Summary

SoxR from E. coli and related enterobacteria is activated by a broad range of redox-active compounds through oxidation or nitrosylation of its [2Fe-2S] cluster. Activated SoxR then induces SoxS, which subsequently activates more than 100 genes in response. In contrast, non-enteric SoxRs directly activate their target genes in response to redox-active compounds that include endogenously produced metabolites. We compared the responsiveness of SoxRs from Streptomyces coelicolor (ScSoxR), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PaSoxR) and E. coli (EcSoxR), all expressed in S. coelicolor, toward natural or synthetic redox-active compounds. EcSoxR responded to all compounds examined, whereas ScSoxR was insensitive to oxidants such as paraquat (Eh −440 mV) and menadione sodium bisulfite (Eh −45 mV) and to NO generators. PaSoxR was insensitive only to some NO generators. Whole cell EPR analysis of SoxRs expressed in E. coli revealed that the [2Fe-2S]1+ of ScSoxR was not oxidizable by paraquat, differing from EcSoxR and PaSoxR. The mid-point redox potential of purified ScSoxR was determined to be −185 ± 10 mV, higher by ~100 mV than those of EcSoxR and PaSoxR, supporting its limited response to paraquat. The overall sensitivity profile indicates that both redox potential and kinetic reactivity determine the differential responses of SoxRs toward various oxidants.

Keywords: SoxR, Fe-S, redox-active compounds, EPR, Redox potential

Introduction

Bacteria are exposed to a variety of redox-active molecules that include reactive oxygen and nitrogen species as well as organic compounds. Some of these agents are generated endogenously, whereas bacteria encounter others in their external environment. Plants and bacteria produce a variety of redox-active metabolites, some of which we identify as quorum signals, virulence factors, antibiotics, toxins, etc, depending on the life phenomena that we are interested in (Okegbe et al., 2012). When internalized in the bacterial cytoplasm, some of these redox-active compounds can generate superoxide anion radicals by abstracting electrons from redox enzymes and then transferring them to O2. This cycle is catalytic, thus befitting the name ‘redox-cycling’ agent.

When E. coli and Salmonella typhimurium are exposed to such compounds, their transcriptional regulator SoxR is activated by oxidation of its [2Fe-2S] cluster (Gaudu and Weiss, 1996, Ding et al., 1996, Ding and Demple, 2000, Pomposiello and Demple, 2000, Crack et al., 2012). Activation can also occur by cluster nitrosylation during exposure to nitric oxide sources (Ding & Demple, 2000). Both cluster modifications trigger a structural change that enables SoxR to form an open complex at the promoter of its target gene, soxS, by optimizing the spacing between −35 and −10 elements (Hidalgo et al., 1997, Watanabe et al., 2008). The overproduced SoxS then induces the transcription of more than 100 genes, including superoxide dismutase, DNA repair nucleases, oxidation-resistant enzymes, efflux pumps, and catabolic enzymes (Blanchard et al., 2007, Pomposiello et al., 2001). When stressors are absent, the oxidized [2Fe-2S] cluster is reduced, partly by an enzyme system that consists of proteins from rsxABCDGE and rseC genes, shifting SoxR to its inactive state (Koo et al., 2003).

Interestingly, the soxS gene is confined to enterobacteria, whereas soxR is found in a wider range of bacteria such as proteobacteria (α, β, γ, δ), and actinobacteria (Dietrich et al., 2008). Furthermore, studies in non-enterics suggested that in these organisms SoxR has a different physiological impact than in enterics. In pseudomonads (Palma et al., 2005, Park et al., 2006), Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Eiamphungporn et al., 2006), Xanthomonas campestris (Mahavihakanont et al., 2012), and S. coelicolor (Dela Cruz et al., 2010, Shin et al., 2011) SoxR directly targets a limited number of genes, none of which encodes superoxide dismutase. Furthermore, in addition to responding to several synthetic redox-cycling drugs, the SoxR regulon genes in several of these organisms are induced by endogenously produced redox-active metabolites, including pyocyanin in Pseudomonas species (Dietrich et al., 2008) and actinorhodin in S. coelicolor (Dietrich et al., 2008, Dela Cruz et al., 2010, Shin et al., 2011). These departures from the E. coli paradigm led to a reconsideration of the generalized function of SoxR and of the mechanism of its activation. Contrary to a long-held idea of SoxR activation by superoxide, a recent work put forward the idea that SoxR is primarily activated by redox-active metabolites, not by superoxide, even in E. coli (Gu and Imlay, 2011). This was based on such observations that SoxR can be activated in vivo under anoxic conditions in the absence of any superoxide and that the [2Fe-2S] of purified SoxR can be directly oxidized by redox-cycling agents in vitro (Gu and Imlay, 2011). Superoxide may be able to activate SoxR (Liochev and Fridovich, 2011, Fujikawa et al., 2012) but probably with too low an efficiency to act as a physiological signal (Gu and Imlay, 2011). The anoxic activation of SoxR by changes in the intracellular NADPH/NADP+ ratio (and possibly NADH/NAD+) supports this idea as well (Krapp et al., 2011). Therefore, a generalized mechanism of SoxR activation seems to exist across bacterial phyla (Dietrich and Kiley, 2011).

In P. aeruginosa, SoxR (PaSoxR) is activated by endogenous pyocyanin, a signaling molecule with pleiotropic functions, and it induces genes for two putative transporters and one monooxygenase that can modify substrates through hydroxylation (Dietrich et al., 2006, Dietrich et al., 2008). In S. coelicolor, SoxR (ScSoxR) is activated by endogenous actinorhodin, a polyketide antibiotic, and induces genes for two putative NADPH-dependent reductases (SCO2478, SCO4266), an ABC transporter (SCO7008), a monooxygenase (SCO1909), and a hypothetical protein (SCO1178) (Dela Cruz et al., 2010, Shin et al., 2011). All known target genes of SoxR, whether from E. coli, P. aeruginosa, or S. coelicolor, share similar binding sequence for SoxR, consistent with the conservation of DNA-binding residues in SoxR.

Even though the DNA-binding property of SoxR is conserved, the oxidation or activation behavior seems quite different among different SoxRs, in terms of responsiveness (selectivity) toward a range of chemicals. A recent work proposed that PaSoxR and ScSoxR respond to a narrower range of chemicals than does EcSoxR (Sheplock et al., 2013). These non-enteric SoxRs were reported to be less sensitive to low-potential viologens such as paraquat (<−350 mV), leading to the proposal that PaSoxR and ScSoxR share structural properties that delimit which chemical signals are effective (Sheplock et al., 2013). Mutagenesis identified residues that were essential for the ability of EcSoxR to respond to paraquat (Chander et al., 2003). Some of these residues differ in PaSoxR and ScSoxR, and the “non-enteric type” residues were mutagenized to the “enteric” type in an effort to pinpoint the mechanistic/structural determinants of selectivity. This analysis implicated three “non-enteric” residues in restricting the sensitivity in PaSoxR toward paraquat (Chander et al., 2003).

However, apparent contradictions in the literature suggest that there remains important uncertainty regarding the behavior of SoxR. In contrast to the report of Sheplock et al. (2013), some studies indicate that PaSoxR is efficiently activated by paraquat (Kobayashi and Tagawa, 2004, Palma et al., 2005) and that SoxR from P. putida can restore paraquat-inducible soxS expression in E. coli ΔsoxR mutant (Park et al., 2006). Therefore, careful investigation is warranted to resolve whether SoxR from pseudomonads responds to paraquat and, if it does, why different labs obtain different results. Another puzzling question regards the redox potential of SoxR and its contribution in selecting effective chemical signals. PaSoxR is reported to have a redox potential similar to that of EcSoxR (Ding et al., 1996, Gaudu and Weiss, 1996, Kobayashi and Tagawa, 2004, Gorodetsky et al., 2008), yet PaSoxR was reported to be insensitive to paraquat (Sheplock et al., 2013). Whether SoxR contributes to resistance of the cell toward the inducing chemicals also remains enigmatic, since the reported observations, based on disk (inhibition zone) assay, suggested that PaSoxR and ScSoxR do not contribute to resistance, in contrast to EcSoxR and the SoxR proteins from A. tumefaciens and X. campestris (Sheplock et al., 2013).

In this study, we examined the activation behavior and function of SoxR in S. coelicolor. We also compared the sensitivity profiles of three representative SoxRs toward a range of redox-active compounds by expressing all proteins in S. coelicolor, thereby circumventing problems that might arise from the differential permeability of compounds into their native organisms. Our results demonstrate that of the three SoxRs, ScSoxR is the most limited in the range of chemicals to which it responds and has the highest reduction potential. It does serve to protect cells against the growth-inhibiting effect of inducing chemicals. Both kinetic and equilibrium (redox potential) factors determine the range of effective chemicals.

RESULTS

Induction of ScSoxR by both natural and xenobiotic redox active compounds in S. coelicolor

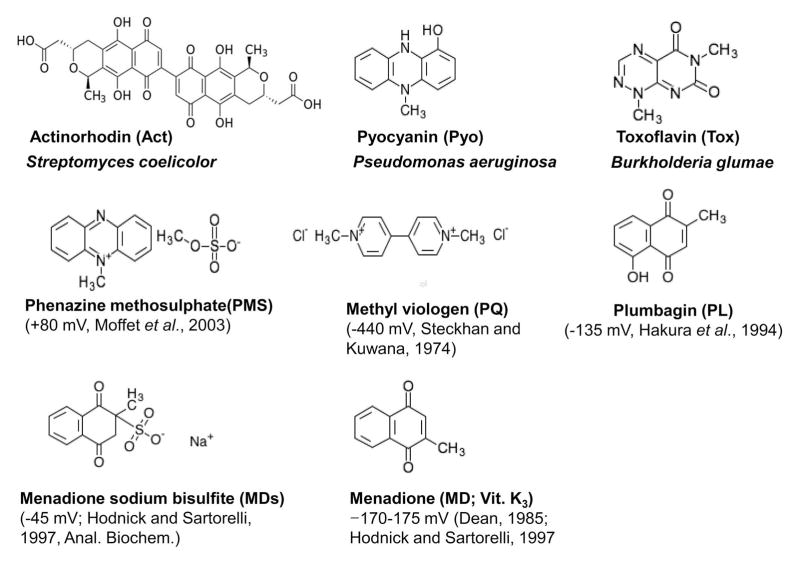

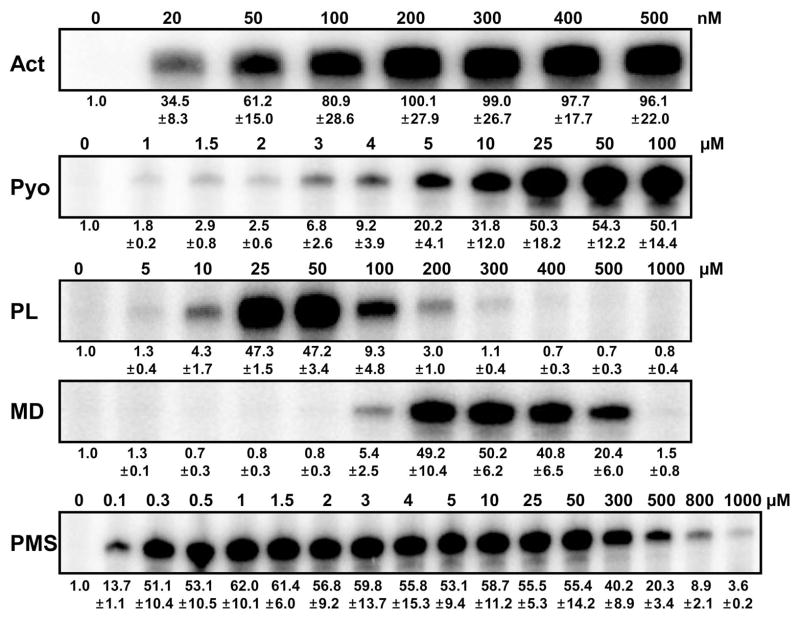

As a first step toward understanding the role and activation behavior of SoxR in S. coelicolor, we examined the effect of various redox-active compounds (RACs): three natural metabolites (actinorhodin, pyocyanin, toxoflavin) and five xenobiotic redox-cycling agents (phenazine methosulfate, paraquat, plumbagin, menadione, and menadione sodium bisulfite) (Fig. 1). The effective concentration ranges for ScSoxR activation were determined (Fig. 2). Exponentially growing cells were treated with RACs of varying concentrations for 30 min before RNA was isolated. S1 mapping was performed to quantify transcripts from a SoxR target gene (SCO2478), encoding a putative NADPH-dependent flavin reductase. The results demonstrated that as little as 20 nM γ-actinorhodin induced SoxR target gene expression, with maximal induction occurring between 200 nM and 500 nM (Fig. 2). Pyocyanin, a toxic blue phenazine pigment produced from P. aeruginosa, activated ScSoxR in low-micromolar doses and did so maximally at 25 to 100 μM. Plumbagin (5-hydroxy-2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone), a yellow pigment originally isolated from plants of genus Plumbago, activated SoxR in a narrow range of concentrations, with maximal induction at 25 to 50 μM. Menadione (2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone), a chemically synthesized naphthoquinone derivative, also activated SoxR in a narrow range of concentrations, with maximal induction at 200–300 μM. The water-soluble salt form of menadione (menadione sodium bisulfite; MDs) was not able to activate SoxR at any concentration examined, ranging from 5 μM to 1 mM (data not shown). This was not due to a cell-permeability barrier, as demonstrated below (Fig. 5). Phenazine methosulfate (PMS), a chemical phenazine derivative, activated SoxR in a broad concentration range from 0.1 μM to 1 mM, maximally at 0.3 to 50 μM. We examined the effect of methyl viologen (paraquat; PQ) in the concentration range of 5 μM to 1 mM, and found that it did not activate SoxR (data not shown). Again, this insensitivity was not due to permeability barrier as shown below (Fig. 5). Longer treatment of RACs inhibited growth by more than two-fold within 2 h at higher concentrations (> 300 nM actinorhodin, > 50 μM plumbagin, 300 μM menadione, >100 μM PMS; data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of redox-active compounds (RACs) examined in this study. Three natural metabolites from S. coelicolor (actinorhodin), P. aeruginosa (pyocyanin), and Burkolderia glumae (toxoflavin), and five xenobiotic redox-cycling agents were examined. The reported reduction potentials of the xenobiotics are indicated in parentheses. The reduction potential for paraquat (PQ, methyl viologen) is indicated for the pair PQ2+/PQ1+, since reduction of PQ1+ to PQo has a much lower potential and thus is irrelevant (Steckhan and Kuwana, 1974).

Fig. 2. The effective concentration range of RACs to activate SoxR in S. coelicolor.

Varying concentrations of RACs [0 – 0.5 μM of actinorhodin (Act), 0 – 0.1 mM of pyocyanin (Pyo), 0 – 1 mM of plumbagin (PL), menadione (MD; same amounts as PL), and phenazine methosulfate (PMS)] were added to exponentially grown S. coelicolor wild type cells (OD ~ 0.4 in YEME) for 30 min. To assess SoxR activation, the amount of its direct target gene transcript (SCO2478) was analyzed by S1 nuclease mapping. The level of gene expression relative to the untreated level was quantified from at least three independent experiments and is presented at the bottom of each data set.

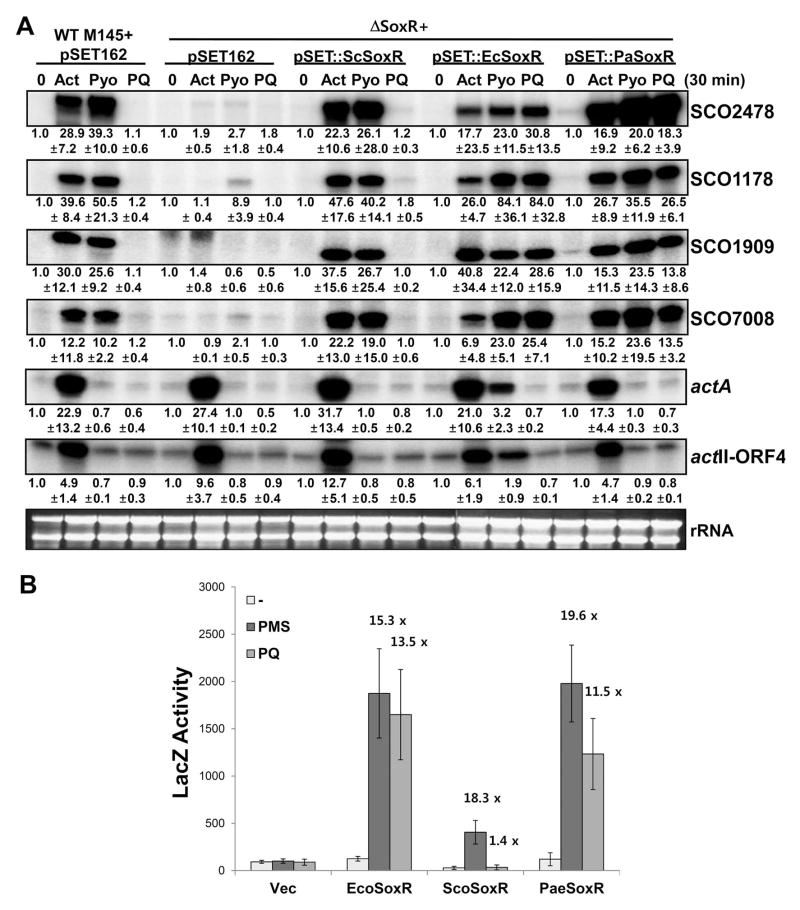

Fig. 5. Differential activation of ScSoxR, EcSoxR, and PaSoxR expressed in S. coelicolor or in E. coli.

(A) Activation profile in S. coelicolor cell background. Genes for ScSoxR, EcSoxR, and PaSoxR were cloned in the pSET-152-derived integration vector pSET162 and introduced into the ΔsoxR mutant strain of S. coelicolor. Since all these SoxRs share similar recognition sequences, we monitored the amount of SoxR target gene transcripts in S. coelicolor, as indicators of SoxR activation. Actinorhodin (Act; 500 nM), pyocyanin (Pyo; 100 μM), or paraquat (PQ; 200 μM) were added to exponentially growing S. coelicolor cells containing pSET162 vector, pSET162-ScSoxR, pSET162-EcSoxR, or pSET162-PaSoxR integrated at the att site in the chromosome. Gene-specific probes for SoxR targets (SCO2478, SCO1178, SCO1909, and SCO7008) were used for S1 mapping. As a control, transcripts known to be induced by actinorhodin (actA and actII-ORF4) were also measured. Relative expression levels were obtained from at least three independent experiments and are presented at the bottom of each dataset.

(B) Activation profile in the E. coli cell background. Genes for ScSoxR, EcSoxR, and PaSoxR were cloned in the multi-copy pTac4 plasmid. The recombinant plasmids were introduced into a ΔsoxR E. coli GC4468 strain that contains the soxSp-driven β-galactosidase (LacZ) reporter gene in the chromosome. The transformed cells were grown in LB to early exponential phase (OD600 ~ 0.2) and either were left untreated or were treated with 200 μM of PQ or 50 μM of PMS for 60 min, followed by β-galactosidase activity assay. The mean values of activity in Miller units were obtained from three independent experiments. For each transformant, the induction fold relative to untreated level is indicated on top of graphic bar.

Why treatment with high concentrations of PL, MD, and PMS for 30 min were not effective to induce SoxR target genes is not clear. We found that these treatments do not always inhibit mRNA synthesis, since some inducible promoters are activated by the treatment (data not shown). It is conceivable that high dose of these oxidants limit the supply and/or function of transcriptional machinery for the SoxR-dependent promoters, even when SoxR is activated. Currently, it is not known which sigma factor(s) directs transcription from SoxR-activated promoters, out of more than 60 sigma factors predicted in S. coelicolor. It is also conceivable that SoxR no longer is maintained as an active oxidized form at high concentrations of RACs, which could generate metabolic byproducts such as ROS that could facilitate breakdown of the [Fe-S] cluster.

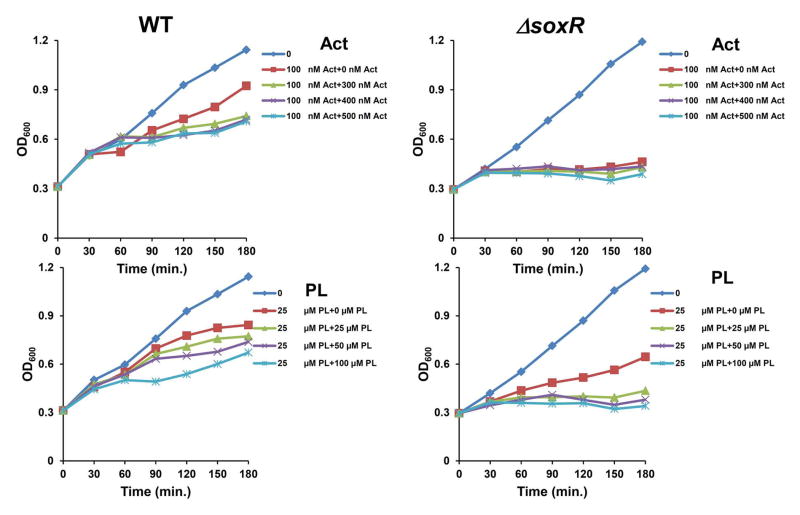

SoxR protects cells from the growth-inhibiting effects of SoxR-inducing chemicals

Whether the activation of SoxR plays any protective function against toxic inducing chemicals was examined by monitoring cellular growth in liquid media (YEME) through optical-density measurements. For this purpose, exponentially growing S. coelicolor wild type (M145) and ΔsoxR mutant cells (at OD600 ~0.3) were treated with lower doses of actinorhodin (100 nM) or plumbagin (25 μM) for 30 min, and they were then either unchallenged or challenged with higher concentrations of the same compound. The results in Fig. 3 clearly demonstrate that the ΔsoxR mutant experienced more severe growth inhibition than the wild type by these compounds. Thus the activation of SoxR by RACs in S. coelicolor confers resistance toward these chemicals.

Fig. 3. Role of SoxR in protecting S. coelicolor cells against actinorhodin and plumbagin.

YEME liquid medium was inoculated with 108 spores of the S. coelicolor M145 wild type and ΔsoxR mutant strains and was shaken at 180 rpm in an incubator at 30° C. When cultures reached mid exponential phase (OD600 ~ 0.3 – 0.4), either actinorhodin (Act; 100 nM) or plumbagin (PL; 25 μM) was added. After 30 min of inducing treatment, higher amounts of the same compounds (0, 300, 400, 500 nM Act, or 0, 25, 50, 100 μM PL) were added to the culture. Cell growth was subsequently monitored by measuring OD at 600 nm. Growth of non-treated cells was monitored in parallel. The data sets that are shown are representative of four independent experiments for each compound.

Differential sensitivity profile of SoxRs toward RACs in S. coelicolor, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa

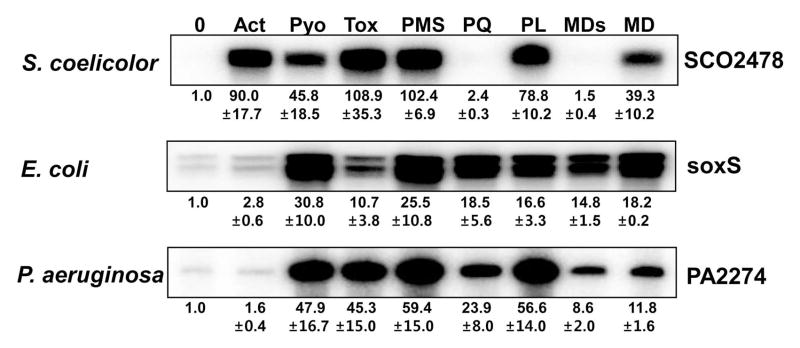

We then examined the induction of SoxR regulon by a variety of RACs presented in Fig. 1. Exponentially grown wild type cells of S. coelicolor (M145), E. coli (GC4468), and P. aeruginosa (PA14), at OD600 ~0.4–0.5 in YEME or LB liquid medium, were treated for 30 min with actinorhodin (Act; 200 nM), pyocyanin (Pyo; 10 μM), toxoflavin (Tox; 20 μM), phenazine methosulfate (PMS; 50 μM), paraquat (PQ; 200 μM), plumbagin (PL; 25 μM), menadione sodium bisulfite (MDs; 500 μM) or menadione (MD; 350 μM) before cell harvest. The activation of SoxR was estimated by the quantification of transcripts from a native target gene in each organism by S1 mapping. Results in Fig. 4 demonstrated that each organism responds to RACs in distinctly different ways. E. coli and P. aeruginosa did not respond to γ-actinorhodin by activating SoxR. This insensitivity, however, was due to a permeability barrier that prevented γ-actinorhodin from entering these organisms, as described below (Fig. 5). The SoxR system in E. coli and P. aeruginosa responded to all the other compounds that were examined, albeit with varying degree of induction. Even though PQ and MDs did not activate SoxR in S. coelicolor, they were effective in activating SoxRs in E. coli and P. aeruginosa. Since the SoxR induction profile in each organism is the combined result of permeability and in vivo effectiveness of each RAC, a uniform cellular environment is necessary to examine the species-specific activation behavior of each SoxR.

Fig. 4. Reactivity of SoxRs with a variety of RACs in wild type S. coelicolor (M145), E. coli (GC4468), and P. aeruginosa (PA14) cells.

Exponentially grown wild type cells (OD ~ 0.4 to 0.5) were treated with RACs for 30 min: Act 200 nM, Pyo 10 μM, Tox 20 μM, PMS 50 μM, PQ 200 μM, PL 25 μM, MDs 500 μM and MD 350 μM. The amount of SoxR target transcripts was then analyzed by S1 mapping for S. coelicolor (SCO2478), E. coli (soxS), and P. aeruginosa (PA2274). The soxS mRNA from E. coli produces two protected bands, the smaller of which is most likely generated from a processed species as observed by (Wu and Weiss, 1991). Relative expression levels were obtained from at least three independent experiments and are presented at the bottom of each data set.

Activation profile of three SoxR species expressed in S. coelicolor or in E. coli by various RACs

We then constructed recombinant strains of S. coelicolor, each of which expresses ScSoxR, EcSoxR, or PaSoxR from a chromosomally integrated gene in the ΔsoxR background. Either the wild type strain or a ΔsoxR mutant with an integrated parental vector (pSET162) was examined in parallel. Cells in mid-exponential culture (at OD600 of ~ 0.4–0.5) in YEME liquid media were treated with RACs for 30 min, and expression of four SoxR target genes encoding a putative NADPH-dependent reductase (SCO2478), an ABC transporter (SCO7008), a monooxygenase (SCO1909), and a hypothetical protein (SCO1178) was then examined by S1 mapping. As a control for actinorhodin-specific gene induction, we examined RNAs from the actinorhodin gene cluster, actA encoding actinorhodin transporter and actII-ORF4 encoding pathway-specific gene activator. The results in Fig. 5A demonstrated that Act (500 nM) and Pyo (10 μM) were effective in activating ScSoxR, whereas PQ (200 μM) was not. All three compounds were effective in activating EcSoxR as well as PaSoxR, as judged by induction of all four target genes. These experiments clearly demonstrate that the inability of γ-actinorhodin to activate SoxR in native E. coli and P. aeruginosa cells is most likely due to permeability problems. Effective activation of PaSoxR by paraquat in S. coelicolor coincides with what was observed in its native host.

We then exploited a LacZ reporter system in E. coli to monitor activation behavior of each SoxR species in another identical cellular background. Each soxR gene was cloned in the pTac4 vector and was introduced into an E. coli ΔsoxR mutant that harbors a soxS promoter::lacZ fusion gene. Transformed cells were grown to exponential phase and treated with either 50 μM PMS or 200 μM PQ for 1 h. LacZ activity was then measured. Fig. 5B shows that EcSoxR and PaSoxR were effectively induced by both PQ and PMS, whereas ScSoxR was induced only by PMS. The absolute value of LacZ activity was relatively low in ScSoxR-containing E. coli strain; however, the degree of induction was about 18-fold, as high as for EcSoxR and PaSoxR. Thus the activation profiles of SoxR species that had been observed in the S. coelicolor cellular environment were reproduced in the E. coli background.

We examined a broader range of RACs in the S. coelicolor cellular environment as described in Fig. 5A. We found that toxoflavin activated all three SoxR species (Fig. S1) and that menadione sodium sulfite (MDs) activated EcSoxR and PaSoxR while being ineffective for ScSoxR (Fig. S2). Examination of NO-generating compounds (SNP, DETA, and GSNO) demonstrated that ScSoxR was not activated by any of them, whereas EcSoxR was activated by all of them and PaSoxR was activated efficiently by SNP but not as well by other compounds (Fig. S3). All these results demonstrate that the three SoxR species show species-specific profiles of responses toward RACs. Overall, EcSoxR and PaSoxR both respond to a broader spectrum of oxidants, including paraquat, than does ScSoxR, which does not respond to PQ (a weak oxidant of low redox potential), MDs (a salt form of quinone with relatively high redox potential), or nitrosylating agents.

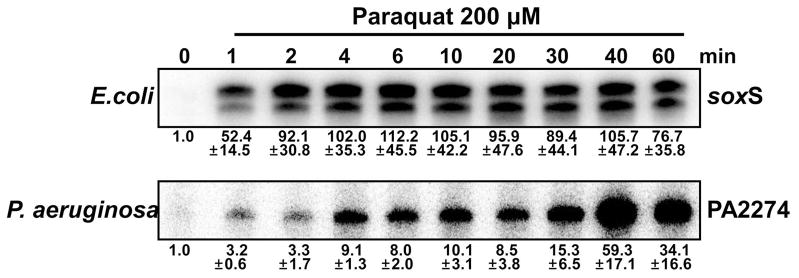

Time course of the activation of EcSoxR and PaSoxR by paraquat

Even though paraquat activates EcSoxR and PaSoxR, the extent of activation varies depending on experimental conditions. For example, paraquat activated PaSoxR in P. aeruginosa, but not as much as pyocyanin and PMS did (Fig. 4). It activated PaSoxR in S. coelicolor cell background as well as other RACs did (Fig. 5A), whereas it did so slightly less effectively in an E. coli cell background (Fig. 5B). This variable effect may arise from the relatively poor action of paraquat as a direct oxidant. We therefore examined whether there are any differences in the kinetics of EcSoxR and PaSoxR activation by paraquat in their native cell backgrounds. We found that whereas paraquat activated EcSoxR to its maximal level within 2 min of treatment, it activated PaSoxR more slowly, reaching the maximal level only after 40 min (Fig. 6). This difference explains the variable results obtained in different labs with different cell strains, culture conditions, and treatment protocols. Even with EcSoxR, which is effectively activated by paraquat, the kinetic experiments exhibited a large experimental fluctuation unless the treatment parameters such as duration and extent of aeration were standardized. The results in Fig. 6 also imply that SoxRs with similar redox potential values can exhibit different responses to a chemical, due to differences that affect the kinetics of the redox reaction. Menadione bisulfite reacted more slowly with PaSoxR than with EcSoxR, as observed for paraquat (Fig. S4).

Fig. 6. Time course of the activation of EcSoxR and PaSoxR by paraquat.

Exponentially grown E. coli or P. aeruginosa wild type cells (OD ~ 0.4 to 0.5) were treated with 200 μM paraquat. At intervals (1 to 60 min), RNA samples were harvested from each culture, and the amount of SoxR target transcripts was analyzed by S1 mapping for E. coli (soxS) and P. aeruginosa (PA2274). Relative expression levels were obtained from at least three independent experiments and are presented at the bottom of each data set

In vivo redox status of [2Fe-2S] cluster of SoxRs following oxidant treatment

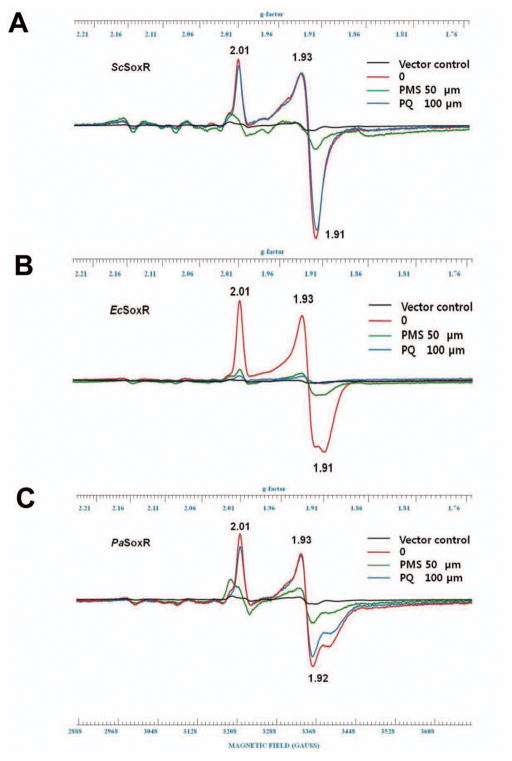

Whether the level of SoxR target gene transcripts indeed reflects the redox status of SoxR protein has not been examined for ScSoxR. Therefore, we monitored the redox status of ScSoxR overproduced in E. coli (XA90), by measuring X-band EPR spectra of the [2Fe-2S] cluster in the whole cell population at 15 K. EcSoxR and PaSoxR were measured in parallel for comparison. We observed that ScSoxR overproduced in an untreated cell sample demonstrated the characteristic spectral pattern of the reduced [2Fe–2S]1+ cluster. The cluster was oxidized to its EPR-silent state when the cells were treated with PMS (Fig. 7A). In contrast, treatment with PQ did not diminish the signal, confirming that the inability of PQ to activate ScSoxR is indeed due to its inability to oxidize the [2Fe–2S]1+ cluster of ScSoxR. EcSoxR overproduced in untreated E. coli cells gave rise to the characteristic EPR spectra reported previously (Fig. 7B; (Gu and Imlay, 2011, Gaudu et al., 1997, Ding and Demple, 1997). The spectra disappeared upon treatment with PQ and PMS. The EPR spectrum of PaSoxR was also similar to that of EcSoxR in untreated cells. PMS always silenced the spectral peaks, whereas the effect of PQ was somewhat variable. Data representative of four independent experiments is shown in Fig. 7C, demonstrating that PQ was partially effective in oxidizing the [2Fe-2S] cluster. This partial effect may lie behind the sub-maximal induction of PaSoxR by PQ in the E. coli cellular background (Fig. 5B) and may be the result of a slow reaction as implied from observations in Fig. 6. The EPR results thus correlate with the measurements of SoxR target RNAs as indicators of SoxR activation.

Fig. 7. Whole cell EPR analysis of overexpressed SoxRs in E. coli.

The redox status of the [2Fe-2S] clusters in ScSoxR, EcSoxR, and PaSoxR, which were overproduced in E. coli, was measured by EPR. The pTac4-based recombinant plasmids used in Fig. 5B were introduced into E. coli XA90 cells. Each transformant strain was grown aerobically in LB medium to an OD600 of 0.2, when IPTG was added, followed by further incubation at 37°C for more than 2 h or more until OD600 reached 0.8 to 1.0. Either PMS (50 μM) or PQ (100 μM) was then added, and cultures were further incubated at 37°C for 40 min with shaking. After washing and resuspension, intact cells were transferred to EPR tubes and quickly frozen on dry ice. EPR measurements were performed at 15 K as described in Experimental procedures. EPR spectra from ScSoxR (A), EcSoxR (B), and PaSoxR (C) following treatment with PMS (green line), PQ (blue), or none (red) are presented with g-values for representative peaks indicated. Control spectra (black) from cells with parental vector only were also included. Representative spectral data from four independent experiments for each SoxR species are shown.

Measurement of Redox Potential of ScSoxR

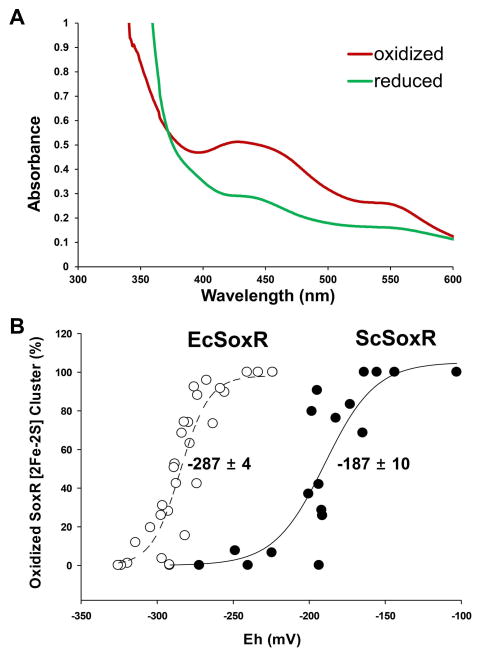

As an initial effort to find the mechanism behind the restricted reactivity of ScSoxR toward RACs, we set out to determine its redox potential by titration with sodium dithionite in the presence of the redox mediator safranin O (Massey, 1991), as described in Experimental procedures. For this purpose, ScSoxR and EcSoxR proteins were purified from E. coli and were resuspended to 10 μM each in anaerobically prepared buffer. The UV-VIS absorption spectrum of air-oxidized ScSoxR indicated characteristic [2Fe-2S] peaks which disappeared upon the addition of sodium dithionite (Fig. 8A). The [2Fe-2S] cluster of ScSoxR was reduced by adding varying amounts of sodium dithionite in the presence of safranin O (5 μM) at 29°C in anaerobic chamber. The redox potential of each solution was measured with a platinum and Ag/AgCl electrode (HACH-MTC101-1) and the redox status of SoxR was determined in the same solution by measurement of absorbance at 415 nm. Plots of the fraction of oxidized SoxR versus the redox potential (mV) of the solution revealed that the mid-point reduction potential of ScSoxR is −187 ± 10 mV (Fig. 8). This value is about 100 mV higher than the estimated redox potential of EcSoxR (−287 ± 4 mV), which was measured in parallel. The value for EcSoxR is close to what was reported already [−285 ± 10 mV, (Ding et al., 1996, Gaudu and Weiss, 1996)].

Fig. 8. Redox titration of purified SoxR proteins.

ScSoxR and EcSoxR proteins purified from E. coli were resuspended to 20 μM each in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8) containing 500 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, and 1 mM DTT in stoppered cuvettes. (A) Absorption spectra of oxidized and reduced ScSoxR were measured with UV-visible spectrophotometer. (B) The [2Fe-2S] cluster of the proteins were reduced in the presence of the redox mediator safranin O (5 μM) at 25°C by adding different amounts of sodium dithionite in anaerobic chamber. The redox potential of the solution was measured with a platinum and Ag/AgCl electrode (HACH-MTC101-1), and the amount of oxidized SoxR in the same solution was measured by taking spectrophotometric absorbance at 415 nm as described in Experimental procedures. Percent fraction of oxidized SoxR (y-axis) was plotted against redox potential (Eh in mV) of the solution. The mid-point reduction potential of ScSoxR and EcSoxR was estimated to be −187 ± 10 and −287 ± 4 mV, respectively. Data shown here are representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

In this work we demonstrated that ScSoxR responded to a limited range of chemicals, whereas PaSoxR and EcSoxR responded to nearly all or all redox-active chemicals (RACs), respectively. The activation of target gene expression by ScSoxR in response to RAC correlated with the oxidation of its [2Fe-2S] cluster by the effector chemical, as shown by whole cell EPR analysis. We also found that ScSoxR confers adaptive protection to the cell against growth-inhibitory effect of inducing chemicals.

What features of ScSoxR, in comparison with other SoxRs, determine its selective behavior? Regarding its insensitivity to paraquat, we believe that the relatively high redox potential of ScSoxR (−187 mV) in comparison with those of EcSoxR (−285 mV; (Ding et al., 1996, Gaudu and Weiss, 1996); this study) and PaSoxR (−290 mV; (Kobayashi and Tagawa, 2004)) makes it less favorable to get oxidized by the weak oxidant paraquat (−440 mV; (Steckhan and Kuwana, 1974)). One can wonder why PQ is able to oxidize SoxR if the reduction potential of SoxR is so much higher than that of PQ. There are two parts to this. First, the reduced PQ is quickly consumed by electron transfer to other, higher-potential acceptors--molecular oxygen or ubiquinone in the respiratory chain. Thus the uphill electron transfer is pulled forward by the downhill nature of the subsequent electron transfers. Second, the reduction potentials do affect the rate of the first electron transfer. The more uphill this reaction is, the slower it will be. The reaction is more uphill for ScSoxR than for EcSoxR.

In quantitative terms, electron transfer from −287 mV to −440 mV represents an uphill reaction of +3,528 cal, compared to +5,834 cal if the donor is at −187 mV. These positive free energies do not require that the reactions be slow; electron-transfer reactions with these positive free energies can nevertheless occur on very short time scales. [See the Supplementary Information for calculations.] The free energy difference between SoxR and paraquat will almost certainly constitute part of the energy of activation, and calculations indicate that the lower potential of EcSoxR could accelerate the reaction by as much as 40-fold relative to the higher potential of ScSoxR. Thus the potential difference is a compelling explanation for the different responsiveness of the SoxR proteins to paraquat. Of course, if there are structural differences that influence how easily an oxidant approaches the clusters, then this will have an additional effect.

As observed in our study, the redox potential cannot be the sole factor in determining selectivity, since menadione sodium bisulfite (MDs), which is a potent oxidant in terms of redox potential (−45 mV; (Hodnick and Sartorelli, 1997)), does not activate ScSoxR. The negative charge of MDs might impede the association of the compound with the redox area of SoxR. Therefore, the redox potential, which is an equilibrium value, could be a necessary factor in determining redox reaction, but not a sufficient factor. It can be hypothesized that the accessibility of the FeS center to reactive chemicals may differ among SoxRs, even though the [2Fe-2S] cluster is thought to be solvent-exposed, as determined for oxidized EcSoxR (Watanabe et al., 2008). The sensitivity of PaSoxR toward paraquat saliently supports this proposal. The redox-cycling weak oxidant paraquat can oxidize both PaSoxR and EcSoxR, whose FeS clusters are of similar redox potential. However, this study shows that PaSoxR responds more slowly to paraquat than does EcSoxR. This reveals the contribution of kinetic factors, such as accessibility and reactivity, in determining the feasibility of redox reaction between SoxR and RACs. The different kinetics of the redox reactions most likely explains why different labs observe different sensitivity patterns for redox-cycling weak oxidants, if the experimental conditions and lab strains are not standardized.

Then what determines the redox potential and kinetic reactivity of the [2Fe-2S] cluster in each SoxR? More study will be needed to delineate which residues or structural features affect the redox potential and which affect kinetic parameters. However, the combined contribution of redox potential and kinetic parameters is reflected in the overall reactivity or oxidizability of individual SoxR proteins by particular compounds. Using target RNA analysis to monitor SoxR activation, we examined the contribution of the long C-terminal tail (18 aa from residue 158 to 175) that is specific to ScSoxR (Fig. S5A). The results indicated that this C-terminal tail is not responsible for the insensitivity of ScSoxR to paraquat or MDs (Fig. S5B). This coincides with what was previously reported (Sheplock et al., 2013). However, the three key residues, whose mutation in PaSoxR to “enteric-type” residues increased its sensitivity toward paraquat and therefore were predicted to affect ScSoxR likewise (Sheplock et al., 2013), did not behave as predicted in S. coelicolor. In our hands, all three mutations (V65I, P85L, L126R) did not change the selectivity profile, and the P85L and L126R mutations made ScSoxR less active even toward strong oxidant PMS (Fig. S5C, D). How phyla-specific conserved residues among SoxRs would contribute to the selectivity is an interesting and promising question. In addition, previously identified residues that affect redox potential in EcSoxR could serve as a good basis to search for their contribution in other SoxRs (Hidalgo et al., 1997; Chander and Demple, 2004). Therefore, the residues and structural features that affect overall reactivity of SoxR toward RAC need be investigated in a more systematic way, preferably based on structural information.

The UV-VIS absorption spectrum of oxidized ScSoxR is similar but not identical to those of EcSoxR and PaSoxR (Wu et al., 1995, Kobayashi and Tagawa, 2004). The EPR spectrum of reduced [2Fe-2S] in ScSoxR differs slightly from those of EcSoxR and PaSoxR (Fig. 6). These discrepancies may reflect some subtle but significant differences in the environment of the FeS cluster in each SoxR. Differential responsiveness toward not only the redox-active compounds but also NO may be the result of these differences in the cluster environments. NO activates EcSoxR by nitrosylating the [2Fe-2S] cluster of EcSoxR, forming protein-bound dinitrosyl-iron-dithiol adducts (Ding and Demple, 2000). Considering its promiscuity, the FeS cluster of EcSoxR may be most exposed to solvent and/or its environment most flexible to accommodate any modifications of the cluster, compared with other SoxRs. The [2Fe-2S] cluster of ScSoxR may have a relatively restrictive environment that limits the accessibility and reactivity of the chemicals, and/or the sustainability of the oxidized/modified cluster to convey activation signal to the DNA-binding domain. In order to understand the features that determine the selectivity of reaction between [2Fe-2S] cluster of SoxRs and iron-reactive chemicals, careful systematic mutagenesis studies combined with physico-chemical analyses are in need.

Based on the relatively small number of regulated genes by PaSoxR or ScSoxR and the fact that they are activated by endogenous metabolites, it has been postulated that PaSoxR and ScSoxR are dedicated to responding to endogenous metabolites, in contrast to EcSoxR, which triggers a global stress response and responds to broad range of chemicals (Sheplock et al., 2013). Our observation that PaSoxR resembles EcSoxR more closely than ScSoxR suggests that this functional classification is not that simple. The finding that even ScSoxR responds both to endogenous and exogenous natural metabolites as well as to xenobiotics implies that these non-enteric SoxRs are not specific systems for endogenous metabolites only. The differential range of activating chemicals may be an evolutionary outcome that reflects the ecological habitats of their host bacteria. The presence of other transcriptional factors in the same cell that can provide protective function in response to different array of chemicals might also shape the spectrum of chemicals to which SoxR responds. Streptomycetes, which primarily inhabit the soil and encode a large number of transcription factors that can divide labor, as exemplified by more than 700 transcriptional regulators present in S. coelicolor (Bentley et al., 2002), could be best served by a SoxR of limited reactivity. On the other hand, pseudomonads, which are present rather ubiquitously from soil to human body, may be better off with a SoxR of broader reactivity. In order to understand the physiological role of non-enteric SoxR in further detail, genome-wide analysis of SoxR target genes and their functional analysis are needed in model organisms such as S. coelicolor as well as P. aeruginosa.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains, plasmids and culture conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table I. S. coelicolor A3(2) strain M145 (wild-type) and its mutants were grown in YEME liquid medium containing 5 mM MgCl2·6H2O and 10.3% sucrose at 30°C by inoculating spore suspension (Kieser et al., 2000). Cells were grown to mid-exponential phase to OD600 of 0.3–0.5 for treatment with chemicals and to prepare RNA. E. coli and P. aeruginosa cells were grown in LB medium at 37°C.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strains/plasmids | Relevant genotype and characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. coelicolor | ||

| M145 | SCP1− SCP2− | Kieser et al., 2000 |

| M145 ΔSoxR | M145 with a deletion in soxR | Shin et al. 2011 |

| M145 ΔSoxR::ScSoxR | M145 ΔSoxR::pSET162-pScSoxR-ScSoxR | This study |

| M145 ΔSoxR::EcSoxR | M145 ΔSoxR::pSET162-pScSoxR-EcSoxR | This study |

| M145 ΔSoxR::PaSoxR | M145 ΔSoxR::pSET162-pScSoxR-PaSoxR | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| XA90 | K-12 Δ(lac-pro) XII ara nalA argE(Am) thi Rif (F′ lacIq′ ZY proAB) | Hidalgo and Demple, 1994 |

| BL21 (λDE3) pLysS | fhuA2 [lon] ompT gal (λ DE3) [dcm] ΔhsdS λ DE3 = λ sBamHIo ΔEcoRI-B int::(lacI:: PlacUV5::T7 gene1) i21 Δnin5 | Lab culture stock |

| GC4468 | (argF-lac) 169 rpsL sup(Am) | Lab culture stock |

| GC4468 ΔsoxR | (argF-lac) 169 rpsL sup(Am) ΔsoxR::Kanr | This study |

| MS1343 | GC4468, soxSp::lacZ, Ampr | Koo et al. 2003. |

| MS1343 ΔsoxR | GC4468, soxSp::lacZ, Ampr ΔsoxR::Kanr | Koo et al. 2003. |

| ET12567 | F′ dam13::Tn9 dcm6 hsdM hsdR recF143::Tn10 galK2 galT22 ara-14 lacY1 xyl-5 leuB6 thi-1 tonA31 rpsL hisG4 tsx-78 mtl-1 glnV44 | MacNeil et al., 1992 |

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| PA14 | WT, Non-infectious strain | D. Newman (Dietrich et al., 2006) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSET162 | insertion of a thiostrepton resistance marker at SphI site of pSET152 (Apramycinr lacZa MCS reppUC) | Kim et al., 2006 |

| pSET162-pScSoxR-ScSoxR | pSET162 contain promoter of ScSoxR with Sc soxR gene | This study |

| pSET162-pScSoxR-EcSoxR | pSET162 contain promoter of ScSoxR with Ec soxR gene | This study |

| pSET162-pScSoxR-PaSoxR | pSET162 contain promoter of ScSoxR with Pa soxR gene | This study |

| pTac4 | pTac1 Ampr replaced with Chlr | This study |

| pTac4-ScSoxR | pTac4 vector contain Sc soxR gene | This study |

| pTac4-EcSoxR | pTac4 vector contain Ec soxR gene | This study |

| pTac4-PaSoxR | pTac4 vector contain Pa soxR gene | This study |

| pET15b | N-terminally histidine-tagged | Novagen |

| pET15b-ScSoxR | N-terminally 6 histidine-tagged S. coelicolor soxR gene in pET15b | This study |

| pET15b-EcSoxR | N-terminally 6 histidine-tagged E. coli soxR gene in pET15b | This study |

Chemical treatments

γ-actinorhodin (Act) was isolated from a surface culture of S. coelicolor M145 cells on YEME plates as described previously (Shin et al., 2011). The following chemicals were purchased from Sigma: pyocyanine (Pyo), methyl viologen (PQ), phenazine methosulfate (PMS), plumbagin (PL), menadione sodium bisulfite (MDs), menadione (MD), sodium nitroprusside (SNP), S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), diethylenetriamine/nitric oxide adduct (DETA-NO) and IPTG (Isopropyl β-D-1- thiogalactopyranoside). Toxoflavin (Tox) was kindly provided by Prof. Ingyu Hwang (Department of Agricultural Biotechnology and Center for Agricultural Biomaterials, SNU). Stock solutions were made fresh and were diluted to final indicated concentrations.

Construction of ΔsoxR strains expressing ScSoxR, EcSoxR, or PaSoxR

The ΔsoxR mutant of S. coelicolor (Shin et al., 2011) was transformed with pSET162-based recombinant plasmids containing ORFs for ScSoxR, EcSoxR, or PaSoxR. To construct the recombinant plasmids, DNA fragments containing the promoter of the S. coelicolor soxR gene (soxRp) and the coding sequences of the soxR genes from S. coelicolor, E. coli, or P. aeruginosa were amplified by PCR and cloned into the pGEM-Teasy plasmid (Promega). The 823, 707 and 715 bp long fragments containing the soxRp-soxR region were cut out with EcoRI and BamHI restriction enzymes and cloned into pSET162, which is a derivative of integration vector pSET152 with a thiostrepton resistance marker (Bierman et al., 1992). The pSET162-based recombinant plasmids were introduced into methylation-negative, conjugal host strain E. coli ET12567 and then transferred to the ΔsoxR mutant by bacterial conjugation. The proper chromosomal integration in exoconjugants that showed apramycinR and and thiostreptonR phenotypes was verified by genomic PCR analysis. For expression studies in E. coli, the ΔsoxR mutant of GC4468 strain (Table 1) was transformed with pTac4-based recombinant plasmids containing ORFs for ScSoxR, EcSoxR, or PaSoxR.

S1 nuclease mapping analysis

To prepare RNA S. coelicolor cells were grown in liquid YEME media containing 10.3% sucrose and 5 mM MgCl2 to OD600 of 0.4 – 0.5. RNAs were purified by acidic phenol extraction, after fixation of cells with RNAprotect® bacterial reagent (Qiagen). To prepare RNA from E. coli and P. aeruginosa, cells were grown in LB to OD600 of 0.4 – 0.5 before treatment with chemicals. Gene-specific S1 probes for actII-ORF4, actA, SCO2478, SCO7008, SCO1909, and SCO1178 were generated by PCR using S. coelicolor M145 genomic DNA as a template. The probes for soxS and PA2274 were generated by PCR using E. coli and P. aeruginosa genomic DNA as templates, respectively. The probe for actII-ORF4 spans from −92 (upstream) to +47 (downstream) nt position relative to the start codon, for actA from −114 to +69, for SCO2478 from −177 to +100, for SCO7008 from −162 to +138, for SCO1909 from −152 to +72, for SCO1178 from −168 to +73, for soxS −84 to +88 and for PA2274 −91 to +120. For each sample, RNA (50 – 100 μg) was hybridized at 50°C with gene-specific probes labeled with [γ-32P]-ATP. Hybridization and S1 nuclease mapping were carried out according to standard procedures (Kieser et al., 2000). Following S1 nuclease treatment, the protected DNA probes were loaded on 6% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea. The signal was detected and quantified by BAS-2500 (Fuji).

β-galactosidase assay

E. coli cells were grown in LB medium to an OD600 of 0.2 and was left either untreated or treated with 50 μM PMS or 200 μM paraquat for 1 h at 37°C, respectively. β-galactosidase activity was assayed by adding o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG) after permeabilization of the cell with SDS-chloroform (Miller, 1972.).

Bacterial growth and sensitivity assay

Liquid YEME medium containing 10.3% sucrose was inoculated with 108 spores each of the S. coelicolor wild type or the ΔsoxR mutant in a 1 L baffled flask, and the cultures were incubated at 30° C with shaking at 180 rpm. When the cultures reached an OD600 of about 0.3, lower doses of actinorhodin (100 nM) or plumbagin (25 μM) were added, and incubation continued for 30 min. Higher doses of the same compounds were then added, and the OD was measured every 30 min for 3 hrs.

EPR spectroscopy

For whole-cell EPR measurements, E. coli XA90 (Ding and Demple, 1997) cells containing either pTac4 or pTac4-based recombinant plasmids that overproduce ScSoxR, EcSoxR, or PaSoxR under the control of IPTG-inducible tac promoter (Koo et al., 2003) were grown in LB with chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml). When cells were grown to OD600 of 0.20, 0.5 mM IPTG was added, and cultures were further incubated at 37°C for 2 h or more until OD600 reached to 0.8 to 1.0. They were then left untreated or treated with redox-cycling drugs for 40 min. After treatments, cells were harvested, washed quickly with minimal salts (60 mM K2HPO4, 33.3mM KH2PO4, 7.6 mM (NH4)2SO4, 2.3 mM Na3C6H5O7.7H2O), and resuspended at 1/250th of the original culture volume in minimal salts containing 50% glycerol. Cell suspensions (300 μl each) were then transferred to EPR tubes and immediately frozen on dry ice. The expression level of SoxR in the soluble fraction of cells subjected to EPR analysis was confirmed on SDS–PAGE in a parallel experiment. EPR spectra of [2Fe–2S]+ clusters were obtained using a Varian E112 EPR spectrometer at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The following settings were used throughout the measurement: microwave power, 1 mW; microwave frequency, 9.05 GHz; modulation amplitude, 12.5 G at 100 KHz; time constant, 0.032; and sample temperature, 15 K.

Overproduction and purification of ScSoxR and EcSoxR proteins from E. coli BL21

The entire coding regions of the S. coelicolor soxR and E. coli soxR genes were amplified from corresponding genomic DNAs using mutagenic primers: ScSoxR-up (5′-GGT TCG AG C ATA TGC CTC AGA TTC -3′; Nde I site underlined) and ScSoxR-down (5′-GAC CGG GCC AGG ATC CCC GCG C -3′; BamHI site underlined). EcSoxR-up (5′-GAG GTG GAT CCA CAT ATG GAA AAG -3′; Nde I site underlined) and EcSoxR-down (5′-GCG CCC TGG ATC CGC TTT AGT TTT -3′; BamHI site underlined). The 590 bp for ScSoxR and 492 bp for EcSoxR PCR product was digested with NdeI and BamHI and cloned into pET15b vector (Novagen). The resulting recombinant plasmids (pET15b-ScSoxR and pET15b-EcSoxR) were transformed into E. coli BL21 (λDE3) pLysS. To purify SoxR proteins, transformants were grown in LB at 37°C to OD600 of 0.5 and induced with 0.5 mM (final concentration) isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 3 hrs at 30°C. His-tagged SoxR proteins were purified through nickel-charged NTA column (Novagen) as recommended by the manufacturer. Purified proteins were dialyzed against TGDN500 buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 1 mM DTT) and kept in the anaerobic chamber at 4°C until redox titration. The purity of the protein preparation was estimated through SDS-PAGE with Coomassie brilliant blue staining, and the final concentration was determined by Bradford assay.

Redox Titration of SoxR

Purified SoxR protein was diluted to 10 μM in TGDN500 buffer containing redox mediator safranin O (5 μM) in a stoppered cuvette of 1-mm path length. The amount of oxidized SoxR was estimated by measuring absorption at 415 nm in a UV-1650PC spectrophotometer (Shimadzu). Redox titration was done by adding different amount of sodium dithionite at 25°C. The redox potential of the solution at each addition of sodium dithionite was measured with a combined platinum and Ag/AgCl electrode (HACH-MTC101-1) in an anaerobic chamber. The fraction of oxidized SoxR in each redox condition was calculated as described previously (Kobayashi and Tagawa, 2004).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Ingyu Hwang (Department of Agricultural Biotechnology and Center for Agricultural Biomaterials, Seoul National University, Seoul) and You-Hee Cho for providing toxoflavin and pyocyanin, respectively, and Drs. Mark Nilges (Illinois EPR Research Center) and Mianzhi Gu (Department of Microbiology) of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for assistance with EPR experiments. This work was supported by a grant for Intelligent Synthetic Biology Center of Global Frontier Project by MEST for Laboratory of Molecular Microbiology to JH Roe (2011-0031960). KL Lee was supported by the second-stage BK21 fellowship for Life Sciences at SNU. Atul Kumar Singh is supported as a Korean Government Scholarship Grantee by Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. The EPR experiments were supported by grant GM49640 from the National Institutes of Health to J Imlay.

References

- Bentley SD, Chater KF, Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Challis GL, Thomson NR, James KD, Harris DE, Quail MA, Kieser H, Harper D, Bateman A, Brown S, Chandra G, Chen CW, Collins M, Cronin A, Fraser A, Goble A, Hidalgo J, Hornsby T, Howarth S, Huang CH, Kieser T, Larke L, Murphy L, Oliver K, O’Neil S, Rabbinowitsch E, Rajandream MA, Rutherford K, Rutter S, Seeger K, Saunders D, Sharp S, Squares R, Squares S, Taylor K, Warren T, Wietzorrek A, Woodward J, Barrell BG, Parkhill J, Hopwood DA. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Nature. 2002;417:141–147. doi: 10.1038/417141a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman M, Logan R, O’Brien K, Seno ET, Rao RN, Schoner BE. Plasmid cloning vectors for the conjugal transfer of DNA from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces spp. Gene. 1992;116:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard JL, Wholey WY, Conlon EM, Pomposiello PJ. Rapid changes in gene expression dynamics in response to superoxide reveal SoxRS-dependent and independent transcriptional networks. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chander M, Raducha-Grace L, Demple B. Transcription-defective soxR mutants of Escherichia coli: isolation and in vivo characterization. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2441–2450. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.8.2441-2450.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crack JC, Green J, Hutchings MI, Thomson AJ, Le Brun NE. Bacterial iron-sulfur regulatory proteins as biological sensor-switches. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:1215–1231. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dela Cruz R, Gao Y, Penumetcha S, Sheplock R, Weng K, Chander M. Expression of the Streptomyces coelicolor SoxR regulon is intimately linked with actinorhodin production. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:6428–6438. doi: 10.1128/JB.00916-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich LE, Kiley PJ. A shared mechanism of SoxR activation by redox-cycling compounds. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:1119–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich LE, Price-Whelan A, Petersen A, Whiteley M, Newman DK. The phenazine pyocyanin is a terminal signalling factor in the quorum sensing network of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:1308–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich LE, Teal TK, Price-Whelan A, Newman DK. Redox-active antibiotics control gene expression and community behavior in divergent bacteria. Science. 2008;321:1203–1206. doi: 10.1126/science.1160619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding H, Demple B. In vivo kinetics of a redox-regulated transcriptional switch. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8445–8449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding H, Demple B. Direct nitric oxide signal transduction via nitrosylation of iron-sulfur centers in the SoxR transcription activator. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5146–5150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding H, Hidalgo E, Demple B. The redox state of the [2Fe-2S] clusters in SoxR protein regulates its activity as a transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33173–33175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiamphungporn W, Charoenlap N, Vattanaviboon P, Mongkolsuk S. Agrobacterium tumefaciens soxR is involved in superoxide stress protection and also directly regulates superoxide-inducible expression of itself and a target gene. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:8669–8673. doi: 10.1128/JB.00856-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa M, Kobayashi K, Kozawa T. Direct Oxidation of the [2Fe-2S] Cluster in SoxR Protein by Superoxide: DISTINCT DIFFERENTIAL SENSITIVITY TO SUPEROXIDE-MEDIATED SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:35702–35708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.395079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudu P, Moon N, Weiss B. Regulation of the soxRS oxidative stress regulon. Reversible oxidation of the Fe-S centers of SoxR in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5082–5086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.5082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudu P, Weiss B. SoxR, a [2Fe-2S] transcription factor, is active only in its oxidized form. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:10094–10098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorodetsky AA, Dietrich LE, Lee PE, Demple B, Newman DK, Barton JK. DNA binding shifts the redox potential of the transcription factor SoxR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3684–3689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800093105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu M, Imlay JA. The SoxRS response of Escherichia coli is directly activated by redox-cycling drugs rather than by superoxide. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:1136–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07520.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo E, Demple B. An iron-sulfur center essential for transcriptional activation by the redox-sensing SoxR protein. Embo J. 1994;13:138–146. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo E, Ding H, Demple B. Redox signal transduction: mutations shifting [2Fe-2S] centers of the SoxR sensor-regulator to the oxidized form. Cell. 1997;88:121–129. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodnick WF, Sartorelli AC. Measurement of dicumarol-sensitive NADPH: (menadione-cytochrome c) oxidoreductase activity results in an artifactual assay of DT-diaphorase in cell sonicates. Anal Biochem. 1997;252:165–168. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Chater KF, Hopwood DA. Practical Streptomyces Genetics. John Innes Foundation; Norwich: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kim IK, Lee CJ, Kim MK, Kim JM, Kim JH, Yim HS, Cha SS, Kang SO. Crystal structure of the DNA-binding domain of BldD, a central regulator of aerial mycelium formation in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:1179–1193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Tagawa S. Activation of SoxR-dependent transcription in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biochem. 2004;136:607–615. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvh168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo MS, Lee JH, Rah SY, Yeo WS, Lee JW, Lee KL, Koh YS, Kang SO, Roe JH. A reducing system of the superoxide sensor SoxR in Escherichia coli. Embo J. 2003;22:2614–2622. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapp AR, Humbert MV, Carrillo N. The soxRS response of Escherichia coli can be induced in the absence of oxidative stress and oxygen by modulation of NADPH content. Microbiology. 2011;157:957–965. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.039461-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liochev SI, Fridovich I. Is superoxide able to induce SoxRS? Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:1813. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil DJ, Gewain KM, Ruby CL, Dezeny G, Gibbons PH, MacNeil T. Analysis of Streptomyces avermitilis genes required for avermectin biosynthesis utilizing a novel integration vector. Gene. 1992;111:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90603-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahavihakanont A, Charoenlap N, Namchaiw P, Eiamphungporn W, Chattrakarn S, Vattanaviboon P, Mongkolsuk S. Novel roles of SoxR, a transcriptional regulator from Xanthomonas campestris, in sensing redox-cycling drugs and regulating a protective gene that have overall implications for bacterial stress physiology and virulence on a host plant. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:209–217. doi: 10.1128/JB.05603-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey V. In: A simple method for the determination of redox potentials. Curti B, Ronchi S, Zanetti G, editors. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co; 1991. pp. 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Miller JH. A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics: A Laboratory Manual and Handbook for Escherichia coli and Related Bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Okegbe C, Sakhtah H, Sekedat MD, Price-Whelan A, Dietrich LE. Redox eustress: roles for redox-active metabolites in bacterial signaling and behavior. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;16:658–667. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma M, Zurita J, Ferreras JA, Worgall S, Larone DH, Shi L, Campagne F, Quadri LE. Pseudomonas aeruginosa SoxR does not conform to the archetypal paradigm for SoxR-dependent regulation of the bacterial oxidative stress adaptive response. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2958–2966. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2958-2966.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park W, Pena-Llopis S, Lee Y, Demple B. Regulation of superoxide stress in Pseudomonas putida KT2440 is different from the SoxR paradigm in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomposiello PJ, Bennik MH, Demple B. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of the Escherichia coli responses to superoxide stress and sodium salicylate. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3890–3902. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.13.3890-3902.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomposiello PJ, Demple B. Identification of SoxS-regulated genes in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:23–29. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.1.23-29.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheplock R, Recinos DA, Mackow N, Dietrich LE, Chander M. Species-specific residues calibrate SoxR sensitivity to redox-active molecules. Mol Microbiol. 2013;87:368–381. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JH, Singh AK, Cheon DJ, Roe JH. Activation of the SoxR regulon in Streptomyces coelicolor by the extracellular form of the pigmented antibiotic actinorhodin. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:75–81. doi: 10.1128/JB.00965-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steckhan E, Kuwana T. Spectrochemical study of mediators. I Bipyridylium salts and their electron transfer rates to cytochrome C. Berichte der Bunsen-Gesellschaft für physikalische Chemie. 1974;78:253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S, Kita A, Kobayashi K, Miki K. Crystal structure of the [2Fe-2S] oxidative-stress sensor SoxR bound to DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4121–4126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709188105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Dunham WR, Weiss B. Overproduction and physical characterization of SoxR, a [2Fe-2S] protein that governs an oxidative response regulon in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10323–10327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.10323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Weiss B. Two divergently transcribed genes, soxR and soxS, control a superoxide response regulon of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2864–2871. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.2864-2871.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.