Abstract

The experimental investigation of heart transplantation began almost 100 years ago, but it was not until the studies at Stanford Medical School in the late 1950s and early 1960s that clinical transplantation became a realistic possibility. Barnard performed the 1st human-to-human orthotopic heart transplantation in 1967, and followed this by introducing the technique of heterotopic heart transplantation in 1974. Reitz and colleagues at Stanford performed the 1st successful clinical transplantation of the heart and both lungs in 1981. Two years later, at the Toronto General Hospital, successful singlelung transplantation was performed, followed by bilateral lung transplantation in 1986. Aspects of the surgical techniques of these various experimental and clinical procedures are discussed.

Key words: Animal, cardiac surgical procedures/history, heart transplantation/methods, history of medicine/20th cent., human, lung transplantation/methods

By performing the 1st human-to-human heart transplant in Cape Town in 1967, Christiaan Barnard began a new era of the transplantation of thoracic organs. Lung transplantation became established in 1983 with the 1st truly successful operation performed in Toronto by Joel Cooper and his associates. Today, approximately 3,000 hearts and 1,500 lungs are transplanted annually worldwide. The experimental basis on which today's clinical transplantation programs are built, however, goes back almost 100 years.

Heart Transplantation

Experimental Background. The 1st reported attempts at experimental heterotopic heart transplantation (in dogs) were by Carrel and Guthrie in 1905, who transplanted the heart into the neck. 1 The crucial factor of donor coronary perfusion was simplified in 1933, when Mann and his colleagues developed a refined technique of cervical heart transplantation (Fig. 1). This technique has been the basis of numerous subsequent studies, particularly with regard to the response of the denervated heart to pharmacologic agents and physiologic stresses. 1 In 1946, Demikhov, working in the Soviet Union before supportive techniques such as hypothermia and cardiopulmonary bypass had been developed, began extensive studies on transplantation of the heart into the thorax. 1 These studies involved the addition of a 2nd heart (occasionally with an attached lobe of a lung) as an auxiliary pump, as well as orthotopic transplantation of the heart with and without both lungs. Few animals survived more than a few days; most of the early deaths were associated with technical problems.

Fig. 1 Experimental heterotopic heart transplantation in the neck. The donor coronary arteries are perfused with oxygenated blood from the recipient's carotid artery. Coronary venous return is ejected through the donor pulmonary artery into the internal jugular vein of the recipient. (The donor heart can be placed in the abdomen with anastomoses to the recipient aorta and inferior vena cava.)

AO = aorta; CCA = common carotid artery; IJV = internal jugular vein; LA = left atrium; LV = left ventricle; PA = pulmonary artery; RA = right atrium; RV = right ventricle

(From: Cooper DKC, et al., 2 © 1996. Reproduced with kind permission of Kluwer Academic Publishers.)

Orthotopic Heart Transplantation

Demikhov made the 1st recorded attempt at orthotopic heart transplantation in 1951, 1 but it was not until 1955 that he achieved good cardiac function in 2 dogs for periods of just over 11 and 15 hours, respectively. With the arrival of methods for supporting the recipient during the operative procedure, workers in this field became more ambitious. In 1959, Cass and Brock of Guy's Hospital in London reported 6 attempts at autotransplantation and allotransplantation using a technique in which both atria were left intact in the recipient, and anastomoses of the atria, aorta, and pulmonary artery were all that were required. 1,3 This procedure was described independently 1 year later by Shumway and his colleagues, who achieved the 1st consistently successful results at Stanford Medical School. 1 In their dogs, normal cardiac output was demonstrated 1 year after allotransplantation and 5 years after autotransplantation.

In autotransplantation, excision of the donor heart requires an incision in the right atrium that extends above the sinoatrial node into the superior vena cava (SVC). The Cape Town group used this procedure to assess the efficacy of a system for hypothermic perfusion storage of baboon hearts. 4 The heart was excised and stored, and the baboon was kept alive by an allotransplant. The allotransplant, in turn, was excised 24 or 48 hours later, when the stored native heart was reimplanted. Without the risk of rejection, cardiac function was studied for more than 2 years. In 1981, this storage system was used successfully for clinical allotransplantation at Groote Schuur Hospital after donor heart storage for periods of 7 to 13 hours. 4

Clinical Experience. After his 1st clinical case in 1967, 5 Barnard made an important modification by incising the donor right atrial cavity from the orifice of the inferior vena cava (IVC) into the base of the right atrial appendage rather than into the SVC, thus avoiding the area of the sinoatrial node (Fig. 2A). With this modification, this technique has formed the basis of clinical orthotopic heart transplantation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Orthotopic heart transplantation. A) The recipient ventricles with all 4 valves have been excised. Note the incision in the donor right atrium extending into the atrial appendage to avoid the sinoatrial node. The 1st suture line between the donor and recipient hearts (between the free walls of the left atria) has been started. This will be followed by anastomoses of the 2 atrial septa, the free walls of the right atria, the aortae, and pulmonary arteries, not necessarily in that order. B) The completed operation.

IVC = inferior vena cava; SVC = superior vena cava; other abbreviations as for Fig. 1

(From: Cooper DKC, et al., 2 © 1996. Reproduced with kind permission of Kluwer Academic Publishers.)

More recently, at some centers, a bicaval anastomosis has been performed, with end-to-end anastomoses of both the SVC and the IVC; this is becoming the operation of choice of most surgeons. This is, in fact, a return to an earlier experimental technique. 1 The bicaval anastomoses allow maintenance of the integrity of atrial conducting pathways, improving the likelihood of achieving sinus rhythm, which is important for good early hemodynamics. This method also entails a lower incidence and severity of tricuspid regurgitation.

In 1991, the “total” orthotopic heart transplantation technique was first reported. 6 This involves not only bicaval anastomoses but also separate anastomoses of the paired right and left recipient pulmonary veins to the posterior wall of the donor left atrium (Fig. 3). Some have modified this approach by using a single cuff of recipient left atrium, incorporating all 4 pulmonary veins. Although early or late hemodynamic superiority of these techniques has not yet been demonstrated conclusively, there appear to be several advantages, including a reduced risk of atrial thrombus formation.

Fig. 3 “Total” orthotopic heart transplantation. A) Posterior aspect of the donor heart: the superior and inferior venae cavae have been retained with the right atrium; the posterior wall of the left atrium is intact except for the orifices of the paired pulmonary veins. B) The recipient pericardial cavity after excision of the native ventricles: the atria will be excised, and the only remaining structures will be the 2 venae cavae and the 2 left atrial cuffs around the pulmonary vein orifices (indicated by dotted lines).

(From: Cooper DKC, et al., 2 © 1996. Reproduced with kind permission of Kluwer Academic Publishers.)

Modifications in Children. Modifications of the standard procedure of orthotopic heart transplantation are required in infants and children with certain congenital anomalies. 7 For example, in a patient with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, the donor heart is excised in continuity with the ascending aorta and arch (and even part of the descending aorta) to be used in aortic reconstruction in the recipient. The donor aortic flap is anastomosed to the recipient aorta to re-create aortic continuity. Various other modifications are required in the presence of 1) a left SVC, 2) bilateral SVCs, 3) a previous Fontan procedure, 4) situs inversus, or 5) heterotaxic syndromes (splenic syndromes, which involve ambiguous visceral and atrial situs associated with anomalies of systemic and pulmonary venous drainage). 7

Heterotopic Heart Transplantation

The introduction of heterotopic heart transplantation by Barnard and Losman in 1974 provided another surgical transplantation technique, with some advantages and some disadvantages over orthotopic heart transplantation. 8

Surgical Techniques. The initial surgical technique was one of left heart bypass alone, which involved anastomoses between the donor and recipient left atria and aortae (Fig. 4A). The donor coronary sinus venous return was drained through the donor right atrium and right ventricle into the recipient's circulation by anastomosis of the donor pulmonary artery to the recipient right atrium. The only 2 patients in whom this procedure was performed experienced recurrent native heart dysrhythmias, including ventricular fibrillation, during which time the donor heart supported the circulation alone, although with substantial loss of blood pressure.

Fig. 4 Heterotopic heart transplantation. A) The completed operation of left heart support with a heterotopic heart transplant: the respective donor and recipient atria are anastomosed, followed by an end-to-side aortic anastomosis; the coronary venous drainage of the donor heart is drained through the donor pulmonary artery into the recipient right atrium. B) The completed operation of biventricular support: the anastomoses are as above, except that the right ventricular output is directed through the donor pulmonary artery into the recipient pulmonary artery, usually through a synthetic conduit. C) Replacement of the native heart in a patient with a previous heterotopic heart transplant: the shaded areas represent all that remains of the patient's native tissues.

D1 = initial heterotopic donor heart; D2 = subsequent orthotopic donor heart; other abbreviations as for Figs. 1 and 2.

(From: Cooper DKC, et al., 2 © 1996. Reproduced with kind permission of Kluwer Academic Publishers.)

As a result of this experience, the technique was modified to provide support to both recipient ventricles 9 (Fig. 4B). The modified operation requires anastomoses of both left and right atria, with direct end-to-side anastomosis of the donor aorta to the recipient aorta and end-to-side anastomosis of the donor pulmonary artery to the recipient pulmonary artery. The latter anastomosis usually requires an interposition conduit of a synthetic vascular graft.

Retransplantation after Heterotopic Heart Transplantation. Retransplantation after orthotopic heart transplantation is a relatively straightforward procedure; however, when a heterotopic donor heart fails, retransplantation can be difficult. In a report of our experience in Cape Town, 3 different 2nd transplant procedures were evaluated. 10 The 1st approach was replacement of the heterotopic donor heart, which could result in excessive bleeding, since the heart was adherent to the right lung. The 2nd approach involved replacement of the native heart, leaving the heterotopic donor heart in situ; in this approach, the standard operation of orthotopic heart transplantation was performed. In the 3rd approach, both the original donor heart and the native heart were excised, followed by orthotopic heart transplantation. After this procedure, the right lower lobe required mobilization and reexpansion to fill the space vacated by the excised heterotopic heart. The 2nd technique proved the procedure of choice (Fig. 4C). Because the 1st donor heart remained in situ, operating time was reduced, and potential postoperative complications were avoided. Repeat orthotopic heart transplantation was also the operation of choice at 3rd procedures when these were necessary.

Worldwide, heart transplantation—predominantly orthotopic heart transplantation—is currently associated with the following patient survival rates: 80% at 1 year, 65% at 5 years, and 50% at 10 years. 11

Transplantation of the Heart and Both Lungs

Experimental Background. In 1946, Demikhov transplanted the heart and lungs of a dog (without the use of cardiopulmonary bypass); however, it was not until 1949 that he achieved survival of more than a few hours. 12 His ingenious technique involved the excision of the donor (beating) heart and lungs, which became an autoperfusing heart–lung block. During transfer, this block was kept viable by its own closed-circuit circulation. 12,13 Blood from the left ventricle was pumped into the aorta, whence it passed through the coronary vessels, supplying the myocardium; returning through the coronary sinus into the right atrium, the right ventricle, and the lungs, oxygenated blood was returned to the left atrium. This form of autoperfusing heart–lung preparation subsequently became the basis for transporting and temporarily preserving the organs in clinical heart–lung transplantation. Of Demikhov's 67 attempts at heart–lung transplantation, only 6 dogs survived more than 48 hours, with a maximum survival of 6 days. Importantly, however, many of these dogs breathed spontaneously despite total denervation.

With the introduction of cardiopulmonary bypass, the heart–lung transplantation clearly became more feasible and was investigated by several groups, although the results remained extremely poor. In the late 1960s at the National Heart Hospital in London, Longmore and his colleagues simplified the operation by anastomosing the 2 right atria rather than the SVC and the IVC. 14 Only 3 anastomoses were now required: tracheae, right atria, and aortae (Fig. 5). This is the technique that has subsequently been used in clinical practice. It was not until the introduction of cyclosporine, however, that Reitz's group at Stanford, in their work with rhesus and cynomolgus monkeys, achieved long-term survival. 15

Fig. 5 Transplantation of the heart and both lungs. A) The recipient thorax after excision of the native heart and lungs: the trachea will be divided just above the carina. B) The donor right lung is passed posterior to the remnant of the recipient's right atrium and right phrenic nerve. The donor left lung is passed posterior to the left phrenic nerve. C) The donor right and left lungs have been placed in the respective pleural cavities. The tracheal anastomosis has been completed; the areolar tissue around the donor left atrium can be used to cover the tracheal suture line. The right atrial anastomosis is in progress. Anastomosis of the 2 aortae will complete the operation.

AO = aorta; LV = left ventricle; PA = pulmonary artery; RA = right atrium; RV = right ventricle

(Figs. 5B and 5C are from: Cooper DKC, et al., 2 © 1996. Reproduced with kind permission of Kluwer Academic Publishers.)

Clinical Experience. Heart–lung transplantation was first performed clinically by Cooley in 1968. 16 With the benefit of cyclosporine-based immunosuppressive therapy, Reitz and his colleagues were able to achieve long-term survival in 1981. 17

Surgical Technique. In the excision of the donor organs, unnecessary dissection of the trachea should be avoided in order to limit damage to the peritracheal tissue, which contains a tracheobronchial blood supply from coronary collateral vessels (Fig. 6). After division of the venae cavae, the aorta, and the trachea, the heart–lung block can be detached from its posterior mediastinal attachments.

Fig. 6 Posterior view of heart, bronchi, and trachea, indicating the collateral blood supply to the bronchi and trachea from coronary arteries.

LV = left ventricle

(From: Cooper DKC, et al., 2 © 1996. Reproduced with kind permission of Kluwer Academic Publishers.)

Excision of the native heart and lungs initially involves transection of the aorta, the 2 atria, and the pulmonary artery. Bilateral incisions are made in the pericardium posterior to the phrenic nerves (to permit passage of the donor lungs into the pleural spaces), with care being taken to avoid injury to the left recurrent laryngeal nerve and the phrenic nerves. Excision of the native lungs follows. The posterior left atrium is removed, and a passage is created posterior to the right atrium to allow the right donor lung to enter the right pleural space (Fig. 5A). The atrial septum effectively becomes the outside wall of the right atrium. The recipient trachea is then mobilized between the aorta and the SVC. Remnants of the left pulmonary artery are left in place (Fig. 5A) to avoid injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve. The trachea is divided above the level of the carina.

The donor heart–lung block is placed in the recipient chest. With the heart in the pericardial cavity, the right lung is passed behind the recipient right atrium and right phrenic nerve into the right pleural cavity (Fig. 5B), and the left lung is passed behind the left phrenic nerve into the left pleural cavity. Implantation involves anastomoses between the donor and recipient tracheae, aortae, and right atria (Fig. 5C).

The Domino Operation

The domino procedure was first performed in 1989 at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in the United States and at Harefield Hospital in the United Kingdom. In this procedure, the native heart of a patient undergoing heart–lung transplantation is transplanted into a patient who requires only heart transplantation. Most patients selected have primary pulmonary disease and secondary right ventricular hypertrophy. These patients receive a heart–lung block and donate their native heart to a patient who requires heart transplantation alone. The overall use of heart–lung blocks has decreased markedly in recent years (to approximately 100 per year worldwide), with a corresponding increase in the number of single and sequential single (bilateral) lung transplants. As a result, the domino operation has become rare.

Current survival rates after heart–lung transplantation are reported to be approximately 60% at 1 year, 40% at 5 years, and 25% at 10 years. 18

Lung Transplantation

Experimental Background. Experimental lung transplantation was first investigated by Demikhov in the 1940s. 1,12 Despite efforts by several groups, its success was limited—frequently by failure of the bronchial anastomosis, in part due to the need for large doses of corticosteroids to prevent rejection. As with heart– lung transplantation, it was the introduction of cyclosporine that enabled lung transplantation to be performed successfully.

Clinical Experience. The 1st clinical lung transplantation was attempted by Hardy and his group at the University of Mississippi in 1963. 19 The patient survived for 18 days but died of renal failure and infection. Long-term survival was not achieved until 1983, when the University of Toronto group initiated their clinical program. 20

Surgical Technique. When the lungs are to be retrieved from a donor, the heart is usually extracted first. When excising the heart, it is important to leave a sufficient left atrial cuff surrounding the pulmonary veins on each side to facilitate the eventual implantation of the lungs. For removal of the lung block, the pre-esophageal plane is dissected superiorly, at least to the level of the carina. The trachea is clamped and stapled with the lungs inflated. After the trachea has been divided, it is retracted forward, and dissection in the posterior mediastinum is completed.

Cardiopulmonary bypass is mandatory for lung transplantation in patients with primary or severe secondary pulmonary hypertension, but is no longer used routinely during single or sequential single-lung transplantation (although it should be available).

Single-Lung Transplantation

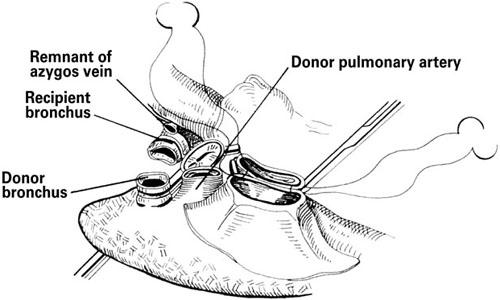

For single-lung transplantation, a generous posterolateral thoracotomy through the 5th interspace is performed. After native pneumonectomy, anastomoses are required between the donor and recipient bronchi, pulmonary artery, and pulmonary veins (using left atrial cuffs) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 Single-lung transplantation. Insertion of the donor lung requires anastomoses between the donor and recipient bronchi, pulmonary arteries, and left atrial cuffs.

(From: Cooper DKC, et al., 2 © 1996. Reproduced with kind permission of Kluwer Academic Publishers.)

Bilateral Single-Lung Transplantation

The initial clinical approach to double-lung transplantation involved procurement of a double-lung block, with anastomoses of the tracheae, left atria, and pulmonary arteries in the recipient. 21 This procedure, which involved division of many of the vessels supplying the distal trachea and proximal bronchi (Fig. 6), was associated with an unacceptable incidence of tracheobronchial ischemic necrosis. These hazards led to the abandonment of this approach and replacement with a bilateral, sequential, single-lung technique. For this operation, the patient is placed in a supine position, and a bilateral anterior thoracosternotomy is performed, usually in the 4th or 5th intercostal space. The lungs are implanted sequentially.

Lobar Transplantation

Lung transplantation in the pediatric population, or in patients of small size, is particularly limited by the scarcity of available organs. Circumvention of these obstacles has been made possible by the partition of 1 donor lung into its constituent lobes, which has allowed bilateral transplantation into a recipient of a smaller thoracic size. 22 Such is the shortage of donor lungs that living donor lobar transplantation has also been performed in some centers and was first reported in 1994. 23 Two living donors are used for each recipient, with each donating a right or left lower lobe. This procedure has the advantages of 1) immediate availability of donor organs, 2) assurance of the health of the donor lobes through extensive preoperative evaluation, and 3) control of the timing of the operation. The disadvantages are 1) a slight but real risk of morbidity and potential mortality to the donors and 2) the increased technical difficulty of lobar transplantation.

Current survival rates after single and bilateral lung transplantation are in the range of 70% at 1 year, 45% at 5 years, and 25% at 10 years. 18

The Future

The increasing shortage of donor thoracic organs will never be solved entirely by increased cadaveric donation. This problem has stimulated considerable research into alternatives that are as disparate as the use of ventricular assist devices and artificial hearts, cardiomyoplasty procedures, xenotransplantation, tissue engineering, the implantation of cultured cardiomyocytes, gene therapy, and stem cell therapy. Work is also progressing on the development of an artificial lung.

In xenotransplantation (my particular field of interest), there have been several clinical attempts to use animals as heart donors. 24 Indeed, the 1st heart transplant in a human being, performed in 1964 by Hardy and colleagues, 25 involved the implantation of a chimpanzee heart. The heart failed rapidly, largely due to inadequate size but also possibly to antibody-mediated rejection. 25 There have been no attempts at clinical lung xenotransplantation to date.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: D.K.C. Cooper, MD, PhD, FRCS, UPMC/MUH, Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute, Room N761, 3459 Fifth Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15213

E-mail: cooperdk@upmc.edu

This paper has its basis in an Arnott Lecture of the Royal College of Surgeons of England presented to the Section of Cardiothoracic Surgery of the Royal Society of Medicine in 2002.

References

- 1.Cooper DKC. Experimental development of cardiac transplantation. Br Med J 1968;4:174–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Cooper DKC, Miller LW, Patterson GA. The transplantation and replacement of thoracic organs. The present status of biological and mechanical replacement of the heart and lungs. 2nd ed. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996.

- 3.Cass MH, Brock R. Heart excision and replacement. Guys Hosp Rep 1959;108:285–90. [PubMed]

- 4.Cooper DKC, Wicomb WN, Barnard CN. Storage of the donor heart by a portable hypothermic perfusion system: experimental development and clinical experience. Heart Transplant 1983;2:104–10.

- 5.Barnard CN. The operation. A human cardiac transplant: an interim report of a successful operation performed at Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town. S Afr Med J 1967;41:1271–4. [PubMed]

- 6.Dreyfus G, Jebara V, Mihaileanu S, Carpentier AF. Total orthotopic heart transplantation: an alternative to the standard technique. Ann Thorac Surg 1991;52:1181–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Huddleston CB. Heart transplantation in infants and children—indications, surgical techniques and special considerations. In: Cooper DKC, Miller LW, Patterson GA. The transplantation and replacement of thoracic organs. The present status of biological and mechanical replacement of the heart and lungs. 2nd ed. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996. p. 367-77.

- 8.Barnard CN, Losman JG. Left ventricular bypass. S Afr Med J 1975;49:303–12. [PubMed]

- 9.Novitzky D, Cooper DKC, Barnard CN. The surgical technique of heterotopic heart transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg 1983;36:476–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Novitzky D, Cooper DKC, Brink JG, Reichart BA. Sequential—second and third—transplants in patients with heterotopic heart allografts. Clin Transplant 1987;1:57–62.

- 11.Taylor DO, Edwards LB, Mohacsi PJ, Boucek MM, Trulock EP, Keck BM, Hertz MI. The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twentieth official adult heart transplant report—2003. J Heart Lung Transplant 2003;22(6):616–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Cooper DKC. Transplantation of the heart and both lungs. I. Historical review. Thorax 1969;24:383–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Cooper DKC. A simple method of resuscitation and short-term preservation of the canine cadaver heart. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1975;70:896–908. [PubMed]

- 14.Longmore DB, Cooper DKC, Hall RW, Sekabunga J, Welch W. Transplantation of the heart and both lungs. II. Experimental cardiopulmonary transplantation. Thorax 1969;24:391–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Reitz BA, Burton NA, Jamieson SW, Bieber CP, Pennock JL, Stinson EB, Shumway NE. Heart and lung transplantation: autotransplantation and allotransplantation in primates with extended survival. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1980; 80:360–72. [PubMed]

- 16.Cooley DA, Bloodwell RD, Hallman GL, Nora JJ, Harrison GM, Leachman RD. Organ transplantation for advanced cardiopulmonary disease. Ann Thorac Surg 1969;8:30–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Reitz BA, Wallwork JL, Hunt SA, Pennock JL, Billingham ME, Oyer PE, et al. Heart-lung transplantation: successful therapy for patients with pulmonary vascular disease. N Engl J Med 1982;306:557–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Trulock EP, Edwards LB, Taylor DO, Boucek MM, Mohacsi PJ, Keck BM, Hertz MI. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Twentieth Official adult lung and heart-lung transplant report—2003. J Heart Lung Transplant 2003;22(6):625–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Hardy JD, Webb WR, Dalton ML Jr, Walker GR Jr. Lung homotransplantation in man: report of the initial case. JAMA 1963;186:1065–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Cooper JD. Lung transplantation: a new era [editorial]. Ann Thorac Surg 1987;44:447–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Dark JH, Patterson GA, Al-Jilaihawi AN, Hsu H, Egan T, Cooper JD. Experimental en bloc double-lung transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg 1986;42:394–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Couetil JP, Tolan MJ, Loulmet DF, Guinvarch A, Chevalier PG, Achkar A, et al. Pulmonary bipartitioning and lobar transplantation: a new approach to donor organ shortage. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1997;113:529–37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Starnes VA, Barr ML, Cohen RG. Lobar transplantation. Indications, technique, and outcome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1994;108:403–11. [PubMed]

- 24.Taniguchi S, Cooper DKC. Clinical xenotransplantation: past, present and future. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1997;79:13–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Hardy JD, Kurrus FD, Chavez CM, Neely WA, Eraslan S, Turner MD, et al. Heart transplantation in man. Developmental studies and report of a case. JAMA 1964;188:1132–40. [PubMed]