Background: C. elegans BAG neurons respond to environmental CO2.

Results: By isolating BAG neurons in culture, we show that they detect CO2 independently of intracellular or extracellular acidosis or bicarbonate.

Conclusion: C. elegans BAG neurons detect molecular CO2.

Significance: Cells can directly detect the respiratory gas CO2 using dedicated receptors. Similar mechanisms might mediate some of the effects of CO2 on other physiological systems.

Keywords: C. elegans, Carbon Dioxide, Cyclic GMP (cGMP), Neurons, Receptors, Chemotransduction

Abstract

Animals from diverse phyla possess neurons that are activated by the product of aerobic respiration, CO2. It has long been thought that such neurons primarily detect the CO2 metabolites protons and bicarbonate. We have determined the chemical tuning of isolated CO2 chemosensory BAG neurons of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. We show that BAG neurons are principally tuned to detect molecular CO2, although they can be activated by acid stimuli. One component of the BAG transduction pathway, the receptor-type guanylate cyclase GCY-9, suffices to confer cellular sensitivity to both molecular CO2 and acid, indicating that it is a bifunctional chemoreceptor. We speculate that in other animals, receptors similarly capable of detecting molecular CO2 might mediate effects of CO2 on neural circuits and behavior.

Introduction

Carbon dioxide is detected by animals as an environmental cue that indicates the presence of prey, hosts, or mates and is also detected as an internal cue that reflects the metabolic state of the organism (1, 2). In both contexts, the nervous system mediates responses to increases in CO2. Olfactory and gustatory sensory systems of insects and mammals contain neurons that are activated by CO2 (3–5). Also, neurons of the vertebrate central nervous system that control respiration are highly sensitive to changes in blood levels of CO2 (6–10). Understanding the molecular mechanisms of neuronal CO2 chemosensitivity is therefore a central question in the study of many physiological and behavioral processes.

In solution, where it would be sensed by neurons, CO2 generates multiple chemical species. CO2 reacts with water to form carbonic acid, which almost instantly dissociates to produce protons and bicarbonate ions. The CO2 hydration reaction can occur rapidly in biological systems because of the catalytic action of carbonic anhydrase (CAH)3 enzymes (11). CO2-sensing neurons, therefore, encounter CO2 in equilibrium with the major products of its hydration: protons and bicarbonate ions. In many cases, neurons that respond to increases in CO2 levels have been found to respond to one or the other of these CO2 metabolites. For example, CO2-sensitive areas of vertebrate respiratory centers and the amygdala are highly sensitive to changes in extracellular pH (12–16). Also, CO2-responsive gustatory and olfactory neurons can be activated by acid or bicarbonate, respectively (5, 17, 18). The sensitivity of many different types of neurons to CO2 metabolites is the basis for the hypothesis that the effects of CO2 on neural physiology are mediated by CO2 metabolites rather than by CO2 itself.

The sensory nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans offers an excellent opportunity for the study of molecular mechanisms used by neurons to detect CO2. C. elegans possesses a pair of CO2-sensing neurons, the BAG neurons, which mediate acute avoidance of CO2 by adults and attraction to CO2 by Dauer larvae (19–21). To sense CO2, BAG neurons require a cGMP signaling pathway. The BAG cell-specific receptor-type guanylate cyclase GCY-9 and heteromeric TAX-2/TAX-4 cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels are required both for cellular responses to CO2 and for BAG cell-dependent behaviors (19, 21–23). The GCY-9 cyclase and CNG channels likely constitute the core of the molecular machinery that endows BAG neurons with CO2 chemosensitivity; expression of GCY-9 in sensory neurons that use cGMP signaling is sufficient to mediate calcium responses to CO2 stimuli (24).

Although components of a transduction pathway that mediates CO2 sensing by BAG neurons have been identified, it was not known whether BAG neurons are principally tuned to detect CO2 or CO2 metabolites. Unlike many chemosensory neurons of C. elegans, BAG neurons are completely contained within the animal and not in contact with the external environment (25, 26). It is therefore not possible to determine whether BAG neurons sense CO2 or CO2 metabolites by simply exposing intact animals to these stimuli. In such an experiment, the intrinsic tuning properties of the neuron would be convolved with the relative permeability of the cuticle and hypoderm to different chemical cues. To identify the specific chemical cue that activates BAG neurons, we studied isolated BAG neurons in culture, using methods that allow both monitoring of cell physiology and control of the extracellular and intracellular environments.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

C. elegans Strains Used

Strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains were grown on 6-cm NGM agar plates at 20 °C or 25 °C on Escherichia coli OP50. Conditions for culturing strains used for embryonic cell culture are described below. Transgenic animals were created using standard procedures (27). In some cases, extrachromosomal transgenes were integrated using gamma-irradiation (5,000 rads).

TABLE 1.

| Strain | Genotype | Strain description |

|---|---|---|

| FQ31 | nIs326[Promgcy-33::YC3.60]; gcy-33 (ok232); gcy-31 (ok296) | Calcium indicator YC3.60 expressed using a BAG-specific promoter (gcy-33); gcy-31 and gcy-33 deleted |

| FQ243 | wzIs82[Promgcy-9::YC3.60 lin-15 (+)]; lin-15AB (n765) | YC3.60 expressed using a BAG-specific promoter (gcy-9) |

| FQ301 | fxIs105[Promgcy-8::YC3.60]; wzEx34[Promgcy-18::gcy-9] | YC3.60 and GCY-9 expressed using AFD-specific promoters (gcy-8 and gcy-18, respectively) |

| FQ323 | wzIs96[Promgcy-32::YC3.60] | YC3.60 expressed using a URX-specific promoter (gcy-32) |

| FQ340 | lin-15AB (n765); wzEx36[Promflp-17::dsRed lin-15 (+)] | dsRed expressed using a BAG-specific promoter (flp-17) |

| FQ401 | wzIs115[Promrab-3::YC3.60] | YC3.60 expressed using a pan-neuronal promoter (rab-3) |

| FQ439 | wzIs118[Promgcy-18::gcy-9]; fxIs105[Promgcy-8::YC3.60] | GCY-9 and YC3.60 expressed using AFD-specific promoters (gcy-18 and gcy-8, respectively) |

| FQ494 | wzIs131[flp-17::venus] | FLP-17 fused to Venus (YFP variant) |

| FQ518 | nIs326[Promgcy-33::YC3.60]; gcy-9 (tm2816) | YC3.60 expressed using a BAG-specific promoter (gcy-33); gcy-9 deleted |

| FQ522 | gcy-18 (nj37) gcy-8 (oy44) gcy-23 (ny38); fxIs105[Promgcy-8::YC3.60]; wzEx34[Promgcy-18::gcy-9] | YC3.60 and GCY-9 expressed using AFD-specific promoters (gcy-8 and gcy-18, respectively); gcy-18, gcy-8 and gcy-23 deleted |

| FQ523 | wzIs131[flp-17::venus]; gcy-9 (tm2816) | FLP-17 fused to Venus (YFP variant); gcy-9 deleted |

| MT18636 | nIs326[Promgcy-33::YC3.60] | YC3.60 expressed using a BAG-specific promoter (gcy-33) |

| OH441 | otIs45[Promunc-119::GFP] | GFP expressed using a pan-neuronal promoter (unc-119) |

| PX433 | fxIs105[Promgcy-8::YC3.60] | YC3.60 expressed using an AFD-specific promoter (gcy-8) |

Embryonic Cell Culture

Embryonic cell cultures were prepared as previously described (28–30). Briefly, strains were grown at 15–25 °C on ten 10-cm peptone agar plates seeded with OP50 E. coli. Eggs from gravid adults were released by bleaching and isolated on a 30% sucrose gradient (12,000 rpm, 5 min). Eggs were recovered to an NGM agar plate without bacteria and allowed to hatch at 20 °C overnight. Hatched L1 larvae were collected in double distilled H2O, spun down (1,000 rpm, 3 min), and washed again before plating onto 10-cm peptone agar plates seeded with OP50 E. coli. Synchronized worms were grown until gravid, and then eggs were isolated as described above for the preparation of dissociated embryonic cells. For dissociation, eggs were resuspended in 500 μl of chitinase solution (1 unit/ml; Sigma) and gently rocked for ∼30 min at room temperature until ∼80% of eggshells were digested, which was monitored by examining aliquots of the suspension using an Axioskop 2 microscope (Zeiss). 800 μl of culture medium was added to inactivate the chitinase, and cells were pelleted at 3,500 rpm for 3 min at 4 °C; culture medium consisted of: Leibowitz's L-15 medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (HyClone) and adjusted to an osmolality of 340 ± 5 mOsm using sucrose. After resuspension in culture medium, eggs were titurated using a 1-ml syringe and a 27-gauge needle until ≥75% of the suspension consisted of single cells. Disruption of embryos was monitored using an upright microscope. Cells were subsequently pelleted and resuspended in 500 μl of culture medium, and the suspension was then pushed through a 5-μm Durapore filter (Millipore) to remove larvae and cell clumps as follows. After filtration, cells were pelletted, resuspended, and seeded at a density of 250,000 cells/dish on glass-bottomed dishes (MatTek) that had been acid washed and coated with peanut lectin (0.5 mg/ml, Sigma). Cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator at 25 °C.

In Vitro Calcium Imaging

Prior to imaging, cells were rinsed with control solution: 145 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm HEPES, and 10 mm glucose, adjusted to pH 7.2 with NaOH and 340 ± 5 mOsm using sucrose. Cells were illuminated with 435-nm excitation light and imaged using a 40× Nikon long working distance objective (0.75 numerical aperture). CFP and YFP emissions were passed through a DV2 image splitter (Photometrics), and the CFP and YFP emission images were projected onto two halves of a cooled CCD camera (Andor). Images were acquired at 10 Hz with an exposure time of 50 ms. Excitation light, image acquisition, and hardware control were performed by the Live Acquisition software package (Till Photonics). Stimuli were delivered using a multichannel perfusion pencil (AutoMate Scientific). During imaging, cells were continuously superfused with control solution (unless stated otherwise) that was administered from a fixed distance. The standard stimulus length was 5 s. The standard stimulus used to test for CO2 sensitivity of cultured cells was produced by continuously bubbling 10% CO2 (Airgas) into a solution containing 112 NaCl, 33 mm NaHCO3, 5 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, and 10 mm glucose, pH 7.2, and adjusted to 340 ± 5 mOsm using sucrose. In experiments conducted to determine the percentage of neurons that responded to a given stimulus, a KCl solution (100 mm, substituted with NaCl from control solution) was administered at the end of each experiment to evaluate cell viability. Cells that failed to produce a response to KCl were not included in further analysis. 100 mm KCl was used because previous work demonstrated that cultured C. elegans neurons that fail to respond to 40 or 60 mm KCl are frequently depolarized by 100 mm KCl (31).

In Vivo Calcium Imaging

Calcium imaging was conducted as described previously (21, 24). Adult worms were immobilized with cyanoacrylate veterinary glue (Surgi-Lock; Meridian Animal Health) on a 2% agarose pad made with 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, which filled the 10-mm glass well of a 35-mm glass-bottomed dish (MatTek). The worm was subsequently submerged in control solution (see in vitro calcium imaging), and a 10% CO2 or heat stimulus was delivered using a perfusion pencil. One perfusion line was heated by a custom-built thermoelectric heating block. The heated line was used to administer a 10-s heat ramp that spanned 25.5–28.5 °C. The thermal stimulus was calibrated using a micro-thermocouple (Omega).

The mean pixel value of a background region of interest was subtracted from the mean pixel value of a region of interest encompassing the cell body, for both in vitro and in vivo experiments. A correction factor, which we measured in images of samples that express only CFP, was applied to the YFP channel to compensate for bleed through of CFP emissions into the YFP channel (YFPadjusted = YFP − 0.86 × CFP). YFP to CFP ratios were normalized to the average value of the first 10 frames (1 s), and a boxcar filter of three frames (0.3 s) was applied to the time series using Igor (Wavemetrics). To determine whether a cell responded to CO2 or acid, a threshold was used whereby the average amplitude at 10–20 s had to be greater than the average base-line amplitude (0–10 s) + two standard deviations. Peak amplitudes were measured by subtracting the average base-line value for the 10 s prior to stimulus administration from the peak response amplitude. Post-acquisition analysis of ratio plots was performed using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc.).

Measurement of Intracellular pH

Intracellular pH (pHi) was determined by loading cells with the acetoxymethylester form of the pH-sensitive fluorophore 2′,7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein (BCECF) (2 μm, 20 min, 25 °C, Invitrogen). BCECF has a pKa of 6.97 and is thus ideal for measuring changes in intracellular pH, previous studies having demonstrated CO2-evoked intracellular acidification (32, 33). Emissions generated at 535 nm in response to excitation at 440 and 490 nm were collected (0.25 Hz), and the ratio490/440 was plotted. The ratio490/440 was converted to pHi values following construction of a calibration curve using 100 mm KCl solutions, containing 10 μm of the K+-H+ exchanger nigericin, buffered with HEPES across the pH range 6.0–8.0. After 2 min of equilibration at pH 7.0, cells were exposed to 30 s of each solution across the pH range; emission at 535 nm was collected at 0.3 Hz. For each cell, the last three measurements for each solution were averaged to produce a ratio490/440 value for each cell at each pH. The values from cells were averaged, and a linear regression was performed to transform ratio490/440values into pHi values.

Measurement of FLP-17::Venus Destaining

Embryonic cultures were made from worms expressing the neuropeptide FLP-17 in BAG neurons under the flp-17 promoter. Regions of interest were neurites containing puncta of FLP-17::Venus fluorescence; cell bodies were excluded from our analysis. Venus emissions generated by excitation at 515 nm were acquired at 10 Hz with an exposure time of 50 ms. The mean pixel value of a background region of interest was subtracted from the mean pixel value of a region of interest encompassing the neurite of the cell of interest. YFP values were normalized to the average value of the first 10 frames (1 s), and a boxcar filter of three frames (0.3 s) was applied to the time series using Igor (Wavemetrics). Individual traces were corrected for base-line drift using simple exponential curve fits to prestimulus fluorescence measurements. To classify a cell as responding to a stimulus, the average fluorescence value at 20–25 s had to be greater than the initial 0–10 s fluorescence value + 2 standard deviations; cells not meeting this criterion in response to KCl were excluded from analysis, and those meeting these criteria for CO2 were classified as responders.

Solutions and Drugs

In addition to solutions described above, the following solutions were used. Solutions of varying pH were applied by altering the pH of the control solution using NaOH. In CO2 dose-response curve experiments, NaCl was substituted with NaHCO3 to obtain pH 7.2 for a given percentage of CO2 bubbled through the solution: 2%, 5.75 mm; 1%, 2.5 mm; 0.5%, 1.7 mm; 0.2%, 1 mm; 0.1%, 0.4 mm; and 0.05%, 0.275 mm. A different percentage of CO2 was produced by mixing 2% CO2 with atmospheric air using adjustable flow meters (Cole Palmer). Continuous bubbling of solutions with a known percentage of CO2 allowed us to calculate the molar concentration of CO2 assuming: a temperature of 25 °C and thus a PH2O of 23.68 mm Hg, a barometric pressure of 760 mm Hg, saturation of a solution with the percentage of gas being bubbled, and a CO2 solubility of 0.031 mm/mm Hg. Thus [CO2] for a solution bubbled with 10% CO2: (760–23) × 10% × 0.031 = 2.283 mm.

To alter the ratio of CO2 to protons/bicarbonate in solution, 0.7 mm NaHCO3 was added to solutions buffered to pH 7.2 and 7.9, which, assuming a pKa of 6.35 for H2CO3, would result in 90 and 20 μm CO2, respectively. A further solution containing 3.25 mm NaHCO3 at pH 7.9 was also used, which like the pH 7.2 solution containing 0.7 mm NaHCO3, contains 90 μm CO2.

The following reagents, all from Fisher Scientific unless otherwise stated, were also used: acetazolamide (Sigma), allyl isothiocyanate (Acros Organics), CdCl2 (Acros Organics), H2S (RICCA Chemical), hexamethylene-diisocyanate (Acros Organics), methazolamide, nemadipine-A (Santa Cruz), punicalagin (Sigma), CS2, DETA/NO (Sigma), thapsigargin (Sigma), and tricarbonyldichlororuthenium(II) dimer (Sigma).

Microscopy

Fluorescence and differential interference contrast micrographs were acquired either with a wide field inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon) or an LSM510 laser-scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss). Images were processed using ImageJ.

Statistics

Statistical tests were performed used GraphPad Prism. Statistical comparisons were made using a paired t test or unpaired t test, apart from the dose-response curve in Fig. 2C, which was fitted with a variable slope model.

FIGURE 2.

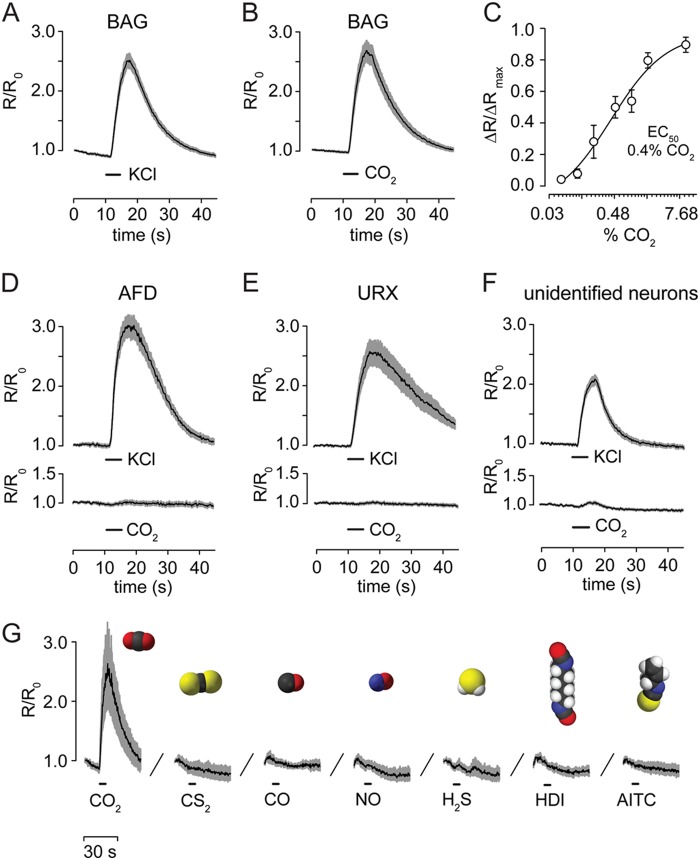

Isolated BAG neurons display CO2 chemosensitivity. A, calcium responses of cultured BAG neurons to depolarization (n = 68). B, calcium response of cultured BAG neurons to 10% CO2 in equilibrium with 33 mm bicarbonate pH 7.2 (n = 47). C, dose-response curve of BAG neuron responses to different CO2 solutions brought to pH 7.2 with bicarbonate. EC50 = 0.42%. D–F, calcium responses of cultured AFD (n = 47), URX (n = 44), and unidentified (n = 144) neurons. G, BAG neurons are not activated either by signaling gases (30 μm CO, 4.5 μm NO, and 50 μm H2S) or by compounds known to activate CO2-responsive neurons of other species (10 μm CS2, 5 μm HDI, and 20 μm AITC) (n = 6).

RESULTS

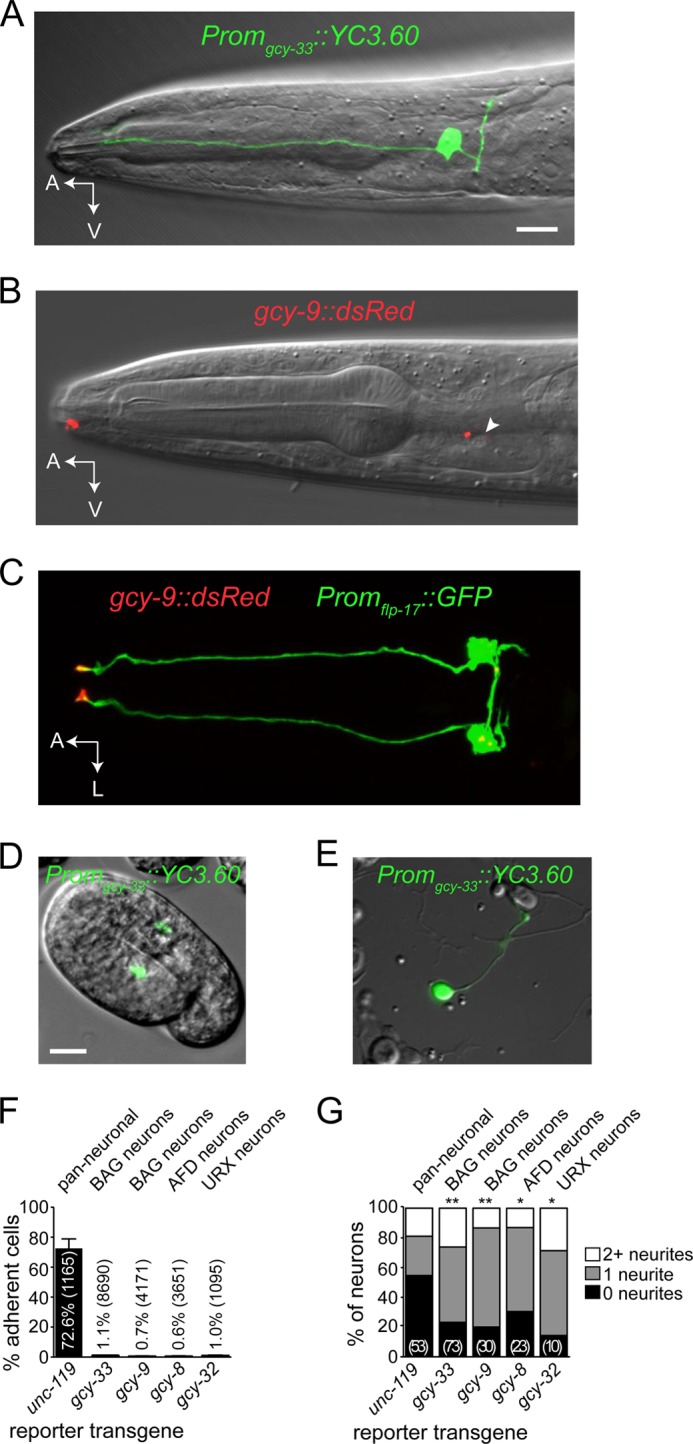

CO2-responsive BAG neurons are located in the head and extend ciliated processes toward the nose (Fig. 1A). These processes are not in contact with the external environment (25, 26). We observed that the receptor-type guanylate cyclase GCY-9, which is an essential component of the sensory transduction apparatus in BAG neurons and is likely to function as part of a receptor complex (24), is enriched in the terminus of the BAG cell neurite (Fig. 1, B and C). The CO2 transduction apparatus of BAG neurons is therefore in a cellular compartment that is not in direct contact with the external environment and is experimentally inaccessible. To determine the chemical tuning of BAG neurons, we therefore sought to isolate BAG neurons and study their sensitivity to CO2 and other stimuli in vitro.

FIGURE 1.

CO2-responsive BAG neurons of C. elegans in situ and in culture. A, BAG-neuron-specific expression of the Promgcy-33::YC3.60 calcium sensor transgene in an adult C. elegans hermaphrodite. B, in situ expression of the receptor-type guanylate cyclase GCY-9 tagged with dsRed (red channel) overlaid on a differential interference contrast image of the head (gray channel). GCY-9 is enriched in a compartment in the nose, where the sensory neurite ends (arrow). Arrowhead, BAG neuron nucleus. C, subcellular localization of GCY-9::dsRed (red channel) in a BAG neuron expressing soluble GFP (green channel). D and E, expression of Promgcy-33::YC3.60 in embryonic BAG neurons in situ (D) and in vitro (E) following dissociation. Scale bars, 10 μm. F, frequency of reporter transgene expression by neurons isolated from strains containing markers for sensory neuron populations. G, morphometric analysis of cultured neurons that express different neuronal markers. The number of cells analyzed is indicated in parentheses. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared with unc-119.

We cultured cells from C. elegans embryos expressing the ratiometric calcium indicator YC3.60 in BAG neurons (Fig. 1, A, adults, and D, late stage embryos) and could readily find YC3.60-expressing neurons in culture (Fig. 1E). Approximately 1% of adherent cells were BAG neurons, and we observed a similar frequency for other sensory neurons when cultures were prepared from different transgenic strains (Fig. 1F). Although BAG neurons in situ are bipolar (Fig. 1A), not all BAG neurons extended two processes in vitro; they did, however, extend neurites more frequently than did unidentified neurons (Fig. 1G).

Isolated BAG neurons responded to a brief depolarizing stimulus (100 mm KCl) as shown by BAG cell calcium responses (Fig. 2A). We next stimulated BAG neurons with 33 mm NaHCO3 in equilibrium with 10% atmospheric CO2, pH 7.2, to determine whether they functioned in vitro as sensors for CO2 or its metabolites. A majority of cells (69%) responded to this stimulus and displayed large calcium responses (Fig. 2B). The chemosensitivity of cultured BAG neurons was similar to the sensitivity of BAG neurons in situ, which we previously measured: the EC50 of CO2 for activation of isolated BAG neurons was 0.4% CO2 (Fig. 2C), compared with 0.9% CO2 for activation of BAG neurons in situ (21). BAG neuron CO2 chemosensitivity is therefore cell intrinsic and does not require interactions with other cells.

We next tested whether intrinsic CO2 sensitivity is specific to BAG neurons. Others have reported CO2-evoked calcium responses in thermosensory AFD neurons (23). In vitro, however, AFD neurons did not respond to CO2, although they did respond to depolarization (Fig. 2D). Similarly, neither oxygen-sensing URX neurons (Fig. 2E) nor unidentified neurons displayed robust CO2 responses in vitro (Fig. 2F). Intrinsic CO2 chemosensitivity is therefore specific to BAG neurons. We stimulated BAG neurons with a panel of compounds that either are chemically similar to CO2, activate CO2-responsive neurons of other organisms, or are gases with known roles in physiological signaling. None of these compounds activated BAG neurons, suggesting that BAG neurons are narrowly tuned to detect CO2 or its metabolites (Fig. 2G).

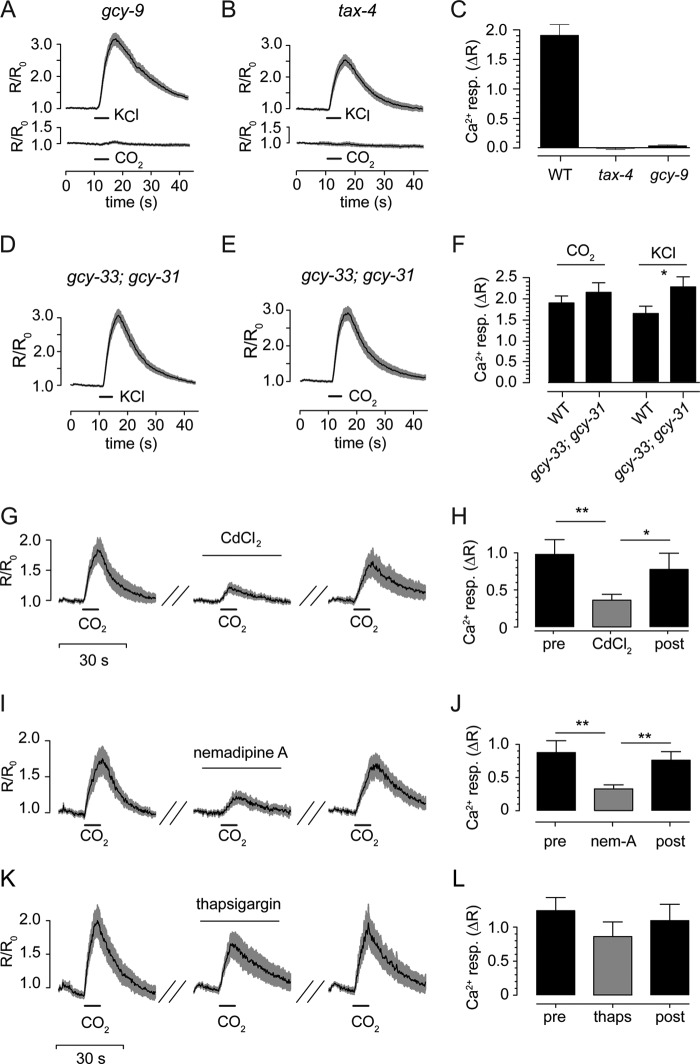

Isolated BAG neurons, like BAG neurons in situ (21), required GCY-9 and TAX channels to respond to CO2 stimuli (Fig. 3, A–C). By contrast, the GCY-31/GCY-33-soluble guanylate cyclase, which was proposed to function in CO2 sensing by BAG neurons (23), was not required for CO2 responses of isolated BAG neurons (Fig. 3, D–F). We observed that BAG neuron calcium responses were reversibly blocked by the nonselective voltage-gated calcium channel (CaV) blocker CdCl2 (Fig. 3, G and H), and a similar effect was observed with nemadipine-A, which targets the sole L-type CaV expressed by C. elegans, EGL-19 (34, 35) (Fig. 3, I and J). These data demonstrate a critical role for L-type CaVs in CO2 sensing by BAG neurons. Disrupting intracellular calcium stores by blocking the SERCA calcium pump with thapsigargin did not significantly affect BAG neuron function (Fig. 3, K and L), suggesting that release of calcium from intracellular stores plays little or no role in activation of BAG neurons by CO2.

FIGURE 3.

BAG neuron chemotransduction requires cGMP signaling and L-type Ca2+ channels. A and B, responses of cultured BAG neurons lacking GCY-9 (n = 54) or TAX-4 (n = 23) to depolarization and 10% CO2. C, peak amplitudes summarized. D–F, calcium responses of gcy-33; gcy-31 mutant BAG neurons to CO2 (n = 42) and KCl (n = 56). Mutant cells displayed no significant difference in the amplitude of CO2 response compared with wild-type cells (n = 47) but significantly greater KCl responses compared with wild-type cells (n = 68). G and H, nonselective CaV blockade by 500 μm CdCl2 reversibly inhibited CO2-evoked calcium responses in BAG neurons (n = 10). I and J, reversible blockade of BAG cell responses to CO2 was observed using 10 μm nemadipine-A, an inhibitor of L-type CaVs (n = 8). K and L, depletion of intracellular calcium stores by treatment with 1 μm thapsigargin had a small effect upon CO2-evoked calcium responses in BAG neurons that did not attain threshold for statistical significance (n = 17). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

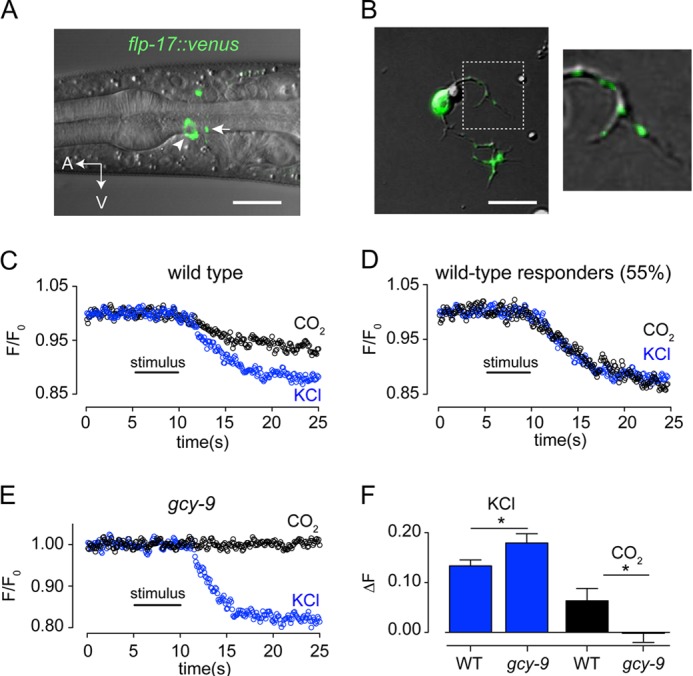

We next sought to assay activation of BAG neurons using a method that was independent of calcium imaging. BAG neurons express a number of neuropeptides, including FLP-17, which modulates activity of the egg laying system (36). We tested whether a FLP-17::Venus fusion would allow us to measure evoked exocytosis of neuropeptides from BAG neurons in response to CO2 stimuli. In adults, FLP-17::Venus was in the cell soma and puncta in the posterior neurite (Fig. 4A). In cultured BAG neurons FLP-17::Venus was similarly distributed (Fig. 4B). Both depolarization and CO2 stimuli evoked a stepwise decrease in FLP-17::Venus fluorescence in the neurites of cultured BAG neurons (Fig. 4C). We noted that the average destaining response of BAG neurons to CO2 stimuli was less than the destaining caused by depolarization (Fig. 4C) and found that this was because some BAG neurons that released peptide in response to KCl failed to release peptide in response to CO2. When we analyzed the destaining of neurons that responded to both KCl and CO2 (55% of the neurons tested), we found that the destaining responses to these two stimuli were of comparable magnitude (Fig. 4D). CO2-evoked peptide release required the CO2 transduction pathway: gcy-9 mutant BAG neurons displayed KCl-induced destaining, but did not respond to CO2 (Fig. 4, E and F).

FIGURE 4.

Isolated BAG neurons release neuropeptides in response to CO2 stimuli. A, in situ localization of FLP-17 neuropeptides tagged with Venus. White arrows indicate puncta in the presynaptic neurite of the BAG neuron. B, FLP-17::Venus expression in isolated BAG neurons was observed as puncta in neurites (inset). C, release of FLP-17::Venus from neurites of cultured BAG neuron in response to KCl-induced depolarization and 10% CO2 (n = 20). Average of all cells tested, including CO2-insensitive cells. D, average responses of CO2-responsive cells. E, release of FLP-17::Venus from isolated gcy-9 mutant BAG neurons in response to depolarization and 10% CO2 (n = 21). F, summary of peptide release by wild-type and gcy-9 mutant BAG neurons in response to depolarization and CO2. Scale bars indicate 5 μm. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

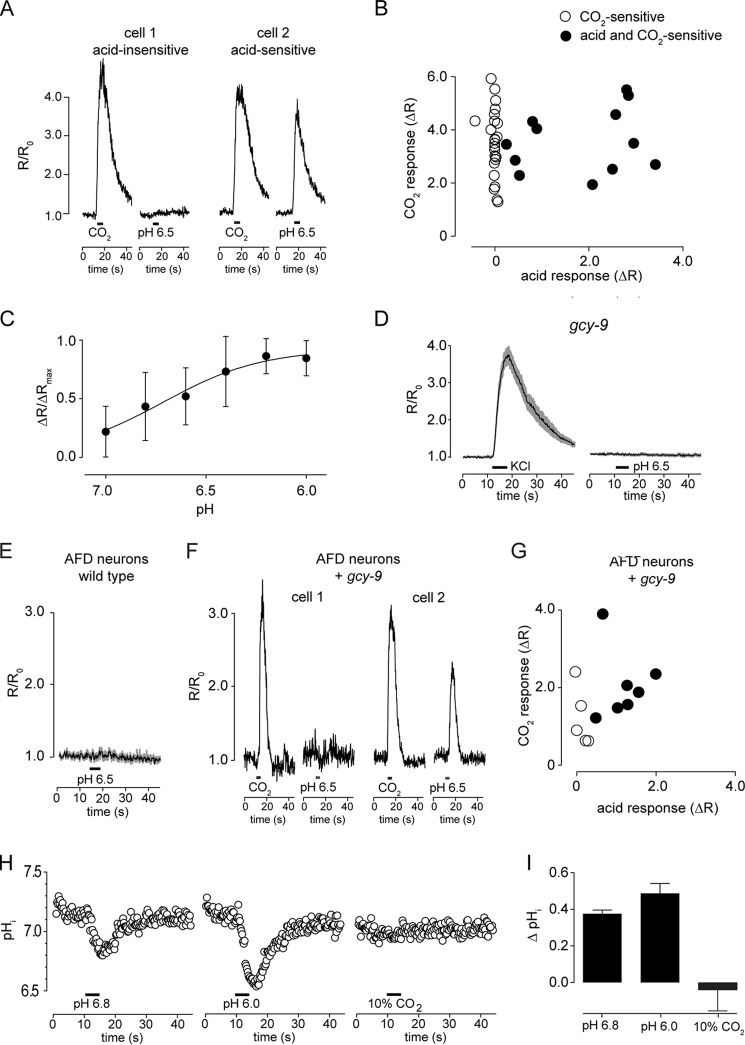

By multiple criteria, therefore, isolated BAG neurons in vitro retain their function as CO2 chemosensors. We therefore proceeded to use BAG neurons in culture to determine whether they are principally tuned to CO2 itself or the products of CO2 hydration: protons and bicarbonate ions. We first tested whether BAG neurons are proton sensors by exposing them to sequential CO2 (10%) and pH 6.5 acid stimuli. A majority of cells responded robustly to CO2, but not to acid (24 of 36). However, some BAG neurons (12 of 36) responded to both stimuli (Fig. 5, A and B). The magnitude of the calcium responses increased with increasing proton concentrations over a range of pH 7 to pH 6 with half-maximal responses observed at pH 6.7 (Fig. 5C). Like CO2 sensitivity, BAG neuron acid sensitivity required the receptor-type guanylate cyclase GCY-9 (Fig. 5D). Unidentified neurons in culture failed to respond to acid (data not shown), indicating that acid sensitivity is not widespread among C. elegans neurons. Thermosensory AFD neurons were also insensitive to acid (Fig. 5E), but expression of GCY-9 conferred acid sensitivity to a fraction of AFD neurons (Fig. 5, F and G). Together, these data indicate that acid sensing and CO2 sensing by BAG neurons are mediated by a common transduction pathway.

FIGURE 5.

BAG neurons respond to CO2 in the absence of extracellular and intracellular acidosis. A, representative responses of BAG neurons that responded only to CO2 (cell 1) or to both CO2 and acid (cell 2). B, summary of BAG neuron responses to CO2 and acid stimuli. Responses of CO2-selective cells are plotted in black (n = 24) and responses of cells that responded both to CO2 and acid are plotted in white (n = 12). C, dose-response curve for activation of BAG neurons by acid, EC50 = pH 6.71 (n = 13). D, gcy-9 mutant BAG neurons, which do respond to depolarization (left panel), were not activated by acid (right panel) (n = 29). E, wild-type AFD neurons were acid-insensitive (n = 14). F and G, GCY-9 expression conferred both CO2 and acid sensitivity (n = 12). H, intracellular pH measured using the pH indicator dye BCECF showed that acidic solutions cause intracellular acidosis, but CO2 stimuli do not (n = 6). I, peak changes summarized.

Although BAG neurons can be activated by acid, it remained unclear whether the acid sensitivity of BAG neurons is the mechanism by which they detect CO2. If BAG neurons detect CO2 via acid, how is it that CO2 better activates these cells? One possibility is that BAG neurons might respond to changes in intracellular pH. Although CO2 might readily permeate cell membranes to generate protons intracellularly, protons generally require transport mechanisms to cross cell membranes. This model demands that CO2 stimuli change intracellular pH. We measured the intracellular pH of BAG neurons during presentation of acid and CO2 stimuli and found that although the intracellular pH of BAG neurons rapidly responded to extracellular acid, 10% CO2 did not affect intracellular pH (Fig. 5, H and I). The activation of BAG neurons by CO2, therefore, can occur independently of either extracellular or intracellular acidosis.

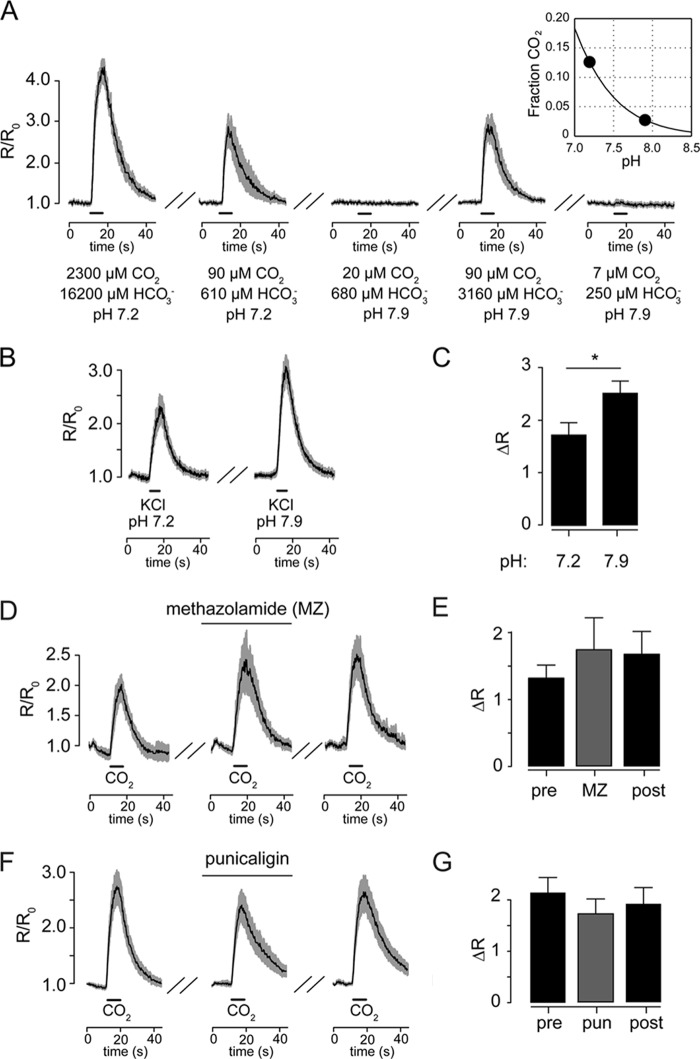

If BAG neurons sense CO2 in an acid-independent manner, alkaline solutions containing CO2 should also activate BAG neurons. We tested CO2 solutions at different pH to determine whether this was the case. A fixed amount of bicarbonate in solution at pH 7.2 generates 4.5-fold more CO2 that it does at pH 7.9 (Fig. 6A, inset). A pH 7.2 bicarbonate solution predicted to contain the EC50 for CO2 (90 μm) evoked large calcium responses from BAG neurons in culture, whereas the same solution at pH 7.9 (20 μm CO2) did not (Fig. 6A). Increasing the bicarbonate concentration at pH 7.9 so as to generate 90 μm CO2, we observed calcium responses indistinguishable from those evoked by a 90 μm CO2 stimulus at pH 7.2 (Fig. 6A). Importantly, weak alkalinization (pH 7.2 versus 7.9) did not inhibit BAG neuron sensitivity to KCl-evoked depolarization; by contrast, depolarization-induced calcium responses were increased by mild alkaline conditions (Fig. 6, B and C). Thus BAG neuron responses to CO2 solutions are proportionate to the concentration of molecular CO2 and are unaffected by increased pH. Furthermore, these experiments indicate that BAG neurons are not activated by bicarbonate, which has been proposed to mediate some cellular responses to CO2 (17, 18, 37). To further confirm that BAG neurons sense molecular CO2, we determined whether CAH is required for CO2 sensing. Some CO2-responsive neurons require CAH, which catalyzes the hydration of CO2, suggesting that these neurons are tuned to detect either protons or bicarbonate, not CO2 itself (5, 17). Inhibiting CAH using two chemically distinct inhibitors of carbonic anhydrase, methazolamide (Fig. 6, D and E) and punicaligin (Fig. 6, F and G), did not affect BAG neuron CO2 responses, further suggesting that BAG neurons directly detect molecular CO2.

FIGURE 6.

BAG neurons detect molecular CO2. A, BAG neuron responses to 10% CO2 (first panel) and 700 μm NaHCO3 at pH 7.2 (90 μm CO2), 700 μm NaHCO3 at pH 7.9 (20 μm CO2), 3250 μm NaHCO3 at pH 7.9 (90 μm CO2), and pH 7.9 solutions in equilibrium with room air (7 μm CO2) (n = 8). The inset shows the predicted amount of CO2 as a fraction of total dissolved carbonate species CO2 at different pH, highlighting conditions used here: pH 7.2 (green) and pH 7.9 (blue). B and C, KCl-evoked calcium responses in cultured BAG neurons are significantly larger in amplitude at pH 7.9 (n = 18) compared with pH 7.2 (n = 19). D–G, inhibition of carbonic anhydrase by methazolamide (10 μm, n = 8, D and E) or the chemically unrelated compound punicalagin (2 μm, n = 20, F and G) did not affect BAG neuron CO2 activation. *, p < 0.05. All stimuli were presented as 5-s pulses.

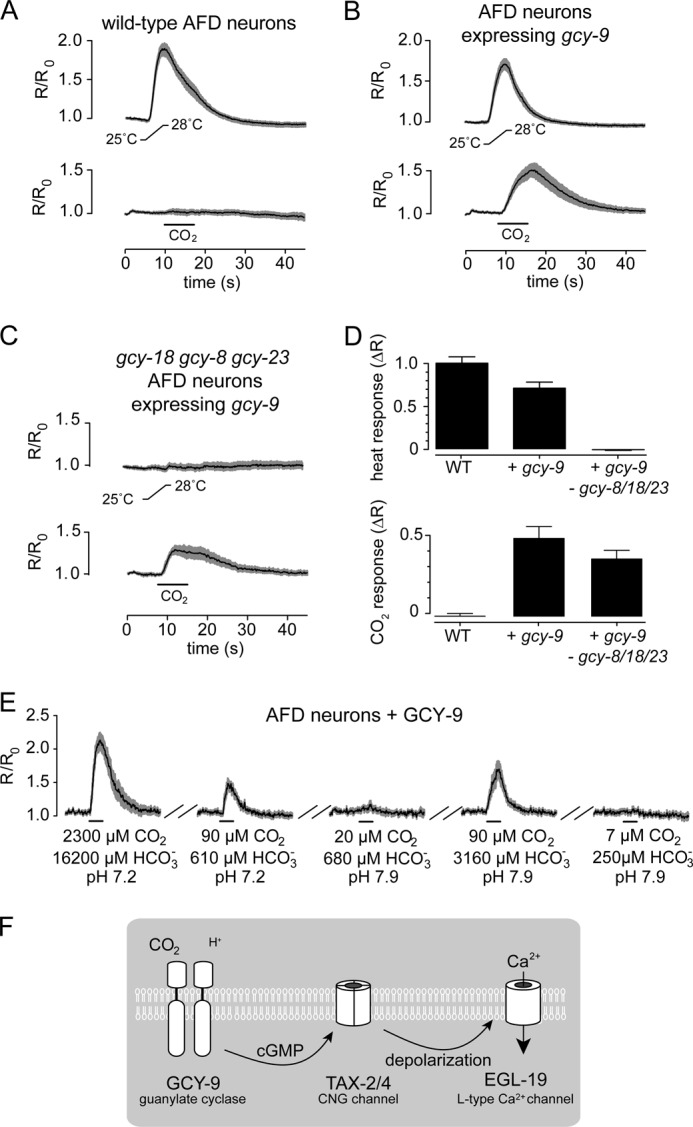

Previously, we showed that CNG channels and the receptor-type guanylate cyclase GCY-9 constitute the core of the CO2 sensory transduction apparatus in BAG neurons (24). Expression of GCY-9 is instructive for CO2 sensitivity and confers upon AFD neurons CO2 sensitivity that is independent of their ability to detect temperature stimuli (Fig. 7, A–D). To determine whether GCY-9 itself mediates detection of molecular CO2, we stimulated transgenic AFD neurons that express GCY-9 with bicarbonate solutions at neutral or alkaline pH. GCY-9-expressing AFD neurons, like BAG neurons, displayed calcium responses proportional to the concentration of CO2 (Fig. 7E). These data support a model in which GCY-9 functions as a receptor for molecular CO2 and show that GCY-9 detects CO2 independently of acid (Fig. 7F).

FIGURE 7.

The receptor-type guanylate cyclase GCY-9 mediates detection of molecular CO2. A–C, in vivo calcium responses to CO2 and thermal stimuli of wild-type AFD neurons (A), transgenic AFD neurons expressing GCY-9 (B), and transgenic AFD neurons mutant for three guanylate cyclases required for thermosensation and expressing GCY-9 (C). D, summary of peak amplitude responses to heat (upper panel) and CO2 (lower panel). Neuronal responses were recorded in situ. CO2 stimuli were 10% CO2. Heat ramps were from 25 to 28 °C. n ≥ 12 for each trace. E, in vitro responses of transgenic AFD neurons expressing GCY-9 to bicarbonate solutions as in Fig. 6A. F, a model of the transduction pathway by which BAG neurons detect CO2. CO2 and protons each activate GCY-9 to activate TAX-2/TAX-4 cGMP-gated channels, although the chemotransduction apparatus is more sensitive to CO2. Transduction currents are then amplified by activation of the L-type CaV EGL-19.

DISCUSSION

The remarkable tuning of C. elegans BAG neurons to molecular CO2 distinguishes them from previously characterized CO2 chemoreceptor neurons. CO2-responsive neurons have long been thought to principally detect either protons or bicarbonate produced by the hydration of CO2 (1, 2, 8). For example, in the vertebrate central nervous system, CO2-responsive neurons of the amygdala and respiratory centers display acid sensitivity, which in the case of amygdala neurons has been attributed to expression of the acid-sensing ion channel ASIC1a (16). Vertebrate gustatory neurons that are activated by CO2 are also thought to do so via protons generated by CO2 hydration. These neurons constitute a subset of acid-sensitive taste neurons and require an extracellular CAH for CO2 sensing (5). Likewise, a subset of mammalian olfactory sensory neurons also responds to CO2 in a CAH-dependent manner. These neurons, unlike CO2-responsive gustatory neurons, are proposed to principally detect bicarbonate (17, 18). Interestingly, CO2-responsive neurons of the vertebrate olfactory system express an isozyme of receptor-type guanylate cyclase D (GC-D), which might function as a receptor for bicarbonate (18, 38). That vertebrate GC-D neurons and C. elegans BAG neurons both use receptor-type guanylate cyclases that likely function as chemoreceptors might reflect divergence of an ancient mechanism for CO2 sensing based on cyclic nucleotide signaling.

There are instances of CO2 chemosensitivity that suggest that other chemotransduction systems might, like the GCY-9 system, detect molecular CO2. CO2-responsive neurons have been found in sensilla of the insect gustatory and olfactory systems. These sensilla are activated by CO2, not acid (3, 4), consistent with the hypothesis that their associated chemoreceptor neurons are tuned to detect molecular CO2. However, the neurons within these sensilla have only been studied in situ where it is not possible to control their extracellular environment. It is possible that the insensitivity of the chemosensory neurons in these sensilla to external acid results from a permeability barrier that prevents acid or bicarbonate from diffusing into the sensilla. If these neurons are tuned to detect molecular CO2, they will likely use receptor signaling mechanisms different from those used by C. elegans BAG neurons. Insect chemoreceptors are members of an insect-specific family of multipass transmembrane proteins. It is likely that the insect gustatory receptor that mediates CO2 sensitivity is a member of this family, and the receptor molecule that mediates olfactory detection of CO2 has already been identified as such (39). In the vertebrate brain there is evidence suggesting that molecular CO2 activates the connexin hemichannel Cx26 (40), which is expressed by astrocytes in areas of the medulla that respond to hypercapnia. ATP released at the ventral surface of the medulla in response to hypercapnia, as well as the changes in ventilation rate, are both diminished by inhibiting connexins (41). The effects of Cx26 mutation on the respiratory motor program remain to be determined, however, and in vivo genetic manipulations are needed to confirm a role for Cx26 as a CO2 sensor in the rodent nervous system.

Although BAG neurons are robustly activated by molecular CO2, we found that they can also be activated by acid. The receptor-type guanylate cyclase GCY-9 mediates sensitivity to both acid and molecular CO2, and our data suggest that GCY-9 is activated independently by either stimulus. Sensitivity of a receptor to multiple stimuli, including protons, has been described in other contexts, such as the cation channel TRPV1 in mammalian sensory neurons (42). Indeed, the acid sensitivity of a receptor signaling system that mediates CO2 sensing might match cellular responses to CO2 to the internal state of an organism. Acidosis is a hallmark of metabolic stress, during which pH homeostasis might be especially sensitive to perturbations caused by increased environmental CO2. The intrinsic acid sensitivity of BAG neurons might, for example, mediate enhanced CO2 avoidance behavior during periods of such stress. Another mechanism by which CO2 sensing might be regulated by the metabolic state of the animal is a functional connection between neurons that monitor internal oxygen concentration and the BAG neurons. CO2 avoidance behavior is modulated by hypoxia (22), and oxygen-sensing neurons functionally inhibit the CO2 avoidance behavior that is driven by BAG neurons (43).

Why are there so many distinct mechanisms for detecting CO2, not only with respect to cellular receptors, but also in terms of the chemical cue detected? Neurons tuned to detect molecular CO2 might play fundamentally different roles in animal physiology from cells that respond to CO2 metabolites. The principal products of CO2 metabolism, protons and bicarbonate, are substrates for a large number of redundant cellular systems that buffer and transport these ions. Only when the capacity of these buffers and transporters is exceeded will cells and tissues experience changes in pH or bicarbonate concentration. Neurons that detect protons and bicarbonate might therefore be considered tuned to the failure of pH and bicarbonate homeostasis and might mediate responses to these physiological stresses. By contrast, neurons that directly detect molecular CO2 would be able to detect changes in environmental or internal CO2 levels that would fail to significantly alter pH or bicarbonate levels. Mechanisms that detect molecular CO2 might therefore permit neural circuits that control host-finding behaviors and the respiratory motor program to detect low concentrations of CO2 that would otherwise be heavily buffered. In the context of respiratory control, such a mechanism would allow the respiratory motor program to respond to increased CO2 levels in the absence of acidosis. Indeed, some CO2-sensititive neurons implicated in respiratory control have been shown to respond to pH-neutral CO2 stimuli (13), suggesting that such a mechanism exists in vertebrates. It is an intriguing possibility that these neurons express a receptor for molecular CO2 that is analogous or homologous to GCY-9 and functions in central circuits to control respiratory rhythms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sonya Aziz-Zaman and Rouzbeh Mashayekhi for creating some plasmids used in this study and Mitchell Chesler and the Ringstad laboratory for many helpful comments and discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01-GM098320 (to N. R.). This work was also supported by XXXXXX.

- CAH

- carbonic anhydrase

- CaV

- voltage-gated calcium channel.

REFERENCES

- 1. Scott K. (2011) Out of thin air. Sensory detection of oxygen and carbon dioxide. Neuron 69, 194–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ma D. K., Ringstad N. (2012) The neurobiology of sensing respiratory gases for the control of animal behavior. Front. Biol. (Beijing) 7, 246–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Suh G. S., Wong A. M., Hergarden A. C., Wang J. W., Simon A. F., Benzer S., Axel R., Anderson D. J. (2004) A single population of olfactory sensory neurons mediates an innate avoidance behaviour in Drosophila. Nature 431, 854–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fischler W., Kong P., Marella S., Scott K. (2007) The detection of carbonation by the Drosophila gustatory system. Nature 448, 1054–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chandrashekar J., Yarmolinsky D., von Buchholtz L., Oka Y., Sly W., Ryba N. J., Zuker C. S. (2009) The taste of carbonation. Science 326, 443–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Richerson G. B. (2004) Serotonergic neurons as carbon dioxide sensors that maintain pH homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5, 449–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guyenet P. G., Stornetta R. L., Bayliss D. A. (2010) Central respiratory chemoreception. J. Comp. Neurol. 518, 3883–3906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sharabi K., Lecuona E., Helenius I. T., Beitel G. J., Sznajder J. I., Gruenbaum Y. (2009) Sensing, physiological effects and molecular response to elevated CO2 levels in eukaryotes. J. Cell Mol. Med. 13, 4304–4318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feldman J. L., Del Negro C. A., Gray P. A. (2013) Understanding the rhythm of breathing. So near, yet so far. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 75, 423–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dean J. B., Putnam R. W. (2010) The caudal solitary complex is a site of central CO2 chemoreception and integration of multiple systems that regulate expired CO2. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 173, 274–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Supuran C. T. (2010) Carbonic anhydrase inhibition/activation. Trip of a scientist around the world in the search of novel chemotypes and drug targets. Curr. Pharm. Des. 16, 3233–3245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Filosa J. A., Dean J. B., Putnam R. W. (2002) Role of intracellular and extracellular pH in the chemosensitive response of rat locus coeruleus neurones. J. Physiol. 541, 493–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang W., Bradley S. R., Richerson G. B. (2002) Quantification of the response of rat medullary raphe neurones to independent changes in pHo and PCO2. J. Physiol. 540, 951–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mulkey D. K., Stornetta R. L., Weston M. C., Simmons J. R., Parker A., Bayliss D. A., Guyenet P. G. (2004) Respiratory control by ventral surface chemoreceptor neurons in rats. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 1360–1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Williams R. H., Jensen L. T., Verkhratsky A., Fugger L., Burdakov D. (2007) Control of hypothalamic orexin neurons by acid and CO2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 10685–10690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ziemann A. E., Allen J. E., Dahdaleh N. S., Drebot I. I., Coryell M. W., Wunsch A. M., Lynch C. M., Faraci F. M., Howard M. A., 3rd, Welsh M. J., Wemmie J. A. (2009) The amygdala is a chemosensor that detects carbon dioxide and acidosis to elicit fear behavior. Cell 139, 1012–1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hu J., Zhong C., Ding C., Chi Q., Walz A., Mombaerts P., Matsunami H., Luo M. (2007) Detection of near-atmospheric concentrations of CO2 by an olfactory subsystem in the mouse. Science 317, 953–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sun L., Wang H., Hu J., Han J., Matsunami H., Luo M. (2009) Guanylyl cyclase-D in the olfactory CO2 neurons is activated by bicarbonate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 2041–2046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hallem E. A., Sternberg P. W. (2008) Acute carbon dioxide avoidance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 8038–8043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hallem E. A., Dillman A. R., Hong A. V., Zhang Y., Yano J. M., DeMarco S. F., Sternberg P. W. (2011) A sensory code for host seeking in parasitic nematodes. Curr. Biol. 21, 377–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hallem E. A., Spencer W. C., McWhirter R. D., Zeller G., Henz S. R., Rätsch G., Miller D. M., 3rd, Horvitz H. R., Sternberg P. W., Ringstad N. (2011) Receptor-type guanylate cyclase is required for carbon dioxide sensation by Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 254–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bretscher A. J., Busch K. E., de Bono M. (2008) A carbon dioxide avoidance behavior is integrated with responses to ambient oxygen and food in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 8044–8049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bretscher A. J., Kodama-Namba E., Busch K. E., Murphy R. J., Soltesz Z., Laurent P., de Bono M. (2011) Temperature, oxygen, and salt-sensing neurons in C. elegans are carbon dioxide sensors that control avoidance behavior. Neuron 69, 1099–1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brandt J. P., Aziz-Zaman S., Juozaityte V., Martinez-Velazquez L. A., Petersen J. G., Pocock R., Ringstad N. (2012) A single gene target of an ETS-family transcription factor determines neuronal CO2-chemosensitivity. PLoS One 7, e34014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ward S., Thomson N., White J. G., Brenner S. (1975) Electron microscopical reconstruction of the anterior sensory anatomy of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans? J. Comp. Neurol. 160, 313–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ware R. W., Clark D., Crossland K., Russell R. L. (1975) The nerve ring of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Sensory input and motor output. J. Comp. Neurol. 162, 71–110 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mello C. C., Kramer J. M., Stinchcomb D., Ambros V. (1991) Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans. Extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 10, 3959–3970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Christensen M., Estevez A., Yin X., Fox R., Morrison R., McDonnell M., Gleason C., Miller D. M., 3rd, Strange K. (2002) A primary culture system for functional analysis of C. elegans neurons and muscle cells. Neuron 33, 503–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bianchi L., Driscoll M. (2006) Culture of embryonic C. elegans cells for electrophysiological and pharmacological analyses. Wormbook (The C. elegans Research Community, ed) 10.1895/wormbook.1.122.1, www.wormbook.org [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30. Strange K., Christensen M., Morrison R. (2007) Primary culture of Caenorhabditis elegans developing embryo cells for electrophysiological, cell biological and molecular studies. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1003–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Frøkjaer-Jensen C., Kindt K. S., Kerr R. A., Suzuki H., Melnik-Martinez K., Gerstbreih B., Driscol M., Schafer W. R. (2006) Effects of voltage-gated calcium channel subunit genes on calcium influx in cultured C. elegans mechanosensory neurons. J. Neurobiol. 66, 1125–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rink T. J., Tsien R. Y., Pozzan T. (1982) Cytoplasmic pH and free Mg2+ in lymphocytes. J. Cell Biol. 95, 189–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huynh K. T., Baker D. W., Harris R., Church J., Brauner C. J. (2011) Effect of hypercapnia on intracellular pH regulation in a rainbow trout hepatoma cell line, RTH 149. J. Comp. Physiol. B 181, 883–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kwok T. C., Ricker N., Fraser R., Chan A. W., Burns A., Stanley E. F., McCourt P., Cutler S. R., Roy P. J. (2006) A small-molecule screen in C. elegans yields a new calcium channel antagonist. Nature 441, 91–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bargmann C. I. (1998) Neurobiology of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome. Science 282, 2028–2033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ringstad N., Horvitz H. R. (2008) FMRFamide neuropeptides and acetylcholine synergistically inhibit egg-laying by C. elegans. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 1168–1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Choi H. B., Gordon G. R., Zhou N., Tai C., Rungta R. L., Martinez J., Milner T. A., Ryu J. K., McLarnon J. G., Tresguerres M., Levin L. R., Buck J., MacVicar B. A. (2012) Metabolic communication between astrocytes and neurons via bicarbonate-responsive soluble adenylyl cyclase. Neuron 75, 1094–1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Guo D., Zhang J. J., Huang X.-Y. (2009) Stimulation of guanylyl cyclase-D by bicarbonate. Biochemistry 48, 4417–4422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jones W. D., Cayirlioglu P., Kadow I. G., Vosshall L. B. (2007) Two chemosensory receptors together mediate carbon dioxide detection in Drosophila. Nature 445, 86–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Huckstepp R. T., Eason R., Sachdev A., Dale N. (2010) CO2-dependent opening of connexin 26 and related β connexins. J. Physiol. 588, 3921–3931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Huckstepp R. T., id Bihi R., Eason R., Spyer K. M., Dicke N., Willecke K., Marina N., Gourine A. V., Dale N. (2010) Connexin hemichannel-mediated CO2-dependent release of ATP in the medulla oblongata contributes to central respiratory chemosensitivity. J. Physiol. 588, 3901–3920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Holzer P. (2009) Acid-sensitive ion channels and receptors. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 194, 283–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Carrillo M. A., Guillermin M. L., Rengarajan S., Okubo R. P., Hallem E. A. (2013) O2-sensing neurons control CO2 response in C. elegans. J. Neurosci. 33, 9675–9683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]