Abstract

Background

Anti-retroviral treated HIV-infected patients are at risk of mitochondrial toxicity, but non-invasive markers are lacking. Serum FGF-21 (fibroblast growth factor 21) levels correlate strongly with muscle biopsy findings in inherited mitochondrial disorders. We therefore aimed to determine whether serum FGF-21 levels correlate with muscle mitochondrial dysfunction in HIV-infected patients.

Findings

We performed a cross-sectional study of anti-retroviral treated HIV-infected subjects (aged 29 – 71 years, n = 32). Serum FGF-21 levels were determined by quantitative ELISA. Cellular mitochondrial dysfunction was assessed by COX (cytochrome c oxidase) histochemistry of lower limb skeletal muscle biopsy. Serum FGF-21 levels were elevated in 66% of subjects. Levels correlated significantly with current CD4 lymphocyte count (p = 0.042) and with total CD4 count gain since initiation of anti-retroviral therapy (p = 0.016), but not with the nature or duration of past or current anti-retroviral treatment. There was no correlation between serum FGF-21 levels and severity of the muscle mitochondrial (COX) defect.

Conclusions

Serum FGF-21 levels are a poor predictor of muscle mitochondrial dysfunction in contemporary anti-retroviral treated patients. Serum FGF-21 levels are nevertheless commonly elevated, in association with the degree of immune recovery, suggesting a non-mitochondrial metabolic disturbance with potential implications for future comorbidity.

Keywords: HIV, Anti-retroviral therapy, Highly active, Fibroblast growth factor 21, Mitochondria

Findings

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a well-described complication of anti-retroviral therapy [1-7]. It is most strongly associated with several of the older nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs): zidovudine (AZT), stavudine (d4T), didanosine (ddI), and zalcitabine (ddC). Although these drugs are no longer in common usage in industrialised countries, there are nevertheless large numbers of patients who have had extensive prior exposure to these drugs, and some remain in common usage in developing countries. We have recently demonstrated that patients with previous exposure to these NRTIs may have persistent cellular mitochondrial COX (cytochrome c oxidase) defects in skeletal muscle, consequent on an NRTI-induced accumulation of somatic (acquired) mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations [8].

Non-invasive measures of mitochondrial damage would be very valuable in the HIV clinic, both for the diagnosis of anti-retroviral associated mitochondrial dysfunction and the serial monitoring of such patients. The determination of mtDNA content in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) has previously been proposed as such a measure [5,9-11]. This consideration arises from the fact that the mitochondrially-toxic NRTIs (as listed above) cause a reduction in cellular mtDNA content (depletion) during therapy [2,3,6,10,12-16]. However, modern N(t)RTIs such as tenofovir (TDF) and abacavir (ABC) do not cause mtDNA depletion [17], and as a result, mtDNA levels return to normal with a switch away from a mitochondrially-toxic NRTI. Thus, measuring mtDNA levels is not a useful measure of on-going mitochondrial dysfunction due to an NRTI exposure in the distant past.

In contrast, FGF-21 (fibroblast growth factor 21) has recently been proposed as a valuable serum measure in inherited mitochondrial disease [18]. In these patients, serum FGF-21 levels showed a very strong correlation with mitochondrial dysfunction on skeletal muscle biopsy, as determined by the percentage of cells expressing a COX defect [18]. FGF-21 is thought to regulate mitochondrial activity and enhance oxidative capacity, mediated via PGC-1α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator 1-alpha) expression [19]. To date, one study has assessed serum FGF-21 in HIV infection, and demonstrated elevated levels [20]. Given the recently described association between serum FGF-21 elevation and muscle COX defects in inherited mitochondrial disorders [18], and the recent observation of significant COX defects in long-term anti-retroviral treated HIV-infected patients [8], we speculated that muscle mitochondrial dysfunction might also drive the FGF-21 elevation in anti-retroviral treated HIV infection.

Patient characteristics

All subjects gave informed written consent for participation, and the study was approved by local research ethics committee (Newcastle and North Tyneside Research Ethics Committee). We performed a cross-sectional study of adult HIV-1 infected patients, receiving ambulatory care at one of two specialist clinics in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK. Patients with current active hepatitis B or C co-infection, known inherited or non-HIV-associated neuromuscular disease, and diabetes mellitus were excluded. No subjects were clinically obese (BMI >30). 32 HIV-infected subjects participated, of whom 81% were male. 84% were of white Caucasian ethnicity and the remainder black African. Mean age was 48.7 years, with age range of 29–71 years. Mean duration of diagnosed HIV infection was 10.8 years. Mean current CD4 lymphocyte count was 663 cells/μl, and 61% of subjects had nadir CD4 count of <200 cells/μl. All subjects were currently receiving combination anti-retroviral therapy, with a mean duration of treatment of 9.2 years. 97% of patients had fully suppressed HIV plasma viral load (<50 HIV-1 RNA copies/ml). 81% of subjects were receiving a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) and 22% a ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor (PI). Regarding past (lifetime) NRTI treatment experience, 72% of patients had a history of AZT exposure, and 25% had a history of prior d-drug (dideoxynucleoside analogue) exposure. Characteristics of individual subjects are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Age (y) | Gender | Ethnicity | Duration of diagnosed HIV (mo) | ART duration (mo) | Nadir CD4 count (cells/uL) | Current CD4 count (cells/uL) | LDS | ART (current) | ART (lifetime) | COX defect (%) | Serum FGF-21 (pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 71 |

M |

WB |

130 |

130 |

UK |

530 |

Y |

TDF FTC EFV |

ddi AZT 3TC EFV TDF FTC |

3.0% |

232 |

| 48 |

F |

BA |

100 |

99 |

10 |

487 |

N |

TDF FTC NVP |

AZT 3TC EFVTDF FTC NVP |

0.1% |

>1920 |

| 34 |

F |

WB |

88 |

86 |

218 |

1121 |

Y |

ABC 3TC NVP |

AZT 3TC NVP ABC |

0.0% |

560 |

| 55 |

F |

BA |

64 |

27 |

112 |

426 |

N |

TDF FTC AZT DRV/r |

TDF FTC LPV/r AZT DRV/r |

0.8% |

164 |

| 43 |

M |

BA |

87 |

87 |

152 |

306 |

N |

TDF FTC EFV |

AZT 3TC EFV TDF FTC |

0.8% |

20 |

| 42 |

M |

WB |

185 |

147 |

150 |

636 |

N |

AZT 3TC EFV |

AZT 3TC NVP |

0.0% |

342 |

| 63 |

M |

WB |

97 |

97 |

169 |

870 |

N |

ABC 3TC EFV |

AZT 3TC EFV ABC |

0.0% |

204 |

| 29 |

M |

WB |

84 |

32 |

197 |

401 |

N |

TDF FTC EFV |

TDF FTC EFV |

0.0% |

809 |

| 63 |

M |

WB |

238 |

221 |

NA |

438 |

N |

ABC 3TC NVP |

AZT ddl d4T 3TC ddC IDV NVP ABC |

2.2% |

440 |

| 62 |

M |

WB |

63 |

62 |

56 |

190 |

N |

TDF FTC NVP |

TOP FTC NVP |

0.2% |

156 |

| 52 |

M |

WB |

225 |

225 |

120 |

728 |

Y |

TDF FTC ATV/r |

AZT ddC ddl 3TC d4T SQV NVP IDV NFV ABC TDF LPV/r FTC ATV/r |

1.3% |

328 |

| 36 |

M |

WB |

139 |

138 |

197 |

627 |

N |

AZT 3TC EFV |

AZT 3TC EFV TDF FTC |

0.3% |

214 |

| 51 |

M |

WB |

190 |

183 |

10 |

747 |

N |

ABC TDF NVP |

AZT ddl d4T 3TC RTV NVP IDV ddC ABC ATV/r TDF |

4.9% |

252 |

| 33 |

F |

WB |

96 |

95 |

83 |

1289 |

N |

TDF FTC EFV |

AZT 3TC EFV TDF FTC |

0.0% |

177 |

| 48 |

M |

WB |

102 |

100 |

259 |

1329 |

Y |

AZT 3TC EFV |

AZT 3TC EFV |

0.4% |

409 |

| 51 |

M |

WB |

145 |

144 |

151 |

421 |

N |

AZT 3TC NVP |

AZT 3TC NVP |

1.4% |

254 |

| 66 |

M |

WB |

71 |

26 |

287 |

455 |

N |

TDF FTC EFV |

TDF FTC EFV |

11.2% |

470 |

| 46 |

M |

WB |

158 |

157 |

250 |

1452 |

N |

TDF FTC EFV |

AZT 3TC IDV EFV ABC TDF FTC |

1.4% |

1218 |

| 61 |

M |

WB |

116 |

113 |

NA |

498 |

Y |

TDF FTC NVP |

AZT 3TC EFV NVP TDF FTC |

2.4% |

182- |

| 30 |

M |

WB |

88 |

23 |

283 |

661 |

N |

TDF FTC DRV/r |

TDF FTC EFV DRV/r |

0.1% |

207 |

| 62 |

M |

WB |

284 |

202 |

NA |

422 |

N |

ABC NVP LPV/r |

SQV AZT ddC 3TC d4T ddl IDV ABC NVP NFV LPV/r |

0.8% |

92 |

| 45 |

|

WB |

159 |

158 |

176 |

660 |

N |

TDF FTC NVP |

AZT 3TC IDV NVP TDF FTC |

0.0% |

60 |

| 54 |

M |

WB |

79 |

38 |

244 |

638 |

N |

TDF FTC DRV/r |

TDF FTC EFV DRV/r |

3.4% |

178 |

| 52 |

M |

WB |

166 |

164 |

0 |

662 |

Y |

TDF FTC NVP |

AZT d4T IDV NFV SQV 3TC NVP ddl TDF FTC |

2.8% |

525 |

| 51 |

M |

WB |

243 |

171 |

327 |

539 |

Y |

TDF FTC EFV |

AZT ddl RTV NFV TDF FTC EFV |

1.5% |

231 |

| 35 |

F |

BA |

62 |

25 |

380 |

638 |

N |

TDF FTC EFV |

TOP FTC EFV |

0.0% |

82 |

| 53 |

M |

WB |

NA |

48 |

301 |

804 |

N |

TDF FTC EFV |

TDF FTC EFV |

NA |

490 |

| 36 |

M |

WB |

130 |

130 |

18 |

898 |

N |

TDF FTC ATV/r |

AZT 3TC EFV TDF FTC ATV/r |

0.0% |

530 |

| 48 |

M |

WB |

53 |

14 |

332 |

443 |

N |

TDF FTC EFV |

TDF FTC EFV |

0.0% |

56 |

| 52 |

F |

BA |

83 |

81 |

17 |

485 |

Y |

TDF FTC EFV |

AZT 3TC EFV TDF FTC |

0.7% |

224 |

| 38 |

M |

WB |

129 |

128 |

4 |

761 |

Y |

TDF FTC EFV |

AZT 3TC EFV TDF FTC |

0.0% |

935 |

| 47 | M | WB | 183 | 164 | 305 | 668 | Y | ABC RAL ATV/r | d4T 3TC NVP ddl IDV ABC ATV/r RAL | 9.8% | 114 |

Summary characteristics of individual HIV-infected subjects. (WB, white British; BA, black African; ART, anti-retroviral therapy; LDS, lipodystrophy syndrome; AZT, zidovudine; d4T, stavudine; ddI, didanosine; ddC, zalcitabine; 3TC, lamivudine; ABC, abacavir; TDF, tenofovir; FTC, emtricitabine; EFV, efavirenz; NVP, nevirapine; ATV, atazanavir; DRV, darunavir; LPV, lopinavir; SQV, saquinavir; NFV, nelfinavir; IDV, indinavir; RTV, ritonavir at therapeutic dose; /r, ritonavir at pharmacokinetic boosting dose; RAL, raltegravir; COX, cytochrome c oxidase; FGF-21, fibroblast growth factor 21; NA, not available).

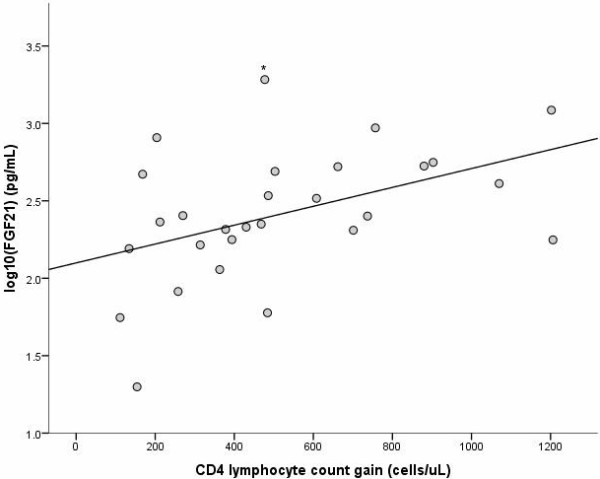

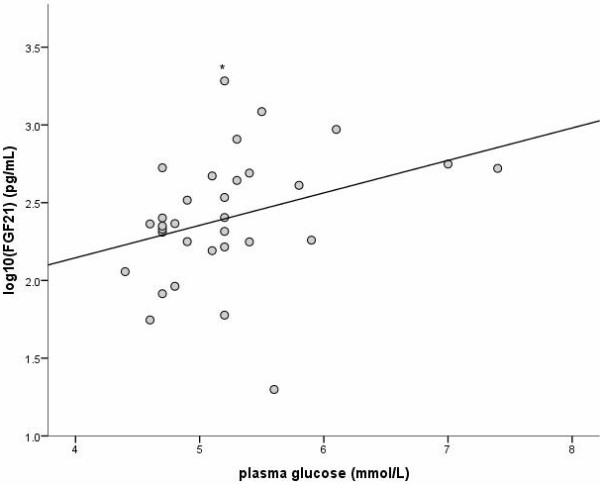

FGF-21 determination

Serum FGF-21 levels were determined by quantitative ELISA (BioVendor, Brno, Czech Republic), performed in triplicate, and normalised by log10 transformation. A serum FGF-21 level of <200 pg/ml was considered as normal in keeping with recent data [18]. Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS 19, using student’s t-test to compare binary variables and Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) to examine the relationship between log10 serum FGF-21 levels and continuous variables. Twenty-one of 32 subjects (66%) had serum FGF-21 levels greater than the normal range, with four being very elevated (>800 pg/ml). On univariate analysis, serum FGF-21 levels were positively correlated with current CD4 lymphocyte count (r = 0.36, p = 0.042), but more strongly correlated with total CD4 cell count gain since initiation of anti-retroviral therapy (current minus nadir) (r = 0.45, p = 0.016) (Figure 1). In addition, plasma glucose levels correlated with serum FGF-21 levels, although this did not quite reach statistical significance (r = 0.34, p = 0.06, Figure 2), whereas as serum lipids and liver function did not. No other demographic or treatment variables were significantly associated with serum FGF-21 levels, including the nature of current or prior anti-retroviral therapy (Table 2). FGF-21 levels did not differ significantly between patients with or without clinical lipodystrophy syndrome. Only CD4 lymphocyte count gain was independently associated with serum FGF-21 levels on multivariate linear regression analysis (p = 0.016).

Figure 1.

Correlation of serum FGF-21 levels with immune reconstitution. Correlation of log10 serum FGF-21 (fibroblast growth factor 21) levels in HIV-infected subjects and CD4 lymphocyte count gain on treatment (current minus nadir) (r = 0.45, p = 0.016). (* Serum FGF-21 >1920 pg/ml, the upper limit of quantitation of the assay).

Figure 2.

Correlation of serum FGF-21 levels with plasma glucose. Correlation of log10 serum FGF-21 (fibroblast growth factor 21) levels in HIV-infected subjects and random plasma glucose concentration (r = 0.34, p = 0.06). (* Serum FGF-21 >1920 pg/ml, the upper limit of quantitation of the assay).

Table 2.

Associations of serum FGF-21 levels

|

(a) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (n) | Log 10 Serum FGF-21, mean (SD) | p value |

| Gender |

Male (26) |

2.39 (0.40) |

|

| |

Female (6) |

2.46 (0.48) |

0.71 |

| Ethnicity |

Caucasian (27) |

2.44 (0.33) |

|

| |

Black African (5) |

2.21 (0.72) |

0.27 |

| Current ART |

PI (7) |

2.29 (0.26) |

|

| |

No PI (25) |

2.43 (0.44) |

0.43 |

| Lifetime ART |

d-drugs (8) |

2.38 (0.26) |

|

| |

No d-drugs (24) |

2.41 (0.45) |

0.86 |

| |

AZT (23) |

2.44 (0.42) |

|

| |

No AZT (9) |

2.30 (0.39) |

0.41 |

| Lipodystrophy |

Yes (10) |

2.50 (0.27) |

|

| |

No (22) |

2.36 (0.46) |

0.39 |

| Lipid-lowering therapy |

Yes (8) |

2.32 (0.52) |

|

| |

No (24) |

2.43 (0.38) |

0.53 |

|

(b) | |||

|

Variable |

|

Correlation coefficient (r) |

p value |

| Age |

|

−0.07 |

0.69 |

| Duration of diagnosed HIV infection |

|

−0.08 |

0.67 |

| Duration of lifetime ART |

Total |

0.12 |

0.50 |

| |

d-drug |

0.01 |

0.97 |

| |

AZT |

0.13 |

0.47 |

| CD4 lymphocyte count |

Nadir |

−0.29 |

0.14 |

| |

Current |

0.36 |

0.042 |

| CD4 count gain |

(Current minus nadir) |

0.45 |

0.016 |

| Serum ALT |

|

0.27 |

0.14 |

| Plasma glucose |

|

0.34 |

0.06 |

| Serum lipids |

Total cholesterol |

−0.03 |

0.87 |

| |

HDL cholesterol |

0.02 |

0.90 |

| |

Non-HDL cholesterol |

−0.06 |

0.75 |

| Mitochondrial histochemistry | COX defect (log10) | −0.02 | 0.91 |

(a) binary variables; (b) continuous variables. (PI, protease inhibitor; AZT, zidovudine; d-drug, dideoxynucleoside analogue; ART, anti-retroviral therapy; ALT, alanine transaminase; HDL, high density lipoprotein).

Bold type indicates statistically significant associations.

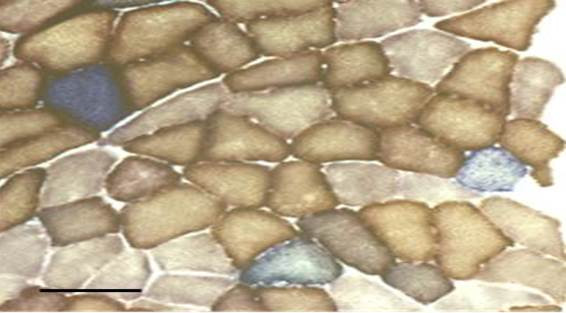

Skeletal muscle mitochondrial histochemistry

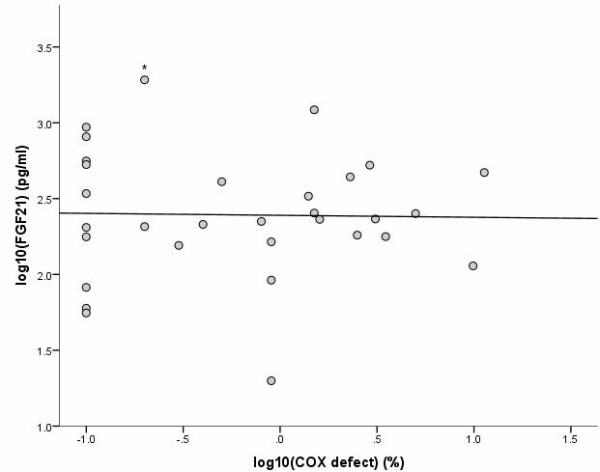

COX histochemistry was performed on cryo-sections obtained from lower limb skeletal muscle biopsies on 31 of the 32 subjects (biopsy data for one subject was not analysable). Results of 22 of these biopsies have been reported in our previous work [8], whereas the remaining 9 have not. COX contains respiratory chain subunits encoded by the mitochondrial genome, and fibres stain brown (positive) in the presence of intact respiratory chain activity (Figure 3). Proportional COX defect was determined by counting ≥500 fibres per biopsy, and normalised by log10 transformation. There was no correlation between serum FGF-21 levels and percentage COX defects on biopsy (r = −0.02, p = 0.9, Figure 4).

Figure 3.

COX histochemistry. Example of mitochondrial COX/SDH (cytochrome c oxidase/succinate dehydrogenase) histochemistry on lower limb skeletal muscle biopsy of an anti-retroviral treated HIV-infected patient. Normal (COX positive) fibres stain brown, whereas COX deficient fibres counterstain blue due to preserved SDH activity.

Figure 4.

Correlation of serum FGF-21 levels and mitochondrial defects. Correlation of log10 serum FGF-21 (fibroblast growth factor 21) levels in HIV-infected subjects and percentage COX (cytochrome c oxidase) defect on lower limb skeletal muscle biopsy (r = -0.02, p = 0.9). (* Serum FGF-21 >1920 pg/ml, the upper limit of quantitation of the assay).

Discussion

We have shown that serum FGF-21 levels are frequently elevated in contemporary anti-retroviral treated HIV-infected patients, but do not correlate with the severity of muscle mitochondrial (COX) defect. In contrast, a previous study has shown a very strong correlation between these parameters in patients with inherited mitochondrial disorders [18]. Ours is the first study to attempt to link serum FGF-21 levels with biopsy-proven mitochondrial defects in HIV-infected patients. What is the reason for this apparent discrepancy in findings? Firstly, the prior study demonstrating serum FGF-21 elevation in mitochondrial disease included a large number of patients with childhood-onset disease. Such patients typically have very severe muscle COX defects (affecting up to ~60% of fibres). In contrast, patients with late-onset inherited mitochondrial disorders typically have more modest COX defects, comparable with those seen in our HIV-infected patients (up to ~10% of fibres). The fact that some patients in our study with a biopsy COX defect of >5% of fibres had relatively normal FGF-21 levels suggests that this serum measure is not particularly sensitive for mild to moderate muscle mitochondrial defects. Secondly, the markedly abnormal serum FGF-21 levels seen in some patients with no significant COX defect suggest a non-mitochondrial origin, as has been observed in other metabolic disorders [21-23]. In the only previous study of FGF-21 levels in HIV infection, the authors found associations of FGF-21 levels with obesity, glycaemia, dyslipidaemia and liver dysfunction, in line with literature from HIV-uninfected patients [24]. In our study, we specifically excluded diabetic and obese subjects (as we wished to maximise the likelihood of detecting any association with NRTI-induced mitochondrial dysfunction). Interestingly however, the strongest predictor of serum FGF-21 levels seen in our study was a novel association with total CD4 lymphocyte count gain. This is an intriguing finding. It is plausible that patients who have low nadir CD4 lymphocyte counts may experience more profound metabolic changes as they undergo immune reconstitution on anti-retroviral therapy, switching from a catabolic state to an excessively anabolic state associated with a ‘return to health’. This association with CD4 count gain should be further explored by longitudinal study.

In conclusion, serum FGF-21 levels do not appear to be a sensitive or specific marker of muscle mitochondrial dysfunction in contemporary anti-retroviral treated patients. Nevertheless they are commonly elevated in association with immune recovery. As serum FGF-21 levels in the HIV-uninfected population are elevated in conditions associated with increased cardiovascular risk, it is very plausible that serum FGF-21 elevation in anti-retroviral treated HIV infection may also be a marker of an adverse metabolic risk in this patient group. Given the known increase in cardiovascular disease in anti-retroviral treated patients [25], the prognostic significance of our findings merits further research.

Competing interests

All authors confirm that they have no relevant competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

BP conceived the study, performed the assays and drafted the manuscript. DAP conceived and helped coordinate the study. PFC conceived the study and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Brendan AI Payne, Email: brendan.Payne@ncl.ac.uk.

David Ashley Price, Email: ashley.price@nuth.nhs.uk.

Patrick F Chinnery, Email: patrick.chinnery@ncl.ac.uk.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Alison Hague for assistance with the FGF-21 ELISA.

Funding

Medical Research Council (UK) (BP); Newcastle National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre in Ageing (BP, PFC); Medical Research Council (UK) Centre for Translational Muscle Disease (PFC); Wellcome Trust (084980/Z/08/Z & 096919Z/11/Z, PFC).

References

- Dalakas MC, Illa I, Pezeshkpour GH, Laukaitis JP, Cohen B, Griffin JL. Mitochondrial myopathy caused by long-term zidovudine therapy. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1098–1105. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199004193221602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaudo E, Dalakas M, Shanske S, Moraes CT, DiMauro S, Schon EA. Depletion of muscle mitochondrial DNA in AIDS patients with zidovudine-induced myopathy. Lancet. 1991;337:508–510. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikuma CM, Hu N, Milne C, Yost F, Waslien C, Shimizu S, Shiramizu B. Mitochondrial DNA decrease in subcutaneous adipose tissue of HIV-infected individuals with peripheral lipoatrophy. Aids. 2001;15:1801–1809. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200109280-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaera MG, Miro O, Pedrol E, Soler A, Picon M, Cardellach F, Casademont J, Nunes V. Mitochondrial involvement in antiretroviral therapy-related lipodystrophy. Aids. 2001;15:1643–1651. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200109070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Valk M, Casula M, Weverlingz GJ, van Kuijk K, van Eck-Smit B, Hulsebosch HJ, Nieuwkerk P, van Eeden A, Brinkman K, Lange J. et al. Prevalence of lipoatrophy and mitochondrial DNA content of blood and subcutaneous fat in HIV-1-infected patients randomly allocated to zidovudine- or stavudine-based therapy. Antivir Ther. 2004;9:385–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker UA, Bauerle J, Laguno M, Murillas J, Mauss S, Schmutz G, Setzer B, Miquel R, Gatell JM, Mallolas J. Depletion of mitochondrial DNA in liver under antiretroviral therapy with didanosine, stavudine, or zalcitabine. Hepatology. 2004;39:311–317. doi: 10.1002/hep.20074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miro O, Lopez S, Pedrol E, Rodriguez-Santiago B, Martinez E, Soler A, Milinkovic A, Casademont J, Nunes V, Gatell JM, Cardellach F. Mitochondrial DNA depletion and respiratory chain enzyme deficiencies are present in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of HIV-infected patients with HAART-related lipodystrophy. Antivir Ther. 2003;8:333–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne BA, Wilson IJ, Hateley CA, Horvath R, Santibanez-Koref M, Samuels DC, Price DA, Chinnery PF. Mitochondrial aging is accelerated by anti-retroviral therapy through the clonal expansion of mtDNA mutations. Nat Genet. 2011;43:806–810. doi: 10.1038/ng.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiappini F, Teicher E, Saffroy R, Pham P, Falissard B, Barrier A, Chevalier S, Debuire B, Vittecoq D, Lemoine A. Prospective evaluation of blood concentration of mitochondrial DNA as a marker of toxicity in 157 consecutively recruited untreated or HAART-treated HIV-positive patients. Lab Invest. 2004;84:908–914. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote HC, Brumme ZL, Craib KJ, Alexander CS, Wynhoven B, Ting L, Wong H, Harris M, Harrigan PR, O’Shaughnessy MV, Montaner JS. Changes in mitochondrial DNA as a marker of nucleoside toxicity in HIV-infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:811–820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner JS, Cote HC, Harris M, Hogg RS, Yip B, Chan JW, Harrigan PR, O’Shaughnessy MV. Mitochondrial toxicity in the era of HAART: evaluating venous lactate and peripheral blood mitochondrial DNA in HIV-infected patients taking antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34(Suppl 1):S85–S90. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200309011-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry CL, Gahan ME, McArthur JC, Lewin SR, Hoy JF, Wesselingh SL. Exposure to dideoxynucleosides is reflected in lowered mitochondrial DNA in subcutaneous fat. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30:271–277. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200207010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoschele D. Cell culture models for the investigation of NRTI-induced mitochondrial toxicity. Relevance for the prediction of clinical toxicity. Toxicol In Vitro. 2006;20:535–546. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalakas MC, Semino-Mora C, Leon-Monzon M. Mitochondrial alterations with mitochondrial DNA depletion in the nerves of AIDS patients with peripheral neuropathy induced by 2′3′-dideoxycytidine (ddC) Lab Invest. 2001;81:1537–1544. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond E, Nolan D, James I, Metcalf C, Mallal S. Reduction of mitochondrial DNA content and respiratory chain activity occurs in adipocytes within 6–12 months of commencing nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor therapy. Aids. 2004;18:815–817. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200403260-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SE, Copeland WC. Differential incorporation and removal of antiviral deoxynucleotides by human DNA polymerase gamma. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23616–23623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkus G, Hitchcock MJ, Cihlar T. Assessment of mitochondrial toxicity in human cells treated with tenofovir: comparison with other nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:716–723. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.716-723.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suomalainen A, Elo JM, Pietilainen KH, Hakonen AH, Sevastianova K, Korpela M, Isohanni P, Marjavaara SK, Tyni T, Kiuru-Enari S. et al. FGF-21 as a biomarker for muscle-manifesting mitochondrial respiratory chain deficiencies: a diagnostic study. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:806–818. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70155-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers JS, Shiyanova TL, Mehrbod F, Dunbar JD, Noblitt TW, Otto KA, Reifel-Miller A, Kharitonenkov A. Molecular determinants of FGF-21 activity-synergy and cross-talk with PPARgamma signaling. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210:1–6. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affandi JS, Price P, Imran D, Yunihastuti E, Djauzi S, Cherry CL. Can we predict neuropathy risk before stavudine prescription in a resource-limited setting? AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24:1281–1284. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WW, Li L, Yang GY, Li K, Qi XY, Zhu W, Tang Y, Liu H, Boden G. Circulating FGF-21 levels in normal subjects and in newly diagnose patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2008;116:65–68. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-985148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dushay J, Chui PC, Gopalakrishnan GS, Varela-Rey M, Crawley M, Fisher FM, Badman MK, Martinez-Chantar ML, Maratos-Flier E. Increased fibroblast growth factor 21 in obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:456–463. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Yeung DC, Karpisek M, Stejskal D, Zhou ZG, Liu F, Wong RL, Chow WS, Tso AW, Lam KS, Xu A. Serum FGF21 levels are increased in obesity and are independently associated with the metabolic syndrome in humans. Diabetes. 2008;57:1246–1253. doi: 10.2337/db07-1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo P, Gallego-Escuredo JM, Domingo JC, Gutierrez Mdel M, Mateo MG, Fernandez I, Vidal F, Giralt M, Villarroya F. Serum FGF21 levels are elevated in association with lipodystrophy, insulin resistance and biomarkers of liver injury in HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS. 2010;24:2629–2637. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283400088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friis-Moller N, Sabin CA, Weber R, D’Arminio Monforte A, El-Sadr WM, Reiss P, Thiebaut R, Morfeldt L, De Wit S, Pradier C. et al. Combination antiretroviral therapy and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1993–2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]