Abstract

René G. Favaloro moved to the Cleveland Clinic in 1962 and with him came a wind of change that was to reshape cardiac surgery forever. With his cherished colleagues, Effler, Sones, Proudfit, Groves, Sheldon, and countless others, he contributed to the double internal mammary artery–myocardial implantation by the Vineberg method, and, subsequently, in May 1967, he reconstructed the right coronary artery by saphenous vein graft interposition. These milestones set the stage for aortocoronary saphenous vein bypass grafting in October 1967. Several other breakthroughs rapidly followed: the application of the bypass technique to the left coronary artery, the combination of coronary artery bypass grafting with left ventricular reconstruction and valve repair or replacement, and finally, by December 1967, a double bypass to the right coronary artery and the anterior descending branch of the left coronary artery. Emergency coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with acute myocardial infarction soon became Favaloro's next focus. In 1970, he was influenced by the work of George Green in New York City and began using the direct mammary–coronary anastomosis with a few modifications, which popularized it.

In June 1971, Favaloro decided to leave the Cleveland Clinic and return to Argentina, where he created a medical center, a teaching unit, a research department, and, finally, an Institute of Cardiology and Cardiovascular Surgery.

To all these medical achievements, add integrity, courage, honesty, and humility, and the result is a man who will never be forgotten.

Key words: Argentina; history of medicine, 20th cent.; myocardial revascularization/history; coronary artery bypass/history; heart valve diseases

Yet don't let anyone take offense,

I don't plan any folks to gall;

If I've chosen this fashion to have my say,

It's because I thought it the fittest way,

And it's not to make trouble for any man,

But just for the good of all.

This last stanza of the Argentine national poem, Mart'n Fierro, was quoted by René Favaloro in a public tribute to Paul Dudley White, 2 but its application to Dr. Favaloro himself is at least as accurate, for it describes those exquisite traits that characterized him as a human being, over and above his pioneering exploits in cardiac and cardiovascular surgery. His fierce pursuit of the common good and his poignant honesty have made him unique. Four years after his death, those who knew him—and those who wish they had—still regret his passing.

The Molding

René Gerónimo Favaloro (Fig. 1) was born in the city of La Plata, capital of the province of Buenos Aires, about 30 miles to the south of the city of Buenos Aires, the federal capital of the Argentine Republic. He was the grandson of Italian immigrants, Sicilian on his father's side, and Tuscan on his mother's. 3 His father was a carpenter (“cabinetmaker” 4), who died in 1982 at the age of 86, and his mother a dressmaker. René had acquired from his father the skill of carving simple pieces of wood into beautiful furniture. In a little workshop, working shoulder to shoulder with his father, he had also acquired the principle that would guide him for the rest of his life: “only by persistent efforts, with passion and honesty, will our dreams come true.” 4

Fig. 1 Dr. René Gerónimo Favaloro (1923–2000). This photograph was taken at a symposium held in Cleveland, sponsored by the Clinic's Thoracic & Cardiovascular Surgery Department on 12–13 November 1992 to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Dr. Favaloro's pioneering coronary artery bypass graft at the Cleveland Clinic.

(Photo courtesy of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.)

His maternal grandmother injected into the young René an enduring love for nature and, most importantly, for his native land—a love that was to shape his adult life inexorably. The other stirring influence in his early years was an uncle who was a general medical practitioner. René keenly accompanied his uncle on his daily rounds, and it was this crude exposure to the reality of a doctor's life that kindled in him the strong wish to pursue a medical career. 3

He received his secondary education in the famous Colegio Nacional de La Plata, which in those days was staffed by some of the most outstanding minds in Latin America, including Ezequiel Mart'nez Estrada and Pedro Henr'quez Ureña. 5 They transmitted to their students the dream of a solid, unified Latin America, a magna patria devoted entirely to social justice.

The fundamental idea of the program elaborated in 1924 was that of forming integral men with solid principles based on deeply humanistic grounds … who, beyond knowledge of art and science, would once and for all understand that to live in liberty and to respect justice are the essentials of our lives; that ethics and morals always demand that we fight for the dignity of man; that each person has a right to his or her individuality, but is obliged … to participate and to try to improve society …. 5

The warm relationship between student and teacher enabled this fortunate group of students to develop an aesthetic sensibility and sound scientific knowledge. It was an unforgettable period, which Dr. Favaloro cherished tremendously and to which he always referred with pride and great pleasure.

He graduated from high school in the upper third of his class and then commenced his studies in the Medical Science faculty of La Plata University 3 in 1941, together with another 120 students. 5 He was immediately drawn to surgery and attended the classes and rounds of the great surgeons of the time, long before his scheduled program of study required him to do so. He presented his thesis and graduated at the top of his class in 1948, with the title of Doctor in Medicine.

By this time, Favaloro was the fervent disciple of 2 great Argentine masters of surgery, professors Federico Christmann and José Mar'a Mainetti, and had begun to foster a profound interest in thoracic surgery. This led him to travel to Buenos Aires every week in order to participate in the postgraduate course on pulmonary and esophageal surgery 3: “I started travelling every Wednesday 44 miles to the Rawson Hospital in Buenos Aires, where the Finochietto brothers had organised a postgraduate program, mainly to learn lung and oesophageal resections.” 4

The time was ripe for Dr. Favaloro to develop a career as a distinguished thoracic surgeon, but unfortunately this order of events was altered by the political climate of the time. After lengthy thought, he resolved to resign his hospital post rather than forfeit his principles of ethical and academic liberty. 3 An anti-Peronist, he decided to practice far from Buenos Aires 6: “… the main one [reason] being my refusal to sign a political declaration supporting the ‘national doctrine,’ an essential requirement at the time for any position at the University Hospital, …” 4

These social circumstances led him to fill in for a country doctor whose practice was centered around Jacinto Aráuz, a small town southeast of the province of La Pampa. His original intent was to stand in for his colleague only until the latter recovered his health, but the primitive conditions of life that Dr. Favaloro encountered during his daily visits awakened his social conscience. Therefore he chose to stay on in an effort to improve the quality of health care in the area. 3

In 1950, he married his beloved Mar'a Antonia (Fig. 2) in La Plata. She was to become his lifelong source of courage and comfort.

Fig. 2 René Favaloro and his wife, Mar'a Antonia, preparing an “asado,” the typical Argentine barbecue, while they lived in Cleveland.

(Photo courtesy of the Favaloro Foundation.)

Thousands of patients were operated on during the years spent in Jacinto Aráuz, and almost all originated from 3 villages that had been settled by German Protestants and Jewish cowboys. 6 Most of these patients lived in very poor conditions—a fact that left a permanent imprint on Dr. Favaloro. He was engrossed in this mission for 12 long years, from 1950 until 1962. In 1952, he was joined by his brother Juan José Favaloro, after the latter's graduation from medical school. Through his dedicated work in Jacinto Aráuz, René struggled to improve his patients' quality of life. “I was following the basic principle that I had been taught at my university—that every graduate has a social commitment.” 3

While practicing as a country doctor, he engaged in many novel and exciting tasks. He experimented with preventive medicine at its most basic level, diligently teaching his patients the basic rules of hygiene. He took it upon himself to establish the first blood donation facility in the area. It was a truly mobile blood bank: Dr. Favaloro knew where donors in each blood group lived and would call upon them whenever the need arose. He also developed his own operating room and used his superb teaching skills to train general and surgical nurses. 3 “With tremendous effort and by saving every penny, I was able to build up, from an old house, a clinic with operating facilities, laboratory, and X-ray equipment.” 4

During this time, René sought to keep himself abreast of ongoing advances in thoracic surgery, in particular the development of the Gibbon heart-lung machine, by means of regular painstaking journeys to Buenos Aires and La Plata, and by reading all the most prominent journals. 7

Dr. Favaloro's love for his native land never faltered during his time spent in Jacinto Aráuz. Often while on his way home after a day spent in the clinic, he would halt his old car on some desolate country road to watch the beautiful sunsets of the pampas. Time and time again he would stand enthralled by the constantly changing iridescent colors of the fiery sky, while his “dreams and utopias intermingled with the clouds.” 2

The Lure of a Dream

The early contributions in cardiovascular surgery during the 1950s made a great impression on me, and although our work was gratifying, in 1960 I began to cherish the idea of travelling to the United States to train in thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. I talked to my master Professor Mainetti, who understood my feelings. 4

Sometime between the years 1959 and 1962, Prof. Mainetti (founder of a cancer institute in La Plata) visited his friend, Dr. George Crile, Jr., a cancer surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic (Fig. 3). When Dr. Favaloro expressed an interest in cardiac surgery, Prof. Mainetti confidently recommended the Cleveland Clinic, in view of the clinic's assiduous commitment to cardiac research and the presence of such pioneers as Dr. F. Mason Sones and Dr. Willem Kolff.*

Fig. 3 The Cleveland Clinic, 22 August 1949. Its appearance from this perspective was essentially the same when Dr. Favaloro joined the Clinic in 1962.

(Photo courtesy of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.)

Prof. Mainetti kindly wrote to Dr. Crile in behalf of Dr. Favaloro on 2 occasions, but with no response. Finally, in February 1962, Dr. Favaloro visited Dr. Crile in Cleveland, accompanied by his wife, arriving unannounced.* “I was 38 years old, and I had as a treasure the large experience accumulated in hundreds and hundreds of operations.” 4

Dr. Crile called upon Dr. Donald B. Effler, head of cardiac surgery. At the time, the department of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery consisted of Dr. Effler and his partner, Dr. Laurence K. Groves, in addition to a senior and junior resident. 7 Dr. Effler appeared willing to accept Dr. Favaloro as a special trainee.*

In my broken English I managed to explain the reason for my trip. Effler made it clear that not having the proper qualifications, mainly the certificate of the Educational Council of Foreign Medical Graduates, I could only be accepted as an observer, without receiving any payment. Because I had been able to save money, I pointed out that I was not asking for a salary but for an opportunity to learn. 4

Dr. Effler readily sent him to the chairman of education for an interview and to make all the necessary arrangements. Unfortunately, the chairman had recently had problems with another Argentine cardiac fellow, who had abruptly left the Cleveland Clinic, so he was reluctant to accommodate an uninvited candidate with no credentials and dismissed him. Dismayed by this uncanny sequence of events, Favaloro called Crile, who in turn called Effler. The next day Favaloro was enrolled as an observer until he succeeded in passing his Educational Council of Foreign Medical Graduates examination. During this time, he rented a small apartment in a rather impoverished neighborhood adjacent to the Clinic, and worked incessantly.*

Only 3 or 4 open-heart operations per week, mainly for congenital diseases, were performed. Within 2 weeks, Effler invited me to scrub up in a left pneumonectomy [Fig. 4]. From then on, I collaborated with him and Dr. Larry Groves, his partner. In addition, I placed Foley catheters, pushed beds back and forth to the intensive care unit according to Effler's rules … helped the anaesthetists, and also cleaned, siliconized, and helped assemble the enormous heart-lung machine with a Key-Cross oxygenator. I did everything possible to show my gratitude. 4

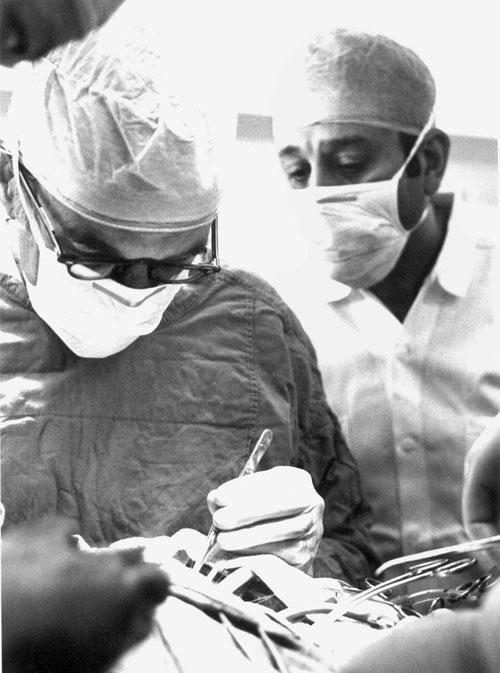

Fig. 4 Drs. Favaloro (at right) and Effler in the operating room. Dr. Effler donated this photograph to Dr. Favaloro after the latter submitted his resignation from Cleveland Clinic in 1971. He added a dedication to the photo, which read, “We have taught each other many things.”

(Photo courtesy of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.)

Early during his residence at the Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Favaloro was drawn to the work of Mason Sones, Jr., Earl K. Shirey, and their collaborators in the catheterization laboratory in the basement room (the famous B10), where hundreds of cine coronary angiograms were systematically stored, together with a summary of the clinical record of each patient. At the time, studies of such precision and quality were available only at the Cleveland Clinic. 8 On 1 memorable occasion, René humbly introduced himself to Dr. Sones, whom he recalls was always “willing to exchange ideas with his associates and innumerable visitors that came from all over the world.” 4 Thereafter, he regularly asked Dr. Sones for guidance in interpreting some of the cineangiograms that he could not understand due to his lack of experience, and “that was the beginning of a deep and everlasting friendship” 4 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Dr. Favaloro (left) with Dr. Sones in the cardiac catheterization laboratory circa 1982, during one of Favaloro's visits to the Cleveland Clinic.

(Photo courtesy of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.)

René looked upon Dr. Sones as the indisputable leader. In later years, he would indulge in reminiscence of that 1st meeting and the special friendship that stemmed from it: “I have always thanked God for having given me the opportunity to share my duties with him.” 4

After finishing the day's work in the department of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery, he would spend most of his time down in B10, slowly learning how to interpret the cine coronary angiograms, and sometimes he would prolong his review of films until late at night.

Dr. Favaloro soon passed his Educational Council of Foreign Medical Graduates examination, and went on to become a junior fellow in 1963 and a senior resident in 1964. 4

The Golden Years

Just before Favaloro's arrival at the Cleveland Clinic in 1962, 2 important events had occurred. First, on 5 January 1962, Dr. Effler and his associates had successfully operated on a severe obstruction at the left main coronary artery 9 using the patch-graft technique described by Åke Senning. 10 The 1st patch operations were performed using a pericardial graft to enlarge the lumen of the left main coronary artery. Second, on 12 January 1962, Dr. Sones examined a patient who had been operated upon in Canada by means of the Vineberg procedure (1st described in 1946)*. Using selective cannulation of the left internal mammary artery, he showed that collateral circulation from that systemic artery implanted into the myocardium was sufficient to diminish the myocardial perfusion deficit in the territory of an occluded left anterior descending coronary artery. This was the 1st objective evidence of the efficacy of the Vineberg operation, which was an old but not widely accepted antecedent of coronary artery bypass grafting. Therefore, by 1962, myocardial revascularization had started both with a direct approach in localized proximal obstructions by means of the patch-graft technique (pericardium or saphenous vein) and with an indirect approach by means of the left internal mammary artery implant. In light of this, Dr. Effler and the Cleveland Clinic were strongly motivated toward a surgical solution to coronary artery disease at the time that Dr. Favaloro joined the team.

William L. Proudfit (Fig. 6) and his collaborators at Cleveland had analyzed hundreds of cine angiograms and their correlations with clinical histories, 11 which provided valuable insight into the indications for many surgical procedures. After a few months of reviewing cine coronary angiograms, Dr. Favaloro saw that there were 2 distinct groups of coronary patients: those with diffuse disease that involved most of the coronary branches and those with localized obstructions (mainly at the proximal segments of the coronary arteries) but good distal run-off. 4 The idea of working directly on the coronary arteries of this 2nd group of patients encouraged Favaloro to attempt bypass of the obstructions. 7

Fig. 6 Dr. Favaloro (left) with Dr. Proudfit at the Clinic's alumni reunion in October 1999.

(Photo courtesy of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.)

At the time of his debut at the Cleveland Clinic, indirect myocardial revascularization using the left internal mammary artery by means of a left posterolateral thoracotomy was being practiced with gratifying overall results. 12 In 1965, in accordance with William H. Sewell's ideas, 13 the procedure was modified so that the internal mammary artery was dissected as a pedicle, including both fat and connective tissue. This resulted in a shorter dissecting time and less trauma.

Once the median sternotomy became the standard approach for most heart operations, Favaloro could see and palpate the mammary arteries when lifting the sternum to place the Finochietto retractor. This inspired him to use both arteries for implantation by the Vineberg method. He discussed the idea with Sones on several occasions, but it was suggested that necrosis might occur if the sternum was deprived of that blood supply. 7

I carefully reviewed the anatomy to confirm that this was a senseless warning. In 1966 … I dissected both mammary arteries and implanted the right one on the anterolateral wall of the left ventricle parallel to the anterior descending branch and the left one on the lateral wall underneath the branches of the circumflex and right coronary artery. 14–16 To facilitate the dissection, I designed a self-retaining retractor 17,18 [Fig. 7], that with some modifications, is still used today in cardiovascular centres all over the world. 4

Fig. 7 The Favaloro retractor was designed to lift the left side of the sternum, giving good exposure of the left mammary artery.

(From: Favaloro RG. 14 Reproduced courtesy of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.)

Concomitantly, direct myocardial revascularization was being carried out in segmental localized obstructions, as mentioned above, by the pericardial or venous patch-graft technique 19,20 (Fig. 8). Drs. Effler, Sones, Favaloro, and Groves had decided to perform coronary endarterotomy in combination with their patch-graft reconstructions. Endarterectomy was feared in view of the risk of dissection of the diseased vessel. Therefore, the involved segment of a coronary artery was incised, dilated by applying the technique of transluminal dilation, and reconstructed with strips of pericardium. This use of patch-graft reconstruction produced good results on the right coronary artery, but not so in treating left main trunk obstruction, 21 where 11 deaths occurred out of a total of 14 patients. 7 “In those years I used to go to the operating room with both the thrill of challenge and fear in my soul.” 4 With increasing experience, reconstructions were performed with longer patches. Sones's postoperative angiograms showed that there was a direct relationship between the length of the repair and postoperative thrombosis: that is, the longer the repair, the greater the failure. This was the consequence of the coronary artery being untouched in the process of endarterotomy, so that its inner surface retained irregularities that could disturb the flow pattern. The turbulence induced thrombosis and consequent occlusion. The greatest disadvantage of this technique therefore lay in the fact that the arteriosclerotic plaque was allowed to remain in place, often progressing or serving as a nidus for thromboembolic occlusion.

Fig. 8 Drawing shows pericardial patch-graft being secured with fine arterial silk sutures.

(From: Effler DB, et al. 19 Reproduced courtesy of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.)

Early in 1967, I thought that perhaps the problem could be solved by use of segments of saphenous vein. At the Cleveland Clinic, we had gathered a broad experience in peripheral and renal artery reconstruction with that kind of graft. Why not use it at the coronary level? 4

Dr. Favaloro's 1st such operation was performed on 7 May 1967 on a 51-year-old woman, who was referred to him by his colleague Dr. David Fergusson, and consisted of a right coronary artery reconstruction by saphenous vein graft interposition (in which the obstructed segment was excised and continuity re-established by 2 end-to-end anastomoses). Postoperative arteriographic evaluation of the interposed vein graft demonstrated the obvious advantages of this approach 22:

Mason was very anxious to restudy the patient, and he did so 8 days later. He called me and as soon as I finished an operation, I went to the cardiac laboratory. Mason showed me the film on the Tage-Arno viewer. I had rarely seen him so happy. The right coronary artery had been totally reconstructed, and there was an excellent distal runoff. 4

Recatheterization 10 years later showed that both the graft and the right coronary artery were still patent. Despite the initial enthusiasm, the limitations of the interposed saphenous vein technique soon became apparent. The interposed vein graft was largely applicable to occlusive disease in the mid-portion of the dominant right coronary artery. Its successful application required a luminal caliber of the artery, above and below, that would assure 2 satisfactory end-to-end anastomoses. It seemed most unlikely, therefore, that the interposed saphenous vein graft could ever be applied successfully to the left coronary artery, except for replacement of a sharply localized obstruction in the proximal circumflex branch. Because arteriographic evaluation of a large series of patients had shown that the pattern of coronary occlusive disease favors proximal location, it was evident that the interposed vein graft was least useful where it was most needed. For this reason, Favaloro and his coworkers turned to the concept of aortocoronary saphenous vein bypass grafts.

The 1st bypass from the anterolateral wall of the aorta to the distal end of a resected segment of the right coronary artery using end-to-end anastomosis was carried out on 5 September 1967, and this was subsequently attempted in a series of other patients, before the procedure was changed to an end-to-side anastomosis with the coronary artery at a point distal to the blockage 7 (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9 Schematic illustrations demonstrate the principles of the bypass saphenous vein graft as applied to the dominant right coronary artery. Left: The first bypass vein grafts in the Cleveland Clinic series used a distal end-to-end vein-to-artery graft. The right coronary artery was transected, but the proximal marginal branches were not disturbed. Right: This illustrates the bypass vein graft with end-to-side vein-to-artery anastomosis.

(From: Effler DB, et al. 22 Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.)

It is generally considered that the 1st end-to-side bypass vein graft was carried out at the Cleveland Clinic, on 19 October 1967,* on the 15th patient of the aforementioned series. 23 This technique had distinct advantages, in that the coronary arteriotomy could be lengthened or shortened so that the length of the anastomosis could be tailored to match either the diameter of the coronary artery at that point or the diameter of the venous conduit.* This was intended to prevent the anastomosis from impeding flow. In addition, this form of bypass graft enabled retrograde flow into the proximal coronary artery and its marginal branches. 22 It was also simpler than the end-to-end anastomosis and soon became the enduring technique.

In all fairness, it should be pointed out that Dudley Johnson was doing similar work at Marquette during the same period and published his results 24 in 1969 shortly after Favaloro's paper appeared. In fact, the 1st aortocoronary bypass operation had been carried out on 23 November 1964, by Edward Garrett, while working with DeBakey, using a saphenous vein. 25 Garrett performed the bypass graft in order to wean a patient from cardiopulmonary bypass. The procedure was deemed unsuccessful when the patient sustained a perioperative infarction, and the case went unreported until the bypass was restudied by angiography 8 years later. On this occasion, in 1972, the bypass was in fact found to be still patent, but by this time several years had elapsed since Favaloro had described successful bypass surgery at the Cleveland Clinic.*

In 1968, Favaloro and his team contributed to the establishment of some very important landmarks:

The bypass technique was applied to the left coronary artery distribution. The 1st operation was performed on a patient with severe obstruction of the left main trunk and minimal changes on the left anterior descending and circumflex branches (Fig. 10). A single bypass to the proximal segment of the left anterior descending branch showed excellent perfusion of the entire left coronary artery in the postoperative study; left main artery disease had finally been defeated. 4 By the end of 1968, the largest series in the world of direct myocardial revascularizations, totaling 171 patients, had been accumulated by Favaloro's team at the Cleveland Clinic, 26 and in 1969, promising results on mid-term survival, compiled by Dr. William C. Sheldon and colleagues, 27,28 provided them with the optimal dose of confidence needed to persevere in their work.

Coronary artery bypass grafting was combined with left ventricular reconstruction (aneurysmectomy or scar tissue resection 29).

Coronary artery bypass grafting with concomitant valve repair or replacement was achieved. 30

In December, a double bypass to the right coronary artery and anterior descending branch of the left coronary artery was performed, which opened the door to multiple bypasses in patients with multiple vascular obstructions. Previously, in March of 1968, Dr. Favaloro had performed a double reconstruction with the interposed technique. 20

Emergency coronary artery bypass grafting was performed in patients during acute myocardial infarction. 31,32 The 1st bypass graft for acute myocardial infarction was carried out shortly after the onset of infarction.*

Fig. 10 Left: Application of the bypass vein graft to the left coronary artery follows 2 basic indications: a major occlusion at the ostium of the left main coronary artery or at the origin of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Right: Bypass graft technique applied to the left coronary artery.

(From: Effler DB, et al. 22 Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.)

After evaluating the literature derived from Braunwald, Sonnenblick, and collaborators, 33–37 and in particular an experimental study by Cox and collaborators, 38 Dr. Favaloro convinced himself that if good, oxygenated blood could be supplied in the early hours of a myocardial infarction (coronary artery bypass grafting was capable of accomplishing just that), the muscle could recuperate. He shared these ideas with the other members of his team.

In those days, the team's work was limited by the availability of only 3 operating rooms. As a consequence, patients waited for up to 2 or 3 months to be operated upon. To ameliorate this unfortunate state of affairs, those with life-threatening obstructions were housed in the Bolton Square Hotel across the street from the Cleveland Clinic, to be admitted immediately to the hospital, should a cancellation arise in the daily surgical schedule.

I used to arrive at the Cleveland Clinic at ∼7 am. One day one of the residents told me that a patient in whom a previous cine coronary angiogram showed a subtotal occlusion in the very proximal segment of a large anterior descending artery was in trouble at the hotel. We quickly went to see him …. It was very clear that he had suffered an AMI … I summarised to him [Dr. Sones] the major experimental contributions that supported my intention to perform an emergency CABG and that I did not consider my suggestion an adventure. Finally, Mason acceded. 4

The patient was therefore rushed to the operating theatre, anesthetized, and operated upon. The next day he was extubated and had an uneventful recovery. When he was restudied within 10 days, the cine left ventriculogram demonstrated a small, localized area of deterioration on the anterolateral wall; remarkably, the left ventricular end-diastolic pressure was normal.

This indeed was a gratifying experience …. When I wrote the monograph in 1970, in the chapter dedicated to this subject I predicted: “Personally, I do hope that in the future, patients with acute myocardial infarction will be treated in the same way as those patients with a ‘dead leg’ from acute thrombosis or embolization of the peripheral circulation are now treated.” 4

Within a year, Favaloro and Sones reported the treatment by coronary bypass of 18 impending myocardial infarctions and 11 acute infarctions. They concluded that when surgery is performed within 6 hours of acute myocardial infarction, most of the heart muscle can be preserved. 7

On the occasion of the Sixth Annual Meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons in Atlanta (January 1970), 39 the team for the 1st time reported that the coronary arteries, chiefly the left anterior descending artery, could occasionally be found buried within the myocardial muscle.

Subsequently, in April 1970 at the Fifth Annual Meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, in Washington, DC, 40 Dr. Favaloro was appointed to read the presentation. It dealt with the application of the coronary bypass technique to the left coronary artery and its divisions. In addition, the use of the cephalic or basilic arm veins as an alternative to an unavailable saphenous vein was amply discussed.

In 1970, Favaloro was influenced by the superb work of George Green in New York City 41 and began using the direct mammary–coronary anastomosis. During one of his several encounters with Dr. Green, the latter had remarked that it would take René at least 100 hours in the laboratory to master the use of the microscope, which Green used rigorously in all his anastomoses. Because Dr. Favaloro thought this approach would never popularize mammary–coronary bypass, he decided to dissect the left mammary artery and connect it to the anterior descending artery via the routine interrupted suture technique, with only the help of the lenses that he conventionally used in his daily work. After Favaloro's departure from the Cleveland Clinic in 1971, Dr. Loop and associates standardized this method and demonstrated its excellent results on long-term follow-up. 4

In 1970, Favaloro—together with Ray Heimbecker, Arthur Vineberg, and Charles Friedberg—was invited to participate in the Sixth World Congress of Cardiology held at the Royal Festival Hall and Queen Elizabeth Hall in London. On that occasion, Friedberg voiced some doubts about “such a low mortality,” after Favaloro stated the number of procedures performed at the Cleveland Clinic and the postoperative mortality rates. Evidently Friedberg had some difficulty in accepting the astounding results. “I flared up and invited anybody who so desired to go to the Cleveland Clinic to check our files. Some physicians did visit us on their way back to their native countries and were able to confirm the honest work performed at our institution.” 4

During that same week, Donald Ross invited René to perform some operations at the National Heart Hospital in London. Thus, with the help of Dr. Ross, Favaloro carried out the 1st coronary artery bypass in England. “Most of the outstanding cardiovascular surgeons from Europe watched the surgery from behind us, almost on top of our shoulders, and participated in informal discussions between operations, most of them held in a pub opposite the hospital, where we exchanged knowledge and friendship.” 4

Argentina Reclaims Its Hero

In 1970 I decided to return to my home country. It was a difficult decision. I gave serious thought to this matter and finally considered that my work and my duties were needed in Latin America. One day in October, late in the afternoon, I wrote my letter of resignation to Effler. I closed the envelope with tears in my eyes and left it on his desk. I wrote: “… as you know, there is no real cardiovascular surgery in Buenos Aires …. Destiny has put on my shoulders once more a difficult task. I am going to dedicate the last one third of my life to build a thoracic and cardiovascular centre in Buenos Aires. At this particular time, the circumstances indicate that I am the only one with the possibility of doing it. The department will be dedicated, beside the medical care, to postgraduate education with residents and fellows, postgraduate courses in Buenos Aires and the major cities inside the country, and clinical research. As you can see, we will follow Cleveland Clinic principles. Money is not the reason for my departure. If that would be the main issue, I would take into consideration the offers made constantly to me from different places inside the U.S.A. The main purpose is to develop a well-organized service where I can train surgeons for the future.

Believe me, I would be the happiest fellow in the world if I could see in the coming years a new generation of Argentineans working in different centres all over the country able to solve the problems of the communities with high quality medical knowledge and skill.

I know all the difficulties involved because I have practised before in Argentina. At age 47, the logical and realistic resolution would be to remain at the Cleveland Clinic. I know I am taking the difficult road. You might remember Don Quixote was Spanish. If I do not accept the position as Head of that department in Buenos Aires, I will be living the rest of my life thinking of myself as a good solid s. of a b. My conscience would constantly be telling me, ‘You chose the easy way’.” 4

Departing from the Cleveland Clinic and his beloved colleagues there was a momentous task. Dr. Sones would not accept his decision to leave. He couldn't fathom working at the Cleveland Clinic without his greatest comrade. Staff from all over the Cleveland Clinic, nurses and technicians alike, beckoned him to stay.

Finally I decided to escape. I told everybody I was leaving at the end of June or the beginning of July 1971. However, I accepted an invitation to lecture in Boston in the middle of June, and from there my wife and I left for Argentina. Only my secretary, Candice, a lovely young lady, knew my secret, and she was brave enough to keep it. I wrote letters to Effler and Sones. Effler accepted my decision, which “avoided a painful goodbye or farewell.” Mason, once again, thought I was crazy. 4

Dr. Favaloro was welcomed warmly in Argentina as a famous surgeon and soon became a local hero. He initially worked as Chief of Cardiac Surgery at Clinica Güemes, a general surgical clinic. René's brother, Juan José, worked with him at the Hospital Güemes from 1971 until 1976, the year of his death in a tragic accident. After this time, René became the surrogate father to his brother's 4 children, 2 of whom became physicians.* René and his brother had together created the Favaloro Foundation in 1975, thereby achieving the 3 goals listed in the resignation letter to Dr. Effler: those of providing medical care, generating scientific knowledge, and educating health professionals.

In 1980, Favaloro and his team carried out the 1st heart transplantation in Argentina, and in the same year he also succeeded in establishing a medical center and a teaching unit, both located in the Hospital Güemes.

His fervent desire to develop a research department was realized in 1978 after the donation to the Favaloro Foundation of an 8-story building, by the Society of Distributors of Newspapers and Magazines. It was immediately designated as the long-awaited research building. Dr. Favaloro essentially succeeded in establishing and personally financing a genuine research department in Argentina, and he fought to ensure that the department would operate solely along the lines deemed appropriate by the researchers themselves, free from extrinsic pressure. Dr. Favaloro had achieved the unimaginable. 3

As this department was developing, admiration for his work grew not only in Buenos Aires but throughout the world. He resisted every attempt to draft him for high political office, and instead worked to amass the funds necessary for the construction of the Institute of Cardiology and Cardiovascular Surgery (Fig. 11) on a site adjacent to the research building: the culmination of his dream. 6 The building was inaugurated on 2 June 1992 with the motto: “Advanced technology at the service of medical humanism,” and on 20 June, the 1st surgical intervention was carried out at the institute. This institute emulated the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in the United States.* Like the Cleveland Clinic, it was a nonprofit organization with no owner other than the community at large, to which it had been dedicated.

Fig. 11 A) The exterior of the Institute of Cardiology and Cardiovascular Surgery, founded by Dr. Favaloro in Buenos Aires. B) Main entrance to the Institute of Cardiology and Cardiovascular Surgery.

(Photos courtesy of the Favaloro Foundation.)

Approximately 25% of the patients operated upon at the Institute had no insurance or social protection but were provided the same level of medical assistance and the same facilities as their insured counterparts. “Our patients must always mean the same to us: poor or rich; Catholics, Protestants, or Jews; white, black, or yellow. They have a soul and a body and a social scenario.” 3

By 1999, no fewer than 400 cardiologists and cardiovascular surgeons had been trained at the Favaloro Foundation and were scattered all over Latin America and beyond, witnesses to the enormous bravery and generosity of this 1 man. 2

Despite his demanding surgical schedule in Argentina, Favaloro's passion for research and publication showed no tendency to abate. 6 In order to analyze all the data related to coronary arteriosclerosis with accuracy, he helped develop a classification scheme for ischemic cardiomyopathy 42; and he continued experimental work on acute myocardial infarction, using monkeys from northern Argentina. 4

Together with his coworkers, he published important papers regarding the risk of recoarctation in neonates and infants, 43 the comparison of different levels of anticoagulant therapy in patients with substituted heart valves, 44 combined therapy using thrombolysis and coronary reoperation for acute postoperative myocardial infarction, 45 and countless others. 46–51

Among René's broad interests, Latin American history was forever in the forefront, which explains his admiration for San Mart'n, who won freedom for Argentina, Chile, and Peru. Dr. Favaloro wrote 2 books dedicated to San Martín: ¿Conoce Usted San Mart'n? 52 (1987) and La Memoria Guayaquil 53 (1991). His Recuerdos de un Médico Rural 54 (1980) sheds some light on his years spent in Jacinto Aráuz and on the dismal realities that greeted him there, while his other book, De La Pampa a los Estados Unidos (1992), 55 is another eminently readable account of Dr. Favaloro's experiences, including the memorable years spent at the Cleveland Clinic. This book was later translated in-to English under the title The Challenging Dream of Heart Surgery 56 (1994). The preface to this edition was compiled by William L. Proudfit, who wrote the following, with reference to Dr. Favaloro: “One of his favorite books is Don Quixote and some have thought that he bears a resemblance to the principal character. This analogy is apt insofar as it applies to struggle towards the ideal. When we were preparing for anatomical dissection in medical school, our brilliant lecturer said, ‘Gentlemen, man is a soul, he has a body.’ Don Quixote would have endorsed that belief and Dr. René G. Favaloro has lived by it.”

Favaloro was regularly featured in the local media, where he voiced his social commentary on matters about which listeners might not have been particularly willing to hear. 6 He was deeply perturbed by the moral turmoil brewing in Argentina and in the world at large:

Without doubt, education in Argentina has been in decline, particularly over the last fifty years during which civilian and military governments have alternated …. The communications media, especially television, which uses images as an educative base, have flooded us with their promotion of material values giving us to understand that our existence is justified only through possession, power, and pleasure. This message has unfortunately invaded the souls of our young people. 5

He was an active member of the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (CONADEP), which was established after democracy was restored in Argentina in 1983. The commission was chartered to investigate the fates of thousands who had disappeared during the junta rule. The CONADEP chief executive resolved that the commission would comprise individuals who enjoyed national and international prestige and consistently defended human rights. It then came as no surprise when Dr. Raul Alfonsin, the new president of the democratic republic, called upon Dr. Favaloro to join CONADEP.

Despite his unorthodox Sicilian ways, Dr. Favaloro's popularity soared, and he never ceased to intrigue and mesmerize his students with his outstanding teaching skills.

Dr. Favaloro returned to the Cleveland Clinic several times after his departure; perhaps the most important of these trips was in 1985, when Mason Sones was dying of bronchogenic carcinoma. 7

René belonged to numerous honorary and scientific societies and received many highly coveted accolades and international awards. In 1992, he received the International Recognition Award at the annual meeting of the Denton A. Cooley Cardiovascular Surgical Society, held that year in Puerto Rico. 57

He spent his last few years living modestly in the area of Buenos Aires known as Palermo.

Curtain

In order to maintain itself, a great institution like the Favaloro Foundation required a budget equal in greatness. In the midst of a good economy this was of little concern; however, in the late 1990s, when Argentina's economic standing turned sour, the magnitude of the problem became all too clear. At the age of 77, René was faced with tremendous losses due to defaults in payments from other hospitals and the government, 6 estimated at around $18 million. In the last years of his life, at a time when he ought to have begun reaping the benefits of decades of relentless work, he was instead compelled to vie for additional financial help. He tried desperately to rectify the situation and salvage the Foundation, which had become his very soul. A week before his death, he wrote a letter to the President of Argentina, pleading for the payment of government debts to his institute, 6 but it was to no avail.

The struggle was over. On 29 July 2000, René, at the age of 77, died by his own hand, according to official reports.

News of Dr. Favaloro's death spread as a shock wave across Latin America, the United States, and farther still. The world's medical community was dumbfounded and could not come to terms with the loss.

Dr. Favaloro was an immensely warm, sensitive, loyal, and humble man who touched people's hearts (without the need for a sternotomy). There was something subtle about this Sicilian surgeon, who was fearless in the face of injustice, yet so easily moved to tears by human suffering. 3

René would be very sad for days after the death of one of his patients, and would scrutinize all the data until he reached a plausible explanation. He could recall those details several years later, and would never repeat mistakes. While some surgeons blamed the anesthetist, the perfusionist, the resident, the internist, the nurse, the laboratory, or even the patient himself (for having presented too late), Dr. Favaloro assumed his responsibility and strove to understand what could have gone wrong: “I believe that individuals and peoples unable to recognize their own defects are unable to correct them.” 5

René never failed to express his gratitude to the Cleveland Clinic Foundation for granting him his opportunity. He always minimized personal contributions and emphasized teamwork in patient care, 6 “for I have always believed in teamwork. ‘We’ is more important than ‘I’. In medicine, the advances are always the result of many efforts accumulated over the years.” 4 There is no doubt that the Cleveland Clinic Foundation today would be a very different institution, but for René. 6

Today, his treasured Institute in Argentina lives on, a timeless memento to its colossal founder. After the death of Dr. Favaloro, a new board of directors saved the Foundation through restructuring of management, layoffs, and fund-raising. Another crisis came with the Argentine economic default in December 2001, but that too passed. Today, the Foundation boasts highly specialized services in cardiology, cardiovascular surgery, pulmonology, nephrology, hepatology, and immunogenetics, and retains all those val-ues that Dr. Favaloro held so much at heart: vocation for service; innovation and creativity; a “transparent” communication culture of forthright exchange; social commitment; professional excellence and ethics; and above all, the respect for human life and dignity.

Dr. Favaloro was a dreamer, and in the face of injustice, poverty, and oppression that in most other people would have inspired despair or cynicism, he struggled to keep his dreams alive. As Joan Manuel Serrat said, “without Utopias, life is nothing but a long and sad dress-rehearsal for death.” 5

As a surgeon, René will be remembered for his ingenuity and imagination; but as a man, he will be remembered for his compassion and selflessness. 57

The fire of enthusiasm that fueled all his ambitions, both social and medical, will glow forever in the students he taught, the lives he saved, and all the friends he made along the way. René Gerónimo Favaloro bequeathed to humanity both surgical innovation and the paradoxical grandeur of his simple life, which sprang boldly from the dryness of the dusty pampas and was saturated, in the end, by the tears of thousands.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the following persons and institutions for their great support during the preparation of this project. William C. Sheldon, MD, kindly provided many personal notes and reprints pertaining to Dr. Favaloro and made several editorial suggestions that proved instrumental in the completion of the manuscript. Alex Manché, MPhil, FRCS (CTh), FETCS, St. Luke's Hospital Malta, provided innumerable editorial suggestions and access to original articles and other literature, which the author found extremely useful at all stages of her work. Frederick Lautzenheiser, Associate Archivist of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, provided invaluable help and great patience, and the Cleveland Clinic Foundation itself granted numerous permissions for re-publication. The Favaloro Foundation granted several permissions to reprint, made valuable editorial suggestions, and was kindly disposed to the author during the most crucial stages of the project. Roberto Lufschanowski, MD, FACC, of Leachman Cardiology Associates (Houston) drew the author's attention to fundamental aspects of Dr. Favaloro's life in Argentina after his departure from the Cleveland Clinic. Nicholas Portelli was most generous with his advice. Not least, the author would like to thank her dean, Professor G. Laferla, PhD, MD, FRCS, and the head of the department of pathology, Professor A. Cilia Vincenti, MD, FRCPath, both at the University of Malta Medical School, for their continual support.

Footnotes

*Dr. William C. Sheldon's biographical notes on Dr. Favaloro were made available to the author through the courtesy of Dr. Sheldon on 20 June 2003.

Address for reprints: Gabriella Captur, 41/3 Victory Flats, St. Paul's Street, Sliema SLM06, Malta

E-mail: captur@maltanet.net

References

- 1.Hernandez J. The gaucho Martin Fiero. Translation by Walter Owen. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Distribuidora Quevedo de Ediciones; 1997.

- 2.Favaloro R. A revival of Paul Dudley White: An overview of present medical practice and of our society. Circulation 1999;99:1525–37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Pichel RH. Dr. Rene G. Favaloro: a biographical note. Clin Cardiol 1992;15:58–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Favaloro RG. Landmarks in the development of coronary artery bypass surgery. Circulation 1998;98:466–78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Favaloro RG. Science, education and development. Cornerstone Laying Ceremony of the Gitter-Smolarz Building for the Library of Life Sciences and Medicine. Tel Aviv, Israel: Tel Aviv University; May 1995. Lecture.

- 6.Proudfit WL. In Memory of Rene G. Favaloro, M.D. Cleveland Clinic Alumni Connection Magazine 2000(3);10:4–5.

- 7.Westaby S, Bosher C. Landmarks in cardiac surgery. Oxford: Isis Medical Media Ltd.; 1997.

- 8.Sones FM Jr, Shirkey EK. Cine coronary arteriography. Mod Concepts Cardiovasc Dis 1962;31:735–8. [PubMed]

- 9.Effler DB, Groves LK, Sones FM Jr, Shirey EK. Endarterectomy in the treatment of coronary artery disease. J Tho-rac Cardiovasc Surg 1964;47:98–108. [PubMed]

- 10.Senning A. Strip grafting in coronary arteries. Report of a case. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1961;41:542–9. [PubMed]

- 11.Proudfit WL, Shirey EK, Sones FM Jr. Selective cine coro-nary arteriography. Correlation with clinical findings in 1,000 patients. Circulation 1966;33:901–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Fergusson DJ, Shirey EK, Sheldon WC, Effler DB, Sones FM Jr. Left internal mammary artery implant—postoperative assessment. Circulation 1968;37(4 Suppl):II24-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Sewell WH. Surgery for acquired coronary disease. Springfield (IL): Charles C. Thomas; 1967.

- 14.Favaloro RG. Bilateral internal mammary artery implants. Operative technic—a preliminary report. Cleve Clin Q 1967;34:61–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Favaloro RG. Double internal mammary artery implants: operative technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1968;55:457–65. [PubMed]

- 16.Favaloro RG, Effler DB, Groves LK, Fergusson DJ, Lozada JS. Double internal mammary artery-myocardial implantation. Clinical evaluation of results in 150 patients. Circulation 1968;37:549–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Favaloro RG, Effler DB, Groves LK, Sones FM Jr, Fergusson DJ. Myocardial revascularization by internal mammary artery implant procedures. Clinical experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1967;54:359–70. [PubMed]

- 18.Favaloro RG. Unilateral self-retaining retractor for use in internal mammary artery dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1967;53:864–5. [PubMed]

- 19.Effler DB, Sones FM Jr, Favaloro R, Groves LK. Coronary endarterectomy with patch-graft reconstruction: clinical experience with 34 cases. Ann Surg 1965;162:590–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Effler DB, Groves LK, Suarez EL, Favaloro RG. Direct coronary artery surgery with endarterotomy and patch-graft reconstruction. Clinical application and technical considerations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1967;53:93–101. [PubMed]

- 21.Favaloro RG. Surgical treatment of coronary arteriosclero-sis. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1970.

- 22.Effler DB, Favaloro RG, Groves LK. Coronary artery surgery utilizing saphenous vein graft techniques. Clinical experience with 224 operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1970;59:147–54. [PubMed]

- 23.Favaloro RG. Saphenous vein autograft replacement of severe segmental coronary artery occlusion: operative technique. Ann Thorac Surg 1968;5:334–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Johnson WD, Flemma RJ, Lepley D Jr, Ellison EH. Extended treatment of severe coronary artery disease: a total surgical approach. Ann Surg 1969;170:460–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Garrett HE, Dennis EW, DeBakey ME. Aortocoronary bypass with saphenous vein bypass. Seven-year follow-up. JAMA 1973;223:792–4. [PubMed]

- 26.Favaloro RG. Saphenous vein graft in the surgical treatment of coronary artery disease. Operative technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1969;58:178–85. [PubMed]

- 27.Sheldon WC, Sones FM Jr, Shirey EK, Fergusson DJ, Favaloro RG, Effler DB. Reconstructive coronary artery surgery: postoperative assessment. Circulation 1969;39(5 Suppl 1): I61-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Sheldon WC, Favaloro RG, Sones FM Jr, Effler DB. Reconstructive coronary artery surgery. JAMA 1970;213:78–82. [PubMed]

- 29.Favaloro RG, Effler DB, Groves LK, Razavi M, Lieberman Y. Combined simultaneous procedures in the surgical treatment of coronary artery disease. Ann Thorac Surg 1969;8:20–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Favaloro RG. Combined simultaneous procedures in the surgical treatment of coronary artery disease. In: Favaloro RG. Surgical treatment of coronary arteriosclerosis. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1970. p. 106-15.

- 31.Favaloro RG, Effler DB, Cheanvechai C, Quint RA, Sones FM Jr. Acute coronary insufficiency (impending myocardial infarction and myocardial infarction): surgical treatment by the saphenous vein graft technique. Am J Cardiol 1971; 28:598–607. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Favaloro RG. Impending infarction should be prevented by myocardial revascularization (surgical viewpoint). Cardiovasc Clin 1977;8:53–7. [PubMed]

- 33.Sarnoff SJ, Braunwald E, Welch GH Jr, Case RB, Stainsby WN, Macruz R. Hemodynamic determinants of oxygen consumption of the heart with special reference to the tension-time index. Am J Physiol 1958;192:148–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Braunwald E, Sarnoff SJ, Case RB, Stainsby WN, Welch GH Jr. Hemodynamic determinants of coronary flow; effect of changes in aortic pressure and cardiac output on the relationship between myocardial oxygen consumption and coronary flow. Am J Physiol 1958;192:157–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Sonnenblick EH, Ross J Jr, Covell JW, Kaiser GA, Braunwald E. Velocity of contraction as a determinant of myocardial oxygen consumption. Am J Physiol 1965;209:919–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Sonnenblick EH, Ross J Jr, Braunwald E. Oxygen consumption of the heart. Newer concepts of its multifactorial determination. Am J Cardiol 1968;22:328–36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Graham TP Jr, Covell JW, Sonnenblick EH, Ross J Jr, Braunwald E. Control of myocardial oxygen consumption: relative influence of contractile state and tension development. J Clin Invest 1968;47:375–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Cox JL, McLaughlin VW, Flowers NC, Horan LG. The ischaemic zone surrounding acute myocardial infarction. Its morphology as detected by dehydrogenase staining. Am Heart J 1968;76:650–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Favaloro RG, Effler DB, Groves LK, Sheldon WC, Sones FM Jr. Direct myocardial revascularization by saphenous vein graft. Present operative technique and indications. Ann Thorac Surg 1970;10:97–111. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Favaloro RG, Effler DB, Groves LK, Sheldon WC, Shirey EK, Sones FM Jr. Severe segmental obstruction of the left main coronary artery and its divisions. Surgical treatment by the saphenous vein graft technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1970;60:469–82. [PubMed]

- 41.Green GE, Stertzer SH, Reppert EH. Coronary arterial bypass grafts. Ann Thorac Surg 1968;5:443–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Favaloro RG. Computerized tabulation of cine coronary angiograms. Its implications for results of randomized trials. Circulation 1990;81:1992–2003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Dietl CA, Torres AR, Favaloro RG, Fessler CL, Grunkemeier GL. Risk of recoarctation in neonates and infants after repair with patch aortoplasty, subclavian flap, and the combined resection-flap procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1992;103:724–32. [PubMed]

- 44.Altman R, Rouvier J, Gurfinkel E, D'Ortencio O, Manzanel R, de La Fuente L, Favaloro R. Comparison of two levels of anticoagulant therapy in patients with substitute heart valves. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1991;101:427–31. [PubMed]

- 45.Rojo H, Cabrera E, Boullon F, de la Fuente L, Favaloro RG. Thrombolysis and coronary reoperation: successful combined therapy for acute postoperative myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 1985;109(3 Pt 1):586–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Weinschelbaum E, Stutzbach P, Machain A, Favaloro R, Caramutti V, Bertolotti A, Fraguas H. Valve operations through a minimally invasive approach. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;66:1106–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Favaloro RG. The developmental phase of modern coronary artery surgery. Am J Cardiol 1990;66:1496–503. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Dietl CA, Torres AR, Cazzaniga ME, Favaloro RG. Right atrial approach for surgical correction of tetralogy of Fallot. Ann Thorac Surg 1989;47:546–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Armentano R, Favaloro RG. Is the use of t-PA as compared with streptokinase cost effective? N Engl J Med 1995;333:1009–10. [PubMed]

- 50.Dietl CA, Cazzaniga ME, Dubner SJ, Perez-Balino NA, Torres AR, Favaloro RG. Life-threatening arrhythmias and RV dysfunction after surgical repair of tetralogy of Fallot. Comparison between transventricular and transatrial approaches. Circulation 1994;90(5 Pt 2):II7-12. [PubMed]

- 51.Favaloro RG. The developmental phase of modern coronary artery surgery. Am J Cardiol 1990;66:1496–503. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Favaloro RG. Conoce usted a San Martin? Buenos Aires: Torres Aguero; 1986.

- 53.Favaloro RG. La Memoria de Guayaquil. Buenos Aires: Torres Aguero; 1991.

- 54.Favaloro RG. Recuerdos de un medico rural. Buenos Aires: Torres Aguero; 1992.

- 55.Favaloro RG. De La Pampa a los Estados Unidos. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana; 1992.

- 56.Favaloro RG. The challenging dream of heart surgery. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1994.

- 57.Cooley DA. In Memoriam. Tribute to Rene Favaloro, pioneer of coronary bypass. Tex Heart Inst J 2000;27:231–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed]