Abstract

Witnessed violence has significant negative consequences for youth behavior and mental health. However, many findings on the impact of witnessed violence have been based on a single informant. There is a general lack of consistency between caregiver and youth reports on both witnessed violence and behavioral problems. This study included data from both caregivers and youth and incorporated a multi-source analytic approach to simultaneously examine the association between youth witnessed violence and externalizing and internalizing behavior problems. Data from 875 caregivers and 812 youth were collected as part of the Longitudinal Studies of Child Abuse and Neglect (LONGSCAN). Findings showed that youth reported more witnessed violence than did their caregivers, and caregivers reported more externalizing and internalizing behavior problems than did youth. Further, the source of information had a significant impact on the association between witnessed violence and internalizing behaviors. These findings highlight the need to incorporate multiple sources and multi-informant analytic techniques to eliminate methodological limitations to understanding the effect of witnessed violence on youth behavioral problems.

Keywords: children, parents, family violence, community violence, child witnesses, LONGSCAN, inter-rater reliability

Introduction

Witnessed violence has a significant impact on youth mental health and on the likelihood of engaging in aggressive and antisocial behavior. This exposure may be to violence in the community or in the home, with many youth exposed to both. Findings from a large national survey revealed that nearly 40% of adolescents have witnessed community violence (Zinzow et al., 2009). This is consistent with other national surveys finding that nearly 1 in 4 children and youth had witnessed the victimization of another person (Finkelhor, Turner, Ormrod, & Hamby, 2009). Estimates tend to be higher for those living in urban or impoverished areas, with one study reporting that nearly 96% of 6–10 year old urban boys had witnessed at least one violent act, and 75% had witnessed four or more violent acts in their lifetime (Miller, Wasserman, Neugebauer, Gorman-Smith, & Kamboukos, 1999). Estimates of exposure to intimate partner violence are also high, with annual rates reported as high as 29% (McDonald, Jouriles, Ramisetty-Mikler, Caetano, & Green, 2006).

Witnessed violence is associated with behavioral problems, including both internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Buckner, Beardslee, & Bassuk, 2004; Evans, Davies, & DiLillo, 2008) and trauma-related symptoms (Johnson et al., 2002). It has also been associated with specific behavioral, emotional, and academic problems including: aggressive behavior (Guerra, Huesmann, & Spindler, 2003; Johnson et al., 2002), delinquent behavior (Hurt, Malmud, Brodsky, & Giannetta, 2001; Patchin, Huebner, McCluskey, Varano, & Bynum, 2006), depression (Johnson et al., 2002), suicidal ideation (Thompson et al., 2005), health risk behaviors (Bair-Merritt, Blackstone, & Feudtner, 2006; Felitti et al., 1998), and poor school outcomes (Hurt et al., 2001).

Violence exposure tends to be higher for at-risk populations, most notably victims of child maltreatment. Finkelhor et al. (2005) reported that 66% of children who reported experiencing some form of maltreatment also reported witnessing violence directly or indirectly (e.g., hearing gunshots). Estimates of the co-occurrence of child maltreatment and intimate partner violence have been consistently reported between 30% and 60% (Appel & Holden, 1998; Edleson, 1999; O’Leary, Slep & O’Leary, 2000) and appear to explain some of the link between intimate partner violence and child outcomes (Fergusson & Horwood, 1998; Mahoney, Donnelly, Boxer, & Lewis, 2003).

Other related factors that may influence the link between witnessed violence and child outcomes include child gender, ethnicity, and caregiver depressive symptoms. For example, boys tend to have higher rates of witnessed violence than do girls (Hanson et al., 2006); and, at least for some forms of violence exposure and externalizing outcomes, the effects appear stronger for boys than girls (Evans et al., 2008; Maschi, 2006). Also child ethnicity predicts exposure to witnessed violence with Caucasian and Asian youth reporting lower rates than other ethnic groups (Hanson et al., 2006). Finally, caregiver depressive symptoms have been associated with caregiver reports of child behavioral problems (Berg-Nielsen, Vika, & Dahl, 2003; De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005), possibly as a result of the direct influence of caregiver depression on children’s problem behavior, as well as the tendency for depressed caregivers to notice, report, perceive, and/or look for problem behavior in their children (Downey & Coyne, 1990).

Much of the research linking witnessed violence and problem behavior has been based on a single source of information – either the caregiver or the child/youth. Often studies, particularly those assessing witnessed violence in children, use parents as the sole source of information concerning children’s experiences of violence. There may be practical reasons for doing so in very young children. However, parents, particularly those of older children or adolescents, often substantially underestimate or under-report the amount of violence their children witnessed in both community (Ceballo, Dahl, Aretakis, & Ramirez, 2001; Hill & Jones, 1997) and domestic settings (Litrownik, Newton, Hunter, English, & Everson, 2003; Mahoney et al., 2003). Parents and children also frequently have disparate perspectives on children’s behavioral symptoms (e.g., Bird, Gould, & Staghezza, 1992; Ceballo et al., 2001; Starr, Dubowitz, Harrington, & Feigelman, 1999). Relative to child reports, parents tend to report more externalizing symptoms and fewer internalizing symptoms (Ferdinand, van der Ende, & Verhulst, 2006).

In addition to the lack of consistency among reporters, relying on a single informant about exposure to witnessed violence and the outcomes related to witnessing violence has additional limitations. First, because such an approach is prone to single-source bias, findings are likely capitalizing on shared method variance. Alternatively, not assessing youth’s reports of exposures and outcomes may under-represent the clinically important experience of and impact on the youth. In cases where data from multiple informants are collected, most employ one of four methods: choosing a single informant, analyzing the data for each informant separately, using the maximum report method, whereby a specific predictor or outcome is counted as occurring if either of the informants indicates its presence, or averaging responses from informants. All of these approaches share limitations; simplistic attempts to combine by averaging or using a maximum report rule may artificially inflate actual rates of the predictor or outcome, and integrating the results of separate data analyses may make interpretation and generalizability difficult (Kuo, Mohler, Raudenbush, & Earls, 2000; Rubio-Stipec, Fitzmaurice, Murphy, & Walker, 2003).

Ideally, data from multiple sources would offer the breadth and perspective to provide the closest truth of the measureable relationship between witnessed violence and outcomes. Fitzmaurice and colleagues developed a method utilizing multivariate regression models to include two informants in the same analysis. The advantages of this method include the inclusion of data from either or both informants, ability to examine source by covariate interactions, and adjust for the correlated observations (Goldwasser & Fitzmaurice, 2001; Horton & Fitzmaurice, 2004). Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) is one method used to conduct a multi-informant analysis.

Using a GEE model for multiple-source data, the primary purpose of the current analyses is to examine the association of witnessed violence on internalizing and externalizing behaviors in a sample of pre-adolescent, at-risk youth. A secondary purpose is to assess how the source of information (youth or caregiver) influences the link between violence exposure and youth behaviors.

Methods

The present analysis uses data from the Longitudinal Studies of Child Abuse and Neglect (LONGSCAN), a prospective study of the antecedents and consequences of child maltreatment that includes five sites distributed across the United States and a Coordinating Center. All sites share common instruments and protocols for data collection, entry, and management. Site samples vary by maltreatment risk status at recruitment. Two sites include children who were at high risk for maltreatment; two sites include children who had been reported for maltreatment; and one site includes children identified as at risk as well as those reported for maltreatment. Detailed information regarding the samples is available in Runyan et al. (1998).

LONGSCAN has conducted face-to-face interviews with the study participants and their primary caregiver approximately every two years, corresponding to the age of the child, beginning when the children were approximately 4 years old. Data for the current study were collected when the participants were approximately 12 years old. The children and their primary caregivers participated in separate interviews using an audio computer assisted self-administered interview (A-CASI). A trained interviewer was present to facilitate the interviews and administer the few measures that were not self-administered. Data from both the child and caregiver are used for the current study.

Participants

The LONGSCAN baseline sample includes 1,354 child-caregiver dyads. At the age 12 interview, 956 caregivers and 895 youth completed the interview. Of those, 875 caregivers and 812 youth had complete data on all measures of interest. Forty-nine percent of youth were female; a slight majority was African American (55%), followed by white (27%), mixed race (11%), or those of other race/ethnicity (7%). Most caregivers were female (92%), unmarried (62%), and the biological mother (64%). The median household income was between $20,000 and $24,999. See Table 1 for sample demographics. The analysis sample and the LONGSCAN baseline sample did not differ with respect with to child gender or race/ethnicity. There were significant site differences in that the Midwestern site contributed proportionately fewer participants and the Northwest site contributed more participants to the analysis sample relative to their baseline representation.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic Characteristics of the Sample (N = 884*)

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Child Gender | ||

| Females | 438 | 49.5 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Minority | 649 | 73.4 |

| Study Site | ||

| Eastern | 179 | 20.2 |

| Midwestern | 131 | 14.8 |

| Southern | 171 | 19.3 |

| Southwestern | 215 | 24.3 |

| Northwestern | 188 | 21.3 |

| Income | ||

| <$5,000 – $9,999 | 128 | 15.2 |

| $10,000 – $19,999 | 226 | 26.8 |

| $20,000 – $29,999 | 165 | 19.5 |

| $30,000 – $39,999 | 114 | 13.5 |

| $40,000 – $49,999 | 90 | 10.7 |

| $≥ $50,000 | 121 | 14.3 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 336 | 38.1 |

| History of Child Maltreatment | 695 | 78.6 |

Note. Demographics are reported for each unique participant, such that when data from both informants are present in the analysis sample, the data are not counted twice for the purpose of this table.

Measures

Behavior problems

The outcome measures of interest were the Externalizing and Internalizing scores from the Youth Self-Report (Achenbach, 1991a), completed by the youth, and the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991b), completed by the caregiver. These are two of three measures in a multiaxial assessment approach to employ multiple-source data in the assessment of problem behaviors (Achenbach, 1991a). The author reports good psychometrics with regard to test-retest reliability, inter-rater agreement, and validity for each of the two measures (Achenbach, 1991a, b).

The CBCL and YSR include 118 and 102 problem items respectively. Respondents are asked to indicate the extent to which each item describes the youth now or in the last six months on a 3-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = very or often true). Analogous items from the two instruments are similarly worded depending on the respondent (e.g., YSR: ‘I disobey my parents’, CBCL: ‘Disobedient at home’). The Externalizing score is comprised of the sum of responses from non-duplicate items from the Aggression and Delinquency problem subscales. The Internalizing score is comprised of the sum of non-duplicate items from the Withdrawal, Somatic Complaints, and Anxious/Depressed problem scales. In the current study, T-scores were used for all analyses.

Witnessed violence: Youth Report

Influenced by other measures of witnessed violence (e.g., Richters & Martinez, 1990), the History of Witnessed Violence measure (LONGSCAN, 1998) assesses whether the child witnessed any of 8 items that increase in severity from witnessing an arrest to witnessing someone killed. Each positive endorsement of a witnessed event elicits follow-up questions that include how often the event was witnessed (ever and in the last year). Response options include never (0), 1 time (1) 2–3 times (2), and 4 or more times (3).

Witnessed violence: Caregiver report

Caregivers completed the Child’s Life Events (LONGSCAN, 1992), a project modification of the Life Event Records (Coddington, 1972). LONGSAN added six items assessing child/youth exposure to violence. The items were similar to the History of Witnessed Violence items with two modifications. First, the caregiver received one item not administered to the youth respondents (“heard long, loud arguments between family members”), and the youth respondent received one item not included on the caregiver version (“seen someone arrested”). There were minor word variations and/or combination of questions that differed between the two respondent versions. Second, the caregiver version referenced events witnessed “in the last year” compared to the child respondent version which referenced both “ever “and “in the last year.” For the current study, events witnessed in the last year were used for both respondents.

The mean frequency of events witnessed in the last year was calculated for both youth and caregiver reports of child witnessed violence. Possible range of values = 0–3. Due to the significant positive skew of the witnessed violence scores, the values were dichotomized such that having witnessed any event with any frequency in the last year was coded 1 and no witnessed event was coded 0. See Tables 2 and 3 for youth and caregiver item endorsements and total scores.

Table 2.

Youth Reports of Witnessed Violence Events in the Last Year

| Item | Mean # of times witnessed (SD) | % Endorsing item (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Seen someone arrested | .85 (1.04) | 48.6 (426) |

| Seen someone slapped, kicked, hit with something or beaten up | .71 (1.04) | 37.5 (328) |

| Seen someone pull a gun on another person | .14 (.48) | 9.0 (80) |

| Seen someone pull a knife or razor on anyone | .18 (.59) | 11.0 (96) |

| Seen someone get stabbed or cut with some type of weapon | .11 (.43) | 7.3 (64) |

| Seen someone get shot | .11 (.46) | 6.5 (57) |

| Seen someone killed by another person | .04 (.30) | 3.0 (26) |

| Seen someone sexually assaulted, molested, or raped | .03 (.26) | 2.4 (21) |

| Total Score | .28 (.40) | 62.0 (545) |

Note. Response options for number of times event was witnessed ranged from 0 (never) to 3 (4 or more times).

Table 3.

Caregiver Reports of Child Witnessed Violence Events in the Last Year

| Item | Mean # of times witnessed (SD) | % Endorsing item (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Heard long, loud arguments | .85 (1.22) | 35.2 (308) |

| Seen someone hit, kicked, hit or physically harmed in some way | .23 (.65) | 12.8 (112) |

| Seen someone physically threatened with a weapon | .05 (.34) | 3.0 (26) |

| Seen someone get shot or stabbed | .03 (.22) | 1.83 (16) |

| Seen someone killed or murdered | .01 (.13) | 0.91 (8) |

| Seen someone sexually abused assaulted, or raped | .01 (.14) | 0.68 (6) |

| Total Score | .20 (.31) | 40.9 (359) |

Note. Response options for number of times event was witnessed ranged from 0 (never) to 3 (4 or more times).

Informant

A variable to indicate the source of the data (i.e., youth or caregiver) was included to assess possible effects of the informant (i.e., source) on the link between witnessed violence and behavior problems. Caregivers were coded 0 and the youth were coded as 1. An observation was included for any caregiver and any youth who had complete data.

Control variables

Control variables included youth race/ethnicity, youth gender, history of child maltreatment, caregiver depression, and study site.

Demographics

Demographic information on youth race/ethnicity and gender was obtained from the baseline interview with the primary caregiver. Race was coded as minority (non-white) or non-minority (white). Family income, assessed in $5,000 increments up to $50,000, was obtained from the primary caregiver at the age 12 interview.

History of child maltreatment

History of child maltreatment was assessed via review of Child Protective Service (CPS) records and youth self-reports of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and psychological abuse. After examining the concordance between CPS reports and self-report, Everson and colleagues (Everson et al., 2008) suggested that the inclusion of both sources of information on abuse has the greatest measurement accuracy in part because CPS reports and youth retrospective self-reports of specific behaviors experienced by the youth are not parallel. In the current analyses, if the youth had been the subject of any CPS report for any maltreatment type from birth to age 12 or if the youth self-reported physical, sexual, or psychological abuse s/he was considered to have been maltreated. Each source for maltreatment history is described below.

CPS case narratives associated with both allegations and substantiations of maltreatment were abstracted and recoded according to a modified Barnett, Manly and Cicchetti (Barnett, Manly, & Cicchetti, 1993) coding system (English & LONGSCAN Investigators, 1997). Because studies have demonstrated that unsubstantiated referrals to CPS are as predictive of poor outcomes and/or re-referral as substantiated allegations (Hussey et al., 2005; Kohl, Jonson-Reid, & Drake, 2009), any allegation to CPS between birth and age 12 was coded as a history of child maltreatment. In addition to CPS records, three project-developed measures, Self-report of Physical Abuse, Self-report of Sexual Abuse, and Self-report of Psychological Abuse (Knight et al., 2008) were administered at the age 12 interview to assess possible lifetime experience of these types of abuse. Each instrument contains stem questions addressing specific abuse experiences. For the purposes of this study, 15 physical abuse items, 11 sexual abuse items, and 18 psychological abuse items were used to create dichotomous indicators for whether the youth reported physical, sexual, or psychological abuse in their lifetime.

Caregiver depression

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D: Radloff, 1977) was used to assess caregiver depression. The CES-D is a 20-item measure assessing how often respondents have experienced depressive symptoms in the last week. Ratings are made on 4-point Likert scale ranging from rarely or none (0) to most or all of the time (3). Items are summed to create a total score (range = 0–60). Higher scores indicate greater symptomology. For the current study, the total score was used in all analyses.

Analysis

Proc GENMOD in SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to conduct Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) to simultaneously analyze data from caregiver (n = 875) and youth reports (n = 812; analysis sample = 1687). The outcomes of interest were the Externalizing and Internalizing T-Scores from the CBCL and YSR. The primary predictor of interest was youth witnessed violence from caregiver and youth reports. Control variables included youth gender, youth minority status, study site, caregiver depression, and history of child maltreatment. Also of interest was the effect of the informant and whether the informant significantly affected the link between youth witnessed violence and youth internalizing and externalizing behaviors. This was assessed with the inclusion of an informant X witnessed violence interaction in each model.

Univariate analyses were conducted to determine if there were site differences in reported internalizing and externalizing behaviors. The Eastern and Midwestern sites were not significantly different from one another but differed from the Southern, Southwestern, and Northwestern sites. Because these latter sites did not significantly differ from each other, site was dichotomized into the Eastern and Midwestern sites (=0) and the Southwestern, Northwestern, and Southern sites (=1).

Results

The mean Externalizing and Internalizing T-Scores were 51.57 (11.53) and 49.95 (10.55) respectively across all informants (N = 1687). T-tests revealed that caregivers reported significantly higher scores on both Externalizing and Internalizing dimensions than did the youth (see Table 4). The mean witnessing violence score across all informants was 0.23 (SD = 0.35). Reports of youth witnessed violence differed significantly with youth self-reporting more than caregivers, both in terms of frequency and in having ever witnessed any violent event (see Table 4). For all subsequent analyses, a dichotomized measure of witnessed violence (any versus none) was used given the significant skew of the frequency of witnessed violence.

Table 4.

Comparing Youth and Caregiver Scores on Problem Behaviors and Witnessed Violence

| Overall Sample (n = 1687) | Youth (n = 812) | Caregiver (n = 875) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | t (df) | p | |

|

|

|||||

| Externalizing Behavior | 51.57 (11.53) | 47.85 (10.0) | 55.03 (11.4) | 13.49 (1685) | <.0001 |

| Internalizing Behavior | 49.95 (10.55) | 48.50 (9.74) | 51.30 (10.59) | 5.50 (1680) | <.0001 |

| Witnessed Violence | 0.23 (0.35) | 0.27 (0.36) | 0.20 (0.31) | −4.22 (1581) | <.0001 |

|

|

|||||

| % | % | % | χ2 | P | |

|

|

|||||

| Witnessed at Least One Violent Event | 50.74 | 61.4 | 40.8 | 71.87 | <.0001 |

Internalizing Behaviors

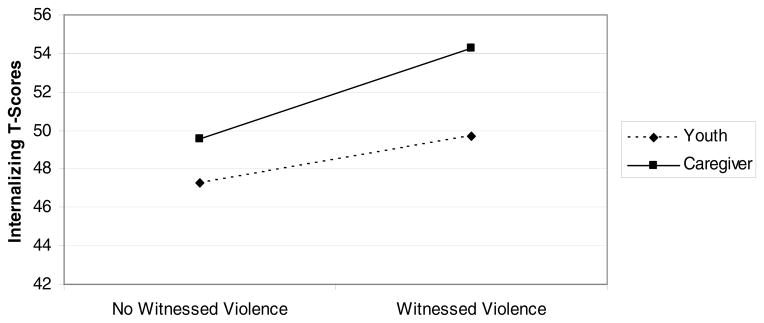

The GEE summary analyses are presented in Table 5. Significant main effects included site, minority status, maltreatment, caregiver depression, informant, and witnessed violence. The Midwest and Eastern sites had lower Internalizing scores compared to the Southern, Southwestern, and Northwestern sites. White youth, those with a history of child maltreatment, having witnessed violence, and youth whose caregivers had higher depression scores had higher internalizing problem behavior scores. Caregivers reported higher internalizing scores than did youth. In addition, there was a significant informant X witnessed violence interaction (z = −2.44, p < .05). A plot of the interaction showed that across informants, witnessed violence was associated with greater internalizing problems, and the increase was greater when caregivers reported the youth witnessed violence (see Figure 1).

Table 5.

Summary of GEE Analyses Predicting Internalizing Behaviors

| Variable | B | SE | Z | Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

|

|

|||||

| Site (0=Midwest and Eastern sites) | 1.57 | 0.62 | 2.55* | 0.36 | 2.78 |

| Gender (0=female) | 0.27 | 0.52 | 0.53 | −0.74 | 1.29 |

| Minority (0=White) | −1.90 | 0.65 | −2.95** | −3.17 | −0.64 |

| Maltreatment (0 = no) | 2.80 | 0.61 | 4.55*** | 1.59 | 4.00 |

| Caregiver depression | 0.20 | 0.02 | 8.12*** | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| Informant (0 = caregiver) | −2.25 | 0.68 | −3.30** | −3.59 | −0.92 |

| Any Witnessed Violence | 4.76 | 0.69 | 6.87*** | 3.40 | 6.11 |

| Informant X Witnessed Violence | −2.36 | 0.97 | −2.44* | −4.25 | −0.46 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Informant X Witnessed Violence Interaction for Internalizing Behaviors

Externalizing Behaviors

The GEE summary analyses are presented in Table 6. Significant main effects included site, maltreatment, caregiver depression, informant, and youth witnessed violence. The Midwest and Eastern sites had lower Externalizing scores compared to the Southern, Southwestern, and Northwestern sites. Caregivers reported higher Externalizing scores than did youth. A history of child maltreatment was associated with higher Externalizing scores as was higher caregiver depression scores and youth witnessed violence. The informant X witnessed violence interaction was not significant for externalizing behaviors.

Table 6.

Summary of GEE Analyses Predicting Externalizing Behaviors

| Variable | B | SE | Z | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

|

|

|||||

| Site (0= Midwest and Eastern sites) | 2.95 | 0.65 | 4.57*** | 1.68 | 4.22 |

| Gender (0=female) | −0.83 | 0.55 | −1.52 | −1.91 | 0.24 |

| Minority (0=white) | −0.55 | 0.68 | −0.81 | −1.89 | 0.78 |

| Maltreatment (0 = no) | 4.17 | 0.67 | 6.25*** | 2.86 | 5.47 |

| Caregiver depression | 0.16 | 0.03 | 5.68*** | 0.10 | 0.22 |

| Informant (0 = caregiver) | −7.09 | 0.70 | −10.19*** | −8.45 | −5.73 |

| Any Witnessed Violence | 4.77 | 0.72 | 6.66*** | 3.36 | 6.17 |

| Informant X Witnessed Violence | −1.66 | 1.00 | −1.65 | −3.63 | 0.31 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to apply a multi-informant analysis strategy to examine the association between youth exposure to violence and youth internalizing and externalizing behaviors, and to examine whether the informant contributed significantly to the understanding of this association. We were also able to examine how the informants differ in the reporting of witnessed violence and youth behavioral problems, as well as the overall association between violence exposure and behavioral symptoms. The overall findings showed that exposure to violence is associated with both internalizing and externalizing problems even after controlling for other potential risk factors, including direct victimization (i.e., child maltreatment). Youth reported more witnessed violence than did caregivers. Caregivers reported more frequent internalizing and externalizing behavior problems than did youth. Finally, there was a significant moderating effect of informant such that the association between witnessed violence and internalizing behaviors was greatest when the caregiver was the informant.

The proportion of youth in the current study who reportedly witnessed violence in the last year (41% and 61% based on caregiver and youth reports respectively) was higher than the 41% prevalence rate reported in a national sample of adolescents aged 12 – 17 (Zinzow, et al). This finding is not unexpected given that the youth in the current sample were at high risk for violence exposure and direct victimization. However, it is possible that the inclusion of two items, one for the youth and one for the caregiver, that may not involve direct witnessing of interpersonal violence (e.g., witnessing arrests, hearing long, loud arguments) could account for the higher rates as these two items were the most frequently endorsed by youth and caregiver informants. Nevertheless, 37% of youth reported seeing someone slapped, kicked, hit with something or beaten up, which indicates that witnessed violence in the current sample was at least comparable to what has been reported in a general survey sample.

Of note is the finding that youth reported having witnessed more violence than caregivers reported about the youth’s exposure. For example, 37% of the youth endorsed the above item (slapped, etc.), compared to only 13% of caregivers. Perhaps disagreement is more likely for less severe forms of violence and less likely for more severe exposure. This did not appear to be the case. The percentage of youth reporting more serious acts of violence ranged from 2% to 7% for items including seeing someone shot, stabbed, killed, or sexually assaulted compared to the considerably smaller percentage of caregivers who endorsed similar items (.7% to 2%). Other studies have demonstrated similar discrepancies among youth and caregivers, even when the events were particularly violent (Ceballo et al., 2001; Kuo et al., 2000).

There are several potential reasons for this discrepancy. First, it may be that caregivers are uncomfortable reporting the domestic violence their children have witnessed (DeVoe & Smith, 2003). Second, it may be difficult for parents to accurately assess how much violence children/youth have actually witnessed, particularly in chaotic or violent home environments (Appel & Holden, 1998; Litrownik et al., 2003). Third, as children age and engage in their environments in the company of peers rather than caregivers, children are likely to see and experience events that they may not report to caregivers. Finally, it is possible that the context of the violence exposure may be related to disagreement. For example, there may be greater agreement about intrafamilial violence exposure than violence witnessed outside the home. Any of these factors may contribute to discrepancies between youth and caregiver accounts of youth witnessed violence.

Caregivers and youth also disagreed on the extent of youth problem behaviors. The discrepancy between informants is not unexpected and is consistent with other literature showing that caregivers tend to report more externalizing behaviors than do youth (Ceballo et al., 2001; Starr et al, 1999). It is unclear whether this is because youth underestimate the impact that their externalizing behavior has on others, or because parents are particularly sensitive to such behavior. However, the finding that caregivers also reported more frequent internalizing behaviors was surprising and contradicts much of the literature on parent and youth reports of internalizing symptoms. Perhaps the context of the violence exposure is differentially related to internalizing versus externalizing problems. For example, internalizing problems may result from intrafamilial violence whereby externalizing problems may be associated, as both predictor and consequence, with extra-familial violence. Further work should focus on the characteristics of the specific high risk sample in the current study that could lead to under- or over-reporting of internalizing problems by youth and caregivers, respectively.

The finding that witnessed violence is associated with more frequent internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, both within and across informants, is consistent with many other studies (e.g., Buckner et al., 2004; Evans et al., 2008; Hurt et al., 2001; Zinzow et al., 2009). Both caregiver and youth self-reports of witnessed violence were associated with problem behaviors. However, when the caregiver was providing the information, the association between violence exposure and internalizing problems was more pronounced than when the youth provided the information. One possible explanation could be that caregivers who are aware of youth’s exposure to violence are also more sensitive, or overly sensitive, to youth behavioral problems that might result from such exposure.

The fact that informants differ, not only in their reports of the exposure and outcome variables but also in the magnitude of the association between violence exposure and behavioral symptoms, highlights the importance of obtaining multi-informant data rather than relying on one source and/or combining or averaging data across informants. Each of these methods is limiting and could obscure potentially important relationships among informants and how those differences may affect interpretation of findings. To the extent that multi-informant data are available, there are several analytic options, such as GEE analyses used here or Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM; See Kuo et al., 2000) to incorporate multiple sources of information and to examine, or control for, the role of informant.

To date studies have assessed informant differences in violence exposure (Kuo et al., 2000) and in investigations of informant differences in child symptomalogy (Rubio-Stipec et al., 2003), but none have incorporated the examination of multi-source data in the association between violence exposure and youth behavior. The current study bridges these lines of research to provide the first examination of violence exposure and youth behavior problems using a multi-informant approach. An important advantage is the elimination of single-source bias and shared method variance that often plagues other studies assessing the effect of witnessed violence. Our findings support other studies linking violence exposure and behavioral symptoms despite informant differences in the reporting of witnessed violence and behavioral problems. For both informants, witnessed violence is associated with more internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Yet, in examining the overall associations, the informant does affect the degree of association for internalizing problems.

Some limitations of this study are worth noting. First, the data on both the exposure and outcome were assessed simultaneously and thus limits any causal inferences. Second, there were some item differences between the witnessed violence assessment instruments. These differences may inflate the apparent discrepancy between the informants; however, there were significant differences between informants on the shared items as well. Finally, this study was conducted with participants who were maltreated or at-risk for maltreatment and their caregivers, who may or may not have been responsible for the maltreatment. Thus, generalizability to other populations may be limited. But, in combination with prior research, the current study contributes to the evidence for the robustness of the link between witnessed violence and behavior problems.

In summary, this study is the first to incorporate multi-source data and analytic techniques that simultaneously model the data from both informants to examine the link between witnessed violence and behavior problems. Findings suggest that discrepancies do exist between informants regarding both witnessed violence and behavior problems, supporting the inclusion of both sources as important for understanding the ‘true’ overall prevalence rate and links between exposures and behavioral problems. We further found an unexpected interaction between the informant and reports of witnessed violence for internalizing problems, such that the caregiver’s report of youth witnessed violence was associated with greater internalizing problems than was the youth’s reports.

The results of this study suggest that it is important to have both parent and youth perspectives on behavioral/emotional symptoms and on youths’ experiences, as both perspectives are important clinically and likely to comprise different truths (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005). Clinicians, service providers, and researchers should further assess the complex relationship between what youth and caregivers know about violence exposure as well as how that information may impact perceptions of behavior problems. Further, it may be important to assess whether discrepancies between informants may play a role in compounding the deleterious effects of violence exposure. In any case, the observed discrepancy and inability to establish which report is more accurate suggests that both caregiver and youth perspectives be assessed in order to provide the most comprehensive assessment of exposure to and consequences of violence exposure.

Contributor Information

Terri Lewis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Jonathan Kotch, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Richard Thompson, Juvenile Protective Association.

Alan J. Litrownik, San Diego State University

Diana J. English, University of Washington

Laura J. Proctor, San Diego State University

Desmond K. Runyan, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Howard Dubowitz, University of Maryland School of Medicine.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991a. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991b. [Google Scholar]

- Appel AE, Holden GW. The co-occurrence of spouse and physical child abuse: A review and appraisal. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:578–599. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.12.4.578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bair-Merritt MH, Blackstone M, Feudtner C. Physical health outcomes of childhood exposure to intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Pediatrics. 2006;117:E278–E290. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett D, Manly JT, Cicchetti D. Defining child maltreatment: The interface between policy and research. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Advances in applied developmental psychology: Child abuse, child development, and social policy. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1993. pp. 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Berg-Nielsen TS, Vika A, Dahl AA. When adolescents disagree with their mothers: CBCL-YSR discrepancies related to maternal depression and adolescent self-esteem. Child: Care, Health & Development. 2003;29:207–213. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2003.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Gould MS, Staghezza B. Aggregating data from multiple informants in child psychiatry epidemiological research. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31:78–85. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JC, Beardslee WR, Bassuk EL. Exposure to violence and low-income children’s mental health: Direct, moderated, and mediated relations. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74:413–423. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballo R, Dahl TA, Aretakis MT, Ramirez C. Inner-city children’s exposure to community violence: How much do parents know? Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2001;63:927–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00927.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coddington RD. The significance of life events as etiologic factors in the diseases of children-II. A study of a normal population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1972;16:205–213. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(72)90045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:483–509. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVoe ER, Smith EL. Don’t take my kids: Barriers to service delivery for battered mothers and their young children. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2003;3:277–294. doi: 10.1300/J135v03n03_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:50–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edleson J. The overlap between child maltreatment and woman battering. Violence Against Women. 1999;5:134–152. doi: 10.1177/107780129952003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ the LONGSCAN Investigators. Modified Maltreatment Classification System (MMCS) Unpublished Manual. 1997 Retrieved from http://www.iprc.unc.edu/longscan/pages/mmcs/LONGSCAN%20MMCS%20Coding.pdf.

- Evans SE, Davies C, DiLillo D. Exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis of child and adolescent outcomes. Aggressive and Violent Behavior. 2008;13:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Everson MD, Smith JB, Hussey JM, English D, Litrownik AJ, Dubowitz H, Runyan D. Concordance between adolescent reports of childhood abuse and Child Protective Service determinations in an at-risk sample of young adolescents. Child maltreatment. 2008;13:14–26. doi: 10.1177/1077559507307837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdinand RF, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Prognostic value of parent-adolescent disagreement in a referred sample. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;15:156–162. doi: 10.1007/s00787-005-0518-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to interparental violence in childhood and psychosocial adjustment in young adulthood. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1998;22:339–357. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, Turner H, Hamby S. The victimization of children and youth: A comprehensive, national survey. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:5–25. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, Turner H, Hamby S. Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldwasser M, Fitzmaurice GM. Multivariate linear regression analysis of childhood psychopathology using multiple informant data. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2001;10:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra NG, Huesmann LR, Spindler A. Community violence exposure, social cognition, and aggression among urban elementary school children. Child Development. 2003;74:1561–1576. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RF, Self-Brown S, Fricker-Elhai AE, Kilpatrick DG, Saunders BE, Resnick HS. The relations between family environment and violence exposure among youth: Findings from the national survey of adolescents. Child Maltreatment. 2006;11:3–15. doi: 10.1177/1077559505279295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill H, Jones LP. Children’s and parents’ perceptions of children’s exposure to violence in urban neighborhoods. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1997;89(4):270–276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton NJ, Fitzmaurice GM. Regression analysis of multiple source and multiple informant data from complex survey samples. Statistics in Medicine. 2004;23:2911–2933. doi: 10.1002/sim.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt H, Malmud E, Brodsky NL, Giannetta J. Exposure to violence - Psychological and academic correlates in child witnesses. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2001;155:1351–1356. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.12.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Marshall JM, English DJ, Knight ED, Lau AS, Dubowitz H, Kotch JB. Defining maltreatment according to substantiation: distinction without a difference? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(5):479–92. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RM, Kotch JB, Catellier DJ, Winsor JR, Dufort V, Hunter W, Amaya-Jackson L. Adverse behavioral and emotional outcomes from child abuse and witnessed violence. Child Maltreatment. 2002;7:179–187. doi: 10.1177/1077559502007003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight ED, Smith JS, Martin LM, Lewis T the LONGSCAN Investigators. Self-report of physical maltreatment and assault; self-report of psychological maltreatment; self-report of sexual abuse and assault. Measures for assessment of functioning and outcomes in longitudinal research on child abuse: Vol. 3. Early Adolescence (Ages 12–14) 2008 Retrieved from http://www.iprc.unc.edu/longscan/pages/measures/Ages12to14/index.html.

- Kohl PL, Jonson-Reid M, Drake B. Time to leave substantiation behind: findings from a national probability study. Child maltreatment. 2009;14:17–26. doi: 10.1177/1077559508326030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo M, Mohler B, Raudenbush SL, Earls FJ. Assessing exposure to violence using multiple informants: Application of hierarchical linear model. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:1049–1056. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litrownik AJ, Newton R, Hunter WM, English D, Everson MD. Exposure to family violence in young at-risk children: A longitudinal look at the effects of victimization and witnessed physical and psychological aggression. Journal of Family Violence. 2003;18:59–73. doi: 10.1023/A:1021405515323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LONGSCAN. Child’s life events. In: Hunter WM, Cox CE, Teagl S, Johnson RM, Mathew R, Knight ED, et al., editors. Measures for assessment of functioning and outcomes in longitudinal research on child abuse. Vol. 2. Middle Childhood; 1992. 2003. Retrieved from http://www.iprc.unc.edu/longscan/pages/measures/Ages5to11/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- LONGSCAN; History of witnessed violence. Knight ED, Smith JS, Martin LM, Lewis T, editors. the LONGSCAN Investigators. Measures for assessment of functioning and outcomes in longitudinal research on child abuse. Volume 3: Early Adolescence (Ages 12–14) 1998 2008. Retrieved from http://www.iprc.unc.edu/longscan/pages/measures/Ages12to14/index.html.

- Maschi T. Unraveling the link between trauma and male delinquency: The cumulative versus differential risk perspectives. Social Work. 2006;51:59–70. doi: 10.1093/sw/51.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Donnelly WO, Boxer P, Lewis T. Marital and severe parent-to-adolescent physical aggression in clinic-referred families: Mother and adolescent reports on co-occurrence and links to child behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:3–19. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R, Jouriles EN, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Caetano R, Green CE. Estimating the number of American children living in partner-violent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:137–142. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LS, Wasserman GA, Neugebauer R, Gorman-Smith D, Kamboukos D. Witnessed community violence and antisocial behavior in high-risk, urban boys. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:2–11. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2801_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary K, Smith Slep AM, O’Leary S. Co-occurrence of partner and parent aggression: Research and treatment implications. Behavior Therapy. 2000;31:631–648. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(00)80035-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patchin JW, Huebner BM, McCluskey JD, Varano SP, Bynum TS. Exposure to community violence and childhood delinquency. Crime and Delinquency. 2006;52:307–332. doi: 10.1177/0011128704267476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Maltreatment. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Richters JE, Martinez P. Unpublished manuscript. 1990. Things I’ve Seen and Heard: An interview for young children about exposure to violence. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Stipec M, Fitzmaurice G, Murphy J, Walker A. The use of multiple informants in identifying the risk factors of depressive and disruptive disorders: Are they interchangeable? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2003;38:51–58. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0600-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runyan DK, Curtis P, Hunter W, Black MM, Kotch JB, Bangdiwala S, et al. LONGSCAN: A consortium for longitudinal studies of maltreatment and the life course of children. Aggression & Violent Behavior: A Review Journal. 1998;3:275–285. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(96)00027-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. Computer Software. SAS Campus Drive; Cary, North Carolina 27513: (Version 9.1) [Google Scholar]

- Star R, Dubowitz H, Harrington D, Feigelman S. Behavior problems of teens in kinship care: Cross-informant reports. In: Scannapieco M, Hegar RL, editors. Kinship foster care: Policy practice and research. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1999. pp. 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R, Briggs E, English DJ, Dubowitz H, Lee LC, Brody K, Everson MD, Hunter WM. Suicidal ideation among maltreated and at-risk 8-year-olds: Findings from the LONGSCAN studies. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:26–36. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, Ruggiero KJ, Resnick H, Hanson R, Smith D, Saunders B, Kilpatrick D. Prevalence and mental health correlates of witnessed parental and community violence in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:441–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]