Abstract

The comparison of genetic divergence or genetic distances, estimated by pairwise FST and related statistics, with geographical distances by Mantel test is one of the most popular approaches to evaluate spatial processes driving population structure. There have been, however, recent criticisms and discussions on the statistical performance of the Mantel test. Simultaneously, alternative frameworks for data analyses are being proposed. Here, we review the Mantel test and its variations, including Mantel correlograms and partial correlations and regressions. For illustrative purposes, we studied spatial genetic divergence among 25 populations of Dipteryx alata (“Baru”), a tree species endemic to the Cerrado, the Brazilian savannas, based on 8 microsatellite loci. We also applied alternative methods to analyze spatial patterns in this dataset, especially a multivariate generalization of Spatial Eigenfunction Analysis based on redundancy analysis. The different approaches resulted in similar estimates of the magnitude of spatial structure in the genetic data. Furthermore, the results were expected based on previous knowledge of the ecological and evolutionary processes underlying genetic variation in this species. Our review shows that a careful application and interpretation of Mantel tests, especially Mantel correlograms, can overcome some potential statistical problems and provide a simple and useful tool for multivariate analysis of spatial patterns of genetic divergence.

Keywords: “Baru” tree, genetic distances, geographical genetics, partial correlation, partial regression

Introduction

The estimation of genetic divergence between individuals from different localities (“populations” hereafter) has been an important component of empirical studies in population genetics. These studies are supported by a strong theoretical basis since the classical papers by S. Wright, R.A. Fisher and G. Malecot, among others (Epperson, 2003). The most popular approaches for estimating divergence include calculation of genetic distances and variance partitioning among and within populations using Wright’s FST and other related statistics, such as GST, AST, RST, θST and φST (see Holsinger and Weir, 2009 for a recent review). For instance, the FST gives an estimate of the balance of genetic variability among and within populations, and is an unbiased estimator of divergence between pairs of populations under an island-model in which all populations diverged at the same time and are linked by approximately similar migration rates. However, migration rates usually vary proportionally with geographical distances, so that pairwise FST estimates between pairs of populations vary.

Regardless of how genetic divergence among populations is computed, a recurrent goal in landscape genetics is to evaluate the amount of spatial structure in the genetic distance matrix. For instance, it is common to use cluster (such as UPGMA or Neighbor-Joining) and ordination techniques (e.g., Principal Coordinates Analysis) to visualize the relationships among populations based on these matrices (see Lessa, 1990; Felsenstein, 2004). More recent techniques, such as Bayesian approaches (see Balkenhol et al., 2009; Guillot et al., 2009), do not start from pairwise distances, but follow a similar reasoning of establishing clusters based on genetic differentiation among individuals. However, these approaches do not explicitly evaluate the effect of geographic space. By far, the Mantel test is the most commonly used method to evaluate the relationship between geographic distance and genetic divergence (Mantel, 1967; see Manly, 1985, 1997).

The Mantel test was proposed in 1967 to test the association between two matrices and was first applied in population genetics by Sokal (1979). Despite recent controversies and criticisms about its statistical performance (e.g. Harmon and Glor 2010; Legendre and Fortin, 2010; Guillot and Rousset, 2013) and the existence of more sophisticated and complex approaches to analyze spatial multivariate data, the Mantel test is still widely used. We believe that at least part of the problems associated with this test is due to lack of understanding of basic aspects of the test and misinterpretations in empirical applications.

Here we review the Mantel test and its extensions (Mantel correlogram, partial correlation and regression), discussing how it can be associated with theoretical models in population genetics (i.e., isolation-by-distance and landscape models). Routines of different forms of the Mantel test are widely available in several computer programs for population genetic analyses (Table 1) and in several packages for the R platform (R Development Core Team, 2012). All Mantel tests performed here were conducted using the R packages vegan (Oksanen et al., 2012) and ecodist (Goslee and Urban, 2007) and a complete script is available from the authors upon request.

Table 1.

Some of the softwares available for different approaches based on Mantel tests, including simple Mantel test (S), partial Mantel tests (P) and correlograms (C), and the website where they can be found.

We illustrate several applications of the Mantel test using an example based on population genetic divergence among Dipteryx alata populations, the “Baru”, an endemic tree widely distributed in the Brazilian Cerrado biome (see Diniz-Filho et al., 2012a,b; Soares et al., 2012). Previous analyses suggested that spatial patterns of genetic variability in this species are due to a combination of isolation-by-distance and range expansion after the last maximum glacial, creating clines in some loci.

Original Formulation

The Mantel test, as originally formulated in 1967, is given by

where gij and dij are, respectively, the genetic and geographic distances between populations i and j, considering n populations. Because Zm is given by the sum of products of distances its value depends on how many populations are studied, as well as the magnitude of their distances. The Zm-value can be compared with a null distribution, and Mantel originally proposed to test it by the standard normal deviate (SND), given by

where var(Zm) is the variance of the Zm (see Mantel, 1967 and Manly, 1985 for detailed formulas). Later, however, Mielke (1978) showed that this formulation is biased, working well only for large sample sizes, and suggested that a null distribution must be obtained empirically by permuting rows and columns of one of the distance matrices.

Thus, the idea underlying Mantel’s randomization test is that if there is a relationship between matrices G and D, the sum of products Zm will be relatively high, and randomizing rows and columns will destroy this relationship so that Zm values, after randomizations, will tend to be lower than the observed. If one generates, say, 999 values and none of the randomized Zm-values is higher than the observed, it is possible to conclude that the chance to observe a Zm-value as high as the observed by chance alone is 1/999+1 (the 1 is the observed, which is conservatively added to both the numerator and denominator). This is then the p-value from Mantel test.

One can also use a standardized version of the Mantel’s test (ZN):

using the means (Ḡ and D̄) and the variances (var(G) and var(D)) of the matrices G and D. The standardized version of Mantel’s test (ZN) is actually the Pearson correlation r between the standardized elements of the matrices G and D. ZN values close to 1 indicate that an increase in geographic distance between populations i and j is related with an increase in genetic distances between these populations. ZN values close to −1 indicate de opposite pattern, and ZN values close to zero indicate that there is no relationship between the two matrices. Notice also that if the two matrices G and D are standardized prior to the analysis (so that the mean is equal to 0 and variance is equal to 1) Mantel original Zm and standardized ZN have exactly the same value. For simplicity of notation, this standardized Mantel test ZN will be referred to hereafter as Mantel correlation rm.

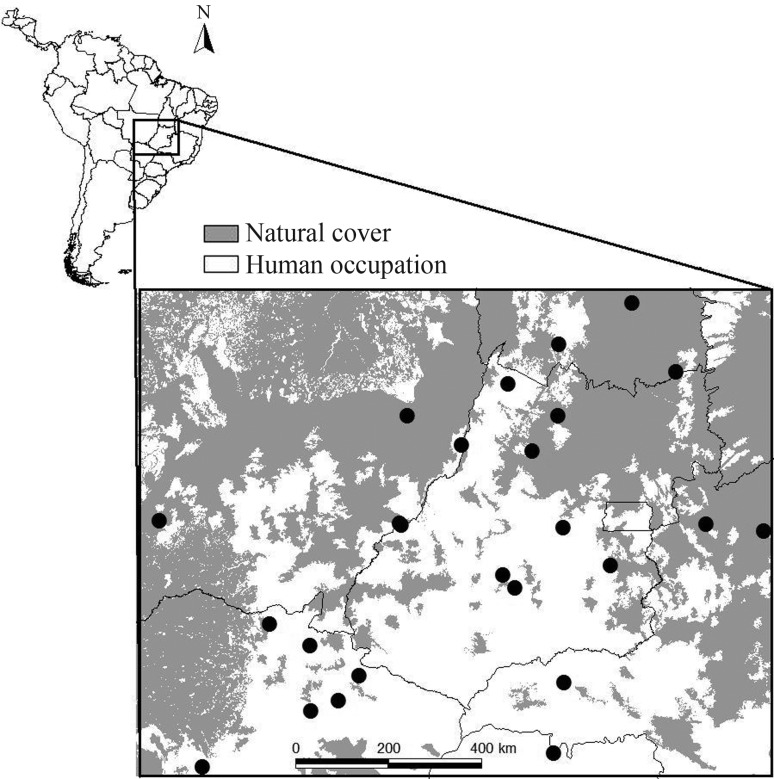

The dataset for Dipteryx alata populations used throughout the text consists of genotypes based on 8 micro-satellite loci of 644 individuals collected in 25 populations of the Brazilian Cerrado (States of Goiás, Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul, Minas Gerais and Tocantins, Figure 1; see Diniz-Filho et al., 2012a,b for details). The overall FST was equal to 0.254, indicating a spatial heterogeneity among populations. We built matrices of genetic distances among population by calculating pairwise FST estimated by an Analysis of Variance of Allele Frequencies (Holsinger and Weir, 2009) and Nei’s genetic distances (these two genetic distances are strongly correlated: rm = 0.868; p < 0.001). We then correlated these genetic distance matrices with pairwise geographic distances (measured in kilometers) between populations. Results of Mantel tests are qualitatively the same using pairwise FST or Nei’s genetic distances, so a G matrix is hereafter given by the pairwise FST.

Figure 1.

The twenty-five populations of Dipterx alata, the “Baru” tree, for which 644 individuals were genotyped for 8 microsatellite loci, used in the examples for the Mantel test. Dark regions represent remnants of natural vegetation.

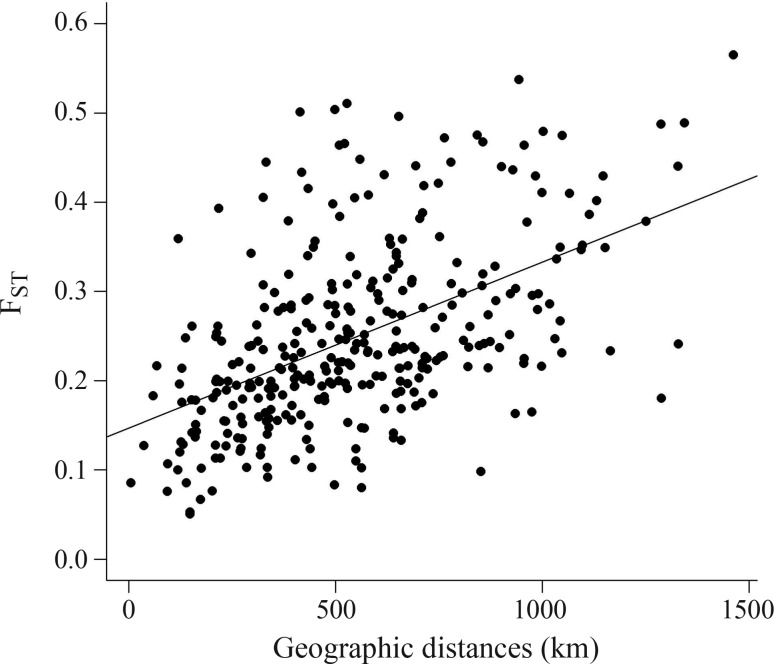

The first and simplest application of the Mantel test is to correlate genetic (G) and geographic (D) distances, seeking for spatial pattern of genetic variation. The Mantel correlation between G and D matrices was equal to 0.499. The scatterplot between elements in G and D matrices showed a linear relationship between genetic and geographic distances (Figure 2). Performing 4999 randomizations of the rows and columns of G generated the distribution of correlations under the null hypothesis. Out of these 4999 values, none was larger than the observed value of 0.499, so that the chance of obtaining a value as large as the observed is smaller than 1/5000, indicating a p-value of 0.0002. Thus, we conclude that nearby populations tend to be genetically more similar than expected by chance, and genetic differences increase linearly with geographic distances.

Figure 2.

Relationship between pairwise FST and geographic distances (r = 0.499) for the 25 “Baru” populations.

Two Useful Extensions: Mantel Correlograms And Partial Mantel Tests

Mantel correlograms

The Mantel correlation, as shown in Figure 2, shows the overall relationship between matrices G and D. However, it is often interesting to study the relationship between genetic and geographic distances across space, especially if this relationship is not linear. Thus, the matrix D can be divided into several sub-matrices, each one describing pairs of populations within a bounded interval of geographic distances. Specifically, this is done to describe possible variations in the correlation between genetic and geographic distances. These matrices, called here Wk, express in a binary form (0/1 values) if pairs of populations are connected (a value of 1), or not (a value of 0), within a given geographic distance range, usually referred as “distance class” k. To analyze the variation of correlation coefficients across space it is, however, necessary to create multiple non-overlapping and contiguous distance classes. Thus, several Mantel correlations are obtained by performing a Mantel test between G and the matrices W1, W2, W3, ..., Wk. Finally, the Mantel correlogram is constructed by plotting Mantel correlations between G and each W against the mid-point of the respective distance class k (Oden and Sokal, 1986; Legendre and Legendre, 2012). The definition of distance classes, both in terms of the total number of classes and their upper and lower limits, is somewhat arbitrary and depends on the spatial distribution of the populations. A “rule of thumb” suggests about four to five classes for 20 populations.

From a statistical point of view it is recommendable to keep the number of links (pairs of populations) within each matrix W approximately constant, which may require unequal distance intervals (e.g., 0–100 km, 100–250 km, 250–500 km, 500–2000 km, see Sokal and Oden, 1978a,b for a discussion). The most important issue about correlograms is that they should capture a continuous distribution in geographic space. Thus, it is desirable to have a large number of classes. However, one must keep in mind that, if the number of populations is relatively small, or if the populations are distributed irregularly across space (e.g. aggregated in clusters), it may not be possible to use a large number of distance classes. This is so because there may not be enough pairs of populations within a given distance class to provide a reliable estimate of the correlation.

For the “Baru” populations, a correlogram with five geographic distances classes indicated that populations distant by 156 km (first distance class: from 0 km to 318 km) tend to be similar (rm = 0.337; p < 0.001 with 4999 permutations) (Figure 3a). The Mantel correlation decreased more or less linearly up to a value of −0.333 (p < 0.001) in the last distance class, when populations were approximately 1120 km apart. As discussed earlier, negative correlation values indicate that populations that are located at a given distance apart tend to be genetically dissimilar. Notice, however, that the Mantel correlations in both the first and last distance classes were not very high (i.e., −0.33), indicating that the spatial structure is not strong (remember that the overall Mantel test is 0.499, so that only about 24.9% (i.e. 0.4992) of the genetic divergence is explained by geographic distance - see below).

Figure 3.

Mantel correlogram (A) and distogram (B), the latter one given by the mean FST in each distance class.

It is also possible to compute the mean FST within each distance class and plot it against the mean value of the class (Figure 3b). This is sometimes called distogram and provides an interesting and more direct visual evaluation of spatial patterns in genetic structure. For the “Baru” dataset, when nearby populations in the first distance class were compared, the mean FST was 0.224 (smaller than the overall value of 0.367), whereas in the last distance class the mean FST was equal to 0.522, which is higher than the mean value.

Thus, the correlogram and the distogram showed a continuous and linear decrease of genetic similarity (a higher mean FST, and a lower Mantel correlation) when geographic distance increased (Figure 2a). This result is expected when there is a clinal pattern of genetic variation in the studied region (i.e., when allele frequencies decrease or increase in a directional way). Spatial clines can arise by selection along environmental gradients (unlike in the case of microsatellite markers), and/or by range expansions or diffusion of genes through space in migratory events or allelic surfing. Indeed, previous analyses suggest that patterns of genetic variation in “Baru” are related to range expansions from north to south, tracking climate changes after the last glacial maximum (see Diniz-Filho et al., 2012b).

Other more complex patterns can be detected using correlograms, and perhaps the most common pattern observed in nature is an exponential-like decrease in which there are high Mantel correlations in the first distance classes, which tend to decrease and stabilize after a given distance class, indicating that there are patches of genetic variation or similarity. These patches can be caused by several factors, including different environments driving genetic variation (again unlike in the case of microsatellites), or the subdivision of the studied region by barriers, or simple isolation-by-distance (see below). The geographic distance at which the Mantel correlation is zero or non-significant indicates the size of the patch, and this can be useful for understanding population and genetic dynamics in space (see Sokal and Wartenberg, 1983; Sokal et al., 1997). Patch size can also be used for establishing more efficient approaches in conservation genetics, allowing to estimate regions within which genetic variability is similar (see Diniz-Filho and Telles, 2002, 2006).

When exponential-like correlograms appear, the overall Mantel test may be a poor estimate of the spatial pattern because it assumes a linear correlation between matrices. Thus it is important to check for non-linearity and heteroscedastic relationships between geographic and genetic distances with a simple scatterplot before interpreting the result of a global Mantel test. An even safer alternative would consist in using correlograms instead of the simple Mantel test (see Borcard and Legendre, 2012).

Finally, it is also important to highlight that, despite recent discussions on the validity of the Mantel test (especially of the partial Mantel tests, see below), the Mantel correlogram deserves its place in the ecologist’s “toolbox”. For instance, Borcard and Legendre (2012) recently used several simulations to show that the statistical performance of a Mantel correlogram, for both Type I and Type II error rates, is reliable.

Partial Mantel tests

Another possibility for using the Mantel test is to compare the relationship between two matrices, but taking into account the effect of a third one (usually the geographical distances), as originally proposed by Smouse et al. (1986). When analyzing spatially distributed data, the main issue is to find out if the two matrices are “causally” related (i.e., in the sense that they indicate an ecological or evolutionary process), or if the observed relationship appears only because both variables are spatially structured by intrinsic effects (i.e., distance-structured dispersal causing more similarity between neighboring populations).

When one is interested in evaluating the statistical correlation between two variables (say, an allele frequency and temperature) whose values are spatially distributed, the most common (and statistically sound) approach is to apply spatial regression, methods (see Diniz-Filho et al., 2009 for a review using genetic data and Perez et al., 2010 for an application). However, when the hypotheses are specified in terms of distance matrices, such as in the case of isolation-by-distance and many landscape models (see Wagner and Fortin, 2013), the most popular approach is to apply partial Mantel tests (see Legendre and Legendre, 2012 for a review).

There are several forms of partial Mantel tests (see Smouse et al., 1986; Oden and Sokal, 1992; Legendre and Legendre, 2012), but the general reasoning is to evaluate how two matrices are correlated after controlling, or keeping statistically constant, the effect of other matrices (see Sokal et al., 1986, 1989, for initial applications). In a first approach, it is possible to calculate the partial correlation between matrices G and E (where E is a distance matrix that one wants to correlate with G, keeping matrix D constant). The partial correlation is given by

where ZN(GE) is, for instance, the correlation coefficient between matrices G and E and r(GE|D) is the correlation between G and E, after taking D into account.

To illustrate these approaches with the “Baru” dataset, it is necessary to generate other explanatory matrices. First, for each locality, we obtained the altitude and 19 bioclimatic variables from WorldClim (Hijmans et al., 2005) and, after standardizing each variable to zero mean and unity variance, an environmental (Euclidean) distance matrix for all possible pairwise combinations of the local populations was obtained. This matrix (E) expresses then the environmental (mainly climatic) differences between populations. Second, we also estimated the amount of natural habitats remaining between pairs of populations, as the proportion of natural habitats in a 10 km wide “corridor” linking two populations (a matrix R). This matrix was derived from land use data obtained using the vegetation cover maps of the Brazilian biomes at the 1:250.000 spatial scale, based on compositions of the bands 3, 4 and 5 of Landsat 7 ETM+ images of the year 2002 (see Diniz-Filho et al., 2012a).

A simple Mantel correlation revealed that FST is not correlated to the proportion of the natural remnants matrix R (rm = −0.23; p = 0.142), and that this matrix is not spatially correlated (rm= −0.075; p = 0.552). Thus, no further partial analyses were needed (Dutilleul, 1993). However, FST is significantly correlated with environmental distances E according to a simple Mantel test (rm = 0.302; p = 0.008). However, we already know that genetic divergence is spatially patterned (rm = 0.499) and there is also a very strong spatial pattern in environmental variation E (rm = 0.838; p < 0.001). Thus, the main issue is to test if there is a correlation between G and E, after taking the geographic distances (matrix D) into account. This relationship is not expected for neutral markers as microsatellites, except if one considers that these loci are linked with adaptive ones.

Indeed, the partial correlation between G and E, after taking into account geographic distances D, was equal to - rm(GE|D) = −0.248 (p = 0.956), so the relationship between genetic and environment disappeared when geographic structure common to both matrices was accounted for (as in principle expected for neutral markers, as pointed out above). First, it is possible to quantify the relationships between FST and geographic distance D and environmental distance E by partial coefficients of determination, disentangling the amount of variation explained by each predictor matrix and their shared contribution (see Pellegrino et al., 2005 for an application in a phylogeographical context). In the “Baru” example, the geographic distances explained 24.9% of the variation in FST (the square of the Mantel correlation, rm2 equal to 0.499), whereas the effect of environment was equal to 9.09%. Using a standard multiple regression framework, if the matrices E and D are used as explanatory matrices to explain FST, the overall Rm2 is equal to 0.295. The sum of the rm2 is slightly larger than the overall Rm2 and, therefore, there is a small shared fraction (4.4%). The unique effects of geographic and environmental distances are equal to 0.204 and 0.046, respectively. This result reveals that about half of the small explanatory power of environmental distances was due to spatial patterns (in agreement with the results of the partial correlation shown above).

Finally, it is also possible to generalize the multiple regression approach and evaluate simultaneously the effects of several explanatory matrices, a framework called Multiple Regression on Distance Matrices (MRM; Lichstein, 2007). Using the “Baru” dataset, we can evaluate the “effects” of the explanatory distance matrices (D, E and R) on the genetic divergence estimated by FST. In this case, these matrices explained 32.1% of the variation in genetic divergence, and only the standardized partial regression coefficient of geographic distances was significant at p < 0.001 (p-value for E was equal to 0.111 and for R equal to 0.239). The results are thus similar to all previous Mantel tests that did not show partial effects of the environment or proportion of natural remnants on genetic distances.

By far, the partial test is still the most controversial application of Mantel test, and there has been a long discussion about its statistical performance in terms of Type I error and power (Raufaste and Rousset, 2001, 2002; Castellano and Balletto, 2002; Cushman and Landguth, 2010; Harmon and Glor 2010; Legendre and Fortin, 2010; Guillot and Rousset, 2013). Actually, since its initial applications, some potential problems of low power to detect correlation and inflated Type I error in partial tests have been considered (Oden and Sokal, 1992), and different forms of permutations may provide different results depending on data characteristics (Legendre, 2000). However, some issues emerge when matrices are built upon two variables (transformed into matrices using Euclidean distances) and not multivariate distance matrices per se (such as a Nei genetic distance or pairwise FST). In this case there are more appropriate tools for correlating variables while taking their spatial structure into account (Dormann et al., 2007, Diniz-Filho et al., 2009; Guillot and Rousset, 2013). However, Legendre and Fortin (2010), besides indicating that other approaches have higher statistical power than the Mantel test, wrote that “...the Mantel test should not be used as a general method for the investigation of linear relationships or spatial structures in univariate or multivariate data”, and “its use should be restricted to tests of hypotheses that can only be formulated in terms of distances” (see also Cushman and Landguth, 2010). Likewise, Guillot and Rousset (2013) recently found very high Type I error rates for partial Mantel tests and strongly condemned their use.

Nonetheless simulations showed that other approaches for estimating partial correlation between matrices (i.e., Redundancy Analysis based on Eigenfunction Spatial Analyses - see section below) may also have inflated Type I error rates (Legendre et al., 2005; Peres-Neto and Legendre, 2010). A simple solution to this problem with Type I error was given by Oden and Sokal (1992), who pointed out that when using partial Mantel tests it is important to be conservative and only reject the null hypothesis of no correlation if p is much smaller (say, p = 0.001) than the nominal level of 5%. Until the development of other methods, this overall reasoning should be adopted when using partial Mantel tests.

Mantel Test and Isolation-By-Distance

Many recent studies have interpreted a significant Mantel correlation between G and D as due to Wright’s Isolation-By-Distance (IBD) process. Although this is one possibility, it is hardly the only one (see Meirmans, 2012), and even a correlogram expressing a exponential-like decrease in Mantel correlations may indicate other processes creating patches of genetic variation (see Sokal and Oden, 1978a,b; Sokal and Wartenberg, 1983). Thus, it is not straightforward to link patterns to processes and, in principle, a significant Mantel test or a correlogram pattern only indicates that genetic variability is structured in geographic space. Sokal and Oden (1978b; see also Sokal and Wartenberg, 1983; and Diniz-Filho and Bini, 2012 for a historical review) proposed a more complex framework based on spatial analyses (a combination of univariate correlograms built with Moran’s I spatial correlograms) to infer IBD, but even this framework is not unanimously accepted (see Slatkin and Arter, 1991). However, under the assumption that the processes driving genetic variation is IBD, it is possible to infer demographic and ecological parameters based on the shape of the correlograms (see Epperson, 2003; Hardy and Vekemans, 1999; Vekemans and Hardy, 2004).

Rousset (1997) showed that, under IBD, the regression of FST/(1-FST) against the logarithm of geographic distances would provide a linear relationship with slope b equal to

and intercept a equal to

where N is the population size, σ2 the variance of distance between parent and offspring (4πσ2 is Wright’s neighborhood area in two dimensions), A2 a constant related to the dispersal Kernel, and γe is Euler’s constant (0.5772). In practice, although it is difficult to estimate population size and dispersal distance without further experiments (capture-recapture data, for example), as it is difficult to assume A2 = 0 (Rousset, 1997), the theoretical derivation clearly shows how empirical relationship between matrices can provide insights on IBD parameters.

For the “Baru” dataset, the transformation of both genetic and geographic distances indicates a non-linear relationship (Figure 4), and the model with the transformations proposed by Rousset (1997) is clearly less fit. This result suggests that IBD does not apply in general, and parameter estimation associated with this process may be flawed.

Figure 4.

Relationship between transformed FST and logarithm of geographic distances for the 25 populations of “Baru” tree. Notice that transformation did not produce a linear relationship, supporting previous analyses showing that IBD does not apply in this case.

Alternatives to Mantel Test

Because of the recent discussions on Mantel tests (see above), it is worthy to discuss other strategies for data analysis in the multivariate case. The overall problem in combining genetic data and geographic space, in a broad sense, is to convert the two datasets into a common “format” (i.e., vectors or distance matrices). For example, the discussions on the use of Mantel tests in the bivariate case (the correlation between two variables keeping distance constant, see Guillot and Rousset, 2013) started because space was expressed as distances, so a first idea was to transform genetic variables into distances and use a partial Mantel test (although simpler strategies to deal with spatial structures underlying two variables exist). If the data is multivariate, such as several alleles and loci used to calculate a divergence matrix, the Mantel test can be even more directly applied, because pairwise distances can be intuitively compared using this approach. However, there are other possibilities to deal with the raw data (i.e., allelic frequencies) and, because they are based on ordinations (see Legendre and Legendre, 2012), one can use scores to compare populations and not the original values per se.

The most common current alternative to the Mantel test (and partial Mantel tests) is to ordinate the genetic distances (FST) and compare them with geographic coordinates or other vector representations of geographical distances (e.g., polynomial function of geographic coordinates). Although it is also possible to perform the analyses below based on the 52 allele frequencies directly, this would generate a Euclidean metric (Rogers) in a linear ordination, making a comparison with Mantel tests not exact (although quite close, by considering the high correlation between Nei, Rogers and FST pairwise distances for the “Baru”). So, we applied a Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) to the FST matrix and retained the first five axes based on a broken-stick criterion. We then used these five axes as a response matrix in a series of Redundancy Analysis (RDA) (Legendre and Legendre, 2012), and compared them with the Mantel tests already presented.

First, an RDA was carried out to analyze the spatial patterns of the genetic dataset (as summarized by the first five axes derived from PCoA) using latitude and longitude as explanatory variables. This is a multivariate generalization of the linear trend surface (mTSA) analysis (see Wartenberg, 1985; Bocquet-Appel and Sokal, 1989). The coefficient of determination R2 of the RDA was equal to 0.251 (that of the Mantel test was equal to 0.249). The similarity between these figures is expected by considering previous discussions about the strong linear component of genetic variation revealed by the Mantel correlograms and reflecting past range expansion.

However, the mTSA allows fitting a linear model, describing only broad-scale spatial structures. A polynomial function of the geographic coordinates would capture more complex patterns, but collinearity problems and low statistical power for small sample sizes make this approach less recommended. A more general approach to transform geographic space in a raw data form (i.e., variables x populations, instead of distance matrix) is to apply an eigenfunction analysis of geographic distances (or binary W connections) to obtain “eigenvector maps”, expressing spatial relationships among populations at different spatial scales. There are several versions of this approach (see Griffith and Peres-Neto, 2006; Bini et al., 2009; Landeiro and Magnusson 2011; Diniz-Filho et al., 2009, 2012c). These methods are now collectively called Spatial Eigenfunction Analyses (SEA) and have been extensively used in ecology, and recently also gained attention from landscape geneticists (i.e., Manel et al., 2010; Manel and Holderegger, 2013).

The idea of SEA is to extract eigenvectors from geographic distances and connectivity matrices, and these eigenvectors tend to map the spatial structure among populations at different spatial scales. When allele frequencies or PCoA axes are regressed against these eigenvectors, some of them will tend to describe the spatial patterns in genetic variation. This can be done for single alleles, but here we modeled simultaneously the five axes from the PCoA of FST matrix using an RDA, following a multidimensional approach. One of the main difficulties with this approach is to decide which spatial eigenvectors shall be used in the analyses, and several criteria can be applied. Here we followed Blanchet et al. (2008) and used a forward approach to select spatial eigenvectors. When the five axes derived from PCoA matrix were regressed against the three selected eigenvectors (1, 3 and 5), the RDA R2 was equal to 0.362, slightly higher than the one obtained by mTSA (because it was able to capture more complex spatial structures in genetic data beyond the overall linear trend).

Thus, the Mantel test, mTSA and SEA all showed significant correlations between G and D. The magnitude of spatial pattern for E and R modeled by these different approaches was also similar (see Table 2). However, an interesting application of the ordination approach based on RDA is to evaluate partial relationships, providing thus an alternative to partial Mantel tests (which is important, by considering all discussions on the validity of the partial Mantel test already pointed out). Thus, a PCoA was used to map distances of matrix E and retaining the two axes according to the broken-stick criterion. The RDA also revealed a significant relationship between G and E (with an R2 = 0.215; p < 0.01). By using the partial RDA it is possible to test if the genetic and environmental matrices are actually correlated after the spatial structure of both matrices is taken into account. When defining space by geographical coordinates, in the mTSA approach, the partial R2 between G and E was equal to 0.199 (p < 0.01), thus correlation between genetic and environment remained even when spatial structure (i.e., the linear trend) was taken into account. However, using SEA, the R2 between G and E (controlling for spatial interdependence) decreased to 0.083, which was not statistically significant (p = 0.23). Thus, when geographic space is modeled in a more appropriate way, the result from ordination was similar to that obtained by the Mantel test, which is also consistent with the fact that neutral markers, such as microsatellites, are not expected to be correlated with climatic or environmental variation.

Table 2.

Summary of Mantel and partial Mantel tests applied to “Baru” populations, comparing effects of geographic distance (D), environmental variables (E) and natural remnants (R) into genetic divergence (G) estimated by pairwise FST. Results include Mantel’s correlation r (and r2, for facility of comparison with RDA results). Also provided are the R2 of Redundancy Analysis (RDA), incorporating geographic space by spatial eigenfunction analysis (SEA) and linear multivariate trend surface (mTSA).

| Comparison | Mantel

|

RDA

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | r2 | R2 (SEA) | R2 (mTSA) | |

| GD | 0.499** | 0.249 | 0.360** | 0.250** |

| ED | 0.838** | 0.702 | 0.607** | 0.913** |

| RD | 0.075ns | 0.005 | 0.337** | 0.349** |

| GE|D | −0.248ns | 0.061 | 0.083ns | 0.199** |

| GR|D | −0.223ns | 0.049 | 0.018ns | 0.034ns |

**: p < 0.01;

ns: non-significant at 5%.

Thus, results from RDA were similar to those provided by Mantel tests, both when comparing two matrices and when testing partial relationships (Table 2). Notice, however, that the relationship between G and E is higher for RDA than for the Mantel test (and this relationship actually disappears when D is taken into account). Of course, this particular example does not solve the controversies on partial Mantel tests, and other studies, using simulations, have been performed to better establish the statistical performance of these (and other) techniques. These studies concluded that, although SEA and RDA approaches may have more accurate type I and II errors, under certain conditions they can behave as badly as Mantel tests. Moreover, SEA has a more difficult component, which is the selection of eigenvectors (both in response and explanatory, in our case) to be used in the analyses. A Mantel test is simpler and can be interpreted more directly, and thus may be still valid in many cases. We believe that our empirical results reinforce that when patterns are strong and clear, techniques tend to give comparable results. In all cases, results of partial analyses should be interpreted with caution and, more likely, using the different alternatives to search for a robust and consistent outcome.

Concluding Remarks

Despite recent discussions and criticisms, we believe that the Mantel test can be a powerful approach to analyze multivariate data, mainly if the ecological or evolutionary hypotheses are better (or only) expressed as pairwise distances or similarities, as pointed out by Legendre and Fortin (2010). Even though, an important guideline is to always check the assumptions of linearity and homoscedasticity in the relationships between genetic divergence and other matrices (i.e., geographic distances), because such violations are actually expected under theoretical models, such as IBD. If these violations occur, a global Mantel test may be a biased description of the amount of spatial variation in the data. Mantel correlograms may be useful to overcome these problems and, at the same time, may provide a more accurate and visually appealing description of the spatial patterns in the data. Partial Mantel tests can still be applied, but using a more conservative critical level for defining their significance and, if possible, coupled with ordination and spatial eigenfunction analyses.

Finally, because of the ongoing discussions, it is important that researchers are aware of other possibilities for analyzing data, such as performed here. Although our empirical example with genetic variation in the “Baru” tree does not allow a deep evaluation of the statistical performance of these techniques and comparison with simulation-based studies, it reveals that, as is common in empirical applications, results usually converge. Thus, all these different approaches gave similar estimates of the magnitude of spatial variation in genetic variation in the “Baru” tree in the Cerrado biome, when compared with Mantel test. More importantly, the results are expected based on previous knowledge of the ecological and evolutionary processes underlying such variation.

Acknowledgments

Our research program integrating macroecology and molecular ecology of plants and the DTI fellowship to G.O. has been continuously supported by several grants and fellowships to the research network GENPAC (Geographical Genetics and Regional Planning for natural resources in Brazilian Cerrado) from CNPq/MCT/CAPES and by the “Núcleo de Excelência em Genética e Conservação de Espécies do Cerrado” - GECER (PRONEX/FAPEG/CNPq CP 07-2009). Fieldwork has been supported by Systema Naturae Consultoria Ambiental LTDA. Work by J.A.F.D.-F., L.M.B, M.P.C.T., T.N.S. and T.F.R. has been continuously supported by productivity fellowships from CNPq.

Footnotes

Associate Editor: Alexandre Rodrigues Caetano

References

- Balkenhol N, Waits LP, Dezzani RJ. Statistical approaches in landscape genetics: An evaluation of methods for linking landscape and genetic data. Ecography. 2009;32:818–830. [Google Scholar]

- Bini LM, Diniz-Filho JAF, Rangel TFLVB, Akre TSB, Albaladejo RG, Albuquerque FS, Aparicio A, Araújo MB, Baselga A, Beck J, et al. Coefficients shifts in geographical ecology: An empirical evaluation of spatial and non-spatial regression. Ecography. 2009;32:193–204. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet FG, Legendre P, Borcard D. Forward selection of explanatory variables. Ecology. 2008;89:2623–2632. doi: 10.1890/07-0986.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocquet-Appel JP, Sokal RR. Spatial autocorrelation analysis of trend residuals in biological data. Syst Zool. 1989;38:331–341. [Google Scholar]

- Borcard D, Legendre P. Is the Mantel correlogram powerful enough to be useful in ecological analysis? A simulation study. Ecology. 2012;93:1473–1481. doi: 10.1890/11-1737.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano S, Balletto E. Is the partial Mantel test inadequate? Evolution. 2002;56:1871–1873. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman SA, Landguth EL. Spurious correlations and inference in landscape genetics. Mol Ecol. 2010;19:3592–3602. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz-Filho JAF, Bini LM. Thirty-five years of spatial autocorrelation analysis in population genetics: An essay in honour of Robert Sokal (1926–2012) Biol J Linn Soc. 2012;107:721–736. [Google Scholar]

- Diniz-Filho JAF, Telles MPC. Spatial autocorrelation analysis and the identification of operational units for conservation in continuous populations. Conserv Biol. 2002;16:924–935. [Google Scholar]

- Diniz-Filho JAF, Telles MPC. Optimization procedures for establishing reserve networks for biodiversity conservation taking into account population genetic structure. Genet Mol Biol. 2006;29:207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Diniz-Filho JAF, Nabout JC, Telles MPC, Soares TN, Rangel TFLVB. A review of techniques for spatial modeling in geographical, conservation and landscape genetics. Genet Mol Biol. 2009;32:203–211. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572009000200001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz-Filho JAF, Melo DB, Oliveira G, Collevatti RG, Soares TN, Nabout JC, Lima JS, Dobrovolski R, Chaves LJ, Naves RV, et al. Planning for optimal conservation of geographical genetic variability within species. Conserv Genet. 2012a;13:1085–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Diniz-Filho JAF, Collevatti RG, Soares TN, Telles MPC. Geographical patterns of turnover and nestedness-resultant components of allelic diversity among populations. Genetica. 2012b;140:189–195. doi: 10.1007/s10709-012-9670-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz-Filho JAF, Siqueira T, Padial AA, Rangel TFLVB, Landeiro VL, Bini LM. Spatial autocorrelation allows disentangling the balance between neutral and niche processes in metacommunities. Oikos. 2012c;121:201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Dormann CF, McPherson J, Araújo MB, Bivand R, Bolliger J, Carl G, Davies RG, Hirzel A, Jetz W, Kissling WD, et al. Methods to account for spatial autocorrelation in the analysis of distributional species data: A review. Ecography. 2007;30:609–628. [Google Scholar]

- Dutilleul P. Modifying the t test for assessing the correlation between two spatial processes. Biometrics. 1993;49:305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Epperson BK. Geographical Genetics. Princeton University Press; Princeton: 2003. p. 357. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Inferring Phylogenies. Sinauer Press; New York: 2004. p. 664. [Google Scholar]

- Goslee SC, Urban DL. The ecodist package for dissimilarity-based analysis of ecological data. J Stat Softw. 2007;22:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DA, Peres-Neto P. Spatial modeling in ecology: The flexibility of eigenfunction spatial analyses. Ecology. 2006;87:2603–2613. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[2603:smietf]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillot G, Rousset F. Dismantling the Mantel tests. Meth Ecol Evol. 2013;4:336–344. [Google Scholar]

- Guillot G, Leblois R, Coulon A, Frantz AC. Statistical methods in spatial genetics. Mol Ecol. 2009;18:4734–4756. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy OJ, Vekemans X. Isolation by distance in a continuous population: Reconciliation between spatial autocorrelation analysis and population genetics models. Genetics. 1999;83:145–154. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2540.1999.00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon LJ, Glor RE. Poor statistical performance of the Mantel test in phylogenetic comparative analyses. Evolution. 2010;64:2173–2178. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, Jones PG, Jarvis A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol. 2005;25:1965–1978. [Google Scholar]

- Holsinger KE, Weir BS. Genetics in geographically structured populations: Defining, estimating and interpreting FST. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:639–650. doi: 10.1038/nrg2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landeiro V, Magnusson W. The geometry of spatial analyses: Implications for conservation biologists. Natureza & Conservação. 2011;9:7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Legendre P. Comparison of permutational methods for the partial correlation and partial Mantel tests. J Statist Comput Simul. 2000;67:37–73. [Google Scholar]

- Legendre P, Fortin M-J. Comparison of the Mantel test and alternative approaches for detecting complex multivariate relationships in the spatial analysis of genetic data. Mol Ecol Res. 2010;10:831–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre P, Legendre L. Numerical Ecology. 3rd edition. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2012. p. 990. [Google Scholar]

- Legendre P, Borcard D, Peres-Neto P. Analyzing beta diversity: Partitioning the spatial variation of community composition data. Ecol Monogr. 2005;75:435–450. [Google Scholar]

- Lessa E. Multidimensional analysis of geographic genetic structure. Syst Biol. 1990;39:242–252. [Google Scholar]

- Lichstein J. Multiple regression on distance matrices: A multivariate spatial analysis tool. Plant Ecol. 2007;188:117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Manel S, Holderegger R. Ten years of landscape genetics. Trends Ecol Evol. 2013;28:614–621. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manel S, Poncet BN, Legendre P, Gugerli F, Holderegger R. Common factors drive adaptive genetic variation at different scale in Arabis alpina. Mol Ecol. 2010;19:2896–2907. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly BFJ. The Statistics of Natural Selection. Chapman and Hall; London: 1985. p. 484. [Google Scholar]

- Manly BFJ. Randomization, Bootstrap and Monte Carlo Methods in Biology. Chapman and Hall; London: 1997. p. 399. [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N. The detection of disease clustering and a generalized regression approach. Cancer Res. 1967;27:209–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meirmans PG. The trouble with isolation-by-distance. Mol Ecol. 2012;21:2839–2846. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielke PW. Classification and appropriate inferences for Mantel and Valand’s nonparametric multivariate analysis technique. Biometrics. 1978;34:277–282. [Google Scholar]

- Oden N, Sokal RR. Directional autocorrelation: An extension of spatial correlograms to two dimensions. Syst Zool. 1986;35:608–617. [Google Scholar]

- Oden N, Sokal RR. An investigation of three-matrix permutation tests. J Classif. 1992;9:275–290. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen J, Blanchet JG, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin PR, O’Hara RB, Simpson GL, Solymos P, Stevens MHH, Wagner H. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. 2012. R package version 2.0-5.

- Pellegrino KCM, Rodrigues MT, Waite AN, Morando M, Yassuda YY, Sites JW., Jr Phylogeography and species limits in the Gymnodactylus darwinii complex (Gekkonidae, Squamata): Genetic structure coincides with river systems in the Brazilian Atlantic forest. Biol J Linn Soc. 2005;85:13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Peres-Neto PR, Legendre P. Estimating and controlling for spatial structure in the study of ecological communities. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2010;19:174–184. [Google Scholar]

- Perez SI, Diniz-Filho JAF, Bernal V, Gonzales PN. Alternatives to the partial Mantel test in the study of environmental factors shaping human morphological variation. J Hum Evol. 2010;59:698–703. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing, reference index version 2.15. R Foundation for statistical computing; Vienna, Austria: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Raufaste N, Rousset F. Are partial Mantel tests adequate? Evolution. 2001;55:1703–1705. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousset F. Genetic differentiation and estimation of gene flow from F-statistics under isolation-by-distance. Genetics. 1997;145:1219–1228. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.4.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin M, Arter HE. Spatial autocorrelation methods in population genetics. Am Nat. 1991;138:499–517. [Google Scholar]

- Smouse PE, Long JC, Sokal RR. Multiple regression and correlation extensions of the Mantel test of matrix correspondence. Syst Zool. 1986;35:627–632. [Google Scholar]

- Soares TN, Melo DB, Resende LV, Vianello RP, Chaves LJ, Collevatti RG, Telles MPC. Development of microsatellite markers for the Neotropical tree species Dipteryx alata (Fabacea) Amer J Bot. 2012;99:72–73. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1100377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal RR. Testing statistical significance of geographic variation patterns. Syst Zool. 1979;28:227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Sokal RR, Oden NL. Spatial autocorrelation in biology. 1. Methodology. Biol J Linn Soc. 1978a;10:199–228. [Google Scholar]

- Sokal RR, Oden NL. Spatial autocorrelation in biology. 2. Some biological implications and four applications of evolutionary and ecological interest. Biol J Linn Soc. 1978b;10:229–249. [Google Scholar]

- Sokal RR, Wartenberg DE. A test of spatial autocorrelation analysis using an isolation-by-distance model. Genetics. 1983;105:219–237. doi: 10.1093/genetics/105.1.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal RR, Smouse P, Neel JV. The genetic structure of a tribal population, the Yanomama indians. XV. Patterns inferred by autocorrelation analysis. Genetics. 1986;114:259–287. doi: 10.1093/genetics/114.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal RR, Oden NL, Legendre P, Fortin M-J, Kim J, Vaudor A. Genetic differences among language families in Europe. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1989;79:489–502. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330790406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal RR, Oden NL, Walker J, Waddle DM. Using distance matrices to choose between competing theories and an application to the origin of modern humans. J Hum Evol. 1997;32:501–522. doi: 10.1006/jhev.1996.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vekemans X, Hardy OJ. New insights from fine-scale spatial genetic structure analyses in plant populations. Mol Ecol. 2004;13:921–935. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2004.02076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner HH, Fortin MJ. A conceptual framework for the spatial analysis of landscape genetic data. Conserv Genet. 2013;14:253–261. [Google Scholar]

- Wartenberg D. Canonical trend surface analysis: A method for describing geographic patterns. Syst Zool. 1985;34:259–279. [Google Scholar]

- Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.0-5. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan. (June 20, 2012).

Internet Resources

- WorldClim, http://www.worldclim.org (September 13, 2013).