Abstract

Introduction

Recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) is effective and safe when used to treat growth hormone deficiency (GHD) in children. However, it has been suggested that switching between different types of rhGH can have a detrimental effect on patients.

Methods

The current analysis assessed the efficacy and safety of rhGH in children who received continuous Omnitrope® (Sandoz GmbH, Kundl, Austria) therapy either with lyophilized powder for solution or ready-to-use solution, with children who received 9 months of treatment with Genotropin® (Pfizer Limited, Sandwich, UK) followed by Omnitrope solution thereafter. Changes to height, height SD score (SDS), height velocity SDS, insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) levels, and IGF binding protein (IGFBP-3) levels were assessed using data from three trials.

Results

Baseline demographics of the three study groups were similar. Over an 18-month period there were no observable differences between the three groups with respect to height, height SDS, height velocity SDS, IGF-1 levels, and IGFBP-3 levels. This result was corroborated by the model data, whereby most data points for Omnitrope-treated children fell within the defined limits of the prediction model based on Genotropin data. Few adverse drug reactions (ADRs) occurred.

Conclusions

Switching from Genotropin to Omnitrope solution has no impact on efficacy or safety in children with GHD, and the various rhGH preparations are well tolerated.

Keywords: children, efficacy, genotropin, growth hormone deficiency (GHD), immunogenicity, Omnitrope, recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH), safety, switching

Introduction

Growth hormone deficiency (GHD), which occurs when the pituitary gland produces insufficient growth hormone (GH) for adequate growth and development, can arise from a plethora of pathologies, although the cause in individual patients often remains obscure.1 This pathogenic heterogeneity hinders accurate epidemiological estimates; in the United Kingdom (UK), GHD of unknown origin occurs approximately once in every 3800 births.1 Untreated males and females with GHD typically attain final heights of 134–146 cm and 128–134 cm, respectively,1 and endure a variety of concurrent metabolic and psychosocial morbidities, underscoring the importance of replacement GH therapy.

Recombinant human GH (rhGH, somatropin) stimulates production of insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), which increases bone growth, muscle strength, and cardiac output, and enhances expression of IGF binding proteins (IGFBP-3).2 However, growth response to GH treatment varies, even in a relatively homogeneous group of patients with defined inclusion-exclusion criteria, and with the same dose of GH used.3 There are various possible reasons for this difference in growth response between patients but, at least in individual patients, it remains obscure. As a result, each treated group of children can be arbitrarily subdivided into poor, average, and good responders dependent upon growth response. Nevertheless, the growth response during the first 6–12 months of treatment is predictive for further growth,4 and treatment with rhGH improves final height; normalizes pubertal, sexual, and reproductive maturation; attenuates metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors; and facilitates adult psychosocial development.5

Originally, therapeutic GH was extracted from cadaveric pituitary glands. However, by 1985, rhGH had replaced pituitary sources. More recently, rhGH preparations GH biosimilars have been developed. The term “biosimilar” mainly defines a drug approval procedure, and does not suggest that complex biopharmaceuticals deriving from the same substance are entirely identical.6 Indeed, the scientific and legal viability of biosimilars remains a topic of constant interest.7 A biosimilar can be considered interchangeable with a reference product if the data demonstrates that it can be expected to produce the same clinical result in any given patient, and that the risk associated with alternating or switching between the two products is not greater than that involved in continuing to use the reference product.8 In 2006, Omnitrope (Sandoz GmbH, Kundl, Austria) was granted market authorization under a new “biosimilar” regulatory pathway in Europe. This new pathway requires an extensive comparability exercise throughout the whole development process, including a phase 3 clinical study.9 In this study, the comparability of Omnitrope and its reference product, Genotropin (Pfizer Limited, Sandwich, UK), was demonstrated over 9 months.10 A subsequent analysis demonstrated that Omnitrope’s safety and efficacy was maintained during 7 years’ treatment.11 The inter-group comparisons confirmed that there was no significant difference between the two groups, even after switching all patients to Omnitrope. However, despite these data, and the decades of experience in treating patients with rhGH, some commentators have suggested caution in switching patients from one type of rhGH to another, suggesting an impact on efficacy and safety.12

In an attempt to address this issue, the current paper analyzes data from three phase 3 clinical studies10,11,13,14 to assess the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of Omnitrope in children switching from Genotropin to Omnitrope, compared with continuous Omnitrope treatment alone.

Methods

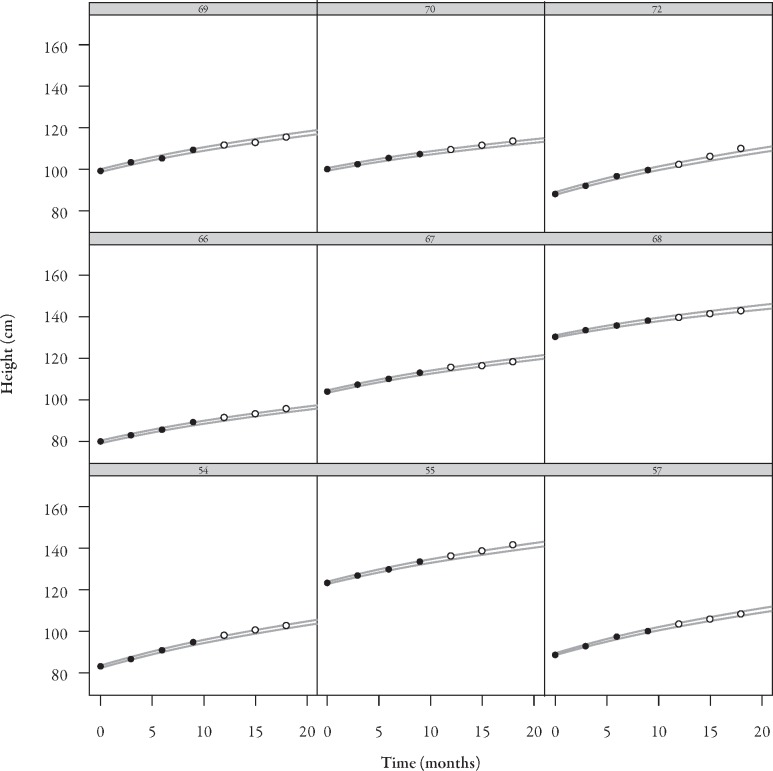

This paper is based on three studies: the AQ study;10,11 the Lyo study;13 and the Spanish study.14 Briefly, the AQ study consisted of two groups; patients in group A received Omnitrope powder in solution for injection (Omnitrope lyo) for 15 months, then received Omnitrope ready-to-use solution for injection (Omnitrope liquid) between months 15–84 (Figure 1).10,11 The 45 patients in group B received Genotropin for 9 months, and then switched to Omnitrope liquid until the end of the study. The comparison between the two groups has already been discussed in a previous publication.10 Thus, the current paper assesses outcomes of group B only, and compares these results with patients continuously treated with Omnitrope in the Lyo and Spanish studies. The Lyo study assessed continuous treatment with Omnitrope lyo for up to 54 months.13 The Spanish study assessed continuous treatment with Omnitrope liquid for up to 60 months.14 The current analysis includes 51 patients from the Lyo study and 70 from the Spanish study. In all studies, the patients were treated with a daily injection of 0.03 mg/kg body weight/day rhGH.

Figure 1.

Design of AQ study, Lyo study, and Spanish study. Omn=Omnitrope.

The comparative analyses focus on the first 18 months of GH treatment. Standardized growth curves were compared before and after switching from Genotropin to Omnitrope (AQ study) and with continuous Omnitrope treatment (Lyo and Spanish studies) at baseline, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 months. In terms of efficacy, two types of analyses were carried out. In a more traditional approach, the (standardized) growth curves were compared between switched children and children continuously treated with the same GH. The second analysis is based on a log-function model fitted to the growth observed during the 9 months’ treatment with Genotropin, and then used to predict growth for a subsequent 9 months as if Genotropin treatment had continued. These predictions were compared to the observed height after the switch to Omnitrope liquid. Concentrations of IGF-I and IGFBP-3 were measured as further surrogates of GH efficacy.

The incidences of anti-GH antibodies during the first and second 9 months of treatment as well as overall in switched and in nonswitched patients were compared to assess immunogenic potential. Safety was assessed based on the overall incidence of adverse drug reactions (ADR), as well as in the first and second 9-month periods of treatment in switched and nonswitched patients.

Descriptive statistics are provided as means ± SD or 95% CI.

Results

Demographics

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and baseline characteristics of the intent-to-treat population in the three studies, which are broadly similar despite some minor differences in the age and gender profiles. In the AQ study, one patient was excluded due to noncompliance during the first month, and another at month 15, also for noncompliance.

Table 1.

Summary of demographic and baseline characteristics of the intent-to-treat population in the AQ, Lyo, and Spanish studies.

| AQ study* | Lyo study | Spanish study | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients, n | 45 | 51 | 70 |

| Mean age at first visit, years (SD) | 7.4 (2.8) | 7.6 (2.6) | 8.7 (2.4) |

| Male patients, n (%) | 21 (47) | 30 (59) | 44 (63) |

| Mean height SDS at first visit (%) | −2.99 (0.72) | −3.21 (1.00)† | −2.98 (0.60)‡ |

| Mean weight at first visit, kg (SD) | 20.1 (7.5) | 19.9 (6.2) | 23.8 (6.7) |

| Caucasian patients, n (%) | 44 (100)§ | 51 (100) | 69 (99) |

| Patients with primary insufficiency of GH secretion, n (%) | 44 (100)§ | 51 (100) | 68 (97) |

| Patients with secondary insufficiency of GH secretion, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) |

Efficacy

Comparison of the (Standardized) Growth Development Between Switched and Nonswitched Patients

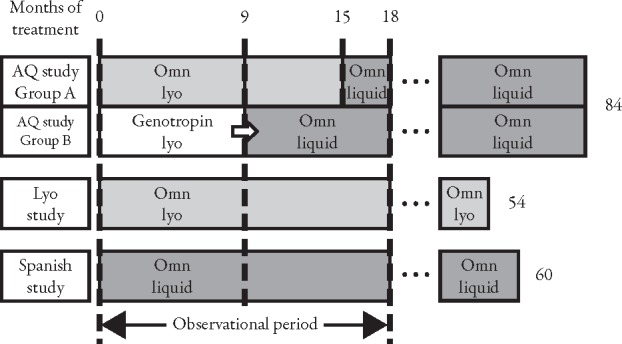

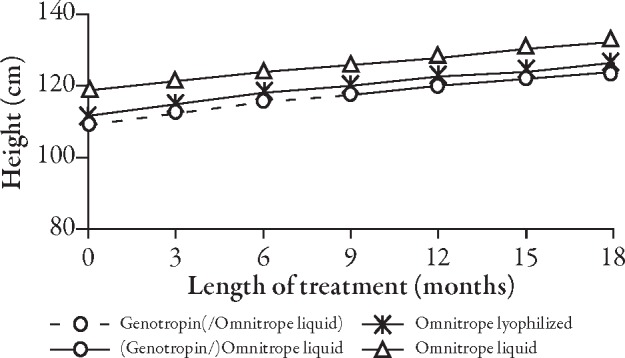

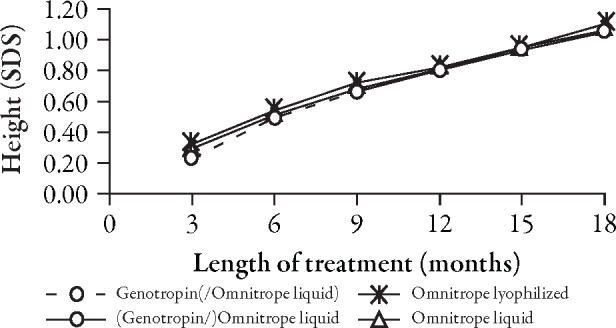

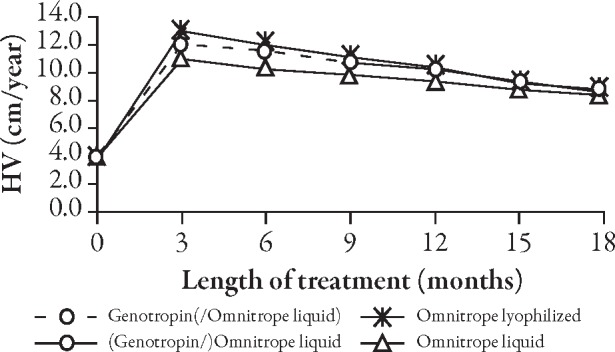

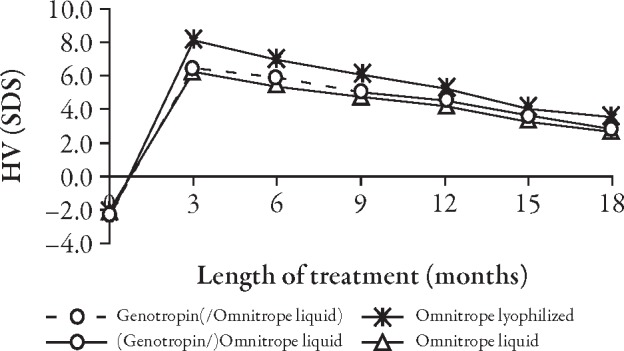

The curves for the development of height (Figure 2) and height SD score (SDS) (Figure 3, Table 2) do not show any apparent differences between children who received Genotropin followed by Omnitrope liquid and children treated continuously with either Omnitrope lyo or liquid. The change from baseline in height SDS (Figure 4), development of height velocity over time (Figure 5), and development of height velocity SDS (peak-centered, standardized according to Tanner;17 Figure 6, Table 3) over time are nearly identical and parallel, with differences at baseline carried forward during the treatment phase for all three studies. The curves for parameters describing height velocity show a similar decline after reaching slightly different peak responses after the first 3 months of treatment.

Figure 2.

Development of height over time.

Figure 3.

Development of height SD score (SDS) over time.

Table 2.

Comparison of differences in height SD score from baseline between the AQ, Lyo, and Spanish studies.

| n | rhGH | Differences | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQ study* (months) | ||||

| 3 | 42 | Genotropin | 0.30 | 0.23, 0.37 |

| 6 | 42 | Genotropin | 0.54 | 0.42, 0.66 |

| 9 | 42 | Genotropin | 0.69 | 0.54, 0.85 |

| 12 | 42 | Omnitrope liquid | 0.83 | 0.65, 1.01 |

| 15 | 42 | Omnitrope liquid | 0.96 | 0.75, 1.17 |

| 18 | 41 | Omnitrope liquid | 1.04 | 0.80, 1.29 |

| Lyo study (months) | ||||

| 3 | 51 | Omnitrope lyo | 0.33 | 0.26, 0.39 |

| 6 | 51 | Omnitrope lyo | 0.58 | 0.48, 0.69 |

| 9 | 51 | Omnitrope lyo | 0.75 | 0.61, 0.89 |

| 12 | 51 | Omnitrope lyo | 0.84 | 0.68, 1.00 |

| 15 | 50 | Omnitrope lyo | 0.97 | 0.79, 1.15 |

| 18 | 50 | Omnitrope lyo | 1.13 | 0.92, 1.33 |

| Spanish study (months) | ||||

| 3 | 70 | Omnitrope liquid | 0.26 | 0.22, 0.30 |

| 6 | 69 | Omnitrope liquid | 0.44 | 0.38, 0.49 |

| 9 | 69 | Omnitrope liquid | 0.59 | 0.52, 0.66 |

| 12 | 69 | Omnitrope liquid | 0.70 | 0.61, 0.79 |

| 15 | 69 | Omnitrope liquid | 0.81 | 0.71, 0.91 |

| 18 | 69 | Omnitrope liquid | 0.91 | 0.80, 1.01 |

*Group B of AQ study.

rhGH=recombinant human growth hormone.

Number of patients varies depending on the available data at each visit.

Figure 4.

Change from baseline in height SD score (SDS).

Figure 5.

Development of height velocity (HV) over time.

Figure 6.

Development of height velocity (HV) SD score (SDS) (Tanner, peak-centered) over time.

Table 3.

Comparison of differences in height velocity SD score from baseline between the AQ, Lyo, and Spanish studies.

| n | rhGH | Differences | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQ study* (months) | ||||

| 3 | 43 | Genotropin | 8.88 | 7.41, 10.36 |

| 6 | 43 | Genotropin | 8.31 | 7.27, 9.36 |

| 9 | 43 | Genotropin | 7.36 | 6.39, 8.33 |

| 12 | 43 | Omnitrope liquid | 6.86 | 5.99, 7.72 |

| 15 | 43 | Omnitrope liquid | 5.95 | 5.16, 6.73 |

| 18 | 42 | Omnitrope liquid | 5.10 | 4.29, 5.90 |

| Lyo study (months) | ||||

| 3 | 51 | Omnitrope lyo | 10.71 | 8.98, 12.43 |

| 6 | 51 | Omnitrope lyo | 9.55 | 8.21, 10.89 |

| 9 | 51 | Omnitrope lyo | 8.63 | 7.45, 9.81 |

| 12 | 51 | Omnitrope lyo | 7.79 | 6.71, 8.87 |

| 15 | 50 | Omnitrope lyo | 6.53 | 5.52, 7.53 |

| 18 | 50 | Omnitrope lyo | 6.07 | 5.13, 7.01 |

| Spanish study (months) | ||||

| 3 | 70 | Omnitrope liquid | 8.28 | 7.06, 9.51 |

| 6 | 69 | Omnitrope liquid | 7.41 | 6.52, 8.29 |

| 9 | 69 | Omnitrope liquid | 6.82 | 6.02, 7.63 |

| 12 | 69 | Omnitrope liquid | 6.26 | 5.48, 7.04 |

| 15 | 69 | Omnitrope liquid | 5.34 | 4.62, 6.07 |

| 18 | 69 | Omnitrope liquid | 4.69 | 3.97, 5.40 |

*Group B of AQ study.

rhGH=recombinant human growth hormone.

Number of patients varies depending on the available data at each visit.

Concentrations of IGF-I and IGFBP-3 rose during treatment with rhGH (Table 4) in all three studies, and the trend appeared to be comparable between studies.

Table 4.

Comparison of differences in insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 and IGF binding proteins (IGFBP)-3 from baseline between the AQ, Lyo, and Spanish studies.

| Months | n | Mean difference from baseline | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQ study* | ||||

| IGF-I (ng/mL) | 3 | 43 | 60.4 | 39.2, 81.7 |

| 6 | 43 | 134.6 | 102.0, 167.2 | |

| 9 | 43 | 171.5 | 126.3, 216.6 | |

| 12 | 43 | 217.0 | 177.3, 256.7 | |

| 15 | 43 | 214.8 | 167.4, 262.1 | |

| 18 | 42 | 276.6 | 228.8, 324.4 | |

| IGFBP-3 (ng/mL) | 3 | 43 | 1600 | 1150, 2050 |

| 6 | 43 | 1140 | 650, 1640 | |

| 9 | 43 | 1380 | 720, 2050 | |

| 12 | 43 | 2170 | 1700, 2640 | |

| 15 | 43 | 2750 | 2280, 3220 | |

| 18 | 42 | 2680 | 2110, 3240 | |

| Lyo study† | ||||

| IGF-I (ng/mL) | 3 | 51 | 80.1 | 66.8, 93.4 |

| 6 | 51 | 103.7 | 86.0, 121.4 | |

| 9 | 51 | 120.1 | 100.5, 139.6 | |

| 12 | 51 | 129.5 | 110.2, 148.9 | |

| IGFBP-3 (ng/mL) | 3 | 51 | 981.5 | 793.3, 1169.6 |

| 6 | 51 | 1083.6 | 821.1, 1346.2 | |

| 9 | 51 | 1136.0 | 952.2, 1319.8 | |

| 12 | 51 | 915.4 | 733.9, 1096.8 | |

| Spanish study | ||||

| IGF-I (ng/mL) | 3 | 64 | 83.8 | 61.5, 106.1 |

| 6 | 65 | 99.2 | 79.5, 118.9 | |

| 12 | 63 | 123.2 | 100.4, 146.0 | |

| 18 | 63 | 143.9 | 120.2, 167.6 | |

| IGFBP-3 (ng/mL) | 3 | 64 | 693.2 | 483.6, 902.7 |

| 6 | 65 | 880.2 | 657.6, 1102.7 | |

| 12 | 63 | 1052.5 | 830.4, 1274.5 | |

| 18 | 63 | 1054.3 | 826.8, 1281.7 |

*Group B of AQ study.

†Data unavailable for months 15 and 18.

Number of patients varies depending on the available data at each visit.

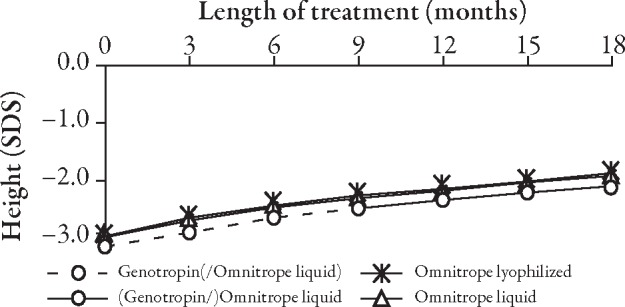

Model-Based Analysis

A log-function model fitted growth data observed during 9 months of treatment with Genotropin. Based on this model, the height up to month 18 was predicted and compared to the corresponding observed data. Figure 7 shows the prediction intervals together with the observed height measurements up to month 9 and beyond. Most values fall within the predicted boundaries. Patients with height measurements outside the predicted limits were also outside at baseline. Figure 8 shows individual predicted intervals versus observed growth in nine representative switched patients.

Figure 7.

Prediction intervals versus observed growth data in switched patients. Figure shows height data of 45 switched patients. Grey area=predicted limits; closed circles=Genotropin treatment; open circles=Omnitrope treatment.

Figure 8.

Nine examples of individual prediction intervals versus observed growth data in switched patients. Area between grey lines=predicted values; closed circles=Genotropin treatment; open circles=Omnitrope treatment.

Safety

All regimens were well tolerated, with few children experiencing ADRs (Table 5). For example, in the Spanish study, only 10 of the 69 children experienced an ADR at any time during the 5-year follow-up. During the first 9 months, only five patients were affected by ADRs, and in the second 9-month period only three patients were affected. Only one patient was affected in both study periods.

Table 5.

Incidence of adverse drug reactions during the first 18 months of treatment in all three studies.

| Baseline-9 months | 9–18 months | Odds ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| AQ study* (n=44) | 19 | 43.2 | 16 | 36.4 | 0.84 |

| Lyo study (n=50) | 12 | 24.0 | 10 | 20.0 | 0.83 |

| Spanish study (n=69) | 5 | 7.2 | 3 | 4.3 | 0.60 |

*Group B of AQ study.

In general, more ADRs were observed during the first than the second 9-month period of treatment, whether the patients were switched from Genotropin to Omnitrope liquid or stayed continuously on the same treatment (Table 5).

Immunogenicity

Immunogenicity was uncommon in the groups included in this analysis. For instance, no relevant increased risk of anti-GH antibodies emerged following the switch from Genotropin to Omnitrope liquid. The presence of anti-GH antibodies in more than one test during the first 9 months of treatment with Omnitrope liquid could be detected in only one patient (Table 6). After the 18-month period, another case of possible immunogenicity was detected, but this was of very short duration.

Table 6.

Incidence of anti-growth hormone (GH) antibodies* during the first 18 months of treatment and overall.

| Baseline-9 months | 9–18 months | Odds ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| AQ study† (n=44) | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.3 | − |

| Lyo study (n=50) | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | − |

| Spanish study (n=69) | 2 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 |

*Presence of an anti-GH antibody is defined by at least two consecutive positive test results.

†Group B of AQ study.

Similarly, no patient in the Lyo study developed anti-hGH antibodies during the first 18 months of treatment with Omnitrope Lyo. The only child who developed anti-GH antibodies showed the first positive results by month 30.

In the Spanish study, two children showed sustained positive antibody results for at least three consecutive visits during the first 9 months of treatment. In both cases, the results were negative by month 30.

Discussion

The present study confirms what has already been established in the phase 3 Omnitrope trial,10,11 in that there is no difference in the efficacy or safety of patients switched from Genotropin to Omnitrope compared to patients receiving Omnitrope throughout the treatment period.

The authors’ analysis has certain limitations. Firstly, these results are based on a post-hoc analysis rather than from a prospective comparative trial. However, the current analysis was not intended to demonstrate that Omnitrope has an efficacy and safety profile similar to that of Genotropin, which was already known. The real value of this analysis was to address the frequently debated fact that patients should not be switched between treatments. This analysis showed no signal that switching rhGH preparation would undermine safety or efficacy, and there was no evidence of any difference in clinical outcomes with the various rhGH preparations. A second limitation is that patients may vary in responsiveness to treatment. In the switched group of the AQ study, as well as in the Lyo and Spanish studies, a small proportion of patients were poor responders, while a similar proportion were very sensitive and grew faster than the other patients.18 Future analyses could examine whether sensitivities to rhGH could influence responses following a switch between rhGH preparations.

Thirdly, the observational period for this analysis was limited to 9 months before and after switching therapy, or 18 months’ continuous treatment. During this timeframe there were very few cases of immunogenicity. However, it is known that the most sensitive period regarding immunogenicity in GH treatment is the first year following treatment initiation,19 and this time period is covered within this analysis. Further studies with a longer follow-up are needed to confirm the promising profile seen in this switch analysis. However, this caveat applies to all outcomes with different rhGH preparations. Indeed, a consensus group concluded that prolonged follow-up in large cohorts and accurate estimates of expected background population disease rates are needed to exclude an increased risk of malignancy, diabetes mellitus, or other rare adverse events associated with childhood rhGH therapy.3

Finally, despite the potentially devastating consequences on height and other outcomes, poor adherence is relatively common among patients receiving rhGH. Indeed, some studies suggest that nonadherence rates are between 36%–49%.20 In the AQ study, there was no examination addressing whether adherence rates differed before and after the switch. However, the very similar efficacy rates and the absence of an a priori reason to suspect pharmacodynamic differences between the rhGH preparations suggest that adherence rates were similar and thus, the groups are comparable.

Receiving market authorisation under the new regulatory biosimilar pathway requires the implementation of an extensive comparability exercise with an established, authorized product. Thus, in the AQ phase 3 study, Omnitrope (AQ group A) demonstrated comparability regarding efficacy and safety profile with Genotropin (AQ group B — switched group).10,11 This indicates that Genotropin and Omnitrope are equally effective, a suggestion confirmed by the lack of significant difference in the biochemical surrogate markers IGF-I and IGFBP-3 (Table 4). Furthermore, the projected final height was 160.0 cm in girls and 172.5 cm in boys; an increase of 14 cm over baseline projections in both sexes, although the mean height velocity suggests there is still potential for further growth (data not shown). These efficacy results are consistent with growth profiles observed for other rhGH products.20 Also, the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity results in the Lyo and Spanish studies are as expected, and show that Omnitrope is an effective and well-tolerated treatment that increases the likelihood that children with GHD will reach a full height potential. In all three studies, the patients gained 1.04, 1.22, and 1.06 height SDS after 18 months of treatment for the AQ, Lyo, and Spanish studies, respectively.

For most medications used in the basic treatment of patients, switching between different preparations within the same International Nonproprietary Name (INN) is normal daily practice. In most health systems, this practice is recommended or even mandatory from a health economic perspective. Also, during therapy with rhGH several patients will be switched because of various reasons, including economic considerations, eg, due to instructions from health authorities. Despite these facts, a dogma still exists that patients should not be switched during treatment. Of course, the situation regarding GH treatment is a little more sensitive. In pediatric indications, treatment starts at a very young age. The children get used to their treatment and learn to trust their medication and device. As every rhGH is administered with its own specific device, a change of rhGH also means training the patient in the use of a new device. However, this can be easily solved by educating patients and switching to an easy-to-use device. The current data, which would ideally be confirmed in a prospective comparative trial, may represent first-line knowledge for Public Health Authorities with regards to the decision of switching between different preparations within the same INN being either recommended or even becoming mandatory.

By analyzing the potential difference in efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity in patients switching from Genotropin to Omnitrope compared with continuous Omnitrope treatment, this paper presents new scientific data regarding this topic and shows that switching from Genotropin to Omnitrope liquid does not show differences in efficacy, safety, or immunogenicity and, therefore, switching seems to be safe.

This analysis confirms that there is no appreciable difference in height development between children who received continuous treatment with either Omnitrope liquid or lyo, and those who switched from Genotropin to Omnitrope liquid. The curve for parameters related to height velocity show a similar decline after reaching slightly different peak responses after the first 3 months of treatment. These initial differences are mainly attributable to different age and sex profiles in the three populations, but the differences are still within the same CI.

In general, ADRs were more frequent during the first 9 months of treatment rather than the second, irrespective of whether the children switched from Genotropin to Omnitrope liquid or received continuous treatment with either lyo or liquid Omnitrope preparation. The odds ratios (OR) of experiencing an ADR in the second 9 months compared to the first 9 months were comparable in the AQ and Lyo studies. The difference between the first and second 9 months was more marked for the Spanish study, although these data require cautious interpretation due to the small incidences.

In the analyzed studies (switched group, Lyo, and Spanish study) immunogenicity was uncommon and no relevant increased risk of anti-GH antibodies emerged following the switch from Genotropin to Omnitrope liquid. The switch does not appear to increase the risk of immunogenicity. Based on these analyses, children can switch safely from one product, such as Genotropin, to Omnitrope.

The ability to switch to a more affordable, comparable product without compromising outcomes could improve access to rhGH as well as potentially releasing resources that purchasers could deploy to meet other healthcare priorities. In the United States alone, approximately 1:3500 children need treatment for GHD with GH products,21 and approximately 400,000 children with idiopathic short stature,22 according to the definition of Rekers-Mombarg et al.,23 qualify for GH treatment. However, rhGH can cost $20,000 or more per year for a 30 kg child and treatment may last at least 5 years.24 Although expensive, one analysis estimated an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of rhGH for idiopathic short stature of $52,634 per inch gained (2.54 cm), or $99,959 per child, compared to no therapy.25 Similarly, a Swedish study estimated an incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year of GH therapy of SEK 240,831 for children born small for gestational age, and SEK 120,494 for GHD.26 While many healthcare purchasers consider such cost-effectiveness ratios as acceptable,20 biosimilars reduce acquisition costs and, as the outcomes are the same, improve costeffectiveness ratios. In the UK, for example, Omnitrope costs between 20% and 30% less than other rhGH preparations.2 Therefore, biosimilars potentially increase accessibility to biopharmaceuticals.18

Conclusion

Switching from Genotropin to Omnitrope liquid has no negative impact on efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity. Growth outcomes and effects on IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 continue as expected and show no appreciable difference to children treated continuously with Omnitrope. The lyo and liquid Omnitrope preparations are well tolerated, and switching does not adversely affect safety. Thus, the Omnitrope preparations and Genotropin are comparable. Switching to a product which undergoes an extensive clinical comparability exercise seems to be safe.

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this manuscript was supported by a grant from Sandoz Biopharmaceuticals. The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Mark Greener, medical writer, and Springer Healthcare Ltd in the preparation of this manuscript. All authors were equally responsible for the drafting and the finalization of the manuscript. Tomasz E. Romer is the guarantor for this article, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Tomasz E. Romer has received support from Sandoz Biopharmaceuticals and has undertaken scientific collaboration with Pfizer and Ipsen. Mieczyslaw Szalecki and Mieczyslaw Walczak have undertaken scientific collaboration with Sandoz Biopharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Ipsen. Markus Zabransky and Sigrid Balser are employed by Sandoz International GmbH.

Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

To view enhanced content go to www.biologicstherapy-open.com

This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com

References

- 1.Takeda A., Cooper K., Bird A., et al. Recombinant human growth hormone for the treatment of growth disorders in children: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14:1–209. doi: 10.3310/hta14420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thakrar K., Bodalia P., Grooso A. Assessing the efficacy and safety of Omnitrope. Br J Clin Pharm. 2010;2:298–301. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kristöm B., Jansson C., Rosberg S., Albertsson-Wikland K. Growth response to growth hormone (GH) treatment relates to serum insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and IGF-binding protein-3 in short children with various GH secretion capacities. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:2889–2898. doi: 10.1210/jc.82.9.2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kriström B., Dahlgren J., Niklasson A., Nierop A.F.M., Albertsson-Wikland K. The first-year growth response to growth hormone treatment predicts the long-term prepubertal growth response in children. BMC Med Inform and Decis Mak. 2009;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clayton P.E., Cuneo R.C., Juul A., Monson J.P., Shalet S.M., Tauber M. Consensus statement on the management of the GH-treated adolescent in the transition to adult care. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;152:165–170. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.01829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ranke M.B. New preparations comprising recombinant human growth hormone: deliberations on the issue of biosimilars. Horm Res. 2008;69:22–28. doi: 10.1159/000111791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dudzinski D.M., Kesselheim A.S. Scientific and legal viability of follow-on protein drugs. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:843–849. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhle0706973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kozlowski S., Woodcock J., Midthun K., Sherman R.B. Developing the nation’s biosimilars program. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:385–388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1107285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoppe W., Berghout A. Biosimilar somatropin: myths and facts. Horm Res. 2008;69:29–30. doi: 10.1159/000111792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romer T., Peter F., Saenger P., et al. Efficacy and safety of a new ready-to-use recombinant human growth hormone solution. J Endocrinol Invest. 2007;30:578–589. doi: 10.1007/BF03346352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romer T., Saenger P., Peter F., et al. Seven years of safety and efficacy of the recombinant human growth hormone Omnitrope in the treatment of growth hormone deficient children: results of a phase III study. Horm Res. 2009;72:359–369. doi: 10.1159/000249164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gimberg A, Feudtner C, Gordon CM. Clinical impact of pediatric growth hormone brand switches. Consequences of brand switches during the course of pediatric growth hormone treatment. Endocr Pract. 2011 [E-pub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Peter F, Romer T, Koehler B, et al. 4 years of treatment with the rhGH Omnitrope® 5mg/mL lyophilized formulation in growth hormone deficient children: efficacy and safety results. LWPES/ESPE 8th Joint Meeting, New York, September 9–12, 2009. Abstract.

- 14.López Siguero J.P., Borrás Pérez V., Balser S., Khan-Boluki J. Long-term safety and efficacy of the recombinant human growth hormone Omnitrope® in the treatment of Spanish growth hormone deficient children: results of a Phase III study. Adv Ther. 2011;28:879–893. doi: 10.1007/s12325-011-0063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrández Longás A. Estudio longitudinal del crecimiento y desarrollo, centro Andrea Prader: estandares longitudinales de niños españoles normales controlados desde el nacimiento hasta la edad adulta. Zaragoza: Fundación Andrea Prader. ARPIrelieve. 2004;1–36.

- 16.Prader A., Largo R.H., Molinari L., Issler C. Physical growth of Swiss children from birth to 20 years of age. First Zurich longitudinal study of growth and development. Helv Paediatr Acta Suppl. 1989;52:1–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanner J.M., Whitehouse H., Takaishi M. Standards from birth to maturity for height, weight, height velocity, and weight velocity: British children, 1965, II. Arc Dis Child. 1966;41:613–635. doi: 10.1136/adc.41.220.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romer T.E. The role of recombinant growth hormone biosimilars in the management of growth disorders. Eur Endocrinol. 2009;5:47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rougeot C., Marchand P.M., Dray F., et al. Comparative study of biosynthetic human growth hormone immunogenicity in growth hormone deficient children. Horm Res. 1991;35:76–81. doi: 10.1159/000181877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haverkamp F., Johansson L., Dumas H., et al. Observations of nonadherence to recombinant human growth hormone therapy in clinical practice. Clin Ther. 2008;30:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindsay R., Feldkamp M., Harris D., Robertson J., Rallison M. Utah Growth Study: growth standards and the prevalence of growth hormone deficiency. J Pediatr. 1994;125:29–35. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(94)70117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardin D.S. Treatment of short stature and growth hormone deficiency in children with somatotropin (rDNA origin) Biologics. 2008;2:655–661. doi: 10.2147/btt.s2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rekers-Mombarg L.T., Kamp G.A., Massa G.G., Wit J.M. Influence of growth hormone treatment on pubertal timing and pubertal growth in children with idiopathic short stature. J Pediatr Endocrin Metab. 1999;12:1297–1306. doi: 10.1515/jpem.1999.12.5.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen D.B. Growth hormone therapy for short stature: is the benefit worth the burden? Pediatrics. 2006;118:343–348. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee J.M., Davis M.M., Clark S.J., Hofer T.P., Kemper A.R. Estimated cost-effectiveness of growth hormone therapy for idiopathic short stature. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:263–269. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christensen T., Fidler C., Bentley A., Djurhuus C. The cost-effectiveness of somatropin treatment for short children born small for gestational age (SGA) and children with growth hormone deficiency (GHD) in Sweden. J Med Econ. 2010;13:168–178. doi: 10.3111/13696991003652248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]