Background: The processing of DNA double strand breaks is critical for homologous recombination.

Results: The nonhomologous end joining factor DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) blocks end resection but is regulated by autophosphorylation, the Mre11-Rad5-Nbs1 (MRN) complex, and the ataxia telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) kinase.

Conclusion: DNA-PK regulates DNA end processing for homologous recombination.

Significance: Analyzing the effects of NHEJ factors on end processing is essential to our understanding of homologous recombination.

Keywords: DNA-binding Protein, DNA Damage Response, DNA Enzymes, DNA Recombination, DNA Repair, Protein Kinases

Abstract

The resection of DNA double strand breaks initiates homologous recombination (HR) and is critical for genomic stability. Using direct measurement of resection in human cells and reconstituted assays of resection with purified proteins in vitro, we show that DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), a classic nonhomologous end joining factor, antagonizes double strand break resection by blocking the recruitment of resection enzymes such as exonuclease 1 (Exo1). Autophosphorylation of DNA-PKcs promotes DNA-PKcs dissociation and consequently Exo1 binding. Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated kinase activity can compensate for DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation and promote resection under conditions where DNA-PKcs catalytic activity is inhibited. The Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN) complex further stimulates resection in the presence of Ku and DNA-PKcs by recruiting Exo1 and enhancing DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation, and it also inhibits DNA ligase IV/XRCC4-mediated end rejoining. This work suggests that, in addition to its key role in nonhomologous end joining, DNA-PKcs also acts in concert with MRN and ataxia telangiectasia-mutated to regulate resection and thus DNA repair pathway choice.

Introduction

DNA double strand breaks (DSBs)2 are caused by replication fork collapse, ionizing radiation, chemotherapeutic drugs, and reactive oxygen products of metabolism, and they can lead to chromosome rearrangements, genomic instability, and tumorigenesis if not repaired correctly (1). Eukaryotic cells have developed two major pathways to repair DSBs as follows: nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR). NHEJ is active throughout the cell cycle, whereas the activity of HR is limited to S and G2 phases (2). When NHEJ and HR are both active, 5′ to 3′ resection of DSBs is thought to be a critical control point for the choice between the two repair pathways, because the 3′ single strand DNA (ssDNA) generated by extensive resection serves to inhibit NHEJ but is required for Rad51 filament formation and strand invasion during HR (3, 4).

Many proteins have been implicated in the regulation of DSB resection in eukaryotic cells. The Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN) complex has been shown to promote resection by two independent endo/exonucleases, Exo1 and Dna2 (5–9). MRN recruits Exo1 to DSBs and promotes resection in conjunction with CtBP-interacting protein (CtIP) (10–15). The ataxia telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) protein kinase is activated via MRN and is also required for efficient DSB resection (16–18), although its role in this process is not completely understood.

The Ku70/80 heterodimer and DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) coordinate the process of NHEJ. After binding of Ku and subsequent recruitment of DNA-PKcs to DSBs, an active DNA-PK holoenzyme is formed that mediates the phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs itself as well as other NHEJ factors (19). Autophosphorylated DNA-PKcs undergoes a large conformational change that is thought to promote its dissociation from DNA ends (20–24). Of particular importance to this rearrangement, a cluster of six serines and threonines in DNA-PKcs termed the ABCDE cluster are autophosphorylated (25), and Thr-2609 and Thr-2647 in this cluster were also shown to be targets of ATM (26).

Apart from its role in NHEJ, DNA-PKcs has also been implicated in regulation of HR (24, 27–30), but the underlying mechanism is not fully understood. It has been shown that the expression of exogenous DNA-PKcs in cells lacking the enzyme inhibits HR in a Ku-dependent manner (28). However, there is still debate about how DNA-PK kinase activity affects DNA-PK regulation of HR, and conflicting results have been reported on this issue (28, 29, 31). It remains to be investigated whether DNA-PKcs directly affects resection and how its kinase activity functions in this process.

In this study, we examine how chemical inhibition of DNA-PKcs affects DSB resection using a resection assay for mammalian cells that we have recently developed.3 We find that DNA-PK inhibitor treatment strongly stimulates DSB resection, although the interpretation of this result is complicated by the inhibitor-induced loss of DNA-PKcs protein in human cells. To characterize the role of DNA-PKcs catalytic activity directly, we reconstitute resection with purified recombinant proteins in vitro and investigate the effect of DNA-PKcs on Exo1-mediated resection. The results show that DNA-PKcs inhibits Exo1 activity, which can be overcome by the combined effects of MRN and the autophosphorylation of DNA-PKcs. Phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs, either through autophosphorylation or phosphorylation by ATM, promotes the recruitment of Exo1 to DNA ends, suggesting that unphosphorylated DNA-PKcs presents a barrier to the recruitment of resection enzymes. Overall, we propose that in conjunction with MRN and ATM, DNA-PKcs directly regulates DSB resection and affects the DNA repair pathway choice.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

HEK293 cells expressing wild-type and 6A DNA-PKcs (T2609A/S2612A/T2620A/S2624A/T2638A/T2647A) (26) (provided by Dr. David Chen) and ER-AsiSI U2OS cells (provided by Dr. Gaëlle Legube) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen). 293-6E cells were provided by Dr. Yves Durocher and were grown in F17 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 4 mm l-Glutamine and 0.1% pluronic F-68 (Invitrogen).

Reagents and Antibodies

Protein kinase inhibitors used in this study were purchased from the following sources: DNA-PK inhibitor NU-7441 (Tocris Bioscience, 3712); DNA-PK inhibitor NU-7026 (Sigma, N1537); and ATM inhibitor KU-55933 (EMD Millipore, 80017-420). 4-Hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) was purchased from Sigma (catalog no. H7904). Antibodies for Western blotting were purchased from the following: PARP-1 (Genetex, GTX75098); Exo1 (Genetex, GTX109891); DNA-PKcs (Abcam, ab18); Thr(P)-2609 DNA-PKcs (GenWay, 18-785-210106); Ser(P)-2056 DNA-PKcs (Abcam, ab18192); ATM (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-135663), Ser(P)-1981 ATM (Abcam, ab81292), and Ser(P)-15 p53 (Calbiochem, PC461).

Western Blotting

Cells were lysed in Laemmli lysis buffer containing 10% glycerol, 2% (mass/volume) SDS, 64 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, boiled, and sonicated. Protein concentrations were measured using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce), mixed with 5× SDS loading buffer, and boiled for 5 min before separation by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to PVDF-FL membrane (Millipore) and probed with primary antibodies listed above, followed by detection with IRdye 800 anti-mouse (Rockland, RL-610-132-121) or Alexa Fluor 680 anti-rabbit (Invitrogen, A21076) secondary antibodies. Proteins on the membrane were detected using a Licor Odyssey scanner.

Genomic DNA Extraction

ER-AsiSI U2OS cells were mixed at 37 °C with 0.6% low gelling point agarose (BD Biosciences) in PBS (Invitrogen) at a density of 6 × 106 cells/ml. The solidified agar ball containing cells was generated by dropping 50 μl of cell suspension on a piece of Parafilm (Pechiney), transferred to a 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube, successively treated with 1 ml of ESP buffer (0.5 m EDTA, 2% N-lauroylsarcosine, 1 mg/ml proteinase-K, 1 mm CaCl2, pH 8.0) for 20 h at 16 °C with rotation and 1 ml of HS buffer (1.85 m NaCl, 0.15 m KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 2 mm EDTA, 4 mm Tris, 0.5% Triton X-100, pH 7.5) for 20 h at 16 °C with rotation, washed with 1 ml of phosphate buffer (8 mm Na2HPO4, 1.5 mm KH2PO4, 133 mm KCl, 0.8 mm MgCl2, pH 7.4) six times for 1 h at 4 °C with rotation, and melted by placing the tube in a 70 °C heat block for 10 min. The melted genomic DNA sample was diluted 15-fold at 70 °C with double distilled H2O, mixed with equal volume of 2× NEB restriction enzyme buffer 4 (from New England Biolabs), and stored at 4 °C for future use.

Measurement of Resection in Mammalian Cells

The level of resection adjacent to specific DSBs was measured by quantitative PCR (qPCR) with the sequences of TaqMan qPCR primers and probes available upon request. 20 μl of genomic DNA sample (∼140 ng in 1× NEB restriction enzyme buffer 4) was digested or mock-digested with 20 units of restriction enzymes (BsrGI, BamHI-HF, or HindIII-HF; New England Biolabs) at 37 °C overnight. 3 μl of digested or mock-digested samples (∼20 ng) were used as templates in 25 μl of qPCR containing 12.5 μl of 2× TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (ABI), 0.5 μm of each primer, and 0.2 μm probe using a ViiATM 7 Real Time PCR System (ABI). The percentage of ssDNA (ssDNA%) generated by resection at selected sites was determined as described previously (5). Briefly, for each sample, a ΔCt was calculated by subtracting the Ct value of the mock-digested sample from the Ct value of the digested sample. The percentage of ssDNA was calculated with the following: ssDNA% = 1/(2(ΔCt − 1) + 0.5)·100 (33).

Protein Expression and Purification

WT and 6A DNA-PKcs·Ku complexes were purified from DNA-PKcs WT- and 6A-HEK293 stable cell lines (26). Cells collected from 60 15-cm dishes were resuspended in 40 ml of cold lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 125 mm NaCl, 5% glycerol, 0.2% Nonidet P-40, 1.5 mm MgCl2) supplemented with protease inhibitor (Roche Applied Science) and phosphatase inhibitors (1 mm glycerol 2-phosphate disodium salt hydrate, 0.5 mm sodium pyrophosphate tetrabasic, and 1 mm sodium orthovanadate), homogenized, sonicated, and clarified by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. TAP-tagged WT and 6A DNA-PKcs were isolated from the supernatant using 1 ml of rabbit IgG-agarose beads (Sigma). The beads were washed twice with lysis buffer and twice with tobacco etch virus cleavage buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mm NaCl, 0.05 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT and 0.1% Nonidet P-40). DNA-PKcs protein was released from the beads in 1 ml of tobacco etch virus cleavage buffer by incubation with 500 units of tobacco etch virus protease (Invitrogen) at 16 °C for 8 h, followed by a series of batch purification through SP-Sepharose (GE Healthcare), ssDNA cellulose (Sigma), and Q-Sepharose Fast Flow resin (GE Healthcare). The protein was eluted with high salt buffer containing 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mm KCl, 10% glycerol, and 1 mm DTT and stored at −80 °C for future use.

Ku, Exo1, Exo1(D78A/D173A), MRN, and M(H129L/D130V)RN recombinant proteins were expressed and purified as described previously (34). ATM was expressed and purified from 293-6E cells (35). 25 μg of pTT5-FLAG-ATM vector (pTP2133) was transfected into 25 ml of 293-6E cells at a density of ∼1.7 × 106/ml using polyethyleneimine (Polysciences). Cells were harvested 72 h after transfection, and ATM protein was purified as described previously (36). The individual DNA-PKcs protein was purified from HeLa cells, as described previously (37), and was provided by Dr. Susan Lees-Miller. DNA ligase IV-XRCC4 complex was provided by Dr. Dale Ramsden and was purified as described previously (23).

In Vitro Resection Assay

The in vitro DNA resection assay was performed as described previously (5, 34). Briefly, the 4.4-kb pNO1 plasmid was linearized with SphI-HF (New England Biolabs) and incubated at 37 °C for 1 or 2 h in a 10-μl reaction containing 1 ng of DNA (37 pm), 25 mm MOPS, pH 7.0, 1 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ATP, 50 μg/ml BSA, 60 mm NaCl (the reactions in Figs. 2F and 3B contain 20 mm NaCl and 50 mm KCl), and proteins as indicated in the figure legends. The reaction was stopped by adding 1 μl of solution containing 1% SDS and 100 mm EDTA and further treated with 0.1 mg/ml proteinase K (Sigma) for 30 min at 37 °C to digest all proteins. Reaction products were separated by 0.7% native agarose gel and visualized directly by SYBR Green (Invitrogen) staining, followed by a nondenaturing Southern blot analysis using an RNA probe for a 1-kb region of the 3′ strand. To directly measure DNA resection by qPCR, the reaction was stopped by adding 1 μl of 0.05% SDS and further processed as described previously (5). To analyze the protein products of the resection assay, the reaction was stopped by adding 2.5 μl of 5× SDS loading buffer and boiled for 3 min. Proteins were separated by 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and visualized by silver staining and phosphorimaging (Fig. 5A, 0.25 mm ATP and 2.5 μCi [γ-32P]ATP (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) were used instead of 1 mm ATP in the reaction) or Western blotting.

FIGURE 2.

DNA-PKcs shows an inhibitory effect on DNA end resection by Exo1 in vitro. A, purified recombinant proteins used in this study. Exo1, Ku, DNA-PKcs, wild-type MRN (WT) and nuclease-deficient MRN (H129L/D130V), ATM, and DNA LigIV-XRCC4 were stained with Coomassie Blue after SDS-PAGE. The Ku-associated WT DNA-PKcs and Thr-2609 cluster phospho-blocking DNA-PKcs mutant (6A) were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining. Asterisk indicates Hsp70 that copurifies with ATM. B, schematic diagram of the resection assay in which a 4.4-kb linear plasmid DNA is incubated with Exo1 and other factors in the reaction, which leads to either no resection, short resection tracks, or medium to long resection tracks (shown with resection initiating from both DNA ends). The reaction products are visualized with SYBR Green (filled circle), which recognizes duplex DNA, or by nondenaturing Southern blot analysis using an RNA probe (line with asterisks) specific for a 1-kb region of the 3′ strand. C, reconstituted DSB resection assay was performed in the presence of 0.5 nm Exo1, 14 nm Ku, 7 nm DNA-PKcs, and 37 pm linear DNA at 37 °C for 1 h. Reaction products were separated by 0.7% native agarose gel and visualized as described in B by SYBR Green staining (top), followed by a nondenaturing Southern blot (bottom). D, DNA resection assays were performed as in C in the presence or absence of ATP. E, DNA resection assays were performed as in C but were stopped after 1 or 2 h as indicated. F, DNA resection assays were performed for 1 or 2 h with 0.35 nm wild-type (WT) DNA-PKcs or a Thr-2609 cluster site phospho-blocking DNA-PKcs mutant (6A) in the presence of 1.9 nm Ku, 0.1 nm Exo1, and 37 pm 4.4 kb linear DNA.

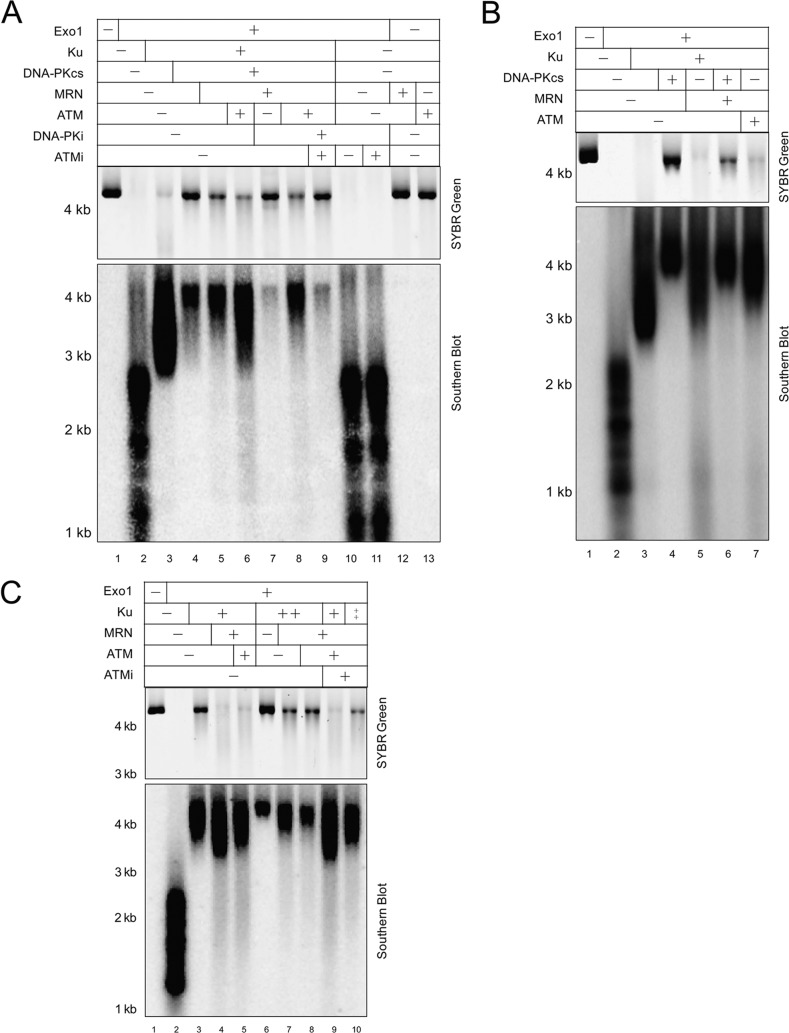

FIGURE 3.

MRN overcomes DNA-PKcs inhibition of Exo1-mediated resection. A, DNA resection assays were performed as in Fig. 2C in the presence of 0.5 nm Exo1, 14 nm Ku, 7 nm DNA-PKcs, 37 pm 4.4-kb linear DNA, but with MRN added as indicated (6, 12, or 24 nm). The 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity of Mre11 is not active under these reaction conditions (in the absence of manganese) (51). B, DNA resection assays were performed in the presence of 0.35 nm WT DNA-PKcs or a Thr-2609 cluster site phospho-blocking DNA-PKcs mutant (6A), 1.9 nm Ku, 0.1 nm Exo1, and 37 pm 4.4-kb linear DNA with or without 9.5 nm MRN complex for 1 h. C, DNA resection assays as in Fig. 3A were performed with 24 or 72 nm MRN or nuclease-deficient MRN mutant (M(H129L/D130V)RN) in the absence of ATP or in the presence of 200 μm DNA-PKi NU7026. D, part of the DNA products in C were digested or mock-digested with NciI at 37 °C overnight, and resection was measured by qPCR as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A representative experiment is shown. nt, nucleotide.

FIGURE 5.

ATM kinase activity compensates for DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation upon chemical inhibition of DNA-PKcs. A, resection assays were performed as in Fig. 4A in the presence of 0.5 nm Exo1, 14 nm Ku, 7 nm DNA-PKcs, 37 pm 4.4-kb linear DNA, 24 nm MRN, 0.1 nm ATM, 20 μm ATM-specific inhibitor KU-55933, 200 μm DNA-PK-specific inhibitor NU7026, and 2.5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP, except that the protein products were visualized by silver staining (top) and phosphorimaging (bottom). B, 14 nm Ku, 7 nm DNA-PKcs, 24 nm MRN, 0.1 nm ATM, and 1 ng of 4.4-kb linear DNA were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h in resection reaction buffer in the presence of 200 μm DNA-PKi NU7026. 50 nm GST-p53 substrate was also included in the reaction to monitor kinase activity. Western blotting analysis was performed using DNA-PKcs antibody, DNA-PKcs phospho-specific antibodies (Thr-2609 and Ser-2056), as well as p53 Ser(P)-15 antibody.

Combined Ligation and Resection Assay

The 4.4-kb linear pNO1 DNA (37 pm) was assayed with both DNA ligase IV/XRCC4 and Exo1 in a 10-μl reaction containing 25 mm MOPS, pH 7.0, 1 mm DTT, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ATP, 50 μg/ml BSA, 105 mm NaCl, 45 mm KCl, and 10% polyethylene glycol. Before adding ATP, MgCl2, LigIV-XRCC4, and Exo1, the mixture containing all other components was preincubated at 25 °C for 10 min. The reaction was allowed to proceed at 37 °C for 1 h and terminated by adding 1 μl of 0.05% SDS. Half of the reaction was diluted 5-fold with double distilled H2O. DNA end ligation mediated by LigIV/CRCC4 was measured by using a 1-μl sample as template in a 25-μl qPCR containing 12.5 μl of SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (ABI) and 0.5 μm of each primer (5′ primer, CTTGTTTCGGCGTGGGTATG, and 3′ primer, GAAGGAGCTGACTGGGTTGAAG). Another half of the reaction was diluted 10-fold with 1× NEB restriction buffer 4 and used to measure Exo1-mediated DNA resection as described previously (5).

DNA Binding Assay

A 717-bp DNA was generated by PCR with biotin on the 5′ strand at one end and three azide groups on the 5′ strand of the other end, as described previously (34), and conjugated to magnetic streptavidin beads (Invitrogen). The DNA binding assay was performed at 37 °C for 30 min as indicated in Fig. 7 in a 15-μl reaction containing 1.2 nm DNA, 25 mm MOPS, pH 7.0, 1 mm DTT, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ATP, 50 μg/ml BSA, and 60 mm NaCl. Interacting DNA and protein were cross-linked by exposing the reaction solution to UV light (254 nm) for 5 min. The bead-DNA-protein complex was then isolated with a magnetic holder, washed five times with washing buffer (25 mm MOPS, pH 7.0, 50 mm NaCl, 0.2% CHAPS, 2 mm DTT), and eluted in 1× SDS-PAGE loading buffer with boiling for 5 min. The samples were then subjected to Western blotting analysis using Exo1 and DNA-PKcs antibodies.

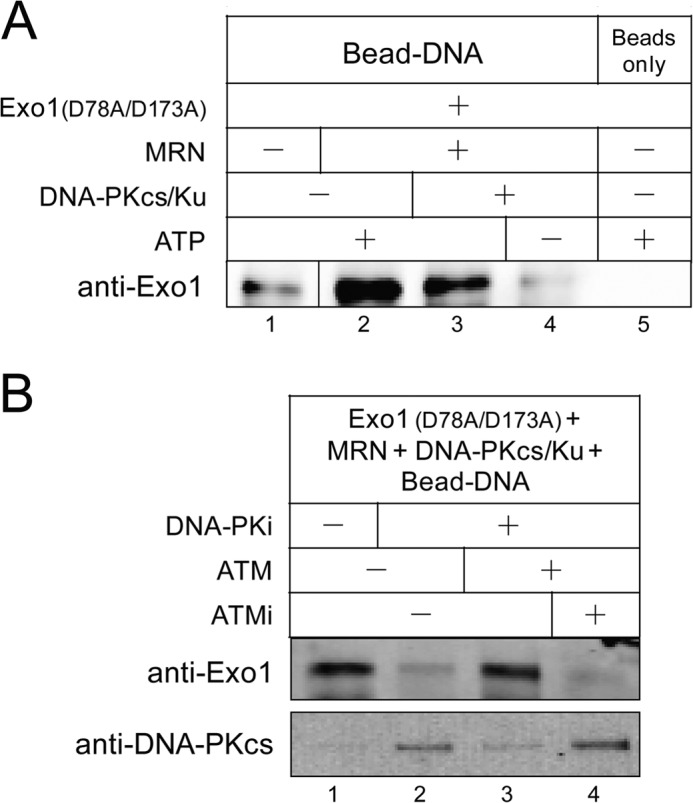

FIGURE 7.

Opposing effects of DNA-PKcs and MRN regulate DNA ligase IV-mediated end ligation and Exo1-mediated resection. A, 37 pm 4.4-kb SphI-linearized DNA was assayed in the presence of 0.5 nm Exo1, 0.5 nm DNA ligase IV-XRCC4 complex, 2.5 nm Ku, 5 nm DNA-PKcs, and 24 nm MRN. DNA ligation and resection were both measured by qPCR as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Ligation level in the presence of LigIV-XRCC1 alone was set to 1. A representative experiment is shown. B, combined DNA ligation and resection assays were performed as in A in the presence or absence of 200 μm DNA-PKi NU7026. C, DNA ligation assay was performed as in A with 4 or 100 nm wild-type MRN or nuclease-deficient MRN complex (M(H129L/D130V)RN). nt, nucleotide.

RESULTS

Chemical Inhibition of DNA-PK Stimulates DSB Resection in Human Cells

We have established a qPCR assay for accurate measurement of DSB resection in human cells using a U2OS cell line (ER-AsiSI U2OS) that expresses the restriction enzyme AsiSI fused to the ER hormone-binding domain (38). Approximately 150 DSBs can be induced at sequence-specific sites after treating the cells with 4-OHT, which induces translocation of the ER-AsiSI protein into the nucleus (39). To accurately measure ssDNA generated by resection adjacent to specific AsiSI-induced DSBs, we focused on two AsiSI sites on chromosome 1 (“DSB1,” chromosome 1, 89231183; “DSB2,” chromosome 1, 109838221) (38) and designed three pairs of qPCR primers across BsrGI (DSB1) or BamHI (DSB2) restriction sites located various distances from each AsiSI site (DSB1, 335, 1618, and 3500 bp; DSB2, 364, 1754, and 3564 bp) (Fig. 1A). The restriction enzymes can be used to distinguish between ssDNA generated by resection and unresected dsDNA because they can only cut duplex DNA. As a negative control, we designed a pair of primers at a site where there is no nearby AsiSI sequence on chromosome 22 (“No DSB”) (40). After extracting the genomic DNA, the percentage of ssDNA (ssDNA%) at various sites adjacent to DSB1 and DSB2 was measured by qPCR (5), and the percentage of double strand breaks (DSB%) present at the two AsiSI sites was also examined using two pairs of primers across the AsiSI sites.

FIGURE 1.

Chemical inhibition of DNA-PK stimulates DSB resection in human cells. A, schematic diagram of TaqMan qPCR primer design and in vivo resection assay. Primers for measurement of ssDNA generated by resection at various sites adjacent to the AsiSI-induced DSB1 are indicated by arrows. The primers are designed across restriction sites (here shown as BsrGI) located varying distances from the AsiSI site. Primer design for resection measurement at “DSB2” and No DSB is similar, except that the primer pairs for DSB2 are across BamHI sites, and the primer pair for No DSB is across a HindIII restriction site. Each genomic DNA sample from cells treated or mock-treated with 4-OHT was digested or mock-digested with restriction enzyme (BsrGI, BamHI-HF, or HindIII-HF), followed by qPCR analysis using corresponding set(s) of primers and probes. For each sample, a ΔCt was calculated by subtracting the Ct value of the mock-digested sample from the Ct value of the digested sample, and the percentage of resected DNA was calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, ER-AsiSI U2OS cells were pretreated with 10 μm ATMi KU-55933 or 10 μm DNA-PK inhibitor NU-7441 (DNA-PKi) for 1 h, followed by induction or mock induction of DSBs with 300 nm 4-OHT for 4 h and measurement of DNA resection. C, percentages of DSBs at the two selected AsiSI sites were measured by qPCR using undigested gDNA samples from B and two sets of primers across the two AsiSI sites. The No DSB primers were used to normalize the amount of gDNA in the qPCR. DSB percentages at DSB1 and DSB2 sites in mock-induced cells were both set to zero. D, ER-AsiSI U2OS cells were pretreated with 10 μm ATMi KU-55933, 10 μm DNA-PK inhibitor NU-7441, or 20 μm DNA-PK inhibitor NU-7026 as indicated for 1 h, followed by induction of DSBs with 300 nm 4-OHT for 4 h. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot using antibodies against DNA-PKcs, phospho-DNA-PKcs Ser-2056, ATM, and phospho-ATM Ser-1981, with PARP-1 as a loading control. E, quantitation of DNA-PKcs band in D; average of three quantitations is shown with standard deviation. F, ER-AsiSI U2OS cells were treated as in D, and DNA resection was measured. Error bars show standard deviation (n = 3 or 4). nt, nucleotide.

DNA-PKcs is an important classical NHEJ factor but may also be involved in regulation of HR (24, 28). Our previous study measuring resection in human cells showed that depletion of DNA-PKcs significantly increased resection.3 This is expected considering the widely accepted model, where NHEJ and HR factors compete for DNA ends (28, 29, 42), but it remains unclear how the kinase activity and phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs affects DSB resection. Several studies have shown that phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs promotes release of DNA-PKcs from DNA and that blocking DNA-PKcs phosphorylation using small molecule inhibitors or mutations in the phosphorylation sites results in reduced rates of DSB repair and reduced survival after ionizing radiation (20, 22, 43). At least a subset of the effects of blocked autophosphorylation occurs through inhibition of NHEJ, because loss of catalytic activity has been shown to impede the ligation step of joining (23, 44). However, the effect of chemical inhibition of DNA-PK on HR remains controversial (28, 29, 31). We examined this by performing the DNA resection assay in the presence of a DNA-PK inhibitor NU-7441 (DNA-PKi) or vehicle (DMSO). For comparison, cells were also treated with the ATM inhibitor KU-55933 (ATMi). As expected, inhibition of ATM kinase activity led to decreased resection at various sites adjacent to DSB1 and DSB2 (Fig. 1B), indicating that ATM promotes resection in human cells. In contrast, inhibition of DNA-PK catalytic activity strongly stimulated DSB resection (Fig. 1B). Strikingly, the accumulation of DSBs at both DSB1 and DSB2 sites was not affected by ATMi but was dramatically increased by DNA-PKi (Fig. 1C), probably due to DNA-PKi inhibition of NHEJ-mediated repair. DNA-PKi treatment thus provides more DSB ends for resection, at least in part explaining why inhibition of DNA-PK kinase activity appears to promote this process.

We also examined whether the protein level of DNA-PKcs was affected by DNA-PK inhibitor upon DNA damage, because some inhibitors have been implicated in the degradation of their target proteins (45). We found that NU-7441 treatment indeed led to a decrease of DNA-PKcs protein levels by ∼40%, and another widely used DNA-PK inhibitor, NU-7026, had the same effect (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, treating the cells with both DNA-PK inhibitor and ATM inhibitor further decreased the protein level of DNA-PKcs, and ATM protein levels also were reduced upon decrease of DNA-PKcs (Fig. 1, D and E), consistent with the reported effect of DNA-PKcs depletion on ATM expression (46). In the absence of ATM inhibitor, both NU-7441 and NU-7026 dramatically increased DNA resection, whereas the ATM inhibitor significantly attenuated this effect (Fig. 1F), even though the level of DNA-PKcs protein was further reduced (Fig. 1, D and E). Taken together, these data suggest that chemical inhibition of DNA-PKcs may stimulate DSB resection in human cells via a least two mechanisms as follows: 1) DNA-PK inhibition reduces NHEJ repair and provides more DSB ends for resection; 2) DNA-PK inhibition decreases DNA-PKcs protein levels, which enhances resection. However, the loss of DNA-PKcs protein and inhibition of NHEJ repair with inhibitor treatment complicates the interpretation of the effect of DNA-PKcs kinase activity on end processing rates.

DNA-PKcs Inhibits DNA End Resection by Exo1 in Vitro

Our study of resection in human cells showed that loss of DNA-PKcs protein stimulates DNA resection, but was inconclusive with respect to the role of DNA-PKcs kinase activity. It is also not clear whether DNA-PKcs indirectly regulates DSB resection by promoting NHEJ repair and limiting the availability of DSB ends for resection or whether it can also directly affect the activity of DNA resection enzymes. In addition, it remains to be investigated how the kinase-inactive DNA-PKcs is released from DSB ends in the presence of the DNA-PK inhibitor (28).

To answer these questions, we performed reconstituted resection assays in vitro with purified human Exo1, Ku70/80 heterodimer, DNA-PKcs, and other proteins involved in DNA damage sensing and repair (Fig. 2A). We tested the activity of Exo1 in the presence of Ku or DNA-PKcs on a 4.4-kb linearized plasmid DNA and visualized the reaction products by SYBR Green staining and by nondenaturing Southern blot, probing for a 1-kb region of the 3′ strand at one end of the linearized plasmid DNA (Fig. 2, B and C). Exo1 alone completely degraded the DNA substrate, although Ku reduced the percentage of resected DNA molecules and the extent of resection by Exo1 (Fig. 2C). DNA-PKcs by itself showed little effect on the activity of Exo1 (Fig. 2C, lane 4); however, resection was strongly inhibited in the presence of both Ku and DNA-PKcs (Fig. 2D), showing that the effect of Ku and DNA-PKcs on resection is cooperative. Remarkably, the resection was completely blocked when ATP was eliminated from the reaction (Fig. 2D, lane 5), suggesting that phosphorylation events mediated by DNA-PK promote resection, even though the presence of the kinase per se is inhibitory.

DNA-PKcs Autophosphorylation Overcomes DNA-PKcs Inhibition of Resection

To further characterize the effect of DNA-PKcs on resection, we performed a time course experiment in the presence or absence of ATP. A 1-h reaction was sufficient for Exo1 to completely degrade the DNA substrate (Fig. 2E, compare lanes 2 and 3), and ATP was not required for Exo1 to fulfill its function (Fig. 2E, lane 4), which was also the case in the presence of Ku (Fig. 2E, lanes 5–7). However, with both Ku and DNA-PKcs in the assay, a 2-h reaction led to 2.8-fold higher levels of resection than the 1-h reaction based on Southern blot signal (Fig. 2E, compare lanes 8 and 9), suggesting the inhibition of Exo1 by DNA-PKcs is a reversible process in the presence of ATP. DNA-PKcs was previously shown to release from DNA ends upon autophosphorylation in the central domain of the kinase (20), suggesting that DNA-PKcs inhibition of resection is released as more DNA-PKcs molecules are autophosphorylated in a longer reaction. Without ATP, even a 2-h reaction results in no resection (Fig. 2E, lane 10), further confirming that autophosphorylation of DNA-PKcs is critical for resection in the presence of Ku and DNA-PKcs.

Autophosphorylation of DNA-PKcs at the ABCDE cluster has been suggested to be functionally important for DNA end processing, both in NHEJ and in HR (22–24). To examine if this phosphorylation event affects Exo1-mediated DNA resection, we purified a DNA-PKcs·Ku complex where all six sites in the DNA-PKcs ABCDE cluster had been mutated (6A), and we tested it in a time course experiment in comparison with a wild-type DNA-PKcs·Ku complex (WT). In a 1-h reaction, the 6A complex showed slightly more inhibition of Exo1 activity than WT (Fig. 2F, compare lanes 1 and 4). However, in a 2-h reaction, 3.5-fold higher levels of resection products were generated by Exo1 with WT DNA-PKcs compared with the 6A mutant, as measured by the intensity of Southern blot signal (Fig. 2F). These data suggest that autophosphorylation of the ABCDE cluster sites decreases DNA-PKcs inhibition of Exo1-mediated resection, presumably by promoting the release of DNA-PKcs from DNA ends and allowing Exo1 recruitment. Of note, ATP still promoted resection in the presence of 6A DNA-PKcs although always to a lesser extent than WT DNA-PKcs, consistent with reports that autophosphorylation of DNA-PKcs at sites other than the ABCDE cluster sites can also promote DNA-PKcs release (22, 23). Taken together, these data suggest that autophosphorylation of DNA-PKcs at the ABCDE cluster sites and other sites can actively release the inhibition of Exo1-mediated resection.

MRN Overcomes DNA-PKcs Inhibition of Exo1 Activity

MR and Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1(Xrs2) complexes have been implicated in DSB resection in vivo and in extracts (8, 9, 47). In vitro studies with purified proteins have also shown that MR and MRN(X) complexes recruit long range exo/endonucleases and also help to block the inhibitory effects of Ku (5, 6, 34, 48, 49). Here, we found that MRN strongly promotes DNA resection by Exo1 in the presence of both Ku and DNA-PKcs in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). MRN was also able to stimulate resection with 6A DNA-PKcs, but the 6A DNA-PKcs still showed more inhibition of Exo1 activity than wild-type DNA-PKcs in the presence of MRN (Fig. 3B). A nuclease-deficient MRN mutant (M(H129L/D130V)RN) (50) exhibited similar stimulation of Exo1 activity as wild-type MRN (Fig. 3C), which was confirmed by qPCR, measuring the percentage of ssDNA at 29 and 1025 nucleotides from the DNA end (Fig. 3D) (5, 34). These data suggest that the nuclease activity of MRN is not essential for stimulation of Exo1 in the presence of Ku and DNA-PKcs. In addition, the 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity of Mre11 is not active under these reaction conditions (in the absence of manganese) (51). In contrast to the stimulatory effect of MRN on resection in the presence of 6A DNA-PKcs, MRN could not overcome DNA-PKcs inhibition of resection in the absence of ATP or in the presence of the DNA-PK inhibitor NU-7026 (DNA-PKi) (Fig. 3C). Thus, in the presence of DNA-PKcs, MRN can promote resection only when DNA-PKcs can be phosphorylated and released from DNA ends.

ATM Promotes Exo1-mediated Resection in the Presence of Ku and DNA-PKcs by Phosphorylating DNA-PKcs

The fact that ATM kinase activity potentiates the stimulatory effect of DNA-PK inhibitor on DNA resection in cells (Fig. 1F) suggested there might be an important role for ATM in regulating DNA-PKcs inhibition of resection. At least two of the phosphorylation sites in the ABCDE cluster, Thr-2609 and Thr-2647, have been identified as ATM target sites in human cells (26), and ATM activity has been shown to be required for resection of DBSs in Xenopus extracts (16) and for a subset of HR in human cells (52). Here, we found that ATM could further alleviate DNA-PKcs inhibition of resection in the presence of MRN (Fig. 4A, lane 6). To further examine whether ATM-mediated phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs affects resection, we performed in vitro resection assays in the presence or absence of the DNA-PK-specific inhibitor NU7026 (DNA-PKi). The result again clearly shows that blocking the kinase activity of DNA-PKcs dramatically inhibits DSB resection in the presence of MRN (Fig. 4A, lane 7). In contrast, eliminating DNA-PKcs protein from a resection reaction dramatically increases DSB resection (Fig. 4B, compare lane 5 with 4), similar to our observations in human cells.3 Interestingly, the addition of ATM largely restores resection in the presence of DNA-PK inhibitor, and this rescued resection was inhibited again when the ATM inhibitor was present (Fig. 4A, lanes 8 and 9). With Ku alone, ATM did not further promote resection in the presence of MRN; rather, it showed slight inhibitory effect on resection (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 5 and 7), possibly due to the reported inhibitory effect of ATM phosphorylation on Exo1 Ser-714 (53). To confirm this, we performed a titration of Ku and observed similar inhibition of Exo1 activity by ATM (Fig. 4C, lanes 5 and 8), where this inhibitory effect could be overcome by inhibition of ATM kinase activity (Fig. 4C, compare lanes 5 with 9 and lanes 8 with 10). These data suggest that ATM stimulation of resection in the presence of both Ku and DNA-PKcs is specific to DNA-PKcs and might be achieved by phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation sites, as suggested previously (26).

FIGURE 4.

ATM promotes Exo1-mediated resection in the presence of Ku and DNA-PKcs. A, DNA resection assays were performed as in Fig. 2C in the presence of 0.5 nm Exo1, 14 nm Ku, 7 nm DNA-PKcs, 37 pm 4.4-kb linear DNA, 24 nm MRN, 0.1 nm ATM, 20 μm ATM-specific inhibitor KU-55933, and 200 μm DNA-PK-specific inhibitor NU7026. Reaction products were visualized by SYBR Green staining (top) and Southern blot analysis (bottom). B, DNA resection assays were performed as in A using indicated proteins. C, DNA resection assays were performed as in A with 0.5 nm Exo1, 56 nm (+), or 112 nm (++) Ku, 24 nm MRN, and 0.1 nm ATM in the presence or absence of 20 μm ATM-specific inhibitor KU-55933.

To test this hypothesis, we monitored the phosphorylation status of DNA-PKcs by using [γ-32P]ATP in the reaction (Fig. 5A). DNA-PKcs showed a faint autophosphorylation band when incubated in the presence of Ku (Fig. 5A, lane 4). Remarkably, MRN promotes DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation (Fig. 5A, lane 5), which might promote DNA-PKcs dissociation and contribute to the stimulatory effect of MRN on Exo1 activity in the presence of DNA-PKcs. As expected, addition of ATM further increased the level of DNA-PKcs phosphorylation (Fig. 5A, lane 6). The phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs in the presence of MRN was blocked by DNA-PK inhibitor (Fig. 5A, lane 7), confirming this as autophosphorylation. Addition of ATM to this reaction restored DNA-PKcs phosphorylation, which in this case was blocked by the ATM inhibitor (Fig. 5A, lanes 8 and 9), confirming that ATM indeed phosphorylates DNA-PKcs. In addition, use of phospho-specific antibodies showed that both Thr-2609 and Ser-2056 of DNA-PKcs could be phosphorylated by ATM when autophosphorylation of DNA-PKcs is suppressed by the DNA-PK inhibitor in vitro (Fig. 5B). In the presence of DNA-PKcs, the level of Exo1-mediated resection correlates well with the phosphorylation level of DNA-PKcs (Figs. 4A and 5A). These data suggest that ATM can promote resection by increasing the phosphorylation level of DNA-PKcs, which could be a novel mechanism by which ATM promotes HR. In addition, ATM kinase activity can compensate for DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation and restore resection upon inhibition of DNA-PKcs.

DNA-PKcs Inhibits the Recruitment of Exo1 to DNA Ends in Vitro

In accordance with our findings with Exo1, previous studies also showed that DNA-PK inhibited the digestion of DNA by exonuclease V and that autophosphorylation of DNA-PKcs overcame this inhibition (23, 54). It is possible that DNA-PKcs inhibits Exo1-mediated resection in the presence of Ku simply by blocking DNA ends and preventing Exo1 binding. To test this hypothesis, we performed a DNA pulldown assay using a 717-bp biotinylated DNA substrate that was conjugated to magnetic streptavidin beads as described previously (34). A nuclease-deficient Exo1 mutant (Exo1(D78A/D173A)) was used for this experiment to prevent degradation of the DNA by Exo1. The DNA-protein complex was cross-linked with UV light and isolated for Western blotting analysis using Exo1 antibody. Exo1 alone showed low affinity for DNA ends (Fig. 6A, lane 1). Our previous work showed that MRX was able to promote the recruitment of yeast Exo1 to DNA ends (5). Similarly, we found that MRN greatly improves the binding of human Exo1 to the DNA substrate (Fig. 6A, lane 2). Exo1 recruitment was significantly reduced in the presence of Ku and DNA-PKcs and was almost completely blocked when ATP was not included in the reaction (Fig. 6A, lanes 3 and 4). Similar to DNA-PKcs phosphorylation, Exo1 recruitment was inhibited by DNA-PK inhibitor and restored by ATM kinase activity (Fig. 6B), suggesting that ATM acts to remove the kinase-inactive DNA-PK complex from DSBs. In this experiment, we also monitored binding of DNA-PKcs to the DNA and confirmed that inhibition of DNA-PKcs activity stabilizes the kinase on DNA, whereas ATM catalytic activity helps to remove DNA-PKcs (Fig. 6B). Taken together, these data suggest that DNA-PKcs inhibits Exo1-mediated resection by blocking DNA ends and that autophosphorylation or ATM-mediated phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs overcomes this inhibitory effect by promoting DNA-PKcs dissociation and Exo1 recruitment.

FIGURE 6.

Blocking the activity of DNA-PKcs inhibits the recruitment of Exo1 to DNA ends and promotes stabilization of DNA-PKcs. A, DNA binding assay was performed with 110 nm nuclease-deficient Exo1(D78A/D173A), 24 nm MRN, 28 nm Ku, 14 nm DNA-PKcs, and 1.2 nm of a 717-bp biotinylated DNA substrate (containing three azide cross-linker groups on the 5′ strand) conjugated to magnetic streptavidin beads. The Dynabead-DNA-protein complex was cross-linked with UV light, washed, and pulled down for Western blotting analysis using Exo1 antibody. B, DNA binding assay as in A was performed in the presence of 110 nm Exo1 (D78A/D173A), 2.5 nm ATM, 20 μm ATM specific inhibitor KU-55933, and 200 μm DNA-PK specific inhibitor NU7026 and probed for both Exo1 and DNA-PKcs.

Opposing Effects of DNA-PKcs and MRN Regulate DNA Ligase IV-mediated End Ligation and Exo1-mediated Resection

Previous studies showed that DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation promotes DNA end joining by the DNA ligase IV-XRCC4 complex (LigIV-XRCC4) (23). Here, we examined how DNA-PKcs and MRN regulate NHEJ and resection with both LigIV-XRCC4 and Exo1 in the same reaction. We measured ligation of the cohesive ends of the linearized plasmid substrate by qPCR using a pair of primers across the restriction site, and we simultaneously measured resection as described previously (5, 34). As expected, when LigIV-XRCC4 or Exo1 were present individually, DNA ligation was stimulated by Ku and DNA-PKcs, whereas resection was inhibited by Ku and DNA-PKcs (Fig. 7, A and B). However, with both LigIV-XRCC4 and Exo1 in the assay, ligation was largely blocked (Fig. 7, A and B), possibly because the DNA ends were quickly resected by Exo1 and became poor substrates for ligation in the in vitro assay. In vivo the presence of other NHEJ factors and other regulators of HR likely are responsible for the high efficiency of NHEJ (21, 42). In the presence of the DNA-PK inhibitor, both ligation and resection were blocked (Fig. 7B, lanes 3 and 6), further indicating that autophosphorylation of DNA-PKcs is important for both NHEJ and HR. Unexpectedly, although MRN overcomes DNA-PKcs inhibition of resection (Fig. 7A, lane 9), it strongly inhibits DNA ligation in the presence of Ku/DNA-PKcs (Fig. 7A, lane 5). This inhibition does not require the nuclease activity of MRN (Fig. 7C), suggesting that the inhibitory effect is not simply due to short range processing of DNA ends by MRN.

DISCUSSION

DNA-PKcs has been shown to possess dual functions in the regulation of both NHEJ and HR (24, 27–30), but the mechanism by which HR is regulated by DNA-PKcs is not well understood. Our previous study using the cellular resection assay clearly showed that loss of DNA-PKcs leads to increased DSB resection,3 consistent with the observation that complementation of DNA-PKcs in V3 DNA-PKcs null CHO cells decreases Rad51 foci formation upon DNA damage (24). We also observed increased accumulation of DSBs in DNA-PKcs-deficient cells compared with wild-type cells,3 likely due to a failure of NHEJ, and thus more DSB ends are available for resection in the absence of DNA-PKcs. Here, we investigated the effects of small molecule inhibition of DNA-PKcs and found that this also simulates resection in cells. However, interpretation of these results is complicated by an inhibitor-dependent reduction of DNA-PKcs protein by as much as 40% (Fig. 1, D and E), in effect depleting DNA-PKcs by another means. In addition, loss of DNA-PKcs also leads to loss of ATM (Fig. 1D) (46).

In contrast, our in vitro reconstituted resection assay clearly shows that a catalytically inactive DNA-PK complex generates a strong barrier to resection, such that it cannot be relieved by MRN (Fig. 3C). The end result of blocking DNA-PKcs activity is an inability to load Exo1 on DSB ends, consistent with the idea that autophosphorylation of DNA-PKcs helps to release it from ends and to allow access of other repair factors (21, 55). In cells, the effects of DNA-PKcs inhibitors on DNA-PKcs protein levels and NHEJ efficiency, as well as the phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs by ATM, likely mask the stimulatory effects of DNA-PKcs catalytic activity on resection and yield conflicting observations (28, 29, 31, 56). Our results in vitro are consistent with previous observations that loss of DNA-PKcs catalytic activity (through truncation of the catalytic domain, chemical inhibition, or mutation of autophosphorylation sites) actually inhibits HR (29, 30).

Other reports have shown that ATM actively regulates HR (16, 57), and we also observe here that inhibition of ATM leads to a lower rate of resection (Fig. 1B). Phosphorylation of resection-related factors likely account for this; for instance, ATM-mediated phosphorylation of CtIP is critical for CtIP stimulation of resection (19, 58). The stabilization of the SOSS1 single-stranded DNA binding complex by ATM-mediated phosphorylation of hSSB1 (59) serves as another mechanism by which ATM promotes resection, because SOSS1 has been shown to promote resection both in vitro (34) and in human cells.3 It has also been reported that ATM also phosphorylates DNA-PKcs (26), which we show here in vitro promotes DSB resection and rescues Exo1 resection activity when DNA-PKcs catalytic activity is inhibited (Fig. 4A). ATM phosphorylates the Thr-2609 cluster of DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation sites in cells expressing wild-type and kinase-deficient alleles of DNA-PKcs (26), indicating that these sites are bona fide ATM target sites. Unlike the loss of DNA-PKcs protein, blocking DNA-PKcs catalytic activity clearly is inhibitory to DSB resection, but this block can be removed by ATM-mediated phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs. Similar cross-talk between DNA-PKcs and ATM has been observed in V(D)J recombination. A recent study in mouse pre-B cells showed that coding joint formation during V(D)J recombination was blocked by loss of DNA-PKcs protein, although it was not affected by inhibition of DNA-PKcs kinase activity when active ATM is present (60).

We also find that MRN stimulates DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation (Fig. 5A), possibly mediated by the end tethering activity of MRN (32), which in turn might promote DNA-PKcs kinase activity. The DNA ends tethered together by MRN are likely to be good substrates for DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation in trans, which facilitates end processing (25).

We observed in this study that MRN partially alleviates the inhibition of Exo1-mediated resection, similar to our previous observations with yeast MRX, yeast Ku, and yeast Exo1 (5). With the human proteins in the presence of DNA-PKcs, we observed an even stronger block to resection imposed by Ku and a complete block in the absence of ATP. The primary effect of MRN on this reaction is to increase the number of ends accessed by Exo1, consistent with our hypothesis that the role of MRN is to stimulate the initiation of resection by Exo1. However, Ku also appears to reduce the extent of Exo1 resection, which is partially suppressed by MRN. It is possible that Ku accumulates internally on the DNA and in this way restrains the progression of Exo1, but further experiments are required to test this idea.

Our experiments measuring ligation and resection in the same reaction showed that MRN blocks end joining mediated by DNA ligase IV-XRCC4 (Fig. 7, A and C). This result is unexpected because MRX promotes Ku-mediated end joining in budding yeast (41), and a previous study showed that MRN strongly stimulates DNA ligation by DNA ligase III-XRCC1 by mediating DNA end tethering in vitro (50). It is possible that human MRN-mediated end synapsis promotes the activity of ligase III-XRCC1 but does not provide a configuration of ends that is favorable for the ligase IV-XRCC4 complex. In addition, this synapsis might also promote the in trans autophosphorylation of DNA-PKcs (Fig. 5A), which may lead to premature dissociation of DNA-PKcs and inhibit end rejoining. Moreover, MRN may interfere with the formation of DNA-PKcs-mediated intermolecular DNA end synapsis, which contributes to DNA ligation (54).

In summary, using both in vivo resection assays and in vitro reconstituted reactions, we have demonstrated that the NHEJ factor DNA-PKcs has the ability to actively regulate HR via at least two mechanisms. 1) DNA-PKcs indirectly affects DSB resection by promoting NHEJ repair, which decreases the amount of DSBs available for resection. 2) DNA-PKcs directly inhibits DSB resection by actively blocking DSB ends. Both autophosphorylation and ATM-mediated phosphorylation of DNA-PKcs can overcome DNA-PKcs inhibition of resection by enhancing DNA-PKcs dissociation and Exo1 recruitment. The MRN complex promotes resection in the presence of Ku/DNA-PKcs by recruiting Exo1 and enhancing DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation, but it inhibits end rejoining that is stimulated by Ku and DNA-PKcs. It is important to note that the in vitro reactions shown here are a reconstitution of the enzymatic reactions that are thought to occur in vivo; the magnitude of the DNA-PK-mediated inhibition of Exo1 and other enzymes as well as the efficiency of MRN/ATM-mediated suppression will vary depending on the concentration of these factors in cells. Nevertheless, the suppression of DNA-PKcs inhibition of resection by ATM shown here and the opposing effects of DNA-PKcs and MRN in DNA end resection and ligation suggest that DNA-PKcs, ATM, and MRN could cooperatively regulate DSB resection and DNA repair pathway choice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Y. Yu and Susan Lees-Miller for purified DNA-PKcs; Dr. Dale Ramsden for purified ligase IV-XRCC4; Dr. David Chen for cell lines expressing wild-type and 6A mutant DNA-PKcs; Dr. Gaelle Legube for the U2OS cell line expressing AsiSI, and Soo-Hyun Yang for contributions to the in vitro resection assay. We are grateful to members of the Paull laboratory, Dr. Kyle Miller, and Dr. Dale Ramsden for helpful comments.

This work was supported by CPRIT Grant RP110465-P4.

Zhou, Y., Caron, P., Legube, G., and Paull, T. T. (2014) Nucleic Acids Res., in press.

- DSB

- double strand break

- HR

- homologous recombination

- DNA-PKcs

- DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit

- NHEJ

- nonhomologous end joining

- Exo1

- exonuclease 1

- MRN

- Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 complex

- ATM

- ataxia telangiectasia-mutated

- ATMi

- ATM inhibitor

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- 4-OHT

- 4-hydroxytamoxifen

- DNA-PKi

- DNA-PK inhibitor

- ssDNA

- single strand DNA

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- CtIP

- CtBP-interacting protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ciccia A., Elledge S. J. (2010) The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol. Cell 40, 179–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Trovesi C., Manfrini N., Falcettoni M., Longhese M. P. (2013) Regulation of the DNA damage response by cyclin-dependent kinases. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 4756–4766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Huertas P. (2010) DNA resection in eukaryotes: deciding how to fix the break. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 11–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Symington L. S., Gautier J. (2011) Double strand break end resection and repair pathway choice. Annu. Rev. Genet. 45, 247–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nicolette M. L., Lee K., Guo Z., Rani M., Chow J. M., Lee S. E., Paull T. T. (2010) Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 and Sae2 promote 5′ strand resection of DNA double strand breaks. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 1478–1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Niu H., Chung W. H., Zhu Z., Kwon Y., Zhao W., Chi P., Prakash R., Seong C., Liu D., Lu L., Ira G., Sung P. (2010) Mechanism of the ATP-dependent DNA end-resection machinery from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 467, 108–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cejka P., Cannavo E., Polaczek P., Masuda-Sasa T., Pokharel S., Campbell J. L., Kowalczykowski S. C. (2010) DNA end resection by Dna2-Sgs1-RPA and its stimulation by Top3-Rmi1 and Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2. Nature 467, 112–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhu Z., Chung W. H., Shim E. Y., Lee S. E., Ira G. (2008) Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double strand break ends. Cell 134, 981–994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mimitou E. P., Symington L. S. (2008) Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double strand break processing. Nature 455, 770–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eid W., Steger M., El-Shemerly M., Ferretti L. P., Peña-Diaz J., König C., Valtorta E., Sartori A. A., Ferrari S. (2010) DNA end resection by CtIP and exonuclease 1 prevents genomic instability. EMBO Rep. 11, 962–968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huertas P., Jackson S. P. (2009) Human CtIP mediates cell cycle control of DNA end resection and double strand break repair. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 9558–9565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen L., Nievera C. J., Lee A. Y., Wu X. (2008) Cell cycle-dependent complex formation of BRCA1·CtIP·MRN is important for DNA double strand break repair. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 7713–7720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dodson G. E., Limbo O., Nieto D., Russell P. (2010) Phosphorylation-regulated binding of Ctp1 to Nbs1 is critical for repair of DNA double strand breaks. Cell Cycle 9, 1516–1522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Quennet V., Beucher A., Barton O., Takeda S., Löbrich M. (2011) CtIP and MRN promote non-homologous end-joining of etoposide-induced DNA double strand breaks in G1. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 2144–2152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yuan J., Chen J. (2009) N terminus of CtIP is critical for homologous recombination-mediated double strand break repair. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 31746–31752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. You Z., Shi L. Z., Zhu Q., Wu P., Zhang Y. W., Basilio A., Tonnu N., Verma I. M., Berns M. W., Hunter T. (2009) CtIP links DNA double strand break sensing to resection. Mol. Cell 36, 954–969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morrison C., Sonoda E., Takao N., Shinohara A., Yamamoto K., Takeda S. (2000) The controlling role of ATM in homologous recombinational repair of DNA damage. EMBO J. 19, 463–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kühne M., Riballo E., Rief N., Rothkamm K., Jeggo P. A., Löbrich M. (2004) A double strand break repair defect in ATM-deficient cells contributes to radiosensitivity. Cancer Res. 64, 500–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang H., Shi L. Z., Wong C. C., Han X., Hwang P. Y., Truong L. N., Zhu Q., Shao Z., Chen D. J., Berns M. W., Yates J. R., 3rd, Chen L., Wu X. (2013) The interaction of CtIP and Nbs1 connects CDK and ATM to regulate HR-mediated double strand break repair. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Merkle D., Douglas P., Moorhead G. B., Leonenko Z., Yu Y., Cramb D., Bazett-Jones D. P., Lees-Miller S. P. (2002) The DNA-dependent protein kinase interacts with DNA to form a protein-DNA complex that is disrupted by phosphorylation. Biochemistry 41, 12706–12714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dobbs T. A., Tainer J. A., Lees-Miller S. P. (2010) A structural model for regulation of NHEJ by DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation. DNA Repair 9, 1307–1314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ding Q., Reddy Y. V., Wang W., Woods T., Douglas P., Ramsden D. A., Lees-Miller S. P., Meek K. (2003) Autophosphorylation of the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase is required for efficient end processing during DNA double strand break repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 5836–5848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reddy Y. V., Ding Q., Lees-Miller S. P., Meek K., Ramsden D. A. (2004) Non-homologous end joining requires that the DNA-PK complex undergo an autophosphorylation-dependent rearrangement at DNA ends. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 39408–39413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shibata A., Conrad S., Birraux J., Geuting V., Barton O., Ismail A., Kakarougkas A., Meek K., Taucher-Scholz G., Löbrich M., Jeggo P. A. (2011) Factors determining DNA double strand break repair pathway choice in G2 phase. EMBO J. 30, 1079–1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Meek K., Douglas P., Cui X., Ding Q., Lees-Miller S. P. (2007) trans-Autophosphorylation at DNA-dependent protein kinase's two major autophosphorylation site clusters facilitates end processing but not end joining. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 3881–3890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen B. P., Uematsu N., Kobayashi J., Lerenthal Y., Krempler A., Yajima H., Löbrich M., Shiloh Y., Chen D. J. (2007) Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) is essential for DNA-PKcs phosphorylations at the Thr-2609 cluster upon DNA double strand break. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 6582–6587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cui X., Yu Y., Gupta S., Cho Y. M., Lees-Miller S. P., Meek K. (2005) Autophosphorylation of DNA-dependent protein kinase regulates DNA end processing and may also alter double strand break repair pathway choice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 10842–10852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Neal J. A., Dang V., Douglas P., Wold M. S., Lees-Miller S. P., Meek K. (2011) Inhibition of homologous recombination by DNA-dependent protein kinase requires kinase activity, is titratable, and is modulated by autophosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 1719–1733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Allen C., Halbrook J., Nickoloff J. A. (2003) Interactive competition between homologous recombination and non-homologous end joining. Mol. Cancer Res. 1, 913–920 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Convery E., Shin E. K., Ding Q., Wang W., Douglas P., Davis L. S., Nickoloff J. A., Lees-Miller S. P., Meek K. (2005) Inhibition of homologous recombination by variants of the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PKcs). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 1345–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Davidson D., Coulombe Y., Martinez-Marignac V. L., Amrein L., Grenier J., Hodkinson K., Masson J. Y., Aloyz R., Panasci L. (2012) Irinotecan and DNA-PKcs inhibitors synergize in killing of colon cancer cells. Invest. New Drugs 30, 1248–1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. de Jager M., van Noort J., van Gent D. C., Dekker C., Kanaar R., Wyman C. (2001) Human Rad50/Mre11 is a flexible complex that can tether DNA ends. Mol. Cell 8, 1129–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zierhut C., Diffley J. F. (2008) Break dosage, cell cycle stage and DNA replication influence DNA double strand break response. EMBO J. 27, 1875–1885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yang S. H., Zhou R., Campbell J., Chen J., Ha T., Paull T. T. (2013) The SOSS1 single-stranded DNA binding complex promotes DNA end resection in concert with Exo1. EMBO J. 32, 126–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Durocher Y., Perret S., Kamen A. (2002) High-level and high-throughput recombinant protein production by transient transfection of suspension-growing human 293-EBNA1 cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, E9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee J. H., Paull T. T. (2005) ATM activation by DNA double strand breaks through the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 complex. Science 308, 551–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goodarzi A. A., Lees-Miller S. P. (2004) Biochemical characterization of the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) protein from human cells. DNA Repair 3, 753–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Iacovoni J. S., Caron P., Lassadi I., Nicolas E., Massip L., Trouche D., Legube G. (2010) High-resolution profiling of γH2AX around DNA double strand breaks in the mammalian genome. EMBO J. 29, 1446–1457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Massip L., Caron P., Iacovoni J. S., Trouche D., Legube G. (2010) Deciphering the chromatin landscape induced around DNA double strand breaks. Cell Cycle 9, 2963–2972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Miller K. M., Tjeertes J. V., Coates J., Legube G., Polo S. E., Britton S., Jackson S. P. (2010) Human HDAC1 and HDAC2 function in the DNA-damage response to promote DNA nonhomologous end-joining. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 1144–1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Paull T. T. (2010) Making the best of the loose ends: Mre11/Rad50 complexes and Sae2 promote DNA double strand break resection. DNA Repair 9, 1283–1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shrivastav M., De Haro L. P., Nickoloff J. A. (2008) Regulation of DNA double strand break repair pathway choice. Cell Res. 18, 134–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chan D. W., Chen B. P., Prithivirajsingh S., Kurimasa A., Story M. D., Qin J., Chen D. J. (2002) Autophosphorylation of the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit is required for rejoining of DNA double strand breaks. Genes Dev. 16, 2333–2338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Block W. D., Yu Y., Merkle D., Gifford J. L., Ding Q., Meek K., Lees-Miller S. P. (2004) Autophosphorylation-dependent remodeling of the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit regulates ligation of DNA ends. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 4351–4357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Long M. J., Gollapalli D. R., Hedstrom L. (2012) Inhibitor mediated protein degradation. Chem. Biol. 19, 629–637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Peng Y., Woods R. G., Beamish H., Ye R., Lees-Miller S. P., Lavin M. F., Bedford J. S. (2005) Deficiency in the catalytic subunit of DNA-dependent protein kinase causes down-regulation of ATM. Cancer Res. 65, 1670–1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Costanzo V. (2011) Brca2, Rad51 and Mre11: performing balancing acts on replication forks. DNA Repair 10, 1060–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hopkins B. B., Paull T. T. (2008) The P. furiosus mre11/rad50 complex promotes 5′ strand resection at a DNA double strand break. Cell 135, 250–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nimonkar A. V., Genschel J., Kinoshita E., Polaczek P., Campbell J. L., Wyman C., Modrich P., Kowalczykowski S. C. (2011) BLM-DNA2-RPA-MRN and EXO1-BLM-RPA-MRN constitute two DNA end resection machineries for human DNA break repair. Genes Dev. 25, 350–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Della-Maria J., Zhou Y., Tsai M. S., Kuhnlein J., Carney J. P., Paull T. T., Tomkinson A. E. (2011) Human Mre11/human Rad50/Nbs1 and DNA ligase IIIα/XRCC1 protein complexes act together in an alternative nonhomologous end joining pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 33845–33853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Paull T. T., Gellert M. (1998) The 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity of Mre 11 facilitates repair of DNA double strand breaks. Mol. Cell 1, 969–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Beucher A., Birraux J., Tchouandong L., Barton O., Shibata A., Conrad S., Goodarzi A. A., Krempler A., Jeggo P. A., Löbrich M. (2009) ATM and Artemis promote homologous recombination of radiation-induced DNA double strand breaks in G2. EMBO J. 28, 3413–3427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bolderson E., Tomimatsu N., Richard D. J., Boucher D., Kumar R., Pandita T. K., Burma S., Khanna K. K. (2010) Phosphorylation of Exo1 modulates homologous recombination repair of DNA double strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 1821–1831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Weterings E., Verkaik N. S., Brüggenwirth H. T., Hoeijmakers J. H., van Gent D. C. (2003) The role of DNA dependent protein kinase in synapsis of DNA ends. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 7238–7246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Uematsu N., Weterings E., Yano K., Morotomi-Yano K., Jakob B., Taucher-Scholz G., Mari P. O., van Gent D. C., Chen B. P., Chen D. J. (2007) Autophosphorylation of DNA-PKCS regulates its dynamics at DNA double strand breaks. J. Cell Biol. 177, 219–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shrivastav M., Miller C. A., De Haro L. P., Durant S. T., Chen B. P., Chen D. J., Nickoloff J. A. (2009) DNA-PKcs and ATM co-regulate DNA double strand break repair. DNA Repair 8, 920–929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jazayeri A., Falck J., Lukas C., Bartek J., Smith G. C., Lukas J., Jackson S. P. (2006) ATM- and cell cycle-dependent regulation of ATR in response to DNA double strand breaks. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 37–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Li S., Ting N. S., Zheng L., Chen P. L., Ziv Y., Shiloh Y., Lee E. Y., Lee W. H. (2000) Functional link of BRCA1 and ataxia telangiectasia gene product in DNA damage response. Nature 406, 210–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Richard D. J., Bolderson E., Cubeddu L., Wadsworth R. I., Savage K., Sharma G. G., Nicolette M. L., Tsvetanov S., McIlwraith M. J., Pandita R. K., Takeda S., Hay R. T., Gautier J., West S. C., Paull T. T., Pandita T. K., White M. F., Khanna K. K. (2008) Single-stranded DNA-binding protein hSSB1 is critical for genomic stability. Nature 453, 677–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lee B. S., Gapud E. J., Zhang S., Dorsett Y., Bredemeyer A., George R., Callen E., Daniel J. A., Osipovich O., Oltz E. M., Bassing C. H., Nussenzweig A., Lees-Miller S., Hammel M., Chen B. P., Sleckman B. P. (2013) Functional intersection of ATM and DNA-PKcs in coding end joining during V(D)J recombination. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 3568–3579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]