Abstract

The possibility has been raised in recent years that infection might contribute as an inflammatory stimulus to chronic “noninfectious” degenerative diseases. Within the past decade, serious attention has been given to the possibility of bacterial vectors as causal factors of atherosclerosis. To date, the greatest amount of information has related to the intracellular organism Chlamydia pneumoniae. This interest has been stimulated by the frequent finding of bacterial antigens and, occasionally, recoverable organisms, within human atherosclerotic plaque. Indirect evidence for and against the benefit of anti-Chlamydia antibiotic agents comes from epidemiologic studies.

Given the potential for confounding in observational studies, prospective, randomized intervention trials are required. These antibiotic trials have generated enthusiastic expectations for proving (or disproving) the infectious-disease hypothesis of atherosclerosis and establishing new therapies. However, these expectations have been tempered by important limitations and uncertainties. Negative outcomes can be explained not only by an incorrect hypothesis but also by inadequate study size or design or by an ineffective antibiotic regimen. In contrast, if studies are positive, the hypothesis still is not entirely proved, because a nonspecific anti-inflammatory effect or an anti-infective action against other organisms might be operative.

The clinical trial data to date have not provided adequate support for the clinical use of antibiotics in primary or secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. New and innovative experimental approaches, in addition to traditionally designed antibiotic trials, should be welcome in our attempts to gain adequate insight into the role of infection in atherosclerosis and its therapy.

Key words: Antibiotic prophylaxis; antibiotics, macrolide; antibiotics/therapeutic use; arteriosclerosis/etiology/pathology/prevention & control; azithromycin/therapeutic use; inflammation; Chlamydia infections; Chlamydia pneumoniae; chronic disease; myocardial infarction/epidemiology; coronary disease/mortality; risk factors

The paradigm of atherosclerosis has shifted from the perception that it is a passive, infiltrative process, to the realization that it is active, inflammatory, and thrombotic. 1 It is well known that a number of noninfectious factors, many related to standard risk factors, such as oxidized low-density lipoproteins (LDL) and advanced glycation products, lead to circulatory oxidative stress and stimulate vascular inflammation.

Potential Role of Infections in Atherosclerosis and Rationale for Antibiotics

The possibility has been raised in recent years that infection, too, might contribute as an inflammatory stimulus to chronic “noninfectious” degenerative diseases such as atherosclerosis. 2 This is well exemplified by the discovery in recent years that Helicobacter pylori is an etiologic factor for human peptic ulcer disease. Speculation on an association between infectious agents and atherosclerosis dates to the mid 19th century. A “proof of principle” of viral pathogenesis occurred by the mid 20th century with the discovery that Marek disease virus in chickens was associated with marked and accelerated atherosclerosis. Additional viral vectors garnering attention include herpes simplex 1 and 2, Epstein-Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus, and influenza A.

Within the past decade, serious attention also has been given to the possibility of bacterial vectors as causal factors of atherosclerosis. To date, the greatest amount of information has related to the relatively recently discovered intracellular organism Chlamydia pneumoniae. 2 This interest has been stimulated by the frequent finding of bacterial antigens and, occasionally, recoverable organisms, within human atherosclerotic plaque, and by seroepidemiologic studies. Moreover, animal studies have demonstrated the ability of active infection with C. pneumoniae to stimulate or accelerate, and antibiotics to prevent, atherosclerosis. Given the pressing need for insights into the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, a disease of epidemic proportions in the western world, and into its prevention and treatment, it is not surprising that antibiotic trials, to date aimed primarily at C. pneumoniae, have been undertaken.

Antibiotics Targeting Chlamydia pneumoniae. Chlamydia are sensitive to macrolides, tetracyclines, and fluoroquinolones, 3 and these antibiotics have been considered for trials directed against C. pneumoniae as a causal factor for coronary and extracoronary atherosclerosis.

Azithromycin is the most extensively studied and tested antibiotic to date for application to coronary heart disease (CHD). Azithromycin is readily taken up into atherosclerotic plaque. 4 We and others have found it to be effective in animal models. 5,6 Animal studies have been followed by several antibiotic trials in human beings.

Azithromycin is indicated and effective for acute upper respiratory and skin infections caused by C. pneumoniae. It also is approved for sexually transmitted Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Azithromycin is rapidly absorbed when taken orally. It then distributes widely into tissues where its tissue half-life is prolonged (about 72 hours). A single dose may require 10 days for elimination: a property that has allowed azithromycin to be given once weekly in clinical trials after an initial loading regimen. Azithromycin also has been generally well tolerated during long-term prophylaxis. 7 Its most common adverse effects are gastrointestinal symptoms and superinfection (for example, candidiasis). 7,8

Another macrolide, roxithromycin, also has been tested in clinical trials. Finally, the quinolones (for example, gatifloxacin), 9 which have the advantage of greater cytotoxic potential, currently are undergoing experimental and clinical assessment.

Epidemiologic Evidence for and against the Usefulness of Antibiotic Agents in Coronary Heart Disease. Indirect evidence for and against the benefit of anti-Chlamydia antibiotic agents comes from epidemiologic studies. One population-based study compared 3,315 patients who had experienced a 1st acute myocardial infarction (MI) with over 12,000 patients in a control group. 10 Patients with an MI were less likely than their counterparts in the control group to have used a tetracycline antibiotic (adjusted odds ratio, 0.7) or a quinolone (odds ratio, 0.45). In contrast, previous use of macrolides, sulfonamides, penicillins, or cephalosporins had no effect on MI risk.

In contrast, another population-based study found no reduction in risk for a 1st MI with the use of erythromycin, tetracycline, or doxycycline during the previous 5 years, and its authors argued against their usefulness in preventing primary coronary heart disease (CHD). 11

Given the potential for confounding in observational studies, prospective, randomized intervention trials are required.

Results of Randomized Antibiotic Trials for Chronic Coronary Heart Disease

Early Studies. In an initial pilot clinical trial, 60 survivors of an acute MI with persistently elevated anti–C. pneumoniae antibody titers (≥1:64) were randomized to receive placebo, a single 3-day course of azithromycin (500 mg/day), or 2 courses 3 months apart. 12 Anti–C. pneumoniae titers fell at 6 months to <1:16 in more patients who received azithromycin than in those who received placebo (43% vs 10%, P = 0.02). Patients who were randomized to azithromycin treatment had an apparent reduction in cardiovascular events (from 28% to 8%, odds ratio = 0.2, P = 0.03) compared with placebo patients and a nonrandomized group with high anti–C. pneumoniae titers. Outcomes were similar with 1 and 2 courses of azithromycin.

The ACADEMIC (Azithromycin in Coronary Artery Disease: Elimination of Myocardial Infection with Chlamydia) trial, 8,13 performed by our group, examined markers of inflammation and subsequent cardiovascular events in 302 seropositive patients randomized to azithromycin (500 mg daily for 3 days, then weekly) or placebo for 3 months. After 6 months, azithromycin reduced a global index of 4 systemic markers of inflammation (C-reactive protein, TNF-alpha, and interleukins-1 and -6) compared with placebo, reaching significance for C-reactive protein and interleukin-6. Antibody titers were unchanged. Cardiovascular events were infrequent and similar in the 2 groups. Clinical events in ACADEMIC were assessed after 2 years. Cardiovascular event rates were not significantly different in treated patients and controls (22 versus 25; hazard ratio, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.5–1.6; P = 0.7), although a trend toward a reduction in events in the azithromycin arm was noted during the 2nd year of the study (hazard ratio, 0.6; CI 0.23–1.5; P = 0.26). 8,13

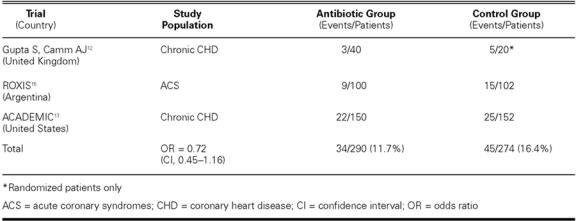

The ACADEMIC results, combined with the 2 previous randomized trials, left open the potential for a modest-to-moderate antibiotic benefit (on the order of 20%–30% event reduction) in CHD and acute coronary syndromes (ACS) (Table I), 14 but this possibility required prospective testing in very large studies.

TABLE I. Early Randomized Antibiotic Trials for Secondary CHD Prevention

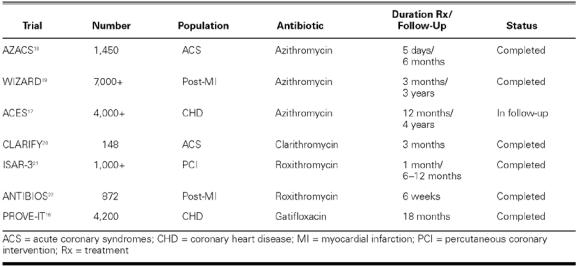

Large Randomized Trials. On the basis of these preliminary study results, a few large trials have been undertaken and completed or are nearing completion, which include a sufficient number of events to determine whether a moderate but clinically evident benefit might accompany antibiotic therapy with azithromycin given for secondary prevention in stable patients with established CHD (Table II). 16,17

TABLE II. Large and Intermediate-Sized Antibiotic Secondary Prevention Trials: Recently Completed and Ongoing

The WIZARD trial (Weekly Intervention with Zithromax for Atherosclerosis and its Related Disorders) enrolled over 7,724 stable patients with a history of MI and seropositivity to C. pneumoniae and randomized them to receive either placebo or 3 months of treatment with azithromycin (600 mg/week). 16,17.19 The primary clinical endpoint was a composite of death, MI, hospitalization for unstable angina, or need for repeat revascularization at 3 years. Overall, short-term (3-month) azithromycin therapy was safe and well tolerated. However, it resulted overall in only a 7%, nonsignificant reduction in the incidence of the primary endpoint. No evidence of a treatment effect by baseline C. pneumoniae titer was observed. However, post-hoc analyses suggested a possible benefit during and shortly after treatment (that is, a 33% reduction in death or myocardial infarction at 6 months, P = 0.03), which was not sustained over the observation period. This raised the question of whether prolonged antimicrobial therapy might produce a more sustained clinical benefit, a hypothesis worth further testing.

Trials of Antibiotics inAcute Coronary Syndromes

The pathophysiology of ACS differs in important aspects from that of chronic CHD progression. Therefore, antibiotic and other anti-inflammatory therapies might have differing and potentially greater benefit in this setting.

The ROXIS (Roxithromycin in Ischemic Syndromes) study, the 1st randomized antibiotic trial in ACS, randomized 202 Argentine patients with unstable angina or non-Q-wave MI to roxithromycin (150 mg twice a day) or placebo for 30 days. 23 At the end of the treatment period, the rates of recurrent ischemia (1.1% vs 5.4%), MI (0 vs 2.2%), and ischemic death (0 vs 2.2%) tended to be lower in the patients treated with roxithromycin (adjusted P = 0.064 for the composite event rate). No major drug-related adverse effects occurred. At 6 months, individual and composite event rates remained lower in the roxithromycin group (8.7% vs 14.6%), but the differences were not significant, perhaps due to limited power. 15

STAMINA (South Thames Trial of Antibiotics in Myocardial Infarction and Unstable Angina), a 2nd randomized antibiotic trial in ACS, 24 randomized 325 patients to one of 3 regimens, each lasting 1 week: 1) azithromycin 500 mg/day, omeprazole 20 mg twice a day, and metronidazole 400 mg twice a day (an anti-Chlamydia regimen); 2) amoxicillin 500 mg twice a day, omeprazole 20 mg twice a day, and metronidazole 400 mg twice a day (an anti-Helicobacter regimen); or 3) placebo. Follow-up extended for 1 year. All patients received standard treatment for CHD. There were no statistically significant differences in frequency or timing of major adverse cardiac events among the azithromycin, amoxicillin, and placebo groups. However, when combined, subjects who received one or the other of the antibiotic-containing regimens had a 36% reduction in major events at 12 weeks compared with placebo (P = 0.02). The benefit persisted through 1 year. Seropositivity to C. pneumoniae or H. pylori did not affect treatment outcome. Given STAMINA's limited size and power, benefits related to the antimicrobial or anti-inflammatory properties of the specific regimens could not be distinguished. Larger clinical trials were recommended.

The effect of antibiotic therapy on the secondary prevention of ACS was also tested in CLARIFY (Clarithromycin in Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients in Finland): 148 patients with acute non-Q-wave MI or unstable angina were randomized to blinded therapy with either clarithromycin or placebo for 3 months. 20 The primary endpoint was a composite of death, MI, or unstable angina during treatment; and the secondary endpoint was occurrence of any cardiovascular event during the entire follow-up period (average, 555 days; range, 138–924 days). There was a trend toward fewer patients meeting primary endpoint criteria in the clarithromycin group (11 versus 19 patients; relative risk, 0.54; CI, 0.25–1.14; P = 0.10). By the end of follow-up, 16 patients in the clarithromycin group and 27 in the placebo group had experienced a cardiovascular event (relative risk, 0.49; CI, 0.26–0.92; P = 0.03). Results were viewed as favorable, although not conclusive, for a treatment benefit of clarithromycin after non-ST-elevation ACS.

The Antibiotic Therapy after Acute Myocardial Infarction (ANTIBIO) study was a prospective randomized study of 872 patients with an acute MI randomized to blinded treatment with either 300 mg roxithromycin or placebo daily for 6 weeks. 22 The primary endpoint of death from all causes at 12 months occurred in 6.5% of the roxithromycin group and 6.0% of the placebo group (odds ratio, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.6–1.9; P = 0.74). There also were no differences in secondary and combined endpoints.

The Azithromycin in Acute Coronary Syndrome (AZACS) study, the largest antibiotic trial to date in ACS (approximately 1,450 patients), was performed at Cedars–Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, and was published in 2003. 18 Patients were entered regardless of whether serology to C. pneumoniae was positive or negative. Treatment was given for only 5 days, and duration of follow-up was 6 months. No benefit upon ischemic endpoints was observed. The AZACS study indicates with reasonable power and reliability that there is no important benefit of this short treatment regimen of azithromycin beginning at the time of ACS. 18

PROVE-IT (Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy) is a study that has enrolled over 3,000 patients who presented with ACS. Randomization followed a 2 × 2 factorial design. 16 Treatments included 1) 1 of 2 statin regimens (pravastatin or atorvastatin) and 2) an intermittent course of gatifloxacin or placebo. The primary endpoint is a composite of major cardiovascular clinical events after at least 18 months of follow-up. The 2 statin therapies have different lipid-lowering potencies but potentially similar anti-inflammatory effects. Quinolone therapy offers potentially superior bactericidal (that is, anti-Chlamydia) activity, compared with the macrolides. PROVE-IT therefore attempts to answer important unresolved questions regarding the role of therapy that targets inflammation and infection in the pathogenesis of ACS and is expected to be completed and presented in 2004.

Can Antibiotics Prevent Restenosis?

Restenosis is a common problem following coronary intervention. Although distinct from native CAD, restenosis after angioplasty also involves excessive pro-liferative, inflammatory, and prothrombotic responses. Cellular infection with C. pneumoniae activates these responses, 25 and infection might be a co-factor in promoting restenosis. 26,27

The ISAR-3 (Intracoronary Stenting and Antibiotic Regimen 3) study investigated roxithromycin, an effective anti-Chlamydia macrolide, for the prevention of restenosis after coronary stent deployment. 21 A total of 1,010 patients who had undergone successful coronary stenting were randomized to receive roxithromycin (300 mg daily for 4 weeks) or placebo. The primary endpoint was the frequency of restenosis (>50%) at 6-month follow-up angiography. A secondary endpoint was target vessel revascularization during the year after stenting. Overall in ISAR-3, there was no significant treatment-related benefit in the 6-month angiographic restenosis rate (roxithromycin, 31%; placebo, 29%), in target-vessel revascularization (19% vs 17%), or in 1-year rates of death or MI (7% vs 6%). However, an interaction was found between C. pneumoniae titers and treatment, both for restenosis and for revascularization. Roxithromycin was favored for patients with high titers (adjusted odds ratio 0.44 for titers ≥1:512) but was ineffective at lower titers. These exploratory results raise the intriguing possibility that antibiotics might be selectively beneficial in a subgroup of patients with active infection, a more vigorous immune response, or both.

Ongoing Antibiotic Studies

Azithromycin and Coronary Events Study (ACES) is an NIH-sponsored, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of azithromycin among adults with stable CHD. 17 The ACES trial does not require seropositivity to C. pneumoniae, although serologic results are assessed. Participants are randomized to azithromycin (600 mg orally once a week for 1 year) or placebo. Follow-up will extend for a mean of 4 years. The primary endpoint is a composite of CHD death, nonfatal MI, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization. Secondary objectives will be to evaluate relationships among antibody titers, inflammatory markers, treatment status, and outcome. More than 4,000 patients have been enrolled in ACES and are into the follow-up period, with results expected within 1 to 2 years.

Other trials involving ACS, MI, or planned bypass surgery are ongoing or planned, and the results will be of interest.

Potential and Limitations of Antibiotic Trials

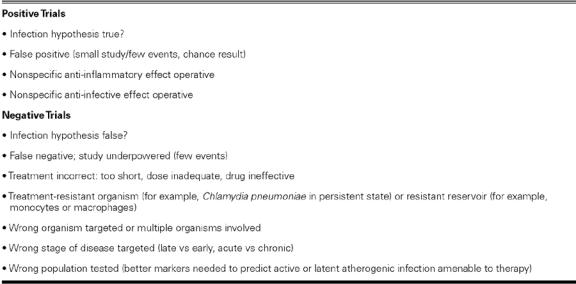

These antibiotic trials have generated enthusiastic expectations for proving (or disproving) the infectious-disease hypothesis of atherosclerosis and establishing new therapies. However, these expectations must be tempered by important limitations and uncertainties (Table III). Negative outcomes might be explained not only by an incorrect hypothesis (that is, infection does not cause CHD) but also by inadequate study size or design or by an ineffective antibiotic regimen. Indeed, Gieffers and colleagues 28 found that C. pneumoniae infecting circulating monocytes was refractory to azithromycin. Blood monocytes from healthy volunteers were obtained before and after oral therapy with azithromycin or rifampin, inoculated with C. pneumoniae, and cultured in the presence of the antibiotic. Circulating monocytes from CHD patients undergoing experimental therapy with azithromycin also were cultured. Antibiotics did not inhibit chlamydial growth within monocytes. After withdrawal of antibiotics, C. pneumoniae could be cultured from the monocyte cell lines. In contrast, antibiotics eliminated C. pneumoniae from epithelial cells.

TABLE III. Proposed Implications and Potential Limitations of Antibiotic Trials

Therefore, prevention or elimination of vascular infection with antibiotics might be problematic if C. pneumoniae that resides in circulating monocytes, which can carry and disseminate the organism, is antibiotic resistant. Negative antibiotic studies might be explained if reactivation of C. pneumoniae from a persistent state, stimulation of proinflammatory mediator production, or promotion of atherosclerosis can occur despite an “effective” course of antibiotics.

In contrast, if studies are positive, the hypothesis still is not entirely proved, because a nonspecific anti-inflammatory effect or an anti-infective action against other organisms might be operative. This situation already has arisen in attempting to explain the benefits of minocycline therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. 29 Consequently, the infectious theory of atherosclerosis does not lend itself well to proof by means of Koch's classical postulates. Hence, new and innovative experimental approaches, in addition to traditionally designed antibiotic trials, should be welcome in our attempts to gain adequate insight into the role of infection in atherosclerosis and its therapy. Meanwhile, clinical trial data to date have not provided adequate support for the clinical use of antibiotics in primary or secondary prevention of CHD.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Jeffrey L. Anderson, MD, University of Utah School of Medicine, Cardiovascular Department, LDS Hospital, 8th Avenue and C Street, Salt Lake City, UT 84143

E-mail: jeffrey.anderson@ihc.com

This paper was invited following the First Symposium on Influenzaand Cardiovascular Disease: Science, Practice, and Policy, held on 26 April 2003, at the Texas Heart Institute, Houston, Texas.

References

- 1.Ross R. Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 1999;340:115–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Anderson JL, Muhlestein JB. Acute coronary syndromes: the role of infection. In: Theroux P, editor. Acute coronary syndromes: a companion to Braunwald's heart disease. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003. p. 88-107.

- 3.Chirgwin K, Roblin PM, Hammerschlag MR. In vitro susceptibilities of Chlamydia pneumoniae (Chlamydia sp. strain TWAR). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1989;33:1634–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Schneider CA, Diedrichs H, Riedel KD, Zimmermann T, Hopp HW. In vivo uptake of azithromycin in human coro-nary plaques. Am J Cardiol 2000;86:789–91, A9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Muhlestein JB, Anderson JL, Hammond EH, Zhao, L, Trehan S, Schwobe EP, Carlquist JF. Infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae accelerates the development of atherosclerosis and treatment with azithromycin prevents it in a rabbit model. Circulation 1998;97:633–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Fong IW. Value of animal models for Chlamydia pneumoniae-related atherosclerosis. Am Heart J 1999;138(5 Pt 2): S512-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Havlir DV, Dube MP, Sattler FR, Forthal DN, Kemper CA, Dunne MW, et al. Prophylaxis against disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex with weekly azithromycin, daily rifabutin, or both. California Collaborative Treatment Group. N Engl J Med 1996;335:392–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Anderson JL, Muhlestein JB, Carlquist J, Allen A, Trehan S, Nielson C, et al. Randomized secondary prevention trial of azithromycin in patients with coronary artery disease and serological evidence for Chlamydia pneumoniae infection: The Azithromycin in Coronary Artery Disease: Elimination of Myocardial Infection with Chlamydia (ACADEMIC) study. Circulation 1999;99:1540–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Fish DN, North DS. Gatifloxacin, an advanced 8-methoxy fluoroquinolone. Pharmacotherapy 2001;21:35–59. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Meier CR, Derby LE, Jick SS, Vasilakis C, Jick H. Antibiotics and risk of subsequent first-time acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 1999;281:427–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Jackson LA, Smith NL, Heckbert SR, Grayston JT, Siscovick DS, Psaty BM. Past use of erythromycin, tetracycline, or doxycycline is not associated with risk of first myocardial infarction. J Infect Dis 2000;181 Suppl 3:S563-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Gupta S, Camm AJ. Chronic infection in the etiology of atherosclerosis—the case for Chlamydia pneumoniae. Clin Cardiol 1997;20:829–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Muhlestein JB, Anderson JL, Carlquist JF, Salunkhe K, Horne BD, Pearson RR, et al. Randomized secondary prevention trial of azithromycin in patients with coronary artery disease: primary clinical results of the ACADEMIC study. Circulation 2000;102:1755–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Muhlestein JB. Antibiotic treatment of atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol 2003;14:605–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Gurfinkel E, Bozovich G, Beck E, Testa E, Livellara B, Mautner B. Treatment with the antibiotic roxithromycin in patients with acute non-Q-wave coronary syndromes. The final report of the ROXIS Study. Eur Heart J 1999;20:121–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Dunne M. WIZARD and the design of trials for secondary prevention of atherosclerosis with antibiotics. Am Heart J 1999;138(5 Pt 2):S542-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Grayston JT. Secondary prevention antibiotic treatment trials for coronary artery disease. Circulation 2000;102:1742–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Cercek B, Shah PK, Noc M, Zahger D, Zeymer U, Matetzky S, et al. Effect of short-term treatment with azithromycin on recurrent ischaemic events in patients with acute coronary syndrome in the Azithromycin in Acute Coronary Syndrome (AZACS) trial: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003;361:809–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.O'Connor CM, Dunne MW, Pfeffer MA, Muhlestein JB, Yao L, Gupta S, et al. Azithromycin for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease events: the WIZARD Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290:1459–66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Sinisalo J, Mattila K, Valtonen V, Anttonen O, Juvonen J, Melin J, et al. Effect of 3 months of antimicrobial treatment with clarithromycin in acute non-q-wave coronary syndrome. Circulation 2002;105:1555–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Neumann F, Kastrati A, Miethke T, Pogatsa-Murray G, Mehilli J, Valina C, et al. Treatment of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection with roxithromycin and effect on neointima proliferation after coronary stent placement (ISAR-3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2001; 357:2085–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Zahn R, Schneider S, Frilling B, Seidl K, Tebbe U, Weber M, et al. Antibiotic therapy after acute myocardial infarction: a prospective randomized study. Circulation 2003; 107:1253–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Gurfinkel E, Bozovich G, Daroca A, Beck E, Mautner B. Randomised trial of roxithromycin in non-Q-wave coronary syndromes: ROXIS Pilot Study. ROXIS Study Group. Lancet 1997;350:404–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Stone AF, Mendall M, Kaski JC, Gupta S, Camm J, Northfield T. Antibiotics against Chlamydia pneumoniae and Helicobacter pylori reduce further cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndromes [abstract]. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37(2 Suppl A):349A.

- 25.Dechend R, Maass M, Gieffers J, Dietz R, Scheidereit C, Leutz A, Gulba DC. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection of vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells activates NF-kappaB and induces tissue factor and PAI-1 expression: a potential link to accelerated arteriosclerosis. Circulation 1999; 100:1369–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Zhou YF, Leon MB, Waclawiw MA, Popma JJ, Yu ZX, Finkel T, et al. Association between prior cytomegalovirus infection and the risk of restenosis after coronary atherectomy. N Engl J Med 1996;335:624–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Zhou YF, Csako G, Grayston JT, Wang SP, Yu ZX, Shou M, et al. Lack of association of restenosis following coronary angioplasty with elevated C-reactive protein levels or seropositivity to Chlamydia pneumoniae. Am J Cardiol 1999; 84:595–8, A8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Gieffers J, Fullgraf H, Jahn J, Klinger M, Dalhoff K, Katus HA, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in circulating human monocytes is refractory to antibiotic treatment. Circulation 2001;103:351–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Tilley BC, Alarcon GS, Heyse SP, Trentham DE, Neuner R, Kaplan DA, et al. Minocycline in rheumatoid arthritis. A 48-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. MIRA Trial Group. Ann Intern Med 1995;122:81–9. [DOI] [PubMed]