Abstract

Classic but also novel roles of p53 are becoming increasingly well characterized. We previously showed that ex vivo retroviral transfer of mitochondrially targeted wild type p53 (mitop53) in the Eμ-myc mouse lymphoma model efficiently induces tumor cell killing in vivo. In an effort to further explore the therapeutic potential of mitop53 for its pro-apoptotic effect in solid tumors, we generated replication-deficient recombinant human Adenovirus type 5 vectors. We show here that adenoviral delivery of mitop53 by intratumoral injection into HCT116 human colon carcinoma xenograft tumors in nude mice is surprisingly effective, resulting in tumor cell death of comparable potency to conventional p53. These apoptotic effects in vivo were confirmed by Ad5-mitop53 mediated cell death of HCT116 cells in culture. Together, these data provide encouragement to further explore the potential for novel mitop53 proteins in cancer therapy to execute the shortest known circuitry of p53 death signaling.

Keywords: adenovirus, cancer, mitochondria, p53, therapy, xenograft

Introduction

The tumor suppressor p53 is the most commonly inactivated gene in human cancers. Therefore, restoring its function has long been pursued as an attractive approach to restrain cancer, a notion which is strongly supported by recent mouse models.1-3 Besides its classic transcription-dependent activities, evidence is mounting that the transcription-independent mitochondrial program of wtp53 is also an important effector of its proapoptotic function. A fraction of stress-induced p53 rapidly translocates to mitochondria including the mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM) early during p53-dependent apoptosis, but not during p53-independent apoptosis.4,5 This is a universal p53 apoptotic response and occurs in primary, immortal and transformed cultured cells as well as in radiosensitive normal tissues in vivo upon the entire gamut of p53-inducing stresses such as DNA damage, hypoxia and oncogene deregulation.4-7

Several synergistic mechanisms were identified so far: all link the p53 protein to the intrinsic mitochondrial death pathway by direct interaction with anti- and proapoptotic members of the BCL family of mitochondrial outer membrane permeability (MOMP) regulators. Endogenous mitochondrial p53 engages in complexes with the antiapoptotic outer membrane resident proteins BCLXL and BCL2, which normally inhibit apoptosis by blocking oligomerization of Bax and Bak and their association with BH3-only proteins.8 p53’s interaction antagonizes the membrane-stabilizing activity of Bcl2 and BclXL and releases proapoptotic BH3-only such tBid and BH123 effectors like Bak from preformed complexes with Bcl2 and BclXL. Mitochondrial p53 also releases Bak from inhibitory Bak-Mcl1 or Bak-IGFBP3 complexes by forming p53-Bak complexes instead, thereby activating Bak-dependent apoptosis. For example, the RNA polymerase II inhibitor α-amanitin, the primary mycotoxin in Amanites phalloides, causes fatal liver injury in vivo solely via the mitochondrial p53-Bak pathway.9 Moreover, in some settings upon stress, the p53 transcriptional target Puma can release p53 from inhibitory cytosolic p53/BclXL complexes to directly activate cytosolic Bax and undergo mitochondrial translocation and oligomerization.10 Finally, purified p53 added to healthy liver mitochondria causes Bak and Bax oligomerization and MOM permeabilization, inducing rapid and complete release of potent apoptotic activators like cytochrome c, SMAC and AIF.8,11,12 Thus, mitochondrial p53 functions analogously to a ‘super’ BH3-only type molecule, doubling as both an enabler and activator BH3-only type protein.

The direct apoptogenic role of mitochondrial p53 has been exploited by our laboratory by using mitochondrially-targeted p53 fusion proteins devoid of any residual transcriptional activity. We showed that they efficiently trigger apoptosis in human tumor cells in culture4,8,11 and in multiple genetic variants of a mouse B-lymphoma model in vivo.13,14 In the latter, mitochondrially targeted p53—delivered by ex vivo retroviral gene transfer—efficiently induces apoptosis and suppresses growth of primary Burkitt-type B-lymphomas of p53-null, p53-missense mutant or ARF-null genotypes.13,14 In this study, we take this one step further and test mitop53’s efficacy in solid human tumor xenografts via adenoviral delivery.

Results

Adenovirally-delivered mitochondrial p53 efficiently induces apoptosis in cultured human tumor cells

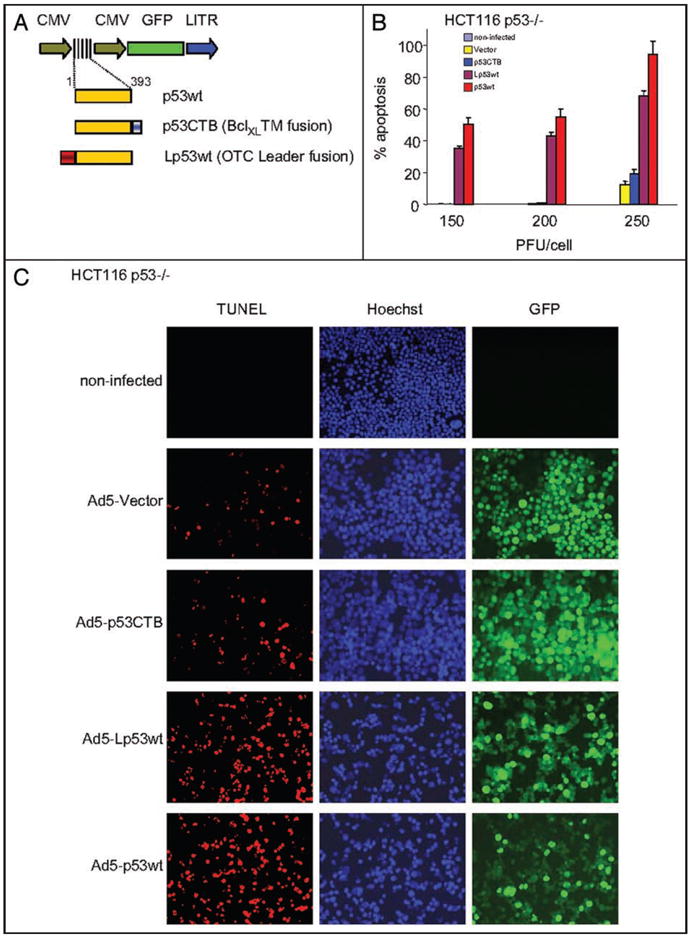

Recombinant replication-deficient adenovirus serotype 5 (Ad5) were constructed to deliver conventional p53 or two variants of mitochondrially-targeted p53 fusion proteins to cells (Fig. 1A, Suppl. Fig. 1). One of two mitochondrial targeting sequences were used. The surface-restricted CTB peptide localizes p53 to the outer mitochondrial membrane, while the non-restricted leader peptide localizes p53 both to the mitochondrial surface and directs its import. In extensive characterizations we previously showed that both sequences target p53 selectively to mitochondria but not to other organelles, completely bypass the nucleus and lack detectable transcriptional activity as assessed by artificial and endogenous reporter assays.8,14 Briefly, inserts were either human wild-type p53 (p53wt), p53 fused at the C-terminus to the transmembrane domain of BclXL (p53CTB), or p53 fused at the N-terminus to the mitochondrial leader peptide of ornithine transcarbamylase (Lp53wt). Control viruses lacked p53 inserts. To evaluate the ability of adenovirally-delivered mitop53 fusion proteins to induce apoptosis, HCT116 p53-/- cells grown in culture were infected with the viral constructs at increasing doses. As shown in Figure 1B and C, the apoptotic potency of the mitochondrially targeted Ad5-Lp53wt is robust and comparable to that of conventional Ad5-p53wt, with Lp53wt activities ranging from 73–83% of wtp53 efficiency. In some experiments the efficiency of Lp53wt reached 92% of that of wtp53 (data not shown). Moreover, the killing efficiency of Lp53wt, like that of the wtp53 control, was dose dependent (Fig. 1B). In contrast, adenoviral p53CTB is inefficient in inducing significant apoptosis in HCT116 cells. Expression of ectopic p53 from Figure 1B and C was verified by immunoblots (Fig. 1D). Moreover, as expected, mitochondrially-targeted p53 constructs localize exclusively to the cytoplasm (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

Adenovirally-delivered mitochondrial p53 efficiently induces apoptosis in cultured human tumor cells. (A) Scheme of recombinant human adenovirus type 5-green fluorescent protein (Ad5-GFP) constructs used in this paper. GFP is driven by a separate CMV promoter. p53 cassettes were either conventional human wild-type p53 (p53wt), wild type p53 fused at the C-terminus to the transmembrane domain of BclXL (p53CTB), or fused at the N-terminus to the mitochondrial leader peptide of ornithine transcarbamylase (Lp53wt). The control virus lacked p53 (Vector). (B) HCT116 p53-/- cells (1 × 106 cells) were infected with increasing doses of the indicated viruses. Forty-eight hrs after infection, floating and adherent cells were pooled and processed for TUNEL staining. The result shows the average of three independent experiments +/- SE. (C) Example of an experiment from (B) using 250 PFU/cell. (D) HCT116 p53-/- cells were infected with 250 PFU/cell of virus. Cells were lysed after 24 hrs and immnoblotted for p53 and GFP. PCNA is the loading control. (E) Both mitochondrially-targeted p53 fusion proteins delivered by Ad5 localize exclusively to the cytoplasm. Extensive previous studies have validated their exclusive mitochondrial localization. HCT116 p53-/- cells were infected with 50 PFU/cell. After 36 hrs, cells were processed for immunofluorescence with p53 monoclonal antibody DO1 and a TRITC-labeled secondary antibody. Nuclear counterstain with Hoechst 33342.

Intratumoral injection of human tumor xenografts with Ad5-mitop53 results in efficient tumor cell death with comparable potency to conventional Ad5-p53

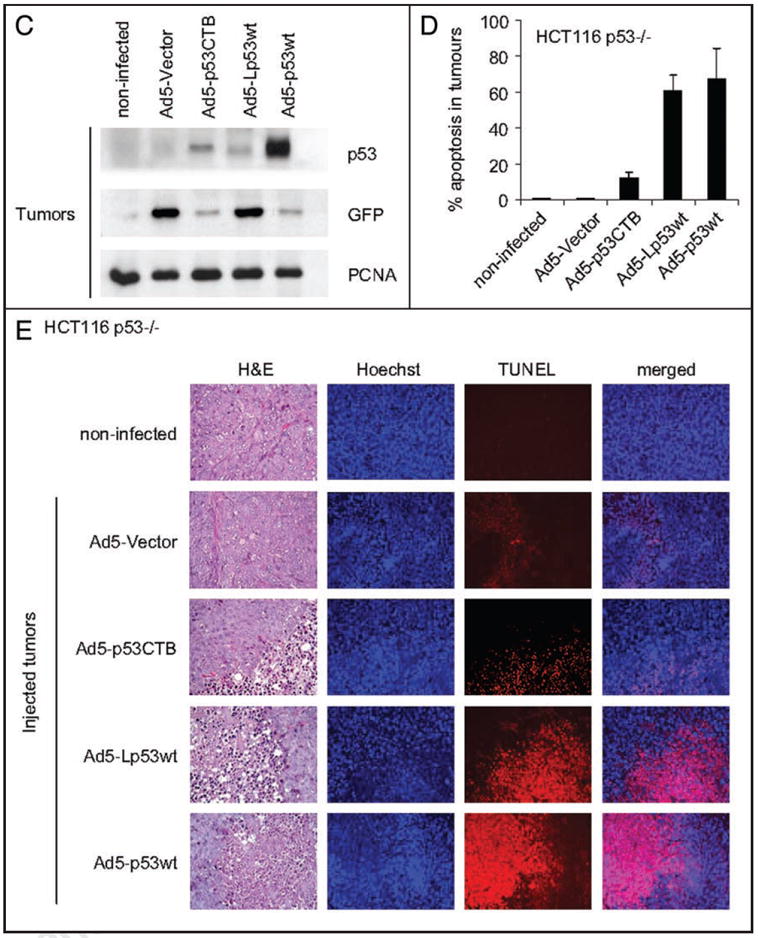

Next we generated HCT116 p53-/- xenograft tumors in nude mice (1 × 106 cells per site, 6 sites per mouse) (Fig. 2A). At day 10, when tumors had reached a size of 200–500 mm3, they were intratumorally injected with a fixed amount of recombinant virus (total of 8.82 × 109 PFU), delivered either by a single injection or fractionated over 3 days (days 10, 12 and 14). All mice were sacrificed at day 15. Fluorescent in vivo imaging at day 15 verified that the Ad5 viruses had efficiently infected tumor cells and expressed the recombinant proteins, as indicated by intratumoral GFP detectable through the skin for many although not all treated tumors (Fig. 2B middle). After dissection, all treated tumors showed readily detectable GFP fluorescence by imaging (Fig. 2B lower). p53 immunoblots on tumor homogenates verified expression of ectopic p53 (Fig. 2C). However, protein levels differed significantly, with conventional Ad5-p53wt expressing at much higher levels than both adenoviral mitop53 constructs. The reason for weak mitop53 expression despite the same viral backbone is currently unclear but represents room for future improvements in adenoviral constructs. Interestingly, with the exception of Ad5-p53CTB, an inverse correlation existed between p53 and GFP expression.

Figure 2.

Intratumoral injection of human tumor xenografts with Ad5-mitop53 results in efficient tumor cell death with comparable potency to conventional Ad5-p53. (A) Xenograft tumors were produced by subcutaneous injection of 106 cells per site of the human colon carcinoma cell line HCT116 p53-/- into the flanks of NIH-III nude mice. Arrows indicate the six standardized sites. Viruses were delivered by intratumoral injections into tumors No. 2–6 either by single bolus at day 10 or by fractionation into equal doses at days 10, 12 and 14. Tumor No. 1 was left non-injected. Tumors were harvested at day 15. (B) GFP expression in treated tumor xenografts is detectable in vivo. A total of 8.82 × 109 PFU per tumor was injected at days 10 in a volume of 40 μl, or fractionated over three days at days 10, 12 and 14 in equal doses in a volume of 25 μl each. Middle, At day 15, tumors were imaged for GFP transcutaneously in situ. Bottom, All dissected tumor nodules showed GFP expression, independent whether single or fractionated protocols were used. (C) Samples of tumors indicated in (B) were pooled. Proteins were isolated for immunoblot analysis of p53 and GFP (20 μg total protein per lane, PCNA as loading control). (D) Tumors were induced as in (A). At day 10, each tumor was injected with a single bolus of the indicated virus (8.82 × 109 PFU in 40 μl volume). Mice were sacrificed at day 15 and tumors processed for histology and TUNEL staining. The result shows the average +/- SE of at least 15 representative fields (20×) taken from all 6 injected tumors per construct. Images were acquired using the same parameters and apoptosis was calculated as percentage of red over green total pixels with AxioVision 4.5 software. (E) Representative fields from an experiment in (D) to evaluate tumor cell death. Note that non-injected tumors show a complete absence of background necrosis and cell death.

Importantly, intratumoral injections of xenografts with Ad5-Lp53wt resulted in efficient in vivo tumor cell death, exhibiting comparable potency to conventional Ad5-p53wt. As quantitated in Figure 2D, a single injection of 8.82 × 109 PFU at day 10 with Ad5-Lp53wt yielded 61% cell death in tumor nodules 5 days later, which compared favorably to 67% death obtained with conventional Ad5-p53wt. Examples of apoptotic tumor tissues at day 15 after a single viral injection are shown in Figure 2E. In comparison, Ad5-p53CTB, which exclusively targets p53 to the mitochondrial surface, yielded a relatively small effect with 12% apoptosis, in agreement with its low effect in vitro. Empty control virus, although inducing some mixed inflammatory infiltrate within the tumor nodules, failed to promote any tumor cell death. Of note, non-injected HCT116 tumor nodules showed a complete absence of background necrosis and cell death, an important parameter that enhances confidence in this kind of assay. Interestingly, for all constructs single bolus viral delivery at day 10 yielded higher degrees of tumor apoptosis at endpoint than fractionated protracted delivery of the same total viral load, at least in this cell system. Of note though, the relative potencies in fractionated delivery were maintained, with Lp53wt nearly as strong as conventional p53wt, while p53CTB was comparably weak (Suppl. Fig. 2). Thus, in this experimental setting the only advantage of a time-fractionated delivery was better verification of proper intratumoral delivery and adenoviral expression monitoring. In contrast, GFP levels after single bolus delivery at day 10 remained below detection for transcutaneous in vivo imaging at day 15, indicating that viral expression is limited to less than 5 days.

Taken together, the apoptotic response of adenovirally delivered mitop53 proteins observed in vivo is in concordance with results obtained in vitro in cultured cells.

Discussion

We show here for the first time the in vivo tumor killing efficacy of mitochondrially targeted p53 in a solid tumor xenograft model of human colon carcinoma. In this system, intratumoral injection of replication-deficient adenovirus appears to be an efficient delivery vehicle in vivo. Remarkably, despite the inability of mitop53 proteins to exert p53’s broad range of transcription functions to activate apoptotic target genes, the killing efficacies of one variant of mitop53 are comparable to conventional p53.

The differential in apoptotic efficacy between p53 exclusively delivered to the mitochondrial outer membrane (p53CTB) versus p53 delivered to the outer membrane and imported (Lp53wt) is intriguing (Figs. 1B and 2D) and consistent with our earlier data. In all systems where we compared, Lp53wt is reliably about 5-fold more potent in cell killing than MOM-restricted mitop53 versions (p53CTB, p53CTM). This is true for various cultured cells in vitro and the c-Myc lymphoma and xenograft models in vivo, and is independent of the type of delivery (transfection, retroviral or adenoviral infection) (data not shown).8,13 We showed earlier that matrix endopeptidases cleave off the leader peptide from imported Lp53wt, presumably allowing it to redistribute within mitochondrial subcompartments.4 This suggests additional as yet undefined intramitochondrial pro-death functions of p53 aside from its surface action of regulating MOM permeability via Bcl2 members.

According to a comprehensive database on gene therapy clinical trials (http://www.wiley.co.uk/genetherapy/clinical), a total of 1309 trials were conducted worldwide as of July 2007, with over 12,000 human subjects participating (67% in the US, 27% in Europe and 2.8% in Asia). Adenoviral vectors, mostly replication deficient, were the most commonly used vehicles (25%), followed by retroviral vectors (23%). Among them, 66% were for cancer treatment. Of the cancer gene therapy trials in solid tumors, 65 used recombinant human wild type p53, mostly by direct adenoviral delivery (rAd-p53) into the tumor as a single agent or in combination with conventional genotoxic therapy. China’s State Food and Drug Administration approved rAd5-p53 in 2003 for clinical use in HNSCC and licensed it under the name Gendicine. This approval was based on clinical trials reporting that after 3 months with intratumoral Gendicine injections plus radiotherapy 64% of patients had tumor regression, versus 19% of patients with radiotherapy alone.15,16 According to Shanwen Zhang Peking University School of Oncology, follow-up showed that the 3 year survival was 14% higher than in the radiotherapy-only group.17 Currently there is a paucity of clinical efficiency data reported in the English literature and the little data that has been published16 appears difficult to evaluate.15 Although skepticism and uncertainty has surrounded the use of gendicine, >4000 patients with multiple different cancer indications and of various ethnicity including a significant number of terminal cancer patients from Western countries travelling to China received Gendicine.18 Introgen Therapeutics (Austin, Texas) has conducted a number of phase III clinical trials with their very similar version of rAd5-p53 and is seeking to register it under the name of Advexin for the treatment of head and neck cancers and Li-Fraumeni Syndrome via intratumoral injection. In all these studies, rAd5-p53 treatments are reported to be well tolerated with only transient low toxicity such as flu-like symptoms with self-limiting fever and pain at the injection site. Thus, in sum although adenoviral-based p53 gene therapy certainly still has big hurdles to overcome with respect to immunogenicity and clinical efficacy, reason for cautious optimism of this principle therapeutic route does exist.

The conventional p53 substitution-based therapeutic approach largely relies on the preserved ability of tumor cells to respond with transcriptional activation of the plethora of p53 target genes. However, many human cancers have lost much of this prerequisite due to global epigenetic deregulation of their genomes, leading to broadly aberrant gene silencing patterns.19,20 Moreover, in conventional p53-based gene therapy,16,21-23 it is uncontrollable and unpredictable whether the target tumor responds with cell cycle arrest rather than the desired cell death, in particular if tumor cells express p21Waf1 which is typically the case, raising the threshold for an apoptotic outcome.24 Thus, the advantage of mitochondrially targeted p53-based gene therapy is two-fold: it bypasses the need for transcriptional reactivation and is focused to directly activate the mitochondrial death program and it eliminates cell cycle arrest/senescence outcomes in the tumor cell targets.

The present study significantly takes forward the notion that the direct mitochondrial p53 program, which executes the shortest known circuitry of p53 death signaling, might be exploited for effective tumor cell apoptosis in vivo. It strengthens the rationale and provides a platform for future preclinical studies of Ad5-mitop53, alone or in combination with genotoxic therapy and/or with conventional Ad5-p53. Moreover, it describes research tools to gain deeper insights into the pleiotopic mechanisms of p53-mediated apoptosis.

Material and Methods

Animals

All animals used in this study were 6–10 week old, virus-free male NIH-III nude mice (Taconic, USA). All experiments were performed in compliance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Cell culture

HEK293 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Human HCT116 p53-/- colon carcinoma cells were maintained in McCoy’s 5A medium with 10% FBS.

Recombinant adenovirus production

Replication-deficient (E1 region deleted) recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 (Ad5-GFP) were generated using the AdEasy Adenoviral Vector System (Stratagene). They contain a p53 cassette under the control of the CMV promoter (Fig. 1A and Suppl. Fig. 1). Human wild-type p53 fused to the transmembrane domain of BclXL (p53CTB) or to the mitochondrial import leader sequence of ornithine transcarbamylase (Lp53wt) were previously described.8,13 The empty control virus lacked the p53 insert. Briefly, cDNAs of wtp53 and mitop53 were PCR amplified with primers containing KpnI and XbaI restriction sites, sequence confirmed and cloned into pAdTrack-CMV shuttle vectors (gift from Dr. B. Vogelstein). The BJ5183 Ad1 strain of E. coli was transformed with the shuttle vectors to insert p53 into the adenoviral genome via homologous recombination. Viral DNA was purified, linearized and transfected into HEK293 cells which stably express the viral E1 gene. Virions were isolated from HEK293 by freeze-thawing, purified by ultracentrifugation in CsCl gradients and dialyzed against storage buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.4, 10 mM His, 75 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 100 μM EDTA, 0.5% v/v EtOH, 50% v/v glycerol). Viral particles were quantitated by spectrophotometry of viral DNA (1 unit OD260 contain 1012 virions, 100 virions constitute 1 PFU) and stored at -80°C until used.25

Xenograft tumor assays

Tumors were generated by injecting subcutaneously HCT116 p53-/- cells into standardized paravertebral sites (1 × 106 cells per site, 6 sites per mouse) (Fig. 2A). For injections, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane/pure oxygen. By day 10, tumors had reached a size between 200–500 mm3. Viruses were intratumorally injected either at day 10 only (8.82 × 109 PFU in 40 μl per tumor), or fractionated over 3 days at day 10, 12 and 14 (2.94 × 109 PFU in 25 μl per tumor per dose). All mice were sacrificed and tumors harvested at day 15.

For infection of cell cultures, viruses were directly added to the media. In all cases, 1 × 106 cells were seeded and allowed to attach for 6–7 hrs before adding virus.

Histology and immunofluorescence analysis

Tumor xenografts were paraffin embedded, sectioned and processed for histopathology by H&E staining or for apoptosis by red fluorescent TUNEL staining (Roche). For in vitro analysis, floating and attached cells from each plate were collected by trypsinization and pooled, counted and 2 × 105 cells cytospun onto a slide. Cells were air dried and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized for 15 min by TBST (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 0.1% Tween-20) and processed for TUNEL or immunostained with p53 antibody DO-1. Hoechst 33342 was used as nuclear counterstain. Microphotographs were acquired and composed using standardized parameters and an AxioCam MRm digital camera. Apoptosis was calculated as percentage of red over green total pixels in 4 (cytospin) or at least 15 (tumors) random 20x fields each, acquired with strictly standardized parameters and analyzed using the AxioVision 4.5 software (Zeiss MicroImaging).

Western blot analysis

For xenografts, one half of each tumor was pooled per mouse, minced, incubated in red blood cell lysis buffer for 5 min (155 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.3 mM EDTA, pH to 7.5) and centrifuged (1000 rpm for 5 min). The pellet was lysed in buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM, 1% Triton X-100, 10% Glycerol and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, Roche). For cultured cells, floating and attached cells were pooled and lysed. Total protein was separated on SDS-PAGE gels and immunoblotted with antibodies for p53 (DO-1), PCNA and GFP (Clontech, USA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Pamela Robertson from the David Lane lab for providing the Ad5-p53wt used in this work. This study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute to UMM.

Footnotes

Note

Supplementary materials can be found at: www.landesbioscience.com/supplement/PalaciosCC7-16-Sup.pdf

References

- 1.Martins CP, Brown-Swigart L, Evan GI. Modeling the therapeutic efficacy of p53 restoration in tumors. Cell. 2006;127:1323–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xue W, Zender L, Miething C, Dickins RA, Hernando E, Krizhanovsky V, Cordon-Cardo C, Lowe SW. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature. 2007;445:656–60. doi: 10.1038/nature05529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ventura A, Kirsch DG, McLaughlin ME, Tuveson DA, Grimm J, Lintault L, Newman J, Reczek EE, Weissleder R, Jacks T. Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature. 2007;445:661–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marchenko ND, Zaika A, Moll UM. Death signal-induced localization of p53 protein to mitochondria. A potential role in apoptotic signaling. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16202–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.21.16202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sansome C, Zaika A, Marchenko ND, Moll UM. Hypoxia death stimulus induces translocation of p53 protein to mitochondria. Detection by immunofluorescence on whole cells. FEBS Lett. 2001;488:110–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erster S, Mihara M, Kim RH, Petrenko O, Moll UM. In vivo mitochondrial p53 translocation triggers a rapid first wave of cell death in response to DNA damage that can precede p53 target gene activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6728–41. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6728-6741.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nemajerova A, Wolff S, Petrenko O, Moll UM. Viral and cellular oncogenes induce rapid mitochondrial translocation of p53 in primary epithelial and endothelial cells early in apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.09.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mihara M, Erster S, Zaika A, Petrenko O, Chittenden T, Pancoska P, Moll UM. p53 has a direct apoptogenic role at the mitochondria. Mol Cell. 2003;11:577–90. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leu JI, George DL. Hepatic IGFBP1 is a prosurvival factor that binds to BAK, protects the liver from apoptosis, and antagonizes the proapoptotic actions of p53 at mitochondria. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3095–109. doi: 10.1101/gad.1567107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chipuk JE, Bouchier-Hayes L, Kuwana T, Newmeyer DD, Green DR. PUMA couples the nuclear and cytoplasmic proapoptotic function of p53. Science. 2005;309:1732–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1114297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolff SES, Palacios G, Moll UM. p53’s mitochondrial translocation and MOMP action is independent of Puma and Bax and severely disrupts mitochondrial membrane integrity. Cell Research. 2008 doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.62. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leu JI, Dumont P, Hafey M, Murphy ME, George DL. Mitochondrial p53 activates Bak and causes disruption of a Bak-Mcl1 complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:443–50. doi: 10.1038/ncb1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palacios G, Moll UM. Mitochondrially targeted wild-type p53 suppresses growth of mutant p53 lymphomas in vivo. Oncogene. 2006;25:6133–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Talos F, Petrenko O, Mena P, Moll UM. Mitochondrially Targeted p53 Has Tumor Suppressor Activities In vivo. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9971–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo J, Xin H. Splicing out the West? Science. 2006;314:1232–5. doi: 10.1126/science.314.5803.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng Z. Current status of gendicine in China: recombinant human Ad-p53 agent for treatment of cancers. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:1016–27. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jia H. Controversial Chinese gene-therapy drug entering unfamiliar territory. Nature Reviews and Drug Discovery. 2006;5:260–1. doi: 10.1038/nrd2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim S, Peng Z, Kaneda Y. Current status of gene therapy in Asia. Mol Ther. 2008;16:237–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baylin SB, Ohm JE. Epigenetic gene silencing in cancer—a mechanism for early oncogenic pathway addiction? Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:107–16. doi: 10.1038/nrc1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herman JG, Baylin SB. Gene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2042–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim DS, Bae SM, Kwak SY, Park EK, Kim JK, Han SJ, Oh CH, Lee CH, Lee WY, Ahn WS. Adenovirus-Mediated p53 Treatment Enhances Photodynamic Antitumor Response. Hum Gene Ther. 2006 doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roth JA. Adenovirus p53 gene therapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2006;6:55–61. doi: 10.1517/14712598.6.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sauthoff H, Pipiya T, Chen S, Heitner S, Cheng J, Huang YQ, Rom WN, Hay JG. Modification of the p53 transgene of a replication-competent adenovirus prevents mdm2- and E1b-55 kD-mediated degradation of p53. Cancer Gene Ther. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waldman T, Zhang Y, Dillehay L, Yu J, Kinzler K, Vogelstein B, Williams J. Cell cycle arrest versus cell death in cancer therapy. Nat Med. 1997;3:1034–6. doi: 10.1038/nm0997-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furlong DB, Nibert ML, Fields BN. Sigma 1 protein of mammalian reoviruses extends from the surfaces of viral particles. J Virol. 1988;62:246–56. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.1.246-256.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.