Abstract

A recent report1 demonstrates that a subset of RGG motif proteins can bind translation initiation factor eIF4G and repress mRNA translation. This adds to the growing number of roles RGG motif proteins play in modulating transcription, splicing, mRNA export and now translation. Herein, we review the nature and breadth of functions of RGG motif proteins. In addition, the interaction of some RGG motif proteins and other translation repressors with eIF4G highlights the role of eIF4G as a general modulator of mRNA function and not solely as a translation initiation factor.

Keywords: translation initiation, RGG motif, Sbp1, eIF4E, mRNA decay, eIF4G, Npl3, re-entry to translation, arginine methylation, decapping

Regulation of Translation by RGG Motif-Containing Proteins

Regulation of translation and mRNA decay play crucial roles in variety of cellular processes, including development, learning and memory, stem cell maintenance and differentiation.2 Misregulation of translation and mRNA decay also contributes to a number of disease conditions, such as cancer,3,4 fragile X syndrome,5 β-thalassemia6 and Duchene muscular dystrophy.6

Translation and mRNA decay are often competing functional states of mRNA. Degradation of mRNA in eukaryotes generally begins with shortening of the 3′-poly(A) tail by the deadenylases7 followed by removal of the 5′-cap. A decapped mRNA is susceptible to 5′-3′ decay and is degraded by Xrn1 exoribonuclease. 8 The 5′-cap and 3′-poly(A)-tail of the mRNA are sites of competition9 between decay enzymes (e.g., Dcp1/2 and deadenylases) and translation initiation factors (e.g., eIF4E/4G and Pab1). Hence, perturbation of either mRNA translation or decay often affects regulation of the other process.

Translationally repressed mRNAs can return back to translation.10,11 Regulation of gene expression by maintaining mRNAs in a translationally repressed state for re-entry to translation has been observed in yeast, worm, fly and humans.12,13 Repressed mRNAs primed for re-entry to translation need to be protected from the degradation machinery. Understanding how mRNAs attain a translationally repressed state wherein they are protected from degradation is an important issue.

Evidence in literature suggests that two kinds of general mechanisms operate to stably store mRNAs when not being translated. During stress responses, where translation is repressed for most mRNAs, the decay enzymes appear to be broadly inhibited for deadenylation, and to some extent decapping is slowed down in both yeast and mammalian cells.14,15 Conversely, for specific mRNAs, the decay enzymes can be inhibited by forming an mRNP wherein translation is blocked and the poly (A) tail or cap is sequestered away from the degradative enzymes. One example of this mechanism is the Drosophila eIF4E-binding protein CUP that represses translation by binding to eIF4E on the mRNA, thus also protecting the cap from the decapping enzyme.16

We recently reported the role of decapping activator Scd6 in repressing translation. Scd6 is a conserved protein with an N-terminal Lsm domain, a central FDF domain and a C-terminal RGG motifcontaining domain. Scd6 and its various orthologs modulate translation and/or decay, but the mechanism was not known.17 Our results demonstrate that Scd6 prevents the formation of 48S pre-initiation complex by binding eIF4G through its RGG motif.1 The repressed mRNAs have an intact cap-binding complex consisting of eIF4E-4G-4A and Pab1. Such a mechanism has implications in stable storage of mRNA, discussed later in this article.

Interestingly, the RGG motif has emerged as an eIF4G-binding motif in wider range of RGG motif-containing proteins. Besides Scd6, three other RGG motif proteins Sbp1,1 Npl3 1 and Ded1 18 bind eIF4G in vivo and in vitro to repress translation through their RGG motifs. Moreover, the RGG motif-containing protein Nsr1 binds eIF4G in vivo and in purified form and represses translation (Rajyaguru P and Parker R, unpublished observation). It is interesting to note that proteins L13a19 and Khd1,20 which also target eIF4G to repress translation, contain RGG-/RGX motif. The functional significance of RGG motifs in these proteins is not understood.

Taken together, these results identify a role for a subset of RGG motif-containing proteins in determining mRNA fate through their ability to bind eIF4G and subsequently repress translation. A variety of RNA-binding proteins involved in RNA metabolism contain RGG motifs.21 Consistent with this observation, RGG motifs have emerged as key players in orchestrating post-transcriptional gene regulation. This review explores and hypothesizes functional significance of RGG motifs in mRNA translation/decay and its regulation through arginine methylation.

RGG Motif Proteins: Functions and Regulation

RGG motif proteins are defined by single or multiple-RGG/RGX motifs. Scd6 for example contains eight repeats of -RGX with one RGG repeat. Proteins containing RGG motifs have been implicated in cellular processes, including transcription, splicing and mRNA export, and affect biological processes such as synaptic plasticity, genome defense, germ-line development and nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling (Table 1). The role of RGG motif proteins can be due to direct interactions with either proteins or RNA (Table 1). Such interactions can be charge-based, since the arginine residues are positively charged.

Table 1.

RGG motif proteins and their biological functions

| Function | Protein | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription | Npl323 | Methylation promotes elongation by releasing Tho2 from Npl3-Tho2 complex |

| Splicing | Sm proteins31–33 | Arginine methylation increases the affinity of the Sm proteins (SmD1, SmD3 and SmB) for SMN complex |

| Nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling | hnRNPs34 (Mammals) Hrp1, Npl324 (Yeast hnRNP) |

Arginine methylation of RGG motif proteins promotes import into the nucleus Arginine methylation of RGG motif proteins promotes export from the nucleus |

| Translation | Scd6,1 Npl3,1 Sbp11 & Ded118 | RGG motif promotes interaction with eIF4G to repress translation by inhibiting 48S formation |

| Synaptic plasticity | FMRP35 | RGG motif promotes binding to polyribosomes and G-quadraplex RNAs |

| DNA damage repair | MRE 1136 | RGG motif is required for association with nuclear structures and for the exonuclease activity |

| Germ-cell specification | Sm proteins,37 PIWI proteins38 | Methylated arginines of SmB and PIWI proteins are ligands for Tudor domain protein |

| Genome defense from retro-transposons | PIWI proteins38 | Methylated arginines are ligands for binding of Tudor-domain proteins |

| T-cell signaling | NIP4539 | Arginine methylation promotes interaction with transcription factor NFAT leading to expression of cytokine genes |

| Viral pathogenesis | L4-100K40 | Arginine methylation important for efficient viral replication |

| Signal transduction | G3BP241 | Arginine methylation mediates Wnt signaling by promoting LRP6 phosphorylation |

An unsolved issue is the regulation of RGG motif protein interaction with other proteins and/or RNA. RGG motifs are known substrates for arginine methylation catalyzed by methyltransferases that are conserved from yeast to humans, suggesting that methylation might play a role in modulating these specific interactions. Evidence that arginine methylation of proteins is important comes from the observation that mouse knockouts of PRMT1 (the major arginine methyltransferases) are embryonic lethal.22 Hmt1 (yeast ortholog of PRMT1) regulates mRNA export, transcription elongation and termination through the activity of its substrate Npl3.23,24

Arginine methylation is probably most important in modulating RNA biogenesis and function, since RNA binding proteins form the largest group of arginine methylated proteins.21 Arginine methylation can have either positive or negative effects on protein-protein or protein-RNA interactions. In a straightforward example, purified methylated HuD binds weakly to target p21 mRNA as compared with unmethylated HuD. In contrast, methylation of HuR stabilizes its binding to the SIRT1 mRNA as observed in co-IP assays from cells.25,26 Finally, arginine methylation reduces the interaction of hnRNP K with the tyrosine kinase c-Src, leading to inhibition of c-Src activation,27 based on co-IP studies from cells, whereas methylated arginines in Sm proteins are ligands for binding of the Tudor family of proteins.28 Arginine methylation could affect direct interactions of RGG motif proteins with RNAs or proteins by either the methyl group increasing the hydrophobicity of arginine residue to promote stacking interactions with mRNA,29,30 reducing the number of hydrogen bonds the arginine residue can form, or by creating a steric hindrance for a specific interaction.

In summary, the RGG motif proteins orchestrate various cellular processes, including multiple functional states of mRNA. RGG motifs are well suited for this role, since they bind both proteins and RNA, and such interactions can be modulated by posttranslational modifications (such as arginine methylation) of the RGG motifs.

The newfound role of RGG motif proteins in repressing translation is exemplified by the Scd6 repression mechanism. Two further implications of Scd6 translation repression mechanism are the possible effects of Scd6-repressed mRNAs on entry into translation and how Scd6 might positively and negatively influence mRNA decapping.

mRNPs Poised for Re-Entry to Translation

Scd6 binds eIF4G through its RGG motif and prevents recruitment of the 43S complex, leading to repression of the translation initiation step. However, Scd6 does not perturb the binding of eIF4E, eIF4A or Pab1 to eIF4G on the cap. Thus, it maintains the integrity of the cap-binding complex consisting of 4E-4G-4A-Pab1. In principle, this type of mRNP is poised to enter translation. Displacement of Scd6 from this repressed mRNP would allow the repressed mRNA to directly recruit the multi-factor complex, consisting of the 40S ribosome and several translation initiation factors. This type of re-entry to translation would require minimal mRNP remodeling and might allow an mRNA a competitive advantage in translation initiation, particularly under conditions where the cap-binding complex is limiting, which can be experimentally tested. Evidence suggesting that such complexes will be primed for entry into translation comes from the study of the RGG motif protein Ded1. In this case, Ded1 initially represses translation initiation and is a part of the repressed mRNP but is released from the mRNP when it hydrolyzes ATP, leading to translation initiation.18

mRNA stability

Based on the mechanism of Scd6 function, one anticipates it will both stimulate and inhibit mRNA decapping. A repressed mRNA with eIF4E/4G on its cap would be protected from decapping and subsequent 5′-3′ decay. This is analogous to the mechanism by which the eIF4E-binding protein CUP functions to protect the transcripts from decapping and decay.16 We speculate that other translational repressors targeting eIF4G such as Khd120 and RGG motif proteins (Sbp1 and Npl3) will also work to stabilize some mRNAs by promoting the formation of an mRNP wherein the cap structure is sequestered from the decapping enzyme in the absence of translation. Consistent with this view, khd1Δ strains show a reduction in MTL1 mRNA in a manner that is dependent on the decapping enzyme.42 Moreover, the ability of eIF4G-binding RGG motif proteins to bind specifically distinct subsets of mRNAs would lead to transcript-specific repression by these proteins. For example, Khd1 specifically promotes repression of ASH120 mRNA and, L13a is required for regulation of ceruloplasmin19 mRNA.

Several lines of evidence also suggest that Scd6 and other RGG motif proteins can promote decapping. First, scd6Δ strains show a synthetic defect in decapping with the edc3Δ44 (Edc3 is another related activator of decapping).43 Second, Scd6, Dcp5 (Arabidopsis ortholog of Scd6) and the S. pombe Scd6 physically interact with purified Dcp2 but do not stimulate its decapping activity,45,46 although the S. pombe Scd6 stimulates Dcp2 activity very weakly.47 Interestingly, the Lsm domain of Scd6 is responsible for the interaction with Dcp2,45 whereas RGG motif domain interacts with eIF4G.1

There are two non-mutually exclusive possibilities for how Scd6 might stimulate decapping. In one model, Scd6 would initially repress translation of an mRNA by binding to eIF4G followed by recruitment of Dcp2, which would then enhance loss of eIF4E, leading to mRNA decapping. Alternatively, whether Scd6 binds Dcp2 or eIF4G might be influenced by other components of a given mRNP, and therefore Scd6 would bind eIF4G to repress translation and inhibit decapping on some mRNAs, whereas it would bind Dcp2 to promote decapping on other mRNAs.

In principle, these two different possibilities could extend to other eIF4G binding proteins. For example, overexpression of Sbp1 in a pat1Δ strain that is defective in decapping at least partially restores decapping activity,48 suggesting that Sbp1 might also function as both a translation repressor and decapping inhibitor in some contexts and as an activator of decapping in others. An important area of future research will be to determine how Scd6 affects mRNA decapping and how such effects are modulated in an mRNA-specific manner.

Why do so Many RGG Motif Proteins Bind eIF4G?

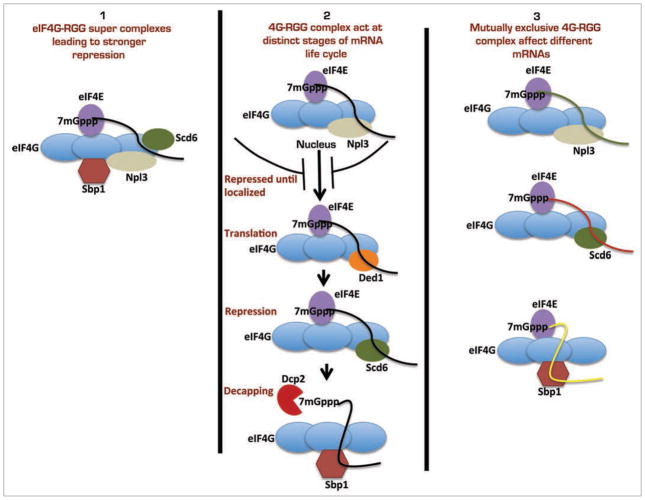

One interesting observation from our work is that a variety of different RGG motif proteins appear to interact with eIF4G. Moreover, initial mapping of the interaction domains suggest that these proteins can interact with different parts of the eIF4G molecule.1 This suggests three different models for how RGG motif proteins might be interacting with eIF4G and its implication on global cellular translation (Fig. 1). In one model, multiple RGG motif proteins can simultaneously interact with eIF4G. This would lead to super complexes containing eIF4G bound to multiple RGG motif-containing proteins that are perhaps more efficient in repressing translation as compared with eIF4G bound by a single RGG motif repressor. This could be a way to ensure repression of mRNAs that may escape repression mediated by a single RGG motif protein. In a second model, different RGG motif proteins might interact with eIF4G at different stages during the life of mRNA. For example, Npl3 shuttles between nucleus and cytoplasm, hence it could associate with eIF4G on target mRNAs in the nucleus. Finally, binding of different RGG motif proteins to eIF4G might be competitive, and these interactions would then be mutually exclusive. Each eIF4G-RGG motif complex could affect a specific subset of mRNAs, thus increasing the diversity of regulation.

Figure 1.

Possibilities explaining functional relevance of eIF4G interaction with RGG motif proteins.

How is the eIF4G-RGG Motif Protein Interaction Regulated?

An unresolved issue is whether the interaction of eIF4G with one or more RGG motif proteins is modulated by posttranslational modification of RGG motif proteins and/or eIF4G. One possibility is that methylation at the arginine residue in the RGG-box49 might directly or indirectly affect interaction with eIF4G. Alternatively, phosphorylation could also influence interaction of RGG motif proteins. For example, phosphorylation of Npl3 by SR-kinase Sky1 promotes dissociation of Npl3 from its target mRNA.50 Binding of other molecules to RGG motif proteins could also modulate eIF4G-RGG motif interactions. For example, DEAD-box RNA helicase Ded1 binds eIF4G to repress translation and subsequently activates translation upon ATP-hydrolysis. 18 Ded1 binds eIF4G through a domain that contains a single RGG motif. It is thus possible that ATP-hydrolysis promotes dissociation of Ded1 interaction with eIF4G. Similarly posttranslational modifications of eIF4G, which is a known target of phosphorylation51 and acetylation52 could also modulate its interaction with RGG motif proteins. These modifications, alone or in several combinations, could impact on the eIF4G-RGG motif protein interactions.

Can eIF4G be an Integrator of mRNA Functional States?

A final implication of this work and one from other labs is that eIF4G could be an integrator of functional states of mRNA. eIF4G can provide a scaffold to recruit proteins that negatively affect translation, such as RGG motif proteins,1 Khd120 and L13a.19 The scaffolding role of eIF4G in promoting translation initiation is well known. Similarly role of eIF4G in splicing by recruiting splicing factors has been demonstrated. Both yeast and mammalian eIF4G (present in nucleus) bind spliceosome components Prp11p and Snu71p.53 In the absence of eIF4G1 (Tif4631), a subset of mRNAs accumulates in their pre-spliced forms. Thus eIF4G can recruit proteins to affect different functional states of mRNA. Consistent with the idea that cap-binding proteins could be involved in integrating multiple functional states of mRNA, eIF4E functions not only to promote translation initiation, but also plays a role in translation repression and mRNA export.16,54 The ability of eIF4G to act as a scaffold to recruit many protein factors makes it better suited for the role of integrator of mRNA functional states.

One anticipates that eIF4G will also be involved in other functional states of mRNA life, such as mRNA decay, by recruiting decay proteins. A recent report suggests that levels of about 150 mRNAs are increased in yeast when eIF4G is depleted.55 The underlying mechanism is not clear, but it is possible that eIF4G could promote decapping/decay of some of these transcripts. This could happen directly as a result of eIF4G acting as a scaffold to recruit decay factors, which is supported by the interaction of eIF4G with Dcp256 in genome wide two-hybrid screens and by copurification of eIF4G with Xrn157 in genome-wide purification studies. Evidence supporting involvement of eIF4G in mRNA decay and perhaps other steps of translation would establish eIF4G as an integrator of mRNA functional states. Experiments aimed at gaining thorough knowledge of proteins that directly bind eIF4G under different physiological conditions would be a good starting point in this direction.

References

- 1.Rajyaguru P, She M, Parker R. Scd6 targets eIF4G to repress translation: RGG motif proteins as a class of eIF4G-binding proteins. Mol Cell. 2012;45:244–54. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.11.026. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. New modes of translational control in development, behavior and disease. Mol Cell. 2007;28:721–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Topisirovic I, Sonenberg N. mRNA Translation and Energy Metabolism in Cancer: The Role of the MAPK and mTORC1 Pathways. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1101/sqb.2011.76.010785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruggero D, Sonenberg N. The Akt of translational control. Oncogene. 2005;24:7426–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209098. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1209098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu-Yesucevitz L, Bassell GJ, Gitler AD, Hart AC, Klann E, Richter JD, et al. Local RNA translation at the synapse and in disease. J Neurosci. 2011;31:16086–93. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4105-11.2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4105-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhuvanagiri M, Schlitter AM, Hentze MW, Kulozik AE. NMD: RNA biology meets human genetic medicine. Biochem J. 2010;430:365–77. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100699. http://dx.doi.org/10.1042/BJ20100699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Decker CJ, Parker R. A turnover pathway for both stable and unstable mRNAs in yeast: evidence for a requirement for deadenylation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1632–43. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.8.1632. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.7.8.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muhlrad D, Decker CJ, Parker R. Deadenylation of the unstable mRNA encoded by the yeast MFA2 gene leads to decapping followed by 5′→3′ digestion of the transcript. Genes Dev. 1994;8:855–66. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.7.855. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.8.7.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tharun S, Parker R. Targeting an mRNA for decapping: displacement of translation factors and association of the Lsm1p-7p complex on deadenylated yeast mRNAs. Mol Cell. 2001;8:1075–83. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00395-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00395-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brengues M, Teixeira D, Parker R. Movement of eukaryotic mRNAs between polysomes and cytoplasmic processing bodies. Science. 2005;310:486–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1115791. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1115791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhattacharyya SN, Habermacher R, Martine U, Closs EI, Filipowicz W. Relief of microRNA-mediated translational repression in human cells subjected to stress. Cell. 2006;125:1111–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.031. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker R, Sheth U. P bodies and the control of mRNA translation and degradation. Mol Cell. 2007;25:635–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eulalio A, Behm-Ansmant I, Izaurralde E. P bodies: at the crossroads of post-transcriptional pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrm2080. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrm2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hilgers V, Teixeira D, Parker R. Translation-independent inhibition of mRNA deadenylation during stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA. 2006;12:1835–45. doi: 10.1261/rna.241006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1261/rna.241006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gowrishankar G, Winzen R, Dittrich-Breiholz O, Redich N, Kracht M, Holtmann H. Inhibition of mRNA deadenylation and degradation by different types of cell stress. Biol Chem. 2006;387:323–7. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.043. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/BC.2006.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Igreja C, Izaurralde E. CUP promotes deadenylation and inhibits decapping of mRNA targets. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1955–67. doi: 10.1101/gad.17136311. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.17136311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marnef A, Sommerville J, Ladomery MR. RAP55: insights into an evolutionarily conserved protein family. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:977–81. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.06.015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hilliker A, Gao Z, Jankowsky E, Parker R. The DEAD-box protein Ded1 modulates translation by the formation and resolution of an eIF4F-mRNA complex. Mol Cell. 2011;43:962–72. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapasi P, Chaudhuri S, Vyas K, Baus D, Komar AA, Fox PL, et al. L13a blocks 48S assembly: role of a general initiation factor in mRNA-specific translational control. Mol Cell. 2007;25:113–26. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.028. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mol-cel.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paquin N, Ménade M, Poirier G, Donato D, Drouet E, Chartrand P. Local activation of yeast ASH1 mRNA translation through phosphorylation of Khd1p by the casein kinase Yck1p. Mol Cell. 2007;26:795–809. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen C, Nott TJ, Jin J, Pawson T. Deciphering arginine methylation: Tudor tells the tale. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:629–42. doi: 10.1038/nrm3185. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrm3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pawlak MR, Scherer CA, Chen J, Roshon MJ, Ruley HE. Arginine N-methyltransferase 1 is required for early postimplantation mouse development, but cells deficient in the enzyme are viable. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4859–69. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.13.4859-4869.2000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.20.13.4859-69.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong CM, Tang HM, Kong KY, Wong GW, Qiu H, Jin DY, et al. Yeast arginine methyltransferase Hmt1p regulates transcription elongation and termination by methylating Npl3p. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:2217–28. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1133. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkp1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McBride AE, Cook JT, Stemmler EA, Rutledge KL, McGrath KA, Rubens JA. Arginine methylation of yeast mRNA-binding protein Npl3 directly affects its function, nuclear export and intranuclear protein interactions. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30888–98. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505831200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M505831200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calvanese V, Lara E, Suárez-Alvarez B, Abu Dawud R, Vázquez-Chantada M, Martínez-Chantar ML, et al. Sirtuin 1 regulation of developmental genes during differentiation of stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13736–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001399107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1001399107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hubers L, Valderrama-Carvajal H, Laframboise J, Timbers J, Sanchez G, Côté J. HuD interacts with survival motor neuron protein and can rescue spinal muscular atrophy-like neuronal defects. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:553–79. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq500. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddq500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ostareck-Lederer A, Ostareck DH, Rucknagel KP, Schierhorn A, Moritz B, Huttelmaier S, et al. Asymmetric arginine dimethylation of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K by protein-arginine methyltransferase 1 inhibits its interaction with c-Src. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11115–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513053200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M513053200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Côté J, Richard S. Tudor domains bind symmetrical dimethylated arginines. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28476–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414328200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M414328200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pahlich S, Zakaryan RP, Gehring H. Protein arginine methylation: Cellular functions and methods of analysis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1764:1890–903. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu MC. The Role of Protein Arginine Methylation in mRNP Dynamics. Mol Biol Int. 2011;2011:163827. doi: 10.4061/2011/163827. http://dx.doi.org/10.4061/2011/163827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brahms H, Meheus L, de Brabandere V, Fischer U, Lührmann R. Symmetrical dimethylation of arginine residues in spliceosomal Sm protein B/B′ and the Sm-like protein LSm4, and their interaction with the SMN protein. RNA. 2001;7:1531–42. doi: 10.1017/s135583820101442x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S135583820101442X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friesen WJ, Paushkin S, Wyce A, Massenet S, Pesiridis GS, Van Duyne G, et al. The methylosome, a 20S complex containing JBP1 and pICln, produces dimethylarginine-modified Sm proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:8289–300. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.24.8289-8300.2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.21.24.8289-300.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Selenko P, Sprangers R, Stier G, Bühler D, Fischer U, Sattler M. SMN tudor domain structure and its interaction with the Sm proteins. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:27–31. doi: 10.1038/83014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/83014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nichols RC, Wang XW, Tang J, Hamilton BJ, High FA, Herschman HR, et al. The RGG domain in hnRNP A2 affects subcellular localization. Exp Cell Res. 2000;256:522–32. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4827. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/excr.2000.4827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boisvert FM, Hendzel MJ, Masson JY, Richard S. Methylation of MRE11 regulates its nuclear compartmentalization. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:981–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.7.1830. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/cc.4.7.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonsalvez GB, Rajendra TK, Tian L, Matera AG. The Sm-protein methyltransferase, dart5, is essential for germ-cell specification and maintenance. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1077–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.037. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klattenhoff C, Theurkauf W. Biogenesis and germ-line functions of piRNAs. Development. 2008;135:3–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.006486. http://dx.doi.org/10.1242/dev.006486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mowen KA, Schurter BT, Fathman JW, David M, Glimcher LH. Arginine methylation of NIP45 modulates cytokine gene expression in effector T lymphocytes. Mol Cell. 2004;15:559–71. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.042. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koyuncu OO, Dobner T. Arginine methylation of human adenovirus type 5 L4 100-kilodalton protein is required for efficient virus production. J Virol. 2009;83:4778–90. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02493-08. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02493-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bikkavilli RK, Malbon CC. Wnt3a-stimulated LRP6 phosphorylation is dependent upon arginine methylation of G3BP2. J Cell Sci. 2012 doi: 10.1242/jcs.100933. http://dx.doi.org/10.1242/jcs.100933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Mauchi N, Ohtake Y, Irie K. Stability control of MTL1 mRNA by the RNA-binding protein Khd1p in yeast. Cell Struct Funct. 2010;35:95–105. doi: 10.1247/csf.10011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1247/csf.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kshirsagar M, Parker R. Identification of Edc3p as an enhancer of mRNA decapping in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2004;166:729–39. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.2.729. http://dx.doi.org/10.1534/genetics.166.2.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Decourty L, Saveanu C, Zemam K, Hantraye F, Frachon E, Rousselle JC, et al. Linking functionally related genes by sensitive and quantitative characterization of genetic interaction profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5821–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710533105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0710533105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nissan T, Rajyaguru P, She M, Song H, Parker R. Decapping activators in Saccharomyces cerevisiae act by multiple mechanisms. Mol Cell. 2010;39:773–83. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu J, Chua NH. Arabidopsis decapping 5 is required for mRNA decapping, P-body formation and translational repression during postembryonic development. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3270–9. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.070078. http://dx.doi.org/10.1105/tpc.109.070078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fromm SA, Truffault V, Kamenz J, Braun JE, Hoffmann NA, Izaurralde E, et al. The structural basis of Edc3- and Scd6-mediated activation of the Dcp1:Dcp2 mRNA decapping complex. EMBO J. 2012;31:279–90. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.408. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2011.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Segal SP, Dunckley T, Parker R. Sbp1p affects translational repression and decapping in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:5120–30. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01913-05. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01913-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frankel A, Clarke S. RNase treatment of yeast and mammalian cell extracts affects in vitro substrate methylation by type I protein arginine N-methyltransferases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;259:391–400. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0779. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.1999.0779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gilbert W, Siebel CW, Guthrie C. Phosphorylation by Sky1p promotes Npl3p shuttling and mRNA dissociation. RNA. 2001;7:302–13. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201002369. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1355838201002369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Raught B, Gingras AC, Gygi SP, Imataka H, Morino S, Gradi A, et al. Serum-stimulated, rapamycin-sensitive phosphorylation sites in the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4GI. EMBO J. 2000;19:434–44. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.3.434. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/emboj/19.3.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chuang C, Lin SH, Huang F, Pan J, Josic D, Yu-Lee LY. Acetylation of RNA processing proteins and cell cycle proteins in mitosis. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:4554–64. doi: 10.1021/pr100281h. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/pr100281h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blackwell E, Zhang X, Ceman S. Arginines of the RGG box regulate FMRP association with polyribosomes and mRNA. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:1314–23. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddq007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kafasla P, Barrass JD, Thompson E, Fromont-Racine M, Jacquier A, Beggs JD, et al. Interaction of yeast eIF4G with spliceosome components: implications in pre-mRNA processing events. RNA Biol. 2009;6:563–74. doi: 10.4161/rna.6.5.9861. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/rna.6.5.9861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Topisirovic I, Siddiqui N, Lapointe VL, Trost M, Thibault P, Bangeranye C, et al. Molecular dissection of the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) export-competent RNP. EMBO J. 2009;28:1087–98. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2009.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park EH, Zhang F, Warringer J, Sunnerhagen P, Hinnebusch AG. Depletion of eIF4G from yeast cells narrows the range of translational efficiencies genome-wide. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:68. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-12-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fromont-Racine M, Mayes AE, Brunet-Simon A, Rain JC, Colley A, Dix I, et al. Genome-wide protein interaction screens reveal functional networks involving Sm-like proteins. Yeast. 2000;17:95–110. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(20000630)17:2<95::AID-YEA16>3.0.CO;2-H. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1097-0061(20000630)17:2<95::AIDYEA16>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Collins SR, Kemmeren P, Zhao XC, Greenblatt JF, Spencer F, Holstege FC, et al. Toward a comprehensive atlas of the physical interactome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:439–50. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600381-MCP200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/mcp.M600381-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]