Abstract

Resistance of myeloma to lenalidomide is an emerging clinical problem, and though it has been associated in part with activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, the mediators of this phenotype remained undefined. Lenalidomide-resistant models were found to overexpress the hyaluronan (HA)-binding protein CD44, a downstream Wnt/β-catenin transcriptional target. Consistent with a role of CD44 in cell adhesion-mediated drug-resistance (CAM-DR), lenalidomide-resistant myeloma cells were more adhesive to bone marrow stroma and HA-coated plates. Blockade of CD44 with monoclonal antibodies, free HA, or CD44 knockdown reduced adhesion and sensitized to lenalidomide. Wnt/β-catenin suppression by FH535 enhanced the activity of lenalidomide, as did interleukin-6 neutralization with siltuximab. Notably, all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) down-regulated total β-catenin, cell-surface and total CD44, reduced adhesion of lenalidomide-resistant myeloma cells, and enhanced the activity of lenalidomide in a lenalidomide-resistant in vivo murine xenograft model. Finally, ATRA sensitized primary myeloma samples from patients that had relapsed and/or refractory disease after lenalidomide therapy to this immunomodulatory agent ex vivo. Taken together, our findings support the hypotheses that CD44 and CAM-DR contribute to lenalidomide-resistance in multiple myeloma, that CD44 should be evaluated as a putative biomarker of sensitivity to lenalidomide, and that ATRA or other approaches that target CD44 may overcome clinical lenalidomide resistance.

Keywords: CD44, ATRA, lenalidomide, drug-resistance

Introduction

Lenalidomide belongs to a class of immunomodulatory agents that is increasingly used in the frontline, relapsed/refractory, and maintenance settings for multiple myeloma.(1, 2) Despite its broad effectiveness as a single agent, and in a number of combination regimens, the vast majority of patients eventually develop disease that demonstrates clinical lenalidomide resistance. Previously published studies from our group demonstrated that Wnt/β-catenin signaling was activated in plasma cells following acute or chronic exposure to lenalidomide.(3) However, these studies did not identify down-stream mediators of the resistant phenotype, and did not validate approaches that could be translated to the clinic to overcome resistance.

One molecule of interest we considered as a potential mediator of resistance was CD44, a known β-catenin transcriptional target(4) which is a functional component of cell adhesion-mediated drug resistance (CAM-DR).(5) A role for CD44 as a mediator of CAM-DR has been described in several cancers,(6–8) and it may in part mediate dexamethasone resistance in myeloma.(9) CD44 is a single-pass, glycosylated class-I transmembrane protein involved in multiple cellular functions, including interaction with the matrix microenvironment and intracellular signaling.(5) The extracellular portion of CD44 primarily binds to the glycosaminoglycan hyaluronan (HA), thereby contributing to cell adhesion, migration, angiogenesis, inflammation, wound healing and downstream signaling that promotes cell growth and survival.(5) An extracellular domain of CD44 can be cleaved and found as a soluble entity in the serum, where it has been identified as a biomarker correlating with poor outcomes in solid tumors such as the colon,(10) as well as hematologic malignancies such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma,(11) and possibly myeloma.(12) Finally, serum HA itself may be a predictive marker of a poor prognosis for multiple myeloma.(13) These factors led us to consider the hypothesis that CD44 could be one mediator of the lenalidomide-resistant phenotype in myeloma, and that its targeting could lead to lenalidomide sensitization, and possibly overcome resistance.

In the current studies, we show that models of Wnt/β-catenin-dependent lenalidomide-resistant myeloma demonstrated enhanced CD44 expression. This resulted in an increase in adhesive properties to stroma and HA, while CD44 blockade, or shRNA-mediated suppression, enhanced lenalidomide’s anti-proliferative effects. Sensitivity to lenalidomide in drug-naïve models, and activity of lenalidomide against drug-resistant models, was enhanced using clinically relevant agents that impact CD44, such as all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA). Finally, the combination of ATRA with lenalidomide enhanced activity against primary plasma cells, including from patients with lenalidomide-resistant disease, and showed anti-tumor efficacy in an in vivo model. These data support the translation of ATRA or anti-CD44 antibodies to the clinic with lenalidomide as a rational strategy to overcome lenalidomide-resistance.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and primary samples

Drug-naïve and lenalidomide-resistant myeloma cell lines were maintained as described previously.(3) Cell line authentication was performed by our Cell Line Characterization Core using short tandem repeat profiling. Lenalidomide was removed from culture for at least seven days prior to all experiments, unless indicated otherwise. Primary plasma cells were purified from bone marrow aspirates collected from patients under an approved protocol from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center after informed consent was obtained in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Viability assays

Proliferation and viability assays with lenalidomide (Selleck Chem.; Houston, TX), and IM9 CD44 blocking (Abcam; Cambridge, MA), humanized monoclonal anti-CD44 (RO5429083; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Penzberg, Germany) and anti-interleukin (IL)-6 antibodies (Siltuximab; Janssen Biotech, Inc.; Horshma, PA), FH535 (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis. MO), or ATRA (Sigma-Aldrich), were performed as described.(3) Briefly, cell lines or primary samples were treated with either the indicated compound or antibody for a minimum of 72 hours unless otherwise indicated, followed by the addition of WST-1, and colorimetric detection of metabolic activity on a Perkin Elmer Victor3V plate reader (Waltham, MA). Data were then normalized to vehicle controls, which were arbitrarily set at 100 % viability. All data points are represented as the mean with the standard deviation (SD).

Immunoblotting

Cells were harvested and lysed in 1x lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology; Danvers, MA), followed by resolution on gradient gels (Invitrogen), transferred to nitrocellulose (BioRad), and probed with the indicated antibody. Primary pan-anti-CD44 and anti-β-catenin antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology and anti-β-actin was from Sigma. Densitometric quantitation was obtained using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health; http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/), and normalized to β-actin, and either vehicle-treated or wild-type controls, which were arbitrarily set to 1.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen), and cDNA was synthesized using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA). Quantitative real-time (q) PCR was performed using the TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix and the β-catenin (FAM), CD44 (FAM), and GAPDH (VIC) TaqMan Gene Expression Assays as multiplexed, triplicate samples on a StepOnePlus PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Relative quantification was done using the comparative CT method after normalization to the internal GAPDH control, where all samples were then normalized to wild-type or vehicle controls.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

Cell suspensions were stained with either Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated anti-CD44 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) or an isotype matched control (mouse IgG2a; R&D Systems), processed on a BD Biosciences FACSCanto II flow cytometer, and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc.; Ashland, OR). Quantification of CD44 levels was done by normalizing the mean fluorescent intensity with the isotype control, and then to wild-type or vehicle controls. Representative figures are shown from triplicate experiments and identified as the mean ± SD. For CD44 fractionation, lenalidomide-sensitive wild-type cells were stained with the above-described CD44 antibody, and collected into CD44-High and CD44-Low fractions on a BD Biosciences FACSAria III cell sorter. For apoptosis assays, cells were stained with Pacific Blue-conjugated Annexin V antibody and To-Pro-3 (both from Invitrogen). Cell cycle analysis was performed by fixing cells and staining with propidium iodide (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell adhesion assays

HS5-GFP cells were allowed to attach overnight, and myeloma cells pre-stained with 10 μM Calcein Blue-AM (Invitrogen) were added to stromal cells. Unattached cells were removed, followed by limited trypsin digestion and scraping to remove the HS5-GFP and myeloma cells. Samples were analyzed on a FACSCanto II flow cytometer, and the percentage of events that were GFP−/Calcein Blue-AM+ was determined. The relative percent adhered was calculated by: ((cell number attached fraction)/(cell number attached fraction + cell number unattached fraction))*100, followed by normalization to wild-type or vehicle controls. To perform assays in HA-coated plates, 100 μg/mL (or the indicated concentration) of rooster comb HA (Sigma) was added to polystyrene plates, which were incubated overnight and then blocked with heat-denatured BSA. Myeloma cells were allowed to adhere followed by gentle washing. Attached cells were resuspended in media and analyzed for relative adhesion with the WST-1 reagent (Roche). All cell adhesion assays were performed in triplicate, and data are presented as the mean ± SD.

CD44 knockdown

Lentiviral-based shRNAs targeted to CD44 (Addgene; Cambridge, MA), or a non-specific scrambled control, were transfected with packaging vectors using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) into HEK293 cells. Concentrated supernatant was used to transduce lenalidomide-sensitive or -resistant cells, which were selected with puromycin (Sigma).

Xenograft modeling

Lenalidomide-resistant U266/R10R cells (7.5×106/mouse) were subcutaneously xenografted into 6-week old non-obese diabetic severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD SCID) mice (NOD.Cg-Prkdc(scid) Il2rg(tm1Wjl)/SzJ; Jackson Laboratories; Bar Harbor, ME) with MatriGel (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA) under a protocol approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Facility. Treatments were administered by intraperitoneal injection using peanut oil as a carrier thrice weekly, starting on day 7 post-implantation. Tumors were monitored by caliper measurement and tumor volume was determined using the equation volume=0.4LxW2.

Xenograft statistical analysis

An unstructured covariance structure was used to account for inter-mouse variability and the longitudinal nature of the data. An interaction between treatment and time was assessed to test the heterogeneity of slopes, i.e., the tumor growth rate. CONTRAST statement in PROC MIXED procedure in SAS was used to compare the tumor growth rates between each pair of treatment groups. The tumor volume was log-transformed to satisfy the normality assumption of the models. Pair-wise differences between the combination group (lenalidomide + ATRA) vs. ATRA alone, combination vs. lenalidomide, combination vs. control, lenalidomide vs. control and ATRA vs. control were examined using ESTIMATE statement in PROC MIXED for each time point. Statistically significant determinations were made by calculation of the probability of χ2. Cooperative effects of the combination of lenalidomide and ATRA are assessed using a Bayesian bootstrap procedure. We calculated Pr(min(μL, μA)>μC |data)(i.e., the posterior probability that the minimum of the two posterior mean tumor volumes for lenalidomide alone, μL, or ATRA alone, μA, was greater than the mean posterior tumor volume for the combination μC). Cooperative effects are shown if this posterior probability is large. The cooperative effects of the combination on tumor volume were assessed at each time, separately. SAS version 9.1 and S-Plus version 8.0 were used to carry out the computations for all analyses.

Results

Lenalidomide-resistant cells over-express CD44

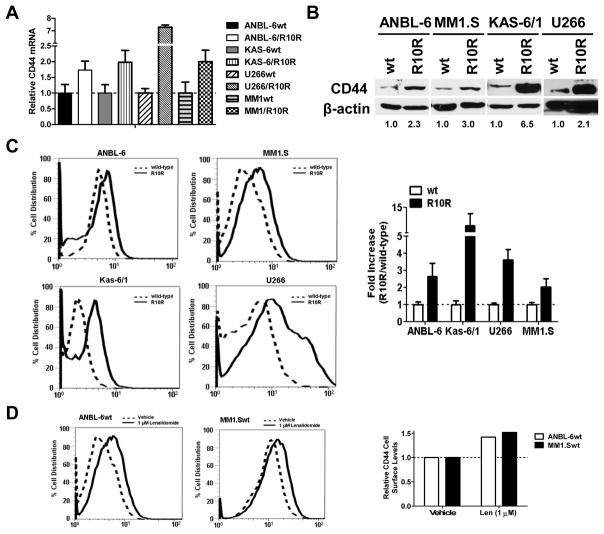

Previous findings from our group identified activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway as being associated with lenalidomide resistance in a dose- and time-dependent fashion in our novel lenalidomide-resistant model cell lines compared to vehicle-treated controls.(3) Additional analysis of gene expression profiling data comparing lenalidomide-resistant cells with their sensitive counterparts revealed up-regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin downstream target CD44 (data not shown). To further validate these findings, we performed qPCR comparing resistant (R10R) ANBL-6, KAS-6/1, U266, and MM1.S cells with wild-type (wt), drug-naïve controls. Lenalidomide-resistant cells consistently showed enhanced CD44 mRNA levels by up to 7-fold or more in each of the cell line models (Figure 1A). Enhanced CD44 transcription resulted in increased levels of total cellular CD44 protein, as judged by Western blotting (Figure 1B), with increases ranging up to 6.5-fold. Surface CD44 expression was then determined using FACS, and in all four lenalidomide-resistant cell lines, enhanced CD44 expression was seen. Quantification of the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) following normalization to the isotype control showed an increase of CD44 at the cell surface ranging from a 2-fold to an 11-fold increase (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Lenalidomide resistance and CD44 expression in myeloma cells.

(A) Lenalidomide-sensitive wild-type (wt) and lenalidomide-resistant (R10R) cells were subjected to qPCR, and CD44 mRNA content was analyzed using the comparative CT method and normalized to GAPDH internal control. CD44 expression in drug-naïve wt cells was arbitrarily set at 1.0, and representative data are shown from one of three independent experiments along with the S.D. (B) CD44 protein levels were evaluated in drug-naïve and lenalidomide-resistant cells by Western blotting. Densitometric quantitation of the total CD44 levels is shown from one of two independent experiments, and was first normalized to the β-actin loading control, and then compared to wild-type levels, which were arbitrarily set at 1.0. (C) Lenalidomide-sensitive (dotted line) and -resistant (solid line) cells were subjected to FACS analysis to determine the levels of cell surface CD44 using an Alexa Fluor® 488 conjugated CD44 antibody. On the left, a representative FACS profile is shown from one of three independent experiments, each of which collected 20,000 events. Quantitative analysis of the mean fluorescent intensity of these data was then used to calculate the fold-increase of surface CD44 levels in the lenalidomide-resistant cells following normalization to the isotype control, which is displayed on the right.

Lenalidomide-resistant cells show greater adhesive properties

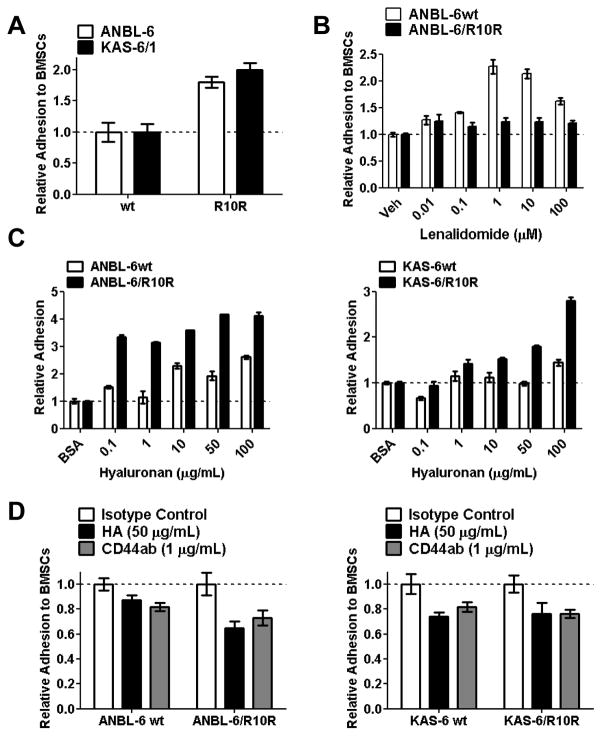

To determine whether enhanced CD44 expression influenced CAM-DR in lenalidomide-resistant cells, we first studied their adhesive properties to bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs). Compared to their wild-type, drug-naive counterparts, lenalidomide-resistant ANBL-6/R10R and KAS-6/R10R cells were about twice as likely to be found attached to HS5 BMSCs (Figure 2A). Hyaluronan-coated plates were then used to measure the relative adherence of these cells to increasing immobilized-HA concentrations. As had been the case for BMSCs, lenalidomide-resistant ANBL-6/R10R (Figure 2B, left panel) and KAS-6/R10R cells (Figure 2B, right panel) were more likely to be found adherent to HA-coated plates than their wt controls, and their adhesion increased in a manner dependent on the HA concentration. Conversely, blockade of CD44 engagement to immobilized HA by prior incubation with either a CD44 neutralizing antibody, or free HA, resulted in a 30–35% reduction in adhesion of either lenalidomide-sensitive ANBL-6wt, or lenalidomide-resistant ANBL-6/R10R cells to a BMSC monolayer (Figure 2C, left panel). Interestingly, this effect was less pronounced in the lenalidomide-resistant KAS-6/R10R cells, where there was a reduction in adhesion by the CD44 antibody or free HA of only 10–20% (Figure 2C, right panel).

Figure 2. Adhesive properties of drug-resistant and-na.

ïve cells.

(A) HS5-GFP bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) were plated and allowed to adhere overnight, and Calcein Blue AM+, lenalidomide-sensitive wt or lenalidomide-resistant ANBL-6 or KAS-6 cells were then added. Non-adherent cells were subsequently washed off and the GFP−/Calcein Blue AM+ signal was measured. The percentage of adhesion was calculated as described in the “Materials and Methods,” and normalized to the adhesion of wt cells, which were arbitrarily set at 1.0. (B) Lenalidomide-sensitive and -resistant ANBL-6 and KAS-6/1 cells were evaluated for their ability to adhere to increasing concentrations of hyaluranon (HA) immobilized in culture plates, and evaluated as above. (C) Free hyaluronan or a CD44 blocking antibody were pre-incubated with the indicated myeloma cell lines, which were then allowed to adhere to BMSCs and analyzed as above. Relative adhesion was determined and compared to an isotype control, with data displayed as the mean ± S.D. All results are representative of three independent experiments.

Blocking the CD44/HA interaction induces cytotoxicity

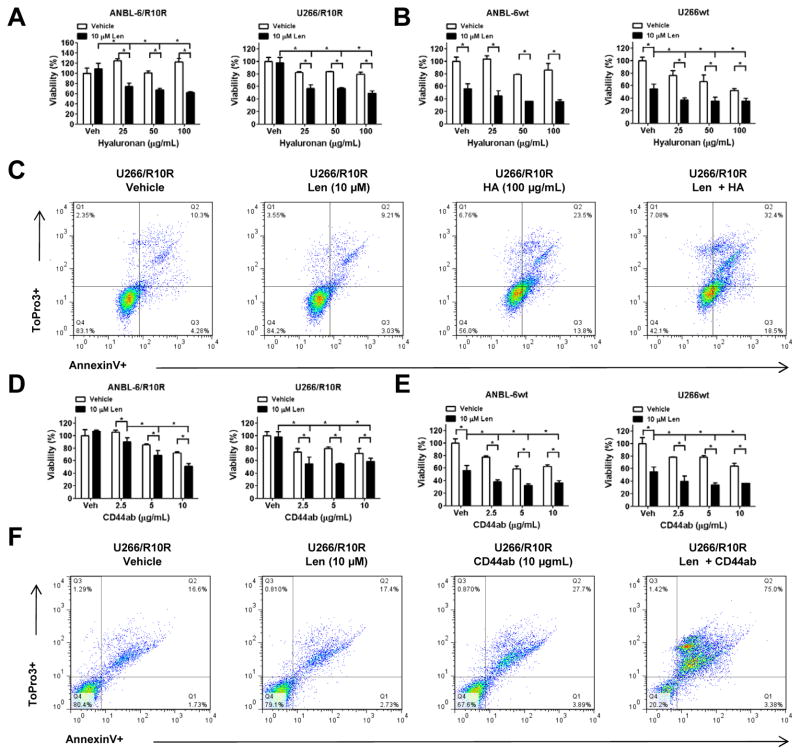

Given the enhanced adhesive properties of lenalidomide-resistant cells associated with increased CD44 expression, we next considered the possibility that interfering with the CD44/HA interaction could be of therapeutic benefit. This was first tested by adding exogenous HA to saturate myeloma cell surface CD44, and prevent its binding to HA-coated plates. When lenalidomide-resistant ANBL-6/R10R and U266/R10R cells were incubated with free HA, mild anti-proliferative effects were seen (Figure 3A), especially in the U266 model, which, notably, has even higher CD44 expression than ANBL-6 cells (Figure 1C). Lenalidomide alone without hyaluronan showed no activity against the resistant cells, as expected, but when lenalidomide was added in the presence of pre-treatment with HA, lenalidomide sensitivity was restored, and substantial reductions in cell proliferation were seen. Drug-naïve ANBL-6wt and U266wt cells were then exposed to lenalidomide with or without HA (Figure 3B). Qualitatively similar findings were obtained, and the combination showed enhanced effects, except that lenalidomide alone was sufficient to reduce cellular viability, again as expected. To examine the mechanism behind this interaction, U266/R10R cells incubated with vehicle, lenalidomide, HA, or HA and then lenalidomide were analyzed by staining for Annexin V and with To-Pro-3 (Figure 3C). Lenalidomide alone did not substantially alter the proportion of Annexin V+ cells compared to the vehicle, where 14.5% of cells were apoptotic. In the presence of HA, 37.1% of cells were Annexin V+, while HA followed by lenalidomide increased this to 50.9%, indicating that type I programmed cell death was contributing to the enhanced anti-proliferative effects of HA and lenalidomide. Since hyaluronan would not be relevant to the clinic, we next evaluated the efficacy of a humanized monoclonal anti-CD44 antibody (RO5429083). As a single agent, RO5429083 exerted a modest anti-proliferative effect, with an approximately 20% reduction in viability against both ANBL-6/R10R and U266/R10R cells (Figure 3D). Notably, while lenalidomide alone was ineffective, RO5429083 with lenalidomide was more active than the antibody alone in the absence of any effector cells to mediate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Comparable findings were seen in the drug-naïve ANBL-6 and U266 cells (Figure 3E), except that both lenalidomide and RO5429083 were active as single agents. Finally, the lenalidomide/RO5429083 combination activated apoptosis in virtually all of the U266/R10R cells (Figure 3F).

Figure 3. Impact of CD44 blockade on the effectiveness of lenalidomide.

(A) Utilizing immobilized HA to represent the marrow microenvironment, lenalidomide-resistant ANBL-6 and U266 cells were pre-incubated with increasing concentrations of free HA (25–100 μg/mL). They were then exposed either to vehicle or lenalidomide for 72 hours, and viability was determined with the tetrazolium reagent WST-1. Data are from three independent experiments, and are presented as the mean ± S.D., with “*” representing statistical significance at a level of p<0.05 using the student’s paired t-test. (B) The experiment described in panel A was performed with lenalidomide-naïve ANBL-6 and U266 cells to study the impact of CD44 blockade on the acute effects of lenalidomide. (C) FACS analysis was used to determine the proportion of apoptotic (Annexin V+) cells in the U266 model system after the above-described experiments. (D) Again utilizing immobilized HA to represent the marrow microenvironment, lenalidomide-resistant ANBL-6 and U266 cells were pre-incubated with increasing concentrations of a humanized anti-CD44 monoclonal antibody (RO5429083). They were then exposed either to vehicle or lenalidomide for 72 hours, and viability was determined with the tetrazolium reagent WST-1. Data are from three independent experiments, and are presented as the mean ± S.D., with “*” representing statistical significance at a level of p<0.05 using the student’s paired t-test. (E) The experiment described in panel D was performed with lenalidomide-naïve ANBL-6 and U266 cells to study the impact of CD44 blockade on the acute effects of lenalidomide. (F) FACS analysis was used to determine the proportion of apoptotic (Annexin V+) cells in the U266 model system after the above-described experiments.

CD44 suppression sensitizes myeloma cells to lenalidomide

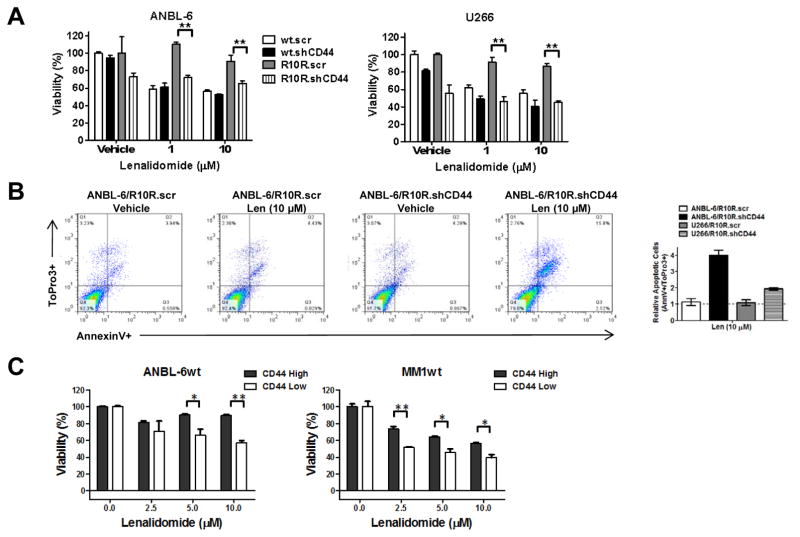

In that HA may mediate effects through mechanisms other than targeting CD44, it was of interest to verify that CD44 was itself involved in lenalidomide resistance. We therefore generated ANBL-6 and U266 cell lines in which both the wt and R10R cells were infected with Lentiviral vectors expressing a scrambled sequence (.scr) shRNA, or one targeting and suppressing CD44 (.shCD44; Supplementary Figure 1). These cells were then seeded onto HA-coated plates, exposed to lenalidomide, and evaluated for viability. Lenalidomide-resistant ANBL-6/R10R (Figure 4A, left panel) and U266/R10R (Figure 4A, right panel) were markedly sensitized to lenalidomide by CD44 knockdown compared to the scrambled control. In contrast, relatively modest effects were seen in the lenalidomide-sensitive wild-type cells, suggesting a lesser dependence on CD44 for survival. The effect of CD44 knockdown on apoptosis was then studied by FACS analysis in ANBL-6 (Figure 4B, left panel) and U266 cells (not shown), which revealed that this maneuver enhanced the ability of lenalidomide to induce apoptosis by up to 4-fold (Figure 4B, right panel). In an attempt to show the reverse effect, we tried to overexpress the full length CD44 (Origene–NM_000610), however this overexpression appeared to be lethal by both transient transfection in HEK293 cells, and by Lentiviral transduction in lenalidomide-sensitive U266 or ANBL-6 cells (data not shown). As an alternative approach, we reasoned that since the emergence of drug-resistant clones could be due to the induction of a new phenotype, or to the selection of a pre-existing sub-population, we fractionated ANBL-6wt and MM1.Swt cells into CD44-High and CD44-Low expressing populations (Supplementary Figure 2). Following treatment with lenalidomide, viability assays showed a significant disparity between these populations, with the CD44-Low cells demonstrating greater lenalidomide sensitivity compared to the CD44-High population in the presence of immobilized HA (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. CD44 expression level and lenalidomide sensitivity.

(A) Lenalidomide-sensitive and -resistant ANBL-6 and U266 cells were infected with Lentiviral particles containing shRNA constructs targeted to a non-specific scrambled sequence (.scr), or to CD44 (.shCD44). Stable clones with verified knockdown propagated on HA-coated plates were then exposed to lenalidomide, and viability was analyzed utilizing the WST-1 assay. Mean viability values are provided from three independent experiments ± S.D., and the student’s paired t-test was used to determine statistical significance, where “**” denotes p<0.01. (B) FACS analysis of these ANBL-6 and U266 models was then performed to examine the proportion of apoptotic (Annexin V+) cells. The fold-increase in the apoptotic cell population is shown on the right, and was obtained by normalizing the % apoptosis for scrambled controls to 1.0. (C) Lenalidomide-sensitive ANBL-6 and MM1.S cells were sorted into CD44-High and CD44-Low populations, and treated with lenalidomide at the indicated concentrations for 72 hours. Cellular viability measurements were then performed using the WST-1 assay, and all data points were normalized to the vehicle control, which was arbitrarily set at 100%. Mean viability values are provided from three independent experiments ± S.D., and the student’s paired t-test was used to determine statistical significance, where “*” denotes p<0.05, and “**” denotes p<0.01.

Clinically relevant approaches to re-sensitize to lenalidomide

Lenalidomide resistance is an emerging clinical problem, and we therefore wanted to validate novel approaches that could recapture lenalidomide sensitivity. Signaling through IL-6 is known to regulate the cell surface expression of CD44 in myeloma cells.(14) We therefore reasoned that IL-6 blockade could undermine CD44-mediated lenalidomide-resistance, and used siltuximab, a neutralizing anti-IL-6 antibody that has shown pre-clinical activity against myeloma.(15–17) IL-6-dependent, lenalidomide-resistant ANBL-6/R10R and KAS-6/R10R cells were therefore exposed to siltuximab or lenalidomide alone, as well as in combination (Supplementary Figure 3A). As expected, lenalidomide alone showed no activity, and while siltuximab did reduce viability, this was enhanced with the combination, consistent with resensitization to lenalidomide. Moreover, in drug-naïve cells (Supplementary Figure 3B), a greater reduction in viability was seen with the combination, suggesting a chemosensitizing effect. In the small molecule category, we evaluated FH535(18), a novel β-catenin/T-cell factor (TCF) antagonist. The combination of lenalidomide and FH535 significantly reduced the viability of KAS-6/R10R and U266/R10R cells (Supplementary Figure 4A) even under conditions when either agent alone showed minimal activity, and additive or greater activity was seen in drug-naïve models as well (Supplementary Figure 4B).

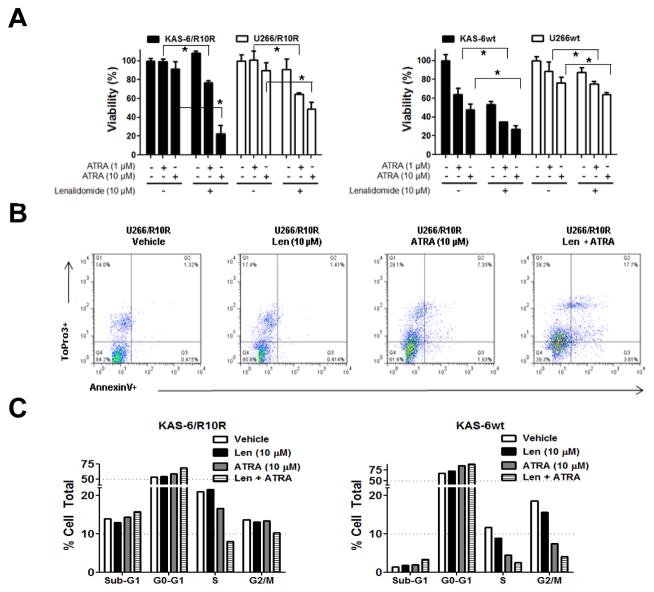

Since neither siltuximab nor FH535 are available outside of clinical trials, we next evaluated ATRA, which alters the sub-cellular distribution of β-catenin,(19) induces it’s ubiquitin-dependent degradation,(20) inactivates β-catenin-dependent signaling,(21) and reduces CD44 expression.(21, 22) ATRA reduced basal β-catenin-dependent lymphoid enhancer factor (LEF)/TCF promoter activity in KAS-6wt cells (Supplementary Figure 5A), and reversed the acute, lenalidomide-stimulated activation of LEF/TCF in a time- and concentration-dependent manner (Supplementary Figure 5B). As a single agent, ATRA had minimal effects against lenalidomide-resistant KAS-6/1 and U266 cells (Figure 5A, left panel), but this increased substantially in the presence of lenalidomide, which by itself was inactive. In drug-naïve cells, ATRA showed greater activity, and again enhanced the efficacy of lenalidomide (Figure 5A, right panel). Lenalidomide also increased by more than 2-fold the percentage of cells that stained for the early apoptotic marker Annexin V when used in combination with ATRA in U266/R10R cells (Figure 5B). Analysis of cell cycle effects indicated that ATRA or lenalidomide alone induced a G1 arrest, but this was greatly enhanced when the two drugs were combined in either lenalidomide-sensitive or lenalidomide-resistant KAS-6/1 cells (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Pharmacologic suppression of Wnt/β-catenin and lenalidomide sensitivity.

(A) Lenalidomide-resistant KAS-6 and U266 cells (left side), or their lenalidomide-sensitive counterparts (right side) were exposed to the indicated concentrations of ATRA either without or with lenalidomide. Cellular viability measurements were then performed using the WST-1 assay, and all data points were normalized to the vehicle control, which was arbitrarily set at 100%. Mean viability values are provided from three independent experiments ± S.D., and the student’s paired t-test was used to determine statistical significance, where “*” denotes p<0.05. (B) FACS analysis of lenalidomide-resistant U266 cells was performed to examine the proportion of apoptotic (Annexin V+) cells after exposure to vehicle, lenalidomide, ATRA, or the combination. (C) Cell cycle profiling was performed by propidium iodide staining and FACS analysis of KAS-6wt and KAS-6/R10R cells following the indicated treatments.

Molecular effects of ATRA

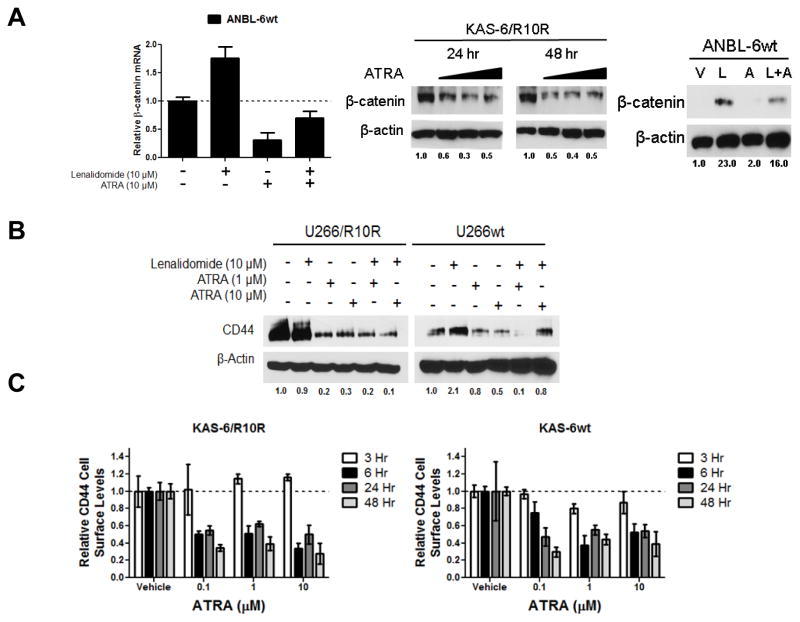

To further examine the molecular mechanisms by which ATRA was working, we studied its impact on β-catenin transcription using qPCR. ANBL-6 cells exposed to ATRA showed a dramatic decrease in β-catenin mRNA levels, and while lenalidomide increased these, ATRA suppressed this effect (Figure 6A, left panel). ATRA also reduced β-catenin protein levels in lenalidomide-resistant KAS-6/1 cells (Figure 6A, middle panel), and impeded the ability of lenalidomide to cause β-catenin accumulation (Figure 6A, right panel). Our earlier data suggested that CD44 was a mediator of the resistant phenotype induced by β-catenin activation, and ATRA was found to reduce CD44 expression in both drug-naïve and lenalidomide-resistant cells at baseline (Figure 6B). Moreover, ATRA precluded the ability of lenalidomide to induce CD44 expression in wt cells. Finally, exposure of lenalidomide-resistant KAS-6/R10R cells to ATRA resulted in rapid down-regulation of cell surface CD44 in as little as 6 hours (Figure 6C, left panel), with concentrations as low as 0.1 μM. This effect was also notable in drug-naïve cells, consistent with the ability of ATRA to suppress Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Figure 6. Molecular correlates of ATRA action in lenalidomide-resistant myeloma.

(A) Lenalidomide-sensitive ANBL-6 cells were exposed to either vehicle, lenalidomide, ATRA, or the combination for 72 hours, and β-catenin mRNA levels were determined by qPCR using the comparative CT method. Values were normalized to GAPDH as an internal control, and the vehicle condition was arbitrarily set at 1.0 (left panel). The influence of ATRA on β-catenin protein levels was verified by Western blotting in KAS-6 lenalidomide-resistant treated with ATRA alone (middle panel), and in ANBL-6 drug-naïve cells exposed to vehicle, lenalidomide (L), ATRA (A), or both (L+A). β-actin is displayed as a loading control, and densitometry was performed to quantify β-catenin levels, which were normalized to vehicle controls arbitrarily set to 1.0. Representative blots from one of three experiments are shown. (B) Lenalidomide-sensitive and -resistant U266 cells were exposed to vehicle, lenalidomide, ATRA, or the combination for 72 hours. Western blotting was then performed to determine the total cellular content of CD44 with β-actin serving as a loading control, while quantitation was performed as described for panel A. (C) Cell surface levels of CD44 were determined by FACS utilizing an Alexa Fluor® 488 conjugated anti-CD44 antibody following exposure to ATRA at the indicated concentrations for 3, 6, 24, or 48 hours. All values were normalized to the respective vehicle control, which was arbitrarily set at 1.0, and are represented as relative CD44 cell surface levels from one of two representative and independent experiments.

ATRA overcomes lenalidomide resistance in vivo and in primary samples

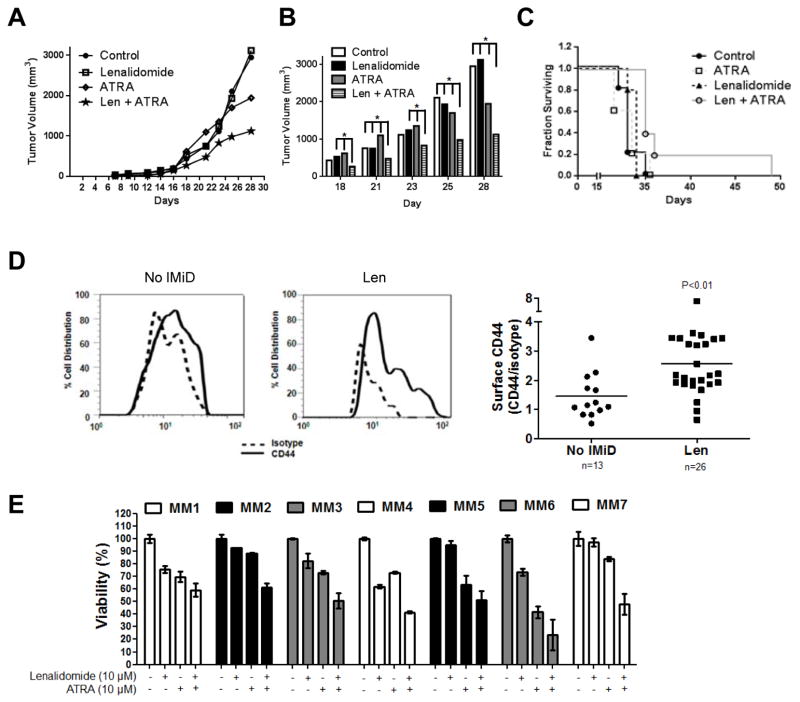

It was also of interest to validate the ability of ATRA to enhance the cytotoxic effects of lenalidomide in vivo, and we therefore used immunodeficient mice and U266/R10R cells to develop a lenalidomide-resistant xenograft model. Seven days after inoculation, these mice were randomized to treatment with intraperitoneal injections of vehicle, lenalidomide, ATRA, or lenalidomide with ATRA. While lenalidomide did not induce tumor growth delay, ATRA alone did show some activity in this setting (Figure 7A). Notably, the lenalidomide/ATRA combination significantly reduced tumor growth compared to either agent alone (Figure 7B), and also showed a trend towards prolonging survival (Figure 7C). Additional statistical analysis suggested that these two drugs show a cooperative effect when used together which was seen by day 16, and peaked at day 21 (Supplemental Figure 6).

Figure 7. Efficacy of ATRA in lenalidomide-resistant in vivo and ex vivo models.

(A) Immunodeficient mice were subcutaneously implanted with lenalidomide-resistant U266 cells, and after seven days were randomized to treatment with either vehicle, lenalidomide (50 mg/kg), ATRA (40 mg/kg), or the combination, with treatment given thrice weekly via intraperitoneal injection. Tumor growth was monitored by caliper measurement and calculated as tumor volume using the equation (0.4 x L x W^2). Each group had 5 mice, and the calculated p value between the control group and the combination group was 0.1. (B) Measured tumor volume from mouse xenografts from day 18 through day 28 of the experiment described in panel A. Statistically significant values are indicated by * which denotes p<0.05 as determined by the conditional χ2-test as explained in materials and methods. (C) A Kaplan-Meier plot of mouse survival data from the experiment described in panel A. (D) Purified CD138+ plasma cells obtained from patients who were immunomodulatory drug-naïve or lenalidomide-exposed and predominantly –refractory were evaluated for their surface expression of CD44 using FACS as described earlier. The left panel shows a representative histogram overlay of one lenalidomide-naive patient’s sample and another sample from a patient with lenalidomide-refractory disease. Both were probed with either the matched isotype control (dotted line) or the CD44 antibody (solid line). Mean fluorescent intensity values were obtained after normalizing to the isotype controls, and are displayed as a ratio of CD44/isotype (right panel) in 39 patients. (E) Purified CD138+ plasma cells obtained from patients who were lenalidomide refractory were treated for 72 hours with vehicle, lenalidomide, ATRA, or the combination, and viability was then analyzed using the WST-1 assay. All values are normalized to the vehicle control, which was set at 100%, and presented as the average of triplicate measurements ± S.D.

We also wanted to study the effects of ATRA and lenalidomide in primary samples, and therefore first evaluated cell surface levels of CD44 by FACS. In samples collected from patients who had received prior lenalidomide, including many who were clinically lenalidomide-refractory, we found a significantly increased CD44 surface expression compared to samples from lenalidomide-naïve patients (Figure 7C). Finally, we studied the effects of lenalidomide and ATRA on primary CD138+ cells from patients with clinically refractory/relapsed disease after at least one prior lenalidomide-containing regimen. All seven primary samples showed a reduction in viability of no more than 30% with lenalidomide alone, while some (MM2, MM5, and MM7) exhibited a negligible response. Most of the samples showed some response to ATRA, but in all of the samples, the ATRA/lenalidomide combination was superior at reducing cellular viability. Together, these data support the hypothesis that lenalidomide resistance associated with Wnt/β-catenin activation is at least in part mediated by CD44 and CAM-DR, and validate approaches that target Wnt/β-catenin and/or CD44 as rational maneuvers to overcome lenalidomide resistance.

Discussion

The incorporation of novel drugs such as proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory agents into our chemotherapeutic armamentarium against multiple myeloma has dramatically improved the outcomes of patients afflicted with this disease.(23, 24) Lenalidomide is the key member of the latter drug class, due in part to a more favorable toxicity profile and enhanced activity.(25) Initially approved for myeloma as an approach to combat relapsed and relapsed/refractory disease in combination with high-dose dexamethasone,(26, 27) lenalidomide, which is also active by itself,(28) is now being used in many combinations in this setting, such as with bortezomib and dexamethasone.(28) Moreover, lenalidomide is now a standard of care with low-dose dexamethasone,(29) bortezomib and dexamethasone,(30) or melphalan and prednisone(31) for newly diagnosed, symptomatic disease. Finally, lenalidomide is increasingly used as a single agent in maintenance therapy for transplant-ineligible patients,(31) and in patients who have previously undergone stem cell transplantation.(32, 33) However, long-term follow-up of patients continuously treated with lenalidomide has not revealed a plateau in the progression-free or overall survival curves,(31–34) and the vast majority suffer disease progression, indicating the outgrowth of drug-resistant clones. These findings indicate the importance of understanding the lenalidomide-resistant phenotype at the molecular level, so that novel strategies can be developed to overcome it, or possibly preclude its emergence altogether.

In order to begin to elucidate the mechanisms that contribute to lenalidomide resistance, we previously developed myeloma cell lines that were resistant to the anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of this agent.(3) After identifying activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway,(3) we have herein demonstrated that at least one downstream transcriptional target, CD44, may be a mediator of the lenalidomide-resistant phenotype. Notably, while our results support the hypothesis that CD44 mediates the resistant phenotype in part through the protective effect of enhanced cellular adhesion, the role of downstream CD44/HA signaling is not known. We are currently exploring the role of CD44-mediated intracellular signaling in the resistant phenotype, which may include the activation of Akt,(35) a known pro-survival factor important in multiple myeloma. Also, from a mechanistic standpoint, there is an apparent paradox concerning the engagement of CD44 to HA, and the differences between downstream signaling effects with an anchorage, or immobilized dependent effect.(36, 37) This paradox is also reflected in our data which suggest that CD44 binding to free HA acts as an antagonist(38), especially in the presence of lenalidomide, whereas binding to immobilized-HA had a protective benefit. In this context, it is clear that the role of immobilized-HA, which would be prevalent in the bone marrow microenvironment, would serve to protect cells that overexpress CD44 from lenalidomide-induced cytotoxicity.

Furthermore, our findings showed a strong association between CD44 expression and prior exposure and clinical resistance to lenalidomide. It is therefore possible to advance the hypothesis that plasma cell surface CD44 levels determined by FACS, or mRNA levels determined by gene expression profiling, or even soluble serum CD44 levels, could serve as biomarkers of lenalidomide resistance. Patients whose disease would be showing evidence of clinical lenalidomide resistance could then be evaluated to determine if CD44 was activated, and those where this was found to be the case could be selected for therapy with the lenalidomide/ATRA combination.

From a clinical perspective, we have potentially identified an effective and well-tolerated active agent in ATRA to effectively reduce the protective effects of CD44 against lenalidomide through blockade of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, in patients who display relapsed/refractory disease against lenalidomide-based regimens. Notably, while an initial study of ATRA in relapsed/refractory myeloma described hypercalcemia as a complication in three patients,(39) subsequent trials have found it to be well tolerated both alone, and in combination with other agents,(40, 41) supporting the translation of this concept to the clinic.

Alternatively, it may be proposed that the lenalidomide/ATRA regimen could be started instead of single-agent lenalidomide in patients whose disease showed higher CD44 levels at baseline, or even in all patients to suppress the emergence of resistance. Another interesting finding from our studies was that even drug-naïve cell lines contained a sub-population of cells that expressed higher CD44 levels, and these were relatively resistant to lenalidomide at baseline. This raises the question of whether acquired lenalidomide resistance occurs by acquisition of a new drug-induced phenotype, or whether it is a result of selection of a pre-existing clone that is already relatively resistant before exposure to drug. Recent whole genome sequencing studies in murine myeloma models,(42) and of primary patient samples,(43) have described compelling evidence of a prominent role for competition between subclones both spontaneously, and with therapeutic selection. These findings, as well as our studies showing effects of lenalidomide on the Wnt/β-catenin/CD44 axis, suggest that both drug-induced effects on the cell population as a whole, as well as selection of specific clones, probably contribute to the drug-resistant phenotype.

Our data strongly support a role for signaling through the Wnt/β-catenin axis in the development of lenalidomide resistance. In this study, we also showed the direct involvement of CD44/HA engagement in protection from lenalidomide-induced cytotoxicity by shRNA knockdown of CD44. Curiously, even though we knocked-down CD44 in lenalidomide-sensitive cells, we did not increase their sensitivity. This observation could be due to a number of possibilities, but may be most likely due to the lower dependence of the drug-sensitive cells on CAM-DR as mediated by CD44. Another mediator of immunomodulatory drug resistance that has been identified is Cereblon. Initially described in the context of myeloma as the primary target of teratogenicity for thalidomide,(44) Cereblon has more recently been shown to be required for the anti-proliferative activity of immunomodulatory agents.(45, 46) Moreover, Cereblon suppression was associated with resistance to lenalidomide,(45) while its over- expression enhanced sensitivity to pomalidomide.(46) Interestingly, in our lenalidomide- resistant ANBL-6-, KAS-6/1-, and U266-derived cells, Cereblon expression was relatively preserved (not shown). Moreover, manipulation of Wnt/β-catenin activity, such as with ATRA, did not enhance Cereblon expression levels (not shown), indicating that this was not responsible for restoration of lenalidomide sensitivity. These data suggest the hypothesis that the Wnt/β-catenin axis and Cereblon represent different mechanisms for lenalidomide resistance. However, the possibility that these are somehow linked needs still to be considered as well, and further mechanistic studies are being pursued in this area.

Patients with myeloma have benefited greatly from therapeutic approaches incorporating lenalidomide, but one cautionary note has been raised by three recent randomized studies, in which lenalidomide was given as a single agent in the maintenance setting.(31–33) All three showed a small increase in the risk of second primary malignancies among patients who received maintenance with lenalidomide compared to the placebo groups. These malignancies included a wide range of solid tumors such as breast, central nervous system, colon, esophageal, gynecologic, prostate, sinus, thyroid, and kidney tumors, and melanoma. Hematologic malignancies were seen as well, including acute myeloid leukemia, Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas, myelodysplastic syndrome, T-cell and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemias, and myelomonocytic leukemia. Moreover, retrospective analysis of studies in patients with relapsed and/or refractory myeloma also showed an increased risk of second primary malignancies among those treated with lenalidomide and dexamethasone.(47) Multiple influences probably contribute to the increased risk of second malignancies in patients with myeloma, including those due to host genetic and behavioral factors, environmental factors, and myeloma- and treatment-related factors.(48) Notably, dysregulation of Wnt/β-catenin/CD44 signaling resulting in the activation of this pathway has been linked to the pathogenesis of virtually all of these and other tumor types, as well as their progression and aggressiveness, and in the maintenance of cancer stem cells.(5, 49–52) Thus, it is tempting to speculate that, if our data showing induction by lenalidomide of the Wnt/β-catenin/CD44 axis in malignant plasma cells can be reproduced in normal tissues, this may be the mechanistic link between lenalidomide and second primary malignancies. If that is indeed the case, then blockade of Wnt/β-catenin/CD44 signaling could not only enhance the activity of lenalidomide and improve the outcomes of patients with myeloma, but also reduce the risk of second primary tumors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Flow Cytometry and Cellular Imaging Core Facility, and the Cell Line Characterization Core funded under the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant (NCI # CA16672). This work was supported by a Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation Senior Award (to R.Z.O.), and a Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation Research Fellow Award (to C.C.B.). R.Z.O. would also like to acknowledge support from the National Cancer Institute in the form of The M. D. Anderson Cancer Center SPORE in Multiple Myeloma (P50 CA142509). The authors would also like to acknowledge support from the Brock Family Myeloma Research Fund.

Footnotes

Authorship Contributions

C.C.B. conceived and performed the majority of the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared the figures, and wrote the manuscript; R.J.J. assisted with some experiments and was involved in data analysis and manuscript preparation; V.B. and H.Y.L provided statistical analyses of mouse xenograft modeling; Q.B. facilitated access to primary samples and provided helpful discussions; I.K. performed in vivo experiments; H.W. generated Lentiviral constructs; J.J.S., S.K.T., R.A., M.W., and D.M.W. facilitated access to primary samples; and R.Z.O. provided research guidance, supervised the work herein, facilitated access to primary samples, and proofed the manuscript.

Supplementary information is available at Leukemia’s website

Conflict of interest: *C.C.B was a post-doctoral fellow at M. D. Anderson when these studies were performed, but is currently an employee at Celgene Corporation and holds company stock options. R.Z.O. has served on advisory boards for Celgene Corporation, which markets lenalidomide, and also has received research funding and honoraria from Celgene.

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest

C.C.B was a post-doctoral fellow at M. D. Anderson when these studies were performed, but is currently an employee at Celgene Corporation and holds company stock options. R.Z.O. has served on advisory boards for Celgene Corporation, which markets lenalidomide, and also has received research funding and honoraria from Celgene.

References

- 1.Laubach J, Richardson P, Anderson K. Multiple myeloma. Annual review of medicine. 2011 Feb 18;62:249–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-070209-175325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quach H, Kalff A, Spencer A. Lenalidomide in multiple myeloma: Current status and future potential. American journal of hematology. 2012 Apr 26; doi: 10.1002/ajh.23234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjorklund CC, Ma W, Wang ZQ, Davis RE, Kuhn DJ, Kornblau SM, et al. Evidence of a role for activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in the resistance of plasma cells to lenalidomide. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011 Apr 1;286(13):11009–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.180208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wielenga VJ, Smits R, Korinek V, Smit L, Kielman M, Fodde R, et al. Expression of CD44 in Apc and Tcf mutant mice implies regulation by the WNT pathway. The American journal of pathology. 1999 Feb;154(2):515–23. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65297-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ponta H, Sherman L, Herrlich PA. CD44: from adhesion molecules to signalling regulators. Nature reviews. 2003 Jan;4(1):33–45. doi: 10.1038/nrm1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohashi R, Takahashi F, Cui R, Yoshioka M, Gu T, Sasaki S, et al. Interaction between CD44 and hyaluronate induces chemoresistance in non-small cell lung cancer cell. Cancer letters. 2007 Jul 18;252(2):225–34. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hao JL, Cozzi PJ, Khatri A, Power CA, Li Y. CD147/EMMPRIN and CD44 are potential therapeutic targets for metastatic prostate cancer. Current cancer drug targets. 2010 May;10(3):287–306. doi: 10.2174/156800910791190193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Phuc P, Nhan PL, Nhung TH, Tam NT, Hoang NM, Tue VG, et al. Downregulation of CD44 reduces doxorubicin resistance of CD44CD24 breast cancer cells. OncoTargets and therapy. 2011;4:71–8. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S21431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohwada C, Nakaseko C, Koizumi M, Takeuchi M, Ozawa S, Naito M, et al. CD44 and hyaluronan engagement promotes dexamethasone resistance in human myeloma cells. European journal of haematology. 2008 Mar;80(3):245–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masson D, Denis MG, Denis M, Blanchard D, Loirat MJ, Cassagnau E, et al. Soluble CD44: quantification and molecular repartition in plasma of patients with colorectal cancer. British journal of cancer. 1999 Aug;80(12):1995–2000. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah N, Cabanillas F, McIntyre B, Feng L, McLaughlin P, Rodriguez MA, et al. Prognostic value of serum CD44, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 levels in patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2012 Jan;53(1):50–6. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.616611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krause DS, Spitzer TR, Stowell CP. The concentration of CD44 is increased in hematopoietic stem cell grafts of patients with acute myeloid leukemia, plasma cell myeloma, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2010 Jul;134(7):1033–8. doi: 10.5858/2009-0347-OA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dahl IM, Turesson I, Holmberg E, Lilja K. Serum hyaluronan in patients with multiple myeloma: correlation with survival and Ig concentration. Blood. 1999 Jun 15;93(12):4144–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vincent T, Mechti N. IL-6 regulates CD44 cell surface expression on human myeloma cells. Leukemia. 2004 May;18(5):967–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voorhees PM, Chen Q, Kuhn DJ, Small GW, Hunsucker SA, Strader JS, et al. Inhibition of interleukin-6 signaling with CNTO 328 enhances the activity of bortezomib in preclinical models of multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007 Nov 1;13(21):6469–78. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voorhees PM, Chen Q, Small GW, Kuhn DJ, Hunsucker SA, Nemeth JA, et al. Targeted inhibition of interleukin-6 with CNTO 328 sensitizes pre-clinical models of multiple myeloma to dexamethasone-mediated cell death. British journal of haematology. 2009 May;145(4):481–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07647.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunsucker SA, Magarotto V, Kuhn DJ, Kornblau SM, Wang M, Weber DM, et al. Blockade of interleukin-6 signalling with siltuximab enhances melphalan cytotoxicity in preclinical models of multiple myeloma. British journal of haematology. 2011 Mar;152(5):579–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08533.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Handeli S, Simon JA. A small-molecule inhibitor of Tcf/beta-catenin signaling down-regulates PPARgamma and PPARdelta activities. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2008 Mar;7(3):521–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu J, Zhang F, Zhao D, Hong L, Min J, Zhang L, et al. ATRA-inhibited proliferation in glioma cells is associated with subcellular redistribution of beta-catenin via up-regulation of Axin. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2008 May;87(3):271–7. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9518-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dillard AC, Lane MA. Retinol Increases beta-catenin-RXRalpha binding leading to the increased proteasomal degradation of beta-catenin and RXRalpha. Nutrition and cancer. 2008;60(1):97–108. doi: 10.1080/01635580701586754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim YC, Kang HJ, Kim YS, Choi EC. All-trans-retinoic acid inhibits growth of head and neck cancer stem cells by suppression of Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Eur J Cancer. 2012 May 26; doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu J, Bi G, Wen P, Yang W, Ren X, Tang T, et al. Down-regulation of CD44 contributes to the differentiation of HL-60 cells induced by ATRA or HMBA. Cellular & molecular immunology. 2007 Feb;4(1):59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Hayman SR, Buadi FK, et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood. 2008 Mar 1;111(5):2516–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kastritis E, Zervas K, Symeonidis A, Terpos E, Delimbassi S, Anagnostopoulos N, et al. Improved survival of patients with multiple myeloma after the introduction of novel agents and the applicability of the International Staging System (ISS): an analysis of the Greek Myeloma Study Group (GMSG) Leukemia. 2009 Jun;23(6):1152–7. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gay F, Hayman SR, Lacy MQ, Buadi F, Gertz MA, Kumar S, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone versus thalidomide plus dexamethasone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a comparative analysis of 411 patients. Blood. 2010 Feb 18;115(7):1343–50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weber DM, Chen C, Niesvizky R, Wang M, Belch A, Stadtmauer EA, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma in North America. The New England journal of medicine. 2007 Nov 22;357(21):2133–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dimopoulos M, Spencer A, Attal M, Prince HM, Harousseau JL, Dmoszynska A, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. The New England journal of medicine. 2007 Nov 22;357(21):2123–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richardson PG, Weller E, Jagannath S, Avigan DE, Alsina M, Schlossman RL, et al. Multicenter, phase I, dose-escalation trial of lenalidomide plus bortezomib for relapsed and relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Dec 1;27(34):5713–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajkumar SV, Jacobus S, Callander NS, Fonseca R, Vesole DH, Williams ME, et al. Lenalidomide plus high-dose dexamethasone versus lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone as initial therapy for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: an open-label randomised controlled trial. The lancet oncology. 2010 Jan;11(1):29–37. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70284-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richardson PG, Weller E, Lonial S, Jakubowiak AJ, Jagannath S, Raje NS, et al. Lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone combination therapy in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2010 Aug 5;116(5):679–86. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-268862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palumbo A, Hajek R, Delforge M, Kropff M, Petrucci MT, Catalano J, et al. Continuous lenalidomide treatment for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 May 10;366(19):1759–69. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Marit G, Caillot D, Moreau P, Facon T, et al. Lenalidomide maintenance after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 May 10;366(19):1782–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCarthy PL, Owzar K, Hofmeister CC, Hurd DD, Hassoun H, Richardson PG, et al. Lenalidomide after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 May 10;366(19):1770–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dimopoulos MA, Chen C, Spencer A, Niesvizky R, Attal M, Stadtmauer EA, et al. Long-term follow-up on overall survival from the MM-009 and MM-010 phase III trials of lenalidomide plus dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2009 Nov;23(11):2147–52. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang SJ, Bourguignon LYW. Role of Hyaluronan-Mediated CD44 Signaling in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Progression and Chemoresistance. The American journal of pathology. 2011 Mar;178(3):956–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toole BP. Hyaluronan-CD44 Interactions in Cancer: Paradoxes and Possibilities. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009 Dec 15;15(24):7462–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toole BP, Slomiany MG. Hyaluronan, CD44 and Emmprin: Partners in cancer cell chemoresistance. Drug Resistance Updates. 2008 Jun;11(3):110–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slomiany MG, Dai L, Bomar PA, Knackstedt TJ, Kranc DA, Tolliver L, et al. Abrogating Drug Resistance in Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors by Disrupting Hyaluronan-CD44 Interactions with Small Hyaluronan Oligosaccharides. Cancer Research. 2009 Jun 15;69(12):4992–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Niesvizky R, Siegel DS, Busquets X, Nichols G, Muindi J, Warrell RP, Jr, et al. Hypercalcaemia and increased serum interleukin-6 levels induced by all-trans retinoic acid in patients with multiple myeloma. British journal of haematology. 1995 Jan;89(1):217–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb08936.x. Epub 1995/01/01. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Musto P, Sajeva MR, Sanpaolo G, D’Arena G, Scalzulli PR, Carotenuto M. All- trans retinoic acid in combination with alpha-interferon and dexamethasone for advanced multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 1997 May-Jun;82(3):354–6. Epub 1997/05/01. eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koskela K, Pelliniemi TT, Pulkki K, Remes K. Treatment of multiple myeloma with all-trans retinoic acid alone and in combination with chemotherapy: a phase I/II trial. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2004 Apr;45(4):749–54. doi: 10.1080/10428190310001628158. Epub 2004/05/27. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keats JJ, Chesi M, Egan JB, Garbitt VM, Palmer SE, Braggio E, et al. Clonal competition with alternating dominance in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012 Aug 2;120(5):1067–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-405985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Egan JB, Shi CX, Tembe W, Christoforides A, Kurdoglu A, Sinari S, et al. Whole- genome sequencing of multiple myeloma from diagnosis to plasma cell leukemia reveals genomic initiating events, evolution, and clonal tides. Blood. 2012 Aug 2;120(5):1060–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-405977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ito T, Ando H, Suzuki T, Ogura T, Hotta K, Imamura Y, et al. Identification of a primary target of thalidomide teratogenicity. Science (New York, NY. 2010 Mar 12;327(5971):1345–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1177319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu YX, Braggio E, Shi CX, Bruins LA, Schmidt JE, Van Wier S, et al. Cereblon expression is required for the antimyeloma activity of lenalidomide and pomalidomide. Blood. 2012 Nov 3;118(18):4771–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-356063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lopez-Girona A, Mendy D, Ito T, Miller K, Gandhi AK, Kang J, et al. Cereblon is a direct protein target for immunomodulatory and antiproliferative activities of lenalidomide and pomalidomide. Leukemia. 2012 May 3; doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dimopoulos MA, Richardson PG, Brandenburg N, Yu Z, Weber DM, Niesvizky R, et al. A review of second primary malignancy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma treated with lenalidomide. Blood. 2012 Mar 22;119(12):2764–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-373514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas A, Mailankody S, Korde N, Kristinsson SY, Turesson I, Landgren O. Second malignancies after multiple myeloma: from 1960s to 2010s. Blood. 2012 Mar 22;119(12):2731–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-381426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Developmental cell. 2009 Jul;17(1):9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takahashi-Yanaga F, Kahn M. Targeting Wnt signaling: can we safely eradicate cancer stem cells? Clin Cancer Res. 2010 Jun 15;16(12):3153–62. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hertweck MK, Erdfelder F, Kreuzer KA. CD44 in hematological neoplasias. Annals of hematology. 2011 May;90(5):493–508. doi: 10.1007/s00277-011-1161-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Misra S, Heldin P, Hascall VC, Karamanos NK, Skandalis SS, Markwald RR, et al. Hyaluronan-CD44 interactions as potential targets for cancer therapy. The FEBS journal. 2012 May;278(9):1429–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.