Abstract

Objective. To assist curriculum committees and leadership instructors by gathering expert opinion to define student leadership development competencies for pharmacy curricula.

Methods. Twenty-six leadership instructors participated in a 3-round, online, modified Delphi process to define competencies for student leadership development in pharmacy curricula. Round 1 asked open-ended questions about leadership knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Round 2 grouped responses for agreement rating and comment. Round 3 allowed rating and comment on competencies not yet meeting consensus, which was prospectively set at 80%.

Results. Eleven competencies attained 80% consensus or higher and were grouped into 3 areas: leadership knowledge, personal leadership commitment, and leadership skill development. Connections to contemporary leadership development literature were outlined for each competency as a means of verifying the panel’s work.

Conclusions. The leadership competencies will aid students in addressing: What is leadership? Who am I as a leader? What skills and abilities do I need to be effective? The competencies will help curriculum committees and leadership instructors to focus leadership development opportunities, identify learning assessments, and define program evaluation.

Keywords: Delphi, leadership, instruction, competencies, curriculum

INTRODUCTION

Guideline 9.3 of the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education’s (ACPE) Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree states that “the college or school curriculum should foster the development of students as leaders and agents of change.”1 More specifically, the standards state that “The curriculum should…develop the ability to use tools and strategies needed to affect positive change in pharmacy practice and health care delivery.”1 The focus of leadership development is directed at abilities related to affecting positive change. In the context of curricular change, members of the academy supported the notion that “student pharmacists must develop the skills and desire to create positive change in their current and future practices.”2

To operationalize these accreditation guidelines, educators can draw upon previous work in the leadership development literature. Reports describing courses,3,4 a retreat,5 an institute,6 and practice experiences7 have been published describing student leadership development in pharmacy. In addition, the student leadership development literature outside of the profession provides numerous articles on instructional methods, resources, and assessment.

While the available literature provides direction, it does not define the desired competencies needed for student pharmacists. Defining competencies is necessary to focus the development of leadership learning opportunities, identify appropriate learning assessments, and define program evaluation. In fact, the value of defining competencies in health professions education has been described as “creat[ing] an environment that fosters empowerment, accountability, and performance evaluation which is consistent and equitable.”8

In pharmacy, groups of experts have been called together to define competencies in areas such as clinical pharmacy,9 and oncology pharmacy practice.10 Expert groups have also been used to define competencies in leadership. In 2000, the National Public Health Leadership Network defined 79 leadership competencies for public health professionals. They recommended that the work guide curriculum content and module development, as well as performance measures and evaluation methods.11

The aim of this work was to gather expert opinion to assist curriculum committees and leadership faculty members in defining student leadership development competencies for doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) curricula. In addition, this paper verifies and validates the collected pharmacy opinions with contemporary leadership development approaches from the leadership development literature.

METHODS

Competencies can be defined by drawing together a group of experts for dialogue, debate, and production of a report. However, the use of a Delphi process can ensure that consensus is achieved without the bias that can occur in discussions.12 During a Delphi process, the experts (referred to as panelists) provide opinions that are collected through a series of structured anonymous questionnaires, referred to as rounds. The responses from each round are summarized and fed back to the panelists for continued comment and rating of agreement. By reviewing round reports, panelists are made aware of items they may have missed and the group’s collective opinion. Therefore, opinions may be developed and reconsidered in a non-adversarial manner.13 This process has the added advantage of gathering opinions without bringing panelists together physically.

Delphi processes have been used to define competencies of student affairs professionals,14 and teachers.15,16 In particular, the Delphi has also been used in health professions education to bring together expert opinion to support national efforts for curriculum advancement in medical education17,18 and pharmacy.19

The methods used in this study are described in detail elsewhere.20 To be included in this study, participants were required to be a leadership instructor for PharmD students in the United States. Considering the pool of available experts, a panel size of 20-30 was deemed appropriate. In May 2011, potential participants were contacted via telephone to announce the study and then via e-mail with a link to a Web-based version of the consent form.

This study used a 3-round modified Delphi process, collecting participant responses via the Web-based survey software program Qualtrics (Qualtrics Labs Inc., Provo, UT). In responding, participants were asked to use the Rauch and Behling definition of leadership: “The process of influencing an organized group toward accomplishing their goals.”21 Round 1 asked open-ended questions regarding what students need to know and do related to leadership at entry to practice. Responses were reviewed by the authors for themes and summary statements were created. In round 2, panelists responded to the statements using a 5-point Likert rating system (ie, strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, strongly agree). Consensus was defined as a minimum of 80% of participants agreeing or strongly agreeing to a specific competency. After round 2, statements not reaching 80% were refined based on the comments received and returned for further rating and commenting in round 3. At the conclusion of the study, the competencies were grouped by the authors into 3 categories to facilitate discussion and use.

To assist in verifying and validating the results of the panel’s work, the leadership development literature was consulted and connections to this thinking are detailed in the results. This study was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

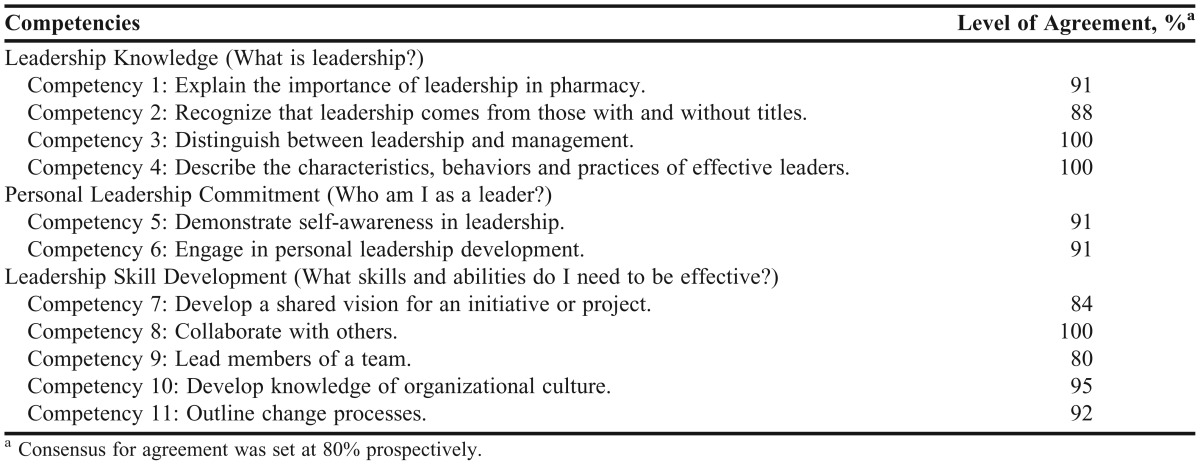

Twenty-six leadership instructors participated in the Delphi process. The panelists were 65% male, 62% from public institutions, and represented all of the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy/American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Districts. The process resulted in 11 competencies for student leadership development in PharmD curricula: explain the importance of leadership in pharmacy; recognize that leadership comes from those with and without titles; distinguish between leadership and management; describe the characteristics, behaviors and practices of effective leaders; demonstrate self-awareness in leadership; engage in personal leadership development; develop a shared vision for an initiative or project; collaborate with others; lead members of a team; develop knowledge of organizational culture; outline change processes. Each competency was supported by descriptors and additional detail provided by the experts participating. To provide further detail to curriculum committees and leadership instructors in designing and implementing leadership development opportunities, the panelist’s descriptions have been summarized in Appendix 1. The panelists’ level of agreement with each competency is listed in Table 1. There were several competencies that did not reach consensus, including “assisting others in developing leadership abilities” and “making a positive impact in circles of influence.”

Table 1.

Panel Agreement With the Identified Leadership Competencies

To facilitate communication and discussion, the 11 competencies were grouped into 3 areas: leadership knowledge, personal leadership commitment, and leadership skill development. The leadership development literature was used to provide support and to verify each competency. In addition, curricular implications and practical considerations are provided by the authors.

Leadership Knowledge

The Delphi panel identified 4 competencies aimed at building PharmD students’ knowledge of leadership as a discipline and leadership within the profession (Table 1). When competencies in leadership knowledge are attained, students will be able to address the question “What is leadership?” The knowledge gained by addressing the first 4 competencies will assist students in seeing themselves as leaders and understanding that leadership abilities can be developed.

Competency 1: Explain the importance of leadership in pharmacy. The need for leadership within pharmacy has been well articulated.1,22-28 Specifically, leadership has been identified by the profession as a characteristic of a professional29,30 and as an obligation.31 Students affirm their commitment to leadership when taking the Oath of a Pharmacist by stating that they will embrace and advocate for changes that improve patient care.32 To motivate and inspire student pharmacist engagement with leadership, attention to the need for leadership is important. Topics such as pharmacy history, current trends in pharmacy practice and health care, and issues facing the profession coupled with past leadership experiences may heighten the need for leadership with students.

Competency 2: Recognize that leadership comes from those with and without titles. To fully embrace their role as leaders, student pharmacists must develop a working definition of leadership that recognizes the full scope of leadership demonstrated within the profession. Without seeing the possibilities for personal engagement in leadership, there is little motivation for a personal investment in leadership development. A broadening view of leadership has been described as an essential component of leadership identity development.33,34 A broadening view of leadership includes recognition of positional and non-positional leadership and can be affected by developmental influences, such as involvement, reflective learning, peer influences, and influences from other, more experienced, adults.33 Careful attention should be paid to the influences on pharmacy students to ensure that they find leadership to be an attractive and realistic endeavor, whether via a title or without a title.

Competency 3: Distinguish between leadership and management. Students elect to participate in leadership or management roles based on their perceptions of expectations and requirements. While work has been done to clarify these roles, the terms are still used indiscriminately at times, causing confusion.35-37 Kotter explains that good management works to produce consistency and order through the development and refinement of processes (ie, planning, budgeting, organizing, staffing, controlling, problem solving). He states, “(leadership) produces movement,” which involves establishing direction, aligning people, and motivating and inspiring.36 Just as pharmacy educators work to be specific with health sciences terminology, appropriate use and interplay of these 2 functions should be considered in leadership education.

Competency 4: Describe the characteristics, behaviors, and practices of effective leaders. In addition to understanding the responsibilities of leaders, students need to understand that leadership skills can be developed. Kouzes and Posner have stated that “Leadership is not about personality; it’s about behavior.”38 In addition, leadership has to do with relationships.39 In particular, transformational leaders attend to development of followers, motivating them to accomplish more than is usually expected.40 Servant leadership, where the leader first aims to serve, aligns well with pharmacy’s patient-centered focus and achieving the common good.41 Furthermore, leaders may need to adapt their leadership style based on the situation.40 Because so many variables may be present in situations where leadership is practiced, a firm foundation on the characteristics, behaviors, and practices of effective leaders may increase the ability of graduates to be successful in multiple environments.

Personal Leadership Commitment

The Delphi panel identified 2 competencies that relate to a student’s personal commitment to leadership (Table 1). When these competencies are attained, students will be able to address the question “Who am I as a leader?” These competencies provide a foundation for success for making leadership contributions to the profession by supporting students in building self-awareness and gaining proficiency with personal leadership development.

Competency 5: Demonstrate self-awareness in leadership. Leaders must be aware of their own values and motivations. Credibility has been argued to be the foundation of leadership.42 As Kouzes and Posner explain, “Constituents rightfully expect their leaders to have the courage of their convictions. They expect them to stand up for their beliefs.” They argue for a journey of self-discovery that involves evaluating values, competence, and confidence.43 Similarly, George, in his model of authentic leadership, advocates for pursuing purpose, practicing solid values, leading with heart, and demonstrating self-discipline.44 Leaders must also be aware of their abilities. Consciousness of self, or being aware of your abilities and emotions, is a core facet of the Emotionally Intelligent Leadership model45 and a core capacity in the Social Change Model of Leadership Development.46 A firm self-awareness may result in students aligning themselves more closely with initiatives where they can be effective leaders and working better with those around them to achieve optimal team performance.

Competency 6: Engage in personal leadership development. Students need to recognize that becoming a better leader only happens when they “do leadership.”47 Disciplined practice is needed. Blumenthal et al summarize the leadership development literature and comment on common elements in effective leadership development programs.48 The authors state that iterative cycles of experience, reflection, and feedback are needed. In addition, students must commit to their self-development, which includes self-monitoring and willingness to seek and accept critical feedback. While logistically complex, an approach that challenges pharmacy students to learn by doing and reflect on ways to improve may result in enhanced leadership development.

Leadership Skill Development

The Delphi panel identified 5 competencies that focused on particular leadership skills (Table 1). When these competencies are attained, students will be able to address the question “What skills and abilities do I need to be effective? These competencies were considered foundational for all student pharmacists and reflect those needed as an entry-level pharmacist. Panelists recognized that additional leadership related skills may be required for some pharmacy roles and may be the subject of elective student leadership development opportunities, residency education, or continuing professional development.

Competency 7: Develop a shared vision for an initiative or a project. New graduates may not encounter or be assigned major leadership responsibilities as new practitioners, but most, if not all, will be involved in an initiative or a project. These vary from board of pharmacy compliance issues and safety standards to personnel training and immunization rates. Visioning is essential in conceptualizing such an initiative. The notion of animating the vision helps individuals align goals and enlist support for a vision or a “compelling picture practicing positive communication, expressing emotions, and speaking from the heart to enlist others in a shared vision.” 42 To achieve optimal personal and professional performance, we should instill in students the desire to imagine the future before setting out to achieve it.

Competency 8: Collaborate with others. Competency 9: Lead members of a team. Competency 8 and Competency 9 are inter-related. Colleges and schools of pharmacy have long supported learning in teams and have offered curricular methods (eg, study groups, group projects, service-learning) and co-curricular opportunities (eg, student and professional organizations) to encourage collaboration. Collaboration is a core competency of the Social Change Model of Leadership.46 As described in Competency 7 and the ACPE accreditation standards,1 interprofessional collaborations are emerging foci in academia and practice. The Interprofessional Education Collaborative generated a report entitled “Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice” which identified Competency Doman 4: Teams and Teamwork.49 Working as a team is often perceived as the optimal way to achieve positive outcomes in a variety of settings.

However, less often discussed is team leadership. Northouse states that understanding team leadership is essential to ensuring team success.40 More specifically, Kouzes and Posner42 describe 2 important team-relevant practices: “enabling others to act” (ie, fostering collaboration and strengthening others) and “encouraging the heart”50 (ie, recognizing contributions and celebrating victories). Delphi panelists expressed concerns about conflict resolution and accountability in team leadership development, and Lencioni offers guidance for addressing such team dysfunctions.51 Activities that not only assign students to work in teams, but work on developing their team dynamics should be pursued in leadership learning activities.

Competency 10: Develop knowledge of organizational culture. Competency 11: Outline change processes. These final 2 competencies may be the most challenging for a new graduate entering the profession. No matter how much leadership experience a student has acquired in a variety of organizations, he or she will be faced with a new language, expectations, and rules of engagement within a corporation, professional association, or community. At times these expectations and rules of engagement are veiled in the history and attitudes of the personnel or volunteers. While acclimating to a new culture, new practitioners are likely to seek innovations, improvements, and operational efficiencies in practice. However, before new practitioners can lead such changes, they must learn how to get things done within their practice, corporation, or location. Heifetz et al offer advanced strategies in Adaptive Leadership to help leaders navigate the turbulence encountered when leading adaptive challenges as opposed to technical difficulties.53 By working within their new culture, new graduates will discover (or create) the processes that enable change and the value of involving many people, in order to sustain the culture which supports change.

At times, leaders may be called to challenge the status quo. They may need to experiment and take risks. In fact, “challenging the process” has been defined as 1 of 5 practices of exemplary leaders.38,42 Change is central to the Social Change Model which connects individual (consciousness of self, congruence, commitment); group (collaborations, common purpose, controversy with civility); and community (citizenship) values.46 Few leadership books and articles speak to these essential competencies to become proficient in a new culture and lead change. However, Kotter has recommended an 8-step process for leading change which incorporates culture and process and which requires patience and discipline to pursue all 8 steps.53-55 By establishing a sense of urgency, creating the guiding coalition, developing a change vision, and communicating the vision for buy-in, the effective leader will also empower broad-based action, generate short-term wins, never let up, and incorporate changes into the culture. Achievement of competence in organizational culture and change processes involves many of the previously mentioned competencies and serves as a capstone in a future leader’s development.

DISCUSSION

The 3-round Delphi process with leadership instructors in pharmacy resulted in 11 leadership competencies. This study represents a first step in defining competencies for student leadership development. Articulating and sharing competency statements is important for setting student expectations for leadership development programs. For engaged students, presenting and discussing the desired competencies can provide a “roadmap” to guide their engagement. In particular, the questions (ie, What is leadership? Who am I as a leader? What skills and abilities do I need to be effective?) should help students in appreciating the practicality and relevance of their studies and practice in this area.

One of the concerns in qualitative research is the credibility, dependability, or trustworthiness of the results (ie, validity). To assist in addressing this concern, the leadership development literature was consulted and applicable literature is cited in the results. This literature will also be a resource to leadership instructors and design teams when initiating or refining student leadership development opportunities.

Shertzer and Schuh found that students without a strong leadership history had a lack of confidence, a lack of interest in leadership and self-perceived deficiency in leadership skills.56 These students will present an instructional challenge for faculty members. Establishing the relevance of the topic to them personally will be critical. In addition, faculty members, curricula, and other students will be important in demonstrating and reinforcing the guiding principles for student leadership development,20 particularly that “leadership is important for all student pharmacists to develop” and “leadership can be learned.”

For colleges and schools that are committed to initiating or expanding leadership development opportunities, these competencies can assist curriculum committees and leadership instructors in focusing and refining their efforts. It may be helpful to review each competency and ask: Do our leadership instructors concur with this competency? If not, how should the statement be customized to our institution? Does our broader faculty concur with this competency? If not, what discussions need to occur to arrive at a shared vision and commitment for student leadership development at our college/school? It may also be helpful to ask: Does our curriculum support the development of this competency? Do our graduates demonstrate this competency?

For leadership instructors, the competencies will aid in guiding curricular design. Clearly, didactic, experiential, and self-directed opportunities for competency development will be needed. Leadership development faculty members will likely need to collaborate with other faculty member in order to thread leadership opportunities throughout the curriculum, while also working to provide those opportunities with appropriate context, support, and evaluation. Partnership with student organizations may also be in order. Innovation will be needed. In addition, scholarship in methods for delivery and evaluation of initiatives is encouraged. Furthermore, the competencies will guide faculty professional development. The competencies aid in identifying the content areas where faculty members will need to develop their own knowledge of leadership. The competencies may also point to areas where faculty members need to build awareness of previously investigated student leadership development techniques (ie, methods, assessments) in order to effectively foster competency development in students.

For curriculum committees, the competencies provide impetus for discussions on the resources needed to support student leadership development. A supportive culture, as well as high-level administrative sponsorship and involvement, has been identified as a critical factor in successful leadership development programs.48 A clear commitment is needed for the necessary instruction, development opportunities, and mentoring/advising/coaching required to attain the desired competencies. In addition, the competencies provide a starting point for defining and structuring an evaluation plan.

This study focused on responses from pharmacy leadership instructors. Research that includes pharmacy faculty members with additional disciplinary foci and leadership instructors from other health professions could yield new insights related to these competency areas. In addition, the Delphi method does not use traditional sampling. However, additional research that systematically samples leadership instructors for representation on desired characteristics could be conducted.

This Delphi study was limited to 3 rounds. Because of the limited number of rounds, it is unclear whether non-consensus topics simply require more discussion and refinement or whether those topics were inappropriate as entry-level competencies for student pharmacists.

It can be daunting to consider development of these competencies among large groups of students and in situations with constrained resources (eg, curricular time, instructor availability). Given that the panelists were leadership instructors, perceived feasibility may have influenced their recommendations. In addition, the assessment of leadership competencies can be difficult and time consuming. Potential hurdles and barriers to being able to measure and assess attainment of the competencies may have influenced recommendations.

Pharmacy leadership educators would benefit from additional research on models and approaches to leadership development that are effective with student pharmacists. Although there is literature on leadership education and leadership development in many disciplines, it must be adapted. As colleges and schools transition from offering leadership electives for interested students to leadership instruction for all students, new instructional challenges may arise and require investigation, such as methods for establishing relevance and motivation for those who may not perceive themselves to be leaders.

Leadership assessment is also an area requiring examination. Reports on the use of existing leadership assessments with student pharmacists would be helpful. As the work in leadership evolves, pharmacy educators may find that new leadership assessment instruments may need to be developed. Furthermore, research on competency attainment would be valuable in understanding the difficulties associated with developing these competencies, along with research on leadership program evaluation to assist in understanding resource implications.

CONCLUSIONS

Eleven leadership competencies identified by a panel of pharmacy faculty members with experience as instructors of leadership describe those competencies required of all student pharmacists at entry to practice. The defined competencies will aid students in addressing: What is leadership? Who am I as a leader? What skills and abilities do I need to be effective? The competencies are consistent with contemporary leadership development approaches outside of the profession of pharmacy. The competencies will help curriculum committees and leadership instructors to focus the development of leadership learning opportunities, identify appropriate learning assessments, and define program evaluation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Claire Kolar for her support in managing the qualitative data.

Appendix 1. Descriptions of Leadership Competencies for Student Leadership Development in Pharmacy

Initial responses from Delphi panelists were used to create the competencies, which were rated for consensus in subsequent rounds of the process. In addition, direct responses from the panelists were developed by the authors into the following descriptive narratives to further elaborate upon the desired competencies.

Leadership Knowledge (What is leadership?)

Competency 1: Explain the importance of leadership in pharmacy. (91% agreement)

Panelists articulated the importance of students being able to define leadership and describe the need for leadership within the profession. Students should base this need off of an understanding of the history of our profession and the current issues facing pharmacy and health care. Students should appreciate that leadership provides opportunities to change things for the better. This change can be fostered through navigation of advocacy efforts on a local, state, and national level. Ultimately, this level of understanding of leadership should prompt all pharmacists to engage in and expect effective leadership that results in people and groups achieving more. Faculty members and curricula should assist students in developing an appreciation of the profession’s history of and need for leadership.

Competency 2: Recognize that leadership comes from those with and without titles. (88% agreement)

Panelists described that students should recognize that leadership is not about a position or title. Students should understand that anyone can influence his or her environment and make a difference. Regardless of their standing or title, students should recognize that any role they possess has leadership possibilities. Students should expect, based on professional obligations, that at some point in their professional life, they will be called to serve in a leadership capacity. Faculty and curricula should work to facilitate a broadening view of leadership.

Competency 3: Distinguish between leadership and management. (100% agreement)

Panelists stated that students should be able to compare and contrast leadership and management. In making this distinction, students should appreciate balancing both activities in the process of creating positive change. Faculty members and curricula should help students to be sensitive to this distinction and to recognize the importance of both roles.

Competency 4: Describe the characteristics, behaviors and practices of effective leaders. (100% agreement)

Panelists commented about the need for students to identify the characteristics of leaders and followers, recognizing that leadership is a reciprocal process centered on the leader-follower relationship. Panelists stated that a leadership style aligning with a service orientation was the most productive for pharmacy. In addition, recognition of basic leadership theories and models was important to apply to pharmacy practice. Panelists commented on the importance of situational leadership and understanding the related behaviors and actions of exemplary leaders faced with different situations. Faculty and curricula should familiarize students with various leadership theories and models and facilitate application to professional and personal responsibilities.

Personal Leadership Commitment (Who am I as a leader?)

Competency 5: Demonstrate self-awareness in leadership. (91% agreement)

Panelists stated that one must first lead oneself before leading others. Students should recognize their own leadership strengths, weaknesses, abilities, and styles, and how they affect their ability to lead effectively. Students should develop their emotional intelligence, maturity, and personal vision, and navigate work-life balance. Finally, students should be aware that their characteristics impact the dynamics of a team or group. Faculty members and curricula should provide students with opportunities to develop and demonstrate self-awareness.

Competency 6: Engage in personal leadership development. (91% agreement)

Panelists commented that most good leaders are made and leadership emerges over time. Students should acknowledge that they are responsible for their leadership development, and they should have a plan for personal growth. Students should be able to use basic readings about leadership to broaden their perspective and realize that discovery coupled with mentorship can lead to continuous leadership development. Actively seeking opportunities to apply lessons learned as a student can ultimately lead to lasting leadership skills. Faculty and curricula should engage students in self-directed and individualized learning activities focusing on personal leadership development.

Leadership Skill Development (What skills and abilities do I need to be effective?)

Competency 7: Develop a shared vision for an initiative or project. (84% agreement)

Panelists described that students should be able to develop a vision, whether that vision applies to one’s own practice or for an organization or broader initiative. Students should recognize strategies for how their professional and personal visions can be fostered. When operationalizing a vision for a broader initiative or in an organization, developing a shared vision is imperative for a team. Once the vision is developed, students should be able to articulate how to bring people together around a shared vision. Faculty members and curricula should provide opportunities for students to exercise skills in visioning through early involvement in initiatives or projects of personal and/or professional significance.

Competency 8: Collaborate with others. (100% agreement)

Competency 9: Lead members of a team. (80% agreement)

Panelists stated that students should recognize more can be done in teams than as individuals. Students should be able to recognize and recruit talent that will help to further a team’s goals. The ability to build effective teams and identify optimal roles for each member by seeking input should be fostered. To do so, students should cultivate interpersonal skills such as effective communication and be able to develop and maintain good relationships with others. Students should develop a plan to create buy-in and then provide support and encouragement to motivate others to reach a common goal while still holding everyone accountable. The leader needs to empower, collaborate with, and demonstrate appreciation to the members of the team. Students should also have good listening skills and be able to problem solve. When working as members of a team, the panelists commented that students should develop measurable goals and be able to lead a team to accomplish those goals by bringing together the knowledge and skills of diverse individuals. Specific team processes mentioned include the ability to develop consensus, manage interpersonal conflict, and conduct an effective meeting. Faculty members and curricula should provide opportunities for students to work together with peers and practice leading initiatives and projects as a part of teams with a special emphasis on the processes to build effective teams.

Competency 10: Develop knowledge of organizational culture. (95% agreement)

Competency 11: Outline change processes. (92% agreement)

Panelists concurred that students should develop an awareness of organizational culture and realize development often involves immersion within an organization. Specifically, students should identify what it takes to motivate others to change and effectively communicate with others in an organization. As the organizational culture is learned, panelists also stated that students should know the importance of change and recognize everyone is responsible for influencing change regardless of title or position. Students should recognize the need for leadership within an organization and describe the process of attaining a leadership position. Students should exert themselves as leaders and apply principles and tools to effectively lead change processes in pharmacy practice on behalf of their patients. Faculty and curricula should prepare students for the difficulty of change processes and equip them to participate in steps of change, working with others and within the existing culture, climate, and processes of organizations with which they may affiliate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/FinalS2007Guidelines2.0.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jungnickel PW, Kelley KW, Hammer DP, Haines ST, Marlowe KF. Addressing competencies for the future in the professional curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8):Article 156. doi: 10.5688/aj7308156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyle CJ, Beardsley RS, Hayes M. Effective leadership and advocacy: amplifying professional citizenship. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(3):Article 63. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorensen TD, Traynor AP, Janke KK. A pharmacy course on leadership and leading change. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(2):Article 23. doi: 10.5688/aj730223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janke KK, Traynor AP, Sorensen TD. Student leadership retreat focusing on a commitment to excellence. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(3):Article 48. doi: 10.5688/aj730348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tran K, Fjortoft N, Glosner S, Sundberg A. The student leadership institute. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2005;62(14):1442. doi: 10.2146/ajhp040499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knoer SJ, Rough S, Gouveia WG. Student rotations in health-system pharmacy management and leadership. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2005;62(23):2539–2541. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verma S, Paterson M, Medves J. Core competencies for health care professionals: what medicine, nursing, occupational therapy and physiology share. J Allied Health. 2006;35(3):109–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.6.806. Burke JM, Miller WA, Spencer AP,et al. Clinical pharmacist competencies. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(6):806-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrington C, Weir J, Smith P. The development of a competency framework for pharmacists providing cancer services. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2011;17(3):168–178. doi: 10.1177/1078155210365582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright K, Rowitz L, Merkle A, et al. Competency development in public health leadership. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1202–1207. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams PL, Webb C. The Delphi technique: a methodological discussion. J Adv Nurs. 1994;19(1):180–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burkard A, Cole D, Ott M, Stoflet T. Entry-level competencies of new student affairs professionals: a Delphi study. NASPA J. 2004;42(3):283–309. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith K, Simpson R. Validating teaching competencies for faculty members in higher education: a national study using the Delphi method. Innov Higher Educ. 195;19(3):223–234. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tigelaar DEH, Dolmans DH, Wolfhagen IHAP, Van der Vleuten CPM. The development and validation of a framework for teaching competencies in higher education. Higher Educ. 2004;48:253–268. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiessling C, Dieterich A, Fabry G, et al. Communication and social competencies in medical education in German-speaking countries: the Basel consensus statement. Results of a Delphi survey. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81(2):259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Penciner R, Langhan T, Lee R, Mcewen J, Woods RA, Bandiera G. Using a Delphi process to establish consensus on emergency medicine clerkship competencies. Med Teach. 2011;33(6):e333–e339. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.575903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrne A, Boon H, Austin Z, Jurgens T, Raman-Wilms L. Core competencies in natural health products for Canadian pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(3):Article 45. doi: 10.5688/aj740345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Traynor AP, Boyle CJ, Janke KK. Guiding principles for student leadership development in the doctor of pharmacy program to assist administrators and faculty members in implementing or refining curricula. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(10):Article 220. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rauch CF, Behling O. Functionalism: basis for alternate approach to the study of leadership. In: Hunt J, Hosking D, Schriesheim C, Steward R, editors. Leaders and Managers. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press; 1984. pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sawyer WT. Chair report of the 1995-96 professional affairs committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 1996;60(Winter):15S–17S. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith WE. Chair report for the professional affairs committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64(Winter):21S–24S. [Google Scholar]

- 24.American College of Clinical Pharmacy. ACCP white paper: A vision of pharmacy’s future roles, responsibilities, and manpower needs in the United States. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20(8):991–1020. doi: 10.1592/phco.20.11.991.35270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White SJ. Will there be a pharmacy leadership crisis? An ASHP foundation scholar-in-residence report. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2005;62(8):845–855. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/62.8.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White SJ. Leadership: successful alchemy. Harvey A.K. Whitney Lecture. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2006;63:1497–1503. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerr RA, Beck DE, Doss J, et al. Building a sustainable system of leadership development for pharmacy: Report of the 2008-09 Argus Commission. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8):Article S5. doi: 10.5688/aj7308s05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mason HL, Assemi M, Brown B, et al. AACP reports: report of the 2010-2011 Academic Affairs Standing Committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(10):Article S12. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7510S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Pharmaceutical Association Academy of Students of Pharmacy. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Council of Deans Task Force on Professionalism. White paper on pharmacy student professionalism. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2000;40(1):96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP statement on professionalism. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2008;65:172–174. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Statement on leadership as a professional obligation. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2011;68(23):2293–2295. doi: 10.2146/sp110019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Oath of a pharmacist. http://www.aacp.org/resources/studentaffairspersonnel/studentaffairspolicies/Documents/OATHOFAPHARMACIST2008-09.pdf. Accessed September 22, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Komives SR, Owen JE, Longerbeam SD, Mainella FC, Osteen L. Developing a leadership identity: a grounded theory. J Coll Stud Dev. 2005;46(6):593–611. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Komives SR, Longerbeam SD, Owen JE, Mainella FC, Osteen L. A leadership identity development model: applications from a grounded theory. J Coll Stud Dev. 2006;47(4):401–418. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaleznik A. Managers and leaders: are they different? Harv Bus Rev. 1977 product no 8334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kotter JP. A Force for Change: How Leadership Differs from Management. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1990. pp. 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kotter JP. What leaders really do. Harv Bus Rev. December. 2001:85–96. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kouzes JM, Posner BZ. The Student Leadership Challenge: Five Practices for Exemplary Leaders. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2008. pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Komives SR, Lucas N, McMahon TR. Exploring Leadership: For College Students Who Want to Make a Difference. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons; 2007: 74. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Northouse PG. Leadership: Theory and Practice. 5th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications; 2010: 89, 171, 242. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greenleaf RK. Servant Leadership. New York, NY: Paulist Press; 2002. p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kouzes JM, Posner BZ. The Leadership Challenge. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: 2007: 14, 27–41, 60. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kouzes JM, Posner BZ. Credibility: How Leaders Gain and Lose It, Why People Demand It. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 2003. p. xxi. [Google Scholar]

- 44.George B. True North: Discover Your Authentic Leadership. John Wiley & Sons; 2007. p. xxxi. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shankman ML, Allen SJ. Emotionally Intelligent Leadership: A Guide for College Students. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 2008. pp. 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- 46.A Social Change Model of Leadership Development Guidebook (Version III). Los Angeles, CA: University of California Higher Education Research Institute; 1996. http://www.heri.ucla.edu/PDFs/pubs/ASocialChangeModelofLeadershipDevelopment.pdf. Accessed September 27, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Posner BZ. From inside out: beyond teaching about leadership. J Lead Educ. 2009;8(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blumenthal DM, Bernard K, Bohnen J, Bohmer R. Addressing the leadership gap in medicine: residents’ need for systematic leadership development training. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):513–22. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31824a0c47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Washington, DC: Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: Report of an Expert Panel. Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. http://www.aacp.org/resources/education/Documents/10-242IPECFullReportfinal.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kouzes JM, Posner BZ. Encouraging the Heart: A Leader’s Guide to Rewarding and Recognizing Others. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lencioni P. The Five Dysfuncions of a Team. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishing; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heifetz R, Grashow A, Linsky M. The Practice of Adaptive Leadership. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kotter JP. Leading Change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kotter J, Rathgerber H. Our Iceberg Is Melting: Changing and Succeeding Under Any Conditions. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kotter J, Cohen D. The Heart of Change: Real-Life Stories of How People Change Their Organization. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shertzer JE, Schuh JH. College student perceptions of leadership: empowering and constraining beliefs. NASPA J. 2004;42(1):111–131. [Google Scholar]