Abstract

In the current post-genomic era, the genetic basis of pig growth can be understood by assessing SNP marker effects and genomic breeding values (GEBV) based on estimates of these growth curve parameters as phenotypes. Although various statistical methods, such as random regression (RR-BLUP) and Bayesian LASSO (BL), have been applied to genomic selection (GS), none of these has yet been used in a growth curve approach. In this work, we compared the accuracies of RR-BLUP and BL using empirical weight-age data from an outbred F2 (Brazilian Piau X commercial) population. The phenotypes were determined by parameter estimates using a nonlinear logistic regression model and the halothane gene was considered as a marker for evaluating the assumptions of the GS methods in relation to the genetic variation explained by each locus. BL yielded more accurate values for all of the phenotypes evaluated and was used to estimate SNP effects and GEBV vectors. The latter allowed the construction of genomic growth curves, which showed substantial genetic discrimination among animals in the final growth phase. The SNP effect estimates allowed identification of the most relevant markers for each phenotype, the positions of which were coincident with reported QTL regions for growth traits.

Keywords: Bayesian LASSO, nonlinear regression, SNP effects

Introduction

The success of pig production systems, including the evaluation of alternative management and marketing strategies, requires knowledge of the body weight behavior over time, commonly referred to as the growth curve. This knowledge allows the assessment of growth characteristics in actual production situations and translates this information into economic decisions.

Differences among animal growth curves partly reflect genetic influences, with multiple genes contributing at different levels to the overall phenotype. Hence, selection strategies that attempt to modify the growth curve shape to meet demands of the pork market are very relevant. In the current post-genomic era, understanding the genomic basis of pig growth cannot be limited to simply estimating marker effects using body weight at a specific time as a phenotype, but must also consider changes in body weight over time. According to Pong-Wong and Hadjipavlou (2010) and Ibáñez-Escriche and Blasco (2011) this can be done by estimating the marker effects for parameters of nonlinear regression models that are widely used to describe growth curves.

Regardless of the phenotype used, a major challenge in genome-wide selection (GS) is to identify the most powerful statistical methods for predicting phenotypic values based on estimates of marker effects. Since the seminal GS paper by Meuwissen et al. (2001), several studies have compared the efficiency of simple methods, such as the RR-BLUP (Random Regression Blup) (Meuwissen et al., 2001), with more sophisticated methods, such as Bayesian LASSO (BL) (de los Campos et al., 2009). The main difference between these two very popular GS methods is that the first one assumes, a priori, that all loci explain an equal amount of genetic variation, while the second one allows the assumption that each locus explains its own amount of this variation. Although these two methods have already been compared in other studies, so far there has been no comparison of these methods using a major gene, such as the halothane gene in pigs (Fujii et al., 1991), as a marker. In addition, these methods have not yet been applied to the analysis of growth curves in conjunction with nonlinear regression models.

In this study, we compared the accuracies of RR-BLUP and BL for predicting genetic merit in an empirical application using weight-age data from an outbred F2 (Brazilian Piau X commercial) pig population (Silva et al., 2011). In this approach, the phenotypes were defined by parameter estimates obtained with a nonlinear logistic regression model and the halothane gene was considered a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) marker in order to evaluate the assumptions of the GS methods in relation to the genetic variation explained by each locus. Genomic growth curves based on genomic estimated breeding values were constructed and the most relevant SNPs associated with growth parameters were identified.

Material and Methods

The phenotypic data was obtained from the Pig Breeding Farm of the Department of Animal Science, Universidade Federal de Viçosa (UFV), MG, Brazil. A three-generation resource population was created and managed as described by Band et al. (2005). Briefly, two naturalized Piau breed grandsires were crossed with 18 granddams from a commercial line composed of Large White, Landrace and Pietrain breeds, to produce the F1 generation from which 11 F1 sires and 54 F1 dams were selected. These F1 individuals were crossed to produce the F2 population, of which 345 animals were weighed at birth and at 21, 42, 63, 77, 105 and 150 days of age. The use of these animals was reviewed and approved by the Bioethics committee of the Department of Veterinary Medicine (DVT-UFV) in agreement with the Guide to the Care and Use of Experimental Animals of the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

The SNPs used for fine mapping and estimation of marker effects were selected based on their spacing within chromosomes that contained quantitative trait loci (QTL) previously identified in this same population. These markers were distributed as follows: SSC1 (n = 56), SSC4 (n = 54), SSC7 (n = 59), SSC8 (n = 30), SSC17 (n = 25) and SSCX (n = 12), with the average distances (cM) being, respectively, 5.17, 2.37, 2.25, 3.93, 2.68 and 11.0. The animals were genotypes using Golden Gate/VeraCode technology, which provides a robust and flexible platform, in conjunction with a BeadXpress reader from Illumina. A total of 237 markers (236 SNPs plus the halothane gene) were used, with the halothane gene being considered a special marker for reasons explained later.

Five of the nonlinear regression models (Brody, Gompertz, logistic, von Bertalanffy and Richards) most widely used to describe animal growth curves were fitted to the weight-age data using the nls function of R (R Development Core Team, 2011) software. The usefulness of the models was compared based on the goodness of fit, the adjusted coefficient of determination and the residual standard deviation, which showed a relative superiority of the logistic model. This model is given by (Ratkowsky, 1983):

| (1) |

where wij is the animal weight i at age (t)j, α1i is the mature weight (kg), α2i reflects the weight at time t = 0 (birth weight, kg), α3i is a general growth rate (curve slope at the inflection point), and eij is a residual term, assumed to be independent and normally distributed.

Once the parameters estimates of the logistic model for each animal (α̂1i, α̂2i and α̂3i) were obtained, these values were used as dependent variables in a linear model in order to perform a pre-correction for fixed effects (sex and lot). These pre-corrected observations (residual plus general mean) were used as phenotypes in the GS regression models in order to identify SNP marker effects. This is a well-known two-step procedure (Varona et al., 1999; Pong-Wong and Hadjipavlou, 2010) in which, in the first step, a growth curve is fitted separately to the data of each animal and, in the second step, the growth curve parameter estimates from the previous step are taken as records. The main advantage of this method is its statistical simplicity since the growth model and GS model are fitted independently; however, more sophisticated methods, such as Bayesian joint analysis (Varona et al., 1999) also have been used in GS (Ibáñez-Escriche and Blasco, 2011) and produced good results.

With respect to GS, the phenotypic outcomes (pre-corrected phenotypes for fixed effects), denoted from now on by yi (i = 1, 2, ..., 345), were regressed on marker covariates xik (k = 1, 2, ..., 237) following the regression model proposed by Meuwissen et al. (2001):

| (2) |

where yi is the phenotypic observation of animal I, μ is the general mean, βk is the effect of marker k and ei the residual term, ei ∼ N(0, ), in which are included the dominance and epistatic effects. In this model, xik take the values 2 – 2pk, 1 – 2pk and 0 – 2pk for the SNP genotypes AA, Aa and aa at each locus k, respectively, where pk is the allele frequency at the locus k. Using matrix notation, this GS model can be rewritten as:

| (3) |

where 1′ and I are, respectively, a unit vector and an identity matrix with dimensions 345, where y = [y1, y2, ..., y345]’345x1, Xk = [x1k, x2k, ..., x345k]’345x1 and e = [e1, e2, ..., e345]’345x1.

The first method used to fit the GS model was RR-BLUP (Meuwissen et al., 2001), in which βk is considered a random marker effect, βk ∼ N(0, ) assuming that (i.e., all loci explain an equal amount of genetic variation). This method was implemented using an equivalent model (called G-BLUP) in the R software (R Development Core Team, 2011) by package rrBLUP (Endelman, 2011) and the function mixed.solve, which solves a mixed model equation of the form:

where is the vector of genomic breeding values. Thus, admitting the additive genetic variance ( ) given by (Habier et al., 2007) it can be shown that:

with G being the so-called genomic relationship matrix. With this approach, it is possible to work through the well-known Henderson mixed model equation using the REML estimation method, which provides estimates of variance components for calculating the heritability by . Since , with X = [X1|X2|…|X237]345×237 and β̂ = [β1,β2,…,β237]237×1, the estimated marker effects vector can be obtained by the simple normal equation system of β̂ = (X’X)− (X’û).

The second used method was BL (de los Campos et al., 2009), which is a more general method because it assumes that each locus explains its own amount or contribution to the overall variation. This method has been used to solve multicollinearity problems and may also be employed in situations where there are more markers (covariates) than observations. The BL is a penalized Bayesian regression procedure, whose general estimator is given by where λ is the regularization parameter. When λ = 0 there is no regularization and when λ > 0 there is a shrinkage of the marker effects toward zero, with the possibility of setting some identically equal to zero, resulting in a simultaneous estimation and variable selection procedure. This characteristic of the BL method is especially useful for F2 populations in which larger haplotype blocks with many redundant SNPs in each block are expected; the latter implies multicollinearity that impairs fitting of the model (Eq. (2)). Thus, the regularization imposed by BL reduces some redundant SNPs to zero, thereby bypassing the problem of multicollinear SNPs in haplotype blocks. The package BLR (de los Campos et al., 2009; Pérez et al., 2010) of R software was used for this analysis. This package assumes that the joint prior distribution of marker effects (β1, β2, ..., β237) is , where , is the residual variance, with a scaled inverse χ2 prior distribution, and is the scale parameter related to each marker. The BLR method also assumes that the joint prior distribution for the scale parameters ( ) is the product of exponential distributions, , and that the λ prior distribution is Gamma(ν1, ν2). The BL method was implemented using 10,000 MCMC (Markov chain - Monte Carlo) iterations, with a burn-in and thin of 5,000 and 2 iterations, respectively. The plausibility of these values was assessed for each MCMC chain separately using Raftery-Lewis and Geweke convergence diagnostics in boa (Smith, 2007) R package. Since the BLR method provides the posterior mean (β̂k) as a marker effect estimate, the vector of the genomic estimated breeding values (GEBV) was obtained as . Using this approach, the additive genetic variance needed to calculate h2 was because each locus presents a particular variance ( ).

As stated earlier, the main difference between RR-BLUP and BL is the assumption related to the equality of marker effects variance, and some studies has used simulated (Meuwissen et al., 2001) and real (Moser et al., 2009) data to verify this assumption. However, to date no studies have applied this assumption to real scenarios in which known major genes are postulated as markers. For this reason, the well-known halothane gene that affects growth traits (Miller et al., 2000) was included in the analysis as a simple marker to provide a real situation of unequal marker effects variances. Of the 345 animals, 291 (84.3%) and 54 (15.7%) had the normal (HALNN) and heterozygous (HALNn) halothane genotype, respectively; none of the animals had a double recessive genotype (HALnn). The allelic frequencies of N and n were 7 and 93%, respectively.

The leave-one-out cross-validation was used to compare RR-BLUP and BL. For this, the original data set with 345 animals was divided into 345 training data sets (D−i) of 344 individuals, D−1, D−2, ..., D−345, with each containing marker and phenotypic information of all the animals, except for animal −i. With this approach, there was no loss of generality for each method and each phenotype. In these analyses, the predicted genomic breeding value of animal i for each trait (parameter estimates α̂1, α̂2 and α̂2 of the logistic model) was calculated as ûi = Xiβ̂ −i, where Xi denotes the SNP genotype vector of animal i and β̂−1 denotes the estimated marker effects vector from the analysis that considered all animals, except animal i. All codes related to the leave-one-out cross-validation implemented for the RR-BLUP and BL method are provided in the Supplementary Material.

The vector containing all predicted values was û = [û1,..., û345 ] and the accuracy (r) used to measure the efficiency of RR-BLUP and BL was given by , where ryû is the correlation between observed phenotype (y) and û, and h2 is the estimated heritability. A linear regression with y as the dependent variable and û as the independent variable was used to screen for bias produced by each method; in this case, a regression coefficient of one indicated an unbiased method.

Once the most appropriate method (RR-BLUP or BL) had been chosen, the vectors of the estimated genomic breeding values for each parameter of the logistic growth curve where obtained, assuming that ûα̂1=[û α̂11,..., û α̂1345], ûα̂2=[û α̂2345,..., û α̂2345] and, ûα̂3=[û α̂31,..., û α̂3345]. Subsequently, the “genomic growth curve” for each animal could be estimated using the relationship:

| (4) |

where ŷij is the genomic breeding value of each animal i for weight at each age (tij) of interest j (even for no observed ages), μα̂1, μα̂2 and μα̂3 are the average of each phenotype (parameter estimates for the logistic model) and ûα̂1i, ûα̂2i and ûα̂3i are the GEBVs for these phenotypes.

Results and Discussion

Table 1 shows the performance of BL and RR-BLUP. Overall, the two methods provided highly accurate values (mean overall accuracy: 0.69 ± 0.09), as shown by the strong association between the phenotypic assessment and the true breeding values. To date, there has been no evaluation of the accuracy of genomic selection for growth traits in pigs using real data, although Akanno (2012) reported a simulation study in which a performance trait (average daily gain) was simulated for different populations. In this simulation, the so-called synthetic population, which was similar to the F2 population of the present study, showed an accuracy of 0.61.

Table 1.

Accuracy and bias estimates for the Bayesian LASSO (BL) and RR-BLUP genomic selection methods used to determine the logistic growth curve parameters of an F2 Piau X commercial pig population evaluated from birth to 150 days of age.

| Phenotypes | Method | Accuracy | Regression coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mature weight (α1) | RR-BLUP | 0.72 | 1.56 |

| BL | 0.86 | 1.39 | |

| Birth weight (α2) | RR-BLUP | 0.61 | 1.31 |

| BL | 0.68 | 1.26 | |

| Growth rate (α3) | RR-BLUP | 0.62 | 1.39 |

| BL | 0.70 | 1.29 |

Comparison of the two methods showed that the BL method yielded more accurate values than RR-BLUP for all of the phenotypes. The mean accuracy of BL (0.70 ± 0.09) was greater than for RR-BLUP (0.62 ± 0.06), indicating that in a real data set in which one locus is known to have a larger effect (in this case, the halothane gene) the BL property of assuming different variances for markers ensures greater efficiency in genomic selection. Although both methods underestimated the breeding values, i.e., the regression coefficient estimates between the observed and predicted phenotypes were slightly greater than 1.0, for the BL method these coefficients were closer to unity for all phenotypes (indicating low bias) when compared to the corresponding values for RR-BLUP. These findings agreed with those of Ogutu et al. (2012), who used a simulated data set to show that LASSO type regressions were more efficient than RR-BLUP for genomic selection because they provided more accurate and less biased predictions.

Table 1 also shows that the accuracy of the differences between the two methods was more pronounced for the trait mature weight (α1) than for the traits birth weight (α2) and growth rate (α3). This finding provides an indirect indication that the genetic architecture of α1 is possibly more influenced by loci that exert larger effects, such as the halothane gene, than the other two traits. This conclusion reflects the fact that BL works better than RR-BLUP when the assumption of an equal contribution of genetic variance in the latter model is violated, as was the case here with the large-effect halothane gene that was used as a marker.

The effect of the halothane gene on estimates of growth curve parameters has not been examined before and this precludes a direct assessment of the effects of this major gene on mature weight. However, Band et al. (2005) observed a significant effect of the halothane gene on weight at 105 days of age (W105) in animals from this same population (F2 Piau X commercial). These authors also evaluated the weight at birth in relation to parameter α1 and the average daily gain in relation to parameter α3. The halothane gene had a significant effect only on W105, indicating that this gene has a greater influence on final weight than on other performance traits.

In summary, the results in Table 1 indicate a superiority of BL in providing accurate estimates and suggest that this method can be recommended for estimating SNP effects and GEBV vectors. However, before using these vectors to select markers and animals it is important to estimate heritabilities and genetic correlations (Table 2) in order to assess whether the three traits (α1, α2 and α3) are really relevant in a breeding program.

Table 2.

Heritabilities (diagonal) and genetic correlations (above the diagonal) for the parameters α1, α2 and α3 estimated by the Bayesian LASSO genomic selection method from the logistic growth curve of an F2 Piau X commercial pig population evaluated from birth to 150 days of age.

| Phenotypes

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1 | α2 | α3 | ||

| Phenotypes | α1* | 0.42 | −0.45 | −0.69 |

| α2 | - | 0.34 | 0.92 | |

| α3 | - | - | 0.36 | |

Mature weight (α1), birth weight (α2) and growth rate (α3).

The high values of h2 (estimated with the BL method) in Table 2 indicate that these traits can be a viable alternative for pig breeding in which the aim is to produce efficient high growth animals. However, direct selection for high α1 implies a selection for low α3 (as indicated by the high negative genetic correlation, −0.69, between these two parameters), i.e., in general terms such selection will result in less precocious animals (low growth rate) with a larger body size at maturity. On the other hand, direct selection for high α 3 can result in more precocious animals with high α2 (birth weight) but low maturity weight (α1). This negative correlation is expected and has been reported in most studies of growth curves and animal breeding, e.g., Koivula et al. (2008) in pigs, Mignon-Grasteau et al. (1999) in chickens and Forni et al. (2007) in beef cattle.

In practical terms, in pig breeding it is better to select for high growth rate (α3) since slaughter is occurs at a standard slaughter weight (∼65 kg for this F2 Piau X commercial population). As a result, the time to slaughter will be significantly lower with a high growth rate, resulting in lower production costs because the slaughter weight is practically the same for all animals (65 kg), with the difference between them reflecting the time required to reach this standard weight. Thus, animals slaughtered at an early age will generate substantially lower feeding costs. The high positive correlation between α3 and α2 means that young pigs do not show a loss in early growth and consequently guarantees good nutrition and health for subsequent growth phases.

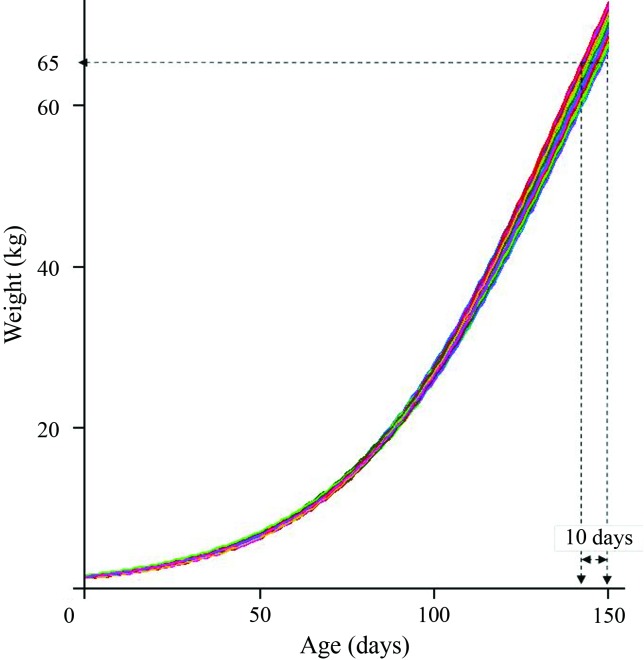

As mentioned earlier, the main focus of this paper was to construct genomic growth curves using the genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) for each parameter of a logistic growth curve (Eq. (4)). Figure 1 shows the genomic growth curve for each animal of the F2 population.

Figure 1.

Genomic growth curves for 345 pigs of an F2 Piau X commercial outbred population from birth to 150 days of age.

The sigmoidal behavior of the curves in Figure 1 was ensured by the average estimates of the growth curve parameters (μα̂1, μα̂2 and μα̂3) and the GEBVs (ûα̂1i, ûα̂2i and ûα̂3i); the latter parameters do not predict this behavior as they may have positive or negative values and are thus outside the limits of the logistic model. The estimates for μα̂1, μα̂2 and μα̂3 were, respectively, 118 kg, 1.4 kg and 0.03 kg/day. There are no data in the literature regarding maturity weight (μα̂1) of the present F2 population because the animals are slaughtered at a live weight of 60–65 kg.

One of the advantages of nonlinear growth curve models (such as the logistic curve) is the ability to predict maturity weight using partial weight-age data, i.e., it is possible to estimate the maturity weight before this weight is reached. The value observed here (118 kg) was lower than in other populations such as Yorkshire pigs (201 kg; Koivula et al., 2008) and 4-way-cross pigs (160 kg; Kusec et al., 2007). This lower weight reflects the characteristically small body size of the Piau breed compared to commercial breeds. The estimated growth rate (μα̂3) (0.03 kg/day) was higher than that reported by Koivula et al. (2008) (0.016 kg/day) and lower than that reported by Kusec et al. (2007) (0.05 kg/day) for Yorkshire pigs and commercial crosses, respectively. Kusec et al. (2007) also reported estimates for the time until maximum gain (time to inflection point), which were ∼120 and 105 days, respectively, for intensive and restrictive feeding systems. In summary, even though the values cited above were obtained in different populations, the comparisons nevertheless provide a useful means of obtaining a general characterization of the growth patterns in the F2 population. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, there are no data on the growth behavior of this experimental population, which was initially developed to combine the precocity of commercial lines with the resistance and fat attributes of Piau, a native Brazilian breed.

From a genetic point of view, Figure 1 shows that the weight differences among GEBVs were accentuated over time such that the genetic variance for weight increased with age. This finding may be related to the greater heritability of mature weight (α1) compared to birth weight (α2) (Table 2) since this value is directly proportional to genetic variance for a given value of residual variance. Similar curves can be obtained using other approaches, e.g., random regression (Meyer, 1998), but in the present study a different approach was used in which (1) the plotted values were GEBVs that had been estimated by a sophisticated method (Bayesian LASSO) that simultaneously considered regularization and variable selection (SNP markers) and (2) the use of a nonlinear (logistic) growth model allowed estimation of the genetic parameters for traits with direct biological interpretation, e.g., maturity weight and growth rate, that could not been estimated by random regression. In practical terms, Figure 1 shows that the greatest genetic difference (based on GEBV) among animals at slaughter was 10 days since the animals were killed at a live weight of ∼65 kg.

Since there have been no reports on QTL detection for the three phenotypes considered in this study and since genomic selection is based on SNP marker estimates, the 5% most relevant SNPs (12 SNPs out of 237 SNPs) for each phenotype (α1, α2 and α3) were used to assess whether their chromosomal positions coincided with others already reported in the literature as being QTLs related to general growth traits. Table 3 shows these selected SNP markers and the absolute values of their estimated effects and chromosomal positions in cM.

Table 3.

Absolute values of the estimated effects of the 5% most relevant SNPs on parameters (α1, α2 and α3) determined from the logistic growth curve of an F2 Piau X commercial pig population evaluated from birth to 150 days of age. SNPs shaded in gray correspond to putative QTLs based on previous literature reports (see text for details).

| Phenotype | SNP marker | Estimated effect (abs) | Chromosome | Position (cM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mature weight (α1) | HALOTANO | 0.9114 | SSC6 | 112.0 |

| ALGA0042216 | 0.0148 | SSC7 | 60.4 | |

| ALGA0099785 | 0.0092 | SSCX | 35.1 | |

| ALGA0095662 | 0.0092 | SSC17 | 45.2 | |

| ALGA0024031 | 0.0084 | SSC4 | 20.2 | |

| ALGA0039607 | 0.0080 | SSC7 | 26.4 | |

| ALGA0098944 | 0.0080 | SSCX | 0.06 | |

| ALGA0042327 | 0.0078 | SSC7 | 65.5 | |

| ALGA0111404 | 0.0076 | SSCX | 100.7 | |

| ALGA0026446 | 0.0067 | SSC4 | 85.0 | |

| ALGA0044519 | 0.0066 | SSC7 | 115.2 | |

| ALGA0000022 | 0.0065 | SSC1 | 0.3 | |

|

| ||||

| Birth weight (α2) | ALGA0010089 | 0.0169 | SSC1 | 153.3 |

| ALGA0049219 | 0.0152 | SSC8 | 55.0 | |

| ALGA0021973 | 0.0132 | SSC4 | 0.3 | |

| MARC0051258 | 0.0110 | SSCX | 112.2 | |

| ALGA0044984 | 0.0098 | SSC7 | 120.6 | |

| ALGA0049546 | 0.0097 | SSC8 | 60.0 | |

| ALGA0029483 | 0.0092 | SSC4 | 123.2 | |

| ALGA0025813 | 0.0087 | SSC4 | 70.3 | |

| ALGA0021974 | 0.0084 | SSC4 | 0.3 | |

| ALGA0006708 | 0.0084 | SSC1 | 141.3 | |

| ALGA0047440 | 0.0081 | SSC8 | 15.0 | |

| ALGA0027861 | 0.0079 | SSC4 | 105.0 | |

|

| ||||

| Growth rate (α3) | ALGA0047440 | 0.000180 | SSC8 | 15.0 |

| ALGA0010089 | 0.000134 | SSC1 | 153.3 | |

| MARC0051258 | 0.000118 | SSCX | 112.2 | |

| ALGA0029483 | 0.000076 | SSC4 | 123.3 | |

| ALGA0006708 | 0.000064 | SSC1 | 141.4 | |

| ALGA0093254 | 0.000059 | SSC17 | 10.3 | |

| ALGA0037853 | 0.000056 | SSC7 | 0.4 | |

| ALGA0006721 | 0.000051 | SSC1 | 142.0 | |

| ALGA0047444 | 0.000049 | SSC8 | 15.2 | |

| ALGA0029781 | 0.000049 | SSC4 | 127.9 | |

| ALGA0026787 | 0.000049 | SSC4 | 90.3 | |

| ALGA0050287 | 0.000048 | SSC8 | 66.5 | |

The SNPs with the greatest effects on α1 were located mainly on chromosomes SSC6, SSC7, SSC17 and SSCX, with particular emphasis on the magnitude of the effect of the halothane gene (0.9114) on this phenotype, as already mentioned for Table 1. The position of marker ALGA0042216 at SSC7 (60.4 cM) agreed with Yue et al. (2003), who found a significant QTL for weight at slaughter at position 65.2 cM in crosses between Meishan (M), Pietrain (P) and European Wild Boar (W). Pierzchala et al. (2003), using a population similar to those studied by Yue et al. (2003), found a significant QTL for weight at slaughter at position 51.1 cM of SSC17, i.e., close to position 45.2 cM for marker ALGA0095662. In general, in the absence of QTL detection for mature weight (α1), these references to weight at slaughter may be useful for validating the relevance of the identified SNPs for this phenotype.

In relation to trait α2, other studies have identified QTLs associated with birth weight at positions close to those of SNPs indicated in Table 3. Su et al. (2002) analyzed data from a Large White (LW) x M intercross population and found a significant QTL at position 153 cM of SSC1, which coincided with the position of marker ALGA0010089. Cepica et al. (2003) used F2 families based on crosses of M, W and P breeds and identified a significant QTL at position 117 cM of SSCX, close to the position of marker MARC0051258 (112.2 cM).

With respect to phenotype α3, the SNPs positions in Table 3 were compared with significant QTL positions for the trait average daily gain (ADG), which is frequently mentioned in the literature and is highly related to the estimated growth (α3) rate in the present study. The position of marker ALGA0047440 on SSC8 (15 cM) was close to position 10 cM reported by de Koning et al. (2001) who used data from an experimental cross between M and Dutch commercial lines. Sanchez et al. (2006) used data from a backcross M x LW and found a significant QTL at position 143 cM of SSC1, close to marker ALGA0010089 (1553.3 cM).

Five SNPs (ALGA0006708, ALGA0010089, ALGA0029483, ALGA0047440 and MARC0051258) in Table 3 were simultaneously among the most important for α2 and α3, which could perhaps explain the greater genetic correlation between birth weight and growth rate in Table 2. In summary, the relevant SNPs listed in Table 3 were associated with QTL regions for growth traits previously reported in the literature. This finding indicates that these regions can be exploited molecularly to enhance pig breeding.

As a general conclusion, Bayesian LASSO provided more accurate values than RR-BLUP for all of the phenotypes evaluated and worked best when the assumption of an equal contribution to genetic variance was violated, e.g., when the halothane major gene was used as a marker in this study. The GEBV vectors allowed the construction of genomic growth curves that revealed substantial genetic discrimination among animals in the final phase of growth. Estimates of the effects of SNPs allowed identification of the most relevant markers for each phenotype, the positions of which coincided with already well-known QTL regions for growth traits.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by CNPq (grant no. 473601/2010-9) and FAPEMIG (grant no. PPM-00483-11).

Footnotes

Associate Editor: Louis Bernard Klaczko

References

- Akanno EC. Genome-Wide Selection Program for Improvement of Indigenous Pigs in Tropical Developing Countries. Guelph University Press; Guelph: 2012. p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- Band GO, Guimarães SEF, Lopes PS, Peixoto JO, Faria DA, Pires AV, Figueredo FC, Nascimento CS, Gomide LAM. Relationship between the Porcine Stress Syndrome gene and carcass and performance traits in F2 pigs resulting from divergent crosses. Genet Mol Biol. 2005;28:92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cepica S, Reiner G, Bartenschlager H, Moser G, Geldermann H. Linkage and QTL mapping for Sus scrofa chromosome X. J Anim Breed Genet. 2003;120:144–151. [Google Scholar]

- de los Campos G, Naya H, Gianola D, Crossa J, Legarra A, Manfredi E, Weige K, Cotes JM. Predicting quantitative traits with regression models for dense molecular markers. Genetics. 2009;182:375–385. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.101501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endelman JB. Ridge regression and other kernels for genomic selection with R package rrBLUP. Plant Genome. 2011;4:250–255. [Google Scholar]

- Forni S, Piles M, Blasco A, Varona L, Oliveira HN, Lôbo RB, Albuquerque LG. Analysis of beef cattle longitudinal data applying a nonlinear model. J Anim Sci. 2007;85:3189–3197. doi: 10.2527/jas.2006-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii J, Otsu K, Zorzato F, De Leon S, Khanna VK, Weiler JE, O’Brien PJ, Maclennan DH. Identification of a mutation in the porcine ryanodine receptor associated with malignant hyperthermia. Science. 1991;253:448–451. doi: 10.1126/science.1862346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habier D, Fernando RL, Dekkers JCM. The impact of genetic relationship information on genome-assisted breeding values. Genetics. 2007;177:2389–2397. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.081190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez-Escriche N, Blasco A. Modifying growth curve parameters by multitrait genomic selection. J Anim Sci. 2011;89:661–668. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivula M, Sevón-Aimonen ML, Strandén I, Matilainen K, Serenius T, Stalder KJ, Mäntysaari EA. Genetic (co)variances and breeding value estimation of Gompertz growth curve parameters in Finnish Yorkshire boars, gilts and barrows. J Anim Breed Genet. 2008;125:168–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0388.2008.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koning DJ, Rattink AP, Harlizius B, Groenen MAM, Brascamp EW, van Arendonk JAM. Detection and characterization of quantitative trait loci for growth and reproduction traits in pigs. Livest Prod Sci. 2001;72:185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Kusec G, Baulain U, Kallweit E, Glodek P. Influence of MHS genotype and feeding regime on allometric and temporal growth of pigs assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Livest Sci. 2007;110:89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Meuwissen THE, Hayes BJ, Goddard ME. Prediction of total genetic value using genome wide dense marker maps. Genetics. 2001;157:1819–1829. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.4.1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K. Estimating covariance functions for longitudinal data using a random regression model. Genet Sel Evol. 1998;30:221–240. [Google Scholar]

- Mignon-Grasteau S, Beaumont C, Le Bihan-Duval E, Poivey JP, De Rochambeau H, Richard FH. Genetic parameters of growth curve parameters in male and female chickens. Br Poultry Sci. 1999;40:44–51. doi: 10.1080/00071669987827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KD, Ellis M, McKeith FK, Wilson ER. Influence of sire line and halothane genotype on growth performance, carcass characteristics, and meat quality in pigs. Can J Anim Sci. 2000;80:319–327. [Google Scholar]

- Moser G, Tier B, Crump RE, Khatkar MS, Raadsma H. A comparison of five methods to predict genomic breeding values of dairy bulls from genome-wide SNP markers. Genet Sel Evol. 2009;41:56–64. doi: 10.1186/1297-9686-41-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogutu JO, Schulz-Streeck T, Piepho HP. Genomic selection using regularized linear regression models: ridge regression, LASSO, elastic net and their extensions. BMC Proc. 2012;6:S10. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-6-S2-S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez P, de los Campos G, Crossa J, Gianola D. Genomic-enabled prediction based on molecular markers and pedigree using the Bayesian linear regression package in R. Plant Genome. 2010;3:106–116. doi: 10.3835/plantgenome2010.04.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierzchala M, Cieslak D, Reiner G, Bartenschlager H, Moser G, Geldermann H. Linkage and QTL mapping for Sus scrofa chromosome 17. J Anim Breed Genet. 2003;120:132–137. [Google Scholar]

- Pong-Wong R, Hadjipavlou GA. A two-step approach combining the Gompertz growth with genomic selection for longitudinal data. BMC Proc. 2010;4:S4. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-4-s1-s4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratkowsky DA. Nonlinear Regression Modeling. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1983. p. 276. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez MP, Riquet J, Iannuccelli N, Gogue J, Billon Y, Demeure O, Caritez JC, Burgaud G, Feve K, Bonnet B, et al. Effects of quantitative trait loci on chromosomes 1, 2, 4, and 7 on growth, carcass, and meat quality traits in backcross Meishan x Large White pigs. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:526–537. doi: 10.2527/2006.843526x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva FF, Rosa GJM, Guimarães SEF, Lopes PS, de los Campos G. Three-step Bayesian factor analysis applied to QTL detection in crosses between outbred pig populations. Livest Sci. 2011;42:210–215. [Google Scholar]

- Smith BJ. boa: An R package for MCMC output convergence assessment and posterior inference. J Stat Softw. 2007;21:1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Su YH, Xiong YZ, Zhang Q, Jiang SW, Yu L, Lei MG, Zheng R, Deng CY. Mapping quantitative trait loci for fat deposition in carcass in pigs. Acta Genet Sin. 2002;29:607–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varona L, Moreno C, Garcia-Cortés LA, Yague G, Altarriba J. Two-step vs. joint analysis of Von Bertalanffy function. J Anim Breed Genet. 1999;116:331–338. [Google Scholar]

- Yue G, Stratil A, Cepica S, Schröffel J, Jr, Schröffelova D, Fontanesi L, Cagnazzo M, Moser G, Bartenschlager H, Rei G. Linkage and QTL mapping for Sus scrofa chromosome 7. J Anim Breed Genet. 2003;120:56–65. [Google Scholar]

Internet Resources

- R Development Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna: 2011. http://www.R-project.org/ (27 July 2011). [Google Scholar]