Abstract

Chemotactic cells, including neutrophils and Dictyostelium discoideum, orient and move directionally in very shallow chemical gradients. As cells polarize, distinct structural and signaling components become spatially constrained to the leading edge or rear of the cell. It has been suggested that complex feedback loops that function downstream of receptor signaling integrate activating and inhibiting pathways to establish cell polarity within such gradients. Much effort has focused on defining activating pathways, whereas inhibitory networks have remained largely unexplored. We have identified a novel signaling function in Dictyostelium involving a Gα subunit (Gα9) that antagonizes broad chemotactic response. Mechanistically, Gα9 functions rapidly following receptor stimulation to negatively regulate PI3K/PTEN, adenylyl cyclase, and guanylyl cyclase pathways. The coordinated activation of these pathways is required to establish the asymmetric mobilization of actin and myosin that typifies polarity and ultimately directs chemotaxis. Most dramatically, cells lacking Gα9 have extended PI(3,4,5)P3, cAMP, and cGMP responses and are hyperpolarized. In contrast, cells expressing constitutively activated Gα9 exhibit a reciprocal phenotype. Their second message pathways are attenuated, and they have lost the ability to suppress lateral pseudopod formation. Potentially, functionally similar Gα-mediated inhibitory signaling may exist in other eukaryotic cells to regulate chemoattractant response.

Keywords: cAMP; cGMP; PI(3,4,5)P3; actin; myosin; Dictyostelium

Directed cell movement toward a chemoattractant source is required for a variety of complex cellular processes, including tissue formation, wound healing, metastasis, and pathogen capture. In general, the molecular mechanisms that govern chemotaxis are conserved among the eukarya. In numerous systems, the extracellular chemoattractant signal is perceived by specific seven-transmembrane (7-TM), G protein-coupled receptors, and in response, cells polarize and move toward the signal. A dominant anterior pseudopod is produced by rapid polymerization of actin at the leading edge in the direction of the highest concentration of chemoattractant, whereas myosin II is reorganized at the rear of the cell for retraction and at the sides to provide cortical tension (Bourne and Weiner 2002; Devreotes and Janetopoulos 2003; Merlot and Firtel 2003); this latter mechanism prevents spurious lateral pseudopod formation, and thereby enhances uniform directional movement toward the chemoattractant gradient source. Ultimately, chemotaxis is driven by localized changes in the polarized actin/myosin cytoskeleton.

Dictyostelium discoideum has become a paradigm for the study of chemoattractant response. Many regulatory components for chemotactic movement are shared by Dictyostelium, neutrophils, and other migrating cells (Devreotes and Janetopoulos 2003; Merlot and Firtel 2003). Specifically, starvation induces a developmental program in Dictyostelium that is dependent upon chemotaxis. Following nutrient deprivation, subsets of cells establish chemoattractant-signaling centers that emit cAMP pulse waves at regular intervals. Proximate cells perceive the extracellular cAMP signal through the cell-surface, 7-TM cAMP receptor CAR1, and respond by polarizing and chemotaxing inwardly toward the cAMP-signaling center and by producing and secreting additional cAMP (Tomchik and Devreotes 1981; Firtel and Chung 2000; Devreotes and Janetopoulos 2003; Merlot and Firtel 2003). The cAMP signal is relayed among neighboring cells and propagates outwardly to recruit more cells to the signaling center. A key component of unidirectional movement is receptor adaptation to the cAMP signal; extracellular cAMP is degraded by a secreted phosphodiesterase, and cells become resensitized (de-adapted) and reresponsive to the next wave of cAMP propagated from the signaling center. The oscillation cycle for adaptation/deadaptation creates a positive, outwardly moving cAMP concentration gradient that directs groups of cells to coalesce inwardly at signaling centers. These multicellular aggregates are the precursor structures for terminal differentiation and morphogenesis.

Chemoattractant stimulation in Dictyostelium regulates several effector pathways that are downstream of CAR1 and its heterotrimeric partner Gα2βγ (Devreotes and Janetopoulos 2003; Merlot and Firtel 2003). These include mobilization/activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), translocation of specific pleckstrin homology (PH) domain proteins to the plasma membrane, activation of second messenger generating enzymes guanylyl (GC), and adenylyl cyclases (AC), actin polymerization, and myosin II assembly. Once activated, all of these pathways rapidly adapt to a nonfluctuating or a saturating cAMP stimulus.

Most chemotaxing cells are exquisitely sensitive to changes in chemoattractant concentration and have the ability to discern signal gradients that differ by <2% across the length of the cell (Devreotes and Janetopoulos 2003; Merlot and Firtel 2003). Recent evidence supports a model in which dynamic changes in the localization and activity of specific components downstream of chemoattractant receptors regulate actin polymerization and myosin II assembly. It is still not understood how shallow extracellular chemoattractant gradients are transduced into highly polarized intracellular responses. Gradient sensing is not attributed to a simple localized activating response by the chemoattractant receptors or their coupled heterotrimeric G protein partners (Xiao et al. 1997; Servant et al. 1999; Jin et al. 2000). It is suggested that directional signaling is reinforced intracellularly through activating circuits. However, attenuating feedback loops and generalized inhibitory responses may also be critical (Bourne and Weiner 2002; Weiner et al. 2002; Devreotes and Janetopoulos 2003). In addition, mechanisms that regulate receptor adaptation are also clearly essential. Nonetheless, inhibitory networks that regulate chemotaxis are still poorly understood.

In a search for novel modifiers of chemotactic response in Dictyostelium, we now show that a heterotrimeric Gα protein, Gα9, functions to antagonize the PI3K, GC, and AC pathways that regulate different aspects of chemotaxis and cell polarity. In concordance, cells lacking Gα9 hyperpolarize in response to a chemoattractant source, whereas cells expressing a constitutively activated form of Gα9 produce spurious lateral pseudopods and lose directionality. This work identifies Gα signaling as a new regulator of chemotactic response, functioning to attenuate the activity of multiple pathways coupled to a chemoattractant receptor.

Results

Gα9 negatively regulates the adenylyl cyclase pathway

We have previously suggested that Gα9 negatively regulates early developmental patterning of Dictyostelium at the level of the cAMP chemoattractant signal response. Phenotypic data from gain- and loss-of-function mutants indicate that Gα9 regulates cAMP wave propagation (Brzostowski et al. 2002). To examine this, we starved wild-type cells, gα9-null cells, or wild-type cells expressing constitutively activated Gα9Q196L (Gα9Q196L cells) on an agarose substratum and compared the periodicity of cAMP waves emanating from signaling centers during the early stages of aggregation. cAMP wave propagation is visualized in dark-field as cells change shape in response to a cAMP chemoattractant signal (see Supplementary Movies 1, 2). We recorded dark-field images using time-lapse digital photography and measured the changes in pixel density over time to calculate wave periodicity. Under our developmental conditions, wild-type cells initiate a new cAMP wave approximately every 5.8 min, consistent with previous studies (Gross et al. 1976; Dormann et al. 2001). In contrast, gα9-null cells initiate cAMP waves significantly faster, averaging an ∼4.2-min periodicity. Gα9Q196L cells, however, have the opposite phenotype, routinely producing cAMP waves at a rate that was 20% slower than wild-type. Similar periodicity rates were obtained by dividing the number of waves passing through a set point during a defined time interval using indexed time-lapse videos (see Supplementary Movies 1, 2).

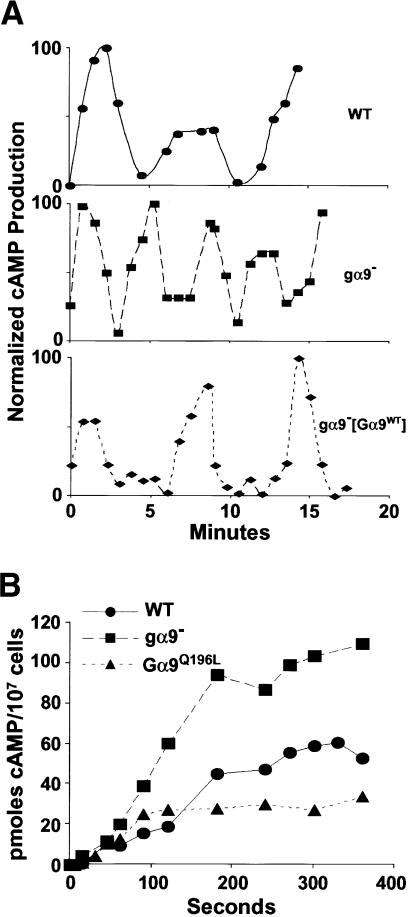

We next measured directly the rate of endogenous cAMP oscillations during an 18-min period of differentiation in suspension culture. As cells cycle through their adapted/de-adapted (sensitized/desensitized) states, levels of accumulated cAMP likewise vary temporally. Consistent with our dark-field analyses, gα9-null cells produce wave peaks of cAMP accumulation at ∼4-min intervals, 1.5 times more frequently than the ∼6-min intervals observed for wild-type cells (Fig. 1A). Re-expression of Gα9 using a highly active, constitutive actin promoter (gα9–[Gα9WT] cells) reverted the gα9-null cAMP wave pattern and frequency to that of wild-type cells (Fig. 1A), indicating that the gα9-null defects are the result of the single genetic lesion in Gα9. Furthermore, gα9–[Gα9WT] cells express Gα9 at levels far in excess of endogenous expression (Brzostowski et al. 2002), but do not exhibit a dominant phenotype.

Figure 1.

Gα9 negatively regulates the ACA activation pathway. (A) Wild-type (WT), gα9-null (gα9–), and gα9-null cells expressing wild-type Gα9 (gα9–[Gα9WT]) were differentiated for 6 h. in suspension culture. The level of endogenous cAMP produced in the absence of an exogenous stimulus was measured at the indicated time points. The initial cAMP peaks for the different strains were aligned temporally and the zero time point was set arbitrarily to compare the wave spacing during an 18-min period. The cAMP output for each strain was normalized to 100% at its highest peak. (B) Wild-type (WT), gα9-null, and Gα9Q196L-expressing (Gα9Q196L) cells were differentiated for 6 h in suspension culture and stimulated in the presence of a saturating dose of 2′ deoxy-cAMP and 10 mM DTT. Total cAMP was measured at the times indicated. The zero time point represents the value in unstimulated cells. A plateau in cAMP accumulation represents the adaptation of the aggregation-specific adenylyl cyclase (ACA). The data are representative of at least three independent experiments. (•) Wild-type; (▪) gα9–; (▴) Gα9Q196L.

The production of and response to periodic cAMP waves by cells in vivo is complex, but the above results show that Gα9 regulates the adenylyl cyclase (AC) pathway. To understand this regulation, we chose to quantify the level of total (intracellular and extracellular) cAMP produced in vivo in response to an exogenous cAMP stimulus. We first synchronously entrained wild-type, gα9-null, and Gα9Q196L cells with an identical regimen of exogenous cAMP pulses for 6 h to normalize their rates of differentiation (Brzostowski et al. 2002) so that all cells were at an equivalent developmental stage when studied. In addition, we determined that overall CAR1 affinity for cAMP is not altered by the loss of Gα9 (data not shown), indicating that the cells are similarly sensitive to cAMP stimuli.

Differentiated wild-type, gα9-null, and Gα9Q196L cells were then identically stimulated with a saturating dose of exogenous 2′deoxy cAMP to ensure that potential differences in endogenously produced cAMP would have no contributing effect on the intracellular signal response. The use of 2′deoxy cAMP as the exogenous CAR1 stimulant allowed us to differentiate the endogenously produced cAMP from the exogenous source. Under the assay conditions, a plateau in cAMP accumulation reflects the adaptation of AC activity. Cells lacking Gα9 accumulate approximatey twofold more cAMP during the course of the assay, whereas cells expressing constitutively active Gα9Q196L produce approximately twofold less cAMP relative to wild-type cells, strongly indicating that Gα9 negatively regulates the AC pathway (Fig. 1B). Wild-type cells that overexpress Gα9WT exhibit no inhibition in cAMP signaling (data not shown), indicating that the Gα9Q196L effects cannot be explained simply by nonspecific Gβγ sequestration due to overexpression of a Gα subunit or to an increased interaction of Gα2 with CAR1 upon the loss of Gα9.

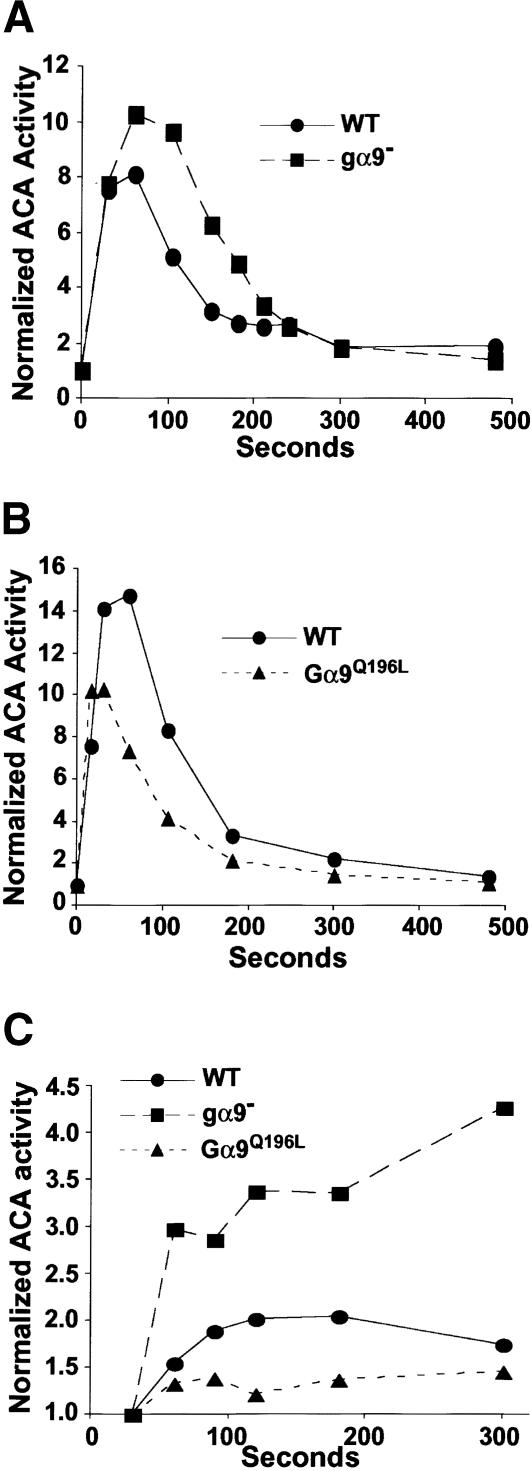

The kinetic data for cAMP accumulation (see Fig. 1B) indicate potential differences in AC adaptation rates among the various strains. Thus, we determined directly the effect of Gα9 on the activation and adaptation of the predominant adenylyl cyclase ACA. ACA activity was measured in vitro over time following chemoattractant stimulation of wild-type, gα9-null, and Gα9Q196L cells. In these assays, cells are stimulated with a saturating dose of cAMP, lysed at various times, and ACA activity measured for 30 sec. As shown in Figure 2, ACA is activated with the same initial kinetics in all cell types; however, the rates of ACA adaptation vary significantly. ACA adapts with the slowest kinetics in gα9-null cells (Fig. 2A). Strikingly, ACA activity adapts two to three times more rapidly in Gα9Q196L cells than in wild-type cells (Fig. 2B). To further compare ACA adaptation rates among these strains, we slightly modified the ACA assay to measure the time course of accumulation of newly synthesized cAMP in lysates. Here, cells were stimulated with cAMP and lysates prepared prior to the peak of ACA activation. Lysate reactions were assayed for various times for newly synthesized cAMP (Fig. 2C). As expected for wild-type cells, ACA activity adapts at ∼100 sec, as indicated by the plateau of cAMP accumulation. Consistent with ACA activity assays in Figures 1B and 2A and B, we found that adaptation of ACA is delayed in gα9-null cells, whereas ACA adapts more quickly in Gα9Q196L cells (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these results confirm that Gα9 negatively regulates the ACA pathway.

Figure 2.

Gα9 potentiates ACA adaptation. (A) Wild-type (WT) and gα9-null cells were differentiated for 6 h in suspension culture and stimulated with a saturating dose of cAMP. At the times indicated, lysates were prepared and the activity of ACA was determined by measuring the amount cAMP synthesized in vitro for 30 sec. The activity of ACA at each time point was normalized to the unstimulated activity level at zero seconds. A return to unstimulated, basal activity represents adaptation of ACA activity. The data are representative of at least three independent experiments. (B) Wild-type (WT) and Gα9Q196L cells were differentiated for 6 h in suspension culture and stimulated with a saturating dose of cAMP and ACA activities compared over time. See A for details. (C) Wild-type (WT), gα9-null, and Gα9Q196L cells were differentiated for 6 h in suspension culture and stimulated with a saturating dose of cAMP. A single lysate was prepared for each strain prior to the peak of ACA activity (see A,B). Accumulation of newly synthesized cAMP was measured in aliquots removed from the lysate at the times indicated. The level of cAMP synthesized during the course of the assay was normalized to the initial 30-sec reaction point. A plateau in cAMP accumulation indicates the time of ACA adaptation. The data are representative of at least three independent experiments. (•) Wild type; (▪) gα9–; (▴) Gα9Q196L.

Gα9 negatively regulates the chemoattractant-dependent membrane association of the PH domain protein CRAC

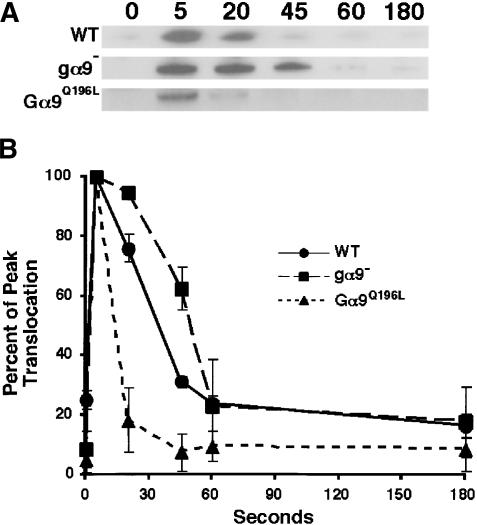

CAR1/Gα2βγ-mediated activation of ACA during development is dependent upon the action of CRAC, the Cytosolic Regulator of Adenylyl Cyclase (Insall et al. 1994; Parent et al. 1998). In unstimulated cells, CRAC is primarily cytosolic. Upon receptor stimulation, CRAC rapidly (∼5 sec) and transiently translocates to the plasma membrane, returning to the cytosol by ∼45 sec. The N-terminal PH domain of CRAC mediates this membrane association (Parent et al. 1998; Jin et al. 2000). To determine whether Gα9 functions upstream of CRAC translocation, we compared the membrane association of CRAC in differentiated wild-type, gα9-null, and Gα9Q196L cells that express the PH domain of CRAC fused to GFP (PHCRAC-GFP). Membranes were isolated at various times postchemoattractant stimulation, and associated proteins probed by immunoblot assay using α-GFP antibody (Fig. 3A). A quantitative analysis of these data is presented in Figure 3B. All cell types elicited the characteristic, rapid (5-sec) membrane translocation of PHCRAC-GFP in response to a saturating dose of cAMP, but the persistence of PHCRAC-GFP membrane association differed among the strains. In gα9-null cells, PHCRAC-GFP remained membrane associated approximately two times longer than in wild-type cells, whereas the pathway adapted much more quickly in Gα9Q196L cells. We conclude that Gα9 negatively regulates CRAC association with the membrane, potentially via regulation of the PH domain-binding sites PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2.

Figure 3.

Gα9 antagonizes cAMP-stimulated association of the PH-domain protein CRAC with the plasma membrane. (A) Wild-type (WT), gα9-null, and Gα9Q196L cells expressing PHCRAC-GFP were differentiated for 6 h in suspension culture and exposed to a saturating dose of cAMP. Proteins from membrane fractions were prepared at the times indicated, immunoblotted, and probed with α-GFP antibody. The zero-second point is the basal level of CRAC present in the membrane fraction of unstimulated cells. The blot is a representative experiment. (B) The data from A are presented graphically with S.E.M.s. Band pixel densities were obtained using NIH Image software. Responses were normalized to peak values at 5 sec that were set to 100%. (•) Wild type; (▪) gα9–; (▴) Gα9Q196L.

Gα9 negatively regulates the accumulation of PI(3,4,5)P3

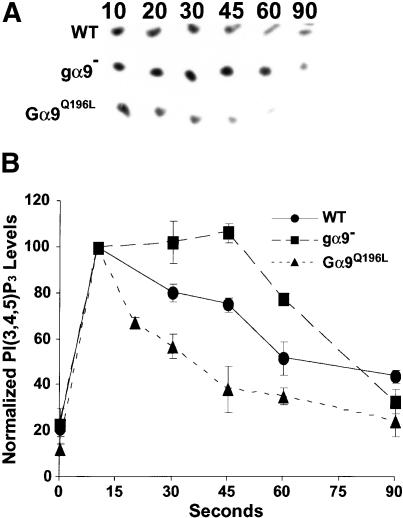

The transient association of CRAC to the plasma membrane is regulated by PH domain binding to the phosphorylated inositides PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 that are rapidly generated by PI3K, but also rapidly hydrolyzed by PTEN (Funamoto et al. 2002; Iijima and Devreotes 2002; Huang et al. 2003). The differences we observed in PHCRAC localization suggest that PI(3,4,5)P3/PI(3,4)P2 accumulation, and hence, the PI3K/PTEN cycle is regulated by Gα9. To examine this, we measured directly the receptor-mediated accumulation and loss of PI(3,4,5)P3 in wild-type, gα9-null, and Gα9Q196L cell lysates.

Differentiated cells were stimulated with saturating cAMP and lysed at 5 sec poststimulation in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. Each lysate was incubated over a time course, aliquots were extracted, and newly synthesized PI(3,4,5)P3 analyzed by TLC (Huang et al. 2003). Time courses for unstimulated control lysates were analyzed in parallel. All cell lines display maximal accumulation of PI(3,4,5)P3 in response to cAMP at 10 sec postlysis that was approximately fivefold over basal levels (Fig. 4). However, as the PI3K activity adapts, levels of newly synthesized PI(3,4,5)P3 return to their basal, steady-state values. In strong correlation with the kinetics of CRAC translocation (see Fig. 3), PI(3,4,5)P3 adaptation occurs more slowly for gα9-null cells than for wild type. In wild-type cells, PI(3,4,5)P3 levels return to near steady-state by 60 sec poststimulation, consistent with the rapid cAMP-stimulated activation/deactivation of PI3K (Huang et al. 2003). However, at 60 sec in gα9-null lysates, PI(3,4,5)P3 levels are only reduced by ∼25% (Fig. 4B). Thus, the adaptive phase for PI(3,4,5)P3 accumulation is significantly delayed in gα9-null cells. In contrast, PI(3,4,5)P3 levels drop more precipitously for Gα9Q196L cells (Fig. 4), again indicating a converse and hyperadaptive response for Gα9Q196L cells. We suggest that Gα9 regulates the translocation of CRAC to the inner surface of the plasma membrane by modulating the PI3K/PTEN cycle.

Figure 4.

Gα9 negatively regulates PI(3,4,5)P3 accumulation. (A) Wild-type (WT), gα9-null, and Gα9Q196L cells were differentiated for 6 h in suspension culture and stimulated with a saturating dose of cAMP. A lysate was prepared from each strain at 5-sec poststimulation, corresponding to the peak of PI3K activity and incubated in the presence of [32P-γ]ATP. Aliquots were removed at the times indicated, and lipids were extracted for TLC analysis to monitor the changes in the level of PI(3,4,5)P3. Unstimulated cells were similarly assayed over the same time course. The scans are representative of three independent experiments. (B) The data from A and two independent experiments are presented graphically. PI(3,4,5)P3 pixel densities were obtained using the ImageQuant software package. The normalized values (with S.E.M.s) obtained at 10 sec were approximately equivalent for each strain and were set to 100%. In addition, for each strain, unstimulated values at 10 sec were ∼20% of that observed with stimulation. (•) Wild type; (▪) gα9–; (▴) Gα9Q196L.

Ectopic expression of Gα9 rescues Gβγ-dependent developmental events absent in gα2-null cells

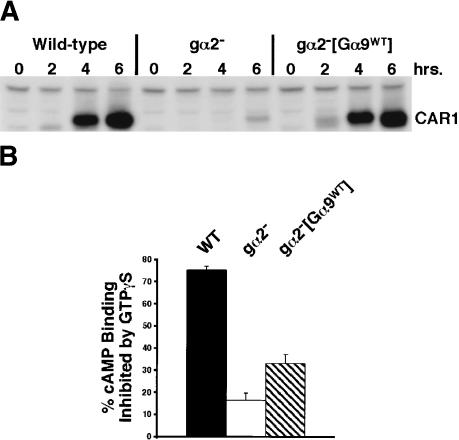

Whereas we suggest that Gα9 is a negative regulator of chemotactic pathways downstream of Gβγ, Gα9 may potentially function as part of a CAR1/Gα9βγ complex. Therefore, in addition to its role as a signaling antagonist, Gα9 may serve as an activating G-protein subunit to mobilize Gβγ. To test this hypothesis, we examined whether ectopic expression of Gα9 could partially substitute for Gα2, the major Gα subunit coupled to CAR1 (Kumagai et al. 1991; Gundersen 1997; Janetopoulos et al. 2001). Because current data indicate that many pathways downstream of CAR1 are regulated by released Gβγ and not by activated Gα2 (Wu et al. 1995), CAR1/Gα9βγ complex formation may rescue the developmental defects caused by loss of the cAMP-regulated release of Gβγ in gα2-null cells. We chose to compare cAMP-induced expression of CAR1 in wild-type cells, gα2-null cells, and gα2-null cells that express Gα9 (gα2–[Gα9WT]) using the highly active, constitutive actin promoter. CAR1 is the best characterized marker for early Dictyostelium development (Saxe et al. 1991; Louis et al. 1993; Mu et al. 1998, 2001), and its cAMP-regulated expression requires activation of Gβγ, but not of ACA (Saxe et al. 1991). Thus, the antagonistic action of Gα9 on ACA should not inhibit CAR1 expression.

Wild-type, gα2-null, and gα2–[Gα9WT] cells do not significantly express CAR1 prior to differentiation (Fig. 5A). Upon starvation, and consistent with previous observations (Saxe et al. 1991), all strains induce CAR1 to a low level. Wild-type cells show a very significant induction of CAR1 when treated with exogenous pulses of cAMP, whereas gα2-null cells are unable to mobilize the Gβγ-dependent activation of CAR1 expression (Saxe et al. 1991); thus, CAR1 levels remain low in gα2-null cells (Fig. 5A). However, ectopic expression of Gα9 in gα2-null cells rescues the cAMP-induced expression of CAR1 (Fig. 5A). These data indicate that Gα9 can form a functional Gα9βγ complex with CAR1 that mobilizes the cAMP-dependent release of Gβγ and of activated Gα9. Nonetheless, and not surprisingly, as activated Gα9 antagonizes the accumulation of PI(3,4,5)P3 and cAMP (and cGMP; see below), the gα2–[Gα9WT] cells lack strong chemotactic signaling responses (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Ectopic expression of Gα9 rescues G protein-dependent signaling of CAR1 in cells that lack Gα2. (A) Wild-type, gα2–, and gα2–[Gα9WT] cells were differentiated for 6 h in suspension culture in the presence of exogenous, 75-nM pulses of cAMP at 6-min intervals. CAR1 protein levels were monitored by Western blot at the times indicated. A nonspecific, cross-reacting species seen in all lanes attests to loading equivalency and is confirmed by Coomassie staining. (B) Wild-type, gα2–, and gα2–[Gα9WT] cells were differentiated for 6 h in suspension culture and membranes were prepared. Data with S.E.M.s represent the percent GTPγS inhibition of 5 nM cAMP binding for each strain as compared with untreated controls.

We have also more directly assessed the interaction of Gα9 with CAR1. The affinity of CAR1 for cAMP differs if it is functionally complexed with G proteins (Kumagai et al. 1991; Gundersen 1997). High-affinity sites for cAMP in wild-type membranes are inhibited by ∼75% when CAR1 binding is assayed in the presence of the G protein activator GTPγS as compared with controls (Fig. 5B). In contrast, only 15% of cAMP binding in gα2-null cells is sensitive to GTPγS treatment (Fig. 5B; Gundersen 1997). We therefore analyzed the ability of Gα9 to reconstitute the GTPγS-regulated, high-affinity state of CAR1 in the absence of Gα2. Ectopic expression of Gα9 in gα2-null cells shows a very significant rescue of GTPγS sensitivity for cAMP binding. Approximately one-third of the G protein-regulated, cAMP-binding sites that were lost upon deletion of Gα2 are recovered in gα2–[Gα9WT] cells (Fig. 5B). These data further support the conclusion that Gα9 is able to couple with CAR1.

Lateral pseudopod formation is suppressed in gα9-null cells

To determine the function of Gα9 for cell polarity and chemotaxis, we analyzed quantitatively the response of differentiated wild-type, gα9-null, and Gα9Q196L cells to an exogenous point source of cAMP, utilizing the DIAS software package (Soll 1999). Figure 6A shows an overlay of cell images taken at 30-sec intervals. Movies of traced individual cells can also be viewed (see Supplementary Movies 3-1 through 5-2).

Figure 6.

Gα9 negatively regulates multiple cAMP-mediated chemotactic pathways. (A) Wild-type (WT), gα9-null, and Gα9Q196L cells were differentiated for 6 h in suspension culture and plated on plastic dishes. Cells were allowed to polarize and chemotax toward a pipette containing a 1-μM solution of cAMP. Images of chemotaxing cells were captured every 30 sec for ∼15 min. Individual cells were traced and analyzed using the DIAS (Soll 1999) software package. For additional images, see Supplementary Movies 3-1 through 5-2. A stack of eight cell tracings (4 min) for each cell line is shown. Cell tracings are arranged to demonstrate relative directional movement, polarity, and distances traveled toward the cAMP point source (black dot) and are representative of at least five independent experiments. (B) Wild-type (WT), gα9-null, and Gα9Q196L cells were differentiated and stimulated with a saturating dose of cAMP. The relative amount of filamentous (F) actin was measured at the indicated times. Stimulated values were normalized to the unstimulated value measured at zero seconds. Graphed are the averages and S.E.M.s of three independent experiments. (C) Wild-type (WT), gα9-null, and Gα9Q196L cells were differentiated and stimulated with a saturating dose of cAMP. The level of accumulated cGMP was measured by radioimmuno assay at the indicated time points. The zero-second point is the basal level of cGMP in unstimulated cells. The results are representative of at least three independent experiments. (•) Wild type; (▪) gα9–; (▴) Gα9Q196L.

In general, gα9-null cells are more highly polarized and elongate than wild-type cells. The average flat area of wild-type and gα9-null cells are approximately equivalent (±5%), yet routinely, wild-type cells are nearly twice as wide as gα9-nulls (Fig. 6A; see Supplementary Movies 3-1 through 4-2). gα9-null cells maintain their highly polarized shape and a single, dominant anterior pseudopod throughout chemotaxis and rarely produce lateral pseudopods. In contrast, wild-type cells have broad leading edges that project frequent pseudopods. (New pseudopod formation can be viewed by Difference Image analyses; see Supplementary Movies 3-2, 4-2). In addition, the rear of gα9-null cells is much more tapered relative to wild-type cells, suggesting that Gα9 regulates both the dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton at the anterior, but also myosin II assembly at the rear (see Fig. 6B,C). Loss of Gα9 improves the efficiency of chemotaxis toward a point source. The average chemotactic indices are 0.88 for wild-type cells and 0.96 for gα9-null cells, and the average instantaneous velocities (on plastic) are 5.9 μm/min for wild-type cells, and 8.5 μm/min for gα9-null cells.

In stark contrast, Gα9Q196L cells are far less polarized than wild-type cells and exhibit a chemotactic pheno-type that is largely opposite that of gα9-null cells. Gα9Q196L cells poorly maintain an anterior pseudopod during chemotaxis, but produce numerous lateral pseudopods that reorganize directed cell movement (Fig. 6A; see Supplementary Movies 5-1, 5-2). Their average chemotactic index is 0.80 (see Supplementary Movies 5-1, 5-2). Occasionally, lateral pseudopods are observed with a trajectory that is perpendicular to the direction of the chemoattractant point source, causing the disappearance of the rear of the cell. Nonetheless, Gα9Q196L cells chemotax faster than both wild-type and gα9-null cells, having an average instantaneous velocity of 12.3 μm/min.

The polymerization of actin predominantly at the leading edge and the contraction of myosin II at the sides and the rear of the cell are essential for directed cell migration (Devreotes and Janetopoulos 2003). In wild-type cells, the addition of chemoattractant leads to an increase in the proportion of polymerized actin, characterized by a rapid, approximately twofold increase over basal levels that adapts very quickly (see Fig. 6B; Iijima et al. 2002). This rapid phase is followed by a secondary slower (∼30 sec), shallow activation that is suggested to reflect the association of polymerized actin with pseudopod formation (Hall et al. 1988). In the initial phase, the kinetics of F-actin activation and adaptation in gα9-null cells is similar to wild type, although gα9-null cells consistently produce slightly more (∼1.2-fold) F-actin (see Fig. 6B). In contrast, the F-actin response in Gα9Q196L cells adapts more quickly (Fig. 6B). In the secondary response, both gα9-null and Gα9Q196L cells exhibit a higher, broad peak of F-actin relative to wild-type cells (Fig. 6B). This greater production of F-actin is consistent with the maintenance of a dominant pseudopod in gα9-null cells during chemotaxis, and with the more frequent assembly of lateral pseudopods in Gα9Q196L cells.

Myosin II phosphorylation is regulated in part by a cGMP-dependent cascade that is required for retraction of the rear of the cell during forward movement and for cortical tension to suppress lateral pseudopod formation (Bosgraaf et al. 2002). cGMP levels correlate directly with an increase in phosphorylation of myosin II heavy and light chains, suppression of lateral pseudopod formation, and enhanced chemotaxis (Bosgraaf et al. 2002). We therefore measured the production of cGMP in response to chemoattractant. Guanylyl cyclase (GC) is rapidly activated (∼15 sec.) by and adapted to a saturating cAMP stimulus (Fig. 6C). gα9-null cells significantly overproduce cGMP, whereas Gα9Q196L cells synthesize relatively low levels of cGMP relative to wild-type cells (Fig. 6C), suggesting that Gα9 negatively regulates the GC pathway, paralleling its effect on the ACA and PI3K/PTEN pathway. Further, the chemotaxis phenotypes of gα9-null and Gα9Q196L cells correlate with their respective levels of receptor-mediated production of cGMP, and thus, are in complete agreement with the biochemical data generated with saturating levels of cAMP. Chemotactic behaviors akin to gα9-null cells are observed in cells that lack the major cGMP-specific PDEs, which have increased cGMP levels and enhanced chemotaxis (Bosgraaf et al. 2002). In several systems, anterior and rear cell polarity organizations are reciprocally inhibitory (Li et al. 2003; Xu et al. 2003). Potentially, the increased production of lateral pseudopods and correlated F-actin polymerization seen in the Gα9Q196L cells reflects their diminished cGMP and myosin II responses and the consequent loss in lateral inhibition.

Discussion

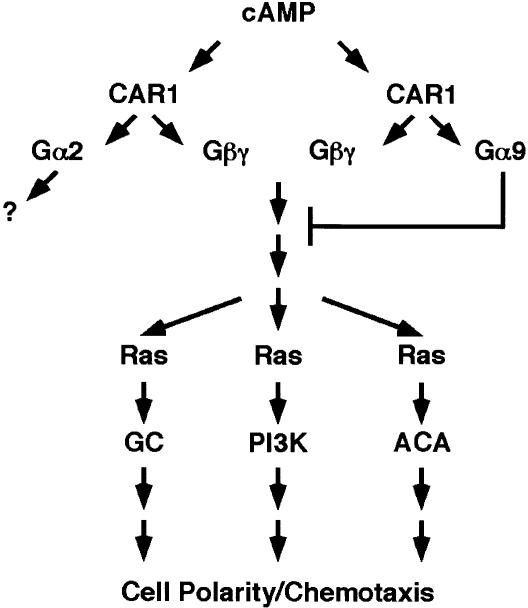

Seven-transmembrane chemoattractant receptors signal to downstream effectors through their coupled heterotrimeric Gαβγ proteins. In Dictyostelium and neutrophils, the activating signals to promote anterior movement toward a chemoattractant is transmitted initially by the Gβγ subunits (see Fig. 7); Gα subunits of either cell, Gαi in neutrophils, or the related Gα2 in Dictyostelium, may not be required for activating pathways at the leading edge (Wu et al. 1995; Jin et al. 1998; Neptune et al. 1999). Like many pathways that function downstream of receptor signaling, chemotactic responses cycle through both activated (sensitized) and deactivated (desensitized/adapted) states. Thus, inhibitory networks, as well as excitatory pathways, are essential for cells to monitor subtle changes in signal source to maintain polarity in shallow chemoattractant gradients. Although considerable information exists regarding Gβγ-dependent excitatory pathways, little is known mechanistically about inhibitory or adaptive signaling. We now suggest that certain activating or inhibitory signals can be transmitted differentially by Gβγ and Gα subunits, respectively, in Dictyostelium and mammalian cells.

Figure 7.

A model for the activation of Gα9 by cAMP. In unstimulated cells, CAR1 is coupled to Gα2βγ and Gα9βγ. Upon ligand binding of CAR1, both heterotrimeric complexes become activated, releasing Gβγ, Gα2-GTP, and Gα9-GTP. Gβγ is suggested to activate a family of Ras proteins, which initiate down-stream effector signaling of the PI3K, GC, and AC pathways (see Kimmel and Parent 2003a,b); targets downstream, in turn, are required to regulate actin and myosin II dynamics. Released Gβγ will also induce cAMP-regulated gene expression (e.g., CAR1) during early development by a separate pathway. Current data suggest that Gα2 primarily serves to mediate the release of Gβγ from stimulated CAR1. Gα2-GTP has not been directly linked to any downstream chemoattractant pathway. Because Gα9 functions to negatively regulate multiple pathways activated by Gβγ, we place Gα9 at a signaling junction that is common to the PI3K, GC, and AC pathways, and thus, immediately downstream of CAR1/Gαβγ activation. However, the immediate effectors of Gβγ or of Gα9-GTP have not yet been identified.

Three major effectors that function downstream of CAR1 and Gβγ activation in Dictyostelium are targets for Gα9 (see Fig. 7). Because these pathways appear to function independently, we do not believe that they are each regulated in a separate and unique manner by Gα9. GC activation is not altered by loss of PTEN function (Iijima and Devreotes 2002). Although potentially ACA regulation by CRAC could involve a PI(3,4,5)P3-dependent translocation, current data do not prove a mechanistic link between the two pathways. pten-null cells show persistent PI(3,4,5)P3 accumulation and CRAC membrane association, but also normal ACA adaptation (Iijima and Devreotes 2002). In addition, CRAC and ACA are spatially separated within the cell and the temporal peaks of CRAC translocation and ACA activation are unlinked (Parent et al. 1998; Kriebel et al. 2003). We suggest that Gα9 attenuates a signaling junction that is shared by each component pathway and lies immediately downstream of CAR1/Gβγ (see Fig. 7). One potential target for Gα9 signaling is the Ras family of small G proteins, which is a common element implicated in the separate activations of the ACA, GC, and PI3K pathways (see Fig. 7).

There are 12 Ras genes in Dictyostelium, and although none are separately essential for chemotaxis, loss-of-function mutations of several do cause signaling defects (Wilkins and Insall 2001). In particular, RasC and RasG and their putative upstream activating guanine nucleo-tide exchange factors (GEFs) have been directly implicated in control of PI3K, ACA, and GC in a pathway for chemotaxis that is downstream of Gβγ activation (Lim et al. 2001; Funamoto et al. 2002). Like the mammalian PI3K family, the PI3Ks of Dictyostelium contain a Ras-binding domain. This domain and Ras interaction are not required for membrane association of PI3K, but they are required for enzyme activation (Funamoto et al. 2002). For ACA, several soluble components, in addition to CRAC, participate in activation. Ras-interacting protein 3 (RIP3) is required for normal chemotaxis and for receptor activation of both ACA and GC (Lee et al. 1999). Small G proteins have been implicated in the regulation of both the soluble and membrane-associated GCs of Dictyostelium (Roelofs et al. 2001). In some respects, certain ras-null cells have chemotactic defects that are similar to that of Gα9Q196L cells, suggesting a potential genetic or biochemical interaction (Wilkins and Insall 2001). Ras may function downstream of CAR1/Gβγ activation, placing it, its activating GEFs, or inactivating GAPs as possible targets for regulation by Gα9.

Functional parallels for Gα9 signaling may be found in mammalian cells. As in Dictyostelium (Wu et al. 1995; Jin et al. 1998), mammalian Gβγ appears to function as an activating transmitter of pathways downstream of chemokine receptors to regulate the leading edge (Neptune and Bourne 1997; Neptune et al. 1999). However, recent data may indicate that Gα subunits are more than passive components in the system, but may also function as direct regulators to establish and maintain cell polarity (Xu et al. 2003). In neutrophils, Gα12/13 will promote uropod formation while antagonizing leading edge polarity (Xu et al. 2003), although a definitive linkage of Gα12/13 to chemotactic response has not been demonstrated. Clearly, Gα12/13 and Gα9 are not entirely equivalent, as the phenotypes of the loss-of-function gα9-null or gain-of-function Gα9Q196L cells are largely opposite of that observed with Gα12/13 mutations. Nonetheless, Gα9 and Gα12/13 may both couple to chemoattractant receptors in complex with Gβγ, yet exhibit functions that are antagonistic to Gβγ (see Fig. 7). Other mammalian Gα subunits may regulate chemotaxis in a manner similar to Gα9. Constitutively activated Gαq can suppress β-adrenergic- or muscarinic-dependent activation of Akt, a PI3K-regulated protein kinase (Bommakanti et al. 2000) and specifically inhibit the activity of p110a PI3K (Ballou et al. 2003). Although these observations may implicate Gαq in chemotaxis, the possibility has not been explored.

In conclusion, Gβγ serves to activate the downstream effectors AC, GC, and PI3K in chemotaxing Dictyostelium. We propose that Gα9 functions as a negative regulator of multiple CAR1-activated pathways regulated by Gβγ, and suggest that functionally similar Gα mechanisms may exist during chemotaxis of mammalian cells. Potentially, such signaling mechanisms provide cells with a level of plasticity to respond to rapid changes in chemoattractant gradients.

Materials and methods

Growth and development of Dictyostelium

Wild-type (Ax3), blasticidin-resistant, and G418-resistant strains were grown and developed as described (Kim et al. 1999). The construction of gα9-null and Gα9Q196L cells were previously described, as were methods for transformations and selection of clonal or population cell lines (Brzostowski et al. 2002). For differentiation in suspension culture, cells were shaken in flasks at 100rpm in DB at 2 × 107 cells/mL. After 1 h, cells were provided exogenous 75 nM pulses of cAMP every 6 min for an additional 5 h. Cells were then harvested for the assays described below. CAR1 expression was measured as described (Kim and Devreotes 1994).

Adenylyl cyclase, cAMP, and cGMP assays

For standard adenylyl cyclase activity assays (see Fig. 2), differentiated cells were diluted to 1 × 107 cells/mL and shaken at 200 RPM in phosphate buffer containing 2 mM caffeine for 30 min to inhibit endogenous cAMP signaling, washed from caffeine, resuspended to 8 × 107 cells/mL, and stimulated with 10 μM cAMP. At specific time points poststimulation, Aliquots of cells were lysed by passage through a 5-μm millipore filter into tubes containing [α-32P]ATP, and then incubated for 30 sec. The amount of [32P]cAMP was measured as described (Theibert and Devreotes 1986).

This assay was also modified slightly to measure the continuous accumulation of cAMP in vitro (see Fig. 2C). Cells were lysed into a single tube and aliquots were removed at various times. The level of cAMP accumulation over time was measured as above.

For cAMP and cGMP in vivo accumulation assays, cells were treated with caffeine for 30 min, washed, resuspended in PB to 5 × 107 cells/mL and stimulated with 5 μM 2′deoxy-cAMP. Aliquots of stimulated cells were taken at specific time points, and the total level of cAMP or cGMP was measured by competition assay using Amersham kits TRK 432 (cAMP) or TRK 500 (cGMP).

Endogenous periodic changes of cAMP were measured in cells differentiated in suspension culture in the absence of external cAMP. A total of 100 μL of aliquots were removed from shaking flasks at 45-sec intervals and lysed in HCl. The total amount of cAMP in neutralized lysates was measured using the [125I]cAMP FlashPlate Assay Kit (NEN catalog no. SMP001) and the Perkin Elmer Top Count microplate scintillation counter.

PI(3,4,5)P3 assays

Cells were differentiated, treated with 2 mM caffeine, washed, and resuspended to 8 × 107 cells/mL. Cells were stimulated, lysed at 5 sec into [γ-32P]ATP, and incubated. At specific time points, aliquots were removed and lipids extracted and separated by TLC (Huang et al. 2003).

F-Actin assays

Differentiated cells were diluted to 1 × 107 cells/mL and shaken at 200 RPM in phosphate buffer containing 3 mM caffeine for 30 min, and maintained in caffeine before stimulation. At specific time points, stimulated cells were fixed and stained with TRITC-phalloidin and the level of F-actin was measured as described (Kim et al. 1997).

PH translocation assays

Membrane and cytosolic fractions were prepared (Parent et al. 1998) and proteins separated using 4%–12% NuPage gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore). GFP-tagged proteins were detected using an α-GFP mouse monoclonal antibody (Covance).

Chemotaxis assays

Chemotaxis assays were perform as described (Parent et al. 1998). Differentiated cells were plated on plastic dishes at a density of ∼6 × 104 cells/cm2. A micropipette (Femtotips, Eppendorf) containing 1 μM cAMP was placed in the chamber, and images were captured using a Zeiss inverted microscope mounted with a digital camera. Images were analyzed using the DIAS software package (Soll 1999).

GTPγS inhibition of cAMP binding

Differentiated cells were treated with 2 mM caffeine, washed, and resuspended to 1 × 108 cells/mL in phosphate buffer containing 2 mM MgSO4 (PM). Cells were lysed by passage through a 5-μm millipore filter. Membranes were pelleted by centrifugation and washed once in PM. Membranes were resuspended in PM and incubated with 5 nM [3H]cAMP in the presence or absence of GTPγS for 5 min on ice (Snaar-Jagalska and Van Haastert 1994). To determine nonspecific [3H]cAMP binding, membranes were incubated as above with the addition of 100 μM unlabeled cAMP. Membranes were pelleted, and the supernatants removed. The pellet was dissolved in 1% SDS and the bound [3H]cAMP was determined by scintillation counting.

Acknowledgments

We are exceedingly grateful to Drs. F. Comer, D. Hereld, T. Khurana, L. Kim, L. Kreppel, D. Rosel, and E. Shugart for the many and helpful discussions.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1173404.

Corresponding author.

References

- Ballou L.M., Lin, H.Y., Fan, G., Jiang, Y.P., and Lin, R.Z. 2003. Activated G α q inhibits p110 α phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 23472-23479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommakanti R.K., Vinayak, S., and Simonds, W.F. 2000. Dual regulation of Akt/protein kinase B by heterotrimeric G protein subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 38870-38876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosgraaf L., Russcher, H., Smith, J.L., Wessels, D., Soll, D.R., and Van Haastert, P.J. 2002. A novel cGMP signalling pathway mediating myosin phosphorylation and chemotaxis in Dictyostelium. EMBO J. 21: 4560-4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne H.R. and Weiner, O. 2002. A chemical compass. Nature 419: 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzostowski J.A., Johnson, C., and Kimmel, A.R. 2002. Gα-mediated inhibition of developmental signal response. Curr. Biol. 12: 1199-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devreotes P. and Janetopoulos, C. 2003. Eukaryotic chemotaxis: Distinctions between directional sensing and polarization. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 20445-20448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dormann D., Kim, J.Y., Devreotes, P.N., and Weijer, C.J. 2001. cAMP receptor affinity controls wave dynamics, geometry and morphogenesis in Dictyostelium. J. Cell. Sci. 114: 2513-2523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firtel R.A. and Chung, C.Y. 2000. The molecular genetics of chemotaxis: Sensing and responding to chemoattractant gradients. BioEssays 22: 603-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funamoto S., Meili, R., Lee, S., Parry, L., and Firtel, R.A. 2002. Spatial and temporal regulation of 3-phosphoinositides by PI 3-kinase and PTEN mediates chemotaxis. Cell 109: 611-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J.D., Peacey, M.J., and Trevan, D.J. 1976. Signal emission and signal propagation during early aggregation in Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Cell. Sci. 22: 645-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen R.E. 1997. Phosphorylation of the G protein α-subunit, Gα 2, of Dictyostelium discoideum requires a functional and activated Gα 2. J. Cell. Biochem. 66: 268-276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A.L., Schlein, A., and Condeelis, J. 1988. Relationship of pseudopod extension to chemotactic hormone-induced actin polymerization in amoeboid cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 37: 285-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.E., Iijima, M., Parent, C.A., Funamoto, S., Firtel, R.A., and Devreotes, P. 2003. Receptor-mediated regulation of PI3Ks confines PI(3,4,5)P3 to the leading edge of chemotaxing cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 14: 1913-1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima M. and Devreotes, P. 2002. Tumor suppressor PTEN mediates sensing of chemoattractant gradients. Cell 109: 599-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima M., Huang, Y.E., and Devreotes, P. 2002. Temporal and spatial regulation of chemotaxis. Dev. Cell 3: 469-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insall R., Kuspa, A., Lilly, P.J., Shaulsky, G., Levin, L.R., Loomis, W.F., and Devreotes, P. 1994. CRAC, a cytosolic protein containing a pleckstrin homology domain, is required for receptor and G protein-mediated activation of adenylyl cyclase in Dictyostelium. J. Cell. Biol. 126: 1537-1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janetopoulos C., Jin, T., and Devreotes, P. 2001. Receptor-mediated activation of heterotrimeric G-proteins in living cells. Science 291: 2408-2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin T., Amzel, M., Devreotes, P.N., and Wu, L. 1998. Selection of gbeta subunits with point mutations that fail to activate specific signaling pathways in vivo: Dissecting cellular responses mediated by a heterotrimeric G protein in Dictyostelium discoideum. Mol. Biol. Cell 9: 2949-2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin T., Zhang, N., Long, Y., Parent, C.A., and Devreotes, P.N. 2000. Localization of the G protein βγ complex in living cells during chemotaxis. Science 287: 1034-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.Y. and Devreotes, P.N. 1994. Random chimeragenesis of G-protein-coupled receptors. Mapping the affinity of the cAMP chemoattractant receptors in Dictyostelium. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 28724-28731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.Y., Soede, R.D., Schaap, P., Valkema, R., Borleis, J.A., Van Haastert, P.J., Devreotes, P.N., and Hereld, D. 1997. Phosphorylation of chemoattractant receptors is not essential for chemotaxis or termination of G-protein-mediated responses. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 27313-27318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim L., Liu, J., and Kimmel, A.R. 1999. The novel tyrosine kinase ZAK1 activates GSK3 to direct cell fate specification. Cell 99: 399-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel A.R. and Parent, C.A. 2003a. Dictyostelium discoideum cAMP chemotaxis pathway. Science STKE connections map. Science http://stke.sciencemag.org/cgi/cm/stkecm;CMP_7918.

- ____. 2003b. The signal to move: D. discoideum go orienteering. Science 300: 1525-1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriebel P.W., Barr, V.A., and Parent, C.A. 2003. Adenylyl cyclase localization regulates streaming during chemotaxis. Cell 112: 549-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai A., Hadwiger, J.A., Pupillo, M., and Firtel, R.A. 1991. Molecular genetic analysis of two Gα protein subunits in Dictyostelium. J. Biol. Chem. 266: 1220-1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Parent, C.A., Insall, R., and Firtel, R.A. 1999. A novel Ras-interacting protein required for chemotaxis and cyclic adenosine monophosphate signal relay in Dictyostelium. Mol. Biol. Cell 10: 2829-2845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Hannigan, M., Mo, Z., Liu, B., Lu, W., Wu, L., Smrcka, A.V., Wu, G., Li, L., Liu, M., et al. 2003. Directional sensing requires G-mediated PAK1 and PIX-dependent activation of Cdc42. Cell 114: 215-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim C.J., Spiegelman, G.B., and Weeks, G. 2001. RasC is required for optimal activation of adenylyl cyclase and Akt/PKB during aggregation. EMBO J. 20: 4490-4499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis J.M., Saxe III, C.L., and Kimmel, A.R. 1993. Two transmembrane signaling mechanisms control expression of the cAMP receptor gene CAR1 during Dictyostelium development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 90: 5969-5973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlot S. and Firtel, R.A. 2003. Leading the way: Directional sensing through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and other signaling pathways. J. Cell. Sci. 116: 3471-3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu X., Lee, B., Louis, J.M., and Kimmel, A.R. 1998. Sequencespecific protein interaction with a transcriptional enhancer involved in the autoregulated expression of cAMP receptor 1 in Dictyostelium. Development 125: 3689-3698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu X., Spanos, S.A., Shiloach, J., and Kimmel, A. 2001. CRTF is a novel transcription factor that regulates multiple stages of Dictyostelium development. Development 128: 2569-2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neptune E.R. and Bourne, H.R. 1997. Receptors induce chemotaxis by releasing the βγ subunit of Gi, not by activating Gq or Gs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94: 14489-14494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neptune E.R., Iiri, T., and Bourne, H.R. 1999. Galphai is not required for chemotaxis mediated by Gi-coupled receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 2824-2828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent C.A., Blacklock, B.J., Froehlich, W.M., Murphy, D.B., and Devreotes, P.N. 1998. G protein signaling events are activated at the leading edge of chemotactic cells. Cell 95: 81-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelofs J., Loovers, H.M., and Van Haastert, P.J. 2001. GTPγS regulation of a 12-transmembrane guanylyl cyclase is retained after mutation to an adenylyl cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 40740-40745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe C.L., Johnson, R.L., Devreotes, P.N., and Kimmel, A.R. 1991. Expression of a cAMP receptor gene of Dictyostelium and evidence for a multigene family. Genes & Dev. 5: 1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servant G., Weiner, O.D., Neptune, E.R., Sedat, J.W., and Bourne, H.R. 1999. Dynamics of a chemoattractant receptor in living neutrophils during chemotaxis. Mol. Biol. Cell 10: 1163-1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaar-Jagalska B.E. and Van Haastert, P.J. 1994. G-protein assays in Dictyostelium. Methods Enzymol. 237: 387-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soll D.R. 1999. Computer-assisted three-dimensional reconstruction and motion analysis of living, crawling cells. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph 23: 3-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theibert A. and Devreotes, P.N. 1986. Surface receptor-mediated activation of adenylate cyclase in Dictyostelium. Regulation by guanine nucleotides in wild-type cells and aggregation deficient mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 261: 15121-15125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomchik K.J. and Devreotes, P.N. 1981. Adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate waves in Dictyostelium discoideum: A demonstration by isotope dilution–fluorography. Science 212: 443-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner O.D., Neilsen, P.O., Prestwich, G.D., Kirschner, M.W., Cantley, L.C., and Bourne, H.R. 2002. A PtdInsP(3)- and Rho GTPase-mediated positive feedback loop regulates neutrophil polarity. Nat. Cell. Biol. 4: 509-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins A. and Insall, R.H. 2001. Small GTPases in Dictyostelium: Lessons from a social amoeba. Trends Genet. 17: 41-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L., Valkema, R., Van Haastert, P.J., and Devreotes, P.N. 1995. The G protein β subunit is essential for multiple responses to chemoattractants in Dictyostelium. J. Cell. Biol. 129: 1667-1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Z., Zhang, N., Murphy, D.B., and Devreotes, P.N. 1997. Dynamic distribution of chemoattractant receptors in living cells during chemotaxis and persistent stimulation. J. Cell. Biol. 139: 365-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Wang, F., Van Keymeulen, A., Herzmark, P., Straight, S., Kelly, K., Takuwa, Y., Sugimoto, N., Mitchison, T., and Bourne, H.R. 2003. Divergent signals and cytoskeletal assemblies regulate self-organizing polarity in neutrophils. Cell 114: 201-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]