Abstract

Background:

Congenital hypothyroidism (CH) considered a common endocrine disorder in Iran. We report the epidemiologic findings of CH screening program in Isfahan, seven years after its development, regarding the prevalence of transient CH (TCH) and its screening properties comparing with permanent CH (PCH).

Materials and Methods:

In this cross-sectional study, children with primary diagnosis of CH were studied. Considering screening and follow-up lab data and the decision of pediatric endocrinologists, the final diagnosis of TCH was determined.

Results:

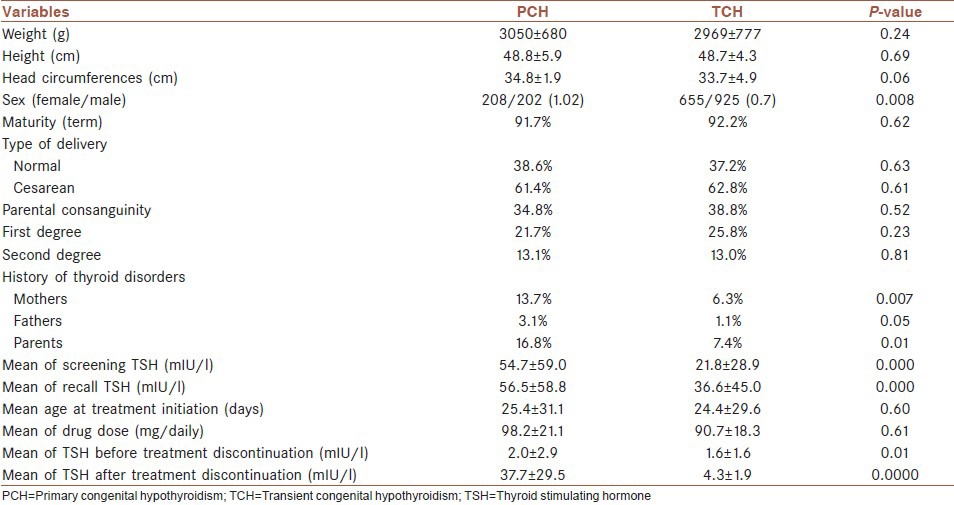

A total of 464,648 neonates were screened. The coverage percent of the CH screening and recall rate was 98.9 and 2.1%, respectively. Out of which, 1,990 neonates were diagnosed with primary CH. TCH was diagnosed in 1,580 neonates. The prevalence of TCH was 1 in 294 live births. 79.4% of patients with primary CH had TCH. Mean of screening (54.7 ± 59.0 in PCH vs 21.8 ± 28.9 in TCH), recall (56.5 ± 58.8 in PCH vs 36.6 ± 45.0 in TCH), and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and mean of TSH before (2.0 ± 2.9 in PCH vs 1.6 ± 1.6 in TCH) and after (37.7 ± 29.5 in PCH vs 4.3 ± 1.9 in TCH) discontinuing treatment at 3 years of age was significantly higher in PCH than TCH (P < 0.0000).

Conclusion:

The higher rate of CH in Isfahan is mainly due to the transient form of the disease. Further studies for evaluating the role of other environmental, autoimmune and/or genetic factors in the pathophysiology of the disease is warranted.

Keywords: Congenital hypothyroidism, permanent, transient

INTRODUCTION

Congenital hypothyroidism (CH), the preventable cause of mental retardation in children, is considered as the most common endocrine and metabolism disorder among pediatric population.[1] CH screening programs worldwide made an appropriate opportunity for early detection and treatment of the disorder and consequently prevention of its related neurodevelopmental complications.[2]

Though early treatment of all primarily diagnosed CH patients is crucial for their normal development, but continuity of the treatment after 3 years of age depends on permanency of CH. Deficiency of thyroid hormone could be persistent or temporary which represent as permanent and transient CH (PCH and TCH). Patients with PCH need lifelong hormone replacement therapy, whereas in TCH the duration of treatment is shorter (few months or first years of life).[3]

TCH may be due to the factors such as iodine deficiency or excess, maternal thyroid-blocking hormone receptor antibodies (TRBAbs), maternal use of antithyroid drugs, gene mutations such as dual oxidase 2 (DUOX 2) mutations, prematurity, and factors which affect the pituitary including drugs, prematurity, and maternal untreated hyperthyroidism.[4,5,6] Though some of the conditions do not need treatment and their effects are temporary, but others such as TRBAbs, antithyroid drugs, iodine deficiency, or excess need treatment for months up to years.[7]

There is a great variability in the reported prevalence rate of TCH worldwide due to different definition of TCH in screening protocols as well as differences in environmental, genetic, and ethnic factors.[8]

Since the initiation of CH screening and implementation of nationwide CH screening program in Iran, different results have been reported regarding the prevalence of CH and its transient form. Accordingly, CH is considered as a common endocrine disorder in Iran with higher prevalence rate than other countries.[9,10,11]

On the other hand, some recent studies reported an increased incidence rate for CH in several countries. The suggested potential causes of the observation have reported factors such as increased rate of TCH and improved clinical and paraclinical diagnosis of the disorder.[12,13] It seems that TCH may be one of the probable cause of high rate of CH in Iran, also. There are controversial results regarding the prevalence of TCH in Iran.[14,15,16] In a pilot study in Isfahan city before nationwide CH screening program among small sample size of primarily diagnosed CH patients, 40.2% of patient with primary CH had TCH after 3 years follow-up.[15]

In addition to its higher prevalence, proper management of patients with TCH is an important challenging issue in CH screening program.

Considering that the epidemiology of the disorder could help us in better understanding of the pathophysiology of CH and improving its screening process, in this study we report the epidemiologic findings of CH screening program in Isfahan, 7 years after its development, regarding the prevalence of TCH and its screening properties comparing with PCH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this cross-sectional study, children with primary diagnosis of CH referred to Isfahan Endocrine and Metabolism Research Center and all health centers in Isfahan province for treatment and follow-up from March 2002 to September 2009, were enrolled.

The Medical Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol (research project number: 392116).

All children were recalled. They clinically examined and their medical files were reviewed by a pediatric endocrinologist. The medical file of each patient consists of three parts: Demographic, CH screening, and follow-up data. Considering screening and follow-up lab data, radiologic findings, and the decision of pediatric endocrinologists; the final diagnosis of PCH and TCH was determined. Then demographic, screening, and follow-up data of patients with PCH and TCH was recorded and compared.

In almost all cases, the diagnosis was provided by the physician (general practitioner or a pediatrician); but in some controversial and conflicting cases the endocrinologist made the decision.

In fact, during reviewing the medical files of the patients; the endocrinologist checked and confirmed the diagnosis of all patients.

In cases with missing data, the data was completed.

CH screening in Isfahan

From May 2002 to April 2005, thyroxine (T4) and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) serum concentrations of all 3-7-day-old newborns were measured by radioimmunoassay (RIA) and immunoradiometric assay (IRMA), respectively, using Kavoshyar (Iran-Tehran) kits. Thyroid function tests were performed by Berthold-LB2111 unit gamma counter equipment using serum samples. In this period neonates with TSH >20 were recalled.

After implementation of nationwide CH screening program in Iran in April 2005, screening was performed using filter paper. Neonates with TSH >10 were recalled and those with abnormal T4 and TSH levels on their second measurements (TSH >10 mIU/l and T4< 6.5 μg/dl) were diagnosed as CH patient and received treatment and regular follow-up.

Levothyroxine (LT4) was prescribed for hypothyroid neonates at a dose of 10-15 mg/kg/day as soon as the diagnosis was confirmed. Neonates with CH were followed-up according to the CH screening guideline for appropriate treatment regarding the level of TSH, T4, height, weight, and other supplementary tests. Monitoring of TSH and T4 was done every 1-2 months during the 1st year of life and every 1-3 months during the 2nd and 3rd years.[17]

In accordance with screening program, in order to provide a similar treatment and follow-up protocol, two to three workshops annually was held in different cities of the province.

Cases of PCH and TCH were determined at the age of 3 years by measuring TSH and T4 concentrations 4 weeks after withdrawal of LT4 therapy. Patients with normal TSH level (TSH <10) considered as TCH. Patients with elevated TSH levels (TSH >10 mIU/l) and decreased T4 levels (T4< 6.5 mg/dl) were considered as PCH sufferers.[17]

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS; Release 20.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Data normality was verified using the Kolgomorov-Smirnov test and the homogeneity of variance was verified using the Levene's test. Depending on the type of distribution assigned to the data and also variances homogeneity between comparing groups, the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's test or in a case of a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Tukey's test was used (P < 0.05). The t-test and/or Mann-Whitney were used to compare means between different two groups. In the meanwhile, the categorical results were analyzed by the chi-square test and/or Fisher's exact test.

RESULTS

During the period of this study 464, 648 neonates screened in Isfahan province. The coverage percent of the CH screening was 98.9%. The rate of recall was 2.1%. A total of 1,990 neonates were diagnosed with primary CH. Reevaluation of the recorded data and final diagnosis of PCH and TCH in cases with primary CH took 18 months. PCH and TCH were diagnosed in 410 and 1,580 neonates, respectively. The prevalence of PCH and TCH was 1 in 1,133 and 1 in 294 live births, respectively. 79.4% of patients with primary CH had TCH.

Comparison of demographic and screening characteristics of patients with PCH and TCH is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and screening characteristics of patients with PCH and TCH

DISCUSSION

The results of our study determined that the higher prevalence of CH in Isfahan province is mainly due to the higher rate of TCH with a prevalence rate of 1 in 294 live births.

TCH considered an important issue in CH because of the following reasons; the treatment and follow-up of patients with TCH is challenging.[18] There are concerns about the risk of undertreatment on neonates’ neurophysiologic development as well as the side effects and risks of unnecessary hormonal replacement therapy including hyperactivity, advancement of bone age, etc. However, evidences from different studies showed that treatment is recommended in suspicious cases. Moreover, many studies indicated that even transient thyroid function abnormalities are associated with long-term neuropsychologic adverse effect and patients with TCH may represent thyroid dysfunction later in life, so early treatment and regular follow-up of the patients after 3 years of age is recommended.[19]

Moreover, TCH could prevent properly if its etiologic factors detect and managed properly. Considering that most of the factors responsible for TCH are preventable, the goal will be achieved if baseline epidemiological studies provide in each region. So, in this study we design to determine its prevalence in Isfahan after 7 years of CH screening initiation.

There is great variability in the reports regarding the prevalence of TCH worldwide. It seems to be more prevalent in Europe with a reported rate of 1 in 100 live births than the USA with a reported rate of 1 in 50,000 live births.[20]

The reported rate of TCH in different cities of Iran is different also. Prevalence of TCH in Babol (north part of Iran) and Fars province (central part of Iran) are reported as 1 in 1,754 and 1 in 3,151 live birth, respectively.[16,21] Ordookhani and colleagues in Tehran have reported an incidence rate of 1 in 5,845 live birth.[14]

In our previous study in Isfahan city during 2002-2005, the prevalence of TCH was 1 in 1,114.[15] Mentioned study was performed before nationwide CH screening in Isfahan city among 256 primarily diagnosed CH patients.

In this study, prevalence of TCH in Isfahan province was significantly high (1 in 294 live births). In our study, 79.4% of primarily diagnosed CH patients were diagnosed as TCH.

In a study in USA, Eugster, et al., have indicated that from 33 children with primary diagnosed CH, 12 (36%) had TCH.[22] The proportion was 50% in the study of Nair, et al., in India and 46.4% in the study of Karamizadeh and colleagues in Shiraz-Iran.[21,23]

Observed variability in reported prevalence rate of TCH may be due to the effect of different causes of TCH in each region as well as differences in ethnic and environmental factors. Though many known factors such as iodine deficiency or excess, autoimmunity and some genetic factors have been identified as the causative factors of TCH, but it seems that different unknown environmental factors such as micronutrients deficiency or other factors related to the water or soil could be the probable cause of TCH.

Though iodine deficiency considered the most common cause of CH in Iran before iodine supplementation,[10,24] but considering that the problem is resolved in Iran and since 1997 our region considered as iodine replete area;[25] so, it could not be a risk factor. Previously,we have studied the urine and milk iodine concentration in patients with CH and control normal group of neonates. Our results indicated that iodine excess could be a risk factor for higher prevalence of CH or TCH.[26] Further studies with larger sample size including other cities of Isfahan province is recommended.

Ordookhani and colleagues have investigated the etiologies of TCH in Tehran and Damavand. They showed that the most probable cause was iodine excess which should be investigated in future studies and other factors such as parental consanguinity, mode of delivery, goitrogens, iodine exposure, or thyrotropin receptor autoantibodies had no significant role in this regard.[27]

The higher rate of TCH in Europe may be due to iodine deficiency.[28]

Regarding the role of other etiologic factors of TCH, some studies have been implemented in Isfahan. A study in Isfahan demonstrated that DOUX 2 mutation as a genetic cause for TCH had no significant role in the etiology of TCH in Isfahan.[29]

Likewise other studies; the role of TRBAbs in the etiology of CH has been confirmed in a study in Isfahan.[30,31] According to mentioned study, the prevalence of TRBAbs was higher both in CH patients and their mothers and there was significant association between them. They concluded that autoimmunity has an important role in the etiology of CH. It is recommended for obtaining more accurate result and similar study in larger scale has been designed for patients with TCH.[31]

The higher prevalence of TCH in Isfahan may be due to the mentioned unknown environmental factors which needs a further investigation.

Mean of screening and recall TSH and before and after treatment discontinuation at 3 years of age was significantly lower in TCH than PCH. The results were similar to previous studies in this field.[15,21,32]

Prematurity is considered as a risk factor for TCH. Gaudino, et al., indicated that prematurity was more prevalent among neonates with TCH.[20] In this study, there was no significant difference between TCH and PCH regarding maturity. It seems that other causes of TCH have more important role in our patients with TCH than prematurity.

Regarding sex ratio and TCH, previous studies showed that though the female to male ratio is higher in PCH and the proportion is higher in those with agenesis of thyroid gland, but the ratio is lower in TCH. The ratio is reported to be 2:1 in PCH and 0.5:1 in TCH.[33,34] However, it seems that sex ratio in CH patients varies in populations with different ethnicity and race.[35] In current study the ratio was 1.01 and 0.7 for PCH and TCH, respectively.

In this study the prevalence of thyroid disorders among parents was significantly higher in patients with PCH than those with TCH. Regarding maternal antithyroid drug use, our data was not satisfactory. The parents could not provide us the details of their medication and most of them did not cooperate in reporting the details of their disease. This considers the limitation of current study.

Reviewing the result of current study, the higher rate of CH in Isfahan is mainly due to the transient form of the disease. It is suggested that factors such as iodine excess or autoimmunity could have role in the etiology of TCH in Isfahan. Further studies for evaluating the role of other environmental, autoimmune, and/or genetic factors in the pathophysiology of the disease is warranted.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rastogi MV, LaFranchi SH. Congenital hypothyroidism. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Büyükgebiz A. Newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2013;5(Suppl 1):8–12. doi: 10.4274/Jcrpe.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abduljabbar MA, Afifi AM. Congenital hypothyroidism. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2012;25:13–29. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2011.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delange F. Neonatal screening for congenital hypothyroidism: Results and perspectives. Horm Res. 1997;48:51–61. doi: 10.1159/000185485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhavani N. Transient congenital hypothyroidism. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;15(Suppl 2):S117–20. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.83345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hulur I, Hermanns P, Nestoris C, Heger S, Refetoff S, Pohlenz J, et al. A single copy of the recently identified dual oxidase maturation factor (DUOXA) 1 gene produces only mild transient hypothyroidism in a patient with a novel biallelic DUOXA2 mutation and monoallelic DUOXA1 deletion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E841–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parks JS, Lin M, Grosse SD, Hinton CF, Drummond-Borg M, Borgfeld L, et al. The impact of transient hypothyroidism on the increasing rate of congenital hypothyroidism in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;125(Suppl 2):S54–63. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1975F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Newborn Screening Information System. Definition for transient hypothyroidism. [Last accessed on 2010 Jan 11]. Available from: http://www2.uthscsa.edu/nsis/ReportDefinitions.cfm?reportyear_2008&testgroup_Y&te stid_43&grouplevel_D&typegroup_1 .

- 9.Ordookhani A, Mirmiran P, Hedayati M, Hajipour R, Azizi F. Screening for congenital hypothyroidism in Tehran and Damavand: An interim report on descriptive and etiologic findings, 1998-2001. Iran J Endocrinol Metab. 2002;4:153–60. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karimzadeh Z, Amirhakimi GH. Incidence of congenital hypothyroidism in Fars province, Iran. Iran Med Sci. 1992;17:78–80. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashemipour M, Amini M, Iranpour R, Sadri GH, Javaheri N, Haghighi S, et al. Prevalence of congenital hypothyroidism in Isfahan, Iran: Results of a survey on 20,000 neonates. Horm Res. 2004;62:79–83. doi: 10.1159/000079392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell ML, Hsu HW, Sahai I Massachusetts Pediatric Endocrine Work Group. The increased incidence of congenital hypothyroidism: Fact or fancy? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011;75:806–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurinczuk JJ, Bower C, Lewis B, Byrne G. Congenital hypothyroidism in Western Australia 1981-1998. J Paediatr Child Health. 2002;38:187–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2002.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ordookhani A, Mirmiran P, Pourafkari M, Neshandar-Asl E, Fotouhi F, Hedayati M, et al. Permanent and transient neonatal hypothyroidism in Tehran. Iran J Endoc Metabol. 2004;6:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashemipour M, Hovsepian S, Kelishadi R, Iranpour R, Hadian R, Haghighi S, et al. Permanent and transient congenital hypothyroidism in Isfahan-Iran. J Med Screen. 2009;16:11–6. doi: 10.1258/jms.2009.008090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haghshenas M, Zahed Pasha Y, Ahmadpour-Kacho M, Ghazanfari S. Prevalence of permanent and transient congenital hypothyroidism in Babol City-Iran. Med Glas (Zenica) 2012;9:341–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hashemipour M, Dehkordi EH, Hovsepian S, Amini M, Hosseiny L. Outcome of congenitally hypothyroid screening program in Isfahan: Iran from prevention to treatment. Int J Prev Med. 2010;1:92–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olney RS, Grosse SD, Vogt RF., Jr Prevalence of congenital hypothyroidism – current trends and future directions: Workshop summary. Pediatrics. 2010;125(Suppl 2):S31–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1975C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rose SR, Brown RS, et al. American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Endocrinology and Committee on Genetics, American Thyroid Association, Public Health Committee. Update of newborn screen-ing and therapy for congenital hypothyroidism. Pediatrics. 2006;117:2290–303. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaudino R, Garel C, Czernichow P, Léger J. Proportion of various types of thyroid disorders among newborns with congenital hypothyroidism and normally located gland: A regional cohort study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2005;62:444–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karamizadeh Z, Dalili S, Sanei-Far H, Karamifard H, Mohammadi H, Amirhakimi G. Does congenital hypothyroidism have different etiologies in Iran? Iran J Pediatr. 2011;21:188–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eugster EA, LeMay D, Zerin JM, Pescovitz OH. Definitive diagnosis in children with congenital hypothyroidism. J Pediatr. 2004;144:643–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nair PS, Sobhakumar S, Kailas L. Diagnostic re-evaluation of children with congenital hypothyroidism. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:757–60. doi: 10.1007/s13312-010-0115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ordoukhani A, Mirsaiid Ghazi A, Hajipour R, Mirmiran P, Hedayati M, Azizi F. Screening for congenital hypothyroidism: Before and after iodine supplementation in Iran. Iran J Endocrinol Metab. 2000;2:93–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Regional meeting for the promotion of iodized salt in the Eastern Mediterranean, Middle East and North African Region, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 10-21 April. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hashemipour M, Nasri P, Hovsepian S, Hadian R, Heidari K, Attar HM, et al. Urine and milk iodine concentrations in healthy and congenitally hypothyroid neonates and their mothers. Endokrynol Pol. 2010;61:371–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ordookhani A, Pearce EN, Mirmiran P, Azizi F, Braverman LE. Transient congenital hypothyroidism in an iodine-replete area is not related to parental consanguinity, mode of delivery, goitrogens, iodine exposure, or thyrotropin receptor autoantibodies. J Endocrinol Invest. 2008;31:29–34. doi: 10.1007/BF03345563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown RS. 6th ed. UK: Wiley Blackwell; 2009. The Thyroid in Brook's clinical pediatric endocrinology; p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rostampour N, Tajaddini MH, Hashemipour M, Salehi M, Feizi A, Haghjooy S, et al. Mutations of Dual Oxidase 2 (DUOX2) Gene among patients with Permanent and Transient Congenital Hypothyroidism. Pak J Med Sci. 2012;28:287–92. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ordookhani A, Mirmiran P, Walfish PG, Azizi F. Transient neonatal hypothyroidism is associated with elevated serum anti-thyroglobulin antibody levels in newborns and their mothers. J Pediatr. 2007;150:315–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hashemipour M, Abari SS, Mostofizadeh N, Haghjooy-Javanmard S, Esmail N, Hovsepian S, et al. The role of maternal thyroid stimulating hormone receptor blocking antibodies in the etiology of congenital hypothyroidism in Isfahan, Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:128–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown RS, Bellisario RL, Botero D, Fournier L, Abrams CA, Cowger ML, et al. Incidence of transient congenital hypothyroidism due to maternal thyrotropin receptor-blocking antibodies in over one million babies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:1147–51. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.3.8772590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medda E, Olivieri A, Stazi MA, Grandolfo ME, Fazzini C, Baserga M, et al. Risk factors for congenital hypothyroidism: Results of a population case-control study (1997-2003) Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;153:765–73. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oakley GA, Muir T, Ray M, Girdwood RW, Kennedy R, Donaldson MD. Increased incidence of congenital malformations in children with transient thyroid-stimulating hormone elevation on neonatal screening. J Pediatr. 1998;132:726–30. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hinton CF, Harris KB, Borgfeld L, Drummond-Borg M, Eaton R, Lorey F, et al. Trends in incidence rates of congenital hypothyroidism related to select demographic factors: Data from the United States, California, Massachusetts, New York, and Texas. Pediatrics. 2010;125(Suppl 2):S37–47. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1975D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]