Abstract

Objective

Dual-energy X-ray computed tomography (DECT) offers visualization of the airways and quantitation of regional pulmonary ventilation using a single breath of inhaled xenon gas. In this study we seek to optimize scanning protocols for DECT xenon gas ventilation imaging of the airways and lung parenchyma and to characterize the quantitative nature of the developed protocols through a series of test-object and animal studies.

Materials and Methods

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal studies reported here. A range of xenon-oxygen gas mixtures (0, 20, 25, 33, 50, 66, 100%; balance oxygen) were scanned in syringes and balloon test-objects to optimize the delivered gas mixture for assessment of regional ventilation while allowing for the development of improved three-material decomposition calibration parameters. Additionally, to alleviate gravitational effects on xenon gas distribution, we replaced a portion of the oxygen in the xenon/oxygen gas mixture with helium and compared gas distributions in a rapid-prototyped human central-airway test-object. Additional syringe tests were performed to determine if the introduction of helium had any effect on xenon quantitation. Xenon gas mixtures were delivered to anesthetized swine in order to assess airway and lung parenchymal opacification while evaluating various DECT scan acquisition settings.

Results

Attenuation curves for xenon were obtained from the syringe test objects and were used to develop improved three-material decomposition parameters (HU enhancement per percent xenon: Within the chest phantom: 2.25 at 80kVp, 1.7 at 100 kVp, and 0.76 at 140 kVp with tin filtration; In open air: 2.5 at 80kVp, 1.95 at 100 kVp, and 0.81 at 140 kVp with tin filtration). The addition of helium improved the distribution of xenon gas to the gravitationally non-dependent portion of the airway tree test-object, while not affecting quantitation of xenon in the three-material decomposition DECT. 40%Xe/40%He/20%O2 provided good signal-to-noise, greater than the Rose Criterion (SNR > 5), while avoiding gravitational effects of similar concentrations of xenon in a 60%O2 mixture. 80/140-kVp (tin-filtered) provided improved SNR compared with 100/140-kVp in a swine with an equivalent thoracic transverse density to a human subject with body mass index of 33. Airways were brighter in the 80/140 kVp scan (80/140Sn, 31.6%; 100/140Sn, 25.1%) with considerably lower noise (80/140Sn, CV of 0.140; 100/140Sn, CV of 0.216).

Conclusion

In order to provide a truly quantitative measure of regional lung function with xenon-DECT, the basic protocols and parameter calibrations needed to be better understood and quantified. It is critically important to understand the fundamentals of new techniques in order to allow for proper implementation and interpretation of their results prior to wide spread usage. With the use of an in house derived xenon calibration curve for three-material decomposition rather than the scanner supplied calibration and a xenon/helium/oxygen mixture we demonstrate highly accurate quantitation of xenon gas volumes and avoid gravitational effects on gas distribution. This study provides a foundation for other researchers to use and test these methods with the goal of clinical translation.

Keywords: Quantitative Computed Tomography, Lung Imaging, Functional CT

Introduction

The earliest report of xenon gas as a radiopaque contrast agent used in conjunction with computed tomography (CT) imaging of the airways and pulmonary airspaces was presented in 1978 1, very early in relation to the development of computed tomography itself. Since that early observation there have been numerous reports of xenon-CT in the literature 2-18. Quantitative xenon-CT methods used to evaluate regional ventilation have employed wash-in and/or wash-out kinetic measurements 2,3,5-14,17,18 of the gas by imaging serially acquired axial stacks of images in conjunction with multi-detector row computed tomography (MDCT). This axial mode of scanning limits the z-axis coverage of the lung yet interrogates regional ventilation during, a ventilatory maneuver, thus providing a gold standard for regional ventilation. The procedures for dynamically following wash-in kinetics of xenon gas requires complex CT scanning methodologies that are difficult to transfer to clinical settings 17. The development of dual-energy CT (DECT) 19-21 has offered the possibility of imaging regional ventilation throughout the whole lung, albeit via a breath hold technique 15,19,22. Because little has been done to explore the quantitative measures obtained via the emerging static dual-energy CT methods of imaging the lung with xenon gas and because little has been done to evaluate optimal dual-energy xenon-CT imaging protocols to minimize the gravitational effects of the very dense xenon gas, we have undertaken, here, to explore xenon-CT imaging of regional ventilation by comparing and optimizing methodological approaches.

In developing xenon-CT, it is important to take into consideration the effect xenon itself has on the dynamics of gas distribution. When using xenon gas to image regional ventilation via radio-nuclear methods 23-31 one uses a very small amount of radioactive 133Xe gas. When xenon is used as a contrast agent for computed tomography, gas mixtures are on the order of 30-40% xenon for dynamic studies or higher in single breath studies. At this concentration of xenon, the inhaled gas mixtures will have considerably different physical properties than typical room air. For example, xenon gas (5.86 kg/m3) is much heavier than typical room air (1.293 kg/m3), thus gravity (along with altered viscosity) is modeled 32 to have a significant impact on its distribution during inhalation and may result in turbulent rather than laminar flow due to a considerably higher Reynolds number 33. Thus, as part of our efforts to understand and optimize xenon-CT methodologies, we here evaluate the fluid dynamic properties of the gas mixture through use of an airway phantom coupled with inclusion of helium gas to the xenon/oxygen mixture.

Materials and Methods

A series of test-objects were used to: 1) establish a density calibration curve associated with incrementally decreasing concentrations of xenon gas, 2) evaluate the use of resultant calibration curves to assess known volumes of xenon gas within balloons placed inside objects designed to simulate thoracic densities and 3) evaluate the role of gas density (He, Xe and O2 mixtures) and flow rates on the distribution of the gas in a rapid prototyped central airway tree. Animal studies were carried out to then evaluate the role of pitch, collimation and kVp pairs in dual-energy imaging to maximize signal and minimize artifacts.

DECT Technique

All imaging was performed on a second-generation DECT scanner (Somatom Definition Flash: Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany). Scan protocols varied according the particular question being asked as presented below.

Three-material decomposition

The issue in using dual-energy CT and xenon gas for assessing regional ventilation is that there are three unknown independent variables per voxel (air, soft tissue/blood, and xenon and only two measured linear attenuation coefficients per voxel. We solve this using a generalized three-material mass fraction decomposition technique discussed elsewhere 34.

Test-Object Experiments

Syringes

Plastic 60cc syringes filled with a range of xenon concentrations (0, 20, 25, 33, 50, 66, 100%; balance oxygen) were positioned in groups of three suspended in open air and inside an “Alderson RS-320 Lung/Chest Phantom” (Radiology Support Devices, Long Beach, CA) as depicted in the top panel of Figure 1. This syringe-based test-object was scanned using the standard dual-energy kVp pairs, 80/140Sn (tin filtered) kVp and 100/140Sn kVp with a 0.75 mm slice thickness, a 0.5 mm increment, and a 0.55 pitch, to establish scales for radiodensity enhancement as a function of photon energy. Empty space inside the phantom was filled with potato flakes, roughly simulating the density of lung parenchyma 35.

Figure 1.

Top Panel: Groups of three 60cc plastic syringes were sequentially placed inside an Alderson RS-320 Lung/Chest Phantom (Radiology Support Devices, Long Beach, CA) to establish radiodensity enhancement scales for xenon gas at different photon energies (80, 100, 140 kV). A volume rendering of the setup is show in the upper-left top-panel. A resultant xenon intensity image from dual-energy three-material decomposition is shown in the upper-right top-panel using the established scales. This result is also presented as an image fusion with the greyscale CT image, seen in the bottom-right top-panel, and rendered in 3D in the bottom-left top-panel. Bottom Panel: A hollow plastic airway phantom positioned along the imaging plane of the CT scanner is used to characterize inspired gas distribution to the central airways. The syringe manifold consisted of four 60cc syringes linked together to allow controlled delivery of gas to the phantom.

Balloon

Settings determined from the syringe calibrations were tested using a 3-L anesthesia-breathing bag (Vital Signs, Inc.; Totowa, NJ) positioned in open air as well as inside the chest phantom. The balloon was scanned after being initially filled with a known amount of xenon gas and room air. Small amounts of room air were sequentially added to increase the volume of gas in the balloon while keeping the total xenon content the same; the balloon was rescanned after each increase in volume. Scanning used the dual-energy kVp pairs of 80/140Sn (tin filtered) kVp with a 0.75 mm slice thickness, a 0.5 mm increment, and a 0.55 pitch. These scans were processed with the default three-material decomposition parameters provided by the scanner associated software as well as those derived from the syringe-based test-object. These image data sets were used to determine accuracy of xenon concentration metrics derived from the two calibration sets as a function of per voxel xenon concentration. Xenon volumes were assessed based upon per-voxel xenon concentration multiplied by the voxel volume and summed over the total number of voxels.

Rapid Prototyped Airway Tree

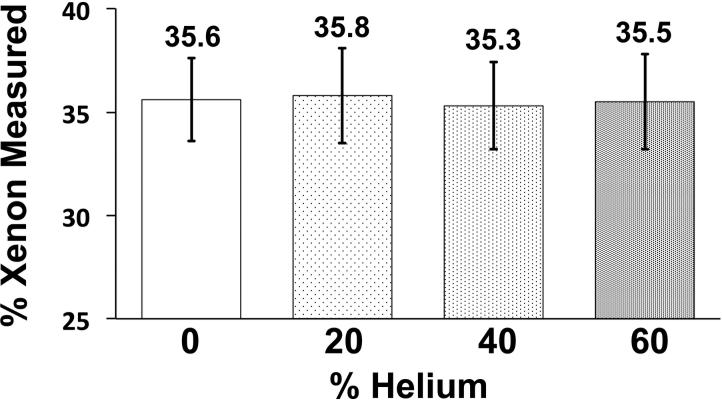

To examine the relationship between delivery rate, gas composition, and gas distribution during simulated inhalation, an experiment was performed in which various xenon gas mixtures were delivered via a syringe manifold (Figure 1, bottom panel) into a transparent plastic airway test-object. With the airway test-object positioned parallel to the detector plane of the scanner, axial (4-cm z-axis extent) time-series images (80 kVp, 150 mAs, 0.75 mm slice thickness, 0.5 mm increment, 0.28 sec rotation time, 60 time-points) were acquired during the delivery of the various xenon gas mixtures at two flow-rates (80%Xe/20%O2, 4.9738 kg/m3; 40%Xe/60%O2, 3.2014 kg/m3; 40%Xe/40%He/20%O2, 2.7012 kg/m3; composition and density respectively). The test-object was derived from a high resolution MDCT scan of a normal never-smoking male acquired previously on a Siemens Somatom 64 scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), at 95% vital capacity 17. Automatic segmentation and generation of the lung 36,37 and airway 38-40 masks were carried out through the use of Pulmonary Workstation (PW2, Vida Diagnostics, Coralville, IA). Based on the airway geometries, a rapid prototype of the segmented airways was generated through the use of a polycarbonate material, to ensure strength and durability. For each scan, time-versus-density profiles were created for regions of interest (ROI) placed in gravitationally dependent (right-main bronchus) and non-dependent (left-main bronchus) airways (Figure 5, top-row 2nd column). The maximal increase in density for each time-series was compared to its expected level, HUE = HUi + 2.25 * XeConc (HUE: ROI expected density; HUi: ROI baseline density; XeConc: concentration of xenon). Additionally, syringes filled with 40% xenon and a range of helium concentrations (20, 40, 60%; balance oxygen) were also scanned to determine the effect of the carrier gas used on radiodensity; seeking to verify that the decreased gas density caused by the use of helium gas does not affect material decomposition methods used in association with DECT measures.

Figure 5.

Helium gas does not affect the radiodensity of xenon gas. Columns represent the calculated dual-energy xenon signal from plastic syringes placed inside an artificial chest phantom (see Figure 1, top panel) filled with 40% xenon gas and various percentages of helium gas, balance oxygen. The xenon signal is the output of the three-material decomposition algorithm within Siemen's “xenon” module. (Error bars reflect ± standard deviation)

Animal Experiments

To further develop the optimum DECT imaging protocol scans from animal studies in which kVp pair, pitch, and collimation were varied following xenon inhalation were analyzed.

Animal Preparation

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal studies reported here. Five farm-bred ovine (40 kg ± 2.5; 3 males) and one farm-bred swine (60 kg; female) were premedicated with Ketamine (20 mg/kg) and Xylazine (2 mg/kg) intramuscularly, and anesthetized with 3–5% isoflurane in oxygen by nose cone inhalation. Once surgical depth of anesthesia was achieved, an 8.0-mm inner diameter cuffed endotracheal tube was placed through a tracheostomy and the animal was mechanically ventilated with 100% oxygen, tidal volume of 10-14 mL/kg, rate of 10-20 breaths/min adjusted to achieve an end-tidal PCO2 of 30–40 mm Hg. Carotid arterial and external jugular venous introducers were placed. Surgical plane of anesthesia was maintained with inhaled isoflurane (1–5% in oxygen), neuromuscular blockade was achieved with pancuronium (0.1 mg/kg IV initial dose and 0.5–1 mg/kg hourly as needed). Arterial pressure, oxygen saturation, and airway pressures were continuously monitored and recorded. Animals were placed in the supine position and held with gentle forelimb traction. Three ovine were used for protocol development. Two subsequent ovine were used to evaluate kVp combinations for use with dual-energy scanning and the final (sixth) animal was used to evaluate the role played by an addition of helium to a xenon/oxygen mixture to ameliorate the effects of altered density and viscosity of xenon on gas distribution patterns. For our sixth study we utilized a 60kg (male) swine, selected to better represent the size and shape of a standard adult male human thorax.

In the fourth and fifth animals (ovine), volumes of gas sufficient to raise mouth-pressure from 0 to 25 cmH20 were rapidly delivered via 3-L calibration syringe to the anesthetized supine animal and then scanned. The delivered gas mixtures were sequentially varied to include a higher proportion of xenon gas (0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100% Xe; balance O2) in each subsequent scan. Scans were acquired at both 80/140Sn and 100/140Sn during the same breath-hold. Whole lung and central airway segmentations were performed on the linear mixed images from each scan using Apollo (Vida Diagnostics, Coralville, IA). The mean and coefficient of variation of the xenon concentration in the lung parenchyma and central airways were then compared between the 80/140Sn and 100/140Sn scans.

The use of 80kVp versus 100kVp provides for a greater density separation between low and high kVp images critical for the accurate discrimination of low xenon concentrations 6. However, the use of lower photon energies increases the likelihood for signal artifacts (cupping etc.) caused by poor photon penetration especially in larger subjects. To verify that the 60kg swine reasonably represented what might be expected in regards to thoracic density and density distributions in humans, we utilized image data acquired from two human subjects (BMI of 25 and 33) associated with another ongoing study protocol approved by the institutional review board and radiation protection committees. The anterior-posterior and lateral cumulative tissue densities through mid thorax of the humans and swine were compared along line profiles extending between outside chest wall boarders.

A volume of 40% xenon, sufficient to raise mouth-pressure from 0 to 25 cmH20, was rapidly delivered via 3-L calibration syringe (Model 5530: Hans Rudolf, Kansas City, MO) to an anesthetized supine swine and then scanned. In addition to scanning at both 80/140Sn and 100/140Sn, various combinations of pitch and collimation were also acquired. These scans were qualitatively and quantitatively examined for artifacts by placing small circular ROIs along the x-axis of the same transverse slice from each scan. The mean and standard deviation of xenon concentration were calculated for each ROI and compared.

Results

Test-Object Results

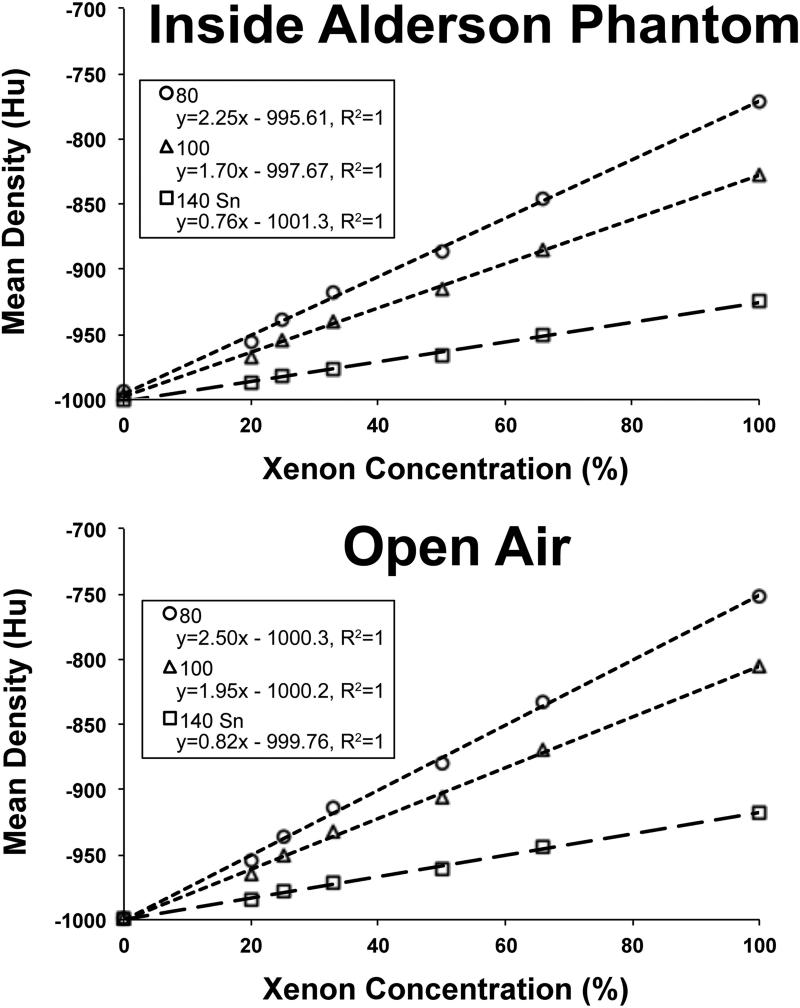

Using the scans of the xenon-filled syringes at 80,100, and 140Sn kVp, density enhancements as a function of xenon concentration were determined. Plots of mean density versus xenon concentration for the syringes in open air and within the Alderson RS-320 Chest Phantom are shown in Figure 2. Within the Chest Phantom, HU enhancement per percent xenon was 2.25 at 80kVp, 1.7 at 100 kVp, and 0.76 at 140 kVp (with tin filter). Similarly, in open air, HU enhancement per percent xenon was 2.5 at 80kVp, 1.95 at 100 kVp, and 0.81 at 140 kVp (with tin filter). These syringe tests provide two new sets of numbers to use in the scanner-based xenon three-material decomposition module. Our “within test-object” settings for 80 and 140 kVp respectively are: air; −993 and −1000 and xenon; −771 and −925. Similar “in-air” settings are air: −999 and −999 and xenon: −751 and −917. For reference, the default Siemens settings are air: −1000 and −1000 and xenon: −796 and −928 for 80 and 140 kVp respectively.

Figure 2.

Mean Hu measurements from the syringe studies, inside the Alderson RS-320 Lung/Chest Phantom and in open air, plotted as a function of xenon concentration.

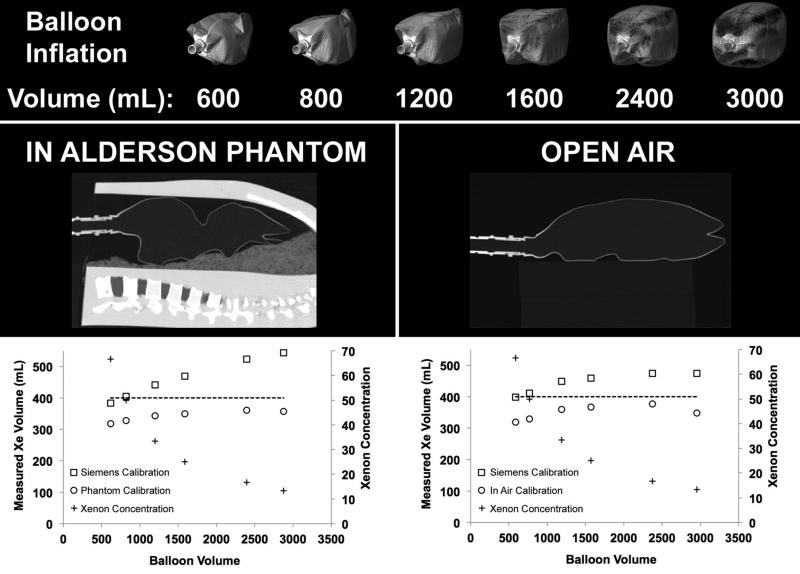

The comparisons between the Siemens’ default three-material decomposition calibration parameters and those derived from our syringe calibrations demonstrate noteworthy differences between the balloon inside the phantom and in open air (Figure 3, Table 1). The Siemens’ calibration over estimated the xenon content of each included voxel. Thus, as the number of included voxels increases with balloon volume, the estimation of overall xenon content increasingly diverged from the actual value (dotted line in graphs displayed in Figure 3). This effect was accentuated with the balloon placed inside the chest phantom (Figure 3, middle-left panel). The results from the new syringe-based calibrations were offset from the manufacturer's default calibrations and resulted in lower than expected calculated xenon content at the smallest balloon volumes, representing the highest per-voxel xenon concentrations. However, the estimation of total xenon content within the balloon showed much less deviation with increasing balloon volumes and in fact matched more closely with the expected xenon volume as the balloon volume increased. Volume renderings of the step-wise inflated balloon are shown in the top panel of Figure 3, and sagittal images of the balloon positioned within the phantom and in open air are shown in the lower panel of Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A 3-L respiratory balloon, place inside the Alderson chest phantom (middle-left panel) and in open air (middle-right panel), was filled with an initial amount of xenon gas and scanned via DECT. Small amounts of room air were then sequentially added to increase the volume of gas in the balloon while keeping the xenon content the same. The balloon was rescanned (bottom-row) after each increase in volume. The goal was to determine the quantitative accuracy of the assessment of total xenon content within the balloon as the concentration of xenon gas decreased while the xenon gas volume remained constant. Plots of xenon volume inside the phantom (top-left panel) and in open air (top-right panel) compare the default calibration with a custom calibration based on previous syringe tests.

Table 1.

Xe-DECT three-material decomposition calibration test results comparing the default values suggested by Siemens with those obtained via our syringe calibration in open air and inside the Alderson chest phantom.

| Instilled Volume | Measured Volume | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xe | Air | Total | %Xe | Mask Volume | Siemens Calibration | Phantom Calibration | |

| Inside Alderson Chest Phantom Tests | 400 | 200 | 600 | 67 | 616 | 383 | 318 |

| 400 | 400 | 800 | 50 | 821 | 405 | 328 | |

| 400 | 800 | 1200 | 33 | 1198 | 442 | 343 | |

| 400 | 1200 | 1600 | 25 | 1588 | 469 | 350 | |

| 400 | 2000 | 2400 | 17 | 2395 | 523 | 360 | |

| 400 | 2600 | 3000 | 13 | 2879 | 544 | 357 | |

| Instilled Volume | Measured Volume | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xe | Air | Total | %Xe | Mask Volume | Siemens Calibration | Open Air Calibration | |

| Open Air Tests | 400 | 200 | 600 | 67 | 588 | 398 | 319 |

| 400 | 400 | 800 | 50 | 767 | 411 | 329 | |

| 400 | 800 | 1200 | 33 | 1189 | 449 | 359 | |

| 400 | 1200 | 1600 | 25 | 1573 | 459 | 367 | |

| 400 | 2000 | 2400 | 17 | 2374 | 474 | 377 | |

| 400 | 2600 | 3000 | 13 | 2953 | 475 | 348 | |

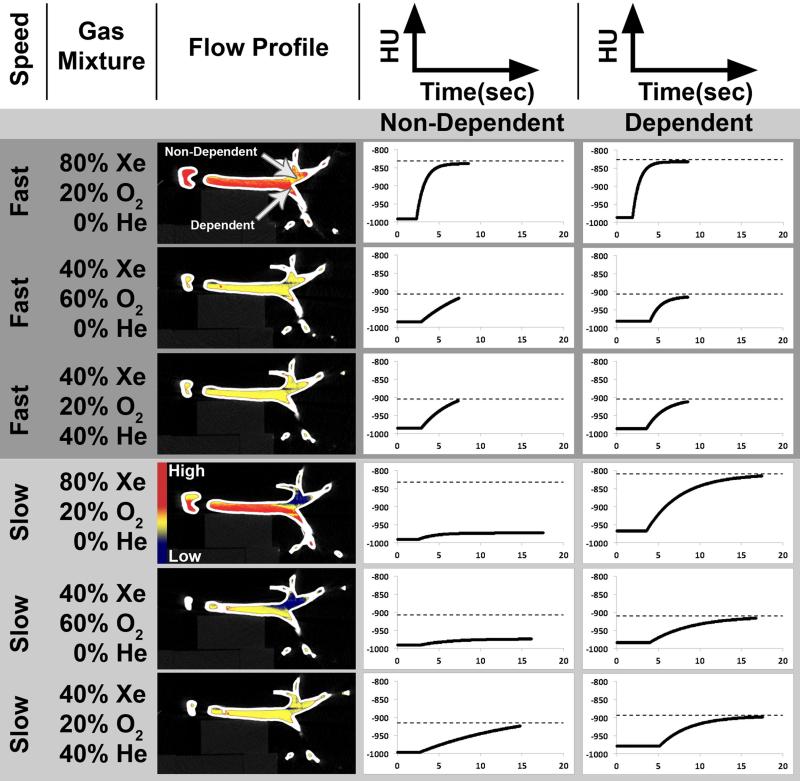

Time-series analysis of the 80%Xe/20%O2 and 40%Xe/60%O2 gas mixtures delivery to the hollow airway phantom indicated a flow-rate dependent profile. While gravitationally dependent airways achieved their expected maximal luminal density regardless of delivery speed (velocity) (Figure 4, right column), gravitationally non-dependent airways only achieved their expected maximal luminal density during high-speed delivery of xenon gas (Figure 4, middle column). However, when the gas density was lowered using a mixture containing helium (40%Xe/40%He/20%O2) the gravitational effects were attenuated, thus allowing both dependent and non-dependent airway pathways to achieve their expected luminal density at both delivered speeds (Figure 4, rows 3 and 6).

Figure 4.

Three xenon gas mixtures (80%Xe/20%O2; 40%Xe/60%O2; 40%Xe/20%O2/40%He) were delivered during time-series MDCT axial image acquisition, at fast and slow flow rates, to a hollow plastic airway phantom positioned along the imaging plane of the CT scanner (Figure 1, bottom panel). Gravitationally non-dependent and dependent ROIs were placed as shown in the flow profile column, row 1. Intensity vs. time plots for both ROIs are shown in the middle and right columns respectively, with dashed lines on each plot indicating the expected level of density enhancement from baseline for each gas mixture. With a fast delivery, density measurements for non-dependent and dependent ROIs reach their expected levels in all cases. However, when delivered slowly, gravity plays a larger role in the gas distribution. Thus, all of the dependent ROI reach expected levels; while the only non-dependent ROI to reach it's expected level is the one that includes helium.

To test the effect that helium vs. oxygen carrier gases had on the three-material decomposition-based assessment of xenon in a 40% xenon mixture, we replaced a portion of the oxygen with increasing amounts of helium within a set of 4 syringes. The syringes were placed in the Alderson Chest Phantom, and our developed xenon calibration shown in Figure 2 was used to assess xenon concentration in the 4 syringes. As demonstrated in Figure 5, the helium did not affect the calculated xenon percentage.

Animal Experiment Results

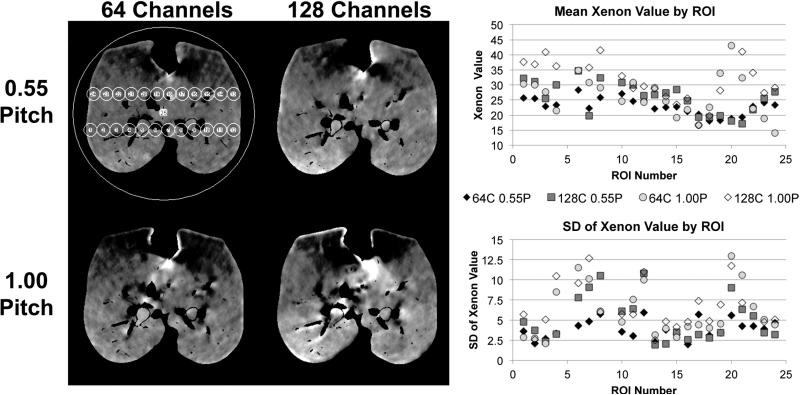

Deviations from the suggested default values for pitch and collimation from Siemens (0.55, 64 channels) yielded images suffering from considerable visual artifacts. Changing the pitch from 0.55 to 1.00, increasing the number of channels from 64 to 128, or doing both increased artifacts (Figure 6, left panel). The mean xenon value (Figure 6, upper-right panel) stays relatively consistent when the number of channels is changed from 64 to 128, however, the standard deviation (Figure 6, lower-right panel) increases in many of the ROIs. Changing the pitch from 0.55 to 1.00 causes variations in the mean xenon value and considerable increases in standard deviation.

Figure 6.

Deviations from the suggested default values by raising the pitch from 0.55 to 1.00, increasing the number of channels from 64 to 128, or doing both yielded considerable visual artifacts (left panel). The mean xenon value (upper-right panel) stays relatively consistent when the number of channels is changed from 64 to 128, however, the standard deviation (lower-right panel) increases in many of the ROIs. Changing the pitch from 0.55 to 1.00 causes variations in the mean xenon value and considerable increases in standard deviation.

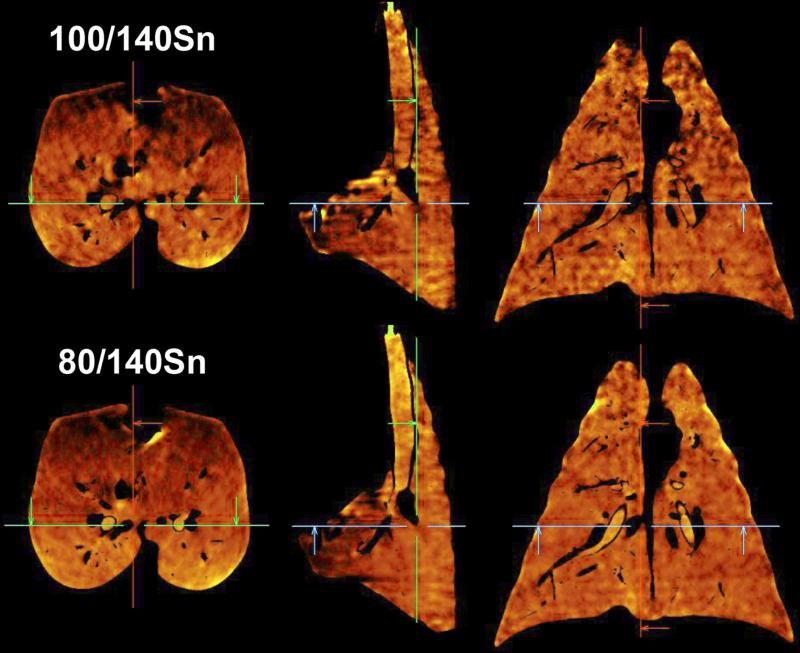

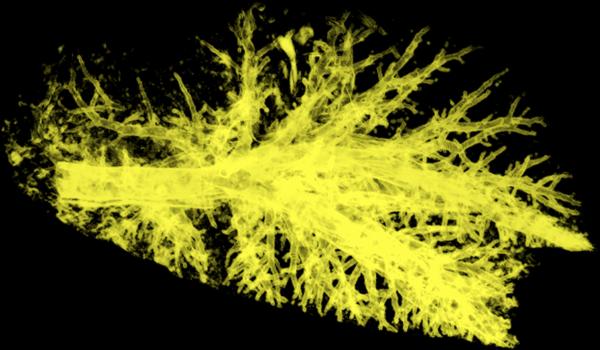

Scanning with 80/140Sn kVp yielded better overall dual-energy xenon-CT image quality compared to 100/140Sn kVp. Though a single-energy 100kVp scan has less image noise than an 80kVp scan 41, the lower HU enhancement of xenon at 100kVp produced inferior material separation and consequently inferior three-material decomposition. This difference was clear in the transverse (left column), sagittal (middle column), and coronal (right column) views from scans of a swine following a large single breath inhalation of 40%Xe/40%He/20%O2 gas mixture. As visualized in Figure 7, while the mean xenon concentrations for the entire lung were similar (80/140Sn, 22.7%; 100/140Sn, 21.8%) the coefficient of variation of xenon concentration was higher in the 100/140Sn scan (80/140Sn, 0.349; 100/140Sn, 0.380). Even more telling were the airways. For the same delivered xenon gas mixture, the airways were brighter the 80/140 kVp scan (80/140Sn, 31.6%; 100/140Sn, 25.1%) with considerably lower noise (80/140Sn, CV of 0.140; 100/140Sn, CV of 0.216). Thus the SNR (signal-to-noise ratio; SNR = 1/CV) for the 80/140 kVp pair was 7.1. For the 100/140 kVp pair SNR = 4.6. The SNR for the 80/140 kVp pair was greater than the Rose Criterion (SNR > 5) 42 while the 100/140 kVp pair was not. As seen in Figure 8, when a 40Xe/40He/20O2 gas mixture was used in conjunction with 80/140kVp DECT, good xenon delivery was achieved in both the dependent and non-dependent airway structures.

Figure 7.

Scanning with 80/140Sn kVp yields more accurate dual-energy xenon-CT images compared to those using 100/140Sn kVp. Transverse (left column), sagittal (middle column), and coronal (right column) views are shown from scans of a swine following a large single breath inhalation of 40%Xe/40%He/20%O2 gas mixture. The increased density separation between 80 and 140 kVp (bottom row) over 100 and 140 kVp (top row) allows for better calculation of xenon content. Airways are clearer and brighter in the 80/140 kVp results in addition to an overall smoother image.

Figure 8.

Volume rendered image of the three-material decomposition derived xenon imaged of a swine. Xenon-DECT using a 40%Xe/40%He/20%O2 gas mixture was successful in imaging all of the swine's central airways and peripheral airways out to those with an approximately 2-mm diameter.

The comparison between the 80/140Sn and the 100/140Sn kVp pairs in two animals (animals 4 & 5) scanned over a range of xenon concentrations (0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100% Xe) using a paired samples t-test showed statistically significant differences to the p<0.05 level between the mean of the measured xenon concentration in the lung parenchyma (p<0.001) and in the mean (p<0.001) and CV (p<0.001) of the measured xenon concentration in the central airway tree. The 80/140Sn was brighter with less noise in both the parenchyma and airways.

The body size comparison, using integrated radial density profiles, showed that the 60kg swine had a relative density of 138% of a human subject with body mass index of 25 and 89% of a human subject with body mass index of 33 respectively.

Discussion

An improved understanding of the technique and proper calibrations are necessary in order to accurately interpret physiological information from imaging studies. To that end, we have determined an optimized protocol to be used when performing a xenon-DECT scan. The protocol includes: a gas mixture containing 35-40% xenon while using a helium/oxygen mixture as the carrier gas, coached inhalation rates approximating that occurring during moderate exercise to adequately distribute to both gravitationally dependent and non-dependent lung regions, scanning with the 80/140Sn kVp pair for greater xenon contrast, while using 64 detector rows and the manufacturers recommended pitch setting of 0.55 to help limit imaging related artifacts. DECT reconstruction kernels were also used as directed by the manufacturer. While neither calibration in this study yielded the expected xenon content (400 mL) at every inflation level in the balloon test-object studies, the more consistent results from our calibrations allow for more reliable region-by-region comparisons.

Previous work using wash-in and wash-out xenon-CT techniques 6 have indicated that a 40% xenon gas concentration was minimal to achieve an SNR which allowed for curve fitting. To study a single breath hold DECT xenon gas protocol to evaluate regional ventilation, we have explored xenon gas concentrations of 25%, 40%, 60% and 80%. We considered that the administration of a gas mixture that is heavier than room air might have flow-dependent gravitational effects. The greater the gas density and the slower the gas flow the more likely opacification of only dependent airways would occur. This has been verified by use of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling 33. To explore whether or not these hydraulic properties of xenon gas might be brought more in line with room air by mixing xenon gas with helium we first sought to understand the effect of the presence of helium on the three-material decomposition methodologies. Initially we used cylindrical test-objects filled with different xenon and oxygen gas mixtures guide us to the minimal xenon gas concentration that provides adequate opacification of the airways. 40% xenon worked best and is tolerated by the patient. Honda et al. have used 35% xenon in conjunction with dual-energy imaging 15. The mean alveolar concentration whereby 50% of patients will respond to a verbal command (MAC awake) is 33%. This represents a concentration of xenon gas being delivered continuously. To prevent gravitational effects we used 40% helium gas along with the requisite 20% oxygen gas. At higher flow rates this provided good airway opacification of both dependent and non-dependent airways. These techniques were then performed in an anesthetized swine and confirmed that our technique was successful in imaging all of the swine's central airways and peripheral airways out to those with an approximately 2mm diameter as shown in Figure 8. The rapid prototyped airway tree test-object that we used was derived from a CT scan of an adult human. It has been shown that the bipodial airway branching pattern of a human results in different airflow patterns than animals with a monopodial branching pattern 43. The ability of the xenon/helium/oxygen mixture to overcome the gravity dependent effects in an animal with a monopodial branching pattern where gravity has an effect on flow properties more extreme than in humans provides a maximum challenge for such a methodology.

Xenon performs well as a contrast agent for DECT studies. However it is limited by its high density and anesthetic properties 44. Xenon is not the only radiodense gas. Recent work utilizing krypton (3.28 kg/m3) alone in conjunction with DECT has shown that a signal can be detected using three-material decomposition 45 whereby a maximum signal of 18 HU at an 80% concentration was observed and mean HU in emphysematous vs. normal appearing lung was 7.58±4.05 and 12.36±3.75 respectively. This is too low for assessment of regional ventilation heterogeneities other than large-scale pathologies. The lower signal enhancement from krypton yields data that is highly susceptible to image artifacts. It may be possible to use krypton alone in the future with advancements in reconstruction algorithms and detector design or as a supplement to xenon. The advantage of krypton is that it shows no anesthetic properties. Krypton gas has been shown to be useful as a supplementation to 40% xenon so as to increase signal-to-noise while avoiding the anesthetic effects of higher concentrations of xenon 6.

Three-material decomposition techniques for DECT have used paired x-ray tube peak energies of 100/140 kVp and 80/140 kVp. The demonstration that our swine studies provide a similar density load to the reconstructed images as would be expected from human scanning of subjects with a BMI between 25 and 33. Thus, our observations suggest that the use of 80/140 kVp would be appropriate for the majority of subjects up to a BMI of at approximately 33. A future and larger study would be needed to more specifically define a BMI cutoff for the use of 80/140 kVp for dual-energy xenon-CT in high BMI subjects. The observation that 80 kVp provides better contrast to noise in our xenon study compared with 100 kVp is in agreement with previous reports 15. Use of newly emerging iterative reconstruction techniques 46 along with more sensitive DECT detectors are expected to provide further improvements in contrast resolution.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that, with appropriate calibration, three-material decomposition methodologies used in conjunction with dual-energy computed tomography provides accurate measures of xenon gas volumes within a realistic thoracic phantom, and use of helium within a xenon/oxygen/helium gas mixture can overcome gravitational effects associated with the high density of xenon gas without affecting quantitative measurements and we recommend using a 40%Xe/40%He/20%O2 gas mixture. Since the MAC awake of xenon is 33% 44, we do not advise re-breathing a 40% xenon mixture to equilibration with alveolar gas. Instead,, if a full alveolar gas equilibration is desired, we recommend using a 33% Xe / 47% He / 20% O2 gas mixture. To further minimize gravitational effects, we recommend that inhalation of the xenon gas mixture be at a rate approximating that occurring during moderate exercise. For image acquisition, the 80/140Sn kVp energy pair provides improved xenon gas contrast as shown in DECT based on studies in an animal with a trans-thoracic density equivalent to that of up to a human subject with body mass index of 33 BMI. Additionally, scan settings should include a pitch of 0.55 and the use 64 channels. We have shown that adequate xenon signal is achieved with a single breath. Protocols where xenon is inhaled repeatedly to achieve a level of equilibration prior to acquiring a single DECT image data set will tend to mask slow versus rapidly equilibrating regions while highlighting ventilated versus non-ventilated regions. Clearly, the physician must now determine the physiologic information sought by use of xenon DECT rather than simply ordering a generic one-study-fits-all scan

Acknowledgments

Grants: This study was supported, in part, by NIH RO1-HL-064368.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Eric Hoffman is a founder and shareholder in VIDA Diagnostics, a company commercializing image analysis software developed at the University of Iowa.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Foley WD, Haughton VM, Schmidt J, et al. Xenon contrast enhancement in computed body tomography. Radiology. 1978;129(1):219–220. doi: 10.1148/129.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park E-A, Goo JM, Park SJ, et al. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Quantitative and Visual Ventilation Pattern Analysis at Xenon Ventilation CT Performed by Using a Dual-Energy Technique. Radiology. 2010;256(3):985–997. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chae EJ, Seo JB, Kim N, et al. Collateral Ventilation in a Canine Model with Bronchial Obstruction: Assessment with Xenon-enhanced Dual-Energy CT. Radiology. 2010;255(3):790–798. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10090947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoag JB, Fuld M, Brown RH, et al. Recirculation of inhaled xenon does not alter lung CT density. Academic Radiology. 2007;14(1):81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chon D, Simon BA, Beck KC, et al. Differences in regional wash-in and wash-out time constants for xenon-CT ventilation studies. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology. 2005;148(1-2):65–83. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chon D, Beck KC, Simon BA, et al. Effect of low-xenon and krypton supplementation on signal/noise of regional CT-based ventilation measurements. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102(4):1535–1544. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01235.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tajik JK, Chon D, Won C, et al. Subsecond multisection CT of regional pulmonary ventilation. Academic Radiology. 2002;9(2):130–146. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(03)80163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tajik JK, Tran BQ, Hoffman EA. Xenon-enhanced CT imaging of local pulmonary ventilation. Proceedings of SPIE. 1996;2709:40. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon BA, Marcucci C, Fung M, et al. Parameter estimation and confidence intervals for Xe-CT ventilation studies: a Monte Carlo approach. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84(2):709–716. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.2.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon BA. Regional ventilation and lung mechanics using X-Ray CT. Academic Radiology. 2005;12(11):1414–1422. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomiyama N, Takeuchi N, Imanaka H, et al. Mechanism of Gravity-Dependent Atelectasis: Analysis by Nonradioactive Xenon-Enhanced Dynamic Computed Tomography. Investigative Radiology. 1993;28(7):633–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snyder JV, Pennock B, Herbert D, et al. Local lung ventilation in critically ill patients using nonradioactive xenon-enhanced transmission computed tomography. Crit Care Med. 1984;12(1):46–51. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198401000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herbert DL, Gur D, Shabason L, et al. Mapping of Human Local Pulmonary Ventilation by Xenon Enhanced Computed Tomography. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 1982;6(6):1088. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198212000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gur D, Drayer BP, Borovetz HS, et al. Dynamic computed tomography of the lung: regional ventilation measurements. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1979;3(6):749–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Honda N, Osada H, Watanabe W, et al. Imaging of ventilation with dual-energy CT during breath hold after single vital-capacity inspiration of stable xenon. Radiology. 2012;262(1):262–268. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thieme SF, Hoegl S, Nikolaou K, et al. Pulmonary ventilation and perfusion imaging with dual-energy CT. European Radiology. 2010;20(12):2882–2889. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuld M, Grout RW, Guo J, et al. Systems for lung volume standardization during static and dynamic MDCT-based quantitative assessment of pulmonary structure and function. Academic Radiology. 2012;19(8):930–940. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding K, Cao K, Fuld M, et al. Comparison of image registration based measures of regional lung ventilation from dynamic spiral CT with Xe-CT. Med. Phys. 2012;39(8):5084–5098. doi: 10.1118/1.4736808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chae EJ, Seo JB, Goo HW, et al. Xenon ventilation CT with a dual-energy technique of dual-source CT: initial experience. Radiology. 2008;248(2):615–624. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2482071482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chae EJ, Seo JB, Lee J, et al. Xenon ventilation imaging using dual-energy computed tomography in asthmatics: initial experience. Invest Radiol. 2010;45(6):354–361. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181dfdae0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CW, Seo JB, Lee Y, et al. A pilot trial on pulmonary emphysema quantification and perfusion mapping in a single-step using contrast-enhanced dual-energy computed tomography. Invest Radiol. 2012;47(1):92–97. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e318228359a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goo HW, Yang DH, Hong S-J, et al. Xenon ventilation CT using dual-source and dual-energy technique in children with bronchiolitis obliterans: correlation of xenon and CT density values with pulmonary function test results. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40(9):1490–1497. doi: 10.1007/s00247-010-1645-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salanitri J, Kalff V, Kelly M, et al. 133Xenon ventilation scintigraphy applied to bronchoscopic lung volume reduction techniques for emphysema: relevance of interlobar collaterals. Intern Med J. 2005;35(2):97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bake B, Wood L, Murphy B, et al. Effect of inspiratory flow rate on regional distribution of inspired gas. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1974;37(1):8–17. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.37.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagner PD, Saltzman HA, West JB. Measurement of continuous distributions of ventilation-perfusion ratios: theory. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1974;36(5):588–599. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.36.5.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holley HS, Milic-Emili J, Becklake MR, et al. Regional distribution of pulmonary ventilation and perfusion in obesity. J Clin Invest. 1967;46(4):475–481. doi: 10.1172/JCI105549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.West JB. Pulmonary Function Studies with Radio-Active Gases. Annual Review of Medicine. 1967;18(1):459–470. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.18.020167.002331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glazier JB, Hughes JM, Maloney JE, et al. Vertical gradient of alveolar size in lungs of dogs frozen intact. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1967;23(5):694–705. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1967.23.5.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milic-Emili J, Henderson JA, Dolovich MB, et al. Regional distribution of inspired gas in the lung. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1966;21(3):749–759. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1966.21.3.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaneko K, Milic-Emili J, Dolovich MB, et al. Regional distribution of ventilation and perfusion as a function of body position. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1966;21(3):767–777. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1966.21.3.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bryan A, Milic-Emili J, Pengelly D. Effect of gravity on the distribution of pulmonary ventilation. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1966;21(3):778–784. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1966.21.3.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin C-L, Hoffman EA. A numerical study of gas transport in human lung models. Proceedings of SPIE. 2005;5746:92. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyawaki S, Tawhai MH, Hoffman EA, et al. Effect of carrier gas properties on aerosol distribution in a CT-based human airway numerical model. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2012;40(7):1495–1507. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0503-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu X, Yu L, Primak AN, et al. Quantitative imaging of element composition and mass fraction using dual-energy CT: three-material decomposition. Med. Phys. 2009;36(5):1602–1609. doi: 10.1118/1.3097632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoffman EA. Effect of body orientation on regional lung expansion: a computed tomographic approach. J Appl Physiol. 1985;59(2):468–480. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.59.2.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu S, Hoffman EA, Reinhardt JM. Automatic lung segmentation for accurate quantitation of volumetric X-ray CT images. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2001;20(6):490–498. doi: 10.1109/42.929615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang L, Hoffman EA, Reinhardt JM. Lung lobe segmentation by graph search with 3D shape constraints. Proceedings of SPIE. 2001;4321:204. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aykac D, Hoffman EA, McLennan G, et al. Segmentation and analysis of the human airway tree from three-dimensional X-ray CT images. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2003;22(8):940–950. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.815905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tschirren J, Palagyi K, Reinhardt J, et al. Segmentation, skeletonization, and branchpoint matching—a fully automated quantitative evaluation of human intrathoracic airway trees. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2002. 2002:12–19. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tschirren J, Hoffman EA, McLennan G, et al. Intrathoracic airway trees: segmentation and airway morphology analysis from low-dose CT scans. Medical Imaging, IEEE Transactions on. 2005;24(12):1529–1539. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2005.857654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Primak AN, Giraldo JCR, Eusemann CD, et al. Dual-Source Dual-Energy CT With Additional Tin Filtration: Dose and Image Quality Evaluation in Phantoms and In Vivo. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2010;195(5):1164–1174. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.ROSE A. Vision- Human and electronic(Book) New York. 1973 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kabilan S, Lin C-L, Hoffman EA. Characteristics of airflow in a CT-based ovine lung: a numerical study. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102(4):1469–1482. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01219.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cullen S, Gross E. The anesthetic properties of xenon in animals and human beings, with additional observations on krypton. Science (New York. 1951 doi: 10.1126/science.113.2942.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hachulla A-L, Pontana F, Wemeau-Stervinou L, et al. Krypton ventilation imaging using dual-energy CT in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: initial experience. Radiology. 2012;263(1):253–259. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baumueller S, Winklehner A, Karlo C, et al. Low-dose CT of the lung: potential value of iterative reconstructions. European Radiology. 2012;22(12):2597–2606. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2524-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]