BACKGROUND AND CHARGES

According to the Bylaws of AACP, the Professional Affairs Committee is to study issues associated with the professional practice as they relate to pharmaceutical education, and to establish and improve working relationships with all other organizations in the field of health affairs. The Committee is also encouraged to address related agenda items relevant to its Bylaws charge and to identify issues for consideration by subsequent committees, task forces, commissions, or other groups.

President J. Lyle Bootman charged the 2012-2013 American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Standing Committees with issues related to transforming healthcare.1 President Bootman encourages AACP institutional and individual members to “get to all the right tables of influence at the right time” and recognizes the local/state partnerships that member schools/colleges have with other stakeholders in health care can and does result in improving health care. Specifically, the 2012-2013 Professional Affairs Committee is charged to:

(1) Identify successful practices in the development and maintenance of effective relationships between state pharmacy organizations and schools/colleges of pharmacy and

(2) Recommend strategies related to state and local policy developments to optimally position pharmacists in health reform initiatives.

Members of the Professional Affairs Committee (PAC) include faculty from multiple disciplines from various schools/colleges of pharmacy as well as two executive directors of state pharmacy associations from the National Alliance of State Pharmacy Associations (NASPA). Prior to an in-person meeting of the committee, pertinent background information and resource materials were distributed and a conference call was held to develop a strategy, for addressing committee charges. The majority of committee members met for a day and a half in Crystal City, Virginia on October 29-30, 2012 to discuss the various facets related to this issue as well as to develop a process and strategies for addressing the charges. The committee members not able to meet in person were teleconferenced in during the Virginia meeting to provide their input. Following the process development and delegation of assignments related to the committee charges, the PAC communicated via electronic communications as well as through personal exchanges via telephone and email. The result is the following report, which discusses the elements and importance of a recognized relationship between pharmacy organizations, specifically professional organizations at the state level and boards of pharmacy as well as successful practices and strategies to guide the academy to be present and active at the “tables of influence” that will enhance the profession and improve patient care.

INTRODUCTION

The PAC believes the recommendations in this report are fundamental to the association’s future. We approached our charges with the understanding of addressing inter-connectivity, reform, and transformation. Jim Collins’ Good to Great2 premise includes the thought that a ‘good’ performance is often the enemy of achieving greatness. The Committee discussed this concept and identified that in the past, schools/colleges of pharmacy have been comfortable with competitive pools of applicants and high placement rates thanks in large part to the numerous opportunities and demand for pharmacists. This comfort level, along with the different missions of schools/colleges of pharmacy, professional associations, and state boards of pharmacy has prevented our profession from working together in an effective united effort to make sure that we are at the “right tables of influence at the right time.” This has contributed to our profession now struggling with our identity and place in a dynamic healthcare environment. The pharmacy profession has been left out of important discussions needed for recognizing the value that pharmacists must bring to providing patient care in an integrated team approach, as well as enhancing public health issues and society at large. While this value has been articulated as something that the profession as a whole shares, we, the pharmacy academy must share responsibility for ourselves as well as our graduates for not being “at the right tables.”

As a Committee, we believe that we can no longer continue in the same manner that has been the case in previous years where we have enjoyed professional and financial success. It is time for academia to climb out of our “ivory towers” and make it a priority to become involved in national, state, and local endeavors and join with our statewide partners to change our practices. Now is the time for the profession to develop ‘anti-fragility’3 as it is those organizations or individuals who have this quality who will be more successful than more fragile organizations settled in their ways.

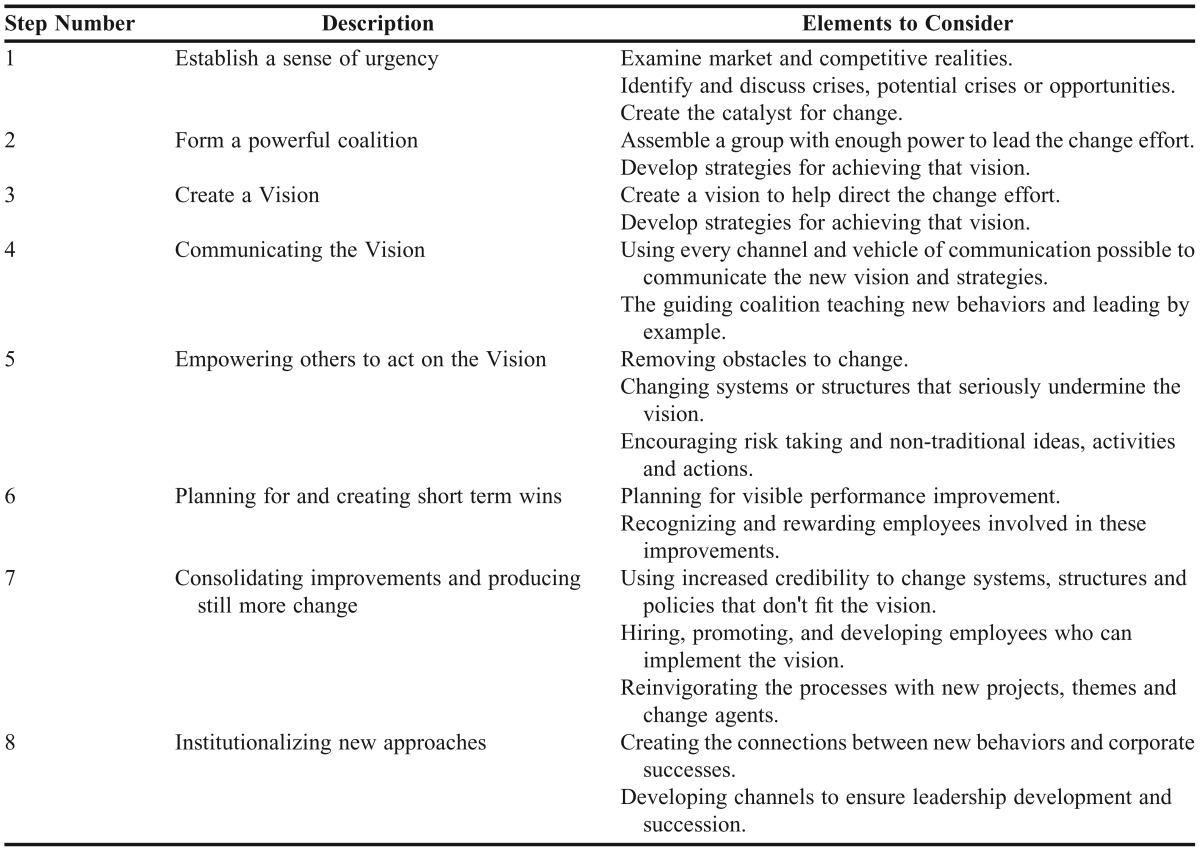

In considering how to address these necessary changes, the Committee reviewed Kotter’s 8 steps for leading change (Table 1).4 Becoming involved in activities that will make a difference for the profession is not the sole responsibility of the Deans and leadership teams, but is a responsibility of every faculty member. However, to do so, the PAC identified that a change is needed in how faculty are recognized and evaluated for their scholarship of engagement in these types of activities. Barker5 describes the scholarship of engagement as “practices cutting across disciplinary boundaries and teaching, research, and outreach functions in which scholars communicate to and work both for and with communities.” It is time for the pharmacy academy to value the work that our colleagues pursue in outreach and advancement efforts in our professional and personal communities and to assist them in documenting their efforts.

Table 1.

Kotter’s 8-Step Process for Change4

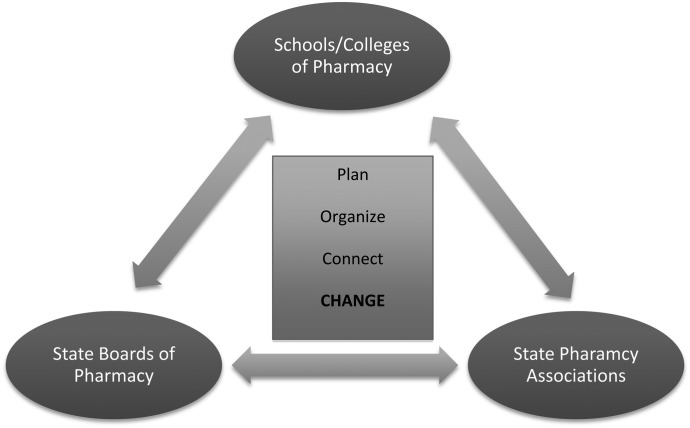

As we consider our professional communities and this scholarship of engagement, it is important for us to realize that pharmacy education is only one of three critical parties in the advancement of the role that pharmacists must play in patient care. We, schools/colleges of pharmacy, must form effective and nimble relationships and coalitions between our state pharmacy practice associations and boards of pharmacy (Figure 1). Recognized triad relations are the only way we collectively address the key issues that are quickly evolving in patient care through the Accountability Care Act or other health reform initiatives. This requires us as schools/colleges of pharmacy to unite with our Boards of Pharmacy as well as the various state pharmacy practice organizations as we reach out to other key stakeholders. In particular, stakeholders that should be considered in these discussions include the various employers of our graduates: managed care and health insurance management companies, legislative bodies, local, state and national governmental offices, and other foundations or professional practice groups associated with health and health professions. These relationships must be based upon a premise of trust and openness with the collective vision to advance pharmacy practice and ensure the pharmacist’s role in efforts to improve patient care. Isolated interactions between any two of these organizations without a framework for success may result in short-term gains when working with specific areas or projects, but often falter when dealing with complex issues raised by individuals and groups outside pharmacy education, professional practice and regulatory or safety issues. An example of this type of collaborative relationship can be found with the Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners (JCPP), a group of national pharmacy practice organizations, including AACP, NASPA, seven pharmacy practice associations, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP). This Commission was formed in 1977 to discuss, prioritize, and act on how pharmacists will practice and how pharmacy practice will benefit society.6

Figure 1.

Triad relationship between schools/colleges of pharmacy, state boards of pharmacy, and state pharmacy associations.

The development of trust and openness between schools/colleges of pharmacy with state pharmacy associations and boards of pharmacy can only be solidified if we are to make conscious efforts to ensure we have representation from the other two groups on any activities that we are developing and relevant to key issues for each of these groups. We each have a key interest in the success of the other two groups and our successes are certainly interconnected in each of our various visions, missions and goals. We cannot forget how interconnected we are be it educating future pharmacists and providing the scholarship/research to improve practice (schools/colleges of pharmacy), advancing and protecting public health (state boards of pharmacy) and advocating and leading the advancement of professional practice and the role that pharmacists play in patient care in all settings (state pharmacy associations). Our individual organization success will not occur without supporting and valuing those of the other two groups and playing a role in advancing their successes. In the words of Helen Keller, “Alone we can do so little; together we can do so much.”

It, therefore, becomes imperative that we as pharmacy educators must be willing to engage and actively participate in state pharmacy associations and with our boards of pharmacy. The strength of this tripartite relationship is only as strong as the individual linkages and when we take the initiatives to be inclusive with the other two key groups when considering new endeavors as it relates to advancing the role that pharmacists must play in health care and wellness. Specific examples include educators being willing to take leadership roles in state professional practice associations and serve on our Boards of Pharmacy. Likewise, the academy must take the initiative to include and listen to the key individuals from our state associations and boards of pharmacy in activities associated with our educational, service and research/scholarly activities in our schools/colleges of pharmacy. Working to develop effective and sustaining relationships between these three groups is the foundation for moving the profession forward in today’s rapidly evolving healthcare environment and changing approaches for patient care.

The value of successfully establishing this triad relationship between schools/colleges, professional practice organizations and boards of pharmacy within our states is that it enables the collective intellectual capacity to be applied to key challenges or opportunities that may affect one or more of these organizations. It enables us to work collaboratively with the other two groups to address issues and to identify strategies to plan, organize, connect and lead change on the multitude of known current issues and future issues that will certainly arise with advances and constraints in all areas. The key to these successful relationships includes critical and thoughtful listening to better acknowledge and understand the constraints faced in the academy, in professional practice and in our boards of pharmacy. We must find the time to engage in these relationships and those who do engage must be recognized for their efforts in advancing these relationships in their individual organizations. We also must be willing to learn from the other organizations in our varied interactions. Without a willingness to learn from each other and to be able take this knowledge to advance common causes our successes may be short-lived. We hear about learning organizations,7,8 but this triad must also become a collective learning group if there is to be long-term sustainability in these relationships. The success of one group should be celebrated by the other two as a collective achievement given our interconnectedness.

Success can only be achieved if we, those individuals providing the bridge to the other two groups have an openness and willingness to understand the constraints and challenges associated with education, practice and legal aspects associated with the other organizations. Recognizing that we are only as strong as the links of this triad, we can strengthen these important links by serving as champions and problem solvers not only for our own causes and issues, but to help the other two groups in their associated challenges and opportunities. It was the Dalai Lama XIV that reminds us that “Our ancient experience confirms at every point that everything is linked together, everything is inseparable.” Very few individuals would disagree that we as schools/colleges of pharmacy would not be able to achieve our vision, mission or goals if there were not either boards of pharmacy or professional organizations and their dedication, commitment and intellectual capacity. Likewise, boards of pharmacy and professional organizations would not be successful without our graduates and the scholarship and intellectually capacity offered by our programs in the individuals we educate and the faculty members in our programs.

There are certainly excellent examples of successful practices, described below, that were identified in a recent Council of Deans and National Association of Boards of Pharmacy survey. In addition, this report provides some examples of successful practices involving the triad relationship that were acquired from schools/colleges of pharmacy.

PAC Charge #1: Identifying successful practices in the development and maintenance of effective relationships between state pharmacy organizations and schools/colleges of pharmacy.

A review of the literature was performed to identify successful collaborative practices between schools/colleges of pharmacy and state pharmacy organizations. Collaborative efforts include those directly affecting schools/colleges curricula to those having an impact on practicing pharmacists. Pharmacy associations have been involved in self-study committees at schools/colleges of pharmacy preparing for their accreditation review.9 Elective courses in political advocacy10,11 and leadership and advocacy12 allow student pharmacists to be informed and integrated into local and state pharmacy issues as well as interact with professionals involved in state pharmacy associations. Some pharmacy schools have partnered with their state associations on student leadership programming.13 Pharmacy preceptor training opportunities have occurred in various settings, including state pharmacy association meetings.14,15 Mentoring student pharmacists during their pharmacy school experience16 as well as on potential career pathways17 have been described as an effective collaboration between schools/colleges and associations. Emergency preparedness and response at the local and state level has been an effective public health collaboration involving schools/colleges, state associations and other stakeholders.18,19 Continued professional development for practicing pharmacists is another area of collaboration between schools/colleges, boards of pharmacy, and associations.20,21 Collaborations of these types and others22 will assist in ensuring that pharmacy practice continues to advance to improve patient care.23

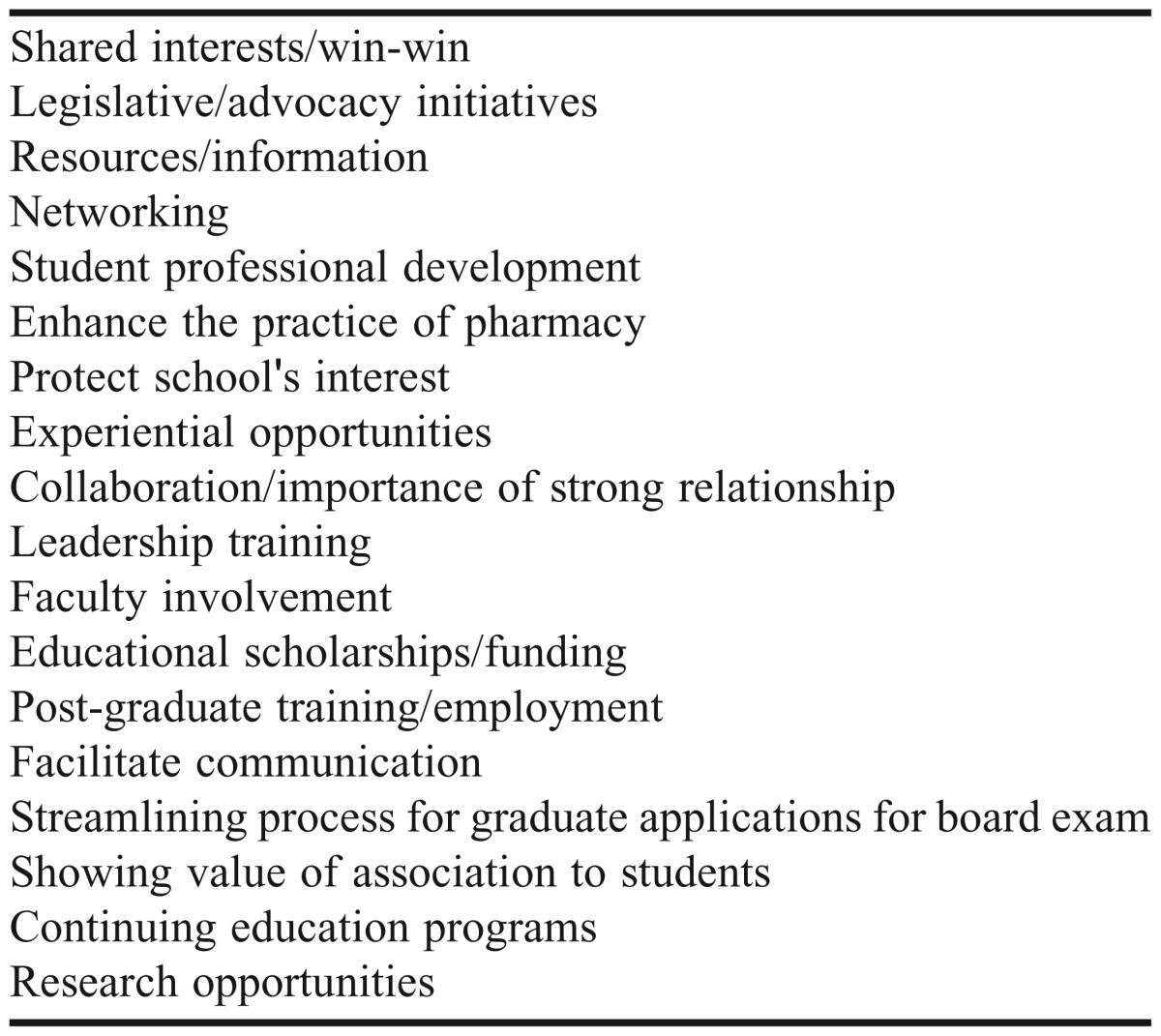

To further investigate the current relationships and successful practices between schools/colleges of pharmacy and state pharmacy associations, the PAC created an online inquiry to deans of schools/colleges of pharmacy and NASPA state pharmacy executive directors. The inquiry questions asked about the collaborative relationship between the two entities, why a collaborative relationship was (or has not been) developed between the two entities, what processes are suggested to develop or maintain the collaborative relationship as well as describing at least one program, initiative, tool, or other element that could be considered a “best practice” between the two entities. Participants were asked their state, but not their school/college of pharmacy or state pharmacy association. There was also a checklist containing some common collaborative efforts between schools/colleges of pharmacy and state pharmacy associations, such as annually partnering on legislative activities. The inquiry was sent to both the AACP Council of Deans listserv and to the executive directors of state pharmacy associations via the NASPA listserv in early October 2012 and was available for two weeks. A reminder was sent to the groups one week after the initiation of the online inquiry.

There were 63 responses from the Council of Deans inquiry and 35 responses from the NASPA inquiry. All responses were categorized into the eight National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP) districts, which are comprised of states/provinces grouped regionally.24 All eight districts were represented in both the Council of Deans and NASPA inquiry responses. Table 2 provides the reasons provided as to why a collaborative relationship(s) was developed between schools/colleges of pharmacy and state pharmacy associations. The most frequently cited reasons include student professional development, legislative/advocacy initiatives, and enhancement of the practice of pharmacy.

Table 2.

Reasons for Schools/Colleges of Pharmacy and State Pharmacy Associations to Develop a Collaborative Relationship

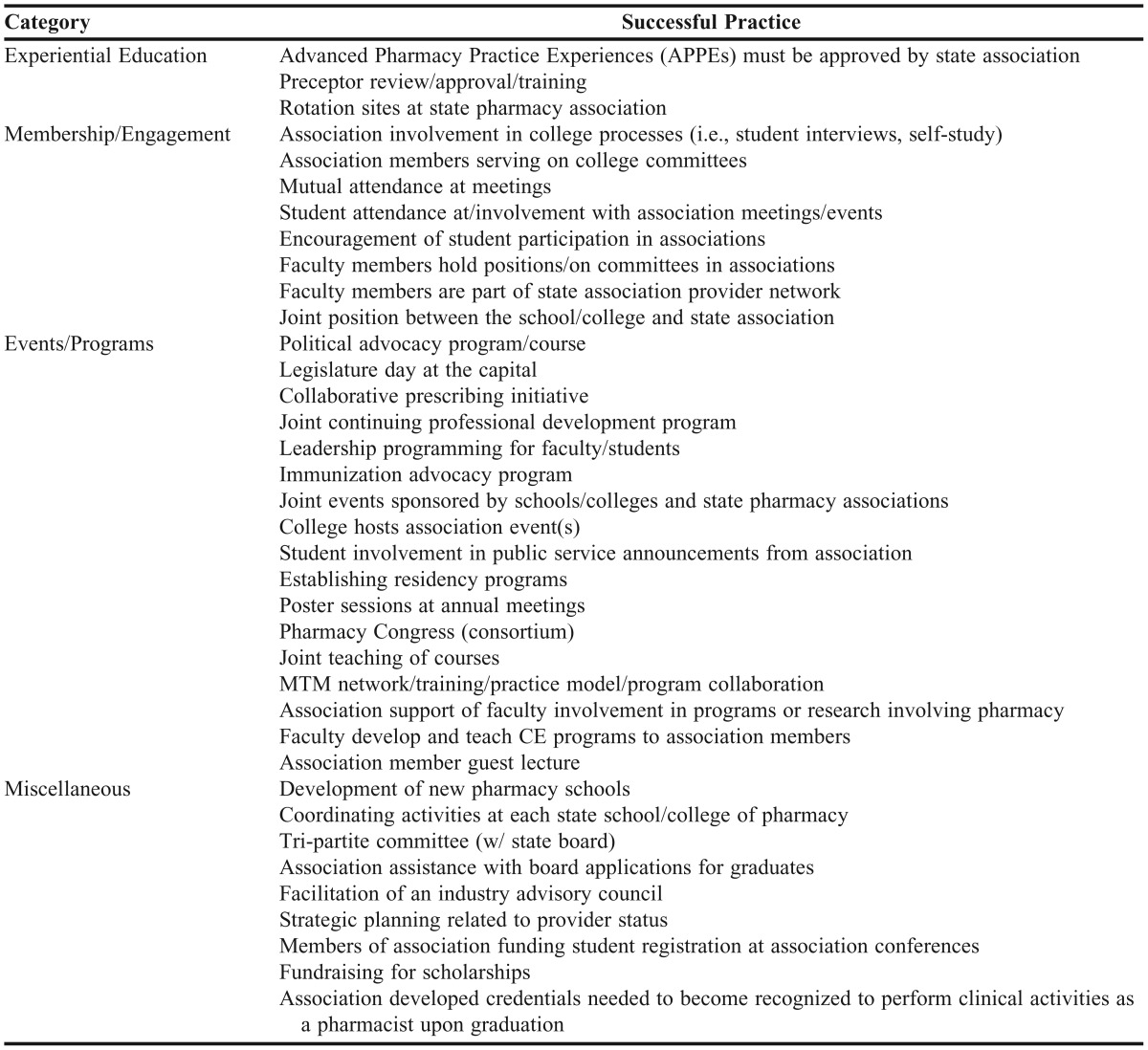

Table 3 lists successful practices identified from the online inquiries. The collaborative practices reported most commonly included experiential preceptor training, student pharmacist attendance at and involvement with association meetings and events, political advocacy programs, courses, and state legislative days, and working on emerging practice models (i.e., pharmacist immunization expansion). The inquiry provided suggestions for processes or approaches to develop or maintain collaborative relationships between schools/colleges of pharmacy and state pharmacy associations. The majority of responses included involving students, faculty, and practicing pharmacists (including preceptors) in collaborative efforts as well as exploring current and future areas of collaboration (especially as it related to advancing pharmacy practice at the state level). This inquiry provides evidence that schools/colleges of pharmacy and state pharmacy associations have developed many areas of collaboration and have many potential avenues to explore as health care and pharmacy practice continues to evolve.

Table 3.

Successful Practices Identified by Council of Deans and NASPA Inquiries

PAC Charge #2: Recommend strategies related to state and local policy developments to optimally position pharmacists in health reform initiatives.

Individuals Working Towards Getting at the Right Tables: Work small, think big! The perception by some may be that pharmacy has no power to affect change and that someone else will take care of it. The reality is that everyone can do something and that collectively it can make a difference as embodied by a quote widely attributed to Margaret Mead, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.” A protein chemist by the name of Edwin Cohn is a good example of a leader who embraced change and took responsibility for a project that continues to have profound implications for patient care. His example illustrates how a small group of dedicated individuals can make a difference. At the beginning of World War II, the US government embarked on an effort to obtain and mobilize the large quantities of blood anticipated for the war effort, but storage and contamination issues plagued whole blood and liquid plasma products. While pharmaceutical companies worked to produce freeze-dried plasma on a large scale, Cohn and his coworkers looked into derivatives or alternatives to plasma. What they discovered was a method to fractionate blood into its various components including albumin, a protein that was stable, transportable and a potent plasma expander. Albumin was administered in the battlefield often by military personnel referred to as “pharmacists' mates.” The basic components of Cohn's fractionation process are still used today to yield clotting factors, immune globulins and other plasma proteins.25

Pharmacy faculty members, staff members and students need to have this same can-do attitude with respect to health care reform initiatives. A successful program conducted at the local or state level may have national implications as exhibited by the recent debate of the generalizability of Massachusetts's state health care plan. Another example is the number of state associations, colleges/schools of pharmacy and boards of pharmacy that have become involved in drug take-back programs. So, when it comes to local and state health care policy development, pharmacy needs to work small but think big. Thinking big means including key pharmacy stakeholders such as schools/colleges of pharmacy, boards of pharmacy, and state pharmacy associations early in the policy development process. Consensus and support within the pharmacy profession on health care reform initiatives will increase the likelihood of support by other key stakeholders and decision makers.

As a profession we need to recognize and assign value when such health care initiatives are undertaken. For school/college of pharmacy faculty members, the value of external service should be recognized and rewarded in a manner similar to teaching and research activities. Even a cursory review of the pharmacy education literature suggests this is not the case. In contrast to the large number of articles pertaining to teaching and scholarship there is a paucity of publications concerning service; further, those publications that do concern service tend to focus more on academic (e.g., college and university committee work) or clinical service rather than external service activities. In one of the few papers discussing faculty service activities, Brazeau points out that service is often neglected in faculty evaluations, when instead the benefits of service as a form of scholarship should be articulated and valued in a manner similar to teaching and research.26 This seeming neglect of the importance of external service responsibilities by faculty members is somewhat ironic considering the importance that our profession has placed on service learning by our students. Student service participation and learning is required by ACPE standards27 and has been the subject of a number of articles in AJPE.9,28-31

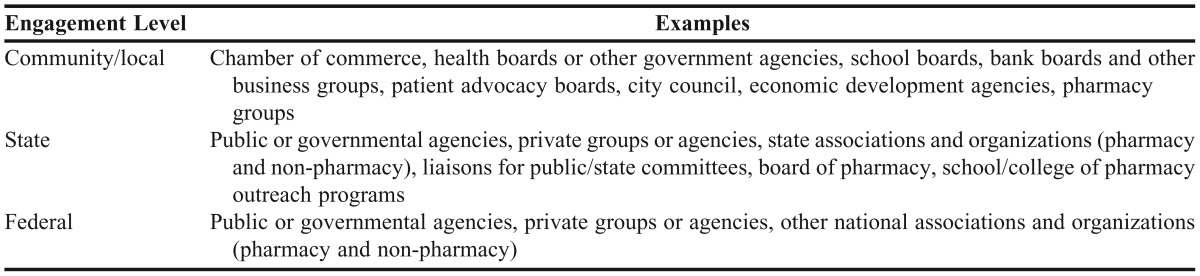

Along with the theme of working small but thinking big, there are a number of ways that faculty members can get involved in community and healthcare organizations including public agencies, private agencies, business and government (Table 4). Healthcare is local, thus a logical place to start involvement is with local groups, but this should not preclude concomitant regional or national involvement. Disaster preparedness is an example of an opportunity for involvement by school/college of pharmacy students, faculty and preceptors. Participants attest to the value of this type of involvement both in terms of the education and experience it provides to students and pharmacists and to the valuable community service effort that results from their participation.18

Table 4.

Opportunities for Faculty, Preceptor and Student Involvement in Healthcare Policy Discussions

Pharmacy associations and boards of pharmacy can assist in organizing and soliciting these opportunities and providing them to schools/colleges of pharmacy. Furthermore, pharmacists and students should use their contacts in communities to network and advocate for the inclusion of the pharmacist in the patient-centered provider team that delivers quality affordable care. Not all of these groups will necessarily discuss pharmacy-related issues during these meetings, but the discussions may lead to future discussions that pertain to pharmacy. Therefore, we should be challenging our students, faculty and preceptors to be involved in whatever opportunities are available and taking advantage of potential leadership opportunities when they arise. We must take the time to be at critical meetings where pharmacy has the potential to be a contributing partner or colleague.

Members of the Triad Working as Separate Entities. Each member of the triad may participate in a variety of strategies to optimally position pharmacists in health reform initiatives by engaging in state and local policy developments. Ideally, these strategies will incorporate the other members of the triad in local efforts to advocate for the expanded role of pharmacists in these initiatives. Several schools/colleges of pharmacy, pharmacy associations, and boards of pharmacy have already participated in the execution of these strategies:

• Policy Development/Advocacy: School/college-based pharmacy initiatives to increase involvement in policy development may include its incorporation into the curricula, education of faculty and students, utilization of alumni and friends, interprofessional education, and use of preceptors currently working in policy facilitating settings. Several schools/colleges of pharmacy have successfully offered courses in leadership and political advocacy.10-12 In one of these courses, lectures were given by leaders from the state pharmacy association and students were given the opportunity to attend a state pharmacy association meeting.11 These activities increased the students’ awareness of current issues and participation in advocacy efforts.

• Emergency Preparedness: Partnering with community providers and local public health entities creates opportunities for faculty and students to participate in emergency preparedness planning and exercises.18 This interaction allowed for the expansion of the pharmacist’s role into the emergency preparedness arena and education for both students and faculty members.

• Education of Preceptors and Faculty: The education of preceptors and faculty members may be achieved by facilitating and participating in continuing education sessions, statewide professional meetings, and grassroots efforts and subscribing to policy and advocacy listservs.

• Mentoring: The mentoring of students by alumni and friends, especially those in policy development, affords students the opportunity for exposure to the inner workings of policy development and networking opportunities necessary for the creation of health reform policies. One school ran an advertisement in the state pharmacy journal to seek alumni and friends to mentor students in the school’s online Pharm.D. program.16

• Preceptors and Interprofessional Education (IPE): IPE may lead to the advocation for pharmacy by exposing other professions to the skills pharmacists possess, thus revealing the value of pharmacists in patient-care settings. According to a study by Shrader et al.,32 pharmacy and medical students reported their knowledge about other healthcare professions increased during their participation in an interprofessional simulation. The recruitment of preceptors from boards of pharmacy and pharmacy associations affords student pharmacists the opportunity for experiences related to policy and its development.

State pharmacy association-based strategies are varied, but ultimately include ensuring the advancement and excellence in the pharmacy profession. Strategies to accomplish this include:

• the strategic and active utilization of executive teams, officers, and preceptors;

• exploration of the challenges and advantages of working with other state associations under one umbrella versus working as separate entities; and

• providing education and continuing professional development opportunities; examination of interprofessional practice issues; and assistance with identifying the potential “tables” for which pharmacy should consider and investigate for participation.

In a 2010 AACP report, the Argus Commission met with education associations of various disciplines involved in providing primary care services.33 The Argus Commission was charged with soliciting feedback pertaining to the pharmacist’s role in primary health care delivery. During the meeting, recommendations were created for the promotion of interprofessional education and ongoing input from the various disciplines concerning the incorporation of the necessary competencies for pharmacists to effectively participate in primary care services into accreditation standards, pharmacy curricula, and the national licensing examination.

The state pharmacy associations and boards of pharmacy can be instrumental in implementing strategies such as building collaborations with state entities to pursue grants (e.g., Centers for Disease Control Community Transformation Grants)34 assisting in the establishment and formation of relationships with state and local health departments, state legislative aides, senators, representatives, and lobbyists; and participation in interprofessional regulatory issues. Acquisition of community and state grants will allow the boards of pharmacy to demonstrate the abilities of pharmacists, which may lead to advocacy of policies that increase the presence of the pharmacists in health care reform as well as the needed evolution of state pharmacy acts. Listening and being an observer in state meetings regarding changes to the health care system will provide opportunities for pharmacy to provide input on how the profession can assist in statewide efforts (i.e., helping to manage medical costs in state Medicaid programs by effective medication management). Fostering relationships with various entities and joining forces with other professions will increase the influence of pharmacists in the political arena by contributing to the support of pharmacy-based initiatives.

To be most effective, the members of the triad should consider incorporating the other members into their individual strategies to foster policy development. One example of such efforts is the Texas Pharmacy Congress. The Congress consists of collaboration between all the members of the triad – schools/colleges of pharmacy, pharmacy associations, and the board of pharmacy. Its mission is “to facilitate discussion on professional, technological, legislative, and regulatory issues through exchange of views, interpretation, and analysis of matters of common interest to Texas pharmacists, Texas pharmacy organizations, and the constituencies they serve.”35 The discussions occurring in the triad relationship leads to proposals to pursue policies relevant to all triad members and ultimately the profession of pharmacy.

The Triad Working Together—A Collaborative Effort. There are numerous examples of how members of the triad have worked together to create new, advanced, and enhanced opportunities for pharmacists in health care and other related areas. Furthermore, the PAC identified other opportunities for the triad to collaborate to further the profession’s goal of advancing patient care.

Continuous Professional Development. Continuous professional development (CPD) is defined as “an ongoing self-directed, structured, outcomes-focused cycle of learning and personal development.”36,37 Along with obtaining Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) approved continuing education (CE) hours, CPD is currently the only other chosen method of pharmacist competency documentation in the United States (US). Within the profession of pharmacy, competency has mainly been documented through obtaining CE credits; however, within the past 10 years, there has been a movement to change the method for documenting and obtaining professional competency. Canada (Ontario), New Zealand, Australia and Great Britain currently use components of CPD that involve self-directed learning, competency documentation using the CPD cycle, and a professional portfolio to document evidence of learning.38 North Carolina is the only state in the US that allows pharmacists to choose to meet the competency component of licensure via either CPD or CE. There have been two published studies within the US that compare pharmacist learning in a CPD method versus CE.39,40 Movement toward the use of CPD as an accepted method of continuous competency in pharmacy has been relatively slow within the US.

The movement toward CPD comes in part from an Institute of Medicine (IOM) report that recommends all health professions boards require licensed health care professionals to intermittently validate their abilities to deliver patient care.41 While there are a few published studies concerning CPD, more studies are needed in this area to show its superiority over traditional CE as well as its ability to validate professional competency. The triad can recommend and execute pilot projects and studies through the legislature and can also work together to streamline these activities. Schools/colleges of pharmacy can and should play a major role in instigating this lifelong learning change and can do so through the use of student portfolios (as required in ACPE Standards 15 and 26)27 that require reflection and planning for continued development.

Showing documented competency will be important in the future of our profession, especially regarding expanded practice for pharmacists. Additionally, the triad can work together to develop a system by which pharmacists will earn the necessary credentials to be considered mid-level practitioners as well as to determine the types of training and/or certification which will allow for such practice.

Expansion of Pharmacist Scope of Practice. The pharmacy profession has been hindered because pharmacists are not considered primary health care providers and are not able (in most instances) to receive payment for direct patient care services. Pharmacy associations at the national level have collaborated and launched legislative initiatives that will allow direct patient care services of qualified pharmacists to be a covered benefit under the Medicare program6 While the American College of Clinical Pharmacy42 and other national pharmacy organizations may be leading this cause, it will take a huge effort by all pharmacists to make such changes occur. While leading the case for pharmacist practice expansion is of great importance, it is equally important to solicit legislative “buy-in” from other organizations of non-pharmacist health care professionals (e.g., physicians, nurses, etc.). Such efforts could also be directed by triad groups at the state level in an effort to form advocacy partnerships for legislative change.

State triads can help promote such legislation within states and serve as action arms of this national cause. Discussion concerning practice expansion and required legislative changes at the state level will be important and should begin with the triads. Triads can also lead research efforts to show the value of pharmacists in expanded practice roles.

Other current and potential areas of expansion of the pharmacist scope of practice could be:

• Tech-Check-Tech,43 checking of a technician’s order-filing accuracy by another technician rather than a pharmacist, being expanded to community pharmacy in an effort to further expand MTM and primary care to the retail practice setting

• Medication Therapy Management (MTM) expansion to include more disease states

• Roles of pharmacists in transitions of care

• Pharmacists practicing as mid-level practitioners with the ability to diagnose and treat acute disease (per pharmacy based clinics) with potential to operate under collaborative practice agreements.

Pharmacist Immunization Expansion. Currently, there is high variability by states in pharmacist immunization abilities. The widest source of variability occurs with state regulations regarding immunization of children and adolescents. While most states allow some form of pharmacist immunization, only thirteen states currently allow pharmacists to provide vaccinations for patients of any age.44 Sixteen states allow vaccinations for patients 18 years or older and 22 states allow vaccinations at differing age levels from 3 to 14 years.44 On the other hand, many states only allow pharmacists to administer influenza and pneumococcal immunizations. Additionally, not all health plans recognize pharmacists as immunizers, which further diminishes their ability to care for patients. Because legislation involving pharmacist immunization occurs at the state level, triads can play a key role in the ability of our profession to work together to expand access of immunizations to younger patients and expand our pharmacists’ immunizations.

In 2012, ASHP created a policy position which states (1) to standardize immunization authority and improve public health such that states grant pharmacists the authority to initiate and administer all adult and child immunizations through a universal protocol developed by state health authorities (2) to advocate that only pharmacists who have completed a training and certification program approved by state boards of pharmacy and meets the standards of the CDC, and (3) to advocate that state health authorities create a centralized database for recording administration of immunizations that is accessible to all health care providers.45 Although the role of the pharmacist as an immunizer is now accepted by the US public, there is still much work to be done in an effort to expand pharmacist immunization services to reach those patients who are at risk of preventable diseases.

Schools/colleges of pharmacy can lead immunization expansion by continuing to take a major role in training all student and licensed pharmacists to immunize patients and promote CE efforts to keep such training current with pharmacists. Additionally, faculty from schools and colleges of pharmacy can provide clinical information to educate our legislators and the public on how such an expansion of pharmacist efforts can benefit our public health system as well as educate additional advocacy leaders to support appropriate legislation and regulations allowing pharmacist immunization expansion. Academia can partner with such efforts by participating in discussion groups currently addressing expansion to support collaboration and activities as well as assist with research findings to support the case for growth of pharmacist immunization authority.

Emergency Preparedness. The pharmacist’s role in emergency preparedness is underutilized and not standardized, and there is not a clear vision of the role of a pharmacist during an emergency situation. Since emergency response occurs on the state level, triads of schools/colleges of pharmacy, state associations, and state boards of pharmacy should work together to determine the role of pharmacy practice on the frontline of such emergency situations and the training, legislation, pharmacist engagement and collaboration necessary to make such vision a reality. Additionally, as a profession, we must make the case to local and state health departments of the value that pharmacists have during emergency situations.

Michigan is one such state that has an organized pharmacy effort in emergency preparedness such that there is a designated Emergency Preparedness Pharmacist Coordinator for the state. The Michigan Pharmacists’ Association has such resources readily available on their website and offers the following information to pharmacists: online educational training, Incidental Command Systems Training, Basic Disaster Life Support Training, Volunteer Registry, and Experience Based Exercise Training.46

Additional areas of interest/training that are important and could utilize the state triad for coordination of pharmacists efforts along with those of other health providers are:

• Mass immunization

• Mass dispensing of emergency and maintenance medication

• Potassium iodide dispensing to those living close to nuclear power plants

• Establishing collaborative practice agreements with local health districts and pharmacy organizations

• Establishing a memorandum of understanding (MOU) between the local health district and pharmacy organizations

• Training opportunities for pharmacists

• Having a coordinated pharmacist effort in emergency preparedness and a clear vision for the role of the pharmacist during such emergencies.

Electing and Retaining Pharmacists in State Legislatures and in Key Advisory Committees. Prior to the November 2012 election, 46 Pharmacists were currently serving in state legislatures across the US and there were no pharmacist legislators in the US Congress.47 It is critical to the profession that the process of identifying, educating, and supporting pharmacists be supported at the state and national levels, and state triads should play a major role in this effort. With so many future changes in health care as well as practice expansion on the horizon, our profession must seek out pharmacist leaders and work together toward placing these into our state and national legislatures.

Likewise, having pharmacists placed on key state committees along with other health care professionals can provide the opportunity for pharmacy to be represented when discussion occur regarding patient care, reduction of health care costs, and serving underserved populations.

Creating Awareness of the Value of Pharmacists in Evolving Models of Patient Health Care . As health care continues to evolve and expand, pharmacy has an opportunity to demonstrate and communicate the value of pharmacists and their contribution to the health care team and desired patient health care outcomes. The passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act48 (ACA) in 2010 brought a renewed focus on improving healthcare access, quality, safety, and cost to the nation. Pharmacy has an opportunity to demonstrate and communicate the value of pharmacists and their contribution to the health care team and desirable patient health care outcomes. Since 2010, there have been many studies demonstrating the value of pharmacists contributions to team-based health care,33,49-51 including Patient-Centered Medical Homes,52 and Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs).53,54 ASHP adopted a policy regarding transitions of care in 2012 recognizing the following:

• continuity of patient care is a vital requirement in the appropriate use of medications,

• pharmacists must assume professional responsibility in care transitions for ensuring safe continuity of care as patients move from one setting to another,

• information systems are developed, optimized, and implemented that facilitate sharing of patient-care data across care settings and providers,

• payers and health systems provide sufficient resources to support effective transitions of care, and

• strategies are developed to address gaps in continuity of pharmacist patient care services.45

Many of these new patient health care models are being tested and evaluated at the state level to control the cost of health care while providing quality of care to patients. As individual states initiate and implement elements of the ACA and state health reform, expertise is needed in benefit design, care coordination, health insurance exchanges, health system capacity, insurance regulation and ACOs. States have started investigating the role in promoting ACOs, including developing the necessary data to demonstrate patient care and quality, designing and promoting new payment methods, developing accountability measures, identifying and promoting systems of care, and supporting a continuum of care and the medical home model.55 As state ACOs56 and other elements related to state health care reform continue to develop, there are numerous opportunities for the networks of and expertise within the triad to be involved. For example, ACOs within states may use pilot pharmacist-based clinics or pharmacist transitions of care specialists in pilot programs to demonstrate their effect on patient outcomes and insurance costs. It is imperative that members of the triad provide the names of individuals and groups that are willing to participate and lend expertise to the development and execution of such initiatives. The triad must utilize its external and internal networks to investigate opportunities to participate on state committees, comment on proposed legislation and participate in pilot programs and other associated programs.

Health Information Technology and Electronic Health Records. The triad can contribute to the improvement of patient medication use and lowering health care costs via Health Information Technology (HIT). The Pharmacy e-Health Information Technology Collaborative, comprised of national pharmacy associations including AACP and NASPA, provides a strategy to ensure that pharmacists and electronic health records (EHRs) are connected and guidance to integrate pharmacy HIT into the national HIT infrastructure.57 There are examples in several states where the impact of pharmacists has been enhanced through the optimization of HIT solutions utilizing members of the triad partners in that state:58

• Connecticut: a model was tested that utilized pharmacists and pharmacy-related HIT to support the primary care team.59 The program provided MTM services to Medicaid patients in order to improve care, medication use, and health outcomes. Nearly 80% of the 917 drug therapy programs that pharmacists identified were resolved and these pharmacists’ interventions resulted in an estimated annual savings of $1,123 per patient on medication claims.

• Minnesota: pharmacists at a small community pharmacy chain provide innovative patient care services and are contracted with a local health system to have access to the system’s local EHRs via secure Internet connection.60 Pharmacists in this pharmacy chain access information within the EHR to prepare for MTM visit with patients, communicate with physicians, order labs, and perform various other functions. Having access to patient information allows these pharmacists to provide a higher level of patient care.

There are several examples of demonstrations that can be implemented at the state level by the triad to encourage the inclusion of pharmacists in health information exchanges. This includes assuring appropriate medication use to fully optimize medication therapy, utilizing pharmacists’ training, knowledge, and experiences to reduce adverse events, including pharmacists in transition-of-care activities, and utilization of pharmacists’ medication expertise and accessibility to respond to public health needs (including emergency preparedness).58

Interprofessional Education/Curricular Considerations. The future of health care focuses on a patient centered medical team to solve problems and provide best practices in care. Interprofessional education is an important pedagogical approach for preparing health professions students to provide patient care in a collaborative team environment.61 Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice62 and team-based interprofessional competencies63 provide schools/colleges of pharmacy and their health professions counterparts with baseline information to institute curricular and experiential facets in health care professions training programs. While educational requirements for training in interprofessional education have recently been mandated by education standards, most of the current practitioners were trained in “silos” where collaboration in practice was not taught. Two main issues with interprofessional health professionals are how to model interprofessional collaboration to students when it does not currently exist at an optimal level in practice and how to prevent “turf wars” between the health professionals. These issues must be solved for health professions practitioners to optimally practice at future levels.

There are several large and smaller provide institutions in the US that are on the forefront of interprofessional education. Examples of interdisciplinary activities include everything from home visits with collaborative student groups to simulation exercises. The key to making the changes necessary for the advancement of our profession lies with schools/colleges of pharmacy and the relationships developed with other members of the triad, as they must take a leadership role with envisioning practice at an advanced level, training student pharmacists to practice at such a level that is not known today, and creating experiences throughout the training program that offer student pharmacists the chance to be involved in direct patient care. Interprofessional education and practice continues to be a fertile area for development, research, and assessment.

All of the strategic areas for making change begin and end with our schools/colleges of pharmacy and touch on each area mentioned within this section. Schools/colleges of pharmacy have a major role to plant the seeds of leadership within student pharmacists that extend within our profession as well as outside of it to our community. Placing pharmacists into leadership positions in our national, state, and community legislatures is key to expanding our practice.

Taking on the big challenges must first start with working together as schools/colleges of pharmacy. Triad off-shoot groups that focus on experiential education can be instrumental in solving problems with everything from planning experiential calendars that are in sync to creating student evaluation systems that are similar. The Joint Committee on Internship Programs (JCIP)64 is an off-shoot from the “triad” in Texas (Texas Pharmacy Congress) and is made up of two members from each of the Texas schools/colleges of pharmacy. The focus of this group is to work together in an effort to benefit the pharmacy students in Texas and to solve problems that arise from experiential rotations. Some of the accomplishments of this group are: all schools/colleges of pharmacy within the state operate on the same experiential (rotation) calendar and each have Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience (APPE) rotations that are six weeks in length, all schools/colleges of pharmacy have adopted very similar APPE rotation evaluation forms for student rotations, and all schools/colleges of pharmacy are in the process of adopting the same evaluation forms for case presentations, journal clubs, and other curricular areas. For a pharmacist to precept students who attend schools/colleges of pharmacy within the state of Texas, he or she must be a certified preceptor and obtain three hours of continuing education specifically toward preceptor development every year. JCIP is also charged with preceptor development activities and works together with the state board of pharmacy to certify preceptor continuing education activities. JCIP also works with the state associations to jointly host annual preceptor CPE activities at each of the state association meetings.65

As the scope of pharmacist practice continues to grow toward primary care, schools/colleges of pharmacy must continue to be on the forefront of this change and train student pharmacists so that they are skilled to take on expanded practice roles especially in the ambulatory care settings. Such training would include Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experiences (IPPEs), APPEs and residency training in primary care and disease state management. As MTM services grow, student pharmacists should graduate with certification and experiential training in this area. As triads work toward the legislative portion of pharmacy’s practice expansion, schools/colleges of pharmacy should work together with the other members of their triad to make sure that professional curricula precede such change.

AACP CALL FOR SUCCESSFUL PRACTICES

A Call for Successful Practices for school/college of pharmacy collaborations with state pharmacy association(s) and state boards of pharmacy66 was released to AACP membership in November 2012 using various mechanisms, including the AACP electronic newsletter and emails sent to the AACP Governance Councils and Special-Interest Group listservs. Numerous reminders were sent in December 2012 and January 2013.

There were 14 responses to this call, representing fourteen AACP member schools/colleges of pharmacy. These collaborations ranged from formal coalitions involving members of the triad to collaborations to expand the scope of pharmacy practice to research investigations involving important public health issues. Many of the collaborations involved all of the schools/colleges of pharmacy in the state, which is necessary for the continued evolution of pharmacy practice at the state-level. Overall, there are several important aspects that were described in developing and maintaining successful triad relationships, including:

• The work of the triad can be strengthened and expanded with additional group participation and input;

• When a unified, consistent voice is heard from the triad members at the legislative level, senators and representatives better understand and support the profession and its needs;

• Work with the strengths and expanded networks of the three triad partners;

• All perspectives and ideas of each triad partner should be heard and considered; and

• Respect, trust, and open communication within the triad partnership are essential.

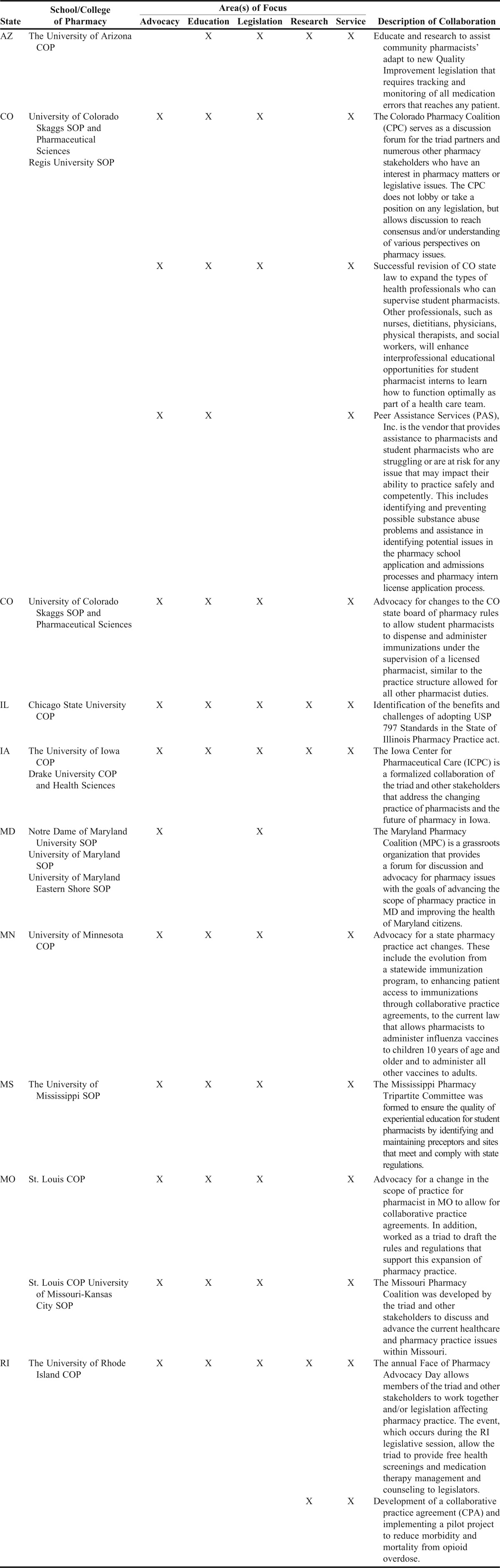

Descriptions of the successful practices submitted from this call is presented in Table 5 and the full description of the submissions can be found on the AACP website.66

Table 5.

Description of Submissions from the Call for Successful Practices Regarding Collaborations Between Schools/Colleges of Pharmacy, State Pharmacy Associations and State Boards of Pharmacy64

PROPOSED POLICY STATEMENTS, RECOMMENDATIONS, AND SUGGESTIONS

Policy Statements

The following policy statements were adopted by the AACP House of Delegates on July 17, 2013:

AACP supports the establishment of a recognized triad relationship between the schools/colleges of pharmacy, boards of pharmacy, and state pharmacy associations for the successful advancement of pharmacy practice and the role of pharmacists in interprofessional patient and healthcare settings. AACP encourages a culture of intellectual curiosity, risk-taking and entrepreneurship in schools /colleges of pharmacy. This would include, but is not limited to, member institutions modeling the behavior of creating agents of change and evolving practice models.

AACP supports the acknowledgement of the importance of the service contributions made by faculty and staff by assigning significant credit in the evaluation process. AACP recognizes the importance of everyone contributing to their community to affect change.

Recommendations

AACP should develop an institute addressing entrepreneurship, intellectual curiosity, creating agents of change, and visionary aspects to incorporate in schools/colleges of pharmacy curricula and other activities.

AACP should explore additional mechanisms for evaluating (assessing), validating scholarship of service, which includes the effort and engagement of faculty and staff in communities.

Suggestions

Schools and colleges of pharmacy should be dedicated and ardent in establishing a recognized triad relationship with their state pharmacy association(s) and state board of pharmacy.

Schools and colleges of pharmacy must take a leadership role in bringing their state pharmacy associations together in addressing pertinent issues in pharmacy and health care.

Schools and colleges of pharmacy must identify and participate in initiatives and meetings being held at the state and local levels that involve health care and health transition models for opportunities to be involved.

Schools and colleges of pharmacy should work in concert with state pharmacy association(s) and state board(s) of pharmacy to identify and prioritize initiatives that the pharmacy profession should be represented at as well as identify those issues that need to be developed and led by the pharmacy profession.

The deans of schools and colleges of pharmacy within each state and/or region should work together for issues involving higher education and health care.

Summary and Conclusion

The Professional Affairs Committee identified successful practices in the development and maintenance of effective relationships between state boards of pharmacy, state pharmacy organizations and schools/colleges of pharmacy. Key attributes predictive of success were that all three organizational members of the triad (board of pharmacy, pharmacy associations, schools/colleges of pharmacy):

• Communicate openly in a trusted manner.

• Actively engage with the other two triad entities to understand constraints, challenges and opportunities.

• Work collaboratively toward a shared vision of an advanced model of pharmacist delivered patient care.

Additionally, the committee investigated how the triad, comprised of schools/colleges of pharmacy, state pharmacy associations, and state boards of pharmacy can influence state and local policy development to optimally position pharmacists in health reform initiatives. Three strategies were identified that achieve this impact: (1) individual faculty members working to advance pharmacy practice, (2) triad members influencing the practice as separate entities, and (3) triad members creating enhanced opportunities for pharmacists to care for patients. It was encouraging that so many examples of successful practices were identified, as described in this report.

In conclusion, the call to action for the Academy, to be present and active at “tables of influence” that will enhance the profession and improve patient care, is to:

• Promote the development of linkages between the recognized triad (pharmacy associations, boards of pharmacy, schools/colleges of pharmacy), while embracing a shared vision of advancing the pharmacist’s role in patient care.

• Commit to effective and nimble relationships with boards of pharmacy and state pharmacy associations.

• Capitalize on the strengths of the individual organizations to create a synergistic force.

• Embrace and recognize the contributions of faculty members through leadership in and involvement with the boards of pharmacy and the pharmacy associations to advance the practice by “being at the right table.”

REFERENCES

- 1.Bootman JL. Transforming healthcare. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(7):Article 122. doi: 10.5688/ajpe767122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins J. Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap…and Others Don’t. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taleb N. Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder. New York, NY: Random House, Inc.; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotter International. The 8-step process for leading change. http://www.kotterinternational.com/our-principles/changesteps/changesteps. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 5.Barker D. The scholarship of engagement: a taxonomy of five emerging practices. http://www.wartburg.edu/cce/cce/scholarship%20of%20sl/The%20Scholarship%20of%20Engagement.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 6.Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners. Future vision of pharmacy practice. November 10, 2004. http://www.amcp.org/uploadedFiles/Horizontal_Navigation/Publications/Professional_Practice_Advisories/JCPP%20Vision%20for%20Pharmacy%20Practice.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 7.Listening and Critical Thinking. http://highered.mcgraw-hill.com/sites/dl/free/0073385018/537865/pearson3_sample_ch05.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 8.Fenson S. Want to be more effective? Learn to listen. http://www.inc.com/articles/2000/03/17491.html. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 9.Philips C, Chesnut R, Haack S, et al. Garnering widespread involvement in preparing for accreditation under ACPE Standards 2007. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(2):Article 30. doi: 10.5688/aj740230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blake EW, Powell PH. A pharmacy political advocacy elective course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(7):Article 137. doi: 10.5688/ajpe757137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pace AC, Flowers SK. Students' perception of professional advocacy following a political advocacy course. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2012;4(1):34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyle CJ, Beardsley RS, Hayes M. Effective leadership and advocacy: amplifying professional citizenship. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(3):Article 63. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chesnut R, McDonough R, Moulton J. Student leadership conferences: a collaborative approach framework for state associations and colleges of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 1997;61:Article 98S. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wuller WR, Luer MS. A sequence of introductory pharmacy practice experiences to address the new standards for experiential learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(4):Article 73. doi: 10.5688/aj720473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duke LJ, Unterwagner WL, Byrd DC. Establishment of a multi-state experiential pharmacy program consortium. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(3):Article 62. doi: 10.5688/aj720362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alsharif NZ, Schwartz AH, Malone PM, Jensen G, Chapman T, Winters A. Educational mentor program in a web-based doctor of pharmacy degree pathway. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(2):Article 31. doi: 10.5688/aj700231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siracuse MV, Schondelmeyer SW, Hadsall RS, Schommer JC. Assessing career aspirations of pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(3):Article 75. doi: 10.5688/aj720350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woodard LJ, Bray BS, Williams D, Terriff CM. Call to action: integrating student pharmacists, faculty, and pharmacy practitioners into emergency preparedness and response. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2010;50(2):158–164. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2010.09187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terriff CM, Newton S. Pharmacist role in emergency preparedness. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48(6):702–708. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.00543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patterson BJ, Chang EH, Witry MJ, Garza OW, Trewet CB. Pilot evaluation of a continuing professional development tool for developing leadership skills. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2013;9(2):222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dopp AL, Moulton JR, Rouse MJ, Trewet CB. A five-state continuing professional development pilot program for practicing pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(2):Article 28. doi: 10.5688/aj740228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez deBittner, Adams AJ, Burns AL, et al. Report of the 2010-2011 Professional Affairs Committee: effective partnership to implement pharmacists’ services in team-based, patient-centered healthcare. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(10):Article S11. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7510S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving Patient and Health System Outcomes through Advanced Pharmacy Practice. A Report to the U.S. Surgeon General. Office of the Chief Pharmacist. U.S. Public Health Service; December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. District composition. http://www.nabp.net/about/district-composition/. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 25.Starr D. Blood. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc; 2002. Blood cracks like oil; pp. 101–121. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brazeau GA. Revisiting faculty service roles – is “faculty service” a victim of the middle child syndrome? Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3):Article 85. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. https://dev.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/FinalS2007Guidelines2.0.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 28.Nickman NA. (Re)learning to care: use of service-learning as an early professionalization experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 1998;62(Winter):380–387. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barner JC. Implementing service-learning in the pharmacy curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64(Fall):260–265. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peters SJ, MacKinnon JE. Introductory practice and service learning experiences in US pharmacy curricula. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(1):Article 27. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kearney KR. Service-learning in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(1):Article26. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shrader S, McRae L, King WM, Kern D. A stimulated interprofessional rounding experience in a clinical assessment course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(4):Article 61. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Draugalis JR, Beck DE, Raehl CL, Speedie MK, Yanchick VA, Maine LL. Call to action: expansion of pharmacy primary care services in a reformed health system. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(10):Article S4. doi: 10.5688/aj7410s4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community transformation grants (CTG) http://www.cdc.gov/communitytransformation/. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 35.University of Texas at Austin College of Pharmacy. Texas Pharmacy Congress: working together for Texas pharmacists. http://www.utexas.edu/pharmacy/faculty_staff/tpc.html. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 36.Continuing Professional Development—the IPD Policy. London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development; 1997. p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Continuing professional development. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/ceproviders/CPD.asp. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 38.Driesen A, Verbeke K, Simoens S, Laekeman G. International trends in lifelong learning for pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(3):Article 52. doi: 10.5688/aj710352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dopp AL, Moulton JR, Rouse MJ, Trewet CB. A five-state continuing professional development pilot for practicing pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(2):Article 28. doi: 10.5688/aj740228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McConnell KJ, Newlon CL, Delate T. The impact of continuing professional development versus traditional continuing pharmacy education on pharmacy practice. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(10):1585–1595. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greiner AC, Knebel E, editors. Institute of Medicine Committee on the Health Professions Education Summit. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.American College of Clinical Pharmacy. AACP launches new initiative to seek provider status for clinical pharmacists working in all practice settings. http://www.accp.com/report/?iss=1212&art=1. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 43.Adams AJ, Martin SJ, Stolpe SF. “Tech-check-tech”: a review of the evidence on its safety and benefits. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68(19):1824–1833. doi: 10.2146/ajhp110022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pharmacist-Provided Immunization Compensation and Recognition. White Paper Summarizing APhA/AMCP Stakeholder Meeting. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2011;51(6):704–712. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2011.11544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.ASHP Policy Positions 1982-2012. http://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/BestPractices/policypositions2012.aspx. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 46.Emergency preparedness. Michigan Pharmacists Association Web site. http://www.michiganpharmacists.org/resources/emergency/. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 47.Whitmer C. Pharmacists in politics. Pharm Today. September 1, 2012. www.pharmacist.com/pharmacists-politics-0. Accessed January 14, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 48. H.R. 3590-111th Congress: Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; 2010.

- 49.Chisholm-Burns MA, Kim Lee J, Spivey CA, Slack M, Herrier RN. US pharmacists effect as team members on patient care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Care. 2010;48(10):923–933. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e57962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Oliveira DR, Brummel AR, Miller DB. Medication therapy management: 10 years of experience in a large integrated health care system. J Manag Care Pharm. 2010;16(3):185–195. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.3.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith MA, Bates DW, Bodenheimer T, Cleary PD. Why pharmacists belong in the medical home. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):906–913. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. Special Interest Group: medication management. http://www.pcpcc.net/medication-management. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 53.Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. Pharmacists as vital members of accountable care organizations: illustrating the important role that pharmacists play on health care teams. http://www.amcp.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=9728. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 54.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP Policy Analysis: Pharmacists’ Role in Accountable Care Organizations. http://pharmacy.about.com/gi/o.htm?zi=1/XJ&zTi=1&sdn=pharmacy&cdn=b2b&tm=136&gps=176_9_805_488&f=00&tt=8&bt=0&bts=0&zu=http%3A//www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Advocacy/PolicyAlert/ACO-Policy-Analysis.aspx. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 55.Purington K, Gauthier A, Patel S, Miller C. On the Road to Better Value: State Roles in Promoting Accountable Care Organizations. The Commonwealth Fund and the National Academy for State Health Policy. February 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 56.National Academy for State Health Policy. State ‘accountable care’ activity map. http://nashp.org/state-accountable-care-activity-map. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 57.Pharmacy e-Health Information Technology Collaborative. The Roadmap for Pharmacy Health Information Technology Integration in U.S. Health Care. http://www.pharmacyhit.org/pdfs/11-392_RoadMapFinal_singlepages.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pharmacy e-Health Information Technology Collaborative. Improving medication use and lowering health care costs using pharmacists and health information technology (HIT) http://naspa.us/documents/hit/brochure.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 59.Smith M, Giuliano MR, Starkowski MP. Connecticut: improving patient medication management in primary care. Health Aff. 2011;30(4):646–654. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Egervary A. MTM, Minnesota Style. Pharm Today. March 2010. http://apha.imirus.com/Mpowered/book/vpt16/i3/p36. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 61.Buring SM, Bhushan A, Broeseker A, Conway S, et al. Interprofessional education: definitions, student competencies, and guidelines for implementation. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(4):Article 59. doi: 10.5688/aj730459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core Competencies for Interpfoessional Collaborative Practice: Report of an Expert Panel. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Educational Collaborative; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Team-based competencies: building a shared foundation for education and clinical practice. http://www.aacp.org/resources/education/Documents/IPEReport_110503.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 64.Texas Joint Committee on Internship Programs Calendar. http://www.calendarwiz.com/calendars/calendar.php?crd=txjcipcalendar&. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 65.Approved preceptor education in Texas. http://www.utexas.edu/pharmacy/general/experiential/practitioner/appcourses.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2013.

- 66.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Successful practices in academic pharmacy. http://www.aacp.org/resources/education/Pages/SuccessfulPracticesinPharmaceuticalEducation.aspx. Accessed January 14, 2013.