Abstract

Objective

Foods that enhance satiety can reduce overconsumption, but the availability of large portions of energy-dense foods may counter their benefits. We tested the influence on meal energy intake of varying the energy density and portion size of food consumed after a preload shown to promote satiety.

Design and Methods

In a crossover design, 46 women were served lunch on six days. On four days they ate a compulsory salad (300 g, 0.33 kcal/g). Unlike previous studies, instead of varying the preload, the subsequent test meal of pasta was varied between standard and increased levels of both energy density (1.25 or 1.66 kcal/g) and portion size (450 or 600 g). On two control days a salad was not served.

Results

Following the salad, the energy density and portion size of the test meal independently affected meal energy intake (both p<0.02). Serving the higher-energy-dense pasta increased test meal intake by 153±19 kcal and serving the larger portion of pasta increased test meal intake by 40±16 kcal. Compared to having no salad, consuming the salad decreased test meal intake by 123±18 kcal.

Conclusions

The effect of satiety-enhancing foods can be influenced by the energy density and portion size of other foods at the meal.

Keywords: preload, test meal, portion size, energy density, satiety

INTRODUCTION

Addressing the problem of obesity requires dietary strategies to reduce energy intake in the face of opposing influences in the eating environment. One approach that could help curb overconsumption is to incorporate satiety-enhancing foods into meals (1). Studies show that eating a satiating food as a first course can decrease energy intake both at the main course and at the entire meal (2, 3). It is unclear, however, whether these effects can be overridden by the other foods served at the meal. The purpose of the current study was to investigate whether increasing the energy density and portion size of the main course at a meal would counteract the effects of a satiating first course.

The satiety value of a food is typically assessed by consuming it as a preload or compulsory first course at a meal and measuring the effect on ad libitum energy intake at the subsequent test meal or main course (4). Previous research has demonstrated the utility of this paradigm in identifying characteristics of preloads that affect satiety (4, 5), but little attention has been given to how attributes of the test meal influence satiety. An increase in either the energy density or portion size of a main course has been shown to result in greater ad libitum energy intake at a meal when no first course is served (6–11). Furthermore, simultaneous increases in both energy density and portion size lead to independent and additive increases in meal energy intake (6, 7). These findings suggest that the characteristics of the test meal could have substantial effects when assessing the satiating properties of a preload.

The present study explored how alterations in the energy density and portion size of the test meal affect energy intake after consumption of a salad preload that has been shown to enhance satiety (2, 12). In contrast to the typical method for assessing satiety, we served an unvaried preload and varied the properties of the subsequent test meal. It was hypothesized that after consumption of a satiating preload, increases in the energy density and portion size of the following test meal would independently influence energy intake at the test meal. This study also included two control conditions in which no preload was provided, in order to examine whether consumption of the preload influenced overall energy intake at the meal. It was hypothesized that compared to having no preload, consumption of a satiating preload would reduce energy intake at both the test meal and the total lunch (preload plus test meal).

METHODS AND PROCEDURES

Subjects

Women aged 20 to 45 years were recruited through advertisements in campus newspapers, flyers, and electronic newsletters. Respondents were eligible if they had no food restrictions, were not pregnant or breastfeeding, were not dieting, were not athletes in training, regularly ate three meals per day, were not taking medications affecting appetite, were willing to consume the study foods, and did not smoke. Potential subjects were excluded if they had a body mass index <18 or >40 kg/m2; a score ≥20 on the Eating Attitudes Test (13), or a score ≥44 on the Zung depression scale (14).

A power analysis estimated that a sample of 38 women would allow the detection of a 50 kcal difference in meal energy intake with >80% power at a significance level of 0.05. A total of 53 women began the study; however, three women were excluded for failure to follow the study protocol. Of the 50 women who finished the study, data of three women were excluded for eating the entire test meal on two or more occasions. The data of one additional woman was excluded for having highly variable daily intakes that had undue influence on the outcomes according to the procedure of Littell, et al. (15). For this subject, the restricted likelihood distance (a measure of overall influence) in the mixed linear model was > 2.1. Thus, the analyses included 46 women; their mean age was 25.4±0.8 y (range 20–44 y), their mean height was 1.63±0.01 m (range 1.51–1.76 m), and their mean weight was 62.5±1.5 kg (range 44.0–91.9 kg). Thirty-three subjects were normal-weight, 11 were overweight, and 2 were obese; the mean body mass index was 23.6±0.5 kg/m2 (range 18.6–33.5 kg/m2). Participants provided signed consent and were financially compensated for participation. Subjects were informed that the purpose of the study was to investigate eating behaviors at different meals. The Pennsylvania State University Office for Research Protections approved all aspects of the study.

Study design

This experiment used a crossover design with repeated measures within subjects. Once a week for six weeks, subjects came to the laboratory at lunchtime to eat a pasta test meal. At four meals the pasta was preceded by a compulsory salad preload and at two control meals no salad was served. The orders of the six experimental conditions were counterbalanced using Latin squares and were randomly assigned to participants. The pasta was varied between standard (100%) and increased (133%) levels of both energy density (ED; 1.25 or 1.66 kcal/g) and portion size (450 or 600 g); the composition of the test meals is shown in Table 1. The higher-ED version of the pasta was made by increasing the proportion of pasta, cheese, cream, and sauce and decreasing the proportion of puréed vegetables (broccoli, cauliflower, and tomato). In the two control meals, the pasta was served at the 100% and 133% levels of ED, but only the 133% level of portion size. The 100% portion of pasta was not served without a salad because of concerns that for some women this meal would provide an insufficient amount of food.

Table 1.

| 100% Energy density (1.25 kcal/g)

|

133% Energy density (1.66 kcal/g)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% Portion size (450 g) | 133% Portion size (600 g) | 100% Portion size (450 g) | 133% Portion size (600 g) | |

| Energy (kcal) | 563 | 750 | 747 | 996 |

| Carbohydrate (% energy) | 48.1 | 48.1 | 46.7 | 46.7 |

| Protein (% energy) | 18.1 | 18.1 | 17.4 | 17.4 |

| Fat (% energy) | 33.8 | 33.8 | 35.9 | 35.9 |

| Fiber (g) | 8.7 | 11.6 | 7.8 | 10.4 |

Each version of pasta was served at one of the four meals that included a salad preload. At the two control meals that did not include a salad preload the pasta was served at the 100% and 133% levels of ED, but only the 133% level of portion size.

Recipe information is available upon request to the corresponding author.

The unvaried preload at four meals was a low-energy-dense salad (300 g, 100 kcal, 0.33 kcal/g) consisting of lettuces, cucumber, tomatoes, carrots, fat-free Italian dressing, and parmesan cheese. Previous studies found this salad to enhance satiety (2, 12). Subjects were required to consume the entire salad within 18 minutes and were served the pasta 20 minutes after the salad was served. During the 20-minute interval at the two meals in which no preload was consumed, participants were provided with magazines to read that did not contain any references to food or body weight. One liter of water was served with the pasta and both were consumed ad libitum. All foods and beverages were weighed before and after meals. Energy and macronutrient intakes were calculated using information from a standard nutrient database (16) and food manufacturers.

Procedures

Participants were instructed to keep their food intake and activity level consistent on the day before each test day and to record this information to encourage compliance. In order to ensure subjects came to lunch at a consistent level of hunger and fullness, a standard breakfast of bagels and yogurt was served in the laboratory, which could be consumed as desired. Assessment showed that there were no significant differences in breakfast energy intake across conditions. Participants were asked to refrain from consuming any foods or beverages, other than water, between breakfast and lunch. Subjects came to the laboratory at scheduled meal times and were seated in individual cubicles.

Ratings of hunger, satiety, and food characteristics

Subjects used 100-mm visual analog scales (17) to rate their hunger and fullness before and after the pasta as well as before the salad, when served. The anchors for hunger were “not at all hungry” on the left and “extremely hungry” on the right, and the anchors were similar for fullness. Participants also used visual analog scales to rate characteristics of the pasta and salad. Upon being served each food, they took a bite and rated how pleasant the taste and texture were, how filling the serving of food would be, how the size of the serving compared to their usual portion, and how many calories were in the serving. For the taste and texture questions, the anchors were “not at all pleasant” on the left and “extremely pleasant” on the right. The anchors for the remaining questions were “not filling at all” on the left and “extremely filling” on the right, “a lot smaller” on the left and “a lot larger” on the right, and “no calories at all” on the left and “extremely high in calories” on the right, respectively.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using a mixed linear model with repeated measures (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). The fixed factors in the model were pasta ED, pasta portion size, and study week. The main model analyzed the four conditions that provided the unvaried salad preload in order to determine the effect of changes in the ED and portion size of the test meal on the assessment of satiety. In accordance with the preloading paradigm, this analysis investigated the outcome of energy intake at the test meal. A second model assessed the effects of including the salad preload by analyzing the pairs of conditions that differed in the presence of the preload but provided the same test meal (either large portion of standard ED or large portion of increased ED). This analysis examined whether the consumption of a preload influenced energy intake at the test meal as well as overall energy intake at lunch, that is, when the energy content of both the preload and test meal was considered.

The study outcomes were food and energy intakes at the test meal, food and energy intakes at the entire lunch (preload plus test meal), and participant ratings of hunger, fullness, and food characteristics. Ratings of hunger and fullness after the test meal were adjusted for ratings at the start of the meal. Analysis of covariance was used to determine whether subject characteristics influenced the relation between the experimental factors and lunch intake. Results are reported as mean ± SEM and were considered significant at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Effects of increases in the energy density and portion size of the test meal

Test meal intake

Assessment of test meal energy intake in the four meals that included the salad preload showed that increases in the ED and portion size of the pasta test meal had independent effects (both p<0.02; Table 2). Serving the pasta that was 33% higher in ED increased test meal energy intake by a mean of 153±19 kcal and serving the portion of pasta that was 33% larger increased test meal energy intake by 40±16 kcal. Together these changes increased test meal energy intake by 187±21 kcal. Thus, after consumption of the salad, energy intake at the test meal was significantly influenced by both the ED and portion size of the test meal.

Table 2.

Energy and food intakes (n=46)1

| Preload | Salad | Salad | None | Salad | Salad | None | P values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Test meal energy density | 1.25 kcal/g | 1.25 kcal/g | 1.25 kcal/g | 1.66 kcal/g | 1.66 kcal/g | 1.66 kcal/g | Effect of energy density of the test meal2 | Effect of portion size of the test meal3 | Effect of presence of the preload4 |

|

| |||||||||

| Test meal portion size | 450 g | 600 g | 600 g | 450 g | 600 g | 600 g | |||

| Test meal intake | |||||||||

| Energy (kcal) | 329 ± 18 | 351 ± 20 | 476 ± 16 | 457 ± 20 | 523 ± 22 | 649 ± 23 | <0.0001 | <0.02 | <0.0001 |

| Weight (g) | 263 ± 14 | 281 ± 16 | 381 ± 13 | 275 ± 12 | 315 ± 13 | 390 ± 14 | NS | <0.01 | <0.0001 |

| Total lunch intake5 | |||||||||

| Energy (kcal) | 429 ± 18 | 451 ± 20 | 476 ± 16 | 557 ± 20 | 623 ± 22 | 649 ± 23 | <0.0001 | <0.02 | NS |

| Weight (g) | 563 ± 14 | 581 ± 16 | 381 ± 13 | 575 ± 12 | 615 ± 13 | 390 ± 14 | NS | <0.01 | <0.0001 |

All values are means ± SEMs.

Significance of the independent effects of the pasta test meal energy density in the four meals that included the salad preload as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures. NS = not significant (p>0.05).

Significance of the independent effects of the pasta test portion size in the four meals that included the salad preload as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures. NS = not significant (p>0.05).

Significance of the independent effects of the presence of the salad preload in the conditions that included the same pasta test meal (600 g of either the 1.25 kcal/g version or the 1.66 kcal/g version), as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures. NS = not significant (p>0.05).

Total lunch intake includes the salad preload plus the pasta test meal.

Evaluation of the weight of food consumed in these four meals showed significant effects of the portion size (p<0.01) but not the ED of the pasta test meal (Table 2). Food intake at the test meal was a mean of 32±11 g greater when the portion of pasta was increased by 150 g. After the salad, an increase in the portion size of the test meal thus significantly affected the weight of food eaten at the test meal.

Total lunch intake

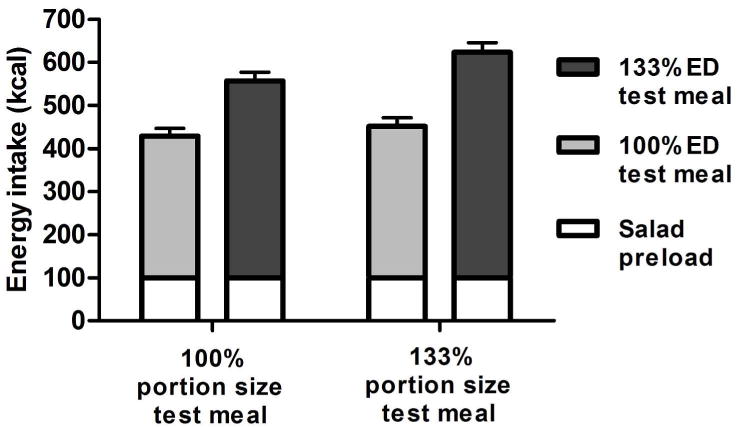

Since the salad was not varied in the four meals that included a preload, the effects of test meal ED and portion size on the entire lunch (preload + test meal) were similar to those on the test meal alone. Thus, both the ED and portion size of the test meal influenced total lunch energy intake (Figure 1), and only the portion size of the test meal influenced the total weight of food consumed.

FIGURE 1.

Mean (±SEM) energy intakes of 46 women who were served a test meal of pasta that was varied between 100% and 133% levels of both energy density (ED) and portion size, following a preload of salad that was not varied. Energy intakes at the test meal and at the entire lunch (salad + pasta) were independently increased by increases in the ED (p<0.0001) or portion size (p<0.02) of the pasta.

Effects of consumption of a preload prior to the test meal

Test meal intake

Consumption of the salad preload significantly influenced energy intake of the test meal (p<0.0001; Table 2), as shown by comparing the conditions that differed in the provision of the preload but included the same test meal (either large portion of standard ED or large portion of increased ED). Having the salad reduced intake of the pasta test meal by a mean of 123±18 kcal compared to not having the salad; this decrease in test meal energy intake demonstrated that the salad enhanced satiety.

Evaluation of these conditions also showed that consumption of the salad influenced the weight of food consumed at the test meal (p<0.0001; Table 2). Consuming the salad preload decreased the weight of food consumed by a mean of 86±13 g. Having a 300 g salad thus significantly influenced the weight of food consumed at the test meal.

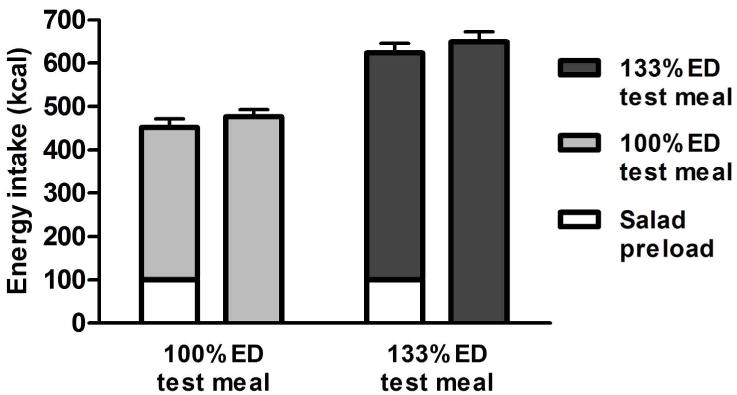

Total lunch intake

Across the conditions that differed in the provision of the salad preload but had the same test meal, consumption of the salad did not significantly influence total lunch energy intake (p=0.21; Figure 2). The 123 kcal reduction in energy from the pasta test meal combined with the 100 kcal addition from the salad preload resulted in no significant difference in total lunch energy intake compared to the control conditions (Table 2). Thus, participants compensated for the added energy from the salad by reducing intake of the test meal.

FIGURE 2.

Mean (±SEM) energy intakes of 46 women who were served lunch meals that varied in the provision of the salad preload and included the same pasta test meal (600 g of either the 1.25 kcal/g version or the 1.66 kcal/g version). Consumption of the salad reduced test meal energy intake (p<0.0001) but did not significantly affect total lunch (salad + pasta) energy intake.

The provision of the salad significantly influenced the total weight of food consumed at the meal (p<0.0001; Table 2). Consumption of the salad preload increased the total weight of food consumed at lunch by a mean of 214±13 g. As expected, the 300 g increase in weight from the salad significantly influenced the total weight of food eaten at the meal.

Ratings of hunger, satiety, and food characteristics

Upon arrival at the laboratory, subject ratings of hunger and fullness were not significantly different across conditions. At the end of the meal, hunger and fullness ratings depended on whether a preload was consumed. When the salad preload was eaten, ratings of hunger and fullness were not significantly influenced by the properties of the pasta test meal, despite substantial differences in food and energy intakes (Table 3). In contrast, consuming no salad resulted in higher hunger ratings after the pasta (p<0.04) but no significant difference in fullness ratings compared to having the salad.

Table 3.

Ratings of hunger and fullness (n=46)1

| Preload | Salad | Salad | None | Salad | Salad | None | P values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Test meal energy density | 1.25 kcal/g | 1.25 kcal/g | 1.25 kcal/g | 1.66 kcal/g | 1.66 kcal/g | 1.66 kcal/g | Effect of energy density of the test meal2 | Effect of portion size of the test meal3 | Effect of presence of the preload4 |

|

| |||||||||

| Test meal portion size | 450 g | 600 g | 600 g | 450 g | 600 g | 600 g | |||

| Hunger | |||||||||

| Before preload | 63 ± 3 | 64 ± 3 | 65 ± 3 | 64 ± 3 | 60 ± 3 | 59 ± 4 | NS | NS | NA |

| Before test meal | 38 ± 3 | 39 ±1 | 69 ± 3 | 41 ± 3 | 42 ± 3 | 69 ± 3 | NS | NS | <0.0001 |

| After test meal | 10 ± 2 | 9 ± 2 | 12 ± 2 | 7 ± 1 | 6 ± 1 | 9 ± 2 | NS | NS | <0.04 |

| Fullness | |||||||||

| Before preload | 27 ± 3 | 28 ± 3 | 25 ± 3 | 27 ± 3 | 29 ± 3 | 29 ± 4 | NS | NS | NA |

| Before test meal | 58 ± 2 | 58 ± 3 | 22 ± 3 | 57 ± 3 | 56 ± 2 | 22 ± 3 | NS | NS | <0.0001 |

| After test meal | 82 ± 2 | 85 ± 3 | 81 ± 2 | 86 ± 2 | 88 ± 2 | 84 ± 2 | NS | NS | NS |

All values are means ± SEMs.

Significance of the independent effects of the pasta test meal energy density in the four meals that included the salad preload as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures. NS = not significant (p>0.05).

Significance of the independent effects of the pasta test portion size in the four meals that included the salad preload as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures. NS = not significant (p>0.05).

Significance of the independent effects of the presence of the salad preload in the conditions that included the same pasta test meal (600 g of either the 1.25 kcal/g version or the 1.66 kcal/g version), as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures. NS = not significant (p>0.05); NA = not applicable.

Participant ratings of pasta characteristics are shown in Table 4. When the meal included no salad, the mean ratings for pleasantness of taste were not significantly different for the standard- and increased-ED versions of the pasta (71±3 versus 73±3 mm; p=0.69). Participants’ ratings of the amount of pasta they were served were significantly different for the two portions (p<0.02); the mean rating was 72±2 mm for the 100% portion and 81±2 mm for the 133% portion. There were no significant differences in ratings of the calorie content of the pasta even though there was a 33% difference in ED between the two versions. Ratings of characteristics of the salad, which was not varied, did not differ significantly across conditions (data not shown); the mean rating for pleasantness of taste was 75±1 mm.

Table 4.

Ratings of characteristics of the test meal (n=46)1

| Preload | Salad | Salad | None | Salad | Salad | None | P values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Test meal energy density | 1.25 kcal/g | 1.25 kcal/g | 1.25 kcal/g | 1.66 kcal/g | 1.66 kcal/g | 1.66 kcal/g | Effect of energy density of the test meal2 | Effect of portion size of the test meal3 | Effect of presence of the preload4 |

|

| |||||||||

| Test meal portion size | 450 g | 600 g | 600 g | 450 g | 600 g | 600 g | |||

| Taste | 55 ± 4 | 58 ± 3 | 71 ± 3 | 66 ± 3 | 64 ± 3 | 73 ± 3 | <0.01 | NS | <0.001 |

| Texture | 51 ± 4 | 52 ± 3a | 66 ± 3b | 61 ± 3 | 63 ± 3b | 66 ± 3b | <0.01 | NS | Interaction5 <0.01 |

| Filling | 88 ± 2 | 91 ± 2 | 88 ± 2 | 91 ± 2 | 92 ± 1 | 88 ± 2 | NS | NS | <0.02 |

| Size | 73 ± 2 | 81 ± 2 | 78 ± 2 | 72 ± 3 | 80 ± 2 | 81 ± 2 | NS | <0.001 | NS |

| Calories | 69 ± 2 | 70 ± 3 | 69 ± 3 | 70 ± 2 | 74 ± 2 | 71 ± 2 | NS | NS | NS |

All values are means ± SEMs. Ratings were assessed prior to consumption of the pasta test meal.

Significance of the independent effects of the pasta test meal energy density in the four meals that included the salad preload as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures. NS = not significant (p>0.05).

Significance of the independent effects of the pasta test portion size in the four meals that included the salad preload as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures. NS = not significant (p>0.05).

Significance of the independent effects of the presence of the salad preload in the conditions that included the same pasta test meal (600 g of either the 1.25 kcal/g version or the 1.66 kcal/g version), as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures. NS = not significant (p>0.05).

Significance of the interaction of the effects of the presence of a salad preload and the energy density of the pasta test meal in the conditions that included the same test meal (600 g of either the 1.25 kcal/g version or the 1.66 kcal/g version), as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures. Means in the same row with different superscript letters are significantly different.

Influence of subject characteristics

Analysis of covariance showed that the relationships between the experimental factors and the outcomes of energy and food intakes were not significantly influenced by participant body mass index, age, height, or weight.

DISCUSSION

The consumption of satiety-enhancing foods is one dietary strategy that could help people curb overconsumption to manage their weight. It is not clear, however, whether other foods that are readily available in the current obesogenic environment influence how satiety-enhancing foods affect energy intake. The present results showed that following a salad preload, increases in the energy density or portion size of the test meal led to independent increases in energy intake at the test meal as well as at the entire lunch (preload plus test meal). Compared to having no salad, consuming the salad decreased energy intake at the test meal and thus was shown to enhance satiety; having the salad did not, however, affect total energy intake at lunch. This study demonstrated that the effect of satiety-enhancing foods can be influenced by the ED and portion size of the other food at the meal.

Research on satiety has focused on the way that properties of a preload affect subsequent intake at an unvaried test meal (4, 5), but it is possible that the characteristics of the test meal itself could markedly affect satiety assessment. This concern has been raised previously (18, 19), yet the influence of the test meal has undergone little systematic investigation. A few studies have explored the effects on satiety of varying the variety (20–22), palatability (23, 24) or macronutrient content (25) of the test meal. What has not been investigated, however, is how the large portions of energy-dense foods that are characteristic of the present eating environment influence the effect of a food on satiety. The findings from our study show that after the satiety-enhancing preload, increasing either the ED or portion size of the pasta test meal increased energy intake at the test meal. Thus, the same preload can have very different effects on satiety (a range of 187 kcal in this study), depending only on the properties of the subsequent test meal. This suggests that the current paradigm for satiety assessment should be broadened to include consideration of characteristics of the test meal in addition to the preload.

It would also be advantageous to extend the assessment of satiety beyond effects on test meal intake to include whether satiety-enhancing foods decrease energy intake at the entire meal and thus help curb overconsumption. To evaluate this, intake needs to be compared at similar meals with and without the preload. This comparison was made in two previous studies, which found that a similar low-ED salad reduced total meal energy intake by 50 to 100 kcal (2, 12). In the present study, the reduction of 23 kcal at lunch was smaller than anticipated and did not reach statistical significance. The discrepancy in meal energy intake may have been due to differences in the subjects that were tested, even though all three studies tested women. Another possibility is the difference in the food that was served at the test meal. Although a pasta test meal was used in all three studies, the pasta in the current study differed in shape, form, ED, and portion size from the other test meals. Together, these differences in subject characteristics and the test meal could have influenced the compensatory response, since the present study found compensation for the salad energy, but not the expected reduction in lunch energy intake. These results indicate the importance of assessing intake at the entire meal and suggest the benefit of including a control condition when evaluating how satiety-enhancing foods moderate energy intake at a meal.

Inconsistencies in the identification of satiety-enhancing foods have been noted in the literature (5). The present finding that the assessment of satiety is markedly affected by the ED and portion size of the test meal, together with previous research showing that test meal properties such as variety, palatability, and macronutrient content can influence satiety (20–25), provides a possible reason for these inconsistencies. It could be useful in resolving these discrepancies if the satiety paradigm was further refined, taking into account the properties of the test meal. Food manufacturers should be aware that their satiety-enhancing products may have limited applicability if the products are not tested using meals that are comparable to those that consumers experience on a daily basis (26, 27). Although a recent study suggests that consumers are adept at appropriately interpreting satiety claims (28), consideration of the influence of the test meal on satiety assessment could also help address concerns that these claims could be misleading and lack utility (29–31).

An interesting finding from this study was that despite the large differences in energy intake across conditions, participant ratings of fullness were not affected by the ED or portion size of the test meal. In addition, participants rated the two pasta versions as similar in calorie content, suggesting that they did not notice the differences in pasta ED. This lack of sensitivity to the properties of foods that led to increased energy intake could hinder the efforts of individuals to control their energy consumption. The current study did not include dieters, however, and it is possible that individuals who are monitoring their intake may respond differently to alterations in ED and to consuming satiety-enhancing foods. Our results also showed that weight status did not influence the relationship between the properties of the test meal and energy intake, but it would be informative to test this design in a larger sample of obese individuals. Other factors that could have influenced energy intake in this study are differences in physical activity levels and the phase of the menstrual cycle. Since foods that enhance satiety are consumed by both men and women, additional research should determine whether men respond similarly to the consumption of satiety-enhancing foods when faced with energy-dense foods and large portions. Furthermore, it would be informative to determine how energy intake over the remainder of the day is affected by eating a satiating food at a meal that varies in ED and portion size.

Although the incorporation of satiety-enhancing foods into meals could be a beneficial strategy to help moderate energy intake for weight management, this study emphasizes the importance of the eating environment in which such foods are consumed. After consumption of the salad, overall energy intake at the meal was affected by both the ED and the portion size of the rest of the meal. Because of the strong environmental influences affecting energy intake, individuals may benefit from consuming multiple satiety-enhancing foods across the day in order to moderate energy intake. Additional investigation is needed not only to find foods that enhance satiety but also to determine how best to incorporate these foods into diets to effectively reduce energy intake (1, 32). While satiety-enhancing foods help to moderate energy intake, their effects can be influenced by the availability of large portions of energy-dense foods.

What is already known about this subject:

Consuming a satiety-enhancing preload can reduce test meal energy intake

The influence of the test meal on the satiety value of foods has been less well studied.

Energy intake can be affected by modifying the energy density and portion size of foods

What this study adds:

After a satiating preload, increases in the energy density and portion size of the test meal independently and additively increased energy intake

Variations in the energy density and portion size of the test meal affected the assessment of satiety

The effects of a satiety-enhancing food can be influenced by the other food consumed at the meal

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant DK059853. Competing interests: the authors have no competing interests.

We thank the staff and students in the Laboratory for the Study of Human Ingestive Behavior at The Pennsylvania State University.

Footnotes

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—RAW collected the data, RAW and LSR analyzed the data, and BJR had primary responsibility for final content. All authors were involved in designing the experiment and writing the manuscript and had approval of the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Rebello CJ, Liu AG, Greenway FL, Dhurandhar NV. Dietary strategies to increase satiety. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2013;69:105–182. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-410540-9.00003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. Salad and satiety: energy density and portion size of a first-course salad affect energy intake at lunch. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:1570–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flood JE, Rolls BJ. Soup preloads in a variety of forms reduce meal energy intake. Appetite. 2007;49:626–634. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blundell J, de Graaf C, Hulshof T, Jebb S, Livingstone B, Lluch A, et al. Appetite control: methodological aspects of the evaluation of foods. Obes Rev. 2010;11:251–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halford JCG, Harrold JA. Satiety-enhancing products for appetite control: science and regulation of functional foods for weight management. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2012;71:350–362. doi: 10.1017/S0029665112000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kral TV, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Combined effects of energy density and portion size on energy intake in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:962–968. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.6.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. Reductions in portion size and energy density of foods are additive and lead to sustained decreases in energy intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:11–17. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stubbs RJ, Johnstone AM, O’Reilly LM, Barton K, Reid C. The effect of covertly manipulating the energy density of mixed diets on ad libitum food intake in ‘pseudo free-living’ humans. Int J Obes. 1998;22:980–987. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly MT, Wallace JMW, Robson PJ, Rennie KL, Welch RW, Hannon-Fletcher MP, et al. Increased portion size leads to a sustained increase in energy intake over 4 d in normal-weight and overweight men and women. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:470–477. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508201960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rolls BJ, Morris EL, Roe LS. Portion size of food affects energy intake in normal-weight and overweight men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:1207–1213. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.6.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. Larger portion sizes lead to a sustained increase in energy intake over 2 days. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roe LS, Meengs JS, Rolls BJ. Salad and satiety: The effect of timing of salad consumption on meal energy intake. Appetite. 2012;58:242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE. The eating attitudes test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine. 1982;12:871–878. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700049163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zung WWK. Zung self-rating depression scale and depression status inventory. In: Sartorius N, Ban TA, editors. Assessment of Depression. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1986. pp. 221–231. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD, Schabenberger O. SAS for Mixed Models. 2. SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC: p. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Department of Agriculture; Agricultural Research Service. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 24;2011: Nutrient Data Laboratory Home Page. http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/ndl. Accessed 15 February 2012.

- 17.Flint A, Raben A, Blundell JE, Astrup A. Reproducibility, power and validity of visual analogue scales in assessment of appetite sensations in single test meal studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:38–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Livingstone MBE, Robson PJ, Welch RW, Burns AA, Burrows MS, McCormack C. Methodological issues in the assessment of satiety. Scand J Nutr. 2000;44:98–103. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stubbs RJ, Johnstone AM, O’Reilly LM, Poppitt SD. Methodological issues relating to the measurement of food, energy and nutrient intake in human laboratory-based studies. Proc Nutr Soc. 1998;57:357–72. doi: 10.1079/pns19980053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Long SJ, Griffiths EM, Rogers PJ, Morgan LM. Ad libitum food intake as a measure of satiety: comparison of a single food test meal and a mixed food buffet. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59:7A. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiessing KR, Xin L, McGill AT, Budgett SC, Strik CM, Poppitt SD. Sensitivity of ad libitum meals to detect changes in hunger. Restricted-item or multi-item test meals in the design of preload appetite studies. Appetite. 2012;58:1076–82. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norton GNM, Anderson AS, Hetherington MM. Volume and variety: relative effects on food intake. Physiol Behav. 2006;87:714–22. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeomans MR, Lee MD, Gray RW, French SJ. Effects of test-meal palatability on compensatory eating following disguised fat and carbohydrate preloads. Int J Obes. 2001;25:1215–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson TM, Gray RW, Yeomans MR, French SJ. Test-meal palatability alters the effects of intragastric fat but not carbohydrate preloads on intake and appetite in healthy volunteers. Physiol Behav. 2005;84:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawton CL, Burley VJ, Wales JK, Blundell JE. Dietary fat and appetite control in obese subjects: weak effects on satiation and satiety. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1993;17:409–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allirot X, Saulais L, Disse E, Nazare JA, Cazal C, Laville M. Integrating behavioral measurements in physiological approaches of satiety. Food Qual Prefer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2011.05.005.

- 27.Smeets PAM, van der Laan LN. Satiety. Not the problem, nor a solution. Comment on ‘Satiety. No way to slim’. Appetite. 2011;57:772–73. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bilman EM, van Kleef E, Mela DJ, Hulshof T, van Trijp HCM. Consumer understanding, interpretation and perceived levels of personal responsibility in relation to satiety-related claims. Appetite. 2012;59:912–20. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Booth DA, Nouwen A. Satiety. No way to slim. Appetite. 2010;55:718–21. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bellisle F, Tremblay A. Satiety and body weight control. Promise and compromise. Comment on ‘Satiety. No way to slim’ Appetite. 2011;47:769–71. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Booth DA, Nouwen A. Weight is controlled by eating patterns, not by foods or drugs. Reply to comments on “Satiety. No way to slim”. Appetite. 2011;57:784–90. [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Graaf C. Trustworthy satiety claims are good for science and society. Comment on ‘Satiety. No way to slim.’. Appetite. 2011;57:778–83. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.05.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]