Abstract

Patients infected with highly pathogenic avian influenza A H5N1 viruses (H5N1 HPAIV) show diffuse alveolar damage. However, the temporal progression of tissue damage and repair after viral infection remains poorly defined. Therefore, we assessed the sequential histopathological characteristics of mouse lung after intranasal infection with H5N1 HPAIV or H1N1 2009 pandemic influenza virus (H1N1 pdm). We determined the amount and localization of virus in the lung through IHC staining and in situ hybridization. IHC used antibodies raised against the virus protein and antibodies specific for macrophages, type II pneumocytes, or proliferating cell nuclear antigen. In situ hybridization used RNA probes against both viral RNA and mRNA encoding the nucleoprotein and the hemagglutinin protein. H5N1 HPAIV infection and replication were observed in multiple lung cell types and might result in rapid progression of lung injury. Both type II pneumocytes and macrophages proliferated after H5N1 HPAIV infection. However, the abundant macrophages failed to block the viral attack, and proliferation of type II pneumocytes failed to restore the damaged alveoli. In contrast, mice infected with H1N1 pdm exhibited modest proliferation of type II pneumocytes and macrophages and slight alveolar damage. These results suggest that the virulence of H5N1 HPAIV results from the wide range of cell tropism of the virus, excessive virus replication, and rapid development of diffuse alveolar damage.

Seasonal, pandemic, and zoonotic influenza A virus infections show substantial morbidity and mortality in humans. Seasonal influenza A virus infections in humans are usually mild and cause pneumonia only in a few infected individuals. Pandemic influenza virus infections vary in their disease outcome. Zoonotic influenza virus infections in humans vary from self-limiting conjunctivitis to severe, often fatal, pneumonia. Highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus (H5N1 HPAIV), implicated in poultry outbreaks,1,2 can be transmitted zoonotically to humans, as has been observed in areas of Asia and Africa.3–5 Fatal outcomes have been reported at approximately 60% in the sporadic transmission of this avian influenza H5N1 virus to humans.5–7 There is no evidence that the avian influenza virus has become efficiently transmissible among humans, a change that could result in a new pandemic.8

The outcome after infection with influenza virus can range from slight to severe illness, depending on the kinds of cells that are affected during lung tissue infection.9–11 Events occurring early in infection determine the extent of damage, which can range from bronchitis to pneumonia. In the most severe cases, diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) may be induced during the early stages, and healing and/or scarring may ensue, depending on the persistence of disease. Occasionally, bacterial infection also may occur, with associated effects expressed mainly in the later stages of the disease. Pathological damage caused by influenza viruses in humans and in animal models depends on the virulence of the infective agent and on the host response. All influenza viruses infect the respiratory tract epithelium from the nasal passages to the bronchioles; however, highly virulent viruses (eg, H1N1 1918 and H5N1 HPAIV) tend to infect pneumocytes and resident macrophages in the alveoli. In susceptible individuals, inflammation of the alveolar walls results in DAD. In contrast, low-virulence viruses (seasonal H1N1) primarily cause inflammation, congestion, and epithelial necrosis of the trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles. Tissue tropism is an important factor, and depends largely on the ability of the virus to attach to the host cell.12–14 We investigated virus replication and histopathological progression of lung tissue in mice infected with H5N1 HPAIV, particularly focusing on the lower respiratory tract and alveoli, with direct comparison to the histopathological characteristics of mice infected with H1N1 pandemic (pdm) influenza virus 2009 virus.

Materials and Methods

Viruses

This study used the H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus A/whooper swan/Hokkaido/1/2008 strain (H5N1 HPAIV) and the H1N1 pandemic influenza virus A/Tokyo/2619/2009 strain (H1N1 pdm 2009). All experiments using H5N1 HPAIV were performed in biosafety level 3 facilities. H5N1 HPAIV was propagated in embryonated eggs. Virus-containing allantoic fluid was harvested and stored in aliquots at −80°C pending use. H1N1 pdm 2009 virus was subcultured in MDCK cells grown in modified Eagle’s medium (MEM; Nissui Pharmaceutical Co Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 10 μg/mL acetyl-trypsin.

Antibodies

The monoclonal antibody (mAb) 8C1 (IgG1 κ), raised against mouse-derived influenza A H5N1 hemagglutinin (H5N1-HA), was established in this study by using GANP mouse.15 This mAb was purified as the IgG fraction (0.86 mg/mL) using protein G column chromatography. Mouse mAb against the influenza A nucleoprotein (NP) was obtained from hybridoma HB-65, which was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA).16,17 Mouse mAb was purified as the IgG fraction (1.64 mg/mL) using protein G column chromatography.

Infection of BALB/c Mice with Influenza Virus

All experimental animal protocols were approved by the Animal Use and Care Committee of Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science (Tokyo, Japan). BALB/c mice (12- to 13-week-old females) were purchased from SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). For infection, animals were anesthetized by i.p. injection of 0.15 mL of ketamine/xylazine, and administered intranasally with 50 μL per mouse of infectious virus [2 × 106 plaque-forming units (PFUs) H1N1 pdm 2009 virus or 1 × 104 PFUs H5N1 HPAIV] diluted in vehicle (MEM medium containing 1% bovine serum albumin and MEM vitamin solution). An equivalent volume of vehicle was administered intranasally to each of the mice of the control group. At 1, 3, 6, or 7, and 9 days after infection, three to four mice per group were euthanized under deep anesthesia, and the lungs were collected. Segments of the lung tissues were frozen at −80°C or fixed in 10% buffered formalin.

Titration of Influenza Virus in the Lung Tissues

The left upper lung from each mouse was used for titration of influenza virus. The viral contents of the lung tissues were determined in three to four mice per time point in each group. Briefly, lung tissues were homogenized in nine volumes of Leibovitz 15 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The homogenate was centrifuged at 3000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C pending use. Serial 10-fold dilutions of the supernatant were added to MDCK cells seeded on 6-well plates. After 3 days of incubation, the cells were fixed with 10% buffered formalin. Viral titers were determined as plaque numbers resulting from added supernatant, and were expressed as PFUs per gram of tissue.

Histopathological Characteristics

The right lung lobe from each mouse was fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, divided into tissue sections (3 μm thick), stained with H&E, and subjected to routine histological examination. Histological changes were evaluated according to the modified methods of Trias et al,18 van Riel et al,9 or Vincent et al.19 For each lung tissue section, 10 randomly selected microscopic fields were scanned at a magnification of ×100, and each field was graded visually on a scale from 0 to 7. The grading system for histological changes is defined as follows: 0, normal lung; 1, mild destruction of epithelium in trachea and bronchus; 2, mild infiltration of inflammatory cells around the periphery of bronchioles; 3, moderate infiltration of inflammatory cells around the alveolar walls, resulting in alveolar thickening; 4, mild alveolar injury accompanied by vascular damage of ≤10%; 5, moderate alveolar and vascular injury (11% to approximately 30%); 6, severe alveolar injury with hyaline membrane–associated alveolar hemorrhage of 31% to approximately 50%; and 7, severe alveolar injury with hyaline membrane–associated alveolar hemorrhage of ≥51%. The mean value of the grades obtained for all fields then was used as the grade of visual lung injury.

IHC for Viral Antigens

The formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue specimens described in the previous paragraph were divided into tissue sections (6 μm thick) and processed for immunohistochemical (IHC) studies. Influenza A viral NP or H5N1 hemagglutinin (H5N1-HA) was detected/localized in lung tissue (after infection by the respective virus) using the Vector M.O.M. Immunodetection PK-2200 peroxidase kit (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA). After deparaffinization of tissue, slides were immersed in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0, and autoclaved at 120°C for 5 minutes. Sections were then treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide and blocked with blocking reagent. We used mouse anti-influenza NP mAb (HB65) at 1:1000 dilution (1.64 μg/mL) or anti–H5N1-HA mAb (8C1) at 1:2000 dilution (0.43 μg/mL) as the primary antibody, and biotinylated anti-mouse IgG polyclonal Ab at 1:250 dilution as the secondary antibody. After washing with PBS(-), slides were incubated in freshly complexed avidin-biotin hydroperoxidase reagent (Vector Laboratories, Inc.). Color development was performed with diaminobenzidine (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan)/H2O2 solution, and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Stained sections were observed using an A2 upright microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging Co, Ltd, Göttingen, Germany), and images were captured using a ZEISS Axio Imager (Carl Zeiss Microimaging Co, Ltd). Positive expression of NP or H5N1-HA was evaluated and scored using the following IHC scoring system: 0, no positive cells; 1, rare positive cells; 2, infrequent positive cells; 3, common positive cells; and 4, extensive positive cells.20

IHC for Proliferating Alveolar Macrophages and Pneumocytes

To study the responses of type II pneumocytes and macrophages in the alveoli to H5N1 HPAIV infection, a double immune-staining technique was performed using two antibodies. The first antibody [mouse anti–proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) mAb; Beckman Coulter, Inc., Marseille, France] had specificity against the PCNA. The second antibody recognized a cell type–specific marker indicative of macrophages [ionized calcium-binding adapter molecular 1 (Iba1): polyclonal rabbit anti-Iba1 antibody; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd, Osaka, Japan] or type II pneumocytes [surfactant-associated protein C (SP-C): polyclonal rabbit anti–SP-C antibody; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA]. Staining (30 minutes, room temperature) was performed using the combination of anti-PCNA and anti-Iba1 or of anti-PCNA and anti–SP-C (each at 1:200 dilution) as the primary antibody. A biotin-conjugated anti-mouse IgG or an alkaline phosphatase–labeled donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) was used as the secondary Ab. For the detection of PCNA, the Vector PK-2200 peroxidase kit and freshly complexed avidin-biotin reagent were used (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Immunoreactants were visualized using a diaminobenzidine and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/nitro blue tetrazolium substrate system (1-StepTMNBT/BCIP plus Suppressor; Pierce Biotechnology, Thermo Scientific). Proliferation of alveolar epithelial cells or macrophages was assessed semiquantitatively, as follows. Each lung section was quantified in 10 randomly selected microscopic fields (magnification ×400). The proliferation index was defined as the mean percentage of PCNA-positive cells in SP-C–positive cells or in Ibal-positive cells.21

Cytokine and Chemokine Profiles

Samples of mouse lung were homogenized in a solution of 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1.0% Triton X-100, and 20 mmol/L EDTA containing protease inhibitor.22 The resulting homogenates were assessed for cytokines and chemokines using Bio-Plex cytokine assay kits (Bio-Rad Laboratories), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Specifically, we used the Bio-Plex mouse cytokine 23-Plex Panel, which includes 23 cytokines [IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 (P40), IL-12 (P70), IL-13, IL-17, eotaxin, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interferon (IFN)-γ, keratinocyte-derived chemokine, monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α, MIP-1β, regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α], and the Bio-Plex mouse cytokine 9-Plex Panel, which includes nine cytokines (IL-15, IL-18, fibroblastic growth factor-basic, leukemia inhibitory factor, macrophage colony-stimulating factor, monokine induced by IFN-γ, MIP-2, platelet-derived growth factor-β, and vascular endothelial growth factor). Samples were analyzed on a Bio-Rad 96-well plate reader using the Bio-Plex Suspension Array System and Bio-Plex Manager software version 5.0 (Bio-Rad Laboratories). We also measured protein levels in the lung homogenates using the DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentrations of cytokines in the lung tissues were calculated as pg cytokine/mg total protein in the lung homogenates.

In Vitro Transcription of the RNA Probes

Full-length NP- and HA-encoding cDNAs (from H5N1 HPAIV or H1N1 pdm 2009 virus) were cloned in either orientation under control of a T7 promoter. The (+)- or (−)-strand synthetic RNAs for the genes were transcribed and labeled using the digoxigenin (DIG) RNA labeling kit (SP6/T7) (Roche Diagnostics, GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA products were purified over a G-50 column, precipitated with ethanol, and resuspended in 10 mmol/L Tris and 1 mmol/L EDTA, pH 7.4 (T10E1). The resulting suspensions were assayed for RNA concentration, and the length of each synthetic RNA was confirmed by 1.5% formaldehyde denaturation gel electrophoresis. The labeled transcripts were hydrolyzed with carbonic acid buffer (pH 10.2) to yield RNA fragments of approximately 150 bp in length. A hydrolyzed probe was precipitated with ethanol and resuspended in RNase-free water. The resulting suspensions were again assayed for RNA concentration, and the length of each synthetic RNA was confirmed by 2.0% formaldehyde denaturation gel electrophoresis.23

In Situ Hybridization Analysis

The lung tissue samples for NP and HA RNA detection were fixed in 10% buffered formalin (pH 7.4), embedded in paraffin, and cut into sections (6 μm thick). The slide-mounted sections were washed three times (8 minutes per wash) in xylene, three times (5 minutes per wash) in 99.5% ethanol, and three times (5 minutes per wash) in 75% ethanol, then rehydrated in distilled water for deparaffinization. The tissue slides were treated with 30 μg/mL proteinase K for 30 minutes at 37°C. After washing the tissue samples twice with diethyl pyrocarbonate–treated PBS at room temperature, the tissue samples were incubated in 95% formamide and 0.1× standard saline citrate (SSC; 1× SSC: 150 mmol/L NaCl and 15 mmol/L sodium citrate) for 15 minutes at 65°C. After chilling on ice, the slides were incubated in 100 μL of prehybridization solution for 60 minutes at room temperature. Prehybridization solution was composed of 50% formamide, 2× SSC, 1 μg/mL of salmon sperm DNA, 1 μg/mL of yeast tRNA, and 2 mmol/L vanadyl ribonucleoside complex. Then, the slides were incubated in 25 μL of hybridization solution (prehybridization solution containing 10% dextran sulfate and 200 ng/mL of the RNA probes) for 18 hours at 42°C. After hybridization, the slides were washed three times with solution 1 (50% formamide and 2× SSC at pH 7.4) for 20 minutes at 50°C. The tissue sections then were treated with 1 μg/mL RNase A for 10 minutes at 37°C in PBS and washed three times in wash solution 2 (0.1× SSC at pH 7.4) for 20 minutes at 50°C. Next, the tissue sections were incubated in blocking solution (Roche blocking reagent) for 30 minutes at room temperature. To detect DIG-labeled probe, an alkaline phosphatase–labeled sheep anti-DIG antibody (Roche) was used as the primary antibody. The slides then were incubated in 25 μL dye solution [338 μg/mL nitroblue tetrazolium chloride, 175 μg/mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate, 4-toluidine salt, and 1 mmol/L levamisole (Vector Laboratories Inc.) in 100 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 9.5), 100 mmol/L NaCl, and 50 mmol/L MgCl2] for 12 hours at room temperature in the dark. Stained sections were observed using an A2 upright microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging Co, Ltd), and images were captured using a ZEISS Axio Imager.

Results

Replication of Influenza Viruses

The titer of H5N1 HPAIV in lung tissues increased approximately 200-fold over the first 6 days after infection, before subsequently decreasing (Figure 1A). In contrast, the titer in lung tissue after H1N1 pdm 2009 virus infection progressively decreased until the last detection on 7 days after infection (Figure 1B). This distinction was observed despite the higher infecting titer used with H1N1 pdm 2009 virus (2 × 106 PFUs) compared with H5N1 HPAIV (1 × 104 PFUs). Consistent with the observed lung titers, all of the mice (n = 4) infected with H1N1 pdm 2009 virus survived for 9 days, whereas only 29% (n = 2 of 7) of H5N1 HPAIV-infected mice survived over the same interval.

Figure 1.

Pneumonia progression in mice after intranasal infection with H5N1 HPAIV or influenza A/H1N1 pdm 2009 virus. A and B: The virus titer of lung tissue was determined in three to four mice at each time point after intranasal infection with H5N1 HPAIV (1, 3, 6, and 9 days after infection; A) and with H1N1 pdm 2009 (1, 3, 7, and 9 days after infection; B). C and D: Lung histopathological characteristics were evaluated at different levels of the lower respiratory tract after infection with H5N1 HPAIV (C) or with H1N1 pdm 2009 virus (D). Representative figures at each time point (three to four mice per time point) are shown, with the three rows of images in both C and D corresponding to bronchial epithelium, alveoli, and vascular endothelium. Original magnification, ×630. Mice administered with vehicle were used as a control group. E and F: Pathological score of the lungs obtained from mice infected with influenza H5N1 HPAIV (E) and pandemic H1N1 virus (F). Scoring of the lung histological characteristics was done in three to four mice from each group at each time point. Data are expressed as means ± SD. ND, not detected.

Evaluation of Lung Histopathological Characteristics

Owing to the remarkable viral expansion, tissue damage extended rapidly to the lower respiratory tract within 3 days in mice infected with H5N1 HPAIV. Three days after infection, various degrees of bronchitis and epithelial necrosis were observed (Figure 1C). Interstitial inflammation, hyaline layer formation, varying degrees of alveolar edema, hemorrhage, and inflammation also were observed (Figure 1C). Furthermore, alveolar collapse and DAD were observed 9 days after infection. In contrast, histopathological observation of the lungs from mice infected with H1N1 pdm 2009 virus revealed that inflammation was restricted, detected primarily in bronchioles and occasional alveoli (Figure 1D). Consistent with these observations, histopathological scores were elevated more than twofold in the lungs of mice infected with H5N1 HPAIV compared with those of mice infected with H1N1 pdm 2009 virus (Figure 1, E and F).

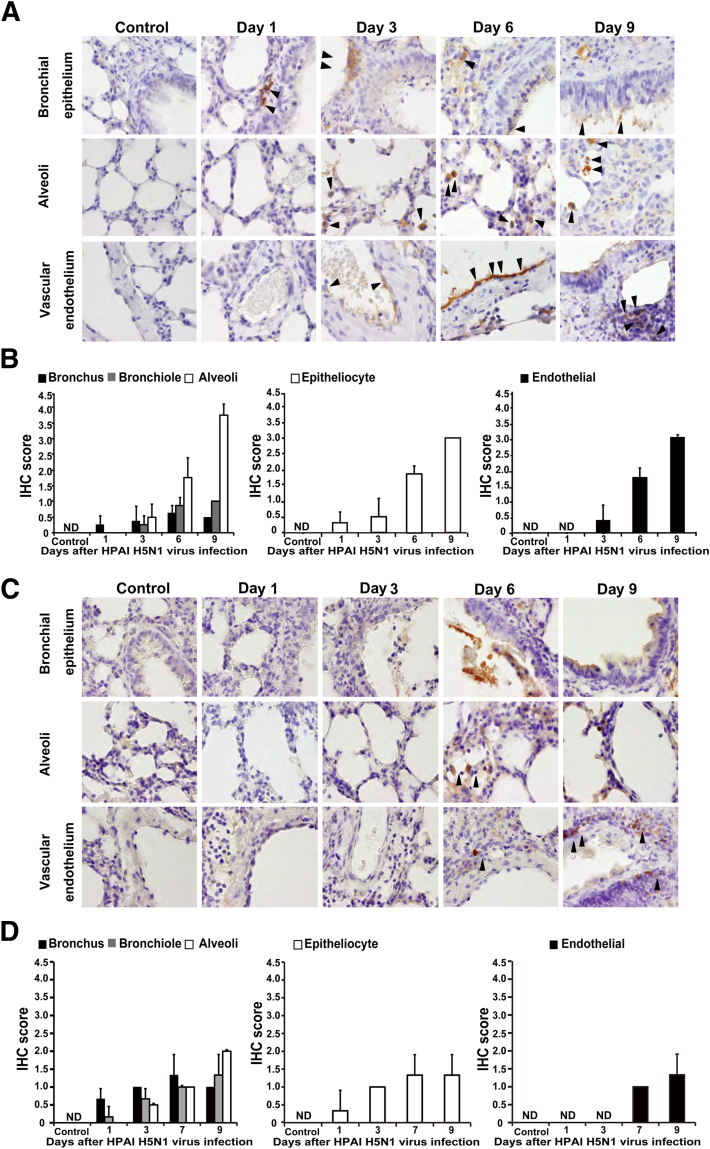

Localization of Viral Antigens in Lung Tissue

To further characterize the intensely damaged lung tissues of mice infected with H5N1 HPAIV, we investigated the production of viral proteins in various lung cell types. NP antigen was detected in bronchial epithelial cells, type II pneumocytes, macrophages, vascular endothelium, and perivascular lymphocytes (Figure 2A). High levels of NP antigen also were seen in necrotic materials associated with the respiratory tract (Figure 2A). Expression of NP antigen exhibited a time-dependent expansion to the alveoli and vascular endothelium; expression in the bronchus gradually faded from day 3 to day 9 after infection (Figure 2, A and B).

Figure 2.

IHC analysis for NP protein in the lung of mice infected with H5N1 HPAIV or H1N1 pdm 2009 virus. IHC staining for NP protein was performed in the lungs of mice infected with H5N1 HPAIV (A and B) or H1N1 pdm 2009 virus (C and D). Mice administered vehicle were used as a control group. A and C: The expression of the NP protein is indicated (brown). Arrowheads indicate NP-positive cells. Each column of images indicates postinfection days 1 to 9. Representative figures at each time point (four mice per time point) are shown, with the three rows of images in both A and C corresponding to bronchial epithelium, alveoli, and vascular endothelium. Original magnification, ×630. B and D: Temporal changes in the numbers of NP-positive cells in the lung tissue of infected mice. Quantification of cells staining positive for NP protein in bronchus, bronchiole, alveoli, epithelial cells of lower respiratory tract, and vascular endothelium. Numbers of NP-positive cells were evaluated using the IHC scoring system (see Materials and Methods). Data are expressed as means ± SD of three to four mice per time point. ND, not detected.

In mice infected with H1N1 pdm 2009 virus, NP antigen was detected predominantly in the epithelial cells of the bronchus and bronchiole (Figure 2, C and D). The levels of NP antigen in endothelial cells, vascular and perivascular lymphocytes (Figure 2, C and D), and alveoli (Figure 2, C and D) remained low compared with the levels of NP antigen seen in mice infected with H5N1 HPAIV (Figure 2, A and B). These results suggested that H1N1 pdm 2009 virus expansion in the lung tissue was limited, occurring mainly in epithelial cells of the bronchus and bronchiole; antigen detection showed limited induction in the alveoli (Figure 2, C and D), in contrast to the pattern seen in mice infected with H5N1 HPAIV (Figure 2, A and B).

We further studied the IHC staining for NP antigen or H5N1-HA antigen using a mouse monoclonal antibody that was generated (for this study) by using GANP Tg mouse; staining was performed with the respective antibodies on paired serial sections of lung tissue obtained 3 days after infection with H5N1 HPAIV. Staining for H5N1-HA antigen achieved a higher intensity than that seen for NP antigen (Figure 3A). Thus, H5N1-HA antigen may provide improved sensitivity for detection of H5N1 HPAIV-infected lung tissue (Figure 3, B and C).

Figure 3.

IHC staining for H5N1-HA protein in the lungs of mice infected with H5N1 HPAIV. A: Paired serial sections of the lungs from mice 3 days after infection were assessed to determine the consistent location of viral antigens in the sample. B: Temporal changes of IHC staining for H5N1-HA protein in the lungs of mice infected with H5N1 HPAIV. Each column indicates days 1 to 9 after infection. Representative figures at each time point (four mice per time point) are shown, with the three rows of images corresponding to bronchial epithelium, alveoli, and vascular endothelium. Arrowheads indicated H5N1 HA-positive cells. Original magnifications: ×100 (A); ×630 (B). C: Temporal changes in the numbers of H5N1-HA–positive cells. Quantification of cells staining positive for HA protein in bronchus, bronchiole, alveoli, epithelial cells of lower respiratory tract, and vascular endothelium. Numbers of HA-positive cells were evaluated using the IHC scoring system (see Materials and Methods). Data are expressed as means ± SD of four mice per time point. ND, not detected.

Detection of Viral RNA in Lung Tissue after Influenza Virus Infection

To evaluate viral replication in murine lung after influenza virus infection, we performed in situ hybridization with DIG-labeled RNA probes specific for either minus-strand RNA [viral RNA (vRNA)] or plus-strand RNA (mRNA) derived from influenza virus. We generated strand-specific (vRNA and mRNA) DIG-labeled RNA probes corresponding to the genes encoding HA and NP proteins, and confirmed the specificity of these probes in influenza virus–infected MDCK cells (Supplemental Figure S1). DIG-labeled RNA probes specific for the vRNA of either the HA- or NP-encoding genes stained the nuclei of MDCK cells infected with either H5N1 virus or H1N1 pdm 2009 virus. On the other hand, DIG-labeled RNA probes specific for the mRNA of either the HA- or NP-encoding genes stained the cytoplasm of MDCK cells infected with either H5N1 virus or H1N1 pdm 2009 virus. As shown in Figure 4A, both the vRNA and mRNA of H5N1 HPAIV were detected in bronchial epithelial cells, type II pneumocytes, and vascular endothelial cells; both H5N1 viral transcripts were detected, at lower levels, in macrophages. In contrast, the vRNA and mRNA of H1N1 pdm 2009 virus were detected primarily in epithelial cells of bronchus and bronchiole, but rarely in pneumocytes, at 6 days after infection (Figure 4B). The H1N1 viral transcripts were not detected in the lung at 9 days after infection.

Figure 4.

Detection of influenza virus RNA in the lungs of mice infected with H5N1 HPAIV or H1N1 pdm 2009 virus. A and B: In situ hybridization analyses were performed in H5N1 HPAIV-infected murine lung samples (A) or H1N1 pdm 2009 virus-infected murine lung samples (B) using DIG-labeled RNA probes specific for vRNA and mRNA. Representative figures at each time point (four mice per time point) are shown, with the three rows of images in both A and B corresponding to bronchial epithelium, alveoli, and vascular endothelium. Original magnification, ×630. dpi, days post-infection.

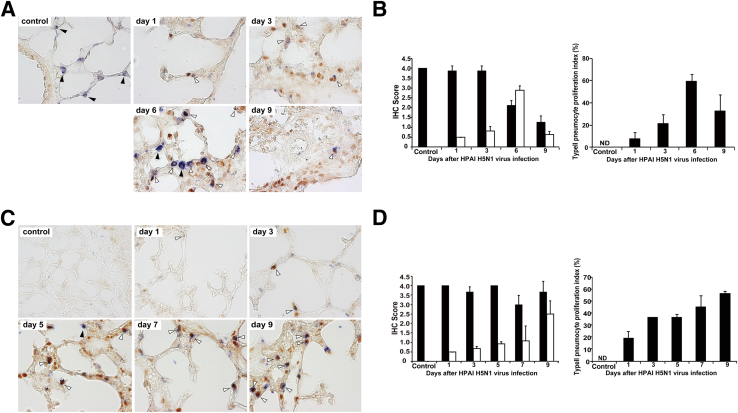

Proliferation of Macrophages after Infection with Influenza Viruses

A dual-staining technique was used to discriminate proliferating macrophages from residential macrophages in the alveoli of lung specimens from virus-infected mice. Cells that stained positive for both PCNA and a macrophage-specific marker (Iba1) (PCNA+/Iba1+) may be newly proliferating macrophages or may be derived from infiltrating monocytes. In mice infected with H5N1 HPAIV, images of dual-stained lung tissue revealed extensive proliferation of the macrophages, with progressively increasing numbers of macrophages seen starting from day 3 after infection (Figure 5A). This proliferation was confirmed by IHC scoring, achieving a mean IHC score of 4.0 (extensive positive cells) by day 9 after infection (Figure 5B). At that time, the proportion of PCNA+/Iba1+ cells against total Iba1+ cells reached approximately 90% (Figure 5B). In mice infected with H1N1 pdm 2009 virus, proliferation of the macrophages in the alveoli also was observed after infection (Figure 5C). However, mean IHC scores remained ≤1.0 (rare positive cells) through day 9 after infection (Figure 5D). The proportion of PCNA+/Iba1+ cells was only approximately 30% (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

The proliferation of alveolar macrophages infected with H5N1 HPAIV or H1N1 pdm 2009 virus. Double immunostaining was performed for PCNA and alveolar macrophage-specific marker (Iba1) in mice infected with H5N1 HPAIV (A and B) or influenza A/H1N1 pdm 2009 virus (C and D). White arrowheads, proliferating alveolar macrophages (PCNA+/Iba1+); black arrowheads, resident alveolar macrophages (PCNA−/Iba1+). B and D: The cells with positive staining were counted in 10 randomly selected microscopic fields of individual animals, and mean IHC scores were calculated. Original magnifications: ×630 (A and B). Black bars indicate number of resident macrophages (PCNA−/Iba1+); white bars, number of newly proliferated macrophages (PCNA+/Iba1+). Proliferation index, defined as the number of proliferating macrophages (PCNA+/Iba1+) expressed as a percentage of total macrophage (Iba1+) numbers. These observations were performed in three to four mice per time point. Data are shown as means ± SD. ND, not detected.

Proliferation of Type II Pneumocytes after Infection with Influenza Viruses

In parallel with the macrophage study previously performed, we used a dual-staining technique to discriminate proliferating type II pneumocytes (cells that stained positive for both PCNA and a pneumocyte-specific marker (SP-C; PCNA+/SP-C+) (Figure 6A) from indigenous type II pneumocytes (PCNA−/SP-C+) (Figure 6A). In mice infected with H5N1 HPAIV, proliferation of type II pneumocytes peaked at 6 days after infection and subsequently decreased (Figure 6B). Mean IHC scores were approximately 3.0 (common positive cells) and <1.0 at 6 and 9 days after infection, respectively. The proportion of PCNA+/SP-C+ cells reached approximately 60% at 6 days after infection (Figure 6B). In mice infected with H1N1 pdm 2009 virus, proliferation of type II pneumocytes also was observed (Figure 6C), although alveolar injuries were rarely seen in H&E-stained lung specimens (compare to the injuries shown in Figure 1D). Proliferation of type II pneumocytes progressively increased through 9 days after infection with H1N1 pdm 2009 virus, in contrast to the time course seen after infection with H5N1 HPAIV. IHC score and proportion of PCNA+/SP-C+ cells reached approximately 2.5 and >50%, respectively (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

The proliferation of type II pneumocytes after infection with H5N1 HPAIV or H1N1 pdm 2009 virus. The proliferation of type II pneumocytes after infection with H5N1 HPAIV (A and B) or H1N1 pdm 2009 (C and D) was estimated. Double immunostaining was performed for PCNA and SP-C, a marker for type II pneumocytes. White arrowheads indicate proliferating type II pneumocytes (PCNA+/SP-C+); black arrowheads, resident type II pneumocytes (PCNA−/SP-C+). B and D: The cells with positive staining were counted in 10 randomly selected microscopic fields of individual animals, and mean IHC scores were calculated. Original magnifications: ×630 (A and B). Black bars indicate number of resident type II pneumocytes (SP-C+); white bars, number of newly proliferated type II pneumocytes (PCNA+/SP-C+). Proliferation index is defined as the number of proliferating type II pneumocytes (PCNA+/SP-C+) expressed as a percentage of total type II pneumocyte (SP-C+) numbers. These observations were performed in three to four mice per time point. Data are shown as means ± SD. ND, not detected.

Expression of Cytokines and Chemokines in the Lung Tissues after Infection with Influenza Virus

To analyze the immune responses of BALB/c mice after infection with H5N1 HAPIV or H1N1 pdm 2009 virus, we measured multiple cytokines and chemokines in lung homogenates (Figure 7). As shown in Figure 7A, expression levels of several proinflammatory cytokines were considerably higher in the lung of H5N1 HPAIV-infected mice than H1N1 2009 pdm virus-infected mice. Specifically, H5N1 HPAIV-infected mice exhibited the increase of IL-6 and IFN-γ 3 to 9 and 6 to 9 days after H5N1 HPAIV infection, respectively. IL-1β and TNF-α were considerably induced from 1 day after H5N1 HPAIV infection. In addition, macrophage-stimulating factors, including MCP-1, MIP-1α, and G-CSF, increased 6 to 9 days after H5N1 HPAIV infection (Figure 7B). These results were temporally consistent with massive infiltration of macrophages and progression of tissue damage.

Figure 7.

Time course of cytokine-chemokine levels in lungs after influenza virus infection. Lung samples were homogenized in cell lysis buffer and used for measurement of multiple cytokines and chemokines using the Bio-Plex suspension array system. A: Proinflammatory cytokines: IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-1β, and TNF-α. B: Macrophage-related cytokines: MCP-1, MIP-1α, and G-CSF in the lung of H1N1 pdm 2009-infected and H5N1 HPAIV-infected mice. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 3 to 4 per time point).

Discussion

In this study, we showed that infection of mice with H5N1 HPAIV caused serious lung damage leading to DAD, with most animals dying within 9 days. In mice infected with H1N1 pdm 2009 virus, however, the extent of lung damage was mainly within the epithelial cells of the bronchus and bronchiole, with occasional alveolar injury. All of the H1N1 pdm 2009 virus-infected animals survived through 9 days after infection. After infection with H5N1 HPAIV, the viral titers in lung tissue increased through day 6 and decreased on day 9. (However, the 9-day values were derived only from the two of seven animals that survived to the ninth day after infection.) In mice infected with H1N1 pdm 2009 virus, the viral titers in lung tissue gradually decreased over time. Notably, many kinds of cells (eg, vascular endothelial cells, pneumocytes, some macrophages, and epithelial cells) were infected with H5N1 HPAIV. Thus, H5N1 HPAIV appears to exhibit a wide range of tissue tropism within cells of the lungs, replicating in many kinds of cells in the lungs and resulting in an exaggerated production of the virus.

H5N1 avian influenza24 viruses are known to induce DAD in humans. In the lungs of fatal cases, H1N1 pdm 2009 virus induced DAD as a predominant pathological process of the lower respiratory tract, reflecting alveolar injury by both direct virus replication in pneumocytes and associated degeneration of the alveolar structures (probably by concurrent host immune processes).25 Several reports have suggested that the presence in the lower respiratory tract of high-affinity receptors for the virus may be a key trigger in infection by swine-origin influenza virus.26 In the human lower respiratory tract, H5N1 attaches predominantly to type II pneumocytes and alveolar macrophages, as well as to nonciliated cuboidal epithelial cells in terminal bronchioles; attachment becomes progressively rarer toward the trachea.11 In the present study (in mouse), H1N1 pdm 2009 virus caused limited lung injuries, with little damage observed in the alveoli even 9 days after infection. In contrast, H5N1 HPAIV caused severe lung damage, which eventually extended from the bronchus to the alveoli. Although proliferation of type II pneumocytes was stimulated, the alveolar damage worsened and extended rapidly, finally developing into DAD. Extensive destruction resulted in severe alveolar collapse, accompanied by intra-alveolar hemorrhage by 9 days after infection. These virulent processes have been ascribed to H5N1 and to other types of influenza virus, including Spanish influenza virus H1N1 1918,27 which showed highly pathogenic characters, and H3N2.11,28,29 Although influenza virus NP protein was detected at low levels in the alveoli of mice infected with H1N1 pdm 2009 virus in the present study, alveolar damage was not remarkable in H&E-stained lung specimens. Proliferation of macrophages that may be newly proliferating macrophages or may be derived from infiltrating monocytes, as well as type II pneumocytes, was observed in these animals. H1N1 pdm 2009 virus–infected mice showed viral clearance, suitable proliferation of these cells, and repair of alveolar damage.

The envelope of influenza virus contains two large surface-exposed glycoproteins: HA and neuraminidase. The former is responsible for attachment and penetration of virus into host cells, whereas the latter is responsible for budding of progeny virions from host cells. These molecules are important targets of the host immune response. The envelope encloses the NP, which includes both RNA-binding and polymerase domains. Viral antigen (HA) was detected using an mAb specific for H5N1-HA,15 which was recently developed in our laboratory. We detected viral antigen in the epithelial cells of the lower respiratory tract, necrotic material, alveolar epithelium, macrophages, vascular endothelium, and perivascular lymphocytes. Staining for H5N1-HA or NP in paired serial sections of lung tissue revealed the presence of NP and H5N1-HA in overlapping regions of the lung, suggesting co-expression of these antigens. Because H5N1-HA expression constitutes the dominant proportion of protein production in influenza-infected cells, we speculate that histochemical staining for H5N1-HA will provide greater sensitivity than for NP.

H5N1 HPAIV likely infects type I pneumocytes, which cover 95% of the total alveolar surface; the resulting cytopathic destruction is expected to lead to alveolar damage,30,31 which, in turn, would induce the proliferation of type II pneumocytes.32 In the present study, we observed that type II pneumocytes infected with H5N1 HPAIV exhibited extensive proliferation, with numbers peaking at 6 days after infection before decreasing at 9 days. The proliferation of type II pneumocytes is important for repairing alveolar damage, because type II pneumocytes differentiate into type I cells. We detected H5N1-HA antigen in type II pneumocytes, indicating that H5N1 HPAIV infected these cells. Because type II pneumocytes are metabolically active and are the most numerous cell type lining the alveoli after elimination of the type I pneumocytes, targeting of this cell type by virus is expected to lead to abundant virus production. Damage to type II pneumocytes may impair their functions, including re-epithelization of damaged alveoli, ion transport, and surfactant production; this may inhibit tissue repair. We speculate that acute proliferation of type II pneumocytes, as observed in the present study, prevents precise repair of the destroyed alveolar structures, with subsequent depletion of type II pneumocytes by viral cytopathic effects.

In the present study, many PCNA+ macrophages persisted for 9 days after infection, in contrast to the temporary increase observed for type II pneumocytes. A massive infiltration of macrophages has been observed in the lungs of H5N1-infected humans and mice.33–36 Targeting of macrophages by influenza virus may be important because of the role of macrophages in facilitating the host innate immune response to viral infection.11 Other researchers also have suggested that influenza infection of macrophages stimulates production and release of proinflammatory cytokines and α/β interferon,37 which may assist in limiting further viral replication and spread within the respiratory tract. Nonetheless, the lungs of the present study’s H5N1 HPAIV-infected mice were severely damaged, with exaggerated replication of H5N1 HPAIV. By using IHC staining, we showed the presence of viral proteins in alveolar epithelial cells and macrophages in alveoli. In contrast, an in situ hybridization assay showed that viral RNA transcripts were detected largely in alveolar epithelial cells, but not in macrophages in alveoli. Although the discrepancy of the detection levels between viral protein and viral RNA in macrophages raises the possibility of the phagocytic processes of viral antigens in the macrophages, further study is required for clearing whether phagocytic ingestions of influenza virus antigens occur.

Double IHC staining for PCNA (proliferation of cells) and SP-C (type II pneumocytes) or Iba1 (macrophages) was used to assess the proliferation of macrophages or of type II pneumocytes, respectively, in the alveoli after murine infection with H5N1 HPAIV. We observed that macrophage proliferation increased progressively through the 9 days after infection. In contrast, the proliferation of type II pneumocytes peaked at 6 days after infection, before subsequently decreasing. This difference in the time course of reaction to viral infection between these two cell types may reflect distinct responses to infection by H5N1 HPAIV. The direct viral injury to type II pneumocytes may impair these cells’ functions, including re-epithelialization after alveolar damage and surfactant production, thereby stalling tissue repair.11 Excessive accumulation of macrophages in the lungs could contribute to tissue damage by causing vascular injury and destruction of the parenchymal cells.38,39 Our cytokine-chemokine expression data supported these findings. In the present study, the response by macrophages appeared to be a major contributor to intense lung collapse.

In conclusion, intranasal infection of mice with H5N1 HPAIV resulted in intense viral replication in the lungs involving multiple cell types, with rapid progression of lung injuries leading to serious DAD. Proliferation of type II pneumocytes stalled the repair of alveolar damage. Hyperproliferation of macrophages that may be newly proliferating macrophages or may be derived from infiltrating monocytes appeared to impair defense against the viral attack, resulting in self-destruction. In mice infected with H1N1 pdm 2009 virus, adequate proliferation of the macrophages permitted successful defense against viral attack, and moderate proliferation of type II pneumocytes effectively repaired alveolar injuries. Thus, the lower respiratory tract was effectively excluded from the extent of lung injuries. We hypothesize that the virulence of H5N1 HPAIV results from the wide range of cell tropism of the virus, excessive virus replication in the lungs, and rapid development of injuries reaching to the alveoli.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Satoshi Naganawa and Sumiko Gomi and Yoshimi Tobita for technical support and all members of our laboratory for their advice and assistance.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan; the Program for Promotion of Fundamental Studies in Pandemic Influenza of the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science of Japan; and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan.

Current address of N.N., RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences, Kanagawa, Japan.

Supplemental Data

Confirmation of the specificity of strand-targeted DIG-labeled RNA in MDCK cells infected with influenza virus. A and B: By using DIG-labeled RNA probes specific for vRNA and mRNA at two different concentrations (200 or 500 ng/mL), in situ hybridization analyses were performed in MDCK cells infected with either H1N1 pdm 2009 virus (A) or H5N1 HPAIV (B). Uninfected MDCK cells were used as control samples. Original magnification, ×630. MOI, multiplicity of infection.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.10.004.

References

- 1.Okamatsu M., Tanaka T., Yamamoto N., Sakoda Y., Sasaki T., Tsuda Y., Isoda N., Kokumai N., Takada A., Umemura T., Kida H. Antigenic, genetic, and pathogenic characterization of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses isolated from dead whooper swans (Cygnus cygnus) found in northern Japan in 2008. Virus Genes. 2010;41:351–357. doi: 10.1007/s11262-010-0530-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakoda Y., Ito H., Uchida Y., Okamatsu M., Yamamoto N., Soda K., Nomura N., Kuribayashi S., Shichinohe S., Sunden Y., Umemura T., Usui T., Ozaki H., Yamaguchi T., Murase T., Ito T., Saito T., Takada A., Kida H. Reintroduction of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus by migratory water birds, causing poultry outbreaks in the 2010-2011 winter season in Japan. J Gen Virol. 2012;93(Pt 3):541–550. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.037572-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Claas E.C., Osterhaus A.D., van Beek R., De Jong J.C., Rimmelzwaan G.F., Senne D.A., Krauss S., Shortridge K.F., Webster R.G. Human influenza A H5N1 virus related to a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. Lancet. 1998;351:472–477. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.To K.F., Chan P.K., Chan K.F., Lee W.K., Lam W.Y., Wong K.F., Tang N.L., Tsang D.N., Sung R.Y., Buckley T.A., Tam J.S., Cheng A.F. Pathology of fatal human infection associated with avian influenza A H5N1 virus. J Med Virol. 2001;63:242–246. doi: 10.1002/1096-9071(200103)63:3<242::aid-jmv1007>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korteweg C., Gu J. Pathology, molecular biology, and pathogenesis of avian influenza A (H5N1) infection in humans. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1155–1170. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuiken T., Taubenberger J.K. Pathology of human influenza revisited. Vaccine. 2008;26(Suppl 4):D59–D66. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Jong M.D. H5N1 transmission and disease: observations from the frontlines. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:S54–S56. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181684d2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Sastre A., Whitley R.J. Lessons learned from reconstructing the 1918 influenza pandemic. J Infect Dis. 2006;194(Suppl 2):S127–S132. doi: 10.1086/507546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Riel D., Munster V.J., de Wit E., Rimmelzwaan G.F., Fouchier R.A., Osterhaus A.D., Kuiken T. Human and avian influenza viruses target different cells in the lower respiratory tract of humans and other mammals. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1215–1223. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chutinimitkul S., Herfst S., Steel J., Lowen A.C., Ye J., van Riel D., Schrauwen E.J., Bestebroer T.M., Koel B., Burke D.F., Sutherland-Cash K.H., Whittleston C.S., Russell C.A., Wales D.J., Smith D.J., Jonges M., Meijer A., Koopmans M., Rimmelzwaan G.F., Kuiken T., Osterhaus A.D., García-Sastre A., Perez D.R., Fouchier R.A. Virulence-associated substitution D222G in the hemagglutinin of 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus affects receptor binding. J Virol. 2010;84:11802–11813. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01136-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Riel D., Munster V.J., de Wit E., Rimmelzwaan G.F., Fouchier R.A., Osterhaus A.D., Kuiken T. H5N1 virus attachment to lower respiratory tract. Science. 2006;312:399. doi: 10.1126/science.1125548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reperant L.A., Kuiken T., Grenfell B.T., Osterhaus A.D., Dobson A.P. Linking influenza virus tissue tropism to population-level reproductive fitness. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang H. Tissue and host tropism of influenza viruses: importance of quantitative analysis. Sci China C Life Sci. 2009;52:1101–1110. doi: 10.1007/s11427-009-0161-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solecki D., Gromeier M., Harber J., Bernhardt G., Wimmer E. Poliovirus and its cellular receptor: a molecular genetic dissection of a virus/receptor affinity interaction. J Mol Recognit. 1998;11:2–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1352(199812)11:1/6<2::AID-JMR380>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakaguchi N., Kimura T., Matsushita S., Fujimura S., Shibata J., Araki M., Sakamoto T., Minoda C., Kuwahara K. Generation of high-affinity antibody against T cell-dependent antigen in the Ganp gene-transgenic mouse. J Immunol. 2005;174:4485–4494. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yewdell J.W., Frank E., Gerhard W. Expression of influenza A virus internal antigens on the surface of infected P815 cells. J Immunol. 1981;126:1814–1819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan K.H., Zhang A.J., To K.K., Chan C.C., Poon V.K., Guo K., Ng F., Zhang Q.W., Leung V.H., Cheung A.N., Lau C.C., Woo P.C., Tse H., Wu W., Chen H., Zheng B.J., Yuen K.Y. Wild type and mutant 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) viruses cause more severe disease and higher mortality in pregnant BALB/c mice. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13757. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trias E.L., Hassantoufighi A., Prince G.A., Eichelberger M.C. Comparison of airway measurements during influenza-induced tachypnea in infant and adult cotton rats. BMC Pulm Med. 2009;9:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-9-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vincent A.L., Thacker B.J., Halbur P.G., Rothschild M.F., Thacker E.L. An investigation of susceptibility to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus between two genetically diverse commercial lines of pigs. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:49–57. doi: 10.2527/2006.84149x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belser J.A., Gustin K.M., Maines T.R., Blau D.M., Zaki S.R., Katz J.M., Tumpey T.M. Pathogenesis and transmission of triple-reassortant swine H1N1 influenza viruses isolated before the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. J Virol. 2011;85:1563–1572. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02231-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki H., Aoshiba K., Yokohori N., Nagai A. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibition augments a murine model of pulmonary fibrosis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5054–5059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imai Y., Kuba K., Neely G.G., Yaghubian-Malhami R., Perkmann T., van Loo G., Ermolaeva M., Veldhuizen R., Leung Y.H., Wang H., Liu H., Sun Y., Pasparakis M., Kopf M., Mech C., Bavari S., Peiris J.S., Slutsky A.S., Akira S., Hultqvist M., Holmdahl R., Nicholls J., Jiang C., Binder C.J., Penninger J.M. Identification of oxidative stress and toll-like receptor 4 signaling as a key pathway of acute lung injury. Cell. 2008;133:235–249. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyanari Y., Atsuzawa K., Usuda N., Watashi K., Hishiki T., Zayas M., Bartenschlager R., Wakita T., Hijikata M., Shimotohno K. The lipid droplet is an important organelle for hepatitis C virus production. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1089–1097. doi: 10.1038/ncb1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maines T.R., Lu X.H., Erb S.M., Edwards L., Guarner J., Greer P.W., Nguyen D.C., Szretter K.J., Chen L.M., Thawatsupha P., Chittaganpitch M., Waicharoen S., Nguyen D.T., Nguyen T., Nguyen H.H., Kim J.H., Hoang L.T., Kang C., Phuong L.S., Lim W., Zaki S., Donis R.O., Cox N.J., Katz J.M., Tumpey T.M. Avian influenza (H5N1) viruses isolated from humans in Asia in 2004 exhibit increased virulence in mammals. J Virol. 2005;79:11788–11800. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.11788-11800.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basu A., Shelke V., Chadha M., Kadam D., Sangle S., Gangodkar S., Mishra A. Direct imaging of pH1N1 2009 influenza virus replication in alveolar pneumocytes in fatal cases by transmission electron microscopy. J Electron Microsc (Tokyo) 2011;60:89–93. doi: 10.1093/jmicro/dfq081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeh E., Luo R.F., Dyner L., Hong D.K., Banaei N., Baron E.J., Pinsky B.A. Preferential lower respiratory tract infection in swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:391–394. doi: 10.1086/649875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tumpey T.M., Garcia-Sastre A., Taubenberger J.K., Palese P., Swayne D.E., Pantin-Jackwood M.J., Schultz-Cherry S., Solorzano A., Van Rooijen N., Katz J.M., Basler C.F. Pathogenicity of influenza viruses with genes from the 1918 pandemic virus: functional roles of alveolar macrophages and neutrophils in limiting virus replication and mortality in mice. J Virol. 2005;79:14933–14944. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14933-14944.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seo S.H., Webby R., Webster R.G. No apoptotic deaths and different levels of inductions of inflammatory cytokines in alveolar macrophages infected with influenza viruses. Virology. 2004;329:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shinya K., Ebina M., Yamada S., Ono M., Kasai N., Kawaoka Y. Avian flu: influenza virus receptors in the human airway. Nature. 2006;440:435–436. doi: 10.1038/440435a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ng W.F., To K.F., Lam W.W., Ng T.K., Lee K.C. The comparative pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome and avian influenza A subtype H5N1–a review. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:381–390. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams M.C. Alveolar type I cells: molecular phenotype and development. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:669–695. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J., Edeen K., Manzer R., Chang Y., Wang S., Chen X., Funk C.J., Cosgrove G.P., Fang X., Mason R.J. Differentiated human alveolar epithelial cells and reversibility of their phenotype in vitro. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:661–668. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0410OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peiris J.S., Yu W.C., Leung C.W., Cheung C.Y., Ng W.F., Nicholls J.M., Ng T.K., Chan K.H., Lai S.T., Lim W.L., Yuen K.Y., Guan Y. Re-emergence of fatal human influenza A subtype H5N1 disease. Lancet. 2004;363:617–619. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15595-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maines T.R., Szretter K.J., Perrone L., Belser J.A., Bright R.A., Zeng H., Tumpey T.M., Katz J.M. Pathogenesis of emerging avian influenza viruses in mammals and the host innate immune response. Immunol Rev. 2008;225:68–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee S.M., Gardy J.L., Cheung C.Y., Cheung T.K., Hui K.P., Ip N.Y., Guan Y., Hancock R.E., Peiris J.S. Systems-level comparison of host-responses elicited by avian H5N1 and seasonal H1N1 influenza viruses in primary human macrophages. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee S.M., Cheung C.Y., Nicholls J.M., Hui K.P., Leung C.Y., Uiprasertkul M., Tipoe G.L., Lau Y.L., Poon L.L., Ip N.Y., Guan Y., Peiris J.S. Hyperinduction of cyclooxygenase-2-mediated proinflammatory cascade: a mechanism for the pathogenesis of avian influenza H5N1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:525–535. doi: 10.1086/590499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peschke T., Bender A., Nain M., Gemsa D. Role of macrophage cytokines in influenza A virus infections. Immunobiology. 1993;189:340–355. doi: 10.1016/s0171-2985(11)80365-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azoulay E., Darmon M., Delclaux C., Fieux F., Bornstain C., Moreau D., Attalah H., Le Gall J.R., Schlemmer B. Deterioration of previous acute lung injury during neutropenia recovery. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:781–786. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200204000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mulligan M.S., Watson S.R., Fennie C., Ward P.A. Protective effects of selectin chimeras in neutrophil-mediated lung injury. J Immunol. 1993;151:6410–6417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Confirmation of the specificity of strand-targeted DIG-labeled RNA in MDCK cells infected with influenza virus. A and B: By using DIG-labeled RNA probes specific for vRNA and mRNA at two different concentrations (200 or 500 ng/mL), in situ hybridization analyses were performed in MDCK cells infected with either H1N1 pdm 2009 virus (A) or H5N1 HPAIV (B). Uninfected MDCK cells were used as control samples. Original magnification, ×630. MOI, multiplicity of infection.