Abstract

In Iran, a large group of patients are elderly people and they intend to have natural remedies as treatment. These remedies are rooted in historical of Persian and humoral medicine with a backbone of more than 1000 years. The current study was conducted to draw together medieval pharmacological information related to geriatric medicine from some of the most often manuscripts of traditional Persian medicine. Moreover, we investigated the efficacy of medicinal plants through a search of the PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar databases. In the medieval Persian documents, digestible and a small amount of food such as chicken broth, honey, fig and plum at frequent intervals as well as body massage and morning unctioning are highly recommended. In the field of pharmacotherapy, 35 herbs related to 25 families were identified. Plants were classified as tonic, anti-aging, appetizer, memory and mood enhancer, topical analgesic and laxative as well as health improvement agents. Other than historical elucidation, this paper presents medical and pharmacological approaches that medieval Persian practitioners applied to deal with geriatric complications.

Keywords: Geriatric medicine, herbal therapy, medieval persia

INTRODUCTION

Geriatric medicine or clinical gerontology, as a branch of medical sciences specifically deals with health problems as well as care and treatment of older people.[1] Becoming a prominent issue, this branch aims to improve function, overcome environmental problems and keep older adults healthy in normal activities.[2] Since the population of older adults is increasing even two to three fold during the first century of this millennium,[3] attempts to improve the aspects of geriatric medicine is enhanced.

Geriatric patients are defined as a group of patients over 65 years, but frail with multiple comorbidities and various functional impairments.[4] Excessive decline in body mass, reduction in walking performance and presence of exhaustion as well as fatigue are associated with the aging process in geriatric patients.[5] In addition to these conditions, geriatric persons also suffer from different chronic diseases that affect their life.[6]

As a natural and universal process, aging is accompanied with many biological changes.[7] These changes encompass progressive decrease in physiological functions and increase in disabilities. This gradual decline affected by dietary, environment, life-style and genetic factors.[7] Accordingly various medications need to be considered for this period of age and also older adults are the major user group of medications.[8] However, it should be noted that the medical approach can hardly help the elderly people alone and additionally other aspects of management are needed to be considered.[9] Therefore, complementary and integrative medical and pharmacological approaches can be beneficial in the improvement of geriatric medicine.

Various traditional and complementary systems of medicine such as Unani, Indian, Chinese and Persian have been contributed to the promotion of medical sciences.[10] Many documents containing information on geriatric medicine can be found from these systems of medicine.[7] Medical manuscripts authored by medieval Persian practitioners, which are not only a summation of other traditional medical systems information, but also a collection of their own experiences[11] involve beneficial findings about geriatric medicine.

In this regard, present paper attempted to draw together medieval pharmacological information and those recommended treatments related to geriatric medicine from some of the most often manuscripts of traditional Persian medicine (TPM).

METHODS

The employed study method of the present paper was based on the investigation of the remaining manuscripts of Persian medicine during 10th-18th century AD. Therefore, pharmacological information related to geriatric medicine was collected by searching through six important pharmacopeias of Persian medicine.

These manuscripts are Liber Continents by Rhazes (9th and 10th centuries), Alabnieh an haghaegh-ol-advieh by Aboo mansour Heravi (11th century), The Canon of medicine by Avicenna (10th and 11th centuries), Ikhtiyarat-e-Badiyee by Zein al-Din Attar Ansari Shirazi (14th century), Tohfat ol Moemenin by Mohammad Tonkaboni (17th century) and Makhzan- ol-Advieh by Aghili-Shirazi (18th century).[12,13,14,15,16,17] In addition, some medical textbooks of medieval Persian medicine were also studied to derive traditional important facts for older adults.

Other books such as “matching the old medicinal plant names with scientific terminology,”[18] “dictionary of medicinal plants,”[19] “dictionary of Iranian plant names,”[20] “popular medicinal plants of Iran,”[21] “Pharmacographia indica”[22] and “Indian medicinal plants”[23] were studied for nomenclature of medicinal plants.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In Persian medical manuscripts chapter related to geriatric medicine is generally mentioned under a subject namely “Tadbeer-e-mashayekh” or elderly devise. There, the physiology of senescence is meticulously discussed in terms of principal fundamentals such as temperament, humors, spirits, faculties or forces and functions.[24]

Early Persian physicians classified the growth and development stages into four main steps. First step is defined as growth period or pediatric stage. Second is the youth period and midlife stage is considered as the third stage. Accordingly, the last step is introduced as the old stage with is starting at the age of 60. Due to the fundamentals of humoral medicine, it was believed that people in the old ages have a cold and dry temperament and it bounds to change easily by extrinsic and intrinsic affecting factors.[7,25]

Taken as a whole, Persian practitioners believed that older adults should have light, easily digestible and a small amount of food at frequent intervals in their regimen.[26] As constipation is more common and usual in the elderly,[27] it was said that the bowels should be kept soft by the administration of mild laxative food or fruits such as chicken broth, honey, fig, plum and etc., Vegetables such as carrot and cabbage as well as fruits such as grapes and citruses have been also introduced beneficial. Furthermore, boiled milk was defined as a proper meal for old people especially if it is associated with honey.[25] In contrast fruits, food and additives such as eggplant, beef and vinegar should be used in low amounts. Body massage, morning unctioning with popular oils such as olive, almond, lily and sesame oil as well as light exercise were highly recommended in Persian manuscripts.[13,26] These approaches are likely useful in disorders such as vertigo, constipation and insomnia.[7] In addition to these facts, Persian scholars have recommended adequate sleep during the day and night for older adults.[13,25]

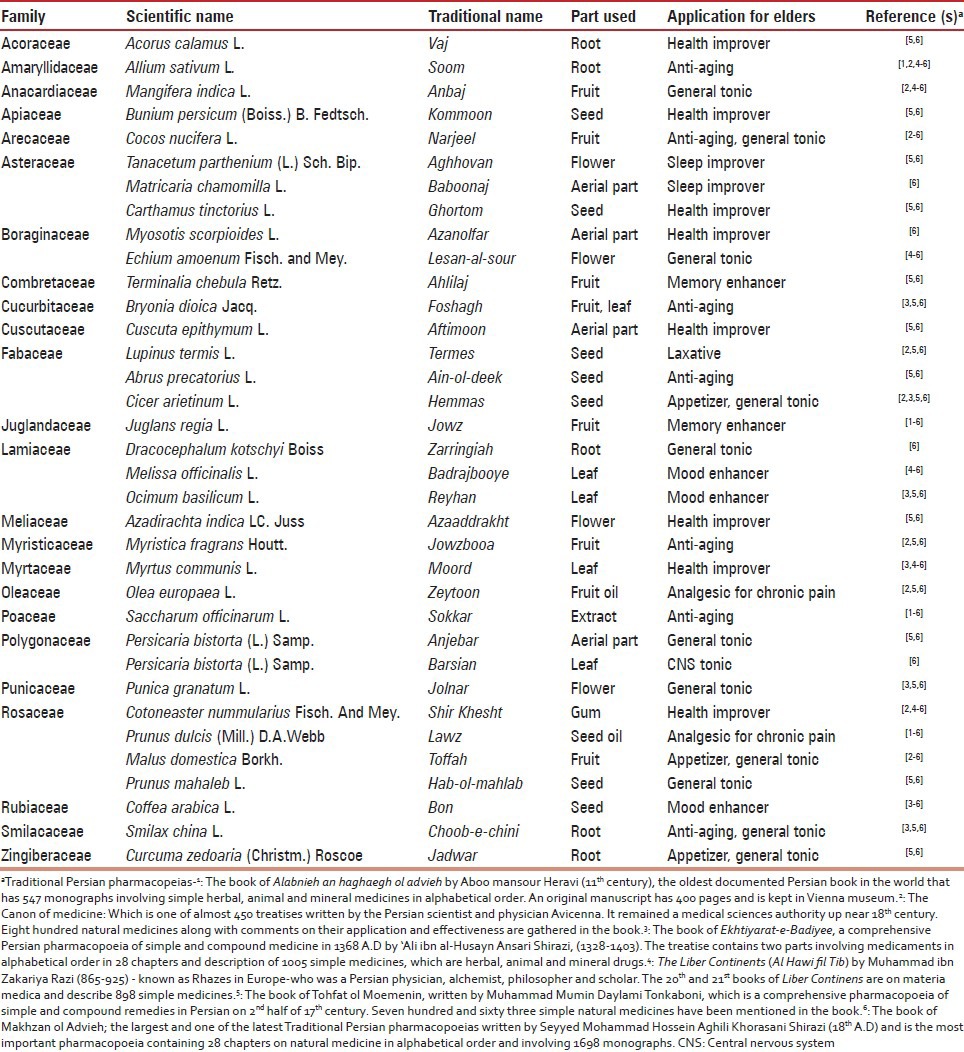

Persian medieval scholars have recommended medicinal herbs in addition to routine dietary of an old patient. According to their recommendations, plants related to geriatric medicine are classified into tonic, anti-aging, appetizer, memory and mood enhancer, topical analgesic and laxative as well as health improvement agents.[12,25,26] A total of 35 mentioned herbs regarding to twenty five plant families are derived from selected pharmacopeias of traditional medicine. The family Rosaceae is the one which involves most cited medicinal plants related to geriatric medicine. Applicable herbs of Asteraceae, Lamiaceae and Fabaceae are cited subsequently [Table 1].

Table 1.

Herbal geriatric remedies used in medieval Persia

It should be noted that a tremendous part related to geriatric medicine deals with preventive approaches. Therefore, a large group of medications and supplements for the geriatric stage may be represented as anti-aging agents as well as health enhancers.[8]

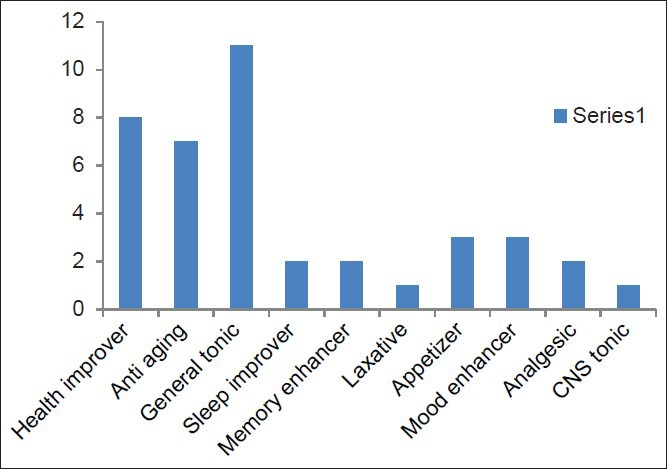

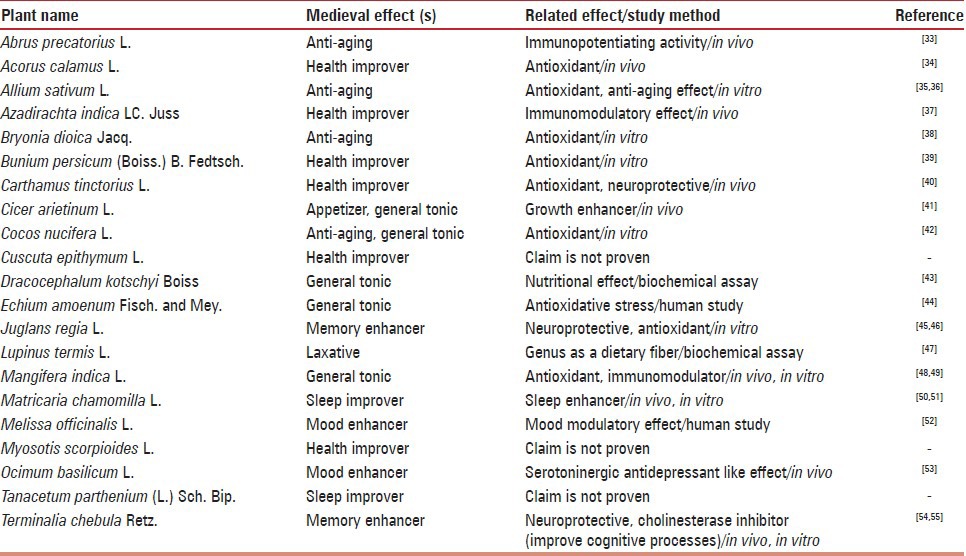

According to the Persian pharmaceutical manuscripts, cited medicinal plants are mostly mentioned to have anti-aging, health improvement and tonic effectiveness [Figure 1]. Although the anti-aging activity of anti-oxidant agents are not well-accepted, but it is remarked that agents having antioxidant or immunomodulatory effects can be considered as anti-aging supplement.[28,29,30] Therefore, it seems that herbs, which were traditionally administered as anti-aging medicine or remarked to be a health improver [Table 1] may have antioxidant activity [Table 2]. In addition to anti-aging properties of antioxidant agent, they are also said to have memory enhancing as well as cholinesterase inhibitor properties.[31,32] Table 2 reports studies in line with clinical properties, which were traditionally introduced by Persian practitioners as well. In this regard, most cited herbs exhibit antioxidant effects, which are followed by immunomodulatory and neuroprotective activity. Meanwhile, most related investigations in contemporary medicine are carried out under an animal study method. Only in two studies, evaluation was done as a human study and clinical trial. Therefore, further investigation is needed to be performed.

Figure 1.

Pharmacological contribution of geriatric medicinal herbs reported by traditional persian medicine

Table 2.

Evaluation of herbs medieval properties using modern scientific methods

CONCLUSION

Obviously, there are many possible targets and available approaches related to TPM that might help to develop new and effective medical managements for geriatric medicine. As for other traditional systems of medicine, such information is based on centuries of experience in medieval Persia and offers detailed explanations of the skillful approaches that show the importance of this field in medieval medicine.

Beside historical elucidation, this paper presents medical and pharmacological approaches that medieval Persian practitioners applied to deal with geriatric complications. Considering the hopeful results related to these medieval findings through scientific methods can help to carry out more comprehensive and effective investigations in the field of geriatric medicine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Authors of this manuscript wish to express their thanks to Research Institute for Islamic and Complementary Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Health Services for providing the grant of this project (Project Number: 959).[55]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dhar HL. Emerging geriatric challenge. J Assoc Physicians India. 2005;53:867–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Espinoza S, Walston JD. Frailty in older adults: Insights and interventions. Cleve Clin J Med. 2005;72:1105–12. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.72.12.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobsen LA, Kent M, Lee M. America's aging population. Popul Bull. 2011;66:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hilmer SN, McLachlan AJ, Le Couteur DG. Clinical pharmacology in the geriatric patient. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2007;21:217–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2007.00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–56. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zekry D, Loures Valle BH, Lardi C, Graf C, Michel JP, Gold G, et al. Geriatrics index of comorbidity was the most accurate predictor of death in geriatric hospital among six comorbidity scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1036–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hussain SA, Khan AB, Siddiqui MY, Latafat T, Kidwai T. Geriatrics and Unani medicine-A critical review. Anc Sci Life. 2002;22:13–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLean AJ, Le Couteur DG. Aging biology and geriatric clinical pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56:163–84. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pon J, Lai M. Adapting Canadian healthcare to an aging population. UBC Medical Journal. 2011;3:5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmad S, Rehman S, Ahmad AM, Siddiqui KM, Shaukat S, Khan MS, et al. Khamiras, a natural cardiac tonic: An overview. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2010;2:93–9. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.67009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khaleghi Ghadiri M, Gorji A. Natural remedies for impotence in medieval Persia. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16:80–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shirazi SA. Tehran: Publications and Education Islamic Revolution Press (Intisharat va Amoozesh Enghelab Islami); 1992. Storehouse of Medicaments (Makhzan ol advieh) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhazes, editor. Tehran: Academy of Medical Sciences; 2005. The Comprehensive Book on Medicine (Al Havi or Liber Continens) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sina A. New Delhi: Jamia Hamdard Printing Press; 1998. (Avicenna). Canon of medicine (Al Qanun Fil Tibb) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shirazi ZA. Tehran: Pakhsh Razi Press; 1992. Ikhtiyarat-e-Badiyee. Rewrited by Mir MT. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tonekaboni H. Tehran: Research Center of Traditional Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Nashre Shahr Press; 2007. The Present for the Faithful (Tohfat ol momenin) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heravi A. Tehran: Tehran University Press; 1992. The book of remedies (Alabnie an Haghaegh ol Advieh) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghahraman A, Okhovvat A. Tehran: Tehran University Press; 2004. Matching the old medicinal plant names with scientific terminology. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soltani A. Tehran: Arjmand Press; 2004. Dictionary of Medicinal Plants. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mozaffarian V. Tehran: Farhang Moaser Press; 2006. Dictionary of Iranian Plant Names. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amin G. Tehran: Tehran University Press; 2005. Popular Medicinal Plants of Iran. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dymook W, Warden CJ, Hooper D. London: Kegan Paul; 1893. Pharmacographica Indica. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khare C. US: Springer; 2007. Indian Medicinal Plants. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rezaeizadeh H, Alizadeh M, Naseri M, Ardakani MS. The traditional Iranian medicine point of view on health and disease. Iran J Public Health. 2009;38:169–72. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sina A. Tehran: Soroosh Press; 1988. (Avicenna). Canon of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jorjani S. Tehran: Tehran University Press; 2006. Medical objectives and excellent researches (Al-aghraz al-tebbieh va al-mabahes al-alayieh) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fosnes GS, Lydersen S, Farup PG. Effectiveness of laxatives in elderly: A cross sectional study in nursing homes. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:76. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-11-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fusco D, Colloca G, Lo Monaco MR, Cesari M. Effects of antioxidant supplementation on the aging process. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2:377–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamel NS, Gammack J, Cepeda O, Flaherty JH. Antioxidants and hormones as antiaging therapies: High hopes, disappointing results. Cleve Clin J Med. 2006;73:1049–56. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.73.12.1049. 1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ha W, Heng GB, Yu WY. Probiotics: Potential anti-aging capability. Zhong Guo Wei Sheng Tai Xue Za Zhi. 2009;21:374–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pepeu G, Giovannini MG. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memory. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;187:403–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ljubenkov I, Kri A, Juki M. Antioxidant and acetylcholinesterase inhibiting activity of several aqueous tea infusions in vitro. Food Technol Biotechnol. 2008;46:368–75. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramnath V, Kuttan G, Kuttan R. Immunopotentiating activity of abrin, a lectin from Abrus precatorius Linn. Indian J Exp Biol. 2002;40:910–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manikandan S, Srikumar R, Jeya Parthasarathy N, Sheela Devi R. Protective effect of Acorus calamus LINN on free radical scavengers and lipid peroxidation in discrete regions of brain against noise stress exposed rat. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:2327–30. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svendsen L, Rattan SI, Clark BF. Testing garlic for possible anti-ageing effects on long-term growth characteristics, morphology and macromolecular synthesis of human fibroblasts in culture. J Ethnopharmacol. 1994;43:125–33. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moriguchi T, Saito H, Nishiyama N. Anti-ageing effect of aged garlic extract in the inbred brain atrophy mouse model. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1997;24:235–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1997.tb01813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baral R, Chattopadhyay U. Neem (Azadirachta indica) leaf mediated immune activation causes prophylactic growth inhibition of murine Ehrlich carcinoma and B16 melanoma. Int Immunopharmacol. 2004;4:355–66. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morales P, Carvalho A, Sánchez-Mata M, Cámara M, Molina M, Ferreira I. Tocopherol composition and antioxidant activity of Spanish wild vegetables. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2012;59:851–63. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shahsavari N, Barzegar M, Sahari MA, Naghdibadi H. Antioxidant activity and chemical characterization of essential oil of Bunium persicum. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2008;63:183–8. doi: 10.1007/s11130-008-0091-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hiramatsu M, Takahashi T, Komatsu M, Kido T, Kasahara Y. Antioxidant and neuroprotective activities of Mogami-benibana (safflower, Carthamus tinctorius Linne) Neurochem Res. 2009;34:795–805. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9884-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nestares T, López-Frías M, Barrionuevo M, Urbano G. Nutritional assessment of raw and processed chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) protein in growing rats. J Agric Food Chem. 1996;44:2760–5. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mantena SK, Jagadish, Badduri SR, Siripurapu KB, Unnikrishnan MK. In vitro evaluation of antioxidant properties of Cocos nucifera Linn. water. Nahrung. 2003;47:126–31. doi: 10.1002/food.200390023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goli SA, Sahafi SM, Rashidi B, Rahimmalek M. Novel oilseed of Dracocephalum kotschyi with high n-3 to n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid ratio. Ind Crops Prod. 2013;43:188–93. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ranjbar A, Khorami S, Safarabadi M, Shahmoradi A, Malekirad AA, Vakilian K, et al. Antioxidant activity of Iranian Echium amoenum Fisch and C. A. Mey flower decoction in humans: A cross-sectional before/after clinical trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2006;3:469–73. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Orhan IE, Suntar IP, Akkol EK. In vitro neuroprotective effects of the leaf and fruit extracts of Juglans regia L. (walnut) through enzymes linked to Alzheimer's disease and antioxidant activity. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2011;62:781–6. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2011.585964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Z, Liao L, Moore J, Wu T, Wang Z. Antioxidant phenolic compounds from walnut kernels (Juglans regia L.) Food Chem. 2009;113:160–5. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Písaříková B, Zraly Z. Dietary fibre content in lupine (Lupinus albus L.) and soya (glycine max L.) seeds. Acta Vet Brno. 2010;79:211–6. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sánchez GM, Re L, Giuliani A, Núñez-Sellés AJ, Davison GP, León-Fernández OS. Protective effects of Mangifera indica L. extract, mangiferin and selected antioxidants against TPA-induced biomolecules oxidation and peritoneal macrophage activation in mice. Pharmacol Res. 2000;42:565–73. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2000.0727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.García D, Leiro J, Delgado R, Sanmartín ML, Ubeira FM. Mangifera indica L. extract (Vimang) and mangiferin modulate mouse humoral immune responses. Phytother Res. 2003;17:1182–7. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shinomiya K, Inoue T, Utsu Y, Tokunaga S, Masuoka T, Ohmori A, et al. Hypnotic activities of chamomile and passiflora extracts in sleep-disturbed rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:808–10. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Campbell EL, Chebib M, Johnston GA. The dietary flavonoids apigenin and (-)-epigallocatechin gallate enhance the positive modulation by diazepam of the activation by GABA of recombinant GABA (A) receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1631–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kennedy DO, Scholey AB, Tildesley NT, Perry EK, Wesnes KA. Modulation of mood and cognitive performance following acute administration of Melissa officinalis (lemon balm) Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;72:953–64. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00777-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abdoly M, Farnam A, Fathiazad F, Khaki A, Khaki AA, Ibrahimi A, et al. Antidepressant-like activities of Ocimum basilicum (sweet Basil) in the forced swimming test of rats exposed to electromagnetic field (EMF) Afr J Pharm Pharmacol. 2012;6:211–5. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chang CL, Lin CS. Phytochemical composition, antioxidant activity, and neuroprotective effect of Terminalia chebula retzius extracts. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/125247. 125247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nag G, De B. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of Terminalia chebula, Terminalia bellerica and Emblica officinalis and some phenolic compounds. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2011;13:121–4. [Google Scholar]