Abstract

To identify characteristics and quality indicators of best practices for leadership and advocacy development in pharmacy education, a national task force on leadership development in pharmacy invited colleges and schools to complete a phone survey to characterize the courses, processes, and noteworthy practices for leadership and advocacy development at their institution. The literature was consulted to corroborate survey findings and identify additional best practices. Recommendations were derived from the survey results and literature review, as well as from the experience and expertise of task force members. Fifty-four institutions provided information about lecture-based and experiential curricular and noncurricular components of leadership and advocacy development. Successful programs have a supportive institutional culture, faculty and alumni role models, administrative and/or financial support, and a cocurricular thread of activities. Leadership and advocacy development for student pharmacists is increasingly important. The recommendations and suggestions provided can facilitate leadership and advocacy development at other colleges and schools of pharmacy.

Keywords: student leadership, advocacy, faculty member, pharmacy student, citizen leader

INTRODUCTION

In 2004, a survey of pharmacists predicted that a significant gap in pharmacy leadership would occur between 2009 and 2014 in health-system pharmacy. Of particular concern, less than half (32%) of current pharmacist practitioners were interested in pursuing leadership positions.1 To address the potential gap in pharmacy leadership, a number of organizations have called for leadership development. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) has advocated for inclusion of formalized leadership training in colleges and schools of pharmacy, as well as pharmacy residency programs and professional organizations. Not only should leadership training prepare future pharmacists for conventional leadership positions in the medication-use system, it should also groom them to assume leadership roles in every day practice. In order to advance the profession and enhance patient care, ASHP calls every pharmacist to function as a “leader in the safe and effective use of medications” in their practice.2 As such, ASHP asserts that leadership is a “professional obligation” for all pharmacists. The report of the 2008-2009 Argus Commission also focused on the importance of creating a sustainable program of leadership development for pharmacy.3 Like ASHP, the Argus Commission acknowledged that all pharmacists must recognize leadership opportunities and obligations in their daily practice. The Argus Commission recommended that colleges and schools of pharmacy stimulate leadership development by threading leadership education throughout the curriculum and co-curricular activities. Lastly, the need for leadership in pharmacy is further underscored by accreditation standards that direct curricula to cultivate the development of future pharmacists as “leaders and agents of change.”4

As emphasized by the AACP Curricular Change Summit, advocacy is a component of leadership and an essential competency for the future of pharmacy.4,5 The concept of advocacy is broad, and, as such, it can be applied in many different contexts. While references to advocacy in the health professions literature have included a spectrum of terms such as legislative/political, clinical/patient-centered, administrative, educational, social, and economic advocacy, this paper primarily focuses on the domains of legislative and patient advocacy.6-8

Legislative advocacy is fundamental to the future of pharmacy. For example, one of the primary responsibilities of current and future pharmacists is to promote public health through provision of population-based care, health and wellness initiatives, and disease prevention strategies.4,5,9 For pharmacy to truly play an integral role in improving the public health of the United States, the profession must advocate for change and be instrumental in guiding and shaping public health policy. In addition, legislative advocacy is also critical for the expansion of pharmacist-provided services and creation of new practice opportunities for the influx of highly trained pharmacy graduates entering the workplace.10,11 Other health professions such as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and optometrists have been extremely successful in advancing their professional privileges through concerted advocacy efforts.5,10 For example, through unified advocacy initiatives, nurse practitioners now provide independent services with diagnostic, treatment, referral, and prescribing privileges in 16 states and the District of Columbia and practice in collaboration with a physician in the remaining 34 states.12 The profession of pharmacy needs to take note of these effective examples, and view them as a call to act. With health care at the forefront of every political agenda, pharmacists now have a golden opportunity to advocate for their role as health care providers who maximize the safe and effective use of medications, and improve overall quality of care and health outcomes.

Advocacy discussions often center solely on the legislative perspective; however, as health care providers, pharmacists must focus on the patients they serve. An awareness of the importance of patient advocacy and development of skills to serve as a patient advocate should be a part of student programs. Pharmacists are accessible and positioned to advocate for the patients they serve across the continuum of care. They have opportunities to interact with patients in a variety of settings to identify needs, specifically medication-related needs, and assist the patient in addressing the concern.13 The American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Council of Faculties established the Task Force on Preparation of Pharmacy Faculty and Students to be Citizen Leaders and Pharmacy Advocates in 2009 and charged the members to tabulate and characterize the courses or processes used by various institutions to develop leaders and health care advocates, and to describe characteristics and quality indicators to help identify best practices for leadership and advocacy development in pharmacy curricula. This report describes the process undertaken by the task force, including a survey of pharmacy colleges and schools and review of the literature, in order to develop recommendations for advancing leadership and advocacy development in pharmacy education.

In addressing the charges, the Task Force envisioned a goal beyond leadership and advocacy development, instead emphasizing pharmacists as citizen leaders and advocates. The key word is citizen. Citizens are members of a community, nation, or an area of commonality; they are civilians who profess allegiance.14 Pharmacists are actually naturalized citizens within the profession of pharmacy. Naturalization involves learning about founding documents and civics processes, successfully completing an examination, and taking an oath, just as student pharmacists complete pharmacy education and affirm the Oath of a Pharmacist prior to a licensure examination.15 Naturalized US citizens often exhibit a profound appreciation for the freedoms and responsibilities that are part of earned citizenship. Professional citizenship provides a relevant context for using their skills, which includes deployment to advance health care for individuals and populations and to influence local and national government.16 Citizens of the profession of pharmacy are free to pursue their interests, but they have responsibilities as citizens. As leadership and advocacy educators we must assist our students, faculty, and graduates in better appreciating their earned citizenship, which prepares them to be citizens within the profession, among other health care professionals, and for their country.

DETERMINING THE STATUS OF LEADERSHIP AND ADVOCACY EDUCATION IN PHARMACY

Survey Development and Administration

The Task Force on Preparation of Pharmacy Faculty and Students to be Citizen Leaders and Pharmacy Advocates set out with a charge to characterize the courses and processes used by various institutions to develop leaders and health care advocates and to create mechanisms to characterize and select best practices for leadership and advocacy development in pharmacy education. To guide the task force’s work through the survey, literature review, and recommendations, definitions of leadership and advocacy were identified. Leadership was defined as “the process of influencing an organized group toward accomplishing their goals.”17 Student pharmacists have curricular and co-curricular opportunities to develop and apply leadership. This pertains to positional leadership (eg, elected office, committee chair) and to non-positional leadership (eg, volunteer activities, teamwork, projects). Leadership skills may be called upon when students work with professional associations, student organizations, employers, governmental agencies, and community-based entities. For this research, advocacy was defined as active support of an idea or cause.18 Inherent to advocacy is supporting, recommending, or urging a change in a policy, cause, idea, or outcome. There is a parallel between advocacy and patient-centered care in that pharmacists assume responsibility for patient outcomes. Beginning in August 2009, the task force spent 2 months creating a comprehensive 63-question, 25-page survey instrument to collect the curricular activities in classroom and experiential/service learning settings, along with noncurricular components of development, such as admissions considerations and student organization activities. Questions were developed by 4 members of the task force and then reviewed for clarity and comprehensiveness by all 10 members of the task force. The task force decided that the breadth and degree of information they desired to capture would require personal phone interviews. The interview was pilot tested at task force members’ colleges and schools and then revisions were made. The final interview included questions on the structure of the college or school (6 items), institutional commitment to leadership and advocacy (7 items), admissions (4 items), classroom instruction (9 items), experiential learning (11 items), academic service learning (9 items), co-curricular activities (2 items), student organizations (5 items), faculty development in leadership (4 items), faculty development in advocacy, (3 items) and noteworthy and successful leadership and advocacy efforts (3 items). Participants were asked the following questions: At your college/university, what would you consider your most noteworthy efforts related to leadership development? At your college/university, what would you consider your most noteworthy efforts related to advocacy? What are the elements of a successful leadership or advocacy development effort? (A copy of the survey instrument is available from the corresponding author.)

Accredited colleges and schools of pharmacy in the United States and Canada that had graduated at least 1 class of PharmD students were identified to participate in the survey. Task force members divided the list of eligible colleges and schools based on their proximity or relationship with the faculty member to be interviewed. The deans of colleges and schools were approached first to participate and/or to forward the task force’s information to the most appropriate person at the institution. If the dean determined that additional faculty or staff members should provide input, he or she was encouraged to collect the information prior to the phone interview or the task force member made additional calls to the recommended faculty or staff members. In order to collect all information in a uniform fashion across the task force members’ locales, Qualtrics (Qualtrics Laboratories, Inc., Provo, Utah) was used as the platform to document all information collected during phone interviews. To supplement its work in gathering information from the colleges and schools, the task force also examined the leadership and advocacy development literature.

Overview of Survey Findings

The definitions used within the survey instrument to ensure consistent collection of information resulted in the task force finding a wealth of information and a large variety of leadership and advocacy promotion across colleges and schools of pharmacy. At the time of survey development, 105 colleges and schools were identified as eligible for participation. The survey instrument collected information from 54 institutions. Of those, 59% described their college or school as public. The majority (63%) of respondents were housed on a single campus. Of the respondents with multiple campuses (17%), 53% had 1 additional site and 32% had 2 locations. One-fifth of respondents reported satellite campuses, with 58% having 1 satellite campus, and 25% having 2 campuses. The typical student population at participating institutions was 300 to 400 individuals.

Respondents stated that leadership and advocacy appeared within their strategic plan 72% and 53% of the time, respectively. As part of the admissions process, 94% of respondents assessed leadership as a consideration for admission. Thirty-five percent reported confirming that leadership activity was present within the admission packet, while 17% of institutions reported considering advocacy as a criterion for acceptance. A weighted rubric was used by 29% and 40% of respondents to delineate degrees of leadership and advocacy among applicants, respectively.

When asked about courses on leadership or advocacy, 79% of respondents answered affirmatively to offering entire or parts of courses on at least one of these topics. Of the colleges and schools that offered classroom coursework, 15 provided required courses and 11 provided electives. The majority of courses enrolled an average of 158 students annually, with the third year (ie, sixth year would indicate the graduation year) being one in which students most commonly registered. Six respondents indicated an interprofessional component to classroom courses.

Experiential education offered at the colleges and schools that responded held opportunities for leadership and advocacy. Half of the introductory pharmacy practice experiences (IPPEs) and 75% of advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs) had leadership and/or advocacy objectives. However, the time devoted during these experiences to leadership or advocacy activities varied, as did the number of students eligible to enroll. Academic service-learning was defined as combining community service with academic instruction with a focus on critical, reflective thinking and civic responsibility. Academic service-learning was offered in 47% of responding institutions, with 18 requiring it as either a separate course or part of an IPPE, and 5 offering it as an elective. Advocacy objectives were encompassed in 15 of the academic service-learning experiences. Five included leadership and 2 included both leadership and advocacy outcomes as part of the experience.

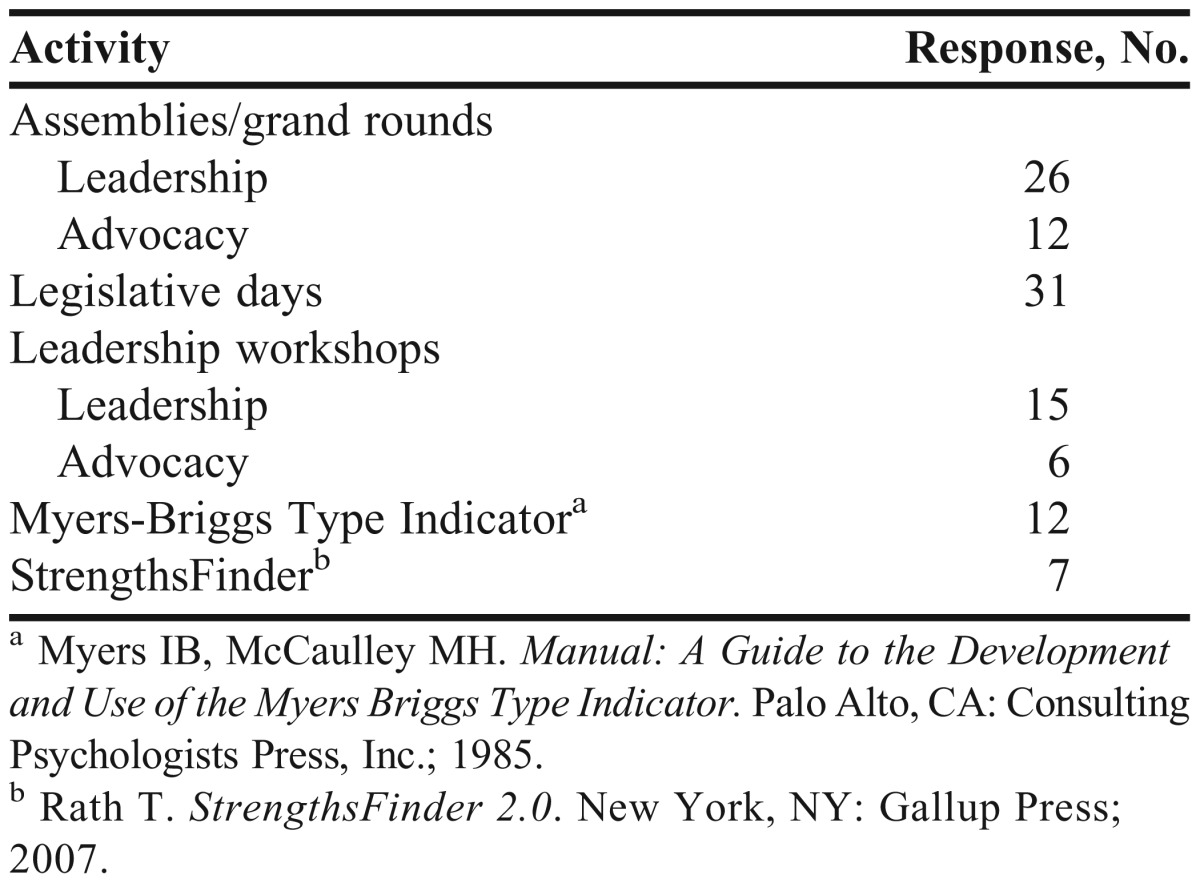

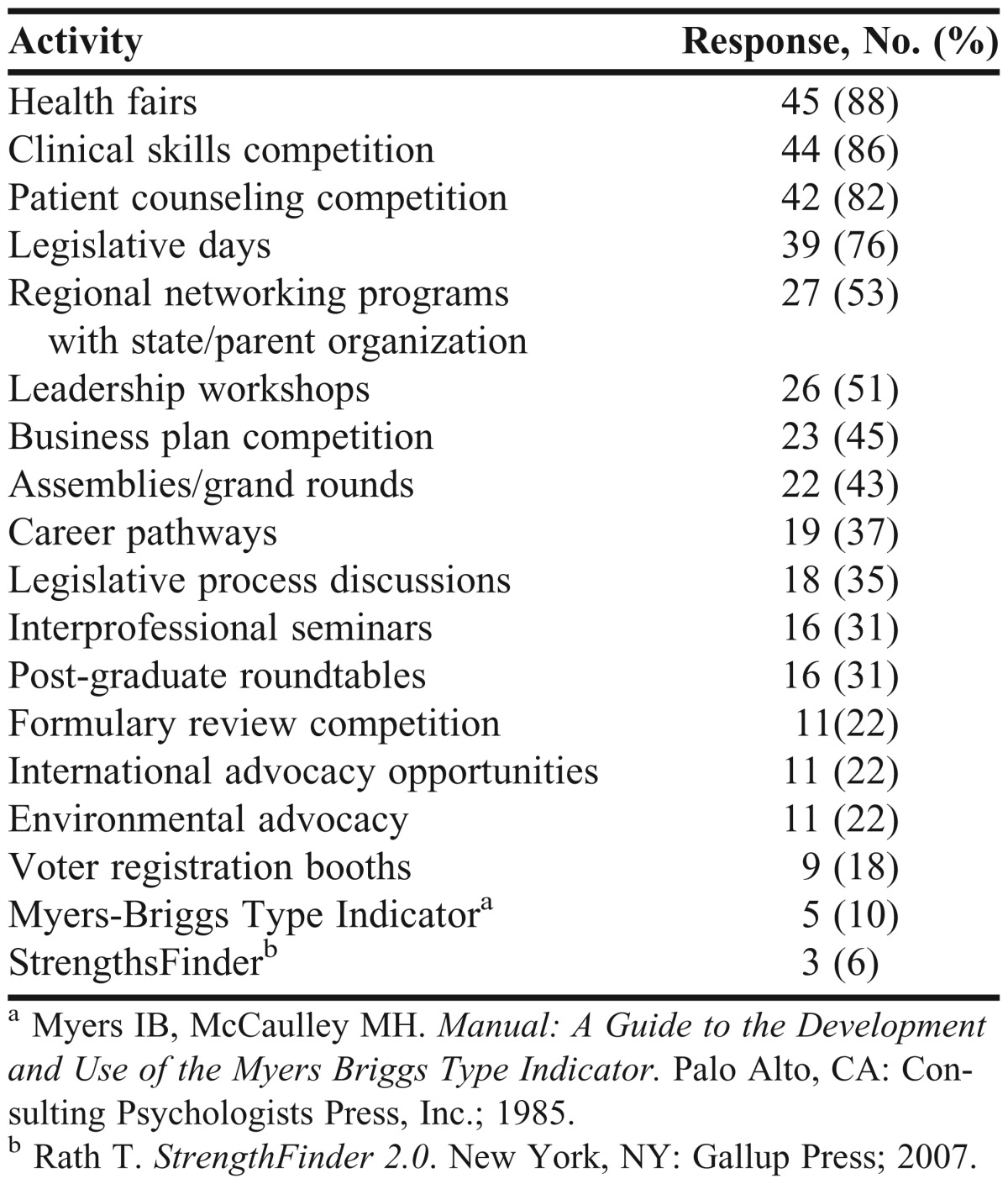

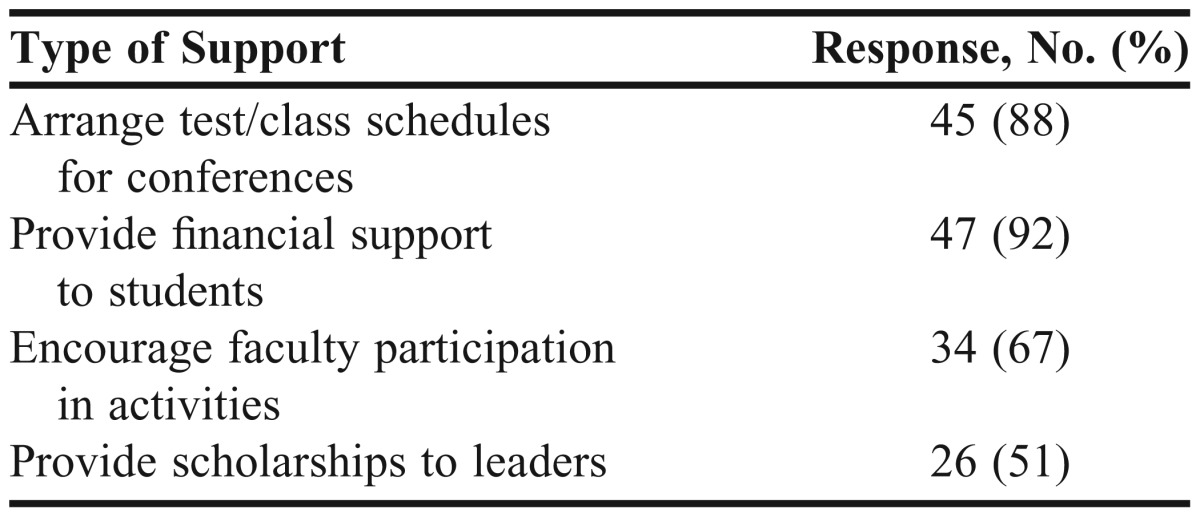

Extracurricular activities related to leadership and advocacy were hosted by institutions and are depicted in Table 1. Leadership was encouraged broadly through organizational officer positions (ie, mean of 64 positions per institution) and/or college or school standing committees. The breadth of student organization programming including leadership and advocacy activities is illustrated in Table 2. Avenues used by institutions to support student pharmacist leadership and advocacy endeavors are described in Table 3.

Table 1.

Co-curricular Activities Related to Leadership and Advocacy Arranged by Institutions

Table 2.

Student Organization Programming in US Colleges and Schools of Pharmacy Including Leadership and Advocacy Activities

Table 3.

Institutional Support for Student Advocacy or Leadership Activities

Noteworthy Leadership Development Practices in Colleges and Schools

Forty-six participants cited noteworthy leadership practices. Six major themes, described below, emerged from the responses.

Creation of a culture of expectation for involvement as leaders. Educators noted that expectations for pharmacy students to become leaders began upon entry to the program and were facilitated by classroom and experiential curriculum and opportunities to join professional student organizations. Supporting and encouraging students to accept leadership roles, promoting leadership through activities such as weekly assembly programs, intentionally thinking about leadership development, and including leadership as part of the mission were mentioned as ways in which faculty members fostered a culture of involvement. A few respondents indicated that leadership was a component of students’ expected professionalism standards.

Establishment of opportunities for leadership in student organizations. Several participants talked about the positive role student organizations have in developing students’ leadership skills. In particular, the availability of an extensive offering of student pharmacist organizations was viewed positively and as an opportunity to engage a variety of students’ interests. Respondents also supported and encouraged student involvement at the university, state, and national levels.

Provision of role models and mentors for leadership. Respondents discussed administration and faculty members leading by example in various leadership roles, ranging from student organization advisors to holding local, state, or national leadership offices. A few colleges and schools had formal mentoring programs that emphasized leadership skills. Alumni leaders were also mentioned as serving as role models for students.

Establishment of ways for valuing and recognizing efforts. Many participants noted that internal and external recognition validated efforts and led to an increase in involvement. Internally, administration and faculty members demonstrated value in the form of respect and encouragement. Also, having support in the form of monetary resources to assist with travel to meetings helped. One participant said an awards ceremony for faculty and students was held as a formal way to recognize leadership achievements. Participants also discussed recognition with awards from external groups, such as national organizations as a means to demonstrate value of efforts.

Promotion of leadership development programs for students and faculty members. Many colleges and schools provided opportunities for students and faculty members to participate in leadership development programs and activities. The types of opportunities varied from school to school, but generally, respondents encouraged faculty members and students to participate in existing programs at the university, state, and/or national levels. Several colleges and schools sponsored an annual retreat focused on development of student leaders. One respondent noted that his school received funding to support 1-year of leadership development activities including a student leadership retreat, speaker series, and dinner series for students.

Integration of leadership building skills throughout the curriculum. The scope and extent of formal leadership training provided by the respondents’ colleges and schools varied widely from elective courses to an 18-credit emphasis area in leadership for PharmD students to a doctoral degree program in public health and leadership. Respondents reported striving to integrate leadership skills throughout the curriculum and create connectivity between classes.

Although not prominent themes, other noteworthy leadership practices reported by participants included fostering relationships with state and national organizations and other colleges and schools, and the inclusion of leadership criteria in the admissions process.

Noteworthy Advocacy Development Practices in Colleges and Schools

Thirty-three responding institutions reported noteworthy advocacy practices, and 3 main themes, described below, were identified from the responses.

Active participation in Legislative Day. Participants viewed having a strong faculty and student presence at their state’s Legislative Day as a noteworthy advocacy practice. This event served as a way to exemplify advocacy for student participants by highlighting the collective efforts of many groups, including professional organizations, health care providers, and local and state government representatives. A few colleges and schools worked with a statewide group, which included various pharmacy stakeholders, to address legislative issues.

Community outreach. A wide variety of community outreach activities that promoted pharmacy were reported by respondents. Activities included health fairs at the state capitol and US Capitol to demonstrate the value of pharmacist services, community health fairs to promote treatment and prevention of conditions such as diabetes, and volunteering at indigent clinics. Involvement in public health initiatives, such as Haiti earthquake relief and safe disposal of medications, were also discussed.

Integration of advocacy throughout the curriculum. Similar to noteworthy leadership practices, several participants discussed efforts by their college or school to consciously connect advocacy topics with coursework. Some colleges and schools offered experiential opportunities, which were either required or elective. One school highlighted service learning as a mechanism for increasing advocacy.

Other noteworthy advocacy efforts included letter-writing campaigns, promoting patient advocacy, and being involved with state associations. Several respondents explicitly said they did not have any noteworthy advocacy best practices to mention or that this was an area that was important but in progress.

Elements of a Successful Leadership or Advocacy Development Effort

Respondents (n=26) reported that 3 key elements led to a successful leadership or advocacy initiative: a supportive institutional culture, defined goals and outcomes, and recognition and rewards. A supportive culture included buy-in and mentoring from administration and faculty members and also support in the form of monetary resources and encouragement. Faculty and/or community champions were also noted as being key to fostering this culture. The dean was specifically mentioned as a primary individual for supporting initiatives and serving as a role model.

Defined goals and expected outcomes were also important. Respondents indicated that formal feedback and assessment helped determine whether goals were being achieved and the overall impact of programs. Recognition by administration, faculty members, and colleagues, and/or receiving awards were also key to determining a successful leadership or advocacy development effort. Other elements included faculty and student toolkits to guide program development, planning for sustainability of programs, and considering how individual strengths could add value to a program.

Leadership and Advocacy Development Reported in the Literature

Leadership development is not simple. Dugan suggests that the rapid proliferation of programs has “positioned those without significant training in leadership studies or curriculum development as leadership educators.19 Indeed, as pharmacy enhances leadership development programming, faculty members will be needed for instruction and coaching. These faculty members will not only need to be role models and leaders themselves, but also versed in effective methods for leadership development and willing to guide the curricular and instructional design necessary to design successful programming.

This rapid escalation of leadership programming has propagated the false assumption that leadership development is intuitive. Instead leadership capacity is built incrementally through exposure to meaningful interventions over time.19 The concept of a deliberate and intentional sequence of leadership learning opportunities has significant implications for leadership development in pharmacy.

In addition, development must include experience. Posner has emphasized that classroom work is not enough; leadership development must involve doing.20 In their paper on designing leadership development, Guthrie and Thompson state that students “must understand leadership theory, develop leadership skills through practical application, and reflect upon their knowledge and experiences to learn and grow.21 Clearly, leadership development programming will need to involve hands-on opportunities to lead.

All leadership experiences may not be positive. However, significant development can occur as the result of struggles and failures. Bennis has discussed the importance of development, emphasizing crucibles, defined as intense, often traumatic, unplanned experiences that transform and develop distinctive leadership abilities.22 Given their science backgrounds, pharmacist advocates may relate to this example of crucibles, which are vessels that do not melt easily and withstand chemical reactions or high temperatures similar to our political discourse at times. Parks, documenting the leadership instructional approach of Harvard Professor Ron Heifetz, emphasizes the need for analysis of leadership experiences and reflection, in order to foster growth in abilities.23 To support reflective analysis, small groups have been used, as well as journaling. The importance of mentoring has also been well articulated as a support to leadership development. As pharmacy moves forward with leadership development, consideration will need to be given to opportunities for analysis and reflection, creation of supportive communities, and the mentoring needs of students.

Blumenthal and colleagues argue that formal leadership development in medicine should be an explicit goal of residency training.24 Their review of the literature identified common elements of effective leadership development programs including: (1) reinforcing/building a supportive culture, (2) ensuring high-level sponsorship and involvement (including mentorship), (3) tailoring the goals and approach of the program to the context, (4) targeting programs toward specific audiences, (5) integrating all features of the program, (6) using a variety of learning methods, (7) offering extended learning periods with sustained support, (8) encouraging ownership of self-development, and (9) committing to continuous improvement. Attention must be paid to the effectiveness and the sustainability of leadership development programming in pharmacy education.

Leadership and advocacy are intertwined. Advocacy can be seen as a direct and impactful experiential component of leadership. In advocating for an issue, a law, or quality improvement project, students must deploy all of their leadership skills in researching issues, communicating, and working with others to influence decisions. Richard P. Penna concluded his chapter in Leadership and Advocacy for Pharmacy with this:

Advocacy is a critical and necessary part of the pharmacy leader’s role. Understanding the comprehensive nature of advocacy is the leader’s first challenge. Advocacy involves understanding relevant policy issues; expressing them in clear language; understanding the processes of securing public, legislative, and regulatory support for policies; and engaging in the arduous process of securing adoption of pharmacy’s positions…. Advocacy is a leadership function. The person who does not advocate is not a leader.25

Developing competency-based medical advocacy training and practice opportunities has been identified as necessary and a framework to design this training may include a definition based on actual advocate experience and an identified spectrum of advocacy activities.7,26 Like leadership development, advocacy development is also not simple. Earnest and colleagues make the case that in order for advocacy training to succeed, accrediting bodies must endorse it and colleges and schools must develop stronger community relationships.7

Building advocacy skills often involves building leadership skills. Huckabee and Wheeler advocate for development opportunities that “allow [students] to be a part of something bigger than themselves,” to face “controversial and difficult health care issues,” to envision “new methods of achieving health goals,” and to “react and respond to severe global health issues.”27 Achieving these advocacy goals inevitably requires students to use leadership skills such as visioning, enabling others to act, and challenging the process.

Methods for addressing advocacy and leadership have been described. Mansfield and Meyer pair leadership and advocacy learning explicitly, having students complete 2 major group projects by assessing an identified community need and completing a leadership change project.28

A commentary on leadership in medical school describes the rationale for the emphasis on leadership as the need to “resolve social and political obstacles” to health care. The authors argue that the deficit in leadership skills is attributable to failures in medical education to emphasize skill development.29

In development programs, the pairing of leadership and advocacy can be quite deliberate and strong. Guided by 5 physician and 1 nurse researcher faculty members, LEADS is a track in the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine which focuses on the underserved and disadvantaged. Participants are provided “the vision and skills to be leaders and advocates for patients” and their needs.30 Crites and colleagues highlight a 5-year medical undergraduate leadership program. The program includes a course on health advocacy in which students must describe advocacy roles within and without organizations, demonstrate interpersonal persuasion practices, identify barriers to interpersonal and systemic change, describe the politics of change, and demonstrate approaches to communicate change. There is an additional practicum that involves a field experience in health advocacy and leadership in which participants identify a policy or group in need of advocacy reform and develop, implement, and evaluate an advocacy plan.31

The advocacy activities, programs, and courses championed by cited authors are linked to the micro and macro levels of public health.32 Students must learn basic competencies in communication, needs assessment, and health policy in order to help patients individually or collectively. Social consciousness that is nurtured through volunteerism and service learning helps health professions students relate to patients’ circumstances and to actively work to achieve national health goals.

DISCUSSION

The comprehensive survey instrument allowed for the compilation of a broad range of data and the phone interviews provided in-depth, quality information on survey questions. This data would have been strengthened with more participation, which may have been limited by the survey administration time and the occasional need for input from multiple individuals at one institution. Steps were taken to ensure a consistent data collection process from a design, administration, and documentation perspective; however, there may have been differences in the survey respondents’ determinations of activity designations or categories. The following recommendations and suggestions by the Task Force on Preparation of Pharmacy Faculty and Students to be Citizen Leaders and Pharmacy Advocates are based upon survey responses, several of which confirm those in the 2008-2009 Argus Commission report, a comprehensive literature review, and the experience and expertise of task force members.3

Recommendations

(1) AACP should support deans, especially those new to their positions, and develop them for their pivotal role as catalysts for the leadership and advocacy culture within their institutions.

(2) AACP should support inclusion of leadership (eg, practice change initiatives) and advocacy impact factors (eg, patients served, governmental agency health promotion partnerships) within institutional assessment criteria to document success.

(3) AACP should support explicit ACPE accreditation standards (eg, must statements vs should statements) in support of the development of leaders in relevant curricular, student, and faculty/staff standards.

(4) AACP should support inclusion of “advocates” or “advocacy” as standard terminology within the ACPE accreditation standards.

(5) AACP should encourage ACPE to develop guidelines around advocacy development in relevant curricular, student, and faculty/staff standards.

(6) AACP should expand its efforts to support faculty members in their personal leadership and advocacy development.

(7) AACP should support faculty members in acquiring skills and tools to facilitate student leadership development and advocacy development.

(8) AACP, via its Leadership Development Special Interest Group, should support faculty scholarship in advancing leadership and advocacy development.

Suggestions

Curricula

(1) Members of the academy are encouraged to read Building a Sustainable System of Leadership Development for Pharmacy: the Report of the 2008-2009 Argus Commission, which provides background and a framework in support of leadership development programs.

(2) Colleges and schools of pharmacy should include leadership and advocacy development in the curricula.

(3) Colleges and schools of pharmacy should support curricula which reflect the relationship between leadership and advocacy development.

(4) Colleges and schools of pharmacy are encouraged to plan for both leadership and advocacy development as a thread through the curriculum, co-curriculum, and extracurricular activities.

(5) In order to develop effective and sustainable programming, colleges and schools should draw upon the leadership and advocacy development literature during curricular and instructional design.

Students

(1) Colleges and schools of pharmacy should include experience with leadership and advocacy as admissions criteria for prospective students.

(2) Colleges and schools of pharmacy should recognize, encourage and support the vital role of student organizations in leadership and advocacy development.

(3) Colleges and schools of pharmacy and student organizations should work together to provide leadership and advocacy development opportunities.

Culture

(1) Colleges and schools of pharmacy should consider leadership and advocacy development in strategic planning and define explicit goals and outcomes for leadership and advocacy opportunities in order to build an institutional culture based upon pride and purpose.

(2) Colleges and schools of pharmacy should work toward cultures that recognize both positional and non-positional leadership for both students and faculty members.

(3) Colleges and schools of pharmacy are encouraged to recognize, encourage, and support faculty members who are highly engaged and effective in the leadership and advocacy culture within their institution or in partnership with others.

(4) Colleges and schools of pharmacy are encouraged to include postgraduate leadership and advocacy development (eg, faculty members, alumni, pharmacy residents, graduate students, and practitioners) as a means to ensure their “citizens” are effective and engaged in the issues within their domains.

(5) To conserve human and financial resources and to promote interprofessionalism, colleges and schools of pharmacy are encouraged to support partnerships and collaboration in leadership and advocacy development. These partnerships may be developed between colleges and schools or among health professions.

SUMMARY

Developing leadership and advocacy skills has never been more important for pharmacists than it is today. With a changing health care environment, future pharmacists must be prepared as citizen leaders to execute the vision that pharmacy has articulated with an appreciation and sense of responsibility for the opportunities ahead. In preparation, a number of required elements have been identified for a sustainable system of leadership and advocacy development in pharmacy education and practice. Essential components of successful programs include a supportive institutional culture, strong administrative and financial support, and a deliberate thread of curricular and co-curricular courses and activities throughout the curriculum. Well-designed student pharmacist and postgraduate education and training opportunities can play an important role in the leadership development of professionals. Student organizations are also important to success, as is a culture that recognizes positional and non-positional leadership. Partnerships with alumni and faculty role models are needed to develop these important leadership and advocacy skills. Pharmacy educators must take action to prepare students, faculty members, and graduates to be citizen leaders within the profession, among other health care professionals, and for their country.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledges Dr. Gary Matzke for his vision and leadership in the creation of the Task Force, Dr. Anna Legreid Dopp, Dr. Kam Nola, and Dr. Rabia Tahir for their contributions as Task Force members, and Dr. Emily Dotter Pherson for her support of Task Force work.

REFERENCES

- 1.White SJ. Will there be a pharmacy leadership crisis? An ASHP foundation scholar-in-residence report. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62(8):845–855. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/62.8.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP statement on leadership as a professional obligation. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2011;68(23):2293–2295. doi: 10.2146/sp110019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerr RA, Beck DE, Doss J, et al. Building a sustainable system of leadership development for pharmacy: report of the 2008 – 09 Argus Commission. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8):Article S5. doi: 10.5688/aj7308s05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/FinalS2007Guidelines2.0.pdf . Accessed September 4, 2012.

- 5.Jungnickel PW, Kelley KW, Hammer DP, Haines ST, Marlowe KF. Addressing competencies for the future in the professional curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8):Article 156. doi: 10.5688/aj7308156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croft D, Jay SJ, Meslin EM, Gaffney MM, Odell JD. Is it time for advocacy training in medical education? Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1165–1170. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826232bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Earnest MA, Wong SL, Federico SG. Physician advocacy: what is it and how do we do it? Acad Med. 2010;85(1):63–67. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c40d40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyle CJ. Advocacy: the essential competence. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2009;49(3):364–366. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.08135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners. Future vision of pharmacy practice. November 10, 2004. http://www.aacp.org/resources/historicaldocuments/Documents/JCPPFutureVisionofPharmacyPracticeFINAL.pdf . Accessed September 19, 2012.

- 10.Fincham JE, Ahmed A. Dramatic need for cooperation and advocacy within the academy and beyond. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(1):Article 1. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beardsley RS. Enhancing student advocacy by broadening perspective. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(1):Article 14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Governors Association Center for Best Practices. The role of nurse practitioners in meeting increasing demand for primary care. December 2012. http://www.nga.org/files/live/sites/NGA/files/pdf/1212NursePractitionersPaper.pdf . Accessed June 30, 2013.

- 13.American Society of Consultant Pharmacists. ASCP policy statement on the role of the pharmacist in patient advocacy. http://www.ascp.com/resources/policy/upload/Sta02%20-%20Patient%20Advocacy.pdf . Accessed September 19, 2012.

- 14.Merriam Webster Dictionary. Definition of citizen. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/citizen . Accessed September 18, 2012.

- 15.American Pharmacists Association. Oath of a pharmacist. American Pharmaceutical Association Academy of Students of Pharmacy/ American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Council of Deans (APhA-ASP/AACP-COD) Task Force on Professionalism. June 26, 1994. Revised 2007. https://www.pharmacist.com/oath-pharmacist. Accessed September 22, 2012.

- 16.Boyle CJ, Beardsley RS, Hayes M. Effective leadership and advocacy: amplifying professional citizenship. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(3):Article 63. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rauch CF, Behling O. Functionalism: basis for alternate approach to the study of leadership. In: Hunt J, Hosking D, Schriesheim C, Steward R, eds. Leaders and Managers. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press; 1984:45–62

- 18.Merriam Webster Dictionary. Definition of advocacy. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/advocacy . Accessed September 18, 2012.

- 19.Dugan JP. Pervasive myths in leadership development: unpacking constraints on leadership learning. J Leadersh Stud. 2011;5(2):79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Posner BZ. From inside out: beyond teaching about leadership. J Leadersh Educ. 2009;8(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guthrie KL, Thompson SA. Creating meaningful environments for leadership education. J Leadersh Educ. 2010;9(2):50–57. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennis WG, Thomas RJ. Crucibles of leadership. Harv Bus Rev. September. 2002:39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parks SD. Leadership Can Be Taught. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blumenthal DM, Bernard K, Bohnen J, Bohmer R. Addressing the leadership gap in medicine: residents’ need for systematic leadership development training. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):513–522. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31824a0c47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penna RP. Application of advocacy and leadership. In: Boyle C, Beardsley R, Holdford D, eds. Leadership and Advocacy for Pharmacy. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2007:155–166

- 26.Dworkis DA, Wilbur MB. Letter to the editor: a framework for designing training for medical advocacy. Acad Med. 2010;85(10):1549–1550. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181f04750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huckabee MJ, Wheeler DW. Defining leadership training for physician assistant education. J Physician Assist Educ. 2008;19(1):24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mansfield R, Meyer CL. Making a difference with combined community assessment and change projects. J Nurs Educ. 2007;46(3):132–134. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20070301-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeVaul RA, Knight JA, Edwards KA. Leadership training in medical school. Acad Med. 1993;68(9):672. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199309000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The LEADS Program. University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine. Denver, Colorado. www.LEADS.ucdenver.edu. http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/medicalschool/education/degree_programs/mdprogram/longitudinal/tracks/leads/Pages/Leads$.aspx. Accessed November 20, 2013.

- 31.Crites GE, Ebert JR, Schuster RJ. Beyond the dual degree: development of a five-year program for leadership for medical undergraduates. Acad Med. 2008;83(1):52–58. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31815c63b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bush PJ, Johnson KW. Where is the public health pharmacist? Am J Pharm Educ. 1979;43:249–252. [Google Scholar]