Abstract

In the context of injury to the corticospinal tract (CST), brainstem-origin circuits may provide an alternative system of descending motor influence. However, subcortical circuits are largely under subconscious control. To improve volitional control over spared fibers after CST injury, we hypothesized that a combination of physical exercises simultaneously stimulating cortical and brainstem pathways above the injury would strengthen corticobulbar connections through Hebbian-like mechanisms. We sought to test this hypothesis in mice with unilateral CST lesions. Ten days after pyramidotomy, mice were randomized to four training groups: 1) postural exercises designed to stimulate brainstem pathways (BS); 2) distal limb-grip exercises preferentially stimulating CST pathways (CST); 3) simultaneous multimodal exercises (BS+CST); or 4) no training (NT). Behavioral and anatomical outcomes were assessed after 20 training sessions over four weeks. Mice in the BS+CST training group showed a trend toward greater improvements in skilled limb performance than mice in the other groups. There were no consistent differences between training groups in gait kinematics. Anatomically, multimodal BS+CST training neither increased corticobulbar fiber density of the lesioned CST rostral to the lesion nor collateral sprouting of the unlesioned CST caudal to the lesion. Further studies should incorporate electrophysiological assessment to gauge changes in synaptic strength of direct and indirect pathways between the cortex and spinal cord in response to multimodal exercises.

Keywords: spinal cord injury, corticospinal tract, pyramidotomy, exercise rehabilitation, reticulospinal

1. Introduction

The corticospinal tract (CST) plays an important role in control over skilled distal limb movements in mammals (Martin, 2005; Starkey et al., 2005). Though direct connections between the CST and spinal motor neurons have received more attention, indirect connections through synapses with brainstem neurons and segmental spinal interneurons also play a role in cortically directed movement (Alstermark and Ogawa, 2004; Alstermark et al., 2004; Matsuyama et al., 2004; Sasaki et al., 2004). We are interested in strengthening indirect cortico-motoneuron pathways as a strategy to improve recovery from injuries that damage direct CST connections (Martin, 2012). We propose to achieve this goal using a variation of Hebbian theory – repetitive coactivation of CST and brainstem pathways through a combination of targeted physical exercises should strengthen corticobulbar connections, thereby improving cortical control over subcortical circuits.

We previously reported the results of multimodal exercise training in a mouse model of partial cervical spinal cord injury (Harel et al., 2010). In that injury model, which largely spared the CST, multimodal exercise training improved performance in a skilled climbing task. In the present study, we aimed to assess whether multimodal exercise training improves recovery specifically from CST damage. We therefore conducted an experiment in mice that had undergone unilateral pyramidotomy (PyX) – lesion of the CST just rostral to its brainstem decussation (Cafferty and Strittmatter, 2006; Starkey et al., 2005). Mice in the present study underwent a more finely controlled set of training modalities than our previous study (Harel et al., 2010): combined CST and brainstem exercises; brainstem-targeted exercises; CST-targeted exercises; or no formal exercises. We measured the effects of these training paradigms on both skilled and generalized motor behaviors. Anatomically, we measured two distinct mechanisms of recovery: the ability of the injured CST to strengthen detour connections with brainstem tracts rostral to the lesion; and the ability of the uninjured CST to form detour connections with spinal neurons caudal to the lesion.

2. Results

2.1 Experimental design

Experimental steps are depicted in Figure 1. Behavioral testing was performed prior to surgery (T0), one week post-surgery (T1), and at the end of training (T2). PyX was performed contralateral to the preferred forelimb (determined through cylinder exploration at T0). Of 57 PyX mice, two were excluded at the T1 assessment due to functional deficits that were too severe. The remaining 55 PyX mice, as well as 10 sham-lesioned mice, were randomly assigned into cages of three to five animals that underwent different training regimens. Mice underwent 20 exercise sessions (30 minutes each) over four weeks, followed by repeat behavioral testing (T2) blinded to training assignment. To visualize the response of the injured CST rostral to the lesion, we injected the sensorimotor cortex of all mice on the ipsilesional side with the anterograde tracer biotinylated dextran amine (BDA) prior to sacrifice. In CRYM-GFP transgenic mice, we exploited the GFP label to visualize the response of the uninjured CST caudal to the lesion.

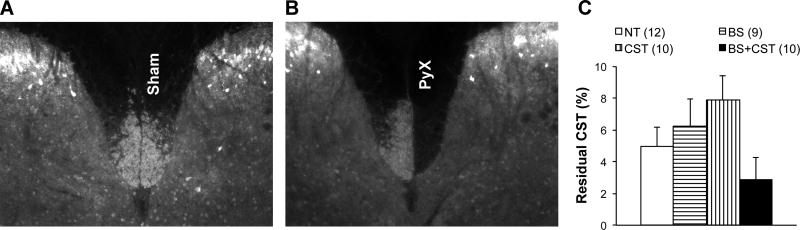

Figure 1. Study design.

After acclimation, baseline evaluation, and sham or PyX surgery, mice were randomly assigned to four different training groups for a total of 20 sessions. Following the final behavioral evaluation, the lesioned CST was injected with biotinylated dextran amine (BDA) to anatomically visualize the response of the lesioned CST rostral to injury.

2.2 Pyramidotomy causes reproducible unilateral CST lesions

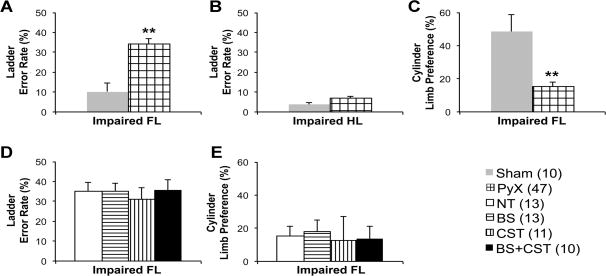

Lesion extent was determined by comparing the staining intensity of CST fibers in the lesioned relative to the unlesioned dorsal column in transverse cervical spinal sections caudal to the lesion. Sham-lesioned animals demonstrated no fiber loss in the targeted CST (Figure 2A), whereas PyX animals demonstrated nearly complete loss of CST immunoreactivity on the lesioned side (Figure 2B). Prior to unblinding of training group assignments, eight lesioned animals with greater than 20% CST sparing were excluded from the results (four from the BS+CST group, three from the CST group, and one from the NT group). There were no significant differences in lesion extent between remaining mice in the different training groups, although mice in the BS+CST group tended to have slightly more severe lesions than mice in the other groups (p=0.11 on one-way ANOVA) (Figure 2C)

Figure 2. PyX lesion quantification.

The dorsal CST was visualized in the cervical cord caudal to PyX lesion by staining for PKCγ or GFP as described in the Methods. Dorsal CST in a sham-lesioned animal (A) and PyX animal (B). (C) Residual CST in PyX mice randomized to the four different training groups. Mice in the BS+CST group had a trend toward more severe lesions than mice in the other groups. This trend did not reach statistical significance on ANOVA (p=0.11).

2.3 Pyramidotomy causes reproducible behavioral deficits

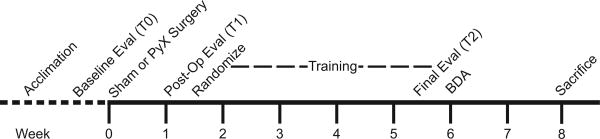

One week after surgery, prior to initiation of training, mice were observed on two behavioral tests of CST function – climbing an inclined ladder with irregularly spaced rungs, and forelimb exploration of a glass cylinder. Compared to sham-lesioned mice, PyX mice demonstrated a significant increase in placement errors of the impaired forelimb on the ladder-climbing task (p<0.001 on two-tailed t-test), and a dramatic decline in use of the impaired forelimb to explore the walls of a glass cylinder (p<0.001 on two-tailed t-test) (Figure 3). Impaired hindlimb placement errors were not significantly different between sham and PyX mice. Post hoc analysis confirmed that mice randomized to the different training groups had similar deficits before the initiation of training (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Baseline deficits on behavioral tests of CST function one week after PyX.

Panels A-C show a priori comparison between Sham and PyX groups. Panels D-E show post hoc comparison of baseline results in PyX mice randomized to the four training groups. (A, D) Error percentage of the impaired forelimb on inclined ladder climbing. (B) Error percentage of the impaired hindlimb on inclined ladder climbing. (C, E) Percentage use of the impaired forelimb in cylinder exploration. Legend includes animals per group in parentheses. **, p<0.001.

2.4 Training assignments

Following behavioral testing at one week post-surgery, PyX mice were randomly assigned to four training regimens (Methods and Table 1): 1) postural exercises stimulating brainstem pathways (BS); 2) distal limb-grip exercises stimulating CST pathways (CST); 3) simultaneous multimodal exercises (BS+CST); or 4) no training (NT). Sham-lesioned mice were randomized to two training regimens: BS+CST or NT. A typical training session is shown in Supplementary Movie 1.

Table 1.

Training regimen summary.

| UNTRAINED | BS | CST | MULTIMODAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SURFACE | SMOOTH | SMOOTH | GRID | GRID |

| MOVEMENT | STATIONARY | MOBILE | STATIONARY | MOBILE |

To measure overall exercise intensity among the different training regimens, we quantified movies representing training sessions from early and late periods of the training protocol. Using total path length as a proxy for exercise intensity, mice in the BS group moved slightly more (6,577 ± 737 pixels) than mice in the multimodal BS+CST group (6,094 ± 722 pixels), with mice in the CST (4,138 ± 297 pixels) and NT (3,192 ± 83) groups demonstrating lower overall motion on quantified films.

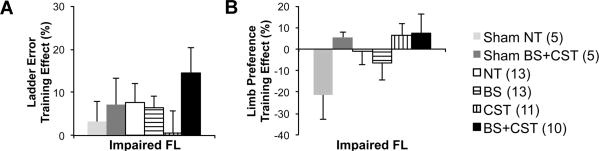

2.5 Effect of Multimodal training on skilled motor function

All mice tended to improve over time after injury. On the ladder-climbing task, mice in the BS+CST group showed a trend toward greater improvement in placement errors made by the impaired forelimb than mice in the other groups (p=0.23 on one-way ANOVA among lesioned animals) (Figure 4). Furthermore, mice in either the BS+CST or CST training groups showed a slight tendency to use the impaired forelimb to a greater extent during the cylinder exploration test (Figure 4). Interestingly, BS+CST training seemed to improve cylinder exploration using the impaired forelimb in sham-lesioned animals as well (p=0.05 on two-tailed t-test of trained compared to nontrained sham-lesioned animals). Given that BS trained mice experienced higher levels of activity during training than BS+CST trained mice, the improved performance of mice in the BS+CST group is not explained by differences in training intensity.

Figure 4. Effect of 20 training sessions on skilled forelimb behaviors.

Training effect refers to relative change in test performance between T2 (post-training) and T1 (post-surgery). (A) Impaired forelimb performance on inclined ladder climbing. Multimodal (BS+CST) training showed a tendency toward the biggest improvement (p=0.23 on one-way ANOVA among lesioned mice). (B) Percentage use of the impaired forelimb in cylinder exploration. CST and BS+CST training increased use of the impaired forelimb. Legend includes animals per group in parentheses.

2.6 General gait kinematics not affected by training

We measured gait kinematics during treadmill ambulation using reflective markers and high-speed cameras (Methods). Application of principal component analysis to 198 gait-related variables resulted in eight principal component groupings that explained 55% of the total gait kinematic variance (Supplementary Figure 1) (Courtine et al., 2009; Rosenzweig et al., 2010). We did not find consistently significant differences between the factor loading scores of mice in different training groups for these eight components. This lack of broader overall benefit on general ambulation is consistent with task-specific benefits conferred by training in a variety of animal models and human subjects with stroke and SCI (Garcia-Alias et al., 2009; Grasso et al., 2004; Magnuson et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2006).

2.7 Anatomical response of the injured CST rostral to the lesion

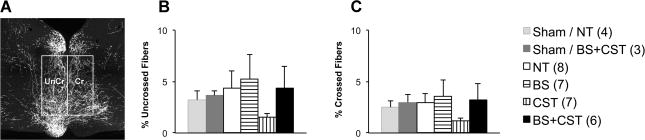

To label the lesioned CST rostral to injury, we injected the anterograde neural tracer biotinylated dextran amine (BDA) into the motor cortex ipsilateral to the pyramidal lesion. We were interested in measuring whether training affected growth or sprouting of corticofugal connections from the lesioned to CST to alternative descending brainstem tracts such as the reticulospinal tract. We therefore analyzed CST collateral fiber density in a medial pontine region of interest from which many reticulospinal fibers originate (Figure 5). Fiber density was analyzed separately on the ipsilesional and contralesional sides. Aside from an unexpected trend in CST mice toward decreased corticofugal fiber density in the pontine region of interest, overall fiber density did not significantly differ among PyX mice assigned to different training groups.

Figure 5. CST plasticity rostral to PyX.

(A) Transverse pontine sections rostral to the lesion were analyzed for biotinylated dextran amine (BDA)-labeled fiber density within rectangular regions of interest covering areas giving rise to descending reticulospinal fibers. No significant differences were seen among training groups in (B) uncrossed (UnCr) or (C) crossed (Cr) corticobulbar fibers.

2.8 Anatomical response of the uninjured CST caudal to the lesion

To label the intact CST caudal to the injury, we took advantage of the largely CST-specific GFP expression in CRYM-GFP transgenic mice. In transgenic PyX mice, GFP-positive fibers caudal to the lesion arise almost entirely from the non-lesioned CST (W. B. J. Cafferty and S. M. Strittmatter, unpublished results). We therefore measured the distribution of GFP-positive fibers within the grey matter of the cervical enlargement (Figure 6). We found no significant differences between training groups in the density of the intact CST's innervation of the cervical spinal cord, either on the intact or the denervated side (Figure 6).

Figure 6. CST plasticity caudal to PyX.

(A) In mice carrying the CRYM-GFP transgene, transverse cervical sections caudal to the lesion were analyzed for GFP-labeled fiber density representing the non-lesioned CST. Four rectangular regions of interest were analyzed along the dorsoventral axis on each side of the cord. No significant differences were seen among training groups in (B) uncrossed or (C) crossed fibers.

3. Discussion

Spared fiber plasticity plays a critical role in recovery from central nervous system injury (Harel and Strittmatter, 2006; Raineteau and Schwab, 2001). Stimulating neural activity promotes spared fiber plasticity and improves functional recovery (Brus-Ramer et al., 2007; Sadowsky and McDonald, 2009; van den Brand et al., 2012). We have attempted to accomplish this goal using physical exercises targeted toward spared neural circuits.

We previously investigated this exercise-based approach in a mouse model of incomplete cervical SCI (Harel et al., 2010). In that lesion model, which largely spared the CST from damage, we found that combined cortical-brainstem training improved performance in a skilled climbing task, whereas deletion of the Nogo66-Receptor (NgR1, Rtn4R) improved performance in grip strength and Rotarod testing. Exercise training did not synergize with the effect of deleting the Nogo66-Receptor.

The unilateral pyramidotomy lesion model used in the current study allowed us to focus on the response to multimodal training in the context of CST damage. We analyzed behaviors known to depend at least partly on CST-mediated control (ladder climbing and cylinder exploration), as well as on general gait kinematics. We found that multimodal exercises stimulating both CST and brainstem circuits simultaneously tended to improve skilled climbing more than single-modality exercises targeting either CST or brainstem circuits alone. Either CST-specific training or multimodal training tended to increase use of the impaired forelimb in a cylinder exploration task. Different training regimens had no effect on general gait kinematics or the CST's anatomical response to injury. Studies in many animal models of CNS injury have noted differences in recovery between training-specific and training-nonspecific behavior, as well as non-corresponding improvement between behavioral and anatomical recovery (Duffy et al., 2009; Garcia-Alias et al., 2009; Krisa et al., 2012).

Despite the trends noted in behavioral recovery, the results did not reach statistical significance on primary analysis. One factor that may have played a role is that despite randomized assignment, mice assigned to the multimodal training group tended to have more severe lesions on post hoc analysis than mice assigned to the other groups. However, this did not lead to obvious differences in behavioral testing at the T1 evaluation (post-PyX, pre-training).

Another possibility is that the dose of training in this study was too small: in the current study, mice trained for 20 sessions of 30 minutes each over four weeks. In the previous study, mice trained for roughly 75 sessions of 120 minutes each over four months. Whether a higher dose of training in the current study would have strengthened differences between training groups remains unknown. It should also be noted that unilateral CST lesion produced a minimal degree of behavioral dysfunction in our cohort – the benefits of specific forms of training may be more easily detected with more severe CNS damage and impairment.

Anatomically, we wondered whether training would differentially affect CST sprouting after PyX. Rostral to PyX, we focused on response of the lesioned CST by analyzing BDA-labeled collateral terminations within pontine areas rich in reticulospinal neurons. Caudal to PyX, we focused on response of the intact CST by analyzing GFP-labeled terminations within the ipsilesional and contralesional cervical cord. There was no clear trend between training groups in CST sprouting, either from the lesioned CST rostral to PyX, or from the intact CST caudal to PyX. This does not exclude the possibility that training might differentially modulate the strength of pre-existing corticobulbar synapses through Hebbian mechanisms. Electrophysiological analysis, which was not performed in this study, would be more effective than light microscopy to evaluate for changes in synaptic strength.

Despite these limitations, the results of the current study tend to support to the hypothesis that exercises designed to simultaneously stimulate spared corticospinal and brainstem pathways might provide an effective physical rehabilitation regimen. We speculate that multimodal exercises strengthen corticobulbar connections rostral to injury, leading to improved volitional control over spared subcortical circuits. Indirect pathways of cortical influence over spinal motor neurons provide a substrate for functional recovery from various types of CNS injury (Ballermann and Fouad, 2006; Jankowska and Edgley, 2006; Keizer and Kuypers, 1989; Martin, 2012; Riddle et al., 2009; Sasaki et al., 2004; van den Brand et al., 2012; Zaaimi et al., 2012).

Physical rehabilitation represents the main modality for assisting recovery – yet the precise type and dosage of neurological rehabilitation remains unknown (Dobkin, 2009). Additionally, detailed electrophysiological analysis of the effects of rehabilitation interventions are in some ways easier to conduct in humans than in animal models. We have therefore initiated an effort to translate the multimodal cortical-brainstem-targeted approach toward human patients with chronic thoracic SCI, comparing the effects against ‘traditional’ body weight-supported treadmill training (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01740128). Future studies of this approach in both humans and animal models should incorporate electrophysiological analysis of changes in synaptic strength between corticospinal and brainstem circuits.

4. Experimental Procedures

4.1 Animals

All experiments were performed with approval from the Yale Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were 8-week old female offspring of crosses between wild type C57/Bl6 mice and mice carrying a transgene expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the μ̃crystallin (CRYM) promoter. μ̃crystallin BAC-transgenic mice were procured from the Gene Expression Nervous System Atlas Project (NINDS Contracts N01NS02331 & HHSN271200723701C to The Rockefeller University (New York, NY)). The CRYM promoter directs GFP expression within layer V CST neurons and their descending spinal axons. Spinal GFP is exclusive to terminals of CST axons along with a small number of stochastic intraspinal neurons (W. B. J. Cafferty and S. M. Strittmatter, unpublished results). Transgenic mice have shown no difference from their non-transgenic littermates in development, anatomy, or behavior in any of our investigations to this point. Of 67 mice used in this study, 38 were positive for the CRYM-GFP transgene. Mice were housed in standard sized cages with ad libitum food and water and 12hr light-dark cycles. Throughout the experiment, we attempted to follow recommended guidelines in the conduct, evaluation, and reporting of animal studies (Kilkenny et al., 2010; Landis et al., 2012).

4.2 Surgery

Unilateral CST lesions (PyX) were performed contralateral to the preferred limb as determined by baseline forelimb preference testing (cylinder test). Animals that did not demonstrate a clear baseline forelimb preference underwent left-sided PyX. Mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal ketamine (100mg/kg) and xylazine (10mg/kg). The surgical site was shaved and swabbed with betadine and alcohol. A midline incision was made over the anterior cervical region, followed by blunt dissection to expose the ventral occipital bone just anterior to the foramen magnum. This portion of bone was chipped away with blunt forceps to expose the selected pyramid at the mid-pontine level. The pyramid was then carefully sectioned using microscissors, at a depth of approximately 0.25 mm, taking care to avoid the basilar artery. The skin was sutured with 4-0 vicryl. Sham-lesioned animals underwent all invasive steps except for pyramidal section. In the immediate post-operative period, mice were placed in a recovery cage kept at 37°, and given a subcutaneous dose of ampicillin (100mg/kg) and buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg). Mice were returned to their home cages once they had fully recovered from anesthesia. Mice received ampicillin/buprenorphine injections twice daily for the next 48h.

Biotinylated dextran amine tracing was performed two weeks prior to sacrifice. Briefly, BDA (10,000 MW, lysine-fixable; Invitrogen) was injected into the sensorimotor cortex ipsilateral to PyX (to trace the lesioned CST). A total of 300 nl was injected at each of five sites (coordinates from bregma: 1.0 mm anterior/0.5 mm lateral, 1.0 mm anterior/1.5 mm lateral, 0.5 mm anterior/1.0 mm lateral, 1.0 mm posterior/0.5 mm lateral, and 1.0 mm posterior/1.5 mm lateral). Animals received postoperative ampicillin/buprenorphine twice daily for 48h.

4.3 Training

We designed training regimens to separately or simultaneously invoke skilled forelimb use and postural reflexes. For the brainstem (BS) and multimodal (BS+CST) training groups, mice were placed onto fine wire mesh platforms (28 cm × 30 cm) suspended by an array of elastic bands that resulted in a continually shifting plane of motion as mice ambulated. The shifting platform motion stimulates vestibulospinal, reticulospinal, and other brainstem tracts involved in postural control (Stapley and Drew, 2009). The BS platform was covered with a smooth surface, whereas the BS+CST platform surface consisted of a fine wire hexagonal mesh (3 cm × 4 cm per hexagon). The wire grating is designed to preferentially stimulate CST circuits as mice execute distal forelimb movements to grasp the wires (Cafferty and Strittmatter, 2006; Thallmair et al., 1998). The CST training platform was fixed to a stationary surface. Untrained mice spent training sessions on a stationary smooth surface. All training was done in groups of 3 to 5 mice per platform.

The apparati as used in a typical training session are shown in Supplementary Video 1. Training began at 11-12 days post-surgery, and continued 30 minutes per day, 5 days per week for four weeks (20 sessions).

Training intensity was determined by analyzing movement during randomly selected portions of videos from early and late training sessions. Videos were thresholded, then total track lengths of mice on each of the training apparati were measured using the NIH Image J “MTrack2” plugin.

4.4 Behavioral evaluation

Mice were acclimated to each test before assessment. All evaluations were performed blinded to genotype, training assignment, and side of PyX lesion. After all behavioral assessments were completed and unblinded, scores for left and right limbs were translated into ‘impaired’ and ‘unimpaired’ as appropriate.

4.4.1 Inclined ladder

A ladder composed of rungs (3 mm diameter) spaced at irregular intervals (2 cm – 4.5 cm) was set at an incline of approximately 22 degrees. The ladder width was 5.5 cm. To prevent practice effects, rung spacing was randomly adjusted before each evaluation time point (Metz and Whishaw, 2002). Mice were videotaped as they climbed the inclined ladder over a length of 75 cm. Videos were scored for errors made during three consecutive climbs up the ladder. Paw misplacements counted as 1 error point. Limb slippage through the rungs to at least elbow or knee depth was scored as 2 error points. Summed error points for each limb across the three trials were divided by the number of steps taken by each limb to determine error percentage.

4.4.2 Cylinder test

Mice were videotaped for five minutes in a glass beaker largely as described (Starkey et al., 2005). Videos were reviewed and scored with the following simplification: For each rearing event, the first forepaw contact with the beaker wall was scored as ‘left’, ‘right’, or ‘bilateral’. After all behavioral assessments were completed and unblinded, ‘left’ and ‘right’ were translated into ‘impaired’ (I) and ‘unimpaired’ (U) as appropriate. The variable of interest was the percentage of impaired forepaw usage: I% = (I / (U+I+B)) * 100.

4.4.3 Gait kinematics

Mice were recorded with four high-speed cameras (Basler Vision Technologies) while running on a horizontal treadmill moving at 7 cm/s, essentially as described (Courtine et al., 2008; Duffy et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2011). Reflective markers (B&L Engineering) were glued bilaterally to the dorsal forepaw; the head of the humerus; the superior angle of the scapula; the greater trochanter; the knee; the lateral malleolus; and the dorsal hindpaw. SIMI motion-capture software (SIMI Reality Motion Systems) was used to extract gait parameters from recordings of at least four consecutive step cycles per animal. We used principal component analysis to sift through 198 parameters in an unbiased manner (Courtine et al., 2009). Eight principal component groupings were identified that explained 55% of the dataset's total variance. We compared the average factor loading scores of these component groups among animals assigned to different training groups.

4.5 Histological analysis

Tissue preparation

Under terminal anesthesia, animals were transcardially perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Dissected brains and spinal cords were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS overnight at 4°. Tissue blocks were embedded in 10% porcine gelatin (Sigma) prior to vibratome sectioning. 30μm transverse sections of the cervical cord (C5-C7) and brainstem (lower midbrain to upper medulla) were prepared. Every sixth section was stained.

Staining

Free-floating sections were treated with hydrogen peroxide and blocked with 10% normal donkey serum (Vector Labs). For GFP signal amplification, sections were incubated overnight at 4° with primary antibody (mouse monoclonal anti-GFP clone 3E6 1:500; Invitrogen), followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse (PerkinElmer), followed by FITC-conjugated tyramide (PerkinElmer). For PKCγ staining, sections were incubated overnight at 4° with primary antibody (rabbit anti-PKCγ 1:400; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by Alexa555-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody (Invitrogen). For BDA signal amplification, sections were incubated 30-45 minutes at room temperature with avidin-biotin complex (Vector Labs), followed by incubation with biotinyl-tyramide (PerkinElmer), followed by Alexa568-conjugated streptavidin (Invitrogen).

Image analysis

All image analysis was performed using NIH ImageJ while blinded to training assignment.

4.5.1 Lesion percent

Lesion extents were measured by comparing staining intensity of the lesioned to the unlesioned dorsal CST in the cervical enlargement. In non-transgenic mice, the dorsal CST was visualized by staining for endogenous PKCγ. In CRYM-GFP transgenic mice, the dorsal CST was visualized by amplifying the GFP signal. Intact CST fibers were defined as pixels within the regions of interest at least 5-fold (PKCγ) or 15-fold (GFP) higher than background intensity. Residual CST signal on the lesioned side was divided by the signal on the intact side to obtain the percentage of residual CST fibers. Lesion percentages were averaged across 4 or more sections per animal. Before unblinding training assignments, animals with greater than 20% CST sparing were excluded from behavioral or further anatomical analysis.

4.5.2 Brainstem CST sprouting

Sprouting of the lesioned CST rostral to PyX was visualized by staining for BDA within transverse pontine sections. To broadly cover areas giving rise to descending reticulospinal fibers, rectangular ROI measuring 1000 μm long by 500 μm wide were placed 400 μm superior to the ventral edge and 100 μm lateral to the central canal on each side (Figure 5). Sections were thresholded to 3x background. The mean percent of pixels above threshold per ROI were determined for multiple sections from each animal. Results were normalized for BDA labeling efficiency as determined by intensity within the ventral pyramidal tract just rostral to the lesion (Reitmeir et al., 2011). After unblinding training assignments, results were averaged among animals of each training group.

4.5.3 Cervical CST sprouting

Sprouting of the unlesioned CST caudal to the lesion was visualized in CRYM-GFP mice by staining for the transgenic GFP signal. Rectangular regions of interest (75 μm wide) were placed along the dorsoventral axis at 150, 300, 450, and 600 μm lateral to the central canal (Figure 6). Vertical plot profiles of the thresholded image were then measured within each ROI, and binned into 100 μm increments from dorsal to ventral. After unblinding training assignments, mean values per bin per ROI per animal were averaged among animals of each training group.

4.6 Statistical analysis

To compare behavioral deficits at one week post-lesion, t-tests were performed comparing sham-lesioned vs PyX mice (Figure 3A), and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used post hoc to test for significant differences among PyX mice assigned to the four training groups.

To compare PyX lesion percentage, one-way ANOVA was used to test for significant differences among PyX mice assigned to the four training groups (Figure 2).

To compare behavioral outcomes after the training period, one-way ANOVA was used to test for significant differences in the change from baseline among mice in the four PyX groups, and two-tailed t-tests were performed to compare mice in the two sham groups (Figure 4). Likewise, one-way ANOVA among the four PyX groups was used to test for significant differences in anatomical CST fiber density rostral and caudal to the lesion (Figures 5 and 6).

Statistical analysis of general gait kinematics was performed using principal component analysis as described (Courtine et al., 2009).

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significance was set at p<0.05. Excel (Microsoft), SPSS version 20 (IBM), and JMP 8.0 (SAS) software was used.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1 – Principal component analysis of gait kinematics. As described in the methods, 198 gait-related variables were derived from films of mice walking on a treadmill. These variables were compared among different training groups using principal component analysis. (A) Scree plot showing the contribution of each principal component to the total variance of the dataset. The first eight components, explaining 55% of the total variance, are highlighted in red. (B) Gait variables with absolute factor loading scores of >0.5 are shown for each component. (C) Three-dimensional scatter plot of mean factor loading scores (for components 6, 7, and 8) in individual mice of each training group. No consistent differences were found between mice of each training group. Full kinematic datasets and tables openly available upon request.

Supplementary Movie 1 – Video of a typical training session. In clockface coordinates, BS+CST platforms are at 12 and 2 o'clock; an NT area is at 4 o'clock; a CST platform is at 7 o'clock; and a BS platform is at 10 o'clock.

Highlights.

Spared brainstem circuits offer an alternate route for motor control after injury

Co-activating cortical and brainstem circuits may strengthen corticobulbar synapses

This hypothesis was tested in mice with unilateral corticospinal injury

Multimodal cortical and brainstem exercises tended to improve behavioral recovery

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants to S.M.S. from the NINDS, the Falk Medical Research Trust, the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation, and the Wings for Life Foundation, and a career development award to N.Y.H. from the NINDS. We also appreciate the help of Christopher Cardozo and Lauren Collier.

Abbreviations

- PyX

pyramidotomy

- CRYM

µ-crystallin

- BS

brainstem

- NT

non-trained

- BDA

biotinylated dextran amine

- NgR1

Nogo66-receptor

- MW

molecular weight

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- PKCγ

protein kinase C-gamma

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: S.M.S. is a co-founder of Axerion Therapeutics, which seeks to develop NgR antagonist therapy for CNS injury.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Noam Y. Harel, Email: noam.harel@mssm.edu.

Kazim Yigitkanli, Email: kazim.yigitkanli@yale.edu.

Yiguang Fu, Email: yiguang.fu@yale.edu.

William B. J. Cafferty, Email: william.cafferty@yale.edu.

Stephen M. Strittmatter, Email: stephen.strittmatter@yale.edu.

References

- Alstermark B, Ogawa J. In vivo recordings of bulbospinal excitation in adult mouse forelimb motoneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:1958–1962. doi: 10.1152/jn.00092.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alstermark B, Ogawa J, Isa T. Lack of monosynaptic corticomotoneuronal EPSPs in rats: disynaptic EPSPs mediated via reticulospinal neurons and polysynaptic EPSPs via segmental interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:1832–1839. doi: 10.1152/jn.00820.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballermann M, Fouad K. Spontaneous locomotor recovery in spinal cord injured rats is accompanied by anatomical plasticity of reticulospinal fibers. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:1988–1996. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brus-Ramer M, Carmel JB, Chakrabarty S, Martin JH. Electrical stimulation of spared corticospinal axons augments connections with ipsilateral spinal motor circuits after injury. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13793–13801. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3489-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafferty WB, Strittmatter SM. The Nogo-Nogo receptor pathway limits a spectrum of adult CNS axonal growth. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12242–12250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3827-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtine G, Gerasimenko Y, van den Brand R, Yew A, Musienko P, Zhong H, Song B, Ao Y, Ichiyama RM, Lavrov I, et al. Transformation of nonfunctional spinal circuits into functional states after the loss of brain input. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1333–1342. doi: 10.1038/nn.2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtine G, Song B, Roy RR, Zhong H, Herrmann JE, Ao Y, Qi J, Edgerton VR, Sofroniew MV. Recovery of supraspinal control of stepping via indirect propriospinal relay connections after spinal cord injury. Nat Med. 2008;14:69–74. doi: 10.1038/nm1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin BH. Motor rehabilitation after stroke, traumatic brain, and spinal cord injury: common denominators within recent clinical trials. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22:563–569. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283314b11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy P, Schmandke A, Sigworth J, Narumiya S, Cafferty WB, Strittmatter SM. Rho-associated kinase II (ROCKII) limits axonal growth after trauma within the adult mouse spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15266–15276. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4650-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy P, Wang X, Siegel CS, Tu N, Henkemeyer M, Cafferty WB, Strittmatter SM. Myelin-derived ephrinB3 restricts axonal regeneration and recovery after adult CNS injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5063–5068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113953109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Alias G, Barkhuysen S, Buckle M, Fawcett JW. Chondroitinase ABC treatment opens a window of opportunity for task-specific rehabilitation. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1145–1151. doi: 10.1038/nn.2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso R, Ivanenko YP, Zago M, Molinari M, Scivoletto G, Lacquaniti F. Recovery of forward stepping in spinal cord injured patients does not transfer to untrained backward stepping. Exp Brain Res. 2004;157:377–382. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-1973-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel NY, Song KH, Tang X, Strittmatter SM. Nogo Receptor Deletion and Multimodal Exercise Improve Distinct Aspects of Recovery in Cervical Spinal Cord Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:2055–2066. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel NY, Strittmatter SM. Can regenerating axons recapitulate developmental guidance during recovery from spinal cord injury? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:603–616. doi: 10.1038/nrn1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska E, Edgley SA. How can corticospinal tract neurons contribute to ipsilateral movements? A question with implications for recovery of motor functions. Neuroscientist. 2006;12:67–79. doi: 10.1177/1073858405283392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keizer K, Kuypers HG. Distribution of corticospinal neurons with collaterals to the lower brain stem reticular formation in monkey (Macaca fascicularis) Exp Brain Res. 1989;74:311–318. doi: 10.1007/BF00248864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krisa L, Frederick KL, Canver JC, Stackhouse SK, Shumsky JS, Murray M. Amphetamine-enhanced motor training after cervical contusion injury. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:971–989. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis SC, Amara SG, Asadullah K, Austin CP, Blumenstein R, Bradley EW, Crystal RG, Darnell RB, Ferrante RJ, Fillit H, et al. A call for transparent reporting to optimize the predictive value of preclinical research. Nature. 2012;490:187–191. doi: 10.1038/nature11556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson DS, Smith RR, Brown EH, Enzmann G, Angeli C, Quesada PM, Burke D. Swimming as a model of task-specific locomotor retraining after spinal cord injury in the rat. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair. 2009;23:535–545. doi: 10.1177/1545968308331147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JH. The corticospinal system: from development to motor control. Neuroscientist. 2005;11:161–173. doi: 10.1177/1073858404270843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JH. Systems neurobiology of restorative neurology and future directions for repair of the damaged motor systems. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114:515–523. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama K, Mori F, Nakajima K, Drew T, Aoki M, Mori S. Locomotor role of the corticoreticular-reticulospinal-spinal interneuronal system. Prog Brain Res. 2004;143:239–249. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)43024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz GA, Whishaw IQ. Cortical and subcortical lesions impair skilled walking in the ladder rung walking test: a new task to evaluate fore- and hindlimb stepping, placing, and co-ordination. Journal of neuroscience methods. 2002;115:169–179. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raineteau O, Schwab ME. Plasticity of motor systems after incomplete spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:263–273. doi: 10.1038/35067570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitmeir R, Kilic E, Reinboth BS, Guo Z, ElAli A, Zechariah A, Kilic U, Hermann DM. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces contralesional corticobulbar plasticity and functional neurological recovery in the ischemic brain. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;123:273–284. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0914-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle CN, Edgley SA, Baker SN. Direct and indirect connections with upper limb motoneurons from the primate reticulospinal tract. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4993–4999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3720-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig ES, Courtine G, Jindrich DL, Brock JH, Ferguson AR, Strand SC, Nout YS, Roy RR, Miller DM, Beattie MS, et al. Extensive spontaneous plasticity of corticospinal projections after primate spinal cord injury. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1505–1510. doi: 10.1038/nn.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowsky CL, McDonald JW. Activity-based restorative therapies: concepts and applications in spinal cord injury-related neurorehabilitation. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15:112–116. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki S, Isa T, Pettersson LG, Alstermark B, Naito K, Yoshimura K, Seki K, Ohki Y. Dexterous finger movements in primate without monosynaptic corticomotoneuronal excitation. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:3142–3147. doi: 10.1152/jn.00342.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RR, Burke DA, Baldini AD, Shum-Siu A, Baltzley R, Bunger M, Magnuson DS. The Louisville Swim Scale: a novel assessment of hindlimb function following spinal cord injury in adult rats. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:1654–1670. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapley PJ, Drew T. The pontomedullary reticular formation contributes to the compensatory postural responses observed following removal of the support surface in the standing cat. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:1334–1350. doi: 10.1152/jn.91013.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkey ML, Barritt AW, Yip PK, Davies M, Hamers FP, McMahon SB, Bradbury EJ. Assessing behavioural function following a pyramidotomy lesion of the corticospinal tract in adult mice. Exp Neurol. 2005;195:524–539. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thallmair M, Metz GA, Z'Graggen WJ, Raineteau O, Kartje GL, Schwab ME. Neurite growth inhibitors restrict plasticity and functional recovery following corticospinal tract lesions. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:124–131. doi: 10.1038/373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Brand R, Heutschi J, Barraud Q, DiGiovanna J, Bartholdi K, Huerlimann M, Friedli L, Vollenweider I, Moraud EM, Duis S, et al. Restoring voluntary control of locomotion after paralyzing spinal cord injury. Science. 2012;336:1182–1185. doi: 10.1126/science.1217416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Duffy P, McGee AW, Hasan O, Gould G, Tu N, Harel NY, Huang Y, Carson RE, Weinzimmer D, et al. Recovery from chronic spinal cord contusion after nogo receptor intervention. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:805–821. doi: 10.1002/ana.22527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaaimi B, Edgley SA, Soteropoulos DS, Baker SN. Changes in descending motor pathway connectivity after corticospinal tract lesion in macaque monkey. Brain. 2012;135:2277–2289. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1 – Principal component analysis of gait kinematics. As described in the methods, 198 gait-related variables were derived from films of mice walking on a treadmill. These variables were compared among different training groups using principal component analysis. (A) Scree plot showing the contribution of each principal component to the total variance of the dataset. The first eight components, explaining 55% of the total variance, are highlighted in red. (B) Gait variables with absolute factor loading scores of >0.5 are shown for each component. (C) Three-dimensional scatter plot of mean factor loading scores (for components 6, 7, and 8) in individual mice of each training group. No consistent differences were found between mice of each training group. Full kinematic datasets and tables openly available upon request.

Supplementary Movie 1 – Video of a typical training session. In clockface coordinates, BS+CST platforms are at 12 and 2 o'clock; an NT area is at 4 o'clock; a CST platform is at 7 o'clock; and a BS platform is at 10 o'clock.