Participant populations ranged from healthy adults free of chronic illness to patients with chronic illness. We included both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs in the meta-analysis.

Data extraction

A rating sheet was prepared and revised several times during coding. Variables coded included: Study year, first author, country, participant composition, mean age, age range, percentage of women in the sample, marital quality measure, length of follow-up, covariates, and test statistics. All authors served as raters, and each study was coded by at least two raters.

For each study, we computed an effect size r for the relationship between marital quality and health outcome. We derived rs from: Unadjusted correlations between the two variables when reported; β-statistics (standardized regression coefficients) from multiple regression analyses if unadjusted correlations were not available, which were then transformed to rs using an imputation formula (r = β + .05λ, where λ equals 1 when β is nonnegative and 0 when β is negative, Peterson & Brown, 2005); t-statistics from independent-samples t-tests and multilevel modeling if df were available; χ2 statistics; and odds ratios using standard transformations (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009). Several studies reported hazard or risk ratios (HR or RR), which cannot be transformed to rs, and other studies reported p-values or p ranges only (e.g., < .05). For these studies, we converted the p to its one-tailed normal Z-value which corresponded to p = .0005, p = .005, p = .025, and p = .50 for p < .001, .01, .05, and ns, respectively, and computed . In cases where a paper did not provide sufficient statistics we contacted the author to obtain the necessary information.

Dependent samples in endpoint studies

In some cases, our literature search yielded several effect sizes from the same sample reported within the same study (e.g., an effect size for self-rated health and blood pressure). If the multiple dependent variables in a single study could be reasonably separated into the different endpoint categories they were analyzed separately in their respective categories. Multiple dependent variables within the same endpoint category were aggregated, but also analyzed separately in subanalyses (e.g., self-rated health and functional impairment, both subjective clinical endpoints). Our literature search yielded multiple papers from the same sample (rather than several effect sizes from a sample reported in the same paper). To avoid violating the assumption of sample independence (Borenstein et al., 2009), when multiple papers from the same sample had the potential to be in the same set of analyses (e.g., both studies from the Americans’ Changing Lives survey [Prigerson, Maciejewski, & Rosenheck, 1999; Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, & Needham, 2006] could be included in analyses of all longitudinal studies), we selected the study with the largest sample size for the analysis.

Multiple metrics in biological mediator studies

Studies examining cardiovascular reactivity to marital discussions (k = 14) typically reported results for heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), or some combination of the three. We extracted separate effect sizes for each metric, and reported aggregated effect sizes across outcomes (e.g., averaging the effect size for SBP and DBP within a study) and within each cardiovascular reactivity metric (HR k = 11, SBP k = 8, DBP k = 6). Most studies examined either absolute levels during marital discussions or changes from baseline to the discussion task.

Studies involving repeated sampling of cortisol during the day across multiple days reported various metrics, including area under the curve with respect to ground (which reflects the total concentration of cortisol during the day; Ditzen, Hoppmann, & Klumb, 2008; Vedhara, Tuinstra, Miles, Sanderman, & Ranchor, 2006), cortisol slope (change in cortisol from morning to evening; Barnett, Steptoe, & Gareis, 2005; Floyd & Riforgiate, 2008; Saxbe, Repetti, & Nishina, 2008; Vedhara et al., 2006), the change from waking to 30-45 min post-waking known as the cortisol awakening response (Barnett, Steptoe, & Gareis, 2005), and individual cortisol data points (e.g., waking cortisol levels; Floyd & Riforgiate, 2008; Saxbe et al., 2008). We had a sufficient number of studies (k > 2) to conduct a meta-analysis for cortisol slopes, but not other metrics. Studies involving cortisol response to marital discussions (k = 4) typically measured cortisol at baseline, and then during and in some cases after the discussions.

Effect size extraction

In analyses of an entire endpoint category, effect sizes were averaged to yield one effect size per study. Effect sizes for multiple related endpoints, most notably SBP and DBP, were averaged to yield a single effect size per study. Several studies reported effect sizes from multiple independent variables and a single endpoint (e.g., three different measures of marital quality related to self-rated health), and these effect sizes were similarly averaged to yield a single effect size per study. We considered using a correction technique to account for the dependency between effect sizes in these studies (Cheung & Chan, 2004, 2008) which is quite advantageous4, but ultimately chose a more conservative approach (increasing possible Type II error by overestimating sampling error) by using the actual sample sizes rather than any correction. Finally, several studies reported different effect sizes from the same sample at different points in time in different papers. If both papers could be included in the same analysis, we used the earlier report to increase the study sample size (i.e., later followup intervals had more attrition). For example, in a study of marital quality in congestive heart failure patients reported mortality, we used the 4-year (Coyne et al., 2001) rather than the 8-year follow-up (Rohrbaugh, Shoham, & Coyne, 2006).

Data analysis

All analyses, with the exception of multilevel models examining the effects of covariates on effect sizes, were conducted using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis program (Version 2). We performed random effects modeling, which is appropriate since we aggregated data from independent studies that are not functionally identical, with the goal of generalizing to a larger range of studies (Borenstein et al., 2009). Effect sizes were weighted by the inverse of their variances, which allows larger studies to provide larger contributions to the aggregate effect size estimate compared to smaller studies. Throughout the paper, we report 95% confidence intervals (CI). We report two estimates of heterogeneity: Q, a statistical test of whether between-study variance is greater than within-study variance, and I2, the ratio of true heterogeneity to total variation in the observed effects. Larger I2 values (range 0 – 100) indicate that the observed heterogeneity is not spurious and may be systematically explained by moderating variables.

We conducted our primary analyses including cross-sectional and longitudinal designs together, followed by separate analyses for each endpoint and design5. If a paper reported both longitudinal and cross-sectional effect sizes, we included the longitudinal effect size.

Moderators

To examine the contribution of moderating variables, we combined results across cross-sectional or longitudinal studies to increase available study sample size. The contribution of moderating variables to observed heterogeneity was analyzed using random effects meta-regression (method of moments, Borenstein et al., 2009).

Theory-based moderators: Gender and gender inequality

We examined gender composition of the sample (% women) as a moderator, and also tested whether there were gender differences in the relationship between marital quality and health. For gender composition, we determined the proportion of women in each study, shown in Tables 2 - 4. If the relationship between marital quality and health is stronger for women compared to men, one could potentially expect that studies with a greater proportion of women may have larger effect sizes.

Table 2.

Surrogate Endpoint Studies

| Study | Sample characteristics | Marital quality | Dependent measure and effect sizes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||

| N; Description | M age | % women |

Measure | Validity rating |

Outcome | rmin | SE r | Covariates | rmax | Gender d |

|

| Cross-sectional studies | |||||||||||

| Cardiovascular risk factors – blood pressure | |||||||||||

| Baker et al. (1999) | 161; P/C Hypertension dx Canada |

34.6 | 46.3 | DAS Cohesion | 2.75 | BPa | .08 | .08 | 5 | - | - |

| Barnett et al. (2005) | 105; C, H Subsample of Whitehall United Kingdom |

55 | 36 | SS: Marital role quality – concerns |

3 | BPb | .08 | .08 | 6 | - | - |

| Carels et al., (2000) | 50; C, H Half with DAS > 100 |

33.9 | 100 | DAS (nr) | 4 | BPc | .31 | .13 | 4 | - | - |

| Grewen et al. (2005) | 325; C Normal BP or mild hypertension; 43% African- American, 53% white |

38.5* | 51.7* | DAS (nr) | 4 | BPb | .18 | .05 | 4 | - | 0.09 |

| Holt-Lunstad, Birmingham, & Jones (2008) | 204; C, H | 31.2 | 49 | MAT (nr); DAS Satisfaction |

4 | BPa | .13 | .07 | 2 | - | 0.09 |

| Reeder (1956) | 300; C, H | nr | 0 | Burgess-Cottrell Marital Adjustment Scale short-form |

3.5 | BPd | −.12 | .06 | 0 | - | - |

| Tobe et al. (2005) | 248; C, H Canada |

54.6 | 50.8 | DAS Cohesion | 2.75 | BPa | .12 | .06 | 12 | - | - |

| Trevino et al. (1990) | 109; P/C Hypertension dx |

50.5 | 57.7 | DAS (106) |

4 | BPe | −.11 | .10 | 4 | - | - |

| Trief et al. (2006) | 134; P/C Diabetes patients; Subsample of Phase 1 telemedicine trial |

70.1 | 43 | DAS Cohesion & Satisfaction; Perceived Marital Stress Scale |

4 | BPd | .12 | .09 | 0 | - | - |

| Cardiovascular risk factors – structural markers | |||||||||||

| Baker et al. (1998) | 176; P/C Hypertension dx No other CVD Canada |

46 | 35.6 | DAS (nr) Areas of Change Q |

4 | Relative wall thickness; LVMI |

.00 | .08 | 16 | - | - |

| Gallo, Troxel, Kuller, Sutton-Tyrrell et al. (2003) | 200; C, H Subsample of Pittsburgh Healthy Women’s Study |

47.7 | 100 | SS: Marital satisfaction |

3 | Carotid IMT; Carotid plaque |

.16 | .07 | 3 | - | - |

| Smith, Uchino, Berg, & Florsheim (2012) | 308; C, H Older couples in Utah Health and Aging Study, with no CVD |

63.5 | 50 | Discordant vs. non discordant couplesf |

4 | Coronary artery calcification |

.16 | .06 | 12 | - | 0.03 |

| Other surrogate endpoints | |||||||||||

| Greene & Griffin (1998) | 17; P/C Parkinson’s disease |

72.2 | 12 | MAT (104.5) | 4 | Observed signs of orofacial hypokinesiag |

.16 | .26 | 0 | - | - |

| Sobal et al. (1995) | 1,980; R, NR National Survey of Personal Health Practices and Consequences |

nr | 60 | SS: Marital happiness and problems |

2.5 | BMI | −.02 | .02 | 0 | .04 | 0.11 |

| Trief et al. (2001) | 78; P/C Diabetes dx (56% Type 1) |

46 | 58 | DAS (nr) | 4 | HbA1c | .00 | .12 | 0 | - | - |

| Trief et al. (2006) | 134; P/C Subsample of Phase 1 telemedicine diabetes intervention trial |

70.1 | 43 | DAS Cohesion & Satisfaction; Perceived Marital Stress Scale |

4 | HbA1c | .15 | .09 | 0 | - | - |

| Whisman, Uebelacker, & Settles (2010) | 1,342; NR English Longitudinal Study of Ageing United Kingdom |

64 | 50 | SS: Self-reported supportive and negative interactions with spouse |

2.5 | Metabolic syndromeh |

.08 | .03 | 7 | .09i | 0.13 |

|

Longitudinal studies (length of follow-up intervals in parentheses under Outcome) | |||||||||||

| Baker, Paquette, Szalai, Driver, Perger, Helmers, O’Kelly et al. (2000) | 72; P/C Early hypertension dx Canada |

47.3 | 36 | DAS (108.4) | 4 | Δ LVMI (3 y) | .20 | .12 | 3 | - | - |

| Black (1988) | 26; P/C Obese patients undergoing weight loss program |

45.4 | 69 | Baseline MAT (109.6*) |

4 | Lbs lost (15 mo) | −.42 | .17 | 0 | - | - |

| Gallo, Troxel, Kuller, Sutton-Tyrrell et al. (2003) j | 200; C, H Subsample of Pittsburgh Healthy Women’s Study |

47.7 | 100 | SS: Marital satisfaction |

3 | Δ Carotid IMT and carotid plaque (3 y) |

.12 | .07 | 3 | - | - |

| Hafner et al. (1990) | 71; P/C Obese patients undergoing gastric restriction surgery |

nr | 100 | Marital Attitudes Evaluation Scale: Control and Include behavior subscales |

2.75 | Δ BMI (15 mo) |

.38 | .10 | 0 | - | - |

| Janicki et al. (2005) | 250; C, H Subsample of Pittsburgh Healthy Heart Project |

60.7 | 47.6 | DAS (111.9) | 4 | Δ Carotid IMT (3 y) |

−.07 | .06 | 2 | - | - |

| Phillips et al. (2006) | 66; C, H United Kingdom |

74.6 | 56.5 | MAT (nr) | 4 | Δ Influenza virus vaccine antibody titers (A/Panama strain; 1 mo) |

.20 | .12 | 1 | - | - |

| Tobe et al. (2007) | 229; C, H Canada |

53.7 | 50.8 | DAS Cohesion | 2.75 | Δ 24 h ambulatory BP (1 y) |

.10 | .07 | 13 | - | −0.005 |

| Trief et al. (2002) | 61; P/C Diabetes (56% Type 1) |

47 | 62 | DAS (nr) | 4 | ΔHbA1c (2 y) | .006 | .13 | 0 | - | - |

| Trief et al. (2006) | 134; P/C Subsample of Phase 1 telemedicine diabetes intervention trial |

70.1 | 43 | DAS Cohesion & Satisfaction; Perceived Marital Stress Scale |

4 | HbA1c (1 y) | −.03 | .09 | 8 | - | - |

| Troxel et al. (2005) | 413; C, H Subsample of Pittsburgh Healthy Women’s Study |

47.1 | 100 | SS: Marital satisfaction |

3 | Metabolic syndromeh (3 y) |

.29 | .05 | 3 | - | - |

| Wang et al. (2007) k | 69; P/C Myocardial infarction or unstable angina dx Sweden |

56 | 100 | SS: Marital stress | 3.25 | Δ coronary artery luminal diameter (3 y) |

.32 | .11 | 0 | - | - |

| Whisman & Uebelacker (2012) l | 432; NR English Longitudinal Study of Ageing United Kingdom |

62.4 | 50 | SS: Self-reported supportive and negative interactions with spouse rated by participant and partner |

2.5 | Metabolic syndromeh (4 y) |

.20 | .05 | 7 | - | 0.11 |

Note. Studies are organized by study design (cross-sectional or longitudinal), outcome, and are listed in alphabetical order by author. All study samples collected in the United States unless otherwise noted in the study description. Sample size refers to total number of individuals (as opposed to couples). Signs for all effect sizes were oriented to indicate that higher scores on marital quality are related to better health. For instance, if a reported effect size originally indicated that greater marital quality was related to lower ambulatory systolic blood pressure (r = −.16), and lower ambulatory systolic blood pressure is an indicator of better health, we changed the sign to r = + .16. Covariates only refer to number of variables, not terms in a regression (i.e., interactions). Gender differences were computed as women – men; thus, negative numbers indicate larger effects for women compared to men. Dashes indicate data are not available. For sample descriptions: C = community, dx = diagnosis, H = healthy, NR = nationally representative, P/C = patient/clinic sample + primary diagnosis of interest (if specified), R = random sample. For marital quality measures: SS = Study-specific measure; sample means for the DAS and MAT are reported in parentheses. Unless otherwise noted, Δ = change from baseline measures, nr = not reported, = inferred from other descriptive statistics in paper. CVD = cardiovascular disease; LVMI = left ventricular mass index; IMT = artery intima media thickness; Q = Questionnaire.

24 hour ambulatory BP.

ambulatory SBP and DBP during waking hours.

ambulatory SBP and DBP recorded at home for 15 hours.

Resting SBP and DBP or categories of SBP and DBP based on cutoffs.

Resting DBP – three most recent readings from medical record.

Grouping based on cluster analysis of behavioral and self-reported marital satisfaction data.

Rate of speech, rate and duration of eye blink during couple discussion.

Metabolic syndrome was indicated by presence of 3 or more of the following risk factors (based on established cutoffs): elevated fasting glucose or use of glucose-lowering medication, elevated triglyceride level, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level, high waist circumference, high systolic and/or diastolic blood pressure or use of antihypertensive medication.

An rmax model was only available for women, and not men in the sample. In the multilevel modeling analyses only the results for women are included.

Same sample as Troxel et al. (2005). Because of the smaller sample size relative to the Troxel paper, this paper was excluded from the meta-analyses of all longitudinal surrogate endpoint studies, and moderator and sensitivity analyses. The paper was only included in the meta-analyses for cross-sectional CVD surrogate endpoints, and longitudinal CV structural markers. Also same sample as Gallo, Troxel, Matthews, & Kuller (2003), which examined longitudinal associations with hematological markers of cardiovascular risk, including cholesterol, triglycerides, and fasting glucose levels. However, because no other studies examined levels of these markers, we included the Gallo et al. (2003) on atherosclerotic burden because other studies assessing structural markers of cardiovascular disease were available.

Same sample as Orth-Gomér et al. (2000), a longitudinal objective endpoint study. Subsample of Stockholm Female Coronary Risk study. Excluded from moderator analyses.

Same sample as Whisman, Uebelacker, & Settles (2010). Couples < 80 years old in intact marriages who completed the four-year follow-up. Because of the smaller sample size relative to the 2010 paper, this paper was excluded from analyses that combined cross-sectional and longitudinal studies.

Table 4.

Objective Clinical Endpoint Studies

| Study | Sample characteristics | Marital quality | Dependent measures and effect sizes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||

| N; Description | M age | % women |

Measure | Validity rating |

Outcome |

r

min |

SE r | Covariates | rmax | Gender d | |

| Cross-sectional | |||||||||||

| Fink et al. (1968) | 36; P/C Severely disabled women |

nr | 100 | SS composite a |

3.5 | Physician rating of physical mobility |

.05 | .17 | 0 | - | - |

| Kimmel et al. (2000) | 174; P/C End-stage renal disease patients (90.8% African-American) |

54* | 23 | DAS Satisfaction, Negativity |

4 | Rating of disease severity |

.06 | .08 | 0 | −0.06 | |

| Marcenes & Sheiham (1992) | 164; C Fathers of schoolchildren Brazil |

41.2 | 0 | SS: Marital quality |

2.75 | Count of decayed, missing, and filled tooth surfaces |

.41 | .07 | 0 | - | - |

| Marcenes & Sheiham (1996) b | 164; C Mothers of schoolchildren Brazil |

38.4 | 100 | SS: Marital quality |

2.75 | Dental caries and periodontal disease status based on clinical examination |

.25 | .05 | 0 | - | −0.09 |

| Longitudinal studies (length of follow-up intervals in parentheses under Outcome) | |||||||||||

| Ashmore, Emery, Hauck, & MacIntyre (2005) | 31; P/C Patients with diagnosis of COPD in pulmonary rehabilitation |

67.8 | 35.5 | DAS (111.7) | 4 | Δ 12 min walk test times (5 wk) |

.00 | .19 | 0 | - | - |

| Coyne, Rohrbaugh, Shoham et al. (2001) | 189; P/C Congestive heart failure patients |

53 | 26 | SS compositec | 2 | Mortality (4 years) |

.28 | .07 | 0 | .28 | 0.42 |

| Eaker, Sullivan, Kelley-Hayes, D’Agostino Sr., & Benjamin (2007) | 2,994; C Subsample of Framingham Offspring Study |

49 | 50 | SS: Spouse shows love. |

2.75 | Incidence of CHD (MI, coronary insufficiency and mortality), mortality (10 y) |

.00 | .02 | 7 | - | −0.0006 |

| Haynes, Feinleib, & Kannel (1980) | 1,764; R, C Subsample of Framingham Heart Study |

57.5 | 57 | SS: Conflict, satisfaction |

2.5 | CHD: Myocardial infarction; coronary insufficiency syndrome; angina pectoris; coronary heart disease, death. (8 y) |

.00 | .02 | 0 | - | - |

| Helgeson (1991) | 73; P/C Post myocardial infarction dx |

53.5* | 22 | SS: Disclosure | 2.25 | Rehospitalization for cardiac event (1 y) |

.60 | .08 | 5 | - | - |

| Hibbard & Pope (1993) | 2,157; C 5% sample of regional health maintenance organization members in Pacific Northwest |

41.5* | 54 | SS: Satisfaction |

3 | Diagnosis of stroke, ischemic HD, cancer malignancy, and mortality (15 y) |

.00 | .02 | 5 | - | −0.001 |

| Kiecolt-Glaser et al. (2005) | 84; C, H Married couples |

37 | 50 | Hostile behaviors (RMICS) |

3 | 90% wound healing after blister wound (12 days) |

.23 | .11 | 2 | - | - |

| Kimmel et al. (2000) d | 174; P/C End-stage renal disease patients (90.8% African-American) |

54* | 23 | DAS Satisfaction, Negativity |

4 | Mortality (median 36.8 mo) |

.20 | .07 | 5 | - | 0.29 |

| King & Reis (2012) | 181; P/C Coronary artery bypass surgery recipients |

60.6* | 76.9* | SS: Satisfaction item from MAT 1 y post- surgery |

3 | Mortality (15 y) | .30 | .07 | 0 | .31 | 0.32 |

| Kulik & Mahler (2006) | 296; P/C CABG patients |

64.2 | 24 | DAS (nr) | 4 | Length of stay after first-time CABG operation (5 – 7 days) |

.09 | .06 | 0 | - | 0.21 |

| Medalie et al. (1992) | 8,458; R, C Male civil service employees Israel |

51.8 | 0 | SS: Support (wife showing love) |

1.25 | Duodenal ulcer incidence (5 y) |

.13 | .01 | 6 | .14 | - |

| Orth-Gomér et al. (2000) | 187; P/C Patients previously hospitalized with acute MI; Stockholm Female Coronary Risk study Sweden |

55.8 | 100 | SS: Marital stress |

3.25 | Recurrent coronary events, including mortality (median 4.8 y) |

.19 | .07 | 1 | .19 | - |

| Vitaliano et al. (1993) | 77; P/C Alzheimer’s patients |

71.2 | 34 | Expressed emotion during caregiver interview |

2 | Mini-mental status score (15-18 mo) |

.00 | .12 | 0 | - | - |

| Yang & Schuler (2009) | 100; P/C Newly diagnosed, surgically treated breast cancer patients |

48.6 | 100 | DAS Satisfaction |

4 | Karnofsky Performance Status scale (5 y) |

.08 | .10 | 5 | - | - |

Note. Studies are organized by study design (cross-sectional or longitudinal) and are listed in alphabetical order by author. Sample size refers to total number of individuals (as opposed to couples). All study samples collected in the United States unless otherwise noted in the study description. Signs for all effect sizes were oriented to indicate that higher scores on marital quality are related to better health. Covariates only refer to number of variables, not terms in a regression (i.e., interactions). Gender differences were computed as women – men; thus, negative numbers indicate larger effects for women compared to men. For sample descriptions: C = community, dx = diagnosis, H = healthy, NR = nationally representative, P/C = patient/clinic sample + primary diagnosis of interest (if specified), R = random sampling. For marital quality measures: SS = Study-specific measure; sample means for the DAS and MAT are reported in parentheses. Unless otherwise noted, Δ = change from baseline measures, nr = not reported, = inferred from other descriptive statistics in paper. CABG = Coronary artery bypass graft; CHD = coronary heart disease; COPD = Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MI = myocardial infarction; RMICS = Rapid Marital Interaction Coding System.

Companionship, social status, power, understanding, affection, marital esteem, and sex in marriage.

Same sample as Marcenes and Sheiham (1992), only including data from mothers, but the paper provided separate estimates for mothers and fathers allowing for gender comparisons.

Self-reported marital satisfaction, marital routines, positive illness discussions, and observed positive behavior.

Same sample as Kimmel (2000), in cross-sectional subjective endpoints. Included in meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies, and moderator analyses.

To test for gender differences in the relationship between marital quality and health, when possible we extracted separate effect size estimates for men and women and/or statistical tests of the interaction between gender and marital quality on health outcomes. Relatively few studies provided separate effect size estimates for men and women (k = 25), and even fewer provided estimates of the interaction between gender and marital quality (k = 10). When separate effect sizes were available, we computed effect size rs for men and women within each study. We then compared correlation coefficients between men and women within each study by using the procedure developed by Fisher for comparing whether two correlation coefficients are equal, which yields a normally distributed z-statistic (J. Cohen & Cohen, 1983), which was converted to a Cohen’s d using the transform . For studies that reported estimates of the interaction between gender and marital quality, we computed an effect size d based on the test statistics (ts and Fs). We then performed a random effects meta-analysis on the available d-statistics describing differences in the relationship between marital quality and health for men compared to women (after accounting for duplicate samples, k = 34).

For gender inequality, we used the Gender Inequality Index (GII) developed by the United Nations Human Development Report Office (2011), which reflects the degree of disadvantage women face in health (maternal mortality ratio, adolescent fertility rate), empowerment (share of national parliamentary seats held by women, secondary and higher education attainment levels), and labor (workforce participation) in different countries. While this index does not reflect attitudes towards gender role equality (e.g., whether the populace has favorable attitudes towards gender equality), the GII does provide indicators of the real-world manifestations of such attitudes. The GII ranges from 0 (women and men fare equally) to 1 (women fare as poorly as possible in all dimensions). We selected scores from the 1995 report, which was the earliest available (ratings were highly stable across time, with an intraclass correlation of .98 for the 11 countries in this sample). Scores ranged from .08 (Sweden) to .52 (Brazil), with a mean of .21. The most represented country was the United States, GII = .28. Using this index allowed us to examine whether the degree of gender inequality in health, social, and labor between countries moderated the relationship between marital functioning and health, which may partially address the subordinate-reactivity hypothesis discussed in the introduction.

Methodology-related moderators

In addition to type of outcome (surrogate, subjective and objective clinical), we considered several methodology-related moderators: Study design (i.e., cross-sectional versus longitudinal), marital quality construct validity, and publication year.

Study design

Observational research on marital quality and health outcomes involves cross-sectional and prospective longitudinal designs. Cross-sectional studies cannot address the directionality of the relationship between physical health and marital satisfaction; only prospective studies can determine whether poor-quality marriages compromise physical health or whether poor physical health is a causal factor for subsequent marital dissatisfaction. In light of clear methodological differences between cross-sectional and prospective studies, we examined study design as a dichotomous moderator variable.

Marital quality construct validity

Marital quality is a multidimensional construct that can be measured with multiple instruments within multiple modalities, including self- or spouse-report and objective coding. The proliferation of marital quality measures in the literature makes generalizing findings across studies difficult, particularly studies with idiosyncratic measures. To examine construct validity as a potential moderator of the observed relationships between marital functioning and health, study authors independently rated the degree of construct validity of each marital quality measure, where: 0 = not representative, should not be considered for further inclusion in the meta-analysis; 1 = minimally representative of the evaluative and/or behavioral component of marital quality, with items or behaviors not used in traditional marital quality measures, representing only one dimension (positive or negative); 2 = somewhat representative of the evaluative and/or behavioral component of marital quality, with items or behaviors not used in traditional marital quality measures, both positive and negative dimensions represented; 3 = very representative of evaluative/behavioral components, most items shared with traditional marital quality measures, representing only one dimension; 4 = extremely representative, many shared items with traditional marital quality measures, both positive and negative dimensions represented. Measures of relationship satisfaction (e.g., MAT, DAS) and multidimensional measures (PREPARE, ENRICH inventories, Marital Satisfaction Inventory) recommended by Snyder, Heyman, and Haynes (2005) in their review of evidence-based assessments were rated with a 4. We averaged those ratings across the four raters to provide a single rating of marital quality measure construct validity for each study. The two-way random effects intraclass correlation for absolute agreement using the average of the raters was .86, 95% CI [.78, .92], indicating high reliability for the average construct validity ratings.

Publication year

Both marriage and public health have gone through considerable changes over the last half-century, which may influence the relationship between marital quality and health. To address these effects, we examined publication year as a moderator variable.

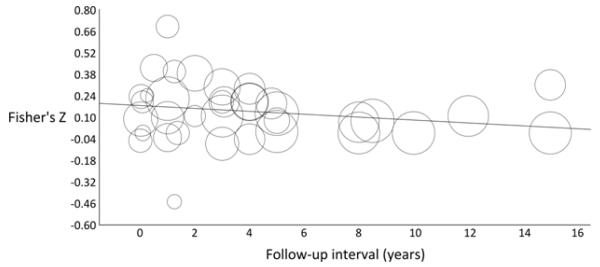

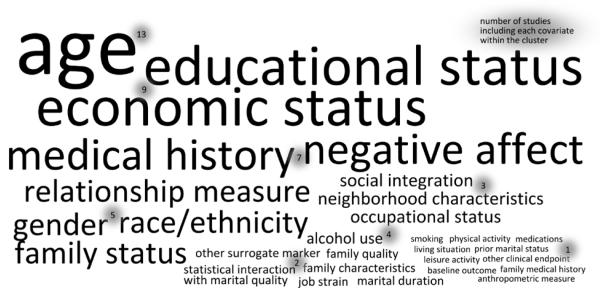

Covariates and confounders