Abstract

A cue indicating when in time to listen can improve adults' tone detection thresholds, particularly for conditions that produce substantial informational masking. The purpose of this study was to determine if 5- to 13-yr-old children likewise benefit from a light cue indicating when in time to listen for a masked pure-tone signal. Each listener was tested in one of two continuous maskers: Broadband noise (low informational masking) or a random-frequency, two-tone masker (high informational masking). Using a single-interval method of constant stimuli, detection thresholds were measured for two temporal conditions: (1) Temporally-defined, with the listening interval defined by a light cue, and (2) temporally-uncertain, with no light cue. Thresholds estimated from psychometric functions fitted to the data indicated that children and adults benefited to the same degree from the visual cue. Across listeners, the average benefit of a defined listening interval was 1.8 dB in the broadband noise and 8.6 dB in the random-frequency, two-tone masker. Thus, the benefit of knowing when in time to listen was more robust for conditions believed to be dominated by informational masking. An unexpected finding of this study was that children's thresholds were comparable to adults' in the random-frequency, two-tone masker.

INTRODUCTION

This study examined the degree to which children's masked thresholds improve when they are provided with a visual cue indicating when in time to listen for a target signal. This work was motivated by multiple observations across laboratories that children are more susceptible to auditory masking than adults (e.g., Allen and Wightman, 1995; Elliott and Katz, 1980; Hall et al., 2005; Werner and Bargones, 1991). Child-adult differences in tone detection thresholds have been observed for Gaussian noise maskers (e.g., Elliott and Katz, 1980). Noise maskers are expected to primarily produce energetic masking, which is the result of overlapping excitation patterns in the peripheral auditory system (e.g., Fletcher, 1940). Compared to child-adult differences for tone detection in a noise masker, developmental effects are more pronounced and prolonged for maskers comprised of pure tones (e.g., Allen and Wightman, 1995; Leibold and Neff, 2007; Lutfi et al., 2003b; Oh et al., 2001; Wightman et al., 2003). Most of these developmental studies using tonal maskers have used the “simultaneous multi-tonal masker paradigm” introduced by Neff and Green (1987). In this paradigm, the listener's task is to detect a fixed-frequency, pure-tone signal presented simultaneously with a random-frequency, multi-tonal masker. Experimental controls are typically employed to reduce energetic masking. Thus, listeners' elevated thresholds in the multi-tonal maskers relative to detection in quiet appear to be the result of limited or ineffective central auditory processes, including those related to separating the signal from the masker and selectively attending to the signal. This phenomenon is often referred to as “informational masking” (reviewed by Kidd et al., 2007).

Substantial informational masking has been observed for both children and adults in the presence of random-frequency, multi-tonal maskers (e.g., Neff and Green, 1987; Oh et al., 2001). These masking effects tend to be pronounced during childhood, with child-adult differences as large as 50 dB (e.g., Oh et al., 2001). Reductions in informational masking with increasing age during childhood have also been reported in the literature (Leibold and Bonino, 2009; Leibold and Neff, 2007; Lutfi et al., 2003b; Wightman et al., 2003). For example, 8- to 10-yr-old children have better thresholds than 5- to 7-yr-old children for the detection of a tone in the presence of a random-frequency, multi-tonal masker (Leibold and Neff, 2007; Leibold and Bonino, 2009). Despite improvements in performance with increasing age during childhood, significant child-adult differences have been observed as late as adolescence for the detection of a pure-tone signal embedded in a random-frequency, multi-tonal masker (Lutfi et al., 2003b; Wightman et al., 2003).

Mounting evidence suggests that children's increased susceptibility to informational masking compared to adults' is a consequence of immature central auditory processes. Although the specific central auditory processes responsible for children's susceptibility to informational masking are not fully understood, immature sound source segregation and/or selective attention processes appear to be at least partly responsible for children's increased difficulties (reviewed by Leibold, 2012). These processes are discussed separately below; however, it is unlikely that they operate independently. Furthermore, it can be difficult to determine the distinct contributions of each process to children's immature performance on behavioral measures in the laboratory.

Sound source segregation is the perceptual process by which a listener parses a target from competing background sounds. Stimulus features that assist adults in performing sound source segregation include spatial separation between sound sources, asynchronous temporal onsets, incoherence of dynamic stimulus properties, and differences in sound quality or timbre (reviewed by Bregman, 1993). The provision of acoustic cues thought to assist listeners in forming distinct auditory streams often improves adults' tone detection thresholds in random-frequency, multi-tonal maskers (e.g., Kidd et al., 1994). However, results are mixed for children. For example, young school-aged children are adult-like in their ability to benefit from an asynchronous temporal onset of the signal and masker (Hall et al., 2005; Leibold and Neff, 2007), whereas even adolescent children do not effectively use a dichotic presentation of the signal and masker (e.g., Wightman et al., 2003).

Once a listener has successfully parsed the signal from the competing background sounds, he/she needs to be able to focus on the signal while disregarding the irrelevant sounds. This process is referred to as selective auditory attention. It has been argued that infants and children do not listen selectively in the frequency domain, consequently increasing their susceptibility to auditory masking (e.g., Werner and Bargones, 1991; Lutfi et al., 2003b). Monitoring a wide frequency range may also explain why infants and children are more susceptible than adults to masking produced by random-frequency, multi-tonal maskers. This idea was proposed by Lutfi et al. (2003b) as an explanation for the variability in detection thresholds, both within and across listener age groups, for a simultaneous random-frequency, multi-tonal masker paradigm.

One method for examining selective auditory attention is the probe-signal method (Greenberg and Larkin, 1968). In this method, the listener is often “set up” to listen for the primary signal during training. The primary signal, referred to as the “expected” signal, is then presented with a greater probability during testing. On a smaller proportion of trials during testing, the primary signal is replaced by a probe signal. Probe signals are referred to as the “unexpected” signals. Results from probe-signal studies of adults have been interpreted as indicating that sensitivity to target signals can be improved by forming expectations about features of the signal. These features include frequency (e.g., Dai et al., 1991; Greenberg and Larkin, 1968), timing (e.g., Werner et al., 2009), and duration (e.g., Dai and Wright, 1995).

Although the data are limited, developmental studies have used the probe-signal method to examine infants' abilities to form expectations in the frequency and temporal domains. Bargones and Werner (1994) measured infants' and adults' sensitivity to signals of expected and unexpected frequencies. Whereas adult data indicated better sensitivity for the expected frequency tone (e.g., Bargones and Werner, 1994; Dai et al., 1991), infants were equally sensitive to signals at expected and unexpected frequencies. In contrast to the evidence indicating unselective listening in the frequency domain, infants can form temporal expectancies under some conditions (Werner et al., 2009). Werner et al. (2009) measured infants' detection thresholds for a pure-tone signal in a continuous broadband noise. A brief increase in the masker level occurred before the signal presentation, and the delay between these two events was manipulated. Both infants and adults showed better sensitivity to the signal on trials using the primary (or expected) delay duration.

The present study evaluated whether children benefit from a visual cue indicating when in time to listen for a pure-tone signal embedded in either broadband noise or a random-frequency, two-tone masker. Previous studies indicate that adults are more sensitive to target signals presented at defined listening intervals compared to uncertain listening intervals (e.g., Egan et al., 1961; Watson and Nichols, 1976). In this paper, the benefit of the visual cue indicating when in time to listen, referred to as the effect of signal-temporal uncertainty, was operationally defined as the difference between listeners' thresholds in a temporally-defined listening interval condition compared to a temporally-uncertain listening interval condition. The effect of signal-temporal uncertainty appears to be relatively small (≤3 dB) for adults when the signal is embedded in a masker thought to primarily produce energetic masking (e.g., Egan et al., 1961; Green and Weber, 1980; Watson and Nichols, 1976). In contrast to these findings, recent studies indicate a larger effect of signal-temporal uncertainty with maskers thought to produce substantial informational masking (Best et al., 2007; Bonino and Leibold, 2008; Varghese et al., 2012; for exception see Richards et al., 2011). For example, Best et al. (2007) found that listeners could more accurately identify a target birdsong embedded in other birdsongs when they were provided with a cue indicating the time interval that contained the target. A follow-up study by Varghese et al. (2012) demonstrated that the benefit of this cue was larger when the masker was comprised of birdsongs (high informational masking) than when it was a spectrally-matched noise (low informational masking). Bonino and Leibold (2008) reported a similar pattern of results for tonal stimuli. Tone detection thresholds were measured for a 1000-Hz tone embedded in either a random-frequency, two-tone masker or broadband noise. Adults demonstrated an average improvement of 9 dB for the random-frequency, two-tone masker when the listening interval was defined compared to when the interval was uncertain. Similar to previous investigations, a small average improvement of 2 dB was observed for the broadband noise masker. These results suggest that the benefit of a cue indicating when in time to listen for the signal is larger for maskers expected to produce substantial informational masking compared to maskers that create little or no informational masking.

Based on results indicating that infants can form temporal expectations (Werner et al., 2009), it was hypothesized that informational masking would be reduced for school-aged children with the provision of a cue indicating when in time to listen for a target signal. Given children's increased susceptibility to informational masking relative to adults (e.g., Oh et al., 2001), one potential outcome considered was that children would benefit more from the cue than adults in the random-frequency, two-tone masker. However, an alternative outcome was that children would show little or no benefit from the provision of the visual cue due to immature selective auditory attention or child-adult differences in the ability to integrate the auditory and visual stimuli.

METHODS

Listeners

A total of 43 children and 19 adults completed this study. All listeners had thresholds in quiet of ≤20 dB hearing level (HL) bilaterally for octave frequencies from 0.25 to 8 kHz (ANSI, 2010). The sole exception was a 7.7-yr-old in the random-frequency, two-tone condition, who had two thresholds of 25 dB HL in the non-test ear. Listeners had no known history of chronic ear disease.

Listeners were tested in either broadband noise or in a random-frequency, two-tone masker. A single group of children was tested in the broadband noise: 5- to 13-yr-olds (n = 8), with an average age of 9.71 yrs [standard deviation (SD) = 2.66 yrs]. A total of 35 children completed testing in the random-frequency, two-tone masker. These children were recruited from three age groups: 5- to 7-yr-olds (n = 11), 8- to 10-yr-olds (n = 13), and 11- to 13-yr-olds (n = 11). The average age was 6.79 yrs (SD = 0.83 yrs) for the 5- to 7-yr-old group, 9.44 yrs (SD = 0.94 yrs) for the 8- to 10-yr-old group, and 12.56 yrs (SD = 0.79 yrs) for the 11- to 13-yr-old group. Two groups of adults were tested. Nine adults were tested in the broadband noise masker (19 to 27 yrs; mean = 22.97 yrs; SD = 3.00 yrs), and 10 adults were tested in the random-frequency, two-tone masker (20 to 34 yrs; mean = 26.68 yrs; SD = 6.2 yrs).

An additional nine listeners did not complete testing: Three for the broadband noise masker and six for the random-frequency, two-tone masker. Two children (6.7 and 7.3 yrs) were unable to complete training. The testing session was terminated early for two children (6.3 and 7.3 yrs) because of a consistently high false alarm rate (>75%). Five listeners (7.3, 8.1, 11.5, 12.2, and 31.4 yrs) withdrew from the study prior to completion.

Stimuli

Detection thresholds were estimated for a 1000-Hz pure-tone that was 120-ms in duration, including 5-ms cos2 onset/offset ramps. The signal was embedded in a masker train composed of bursts of either broadband noise (300 to 3000 Hz) or a random-frequency, two-tone complex. Frequency components of the two-tone masker were independently selected on each 120-ms burst. One component was drawn at random from a uniform distribution with a range of 300 to 920 Hz, and the other component was drawn from a uniform distribution of 1080 to 3000 Hz. A protected region of 920 to 1080 Hz was used for the random-frequency, two-tone masker. This protected region was included to reduce the contribution of energy-based masking. Unlike the random-frequency, two-tone masker, there was no protected region for the broadband noise masker. For both masker types, an individual masker burst was 120 ms, including 5-ms cos2 onset/offset ramps. During the plateaus of each masker burst, the overall level was 50 dB sound pressure level (SPL) (47 dB/component for the two-tone masker). The train of masker bursts was presented continuously throughout each block of trials, with no temporal overlap between successive bursts. The 1000-Hz signal, when present, was gated simultaneously with a single burst of the masker.

Stimuli were generated at a 25-kHz sampling rate. The signal and masker were attenuated digitally, played out of a real-time processor (TDT, RP2), routed through separate programmable attenuators that were set to 0 (TDT, PA5), mixed (TDT, SM3), and passed through a headphone buffer with 3 dB of attenuation (TDT, HB7). Stimuli were presented to the listener's right ear through an insert earphone (Etymotic, ER1, Elk Grove Village, IL).

Estimating the amount of energetic masking

The contribution of energetic masking was estimated for both maskers using the excitation-based model of partial loudness (Moore et al., 1997). Recently, Leibold et al. (2010) used this model to examine the contribution of peripheral excitation to differences in observed threshold across different samples of fixed-frequency, four-tone maskers. For the present study, thresholds were computed for each masker sample using a criterion partial loudness of 8 phons (e.g., Buss, 2008). The predicted threshold for the broadband noise masker (300 to 3000 Hz) was 35.8 dB SPL. In order to compute the predicted thresholds for the random-frequency, two-tone masker, a set of 1000 two-tone complexes was generated using the procedures described above, and submitted to the model. These estimates were rank ordered, and the value associated with the 70.7 percentile across all 1000 samples was taken as the predicted threshold. This value was 24.0 dB SPL.

Conditions and procedure

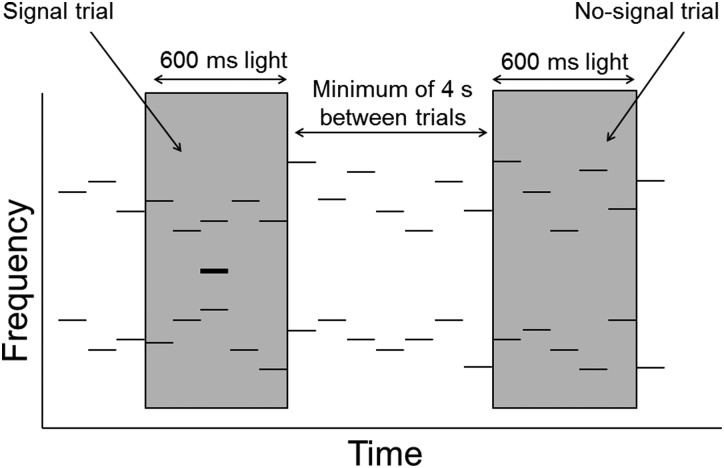

Listeners were tested individually in a double-walled, sound-attenuated booth (Industrial Acoustics, Bronx, NY). Adults were tested in a single, 2-h visit. Children were tested over two or three, 1-h test sessions with regular breaks. Listeners were assigned to complete testing in the presence of only one of the two maskers. For their assigned masker, listeners completed testing for two separate conditions: (1) Temporally-defined and (2) temporally-uncertain. In the temporally-defined condition, a light cue defined the listening interval. The light cue was the simultaneous illumination of five, 5 mm light emitting diode lights on a handheld unit measuring 3.5 × 6 in. Figure 1 provides a schematic of the temporally-defined, random-frequency, two-tone masker condition. The timing and duration of the light cues are shown by the gray boxes. A signal trial (bold dashed line) is shown in the left box, and a no-signal trial is shown in the right box. The onset of the 600-ms light cue was synchronous with the onset of the second masker burst following the initiation of each trial. The signal, when present, always occurred 240 ms after the activation of the light cue. The temporally-uncertain condition was identical to the temporally-defined condition, except that the listener was not provided a light cue. Thus, the listener was not aware of when the trial was initiated by the experimenter in the temporally-uncertain condition.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the temporally-defined, random-frequency, two-tone masker condition, in which the signal was embedded in the middle of a 600-ms light cue. The 1000-Hz pure-tone signal (bold, black dashed line) was presented in a continuous two-tone, random-frequency masker (black dashed line). The shaded gray boxes represent the light cues, with the left box being a signal trial and the right box being a no-signal trial. Each runwas 40 trials, with a minimum delay of 4 s between trials. The signal/no-signal probability was 0.5. In the temporally-uncertain condition (not shown), all other stimulus parameters were the same except the light cue was not provided.

Listeners sat inside the sound booth, and the experimenter was located in the adjacent control room. Listeners were instructed to raise their hand when they heard the signal. Prior to each temporally-defined run, listeners were reminded that the signal could only occur when the lights were on. Listeners were also informed that the signal/no-signal ratio was 0.5. These instructions were not provided for the temporally-uncertain runs. Listeners were simply instructed to raise their hand when they heard the signal and told that no light cue would be provided. The experimenter initiated each trial with a key press when the listener appeared to be “ready.” In the temporally-defined condition, trials were initiated only if the experimenter judged the listener to be looking at the handheld device. When a trial was initiated, listeners had 4 s to indicate that they heard a signal. A failure to respond during that observation window was coded as a “miss” if the signal was presented.

For each temporal condition, the testing protocol consisted of one training phase and two testing phases. During training and both phases of testing, the signal/no-signal probability was 0.5. The signal was presented at a clearly audible level in the training phase, based on results for adults reported by Bonino and Leibold (2008), and results for both children and adults from extensive pilot testing. The training period concluded when listeners were able to correctly identify 4/5 signals and 3/5 no-signals for a block of 10 training trials for each condition.

Because of the potential for large individual differences, within and across age groups (e.g., Neff and Dethlefs, 1995; Oh et al., 2001), adaptive thresholds were measured in phase 1 of testing in order to determine appropriate signal levels for each listener in phase 2 of testing. Adaptive thresholds were measured for both temporal conditions using a single-interval, one-up, one-down, adaptive procedure to estimate the 50% point on the psychometric function (Levitt, 1971). An initial step size of 4 dB was used, decreasing to 2 dB after the second reversal. Signal level was only changed on signal-present trials; responses from signal-absent trials were recorded solely to compute the false alarm rate. Testing concluded after six reversals, with threshold being the average signal level of the last four reversals. A minimum of three tracks were completed for each condition. Testing order was randomized across the six threshold tracks (3 tracks × 2 conditions). Additional tracks were run for listeners whose threshold estimates varied more than 5 dB across tracks. An additional track was run for one child in the broadband noise masker. Additional tracks were run for seven children and one adult in the random-frequency, two-tone masker. For six of these listeners, the three tracks with the closest agreement were used to determine the mean threshold. For the three remaining listeners, only the last two tracks were used because the initial threshold estimates differed from later estimates by ≥10 dB.

The average threshold across tracks was used to select the signal levels for phase 2 of testing. Based on this average threshold, signals were presented at five levels during phase 2 of testing. The method of constant stimuli with a single-interval, Yes/No procedure was used. A run consisted of 40 trials with a 0.5 a priori signal/no-signal probability. Each run contained 20 total signal trials (4 signal trials for each of the 5 signal levels) and 20 no-signal trials, presented in random order. The mid-point of the five signal levels was the average threshold corresponding to 50% correct signal detection from phase 1. Initially, the remaining four signal levels, relative to the mid-point, were +4, +2, −2, and −4 dB for the broadband masker and +8, +4, −4, and −8 dB for the random-frequency, two-tone masker. These values were selected based on extensive pilot data and the consistent observation in the literature that psychometric functions tend to be shallower for a random-frequency, multi-tonal masker than for a broadband noise masker (e.g., Lutfi et al., 2003a). Based on the listener's initial performance, the mid-point and/or level spacing were adjusted for subsequent runs. The mid-point was adjusted for approximately 60% of the functions for the broadband noise masker and 80% of the functions for the random-frequency, two-tone masker. In these cases, the midpoint was adjusted either because asymptotic performance was not observed at the maximum level (+4 dB for broadband noise; +8 dB for the two-tone masker), or because a hit rate of ≤20% was not observed at the minimum level (−4 dB for broadband noise; −8 dB for the two-tone masker). For the broadband noise condition, the spacing was reduced for only one function, whereas spacing was adjusted for approximately 20% of random-frequency, two-tone masker functions. In these cases, spacing was reduced to collect more data near the middle of the listener's psychometric function. Each listener completed a total of four runs for each temporal condition. The temporal condition was randomized across the eight runs, although it was held constant within a run. If time permitted, one additional run was completed for listeners judged to have variable performance by the experimenter based on a false alarm rate. An additional run was completed for nine children in one temporal condition each. For these listeners, the run with the highest false alarm rate was omitted from further analysis.

Procedure for fitting psychometric functions

Individual psychometric functions were fitted to listener data from 160 trials collected during phase 2 of testing for each temporal condition. Prior to fitting the data, individual scores were calculated for each signal level. The score is the percent correct score corrected for bias (e.g., Macmillan and Creelman, 2005). Fits were made using the procedure described by Dai (1995), modified to include the upper asymptote as a fitted parameter (Dai and Micheyl, 2011). This procedure is based on a chi-squared goodness-of-fit test, weighted by the number of observations at each level. Individual psychometric functions were assumed to have a form of

| (1) |

The variable λ relates to upper asymptote , and Φ is the cumulative Gaussian probability function. The first term represents the proportion of trials where the listener's performance was at chance due to inattention, whereas the second term reflects performance for the proportion of trials where the listener was attending to the signal. The detectability index was defined as

| (2) |

where x is signal strength, α is threshold, and β is psychometric function slope. Both α and β are free parameters, and α is the signal strength at = 1. Permissible parameter values were restricted for slope (0.05 ≤ β ≤ 3.0). The upper asymptote was fixed based on the upper range of λ values reported by Lutfi et al. (2003a): λ = 0.05 for functions in the broadband noise masker and λ = 0.1 for functions in the random-frequency, two-tone masker. Functions were considered to be well-fitted if R2 ≥ 0.5.

Estimating response bias

In the single-interval procedure used in this study, listeners were asked to indicate when they heard a signal, and trials were recorded as no responses when the listener did not respond within the allotted time. Previous findings indicate that adults tend to adopt a conservative (strict) response criterion for indicating that a signal is present in this type of paradigm (e.g., Marshall and Jesteadt, 1986). In order to examine age-related differences in response bias for different temporal and masker conditions in the present study, criterion estimates were calculated for individual listeners. Responses for all signal levels were pooled for each listener by temporal condition (temporally-defined or temporally-uncertain). The criterion was defined as (Macmillan and Creelman, 2005)

| (3) |

with and being the z-scores associated with the hit rate and false-alarm rate, respectively. For listeners who did not produce any false alarms, a value of 0.5 was used as the number of false alarm trials, resulting in a false alarm rate of 0.6%.1 An unbiased listener would have a criterion of 0. For a biased listener, a negative value indicates the listener is more liberal in his/her decision to indicate a signal is present, and a positive value indicates the listener is more conservative.

RESULTS

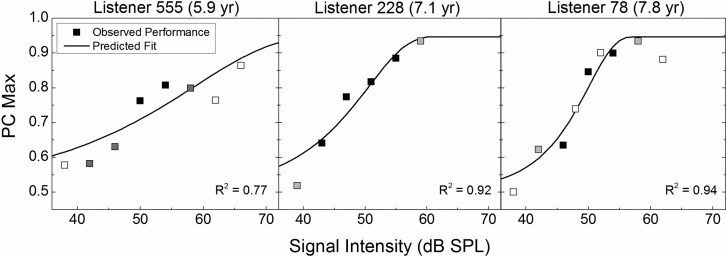

Mean estimates of threshold and criterion are provided in Table TABLE I.. Psychometric function slope was also estimated, but those values were omitted from the table due to uncertainty regarding upper asymptote.2 Data are grouped by masker type, then by listener age group and temporal condition. Median R2 values are also provided to indicate the goodness of fit. Examples of individual psychometric function fits are provided in Fig. 2. This figure includes data from three 5- to 7-yr-olds in the temporally-uncertain, random-frequency, two-tone masker condition. The observed data are indicated by the squares. The gray scale indicates the number of signal trials at each level, with white being the minimum (n = 4) and black being the maximum (n = 16) for these three listeners. The fitted functions are indicated by the solid black lines.

TABLE I.

Mean estimates of masked threshold (dB SPL) and response bias (c) are provided for the broadband noise masker (top) and the random-frequency, two-tone masker (bottom). For each masker, values for the temporally-defined and temporally-uncertain listening conditions are provided by the listener age group. The standard error is provided for each estimate in parentheses. The median R2 value is provided for each listener age group. The R2 value indicates the proportion of variance in the data accounted for by individuals' fitted functions. These values are from only the listeners who had fits associated with R2 ≥ 0.5 for both conditions.

| Temporally-defined | Temporally-uncertain | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masker | Age group | Threshold | R2 | Bias | Threshold | R2 | Bias |

| Broadband noise | 5–13 yrs | 39.03 (0.45) | 0.90 | 0.08 (0.01) | 40.95 (0.60) | 0.87 | 1.08 (0.07) |

| Adults | 38.15 (0.45) | 0.94 | 0.10 (0.01) | 39.91 (0.40) | 0.90 | 1.08 (0.07) | |

| Random, two-tone masker | 5–7 yrs | 43.12 (1.44) | 0.73 | 0.08 (0.01) | 50.14 (1.05) | 0.83 | 1.04 (0.08) |

| 8–10 yrs | 42.91 (2.04) | 0.70 | 0.05 (0.01) | 49.56 (1.69) | 0.92 | 0.80 (0.11) | |

| 11–13 yrs | 41.70 (2.55) | 0.76 | 0.06 (0.01) | 53.51 (1.79) | 0.86 | 0.90 (0.16) | |

| Adults | 40.94 (2.64) | 0.75 | 0.08 (0.01) | 51.22 (1.60) | 0.85 | 0.88 (0.11) | |

Figure 2.

Examples of three psychometric function fits in the random-frequency, two-tone masker are provided. All fits shown here are in the temporally-uncertain condition, and each panel shows data from a different listener from the 5- to 7-yr-old age group. Observed scores are represented by the squares, with the number of signal trials indicated by the gray scale intensity. For example, signal levels with only four signal trials are represented by white-filled squares and levels with 16 trials are black-filled squares. The solid black line represents the fitted function. The R2 values for each fit are provided.

Goodness of fit

Functions were considered to have acceptable fits if R2 ≥ 0.5. All listeners tested in the broadband noise masker met this R2 criterion in both the temporally-uncertain condition and the temporally-defined condition. Of the 45 listeners tested in the random-frequency, two-tone masker, 32 met this R2 criterion in both temporal conditions. Eleven children and two adults failed to achieve this criterion. Two listeners had fits of R2 < 0.5 for both temporal conditions. Of the remaining 11 functions with an R2 < 0.5 in only one temporal condition, 6 were in the temporally-defined condition and 5 were in the temporally-uncertain condition. Cases of poorly fitted data occurred for children in all three age groups: Three from the 5- to 7-yr-olds, three from the 8- to 10-yr-olds, and five from the 11- to 13-yr-olds. Further analyses, reported below, were restricted to data from the 32 listeners who had fits of R2 ≥ 0.5 in both temporal conditions in the random-frequency, two-tone masker.

Psychometric functions were also examined for non-monotonicity in the random-frequency, two-tone masker. It has been reported in the literature that listeners' performance can be worse than anticipated near a 0-dB signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for maskers expected to produce substantial informational masking (e.g., Brungart, 2001). Non-monotonic performance for these studies is thought to be the result of listeners using a level difference cue between the signal and the masker for levels both below and above 0 dB SNR. At a 0-dB SNR this cue is not available to the listener, exacerbating informational masking. For each listener, residuals were calculated by finding the difference between the predicted and observed scores. Individual listener's residuals were compiled as a function of signal level. Visual inspection of these data indicated that the mean and the spread of residuals were consistent as a function of signal level. Specifically, there was no evidence that thresholds were consistently underestimated at 0-dB SNR or overestimated at other SNRs in fits to data from the random-frequency, two-tone masker.

Threshold estimates and the effect of signal-temporal uncertainty

Broadband noise masker

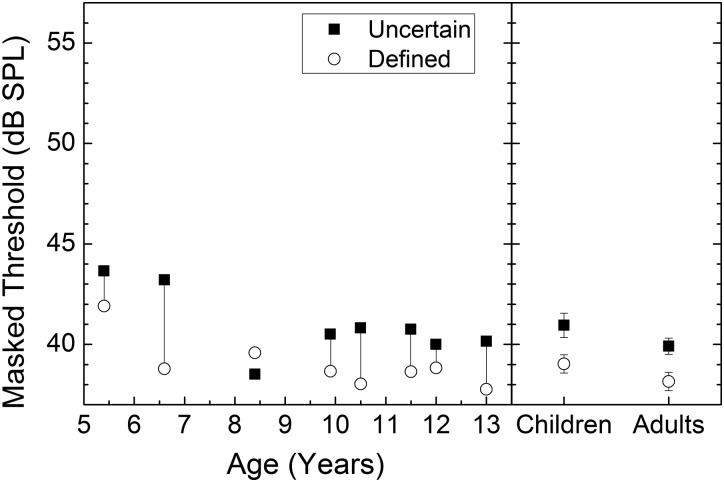

Figure 3 provides mean threshold estimates (±1 SE), based on a = 1, for the two age groups tested in the broadband noise masker. Individual data from the children are also shown. Thresholds are represented by filled squares for the temporally-uncertain condition, and by open circles for the temporally-defined condition. The black vertical lines indicate the effect of signal-temporal uncertainty for individual children. This line is absent for one child (8.4-yr-old) who did not benefit from the provision of the light cue.

Figure 3.

Mean (±1 SE) and individual masked thresholds are provided in the broadband noise masker. Filled squares indicate the temporally-uncertain condition, and open circles indicate the temporally-defined condition. Individual data are provided for the child listeners as a function of age in the left panel. For each child's data points, a vertical line indicates the amount of benefit for the cue. The absence of a vertical line indicates no benefit with a defined listening interval.

a. Group differences. In the temporally-uncertain, broadband noise condition, mean thresholds were 40.9 dB SPL for children and 39.9 dB SPL for adults. There was a trend for thresholds to be slightly lower in the temporally-defined than the temporally-uncertain condition for both age groups. The mean threshold in the temporally-defined condition was 39.0 dB SPL for children and 38.1 dB SPL for adults. In order to examine the effect of signal-temporal uncertainty, threshold for the temporally-defined condition was subtracted from threshold for the temporally-uncertain condition for each listener. The average benefit of a defined listening interval in the broadband noise masker was 1.9 dB for children and 1.8 dB for adults.

A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) of threshold was performed to assess the statistical reliability of this benefit. This analysis included the within-subjects factor of Temporal Condition (temporally-defined, temporally-uncertain) and the between-subjects factor of Age Group (children, adults). The main effect of Temporal Condition was significant [F(1,15) = 36.52, p < 0.001], confirming that listeners' tone detection thresholds in broadband noise improved when they were provided a cue indicating when in time to listen. The main effect of Age Group [F(1,15) = 2.53, p = 0.13] was not significant, indicating similar masked thresholds for children and adults. The Temporal Condition × Age Group interaction [F(1,15) = 0.08, p = 0.78] was also not significant. The lack of a significant interaction indicates that thresholds improved by a similar amount for both age groups in broadband noise with the provision of a light cue indicating when in time to listen.

b. Individual differences. Across all child and adult listeners, the range of thresholds observed in the broadband noise masker was relatively small (about 5 dB) for both temporal conditions. Thresholds ranged from 38.4 to 43.6 dB SPL for the temporally-uncertain condition and from 36.1 to 41.9 dB SPL for the temporally-defined condition. Listeners' thresholds were elevated compared to the predicted threshold of 35.8 dB SPL, from the excitation-based model of partial loudness (Moore et al., 1997) using an 8-phon criterion. The observed mean threshold for all listeners was higher than the predicted threshold by 4.6 dB in the temporally-uncertain condition and 2.8 dB in the temporally-defined condition. This discrepancy could be related to the brevity of the signal used here. Consistent with the mean data, 14 of the 17 listeners showed a small (<3 dB) benefit for the cue. The greatest benefit was 4.4 dB, which was measured in a 6.6-yr-old. One listener's calculated effect of signal-temporal uncertainty was less than 0 dB (−1.1 dB for an 8.4-yr-old).

Random-frequency, two-tone masker

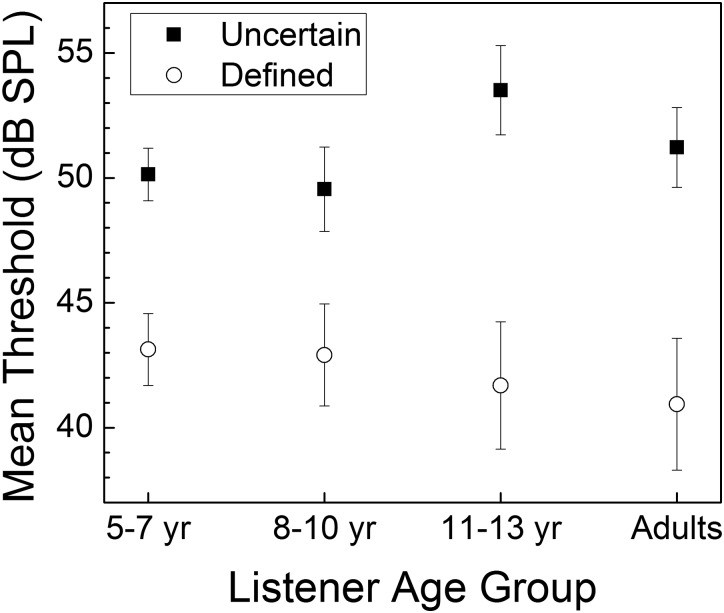

a. Group differences. Figure 4 shows mean estimates of masked threshold (±1 SE) for the four listener age groups tested in the random-frequency, two-tone masker. Thresholds are represented by filled squares for the temporally-uncertain condition, and by open circles for the temporally-defined condition. In the temporally-uncertain condition, mean thresholds were 50.1 dB SPL for 5- to 7-yr-olds, 49.5 dB SPL for 8- to 10-yr-olds, 53.5 dB SPL for 11- to 13-yr-olds, and 51.2 dB SPL for adults. Thresholds for all four age groups were lower in the temporally-defined condition compared to the temporally-uncertain condition. Mean thresholds in the temporally-defined condition were 43.1 dB SPL for 5-to 7-yr-olds, 42.9 dB SPL for 8- to 10-yr-olds, 41.7 dB SPL for 11- to 13-yr-olds, and 40.9 dB SPL for adults. The average benefit of a defined listening interval in the random-frequency, two-tone masker was 7.0 dB for 5- to 7-yr-olds, 6.6 dB for 8- to 10-yr-olds, 11.8 dB for 11- to 13-yr-olds, and 10.3 dB for adults.

Figure 4.

Mean masked threshold estimates (±1 SE) are provided as a function of listener age group for the temporally-uncertain (filled square) and the temporally-defined (open circle) conditions in the random-frequency, two-tone masker.

A repeated measures ANOVA of threshold was performed to assess developmental effects for susceptibility to masking and signal-temporal uncertainty with the random-frequency, two-tone masker. This analysis included the within-subjects factor of Temporal Condition (temporally-defined, temporally-uncertain) and the between-subjects factor of Age Group (5- to 7-yr-olds, 8- to 10-yr-olds, 11- to 13-yr-olds, and adults). The main effect of Temporal Condition was significant [F(1,28) = 106.31, p < 0.001]. This result confirms that listeners benefited from the visual cue in the random-frequency, two-tone masker. An unexpected result was that the main effect of Age Group [F(3,28) = 0.13, p = 0.94] was not significant, indicating similar thresholds across age in the random-frequency, two-tone masker. The Temporal Condition × Age Group interaction [F(3,28) = 2.05, p = 0.13] was also not significant, indicating that the effect of signal-temporal uncertainty was similar across age.

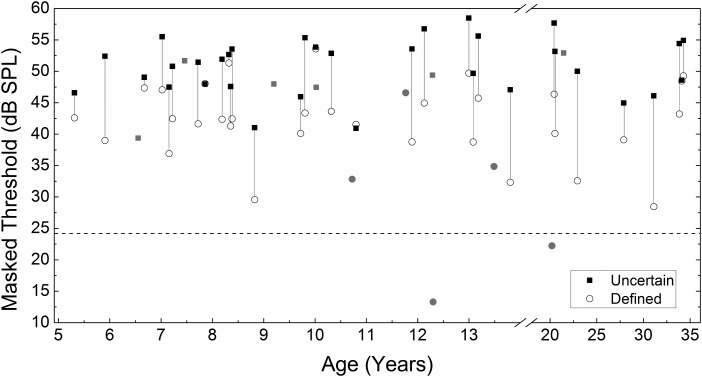

b. Individual differences. Consistent with other studies of informational masking involving both children and adults (e.g., Lutfi et al., 2003a; Oh et al., 2001), there was considerable between-listener variability for thresholds in the random-frequency, two-tone masker. In Fig. 5, individual thresholds are plotted as a function of age for the temporally-uncertain (filled squares) and the temporally-defined (open circles) conditions. The black vertical lines indicate the effect of signal-temporal uncertainty for each listener. The gray symbols indicate results for the 11 listeners who had fits of R2 ≥ 0.5 in only one of the two conditions. The dashed horizontal line indicates the threshold estimate of 24.0 dB SPL predicted by the excitation-based model of partial loudness (Moore et al., 1997) using an 8-phon criterion.

Figure 5.

Individual masked threshold estimate in the random-frequency, two-tone masker are shown as a function of listener age. Filled squares indicate the temporally-uncertain condition, and open circles indicate the temporally-defined condition. The vertical line between each individual's data points indicates the amount of benefit for the cue. The absence of a vertical line indicates no benefit with a defined listening interval or missing data due to failure to meet the R2 criterion. Data from listeners who were excluded from data analysis because of a poorly fitted function (R2 < 0.5) are represented by the gray symbols. For these listeners, estimates from just their well-fitted functions are shown. The horizontal dashed line provides the predicted threshold from the excitation-based model of partial loudness (Moore et al., 1997) using an 8-phon criterion.

For listeners with fits of R2 ≥ 0.5 in both conditions, shown in black, masked thresholds in the temporally-uncertain condition ranged from 40.9 (10.8-yr-old) to 58.5 dB SPL (12.9-yr-old). Masked thresholds in the temporally-defined condition ranged from 28.5 (31.1-yr-old) to 53.6 dB SPL (10.0-yr-old). All of these listeners had threshold estimates that exceeded the threshold predicted using the excitation-based model of partial loudness (Moore et al., 1997), consistent with the idea that this masker produced substantial informational masking in both temporal conditions. Despite large between-subjects variability in susceptibility to masking, nearly all listeners benefited from the listening interval being defined in time. The average effect of signal-temporally uncertainty was 8.6 dB, with six listeners showing an effect of ≥13 dB. Six listeners showed less than a 3-dB effect of signal-temporal uncertainty.

One caveat to the analysis of the group data is that 13 listeners were excluded from the statistical analysis because of a poorly fitted psychometric function in at least one temporal condition. It is possible that these listeners performed differently than those with well-fitted functions for both temporal conditions. Recall that 11 of these listeners had fits associated with R2 ≥ 0.5 in one of the temporal condition. For these 11 listeners, 8 listeners had threshold estimates for the well-fitted function that were within two standard deviations of the range of performance obtained for listeners who had well-fitted functions for both conditions. The three outlier thresholds were lower than the mean data, and were from a 6.5-yr-old in the temporally-uncertain condition and two listeners (a 12.3- and a 20.1-yr-old) in the temporally-defined condition. However, there were two listeners (an 8.8- and a 31.1-yr-old), with fits of R2 ≥ 0.5 for both functions, who also had similarly low thresholds.

Effect of signal-temporal uncertainty for broadband noise vs the random-frequency masker

In order to test the hypothesis that the benefit of knowing when in time to listen would be larger in the random-frequency, two-tone masker than in broadband noise, a between-subjects analysis was performed on a subset of the data. For children, this analysis included all eight children tested in the broadband noise masker, as well as eight age-matched children (within ± 4 months) tested in the random-frequency, two-tone masker. For adults, this analysis included the first eight adults tested in the broadband noise masker and the eight adults who had well-fitted functions in the random-frequency, two-tone masker. The average effect of signal temporal uncertainty for this subset of listeners was 1.8 dB in the broadband noise masker and 9.1 dB in the random-frequency, two-tone masker. This data set violated the assumption of homogeneity of variance [F(1,30) = 23.98, p < 0.001]. Thus, a univariate ANOVA, with Welch's adjusted F ratio, was conducted to examine whether the effect of signal-temporal uncertainty differed across the two masker types. The statistical results confirmed that the effect of signal-temporal uncertainty was greater for listeners tested in the random-frequency, two-tone masker than for listeners tested in the broadband noise masker [Welch's F(1,16.47) = 25.69, p < 0.001].

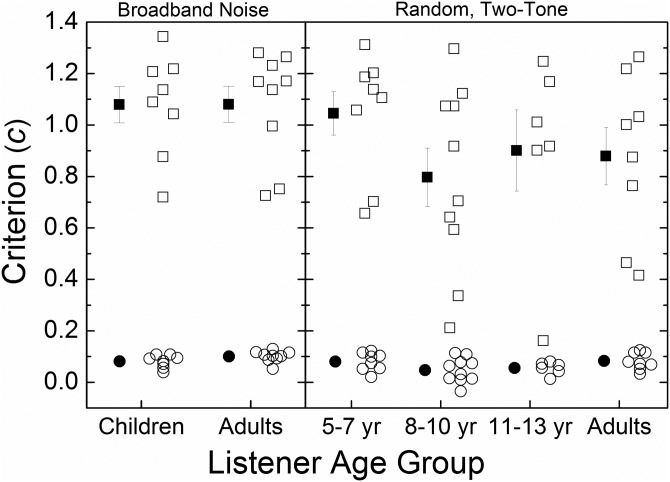

Response bias

Figure 6 provides individual estimates of criterion for the broadband noise masker (left panel) and random-frequency, two-tone masker (right panel). Open circles indicate estimates in the temporally-defined condition, and open squares represent estimates in the temporally-uncertain condition. Mean estimates are represented by filled symbols and are provided for each listener age group to the left of the individual data. Error bars indicate ±1 SE. In Fig. 6, error bars are not evident for the temporally-defined condition because the size of the symbol is larger than the error bars. For both masker types, listeners were more conservative in the temporally-uncertain listening condition than when the listening interval was defined. Furthermore, mean child and adult estimates of criterion appear similar within a temporal condition. Across all listener age groups tested in the broadband noise masker, the mean criterion was 1.08 (SE = 0.05; range: 0.72 to 1.34) for the temporally-uncertain condition and 0.09 (SE = 0.006; range: 0.04 to 0.13) for the temporally-defined condition. For the random-frequency two-tone masker, the mean criterion, across all listeners, was 0.90 (SE = 0.06; range: 0.16 to 1.31) for the temporally-uncertain condition and 0.07 (SE = 0.007; range: −0.03 to 0.12) for the temporally-defined condition.

Figure 6.

Individual and mean criterion estimates are provided for each temporal condition in the broadband noise masker (left panel) and the random-frequency, two-tone masker (right panel). For each masker, individual data are shown by the listener age group for the temporally-defined (open circles) and temporally-uncertain (open squares) conditions. Mean criterion estimates are indicated by the filled symbol to the left of the individual data; error bars are ±1 SE. In the temporally-defined condition, the error bars are not visible because they are smaller than the symbols.

Two separate repeated-measures ANOVAs were conducted to assess these trends, one for each masker type. For these analyses, the within-subjects variable was Temporal Condition (temporally-defined, temporally-uncertain), and the between-subjects variable was Age Group (broadband noise: Children, adults; random-frequency, two-tone masker: 5- to 7-yr-olds, 8- to 10-yr-olds, 11- to 13-yr-olds, and adults). Results from the ANOVA for the broadband noise masker indicated a significant main effect of Temporal Condition [F(1,15) = 446.27, p < 0.001]. However, neither the main effect of Age [F(1,15) = 0.04, p = 0.85] nor the Temporal Condition × Age Group interaction [F(1,15) = 0.04, p = 0.85] was significant. A similar pattern of results was observed for the random-frequency, two-tone masker. That is, a significant main effect of Temporal Condition [F(1,28) = 236.79, p < 0.001] was observed, but neither the main effect of Age Group [F(3,28) = 0.94, p = 0.44] nor the Temporal Condition × Age Group interaction was significant [F(3,28) = 0.80, p = 0.50]. Thus, both children and adults were more conservative when the listening interval was uncertain compared to when it was defined for both masker types.

DISCUSSION

This study measured tone detection in a broadband noise masker or a random-frequency, two-tone masker for 5- to 13-yr-old children and adults. The signal was presented at either a defined or an uncertain listening interval within a continuous train of masker bursts. The main hypothesis of this experiment was that children, as previously demonstrated for adults (e.g., Bonino and Leibold, 2008), would benefit from a visual cue indicating when in time to listen. Moreover, it was predicted that knowing when in time to listen would be particularly beneficial under conditions expected to produce substantial informational masking.

Susceptibility to informational masking

One qualification of the main hypothesis was that a substantially larger effect of signal-temporal uncertainty would be observed in the presence of the random-frequency, two-tone masker than in the broadband noise masker. Observed thresholds were consistently higher than thresholds predicted using the excitation model of partial loudness (Moore et al., 1997), providing evidence that the random-frequency, two-tone masker produced substantial informational masking for listeners of all ages. However, children's observed thresholds in the random-frequency, two-tone masker were similar to adults'. This result was unexpected. Previous studies have consistently reported increased susceptibility to informational masking for children compared to adults (e.g., Lutfi et al., 2003b; Oh et al., 2001), as well as age-related improvements during childhood (e.g., Leibold and Bonino, 2009; Leibold and Neff, 2007).

The similar masked thresholds observed across children and adults in the present study appear to reflect a relatively better performance for children compared to earlier developmental work. However, direct threshold comparisons between the present and previously published studies are difficult due to methodological differences between the various studies. The primary difference in methodology between the present and previous developmental studies that have examined tone detection in the presence of a random-frequency, two-tone masker is that this experiment used a continuous train of masker bursts. In contrast, previous studies have typically used either a single brief masker burst (Lutfi et al., 2003b; Oh et al., 2001; Wightman et al., 2003) or a brief train of masker bursts which are gated on and off during each interval (Bonino and Leibold, 2008; Hall et al., 2005). One exception is a comparison of informational masking in infants and adults reported by Leibold and Werner (2006). In that study, a continuous train of masker bursts was used, but a 300-ms silent delay was inserted after each masker burst. The relatively long silent interval between successive masker bursts may have resulted in a similar listening experience as when the masker is gated for each listening interval.

It is unclear what feature(s) of a continuous masker would result in equivalent thresholds for children and adults. One possible explanation is that a continuous masker may provide a weak streaming cue. Compared to a masker that is gated on and off during each interval, a continuous train of masker bursts may give the listener more opportunities to benefit from the temporal and spectral regularities of the masker than a gated masker, which is present only during listening intervals. That is, the masker might be perceived as an auditory stream when it is presented continuously during a run. Another possible explanation is that children may perform more poorly than adults when the masker is gated on and off during each interval because children are more prone to the distracting effects of onsets than adults. Specifically, the temporal onset of the masker may interfere with children's ability to listen in a frequency-selective manner.

Effect of signal-temporal uncertainty

Results indicate that children's and adults' thresholds for a 1000-Hz signal improved in the presence of both maskers with the provision of a visual cue indicating when in time to listen. Across all child and adult listeners tested in the broadband noise masker, the mean effect of signal-temporal uncertainty was 1.8 dB. This effect is consistent with data from previous studies showing a relatively small (≤3 dB) effect of signal-temporal uncertainty when testing is conducted in quiet or in steady-state noise (e.g., Egan et al., 1961; Green and Weber, 1980; Watson and Nichols, 1976). In comparison to the broadband noise masker, the benefit of defining the listening interval was substantially greater for the random-frequency, two-tone masker. The average effect of signal-temporal uncertainty was 8.6 dB across all listeners, with group average thresholds ranging from 6.6 to 11.8 dB across the four age groups. The observation of a significantly larger benefit for the random-frequency, two-tone masker compared to the broadband noise masker supports the idea that the effect of signal-temporal uncertainty is greater for conditions that produce high, rather than low, informational masking.

The present findings are in general agreement with recent studies which have examined the extent to which adults benefit from knowing when to listen for conditions believed to produce substantial informational masking (Best et al., 2007; Bonino and Leibold, 2008; Varghese et al., 2012). Bonino and Leibold (2008) observed a larger effect in a random-frequency, two-tone masker than in a broadband noise for a single group of adult listeners. The average effect of signal-temporal uncertainty was 2 dB for broadband noise and 9 dB (range of 5 to 15 dB) for the random-frequency, two-tone masker. Bonino and Leibold (2008) used similar stimuli to the present study with two exceptions: (1) There was a temporal asynchrony between the onset of the signal and the masker burst,3 and (2) the listening interval was defined by having the listener manually initiate the trial. Thus, defining the listening interval either through a visual cue or allowing the listener to initiate the trial appears to result in a similar benefit of knowing when to listen for a 1000-Hz signal embedded in a random-frequency, two-tone masker. A similar pattern of results has also been reported for bird song stimuli (Best et al., 2007; Varghese et al., 2012). Varghese et al. (2012) asked listeners to detect a target bird song presented in either a chorus of novel bird songs or in a noise masker which had the same long-term average spectral characteristics. When the target and competing bird song chorus were perceived as originating from the same spatial location, listeners were better able to identify the target when a temporal light cue was provided. The temporal cue did not improve performance in the noise masker for the same spatial configuration. In contrast to these studies, Richards et al. (2011) reported that listeners did not benefit from a defined listening interval in a random-frequency, multi-tonal masker. Methodological differences may be responsible for the apparent discrepancy observed across the different studies. Richards et al. (2011) gated the masker to define the listening interval, whereas the present study and the other three published studies (Best et al., 2007; Bonino and Leibold, 2008; Varghese et al., 2012) provided non-auditory cues to define the listening interval.

Results from this study indicate that school-aged children, like adults, receive a substantial benefit from the provision of a visual cue indicating when in time to listen for a signal embedded in a masker expected to generate informational masking. The degree of benefit from the visual cue was similar across all four age groups tested. This finding does not support the prediction that children derive a greater benefit of the visual cue than adults, because of their increased susceptibility to informational masking. However, children may show a greater benefit than adults under different listening conditions that produce child-adult differences in informational masking.

Decision strategy

For both masker types, all listener groups showed a more conservative bias when the listening interval was temporally uncertain than when it was defined. For the temporally-uncertain condition, the average response bias across all listeners was 1.08 in broadband noise and 0.90 in the random-frequency, two-tone masker. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have reported conservative bias estimates for adults tested in the single-interval, observer-based paradigm in which the listening interval is not defined for the participant inside the booth (e.g., Leibold and Werner, 2006; Werner et al., 2009). Werner et al. (2009) reported that mean bias was 1.15 for a group of adults tested as controls for a study investigating infant tone detection in broadband noise. Of interest is that the school-aged children tested in the present study showed a conservative decision strategy similar to adults in the temporally-uncertain conditions. This finding is in contrast to data collected from infants in the observer-based paradigm which consistently indicate that infants show no response bias (e.g., Leibold and Werner, 2006; Werner et al., 2009). One explanation for why children and adults adopt a more conservative listening strategy is that they learn that signals occur infrequently and are unlikely to occur soon after another signal was detected.

In contrast to the temporally-uncertain condition, both children and adults appeared to adopt an unbiased decision strategy with the provision of the light cue. The average response bias across listeners in the temporally-defined condition was 0.09 in broadband noise and 0.07 in the random-frequency, two-tone masker. Werner et al. (2009) similarly observed that adults adopted a less strict criterion when the listening interval was defined by a level increment cue compared to a temporally-uncertain condition. One explanation for the apparent difference in response bias between the temporally-defined and temporally-uncertain conditions is that the listener adopted different criteria based on the instructions that were provided by the tester (e.g., Egan et al., 1959). If this were the case, the present results mean that both children and adults were able to adjust their decision strategy when they were provided the signal/no-signal ratio in the temporally-defined condition. In contrast, the listener was unaware of when a trial was initiated in the temporally-uncertain condition. Thus, it is unlikely that the listener would benefit from knowing the signal/no-signal ratio in the temporally-uncertain condition.

The apparent bias difference between the two temporal conditions, if left uncontrolled, has the potential to influence estimates of the benefit of indicating when in time to listen. The effect of bias on thresholds measured in quiet appears to be relatively small (e.g., Marshall and Jesteadt, 1986). For example, Marshall and Jesteadt (1986) compared adults' thresholds measured in quiet for the standard clinical procedure and for two psychophysical methods: A two-interval, forced-choice adaptive procedure and a Yes/No procedure with undefined observation intervals. Response bias had a minimal effect (1.2 dB) on threshold obtained with the Yes/No procedure, despite listeners being more conservative. However, the effect of bias may be larger for masked listening conditions. Further work is needed to understand the effect of bias on masked threshold in a Yes/No task or for a single-interval adaptive paradigm.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the current study revealed that masked thresholds can be improved for both children and adults with the provision of a visual cue indicating when in time to listen for the target signal. For both maskers, all age groups tested showed comparable improvement in threshold with the provision of the visual cue. However, the effect of signal-temporal uncertainty was larger for the random-frequency, two-tone masker than for the broadband noise masker. The average benefit across all listeners was 1.8 dB in the broadband noise masker and 8.6 dB in the random-frequency, two-tone masker. Thus, a cue indicating when in time to listen results in substantial release from informational masking and can be used effectively by at least 5 to 7 yrs of age.

A secondary goal of this study was to document age-related changes in susceptibility to masking across a wide age span of childhood for the random-frequency, two-tone masker. However, age-related changes in threshold were not observed for the random-frequency, two-tone masker condition. This was an unexpected finding and is inconsistent with previously published literature. Future research is needed to better understand the mechanism responsible for this observation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported from the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (F31DC010308 and R01DC011038). This article is based on work appearing in a doctoral thesis by A.Y.B. Portions of these results were also presented to the Acoustical Society of America Meeting in Seattle, WA in May 2011.

Footnotes

Of the 98 fitted psychometric functions in which listeners had an R2 ≥ 0.5 in both temporal conditions, there were 17 fits in which the total number of false alarms was zero. Of these functions, 6 were in the broadband noise masker and 11 were in the random-frequency, two-tone masker. The 0.6% false alarm rate was calculated by using the 0.5 correction divided by the number of no-signal trials (n = 80).

Most listeners had only a small number of signal levels which resulted in ≥90% scores, making it challenging to estimate the upper asymptote of the psychometric function. Thus, slope estimates should be interpreted with caution, because the assigned upper asymptote value likely affects the slope estimates (e.g., Wightman and Allen, 1992). No clear age-related trends for slope estimates were observed, but differences in slope estimates were observed between the two masker types. Specifically, psychometric functions tended to have a shallower slope for the random-frequency, two-tone masker than for the broadband noise masker. These trends are consistent with previous work (e.g., Lutfi et al., 2003a). There also appeared to be slope differences based on temporal condition, with shallower slopes observed for the temporally-defined compared to the temporally-uncertain condition for both maskers. This finding is not consistent with Bonino and Leibold (2008) in which no systematic differences were observed between the temporal conditions.

Due to programming errors in Bonino and Leibold (2008), the stimuli were not accurately described in that report. As described in the erratum (Bonino and Leibold, 2013), the signal was 125 ms, and the masker burst was 125 ms (including 5-ms linear onset/offset ramps). A 5-ms period of silence occurred after each burst of the continuous masker. The onset of the signal was not synchronized with the onset of a masker burst. Instead, signal onset was initiated 80 ms after the onset of a masker burst.

References

- Allen, P., and Wightman, F. L. (1995). “ Effects of signal and masker uncertainty on children's detection,” J. Speech. Hear. Res. 38, 503–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American National Standards Institute (2010). ANSI/ASA S3.6-2010 Specifications for audiometers (American National Standards Institute, New York: ). [Google Scholar]

- Bargones, J. Y., and Werner, L. A. (1994). “ Adults listen selectively; infants do not,” Psychol. Sci. 5, 170–174. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1994.tb00655.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Best, V., Ozmeral, E. J., and Shinn-Cunningham, B. G. (2007). “ Visually-guided attention enhances target identification in a complex auditory scene,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 8, 294–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonino, A. Y., and Leibold, L. J. (2008). “ The effect of signal-temporal uncertainty on detection in bursts of noise or a random-frequency complex,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 124, EL321–EL327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonino, A. Y., and Leibold, L. J. (2013). “ Erratum: ‘The effect of signal-temporal uncertainty on detection in bursts of noise or a random-frequency complex’ [J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 124(5), EL321–EL327 (2008)],” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 133, 587. 10.1121/1.4770262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bregman, A. S. (1993). “ Auditory scene analysis: Hearing in complex environments,” in Thinking in Sound: The Cognitive Psychology of Human Audition, edited by McAdams S. and Bigand E. (Oxford University Press, New York: ), Chap. 2, pp. 10–36. [Google Scholar]

- Brungart, D. S. (2001). “ Informational and energetic masking effects in the perception of two simultaneous talkers,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 109, 1101–1109. 10.1121/1.1345696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss, E. (2008). “ The effect of masker level uncertainty on intensity discrimination,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 123, 254–264. 10.1121/1.2812578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai, H. (1995). “ On measuring psychometric functions: A comparison of the constant-stimulus and adaptive up-down methods,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 98, 3135–3139. 10.1121/1.413802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai, H., and Micheyl, C. (2011). “ Psychometric functions for pure-tone frequency discrimination,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 130, 263–272. 10.1121/1.3598448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai, H., Scharf, B., and Buus, S. (1991). “ Effective attenuation of signals in noise under focused attention,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 89, 2837–2842. 10.1121/1.400721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai, H., and Wright, B. A. (1995). “ Detecting signals of unexpected or uncertain durations,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 98, 798–806. 10.1121/1.413572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan, J. P., Greenberg, G. Z., and Schulman, A. I. (1961). “ Interval of time uncertainty in auditory detection,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 33, 771–778. 10.1121/1.1908795 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Egan, J. P., Schulman, A. I., and Greenberg, G. Z. (1959). “ Operating characteristics determined by binary decisions and by ratings,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 31, 768–773. 10.1121/1.1907783 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, L. L., and Katz, D. R. (1980). “ Children's pure tone detection,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 67, 343–344. 10.1121/1.383746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, H. (1940). “ Auditory patterns,” Rev. Mod. Phys. 12, 47–65. 10.1103/RevModPhys.12.47 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green, D. M., and Weber, D. L. (1980). “ Detection of temporally uncertain signals,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 67, 1304–1311. 10.1121/1.384183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, G. Z., and Larkin, W. D. (1968). “ Frequency-response characteristic of auditory observers detecting signals of a single frequency in noise: The probe-signal method,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 44, 1513–1523. 10.1121/1.1911290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J. W., Buss, E., and Grose, J. H. (2005). “ Informational masking release in children and adults,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 118, 1605–1613. 10.1121/1.1992675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, G., Mason, C. R., Deliwala, P. S., Woods, W. S., and Colburn, H. S. (1994). “ Reducing informational masking by sound segregation.” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 95, 3475–3480. 10.1121/1.410023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, G., Mason, C. R., Richards, V. M., Gallun, F. J., and Durlach, N. I. (2007). “ Informational masking,” in Auditory Perception of Sound Sources, edited by Yost W. A., Popper A. N., and Fay R. R. (Springer, New York), Chap. 6, pp. 143–189. [Google Scholar]

- Leibold, L. J. (2012). “ Development of auditory scene analysis and auditory attention,” in Human Auditory Development, edited by Werner L. A., Fay R. R., and Popper A. N. (Springer, New York), Chap. 5, pp. 137–161. [Google Scholar]

- Leibold, L. J., and Bonino, A. Y. (2009). “ Release from information masking in children: Effect of multiple signal bursts,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 125, 2200–2208. 10.1121/1.3087435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibold, L. J., Hitchens, J. J., Buss, E., and Neff, D. L. (2010). “ Excitation-based and informational masking of a tonal signal in a four-tone masker,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 127, 2441–2450. 10.1121/1.3298588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibold, L. J., and Neff, D. L. (2007). “ Effects of masker-spectral variability and masker fringes in children and adults,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 121, 3666–3676. 10.1121/1.2723664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibold, L. J., and Werner, L. A. (2006). “ Effect of masker-frequency variability on the detection performance of infants and adults,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 119, 3960–3970. 10.1121/1.2200150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, H. (1971). “ Transformed up-down methods in psychoacoustics,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 49, 467–477. 10.1121/1.1912375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutfi, R. A., Kistler, D. J., Callahan, M. R., and Wightman, F. L. (2003a). “ Psychometric functions for informational masking,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 114, 3273–3282. 10.1121/1.1629303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutfi, R. A., Kistler, D. J., Oh, E. L., Wightman, F. L., and Callahan, M. R. (2003b). “ One factor underlies individual differences in auditory informational masking within and across age groups,” Percept. Psychophys. 65, 396–406. 10.3758/BF03194571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan, N. A., and Creelman, C. D. (2005). Detection Theory: A User's Guide, 2nd ed. (Psychology Press, New York: ), pp. 3–50. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, L., and Jesteadt, W. (1986). “ Comparison of pure-tone audibility thresholds obtained with audiological and two-interval forced-choice procedures,” J. Speech Hear. Res. 29, 82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, B. C., Glasberg, B. R., and Baer, T. (1997). “ A model for the prediction of thresholds, loudness and partial loudness,” J. Audio Eng. Soc. 45, 224–240. [Google Scholar]

- Neff, D. L., and Dethlefs, T. M. (1995). “ Individual differences in simultaneous masking with random-frequency, multicomponent maskers,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 98, 125–134. 10.1121/1.413748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff, D. L., and Green, D. M. (1987). “ Masking produced by spectral uncertainty with multicomponent maskers,” Percept. Psychophys. 41, 409–415. 10.3758/BF03203033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, E. L., Wightman, F. L., and Lutfi, R. A. (2001). “ Children's detection of pure-tone signals with random multitone maskers,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 109, 2888–2895. 10.1121/1.1371764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards, V. M., Shub, D. E., and Carreira, E. M. (2011). “ The role of masker fringes for the detection of coherent tone pips,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 130, 883–892. 10.1121/1.3613701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese, L. A., Ozmeral, E. J., Best, V., and Shinn-Cunningham, B. G. (2012). “ How visual cues for when to listen aid selective auditory attention,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 13, 359–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, C. S., and Nichols, T. L. (1976). “ Detectability of auditory signals presented without defined observation intervals,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 59, 655–668. 10.1121/1.380915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner, L. A., and Bargones, J. Y. (1991). “ Sources of auditory masking in infants: Distraction effects,” Percept. Psychophys. 50, 405–412. 10.3758/BF03205057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner, L. A., Parrish, H. K., and Holmer, N. M. (2009). “ Effects of temporal uncertainty and temporal expectancy on infants' auditory sensitivity,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 125, 1040–1049. 10.1121/1.3050254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman, F. L., and Allen, P. A. (1992). “ Individual differences in auditory capability among preschool children,” in Developmental Psychoacoustics, edited by Werner L. A. and Rubel E. W. (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC: ), Chap. 4, pp. 113–133. [Google Scholar]

- Wightman, F. L., Callahan, M. R., Lutfi, R. A., Kistler, D. J., and Oh, E. L. (2003). “ Children's detection of pure-tone signals: Informational masking with contralateral maskers,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 113, 3297–3305. 10.1121/1.1570443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]