Abstract

Introduction

A new treatment plan was implemented at Skåne University Hospital, on economic grounds, for children requiring recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) treatment. This involved switching patients from treatment with originator rhGHs to treatment with a biosimilar rhGH, somatropin (Omnitrope®), using a Dialogue Teamwork approach. The feasibility of using this approach to implement the switch of treatment was assessed, as well as the impact of the switch on treatment efficacy and cost of therapy.

Methods

As part of the Dialogue Teamwork approach, patients/parents received several opportunities for dialogue and sources of information, including discussions with the Head of Department, the responsible physician and a specialized endocrinology nurse. Height and height standard deviation score (HSDS) data were plotted for each individual patient (N = 98). A modeling approach was also used, to predict growth after switching to biosimilar rhGH; the predictions were then compared to the actual observed height after the switch. Costs to the clinic of rhGH therapy were calculated between May–August 2009 and May–August 2012.

Results

Of the 102 patients offered the switch, 98 accepted. Height and HSDS data indicated there was no negative impact on growth velocity after the switch to biosimilar rhGH. Modeling demonstrated that observed growth following the switch was consistent with predicted growth based on data before patients were switched. There were no reports of serious or unexpected adverse drug reactions following the switch to biosimilar rhGH. Following the switch, the cost to the clinic of rhGH treatment decreased from approximately 6 million SEK (May–August 2009) to approximately 4 million SEK (May–August 2012). This corresponds to an annual saving of 6 million SEK (€650,000).

Conclusion

Patients were successfully switched from originator to biosimilar rhGH (somatropin), with no negative impact on growth, and no serious or unexpected adverse drug reactions. The switch from originator to biosimilar rhGH is associated with substantial cost savings.

Keywords: Biosimilar, Cost savings, Growth disturbances, Human growth hormone, Omnitrope, Pediatric, Switch

Introduction

Without intervention, even wealthy countries face a crisis in healthcare spending; escalating costs are driven, at least in part, by novel, high-cost biopharmaceuticals [1]. Sales of biopharmaceuticals currently amount to almost $70 billion in the US, and €60 billion in Europe [2, 3]. The expiration of patents for biopharmaceuticals allows pharmaceutical companies to develop and produce similar biological medicinal products, also known as biosimilars. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) defines biosimilars as medicines that are similar to a biological medicine that has already been approved [4]. ‘Biosimilar’ is therefore a regulatory term used to indicate a biopharmaceutical product that has been approved under a well-defined regulatory pathway. The principal reason for using biosimilar drugs is for cost saving [1]; the uptake of biosimilars will therefore depend on the degree to which cost savings are required by healthcare systems and the absolute savings that could be gained by switching from original drugs.

A number of recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) products are available for the treatment of pediatric growth disturbances, including somatropin (Omnitrope®, Sandoz, Kundl, Austria). Omnitrope® is a rhGH approved by the EMA in 2006; approval was granted via the biosimilar regulatory pathway, on the basis of comparable quality, safety, and efficacy to the reference product (Genotropin®, Pfizer, Sollentuna, Sweden) [5]. Omnitrope® is also approved in other territories including Australia, Canada, the Middle East, the Far East (e.g., Japan, Taiwan), Central and South America (e.g., Mexico, Argentina, Brazil), and has received positive opinion from the UK’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) [6]. In addition, the product is approved for use in the United States (US); due to the lack of a formal biosimilar regulatory pathway, Omnitrope® was approved in the US following a New Drug Application via the pathway described by Section 505(b)2 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. Omnitrope® is licensed for use to treat growth disturbances in the following pediatric indications; growth hormone deficiency (GHD), Turner Syndrome, chronic renal insufficiency, children born small for gestational age, and Prader–Willi Syndrome [7]. It is also approved for the treatment of adult GHD and, in the US, idiopathic short stature.

The availability of biosimilar medicines has potentially substantial benefits for healthcare providers and patients in terms of reducing drug expenditure and possibly increasing patient access to treatments [8]. In Sweden, almost all health care is publicly funded via taxes, and there is pressure to contain healthcare expenditure. Skåne University Hospital (Malmoe, Sweden) is responsible medically and financially for the prescription of rhGH treatment to children at six hospitals in the Skåne region. In June 2009, a new treatment plan was implemented, on economic grounds, for children requiring rhGH treatment. This involved switching patients from existing treatment with originator rhGHs to treatment with biosimilar rhGH (Omnitrope®), using a Dialogue Teamwork approach. Dialogue Teamwork can be used to implement changes in health care without adopting a top-down approach, and its main component is interprofessional education [9]. This manuscript describes the implementation of this new treatment plan, and its impact in terms of treatment efficacy, safety, and cost savings.

Methods

Implementation of the Switch to Biosimilar rhGH

A total of 120 patients were considered for a switch to treatment with biosimilar rhGH; 102 were finally offered a switch using a Dialogue Teamwork approach. Patients not offered the switch had an expected duration of further rhGH treatment <6 months (n = 16), or a history of allergic reaction to other growth hormone preparations (n = 2). All patients (or their parents) offered the switch were provided with the following information or support to aid their decision as part of the Dialogue Teamwork approach:

a letter from the Head of Department of Pediatrics explaining the economic rationale for the switch;

the opportunity to discuss the medical aspects of the switch with the physician responsible for patient care;

further dialogue with the Head of Department if patients did not accept the switch after the discussion with the responsible physician;

information on the biosimilar rhGH (somatropin) from the EMA;

a visit to a specialized endocrinology nurse to receive instructions on how to perform the switch (e.g., use the new device) and to ask any questions concerning the switch;

the telephone number of the specialized endocrinology nurse to contact for advice.

The patients were familiar with the physician responsible for patient care and the specialized endocrinology nurse, the team that started the previous treatment with rhGH. Patients who still did not accept the switch were offered the opportunity to continue with the originator product by contributing the difference in cost of treatment between the originator and biosimilar rhGH. All treatments, visits, tests, and assessments were performed as part of routine clinical practice; no additional or specific visits, tests, or assessments were required as part of the study (except for the additional visit to the specialized nurse for patients/carers to receive instructions on use of the new device).

Ethics Approval

In Sweden, approval from an ethics committee is not required if the following criteria apply: the work involved is essentially a check on the quality of the clinical work in a hospital; the data analyzed is collected as part of the normal clinical management of patients; and the data collected are analyzed anonymously. The work fulfilled all three of these criteria. The findings reported here were obtained as part of the normal clinical management of the patients, which was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice. All patients (or their parents) consented verbally to the change in clinical management, from treatment with originator rhGH to treatment with a biosimilar rhGH, following provision of relevant information and discussions with the clinical team. This verbal consent was documented in the hospital records. Patients/parents were informed that the change of treatment was to be monitored by assessment of their growth data.

Efficacy Assessments and Modeling Approach

Height and height standard deviation score (HSDS) data were plotted for each individual patient. In addition, a modeling approach was used for the statistical assessment of switchability to biosimilar rhGH. A logarithmic model for height had already been developed [10]. This model was used to fit the growth data before switching to biosimilar rhGH. More precisely, the fitted model was as follows:

|

where h ij is the height measured on child i and occasion j, t ij is the time from first visit in years, age0i is the initial age, the αs are fixed-effect parameters, the as and ε are random (normal) terms.

This model was used to predict the individual growth trajectories after switching to biosimilar rhGH treatment; the predictions were then compared to the actual observed height after the switch to biosimilar rhGH.

Results

Of the 102 patients who were offered the switch to biosimilar rhGH, 98 decided to accept. Five patients took up the option of further dialogue with the Head of Department. No patient took up the option of remaining on originator rhGH by contributing to the cost of therapy. The remaining four patients were allowed to continue with their original treatment, without contributing to the cost of therapy, by special arrangement with the Head of Department; the reasons for these arrangements were lifestyle considerations in two cases and psychological considerations in the other two cases. Characteristics of the patients who accepted the switch are shown in Table 1; the primary growth disturbance among these patients was GHD (n = 40; 41%). Six patients who switched to biosimilar rhGH reverted to their originator treatment; for three of these patients no height measurements are available for the period they were receiving biosimilar rhGH.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Patients who agreed to switch (n) | 98 |

| Male/female (n) | 52/46 |

| Age range (years) | 1–15 |

| Primary growth disturbance (n)a | |

| GHD | 40 |

| Turner syndrome | 9 |

| Prader–Willi syndrome | 6 |

| Small for gestational age | 11 |

| Other | 36 |

aFour patients had dual diagnosis

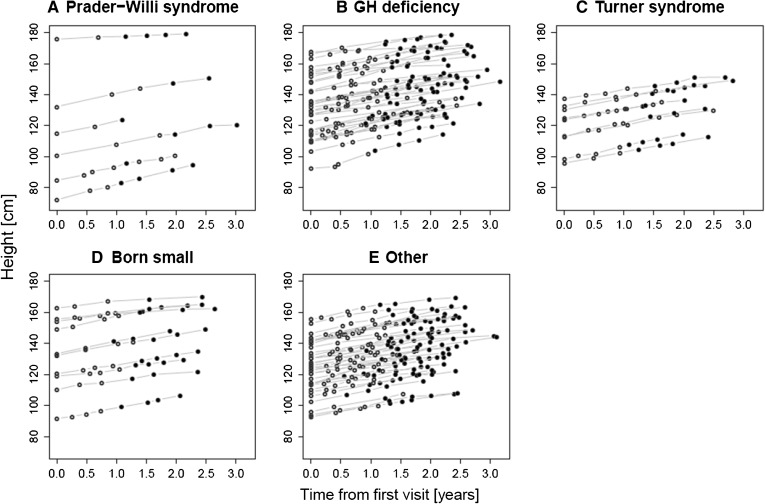

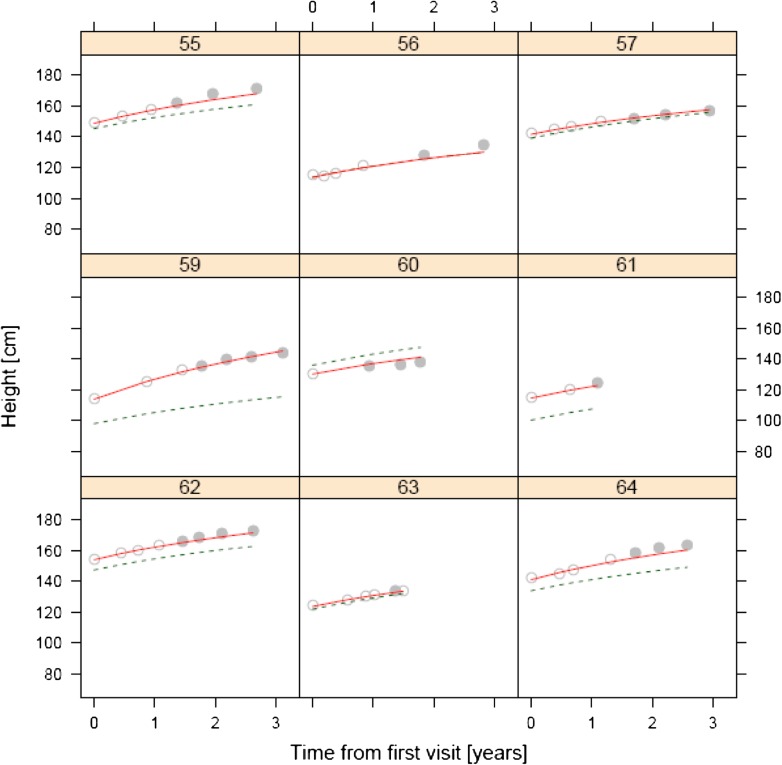

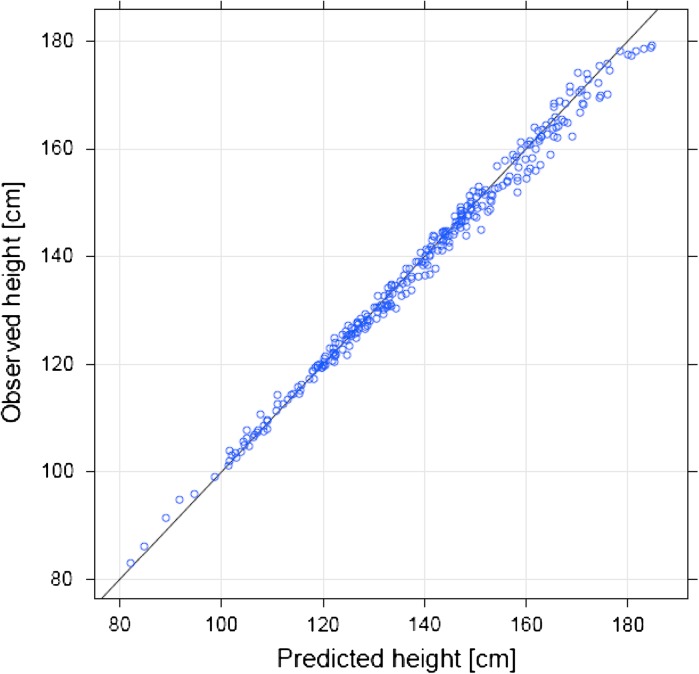

Height and HSDS data indicate no impact on growth velocity after patients were switched to treatment with biosimilar rhGH (Fig. 1). Similarly, analysis of height data suggests no impact of the switch in each of the different growth disturbances (Fig. 2). The modeling approach described earlier was used to predict individual growth trajectories after switching treatments (Fig. 3). The model was then used to compare the observed and predicted growth following the switch to biosimilar rhGH (Fig. 4); all data points lie close to the identity line (R 2 = 0.992, calculated between the predicted and observed values), demonstrating that the observed growth following the switch was consistent with predicted growth based on data before patients were switched. The standard deviation of differences between predicted and observed values was 1.9 cm; that is, 90% of the predicted values are expected to lie within 3 cm of the values actually observed (assuming normal distribution of the differences).

Fig. 1.

Growth data before and after switching to biosimilar recombinant human growth hormone. a Height by time from first visit; b height standard deviation score (SDS) by time from first visit. Open circle originator rhGH, filled circle biosimilar rhGH

Fig. 2.

Height data before and after switching to biosimilar recombinant human growth hormone in patients with different growth disturbances a Prader–Willi syndrome, b growth hormone deficiency, c Turner syndrome, d born small for gestational age, e other. Open circle originator rhGH, filled circle biosimilar rhGH

Fig. 3.

Illustration of the modeling approach to predict growth trajectories after switch to biosimilar recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH). The figure illustrates growth trajectories for nine sample patients. The model was fitted to originator rhGH and used to predict growth trajectories after switch to biosimilar rhGH. The solid lines represent the predicted growth trajectory of each individual. The dashed line represents the predicted growth trajectory of the typical individual in the dataset. Open circle originator rhGH, filled circle biosimilar rhGH

Fig. 4.

Assessment of observed versus predicted height following the switch to recombinant human growth hormone. The solid line is the identity line (i.e., points lying on this line have the same predicted and observed values of height)

There were no reports of serious or unexpected adverse drug reactions (ADRs) following the switch to biosimilar rhGH. A total of 19 ADRs (in 18 patients) were reported in the 12 months following the switch; 18 patients experienced pain at injection site (6 patients switched back to their originator rhGH preparation, 12 initially reported pain on injection but continued with biosimilar treatment following provision of advice and education on injection technique by a specialized endocrinology nurse), and one patient also experienced pitting edema. Of the 12 patients who experienced injection-site pain but continued with biosimilar treatment, 3 required an extra visit to the responsible physician or specialized nurse, and 10 required extra phone contact with the physician/nurse.

In the period May to August 2009, the cost to the clinic of rhGH therapy was approximately 6 million SEK; by the period May to August 2012, the cost to the clinic of rhGH had decreased to approximately 4 million SEK (Fig. 5). This provides an annual saving of 6 million SEK (€650,000).

Fig. 5.

Costs to the clinic of growth hormone therapy following the switch from originator to biosimilar recombinant human growth hormone (switch occurred in T2 2009)

Discussion

This study indicates that Dialogue Teamwork can be successfully used to implement a switch from originator to biosimilar rhGH in children with growth disturbances. The switch to biosimilar rhGH had no impact on the children’s growth and at the same time provided substantial cost savings. No serious or unexpected ADRs were reported following the switch to biosimilar rhGH. As expected, injection-site pain was the most commonly reported ADR. The number of patients reporting this ADR may be explained, at least in part, by the fact that switching to a different rhGH product also involves the use of a new injection device. Consequently, patients must learn, and get used to, a different injection technique. Reinforcing this point, most patients who reported injection-site pain initially were able to continue with their treatment following advice on injection technique from an endocrine nurse.

The incentive for implementing the switch from originator to biosimilar rhGH was financial, and all money saved was retained by the clinic to spend elsewhere rather than being put back into the regional healthcare budget. An important factor in implementing the switch was ensuring patient adherence to therapy. Interventions to improve medical adherence typically focus on the motivation or attitudes of the individual patient or family [11]. However, a systematic review concluded that these approaches result in only modest improvements [12]. The interaction between the patient/family and the team of healthcare professionals was assessed using systematic techniques in order to identify and remove potential barriers to the switch from originator to biosimilar rhGH [13–15]. The focus of this study was then to change, through interprofessional education [9], the way the healthcare professionals collaborated in order to facilitate the patient/family in adapting to the switch.

Previous attempts in Sweden to enforce a similar treatment switch have failed, largely because of protests from patients and their families that resulted in unfavorable media coverage. The Dialogue Teamwork approach employed enables changes in health care to be implemented through dialogue with, and involvement of, the patient/family and without the need for top-down mandates. Based on this study it is hypothesized that there are four critical elements to the success of such an approach in driving a change in the interactions between health professionals: (1) providing patients with clear information about the reasons for the change; (2) allowing individual patients/carers sufficient opportunities to discuss the change with the different healthcare professionals involved; (3) a joint team approach that avoids mixed messages from the different healthcare professionals involved; (4) providing patients with the reassurance of personal support throughout the change.

There is little published information on the impact of switching between GH products. Studies that are available have concentrated on switching between originator products, and assessed physician attitudes or the potential additional administration burden on clinics [16, 17]. In another study, using data from clinical trials, it was concluded that switching from originator to biosimilar rhGH had no impact on the efficacy and safety of treatment in children with GHD [10]. The data are consistent with, and extend those, from this previous study; ours is the first study to demonstrate no impact on growth trajectory when switching rhGH products in real-life clinical practice.

This study indicates the substantial savings that can be achieved by switching from originator to biosimilar rhGH, with costs to the clinic of rhGH therapy decreasing by approximately one-third between the periods May–August 2009 and May–August 2012. It is possible that these data underestimate the savings that are available by switching to biosimilar rhGH, since the overall cost of therapy also includes patients who switched back to originator rhGH. Data from the University College London Hospitals NHS Trust also indicate the substantial cost savings possible when switching all patients in a single center from originator rhGH to biosimilar rhGH, with annual savings estimated as in excess of £200,000 [18].

Conclusion

Dialogue Teamwork can be used to successfully switch patients from originator to biosimilar rhGH therapy (somatropin), with no negative impact on the patients’ growth, and no serious or unexpected ADRs. This strategy is associated with substantial cost savings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Johan Svensson and Carina Persson for their contribution to implementing the new treatment plan. Medical writing assistance in the preparation of this paper was provided by Tony Reardon of Spirit Medical Communications Ltd, and funded by Sandoz International GmbH. Article publication charges were also funded by Sandoz International GmBH. Dr. C.-E. Flodmark is the guarantor for this article, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Conflict of interest

Carl-Erik Flodmark has acted as a consultant to Sandoz, but received no financial reimbursement for conducting this work described in this paper. Heike Woehling is an employee of HEXAL AG/Sandoz. Katarina Lilja and Kajsa Järvholm have declared no conflicts of interest.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.Cornes P. The economic pressures for biosimilar drug use in cancer medicine. Target Oncol. 2012;7:S57–S67. doi: 10.1007/s11523-011-0196-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirsch BR, Lyman GH. Biosimilars: are they ready for primetime in the United States? J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011;9:934–942. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2011.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Covic A, Cannata-Andia J, Cancarini G, et al. Biosimilars and biopharmaceuticals: what the nephrologists need to know—a position paper by the ERA-EDTA Council. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:3731–3737. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roger SD. Biosimilars: current status and future directions. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:1011–1018. doi: 10.1517/14712591003796553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Omnitrope® European Public Assessment Report 2008. Available at: www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Scientific_Discussion/human/000607/WC500043692.pdf. Accessed 3 Nov 2011.

- 6.UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Human growth hormone (somatropin) for the treatment of growth failure in children. May 2010. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/12992/48715/48715.pdf. Accessed 2 Oct 2012.

- 7.Omnitrope® Summary of Product Characteristics 2008. Available at: www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000607/WC500043695.pdf. Accessed 3 Nov 2011.

- 8.Aapro M, Cornes P. Biosimilars in oncology: emerging and future benefits. GaBI J. 2013 (in press).

- 9.Reeves S, Tassone M, Parker K, Wagner SJ, Simmons B. Interprofessional education: an overview of key developments in the past three decades. Work. 2012;41:233–245. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romer T, Zabransky M, Walczak M, Szalecki M, Balser S. Effect of switching recombinant human growth hormone: comparative analysis of phase 3 clinical data. Biol Ther. 2011;1:005. doi: 10.1007/s13554-011-0004-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russell CL, Ruppar TM, Matteson M. Improving medication adherence: moving from intention and motivation to a personal systems approach. Nurs Clin N Am. 2011;46:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008; CD000011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Nowicka P, Flodmark CE. Family therapy as a model for treating childhood obesity: useful tools for clinicians. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;16:129–145. doi: 10.1177/1359104509355020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Shazer S. Keys to solution in brief therapy. New York: Norton; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minuchin S, Fishman C. Family therapy techniques. 1. Cambridge: Harvard University; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson WW, Frear RS. Physician attitudes toward human growth hormone products. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:51–56. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/56.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grimberg A, Feudtner C, Gordon CM. Consequences of brand switches during the course of pediatric growth hormone treatment. Endo Pract. 2012;18:307–316. doi: 10.4158/EP11217.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thakrar K, Bodalia P, Grosso A. Assessing the efficacy and safety of Omnitrope. Br J Clin Pharm. 2010;2:298–301. [Google Scholar]