Abstract

Hepatic cystogenesis in polycystic liver diseases is associated with abnormalities of cholangiocyte cilia. Given the crucial association between cilia and centrosomes, we tested the hypothesis that centrosomal defects occur in cystic cholangiocytes of rodents (Pkd2WS25/− mice and PCK rats) and of patients with polycystic liver diseases, contributing to disturbed ciliogenesis and cyst formation. We examined centrosomal cytoarchitecture in control and cystic cholangiocytes, the effects of centrosomal abnormalities on ciliogenesis, and the role of the cell-cycle regulator Cdc25A in centrosomal defects by depleting cholangiocytes of Cdc25A in vitro and in vivo and evaluating centrosome morphology, cell-cycle progression, proliferation, ciliogenesis, and cystogenesis. The cystic cholangiocytes had atypical centrosome positioning, supernumerary centrosomes, multipolar spindles, and extra cilia. Structurally aberrant cilia were present in cystic cholangiocytes during ciliogenesis. Depletion of Cdc25A resulted in i) a decreased number of centrosomes and multiciliated cholangiocytes, ii) an increased fraction of ciliated cholangiocytes with longer cilia, iii) a decreased proportion of cholangiocytes in G1/G0 and S phases of the cell cycle, iv) decreased cell proliferation, and v) reduced cyst growth in vitro and in vivo. Our data support the hypothesis that centrosomal abnormalities in cholangiocytes are associated with aberrant ciliogenesis and that accelerated cystogenesis is likely due to overexpression of Cdc25A, providing additional evidence that pharmacological targeting of Cdc25A has therapeutic potential in polycystic liver diseases.

Polycystic liver diseases (PLDs) are inherited genetic disorders that include but are not limited to i) autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), the most common of these disorders; ii) autosomal recessive PKD (ARPKD), less common but generally more severe; and iii) autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease (ADPLD), a rare condition in which cyst formation is limited to the liver (unlike the other two conditions, in which cysts occur in both liver and kidneys).1–4 Defects in ciliary morphology and impaired ciliary-mediated intracellular signaling trigger atypical cell cycle and benign cell hyperproliferation, which are the major contributors to cyst formation and expansion. Indeed, we and others have shown that abnormalities in ciliary length (both elongation and shortening) and disturbed expression of ciliary-associated proteins are sufficient to generate the pathological cystic phenotype.5–11

Primary cilia have an intimate relationship with another cell organelle, the centrosome. Centrosomes play an important role in microtubule nucleation and organization, in cell-cycle progression, migration, ubiquitin-proteasome degradation, cell polarity and, importantly, in cilia formation.12,13 Centrosomes are composed of two centrioles linked by interconnecting fibers and surrounded by pericentriolar material. The older centriole (the mother centriole) is structurally distinguished from the daughter centriole by the presence of fibrous appendages. In the G1/G0 phase of the cell cycle, after centriole duplication, the mother centriole is recruited to the apical cell membrane to become the basal body, providing a template for nucleation of the ciliary axoneme.13–17

Both ciliary and centrosomal defects have been detected in nearly all human cancers. Many molecules have been implicated in centrosomal abnormalities, but most experimental evidence defines the tumor suppressor p53 (levels of which are abnormal in most tumors) as a major regulator of centrosome number, size, and appearance in cancer.13,14,18–23 Dysfunctional links between centrosomes and primary cilia have also been observed in polycystic kidney. Indeed, in several animal models of PKD and in patients with ADPKD, renal epithelial and endothelial cells have supernumerary centrosomes, defects in mitotic spindle formation, abnormal cell division, and malformed primary cilia.24–29

Our research group previously showed that primary cilia in cholangiocytes lining liver cysts of animal models of PLD (PCK rat and Pkd2WS25/− and Pkhd1del2/del2 mice) are morphologically abnormal.7,30,31 However, the structural and functional relationships between the centrosome and primary cilia in cystic cholangiocytes have not been addressed previously. Thus, to test the hypothesis that centrosomal defects contribute to ciliogenesis and cyst formation, we analyzed i) the centrosome cytoarchitecture (ie, their number, size, and cellular position), ii) the ability of supernumerary centrosomes to nucleate extra cilia, iii) the effects of centrosomal abnormalities on temporal ciliary growth (ie, ciliogenesis), and iv) the potential mechanisms responsible for centrosomal aberrations in PLD. Our results show that i) cystic cholangiocytes of animal models and human patients with PLD have improper centrosome positioning, overduplicated centrosomes, multipolar spindles, and extra cilia; ii) these defects are associated with impaired ciliogenesis in cystic cholangiocytes; iii) Cdc25A, a cell-cycle phosphatase overexpressed in PLD,8 is involved in regulation of the observed centrosomal abnormalities; and iv) genetic and pharmacological suppression of Cdc25A reduces the abnormal number of centrosomes per cell, reduces the proportion of cholangiocytes with multiple centrosomes and extra cilia, and alters the cell cycle, leading to decreased cholangiocyte proliferation and attenuated cyst growth. Taken together, our data confirm the importance of centrosomal abnormalities in hepatic cystogenesis and provide further support for Cdc25A as a potential therapeutic target in PLD.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Cell Cultures

Animals were maintained on a standard diet and water ad libitum. After anesthesia (50 mg/kg pentobarbital) and sacrifice, liver and kidney were paraffin-embedded for histology studies. Cholangiocytes were isolated from control and PCK rats as described previously.32 PCK cholangiocytes were stably transfected with Cdc25A shRNA (PCK-Cdc25A-sh) or empty vector (PCK-Cdc25A-EV) using forward and reverse primers 5′-TAGCAGCAGTCTACAAGAGAAT-3′ and 5′-GGAATCTCATTCGATGCATAC-3′) (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). PCK cholangiocytes stably transfected with miR-15a precursor (PCK-miR-15a-pre) or miR empty vector (PCK-miR-EV) were previously established by our research group.33 The protocol was approved by the Mayo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Electron Microscopy

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), samples were incubated in 1% osmium tetroxide for 30 minutes, dehydrated, dried in a critical-point drying device, mounted onto specimen stubs, and sputter-coated with gold–palladium alloy. SEM micrographs were used with ImageJ software version 1.46 (NIH, Bethesda, MD) to analyze ciliary position and ciliary length. SEM was performed with a Hitachi S-4700 electron microscope (Hitachi High Technologies America, Pleasanton, CA). For transmission electron microscopy (TEM), samples were fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 hour, rinsed in distilled water, dehydrated, embedded in Spurr’s resin, and sectioned at 80 nm. TEM was performed with a JEOL 1200 electron microscope (JEOL USA, Peabody, MA). TEM micrographs were used with ImageJ software to measure distances between basal bodies and cell lateral junctions, distances between centrioles, and length of the basal bodies.

Immunofluorescence Confocal Microscopy

Confocal microscopy was performed with a Zeiss LSM-510 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) using liver tissue of control and PCK rats; of control, Pkd2WS25/−, Pkhd1del2/del2, Cdc25A+/−, and Pkhd1del2/del2:Cdc25A+/− mice; and of healthy human subjects and patients with ADPKD and ARPKD. Normal and diseased human liver tissues were obtained from the Mayo Clinical Core facility and National Disease Research Interchange. Liver sections were stained with primary antibodies against γ-tubulin (1:100; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), acetylated α-tubulin (1:100; Sigma-Aldrich); pericentrin (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA); p53 (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); p21 (1:50; Abcam), Cdk2 (1:100; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), cyclin E (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and Cdc25A (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The respective secondary antibodies (1:100) were applied. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

Western Blotting

We used 4% to 15% SDS-PAGE to separate proteins, which then were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and probed with antibodies against p53, p21, Cdk2, cyclin E, and Cdc25A overnight at 4°C. Actin staining was used for normalization of protein loading. Membranes were washed and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with corresponding horseradish peroxidase–conjugated (Life Technologies) or Odyssey IRdye 680 or 800 (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE) secondary antibodies. Bands were visualized with an ECL Plus Western blotting detection kit (BD Biosciences) or an Odyssey Li-Cor scanner.

Flow Cytometry

PCK-Cdc25A-sh, PCK-Cdc25A-EV, PCK-miR-15a-pre, and PCK-miR-EV (n = 5 for each cell line) cholangiocytes were fixed in ethanol and suspended in 50 μg/mL propidium iodide containing 0.1 mg/mL RNase. Cell-cycle analysis was performed at the Mayo Advanced Genomics Technology Center.

Cell Proliferation Assay

PCK-Cdc25A-sh, PCK-Cdc25A-EV, PCK-miR-15a-pre, and PCK-miR-EV (n = 8 for each cell line) cholangiocytes were grown at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 100% humidity for 72 hours before the assay. The proliferation rate was determined using a CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution cell proliferation assay (Promega, Madison, WI) and a bromodeoxyuridine cell proliferation assay (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA).

Three-Dimensional Cultures and Cyst Measurement

PCK-Cdc25A-sh and PCK-Cdc25A-EV cholangiocytes were grown in three-dimensional matrices, as described previously.33 Cyst expansion was evaluated by light microscopy at days 1 (ie, 24 hours after seeding), 2, and 3. The circumferential area of each cyst (n = 50 for each condition) was measured using ImageJ software, as described previously.8

Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism software version 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used for statistical analysis. Statistical significance between two groups was tested by Student’s t-test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM, and differences of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Cystic Cholangiocytes Are Characterized by the Presence of Supernumerary Centrosomes

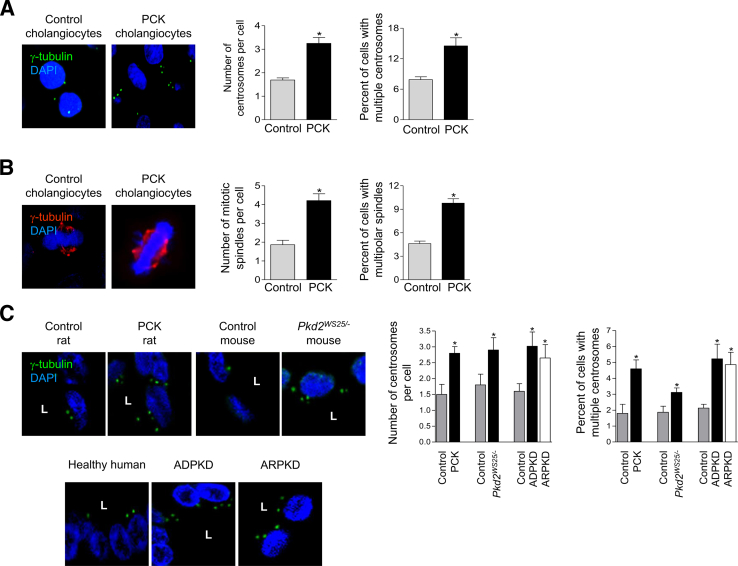

In cultured cystic cholangiocytes, we observed three to five centrosomes per cell and an increase to 15% in the quantity of cells with multiple centrosomes, compared with control (Figure 1A). The fraction of cholangiocytes with tripolar and multipolar spindle formations was also approximately two times greater (Figure 1B). Consistent with the in vitro observations, an approximate twofold increase in the percentage of cholangiocytes with multiple centrosomes was found in liver cysts of the PCK rat and Pkd2WS25/− mouse, compared with controls, as well as in patients with PLD (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Cystic cholangiocytes possess multiple centrosomes and multipolar spindles. A and B: Greater numbers of PCK cholangiocytes with multiple centrosomes (A) and numerous mitotic spindles (B) were observed in vitro. C: The number of centrosomes per cell and the percentage of cholangiocytes with extra centrosomes are increased in liver cysts of rodents and patients with polycystic liver diseases. Centrosomes (green) and mitotic spindles (red) were stained with γ-tubulin; nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 100 cholangiocytes per condition. ∗P < 0.05 versus control. Original magnification, ×100. L, lumen.

Supernumerary Centrosomes in Cystic Cholangiocytes Nucleate Extra Cilia

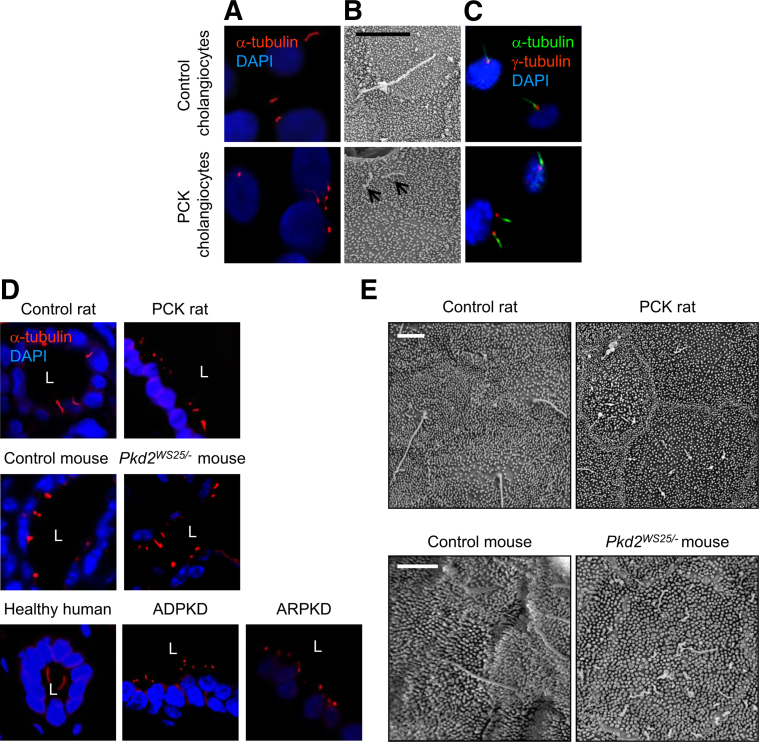

We investigated whether the additional centrosomes might produce extra cilia. Unlike controls, up to 8% of cystic cholangiocytes in vitro (Figure 2, A–C) and up to 6% of cystic cholangiocytes in vivo (Figures 2D and 3) were multiciliated, containing two or more cilia per cell.

Figure 2.

Cystic cholangiocytes are multiciliated. A and B: Numbers of cilia per cell assessed by confocal microscopy (A) and SEM (B) were increased in PCK cholangiocytes. Arrows in B indicate cilia. C: Confocal micrographs confirmed that primary cilium (green) arises from the basal bodies (red). D: Cholangiocytes with extra cilia are present in liver cysts of rodents and patients with polycystic liver diseases. E: Occurrence of multiciliated cholangiocytes was confirmed by SEM. Note that cilia in cystic cholangiocytes are shorter and malformed. Cilia were stained with α-tubulin [red (A and D) or green (B)] and basal bodies with γ-tubulin (red); nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Cilia are indicated by arrows (B). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 75 cholangiocytes per condition. Original magnification, ×100. Scale bars: 5 μm (B); 1 μm (E). L, lumen.

Figure 3.

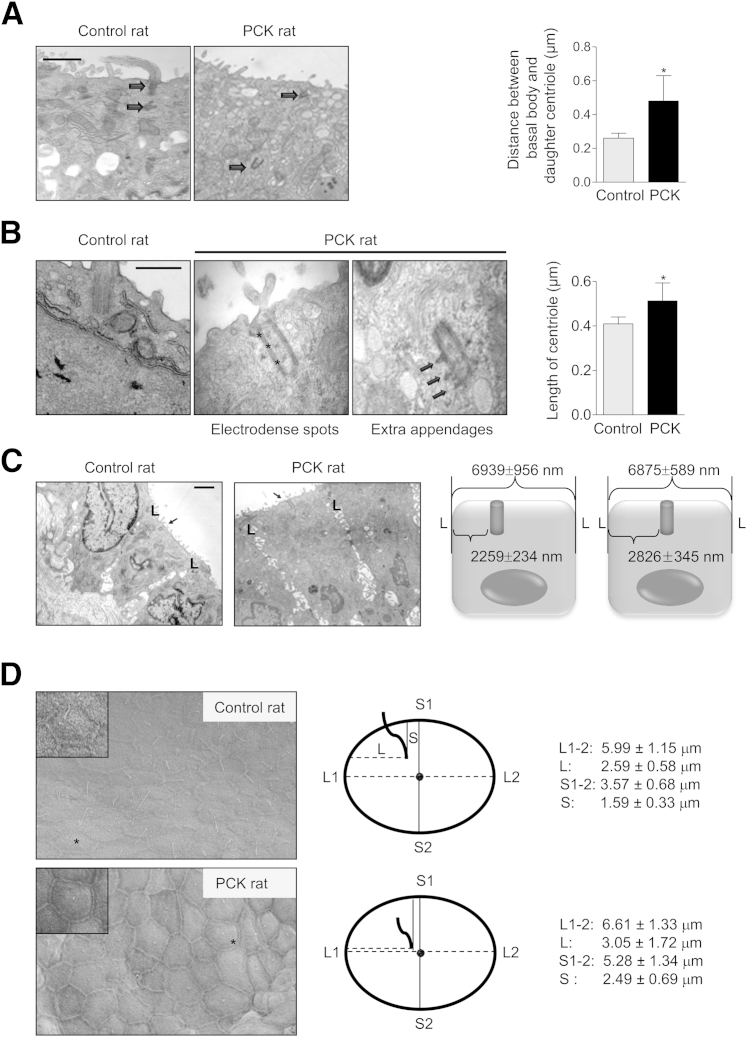

Centrosomal abnormalities in cystic cholangiocytes. A: Representative micrographs and graph showing the distance from the basal body (arrows) to the daughter centriole. B: In PCK rats, centrioles are longer, with electrodense spots (asterisks) and extra appendages (arrows). C: Basal bodies (arrows) in cystic cholangiocytes are positioned closer to the cell center. The diagram summarizes the basal body position relative to the cell lateral junction (L). D: SEM images and schematic diagrams illustrate the position of primary cilium. Cell center (black circle) was identified as the intersect of longest (L1–2, dashed line) and shortest (S1–2, solid line) cell axis. Position of cilia was measured along both axes. In cystic cholangiocytes, cilia are found closer to the cell center, compared with controls (P = 0.03). Cholangiocytes marked with an asterisk are shown in greater detail in the corresponding inset. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 50 cholangiocytes for each condition. ∗P < 0.05. Original magnification, ×2000 (D). Scale bars: 500 nm (A and B); 1 μm (C).

Centrosomes of Cystic Cholangiocytes Exhibit an Aberrant Phenotype

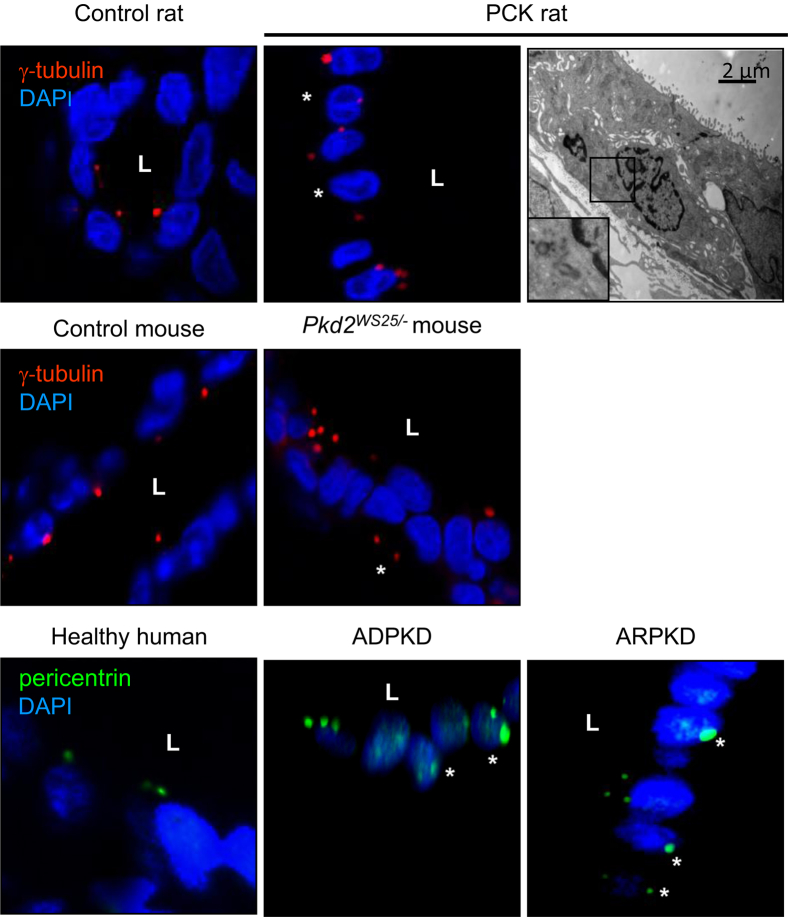

We further analyzed centrosomal defects (cellular position, length, and presence of extra appendages). In control cholangiocytes, the daughter centriole was positioned close to a mother centriole (basal body), but in cystic cholangiocytes this distance was increased (Figure 3A). Basal bodies were approximately 30% longer in cystic cholangiocytes and contained electrodense material and extra appendages (Figure 3B). In control cholangiocytes, the basal body was positioned close to one of the lateral junctions, whereas in cystic cholangiocytes it was located closer to the cell center (Figure 3C). Consistent with the more central location of the basal body, the primary cilium in PCK cholangiocytes was also situated nearer the cell center (Figure 3D). Finally, basolaterally located centrioles were observed in cholangiocytes lining hepatic cysts in rodent models and in patients with PLD, whereas in the respective controls the centrioles were adjacent to the apical membrane (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Centrosomal abnormalities in cystic cholangiocytes. Basolaterally located centrosomes (asterisks) are revealed in cystic cholangiocytes by confocal microscopy. Presence of basolaterally located centrosomes was confirmed in PCK rats by TEM. The boxed region is shown in greater detail in the inset. Centrioles are stained with γ-tubulin (green) or pericentrin (red). Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue). Images are representative of 50 cholangiocytes for each condition. Original magnification, ×100. Scale bar = 2 μm. L, lumen.

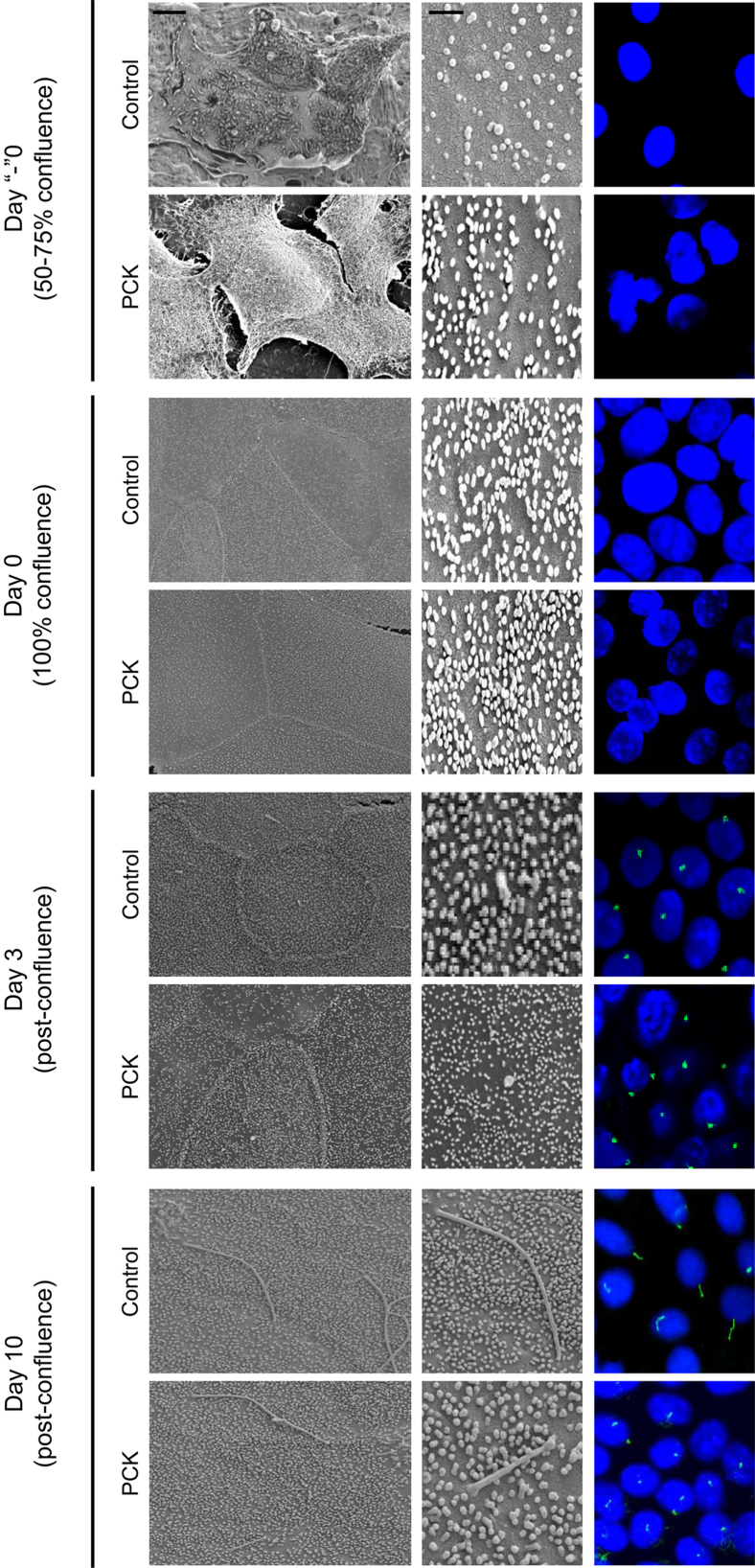

Ciliogenesis Is Impaired in Cystic Cholangiocytes

Ciliogenesis was examined in cholangiocytes derived from control and PCK rats (Figure 5). Cilia were not present in subconfluent (day “−”0) and immediately postconfluent (day 0) cholangiocytes. Cilia first appeared at day 3 after confluence and continued to grow, reaching a maximum size of approximately 10 to 12 μm by day 10 to 12. At all time points, cilia of PCK cholangiocytes were shorter by approximately 30% (P < 0.05). In addition, approximately 9% of PCK cholangiocytes were multiciliated, with two or three cilia per cell.

Figure 5.

Ciliogenesis is impaired in PCK cholangiocytes. Cilia were detected by SEM (left and middle columns) and confocal microscopy (right column) over time. Cilia were stained with α-tubulin (green); nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Images are representative of cholangiocytes for each time point and experimental condition. Original magnification, ×100 (right column).× Scale bars: 5 μm (left column); 1 μm (middle column).

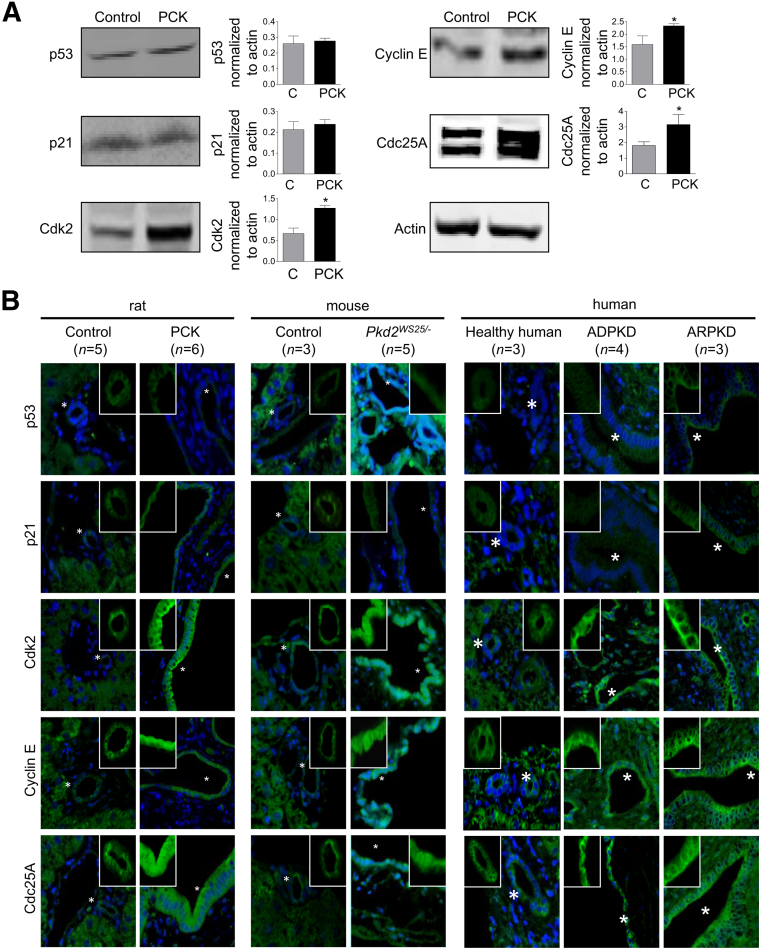

Expression of Proteins Involved in Centrosomal Abnormalities in Cystic Cholangiocytes Is Up-Regulated

The overduplication of centrosomes and their abnormal morphological appearance in cancer is controlled by the p53–p21–Cdk2–cyclin E axis. We therefore examined the expression of these proteins in benign hyperproliferative cystic cholangiocytes. No changes in p53 and p21 levels were observed, whereas their downstream effectors, Cdk2 and cyclin E, were up-regulated (Figure 6). Consistent with our previous data,33 expression of the phosphatase Cdc25A, which activates the Cdk2–cyclin E complex during the cell-cycle transition, was also increased (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Expression of proteins involved in centrosomal abnormalities. A: Western blots (n = 3) show that levels of p53 and p21 are not affected in cystic cholangiocytes, but expression of Cdk2 and cyclin E is increased. Cdc25A phosphatase, the upstream activator of the Cdk2–cyclin E complex, is also up-regulated. B: Overexpression of Cdk2, cyclin E, and Cdc25A was confirmed by confocal microscopy in cholangiocytes of rodents and patients with polycystic liver diseases. Proteins of interest stain green; nuclei stain blue. Features marked by an asterisk are shown without nuclear staining in the corresponding inset. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. ∗P < 0.05. Original magnification, ×63. C, control.

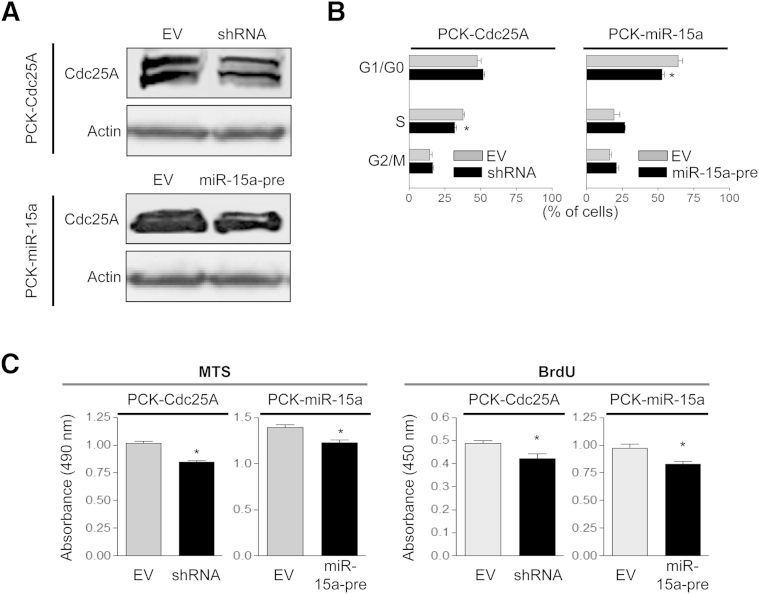

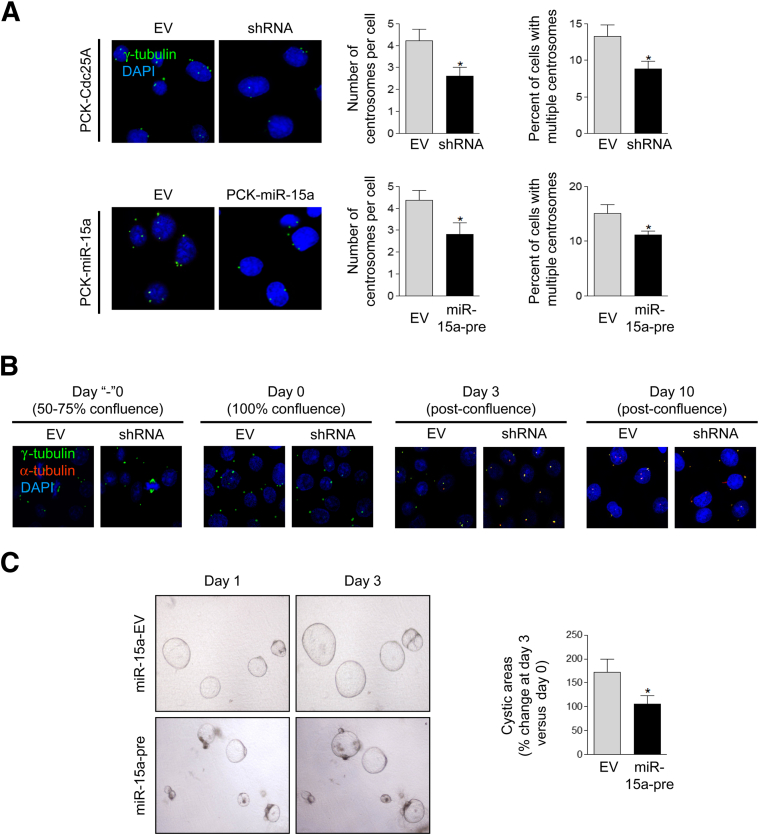

Cdc25A Plays an Important Role in Centrosomal Abnormalities

To address the role of Cdc25A in maintenance of centrosome architecture, we modified PCK cholangiocytes by depleting Cdc25A with specific shRNA (PCK-Cdc25A-sh). We also used PCK cholangiocytes transfected with an miR-15a precursor (PCK-miR-15a-pre) previously established in our laboratory.33 Cdc25A up-regulation in cystic cholangiocytes is a result of miR-15a inhibition, because treatment of PCK cholangiocytes with miR-15a precursor increases miR-15a, subsequently decreasing Cdc25A expression.33

Western blotting demonstrated that both approaches reduced protein levels of Cdc25A (Figure 7A), leading to a decreased proportion of cholangiocytes in S phase (PCK-Cdc25A-sh) and in G1/G0 phase (PCK-miR-15a-pre) (Figure 7B) of the cell cycle, reduced cell proliferation (Figure 7C), and decrease in centrosome number per cell and the percentage of cells with multiple centrosomes (Figure 8A). In addition, the number of mitotic spindles per cell and the fraction of PCK cholangiocytes with multiple spindles was reduced by 25% (P < 0.05), compared with respective controls. Ciliogenesis was also affected in response to Cdc25A depletion. The number of ciliated PCK-Cdc25A-sh cholangiocytes was increased to 63.17 ± 6.98%, compared with 44.72 ± 7.42% in PCK-Cdc25A-EV (P < 0.05) (Figure 8B), and cilia were longer (4.82 ± 0.43 μm) than in control (3.36 ± 0.48 μm) (P < 0.05). Similar effects were observed in PCK-miR-15a-pre cholangiocytes (data not shown). Finally, the growth rate of cysts formed in three-dimensional cultures by miR-15a-pre cholangiocytes (Figure 8C) or PCK-Cdc25A-sh cholangiocytes (data not shown) was decreased, compared with control.

Figure 7.

A: Depletion of Cdc25A by shRNA or by miR-15a precursor reduces Cdc25A levels in cystic cholangiocytes, as assessed by Western blotting. B and C: These perturbations affect cell cycle (B) and inhibit cell proliferation (C). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3. ∗P < 0.05. BrdU, bromodeoxyuridine; EV, empty vector.

Figure 8.

A: Depletion of Cdc25A by shRNA or by miR-15a precursor decrease number of centrosome per cell and fraction of cholangiocytes with multiple centrosomes. B: Ciliogenesis was examined by confocal microscopy in PCK-Cdc25A-sh cholangiocytes. C: Cyst growth was evaluated by light microscopy in PCK-miR-15a-pre cholangiocytes. Centrosomes were stained with γ-tubulin (green) and cilia with α-tubulin (red); nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 50 cholangiocytes (A and B) and n = 25 cysts (C) for each condition. ∗P < 0.05. Original magnification: ×100 (A and B); ×4 (C). EV, empty vector.

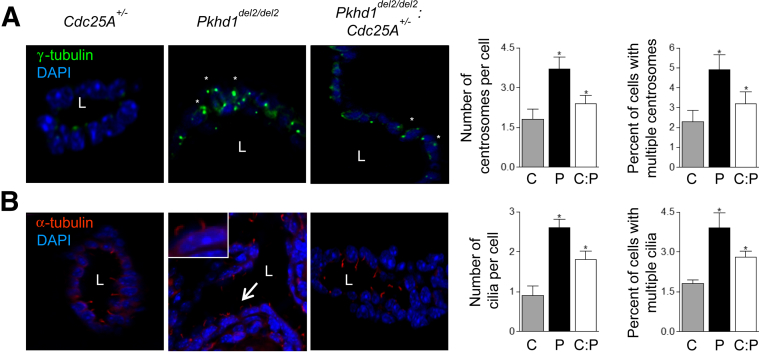

To confirm the role of Cdc25A in centrosomal abnormalities in vivo, we used Cdc25A+/−:Pkhd1del2/del2 cross-bred mice, as recently established in our laboratory; these mice have reduced expression of Cdc25A and decreased cystic areas, compared with Pkhd1del2/del2 mice (an animal model of PLD characterized by elevated Cdc25A levels and severe cystogenesis).8 In Cdc25A+/−:Pkhd1del2/del2 mice, compared with Pkhd1del2/del2 mice, we observed a 25% reduction of centrosomes per cell by number and a 35% reduction in fraction of cystic cholangiocytes with multiple centrosomes (Figure 9A). We also observed a decreased number of cilia per cell and a decreased percentage of multiciliated cholangiocytes (Figure 9B), as well as increased (by 36.7%) length of cilia (P < 0.05). In Cdc25A+/−:Pkhd1del2/del2 mice, more centrosomes (75.8%) were positioned closer to apical surface, compared with 39.7% in Pkhd1del2/del2 mice (P < 0.05). Moreover, consistent with previous report,8 cystic areas in Cdc25A+/−:Pkhd1del2/del2 mice were reduced to 28.35 ± 4.56%, compared with 44.96 ± 6.39% in Pkhd1del2/del2 mice (P < 0.05). These data show that depletion of Cdc25A levels in vivo can reverse the structural ciliary and centrosomal abnormalities seen in animal models of PLD (ie, Pkhd1del2/del2 mice).

Figure 9.

Effects of Cdc25A depletion on centrosomal and ciliary abnormalities in vivo. A and B: Confocal and light microscopy reveals the presence of centrosomes (γ-tubulin stain, green) (A) and ciliated cells (α-tubulin stain, red) (B) in bile ducts of C mice (Cdc25A+/−), P mice (Pkhd1del2/del2), and C:P mice (Pkhd1del2/del2:Cdc25A+/−). Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue). Basolaterally positioned centrioles are indicated by small white asterisks. An enlarged view of a cholangiocyte (arrow) with extra cilia is shown in the inset. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3 (C mice and C:P mice); n = 4 (P mice). ∗P < 0.05. Original magnification, ×100. L, bile duct or cyst lumen.

Discussion

We made the following findings in cystic cholangiocytes: i) numerous centrosomes, multipolar spindles and extra cilia are present; ii) the distance between mother and daughter centrioles is increased; iii) centrosomes have extra appendages and electrodense spots; iv) both centrosomes and primary cilia are improperly positioned; v) ciliogenesis is impaired, with reduced numbers of ciliated cells and with shorter cilia; vi) expression of Cdc25A and its downstream effectors that control centrosome duplication, Cdk2 and cyclin E, are up-regulated; vii) depletion of Cdc25A in vitro by molecular manipulations affects the cell cycle, decreases cell proliferation and the number of cells with multiple centrioles, improves ciliogenesis, and reduces growth of cystic structures in three-dimensional cultures; and viii) depletion of Cdc25A in vivo by genetic manipulation decreases the fraction of cholangiocytes with improperly positioned centrioles, supernumerary centrosomes, and extra cilia and subsequently attenuates hepatic cystogenesis. These data support the hypothesis that, in a benign hyperproliferative condition such as PLD, centrosomal abnormalities contribute to deregulation of ciliogenesis and cystogenesis and that the overexpression of Cdc25A plays an important role in this phenomenon.

The number of centrosomes is strictly controlled during the cell cycle. Disruption of centrosome duplication leads to centrosomal overamplification, atypical cytoarchitectural positioning, structural defects, formation of spindles with multiple poles, and aberrant ciliogenesis. Numerous centrosomal abnormalities have been described in cancer, and more recently also in kidney in animal models of PKD and also in humans with PKD.14,20,21,23,24,29,34

Here, we have reported for the first time that centrosome defects occur in cystic cholangiocytes of animal models and in humans affected by cystic liver diseases and have provided novel information on the mechanisms underlying these phenomena.

The potential consequences of centrosome hyperamplification might include nucleation of extra cilia and impaired ciliogenesis.11,20,23 Indeed, the number of multiciliated cystic cholangiocytes was increased in PLD. Cholangiocytes with overduplicated centrosomes and extra cilia represent a relatively small fraction, but a significant fraction compared with control. This reflects the nature of cyst formation as a slow-progressive event that involves a rather low number of bile ducts. It might also reflect the fact that cystic tissue comprises heterogeneous cell populations (ie, with both multiple and normal centrosome numbers), as is seen in cancer tissue.20

To assess the role of centrosomal cytoarchitectural defects in ciliogenesis, we isolated cholangiocytes from control and PCK rats and examined the growth of cilia over the course of 21 days. The PCK cholangiocytes had aberrant ciliogenesis; the number of ciliated cells was decreased, compared with control, and the cilia were shorter. Current evidence suggests that ciliary length is important for normal cell functioning and is relatively consistent within a cell type.17,35 We and others have shown that hepatic and renal cystogenesis in PKD is associated with either excessively long or short cilia.7,10,17,30 Our present findings suggest that ciliary growth is affected by centrosomal abnormalities. Subsequently, atypical cilia might not provide proper signaling into the cell interior to influence cell-cycle progression and precise centrosome duplication and/or positioning.

Primary cilia in any tubular epithelia are situated on the apical membrane; however, the positioning with respect to the cell center might vary depending on the cell type.36 Proper ciliary positioning is crucial for their optimal functioning, and incorrect ciliary localization is a hallmark of many ciliopathies.20,23,36 Our finding that the position of the basal body is atypical in cystic cholangiocyte is consistent with an abnormal cellular location of the cholangiocyte cilium; both centrosomes and cilia were found closer to the cell center than in control cells. In cystic cholangiocytes (but not in controls), centrosomes were also observed in basolateral membrane region. In accord with the present findings, centrosomes were reported to be improperly positioned in kidneys of a mouse model of PKD.37

The precise mechanisms responsible for centrosome amplification remain unclear. Centrosome duplication is initiated in the G1–S phase of the cell cycle and requires the coordinated functioning of the Cdk2–cyclin E complex, the activity of which is controlled by p53 and p21waf1/Cip1 and Cdc25A phosphatase.12,14,20,21,23 Although experimental evidence suggests that in many cancers centrosomal abnormalities are p53/p21–dependent,20,38 these defects have been also described in the absence of p53 deregulation.22,34 Indeed, levels of p53 and p21 were unchanged in cystic cholangiocytes, whereas expression of their downstream target, Cdk2–cyclin E, was elevated. The fact that cystogenesis is a benign hyperproliferative condition (as opposed to malignant cell growth) is potentially consistent with these differences.

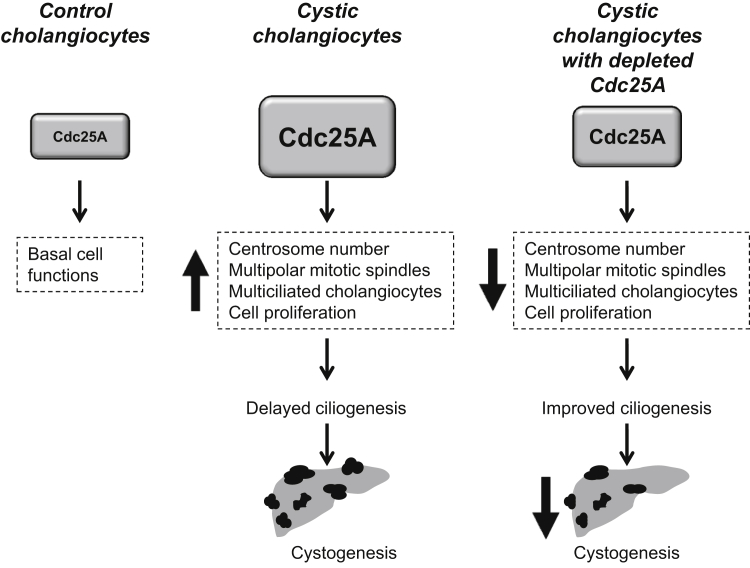

Our research group recently showed that the cell-cycle phosphatase Cdc25A (the upstream regulator of Cdk2–cyclin E) plays an important role in hepatic cystogenesis, and its targeting by either pharmacological or genetic manipulations reduces cyst growth in animal models of PLD.8 Furthermore, levels of Cdk2 and cyclin E are significantly reduced in response to Cdc25A inhibition.8 Finally, Cdc25A overexpression in cystic cholangiocytes is the result of the down-regulation of miR-15a, a miRNA with complementarity to Cdc25A mRNA.33 In the present study, to assess whether Cdc25A contributed to the centrosomal abnormalities in cystic cholangiocytes, we used three different approaches to deplete Cdc25A levels: Cdc25A shRNA and a miR-15a precursor in vitro and genetic manipulation through cross-breeding in vivo. Under experimental conditions of Cdc25A inhibition, virtually all of the centrosome and ciliary abnormalities in cystic cholangiocytes (ie, the number of centrioles per cell and the portion of multiciliated cholangiocytes and fraction of cells with improper ciliary positioning) were abrogated, reducing both proliferation and cyst growth. A working model for these phenomena is presented in Figure 10. Moreover, we had previously shown that suppression of miR-15a in control cholangiocytes up-regulates Cdc25A levels, subsequently increasing cell proliferation and cyst growth.33 Thus, taken together, our data suggest that Cdc25A is involved in maintenance of centrosome cytoarchitecture.

Figure 10.

Overexpression of Cdc25A in cystic cholangiocytes triggers centrosome defects, improper ciliogenesis, and cyst growth. Depletion of Cdc25A by different approaches affects centrosome cytoarchitecture, improves ciliogenesis, and decreases hepatic cystogenesis.

Although it has been shown that centrosomal abnormalities in cancer correlate with cell aneuploidy, recent evidence suggests that cells may retain the diploid karyotype even in the presence of excessive centrosomes.14,20,22 Indeed, cystic cholangiocytes are diploid.8 Moreover, aneuploidy in cancer occurs via a p53-dependent mechanism, but we detected no changes in p53 levels in cystic cholangiocytes. These findings further indicate that centrosomal abnormalities in a benign hyperproliferative disease such as PLD are linked to different intracellular pathways than in cancer.

In conclusion, we observed multiple centrosomal cytoarchitectural defects in cystic cholangiocytes. These were associated with multiciliated cholangiocytes, delayed ciliogenesis, and shortened cilia. Our data suggest that up-regulation of the cell-cycle phosphatase Cdc25A contributes to these events. The data further suggest that therapeutic interventions targeting Cdc25A might be of significant benefit in the treatment of PLD.

Footnotes

Supported by the NIH (grants R01-DK24031 to N.F.L., P30-DK084567 to the Clinical Core and Optical Microscopy Core of the Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology, and P30-DK090728 to the Mayo Translational Polycystic Kidney Disease Center), the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (grant FIS PI12/00380 to J.M.B.), the Department of Industry of the Basque Country (grant SAIO12-PE12BN002 to J.M.B.), and the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI).

T.V.M. and S.-O.L. contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Gevers T.J., Drenth J.P. Diagnosis and management of polycystic liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:101–108. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torres V.E., Harris P.C. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: the last 3 years. Kidney Int. 2009;76:149–168. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mochizuki T., Tsuchiya K., Nitta K. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: recent advances in pathogenesis and potential therapies. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013;17:317–326. doi: 10.1007/s10157-012-0741-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strazzabosco M., Somlo S. Polycystic liver diseases: congenital disorders of cholangiocyte signaling. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1855–1859. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siroky B.J., Guay-Woodford L.M. Renal cystic disease: the role of the primary cilium/centrosome complex in pathogenesis. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2006;13:131–137. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masyuk T.V., Huang B.Q., Ward C.J., Masyuk A.I., Yuan D., Splinter P.L., Punyashthiti R., Ritman E.L., Torres V.E., Harris P.C., LaRusso N.F. Defects in cholangiocyte fibrocystin expression and ciliary structure in the PCK rat. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masyuk T.V., Huang B.Q., Masyuk A.I., Ritman E.L., Torres V.E., Wang X., Harris P.C., Larusso N.F. Biliary dysgenesis in the PCK rat, an orthologous model of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1719–1730. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63427-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masyuk T.V., Radtke B.N., Stroope A.J., Bañales J.M., Masyuk A.I., Gradilone S.A., Gajdos G.B., Chandok N., Bakeberg J.L., Ward C.J., Ritman E.L., Kiyokawa H., LaRusso N.F. Inhibition of Cdc25A suppresses hepato-renal cystogenesis in rodent models of polycystic kidney and liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:622–633.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopp K., Ward C.J., Hommerding C.J., Nasr S.H., Tuan H.F., Gainullin V.G., Rossetti S., Torres V.E., Harris P.C. Functional polycystin-1 dosage governs autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease severity. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4257–4273. doi: 10.1172/JCI64313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avasthi P., Marshall W.F. Stages of ciliogenesis and regulation of ciliary length. Differentiation. 2012;83:S30–S42. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahjoub M.R., Stearns T. Supernumerary centrosomes nucleate extra cilia and compromise primary cilium signaling. Curr Biol. 2012;22:1628–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawe H.R., Farr H., Gull K. Centriole/basal body morphogenesis and migration during ciliogenesis in animal cells. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:7–15. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badano J.L., Teslovich T.M., Katsanis N. The centrosome in human genetic disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:194–205. doi: 10.1038/nrg1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukasawa K. Centrosome amplification, chromosome instability and cancer development. Cancer Lett. 2005;230:6–19. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burakov A., Nadezhdina E., Slepchenko B., Rodionov V. Centrosome positioning in interphase cells. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:963–969. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pelletier L. Centrioles: duplicating precariously. Curr Biol. 2007;17:R770–R773. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma N., Kosan Z.A., Stallworth J.E., Berbari N.F., Yoder B.K. Soluble levels of cytosolic tubulin regulate ciliary length control. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:806–816. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-03-0269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basto R., Lau J., Vinogradova T., Gardiol A., Woods C.G., Khodjakov A., Raff J.W. Flies without centrioles. Cell. 2006;125:1375–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pelletier L. Centrosomes: keeping tumors in check. Curr Biol. 2008;18:R702–R704. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bettencourt-Dias M., Hildebrandt F., Pellman D., Woods G., Godinho S.A. Centrosomes and cilia in human disease. Trends Genet. 2011;27:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunha-Ferreira I., Bento I., Bettencourt-Dias M. From zero to many: control of centriole number in development and disease. Traffic. 2009;10:482–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korzeniewski N., Hohenfellner M., Duensing S. The centrosome as potential target for cancer therapy and prevention. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2013;17:43–52. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.731396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nigg E.A., Raff J.W. Centrioles, centrosomes, and cilia in health and disease. Cell. 2009;139:663–678. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Battini L., Macip S., Fedorova E., Dikman S., Somlo S., Montagna C., Gusella G.L. Loss of polycystin-1 causes centrosome amplification and genomic instability. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2819–2833. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Happé H., Leonhard W.N., van der Wal A., van de Water B., Lantinga-van Leeuwen I.S., Breuning M.H., de Heer E., Peters D.J. Toxic tubular injury in kidneys from Pkd1-deletion mice accelerates cystogenesis accompanied by dysregulated planar cell polarity and canonical Wnt signaling pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2532–2542. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burtey S., Riera M., Ribe E., Pennenkamp P., Rance R., Luciani J., Dworniczak B., Mattei M.G., Fontés M. Centrosome overduplication and mitotic instability in PKD2 transgenic lines. Cell Biol Int. 2008;32:1193–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.AbouAlaiwi W.A., Ratnam S., Booth R.L., Shah J.V., Nauli S.M. Endothelial cells from humans and mice with polycystic kidney disease are characterized by polyploidy and chromosome segregation defects through survivin down-regulation. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:354–367. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hildebrandt F., Otto E. Cilia and centrosomes: a unifying pathogenic concept for cystic kidney disease? Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:928–940. doi: 10.1038/nrg1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee K., Battini L., Gusella G.L. Cilium, centrosome and cell cycle regulation in polycystic kidney disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:1263–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stroope A., Radtke B., Huang B., Masyuk T., Torres V., Ritman E., LaRusso N. Hepato-renal pathology in pkd2ws25/− mice, an animal model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:1282–1291. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woollard J.R., Punyashtiti R., Richardson S., Masyuk T.V., Whelan S., Huang B.Q., Lager D.J., vanDeursen J., Torres V.E., Gattone V.H., LaRusso N.F., Harris P.C., Ward C.J. A mouse model of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease with biliary duct and proximal tubule dilatation. Kidney Int. 2007;72:328–336. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masyuk T.V., Radtke B.N., Stroope A.J., Bañales J.M., Gradilone S.A., Huang B., Masyuk A.I., Hogan M.C., Torres V.E., LaRusso N.F. Pasireotide is more effective than octreotide in reducing hepato-renal cystogenesis in rodents with polycystic kidney and liver diseases. Hepatology. 2013;58:409–421. doi: 10.1002/hep.26140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee S.O., Masyuk T., Splinter P., Bañales J.M., Masyuk A., Stroope A., LaRusso N. MicroRNA15a modulates expression of the cell-cycle regulator Cdc25A and affects hepatic cystogenesis in a rat model of polycystic kidney disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3714–3724. doi: 10.1172/JCI34922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gergely F., Basto R. Multiple centrosomes: together they stand, divided they fall. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2291–2296. doi: 10.1101/gad.1715208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharma N., Berbari N.F., Yoder B.K. Ciliary dysfunction in developmental abnormalities and diseases. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;85:371–427. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00813-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farnum C.E., Wilsman N.J. Axonemal positioning and orientation in three-dimensional space for primary cilia: what is known, what is assumed, and what needs clarification. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:2405–2431. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jonassen J.A., San Agustin J., Follit J.A., Pazour G.J. Deletion of IFT20 in the mouse kidney causes misorientation of the mitotic spindle and cystic kidney disease. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:377–384. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200808137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hemerly A.S., Prasanth S.G., Siddiqui K., Stillman B. Orc1 controls centriole and centrosome copy number in human cells. Science. 2009;323:789–793. doi: 10.1126/science.1166745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]