Abstract

Visual stimuli are known to induce various changes in the receptive field properties of adult cortical neurons, but the underlying mechanisms are not well understood. Repetitive pairing of stimuli at two orientations can induce a shift in cortical orientation tuning, with the direction and magnitude of the shift depending on the temporal order and interval between the pair. Although the temporal specificity of the effect on the order of tens of milliseconds strongly suggests spike-timing-dependent synaptic plasticity (STDP) as the underlying mechanism, it remains unclear whether the modification occurs within the cortex or at earlier stages of the visual pathway. In the present study, we examined the involvement of an intracortical mechanism in this functional modification. First, we measured interocular transfer of the shift induced by monocular conditioning. We found complete transfer of the effect at both the physiological and psychophysical levels, indicating that the modification occurs largely in the cortex. Second, we analyzed the spike timing of cortical neurons during conditioning and found it commensurate with the requirement of STDP. Finally, we compared the measured shift in orientation tuning with the prediction of a model circuit that exhibits STDP at intracortical connections. This model can account for not only the temporal specificity of the effect but also the dependence of the shift on both orientations in the conditioning pair. These results indicate that modification of intracortical connections is a key mechanism in the stimulus-timing-dependent plasticity in orientation tuning.

Visual stimuli are known to induce various changes in adult cortical circuits. For example, in contrast adaptation, a few seconds of visual stimulation can cause a marked reduction in the response amplitude of cortical neurons (1) along with changes in their spatial frequency tuning (2), orientation tuning (3, 4), and direction selectivity (5). These effects may be caused by a reduction in neuronal excitability (6, 7) or by short-term synaptic depression (8). Concurrent visual stimulation and iontophoretic activation of cortical neurons can induce changes in their orientation selectivity and ocular dominance (9-11). The dependence of these effects on the coincidence between visual and iontophoretic stimulation is consistent with Hebb's rule for synaptic modification. Similarly, synchronous stimulation of the receptive field (RF) center and part of the surround can induce an RF expansion toward the costimulated surround (12), which is also likely mediated by Hebbian synaptic modification. Together, these studies indicate a high degree of plasticity of adult cortical circuits. In this study, we focused on a form of cortical modification that is likely mediated by spike-timing-dependent synaptic plasticity (STDP) of synaptic connections.

In STDP, the direction and magnitude of synaptic modification depend on the order and interval between the pre- and postsynaptic spikes: Presynaptic spiking within tens of milliseconds before postsynaptic spiking induces synaptic potentiation, whereas spiking in the reverse order results in depression. This form of plasticity has been shown at many excitatory synapses (13-23). Theoretical studies have explored the potential roles of STDP in learning of sequences and temporal patterns (24-28), in competitive synapse stabilization (29-31), and in shaping the temporal response properties of sensory neurons (32, 33). These studies indicate that STDP is a powerful learning rule for solving a range of computational problems.

In the visual system, because timing of visual stimuli can directly affect timing of neuronal spiking, it may play an important role in activity-dependent circuit modification. Recent studies have demonstrated several stimulus-timing-dependent cortical modifications that appear to be mediated by STDP. In kitten visual cortex, pairing of oriented visual stimuli with electrical stimulation can induce a shift in the orientation map. Tuning of the neurons shifts toward the paired orientation if the cortex is activated visually before it is activated electrically and shifts away if the sequence is reversed (34). In adult primary visual cortex (V1), asynchronous pairing of visual stimuli at two orientations can also induce a shift in orientation tuning, with the direction and magnitude of the shift depending on the order and interval between the pair, consistent with the temporal specificity of STDP. Mirroring the plasticity of cortical neurons, similar conditioning also results in a shift in perceived orientation by human subjects, further suggesting the functional relevance of this phenomenon (35). Parallel to the plasticity in cortical representation of orientation, stimulus-timing-dependent modification was also found in the space domain (36).

Although the temporal specificity of these effects indicates the involvement of STDP, the site of synaptic modification underlying the functional plasticity remains unclear. In addition to modification of intracortical connections, which is shown to be important for experience-dependent cortical plasticity (37), changes at the feedforward thalamic connections may also contribute to cortical modification, because these connections are known to be important for shaping orientation tuning (38, 39). In the present study, we examined the role of intracortical mechanisms in the stimulus-timing-dependent plasticity in orientation tuning (35). First, we measured interocular transfer of the effect induced by monocular conditioning to determine the extent to which the modification occurs within the cortex (40, 41). Second, we assessed whether cortical spike timing during visual conditioning allows the induction of STDP of intracortical connections. Finally, we compared the temporal and orientation specificity of the effect with the prediction of a model circuit that exhibits STDP at intracortical connections. Our results support the hypothesis that stimulus-timing-dependent plasticity in orientation tuning is largely mediated by STDP of intracortical connections.

Materials and Methods

Visual Stimulation. Stimuli were generated with a personal computer and presented with a Viewsonic (Walnut, CA) PT813 monitor (40 × 30 cm, refresh rate 120 Hz). Luminance nonlinearity was corrected by software written in our lab.

Electrophysiology. Animal use procedure was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California, Berkeley. An adult cat (2-3 kg) was first anesthetized with isoflurane (3%, with O2), followed by sodium pentothal (10 mg/kg, i.v., supplemented as needed). During recording, anesthesia was maintained with sodium pentothal (3 mg/kg per hr, i.v.) and paralysis with pancuronium bromide (0.1-0.2 mg/kg per hr, i.v.). Pupils were dilated with 1% atropine sulfate and nictitating membranes retracted with 2.5% phenylephrine hydrochloride. Eyes were mechanically fixed and optically refracted. End-expiratory CO2 was kept at 4% and core body temperature at 38°C. ECG and electroencephalogram were monitored continuously.

Extracellular recording was made in V1 with tungsten electrodes (A-M Systems, Everett, WA). Unit isolation was based on cluster analysis of waveforms and the presence of a refractory period in autocorrelogram. All well isolated units were studied, regardless of laminar position. Both conditioning and mapping stimuli were sinusoidal gratings (100% contrast) in an area 1-2° larger than the classical RF. In each mapping block (48 s), drifting grating at optimal spatiotemporal frequency was presented at 12 orientations spanning 180° at a random sequence (3 s per orientation, 1 s between orientations). Each conditioning block (≈3 min) contained 1,600 conditioning pairs. In each pair, a grating (same spatial frequency as mapping stimulus) was flashed at two orientations in consecutive frames (interval: 8.3 ms), followed by 100 ms of resting <1 cd/m2 (Fig. 1). The phase of grating at each frame was chosen randomly from 0°, 90°, 180°, and 270° (arbitrary relative to preferred phase of the cell). For each cell, we first presented three to five mapping blocks to measure control orientation tuning, followed by interleaved conditioning and mapping blocks. In each experiment, conditioning at the same interval (8.3 or -8.3 ms) was repeated for one to three blocks to measure the cumulative effect. To measure interocular transfer, conditioning and mapping were presented to different eyes; in other experiments, they were presented to the dominant eye.

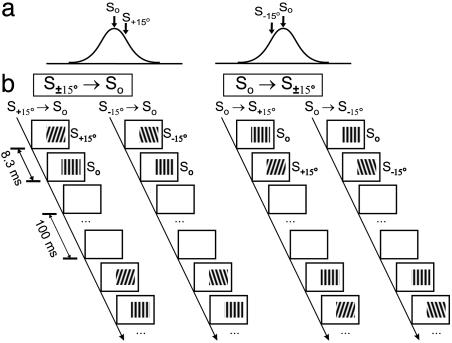

Fig. 1.

Conditioning stimuli used to induce shift in orientation tuning. (a) Orientations of conditioning stimuli (arrows) relative to tuning (curve) of the cell. So, optimal orientation; S+15° and S-15°, 15° clockwise and counterclockwise from optimal. (b) Four types of conditioning stimuli. For interocular transfer experiments, only So and S±15° (according to tuning measured through the conditioned eye) were used. To measure orientation specificity of the effect (Fig. 6), other orientations were also used.

Each tuning curve was fit with a Gaussian function  (r(θ: response at orientation θ; ro, r1, θ0, σ: free parameters). Conditioning-induced shift was measured by the difference between peak positions (θ0) of the fits before and after conditioning. Alternatively, the shift can be measured as the change in center of mass; the results were very similar. Only cells clearly tuned (circular variance V < 0.7,

(r(θ: response at orientation θ; ro, r1, θ0, σ: free parameters). Conditioning-induced shift was measured by the difference between peak positions (θ0) of the fits before and after conditioning. Alternatively, the shift can be measured as the change in center of mass; the results were very similar. Only cells clearly tuned (circular variance V < 0.7,  , Rk: response at θk; refs. 42 and 43) were used in the analysis. In total, 468 cells were included (45 simple, 423 complex; based on ref. 44). To measure interocular transfer, only cells that showed clear tuning (V < 0.7) through both eyes were used; all 50 cells were complex. Ocular dominance index (defined as (Ri - Rc)/(Ri + Rc), Ri and Rc are responses to optimal drifting gratings presented to ipsi- and contralateral eyes) ranged from 0 to ±0.5.

, Rk: response at θk; refs. 42 and 43) were used in the analysis. In total, 468 cells were included (45 simple, 423 complex; based on ref. 44). To measure interocular transfer, only cells that showed clear tuning (V < 0.7) through both eyes were used; all 50 cells were complex. Ocular dominance index (defined as (Ri - Rc)/(Ri + Rc), Ri and Rc are responses to optimal drifting gratings presented to ipsi- and contralateral eyes) ranged from 0 to ±0.5.

Psychophysics. Subjects viewed stimuli from 114 cm with free head and maintained fixation on a square (0.25 × 0.25°, 80 cd/m2). Both conditioning and testing gratings (1 cycle per degree, random phase, 50% contrast) were presented in a circular patch (diameter: 7°, centered at vertical meridian, 8° lower than fixation). In each conditioning pair, gratings at 7° clockwise (S+7°) and counterclockwise (S-7°) from vertical were flashed with an 8.3-ms interval, followed by 100 ms of resting (<1 cd/m2). Each conditioning block (12 s) contained 100 pairs. Each test block (18 s) contained 14 trials. In each trial, a grating was shown for 300 ms, with orientation randomly selected from seven values (0°, ±1°, ±2°, and ±3° from vertical). The subject judged whether it was tilted clockwise or counterclockwise during the 1-s interval between trials. Each session contained a control test block and three pairs of alternating conditioning and test blocks. Each subject had the same number of S-7° → S+7° and S+7° → S-7° sessions at a random sequence. The probit method was used to identify the orientation that is perceived to be vertical (50% threshold). Perceptual shift was measured as the difference in 50% threshold between the control test block and the average of all test blocks after conditioning. Interocular transfer was examined by comparing the perceived orientations measured through the right eye before and after conditioning through the left eye.

Model Circuit. The cortical model (Fig. 5a) uses recurrent circuitry similar to that in previous models (45-47), but unlike those models, it works in a regime where feedforward inputs play a dominant role in determining orientation tuning, and recurrent inputs are only modulatory. It consists of 36 orientation columns (0-180°), one cell per column. The intracellular voltage of the cell in the kth column at time t, Vk(t), is determined by:

|

Fig. 5.

Stimulus-timing-dependent shift in orientation tuning in a model circuit. (a Upper) Model circuit, containing feedforward inputs (green arrows) and excitatory (red) and inhibitory (blue) intracortical connections. Line thickness represents density of connections. Bar within each circle indicates preferred orientation. (Lower) Density distributions of excitatory (red) and inhibitory (blue) intracortical connections. (b) Raster plot of the responses of a model cell to So → S+15° and S+15° → So conditioning (Upper) and crosscorrelogram between them (Lower, spike-timing asymmetry was 3.3%). (c) Orientation tuning of a model neuron during control (solid line), after S+15° → So conditioning (dashed line) and after So → S+15° (dotted line) conditioning (interval: 8.3 ms). Vertical lines indicate peak positions of tuning curves. (d) Conditioning-induced shift in tuning as a function of conditioning interval. Dashed line, results of simulation; dot with error bar, shift (means ± SE) measured experimentally (35).

where τ0 (10 ms) is the membrane time constant (48),  denotes feedforward inputs (green arrows, Fig. 5a), and

denotes feedforward inputs (green arrows, Fig. 5a), and  denotes intracortical input from jth to kth column (red and blue lines, Fig. 5a).

denotes intracortical input from jth to kth column (red and blue lines, Fig. 5a).

is expressed as:

is expressed as:

|

([]+ denotes half-wave rectification; θk: preferred orientation of the cell; θff: stimulus orientation). Gff represents tuning of the feedforward input:

|

(Cff = 2.0, σff = 20°; ref. 49). Fff represents impulse response of feedforward input: Fff (t) = a2te-at-b2te-bt (a = 1/8 ms-1, b = 1/32 ms-1, following ref. 8). Because the spatial structure of RF was not considered, this model is more suitable for complex cells.

Vrec is expressed as:

|

where S(k → j) represents the strength of a single synapse from the kth to the jth column, which is modifiable according to STDP (see below). Rj is neuronal firing rate in the jth column, proportional to rectified intracellular voltage: Rj(t) = α[Vj(t) - Vt]+, where Vt (0.16) is the spiking threshold adjusted to obtain the normal tuning width of model neurons and to make their mean spike-timing asymmetry (3.3%) comparable to that of actual neurons (2.8%, see Results); α (2.0 ms-1) is adjusted to match the mean firing rates of model neurons (8.2 spikes per second) and actual neurons (8.5 spikes per second) during conditioning. The probability of spiking is determined by Pj(t) = βRj(t) (β = 1.0 ms, size of simulation time step); the spike train was simulated with a rate-modulated Poisson process. Grec_ext and Grec_inh represent densities of excitatory and inhibitory intracortical connections:

|

(red and blue curves, Fig. 5a). Crec_exc = 0.53, σEXC = 25°, Crec_inh = 0.36, σINH = 50°. Both Crec_exc and σEXC affect the magnitude of conditioning-induced tuning shift; σEXC can also affect the shape of Fig. 6b, but the effect is weak between 10°and 30°. We thus kept σEXC fixed at 25° and adjusted Crec_exc to fit the experimental result. σINH was set at 2σEXC somewhat arbitrarily, and it does not strongly affect the simulation results; Crec_inh was adjusted so that (Crec_exc·σEXC)/(Crec_inh·σINH) = 0.7, roughly based on ref. 46. Frec denotes impulse response of intracortical connections: Frec (t) = c2te-ct (c = 0.5 ms-1, following ref. 8). With these parameters, the orientation tuning of model cells is dominated by feedforward rather than intracortical inputs.

Fig. 6.

Orientation specificity of the effect of conditioning. (a) 2D representation of conditioning orientations. (Upper) Definition of θ1 and θ2. S1 and S2 represent the first and second gratings in the conditioning pair; curve represents tuning of the cell. (Lower) Each dot represents a combination of θ1 and θ2 used in experiments. Small outer plots depict stimulus configurations for selected points (indicated by arrows). (b) Conditioning-induced shift in tuning as a function of θ1 and θ2 predicted by the model. Magnitude of shift is represented by luminance (scale, Right). Diagonal line, θ1 = θ2, conditioning in which both gratings are at the same orientation. (c) Measured shifts in V1 orientation tuning at [θ1, θ2] indicated by dots in a (n = 14-74 per point). Arrowheads, data points significantly different from 0 (P < 0.03, Wilcoxon signed rank test). (d) Contour plot of the results shown in c.

The excitatory intracortical connection S changes after each pre-/postsynaptic spike pair: Sn(k → j) = Sn-1(k → j)(1 + ΔS (k → j)), S0(k → j) = 1.0 is the original value, and Sn is the strength after the nth pair. For pre → post pairs, ΔSLTP = d1e−|Δt|/τ1 (τ1 = 16.8 ms, d1 = 0.008); for post → pre pairs, ΔSLTD = d2e−|Δt|/τ2 (τ2 = 33.7 ms, d2 = -0.007) (17, 23). Because of the relatively low spike rate during conditioning, the occurrence of multispike burst is low, and the suppressive interspike interaction (23) in synaptic modification does not significantly affect the simulation results. Inhibitory intracortical connections were not modified, because the polarity of their modification appears to be insensitive to the order of pre- and postsynaptic spiking (50, 51). The feedforward inputs were also not modified, because the interocular transfer experiment indicates that the observed modification is largely intracortical (see Results). Simulated cortical modifications were induced by 1,600 conditioning pairs (one block).

Results

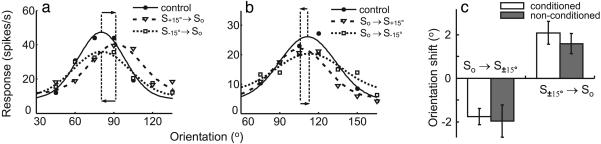

Interocular Transfer. Single-unit recordings were made in V1 of anesthetized adult cats. For each cell, we measured its orientation tuning through each eye separately; only cells that showed clear tuning through both eyes were used to measure interocular transfer (see Materials and Methods). During conditioning, gratings at the optimal orientation (So) and 15° from optimal (S+15° or S-15°) were flashed repeatedly at an interval of 8.3 ms (Fig. 1). In the previous study (35), we found that monocular presentation of such conditioning induced a shift in orientation tuning measured through the conditioned eye. Here we tested interocular transfer of the effect by measuring the shift in tuning through the nonconditioned eye. We found that after S+15° → So conditioning, the optimal orientation through the nonconditioned eye shifted toward S+15°, whereas S-15° → So conditioning induced a shift toward S-15° (Fig. 2a). Conditioning in the reverse order (So → S±15°), on the contrary, induced a shift away from the nonoptimal conditioning orientation (Fig. 2b). For the population of cells examined, 3-9 min of S±15° → So conditioning induced a shift of 1.6° ± 0.5° (SE, n = 72, P < 0.005, Wilcoxon signed rank test) toward the nonoptimal conditioning orientation, whereas 3-9 min of So → S±15° conditioning induced an opposite shift of 2.0° ± 0.7° (n = 28, P < 0.05) (Fig. 2c, filled bars). The magnitudes of these shifts were not significantly different from those measured previously (35) for the conditioned eye (Fig. 2c, open bars; for both S±15° → So and So → S±15°, P > 0.5, Wilcoxon rank sum test), indicating that the effect of monocular conditioning transfers completely to the nonconditioned eye. Because along the thalamocortical pathway visual signals from the two eyes converge substantially only after reaching V1, interocular transfer of the effect indicates that it is mediated largely by modifications within the cortex.

Fig. 2.

Interocular transfer of tuning shift in cat V1. (a) Orientation tuning of a cell measured through the contralateral eye during control (circles), after 9 min of S+15° → So conditioning through the ipsilateral eye (triangles), and after 9 min of S-15° → So ipsilateral conditioning (rectangles). Solid, dashed, and dotted curves represent Gaussian fits of the data. Vertical dashed lines indicate peak positions of the fits; horizontal arrows indicate directions of shifts. (b) Tuning of another cell measured through the contralateral eye during control, after 9 min of So → S+15° ipsilateral conditioning, and 9 min of So → S-15° conditioning. (c) Conditioning-induced shifts (means ± SE) in orientation tuning in a population of cells measured through the conditioned (open bars, n = 116 and 148 for So → S±15° and S±15° → So, respectively) and nonconditioned (filled bars, n = 28 and 72) eyes.

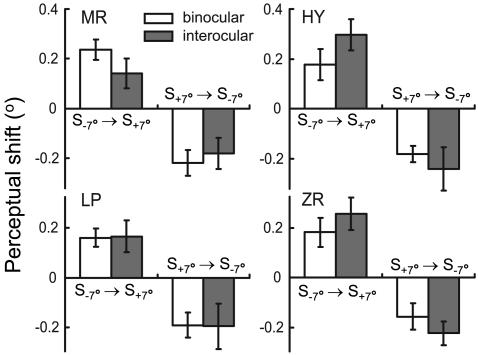

In addition to the modification of cortical orientation tuning, we also examined interocular transfer of the perceptual effect in human subjects. For conditioning, a pair of gratings at +7° and -7° from vertical (S+7° and S-7°) were flashed repeatedly with an interval of 8.3 ms. For testing, gratings at near-vertical orientations were used in a two-alternative forced-choice task to determine the orientation at which the grating was perceived to be vertical. For all four subjects tested, S-7° → S+7° monocular conditioning caused a shift in the perceived orientation through the nonconditioned eye toward S+7° (P < 0.05, Wilcoxon signed rank test), whereas S+7° → S-7° conditioning induced an opposite shift (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3, filled bars). The directions of these perceptual shifts were consistent with those expected from the shifts in cortical orientation tuning (35), and the magnitudes were not significantly different from those induced by binocular conditioning (Fig. 3, open bars; P > 0.2, Wilcoxon rank sum test). Thus, interocular transfer of conditioning-induced changes in orientation processing also occurs perceptually, further indicating that the modification arises within the cortex. Because the effect has been shown to depend on the relative timing of conditioning stimuli on the order of tens of milliseconds (35), it is likely mediated by STDP of intracortical connections.

Fig. 3.

Interocular transfer of perceptual shift in human (MR, LP, and ZR: naïve subjects; HY: author). Each bar represents shift (means ± SE) measured in 50-150 sessions (5-15 days). Open bars, shifts induced by binocular conditioning. Filled bars, shifts measured through the right eye induced by conditioning through the left eye.

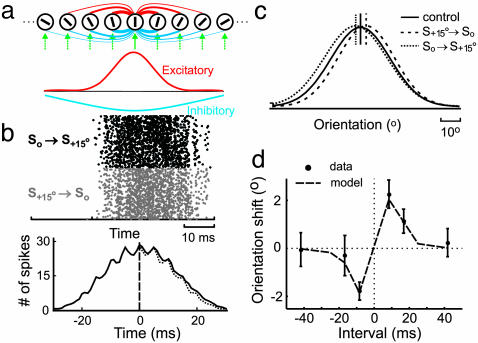

Cortical Spike Timing During Conditioning. Spike-timing-dependent modification of intracortical connections depends on interspike intervals between cortical neurons on the order of tens of milliseconds (22, 23). To assess the effectiveness of the conditioning stimuli in controlling cortical spike timing, we compared the responses of each neuron to Sa° → So and So → Sa° stimuli (or S-a° → So and So → S-a°, a = 15 or 22). We found that the cells exhibited a range of temporal precision. Fig. 4a shows the responses of a cell that precisely time-locked to the stimuli, with each conditioning pair evoking two distinct clusters of spikes. The crosscorrelogram between the responses to S+22° → So and So → S+22° (Fig. 4b) exhibited three peaks, with the two side peaks centered at approximately ±8 ms, corresponding to the conditioning interval. The area under the crosscorrelogram was larger on the right side, indicating that more than half of the spikes in response to S+22° → So lagged the spikes in response to So → S+22°. For most other neurons, although the spikes evoked by the conditioning pair were not temporally segregated (Fig. 4c), the crosscorrelograms were still asymmetric (Fig. 4d), indicating an overall difference in spike timing between the responses to S±a° → So and So → S±a°. Although in these experiments we did not record from the neurons that prefer orientation a°, their responses to So → S±a° stimuli should be similar to the response of the recorded neuron to S±a° → So. Thus, the spike timing difference observed in Fig. 4 a-d indicates that the conditioning stimuli can evoke asynchronous spiking between the recorded neuron and the neurons preferring a°, which may induce modification of their connections through STDP. Because pre-/postsynaptic interspike intervals within ±20 ms are most relevant for STDP, we estimated the difference between the number of spike pairs with positive intervals (intervals consistent with the order between the conditioning pair) and the number of pairs with negative intervals within ±20 ms (referred to as “spike-timing asymmetry”). For 54 neurons examined, we found a significant spike-timing asymmetry (Fig. 4e, 5.7 ± 2.3%, SE, P < 10-5, Wilcoxon signed rank test), suggesting that cortical spike timing during conditioning allows spike-timing-dependent modification of intracortical connections. When we computed the crosscorrelation between different cells (the response of one cell to S±15° → So and the response of another cell to So → S±15°), the mean spike-timing asymmetry over all pairwise combinations of the 54 cells was 2.8% (P < 0.02, Wilcoxon signed rank test). This value was used in subsequent modeling studies (see below).

Fig. 4.

Spike timing of V1 neurons in response to conditioning. (a) Raster plot of the responses of a complex cell to 1,600 pairs of S+22° → So (gray dots) and 1,600 pairs of So → S+22° (black dots) stimuli (interval: 8.3 ms). (b) Crosscorrelogram between the responses to S+22° → So and So → S+22° stimuli (solid curve), smoothed by a filter [0.2 0.6 0.2] (1 ms/bin). Dotted line, mirror image of the left side. c and d same as a and b, for another complex cell in response to S+15° → So and So → S+15° stimuli. Compared to the cell in a and b, the temporal precision of spiking in c and d is more common in V1, for both 15° and 22° conditioning angles. (e) Distribution of spike-timing asymmetry (number of spikes in the crosscorrelogram between 0 and 20 ms minus the number between -20 and 0 ms, divided by their sum) for 54 V1 cells. The results for 15° and 22° conditioning angles were similar and thus combined.

Stimulus-Timing-Dependent Plasticity in Model Circuit. Is modification of intracortical connections sufficient to explain the stimulus-timing-dependent shift in orientation tuning? To address this question, we generated a model circuit consisting of an array of cortical neurons with orientation preference ranging from 0° to 180° (Fig. 5a). Each neuron received both orientation-selective feedforward inputs (green arrows) and intracortical connections from other orientation columns (red and blue lines). Model parameters were adjusted so that both the mean rate and the temporal precision of spiking during conditioning were comparable to those for recorded V1 neurons (Fig. 5b). As shown in Fig. 5c (solid curve), the model neurons also exhibited orientation tuning similar to that found in cat V1. We then implemented STDP at the excitatory intracortical connections and applied asynchronous conditioning (Fig. 1) to the circuit. We found that S+15° → So conditioning (interval 8.3 ms) induced a rightward shift in tuning of the model neuron preferring 0° (Fig. 5c, dashed curve), and So → S+15° conditioning induced a leftward shift (dotted curve), consistent with the experimental finding. We also examined the temporal specificity of the effect by applying visual conditioning at ±8.3-, ±16.7-, and ±41.7-ms intervals. As shown in Fig. 5d, the shift in tuning as a function of conditioning interval agreed well with the result of our previous study (35), indicating that STDP of the excitatory intracortical connections can account for the temporal specificity of the effect.

Orientation Specificity. The pair of conditioning stimuli (Fig. 1) should selectively activate neurons with matched orientation preference; conditioning-induced synaptic modification in the cortical circuit should thus depend on both orientations in the pair. To examine the orientation specificity of the effect mediated by STDP of intracortical connections, we systematically varied both orientations (θ1 and θ2 in Fig. 6a) and plotted the shift in tuning of a model cell as a function of θ1 and θ2 (Fig. 6b). We found several robust features of this function. First, the shift was always in the direction of θ1-θ2, with a clockwise shift (positive) when θ1 was clockwise relative to θ2 (θ1 > θ2, below diagonal) and a counterclockwise shift when θ1 < θ2, consistent with the experimental result (Fig. 2). Second, the shift was found within a limited range of θ1-θ2 (distance from diagonal) with the maximum shift at|θ1 − θ2| ≅ 25°. The magnitude of the shift decreased either when θ1 and θ2 were too close, so that they activated the same population of cells, or when they were too far, so that the two populations of activated cells were not densely connected. Finally, a significant shift was observed even when the conditioning pair did not contain the preferred orientation of the neuron (i.e., points not on the horizontal or vertical axis). This is because, given the width of cortical orientation tuning, the conditioning stimuli activated multiple columns and induced synaptic modifications widely distributed in the circuit. Although the exact shape of the function shown in Fig. 6b can be affected by model parameters (see Discussion), the three features described above are observed consistently across a wide range of parameter values.

To test the above predictions, we examined the orientation specificity of cortical modification experimentally. Conditioning-induced shifts in orientation tuning were measured at various combinations of θ1 and θ2 (dots in Fig. 6a), and the results are shown both for the sampled points (Fig. 6c, n = 14-74 per point, n = 418 in total, 123/418 were from the previous study, ref. 35) and in a contour plot (Fig. 6d). All three features of the predicted function (Fig. 6b) were observed, and the overall profiles of the predicted and measured functions resembled each other. Thus, STDP of intracortical connections can also account for the orientation specificity of the effect.

Discussion

In the present study, we have demonstrated interocular transfer of conditioning-induced shift in orientation representation at both the physiological and perceptual levels, indicating that the effect is mediated largely by intracortical modifications. Although synaptic connections in earlier stages of the visual pathway, including thalamocortical connections, may also exhibit activity-dependent modification, they appear not to contribute to the stimulus-timing-dependent cortical modification induced by the oriented conditioning stimuli. Analysis of cortical spike trains showed that the conditioning stimuli can evoke asynchronous spiking of V1 neurons at a time scale of tens of milliseconds, allowing modifications of intracortical connections through STDP. Further experimental and simulation studies indicated that intracortical STDP is sufficient to account for both the temporal and orientation specificity of the effect. Together, these results indicate that intracortical synaptic modification is a key mechanism underlying the timing-dependent plasticity in orientation representation.

As in the previous study (35), the effect of conditioning on orientation tuning was demonstrated at the population rather than single-cell level. Because of the high response variability of the cortical cells and the limited time for mapping orientation tuning under each condition, it is difficult to demonstrate a significant effect at the single-cell level. In addition, the local cortical circuitry for each cell may be highly heterogeneous (e.g., different laminar locations and different distances from pinwheel centers), which may also contribute to the variability of the effect. Nevertheless, the significant effect at the population level is consistent with the conditioning-induced perceptual shift.

The purpose of the simulation study (Figs. 5 and 6) is to demonstrate that STDP of intracortical connections is sufficient to account for the conditioning-induced shift in orientation tuning. Of course, the predictions of the model depend quantitatively on the parameters. In particular, the function shown in Fig. 6b depends on both the strength and extent of intracortical connections. Although the parameter values used here (e.g., σEXC = 25°) are somewhat arbitrary (because direct measurements of these parameters are not available), the similarity between the predicted (Fig. 6b) and measured (Fig. 6d) effects certainly supports the plausibility of the model.

Previous studies indicate that, although feedforward connections may play a dominant role in determining orientation tuning (38, 39), intracortical connections may modulate this RF property (46, 52). Both short-term (53) and long-term (22, 23, 54) modifications of intracortical connections have been implicated in stimulus-induced changes in orientation tuning. For example, visual adaptation to a nonoptimal orientation can induce a shift in orientation tuning away from the adapted orientation (3, 55), which may be mediated by short-term plasticity of intracortical connections (56). Pairing of visual and iontophoretic activation of cortical neurons can also induce a shift in orientation tuning, which is likely mediated by intracortical synaptic modifications that depend on coincident pre- and postsynaptic activity (9-11). In the present study, dependence of the effect on the order and interval between the conditioning pair strongly indicates the involvement of STDP of intracortical connections, which has been shown to be a robust phenomenon in visual cortical slices (22, 23). Together, these studies underscore the importance of intracortical synaptic plasticity in dynamic modifications of cortical representation of orientation, which may confer significant functional advantages (4, 55, 57).

In addition to the asynchronously flashed stimuli used in the present study, a rotating stimulus may also activate cortical neurons in nearby orientation columns at short intervals and thus induce spike-timing-dependent modification of intracortical connections. The results of the present study raise an interesting possibility that rotating stimuli at certain velocities can cause rapid shifts in cortical representation of stimulus orientation. Because rotational motion is common in the visual environment, its effect on cortical modification may have important functional implications in natural vision.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yu-Xi Fu for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the National Eye Institute (R01 EY14887), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30300081), and the Joint Research Fund for Overseas Chinese Young Scholars (30028004).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: RF, receptive field; STDP, spike-timing-dependent synaptic plasticity.

References

- 1.Maffei, L., Fiorentini, A. & Bisti, S. (1973) Science 182, 1036-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Movshon, J. A. & Lennie, P. (1979) Nature 278, 850-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dragoi, V., Sharma, J. & Sur, M. (2000) Neuron 28, 287-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dragoi, V., Sharma, J., Miller, E. K. & Sur, M. (2002) Nat. Neurosci. 5, 883-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marlin, S. G., Hasan, S. J. & Cynader, M. S. (1988) J. Neurophysiol. 59, 1314-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carandini, M. & Ferster, D. (1997) Science 276, 949-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez-Vives, M. V., Nowak, L. G. & McCormick, D. A. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 4267-4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chance, F. S., Nelson, S. B. & Abbott, L. F. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18, 4785-4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fregnac, Y., Shulz, D., Thorpe, S. & Bienenstock, E. (1988) Nature 333, 367-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fregnac, Y., Shulz, D., Thorpe, S. & Bienenstock, E. (1992) J. Neurosci. 12, 1280-1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLean, J. & Palmer, L. A. (1998) Visual Neurosci. 15, 177-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eysel, U. T., Eyding, D. & Schweigart, G. (1998) NeuroReport 9, 949-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy, W. B. & Steward, O. (1983) Neuroscience 8, 791-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gustafsson, B., Wigstrom, H., Abraham, W. C. & Huang, Y. Y. (1987) J. Neurosci. 7, 774-780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markram, H., Lubke, J., Frotscher, M. & Sakmann, B. (1997) Science 275, 213-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang, L. I., Tao, H. W., Holt, C. E., Harris, W. A. & Poo, M. (1998) Nature 395, 37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bi, G. Q. & Poo, M. M. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18, 10464-10472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Debanne, D., Gahwiler, B. H. & Thompson, S. M. (1998) J. Physiol. 507, 237-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishiyama, M., Hong, K., Mikoshiba, K., Poo, M. M. & Kato, K. (2000) Nature 408, 584-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feldman, D. E. (2000) Neuron 27, 45-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boettiger, C. A. & Doupe, A. J. (2001) Neuron 31, 809-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sjostrom, P. J., Turrigiano, G. G. & Nelson, S. B. (2001) Neuron 32, 1149-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Froemke, R. C. & Dan, Y. (2002) Nature 416, 433-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abbott, L. F. & Blum, K. I. (1996) Cereb. Cortex 6, 406-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerstner, W., Kempter, R., van Hemmen, J. L. & Wagner, H. (1996) Nature 383, 76-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehta, M. R., Quirk, M. C. & Wilson, M. A. (2000) Neuron 25, 707-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts, P. D. (1999) J. Comput. Neurosci. 7, 235-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts, P. D. & Bell, C. C. (2000) J. Comput. Neurosci. 9, 67-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kistler, W. M. & van Hemmen, J. L. (2000) Neural Comput. 12, 385-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song, S., Miller, K. D. & Abbott, L. F. (2000) Nat. Neurosci. 3, 919-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song, S. & Abbott, L. F. (2001) Neuron 32, 339-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kempter, R., Gerstner, W. & van Hemmen, J. L. (2001) Neural Comput. 13, 2709-2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rao, R. P. N., Sejnowski, T. J. (2000) in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, eds. Solla, S. A., Leen, T. K. & Muller, K. R. (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA), pp. 164-170.

- 34.Schuett, S., Bonhoeffer, T. & Hubener, M. (2001) Neuron 32, 325-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yao, H. & Dan, Y. (2001) Neuron 32, 315-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu, Y. X., Djupsund, K., Gao, H., Hayden, B., Shen, K. & Dan, Y. (2002) Science 296, 1999-2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trachtenberg, J. T. & Stryker, M. P. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 3476-3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hubel, D. H. & Wiesel, T. N. (1962) J. Physiol. 160, 106-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferster, D. & Miller, K. D. (2000) Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 23, 441-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Volchan, E. & Gilbert, C. D. (1995) Vision Res. 35, 1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schoups, A. A. & Orban, G. A. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 7358-7362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leventhal, A. G., Thompson, K. G., Liu, D., Zhou, Y. & Ault, S. J. (1995) J. Neurosci. 15, 1808-1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ringach, D. L., Hawken, M. J. & Shapley, R. (1997) Nature 387, 281-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skottun, B. C., De Valois, R. L., Grosof, D. H., Movshon, J. A., Albrecht, D. G. & Bonds, A. B. (1991) Vision Res. 31, 1079-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ben-Yishai, R., Bar-Or, R. L. & Sompolinsky, H. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 3844-3848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Somers, D. C., Nelson, S. B. & Sur, M. (1995) J. Neurosci. 15, 5448-5465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carandini, M. & Ringach, D. L. (1997) Vision Res. 37, 3061-3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anderson J. S., Carandini, M. & Ferster, D. (2000) J. Neurophysiol. 84, 909-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gardner, J. L., Anzai, A., Ohzawa, I. & Freeman, R. D. (1999) Visual Neurosci. 16, 1115-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holmgren, C. D. & Zilberter Y. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 8270-8277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woodin, M. A., Ganguly, K. & Poo, M. M. (2003) Neuron 39, 807-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Douglas, R. J., Koch, C., Mahowald, M., Martin, K. A. & Suarez, H. H. (1995) Science 269, 981-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Varela, J. A., Sen, K., Gibson, J., Fost, J., Abbott, L. F. & Nelson, S. B. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 7926-7940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hirsch, J. A. & Gilbert, C. D. (1993) J. Physiol. 461, 247-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Muller, J. R., Metha, A. B., Krauskopf, J. & Lennie, P. (1999) Science 285, 1405-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Felsen, G., Shen, Y., Yao, H., Spor, G., Li, C. & Dan, Y. (2002) Neuron 36, 945-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Regan, D. & Beverley, K. I. (1985) J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2, 147-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]