Abstract

Exercising during pregnancy has been shown to improve spatial learning and short-term memory, as well as increase BDNF mRNA levels and hippocampal cell survival in juvenile offspring. However, it remains unknown if these effects endure into adulthood. In addition, few studies have considered how maternal exercise can impact cognitive functions that do not rely on the hippocampus. To address these issues, the present study tested the effects of maternal exercise during pregnancy on object recognition memory, which relies on the perirhinal cortex (PER), in adult offspring. Pregnant rats were given access to a running wheel throughout gestation and the adult male offspring were subsequently tested in an object recognition memory task at three different time points, each spaced 2-weeks apart, beginning at 60 days of age. At each time point, offspring from exercising mothers were able to successfully discriminate between novel and familiar objects in that they spent more time exploring the novel object than the familiar object. The offspring of non-exercising mothers were not able to successfully discriminate between objects and spent an equal amount of time with both objects. A subset of rats was euthanized 1 hr after the final object recognition test to assess c-FOS expression in the PER. The offspring of exercising mothers had more c-FOS expression in the PER than the offspring of non-exercising mothers. By comparison, c-FOS levels in the adjacent auditory cortex did not differ between groups. These results indicate that maternal exercise during pregnancy can improve object recognition memory in adult male offspring and increase c-FOS expression in the PER; suggesting that exercise during the gestational period may enhance brain function of the offspring.

1. INTRODUCTION

Substantial research has established that exercise can improve both mental health and cognitive function. In laboratory animals, most research on the cognitive enhancing effects of exercise has primarily focused on how exercise improves spatial learning (Vaynman et al., 2004; Albeck et al., 2006). The improvements in spatial learning likely occur as a result of exercise-induced changes in the hippocampus, such as increased neurogenesis (van Praag et al., 1999), enhanced long-term potentiation (van Praag et al., 1999; Farmer et al., 2004; O'Callaghan et al., 2007), and increased expression of neurotrophic factors (Trejo et al., 2001; Fabel et al., 2003; Vaynman et al., 2004; Adlard et al., 2005; Berchtold et al., 2005; Griffin et al., 2009). Specifically, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) has been established as the putative substrate that underlies many of the exercise related improvements in hippocampal function (Dishman et al., 2006). For example, an exercise-induced increase in hippocampal BDNF levels has been shown to be necessary for improvements in spatial learning in the Morris water maze following exercise (Vaynman et al., 2004).

More recent studies have shown that physical exercise can also improve non-spatial forms of learning and memory that rely on structures other than the hippocampus. For instance, exercise has been found to improve associative learning (Van Hoomissen et al., 2004; Burghardt et al., 2006; Eisenstein & Holmes, 2007) as well as object recognition memory (O'Callaghan et al., 2007; Fahey et al., 2008; Griffin et al., 2009; Hopkins & Bucci, 2010; Hopkins et al., 2011). Object recognition is a non-spatial form of memory that depends on the perirhinal cortex (PER; Dere et al., 2007) and is based on the spontaneous tendency of rodents to spend more time exploring a novel object than a familiar one. Compared to sedentary rats, those that had access to a running wheel exhibited enhanced object recognition memory, an effect that could not be attributed simply to changes in general exploratory behavior (Hopkins & Bucci, 2010; Hopkins et al., 2011). Moreover, enhanced object recognition memory was associated with increases in BDNF expression in PER but not in the hippocampus of rats that exercised (Hopkins & Bucci, 2010).

Although the effects of exercise on the adult brain have been well documented, less is known about the effects of exercise on the developing brain. Brain development starts in utero and continues until at least the end of the adolescent period (Rice & Barone, 2000). Throughout this developmental process the brain can readily be affected by internal and external factors. Notably, exercise has been found to have more robust and long-lasting effects on both the brain and behavior when rats exercise as juveniles rather than as adults. For example, rats that exercised during adolescence had greater increases in cell proliferation (Kim et al., 2004), BDNF expression (Adlard et al., 2005; Hopkins et al., 2011), and object recognition memory (Hopkins et al., 2011) than adult exercisers. In addition, in the rats that exercised as adolescents, the exercise-induced improvements in behavior lasted long after exercise stopped, while in adults the effects did not persist (Hopkins et al, 2011).

Similarly, a growing number of studies have reported that regular physical exercise during pregnancy can enhance cognition and behavior in the offspring. Exercise by pregnant rats has been found to improve spatial learning (Parnpiansil et al., 2003; Akhavan et al., 2008; Dayi et al., 2012) and short-term memory (Kim et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2006) in juvenile offspring, as well as increase BDNF mRNA levels and hippocampal cell survival (Lee et al., 2006). In addition, regular aerobic exercise during pregnancy decreases anxiety-like behavior in offspring (Aksu et al., 2012). However, little work has been done to determine how long the effects of maternal exercise during pregnancy endure in the offspring. Indeed, most studies that have examined the effects of maternal exercise on offspring have tested pups soon after birth or during adolescence, thus it remains unknown if these effects endure into adulthood. In addition, few studies have focused on how maternal exercise can impact cognitive functions that do not rely on the hippocampus. To address these issues, the present study tested the effects of maternal exercise during pregnancy on object recognition memory in adult offspring. Pregnant rats were given access to a running wheel throughout gestation and the adult male offspring were subsequently tested in an object recognition memory task at three different time points, spaced 2-weeks apart. In addition, c-FOS expression was measured in the PER of the offspring after the final recognition memory test to determine if there were differences in neuronal activity related to recognition memory.

2. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

2.1 Subjects

Male (N=2) and female (N=5) Long Evans rats weighing approximately 250–300g were obtained from Harlan Laboratories, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN, USA) and allowed to mate (2 females and 1 male per cage) during a 72-hour period. After the 72-hr period, female rats were assigned to either exercise (N=2) or sedentary conditions (N=3). Rats were checked for birth daily and the day pups were first observed was designated postnatal day 0 (PND 0). Rats were weaned at PND 21 and group housed according to sex and condition. Eleven (EX group) and ten (NX group) male offspring were used in this study. Rats had free access to food (Purina standard rat chow: Nestle Purina, St. Louis, MO, USA) and water and were maintained on a 14:10 light-dark cycle throughout the study. Behavioral testing took place at approximately 1pm. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care Guidelines and the Dartmouth College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2 Physical exercise regimen

Pregnant rats in the exercise group had 24 hour access to a stainless steel running wheel (34.5 cm diameter, 1.3 mm rods placed 0.9 cm apart; Philips Respironics, Bend, OR, USA) inside the home cage throughout pregnancy. Wheel rotations were monitored by an automatic counter mounted on the side of the apparatus. The counters recorded every 1/2 turn of the running wheel and nightly running distance was calculated by dividing the count by 2 and multiplying by 1.08 to convert to meters. The running wheel was removed from the cage once the pups were born.

2.3 Novel object recognition

Object recognition memory was assessed in a plastic tub (30×34 cm with 38 cm high walls) that was monitored by a video camera and located in a dimly lit room. One set of test objects was made of plastic building blocks (Learning Resources Inc., Vernon Hills, IL) constructed into distinct configurations with approximately the same dimensions. One of the objects was purple and roughly similar in shape to a dumbbell and the other was green and shaped like a cross. The second set of objects was made of glass and one object resembled a small red cup and the other a blue ashtray. The third set of objects included a red magnet and a large bolt, which were both approximately 6 cm long. The first set of objects that rats were exposed to was always the plastic objects, the second set was always the glass objects, and the third set was always the magnet/bolt.

Behavioral testing began when the male offspring were approximately 60 days old. Rats were tested in a novel object recognition paradigm that was designed to minimize spatial learning and hippocampal involvement (Bevins & Besheer, 2006; Dere et al., 2007). Indeed, rats exhibit impaired performance in this task following lesions of the PER (Bussey et al., 1999; Forwood et al., 2005; Mumby et al., 2007; Aggleton et al., 2007; Warburton and Brown, 2010) but not after hippocampal lesions (Brown & Aggleton, 2001; Winters et al., 2008; Warburton & Brown, 2010; Kealy & Commins, 2011). Moreover, the difficult training procedure (i.e., long sample-test interval and short sample session) was intentionally chosen so that a categorical distinction could be made between exercising and non-exercising groups (Hopkins & Bucci, 2010). On day 1 (habituation session) each rat was exposed to the tub individually for 10 min to habituate to the testing environment. On day 2 (sample session), rats were placed in the tub and given 5 min to explore two identical sample objects. Twenty-four hours later (test session), rats were again placed in the tub with one familiar and one novel object (counter-balanced across subjects) and given 2 min to investigate the items. Two-weeks later, rats were tested with a second set of objects. Finally, after an additional two-week period, a subset of rats (n=5/group; distributed across litters) were tested with a third set of objects and sacrificed afterwards so that brains could be processed for c-Fos immunocytochemistry (see below). The remaining rats in each group were used in a different study and did not undergo the third novel object memory session.

As described previously (Hopkins & Bucci, 2010; Hopkins et al., 2011), an observer who was blind to the experimental condition scored the time the rats spent exploring each object. Exploration was defined as direct sniffing or snout contact with the object. The mean time spent exploring the identical objects during the sample session was analyzed using a two-sample t-test (α=0.05). For the test session data, a discrimination ratio served as the dependent variable of interest and was calculated as the time spent exploring the novel object divided by total time spent exploring both objects. This measure takes into account individual differences in total exploratory behavior. A one-sample t-test (expected value=0.5; α=0.05) was used to determine whether each group was able to successfully discriminate between the two objects and an independent-sample t-test was used to compare the discrimination ratios of the exercise and no-exercise groups to each other (α=0.05).

2.4 Immunohistochemistry and cell counting

Offspring that were tested with a third set of objects were sacrificed one hour after the test session in order to measure c-FOS expression in the PER. Rats were perfused transcardially with 0.9% saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Upon removal, brains were placed in fixative overnight and subsequently placed in a solution of 30% sucrose in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 4 d and frozen at −80°C until sectioning. Free-floating sections (60 µm thick, 3 sections per rat;) containing PER [~6.0 mm posterior to bregma according to the rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (2007)] were cut with a freezing microtome and incubated in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in PBS for 10 min, rinsed in PBS, and then blocked for 1 h in immunobuffer (IB) containing 2% normal goat serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C in IB containing primary rabbit polyclonal c-FOS antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-52; lot no. C1110; 1:5,000 dilution). After rinses in PBS, sections were incubated for 2 h in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary IgG (Vector Laboratories), rinsed, and incubated for 30 min in avidin–biotin complex (ABC Vectastain Kit; Vector). Chromagen immunostaining was visualized using a diaminobenzidine kit (Vector).

Sections were slide-mounted and examined by an observer blind to the behavioral condition using an Axioskope I microscope (Zeiss) connected to a computer equipped with StereoInvestigator software (version 9.0; MicroBrightField). FOS-positive cells in PER were counted from both the left and right hemispheres from two region-matched sections from each rat. As a control, cells from the adjacent auditory cortex (Au1) were also counted in the same sections. A contour was drawn at 2.5x magnification to outline the boundaries of PER or Au1 according to the rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (2007). Cell counting was then conducted at 20x magnification using the MeanderScan tool in StereoInvestigator, in which a counting frame (0.3 – 0.35 mm) was placed within the boundaries of the target area and advanced systematically through the region. The number of FOS-positive cells in a counting frame was determined using a planometric analysis, which measures the luminance of the object. To be counted, a cell must be 33% darker than surrounding background staining on that section (Robinson et al., 2012; Bucci & MacLeod, 2007). Each cell that reached criterion was marked in StereoInvestigator to ensure that cells are only counted once.

To analyze immunohistochemistry data, c-FOS-positive cell counts collected from each rat were averaged to produce a single value and then an independent-sample t-test was performed on data from the exercise and non-exercise groups. In addition, a Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated using the data from both groups of rats to test for a relationship between object recognition memory and Fos expression. An α value of 0.05 was adopted for all analyses.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Wheel running

Rats in the exercise group ran an average of ~0.76 km (+/− 0.09 km) per night during gestation. This distance was comparable to the distance run by pregnant rats in other studies (Akhavan et al., 2008).

3.2 Novel object recognition

As shown in Table 1, rats from exercising and non-exercising mothers exhibited comparable amounts of time exploring the objects during the sample phase (first set of objects, p > 0.1; second set of objects, p > 0.6; third set of objects, p > 0.5). Thus, there were no group differences in general exploratory behavior at any time point in the experiment.

Table 1.

Exploration time(s) during the sample and test sessions of the novel object recognition task

| Sample session | Test session | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Familiar object | Novel object | ||

| 1st set of objects | EX 51.5 ± 6.1 | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 13.0 ± 1.5 |

| NX 61.3 ± 3.1 | 10.1 ± 1.4 | 13.2 ± 2.1 | |

| 2nd set of objects | EX 24.3 ± 3.7 | 6.1 ± 1.0 | 9.1 ± 0.9 |

| NX 27.0 ± 3.6 | 6.16 ± 1.4 | 6.15 ± 0.9 | |

| 3rd set of objects | EX 14.1 ± 3.0 | 1.99 ± 0.8 | 4.2 ± 1.6 |

| NX 18.9 ± 5.8 | 4.1 ± 1.6 | 2.9 ± 1.3 | |

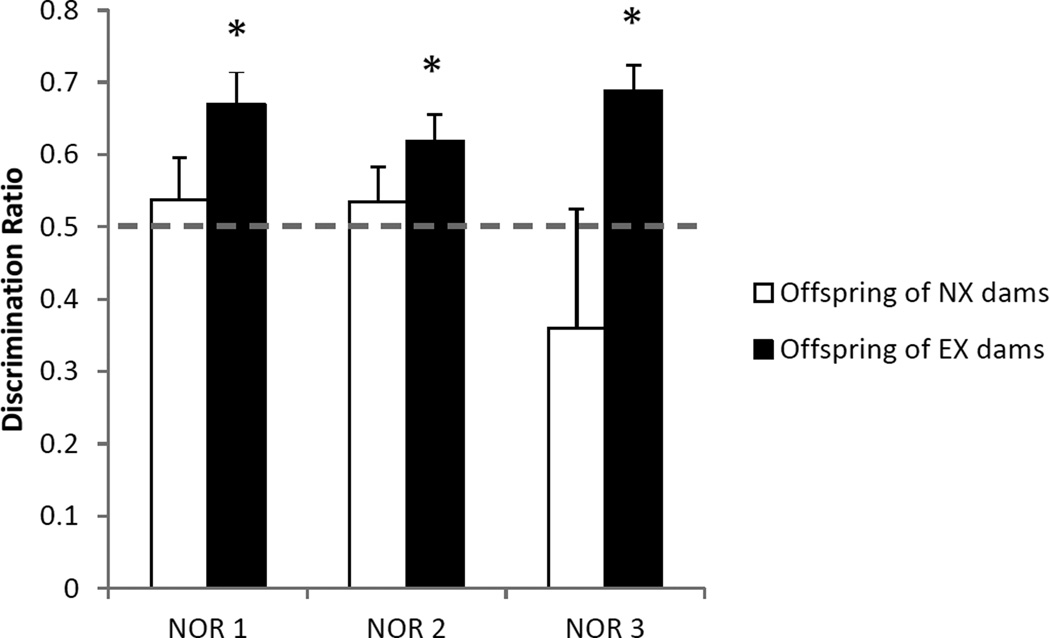

The discrimination ratios during the object recognition test sessions are illustrated in Figure 1. During the first test session, rats whose mothers were in the exercise group successfully discriminated between the novel and familiar items [t(10) = 3.9, p < 0.003]. In contrast, rats from non-exercising mothers did not discriminate between the objects (p > 0.5). Moreover, the mean discrimination ratio for the exercising group was higher than that of the non-exercising group but did not quite reach statistical significance [t(19) = 1.9, p < 0.07]. When the novel object task was repeated with a new set of objects 2 weeks later (Figure 1), rats from exercising mothers again discriminated between the novel and familiar objects [t(10) = 3.1, p < 0.01] and rats from nonexercising mothers did not (p > 0.5). There was no group difference in the discrimination ratios (p < 0.1). Finally, when a subset of rats completed the novel object task with a third set of objects 2 weeks after the second set, rats from exercising mothers discriminated between the novel and familiar objects [t(3) = 5.5, p < 0.02] and rats from non-exercising mothers did not (p > 0.4). The raw exploration times during the test sessions are shown in Table 1. Note that because of a technical difficulty during the third test sessions, the data from one rat in the EX group was excluded from the study.

Figure 1.

Novel object recognition (NOR). The data are the average discrimination ratios (±SEM) for each group, calculated as the time spent exploring the novel object divided by total time spent exploring both objects. Adult offspring from exercising mothers successfully discriminated between the novel and familiar objects during each of the 3 test sessions while offspring from non-exercising rats did not discriminate between the objects. Solid bars represent data from the offspring of exercising mothers and open bars represent data from the offspring of non-exercising mothers. Data are average discrimination ratios ±SEM. *indicates significant discrimination (p<0.05).

3.3 Immunohistochemistry

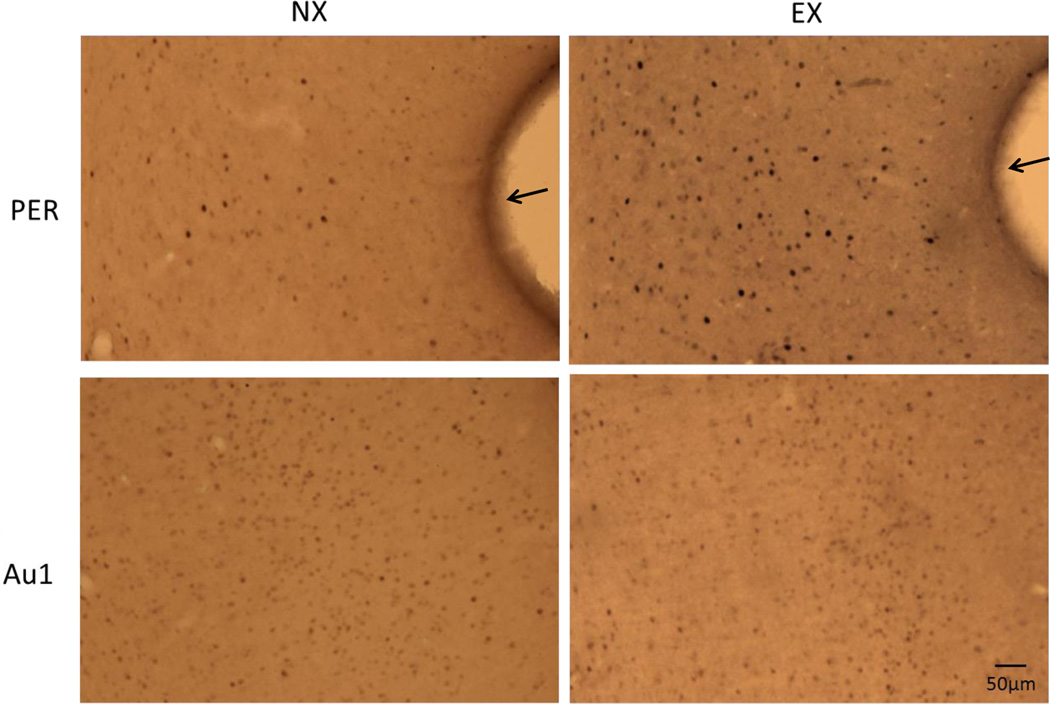

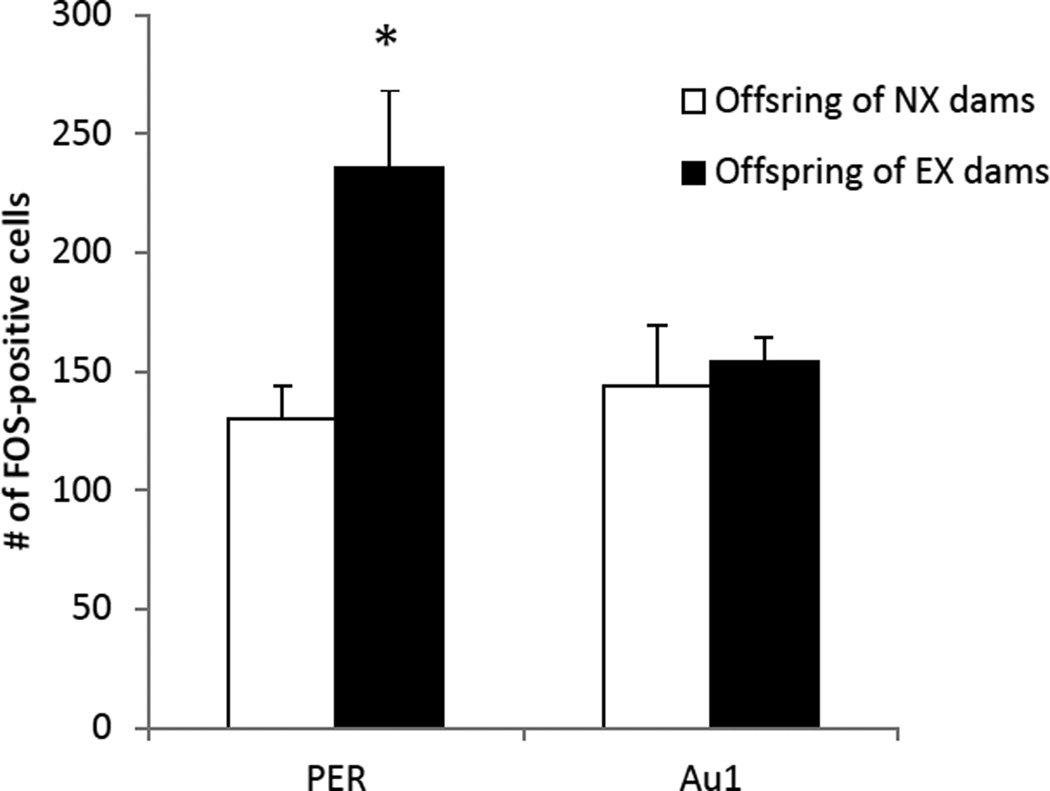

An example of FOS staining in the PER and Au1 of the offspring of exercising and non-exercising mothers is shown in Figure 2. The number of nuclei that were immunoreactive for c-FOS in the PER of the EX group was significantly higher compared with the NX group [t(8) = 3.7, p < 0.006] as illustrated in Figure 3. In contrast, c-FOS expression in Au1 did not differ between the two groups [t(8) = 1.02, p > 0.34]. In addition, there was a trend towards a positive correlation between the discrimination ratio during the third novel object recognition task and c-FOS expression in the PER (r2 = 0.6, p < 0.08), but not between the discrimination ratios and cell counts in the Au1 (r2 = 0.3, p > 0.4)

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs of c-FOS protein expression in the PER and Au1 of the offspring of an exercising mother and the offspring of a non-exercising mother. The rhinal fissure in the PER panels is indicated by the black arrows. PER=perirhinal cortex; Au1=auditory cortex; NX=offspring of non-exercising mothers; EX=offspring of exercising mothers.

Figure 3.

The number of FOS positive cells in the PER and Au1 after the third test of novel object recognition. The offspring of exercising mothers had significantly more FOS positive cells in the PER than the offspring of non-exercising mothers (*p < 0.01). Data are means ± SEM

4. DISCUSSION

The present study was designed to determine whether maternal exercise during pregnancy could improve a non-spatial, non-hippocampal-dependent form of memory in adult offspring. Pregnant rats in the exercise condition were given access to a running wheel throughout gestation and adult male offspring were subsequently tested in a perirhinal cortex-dependent object recognition memory task at three different time points, spaced 2-weeks apart. We found that exercise during gestation improved object recognition memory in the offspring. In particular, rats from exercising mothers successfully discriminated between the novel and familiar items at each time point whereas rats from non-exercising mothers did not. These results could not be attributed to exercise-induced changes in locomotor activity or exploratory behavior because there were no differences observed between the groups during the sample sessions.

Because a difficult testing protocol was utilized (a short sample exposure and a long interval between the sample and choice sessions) it is not surprising that rats from non-exercising mothers did not discriminate between novel and familiar objects. By adjusting the parameters in this way, we are able to make a categorical distinction between the groups, based on whether they are able to successfully discriminate the objects or not. This is consistent with other studies that have utilized similar training and testing parameters and found rats in the control group did not exhibit discrimination between the objects (Hopkins & Bucci, 2010; Griffin et al., 2009). At the same time, other studies have demonstrated that the effects of exercise can still be detected even when the non-exercising group does exhibit successful discrimination (Hopkins et al., 2011; Robinson & Bucci, 2013), making unlikely that the present finding merely reflect a false-positive result.

In addition to demonstrating that exercising during pregnancy affects a non-hippocampal dependent form of memory, the current data provide some of the first evidence that the cognitive enhancing effects endure into adulthood. Indeed, prior studies have primarily focused on the effects of exercise during pregnancy on the behavior of juvenile offspring (Kim et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2006; Akhavan et al., 2008; Parnpiansil et al., 2003). In the few studies that have tested adult offspring, it has been shown that the offspring of exercising mothers had decreased anxiety levels (Aksu et al., 2012) and improved spatial learning (Dayi et al., 2012) compared to offspring from nonexercising mothers. Adult offspring from exercising mothers also had increased prefrontal BDNF and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) levels (Aksu et al., 2012) and enhanced hippocampal neurogenesis and leptin receptor expression (Dayi et al., 2012). Similar to these findings, the present study showed that maternal exercise during pregnancy improved object memory in adult offspring. In addition, we were interested in examining how long the effects of maternal exercise lasted in the adult offspring, thus rats were tested in novel object recognition at three time points, spaced 2-weeks apart. At each time point, offspring from exercising mothers exhibited enhanced object recognition, suggesting the effects of maternal exercise persist in the adult offspring until at least PND 88. Future studies are needed to determine whether these effects are permanent or if they dissipate over longer time periods.

After the final test of object recognition, rats were sacrificed and c-FOS expression was measured in the PER cortex. Rats from exercising mothers had more c-FOS expression in the PER than rats from non-exercising mothers. One possible explanation for this finding is that rats from exercising mothers had higher levels of basal activity throughout the brain. However, that does not appear to be the case since there were no differences in c-FOS expression in the adjacent Au1. Instead, exercise may serve to ‘prime' neural function in the offspring such that when cells are activated in a task specific fashion there is an increase in activity compared to the non-exercising condition. Indeed, c-FOS expression in PER is a reliable marker of changes in neuronal activity related to recognition memory (Zhu et al., 1995b, 1996; Wan et al., 1999, 2004; Warburton et al., 2003, 2005; Albasser et al., 2010; Seoane et al., 2012). This notion is supported by the finding that exercise facilitates long-term potentiation (van Praag et al., 1999), which may reflect a form of cellular priming that can modulate neural plasticity and memory formation (Hopkins et al., 2012).

Similar to our findings, other studies have found improved learning and memory in the offspring of mothers that exercised during pregnancy (Parnpiansil et al., 2003; Akhavan et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2006). However, the mechanism by which maternal exercise affects cognitive function in the offspring remains uncertain. Studies have found that maternal exercise during gestation increases BDNF and neurogenesis in the hippocampus of the offspring (Parnpiansil et al., 2003; Bick-Sander et al., 2006), which may be mediated through serotonergic and noradrenergic signaling (Akhavan et al., 2008). Elimination of noradrenergic or serotonergic neurotransmission significantly attenuated the positive effects of maternal exercise during pregnancy when the offspring were tested in the Morris water maze, while it did not affect learning and memory in the offspring from non-exercising mothers. Indeed, other studies have revealed the important role of the noradrenergic and serotonergic system in mediating the effects of exercise-induced BDNF expression (Garcia et al., 2003; Ivy et al., 2003; Klempin et al., 2013) and activation of these systems have also been linked to enhanced consolidation of object recognition memory (Roozendaal et al., 2008; Lamirault & Simon, 2001). Thus, exercise during gestation could affect recognition memory in the offspring through serotonergic and noradrenergic systems.

Another possible mechanism mediating the beneficial effects of maternal exercise on the offspring is the influence of exercise on maternal behavior. Indeed, stress-induced differences in maternal behavior have been shown to produce depressive symptoms in offspring (Smith et al., 2004). Because exercise has been shown to decrease stress and anxiety-like behavior in rats (Fulk et al., 2004; Hopkins & Bucci, 2010) exercise during the gestational period may improve subsequent care of the young. Moreover, maternal care during the first week of life can have long-lasting effects on the behavior of offspring through changes in the epigenome (Weaver et al., 2004; Fish et al., 2004). Thus, the present results could be due to exercise-related changes in maternal behavior rather than a direct transfer of the effects of exercise across the placental or mammary barrier. Future studies could cross-foster pups from exercising and nonexercising mothers to determine if the beneficial effects on the offspring are mediated by changes in maternal behavior.

A potential confound in the present study is that a relatively small number of litters were used. Indeed, animals from the same litter are often more alike compared with those from different litters because they are genetically more similar and share prenatal and early postnatal environments (Lazic & Essioux, 2013). Thus, it is possible that chance variations between litters could account for the finding that the offspring of exercising mothers discriminated between novel and familiar objects while the offspring of non-exercising mothers did not. However, several other studies have also found that maternal exercise impacts learning and memory in offspring (Parnpiansil et al., 2003; Akhavan et al., 2008; Dayi et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2006), making it less likely that the present results merely reflect chance differences between litters. Nevertheless, it will be useful to extend the present results by examining the effects of maternal exercise in larger litters as well as in different strains and species (e.g., mice as well as rats). Similarly, more extensive analysis of FOS expression throughout regions such as hippocampus and elsewhere will be valuable to determine more precisely how exercise alters brain function in offspring.

In conclusion, the adult offspring of mothers that exercised exhibited improvements in a non-spatial, non-hippocampal-dependent memory task. The offspring of exercising mothers also had increased c-FOS expression in the PER, suggesting that exercise during the gestational period may enhance brain function of the offspring. In addition, these findings are among the first to show that the cognitive-enhancing effects of maternal exercise on the offspring persist into adulthood and that the effects are durable over time. These results also suggest that exercising during peak developmental time points may lead to more long lasting and durable effects on cognitive function.

Exercising during pregnancy enhanced object recognition memory in adult offspring

Enhanced memory was associated with an increase in c-FOS expression in perirhinal cortex

The effects of exercise in the offspring persisted across 3 different testing time points

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFRENCES

- Adlard PA, Perreau VM, Pop V, Cotman CW. Voluntary exercise decreases amyloid load in a transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4217–4221. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0496-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggleton JP, Sanderson DJ, Pearce JM. Structural learning and the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2007;17:723–734. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhavan MM, Emami-Abarghoie M, Safari M, Sadighi-Moghaddam B, Vafaei AA, Bandegi AR, Rashidy-Pour A. Serotonergic and noradrenergic lesions suppress the enhancing effect of maternal exercise during pregnancy on learning and memory in rat pups. Neuroscience. 2008;151(4):1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aksu I, Baykara B, Ozbal S, Cetin F, Sisman AR, Dayi A, Uysal N. Maternal treadmill exercise during pregnancy decreases anxiety and increases prefrontal cortex VEGF and BDNF levels of rat pups in early and late periods of life. Neurosci Lett. 2012;516(2):221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.03.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albasser MM, Poirier GL, Aggleton JP. Qualitatively different modes of perirhinal–hippocampal engagement when rats explore novel vs. familiar objects as revealed by c-Fos imaging. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31(1):134–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albeck DS, Sano K, Prewitt GE, Dalton L. Mild forced treadmill exercise enhances spatial learning in the aged rat. Behav Brain Res. 2006;168(2):345–348. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berchtold NC, Chinn G, Chou M, Kesslak JP, Cotman CW. Exercise primes a molecular memory for brain-derived neurotrophic factor protein induction in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2005;133(3):853–861. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevins RA, Besheer J. Object recognition in rats and mice: a one-trial non-matching-to-sample learning task to study'recognition memory'. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(3):1306–1311. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bick-Sander A, Steiner B, Wolf SA, Babu H, Kempermann G. Running in pregnancy transiently increases postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in the offspring. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(10):3852–3857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502644103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MW, Aggleton JP. Recognition memory: what are the roles of the perirhinal cortex and hippocampus? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(1):51–61. doi: 10.1038/35049064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci DJ, MacLeod JE. Changes in neural activity associated with a surprising change in the predictive validity of a conditioned stimulus. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26(9):2669–2676. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burghardt PR, Pasumarthi RK, Wilson MA, Fadel J. Alterations in fear conditioning and amygdalar activation following chronic wheel running in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Beh. 2006;84(2):306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussey TJ, Muir JL, Aggleton JP. Functionally dissociating aspects of event memory: the effects of combined perirhinal and postrhinal cortex lesions on object and place memory in the rat. J Neurosci. 1999;19(1):495–502. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00495.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayi A, Agilkaya S, Ozbal S, Cetin F, Aksu I, Gencoglu C, Uysal N. Maternal aerobic exercise during pregnancy can increase spatial learning by affecting leptin expression on offspring's early and late period in life depending on gender. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012 doi: 10.1100/2012/429803. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dere E, Huston JP, De Souza Silve MA. The pharmacology, neuroanatomy and neurogenetics of one-trial object recognition in rodents. Neurosci Biobeh R. 2007;31(5):673–704. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishman RK, Berthoud HR, Booth FW, Cotman CW, Edgerton VR, Fleshner MR, Zigmond MJ. Neurobiology of exercise. Obesity. 2006;14(3):345–356. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein SA, Holmes PV. Chronic and voluntary exercise enhances learning of conditioned place preference to morphine in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Beh. 2007;86(4):607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey B, Barlow S, Day JS, O'Mara SM. Interferon-a-induced deficits in novel object recognition are rescued by chronic exercise. Physiol Behav. 2008;95(1):125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer J, Zhao XV, Van Praag H, Wodtke K, Gage FH, Christie BR. Effects of voluntary exercise on synaptic plasticity and gene expression in the dentate gyrus of adult male sprague–dawley rats in vivo. Neuroscience. 2004;124(1):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish EW, Shahrokh D, Bagot R, Caldji C, Bredy T, Szyf M, Meaney MJ. Epigenetic programming of stress responses through variations in maternal care. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1036(1):167–180. doi: 10.1196/annals.1330.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forwood SE, Winters BD, Bussey TJ. Hippocampal lesions that abolish spatial maze performance spare object recognition memory at delays of up to 48 hours. Hippocampus. 2005;15(3):347–355. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulk LJ, Stock HS, Lynn A, Marshall J, Wilson MA, Hand GA. Chronic physical exercise reduces anxiety-like behavior in rats. Int J Sports Med. 2004;25(01):78–82. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-45235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia C, Chen MJ, Garza AA, Cotman CW, Russo-Neustadt A. The influence of specific noradrenergic and serotonergic lesions on the expression of hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor transcripts following voluntary physical activity. Neuroscience. 2003;119(3):721–732. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin EW, Bechara RG, Birch AM, Kelly ÁM. Exercise enhances hippocampal-dependent learning in the rat: Evidence for a BDNF-related mechanism. Hippocampu. 2009;19(10):973–980. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins ME, Bucci DJ. BDNF expression in perirhinal cortex is associated with exercise-induced improvement in object recognition memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2010;94(2):278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins ME, Nitecki R, Bucci DJ. Physical exercise during adolescence versus adulthood: differential effects on object recognition memory and brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels. Neuroscience. 2011;194:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.07.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins ME, Davis FC, VanTieghem M, Whalen PJ, Bucci DJ. Differential effects of acute and regular physical exercise on cognition and affect. Neuroscience. 2012;215:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.04.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivy AS, Rodriguez FG, Garcia C, Chen MJ, Russo-Neustadt AA. Noradrenergic and serotonergic blockade inhibits BDNF mRNA activation following exercise and antidepressant. Pharmacol Biochem Beh. 2003;75(1):81–88. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kealy J, Commins S. The rat perirhinal cortex: A review of anatomy, physiology, plasticity, and function. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;93(4):522–548. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YP, Kim H, Shin MS, Chang HK, Jang MH, Shin MC, Kim CJ. Age-dependence of the effect of treadmill exercise on cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus of rats. Neurosci Lett. 2004;355(1):152–154. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Lee SH, Kim SS, Yoo JH, Kim CJ. The influence of maternal treadmill running during pregnancy on short-term memory and hippocampal cell survival in rat pups. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2007;25(4):243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klempin F, Beis D, Mosienko V, Kempermann G, Bader M, Alenina N. Serotonin Is Required for Exercise-Induced Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. J Neurosci. 2013;33(19):8270–8275. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5855-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamirault L, Simon H. Enhancement of place and object recognition memory in young adult and old rats by RS 67333, a partial agonist of 5-HT4 receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41(7):844–853. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazic SE, Essioux L. Improving basic and translational science by accounting for litter-to-litter variation in animal models. BMC Neurosci. 2013;14:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-14-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HH, Kim H, Lee JW, Kim YS, Yang HY, Chang HK, Kim CJ. Maternal swimming during pregnancy enhances short-term memory and neurogenesis in the hippocampus of rat pups. Brain and Dev. 2006;28(3):147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumby DG, Piterkin P, Lecluse V, Lehmann H. Perirhinal cortex damage and anterograde object-recognition in rats after long retention intervals. Behav Brain Res. 2007;185(2):82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan RM, Ohle R, Kelly ÁM. The effects of forced exercise on hippocampal plasticity in the rat: A comparison of LTP, spatial-and non-spatial learning. Behav Brain Res. 2007;176(2):362–366. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnpiansil P, Jutapakdeegul N, Chentanez T, Kotchabhakdi N. Exercise during pregnancy increases hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA expression and spatial learning in neonatal rat pup. Neurosci Lett. 2003;352(1):45–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Australia: Academic, Sydney; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rice D, Barone S., Jr Critical periods of vulnerability for the developing nervous system: evidence from humans and animal models. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:511–533. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S, Poorman CE, Marder TJ, Bucci DJ. Identification of functional circuitry between retrosplenial and postrhinal cortices during fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 2012;32(35):12076–12086. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2814-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, Castello NA, Vedana G, Barsegyan A, McGaugh JL. Noradrenergic activation of the basolateral amygdala modulates consolidation of object recognition memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;90(3):576–579. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seoane A, Tinsley CJ, Brown MW. Interfering with Fos expression in rat perirhinal cortex impairs recognition memory. Hippocampus. 2012;22(11):2101–2113. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JW, Seckl JR, Evans AT, Costall B, Smythe JW. Gestational stress induces post-partum depression-like behaviour and alters maternal care in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29(2):227–244. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trejo JL, Carro E, Torres-Alemán I. Circulating insulin-like growth factor I mediates exercise-induced increases in the number of new neurons in the adult hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2001;21(5):1628–1634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01628.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoomissen JD, Holmes PV, Zellner AS, Poudevigne A, Dishman RK. Effects of β-Adrenoreceptor Blockade During Chronic Exercise on Contextual Fear Conditioning and mRNA for Galanin and Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118(6):1378. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.6.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH. Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(3):266–270. doi: 10.1038/6368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaynman S, Ying Z, Gomez-Pinilla F. Hippocampal BDNF mediates the efficacy of exercise on synaptic plasticity and cognition. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20(10):2580–2590. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan H, Aggleton JP, Brown MW. Different contributions of the hippocampus and perirhinal cortex to recognition memory. J Neurosci. 1999;19(3):1142–1148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-03-01142.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan H, Warburton EC, Zhu XO, Koder TJ, Park Y, Aggleton JP, Brown MW. Benzodiazepine impairment of perirhinal cortical plasticity and recognition memory. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20(8):2214–2224. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton EC, Glover CP, Massey PV, Wan H, Johnson B, Bienemann A, Brown MW. cAMP responsive element-binding protein phosphorylation is necessary for perirhinal long-term potentiation and recognition memory. J Neurosci. 2005;25(27):6296–6303. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0506-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton E, Brown MW. Findings from animals concerning when interactions between perirhinal cortex, hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex are necessary for recognition memory. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(8):2262–2272. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver IC, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, D'Alessio AC, Sharma S, Seckl JR, Meaney MJ. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(8):847–854. doi: 10.1038/nn1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters BD, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ. Object recognition memory: neurobiological mechanisms of encoding, consolidation and retrieval. Neurosci Biobehav R. 2008;32(5):1055–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XO, Brown MW, McCabe BJ, Aggleton JP. Effects of the novelty or familiarity of visual stimuli on the expression of the immediate early gene c-fos in rat brain. Neurosci. 1995;69(3):821–829. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00320-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XO, McCabe BJ, Aggleton JP, Brown MW. Mapping visual recognition memory through expression of the immediate early gene c-fos. Neuroreport. 1996;7(11):1871–1875. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199607290-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]