Abstract

Purpose

Educational outcomes for a national cohort of MD-PhD program matriculants have not been described.

Method

The authors used multivariate logistic regression to identify factors independently associated with overall MD-PhD program non-completion (both MD-only graduation and medical-school withdrawal/dismissal) compared with MD-PhD program graduation among the 1995–2000 national cohort of MD-PhD program enrollees at matriculation at medical schools with and without National Institutes of Health Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) support.

Results

Of 2,582 MD-PhD program enrollees in this national cohort (1,729[67.0%] men; 853[33.0%] women), 1,885 (73.0%) were MD-PhD-program graduates, 597 (23.1%) were MD-only graduates, and 100 (3.9%) withdrew/were dismissed from medical school. Enrollees at non-MSTP-funded schools compared with MSTP-funded schools (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.96; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.60–2.41) and who had lower Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) scores (<31 vs. ≥36: AOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.20–2.14; 31–33 vs. ≥36: AOR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.01–1.70)were more likely to have left the MD-PhD program; enrollees who reported greater planned career involvement in research (AOR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.51–0.84) and matriculated in more recent years (AOR,0.90; 95% CI, 0.85–0.96) were less likely to have left the MD-PhD program. Gender, race/ethnicity, and pre-medical debt were not independently associated with overall MD-PhD program non-completion.

Conclusions

Most MD-PhD matriculants completed the MD-PhD program, and 85.7% (597/697) of non-completers graduated from medical school. The authors’ findings regarding variables associated with MD-PhD program attrition can inform efforts to recruit and support MD-PhD program enrollees through successful completion of the dual-degree program.

Introduction

The National Institute of General Medical Sciences’ (NIGMS) Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) was introduced in 1964 to train students in both basic sciences and clinical research and to foster their development as physician scientists engaged in biomedical research.1 The number of institutions receiving MSTP funding increased from 3 in 19641 to 45 in the 2011–2012 fiscal year,2 and combined MD-PhD degree programs (including both MSTP-funded and non-MSTP funded) are currently offered at 111 of 131 medical schools in the U.S.;3 most MD-PhD programs are non-MSTP funded.

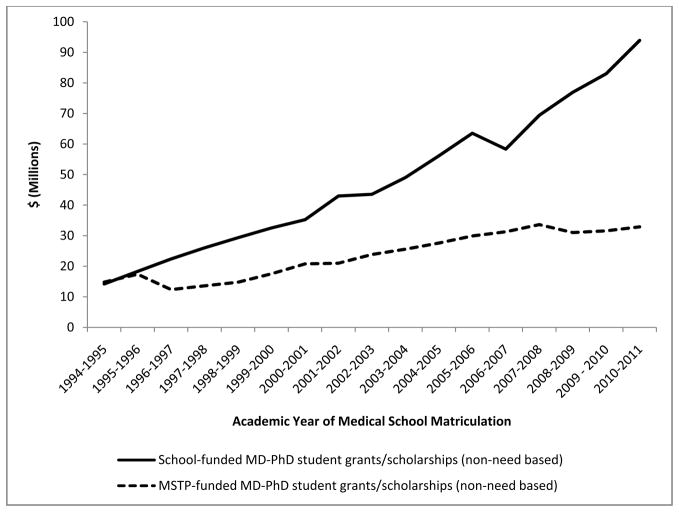

The number of MD-PhD program enrollees at U.S. medical schools continues to grow annually,4 and, both the NIGMS, through its MSTP funding, and medical schools themselves have substantially increased their level of support for MD-PhD programs over the past 15 years. Figure 1 shows the annual amounts of MSTP- and school-funded non-need-based grants/scholarships awarded without a service commitment in support of MD-PhD program enrollees in U.S. Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME)-accredited medical schools from 1994–1995 to 2010–2011. Such non-need-based MSTP and medical-school grants/scholarships for MD-PhD program enrollees were about equal in 1994–1995; by 2010–2011, non-need-based MSTP funding more than doubled to $32.9 million, and non-need-based medical-school funding increased more than six times the amount provided by schools in 1994–1995 to $93.9 million.5 Given this level of financial support, educational outcomes for MD-PhD program enrollees are of interest to medical schools throughout the U.S.1,6–8

Figure 1.

Non-need-based funding for MD-PhD program enrollees in U.S. Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME)-accredited medical schools from 1994–2011.26–28 MSTP funding was not included on the LCME Questionnaire Part I-B Student Financial Aid Questionnaire as a separate category until 1994–1995. Since school-based MD-PhD funding was not included in Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) publications prior to academic year 2005–2006, a special report with these data was prepared for this study by Susan Gaillard at the AAMC on April 29, 2010 and provided to the authors on May 11, 2010. (AAMC need-based funding data are not disaggregated on the basis of degree program of enrollment, and therefore not shown.)

In this study, we sought to describe educational outcomes of a national cohort of MD-PhD program enrollees, and examine these outcomes in the context of MSTP funding and other relevant factors. Nationally, MD completion rates among all medical-school enrollees, reportedly over 95%,9 are much higher than biomedical-field PhD completion rates among all PhD program enrollees, reportedly about 50%.10 However, educational outcomes for national cohorts of joint MD-PhD program enrollees have not been described. Thus, we sought to answer the question, “What are the rates of and factors associated with MD-PhD program non-completion?”

We hypothesized that most MD-PhD program enrollees who entered the dual-degree program at medical-school matriculation would complete the MD-PhD program and that most matriculants who did not complete the MD-PhD program would complete requirements for the MD. We also hypothesized that dual-degree completion rates for MD-PhD program matriculants would vary in association with institutional MSTP-funding status.11 We tested our hypotheses in a retrospective study of educational outcomes in a national cohort of MD-PhD program enrollees who entered the program at medical-school matriculation.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board at Washington University School of Medicine approved this study as non-human-subjects research. In 2012, we used a database that included individualized, de-identified records for all 1995–2000 matriculants enrolled in LCME-accredited U.S. medical schools with follow-up data through July 26, 2011. These de-identified records were provided to us by the AAMC and linked using a unique identification number assigned to each record by the AAMC. The researchers had no access to any student or medical-school identifiers.

To analyze variables associated with MD-PhD program non-completion versus completion, we included data for those matriculants who reported on the AAMC Matriculating Student Questionnaire (MSQ) that they enrolled in a joint MD-PhD dual-degree program at the time of medical-school matriculation. The MSQ is administered annually to incoming students and completed voluntarily on an identifiable but confidential basis.12 We included MD-PhD program matriculants from 1995–2000 to allow sufficient time for most MD-PhD program matriculants to have completed their dual-degree requirements through follow-up. We also analyzed MSQ items for age at matriculation (categorized by the AAMC as <20, 20–22, 23–25, 26–28, and >28 years; we combined the two younger age categories into <23), planned extent of career involvement in research (5-point scale: 1= not involved, 2 = involved in a limited way, 3 = somewhat involved, 4 = significantly involved, and 5 = exclusively involved), career intention at matriculation (categorized as “no choice” [for MSQ respondents who did not answer this item], “undecided,” “other,” “full-time clinical practice,” and “full-time faculty/research scientist”), and total premedical debt (categorized as “no debt,” “$100–$19,999,” “≥$20,000,” and “missing data on this MSQ item”).

We also analyzed data in the AAMC’s Student Record System (SRS), including medical-school matriculation year, gender, self-identified race/ethnicity, last status description and date, graduation date, and degree program in which student was enrolled at follow-up. The SRS is a secure, Internet-based application that contains individualized records for all students enrolled in LCME-accredited U.S. allopathic medical schools; the SRS is used to track each student from matriculation through graduation, with each medical-school’s registrars and student records representatives regularly updating and verifying the accuracy of the SRS data.13

We computed medical-school duration based on last status date or graduation date and matriculation date recorded in the SRS. Race/ethnicity was reported by matriculants in response to a list of options on the American Medical College Application Service questionnaire and categorized as Asian/Pacific Islander, underrepresented minority in medicine ([URM], including Black, Hispanic and American Indian/Alaska Native, other/unknown (including matriculants who self-identified as “other” or multiple races or who did not respond), or white. Matriculants’ last-status description was categorized as medical-school withdrawal/dismissal (including withdrawal for academic reasons, dismissal for academic reasons, withdrawal for health reasons, withdrawal for other non-academic reasons, and dismissal for non-academic reasons), graduated, or still in medical school. Most recent degree program of enrollment was categorized as either MD-PhD or MD-only; this MD-only category includes all other degree programs at enrollment (i.e., MD-only, BA-MD, BS-MD, and all other MD-advanced-degree programs, such as MD-MA, MD-MPH, MD-JD, etc., excluding the PhD).

A composite MCAT score was computed for matriculants’ most-recent-attempt verbal reasoning, physical science, and biological science subscores on the MCAT, obtained from the AAMC Data Warehouse. To include MD-PhD program matriculants who did not have MCAT scores available, we created a 5-category variable for analysis. We used the quartile split of MCAT scores for all MD-PhD graduates in our database and added a fifth category for students without MCAT scores (<31, 31–33, 34–35, ≥36, and “N/A” for students without MCAT scores).

The AAMC also provided data for institutional MSTP funding during the study period (yes vs. no). Using NIGMS rosters of MSTP-funded institutions,14 which are updated annually to list all current MSTP-funded institutions,2 the researchers categorized all U.S. LCME-accredited medical schools as having received MSTP funding for some or all years of the study period or as never having received MSTP funding during the study period. We obtained archived institutional MSTP-funding data using NIH RePORTER.15 Of the 129 U.S. LCME-accredited medical schools to which students had matriculated during the study period, 39 schools (30%) had received MSTP funding for some or all of the years between 1995 and 2000 (MSTP-funded schools), and 90 schools (70%) never had any MSTP funding during this period (non-MSTP-funded schools). The AAMC then linked this institutional MSTP-funding variable with each matriculant’s individualized record and provided the de-identified data to the researchers (without school names).

To determine the proportion of MD-PhD graduates that was included in our final study sample of MD-PhD program matriculants (based on MSQ data), we used SRS data to identify all MD-PhD program graduates in the entire cohort of 1995–2000 matriculants enrolled in LCME-accredited U.S. medical schools. We then created a 3-category variable for all these MD-PhD program graduates based on their responses to the MSQ item for degree program of enrollment at the time of medical-school matriculation (MD-PhD program matriculants, MD-only [including BA-MD, BS-MD, or MD-other-advanced-degree program matriculants], and degree program at matriculation unknown, for those MD-PhD graduates who did not complete the MSQ item for degree program of enrollment at matriculation).

Outcome Measure

Based on the SRS last status description, we created a 3-category educational outcome variable for all MD-PhD program matriculants in our study sample: MD-only graduation (for those MD-PhD program matriculants who graduated from medical school without the PhD), withdrawal/dismissal from medical school, and MD-PhD graduation. Students still enrolled in medical school were excluded from analysis.

Statistical Analysis

We used chi-square tests to identify associations among categorical variables and analysis of variance to describe differences in continuous variables between groups. We report adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) from three separate multivariate logistic regression models, which identified variables independently associated with MD-only graduation (PhD-program attrition), medical-school withdrawal/dismissal (attrition from medical school), and overall attrition (including both MD-only graduation and medical-school withdrawal/dismissal), each compared with MD-PhD graduation. All tests were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0.0.1 (© Copyright IBM Corporation, 2011). Two-sided P-values <.05 were considered significant.

Results

Of 97,096 matriculants in the 1995–2000 cohort, 89,948 (92.6%) answered the MSQ item pertaining to degree program of enrollment; of these, 2,645 (2.9%) reported joint MD-PhD program enrollment. At time of follow-up, 2,526 (95.5%) of these 2,645 MD-PhD program enrollees had graduated from medical school, and 101 (3.8%) had left medical school (withdrawal/dismissal); we excluded from our study 11 (0.4%) MD-PhD enrollees still in medical school at follow-up, and seven (0.3%) who were deceased or had their degree revoked. Of the 2,627 MD-PhD program enrollees eligible for inclusion in our analysis of educational outcomes among individuals enrolled in MD-PhD programs at medical-school matriculation, our final sample included 2,582 (98.3%) who had graduated or were no longer in medical school and had data for all variables of interest.

Descriptive statistics for these 2,582 MD-PhD program enrollees grouped by educational outcome are shown in Table 1. Of these 2,582 MD-PhD program enrollees, 1,885 (73.0%) were MD-PhD graduates, including 79.5% (1,384/1,741) at MSTP-funded and 59.6% (501/841) at non-MSTP funded medical schools. Of the remaining 697 MD-PhD program enrollees, 597 (23.1% of 2,582) were MD-only graduates, including 17.3% (302/1,741) at MSTP-funded and 35.1% (295/841) at non-MSTP-funded medical schools, and 100 (3.9%) withdrew/were dismissed from medical school, including 3.2% (55/1,741) at MSTP-funded and 5.4% (45/841) at non-MSTP-funded medical schools (chi-square, P < .001). As shown, the following variables were associated with MD-only graduation but not with withdrawal/dismissal, each compared with MD-PhD graduation: gender, race/ethnicity, matriculation year, premedical debt, MCAT score, career intention at matriculation, and planned career involvement in research at matriculation. The other two variables, age at matriculation and institutional MSTP funding, were associated with both MD-only graduation and medical-school withdrawal/dismissal, each compared with MD-PhD graduation. Mean (SD) medical-school duration in years was 8.0 (1.3) for MD-PhD graduates, 5.6 (1.8) for MD-only graduates, and 4.6 (3.0) for students who withdrew/were dismissed from medical school (P < .001). Of the 100 students who withdrew/were dismissed from medical school, 21 were dismissed for academic reasons, 12 withdrew for academic reasons, 6 were dismissed for other reasons, 4 withdrew for health reasons, and the remaining 57 withdrew for other reasons.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for 1995–2000 MD-PhD Program Enrollees in U.S. Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME)-Accredited Medical Schools, by Final Status as of July 26, 2011*

| Total N = 2,582 | MD-PhD graduation† N = 1,885 | Overall attrition† N = 697 | P- value‡ | MD-degree graduation† N = 597 | P- value‡ | Medical | P- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender† | .063 | .012 | .210 | |||||

| Male | 1,729 (67.0) | 1,282 (68.0) | 447 (64.1) | 373 (62.5) | 74 (74.0) | |||

| Female | 853 (33.0) | 603 (32.0) | 250 (35.9) | 224 (37.5) | 26 (26.0) | |||

| Race/ethnicity† | .004 | .023 | .051 | |||||

| White | 1,664 (64.4) | 1,216 (64.5) | 448 (64.3) | 387 (64.8) | 61 (61.0) | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 623 (24.1) | 473 (25.1) | 150 (21.5) | 129 (21.6) | 21 (21.0) | |||

| URM | 259 (10.0) | 167 (8.9) | 92 (13.2) | 75 (12.6) | 17 (17.0) | |||

| Other/unknown | 36 (1.4) | 29 (1.5) | 7 (1.0) | 6 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | |||

| Age at matriculation,§ years | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| < 23 | 1,519 (58.8) | 1,177 (62.4) | 342 (49.1) | 289 (48.4) | 53 (53.0) | |||

| 23–25 | 816 (31.6) | 580 (30.8) | 236 (33.9) | 206 (34.5) | 30 (30.0) | |||

| 26–28 | 174 (6.7) | 99 (5.3) | 75 (10.8) | 66 (11.1) | 9 (9.0) | |||

| >28 | 73 (2.8) | 29 (1.5) | 44 (6.3) | 36 (6.0) | 8 (8.0) | |||

| Matriculation year† | .004 | .001 | .973 | |||||

| 1995 | 421 (16.3) | 278 (14.7) | 143 (20.5) | 129 (21.6) | 14 (14.0) | |||

| 1996 | 433 (16.8) | 313 (16.6) | 120 (17.2) | 102 (17.1) | 18 (18.0) | |||

| 1997 | 410 (15.9) | 294 (15.6) | 116 (16.6) | 99 (16.6) | 17 (17.0) | |||

| 1998 | 476 (18.4) | 357 (18.9) | 119 (17.1) | 103 (17.3) | 16 (16.0) | |||

| 1999 | 437 (16.9) | 329 (17.5) | 108 (15.5) | 89 (14.9) | 19 (19.0) | |||

| 2000 | 405 (15.7) | 314 (16.7) | 91 (13.1) | 75 (12.6) | 16 (16.0) | |||

| Premedical debt§ | .034 | .033 | .333 | |||||

| No debt | 1,567 (60.7) | 1,148 (60.9) | 419 (60.1) | 360 (60.3) | 59 (59.0) | |||

| $100–$19,999 | 697 (27.0) | 522 (27.7) | 175 (25.1) | 146 (24.5) | 29 (29.0) | |||

| ≥ $20,000 | 265 (10.3) | 184 (9.8) | 81 (11.6) | 73 (12.2) | 8 (8.0) | |||

| Missing data on this item | 53 (2.1) | 31 (1.6) | 22 (3.2) | 18 (3.0) | 4 (4.0) | |||

| MCAT score¶ | <.001 | <.001 | .305 | |||||

| ≥ 36 | 759 (29.4) | 615 (32.6) | 144 (20.7) | 116 (19.4) | 28 (28.0) | |||

| 34–35 | 503 (19.5) | 393 (20.8) | 110 (15.8) | 93 (15.6) | 17 (17.0) | |||

| 31–33 | 718 (27.8) | 510 (27.1) | 208 (29.8) | 181 (30.3) | 27 (27.0) | |||

| < 31 | 578 (22.4) | 351 (18.6) | 227 (32.6) | 200 (33.5) | 27 (27.0) | |||

| Not available | 24 (0.9) | 16 (0.8) | 8 (1.1) | 7 (1.2) | 1 (1.0) | |||

| Institutional MSTP funding | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| MSTP funded | 1,741 (67.4) | 1,384 (73.4) | 357 (51.2) | 302 (50.6) | 55 (55.0) | |||

| Non-MSTP funded | 841 (32.6) | 501 (26.6) | 340 (48.8) | 295 (49.4) | 45 (45.0) | |||

| Career intention at matriculation§ | .001 | <.001 | .261 | |||||

| Full-time faculty/non- university research scientist | 2,142 (83.0) | 1,596 (84.7) | 546 (78.3) | 464 (77.7) | 82 (82.0) | |||

| No choice made | 50 (1.9) | 33 (1.8) | 17 (2.4) | 13 (2.2) | 4 (4.0) | |||

| Undecided | 196 (7.6) | 137 (7.3) | 59 (8.5) | 54 (9.0) | 5 (5.0) | |||

| Other | 96 (3.7) | 63 (3.3) | 33 (4.7) | 27 (4.5) | 6 (6.0) | |||

| Full-time clinical practice | 98 (3.8) | 56 (3.0) | 42 (6.0) | 39 (6.5) | 3 (3.0) | |||

| P- value†† | P- value†† | P- value†† | ||||||

| Planned career involvement in research at matriculation,§ Mean (SD) | 4.0 (0.4) | 4.1 (0.4) | 4.0 (0.5) | <.001 | 4.0 (0.4) | <.001 | 4.0 (0.5) | .053 |

URM, indicates underrepresented minority in medicine; MCAT, Medical College Admission Test; MSTP, Medical Scientist Training Program.

Source: American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) Student Record System.

Chi-square tests of significance comparing each attrition outcome with MD-PhD program graduation.

Source: AAMC Matriculating Student Questionnaire.

Source: AAMC Data Warehouse. Score is for the most recent attempt.

Source: National Institute of General Medical Sciences2,14 and National Institutes of Health RePORTER.15

Tests of significance are analysis of variance comparing each attrition outcome with MD-PhD program graduation.

Table 2 shows results of three multivariable logistic regression models used to identify variables associated with MD-only graduation, medical-school withdrawal/dismissal, and overall attrition (including both MD-only graduation and medical-school withdrawal/dismissal), each compared with MD-PhD graduation. Among all 2,582 MD-PhD program enrollees in the sample, those who had enrolled at non-MSTP-funded medical schools, had MCAT scores <34 and were ≥23 years of age at matriculation were more likely, whereas enrollees who matriculated in more recent years and reported greater planned career involvement in research at matriculation were less likely, to be in the overall attrition group. Among all 2,482 medical-school graduates, those who had enrolled at non-MSTP-funded medical schools, had MCAT scores < 34, were ≥23 years old at matriculation, and intended full-time clinical practice careers at matriculation were more likely, whereas enrollees who matriculated in more recent years and reported greater planned career involvement in research at matriculation were less likely, to be MD-only graduates. Among those MD-PhD program enrollees who either graduated with MD-PhD degrees or withdrew/were dismissed from medical school, those who matriculated at non-MSTP-funded medical schools, were URM race/ethnicity, and >28 years of age at matriculation were more likely to have withdrawn/been dismissed from medical school. Gender and premedical debt were not independently associated with overall attrition, with MD-only graduation, or with medical-school withdrawal/dismissal.

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression models to identify factors independently associated with attrition from MD-PhD programs*

| AOR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall attrition (MD graduation and withdrawal/dismissal) N = 2,582 | MD graduation N = 2,482 | Withdrawal/dismissal from medical school N = 1,985 | |

| Gender | |||

| Men | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Women | 1.10 (0.90 – 1.33) | 1.17 (0.95 – 1.43) | 0.70 (0.44 – 1.12) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.99 (0.79 – 1.24) | 0.99 (0.78 – 1.26) | 1.01 (0.60 – 1.70) |

| Other/unknown | 0.84 (0.35 – 1.98) | 0.86 (0.34 – 2.19) | 0.78 (0.10 – 5.97) |

| URM | 1.32 (0.97 – 1.79) | 1.22 (0.88 – 1.69) | 2.19 (1.17 – 4.08) |

| Institutional MSTP funding | |||

| MSTP funded | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Non-MSTP funded | 1.96 (1.60 – 2.41) | 1.95 (1.57 – 2.42) | 2.04 (1.28 – 3.26) |

| Planned career involvement in research at matriculation† | 0.65 (0.51 – 0.84) | 0.63 (0.48 – 0.82) | 0.70 (0.42 – 1.18) |

| Premedical debt | |||

| No debt | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| $100–$19,999 | 0.84 (0.68 – 1.04) | 0.81 (0.64 – 1.02) | 1.01 (0.63 – 1.61) |

| ≥ $20,000 | 1.10 (0.81 – 1.49) | 1.16 (0.84 – 1.60) | 0.75 (0.34 – 1.64) |

| Missing data on this MSQ item | 1.72 (0.95 – 3.13) | 1.75 (0.93 – 3.28) | 2.19 (0.69 – 6.95) |

| MCAT score | |||

| ≥ 36 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 34–35 | 1.09 (0.82 – 1.45) | 1.13 (0.83 – 1.54) | 0.86 (0.46 – 1.61) |

| 31–33 | 1.31 (1.01 – 1.70) | 1.40 (1.06 – 1.85) | 0.89 (0.50 – 1.59) |

| < 31 | 1.60 (1.20 – 2.14) | 1.76 (1.29 – 2.40) | 0.94 (0.49 – 1.79) |

| N/A | 0.93 (0.37 – 2.36) | 1.04 (0.40 – 2.73) | 0.49 (0.06 – 4.24) |

| Age at matriculation, years‡ | |||

| < 23 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 23–25 | 1.24 (1.01 – 1.52) | 1.28 (1.03 – 1.59) | 1.06 (0.66 – 1.71) |

| 26–28 | 2.18 (1.55 – 3.06) | 2.26 (1.58 – 3.23) | 1.63 (0.75 – 3.52) |

| > 28 | 3.53 (2.12 – 5.88) | 3.52 (2.07 – 6.00) | 4.35 (1.78 – 10.64) |

| Matriculation year§ | 0.90 (0.85 – 0.96) | 0.88 (0.83 – 0.94) | 1.02 (0.90 – 1.16) |

| Career intention at matriculation | |||

| Full-time faculty/non-university research scientist | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| No choice made | 1.36 (0.72 – 2.56) | 1.22 (0.61 – 2.45) | 2.21 (0.74 – 6.63) |

| Undecided | 1.28 (0.91 – 1.81) | 1.42 (0.99 – 2.03) | 0.66 (0.26 – 1.69) |

| Other | 1.44 (0.91 – 2.27) | 1.39 (0.85 – 2.27) | 1.62 (0.67 – 3.96) |

| Full-time clinical practice | 1.47 (0.94 – 2.29) | 1.60 (1.02 – 2.52) | 0.78 (0.23 – 2.66) |

Each outcome was compared with MD-PhD program graduation (reference). AOR indicates adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; URM, underrepresented minorities; MSTP, Medical Scientist Training Program; MSQ, Matriculating Student Questionnaire; MCAT, Medical College Admission Test; N/A, MCAT scores not available. AORs (95% CI) in bold are statistically significant. Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test P > .05 for each model.

AOR < 1.00 indicates lower likelihood of attrition with each increasing unit of planned career involvement in research.

AOR > 1.00 indicates greater likelihood of attrition with each increasing unit of age group at matriculation.

AOR < 1.00 indicates lower likelihood of attrition with each increasing year of matriculation.

In order to determine the proportion of MD-PhD program graduates among the 1995–2000 matriculants included in our final sample, we also examined program enrollment at time of matriculation for all MD-PhD program graduates in our entire 1995–2000 national cohort of 97,096 matriculants. There were 2,629 (2.7%) MD-PhD graduates in this national cohort. Based on responses to the MSQ item about degree program of enrollment at medical-school matriculation, 1,920 (73.0%) of these MD-PhD graduates had enrolled in MD-PhD programs at medical-school matriculation (of whom 1,885 [98.2%] were included in our final sample), and 399 (15.2%) had enrolled in MD-degree or MD-other-advanced-degree programs at medical-school matriculation. The remaining 310 (11.8%) MD-PhD graduates did not respond to the MSQ item about degree program of enrollment at medical-school matriculation. Thus, of the 2,319 MD-PhD graduates in our database for whom degree program at matriculation was available from MSQ data, 82.8% (1,920/2,319) had entered the MD-PhD program at the time of medical-school matriculation.

Discussion

Most MD-PhD program enrollees in our sample were MD-PhD program graduates, and the majority of enrollees who discontinued their MD-PhD program participation graduated from medical school. The overall MD-degree program completion rate of 96% (including MD-PhD graduates and MD-only graduates) that we observed among all MD-PhD program enrollees is aligned with the 10-year medical-school completion rate of 96% reported for all U.S. LCME-accredited medical-school enrollees.9 The PhD-degree program completion rate of over 70% that we observed among MD-PhD program enrollees in our sample compares favorably with recently reported PhD-degree completion rates among doctoral degree program enrollees in biomedical science fields, which ranged from 41.6% (genetics and genomics) to 56.2% (immunology and infectious diseases).10

The mean medical-school duration for MD-only graduates in our cohort was 5.6 years, suggesting that MD-only graduates likely completed, on average, two years of preclinical study and one or more years of pre-doctoral research training prior to PhD-program discontinuation and completion of the MD-degree program requirements. This line of reasoning is consistent with results of the earlier NIGMS study indicating that MSTP-funded medical-school graduates who completed only MD-degree program requirements had received a mean of 36 months of pre-doctoral training support.1 Similarly, a single-institutional analysis of MD-PhD program attrition reported that more than half of all MD-PhD program enrollees who ultimately discontinued program participation had remained in the MD-PhD program for at least 3 years prior to discontinuation.16 Thus, our results and these observations of others suggest that more than three years of follow-up after MD-PhD program enrollment is needed to estimate the extent of attrition among MD-PhD program enrollees. Indeed, with a minimum 10-year follow-up in our national cohort study, there were 11 MD-PhD program enrollees who were excluded from our final study sample because they were still in medical school.

Our findings regarding MD-PhD program attrition should be considered in the context of two previous multi-institutional studies of MD-PhD program enrollees’ career paths, each of which included MD-PhD program attrition data.1,8 First, an NIGMS study examined outcomes for all MD-PhD program enrollees nationally who had received at least 12 months of MSTP support during the 1969–1990 study period and had graduated from medical school by 1990.1 Of 1,430 MSTP trainees included in that study, 1,161 (81.2%) were MD-PhD graduates, and 269 (18.8%) were MD-only graduates, indicating 18.8% attrition from the PhD-degree component of the program among these MSTP-supported medical-school graduates.1 The rate of attrition from the PhD-degree component of MD-PhD programs at MSTP-funded schools in our sample of 1995–2000 MD-PhD program matriculants (17.3%) was closely aligned to that observed in this earlier NIGMS study. Thus, despite the increase in mean duration of training required for MD-PhD program completion (from 6.6 years in the 1980 cohort, 7.3 years in the 1990 cohort of MSTP graduates in the NIGMS study,1 to about eight years in more recent cohorts of MD-PhD graduates from MSTP-funded institutions17), PhD-program attrition among MD-PhD program enrollees at MSTP-funded medical schools was relatively constant over these two study periods.

The second multi-institutional study of MD-PhD program enrollees that included attrition data was published in 2010 by Brass and colleagues.8 In this survey study of 24 MD-PhD program directors, an average of 10% of MD-PhD program enrollees who had entered MD-PhD programs from academic year (AY)1998 through AY2007, and were followed through AY2008, had withdrawn from their MD-PhD programs; attrition varied from 3% to 34% across programs.8 This average overall attrition rate of 10% was substantially lower than either the 27.5% overall attrition that we observed among all enrollees in our study sample or the 20.5% overall attrition that we observed only among enrollees at MSTP-funded medical schools. Differences in study design and sample selection can explain the disparities in attrition rates observed by us and by Brass et al.8 Our study included a national sample of MD-PhD program enrollees at matriculation who were followed for a minimum of 10 years after program enrollment, and our sample was comprised only of MD-PhD program enrollees at matriculation who were no longer in medical school at follow-up. By comparison, Brass et al.8 included MD-PhD program enrollees (who may or may not have entered MD-PhD programs at the time of medical-school matriculation) at 24 selected institutions (20 MSTP-funded and 4-non-MSTP-funded), who were followed for 1–10 years after program enrollment, and included many students who were still enrolled in their MD-PhD programs. Thus, substantial differences in study design and sample selection explain the disparate MD-PhD program attrition rates reported in our sample and the sample reported by Brass et al.8

Our observations also have implications for selection and support of MD-PhD program enrollees. Based on MCAT scores, MD-PhD program enrollees are a very well-prepared group academically. Our finding that MD-PhD program enrollees with MCAT scores below 34 were more likely to be MD-only graduates provides support for MD-PhD program directors’ use of MCAT scores as among the criteria for selecting applicants who will most likely complete the MD-PhD program. MD-PhD programs currently accept and enroll students with a wide range of MCAT scores; in 2011, MD-PhD program matriculants’ MCAT scores ranged from 22 to 44.18 Thus, MD-PhD program directors may consider using MCAT scores, in particular, to identify MD-PhD program enrollees at risk of attrition from the PhD-program component; some of these students might benefit from additional academic support.

The relationships we observed between MD-only graduation (PhD-degree attrition) and each of students’ planned career involvement in research at matriculation and career intention at matriculation provide support for MD-PhD program directors’ selection of applicants with career aspirations that are well-aligned with programmatic missions and goals.16 Because, compared with matriculants <23 years old, we observed that older matriculants were at greater risk of MD-only graduation and that matriculants >28 years old, specifically, were at greater risk of withdrawal/dismissal from medical school, further research is warranted to examine whether older MD-PhD program enrollees face particular challenges in completing the MD-PhD program that are amenable to intervention.

That more recent matriculation year was associated with a lower likelihood of PhD-program attrition suggests that, during the time-frame of our study, MD-PhD program directors may have become better able to recruit and support program enrollees who will successfully complete MD-PhD program requirements. This observation seems particularly important in light of the increase in MD-PhD program enrollment nationally by nearly 40% over the past ten years (from 3,632 in 200219 to 5,097 in 2012.20 The likelihood of attrition also differed significantly by medical-school MSTP-funding status even after controlling for other variables in the models. Attending an MSTP-funded school was associated with a lower likelihood of both types of attrition. These observations suggest that directors and administrators at MSTP-funded programs, in particular, might have expertise in selecting applicants most likely to complete the MD-PhD programs. MSTP-funded programs also may have particular resources and programs in place (e.g., academic support, mentoring and advising programs) to support their students through successful MD-PhD program completion. Differences in financial support also might have contributed to the differences in attrition we observed among enrollees at schools with and without MSTP funding. A summary of MD-PhD program policies released by the AAMC indicated that MD-PhD program positions were uniformly fully funded at 41 (93.2% of 44) MSTP-funded medical schools but only at 29 (72.5% of 40) non-MSTP-funded medical schools.11

Although an earlier single-institution survey study reported that high levels of debt (>$50,000) were associated with greater consideration of leaving the MD-PhD program at their school,21 higher premedical debt in our cohort (>$20,000) was not independently associated with MD-PhD program attrition. Also, we were unable to examine total accumulated debt during medical school in this national cohort, because these data were available only for medical-school graduates who completed the AAMC’s Graduation Questionnaire;22 not all matriculants included in our study completed (or were eligible to complete) this questionnaire. Whether attrition rates would decrease with a reduction of total accumulated debt after matriculation is an empirical question requiring further study; but it would be a plausible hypothesis based on findings from this earlier study.21

Finally, our results have implications for physician-scientist workforce diversity. Over 30% of MD-PhD program enrollees in our sample were women, and we did not observe any independent associations between attrition and gender. This finding extends earlier observations that women were no more likely than men to consider leaving the MD-PhD program21 and that program attrition rates were not associated with the percentage of female trainees enrolled in the program.8 Thus, as the numbers of women enrolled in MD-PhD programs increase,4 the number of women MD-PhD program graduates can be expected to similarly increase. However, URM race/ethnicity was independently associated with a greater likelihood of attrition due to withdrawal/dismissal from medical school, suggesting that efforts to promote racial/ethnic diversity of the physician-scientist workforce through enrollment of greater numbers of URM students in MD-PhD programs may not be fully realized, because URM MD-PhD program enrollees in our study sample were disproportionately more likely to leave medical school altogether (Table 2). Efforts to identify additional factors contributing to medical-school attrition among URM MD-PhD program enrollees are warranted so that appropriate interventions can be designed to minimize this attrition.

Among the strengths of our study was inclusion of a national sample of MD-PhD program enrollees followed for a minimum of 10 years from the time of program entry at medical-school matriculation. Unlike previously published studies that included educational outcomes data for MD-PhD program enrollees,1,8 our study described the extent of each of PhD-degree program attrition and medical-school attrition for a national cohort of MD-PhD program enrollees at the time of matriculation. We also included data for many variables of interest that have not previously been examined as predictors of MD-PhD program attrition (e.g., students’ MCAT scores, extent of their planned career involvement in research, and medical-schools’ receipt of MSTP funding).

Our study also has some limitations. Our sample was limited to students who completed the MSQ and indicated their enrollment in MD-PhD programs at the time of medical-school matriculation. As with all self-reported survey data, the accuracy of MSQ data are dependent on the accuracy with which the respondents completed the questionnaire. Our outcome of interest was based on SRS data for last status and for degree program at graduation; thus, the accuracy of our educational outcomes data are subject to the accuracy with which the registrars and student records representatives updated their students’ records. Our findings thus represent only the best inferences that can be made about educational outcomes for MD-PhD program enrollees from these available data and must be interpreted with these limitations in mind. MD-PhD program enrollees who entered MD-PhD programs after medical-school matriculation and MD-PhD program enrollees who chose not to respond to the MSQ item for degree program of enrollment were excluded from our analysis. We might reasonably expect that MD-PhD program attrition would be lower for students who are motivated to enroll in MD-PhD programs after medical-school matriculation, when they have already successfully completed some portion of the medical-school curriculum, compared with students who enroll in MD-PhD programs at the time of medical-school matriculation prior to successfully completing any portion of the medical-school curriculum. If we assume, as a “best case” scenario, that there was 0% attrition among all MD-PhD program enrollees who entered MD-PhD programs after medical-school matriculation and 0% attrition among all MD-PhD program enrollees who did not respond to the MSQ item for degree program of enrollment (who may or may not have been MD-PhD program enrollees at matriculation), then overall attrition among all MD-PhD program enrollees in our national cohort of 1995–2000 medical-school matriculants would be 20.5%, calculated as follows: 679 MD-PhD program non-completers/3,308 MD-PhD program enrollees (2629 MD-PhD program graduates + 679 MD-PhD program non-completers).

Given that the overall attrition rate was between 20.5% and 27.0% among MD-PhD program enrollees who had entered the program at medical-school matriculation from 1995–2000, it appears to be sound policy for MD-PhD program directors to accept applicants from internal MD students for their MD-PhD programs. Indeed, of 84 MD-PhD program directors who responded to a 2012 survey conducted by the MD-PhD Section Communications Committee of the AAMC Graduate Research Education and Training (GREAT) Group, 80 programs (95%) accept applicants from internal MD students; in addition, 46 programs (54.8%) accept applicants from internal PhD students, and 32 programs (38.1%) accept transfer students from other MD-PhD programs.11

We also note that program-specific attrition may vary from our observations of this national cohort, and this may be so among both MSTP-funded and non-MSTP-funded programs. Among MSTP-funded programs, the duration of MSTP funding ranged considerably, from schools that were initially funded during the 1995–2000 study period to schools that had been continuously funded since MSTP inception in 1964.1,15 In addition to MSTP-funding status, individual MD-PhD programs (both MSTP- and non-MSTP funded) vary by size,8,23 demographic composition,8 curricular requirements,11 and the extent and nature of advising systems for MD-PhD enrollees.24 Program-specific attrition might be associated with many of these program characteristics, but we lacked such program-level data. We also note that MD-PhD enrollees may pursue their PhD studies in a variety of fields;8,23 but we did not have information about enrollees’ PhD-degree fields of study. Moreover, our results might not be generalizable to enrollees in Committee on Accreditation of Canadian Medical Schools/Canadian LCME-accredited medical schools or in osteopathic medical schools. Nonetheless, our findings can inform efforts by MD-PhD programs to recruit and enroll a diverse pool of MD-PhD program applicants whose educational and professional goals are well aligned with MD-PhD programmatic goals.

In conclusion, while some level of MD-PhD program non-completion is likely inevitable, most MD-PhD program enrollees complete the dual-degree program; our results may be of particular interest to MD-PhD program directors and faculty seeking to maximize program completion rates. MSTP funding, in particular, plays an important beneficial role in promoting MD-PhD program completion. Given the steadily increasing divergence in costs borne by medical schools and by MSTP funding for MD-PhD programs, and with relatively stagnant MSTP-funding levels from 2007–2011 (Figure 1), the impact that the current federal fiscal crisis25 will have on MSTP-funding levels and on the medical schools and students who benefit from this funding remains to be seen.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues, Paul Jolly, PhD, Gwen Garrison, PhD, David Matthew, PhD, Franc J. Slapar, MA, Susan Gaillard, BS, and Hershel Alexander, PhD, at the Association of American Medical Colleges, Washington, D.C., for their support of our research efforts through provision of data and assistance with coding. We also thank James Struthers, BA, and Yan Yan, MD, PhD at Washington University School of Medicine, for data management services and statistical consults, respectively.

Funding/Support: This study was funded in part by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS; 2R01 GM085350-04 and R01 GM094535-02) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Center Support grant to the Siteman Cancer Center (P30 CA091842-07) for use of the Health Behavior, Communication, and Outreach Core data management services. The NIGMS and NCI were not involved in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Washington University School of Medicine.

Disclaimer: The conclusions of the authors are not necessarily those of the Association of American Medical Colleges, National Institutes of Health or their respective staff members.

Previous Presentations: Preliminary results of this study were presented in part at the AAMC Graduate Research, Education, and Training (GREAT) Group, MD-PhD section, 2011 Annual Meeting, Minneapolis, MN, July 28–30, 2011; at the 5th Annual Conference on Understanding Interventions That Broaden Participation in Research Careers, Baltimore, MD, May 10–12, 2012; and at the 51st Annual Conference on Research in Medical Education, 123rd Annual Meeting of the Association of American Medical Colleges, San Francisco, CA, November 2–7, 2012.

Contributor Information

Donna B. Jeffe, Email: djeffe@dom.wustl.edu, Research professor of medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, and director, Health Behavior, Communication, and Outreach Core, Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri.

Dorothy A. Andriole, Email: andrioled@wusm.wustl.edu, Assistant dean for medical education and associate professor of surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri.

Heather D. Wathington, Email: hw4w@virginia.edu, Assistant professor, Curry School of Education, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia.

Robert H. Tai, Email: rhtai@virginia.edu, Associate professor, Curry School of Education, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia.

References

- 1.National Institute of General Medical Sciences. [Accessed March 6, 2013];MSTP study: the careers and professional activities of graduates of the NIGMS medical scientist training program. 1998 Sep; http://publications.nigms.nih.gov/reports/mstpstudy/

- 2.National Institute of General Medical Sciences. [Accessed March 6, 2013];Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) institutions. http://www.nigms.nih.gov/Training/InstPredoc/PredocInst-MSTP.htm.

- 3.Barzansky B, Etzel SI. Medical schools in the United States, 2010–2011. JAMA. 2011;306(9):1007–1014. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association of American Medical Colleges. [Accessed March 6, 2013];Table 32. MD-PhD applicants, acceptees, matriculants and graduates of U.S. medical schools by sex, 1999–2010. https://www.aamc.org/download/161868/data/table32-mdphd00-11.pdf.

- 5.Association of American Medical Colleges. AAMC data book: medical schools and teaching hospitals by the numbers. Washington DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang D, Meyer RE. Effect of two Howard Hughes Medical Institute research training programs for medical students on the likelihood of pursuing research careers. Acad Med. 2003;78(12):1271–1280. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200312000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andriole DA, Whelan AJ, Jeffe DB. Characteristics and career intentions of the emerging MD/PhD workforce. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1165–1173. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brass LF, Akabas MH, Burnley LD, Engman DM, Wiley CA, Andersen OS. Are MD-PhD programs meeting their goals? An analysis of career choices made by graduates of 24 MD-PhD programs. Acad Med. 2010;85:692–701. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d3ca17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garrison G, Mikesell C, Matthew D. Medical School Graduation and Attrition Rates. [Accessed March 7, 2013];AAMC Analysis in Brief. 2007 Apr;7(2) https://www.aamc.org/download/102346/data/aibvol7no2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Research Council. Research-doctorate programs in the biomedical sciences: selected findings from the NRC assessment. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; [Accessed March 6, 2013]. http://grants.nih.gov/training/biomedical_sciences.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Association of American Medical Colleges. [Accessed March 6, 2013];Summary of MD-PhD programs and policies. Updated October 10, 2012. https://www.aamc.org/students/download/62760/data/faqtable.pdf.

- 12.Association of American Medical Colleges. Matriculating Student Questionnaire (MSQ) [Accessed March 6, 2013];Sample matriculating student questionnaire. https://www.aamc.org/data/msq/

- 13.Association of American Medical Colleges. [Accessed March 6, 2013];Student Records System (SRS) https://www.aamc.org/services/srs/

- 14.National Institute of General Medical Sciences. [Accessed March 6, 2013];Medical Scientist Training Program. http://www.nigms.nih.gov/Training/InstPredoc/PredocOverview-MSTP.htm.

- 15.NIH RePORTER. [Accessed March 6, 2013];Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORT) http://www.projectreporter.nih.gov/

- 16.Milewicz DM. Training the physician scientist: alternative pathways. Association of American Medical Colleges GREAT MD-PhD section annual meeting; 2008. [Accessed March 6, 2013]. https://www.aamc.org/linkableblob/62074-3/data/milewicz08-data.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeffe DB, Andriole DA. A national cohort study of MD-PhD graduates of medical schools with and without funding from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences’ Medical Scientist Training Program. Acad Med. 2011;86(8):953–61. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822225c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Association of American Medical Colleges. [Accessed March 6, 2013];Table 35. MCAT scores and GPAs for MD/PhD applicants and matriculants to U.S. medical schools, 2008–2011. https://www.aamc.org/download/161878/data/table45-mdphd-mcatgpa-2011.pdf.

- 19.Association of American Medical Colleges. [Accessed March 6, 2013];Table 36. Total active MD/PhD enrollment by U.S. medical school and sex, 2002 – 2006. https://www.aamc.org/download/161882/data/table36a-mdphd-enroll-sch-sex-0206.pdf.

- 20.Association of American Medical Colleges. [Accessed March 6, 2013];Table 36. Total active MD/PhD enrollment by U.S. medical school and sex, 2008 – 2012. https://www.aamc.org/download/321554/data/2012factstable36-2.pdf.

- 21.Watt CD, Greeley SA, Shea JA, Ahn J. Educational views and attitudes, and career goals of MD-PhD students at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2005;80:193–198. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200502000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Association of the American Medical Colleges. Graduation questionnaire. [Accessed March 6, 2013];Previous questionnaires. https://www.aamc.org/data/gq/questionnaires/

- 23.Ahn J, Watt CD, Man L, Greeley SAW, Shea JA. Educating future leaders of medical research: analysis of student opinions and goals from the MD-PhD SAGE (Students’ Attitudes, Goals, and Education) survey. Acad Med. 2007;82(7):633–645. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318065b907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S, Wiley C. Advising and tracking of trainees and graduates: results of the June 2008 survey of MD-PhD program directors and administrators. Association of American Medical Colleges GREAT MD-PhD section annual meeting; 2008. [Accessed March 6, 2013]. https://www.aamc.org/linkableblob/62062-3/data/sandraee08-data.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) [Accessed March 6, 2013];OMB Report Pursuant to the Sequestration Transparency Act of 2012 (P. L. 112–155) http://news.sciencemag.org/scienceinsider/Combined_STAReport_Watermark.pdf.

- 26.Association of American Medical Colleges. AAMC data book statistical information related to medical education. Washington DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Association of American Medical Colleges. AAMC data book statistical information related to medical schools and teaching hospitals (annual editions) Washington DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 1999–2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Association of American Medical Colleges. AAMC data book: medical schools and teaching hospitals by the numbers (annual editions) Washington DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2001–2012. [Google Scholar]