Abstract

Objective. To design and implement an elective therapeutics course and to assess its impact on students’ attainment of course outcomes and level of confidence in applying clinical pharmacy principles and pharmacotherapy knowledge.

Design. A 3-credit hour elective for third-year pharmacy students was structured to include problem-based learning (PBL), journal club and case presentations, and drug information activities.

Assessment. Student achievement of curricular outcomes was measured using performance on SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, plan) notes, case and journal club presentations, drug information activities, and peer evaluations. Results from a pre- and post-course survey instrument demonstrated significant improvement in students’ confidence in applying clinical pharmacy principles.

Conclusion. Students completing the course demonstrated increased attainment of course outcomes and confidence in their abilities to evaluate a patient case and make pharmacotherapeutic recommendations.

Keywords: problem-based learning, pharmacotherapy, literature evaluation, therapeutics, clinical pharmacy

INTRODUCTION

Standard 11 of the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) accreditation standards states that programs must use and integrate teaching and learning methods “fostering the development and maturation of critical thinking and problem-solving skills” and “enabling students to transition from dependent to active, self-directed, lifelong learners.” Further, ACPE accreditation standards stipulate that active-learning strategies be used throughout curricula to foster student learning and achievement of ability outcomes.1 Various implementations of active learning used to teach pharmacotherapeutic topics, including problem-based learning (PBL) in conjunction with case-based learning, have been described in pharmacy education.2 Application of skills has been suggested for teachers as a means of transitioning their concept of learning toward more consequential knowledge construction. A key strategy described to overcome barriers throughout a pharmacy curriculum is to provide numerous relevant examples.3

Along with ACPE’s standards, the educational outcomes developed by the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) address the need for courses in pharmacy curricula offering educational opportunities to provide patient-centered pharmaceutical care.4 Self-directed learning has been defined as “a process in which individuals take the initiative, with or without the help of others, in diagnosing their needs, formulating learning goals, identifying human and material resources for learning, choosing, and implementing appropriate learning strategies and evaluating learning outcomes.”5

Based on the experience of 4 clinical faculty members who also served as preceptors during advanced practice pharmacy experiences (APPEs), additional student-focused development in the area of self-directed learning and critical thinking was identified as a need at the University of Louisiana at Monroe College of Pharmacy (ULM COP). While student knowledge was deemed appropriate, students in classroom training seemed to lack confidence in applying their knowledge to patient care situations. To further prepare ULM pharmacy students to meet these outcomes, an elective course using PBL was developed and offered to third-year (P3) students.

Problem-based learning has been described as both a curriculum and a process that demands from the learner “acquisition of critical knowledge, problem-solving proficiency, self-directed learning strategies, and team participation skills.”5 Consistent features of PBL that have been identified include the presentation of a problem without providing the information necessary to solve it, small-group work, and guidance provided with feedback by a facilitator.6 In a previous study, students entering their APPE reported confidence in the material they had been taught using PBL, specifically medical information, basic science content regarding disease states, and patient-specific drug regimen evaluation.7

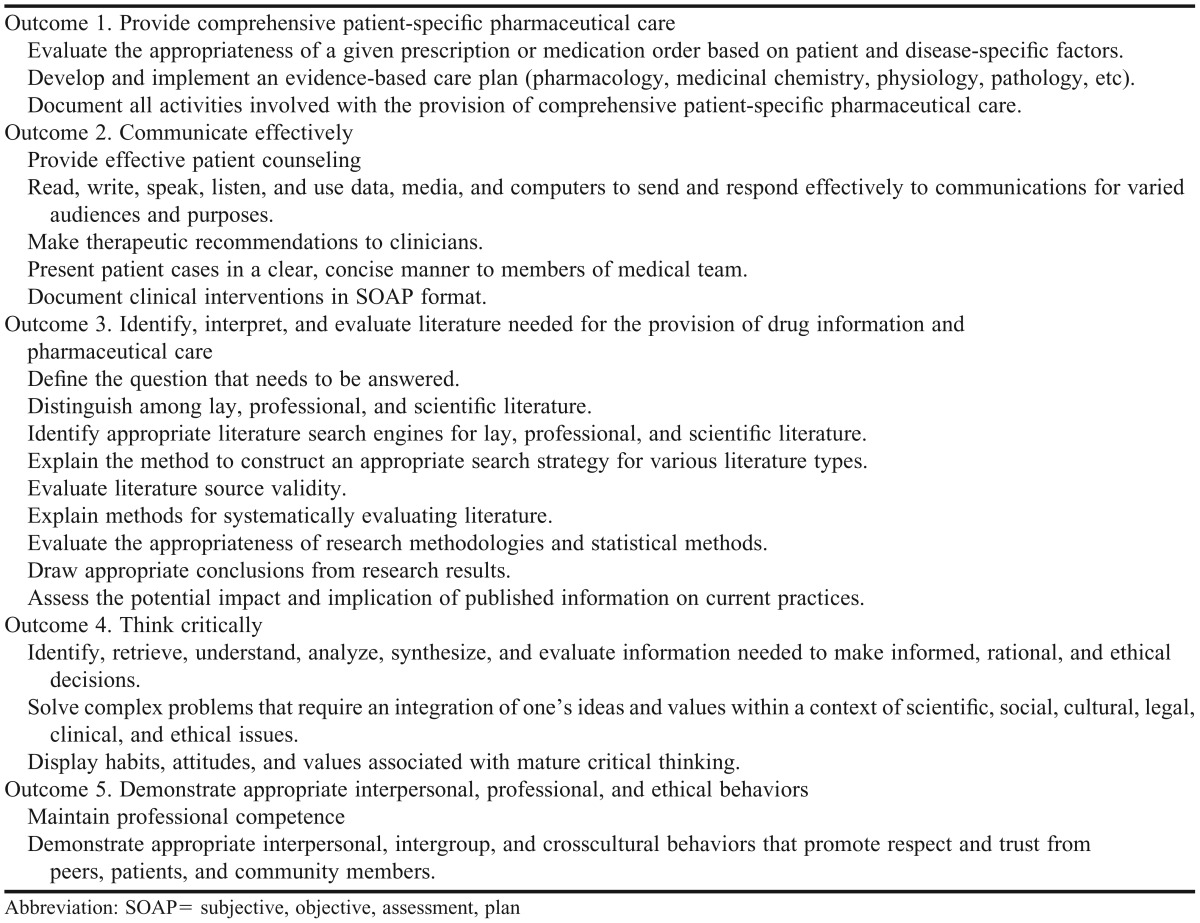

Bookstaver and colleagues described an elective course focusing on evidence-based medicine to improve student performance in APPEs.8 While there were several similarities to our course including a small class size and real-life patient case scenarios, the elective course described here differed in that it was designed to encourage self-directed learning and the enhancement of problem-solving skills in a PBL format. We describe the design and implementation of the first offering of the Problems in Therapeutics elective course and the impact of the elective course on students’ attainment of course outcomes (Table 1) and level of confidence related to problem-solving skills and application to patient care situations.

Table 1.

Curricular Outcomes and Objectives of an Elective Course Focusing on Application of Clinical Pharmacy Principles9

DESIGN

Problems in Therapeutics was a 15-week, 3-credit hour elective course offered to P3 students during the fall semester. Four faculty members at the level of assistant professor coordinated the course and were responsible for all course components. Two of the coordinators were practicing inpatient internal medicine pharmacists and the other 2 practiced in ambulatory care pharmacy, 1 in a family medicine clinic and the other in a viral diseases clinic.

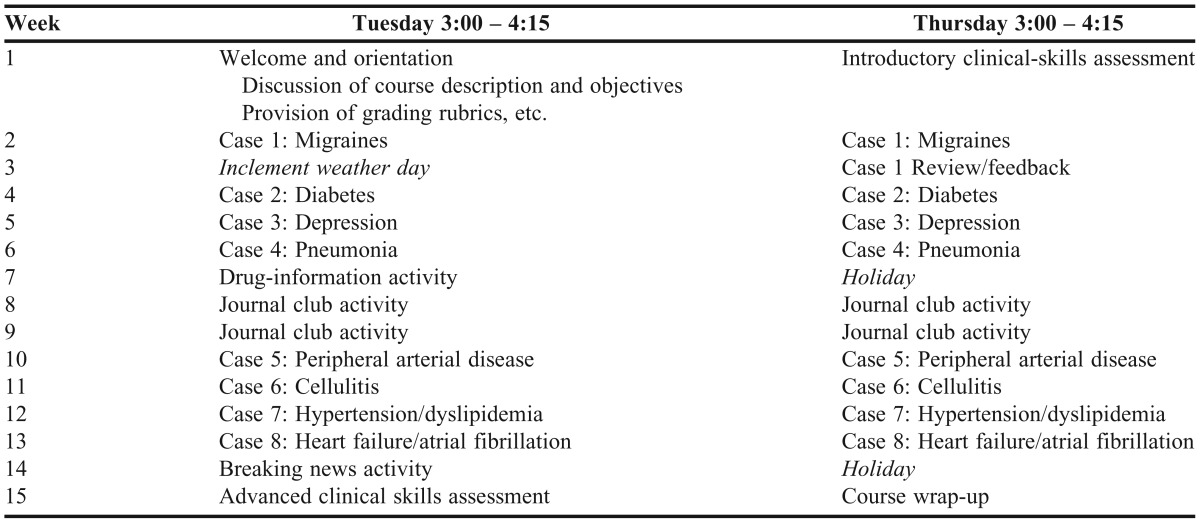

The content and structure of the course was intended to better prepare students for APPEs and postgraduate residency training. The components of the course included PBL with case presentations and SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, plan) notes, drug information responses, and literature evaluation. During the first session of the course, the faculty members described course expectations, grading, and procedures to the students. Initially, 9 cases were planned for the semester, but as shown in the completed schedule in Table 2, adjustments were made because of classes cancelled as a result of inclement weather. The course was designed so that most assignments could reasonably be completed during class time.

Table 2.

Schedule for an Elective Course Focusing on Application of Clinical Pharmacy Principles

The students spent the majority of the course (8 weeks) using the PBL format to evaluate patient cases and develop pharmaceutical care plans. The 9 students enrolled in the course were divided into 2 groups (4 and 5 students) using a random list generator (available at www.random.org).10 Each group was required to write a SOAP note corresponding to the patient case, with 1 group member randomly selected to formally present the patient case to the class. Students were given handouts on the first day of class regarding how to properly write a SOAP note and present a patient case; they were also given the rubrics that would be used for grading the SOAP notes and patient case presentations. The students did not have any prior knowledge of the content of the cases, but all pharmacotherapeutic topics included in cases had been previously covered in the curriculum. Thus, the cases served as a way for students to reinforce and apply their clinical knowledge. Each of the 4 faculty course coordinators was responsible for developing 2 cases and serving as the facilitator and grader during the weeks in which their cases were used.

The class met twice per week for 75 minutes. During the first weekly session, the students met in their assigned group. Each group was responsible for reviewing the case, researching necessary information, and working together to formulate an assessment and plan for the patient. In addition to this research, students had ample class time to begin writing their SOAP note. The facilitator was available to answer questions and provide guidance as necessary.

In the second weekly class session, the students were given approximately 30 minutes to finish their discussion of the case and finalize and submit their group’s SOAP note. Students also were required to complete peer evaluations of each of the other students’ contributions to the discussion and SOAP note. The second half of the class was used for patient case presentations. Prior to the start of the course, 1 student from each group was randomly chosen to present that week’s case; however, these assignments were not announced to the students until immediately prior to each presentation. Each student had the opportunity to present 2 times during the semester. The uncertainty regarding which week they would be called upon to present the case was a way of holding students accountable for contributing to their group’s work. After the case presentations, the facilitator asked questions and guided discussion regarding the case and each group’s assessment and plan.

Both the SOAP notes and case presentations were graded by the facilitator using a rubric to assess disease-state and drug-therapy knowledge, patient assessment, therapeutic plan development, and documentation. Presentation style and preparedness were also assessed during case presentations.11 In order to help control for inconsistencies in grading, the coordinators met prior to the semester to discuss potential discrepancies and subjectivity that could result from using the SOAP note and case presentation rubrics.

Two class sessions were used to practice drug-information retrieval, analysis, and presentation through drug information activities. These activities were designed to mimic actual scenarios in which pharmacists were asked questions and were required to formulate an appropriate response in a reasonable amount of time. This assignment gave students the opportunity to enhance their drug-information and literature-retrieval skills and their ability to analyze and evaluate information, and develop and present the answer to a patient or healthcare provider.

The first activity included drug information questions that a pharmacist might be asked by a physician or other healthcare provider. The faculty coordinators developed the questions for this activity. The second activity included drug information questions that a patient might ask a pharmacist. Each student was required to develop 2 questions for this activity and submit them approximately 1 week before the class.

For both activities, the questions were typed on slips of paper and drawn out of a cup by individual students at the beginning of class. Students were given 30 minutes during class to research their topic, analyze the information that they found, and formulate an evidence-based answer to their question. The remainder of the class was spent allowing each student approximately 5 minutes to present his/her question and answer to the class. A written response, including appropriate referencing, was due by 10:00 pm the night of the activity. A rubric was used to grade the activity based on appropriateness of answer and references, the written response, and presentation style. All course coordinators were present for the presentations and participated in grading and feedback.

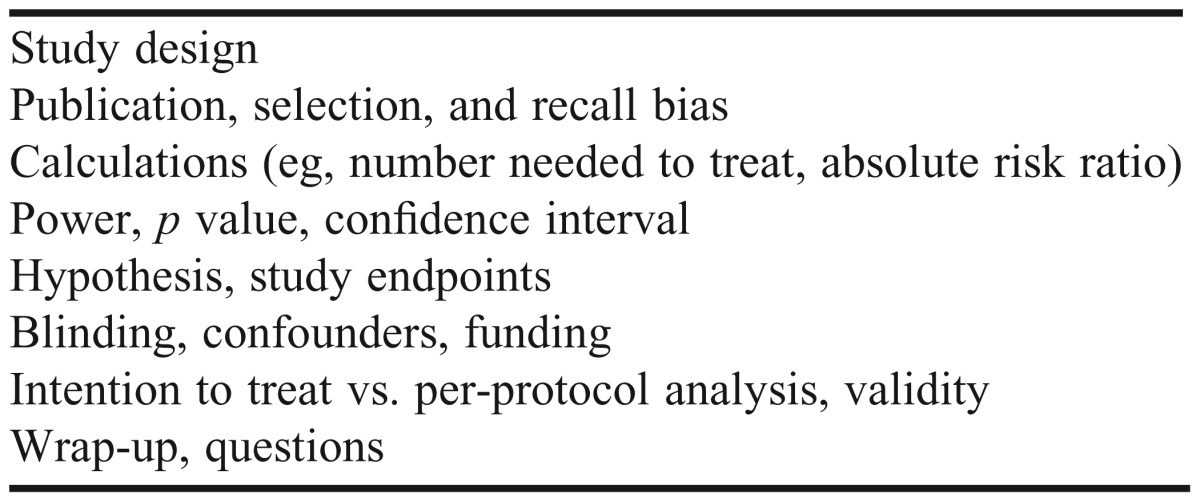

Literature evaluation and journal club activities were conducted during 4 class sessions and consisted of 3 components – review of literature evaluation concepts, example journal club presentation and article evaluation, and student journal club presentations. The coordinators developed an activity that used a format similar to “speed dating” to review literature evaluation concepts. Students were divided into groups of 2 or 3 and rotated in 8-minute intervals to 7 different stations at which various literature evaluation topics were discussed. Course coordinators led the discussion at each station, providing examples and reinforcing practical application of these concepts. The literature evaluation topics discussed are listed in Table 3. This activity was designed to reinforce literature evaluation concepts in a way in which students are actively stimulated and engaged.

Table 3.

Topics Used in a Literature Evaluation Activity in a Pharmacy Therapeutics Elective Course

In order to increase awareness of expectations and better prepare students to complete their own journal club presentation, 1 of the course coordinators presented 2 journal articles to the students that reported opposing results to the same clinical question. After the presentation, the faculty member led discussion regarding proper evaluation and critique of each article. The 2 subsequent class sessions were used for student journal club presentations – the first for preparation and the second for presentations. Prior to class, the students were divided into groups of 2 or 3 and assigned a journal article to evaluate and present as a group. Each group had approximately 10 minutes to present their article. A rubric was used to grade the activity, and all course coordinators attended the presentations and participated in grading and feedback.12

Students were also required to complete a clinical skills case on the first and last day of class. These cases were developed by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists for use in the annual Clinical Skills Competition, and the organization granted permission to the investigators to use the cases and keys in this project. A single, unblinded investigator graded both sets of cases to minimize the possibility of grading bias from the analysis. Because of the complexity of grading these cases, correct identification of clinical problems was the endpoint used in this portion of the course.

Grades for the course were based on student performance on the following: SOAP notes, case presentations, journal club presentation, drug information activities, and peer evaluations. Upon completion of Problems in Therapeutics, students were expected to be able to provide comprehensive patient-specific pharmaceutical care, think critically, communicate effectively, and identify, interpret, and evaluate literature needed for the provision of drug information and pharmaceutical care. These course outcomes aligned with the ULM College of Pharmacy Competency Statements and Educational Outcomes9 and were consistent with ACPE and CAPE outcomes promoting opportunities to provide patient-centered pharmaceutical care, the “maturation of critical thinking and problem-solving skills,” and “enabling students to transition from dependent to active, self-directed, lifelong learners.”1,4 One specific course objective was to improve students’ confidence in all aspects of effectively providing patient-specific pharmaceutical care. The course outcomes incorporated the highest level of learning, ie, evaluation, according to Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning.13 Also, all aspects of Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning (foundational knowledge, application, integration, human dimension, caring, learning how to learn) were incorporated in meeting the course outcomes.14 The Institutional Review Board at ULM approved all student and curricular assessment methods used.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

Assessment of the students in the course was accomplished through direct measures of students’ achievement of outcomes, such as assignment grade analysis and a pre- and post-course clinical skills evaluation, as well as by assessment of student confidence using pre- and post-course survey instruments. Because of the small sample size of the class, comparisons among all sets of data, ordinal and continuous, were completed with the Wilcoxon signed rank test. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant. Power calculation was not conducted a priori. The sample was based on actual course enrollment (ie, 9). Of the 9 students enrolled in the course, the average grade-point average (GPA) was 3.3, with a range of 2.6 to 4.0.

Average group scores on the first 4 SOAP notes vs the last 4 were 7.5 and 8.9 out of 10, respectively (p=0.06). Average case presentation scores (an individual student measure) were 41.5 and 46.8 out of 50 (p=0.02) on the first 4 and last 4 SOAP notes, respectively. The percentage of correctly identified clinical problems on the clinical skills case completed on the first and last day of class increased from 37.5% to 52.2% (p=0.12), respectively.

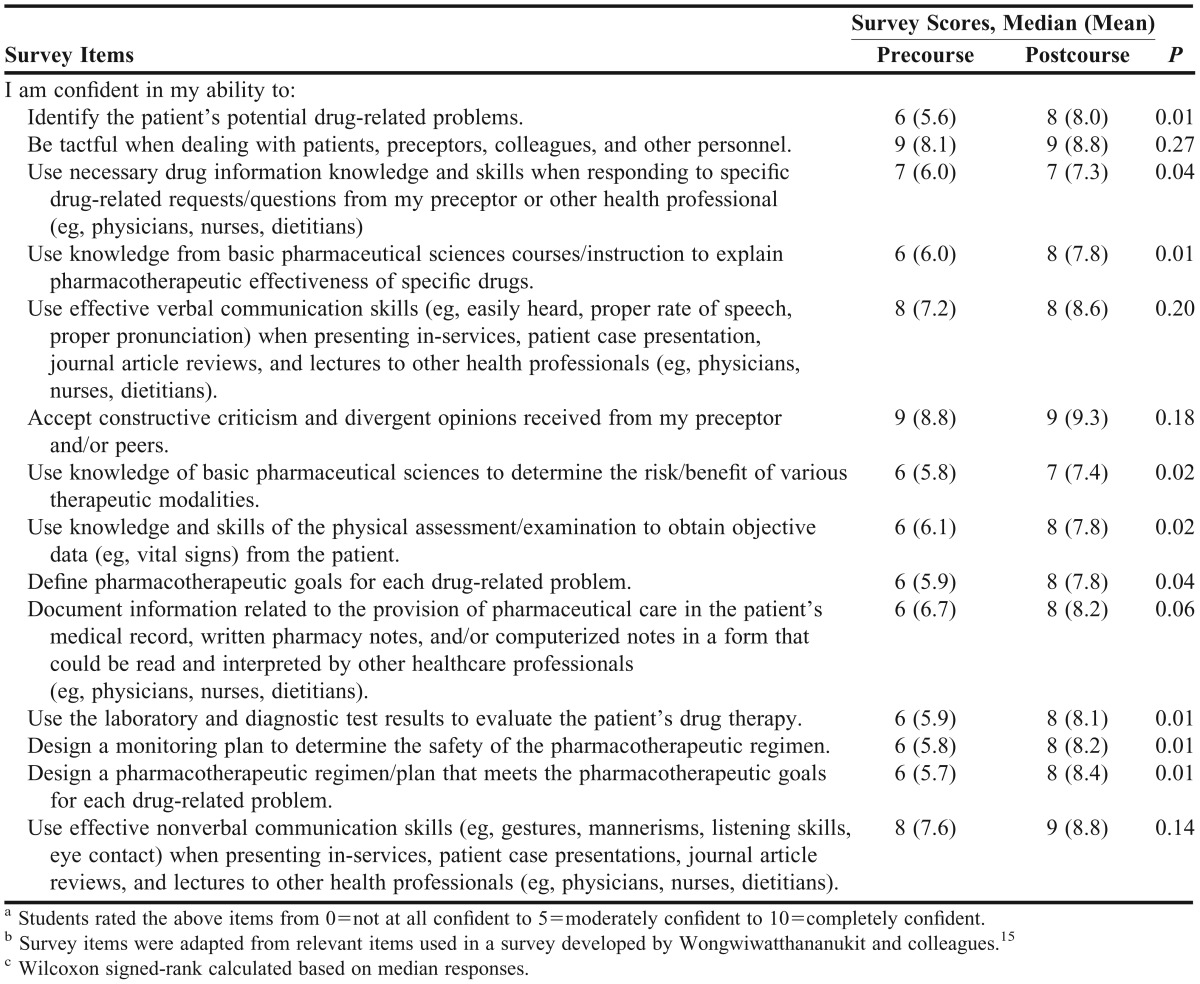

Students completed a self-confidence survey instrument on the first and final day of class. The instrument had been validated to assess self-confidence of students enrolled in an APPE.15 Applicable items were chosen and used as a short form of the instrument for the purpose of measuring self-confidence of students enrolled in this course. All 9 students enrolled in the course completed the survey instruments.

Table 4 provides the pre- and post-course median responses to the survey items. The majority of items (9 of 14) demonstrated a significant increase in students’ confidence from baseline, reflecting subjective success of the experience in achieving many of the curricular outcomes and objectives listed in Table 1. Of the items that did not increase significantly from baseline, 4 (items 2, 5, 6, and 14) reflected high confidence levels at baseline, and 1 (item 10) related to the skill of documenting patient care activities.

Table 4.

Survey Items and Responsesa,b,c

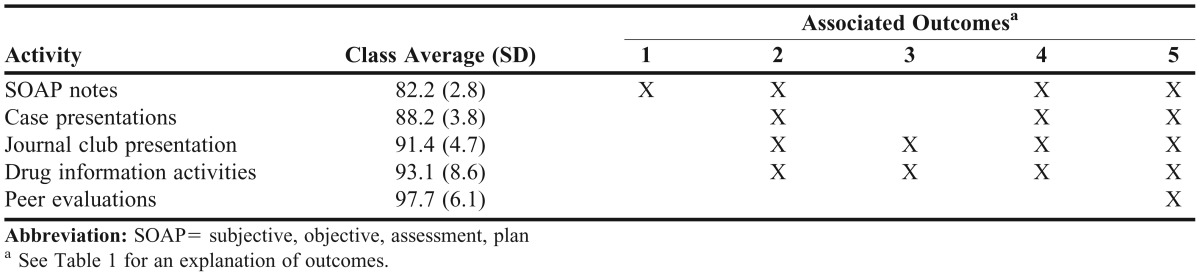

Because various types of assignments were used throughout the course, achievement of curricular outcomes was measured multiple times. All students received an 80% or better on each course assignment. Average scores for the SOAP notes and case presentations were 82.2% and 88.2%, respectively.

Successful attainment of each outcome was supported by assessment of student performance on outcome-specific assignments. Table 5 presents a map of course assignments and related curricular outcomes. Group achievement of these outcomes was measured by averaging total student scores for all outcome-associated assignments. This approach provided the following “average achievement scores” for outcomes 1-5, respectively: 82.2, 88.7, 92.2, 88.7, and 90.5. These measures seemed to indicate that students performed well across all of the curricular outcomes that were targeted by the course.

Table 5.

Methods of Assessment by Phase of Course and Associated Outcomes

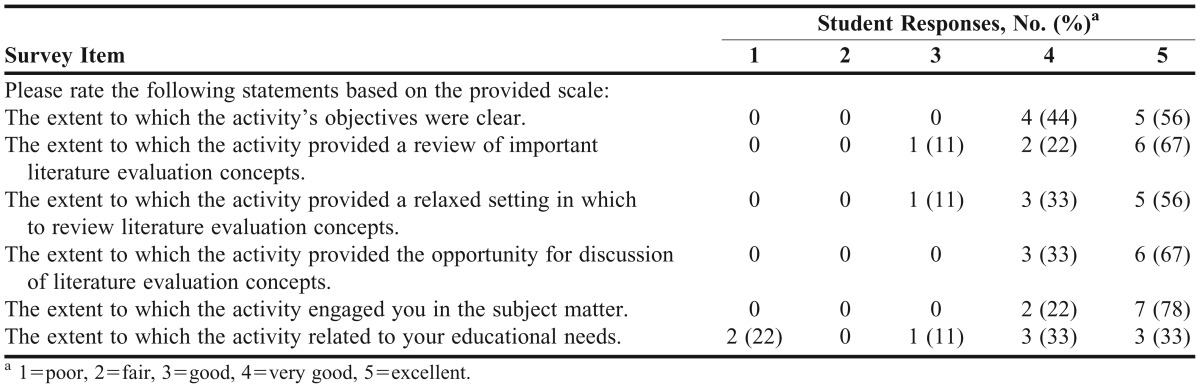

The “literature evaluation speed dating” portion of the course was evaluated by means of a survey instrument administered to the group on the last day of the course. A summary of the results is presented in Table 6. The majority of the responses were in the most favorable categories (score of 2). Two students rated the item “the extent to which the activity related to your educational needs” as poor. When asked if the activity should be repeated in future offerings of the course, 100% of the students answered in the affirmative.

Table 6.

Student Responses to Survey Items Regarding a Literature Evaluation Activity Presented in the Form of a Speed Dating Session (N = 9)

DISCUSSION

This paper describes the successful implementation of an elective course using PBL to solve patient cases, improve documentation and presentation skills, and retrieve and analyze medical literature and drug information. Upon completion of the elective course, students achieved the desired curricular outcomes, were more confident in their clinical abilities, and demonstrated an increase, although not significant, in their ability to identify clinical problems in a patient case.

Despite that many of the course assessments did not reach statistical significance, improvement was noted throughout the course. SOAP note scores did not increase significantly in this analysis, yet students commented anecdotally that the exposure and experience to this form of documentation in this course prepared them well for practicing the skill in future situations, such as in APPEs, even though these students uniformly indicated a lower level of confidence in related skills at the beginning of the course. Identification of problems on the standardized clinical case also saw a non-significant increase from baseline, however the grader did note that, descriptively, the clinical goals, treatment recommendations, and monitoring plans in the post-course cases were noticeably more detailed, thorough, and appropriate. In rating self-confidence, the 1 item related to the skill of documenting patient care activities, a significant portion of the coursework but an activity always conducted as a group, may have contributed to the lack of a significant increase in individual confidence rating from baseline and highlighted a potential area of modification for future offerings of the course. Regarding the poor rating given to the survey item regarding the extent to which the literature evaluation activity modeled after a speed dating session related to their educational needs, the investigators speculate that this finding may be a result of the relatively limited perspective of a student in his/her third year of pharmacy school compared with that of a practicing pharmacist.

At the completion of the course, the coordinators met to discuss and summarize thoughts for the college’s continuous quality improvement process. Several ideas were shared that will likely improve the course in the future. First, although students were provided resources to familiarize themselves with proper SOAP documentation and case presentation structure, they seemed uniformly hesitant and unsure during their first few experiences. The requirement of viewing an online video in which the coordinators present and critique examples may improve this aspect of the experience while saving class time. Secondly, the students expressed a desire for immediate feedback on their clinical assessments at the conclusion of each case presentation class meeting. Although the coordinators each approached their assigned case days in their own way, they have decided in the future to follow a course formula in which this feedback is provided to students in the same way by each facilitator.

This elective course demonstrated a way in which traditional classroom curricula or colleges and schools that are unable to implement an entirely PBL-focused curriculum could implement an element of PBL. Students at ULM COP have practical experiences outside of classroom lectures including SimMan (Laerdal Medical, Wappingers Falls, NY) simulated cases, progressive patient cases, and other forms of active learning throughout the curriculum in an integrated laboratory sequence (ILS) course every semester. The authors found that, even with this background, the students taking this course were only moderately confident in their ability to evaluate and assess a patient case. Also, the faculty members coordinating the elective have noted deficiencies in critical-thinking skills and confidence in making clinical recommendations during APPEs.

Several reasons may exist for this apparent lack of confidence and critical-thinking skills. Given that most of the ILS activities involve larger groups of students collectively working together, one possibility is that personal confidence and individual critical thinking could be left undeveloped. Additionally, students are not exposed to case-based learning in a repeated fashion in ILS, which denies them the repetition and sequential exposure necessary for skill development. For these reasons, the coordinators chose to use actual patient cases encountered in clinical practice, coordinate the disease states with topics that students had previously covered in classroom lecture and assign progressively more difficult cases sequentially throughout the semester. This method enabled the elective course to reinforce other classroom material while serving as a foundation for the development of additional skills.

Considering that PBL can be a time-intensive mode of instruction for faculty members, careful consideration should be made in the course-planning stages regarding an acceptable time commitment per facilitator. In this case, each faculty member had an average increase in classroom time of 10 hours over the semester. This time commitment could be reduced in the future by having more faculty members involved or adjusting the schedule and assigning faculty members specific days to be present instead of having all faculty present on activity grading days, such as the drug-information activity and journal club. The amount of time outside of class preparation was minimal because coordinators used cases from their personal area of practice and presented cases on topics about which they were knowledgeable.

Potential limitations of this study include lack of formal inter-rater reliability on individual SOAP notes and case presentations. All faculty members participating in the elective were involved in the preparation and finalizing of all grading rubrics. Additionally, to provide for greater grading consistency, faculty members met and discussed use of the rubrics, focusing specifically on areas of subjectivity to ensure greater consistency among graders. Although these measures were taken, formal inter-rater reliability was not determined using statistical analysis.

Small sample size presents another potential limitation. The elective course involved only 9 students, 1 of whom was on a modified progression track, with a mean professional GPA of 3.3 (2.6 – 4.0) compared with their fellow classmates’ average GPA of 3.46. Despite the small sample size, the authors believe that these students were representative of the P3 class and provided a good variation in academic performance. These results may reasonably be generalizable to other populations.

SUMMARY

Providing a PBL-based elective course in therapeutics supplemented with journal club and drug information, allowed for presentation of a greater variety of information. Providing this elective course in this format added variety, enhanced the overall pharmacy curriculum at ULM COP, and promoted self-directed learning, critical thinking, problem-solving, and self-confidence in those students enrolled in the course.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. http://www.acpe-accredit.org/standards/default.asp. Accessed May 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart DW, Brown SD, Clavier CW, Wyatt J. Active-learning processes used in US pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(4):Article 68. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gleason BL, Peeters MJ, Resman-Targoff, et al. An active-learning strategies primer for achieving ability-based educational outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(9):Article 186. doi: 10.5688/ajpe759186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education. Educational outcomes 2004. http://www.aacp.org/resources/education/Documents/CAPE2004.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knowles MS. Self-Directed Learning: A Guide for Learners and Teachers. Chicago: Follet Publishing; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beers GW. The effect of teaching method on objective test scores: problem-based learning versus lecture. J Nurs Educ. 2005;44(7):305–309. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20050701-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hogan S, Lundquist L. The impact of problem-based learning on students’ perception of preparedness for advanced pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(6):Article 127. doi: 10.5688/aj700482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bookstaver PB, Rudisill CN, Bickley AR, et al. An evidence-based medicine elective course to improve student performance in advanced pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(1):Article 9. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.University of Louisiana at Monroe. College of Pharmacy. ULM College of Pharmacy competency statements/educational outcomes. http://ulm.edu/pharmacy/mpaedoutcomes.html. Accessed May 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haahr M. Random.org: True random number service. http://www.random.org. Published 1998. Updated 2012. Accessed July 28, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Brien CE, Franks AM, Stowe CD. Multiple Rubric-based assessments of student case presentations. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(3):Article 5. doi: 10.5688/aj720358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pharmacist’s Letter. Preceptor Toolbox, Evaluation Tools. Journal club evaluation criteria. http://pharmacistsletter.therapeuticresearch.com/ptrn/downloaditem.aspx?cs=FACULTY&s=PL&id=467. Accessed May 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloom BS, editor. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. The Classification of Educational Goals. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. New York, NY: McKay; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fink LD. Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wongwiwatthananukit S, Newton GD, Popovich NG. Development and validation of an instrument to assess the self-confidence of students enrolled in the advanced pharmacy practical experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2002;66(1):5–19. [Google Scholar]