Abstract

A reaction between imines and anhydrides has been developed with chiral disubstituted anhydrides and chiral imines. The synthesis of highly substituted γ-lactams with three stereogenic centers, including one quaternary center, proceeds at room temperature in high yield and with high diastereoselectivity in most cases. Enantiomerically pure alkyl-substituted anhydrides proceed with no epimerization, thus providing access to enantiomerically pure penta-substituted lactam products.

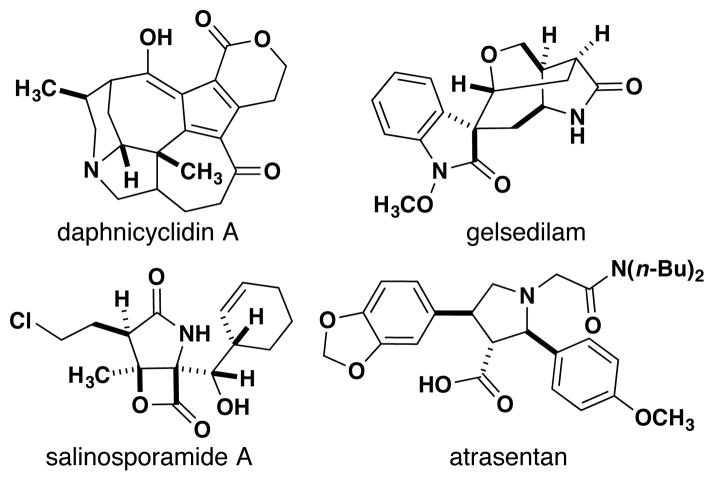

Densely substituted γ-lactams (2-pyrrolidinones) and pyrrolidines are found among natural products and pharmaceutical compounds (Figure 1).1 The prevalence of these structural motifs has driven the development of new synthetic methodologies.2 Although each of these methods offers certain advantages, drawbacks include limited substrate scope,2a,2c–d expensive catalysts,2b and multi-step processes.2a–c,2h

Figure 1.

Examples of molecules with a γ-lactam or a pyrrolidine

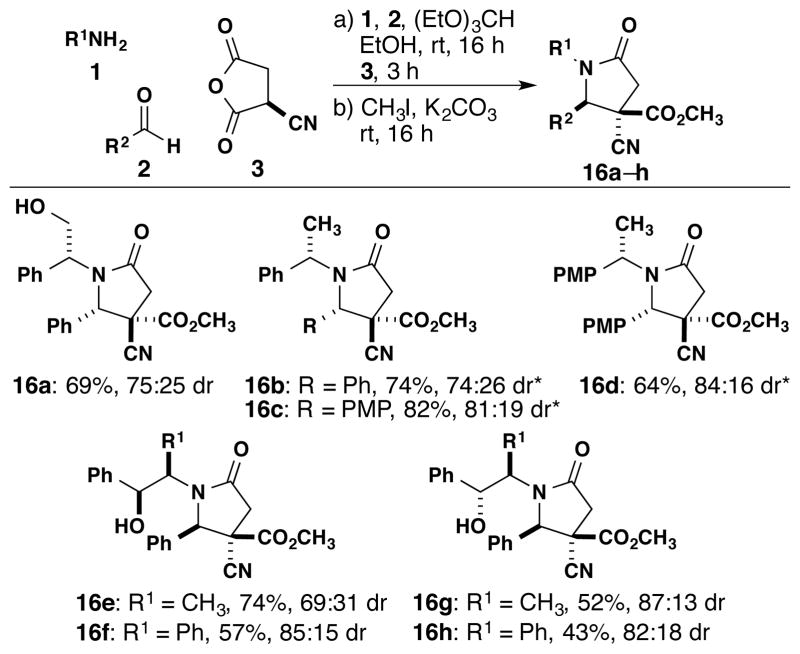

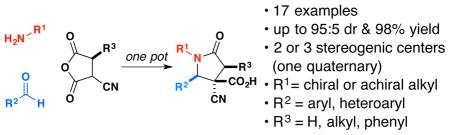

The direct reaction of imines with cyclic anhydrides forms γ-lactams in a single step.3 One consistent limitation of this reaction has been the inability to produce enantiomerically enriched compounds. In the course of our studies directed toward the synthesis of diverse libraries of lactams, we recently reported the remarkably high reactivity and stereoselectivity of the reaction between α-cyanosuccinic anhydride 3 and achiral imines formed from 1 and 2 for the formation of tetra-substituted γ-lactams 4 (Scheme 1).3d These studies prompted us to explore fully the opportunities for further transformations of the lactam products and asymmetric synthesis. Herein we report the first examples of stereocontrol from chiral anhydrides and chiral imines in the formation of tetra- and pentasubstituted γ-lactams.

Scheme 1.

Reactions of Achiral Imines and Cyanosuccinic Anhydride

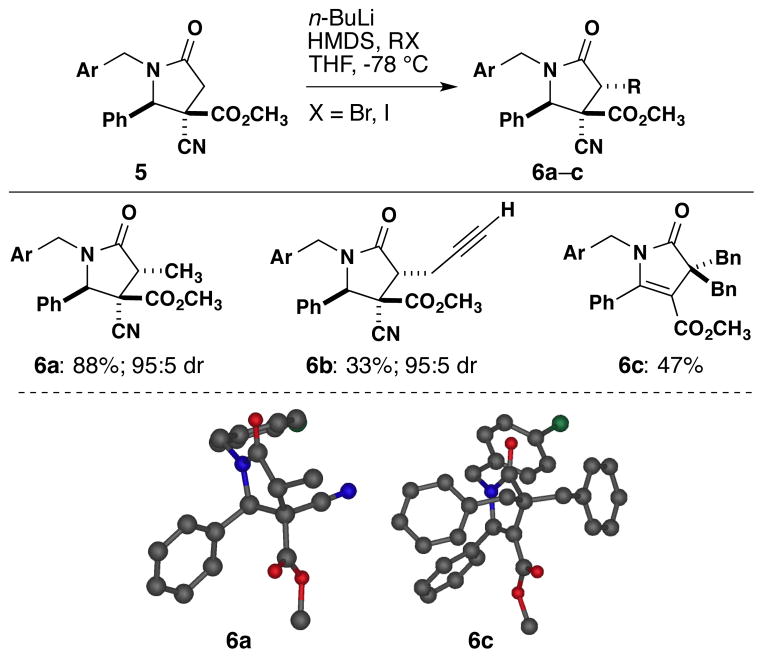

Our efforts in the development of asymmetric imine-anhydride reactions stemmed from our development of post-imine-anhydride reaction modifications of the γ-lactam products. We initially explored the preparation of α-substituted γ-lactams though alkylation (Scheme 2). Lactam 53d was methylated using LHMDS to give 6a with 95:5 diastereoselectivity, and X-ray crystallographic analysis4 indicated that the incoming electrophile approached opposite to the adjacent carboxymethyl group. Unfortunately, other electrophiles (6b–c) gave poor yields. In the case of benzyl bromide, the gem-alkylated product 6c, which was determined by X-ray analysis,4 resulted from the elimination of the cyano group. The limited scope of alkylating the lactam compounds led us to pursue the use of disubstituted anhydrides and the possibility of forming enantiopure compounds.

Scheme 2.

Alkylation at the α-Carbon

Reaction conditions: 1 equiv of 5, 2.5 equiv of n-BuLi, 3.0 equiv of hexamethyldisilazane, and 2.6 equiv of the alkyl halide in tetrahydrofuran (0.6 M). Ar = 4Cl-C6H4.

We synthesized disubstituted succinic anhydrides for use in imine-anhydride reactions (Scheme 3). Following literature conditions, diester 8a was synthesized in two steps from ethyl lactate.5 Subsequent hydrolysis and cyclization gave anhydride 9. In order to explore the scope and diastereoselectivity of the disubstituted anhydrides, the isobutyl, benzyl, and phenyl analogs (10–12) were also prepared.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 3,4-Disubstituted Succinic Anhydrides

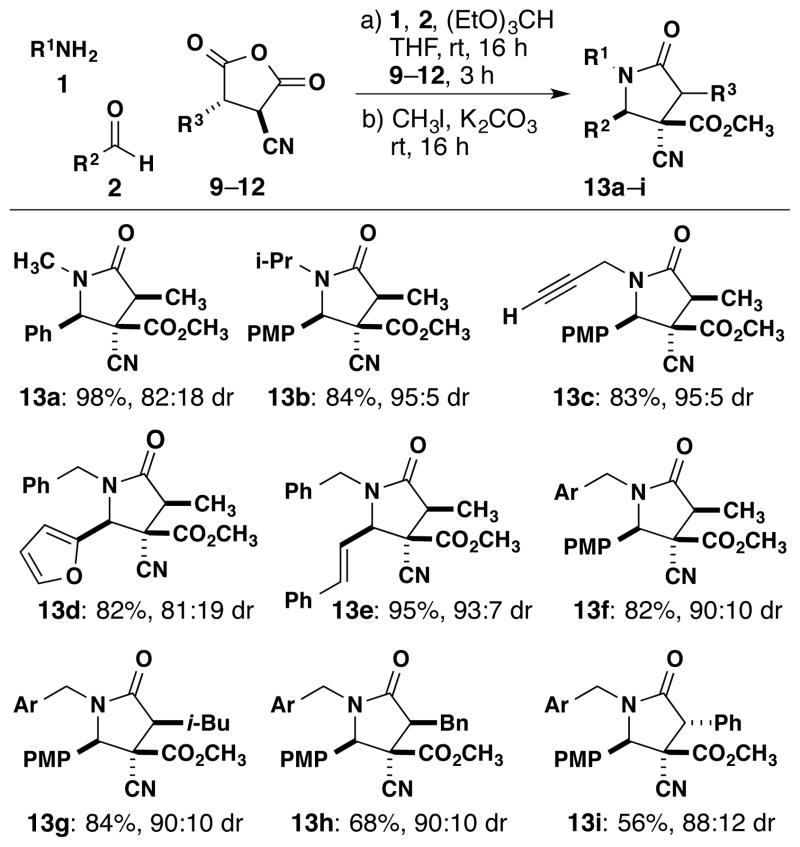

We explored the scope of the imine-anhydride reaction with respect to various imines and chiral disubstituted succinic anhydrides (Scheme 4). Using methyl-substituted cyanosuccinic anhydride 9, the reaction produced 13a–f in 82–98% yield and up to 95% selectivity for the formation of one major product out of the four possible diastereomers. The products (13g–i) from 10–12 gave similarly high selectivities. The analogous reaction of enantiomerically pure 9, prepared from (S)-ethyl lactate, demonstrated that the stereogenic center was preserved through the lactam-forming reaction.6 X-ray crystallographic analysis4 (Figure 2) revealed that the major isomer is 13f-syn, complementing the outcome of the alkylation reaction. The stereochemistry of the major diastereomer of 13a–h was assigned by comparing 1H NMR coupling constants. For product 13i, X-ray analysis showed a different major diastereomer from 13a–h. Furthermore, when (S)-ethyl mandelate was used to make anhydride 12, chiral HPLC analysis of the resulting 13i showed a racemic mixture of products. Although the synthesis of pentasubstituted γ-lactams is suitable for various alkyl substituents, the increased acidity of the α-H of 8d from the anion-stabilizing phenyl group makes this substrate susceptible to racemization.

Scheme 4.

Reaction of Disubstituted Anhydrides and Imines

‡ Reaction conditions: 1 equiv of 1, 1 equiv of 2, 1 equiv of 9–12, and 1.6 equiv of (EtO)3CH in THF (0.2 M) at 23 °C. After the removal of solvent, 4 equiv of CH3I and 4 equiv K2CO3 were added in acetone (0.05 M) at 23 °C. The dr is the ratio of the major diastereomer to the sum of the minor diastereomers. Ar = p-Cl-C6H4; PMP = p-CH3O-C6H4.

Figure 2.

X-ray crystal structures of lactams 13f and 13i

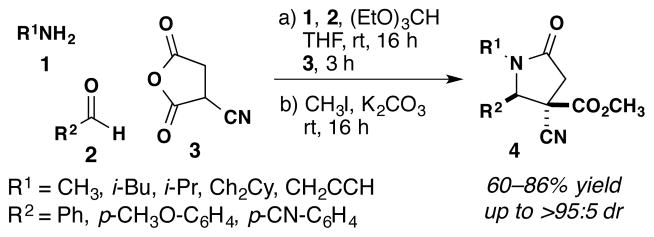

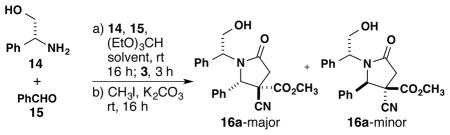

We next examined the possibility of asymmetric induction from imines derived from chiral amines to synthesize enantiopure γ-lactams. A range of solvents was screened to identify conditions for the reaction using cyanosuccinic anhydride 3 and the imine derived from (R)-phenylglycinol (14) and benzaldehyde (15) (Table 1). Although moderate yields and diastereomeric ratios (dr) of 16a were observed, only two out of the four possible products can be detected by 1H NMR analysis. This is consistent with the high diastereoselectivity of the imine-anhydride reaction even though the chiral induction of the imine N-substituent is variable. Further screening revealed that DMF and ethanol provided the highest selectivities and yields. Additional experiments using lower temperatures did not lead to improved dr.

Table 1.

Screening Reaction Conditions for Chiral Imines and Cyanosuccinic Anhydride

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | solvent | isolated yield | dra |

| 1 | THF | 54% | 65:35 |

| 2 | CH3CN | 30% | 76:24 |

| 3 | CHCl3 | 39% | 64:36 |

| 4 | toluene | 40% | 58:42 |

| 5 | DMF | 68% | 79:21 |

| 6 | ethanol | 69% | 75:25 |

Reaction conditions: see Scheme 4.

The dr is the ratio of the major diastereomer to the sum of the minor diastereomers.

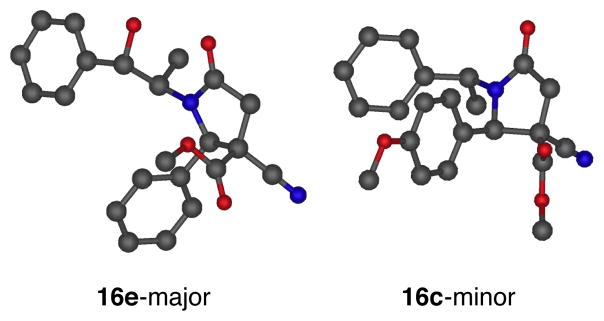

We determined the scope of the enantiopure synthesis of γ-lactams (Scheme 4). Using an (S)-α-methylbenzyl group on the nitrogen (16b–c), we observed a range of 74:26 to 81:19 dr. We found that in the absence of the alcohol moiety, the reaction proceeds in good yields and dr (16b–d) when tetrahydrofuran is used as the solvent. Other cleavable auxiliaries and larger groups (16e–h) gave similar yields and diastereoselectivities. The NH lactam can be obtained in high yield by cleaving the α-methyl-p-methoxybenzyl7 or 2-phenylethanol groups.8 Previous to these results, one example of asymmetric induction had been documented in the related synthesis of a substituted 2-quinolone from homophthalic anhydride.9 The absolute and relative stereochemistries of the diastereomers were unambiguously assigned by X-ray analyses4 of compounds 16e-major and 16c-minor (Figure 3). The stereochemistry of products 16a, 16b, and 16d–h has been assigned by comparing the 1H NMR coupling constants.

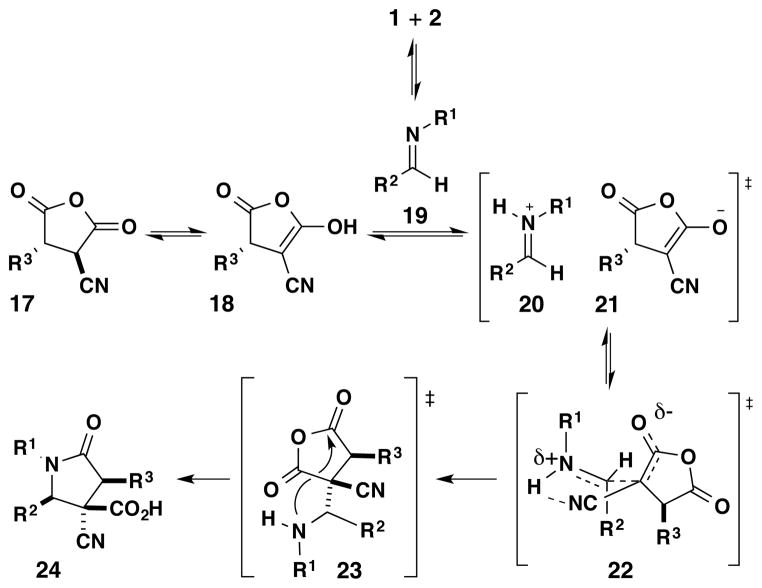

Figure 3.

X-ray crystal structure analyses of products 16e-major and 16c-minor from chiral imines

Unlike the previously proposed mechanisms of related imine-anhydride reactions which describe an iminolysis pathway,3b,3i our current mechanistic hypothesis involves a stepwise Mannich-acylation process (Scheme 6), involving the enol form 18 of the anhydride 17. Although there are only a few examples where anhydride enols have been reported as reactive intermediates,10 they have been studied computationally,11 observed crystallographically,12 and suggested as key intermediates in a related lactone-forming reaction.13 A proton transfer leads to the reactive iminium 20 and enolate 21 intermediates. The Mannich step occurs with high diastereoselectivity through the pseudo-Zimmerman-Traxler transition state 22 with intermolecular hydrogen bonding complexation. The formation of the Mannich adduct 23 is followed by a transacylation to form the γ-lactam product 24 with a β-carboxylic acid. This mechanistic picture emanates from extensive computational investigations.14

Scheme 6.

Proposed Mechanism for the Diastereoselective Reaction of Cyanosuccinic Anhydrides and Imines

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the imine-anhydride reaction using cyanosuccinic anhydrides is a robust method for the synthesis of a wide variety of highly substituted γ-lactams. The formation of the two new stereogenic centers can be controlled by chiral amines and chiral anhydrides, the latter leading to exquisite diastereoselectivity in three contiguous stereogenic centers.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 5.

Reaction of Chiral Imines and Cyanosuccinic Anhydride

‡ Reaction conditions: see Scheme 4. The dr is the ratio of the major diastereomer to the sum of the minor diastereomers.

*Reactions performed with THF as solvent instead of ethanol. PMP = p-CH3O-C6H4.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the NIH (NIGMS P41GM089153 and NCI R01CA131458), NSF (CAREER award CHE-0846189 for J.T.S.), UC Davis (Borge Graduate Fellowship, Volman Graduate Fellowship and Graduate Research Award for DQT), and Oregon State University (Vicki and Patrick F. Stone Scholar Award to PHYC and Ingram Fellowship to OP) for financial support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Experimental procedures, compound characterization data for all new compounds, X-ray data, and HPLC analysis. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Contributor Information

Paul Ha-Yeon Cheong, Email: paulc@science.oregonstate.edu.

Jared T. Shaw, Email: jtshaw@ucdavis.edu.

References

- 1.(a) Feling RH, Buchanan GO, Mincer TJ, Kauffman CA, Jensen PR, Fenical W. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:355. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kogure N, Ishii N, Kitajima M, Wongseripipatana S, Takayama H. Org Lett. 2006;8:3085. doi: 10.1021/ol061062i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kobayashi Ji, Inaba Y, Shiro M, Yoshida N, Morita H. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:11402. doi: 10.1021/ja016955e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Dawadi PBS, Lugtenburg J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:2508. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hashmi ASK, Yang W, Yu Y, Hansmann MM, Rudolph M, Rominger F. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;52:1329. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liberge G, Lebrun S, Couture A, Grandclaudon P. Helv Chim Acta. 2011;94:1662. [Google Scholar]; (d) Miyabe H, Asada R, Takemoto Y. Org Biomol Chem. 2012;10:3519. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25073j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Pelletier SMC, Ray PC, Dixon DJ. Org Lett. 2011;13:6406. doi: 10.1021/ol202710g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Peng H, Liu G. Org Lett. 2011;13:772. doi: 10.1021/ol103039x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Roy S, Reiser O. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:4722. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Tekkam S, Alam MA, Jonnalagadda SC, Mereddy VR. Chem Commun. 2011;47:3219. doi: 10.1039/c0cc05609j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Yokosaka T, Hamajima A, Nemoto T, Hamada Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:1245. [Google Scholar]; (j) Zhao X, DiRocco DA, Rovis T. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12466. doi: 10.1021/ja205714g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Gonzalez-Lopez M, Shaw JT. Chem Rev. 2009;109:164. doi: 10.1021/cr8002714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ng PY, Masse CE, Shaw JT. Org Lett. 2006;8:3999. doi: 10.1021/ol061473z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ng PY, Tang YC, Knosp WM, Stadler HS, Shaw JT. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:5352. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tan DQ, Atherton AL, Smith AJ, Soldi C, Hurley KA, Fettinger JC, Shaw JT. ACS Comb Sci. 2012;14:218. doi: 10.1021/co2001873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Tang Y, Fettinger JC, Shaw JT. Org Lett. 2009;11:3802. doi: 10.1021/ol901018k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Castagnoli N, Cushman M. J Org Chem. 1971;36:3404. doi: 10.1021/jo00821a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Castagnoli N. J Org Chem. 1969;34:3187. doi: 10.1021/jo01262a081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Cushman M, Castagnoli N. J Org Chem. 1973;38:440. doi: 10.1021/jo00943a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Cushman M, Madaj EJ. J Org Chem. 1987;52:907. [Google Scholar]

- 4.CCDC 916580–916584 and 934180 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

- 5.Otera J, Nakazawa K, Sekoguchi K, Orita A. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:13633. [Google Scholar]

- 6.See Supporting Information.

- 7.Galeazzi R, Martelli G, Marcucci E, Mobbili G, Natali D, Orena M, Rinaldi S. Eur J Org Chem. 2007;2007:4402. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Semak V, Escolano C, Arróniz C, Bosch J, Amat M. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2010;21:2542. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cushman M, Chen J. J Org Chem. 1987;52:1517. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Tamura Y, Wada A, Sasho M, Kita Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:4283. [Google Scholar]; (b) Brown HC, Dhar RK, Ganesan K, Singaram B. J Org Chem. 1992;57:499. [Google Scholar]; (c) Goff JM, Justik MW, Koser GF. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:5597. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rappoport Z, Lei YX, Yamataka H. Helv Chim Acta. 2001;84:1405. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song JH, Lei YX, Rappoport Z. J Org Chem. 2007;72:9152. doi: 10.1021/jo071206m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Cornaggia C, Manoni F, Torrente E, Tallon S, Connon SJ. Org Lett. 2012;14:1850. doi: 10.1021/ol300453s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Manoni F, Cornaggia C, Murray J, Tallon S, Connon SJ. Chem Commun. 2012;48:6502. doi: 10.1039/c2cc32147e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pattawong O, Tan DQ, Fettinger JC, Shaw JT, Cheong PH-Y. Org Lett. 2013 doi: 10.1021/ol402561q. next paper in this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.